Autophagy-Related Proteins Influence Mouse Epididymal Sperm Motility

Abstract

1. Introduction

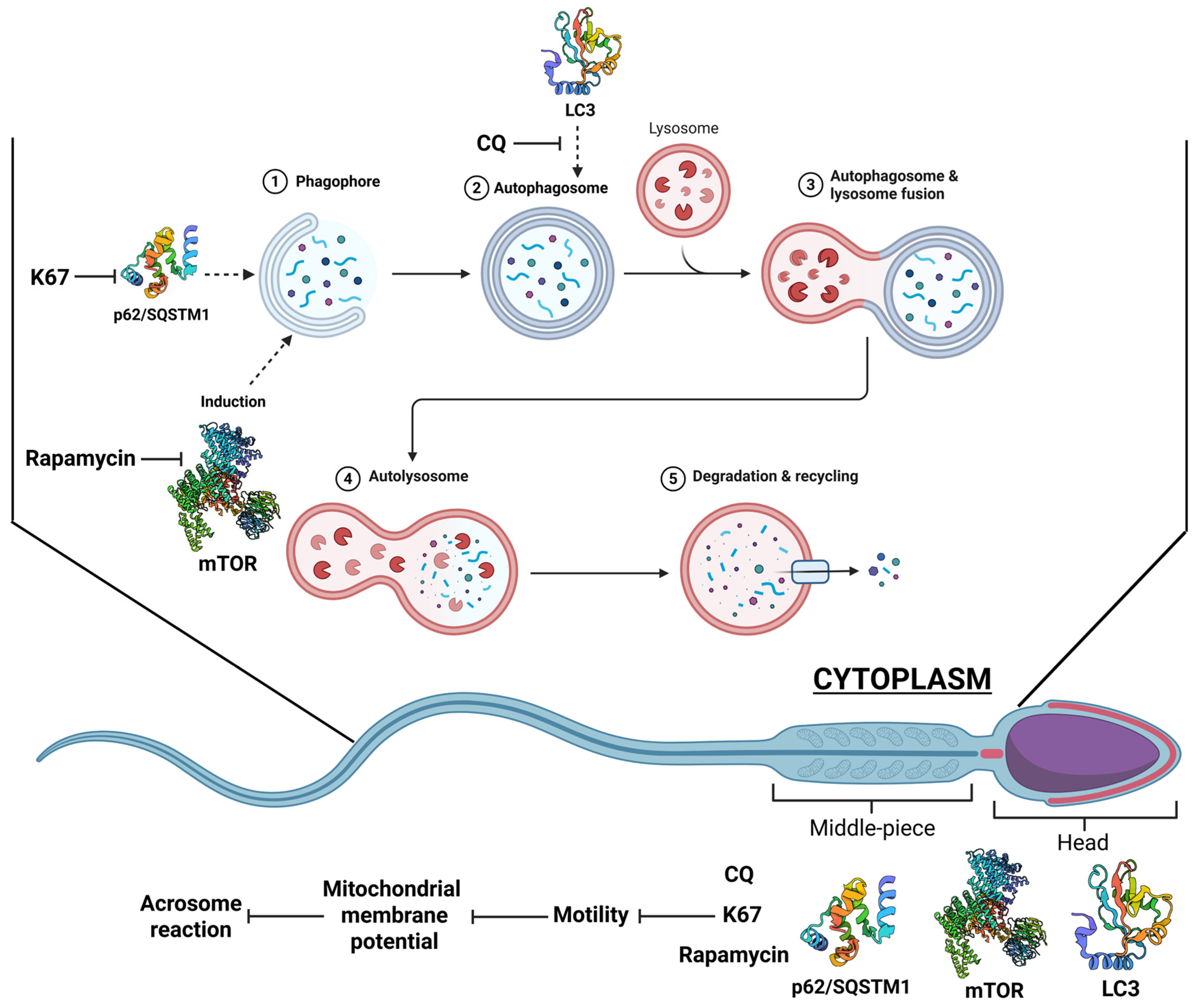

2. Results

2.1. LC3 Is Expressed in Mouse Epididymal Sperm

2.2. p62/SQSTM1 Decreases Under Capacitation Conditions in Mouse Epididymal Sperm

2.3. mTOR Is Expressed in Mouse Epididymal Sperm

2.4. Effects of Exposure to Different CQ, K67, and Rapamycin Concentrations on Mouse Sperm Viability

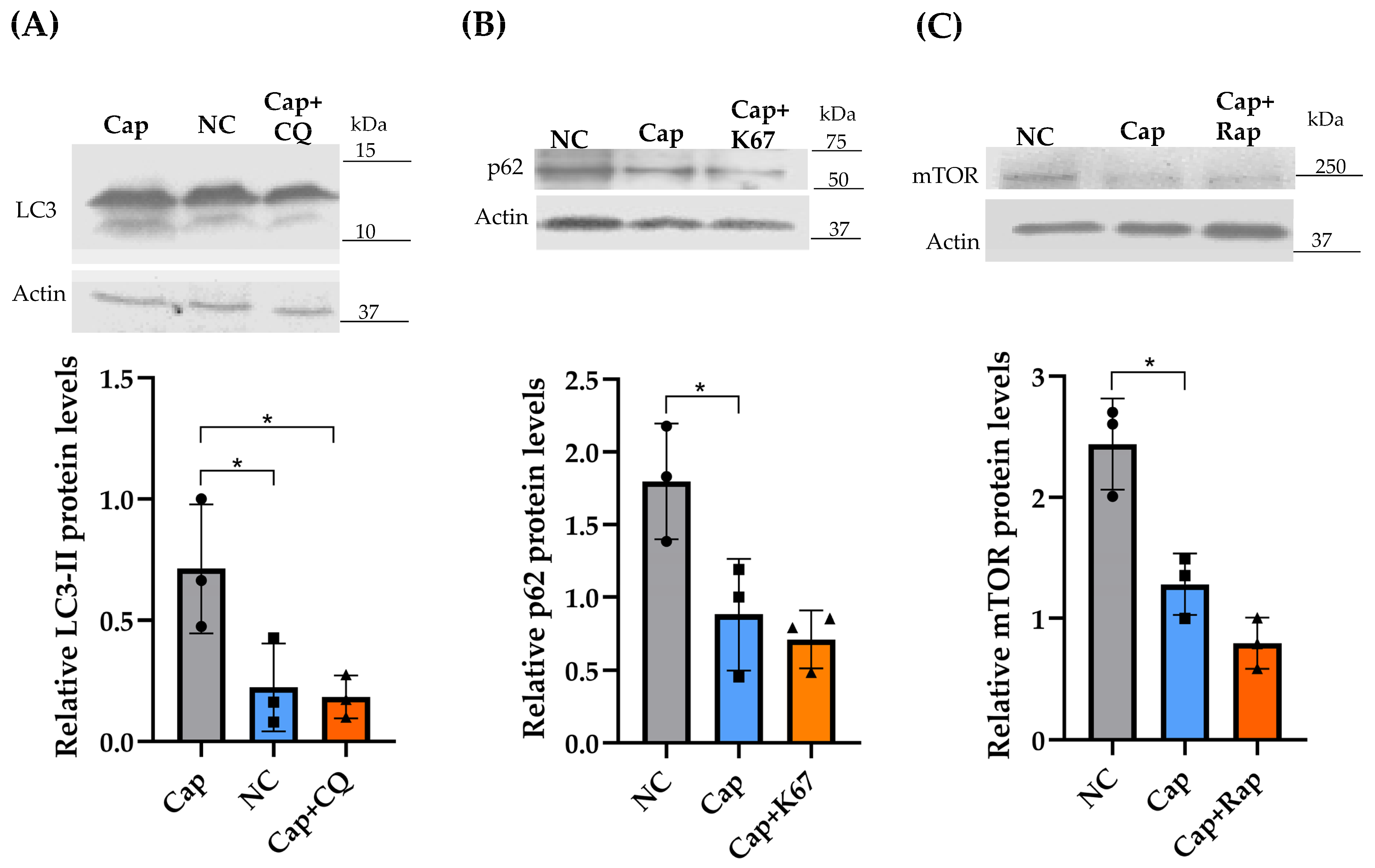

2.5. Effects of CQ, K67, and Rapamycin on LC3, p62/SQSTM1, and mTOR Protein Levels

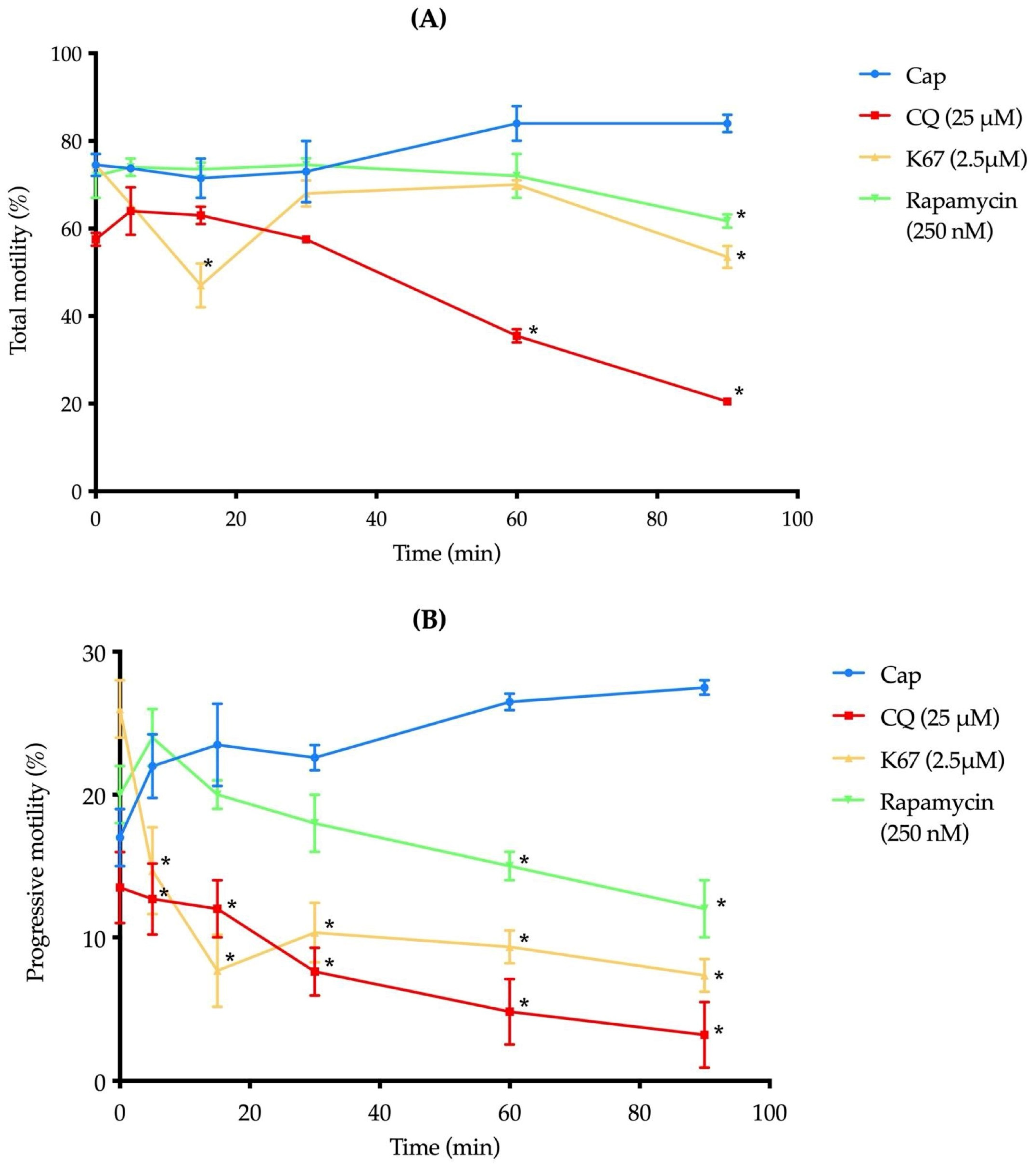

2.6. The Presence of CQ, K67, and Rapamycin Reduces Mouse Sperm Motility

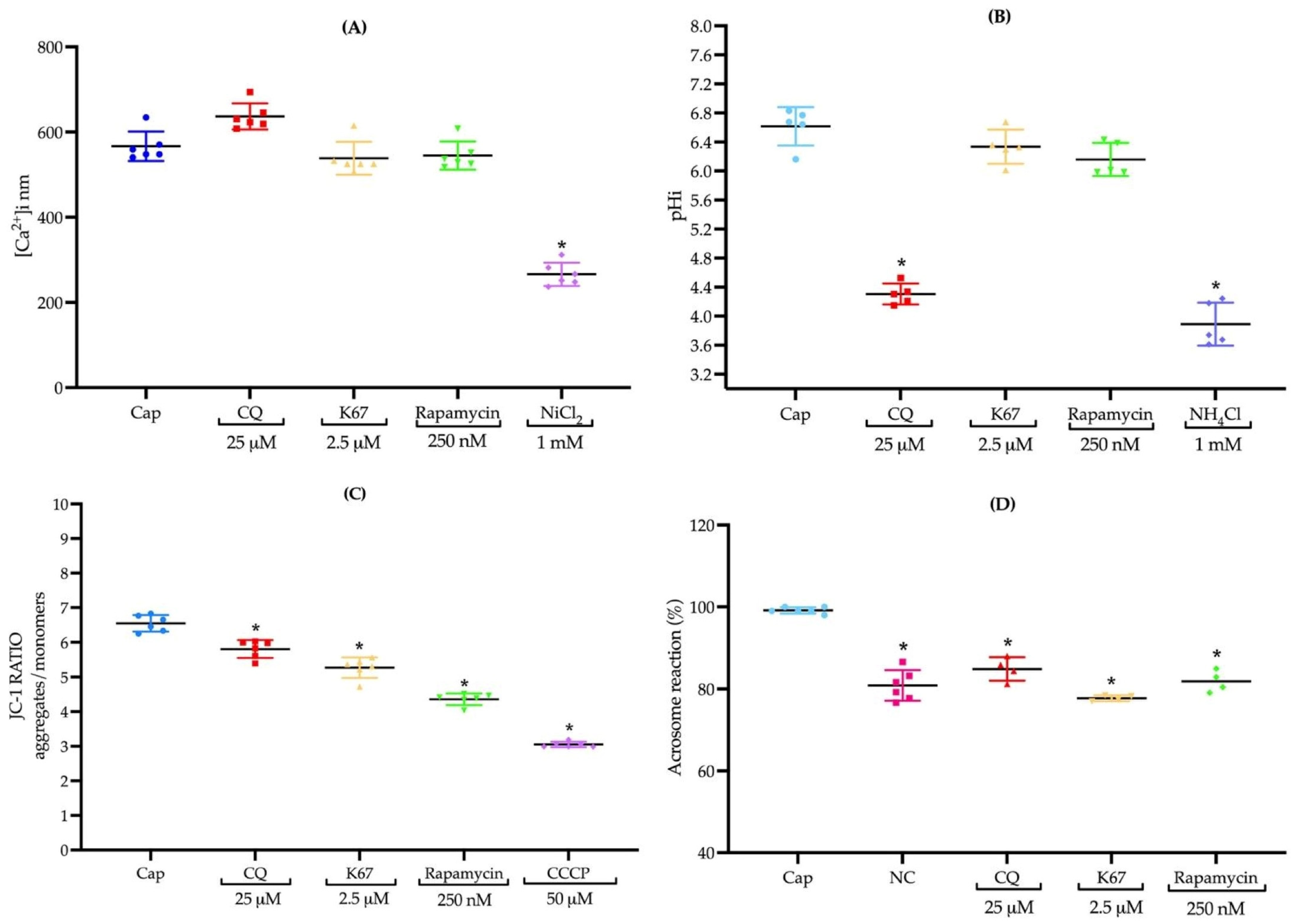

2.7. CQ, K67, and Rapamycin Do Not Induce Changes in Intracellular Calcium Concentrations [Ca2+]i

2.8. Inhibitors Do Not Influence pHi, Except CQ

2.9. The Presence of CQ, K67, and Rapamycin Inhibits Mitochondrial Membrane Potential

2.10. Treatments with CQ, K67, and Rapamycin Impede AR Induction in Mouse Sperm

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Materials and Reagents

4.2. Antibodies

4.3. Animal Procedures

4.4. Sperm Sample Preparation

4.5. Immunofluorescence Assays

4.6. Western Blotting

4.7. Evaluation of Mouse Sperm Viability in the Presence of CQ, K67, and Rapamycin

4.8. Sperm Treatments with the Autophagy Inhibitors CQ, K67, and Rapamycin

4.9. Evaluation of Mouse Sperm Motility in the Presence of CQ, K67, and Rapamycin

4.10. Quantification of the Sperm Population [Ca2+]i in the Presence of CQ, K67, and Rapamycin

4.11. Quantification of the Sperm Population pH in the Presence of CQ, K67, and Rapamycin

4.12. Evaluation of Sperm Mitochondrial Membrane Potential in the Presence of CQ, K67, and Rapamycin

4.13. Evaluation of Mouse Sperm AR Induction in the Presence of CQ, K67, and Rapamycin

4.14. Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| LC3 | Microtubule-associated protein 1A/1B-light chain 3 |

| p62/SQSTM1 | Sequestosome 1 |

| mTOR | Mammalian target of rapamycin |

| pHi | Intracellular pH |

| CQ | Chloroquine |

| AR | Acrosome reaction |

| [Ca2+]i | Intracellular calcium concentration |

| FDA | Fluorescein diacetate |

| PI | Propidium iodide |

| NC | Non-capacitation |

| Cap | Capacitation |

References

- Uribe, P.; Meriño, J.; Matus, C.E.; Schulz, M.; Zambrano, F.; Villegas, J.V.; Conejeros, I.; Taubert, A.; Hermosilla, C.; Sánchez, R. Autophagy is activated in human spermatozoa subjected to oxidative stress and its inhibition impairs sperm quality and promotes cell death. Hum. Reprod. 2022, 37, 680–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, Q.; Yuan, L. Autophagy: A Double-Edged Sword in Male Reproduction. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 15273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, S.; Yao, S.; Yang, H.; Liu, S.; Wang, Y. Autophagy: Regulator of cell death. Cell Death Dis. 2023, 14, 648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kirat, D.; Alahwany, A.M.; Arisha, A.H.; Abdelkhalek, A.; Miyasho, T. Role of Macroautophagy in Mammalian Male Reproductive Physiology. Cells 2023, 12, 1322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, P.; Kaushal, N.; Saleth, L.R.; Ghavami, S.; Dhingra, S.; Kaur, P. Oxidative stress-induced apoptosis and autophagy: Balancing the contrary forces in spermatogenesis. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Mol. Basis Dis. 2023, 1869, 166742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aparicio, I.M.; Espino, J.; Bejarano, I.; Gallardo-Soler, A.; Campo, M.L.; Salido, G.M.; Pariente, J.A.; Peña, F.J.; Tapia, J.A. Autophagy-related proteins are functionally active in human spermatozoa and may be involved in the regulation of cell survival and motility. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 33647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aparicio, I.M.; Rojo-Domínguez, P.; Castillejo-Rufo, A.; Peña, F.J.; Tapia, J.A. The Autophagy Marker LC3 Is Processed during the Sperm Capacitation and the Acrosome Reaction and Translocates to the Acrosome Where It Colocalizes with the Acrosomal Membranes in Horse Spermatozoa. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, W.-H.; Yi, Y.-J.; Sutovsky, M.; Meyers, S.; Sutovsky, P. Autophagy and ubiquitin–proteasome system contribute to sperm mitophagy after mammalian fertilization. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2016, 113, E5261–E5270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Correia, B.; Sousa, M.I.; Ramalho-Santos, J. The mTOR pathway in reproduction: From gonadal function to developmental coordination. Reproduction 2020, 159, R173–R188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreira, B.P.; Oliveira, P.F.; Alves, M.G. Molecular Mechanisms Controlled by mTOR in Male Reproductive System. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 1633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, S.; Cheng, L.; Zhang, Y.; Zhu, C.; Zhu, Z.; Zhu, R.; Cheng, C.Y.; Ye, L.; Zheng, K. A germline-specific role for the mTORC2 component Rictor in maintaining spermatogonial differentiation and intercellular adhesion in mouse testis. Mol. Hum. Reprod. 2018, 24, 244–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berezhnov, A.V.; Soutar, M.P.; Fedotova, E.I.; Frolova, M.S.; Plun-Favreau, H.; Zinchenko, V.P.; Abramov, A.Y. Intracellular pH Modulates Autophagy and Mitophagy. J. Biol. Chem. 2016, 291, 8701–8708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kwon, D.H.; Kim, L.; Song, H.K. pH-dependent regulation of SQSTM1/p62 during autophagy. Autophagy 2019, 15, 180–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazyken, D.; Lentz, S.I.; Wadley, M.; Fingar, D.C. Alkaline intracellular pH (pHi) increases PI3K activity to promote mTORC1 and mTORC2 signaling and function during growth factor limitation. J. Biol. Chem. 2023, 299, 105097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Louwagie, E.J.; Quinn, G.F.L.; Pond, K.L.; Hansen, K.A. Male contraception: Narrative review of ongoing research. Basic. Clin. Androl. 2023, 33, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bjørkøy, G.; Lamark, T.; Pankiv, S.; Øvervatn, A.; Brech, A.; Johansen, T. Monitoring autophagic degradation of p62/SQSTM1. Methods Enzym. 2009, 452, 181–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujioka, Y.; Noda, N.N. Mechanisms of autophagosome formation. Proc. Jpn. Acad. Ser. B 2025, 101, 32–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khawar, M.B.; Gao, H.; Li, W. Mechanism of Acrosome Biogenesis in Mammals. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2019, 7, 195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogov, V.; Dötsch, V.; Johansen, T.; Kirkin, V. Interactions between autophagy receptors and ubiquitin-like proteins form the molecular basis for selective autophagy. Mol. Cell 2014, 53, 167–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.K.; Lee, J.A. Role of the mammalian ATG8/LC3 family in autophagy: Differential and compensatory roles in the spatiotemporal regulation of autophagy. BMB Rep. 2016, 49, 424–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirata, S.; Hoshi, K.; Shoda, T.; Mabuchi, T. Spermatozoon and mitochondrial DNA. Reprod. Med. Biol. 2002, 1, 41–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Runwal, G.; Stamatakou, E.; Siddiqi, F.H.; Puri, C.; Zhu, Y.; Rubinsztein, D.C. LC3-positive structures are prominent in autophagy-deficient cells. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 10147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balestrini, P.A.; Jabloñski, M.; Schiavi-Ehrenhaus, L.J.; Marín-Briggiler, C.I.; Sánchez-Cárdenas, C.; Darszon, A.; Krapf, D.; Buffone, M.G. Seeing is believing: Current methods to observe sperm acrosomal exocytosis in real time. Mol. Reprod. Dev. 2020, 87, 1188–1198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chakraborty, S.; Saha, S. Understanding sperm motility mechanisms and the implication of sperm surface molecules in promoting motility. Middle East Fertil. Soc. J. 2022, 27, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berkamp, S.; Mostafavi, S.; Sachse, C. Structure and function of p62/SQSTM1 in the emerging framework of phase separation. FEBS J. 2021, 288, 6927–6941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, P.F.; Cheng, C.Y.; Alves, M.G. Emerging Role for Mammalian Target of Rapamycin in Male Fertility. Trends Endocrinol. Metab. 2017, 28, 165–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Klionsky, D.J.; Shen, H.M. The emerging mechanisms and functions of microautophagy. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2023, 24, 186–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tanida, I.; Ueno, T.; Kominami, E. LC3 conjugation system in mammalian autophagy. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 2004, 36, 2503–2518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mauthe, M.; Orhon, I.; Rocchi, C.; Zhou, X.; Luhr, M.; Hijlkema, K.J.; Coppes, R.P.; Engedal, N.; Mari, M.; Reggiori, F. Chloroquine inhibits autophagic flux by decreasing autophagosome-lysosome fusion. Autophagy 2018, 14, 1435–1455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.J.; Chen, S.; Huang, K.X.; Le, W.D. Why should autophagic flux be assessed? Acta Pharmacol. Sin. 2013, 34, 595–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hargreaves, C.A.; Rogers, S.; Hills, F.; Rahman, F.; Howell, R.J.; Homa, S.T. Effects of co-trimoxazole, erythromycin, amoxycillin, tetracycline and chloroquine on sperm function in vitro. Hum. Reprod. 1998, 13, 1878–1886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, M.C.; Cai, L.; Zhang, S.; Zhang, X. A cell-penetrating ratiometric probe for simultaneous measurement of lysosomal and cytosolic pH change. Talanta 2018, 178, 355–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Halcrow, P.W.; Geiger, J.D.; Chen, X. Overcoming Chemoresistance: Altering pH of Cellular Compartments by Chloroquine and Hydroxychloroquine. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2021, 9, 627639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seydi, E.; Hassani, M.K.; Naderpour, S.; Arjmand, A.; Pourahmad, J. Cardiotoxicity of chloroquine and hydroxychloroquine through mitochondrial pathway. BMC Pharmacol. Toxicol. 2023, 24, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saito, T.; Ichimura, Y.; Taguchi, K.; Suzuki, T.; Mizushima, T.; Takagi, K.; Hirose, Y.; Nagahashi, M.; Iso, T.; Fukutomi, T.; et al. p62/Sqstm1 promotes malignancy of HCV-positive hepatocellular carcinoma through Nrf2-dependent metabolic reprogramming. Nat. Commun. 2016, 7, 12030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yasuda, D.; Yoshida, I.; Imamura, R.; Katagishi, D.; Takahashi, K.; Kojima, H.; Okabe, T.; Ichimura, Y.; Komatsu, M.; Mashino, T.; et al. Development of p62-Keap1 protein-protein interaction inhibitors as doxorubicin-sensitizers against non-small cell lung cancer. Results Chem. 2022, 4, 100609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Yang, F.; Ye, J.; Dai, X.; Liao, H.; Xing, C.; Jiang, Z.; Peng, C.; Gao, F.; Cao, H. Ginkgo biloba extract alleviates deltamethrin-induced testicular injury by upregulating SKP2 and inhibiting Beclin1-independent autophagy. Phytomedicine 2024, 135, 156245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poon, A.; Saini, H.; Sethi, S.; O’Sullivan, G.A.; Plun-Favreau, H.; Wray, S.; Dawson, L.A.; McCarthy, J.M. The role of SQSTM1 (p62) in mitochondrial function and clearance in human cortical neurons. Stem Cell Rep. 2021, 16, 1276–1289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamming, D.W. Inhibition of the Mechanistic Target of Rapamycin (mTOR)-Rapamycin and Beyond. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Med. 2016, 6, a025924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marafie, S.K.; Al-Mulla, F.; Abubaker, J. mTOR: Its Critical Role in Metabolic Diseases, Cancer, and the Aging Process. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 6141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, Z.; Yue, Q.; Xie, J.; Zhang, S.; He, W.; Bai, S.; Tian, S.; Zhang, Y.; Xiong, M.; Sun, Z.; et al. Rapamycin-mediated mTOR inhibition impairs silencing of sex chromosomes and the pachytene piRNA pathway in the mouse testis. Aging 2019, 11, 185–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borbolis, F.; Ploumi, C.; Palikaras, K. Calcium-mediated regulation of mitophagy: Implications in neurodegenerative diseases. npj Metab. Health Dis. 2025, 3, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohne, Y.; Takahara, T.; Maeda, T. Evaluation of mTOR function by a gain-of-function approach. Cell Cycle 2009, 8, 573–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmerman, M.A.; Wilkison, S.; Qi, Q.; Chen, G.; Li, P.A. Mitochondrial dysfunction contributes to Rapamycin-induced apoptosis of Human Glioblastoma Cells—A synergistic effect with Temozolomide. Int. J. Med. Sci. 2020, 17, 2831–2843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hidalgo, D.M.; Romarowski, A.; Gervasi, M.G.; Navarrete, F.; Balbach, M.; Salicioni, A.M.; Levin, L.R.; Buck, J.; Visconti, P.E. Capacitation increases glucose consumption in murine sperm. Mol. Reprod. Dev. 2020, 87, 1037–1047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Páez, L.; Aguirre-Alvarado, C.; Oviedo, N.; Alcántara-Farfán, V.; Lara-Ramírez, E.E.; Jimenez-Gutierrez, G.E.; Cordero-Martínez, J. Polyamines Influence Mouse Sperm Channels Activity. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, K.; Xue, Y.; Chen, A.; Jiang, Y.; Xie, H.; Shi, Q.; Zhang, S.; Ni, Y. Heat shock protein 90 has roles in intracellular calcium homeostasis, protein tyrosine phosphorylation regulation, and progesterone-responsive sperm function in human sperm. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e115841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naz, R.K. The Effect of Curcumin on Intracellular pH (pHi), Membrane Hyperpolarization and Sperm Motility. J. Reprod. Infertil. 2014, 15, 62–70. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Harshkova, D.; Zielińska, E.; Aksmann, A. Optimization of a microplate reader method for the analysis of changes in mitochondrial membrane potential in Chlamydomonas reinhardtii cells using the fluorochrome JC-1. J. Appl. Phycol. 2019, 31, 3691–3697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrageta, D.F.; Freire-Brito, L.; Oliveira, P.F.; Alves, M.G. Evaluation of Human Spermatozoa Mitochondrial Membrane Potential Using the JC-1 Dye. Curr. Protoc. 2022, 2, e531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pietrobon, E.O.; Domínguez, L.A.; Vincenti, A.E.; Burgos, M.H.; Fornés, M.W. Detection of the Mouse Acrosome Reaction by Acid Phosphatase. Comparison With Chlortetracycline and Electron Microscopy. J. Androl. 2001, 22, 96–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Rodríguez-Páez, L.; Magaña, J.J.; Aguirre-Alvarado, C.; Alcántara-Farfán, V.; Chamorro-Cevallos, G.; Cristóbal-Luna, J.M.; Rosales-Cruz, E.; Reyes-Maldonado, E.; Jiménez-Gutiérrez, G.E.; Cordero-Martínez, J. Autophagy-Related Proteins Influence Mouse Epididymal Sperm Motility. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 11895. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262411895

Rodríguez-Páez L, Magaña JJ, Aguirre-Alvarado C, Alcántara-Farfán V, Chamorro-Cevallos G, Cristóbal-Luna JM, Rosales-Cruz E, Reyes-Maldonado E, Jiménez-Gutiérrez GE, Cordero-Martínez J. Autophagy-Related Proteins Influence Mouse Epididymal Sperm Motility. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2025; 26(24):11895. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262411895

Chicago/Turabian StyleRodríguez-Páez, Lorena, Jonathan J. Magaña, Charmina Aguirre-Alvarado, Verónica Alcántara-Farfán, Germán Chamorro-Cevallos, José Melesio Cristóbal-Luna, Erika Rosales-Cruz, Elba Reyes-Maldonado, Guadalupe Elizabeth Jiménez-Gutiérrez, and Joaquín Cordero-Martínez. 2025. "Autophagy-Related Proteins Influence Mouse Epididymal Sperm Motility" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 26, no. 24: 11895. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262411895

APA StyleRodríguez-Páez, L., Magaña, J. J., Aguirre-Alvarado, C., Alcántara-Farfán, V., Chamorro-Cevallos, G., Cristóbal-Luna, J. M., Rosales-Cruz, E., Reyes-Maldonado, E., Jiménez-Gutiérrez, G. E., & Cordero-Martínez, J. (2025). Autophagy-Related Proteins Influence Mouse Epididymal Sperm Motility. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 26(24), 11895. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262411895