Bioinformatic Approach to Identify Potential TGFB2-Dependent and Independent Prognostic Biomarkers for Ovarian Cancers Treated with Taxol

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. TGFB2-Dependent Prognostic Marker Genes

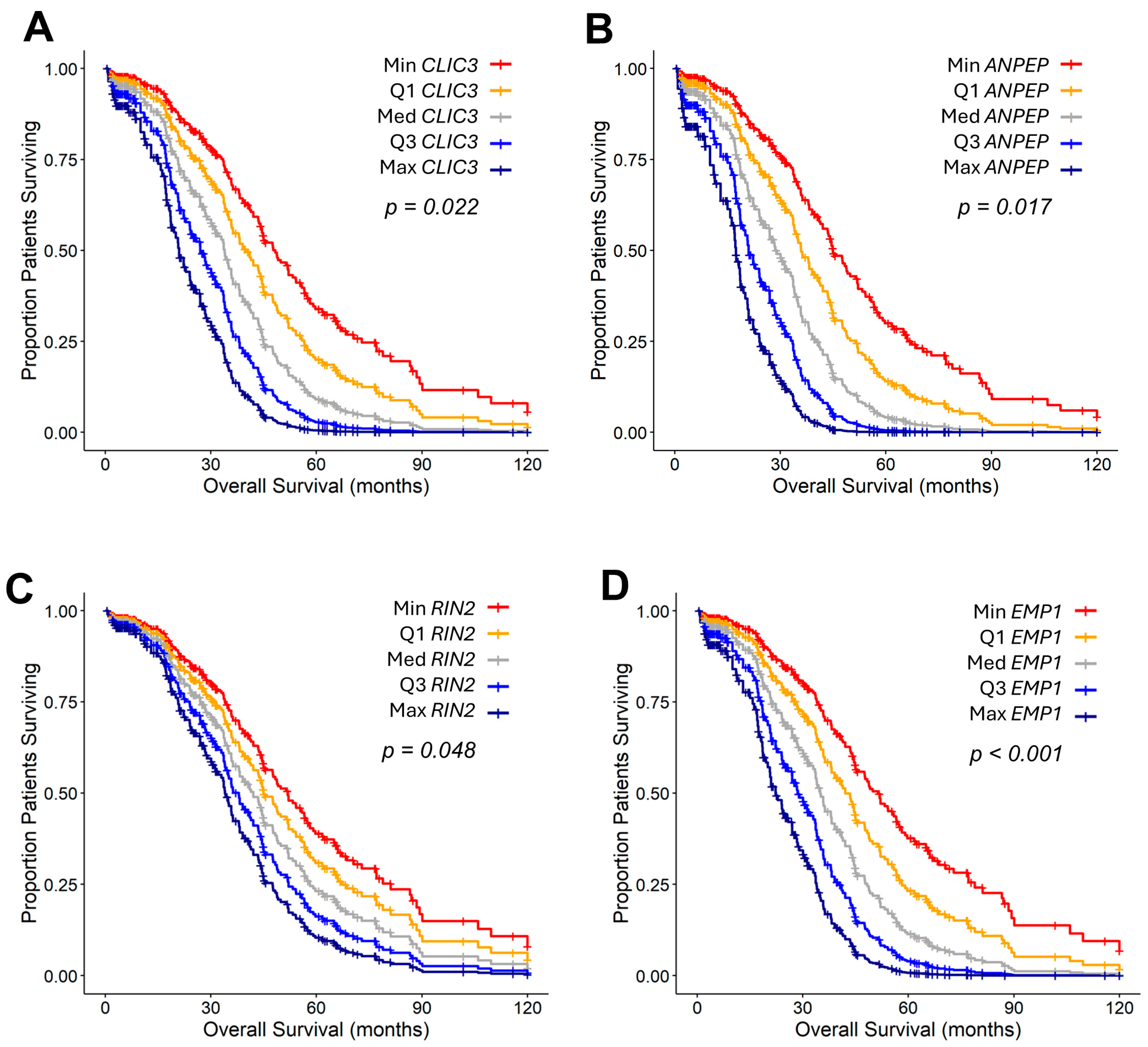

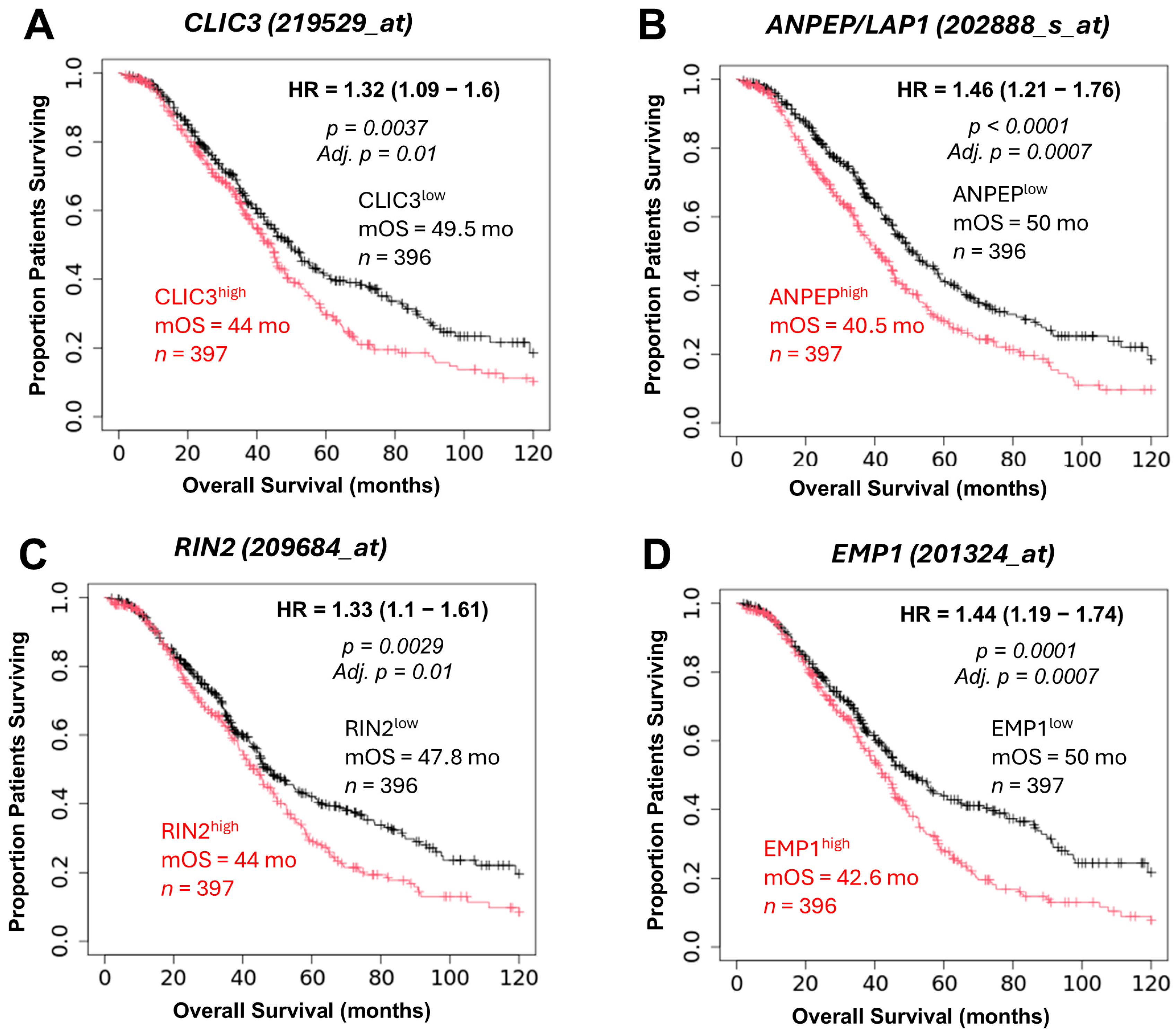

2.2. TGFB2-Independent Marker Genes That Predict Worse Prognosis in Taxol-Treated Patients

3. Discussion

3.1. TGFB2-Dependent Prognostic Markers

3.2. TGFB2-Independent Prognostic Markers

3.3. Taxol-Treatment Prognostic Biomarkers

3.4. Future Clinical Design of Taxol-Prognostic Biomarkers in Combination with Lipid-Based Nanoparticles of Taxol

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. AI-Augmented Summaries of Pubmed Abstracts

4.2. Using the Multivariate Cox Proportional Hazards Model to Identify TGFB2-Dependent and TGFB2-Independent Biomarkers Impacting Overall Survival (OS) Outcomes for Serous Ovarian Cancer Patients

4.3. Differential Expression of mRNA Comparing Serous Ovarian Tumors Versus Normal Tissue Samples

4.4. OS Analysis Using Kaplan–Meier Comparisons Verified for Taxol-Treated Patients in an Independent KMplotter Dataset for TGFB2-Independent Biomarkers Discovered in the TCGA Dataset

4.5. Identifying Prognostically Relevant Proteins Associated with TGFB2-Dependent and TGFB2-Independent Marker Genes Using the STRING Interaction Algorithm

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kim, J.; Park, E.; Kim, O.; Schilder, J.; Coffey, D.; Cho, C.-H.; Bast, R. Cell Origins of High-Grade Serous Ovarian Cancer. Cancers 2018, 10, 433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelliher, L.; Lengyel, E. Understanding Long-Term Survival of Patients with Ovarian Cancer—The Tumor Microenvironment Comes to the Forefront. Cancer Res. 2023, 83, 1383–1385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adzibolosu, N.; Alvero, A.B.; Ali-Fehmi, R.; Gogoi, R.; Corey, L.; Tedja, R.; Chehade, H.; Gogoi, V.; Morris, R.; Anderson, M.; et al. Immunological Modifications Following Chemotherapy Are Associated with Delayed Recurrence of Ovarian Cancer. Front. Immunol. 2023, 14, 1204148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barretina-Ginesta, M.-P.; Carbó Bagué, A.; Bujons, E.; Fortian, A.; Fina, C.; Pardo, M.; Melendez-Muñoz, C.; Cardenas, L.; Taltavull, A.; Sabaté, J.; et al. Clinical Features of Long-Term Survivors with Advanced High-Grade Serous Ovarian Cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 2023, 41, e17575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dao, F.; Schlappe, B.A.; Tseng, J.; Lester, J.; Nick, A.M.; Lutgendorf, S.K.; McMeekin, S.; Coleman, R.L.; Moore, K.N.; Karlan, B.Y.; et al. Characteristics of 10-Year Survivors of High-Grade Serous Ovarian Carcinoma. Gynecol. Oncol. 2016, 141, 260–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matulonis, U.A.; Sood, A.K.; Fallowfield, L.; Howitt, B.E.; Sehouli, J.; Karlan, B.Y. Ovarian Cancer. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers 2016, 2, 16061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Zyl, B.; Tang, D.; Bowden, N.A. Biomarkers of Platinum Resistance in Ovarian Cancer: What Can We Use to Improve Treatment. Endocr. Relat. Cancer 2018, 25, R303–R318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmood, R.D.; Morgan, R.D.; Edmondson, R.J.; Clamp, A.R.; Jayson, G.C. First-Line Management of Advanced High-Grade Serous Ovarian Cancer. Curr. Oncol. Rep. 2020, 22, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luyckx, M.; Squifflet, J.-L.; Bruger, A.M.; Baurain, J.-F. Recurrent High Grade Serous Ovarian Cancer Management. In Ovarian Cancer; Exon Publications: Brisbane, Australia, 2022; pp. 87–103. [Google Scholar]

- Fostira, F.; Papadimitriou, M.; Papadimitriou, C. Current Practices on Genetic Testing in Ovarian Cancer. Ann. Transl. Med. 2020, 8, 1703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilczyński, J.; Paradowska, E.; Wilczyński, M. Personalization of Therapy in High-Grade Serous Tubo-Ovarian Cancer—The Possibility or the Necessity? J. Pers. Med. 2023, 14, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, R.; Hu, R.; Li, W.; Lv, X.; Zhao, H.; Li, F. Unveiling Drug Resistance Pathways in High-Grade Serous Ovarian Cancer (HGSOC): Recent Advances and Future Perspectives. Front. Immunol. 2025, 16, 1556377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, M.C.; Lavi, E.S.; Altwerger, G.; Lin, Z.P.; Ratner, E.S. Predictive Modeling of Gene Mutations for the Survival Outcomes of Epithelial Ovarian Cancer Patients. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0305273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Jong, D.; Otify, M.; Chen, I.; Jackson, D.; Jayasinghe, K.; Nugent, D.; Thangavelu, A.; Theophilou, G.; Laios, A. Survival and Chemosensitivity in Advanced High Grade Serous Epithelial Ovarian Cancer Patients with and Without a BRCA Germline Mutation: More Evidence for Shifting the Paradigm Towards Complete Surgical Cytoreduction. Medicina 2022, 58, 1611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, W.; Cheng, L.; Li, B. Development and Evaluation of a Novel TPGS-Mediated Paclitaxel-Loaded PLGA-MPEG Nanoparticle for the Treatment of Ovarian Cancer. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 2015, 63, 68–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Ye, X.H.; Zhao, X.L.; Liu, J.L.; Zhang, C.Y. Development of a Five-Gene Signature as a Novel Prognostic Marker in Ovarian Cancer. Neoplasma 2019, 66, 343–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshihara, K.; Tsunoda, T.; Shigemizu, D.; Fujiwara, H.; Hatae, M.; Fujiwara, H.; Masuzaki, H.; Katabuchi, H.; Kawakami, Y.; Okamoto, A.; et al. High-Risk Ovarian Cancer Based on 126-Gene Expression Signature Is Uniquely Characterized by Downregulation of Antigen Presentation Pathway. Clin. Cancer Res. 2012, 18, 1374–1385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalsan, M.; Al-Alloosh, F.; Al-Khafaji, A. Enhancing Personalized Chemotherapy for Ovarian Cancer: Integrating Gene Expression Data with Machine Learning. Asian Pac. J. Cancer Prev. 2025, 26, 959–967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, G.; Chen, L.; Ren, H.; Liu, F.; Dong, C.; Wu, A.; Liu, Z.; Zheng, Y.; Cheng, X.; Liu, L. Seven Genes Based Novel Signature Predicts Clinical Outcome and Platinum Sensitivity of High Grade IIIc Serous Ovarian Carcinoma. Int. J. Biol. Sci. 2018, 14, 2012–2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gordinier, M.E.; Zhang, H.Z.; Patenia, R.; Levy, L.B.; Atkinson, E.N.; Nash, M.A.; Katz, R.L.; Platsoucas, C.D.; Freedman, R.S. Quantitative Analysis of Transforming Growth Factor Beta 1 and 2 in Ovarian Carcinoma. Clin. Cancer Res. 1999, 5, 2498–2505. [Google Scholar]

- Roane, B.M.; Arend, R.C.; Birrer, M.J. Review: Targeting the Transforming Growth Factor-Beta Pathway in Ovarian Cancer. Cancers 2019, 11, 668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Do, T.-V.; Kubba, L.A.; Du, H.; Sturgis, C.D.; Woodruff, T.K. Transforming Growth Factor-Β1, Transforming Growth Factor-Β2, and Transforming Growth Factor-Β3 Enhance Ovarian Cancer Metastatic Potential by Inducing a Smad3-Dependent Epithelial-to-Mesenchymal Transition. Mol. Cancer Res. 2008, 6, 695–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez, G.C.; Haisley, C.; Hurteau, J.; Moser, T.L.; Whitaker, R.; Bast, R.C.; Stack, M.S. Regulation of Invasion of Epithelial Ovarian Cancer by Transforming Growth Factor-β. Gynecol. Oncol. 2001, 80, 245–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamamura, S.; Matsumura, N.; Mandai, M.; Huang, Z.; Oura, T.; Baba, T.; Hamanishi, J.; Yamaguchi, K.; Kang, H.S.; Okamoto, T.; et al. The Activated Transforming Growth Factor-Beta Signaling Pathway in Peritoneal Metastases Is a Potential Therapeutic Target in Ovarian Cancer. Int. J. Cancer 2012, 130, 20–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qazi, S.; Potts, M.; Myers, S.; Richardson, S.; Trieu, V. Positive Prognostic Overall Survival Impacts of Methylated TGFB2 and MGMT in Adult Glioblastoma Patients. Cancers 2025, 17, 1122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trieu, V.; Potts, M.; Myers, S.; Richardson, S.; Qazi, S. TGFB2 Gene Methylation in Tumors with Low CD8+ T-Cell Infiltration Drives Positive Prognostic Overall Survival Responses in Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 5567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saif, M.W.; Chang, W.-H.; Myers, S.; Potts, M.; Qazi, S.; Trieu, V. TGFB2 Expression and Methylation Predict Overall Survival in Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma Patients. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 6357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qazi, S.; Talebi, Z.; Trieu, V. Transforming Growth Factor Beta 2 (TGFB2) and Interferon Gamma Receptor 2 (IFNGR2) MRNA Levels in the Brainstem Tumor Microenvironment (TME) Significantly Impact Overall Survival in Pediatric DMG Patients. Biomedicines 2024, 12, 191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qazi, S.; Trieu, V. TGFB2 MRNA Levels Prognostically Interact with Interferon-Alpha Receptor Activation of IRF9 and IFI27, and an Immune Checkpoint LGALS9 to Impact Overall Survival in Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 11221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trieu, V.; Maida, A.E.; Qazi, S. Transforming Growth Factor Beta 2 (TGFB2) MRNA Levels, in Conjunction with Interferon-Gamma Receptor Activation of Interferon Regulatory Factor 5 (IRF5) and Expression of CD276/B7-H3, Are Therapeutically Targetable Negative Prognostic Markers in Low-Grade Gliomas. Cancers 2024, 16, 1202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Győrffy, B. Integrated Analysis of Public Datasets for the Discovery and Validation of Survival-Associated Genes in Solid Tumors. Innovation 2024, 5, 100625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Győrffy, B. Discovery and Ranking of the Most Robust Prognostic Biomarkers in Serous Ovarian Cancer. Geroscience 2023, 45, 1889–1898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, P.; Peng, T.; Cao, C.; Lin, S.; Wu, P.; Huang, X.; Wei, J.; Xi, L.; Yang, Q.; Wu, P. Association of CLDN6 and CLDN10 With Immune Microenvironment in Ovarian Cancer: A Study of the Claudin Family. Front. Genet. 2021, 12, 595436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamikawa, T.; Kimura, N.; Ishii, S.; Muraoka, M.; Kodama, T.; Taniguchi, K.; Yoshimoto, M.; Miura-Okuda, M.; Uchikawa, R.; Kato, C.; et al. SAIL66, a next Generation CLDN6-Targeting T-Cell Engager, Demonstrates Potent Antitumor Efficacy Through Dual Binding to CD3/CD137. J. Immunother. Cancer 2024, 12, e009563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, P.; Liu, W.; Xu, Q.; Wang, C. Clinical Significance and Biological Role of Wnt10a in Ovarian Cancer. Oncol. Lett. 2017, 14, 6611–6617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, B.; Wan, T.; Zhou, Y.; Huang, S.; Yuan, L.; Jiang, Y.; Zheng, X.; Liu, P.; Xiang, H.; Ju, M.; et al. The MYBL2–CCL2 Axis Promotes Tumor Progression and Resistance to Anti-PD-1 Therapy in Ovarian Cancer by Inducing Immunosuppressive Macrophages. Cancer Cell Int. 2023, 23, 248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, Q.; Liu, T.; Wang, M.; Yang, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Liu, Z.; Yang, B. KRT7 Promotes Epithelial-mesenchymal Transition in Ovarian Cancer via the TGF-β/Smad2/3 Signaling Pathway. Oncol. Rep. 2020, 45, 481–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamir, A.; Gangadharan, A.; Balwani, S.; Tanaka, T.; Patel, U.; Hassan, A.; Benke, S.; Agas, A.; D’Agostino, J.; Shin, D.; et al. The Serine Protease Prostasin (PRSS8) Is a Potential Biomarker for Early Detection of Ovarian Cancer. J. Ovarian Res. 2016, 9, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, S.; Holmes, A.; Lomo, L.; Steinkamp, M.P.; Kang, H.; Muller, C.Y.; Wilson, B.S. High Incidence of ErbB3, ErbB4, and MET Expression in Ovarian Cancer. Int. J. Gynecol. Pathol. 2014, 33, 402–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Lu, A.; Hu, Z.; Li, J.; Lu, J. ERBB3 Targeting: A Promising Approach to Overcoming Cancer Therapeutic Resistance. Cancer Lett. 2024, 599, 217146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, D.C.P.; Pan, C.Q.; Er, S.Y.; Thivakar, T.; Rachel, T.Z.Y.; Seah, S.H.; Chua, P.J.; Jiang, T.; Chew, T.W.; Chaudhuri, P.K.; et al. The Scaffold RhoGAP Protein ARHGAP8/BPGAP1 Synchronizes Rac and Rho Signaling to Facilitate Cell Migration. Mol. Biol. Cell 2023, 34, ar13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Chen, S.; Luo, M.; Yan, H.; Pang, L.; Zhu, C.; Tan, W.; Zhao, Q.; Lai, J.; Li, H. The Role of the CDCA Gene Family in Ovarian Cancer. Ann. Transl. Med. 2020, 8, 190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, X.; Wu, H.; Zhu, W. SPOCK2 Promotes the Invasion and Migration of Ovarian Cancer Cells Through FAK Signaling Pathway. J. Gynecol. Oncol. 2025, 36, e98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q.; Li, S.; Fu, F.; Huang, Q.; Zhang, R. MAP7 Drives EMT and Cisplatin Resistance in Ovarian Cancer via Wnt/β-Catenin Signaling. Heliyon 2024, 10, e30409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, M.; Zaman, K.; Das, S.; Goyary, D.; Pathak, M.P.; Chattopadhyay, P. Transient Receptor Potential Vanilloid (TRPV4) Channel Inhibition: A Novel Promising Approach for the Treatment of Lung Diseases. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2023, 163, 114861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, D.; Guo, R.; Dai, R.; Knoedler, S.; Tao, J.; Machens, H.-G.; Rinkevich, Y. The Multifaceted Functions of TRPV4 and Calcium Oscillations in Tissue Repair. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 1179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Xu, C.; Ma, C.; Zhang, Q.; Bu, S.; Zhang, D.-L.; Yu, L.; Wang, H. TRPs in Ovarian Serous Cystadenocarcinoma: The Expression Patterns, Prognostic Roles, and Potential Therapeutic Targets. Front. Mol. Biosci. 2022, 9, 915409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Feng, X.; Zheng, L.; Chai, Z.; Yu, J.; You, X.; Li, X.; Cheng, X. TRPV4 Is a Prognostic Biomarker That Correlates with the Immunosuppressive Microenvironment and Chemoresistance of Anti-Cancer Drugs. Front. Mol. Biosci. 2021, 8, 690500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, L.; Li, X.; Wu, A.-J.; Xiu, J.; Gan, Y.-Z.; Yang, X.; Ai, Z.-H. TRPV4 Enhances the Synthesis of Fatty Acids to Drive the Progression of Ovarian Cancer Through the Calcium-MTORC1/SREBP1 Signaling Pathway. iScience 2023, 26, 108226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Marco, M.C.; Martiín-Belmonte, F.; Kremer, L.; Albar, J.P.; Correas, I.; Vaerman, J.P.; Marazuela, M.; Byrne, J.A.; Alonso, M.A. MAL2, a Novel Raft Protein of the MAL Family, Is an Essential Component of the Machinery for Transcytosis in Hepatoma HepG2 Cells. J. Cell Biol. 2002, 159, 37–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrne, J.; Murali, R.; Maleki, S.; Hardy, J.; Gloss, B.; Scurry, J.; Fanayan, S.; Emmanuel, C.; Hacker, N.; Sutherland, R.; et al. 30. MAL2 and Tumour Protein D52 (TPD52) Overexpression in Ovarian Carcinoma, Association with Histological Subtype and Clinical Outcome. Pathology 2011, 43, S98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrne, J.A.; Maleki, S.; Hardy, J.R.; Gloss, B.S.; Murali, R.; Scurry, J.P.; Fanayan, S.; Emmanuel, C.; Hacker, N.F.; Sutherland, R.L.; et al. MAL2 and Tumor Protein D52 (TPD52) Are Frequently Overexpressed in Ovarian Carcinoma, but Differentially Associated with Histological Subtype and Patient Outcome. BMC Cancer 2010, 10, 497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, J.; Jiang, X.; Lan, H.; Zhang, X.; Ding, T.; Yang, F.; Zeng, D.; Yong, J.; Niu, B.; Xiao, S. Multi-Omics Analysis of the Therapeutic Value of MAL2 Based on Data Mining in Human Cancers. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2022, 9, 736649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.; Wu, C.; Fu, Z.; Liu, S. ICAM1 Promotes Bone Metastasis via Integrin-mediated TGF-β/EMT Signaling in Triple-negative Breast Cancer. Cancer Sci. 2022, 113, 3751–3765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shirakihara, T.; Horiguchi, K.; Miyazawa, K.; Ehata, S.; Shibata, T.; Morita, I.; Miyazono, K.; Saitoh, M. TGF-β Regulates Isoform Switching of FGF Receptors and Epithelial-Mesenchymal Transition. EMBO J. 2011, 30, 783–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lainé, A.; Labiad, O.; Hernandez-Vargas, H.; This, S.; Sanlaville, A.; Léon, S.; Dalle, S.; Sheppard, D.; Travis, M.A.; Paidassi, H.; et al. Regulatory T Cells Promote Cancer Immune-Escape Through Integrin Avβ8-Mediated TGF-β Activation. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 6228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.E.; Xiang, B.; Guix, M.; Olivares, M.G.; Parker, J.; Chung, C.H.; Pandiella, A.; Arteaga, C.L. Transforming Growth Factor β Engages TACE and ErbB3 To Activate Phosphatidylinositol-3 Kinase/Akt in ErbB2-Overexpressing Breast Cancer and Desensitizes Cells to Trastuzumab. Mol. Cell Biol. 2008, 28, 5605–5620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heraud-Farlow, J.E.; Kiebler, M.A. The Multifunctional Staufen Proteins: Conserved Roles from Neurogenesis to Synaptic Plasticity. Trends Neurosci. 2014, 37, 470–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goetze, B.; Tuebing, F.; Xie, Y.; Dorostkar, M.M.; Thomas, S.; Pehl, U.; Boehm, S.; Macchi, P.; Kiebler, M.A. The Brain-Specific Double-Stranded RNA-Binding Protein Staufen2 Is Required for Dendritic Spine Morphogenesis. J. Cell Biol. 2006, 172, 221–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kusek, G.; Campbell, M.; Doyle, F.; Tenenbaum, S.A.; Kiebler, M.; Temple, S. Asymmetric Segregation of the Double-Stranded RNA Binding Protein Staufen2 during Mammalian Neural Stem Cell Divisions Promotes Lineage Progression. Cell Stem Cell 2012, 11, 505–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Kuang, W.; Ding, J.; Li, J.; Ji, M.; Chen, W.; Shen, H.; Shi, Z.; Wang, D.; Wang, L.; et al. Systematic Identification of the RNA-Binding Protein STAU2 as a Key Regulator of Pancreatic Adenocarcinoma. Cancers 2022, 14, 3629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, M.; Zhan, J.; Zhang, H. HOX Family Transcription Factors: Related Signaling Pathways and Post-Translational Modifications in Cancer. Cell Signal. 2020, 66, 109469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, R.; Plowright, L.; Harrington, K.J.; Michael, A.; Pandha, H.S. Targeting HOX and PBX Transcription Factors in Ovarian Cancer. BMC Cancer 2010, 10, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, Z.L.; Michael, A.; Butler-Manuel, S.; Pandha, H.S.; Morgan, R.G. HOX Genes in Ovarian Cancer. J. Ovarian Res. 2011, 4, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, Z.; Moller-Levet, C.; McGrath, S.; Butler-Manuel, S.; Kavitha Madhuri, T.; Kierzek, A.M.; Pandha, H.; Morgan, R.; Michael, A. The Prognostic Significance of Specific HOX Gene Expression Patterns in Ovarian Cancer. Int. J. Cancer 2016, 139, 1608–1617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Idaikkadar, P.; Morgan, R.; Michael, A. HOX Genes in High Grade Ovarian Cancer. Cancers 2019, 11, 1107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, J.; Li, Y.; Liu, Y.; Chen, Y.; He, Z.; Peng, S.; Yin, Y. The Involvement of Homeobox-C 4 in Predicting Prognosis and Unraveling Immune Landscape across Multiple Cancers via Integrated Analysis. Front. Genet. 2022, 13, 1021473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conway, G.D.; Buzza, M.S.; Martin, E.W.; Duru, N.; Johnson, T.A.; Peroutka, R.J.; Pawar, N.R.; Antalis, T.M. PRSS21/Testisin Inhibits Ovarian Tumor Metastasis and Antagonizes Proangiogenic Angiopoietins ANG2 and ANGPTL4. J. Mol. Med. 2019, 97, 691–709, Erratum in J. Mol. Med. 2019, 97, 1375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Wu, Y.; Chen, S.; Guo, Q.; Shao, Y.; Liu, C.; Lin, K.; Wang, S.; Zhu, J.; Chen, X.; et al. PARP1-Stabilised FOXQ1 Promotes Ovarian Cancer Progression by Activating the LAMB3/WNT/β-Catenin Signalling Pathway. Oncogene 2024, 43, 866–883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Wang, Y.; Chen, T.; Zhang, Y.; Xu, R.; Wang, W.; Cheng, M.; Chen, Q. Aberrant Activation of Hedgehog Signalling Promotes Cell Migration and Invasion Via Matrix Metalloproteinase-7 in Ovarian Cancer Cells. J. Cancer 2019, 10, 990–1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, X.; Li, G.; Liu, S.; Wang, H.; Zhang, Z.; Chen, B. Bioinformatics Analysis of KIF1A Expression and Gene Regulation Network in Ovarian Carcinoma. Int. J. Gen. Med. 2021, 14, 3707–3717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, L.; Li, T.; Liu, Y. High SLC4A11 Expression Is an Independent Predictor for Poor Overall Survival in Grade 3/4 Serous Ovarian Cancer. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0187385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Sun, R.; Hong, X.; Chen, C.; Ding, Y. KLHL14: A Novel Prognostic Biomarker and Therapeutic Target for Ovarian Cancer. J. Oncol. 2022, 2022, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, W.; Zhou, C.; Wang, J.; Zhao, J.; Liu, F.; Wang, G.; Xu, C.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, W.; Cai, S.; et al. A Prognostic Signature Based on Adenosine Metabolism Related Genes for Ovarian Cancer. Front. Oncol. 2022, 12, 1003512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hiramatsu, K.; Serada, S.; Enomoto, T.; Takahashi, Y.; Nakagawa, S.; Nojima, S.; Morimoto, A.; Matsuzaki, S.; Yokoyama, T.; Takahashi, T.; et al. LSR Antibody Therapy Inhibits Ovarian Epithelial Tumor Growth by Inhibiting Lipid Uptake. Cancer Res. 2018, 78, 516–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lou, J.; Wei, L.; Wang, H. SCNN1A Overexpression Correlates with Poor Prognosis and Immune Infiltrates in Ovarian Cancer. Int. J. Gen. Med. 2022, 15, 1743–1763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sung, H.Y.; Yang, S.-D.; Park, A.K.; Ju, W.; Ahn, J.-H. Aberrant Hypomethylation of Solute Carrier Family 6 Member 12 Promoter Induces Metastasis of Ovarian Cancer. Yonsei Med. J. 2017, 58, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quaresima, B.; Scicchitano, S.; Faniello, M.; Mesuraca, M. Role of Solute Carrier Transporters in Ovarian Cancer (Review). Int. J. Mol. Med. 2024, 55, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Chen, Z.; Zhang, L. Identification of Estrogen Response-Associated STRA6+ Granulosa Cells within High-Grade Serous Ovarian Carcinoma by Single-Cell Sequencing. Heliyon 2024, 10, e27790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graumann, J.; Finkernagel, F.; Reinartz, S.; Stief, T.; Brödje, D.; Renz, H.; Jansen, J.M.; Wagner, U.; Worzfeld, T.; Pogge von Strandmann, E.; et al. Multi-Platform Affinity Proteomics Identify Proteins Linked to Metastasis and Immune Suppression in Ovarian Cancer Plasma. Front. Oncol. 2019, 9, 01150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, K.; Huang, Y.; Zheng, Y.; Hao, W.; Shi, K. ZSWIM4 Inhibition Improves Chemosensitivity in Epithelial Ovarian Cancer Cells by Suppressing Intracellular Glycine Biosynthesis. J. Transl. Med. 2024, 22, 192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, G.; Sun, Y.; Wei, R.; Xi, L. Small Leucine-Rich Proteoglycan PODNL1 Identified as a Potential Tumor Matrix-Mediated Biomarker for Prognosis and Immunotherapy in a Pan-Cancer Setting. Curr. Issues Mol. Biol. 2023, 45, 6116–6139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, T.; Bi, F.; Liu, Z.; Yang, Q. TMEM119 Facilitates Ovarian Cancer Cell Proliferation, Invasion, and Migration via the PDGFRB/PI3K/AKT Signaling Pathway. J. Transl. Med. 2021, 19, 111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, S.; Albitar, L.; LeBaron, R.; Welch, W.R.; Samimi, G.; Birrer, M.J.; Berkowitz, R.S.; Mok, S.C. Up-Regulation of Stromal Versican Expression in Advanced Stage Serous Ovarian Cancer. Gynecol. Oncol. 2010, 119, 114–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Chen, S.; Xu, F.; Chen, X. Knockdown of TRIM47 Overcomes Paclitaxel Resistance in Ovarian Cancer by Suppressing the TGF-β Pathway via PPM1A. Am. J. Reprod. Immunol. 2025, 93, e70102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, W.; Yuan, J.; Li, X.; Gao, X.; Wang, F.; Liu, H.; Shi, J.; Xu, G. Cyclin Dependent Kinase 14 as a Paclitaxel-Resistant Marker Regulated by the TGF-β Signaling Pathway in Human Ovarian Cancer. J. Cancer 2023, 14, 2538–2551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostrowska-Leśko, M.; Mądry, R.; Bobiński, M. Optimizing Bevacizumab Dosing in First-Line Ovarian Cancer Treatment: The PGOG-Ov1 Trial. Trials 2025, 26, 325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Kim, S.I.; Suh, D.H.; Kim, K.; No, J.H.; Kim, Y.B. Comparison of Second-Line Chemotherapies for First-Relapsed High-Grade Serous Ovarian Cancer: A Retrospective Study. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 6905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dozynkiewicz, M.A.; Jamieson, N.B.; MacPherson, I.; Grindlay, J.; van den Berghe, P.V.E.; von Thun, A.; Morton, J.P.; Gourley, C.; Timpson, P.; Nixon, C.; et al. Rab25 and CLIC3 Collaborate to Promote Integrin Recycling from Late Endosomes/Lysosomes and Drive Cancer Progression. Dev. Cell 2012, 22, 131–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macpherson, I.R.; Rainero, E.; Mitchell, L.E.; van den Berghe, P.V.; Speirs, C.; Dozynkiewicz, M.A.; Chaudhary, S.; Kalna, G.; Edwards, J.; Timpson, P.; et al. CLIC3 Controls Recycling of Late Endosomal MT1-MMP and Dictates Invasion and Metastasis in Breast Cancer. J. Cell Sci. 2014, 127, 3893–3901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norman, J.; Zanivan, S. Chloride Intracellular Channel 3: A Secreted pro-Invasive Oxidoreductase. Cell Cycle 2017, 16, 1993–1994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Fernaud, J.R.; Ruengeler, E.; Casazza, A.; Neilson, L.; Pulleine, E.; MacPherson, I.; Blyth, K.; Yin, H.; Mazzone, M.; Norman, J.; et al. Abstract PR01: CLIC3 Is Secreted by CAFs and Enhances Angiogenesis and Tumor Cell Invasion by Cooperating with TGM2. Mol. Cancer Ther. 2015, 14, PR01. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernandez-Fernaud, J.R.; Ruengeler, E.; Casazza, A.; Neilson, L.J.; Pulleine, E.; Santi, A.; Ismail, S.; Lilla, S.; Dhayade, S.; MacPherson, I.R.; et al. Secreted CLIC3 Drives Cancer Progression through Its Glutathione-Dependent Oxidoreductase Activity. Nat. Commun. 2017, 8, 14206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Li, J.; Li, Y.; Yi, J.; Zhao, X.; Yue, W. Single-Cell Transcriptomics Identify a Chemotherapy-Resistance Related Cluster Overexpressed CLIC3 in Ovarian Cancer. Discov. Oncol. 2025, 16, 1099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.; Zhang, S.; Wen, X.; Cao, H.; Gao, Y. Prognostic Value of CLIC3 MRNA Overexpression in Bladder Cancer. PeerJ 2020, 8, e8348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawai, S.; Fujii, T.; Shimizu, T.; Sukegawa, K.; Hashimoto, I.; Okumura, T.; Nagata, T.; Sakai, H.; Fujii, T. Pathophysiological Properties of CLIC3 Chloride Channel in Human Gastric Cancer Cells. J. Physiol. Sci. 2020, 70, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shuai, Y.; Zhang, H.; Liu, C.; Wang, J.; Jiang, Y.; Sun, J.; Gao, X.; Bo, X.; Xiao, X.; Liao, X.; et al. CLIC3 Interacts with NAT10 to Inhibit N4-Acetylcytidine Modification of P21 MRNA and Promote Bladder Cancer Progression. Cell Death Dis. 2024, 15, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wojtera, B.P.; Ostrowska, K.; Szewczyk, M.; Masternak, M.; Golusiński, W. Chloride Intracellular Channels in Oncology as Potential Novel Biomarkers and Personalized Therapy Targets: A Systematic Review. Rep. Pract. Oncol. Radiother. 2024, 29, 258–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mellor, P.; Kendall, S.; Smith, S.; Olsen, J.; Sahile, H.; Page, B.; Saxena, A.; Anderson, D. Abstract 6919: Targeting CLIC3 as a Novel Strategy to Inhibit Metastasis in Breast Cancer. Cancer Res. 2025, 85, 6919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byun, J.M.; Jeong, D.H.; Choi, I.H.; Lee, D.S.; Kang, M.S.; Jung, K.O.; Jeon, Y.K.; Kim, Y.N.; Jung, E.J.; Lee, K.B.; et al. The Significance of VSIG4 Expression in Ovarian Cancer. Int. J. Gynecol. Cancer 2017, 27, 872–878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guzman-Rojas, L.; Rangel, R.; Salameh, A.; Edwards, J.K.; Dondossola, E.; Kim, Y.-G.; Saghatelian, A.; Giordano, R.J.; Kolonin, M.G.; Staquicini, F.I.; et al. Cooperative Effects of Aminopeptidase N (CD13) Expressed by Nonmalignant and Cancer Cells within the Tumor Microenvironment. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2012, 109, 1637–1642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dondossola, E.; Rangel, R.; Guzman-Rojas, L.; Barbu, E.M.; Hosoya, H.; John, L.S.S.; Molldrem, J.J.; Corti, A.; Sidman, R.L.; Arap, W.; et al. CD13-Positive Bone Marrow-Derived Myeloid Cells Promote Angiogenesis, Tumor Growth, and Metastasis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2013, 110, 20717–20722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lendeckel, U.; Karimi, F.; Al Abdulla, R.; Wolke, C. The Role of the Ectopeptidase APN/CD13 in Cancer. Biomedicines 2023, 11, 724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haraguchi, N.; Ishii, H.; Mimori, K.; Tanaka, F.; Ohkuma, M.; Kim, H.M.; Akita, H.; Takiuchi, D.; Hatano, H.; Nagano, H.; et al. CD13 Is a Therapeutic Target in Human Liver Cancer Stem Cells. J. Clin. Investig. 2010, 120, 3326–3339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elkenawi, A.; Awasthi, S.; Serna, A.; Dhillon, J.; Yamoah, K. ANPEP: A Potential Regulator of Tumor Cell—Immune Metabolic Interactions in Prostate Cancer of Men of African Descent. JCO Glob. Oncol. 2022, 8, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sørensen, K.D.; Abildgaard, M.O.; Haldrup, C.; Ulhøi, B.P.; Kristensen, H.; Strand, S.; Parker, C.; Høyer, S.; Borre, M.; Ørntoft, T.F. Prognostic Significance of Aberrantly Silenced ANPEP Expression in Prostate Cancer. Br. J. Cancer 2013, 108, 420–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pang, L.; Zhang, N.; Xia, Y.; Wang, D.; Wang, G.; Meng, X. Serum APN/CD13 as a Novel Diagnostic and Prognostic Biomarker of Pancreatic Cancer. Oncotarget 2016, 7, 77854–77864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Wang, J.; Zhang, H.; Zhao, D.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, S. Expression and Clinical Significance of Aminopeptidase N/CD13 in Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer. J. Cancer Res. Ther. 2015, 11, 223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Surowiak, P.; Drąg, M.; Materna, V.; Suchocki, S.; Grzywa, R.; Spaczyński, M.; Dietel, M.; Oleksyszyn, J.; Zabel, M.; Lage, H. Expression of Aminopeptidase N/CD13 in Human Ovarian Cancers. Int. J. Gynecol. Cancer 2006, 16, 1783–1788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terauchi, M.; Kajiyama, H.; Shibata, K.; Ino, K.; Nawa, A.; Mizutani, S.; Kikkawa, F. Inhibition of APN/CD13 Leads to Suppressed Progressive Potential in Ovarian Carcinoma Cells. BMC Cancer 2007, 7, 140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Hensbergen, Y.; Broxterman, H.J.; Rana, S.; van Diest, P.J.; Duyndam, M.C.A.; Hoekman, K.; Pinedo, H.M.; Boven, E. Reduced Growth, Increased Vascular Area, and Reduced Response to Cisplatin in CD13-Overexpressing Human Ovarian Cancer Xenografts. Clin. Cancer Res. 2004, 10, 1180–1191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ween, M.P.; Oehler, M.K.; Ricciardelli, C. Transforming Growth Factor-Beta-Induced Protein (TGFBI)/(Βig-H3): A Matrix Protein with Dual Functions in Ovarian Cancer. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2012, 13, 10461–10477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandri, C.; Caccavari, F.; Valdembri, D.; Camillo, C.; Veltel, S.; Santambrogio, M.; Lanzetti, L.; Bussolino, F.; Ivaska, J.; Serini, G. The R-Ras/RIN2/Rab5 Complex Controls Endothelial Cell Adhesion and Morphogenesis via Active Integrin Endocytosis and Rac Signaling. Cell Res. 2012, 22, 1479–1501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kempers, L.; Wakayama, Y.; van der Bijl, I.; Furumaya, C.; De Cuyper, I.M.; Jongejan, A.; Kat, M.; van Stalborch, A.-M.D.; van Boxtel, A.L.; Hubert, M.; et al. The Endosomal RIN2/Rab5C Machinery Prevents VEGFR2 Degradation to Control Gene Expression and Tip Cell Identity during Angiogenesis. Angiogenesis 2021, 24, 695–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, L.; Dong, C.; Jia, W.; Ma, B. NAA20 Recruits Rin2 and Promotes Triple-Negative Breast Cancer Progression by Regulating Rab5A-Mediated Activation of EGFR Signaling. Cell Signal. 2023, 112, 110922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, N.; Zhu, H.; Huang, W.; Wen, X.; Xie, X.; Jiang, X.; Peng, C.; Han, B.; He, G. Unraveling the Structures, Functions and Mechanisms of Epithelial Membrane Protein Family in Human Cancers. Exp. Hematol. Oncol. 2022, 11, 69, Erratum in Exp. Hematol. Oncol. 2022, 11, 90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmat Amin, M.K.B.; Shimizu, A.; Ogita, H. The Pivotal Roles of the Epithelial Membrane Protein Family in Cancer Invasiveness and Metastasis. Cancers 2019, 11, 1620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, G.-G. Epithelial Membrane Protein 1 Negatively Regulates Cell Growth and Metastasis in Colorectal Carcinoma. World J. Gastroenterol. 2014, 20, 4001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Cao, W.; Xu, Q.; Chen, W. The Expression of EMP1 Is Downregulated in Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma and Possibly Associated with Tumour Metastasis. J. Clin. Pathol. 2011, 64, 25–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Yang, J.; Li, X.; Mao, L.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, Y.; Bao, Y. EMP1 Correlated with Cancer Progression and Immune Characteristics in Pan-Cancer and Ovarian Cancer. Mol. Genet. Genom. 2024, 299, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, B.; Zhang, T.; Ye, X.; Yang, H. High Expression of EMP1 Predicts a Poor Prognosis and Correlates with Immune Infiltrates in Bladder Urothelial Carcinoma. Oncol. Lett. 2020, 20, 2840–2854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Ding, Y.; Nie, Y.; Yang, M. EMP1 Promotes the Proliferation and Invasion of Ovarian Cancer Cells Through Activating the MAPK Pathway. Onco Targets Ther. 2020, 13, 2047–2055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Y.; Wu, F.; Chen, Z.; Hou, Y. Epithelial Membrane Protein 1 in Human Cancer: A Potential Diagnostic Biomarker and Therapeutic Target. Biomark. Med. 2024, 18, 995–1005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, Q.; Yi, C.; Lu, J.; Wang, X.; Chen, K.; Hong, L. Identification of EMP1 as a Critical Gene for Cisplatin Resistance in Ovarian Cancer by Using Integrated Bioinformatics Analysis. Cancer Med. 2023, 12, 9024–9040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhai, J.; Luwor, R.B.; Ahmed, N.; Escalona, R.; Tan, F.H.; Fong, C.; Ratcliffe, J.; Scoble, J.A.; Drummond, C.J.; Tran, N. Paclitaxel-Loaded Self-Assembled Lipid Nanoparticles as Targeted Drug Delivery Systems for the Treatment of Aggressive Ovarian Cancer. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2018, 10, 25174–25185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalifa, A.M.; Elsheikh, M.A.; Khalifa, A.M.; Elnaggar, Y.S.R. Current Strategies for Different Paclitaxel-Loaded Nano-Delivery Systems towards Therapeutic Applications for Ovarian Carcinoma: A Review Article. J. Control. Release 2019, 311–312, 125–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldman, M.J.; Craft, B.; Hastie, M.; Repečka, K.; McDade, F.; Kamath, A.; Banerjee, A.; Luo, Y.; Rogers, D.; Brooks, A.N.; et al. Visualizing and Interpreting Cancer Genomics Data via the Xena Platform. Nat. Biotechnol. 2020, 38, 675–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vivian, J.; Rao, A.A.; Nothaft, F.A.; Ketchum, C.; Armstrong, J.; Novak, A.; Pfeil, J.; Narkizian, J.; Deran, A.D.; Musselman-Brown, A.; et al. Toil Enables Reproducible, Open Source, Big Biomedical Data Analyses. Nat. Biotechnol. 2017, 35, 314–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denkert, C.; Budczies, J.; Darb-Esfahani, S.; Györffy, B.; Sehouli, J.; Könsgen, D.; Zeillinger, R.; Weichert, W.; Noske, A.; Buckendahl, A.; et al. A Prognostic Gene Expression Index in Ovarian Cancer—Validation across Different Independent Data Sets. J. Pathol. 2009, 218, 273–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szklarczyk, D.; Kirsch, R.; Koutrouli, M.; Nastou, K.; Mehryary, F.; Hachilif, R.; Gable, A.L.; Fang, T.; Doncheva, N.T.; Pyysalo, S.; et al. The STRING Database in 2023: Protein–Protein Association Networks and Functional Enrichment Analyses for Any Sequenced Genome of Interest. Nucleic Acids Res. 2023, 51, D638–D646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Gene 2 | Gene 2 mRNA (Z Score) | TGFB2 by Gene 2 Interaction | Fold Increase (95% CI) | Contrast | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR (95% CI) | p-Value | HR (95% CI) | p-Value | Adj. p-Value | ||

| HOXC4 | 1.36 (1.03–1.78) | 0.028 | 1.74 (1.19–2.56) | 0.004 | 1.31 (1.13–1.52) | 0.047 |

| STAU2 | 0.99 (0.87–1.13) | 0.925 | 1.34 (1.07–1.67) | 0.011 | 1.66 (1.51–1.82) | 0.00018 |

| TRPV4 | 1.26 (1.03–1.55) | 0.027 | 1.53 (1.1–2.14) | 0.012 | 9.96 (9.08–10.98) | <0.0000001 |

| MAL2 | 1 (0.82–1.23) | 0.974 | 0.79 (0.62–1) | 0.046 | 705 (614.8–806.8) | <0.0000001 |

| EMP1 | 1.32 (1.12–1.56) | <0.001 | 1.26 (0.93–1.7) | 0.136 | 2.39 (2.09–2.74) | <0.0000001 |

| ANPEP | 1.45 (1.07–1.98) | 0.017 | 1.79 (0.96–3.32) | 0.066 | 10.16 (8.55–12.17) | <0.0000001 |

| CLIC3 | 1.22 (1.03–1.45) | 0.022 | 0.95 (0.74–1.23) | 0.715 | 19.25 (16.28–22.55) | <0.0000001 |

| RIN2 | 1.17 (1–1.36) | 0.048 | 1.02 (0.84–1.24) | 0.869 | 1.71 (1.53–1.90) | 0.000024 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Qazi, S.; Richardson, S.; Potts, M.; Myers, S.; Saund, S.; De, T.; Trieu, V. Bioinformatic Approach to Identify Potential TGFB2-Dependent and Independent Prognostic Biomarkers for Ovarian Cancers Treated with Taxol. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 11900. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262411900

Qazi S, Richardson S, Potts M, Myers S, Saund S, De T, Trieu V. Bioinformatic Approach to Identify Potential TGFB2-Dependent and Independent Prognostic Biomarkers for Ovarian Cancers Treated with Taxol. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2025; 26(24):11900. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262411900

Chicago/Turabian StyleQazi, Sanjive, Stephen Richardson, Mike Potts, Scott Myers, Saran Saund, Tapas De, and Vuong Trieu. 2025. "Bioinformatic Approach to Identify Potential TGFB2-Dependent and Independent Prognostic Biomarkers for Ovarian Cancers Treated with Taxol" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 26, no. 24: 11900. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262411900

APA StyleQazi, S., Richardson, S., Potts, M., Myers, S., Saund, S., De, T., & Trieu, V. (2025). Bioinformatic Approach to Identify Potential TGFB2-Dependent and Independent Prognostic Biomarkers for Ovarian Cancers Treated with Taxol. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 26(24), 11900. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262411900