Intracellular Calcium as a Regulator of Polarization and Target Reprogramming of Macrophages

Abstract

1. Introduction

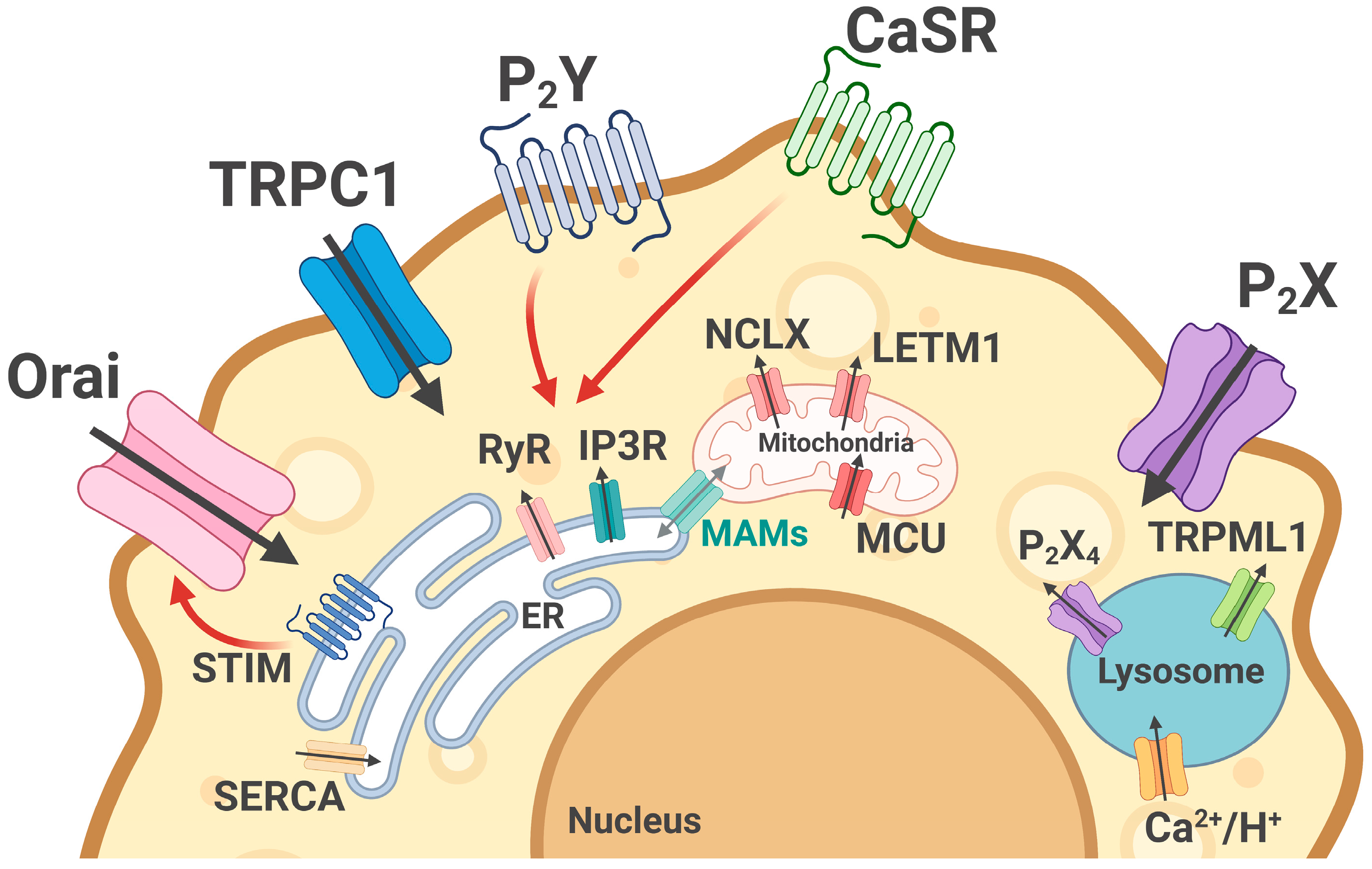

2. Macrophage Polarization in Progression and Resolution of the Pathologies

3. System of Calcium Homeostasis in Macrophages

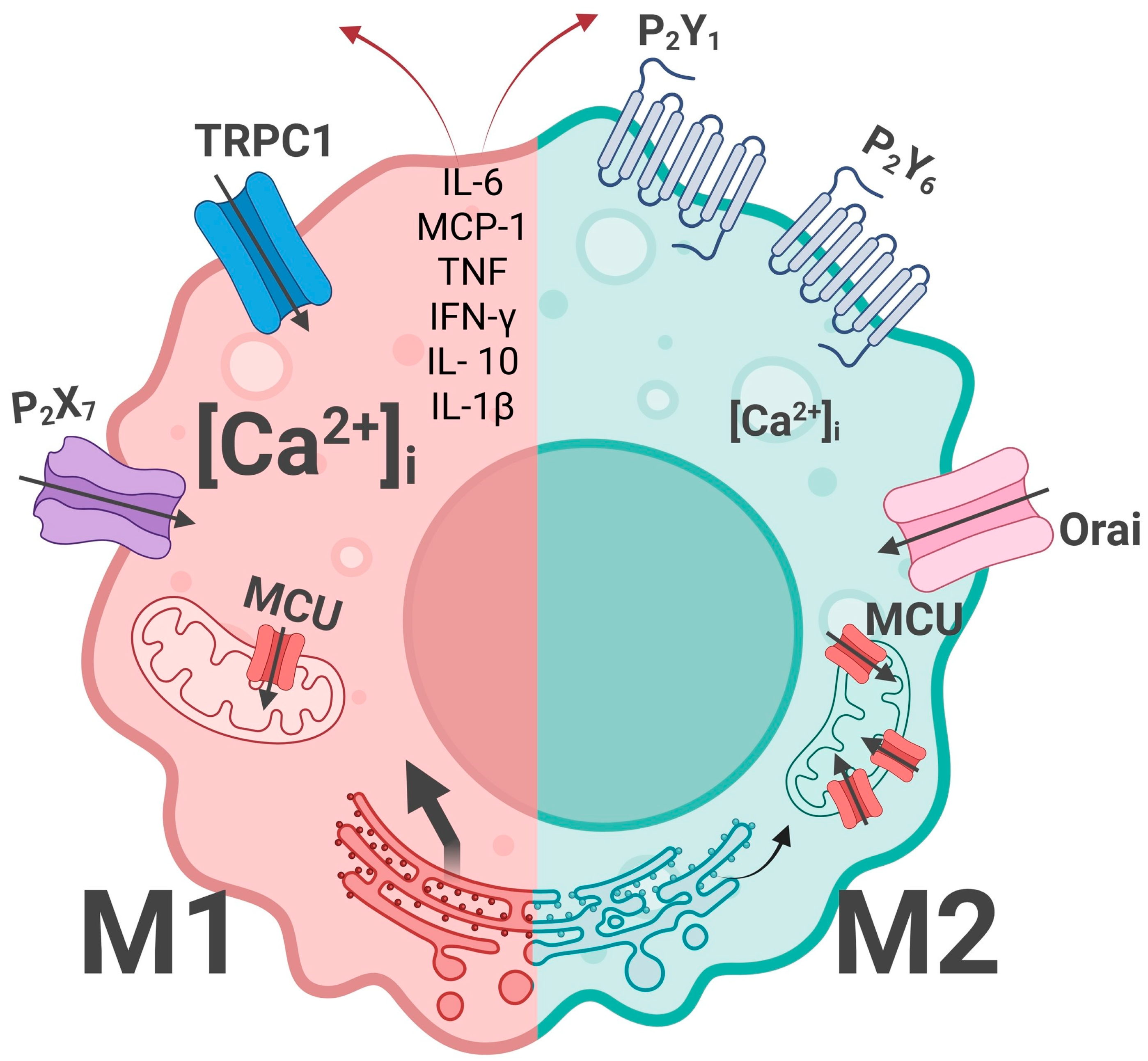

4. Calcium Signaling and Macrophage Functions

5. Calcium Homeostasis: M1/M2 Macrophage Specificity

6. Calcium Homeostasis Regulation in Macrophage Reprogramming: Perspectives for Therapy

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CaSR | Calcium-sensing receptor |

| CRAC | Calcium release-activated channel |

| ER | Endoplasmic reticulum |

| GPCR | G protein-coupled receptor |

| IP3R | Inositol-3-phosphate receptor |

| LPS | Lipopolysaccharide |

| MAMs | Mitochondria-associated membranes |

| MCU | Mitochondrial calcium uniporter |

| MDMs | Macrophage-derived macrophages |

| NCLX | Na+/Ca2+ exchanger |

| OXPHOS | Oxidative phosphorylation |

| PD | Parkinson’s disease |

| RyR | Ryanodine receptor |

| SOCE | Store-operated calcium entry |

| TAMs | Tumor-associated macrophages |

| TCA | Tricarboxylic acid cycle |

| TRMs | Tissue-resident macrophages |

| VDAC | voltage-dependent anion channel |

| VNUT | vesicular nucleotide transporter |

References

- Wang, Y.; Tao, A.; Vaeth, M.; Feske, S. Calcium Regulation of T Cell Metabolism. Curr. Opin. Physiol. 2020, 17, 207–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rimessi, A.; Pedriali, G.; Vezzani, B.; Tarocco, A.; Marchi, S.; Wieckowski, M.R.; Giorgi, C.; Pinton, P. Interorganellar Calcium Signaling in the Regulation of Cell Metabolism: A Cancer Perspective. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 2020, 98, 167–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, T.; Liu, C.-H.; Lei, M.; Zeng, Q.; Li, L.; Tang, H.; Zhang, N. Metabolic Regulation of the Immune System in Health and Diseases: Mechanisms and Interventions. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2024, 9, 268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bagur, R.; Hajnóczky, G. Intracellular Ca(2+) Sensing: Its Role in Calcium Homeostasis and Signaling. Mol. Cell 2017, 66, 780–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daverkausen-Fischer, L.; Pröls, F. Regulation of Calcium Homeostasis and Flux between the Endoplasmic Reticulum and the Cytosol. J. Biol. Chem. 2022, 298, 102061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berridge, M.J.; Bootman, M.D.; Roderick, H.L. Calcium Signalling: Dynamics, Homeostasis and Remodelling. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2003, 4, 517–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brini, M.; Calì, T.; Ottolini, D.; Carafoli, E. Intracellular Calcium Homeostasis and Signaling. Met. Ions Life Sci. 2013, 12, 119–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sukhorukov, V.N.; Khotina, V.A.; Bagheri Ekta, M.; Ivanova, E.A.; Sobenin, I.A.; Orekhov, A.N. Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress in Macrophages: The Vicious Circle of Lipid Accumulation and Pro-Inflammatory Response. Biomedicines 2020, 8, 210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rueschpler, L.; Schloer, S. Beyond the Surface: P2Y Receptor Downstream Pathways, TLR Crosstalk and Therapeutic Implications for Infection and Autoimmunity. Pharmacol. Res. 2025, 219, 107884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cekic, C.; Linden, J. Purinergic Regulation of the Immune System. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2016, 16, 177–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krebs, J. Structure, Function and Regulation of the Plasma Membrane Calcium Pump in Health and Disease. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 1027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viskupicova, J.; Espinoza-Fonseca, L.M. Allosteric Modulation of SERCA Pumps in Health and Disease: Structural Dynamics, Posttranslational Modifications, and Therapeutic Potential. J. Mol. Biol. 2025, 437, 169200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hashimoto, D.; Chow, A.; Noizat, C.; Teo, P.; Beasley, M.B.; Leboeuf, M.; Becker, C.D.; See, P.; Price, J.; Lucas, D.; et al. Tissue-Resident Macrophages Self-Maintain Locally throughout Adult Life with Minimal Contribution from Circulating Monocytes. Immunity 2013, 38, 792–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Epelman, S.; Lavine, K.J.; Randolph, G.J. Origin and Functions of Tissue Macrophages. Immunity 2014, 41, 21–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bajgar, A.; Krejčová, G. On the Origin of the Functional Versatility of Macrophages. Front. Physiol. 2023, 14, 1128984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sreejit, G.; Fleetwood, A.J.; Murphy, A.J.; Nagareddy, P.R. Origins and Diversity of Macrophages in Health and Disease. Clin. Transl. Immunol. 2020, 9, e1222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yona, S.; Kim, K.-W.; Wolf, Y.; Mildner, A.; Varol, D.; Strauss-Ayali, D.; Viukov, S.; Guilliams, M.; Misharin, A.; Hume, D.; et al. Fate Mapping Reveals Origins and Dynamics of Monocytes and Tissue Macrophages under Homeostasis. Immunity 2013, 38, 79–91, Erratum in Immunity 2013, 38, 1073–1079.. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lendeckel, U.; Venz, S.; Wolke, C. Macrophages: Shapes and Functions. Chemtexts 2022, 8, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viola, M.F.; Franco Taveras, E.; Mass, E. Developmental Programming of Tissue-Resident Macrophages. Front. Immunol. 2024, 15, 1475369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Honold, L.; Nahrendorf, M. Resident and Monocyte-Derived Macrophages in Cardiovascular Disease. Circ. Res. 2018, 122, 113–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasheed, A.; Rayner, K.J. Macrophage Responses to Environmental Stimuli During Homeostasis and Disease. Endocr. Rev. 2021, 42, 407–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, J.-D.; Gao, J.; Tang, A.-F.; Feng, C. Shaping the Immune Landscape: Multidimensional Environmental Stimuli Refine Macrophage Polarization and Foster Revolutionary Approaches in Tissue Regeneration. Heliyon 2024, 10, e37192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murray, P.J.; Wynn, T.A. Protective and Pathogenic Functions of Macrophage Subsets. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2011, 11, 723–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yunna, C.; Mengru, H.; Lei, W.; Weidong, C. Macrophage M1/M2 Polarization. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2020, 877, 173090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, Y.; Yu, Y.; Wang, X.; Zhang, T. Tumor-Associated Macrophages in Tumor Immunity. Front. Immunol. 2020, 11, 583084, Erratum in Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 775758.. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hsu, H.-Y.; Wen, M.-H. Lipopolysaccharide-Mediated Reactive Oxygen Species and Signal Transduction in the Regulation of Interleukin-1 Gene Expression. J. Biol. Chem. 2002, 277, 22131–22139, Erratum in J. Biol. Chem. 2002, 277, 33530.. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ni, R.; Jiang, L.; Zhang, C.; Liu, M.; Luo, Y.; Hu, Z.; Mou, X.; Zhu, Y. Biologic Mechanisms of Macrophage Phenotypes Responding to Infection and the Novel Therapies to Moderate Inflammation. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 8358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cutolo, M.; Soldano, S.; Smith, V.; Gotelli, E.; Hysa, E. Dynamic Macrophage Phenotypes in Autoimmune and Inflammatory Rheumatic Diseases. Nat. Rev. Rheumatol. 2025, 21, 546–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strizova, Z.; Benesova, I.; Bartolini, R.; Novysedlak, R.; Cecrdlova, E.; Foley, L.K.; Striz, I. M1/M2 Macrophages and Their Overlaps—Myth or Reality? Clin. Sci. 2023, 137, 1067–1093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tannahill, G.M.; Curtis, A.M.; Adamik, J.; Palsson-McDermott, E.M.; McGettrick, A.F.; Goel, G.; Frezza, C.; Bernard, N.J.; Kelly, B.; Foley, N.H.; et al. Succinate Is an Inflammatory Signal That Induces IL-1β through HIF-1α. Nature 2013, 496, 238–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van den Bossche, J.; Baardman, J.; Otto, N.A.; van der Velden, S.; Neele, A.E.; van den Berg, S.M.; Luque-Martin, R.; Chen, H.-J.; Boshuizen, M.C.S.; Ahmed, M.; et al. Mitochondrial Dysfunction Prevents Repolarization of Inflammatory Macrophages. Cell Rep. 2016, 17, 684–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, G.; Zhang, R.; Geng, S.; Peng, L.; Jayaraman, P.; Chen, C.; Xu, F.; Yang, J.; Li, Q.; Zheng, H.; et al. Myeloid Cell-Derived Inducible Nitric Oxide Synthase Suppresses M1 Macrophage Polarization. Nat. Commun. 2015, 6, 6676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dousdampanis, P.; Aggeletopoulou, I.; Mouzaki, A. The Role of M1/M2 Macrophage Polarization in the Pathogenesis of Obesity-Related Kidney Disease and Related Pathologies. Front. Immunol. 2024, 15, 1534823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, Y.; Zhou, M.; Yang, H.; Qu, R.; Qiu, Y.; Hao, J.; Bi, H.; Guo, D. Regulatory Mechanism of M1/M2 Macrophage Polarization in the Development of Autoimmune Diseases. Mediat. Inflamm. 2023, 2023, 8821610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rőszer, T. Understanding the Mysterious M2 Macrophage through Activation Markers and Effector Mechanisms. Mediat. Inflamm. 2015, 2015, 816460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lyu, L.; Cai, Y.; Zhang, G.; Jing, Z.; Liang, J.; Zhang, R.; Dang, X.; Zhang, C. Exosomes Derived from M2 Macrophages Induce Angiogenesis to Promote Wound Healing. Front. Mol. Biosci. 2022, 9, 1008802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, C.; Tang, Y.; Zhu, X.; Yang, J.; Liu, Z.; Chen, Y.; Wang, J.; Shang, R.; Zheng, W.; Zhang, X.; et al. P311 Promotes IL-4 Receptor–Mediated M2 Polarization of Macrophages to Enhance Angiogenesis for Efficient Skin Wound Healing. J. Investig. Dermatol. 2023, 143, 648–660.e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viola, A.; Munari, F.; Sánchez-Rodríguez, R.; Scolaro, T.; Castegna, A. The Metabolic Signature of Macrophage Responses. Front. Immunol. 2019, 10, 1462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watanabe, S.; Alexander, M.; Misharin, A.V.; Budinger, G.R.S. The Role of Macrophages in the Resolution of Inflammation. J. Clin. Investig. 2019, 129, 2619–2628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brancewicz, J.; Wójcik, N.; Sarnowska, Z.; Robak, J.; Król, M. The Multifaceted Role of Macrophages in Biology and Diseases. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 2107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, M.D.; Silvin, A.; Ginhoux, F.; Merad, M. Macrophages in Health and Disease. Cell 2022, 185, 4259–4279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez, S.; Rius-Pérez, S. Macrophage Polarization and Reprogramming in Acute Inflammation: A Redox Perspective. Antioxidants 2022, 11, 1394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.; Li, Y.; Deng, Q.; Hu, Y.; Dong, J.; Wang, W.; Wang, Y.; Li, C. Macrophage Polarization, Metabolic Reprogramming, and Inflammatory Effects in Ischemic Heart Disease. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 934040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.-F.; Shi, T.T.; Lin, Y.-L.; Zhu, Y.-T.; Lin, S.; Fang, T.-Y. Macrophage Metabolic Reprogramming in Inflammatory Bowel Diseases: From Pathogenesis to Therapy. J. Inflamm. Res. 2025, 18, 11821–11839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fedotova, E.I.; Berezhnov, A.V.; Popov, D.Y.; Shitikova, E.Y.; Vinokurov, A.Y. The Role of MtDNA Mutations in Atherosclerosis: The Influence of Mitochondrial Dysfunction on Macrophage Polarization. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 1019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khallou-Laschet, J.; Varthaman, A.; Fornasa, G.; Compain, C.; Gaston, A.-T.; Clement, M.; Dussiot, M.; Levillain, O.; Graff-Dubois, S.; Nicoletti, A.; et al. Macrophage Plasticity in Experimental Atherosclerosis. PLoS ONE 2010, 5, e8852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laria, A.; Lurati, A.; Marrazza, M.; Mazzocchi, D.; Re, K.A.; Scarpellini, M. The Macrophages in Rheumatic Diseases. J. Inflamm. Res. 2016, 9, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fukui, S.; Iwamoto, N.; Takatani, A.; Igawa, T.; Shimizu, T.; Umeda, M.; Nishino, A.; Horai, Y.; Hirai, Y.; Koga, T.; et al. M1 and M2 Monocytes in Rheumatoid Arthritis: A Contribution of Imbalance of M1/M2 Monocytes to Osteoclastogenesis. Front. Immunol. 2017, 8, 1958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kraakman, M.J.; Murphy, A.J.; Jandeleit-Dahm, K.; Kammoun, H.L. Macrophage Polarization in Obesity and Type 2 Diabetes: Weighing down Our Understanding of Macrophage Function? Front. Immunol. 2014, 5, 470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujisaka, S. The Role of Adipose Tissue M1/M2 Macrophages in Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. Diabetol. Int. 2021, 12, 74–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panda, S.; Arora, A.; Luthra, K.; Mohan, A.; Vikram, N.K.; Kumar Gupta, N.; Singh, A. Hyperglycemia Modulates M1/M2 Macrophage Polarization in Chronic Diabetic Patients with Pulmonary Tuberculosis Infection. Immunobiology 2024, 229, 152787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, K.; Zhao, Y.-F. Aging Modulates Microglia Phenotypes in Neuroinflammation of MPTP-PD Mice. Exp. Gerontol. 2018, 111, 86–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fang, H.; Chi, X.; Wang, M.; Liu, J.; Sun, M.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, W. M2 Macrophage-Derived Exosomes Promote Cell Proliferation, Migration and EMT of Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer by Secreting MiR-155-5p. Mol. Cell. Biochem. 2025, 480, 3019–3032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dang, T.; Liou, G.-Y. Macrophage Cytokines Enhance Cell Proliferation of Normal Prostate Epithelial Cells through Activation of ERK and Akt. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 7718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tu, D.; Dou, J.; Wang, M.; Zhuang, H.; Zhang, X. M2 Macrophages Contribute to Cell Proliferation and Migration of Breast Cancer. Cell Biol. Int. 2021, 45, 831–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Cai, R.; Huang, Y.; Zhu, L.; Xiao, L.; Wang, C.; Wang, L. Macrophages in Organ Fibrosis: From Pathogenesis to Therapeutic Targets. Cell Death Discov. 2024, 10, 487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braga, T.T.; Agudelo, J.S.H.; Camara, N.O.S. Macrophages During the Fibrotic Process: M2 as Friend and Foe. Front. Immunol. 2015, 6, 602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Wang, J.; Chen, Z.; Luo, J.; Guo, W.; Sun, L.; Lin, L. Targeting M2-like Tumor-Associated Macrophages Is a Potential Therapeutic Approach to Overcome Antitumor Drug Resistance. NPJ Precis. Oncol. 2024, 8, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Geng, X.; Hou, J.; Wu, G. New Insights into M1/M2 Macrophages: Key Modulators in Cancer Progression. Cancer Cell Int. 2021, 21, 389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, H.; Meng, X.; Feng, J. Mechanisms of Tumor-Associated Macrophages in Breast Cancer and Treatment Strategy. Front. Immunol. 2025, 16, 1560393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, X.; Wang, Z.; Wang, J.; Li, X.; Wei, H.; Liu, C.; Liu, S.; Zhu, Y.; Feng, C.; Yin, Y.; et al. The Effects of M2 Macrophages-Derived Exosomes on Urethral Fibrosis and Stricture in Scar Formation. ImmunoTargets Ther. 2025, 14, 151–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, R.; Zhang, H.; Tang, B.; Luo, Y.; Yang, Y.; Zhong, X.; Chen, S.; Xu, X.; Huang, S.; Liu, C. Macrophages in Cardiovascular Diseases: Molecular Mechanisms and Therapeutic Targets. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2024, 9, 130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Liu, Y.; Tang, Y.; Xia, Z. Transformation of Macrophages into Myofibroblasts in Fibrosis-Related Diseases: Emerging Biological Concepts and Potential Mechanism. Front. Immunol. 2024, 15, 1474688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, B.; Yang, Y.; Yang, C.; Duan, J.; Chen, L.; Lu, K.; Yi, B.; Chen, Y.; Xu, D.; Huang, H. M2 Macrophage Accumulation Contributes to Pulmonary Fibrosis, Vascular Dilatation, and Hypoxemia in Rat Hepatopulmonary Syndrome. J. Cell. Physiol. 2021, 236, 7682–7697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, J.; Shi, J.; Chen, L.; Lv, Z.; Chen, X.; Cao, H.; Xiang, Z.; Han, X. M2 Macrophages Promote Myofibroblast Differentiation of LR-MSCs and Are Associated with Pulmonary Fibrogenesis. Cell Commun. Signal. 2018, 16, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, M.; Yao, Z.; Xu, L.; Peng, M.; Deng, G.; Liu, L.; Jiang, X.; Cai, X. M2 Macrophage Polarization in Systemic Sclerosis Fibrosis: Pathogenic Mechanisms and Therapeutic Effects. Heliyon 2023, 9, e16206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berridge, M.J.; Lipp, P.; Bootman, M.D. The Versatility and Universality of Calcium Signalling. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2000, 1, 11–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desai, B.N.; Leitinger, N. Purinergic and Calcium Signaling in Macrophage Function and Plasticity. Front. Immunol. 2014, 5, 580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Demaurex, N.; Nunes, P. The Role of STIM and ORAI Proteins in Phagocytic Immune Cells. Am. J. Physiol. Physiol. 2016, 310, C496–C508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beceiro, S.; Radin, J.N.; Chatuvedi, R.; Piazuelo, M.B.; Horvarth, D.J.; Cortado, H.; Gu, Y.; Dixon, B.; Gu, C.; Lange, I.; et al. TRPM2 Ion Channels Regulate Macrophage Polarization and Gastric Inflammation during Helicobacter Pylori Infection. Mucosal Immunol. 2017, 10, 493–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qin, J.; Zhang, X.; Tan, B.; Zhang, S.; Yin, C.; Xue, Q.; Zhang, Z.; Ren, H.; Chen, J.; Liu, M.; et al. Blocking P2X7-Mediated Macrophage Polarization Overcomes Treatment Resistance in Lung Cancer. Cancer Immunol. Res. 2020, 8, 1426–1439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marques-da-Silva, C.; Chaves, M.M.; Rodrigues, J.C.; Corte-Real, S.; Coutinho-Silva, R.; Persechini, P.M. Differential Modulation of ATP-Induced P2X7-Associated Permeabilities to Cations and Anions of Macrophages by Infection with Leishmania Amazonensis. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e25356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pelegrin, P.; Surprenant, A. Dynamics of Macrophage Polarization Reveal New Mechanism to Inhibit IL-1beta Release through Pyrophosphates. EMBO J. 2009, 28, 2114–2127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Layhadi, J.A.; Fountain, S.J. P2X4 Receptor-Dependent Ca(2+) Influx in Model Human Monocytes and Macrophages. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2017, 18, 2261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bkaily, G.; Jacques, D. L-Type Calcium Channel Antagonists and Suppression of Expression of Plasminogen Receptors: Is the Missing Link the L-Type Calcium Channel? Circ. Res. 2009, 105, 112–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molinuevo, M.S.; Etcheverry, S.B.; Cortizo, A.M. Macrophage Activation by a Vanadyl-Aspirin Complex Is Dependent on L-Type Calcium Channel and the Generation of Nitric Oxide. Toxicology 2005, 210, 205–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luciani, D.S.; Gwiazda, K.S.; Yang, T.-L.B.; Kalynyak, T.B.; Bychkivska, Y.; Frey, M.H.Z.; Jeffrey, K.D.; Sampaio, A.V.; Underhill, T.M.; Johnson, J.D. Roles of IP3R and RyR Ca2+ Channels in Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress and Beta-Cell Death. Diabetes 2009, 58, 422–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sermersheim, M.; Kenney, A.D.; Lin, P.-H.; McMichael, T.M.; Cai, C.; Gumpper, K.; Adesanya, T.M.A.; Li, H.; Zhou, X.; Park, K.-H.; et al. MG53 Suppresses Interferon-β and Inflammation via Regulation of Ryanodine Receptor-Mediated Intracellular Calcium Signaling. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 3624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobson, K.A.; Delicado, E.G.; Gachet, C.; Kennedy, C.; von Kügelgen, I.; Li, B.; Miras-Portugal, M.T.; Novak, I.; Schöneberg, T.; Perez-Sen, R.; et al. Update of P2Y Receptor Pharmacology: IUPHAR Review 27. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2020, 177, 2413–2433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klaver, D.; Thurnher, M. Control of Macrophage Inflammation by P2Y Purinergic Receptors. Cells 2021, 10, 1098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merz, J.; Nettesheim, A.; von Garlen, S.; Albrecht, P.; Saller, B.S.; Engelmann, J.; Hertle, L.; Schäfer, I.; Dimanski, D.; König, S.; et al. Pro- and Anti-Inflammatory Macrophages Express a Sub-Type Specific Purinergic Receptor Profile. Purinergic Signal. 2021, 17, 481–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakaki, H.; Tsukimoto, M.; Harada, H.; Moriyama, Y.; Kojima, S. Autocrine Regulation of Macrophage Activation via Exocytosis of ATP and Activation of P2Y11 Receptor. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e59778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gopallawa, I.; Freund, J.R.; Lee, R.J. Bitter Taste Receptors Stimulate Phagocytosis in Human Macrophages through Calcium, Nitric Oxide, and Cyclic-GMP Signaling. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2021, 78, 271–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seegren, P.V.; Harper, L.R.; Downs, T.K.; Zhao, X.-Y.; Viswanathan, S.B.; Stremska, M.E.; Olson, R.J.; Kennedy, J.; Ewald, S.E.; Kumar, P.; et al. Reduced Mitochondrial Calcium Uptake in Macrophages Is a Major Driver of Inflammaging. Nat. Aging 2023, 3, 796–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Okada, H.; Kajiya, H.; Omata, Y.; Matsumoto, T.; Sato, Y.; Kobayashi, T.; Nakamura, S.; Kaneko, Y.; Nakamura, S.; Koyama, T.; et al. CTLA4-Ig Directly Inhibits Osteoclastogenesis by Interfering with Intracellular Calcium Oscillations in Bone Marrow Macrophages. J. Bone Miner. Res. 2019, 34, 1744–1752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hanley, P.J.; Musset, B.; Renigunta, V.; Limberg, S.H.; Dalpke, A.H.; Sus, R.; Heeg, K.M.; Preisig-Müller, R.; Daut, J. Extracellular ATP Induces Oscillations of Intracellular Ca2+ and Membrane Potential and Promotes Transcription of IL-6 in Macrophages. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2004, 101, 9479–9484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Zhang, K.; Wang, L.; Zhu, Z.; Jiang, D.; Zuo, Y.; Yang, J.; Jia, W. Macrophage Intracellular “Calcium Oscillations” Triggered Through In Situ Mineralization Regulate Bone Immunity to Facilitate Bone Repair. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2024, 34, 2316224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Li, X.; Ong, H.; Tan, T.; Park, K.H.; Bian, Z.; Zou, X.; Haggard, E.; Janssen, P.M.; Merritt, R.E.; et al. MG53 Suppresses NF-ΚB Activation to Mitigate Age-Related Heart Failure. JCI Insight 2021, 6, e148375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Ye, H.; Meng, D.-Q.; Cai, P.-C.; Chen, F.; Zhu, L.-P.; Tang, Q.; Long, Z.-X.; Zhou, Q.; Jin, Y.; et al. Reactive Oxygen Species and X-Ray Disrupted Spontaneous [Ca2+]i Oscillation in Alveolar Macrophages. Radiat. Res. 2013, 179, 485–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrithers, L.M.; Hulseberg, P.; Sandor, M.; Carrithers, M.D. The Human Macrophage Sodium Channel NaV1.5 Regulates Mycobacteria Processing through Organelle Polarization and Localized Calcium Oscillations. FEMS Immunol. Med. Microbiol. 2011, 63, 319–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feske, S.; Wulff, H.; Skolnik, E.Y. Ion Channels in Innate and Adaptive Immunity. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 2015, 33, 291–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feske, S. Calcium Signalling in Lymphocyte Activation and Disease. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2007, 7, 690–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muik, M.; Schindl, R.; Fahrner, M.; Romanin, C. Ca(2+) Release-Activated Ca(2+) (CRAC) Current, Structure, and Function. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2012, 69, 4163–4176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feske, S. ORAI1 and STIM1 Deficiency in Human and Mice: Roles of Store-Operated Ca2+ Entry in the Immune System and Beyond. Immunol. Rev. 2009, 231, 189–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, Y.; Huang, X.; Zhang, Y.; Lai, X.; Wu, X.; Zeng, X.; Tang, X.; Zeng, Y. Calcium Influx Blocked by SK&F 96365 Modulates the LPS plus IFN-γ-Induced Inflammatory Response in Murine Peritoneal Macrophages. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2012, 12, 384–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, H.A.; Leech, C.A.; Kopp, R.F.; Roe, M.W. Interplay between ER Ca(2+) Binding Proteins, STIM1 and STIM2, Is Required for Store-Operated Ca(2+) Entry. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 1522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.-W.; Chen, Y.-F.; Chen, Y.-T.; Chiu, W.-T.; Shen, M.-R. The STIM1-Orai1 Pathway of Store-Operated Ca2+ Entry Controls the Checkpoint in Cell Cycle G1/S Transition. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 22142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Zhao, Z.; Gu, M.; Feng, X.; Xu, H. Release and Uptake Mechanisms of Vesicular Ca(2+) Stores. Protein Cell 2019, 10, 8–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cao, Q.; Yang, Y.; Zhong, X.Z.; Dong, X.-P. The Lysosomal Ca(2+) Release Channel TRPML1 Regulates Lysosome Size by Activating Calmodulin. J. Biol. Chem. 2017, 292, 8424–8435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zajac, M.; Mukherjee, S.; Anees, P.; Oettinger, D.; Henn, K.; Srikumar, J.; Zou, J.; Saminathan, A.; Krishnan, Y. A Mechanism of Lysosomal Calcium Entry. Sci. Adv. 2024, 10, eadk2317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, H.; Choi, S.W.; Kim, J.Y.; Oh, S.-J.; Kim, S.J.; Lee, M.-S. ER-to-Lysosome Ca(2+) Refilling Followed by K(+) Efflux-Coupled Store-Operated Ca(2+) Entry in Inflammasome Activation and Metabolic Inflammation. eLife 2024, 12, RP87561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Marchi, U.; Santo-Domingo, J.; Castelbou, C.; Sekler, I.; Wiederkehr, A.; Demaurex, N. NCLX Protein, but Not LETM1, Mediates Mitochondrial Ca2+ Extrusion, Thereby Limiting Ca2+-Induced NAD(P)H Production and Modulating Matrix Redox State. J. Biol. Chem. 2014, 289, 20377–20385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- dos Santos, G.R.R.M.; Cavalcante Queiroz, M.I.; Leite, A.C.R. LETM1 and Mitochondrial Calcium Homeostasis: A Controversial but Critical Role in Cellular Function and Disease. Cell Calcium 2025, 132, 103085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wacquier, B.; Combettes, L.; Dupont, G. Dual Dynamics of Mitochondrial Permeability Transition Pore Opening. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 3924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwong, J.Q.; Molkentin, J.D. Physiological and Pathological Roles of the Mitochondrial Permeability Transition Pore in the Heart. Cell Metab. 2015, 21, 206–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, X.; Zhuang, J.; Song, W.; Shen, W.; Wu, W.; Shen, H.; Han, S. Mitochondria-Associated Endoplasmic Reticulum Membrane: Overview and Inextricable Link with Cancer. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 2023, 27, 906–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barazzuol, L.; Giamogante, F.; Calì, T. Mitochondria Associated Membranes (MAMs): Architecture and Physiopathological Role. Cell Calcium 2021, 94, 102343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Missiroli, S.; Patergnani, S.; Caroccia, N.; Pedriali, G.; Perrone, M.; Previati, M.; Wieckowski, M.R.; Giorgi, C. Mitochondria-Associated Membranes (MAMs) and Inflammation. Cell Death Dis. 2018, 9, 329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Degechisa, S.T.; Dabi, Y.T.; Gizaw, S.T. The Mitochondrial Associated Endoplasmic Reticulum Membranes: A Platform for the Pathogenesis of Inflammation-Mediated Metabolic Diseases. Immunity, Inflamm. Dis. 2022, 10, e647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Csordás, G.; Renken, C.; Várnai, P.; Walter, L.; Weaver, D.; Buttle, K.F.; Balla, T.; Mannella, C.A.; Hajnóczky, G. Structural and Functional Features and Significance of the Physical Linkage between ER and Mitochondria. J. Cell Biol. 2006, 174, 915–921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bernhardt, D.; Müller, M.; Reichert, A.S.; Osiewacz, H.D. Simultaneous Impairment of Mitochondrial Fission and Fusion Reduces Mitophagy and Shortens Replicative Lifespan. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 7885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rieusset, J. The Role of Endoplasmic Reticulum-Mitochondria Contact Sites in the Control of Glucose Homeostasis: An Update. Cell Death Dis. 2018, 9, 388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atakpa-Adaji, P.; Ivanova, A. IP(3)R at ER-Mitochondrial Contact Sites: Beyond the IP(3)R-GRP75-VDAC1 Ca(2+) Funnel. Contact 2023, 6, 25152564231181020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossi, A.; Pizzo, P.; Filadi, R. Calcium, Mitochondria and Cell Metabolism: A Functional Triangle in Bioenergetics. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. Mol. Cell Res. 2019, 1866, 1068–1078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumgartner, H.K.; Gerasimenko, J.V.; Thorne, C.; Ferdek, P.; Pozzan, T.; Tepikin, A.V.; Petersen, O.H.; Sutton, R.; Watson, A.J.M.; Gerasimenko, O. V Calcium Elevation in Mitochondria Is the Main Ca2+ Requirement for Mitochondrial Permeability Transition Pore (MPTP) Opening. J. Biol. Chem. 2009, 284, 20796–20803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rottenberg, H.; Hoek, J.B. The Mitochondrial Permeability Transition: Nexus of Aging, Disease and Longevity. Cells 2021, 10, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elliott, M.R.; Chekeni, F.B.; Trampont, P.C.; Lazarowski, E.R.; Kadl, A.; Walk, S.F.; Park, D.; Woodson, R.I.; Ostankovich, M.; Sharma, P.; et al. Nucleotides Released by Apoptotic Cells Act as a Find-Me Signal to Promote Phagocytic Clearance. Nature 2009, 461, 282–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sawada, K.; Echigo, N.; Juge, N.; Miyaji, T.; Otsuka, M.; Omote, H.; Yamamoto, A.; Moriyama, Y. Identification of a Vesicular Nucleotide Transporter. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2008, 105, 5683–5686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di, A.; Krupa, B.; Nelson, D.J. Calcium-G Protein Interactions in the Regulation of Macrophage Secretion. J. Biol. Chem. 2001, 276, 37124–37132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Lu, N.; Qu, Y.; Liu, W.; Zhong, H.; Tang, N.; Li, J.; Wang, L.; Xi, D.; He, F. Calcium-Sensing Receptor-Mediated Macrophage Polarization Improves Myocardial Remodeling in Spontaneously Hypertensive Rats. Exp. Biol. Med. 2024, 249, 10112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gutiérrez-López, T.Y.; Orduña-Castillo, L.B.; Hernández-Vásquez, M.N.; Vázquez-Prado, J.; Reyes-Cruz, G. Calcium sensing receptor activates the NLRP3 inflammasome via a chaperone-assisted degradative pathway involving Hsp70 and LC3-II. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2018, 505, 1121–1127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, A.; Gessner, J.E.; Varga-Szabo, D.; Syed, S.N.; Konrad, S.; Stegner, D.; Vögtle, T.; Schmidt, R.E.; Nieswandt, B. STIM1 Is Essential for Fcgamma Receptor Activation and Autoimmune Inflammation. Blood 2009, 113, 1097–1104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weber, K.; Schilling, J.D. Lysosomes Integrate Metabolic-Inflammatory Cross-Talk in Primary Macrophage Inflammasome Activation. J. Biol. Chem. 2014, 289, 9158–9171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rojanasakul, Y.; Wang, L.; Malanga, C.J.; Ma, J.Y.; Banks, D.E.; Ma, J.K. Altered Calcium Homeostasis and Cell Injury in Silica-Exposed Alveolar Macrophages. J. Cell. Physiol. 1993, 154, 310–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gleva, G.F.; Goodglick, L.A.; Kane, A.B. Altered Calcium Homeostasis in Irreversibly Injured P388D1 Macrophages. Am. J. Pathol. 1990, 137, 43–57. [Google Scholar]

- Samie, M.; Wang, X.; Zhang, X.; Goschka, A.; Li, X.; Cheng, X.; Gregg, E.; Azar, M.; Zhuo, Y.; Garrity, A.G.; et al. A TRP Channel in the Lysosome Regulates Large Particle Phagocytosis via Focal Exocytosis. Dev. Cell 2013, 26, 511–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reddy, A.; Caler, E.V.; Andrews, N.W. Plasma Membrane Repair Is Mediated by Ca(2+)-Regulated Exocytosis of Lysosomes. Cell 2001, 106, 157–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunes, P.; Demaurex, N. The Role of Calcium Signaling in Phagocytosis. J. Leukoc. Biol. 2010, 88, 57–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmerli, S.; Majeed, M.; Gustavsson, M.; Stendahl, O.; Sanan, D.A.; Ernst, J.D. Phagosome-Lysosome Fusion Is a Calcium-Independent Event in Macrophages. J. Cell Biol. 1996, 132, 49–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di Virgilio, F.; Meyer, B.C.; Greenberg, S.; Silverstein, S.C. Fc Receptor-Mediated Phagocytosis Occurs in Macrophages at Exceedingly Low Cytosolic Ca2+. J. Cell Biol. 1988, 106, 657–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Myers, J.T.; Swanson, J.A. Calcium Spikes in Activated Macrophages during Fcγ Receptor-Mediated Phagocytosis. J. Leukoc. Biol. 2002, 72, 677–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diler, E.; Schwarz, M.; Nickels, R.; Menger, M.D.; Beisswenger, C.; Meier, C.; Tschernig, T. Influence of External Calcium and Thapsigargin on the Uptake of Polystyrene Beads by the Macrophage-like Cell Lines U937 and MH-S. BMC Pharmacol. Toxicol. 2014, 15, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, J.D.; Ko, S.S.; Cohn, Z.A. The Increase in Intracellular Free Calcium Associated with IgG Gamma 2b/Gamma 1 Fc Receptor-Ligand Interactions: Role in Phagocytosis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1984, 81, 5430–5434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leon Guerrero, P.A.; Rasmussen, J.P.; Peterman, E. Calcium Dynamics of Skin-Resident Macrophages during Homeostasis and Tissue Injury. Mol. Biol. Cell 2024, 35, br26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McFadden, M.J.; Reynolds, M.B.; Michmerhuizen, B.C.; Ólafsson, E.B.; Marshall, S.M.; Davis, F.A.; Schultz, T.L.; Iwawaki, T.; Sexton, J.Z.; O’Riordan, M.X.D.; et al. IRE1α Promotes Phagosomal Calcium Flux to Enhance Macrophage Fungicidal Activity. Cell Rep. 2025, 44, 115694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zumerle, S.; Calì, B.; Munari, F.; Angioni, R.; Di Virgilio, F.; Molon, B.; Viola, A. Intercellular Calcium Signaling Induced by ATP Potentiates Macrophage Phagocytosis. Cell Rep. 2019, 27, 1–10.e4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malik, Z.A.; Denning, G.M.; Kusner, D.J. Inhibition of Ca(2+) Signaling by Mycobacterium Tuberculosis Is Associated with Reduced Phagosome-Lysosome Fusion and Increased Survival within Human Macrophages. J. Exp. Med. 2000, 191, 287–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vashi, N.; Andrabi, S.B.A.; Ghanwat, S.; Suar, M.; Kumar, D. Ca(2+)-Dependent Focal Exocytosis of Golgi-Derived Vesicles Helps Phagocytic Uptake in Macrophages. J. Biol. Chem. 2017, 292, 5144–5165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.; Xu, M.; Cao, Q.; Huang, P.; Zhu, X.; Dong, X.-P. A Lysosomal K(+) Channel Regulates Large Particle Phagocytosis by Facilitating Lysosome Ca(2+) Release. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 1038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, H.; Zhao, B.; Chen, J.; Liu, Z.; Li, X.; Li, L.; Wen, H. Mitochondrial Calcium Uniporter Promotes Phagocytosis-Dependent Activation of the NLRP3 Inflammasome. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2022, 119, e2123247119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tedesco, S.; Scattolini, V.; Albiero, M.; Bortolozzi, M.; Avogaro, A.; Cignarella, A.; Fadini, G.P. Mitochondrial Calcium Uptake Is Instrumental to Alternative Macrophage Polarization and Phagocytic Activity. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 4966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murakami, T.; Ockinger, J.; Yu, J.; Byles, V.; McColl, A.; Hofer, A.M.; Horng, T. Critical Role for Calcium Mobilization in Activation of the NLRP3 Inflammasome. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2012, 109, 11282–11287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffmann, A.; Kann, O.; Ohlemeyer, C.; Hanisch, U.-K.; Kettenmann, H. Elevation of Basal Intracellular Calcium as a Central Element in the Activation of Brain Macrophages (Microglia): Suppression of Receptor-Evoked Calcium Signaling and Control of Release Function. J. Neurosci. 2003, 23, 4410–4419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Li, N.; Zhang, X.; Horng, T. Mitochondrial Metabolism Regulates Macrophage Biology. J. Biol. Chem. 2021, 297, 100904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, X.; Tan, G.; Wang, Y.; Chen, L.; Cao, Y.; Si, B.; Zhen, Z.; Li, B.; Jin, Y.; Wang, W.; et al. Mitochondrial Calcium Nanoregulators Reverse the Macrophage Proinflammatory Phenotype Through Restoring Mitochondrial Calcium Homeostasis for the Treatment of Osteoarthritis. Int. J. Nanomed. 2023, 18, 1469–1489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sipka, T.; Peroceschi, R.; Hassan-Abdi, R.; Groß, M.; Ellett, F.; Begon-Pescia, C.; Gonzalez, C.; Lutfalla, G.; Nguyen-Chi, M. Damage-Induced Calcium Signaling and Reactive Oxygen Species Mediate Macrophage Activation in Zebrafish. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 636585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nascimento Da Conceicao, V.; Sun, Y.; Zboril, E.K.; De la Chapa, J.J.; Singh, B.B. Loss of Ca(2+) Entry via Orai-TRPC1 Induces ER Stress, Initiating Immune Activation in Macrophages. J. Cell Sci. 2019, 133, jcs237610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chauhan, A.; Sun, Y.; Sukumaran, P.; Quenum Zangbede, F.O.; Jondle, C.N.; Sharma, A.; Evans, D.L.; Chauhan, P.; Szlabick, R.E.; Aaland, M.O.; et al. M1 Macrophage Polarization Is Dependent on TRPC1-Mediated Calcium Entry. iScience 2018, 8, 85–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nascimento Da Conceicao, V.; Sun, Y.; Ramachandran, K.; Chauhan, A.; Raveendran, A.; Venkatesan, M.; DeKumar, B.; Maity, S.; Vishnu, N.; Kotsakis, G.A.; et al. Resolving Macrophage Polarization through Distinct Ca(2+) Entry Channel That Maintains Intracellular Signaling and Mitochondrial Bioenergetics. iScience 2021, 24, 103339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Azambuja, G.; Moreira Simabuco, F.; Gonçalves de Oliveira, M.C. Macrophage-P2X4 Receptors Pathway Is Essential to Persistent Inflammatory Muscle Hyperalgesia Onset, and Is Prevented by Physical Exercise. PLoS ONE 2025, 20, e0318107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.; Zhao, Y.; Xiao, X.; Fan, Y.; Kloc, M.; Liu, W.; Ghobrial, R.M.; Lan, P.; He, X.; Li, X.C. Graft-Infiltrating Macrophages Adopt an M2 Phenotype and Are Inhibited by Purinergic Receptor P2X7 Antagonist in Chronic Rejection. Am. J. Transplant. 2016, 16, 2563–2573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scherr, B.F.; Reiner, M.F.; Baumann, F.; Höhne, K.; Müller, T.; Ayata, K.; Müller-Quernheim, J.; Idzko, M.; Zissel, G. Prevention of M2 Polarization and Temporal Limitation of Differentiation in Monocytes by Extracellular ATP. BMC Immunol. 2023, 24, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Torre-Minguela, C.; Barberà-Cremades, M.; Gómez, A.I.; Martín-Sánchez, F.; Pelegrín, P. Macrophage Activation and Polarization Modify P2X7 Receptor Secretome Influencing the Inflammatory Process. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 22586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Townsend, E.A.; Guadarrama, A.; Shi, L.; Roti Roti, E.; Denlinger, L.C. P2X(7) Signaling Influences the Production of pro-Resolving and pro-Inflammatory Lipid Mediators in Alveolar Macrophages Derived from Individuals with Asthma. Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell. Mol. Physiol. 2023, 325, L399–L410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, K.; Man, Q.; Miao, J.; Xu, W.; Zheng, Y.; Zhou, X.; Gao, Z. Kir2.1 Channel Regulates Macrophage Polarization via the Ca2+/CaMK II/ERK/NF-ΚB Signaling Pathway. J. Cell Sci. 2022, 135, jcs259544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murthy, S.; Karkossa, I.; Schmidt, C.; Hoffmann, A.; Hagemann, T.; Rothe, K.; Seifert, O.; Anderegg, U.; von Bergen, M.; Schubert, K.; et al. Danger Signal Extracellular Calcium Initiates Differentiation of Monocytes into SPP1/Osteopontin-Producing Macrophages. Cell Death Dis. 2022, 13, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Fan, H.; He, P.; Zhuang, H.; Liu, X.; Chen, M.; Zhong, W.; Zhang, Y.; Zhen, C.; Li, Y.; et al. Prohibitin 1 Regulates MtDNA Release and Downstream Inflammatory Responses. EMBO J. 2022, 41, e111173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Wang, H.; Fu, M.; Yang, L.; Chen, X.; Wang, Z.; Liu, J.; Sun, H. Mechanistic Insights into TSH-Mediated Macrophage Mitochondrial Dysfunction via TSHR Signaling in Metabolic Disorders. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2025, 240, 783–793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, Z.; Deng, Y.; Luo, H.; Liu, C.; Yang, M.; Xue, H.; Chen, Z. Progress of Tanshinone IIA against Respiratory Diseases: Therapeutic Targets and Potential Mechanisms. Front. Pharmacol. 2025, 16, 1505672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, R.; Yazdi, A.S.; Menu, P.; Tschopp, J. A Role for Mitochondria in NLRP3 Inflammasome Activationc. Nature 2011, 469, 221–225, Erratum in Nature 2011, 475, 122.. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Q.; Wang, Y.; Lu, Z.; He, C.; Li, L.; You, M.; Wang, L.; Cao, T.; Zhao, Y.; Li, Q.; et al. Cx43 Acts as a Mitochondrial Calcium Regulator That Promotes Obesity by Inducing the Polarization of Macrophages in Adipose Tissue. Cell. Signal. 2023, 105, 110606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assis, L.H.d.P.; Dorighello, G.d.G.; Oliveira, H.C.F.d. Pro-Inflammatory Polarization of Macrophages Is Associated with Reduced Endoplasmic Reticulum-Mitochondria Interaction. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2022, 606, 61–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guiducci, C.; Vicari, A.P.; Sangaletti, S.; Trinchieri, G.; Colombo, M.P. Redirecting in Vivo Elicited Tumor Infiltrating Macrophages and Dendritic Cells towards Tumor Rejection. Cancer Res. 2005, 65, 3437–3446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagemann, T.; Lawrence, T.; McNeish, I.; Charles, K.A.; Kulbe, H.; Thompson, R.G.; Robinson, S.C.; Balkwill, F.R. “Re-Educating” Tumor-Associated Macrophages by Targeting NF-KappaB. J. Exp. Med. 2008, 205, 1261–1268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanson, M.; Distel, E.; Fisher, E.A. HDL Induces the Expression of the M2 Macrophage Markers Arginase 1 and Fizz-1 in a STAT6-Dependent Process. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e74676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tentillier, N.; Etzerodt, A.; Olesen, M.N.; Rizalar, F.S.; Jacobsen, J.; Bender, D.; Moestrup, S.K.; Romero-Ramos, M. Anti-Inflammatory Modulation of Microglia via CD163-Targeted Glucocorticoids Protects Dopaminergic Neurons in the 6-OHDA Parkinson’s Disease Model. J. Neurosci. 2016, 36, 9375–9390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adib, Y.; Serror, K.; Pinzon, J.A.; Duciel, L.; Delagrange, M.; Ducos, B.; Boccara, D.; Mimoun, M.; Chaouat, M.; Bensussan, A.; et al. In Vitro Modulation of Macrophage Inflammatory and Pro-Repair Properties Essential for Wound Healing by Calcium and Calcium-Alginate Dressings. Cells 2025, 14, 909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiao, L.; Shiwaku, Y.; Hamai, R.; Tsuchiya, K.; Sasaki, K.; Suzuki, O. Macrophage Polarization Related to Crystal Phases of Calcium Phosphate Biomaterials. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 11252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, J.; Zhou, Y.; Lin, X.; Li, H. Macrophage Polarization Related to Biomimetic Calcium Phosphate Coatings: A Preliminary Study. Materials 2022, 16, 332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jin, C.; Liang, J.; Wu, J.; Han, X.; Zhou, Y.; Li, B.; Sun, W.; Su, J.; Sun, J.; Wan, S.; et al. Temporal Immunomodulatory Hydrogel Regulating the Immune-Osteogenic Cascade for Infected Bone Defects Regeneration. Adv. Mater. 2025, e14419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, Q.; Gong, Z.; Wang, J.; Fu, L.; Zhang, J.; Wang, C.; Miron, R.J.; Yuan, Q.; Zhang, Y. A Zinc- and Calcium-Rich Lysosomal Nanoreactor Rescues Monocyte/Macrophage Dysfunction under Sepsis. Adv. Sci. 2023, 10, e2205097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, H.; Zhang, K.; Wong, D.S.H.; Han, F.; Li, B.; Bian, L. Near-Infrared Light-Controlled Regulation of Intracellular Calcium to Modulate Macrophage Polarization. Biomaterials 2018, 178, 681–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Provost, K.A.; Smith, M.; Arold, S.P.; Hava, D.L.; Sethi, S. Calcium Restores the Macrophage Response to Nontypeable Haemophilus Influenzae in Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 2015, 52, 728–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arfath, Y.; Kotra, T.; Faizan, M.I.; Akhtar, A.; Abdullah, S.T.; Ahmad, T.; Ahmed, Z.; Rayees, S. TRPV4 Facilitates the Reprogramming of Inflamed Macrophages by Regulating IL-10 Production via CREB. Inflamm. Res. 2024, 73, 1687–1697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nasrallah, C.M.; Horvath, T.L. Mitochondrial Dynamics in the Central Regulation of Metabolism. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 2014, 10, 650–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weinberg, S.E.; Sena, L.A.; Chandel, N.S. Mitochondria in the Regulation of Innate and Adaptive Immunity. Immunity 2015, 42, 406–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, S.; Cao, L.; Huang, C.; Wang, J.; Liu, J.; Wang, Y.; Wang, Q.; Zhou, Q.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, D. Amorphous Calcium Zinc Phosphate Promotes Macrophage-Driven Alveolar Bone Regeneration via Modulation of Energy Metabolism and Mitochondrial Homeostasis. Bioact. Mater. 2025, 52, 829–844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feno, S.; Munari, F.; Reane, D.V.; Gissi, R.; Hoang, D.-H.; Castegna, A.; Chazaud, B.; Viola, A.; Rizzuto, R.; Raffaello, A. The Dominant-Negative Mitochondrial Calcium Uniporter Subunit MCUb Drives Macrophage Polarization during Skeletal Muscle Regeneration. Sci. Signal. 2021, 14, eabf3838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Q.; Shen, X.; Wang, P.; Ma, J.; Sha, W. Targeting Cyclophilin-D by MiR-1281 Protects Human Macrophages from Mycobacterium Tuberculosis-Induced Programmed Necrosis and Apoptosis. Aging 2019, 11, 12661–12673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Chen, L.; Liu, J.-Y.; Liu, T.; Wang, R.; Wu, X.-Y.; Li, S.-W. MPTP Mediated Ox-MtDNA Release Inducing Macrophage Pyroptosis and Exacerbating MCD-Induced MASH via Promoting the ITPR3/Ca(2+)/NLRP3 Pathway. J. Transl. Med. 2025, 23, 1289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Pogonyalova, M.Y.; Popov, D.Y.; Vinokurov, A.Y. Intracellular Calcium as a Regulator of Polarization and Target Reprogramming of Macrophages. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 11901. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262411901

Pogonyalova MY, Popov DY, Vinokurov AY. Intracellular Calcium as a Regulator of Polarization and Target Reprogramming of Macrophages. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2025; 26(24):11901. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262411901

Chicago/Turabian StylePogonyalova, Marina Y., Daniil Y. Popov, and Andrey Y. Vinokurov. 2025. "Intracellular Calcium as a Regulator of Polarization and Target Reprogramming of Macrophages" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 26, no. 24: 11901. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262411901

APA StylePogonyalova, M. Y., Popov, D. Y., & Vinokurov, A. Y. (2025). Intracellular Calcium as a Regulator of Polarization and Target Reprogramming of Macrophages. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 26(24), 11901. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262411901