The Current Landscape of Modular CAR T Cells

Abstract

1. Introduction

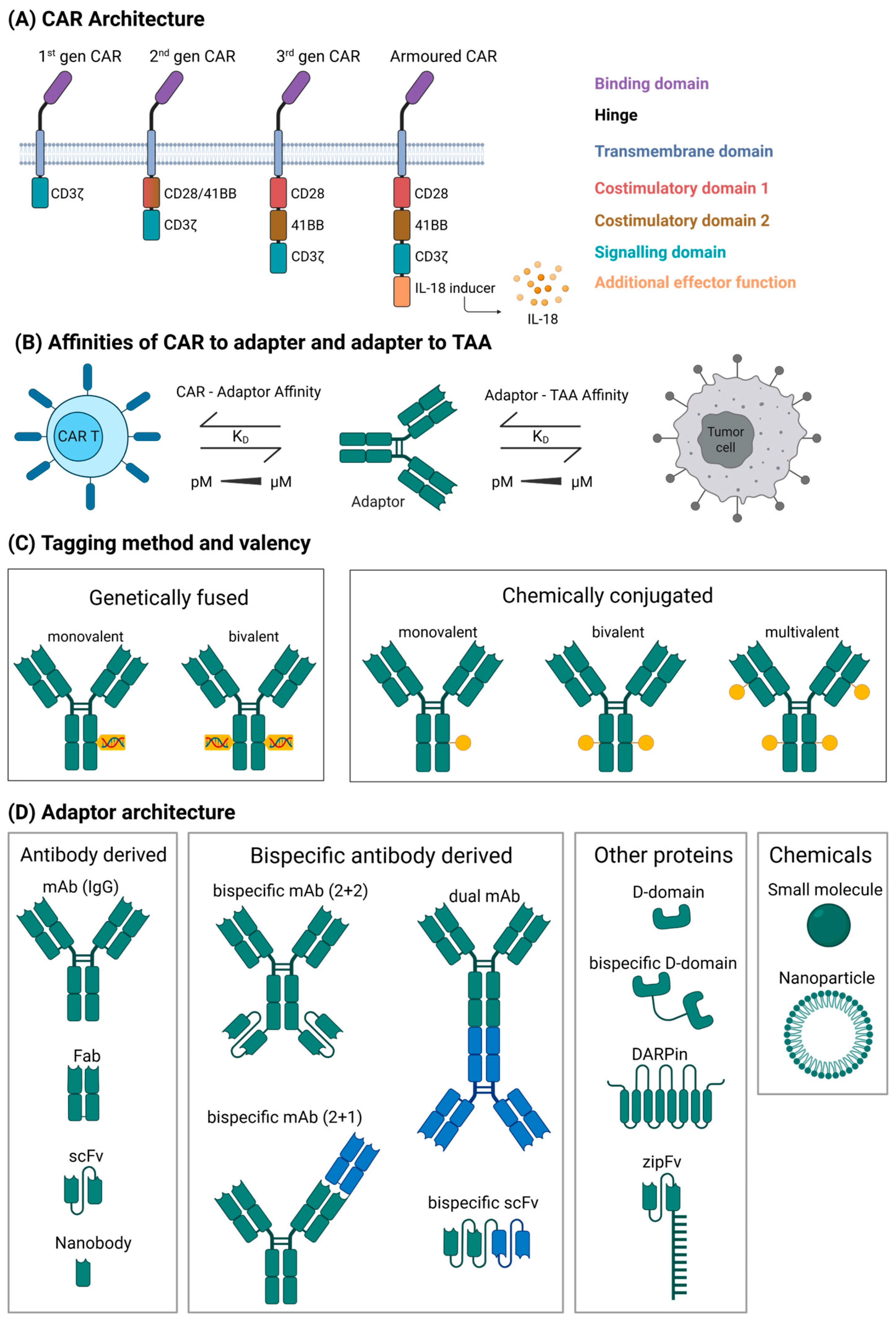

2. Modular CAR Terminology and Category

- Peptide tags: These tags are usually small peptides genetically fused to the AM and a corresponding antibody-derived binding domain on the CAR. Examples are the UniCAR [15] recognising a peptide derived from the La/SS-B autoantigen or the PNE CAR [16] recognising a yeast transcription factor-derived tag. A variation of this system has a binding domain and protein epitope switched so that the CAR expresses the tag and the AM contains the binding domain.

- Ab domain recognition: A different strategy for designing modular CAR systems is to use CAR T cells specific to antibody domains, mainly the Fc domain in the context of full-size antibodies or antibody fragments. Examples are CD16-derived CARs that bind Fc domains [22,23], the P329G mutated Fc-domain with a CAR specific to this mutation [24], artificial epitopes (“meditopes”) inserted between light and heavy chains [25], or a protein G-derived CAR-AM combination [26].

- Covalent bond: This type of interaction relies on the formation of a covalent bond between CAR and AM after coupling, resulting in a strong activation signal but less flexibility to swap out the AM. The systems in this category use bacterial or other proteins capable of spontaneously forming covalent bonds [27,28,29].

3. Landscape of Modular CAR Constructs

3.1. UniCAR

3.2. PNE-CAR

3.3. Other Peptide-Based CARs

3.4. Biotin-Based CAR

3.5. FITC-Based CAR

3.6. CD16-Based CAR

3.7. Antibody Domain Recognising CAR

3.8. Covalent Bond

3.9. Engineered Protein Pair CAR

4. Clinical Landscape

5. Key Design Factors for Modular CAR Systems

5.1. Affinity

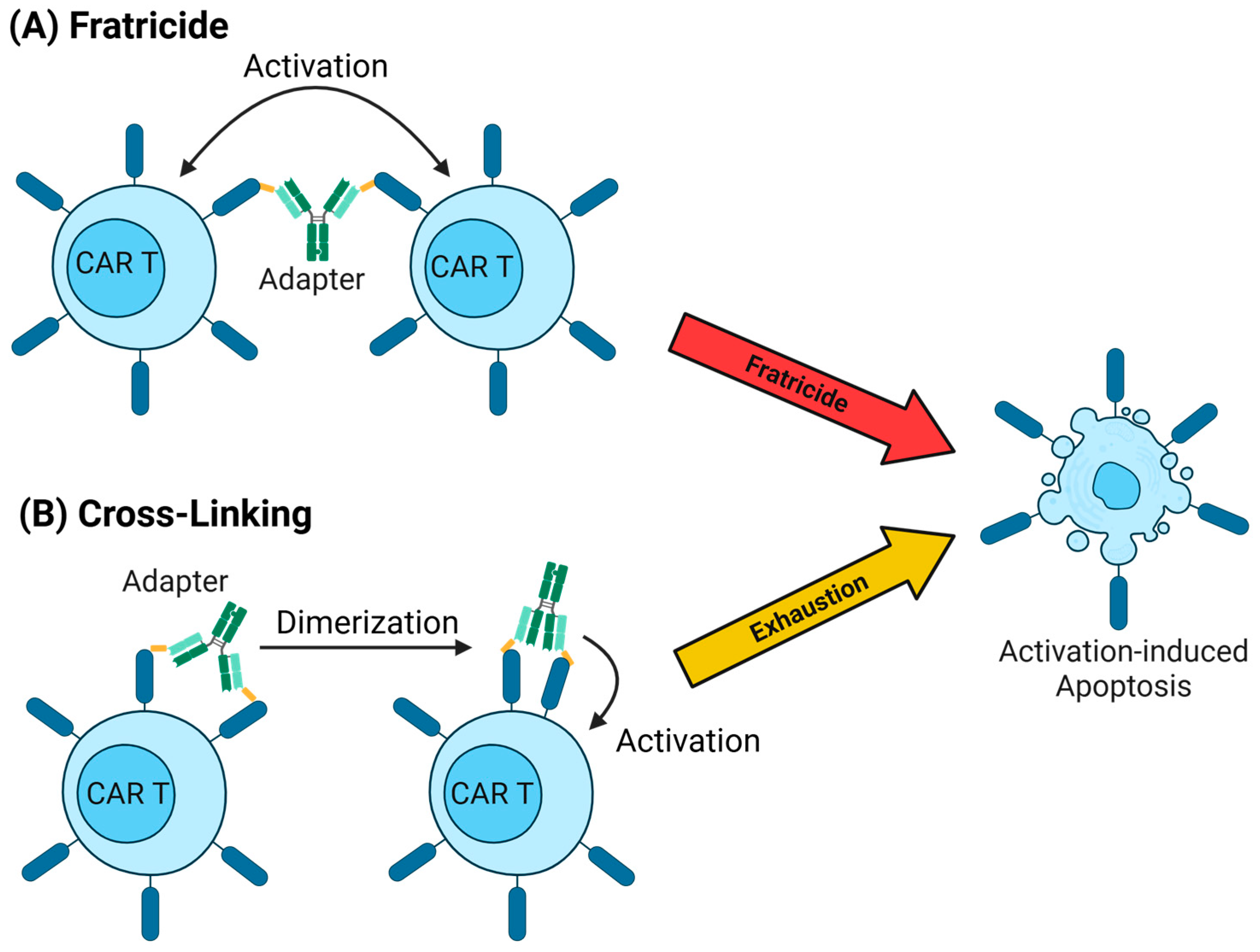

5.2. Tonic Signalling

5.3. Adaptor Pharmacokinetics

5.4. Valency

5.5. Immunogenicity

5.6. On-Target, Off-Tumour Toxicity

5.7. Further Safety and Control Mechanisms

5.8. Future Directions

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Glossary

| AA | Amino acid |

| ACTR | Antibody coupled T-cell receptor |

| ALL | Acute lymphoid leukaemia |

| AM | Adaptor molecule |

| AML | Acute myeloid leukaemia |

| ADA | Anti-drug-antibodies |

| AFP | Alpha-fetoprotein |

| ARC | Antigen–receptor complex |

| BBIR | Biotin-binding immune receptor |

| BCL-2 | B-cell lymphoma 2 |

| BG | Benzylguanine |

| Bim | Bcl2-interacting mediator of cell death |

| BsAb-IR | BsAb-binding immune receptor |

| BsCAR | Barnase/barstar-based CAR |

| CAR | Chimeric antigen receptor |

| CA IX | Carbonic anhydrase IX |

| CL | Constant light chain |

| CRS | Cytokine release syndrome |

| DARPins | Designed ankyrin repeat proteins |

| DLT | Dose-limiting toxicity |

| EC50 | Effective concentration |

| EGFR | Epidermal growth factor receptor |

| F-AgNPs | Fusogenic antigen loading nanoparticles |

| FGFR2 | Fibroblast growth factor receptor 2 |

| FITC | Fluorescein isothiocyanate |

| FOLR1/FRα | Folate receptor 1/alpha |

| Gv | GvOptiTag |

| iNKG2D | Inert NKG2D variant |

| ICANS | Immune effector cell-associated neurotoxicity syndrome |

| LLE | Linker–label epitope |

| MDS | Myelodysplastic syndrome |

| MM | Multiple myeloma |

| mSA2 | Monomeric streptavidin 2 |

| MU-CAR-T | Modular universal CAR T |

| ORR | Overall response rate |

| PR | Partial response |

| sCAR-T | Switchable CAR-T-cell |

| Sd | SDCatcher |

| TAA | Tumour-associated antigen |

| TMEFF2 | Tomoregulin-2 |

| OT-OT | On-target–off-tumour |

| O6-BG | O6-benzylguanine |

| PNE | Peptide neo epitope |

| PSCA | Prostate stem cell antigen |

| PSMA | Prostate-specific membrane antigen |

References

- Maude, S.L.; Laetsch, T.W.; Buechner, J.; Rives, S.; Boyer, M.; Bittencourt, H.; Bader, P.; Verneris, M.R.; Stefanski, H.E.; Myers, G.D.; et al. Tisagenlecleucel in Children and Young Adults with B-Cell Lymphoblastic Leukemia. N. Engl. J. Med. 2018, 378, 439–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhaskar, S.T.; Dholaria, B.; Savani, B.N.; Sengsayadeth, S.; Oluwole, O. Overview of approved CAR-T products and utility in clinical practice. Clin. Hematol. Int. 2024, 6, 93–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munshi, N.C.; Anderson, L.D., Jr.; Shah, N.; Madduri, D.; Berdeja, J.; Lonial, S.; Raje, N.; Lin, Y.; Siegel, D.; Oriol, A.; et al. Idecabtagene Vicleucel in Relapsed and Refractory Multiple Myeloma. N. Engl. J. Med. 2021, 384, 705–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Svoboda, J.; Landsburg, D.J.; Gerson, J.; Nasta, S.D.; Barta, S.K.; Chong, E.A.; Cook, M.; Frey, N.V.; Shea, J.; Cervini, A.; et al. Enhanced CAR T-Cell Therapy for Lymphoma after Previous Failure. N. Engl. J. Med. 2025, 392, 1824–1835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bot, A.; Scharenberg, A.; Friedman, K.; Guey, L.; Hofmeister, R.; Andorko, J.I.; Klichinsky, M.; Neumann, F.; Shah, J.V.; Swayer, A.J.; et al. In vivo chimeric antigen receptor (CAR)-T cell therapy. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2025, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, C.; Liu, C.; Peng, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Wei, J.; Qiu, W.; Zhang, X.; Pan, H.; Niu, Z.; Qiu, M.; et al. Claudin-18 isoform 2-specific CAR T-cell therapy (satri-cel) versus treatment of physician’s choice for previously treated advanced gastric or gastro-oesophageal junction cancer (CT041-ST-01): A randomised, open-label, phase 2 trial. Lancet 2025, 405, 2049–2060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mougiakakos, D.; Kronke, G.; Volkl, S.; Kretschmann, S.; Aigner, M.; Kharboutli, S.; Boltz, S.; Manger, B.; Mackensen, A.; Schett, G. CD19-Targeted CAR T Cells in Refractory Systemic Lupus Erythematosus. N. Engl. J. Med. 2021, 385, 567–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brudno, J.N.; Maus, M.V.; Hinrichs, C.S. CAR T Cells and T-Cell Therapies for Cancer: A Translational Science Review. JAMA 2024, 332, 1924–1935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sterner, R.C.; Sterner, R.M. CAR-T cell therapy: Current limitations and potential strategies. Blood Cancer J. 2021, 11, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clemenceau, B.; Congy-Jolivet, N.; Gallot, G.; Vivien, R.; Gaschet, J.; Thibault, G.; Vie, H. Antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity (ADCC) is mediated by genetically modified antigen-specific human T lymphocytes. Blood 2006, 107, 4669–4677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, D.L.; Koehl, U.; Chmielewski, M.; Scheid, C.; Stripecke, R. Review: Sustainable Clinical Development of CAR-T Cells-Switching from Viral Transduction Towards CRISPR-Cas Gene Editing. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 865424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boettcher, M.; Joechner, A.; Li, Z.; Yang, S.F.; Schlegel, P. Development of CAR T Cell Therapy in Children—A Comprehensive Overview. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11, 2158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadelain, M.; Brentjens, R.; Riviere, I. The basic principles of chimeric antigen receptor design. Cancer Discov. 2013, 3, 388–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.; Wang, Y.; Jin, X.; Wang, L. Universal CAR cell therapy: Challenges and expanding applications. Transl. Oncol. 2025, 51, 102147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cartellieri, M.; Feldmann, A.; Koristka, S.; Arndt, C.; Loff, S.; Ehninger, A.; von Bonin, M.; Bejestani, E.P.; Ehninger, G.; Bachmann, M.P. Switching CAR T cells on and off: A novel modular platform for retargeting of T cells to AML blasts. Blood Cancer J. 2016, 6, e458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodgers, D.T.; Mazagova, M.; Hampton, E.N.; Cao, Y.; Ramadoss, N.S.; Hardy, I.R.; Schulman, A.; Du, J.; Wang, F.; Singer, O.; et al. Switch-mediated activation and retargeting of CAR-T cells for B-cell malignancies. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2016, 113, E459–E468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, J.S.; Kim, J.Y.; Kazane, S.A.; Choi, S.H.; Yun, H.Y.; Kim, M.S.; Rodgers, D.T.; Pugh, H.M.; Singer, O.; Sun, S.B.; et al. Versatile strategy for controlling the specificity and activity of engineered T cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2016, 113, E450–E458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.G.; Marks, I.; Srinivasarao, M.; Kanduluru, A.K.; Mahalingam, S.M.; Liu, X.; Chu, H.; Low, P.S. Use of a Single CAR T Cell and Several Bispecific Adapters Facilitates Eradication of Multiple Antigenically Different Solid Tumors. Cancer Res. 2019, 79, 387–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seitz, C.M.; Mittelstaet, J.; Atar, D.; Hau, J.; Reiter, S.; Illi, C.; Kieble, V.; Engert, F.; Drees, B.; Bender, G.; et al. Novel adapter CAR-T cell technology for precisely controllable multiplex cancer targeting. Oncoimmunology 2021, 10, 2003532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lohmueller, J.J.; Ham, J.D.; Kvorjak, M.; Finn, O.J. mSA2 affinity-enhanced biotin-binding CAR T cells for universal tumor targeting. Oncoimmunology 2017, 7, e1368604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urbanska, K.; Lanitis, E.; Poussin, M.; Lynn, R.C.; Gavin, B.P.; Kelderman, S.; Yu, J.; Scholler, N.; Powell, D.J., Jr. A universal strategy for adoptive immunotherapy of cancer through use of a novel T-cell antigen receptor. Cancer Res. 2012, 72, 1844–1852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kudo, K.; Imai, C.; Lorenzini, P.; Kamiya, T.; Kono, K.; Davidoff, A.M.; Chng, W.J.; Campana, D. T lymphocytes expressing a CD16 signaling receptor exert antibody-dependent cancer cell killing. Cancer Res. 2014, 74, 93–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rataj, F.; Jacobi, S.J.; Stoiber, S.; Asang, F.; Ogonek, J.; Tokarew, N.; Cadilha, B.L.; van Puijenbroek, E.; Heise, C.; Duewell, P.; et al. High-affinity CD16-polymorphism and Fc-engineered antibodies enable activity of CD16-chimeric antigen receptor-modified T cells for cancer therapy. Br. J. Cancer 2019, 120, 79–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stock, S.; Benmebarek, M.R.; Kluever, A.K.; Darowski, D.; Jost, C.; Stubenrauch, K.G.; Benz, J.; Freimoser-Grundschober, A.; Moessner, E.; Umana, P.; et al. Chimeric antigen receptor T cells engineered to recognize the P329G-mutated Fc part of effector-silenced tumor antigen-targeting human IgG1 antibodies enable modular targeting of solid tumors. J. Immunother. Cancer 2022, 10, e005054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuo, Y.C.; Kuo, C.F.; Jenkins, K.; Hung, A.F.; Chang, W.C.; Park, M.; Aguilar, B.; Starr, R.; Hibbard, J.; Brown, C.; et al. Antibody-based redirection of universal Fabrack-CAR T cells selectively kill antigen bearing tumor cells. J. Immunother. Cancer 2022, 10, 003752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arina, A.; Arauz, E.; Masoumi, E.; Warzecha, K.W.; Saaf, A.; Widlo, L.; Slezak, T.; Zieminska, A.; Dudek, K.; Schaefer, Z.P.; et al. A universal chimeric antigen receptor (CAR)-fragment antibody binder (FAB) split system for cancer immunotherapy. Sci. Adv. 2025, 11, eadv4937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stepanov, A.V.; Kalinin, R.S.; Shipunova, V.O.; Zhang, D.; Xie, J.; Rubtsov, Y.P.; Ukrainskaya, V.M.; Schulga, A.; Konovalova, E.V.; Volkov, D.V.; et al. Switchable targeting of solid tumors by BsCAR T cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2022, 119, e2210562119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.; Deng, J.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, B.; Liu, R.; Zhu, Y.; Zhou, M.; Lin, Y.; Xia, B.; Lin, K.; et al. The construction of modular universal chimeric antigen receptor T (MU-CAR-T) cells by covalent linkage of allogeneic T cells and various antibody fragments. Mol. Cancer 2024, 23, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minutolo, N.G.; Sharma, P.; Poussin, M.; Shaw, L.C.; Brown, D.P.; Hollander, E.E.; Smole, A.; Rodriguez-Garcia, A.; Hui, J.Z.; Zappala, F.; et al. Quantitative Control of Gene-Engineered T-Cell Activity through the Covalent Attachment of Targeting Ligands to a Universal Immune Receptor. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2020, 142, 6554–6568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, J.H.; Collins, J.J.; Wong, W.W. Universal Chimeric Antigen Receptors for Multiplexed and Logical Control of T Cell Responses. Cell 2018, 173, 1426–1438.E11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lajoie, M.J.; Boyken, S.E.; Salter, A.I.; Bruffey, J.; Rajan, A.; Langan, R.A.; Olshefsky, A.; Muhunthan, V.; Bick, M.J.; Gewe, M.; et al. Designed protein logic to target cells with precise combinations of surface antigens. Science 2020, 369, 1637–1643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landgraf, K.E.; Williams, S.R.; Steiger, D.; Gebhart, D.; Lok, S.; Martin, D.W.; Roybal, K.T.; Kim, K.C. convertibleCARs: A chimeric antigen receptor system for flexible control of activity and antigen targeting. Commun. Biol. 2020, 3, 296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albert, S.; Arndt, C.; Feldmann, A.; Bergmann, R.; Bachmann, D.; Koristka, S.; Ludwig, F.; Ziller-Walter, P.; Kegler, A.; Gartner, S.; et al. A novel nanobody-based target module for retargeting of T lymphocytes to EGFR-expressing cancer cells via the modular UniCAR platform. Oncoimmunology 2017, 6, e1287246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Knelangen, N.; Bader, U.; Maniaki, E.; Langan, P.S.; Engert, F.; Drees, B.; Schwarzer, J.; Kotter, B.; Kiefer, L.; Gattinoni, L.; et al. CAR T cells re-directed by a rationally designed human peptide tag demonstrate efficacy in preclinical models. Cytotherapy 2025, 27, 1094–1104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, J.; Tsuji, K.; Hymel, D.; Burke, T.R., Jr.; Hudecek, M.; Rader, C.; Peng, H. Chemically Programmable and Switchable CAR-T Therapy. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2020, 59, 12178–12185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karches, C.H.; Benmebarek, M.R.; Schmidbauer, M.L.; Kurzay, M.; Klaus, R.; Geiger, M.; Rataj, F.; Cadilha, B.L.; Lesch, S.; Heise, C.; et al. Bispecific Antibodies Enable Synthetic Agonistic Receptor-Transduced T Cells for Tumor Immunotherapy. Clin. Cancer Res. 2019, 25, 5890–5900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kittel-Boselli, E.; Soto, K.E.G.; Loureiro, L.R.; Hoffmann, A.; Bergmann, R.; Arndt, C.; Koristka, S.; Mitwasi, N.; Kegler, A.; Bartsch, T.; et al. Targeting Acute Myeloid Leukemia Using the RevCAR Platform: A Programmable, Switchable and Combinatorial Strategy. Cancers 2021, 13, 4785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borrok, M.J.; Li, Y.; Harvilla, P.B.; Vellalore Maruthachalam, B.; Tamot, N.; Prokopowitz, C.; Chen, J.; Venkataramani, S.; Grewal, I.S.; Ganesan, R.; et al. Conduit CAR: Redirecting CAR T-Cell Specificity with A Universal and Adaptable Bispecific Antibody Platform. Cancer Res. Commun. 2022, 2, 146–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Z.; Li, R.; Shen, Y.; Tan, S.; Ding, N.; Xu, R.; Wang, X.; Wei, J.; Liu, B.; Meng, F. In situ antigen modification-based target-redirected universal chimeric antigen receptor T (TRUE CAR-T) cell therapy in solid tumors. J. Hematol. Oncol. 2022, 15, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.J.; Chu, H.; Wheeler, L.W.; Nelson, M.; Westrick, E.; Matthaei, J.F.; Cardle, I.I.; Johnson, A.; Gustafson, J.; Parker, N.; et al. Preclinical Evaluation of Bispecific Adaptor Molecule Controlled Folate Receptor CAR-T Cell Therapy with Special Focus on Pediatric Malignancies. Front. Oncol. 2019, 9, 151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, A.Q.; Hostetler, A.; Chen, L.E.; Mukkamala, V.; Abraham, W.; Padilla, L.T.; Wolff, A.N.; Maiorino, L.; Backlund, C.M.; Aung, A.; et al. Universal redirection of CAR T cells against solid tumours via membrane-inserted ligands for the CAR. Nat. Biomed. Eng. 2023, 7, 1113–1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urbanska, K.; Lynn, R.C.; Stashwick, C.; Thakur, A.; Lum, L.G.; Powell, D.J., Jr. Targeted cancer immunotherapy via combination of designer bispecific antibody and novel gene-engineered T cells. J. Transl. Med. 2014, 12, 347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ochi, F.; Fujiwara, H.; Tanimoto, K.; Asai, H.; Miyazaki, Y.; Okamoto, S.; Mineno, J.; Kuzushima, K.; Shiku, H.; Barrett, J.; et al. Gene-modified human alpha/beta-T cells expressing a chimeric CD16-CD3zeta receptor as adoptively transferable effector cells for anticancer monoclonal antibody therapy. Cancer Immunol. Res. 2014, 2, 249–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Aloia, M.M.; Caratelli, S.; Palumbo, C.; Battella, S.; Arriga, R.; Lauro, D.; Palmieri, G.; Sconocchia, G.; Alimandi, M. T lymphocytes engineered to express a CD16-chimeric antigen receptor redirect T-cell immune responses against immunoglobulin G-opsonized target cells. Cytotherapy 2016, 18, 278–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ambrose, C.; Su, L.; Wu, L.; Dufort, F.J.; Sanford, T.; Birt, A.; Hackel, B.J.; Hombach, A.; Abken, H.; Lobb, R.R.; et al. Anti-CD19 CAR T cells potently redirected to kill solid tumor cells. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0247701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruffo, E.; Butchy, A.A.; Tivon, Y.; So, V.; Kvorjak, M.; Parikh, A.; Adams, E.L.; Miskov-Zivanov, N.; Finn, O.J.; Deiters, A.; et al. Post-translational covalent assembly of CAR and synNotch receptors for programmable antigen targeting. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 2463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, J.P.; Swers, J.S.; Buonato, J.M.; Zaritskaya, L.; Mu, C.J.; Gupta, A.; Shachar, S.; LaFleur, D.W.; Richman, L.K.; Tice, D.A.; et al. Controlling CAR-T cell activity and specificity with synthetic SparX adapters. Mol. Ther. 2024, 32, 1835–1848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bachmann, M. The UniCAR system: A modular CAR T cell approach to improve the safety of CAR T cells. Immunol. Lett. 2019, 211, 13–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boutier, H.; Loureiro, L.R.; Hoffmann, L.; Arndt, C.; Bartsch, T.; Feldmann, A.; Bachmann, M.P. UniCAR T-Cell Potency-A Matter of Affinity between Adaptor Molecules and Adaptor CAR T-Cells? Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 7242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feldmann, A.; Hoffmann, A.; Bergmann, R.; Koristka, S.; Berndt, N.; Arndt, C.; Rodrigues Loureiro, L.; Kittel-Boselli, E.; Mitwasi, N.; Kegler, A.; et al. Versatile chimeric antigen receptor platform for controllable and combinatorial T cell therapy. Oncoimmunology 2020, 9, 1785608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koristka, S.; Ziller-Walter, P.; Bergmann, R.; Arndt, C.; Feldmann, A.; Kegler, A.; Cartellieri, M.; Ehninger, A.; Ehninger, G.; Bornhauser, M.; et al. Anti-CAR-engineered T cells for epitope-based elimination of autologous CAR T cells. Cancer Immunol. Immunother. 2019, 68, 1401–1415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wermke, M.; Metzelder, S.; Kraus, S.; Sala, E.; Vucinic, V.; Fiedler, W.; Wetzko, K.; Schäfer, J.; Goebeler, M.-E.; Koedam, J.; et al. Updated Results from a Phase I Dose Escalation Study of the Rapidly-Switchable Universal CAR-T Therapy UniCAR-T-CD123 in Relapsed/Refractory AML. Blood 2023, 142, 3465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahnd, C.; Spinelli, S.; Luginbuhl, B.; Amstutz, P.; Cambillau, C.; Pluckthun, A. Directed in vitro evolution and crystallographic analysis of a peptide-binding single chain antibody fragment (scFv) with low picomolar affinity. J. Biol. Chem. 2004, 279, 18870–18877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cao, Y.; Rodgers, D.T.; Du, J.; Ahmad, I.; Hampton, E.N.; Ma, J.S.; Mazagova, M.; Choi, S.H.; Yun, H.Y.; Xiao, H.; et al. Design of Switchable Chimeric Antigen Receptor T Cells Targeting Breast Cancer. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2016, 55, 7520–7524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nikolaenko, L.; Mulroney, C.; Riedell, P.A.; Flinn, I.W.; Cruz, J.C.; Vaidya, R.; van Besien, K.; Emde, M.; Klyushnichenko, V.; Strauss, J.; et al. First in Human Study of an on/Off Switchable CAR-T Cell Platform Targeting CD19 for B Cell Malignancies (CLBR001 + SWI019). Blood 2021, 138, 2822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, T. Calibr Reports Promising Results from First-in-Human Clinical Trial of Switchable Car-T (Clbr001 + Swi019), A Next-Generation Universal Car-T Platform Designed to Enhance the Versatility and Safety of Cell Therapies; Scripps Research: San Diego, CA, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Rader, C.; Turner, J.M.; Heine, A.; Shabat, D.; Sinha, S.C.; Wilson, I.A.; Lerner, R.A.; Barbas, C.F. A humanized aldolase antibody for selective chemotherapy and adaptor immunotherapy. J. Mol. Biol. 2003, 332, 889–899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Y.; Nymoen, D.A.; Dong, H.P.; Bjorang, O.; Shih Ie, M.; Low, P.S.; Trope, C.G.; Davidson, B. Expression of the folate receptor genes FOLR1 and FOLR3 differentiates ovarian carcinoma from breast carcinoma and malignant mesothelioma in serous effusions. Hum. Pathol. 2009, 40, 1453–1460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donaldson, J.M.; Zer, C.; Avery, K.N.; Bzymek, K.P.; Horne, D.A.; Williams, J.C. Identification and grafting of a unique peptide-binding site in the Fab framework of monoclonal antibodies. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2013, 110, 17456–17461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zer, C.; Avery, K.N.; Meyer, K.; Goodstein, L.; Bzymek, K.P.; Singh, G.; Williams, J.C. Engineering a high-affinity peptide binding site into the anti-CEA mAb M5A. Protein Eng. Des. Sel. 2017, 30, 409–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bird, R.E.; Hardman, K.D.; Jacobson, J.W.; Johnson, S.; Kaufman, B.M.; Lee, S.M.; Lee, T.; Pope, S.H.; Riordan, G.S.; Whitlow, M. Single-chain antigen-binding proteins. Science 1988, 242, 423–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hombach, A.A.; Ambrose, C.; Lobb, R.; Rennert, P.; Abken, H. A CD19-Anti-ErbB2 scFv Engager Protein Enables CD19-Specific CAR T Cells to Eradicate ErbB2(+) Solid Cancer. Cells 2023, 12, 248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, L.; Wu, L.; Lobb, R.R.; Rennert, P.D.; Ambrose, C. CAR-T Engager proteins optimize anti-CD19 CAR-T cell therapies for lymphoma. Oncoimmunology 2022, 11, 2111904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klesmith, J.R.; Su, L.; Wu, L.; Schrack, I.A.; Dufort, F.J.; Birt, A.; Ambrose, C.; Hackel, B.J.; Lobb, R.R.; Rennert, P.D. Retargeting CD19 Chimeric Antigen Receptor T Cells via Engineered CD19-Fusion Proteins. Mol. Pharm. 2019, 16, 3544–3558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rennert, P.D.; Dufort, F.J.; Su, L.; Sanford, T.; Birt, A.; Wu, L.; Lobb, R.R.; Ambrose, C. Anti-CD19 CAR T Cells That Secrete a Biparatopic Anti-CLEC12A Bridging Protein Have Potent Activity Against Highly Aggressive Acute Myeloid Leukemia In Vitro and In Vivo. Mol. Cancer Ther. 2021, 20, 2071–2081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kourtesakis, A.; Bailey, E.; Chow, H.N.H.; Rohdjess, H.; Mussnig, N.; Agardy, D.A.; Hoffmann, D.C.F.; Chih, Y.C.; Will, R.; Kaulen, L.; et al. Utilization of universal-targeting mSA2 CAR-T cells for the treatment of glioblastoma. Oncoimmunology 2025, 14, 2518631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Atar, D.; Ruoff, L.; Mast, A.S.; Krost, S.; Moustafa-Oglou, M.; Scheuermann, S.; Kristmann, B.; Feige, M.; Canak, A.; Wolsing, K.; et al. Rational combinatorial targeting by adapter CAR-T-cells (AdCAR-T) prevents antigen escape in acute myeloid leukemia. Leukemia 2024, 38, 2183–2195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grote, S.; Mittelstaet, J.; Baden, C.; Chan, K.C.; Seitz, C.; Schlegel, P.; Kaiser, A.; Handgretinger, R.; Schleicher, S. Adapter chimeric antigen receptor (AdCAR)-engineered NK-92 cells: An off-the-shelf cellular therapeutic for universal tumor targeting. Oncoimmunology 2020, 9, 1825177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grote, S.; Traub, F.; Mittelstaet, J.; Seitz, C.; Kaiser, A.; Handgretinger, R.; Schleicher, S. Adapter Chimeric Antigen Receptor (AdCAR)-Engineered NK-92 Cells for the Multiplex Targeting of Bone Metastases. Cancers 2021, 13, 1124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tanaka, H.; Fujiwara, H.; Ochi, F.; Tanimoto, K.; Casey, N.; Okamoto, S.; Mineno, J.; Kuzushima, K.; Shiku, H.; Sugiyama, T.; et al. Development of Engineered T Cells Expressing a Chimeric CD16-CD3zeta Receptor to Improve the Clinical Efficacy of Mogamulizumab Therapy Against Adult T-Cell Leukemia. Clin. Cancer Res. 2016, 22, 4405–4416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruhns, P.; Iannascoli, B.; England, P.; Mancardi, D.A.; Fernandez, N.; Jorieux, S.; Daeron, M. Specificity and affinity of human Fcgamma receptors and their polymorphic variants for human IgG subclasses. Blood 2009, 113, 3716–3725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munoz, J.; Flinn, I.W.; Cohen, J.B.; Sachs, J.; Exter, B.; Ranger, A.; Harris, P.; Payumo, F.; Nath, R.; Hamadani, M.; et al. Results from a Phase 1 Study of ACTR707 in Combination with Rituximab in Patients with Relapsed or Refractory CD20(+) B Cell Lymphoma. Transpl. Transplant. Cell Ther. 2024, 30, 241.e1–241.e8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akard, L.P.; Payumo, F.; Harris, P.; Ranger, A.; Sachs, J.; Stiff, P.J.; Isufi, I.; McKinney, M.S.; Jaglowski, S.; Munoz, J. A Phase 1 Study of ACTR087 in Combination with Rituximab, in Subjects with Relapsed or Refractory CD20-Positive B-Cell Lymphoma. Blood 2019, 134 (Suppl. 1), 244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flinn, I.W.; Westin, J.R.; Cohen, J.B.; Akard, L.P.; Jaglowski, S.; Sachs, J.; Ranger, A.; Harris, P.; Payumo, F.; Bachanova, V. Preliminary Clinical Results from a Phase 1 Study of ACTR707 in Combination with Rituximab in Subjects with Relapsed or Refractory CD20+ non-Hodgkin Lymphoma. Blood 2019, 134 (Suppl. 1), 1587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hickman, T.L.; Choi, E.; Whiteman, K.R.; Muralidharan, S.; Pai, T.; Johnson, T.; Parikh, A.; Friedman, T.; Gilbert, M.; Shen, B.; et al. BOXR1030, an anti-GPC3 CAR with exogenous GOT2 expression, shows enhanced T cell metabolism and improved anti-cell line derived tumor xenograft activity. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0266980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schlothauer, T.; Herter, S.; Koller, C.F.; Grau-Richards, S.; Steinhart, V.; Spick, C.; Kubbies, M.; Klein, C.; Umana, P.; Mossner, E. Novel human IgG1 and IgG4 Fc-engineered antibodies with completely abolished immune effector functions. Protein Eng. Des. Sel. 2016, 29, 457–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, S.; Tian, W.; Li, M.; Wei, H.; Sun, L.; Xie, Q.; Lin, E.; Xu, D.; Tian, J.; Chen, J.; et al. 1054P A phase Ia study to evaluate the safety, tolerability, pharmacokinetics and preliminary efficacy of a modular CLDN18.2-targeting PG CAR-T therapy (IBI345) in patients with CLDN18.2+ solid tumors. Ann. Oncol. 2023, 34, 2193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stock, S.; Strzalkowski, T.; Gottschlich, A.; Rohrbacher, L.; Fertig, L.; Menkhoff, V.D.; Surowka, M.; Bruenker, P.; Darowski, D.; Endres, S.; et al. Adaptor Anti-P329G CAR T Cells for Modular Targeting of AML. Blood 2023, 142 (Suppl. 1), 4805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, C.; Li, C.; Wang, D.I.; Jin, S.; Yao, W.; Shang, J.; Yan, S.; Xiao, M.; Chen, L.; Li, M.; et al. P1406: Safety and Efficacy of Ibi346, a First-in-Class Bcma-Targeting Modular Car-T Cell Therapy, for Patients with Relapsed/Refractory Multiple Myeloma (Rrmm): Preliminary Results from Two Phase I Studies. HemaSphere 2023, 7, e534971f. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derrick, J.P.; Wigley, D.B. Crystal structure of a streptococcal protein G domain bound to an Fab fragment. Nature 1992, 359, 752–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zakeri, B.; Fierer, J.O.; Celik, E.; Chittock, E.C.; Schwarz-Linek, U.; Moy, V.T.; Howarth, M. Peptide tag forming a rapid covalent bond to a protein, through engineering a bacterial adhesin. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2012, 109, E690–E697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sek, K.; Li, J.; Tong, J.; Lim, R.; Yatomi-Clarke, S.; Darcy, P. Immunotherapy: Omni-Car, A Universal Car T Cell Therapy Utilizing Covalent Spytag/Spycatcher Binding to Target Multiple Antigens in Different Tumors. Cytotherapy 2023, 25, S250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keppler, A.; Gendreizig, S.; Gronemeyer, T.; Pick, H.; Vogel, H.; Johnsson, K. A general method for the covalent labeling of fusion proteins with small molecules in vivo. Nat. Biotechnol. 2003, 21, 86–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langan, R.A.; Boyken, S.E.; Ng, A.H.; Samson, J.A.; Dods, G.; Westbrook, A.M.; Nguyen, T.H.; Lajoie, M.J.; Chen, Z.; Berger, S.; et al. De novo design of bioactive protein switches. Nature 2019, 572, 205–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buonato, J.M.; Edwards, J.P.; Zaritskaya, L.; Witter, A.R.; Gupta, A.; LaFleur, D.W.; Tice, D.A.; Richman, L.K.; Hilbert, D.M. Preclinical Efficacy of BCMA-Directed CAR T Cells Incorporating a Novel D Domain Antigen Recognition Domain. Mol. Cancer Ther. 2022, 21, 1171–1183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qin, H.; Edwards, J.P.; Zaritskaya, L.; Gupta, A.; Mu, C.J.; Fry, T.J.; Hilbert, D.M.; LaFleur, D.W. Chimeric Antigen Receptors Incorporating D Domains Targeting CD123 Direct Potent Mono- and Bi-specific Antitumor Activity of T Cells. Mol. Ther. 2019, 27, 1262–1274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walsh, S.T.; Cheng, H.; Bryson, J.W.; Roder, H.; DeGrado, W.F. Solution structure and dynamics of a de novo designed three-helix bundle protein. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1999, 96, 5486–5491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, J.P.; Buonato, J.; LaFleur, D.; Swers, J.; Mu, J.; Zaritskaya, L.; Ng, S.; Gupta, A.; Wang, H.; McCullough, S.; et al. Abstract 1549: ACLX-001, a novel BCMA-targeted CAR-T cell therapy that can be activated, silenced, and reprogrammed in vivo with soluble protein adapters in a dose dependent manner. Cancer Res. 2021, 81 (Suppl. 13), 1549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wermke, M.; Kraus, S.; Ehninger, A.; Bargou, R.C.; Goebeler, M.E.; Middeke, J.M.; Kreissig, C.; von Bonin, M.; Koedam, J.; Pehl, M.; et al. Proof of concept for a rapidly switchable universal CAR-T platform with UniCAR-T-CD123 in relapsed/refractory AML. Blood 2021, 137, 3145–3148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Vedvyas, Y.; Alcaina, Y.; Trumper, S.J.; Babu, D.S.; Min, I.M.; Tremblay, J.M.; Shoemaker, C.B.; Jin, M.M. Affinity-tuned mesothelin CAR T cells demonstrate enhanced targeting specificity and reduced off-tumor toxicity. JCI Insight 2024, 9, e186268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barden, M.; Elsenbroich, P.R.; Haas, V.; Ertelt, M.; Pervan, P.; Velas, L.; Gergely, B.; Szoor, A.; Harrer, D.C.; Bezler, V.; et al. Integrating binding affinity and tonic signaling enables a rational CAR design for augmented T cell function. J. Immunother. Cancer 2024, 12, e010208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghorashian, S.; Kramer, A.M.; Onuoha, S.; Wright, G.; Bartram, J.; Richardson, R.; Albon, S.J.; Casanovas-Company, J.; Castro, F.; Popova, B.; et al. Enhanced CAR T cell expansion and prolonged persistence in pediatric patients with ALL treated with a low-affinity CD19 CAR. Nat. Med. 2019, 25, 1408–1414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, A.H.; Haso, W.M.; Shern, J.F.; Wanhainen, K.M.; Murgai, M.; Ingaramo, M.; Smith, J.P.; Walker, A.J.; Kohler, M.E.; Venkateshwara, V.R.; et al. 4-1BB costimulation ameliorates T cell exhaustion induced by tonic signaling of chimeric antigen receptors. Nat. Med. 2015, 21, 581–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lynn, R.C.; Weber, E.W.; Sotillo, E.; Gennert, D.; Xu, P.; Good, Z.; Anbunathan, H.; Lattin, J.; Jones, R.; Tieu, V.; et al. c-Jun overexpression in CAR T cells induces exhaustion resistance. Nature 2019, 576, 293–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Qiu, S.; Li, W.; Wang, K.; Zhang, Y.; Yang, H.; Liu, B.; Li, G.; Li, L.; Chen, M.; et al. Tuning charge density of chimeric antigen receptor optimizes tonic signaling and CAR-T cell fitness. Cell Res. 2023, 33, 341–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landoni, E.; Fuca, G.; Wang, J.; Chirasani, V.R.; Yao, Z.; Dukhovlinova, E.; Ferrone, S.; Savoldo, B.; Hong, L.K.; Shou, P.; et al. Modifications to the Framework Regions Eliminate Chimeric Antigen Receptor Tonic Signaling. Cancer Immunol. Res. 2021, 9, 441–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frigault, M.J.; Lee, J.; Basil, M.C.; Carpenito, C.; Motohashi, S.; Scholler, J.; Kawalekar, O.U.; Guedan, S.; McGettigan, S.E.; Posey, A.D., Jr.; et al. Identification of chimeric antigen receptors that mediate constitutive or inducible proliferation of T cells. Cancer Immunol. Res. 2015, 3, 356–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myers, D.R.; Zikherman, J.; Roose, J.P. Tonic Signals: Why Do Lymphocytes Bother? Trends Immunol. 2017, 38, 844–857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schenk, S.; Schoenhals, G.J.; de Souza, G.; Mann, M. A high confidence, manually validated human blood plasma protein reference set. BMC Med. Genom. 2008, 1, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schneider, E.L.; Hearn, B.R.; Pfaff, S.J.; Fontaine, S.D.; Reid, R.; Ashley, G.W.; Grabulovski, S.; Strassberger, V.; Vogt, L.; Jung, T.; et al. Approach for Half-Life Extension of Small Antibody Fragments That Does Not Affect Tissue Uptake. Bioconjug. Chem. 2016, 27, 2534–2539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Howard, E.L.; Goens, M.M.; Susta, L.; Patel, A.; Wootton, S.K. Anti-Drug Antibody Response to Therapeutic Antibodies and Potential Mitigation Strategies. Biomedicines 2025, 13, 299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brudno, J.N.; Kochenderfer, J.N. Toxicities of chimeric antigen receptor T cells: Recognition and management. Blood 2016, 127, 3321–3330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brudno, J.N.; Kochenderfer, J.N. Recent advances in CAR T-cell toxicity: Mechanisms, manifestations and management. Blood Rev. 2019, 34, 45–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cappell, K.M.; Kochenderfer, J.N. Long-term outcomes following CAR T cell therapy: What we know so far. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 2023, 20, 359–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marvin-Peek, J.; Savani, B.N.; Olalekan, O.O.; Dholaria, B. Challenges and Advances in Chimeric Antigen Receptor Therapy for Acute Myeloid Leukemia. Cancers 2022, 14, 497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zugasti, I.; Espinosa-Aroca, L.; Fidyt, K.; Mulens-Arias, V.; Diaz-Beya, M.; Juan, M.; Urbano-Ispizua, A.; Esteve, J.; Velasco-Hernandez, T.; Menendez, P. CAR-T cell therapy for cancer: Current challenges and future directions. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2025, 10, 210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haubner, S.; Perna, F.; Kohnke, T.; Schmidt, C.; Berman, S.; Augsberger, C.; Schnorfeil, F.M.; Krupka, C.; Lichtenegger, F.S.; Liu, X.; et al. Coexpression profile of leukemic stem cell markers for combinatorial targeted therapy in AML. Leukemia 2019, 33, 64–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, A.L.; Gilman, A.L.; Ozkaynak, M.F.; London, W.B.; Kreissman, S.G.; Chen, H.X.; Smith, M.; Anderson, B.; Villablanca, J.G.; Matthay, K.K.; et al. Anti-GD2 antibody with GM-CSF, interleukin-2, and isotretinoin for neuroblastoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 2010, 363, 1324–1334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morgan, R.A.; Yang, J.C.; Kitano, M.; Dudley, M.E.; Laurencot, C.M.; Rosenberg, S.A. Case report of a serious adverse event following the administration of T cells transduced with a chimeric antigen receptor recognizing ERBB2. Mol. Ther. 2010, 18, 843–851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, K.H.; Chen, L. Fine tuning the immune response through B7-H3 and B7-H4. Immunol. Rev. 2009, 229, 145–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loo, D.; Alderson, R.F.; Chen, F.Z.; Huang, L.; Zhang, W.; Gorlatov, S.; Burke, S.; Ciccarone, V.; Li, H.; Yang, Y.; et al. Development of an Fc-enhanced anti-B7-H3 monoclonal antibody with potent antitumor activity. Clin. Cancer Res. 2012, 18, 3834–3845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, C.; Tang, K.J.; Cho, B.C.; Liu, B.; Paz-Ares, L.; Cheng, S.; Kitazono, S.; Thiagarajan, M.; Goldman, J.W.; Sabari, J.K.; et al. Amivantamab plus Chemotherapy in NSCLC with EGFR Exon 20 Insertions. N. Engl. J. Med. 2023, 389, 2039–2051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boice, M.; Salloum, D.; Mourcin, F.; Sanghvi, V.; Amin, R.; Oricchio, E.; Jiang, M.; Mottok, A.; Denis-Lagache, N.; Ciriello, G.; et al. Loss of the HVEM Tumor Suppressor in Lymphoma and Restoration by Modified CAR-T Cells. Cell 2016, 167, 405–418 e413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, B.D.; Yu, X.; Castano, A.P.; Bouffard, A.A.; Schmidts, A.; Larson, R.C.; Bailey, S.R.; Boroughs, A.C.; Frigault, M.J.; Leick, M.B.; et al. CAR-T cells secreting BiTEs circumvent antigen escape without detectable toxicity. Nat. Biotechnol. 2019, 37, 1049–1058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Coupling Technology | Platform | CAR Target (Clone) | Adaptor Format | Adaptor Tag | Tag Valency | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Peptide Tags | Uni-CAR | La/SS-B (5B9) | scFv, nanobody | La/SS-B-derived peptide | Monovalent | [15,33] |

| PNE-CAR | PNE GCN4 (52SR4) | Fab | GCN4-derived peptide | Monovalent | [16] | |

| AdCAR v2 | P2m2 (MB196-C1) | Fab | FGFR2-derived peptide | Monovalent | [34] | |

| cp-Fab/CAR | PNE GCN4 (52SR4) | Fab–folate conjugate | GCN4-derived peptide | Monovalent | [35] | |

| SAR T | EGFR/Cripto-1 scFv | Bi-specific mAb | EGFR/Cripto-1 Fab or scFv | Bivalent | [36] | |

| RevCAR | 5B9/7B6 scFv | scFv | 5B9/7B6 scFv | Monovalent | [37] | |

| Fabrack-CAR | Meditope mAb or Fab | Fab or mAb | Meditope binding site | Mono- or bivalent | [25] | |

| Conduit CAR | Unknown (3-23/B3) CD19 (FMC63) | Bi-specific mAb | G4S-targeting Fab or scFv | Bivalent | [38] | |

| TRUE CAR T | EGFRvIII | PEG–lipid conjugate | EGFRvIII peptide | Monovalent | [39] | |

| Chemical Tags | FITC CAR | FITC (4m5.3) | Fab | FITC | Mono- or bivalent | [17] |

| FITC CAR | FITC (4m5.3) | Small molecule | FITC | Monovalent | [18] | |

| FITC CAR | FITC (E2) | Small molecule | FITC | Monovalent | [40] | |

| Amph-FITC CAR | FITC (4m5.3) | PEG–lipid conjugate | FITC | Monovalent | [41] | |

| AdCAR | Biotin-LLE (mBio3) | mAb | Biotin-LLE | Multivalent | [19] | |

| mSA2 CAR | Biotin | mAb | Biotin | Multivalent | [20] | |

| BBIR CAR | Biotin | scFv, mAb | Biotin | Multivalent | [21] | |

| BsAb-IR CAR | FRα mAb | Two conjugated mAbs | FRα mAb | Bivalent | [42] | |

| Antibody domain recognition | CD16 CAR | Fc part of mAb | mAb | Fc part of mAb | Bivalent | [43] |

| ACTR (CD16 CAR) | Fc part of mAb | mAb | Fc part of mAb | Bivalent | [22] | |

| CD16 CAR | Fc part of mAb | mAb | Fc part of mAb | Bivalent | [44] | |

| CD16 CAR | Fc part of mAb | mAb | Fc part of mAb | Bivalent | [23] | |

| P329G CAR | P329G mutation | Fc silenced mAb | P329G mutation of Fc part | Monovalent | [24] | |

| GA1 CAR | Fab CL domain (GA1) | Fab | CL domain of Fab | Monovalent | [26] | |

| CD19 CAR engager | CD19 (FMC63) | scFv | CD19-ECD | Monovalent | [45] | |

| Covalent bond | OmniCAR | SpyTag | DARPin or mAb | SpyTag | Mono- or bivalent | [29] |

| MU-CAR | GvOptiTag | scFv | GvOptiTag | Monovalent | [28] | |

| BsCAR | Barnase | DARPin | Barnase | Monovalent | [27] | |

| SNAP-CAR | Benzylguanine | mAb | Benzylguanine | Multivalent | [46] | |

| Engineered protein pairs | Supra-CAR | Cognate leucine zipper | scFv | Cognate leucine zipper | Monovalent | [30] |

| Co-LOCKR | Bim “latch” | DARPin | “Cage” and “key” protein | Monovalent | [31] | |

| ConvertibleCAR | ULBP2-S3 | mAb | U2S3 peptide | Bivalent | [32] | |

| ARC-SparX | AFP domain III | D-domain | AFP-derived peptide | Mono- or bivalent | [47] |

| Platforms | Coupling Technology | Target Antigen and Disease Entity | Clinical Trial | Status | Results | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Uni-CAR | scFv binds La/SS-B-derived peptide | CD123-positive AML | NCT04230265 | Phase I, active, not recruiting | No DLT, clinical response in all patients, ORR 53% in first 19 patients | [89] |

| PSMA-positive prostate cancer | NCT04633148 | Phase I, terminated | N/A | |||

| RevCAR | La/SS-B peptide binds scFv | CD123-positive AML | NCT05949125 | Phase I, recruiting | N/A | |

| PNE-CAR | scFv binds GCN4-derived PNE | CD19-positive B-cell malignancy | NCT04450069 | Phase I, completed | Safe and well tolerated, clinical response, ORR 78% and CR 67% | [55,56] |

| Her2-positive breast cancer | NCT06878248 | Phase I, recruiting | N/A | |||

| CD19, autoimmune diseases | NCT06913608 | Phase I, not yet recruiting | N/A | |||

| ACTR | CD16 ECD binding IgG Fc domain | Her2-positive advanced malignancies | NCT03680560 | Phase I, terminated | N/A | |

| CD20-positive B-cell lymphoma | NCT02776813 | Phase I, completed | CRS and neurotoxicity reportedORR 50% | [73] | ||

| CD20-positive B-cell lymphoma | NCT03189836 | Phase I, terminated | well tolerated, ORR 56% | [72] | ||

| P329G CAR | scFv binds P329G mutated Fc domain | CLDN18.2-positive solid tumours | NCT05199519 | Phase I, completed | Manageable safety profile and preliminary efficacy | [77] |

| BCMA-positive multiple myeloma | NCT05270928 | Phase I, completed | No DLT, PR 50% | [79] | ||

| BCMA-positive multiple myeloma | NCT05266768 | Phase I, unknown | No DLT, PR 40% | [79] | ||

| CD19 CAR engager | scFv binds CD19 ECD | B-cell malignancies post CD19 CAR T-cell therapy | NCT06045910 | Phase I/II, recruiting | N/A | |

| convertibleCAR | iNKG2D ECD binds ULBP2-S3 | CD20-positive B-cell lymphoma | NCT06248086 | Phase I, terminated | N/A | |

| ARC-SparX | scFv binds AFP-derived peptide | CD123-positive AML or MDS | NCT05457010 | Phase I, recruiting | N/A |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Joechner, A.H.; Mach, M.; Li, Z. The Current Landscape of Modular CAR T Cells. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 11898. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262411898

Joechner AH, Mach M, Li Z. The Current Landscape of Modular CAR T Cells. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2025; 26(24):11898. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262411898

Chicago/Turabian StyleJoechner, Alexander Haide, Melanie Mach, and Ziduo Li. 2025. "The Current Landscape of Modular CAR T Cells" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 26, no. 24: 11898. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262411898

APA StyleJoechner, A. H., Mach, M., & Li, Z. (2025). The Current Landscape of Modular CAR T Cells. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 26(24), 11898. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262411898