Apiin Promotes Healthy Aging in C. elegans Through Nutritional Activation of DAF-16/FOXO, Enhancing Fatty Acid Catabolism and Oxidative Stress Resistance

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

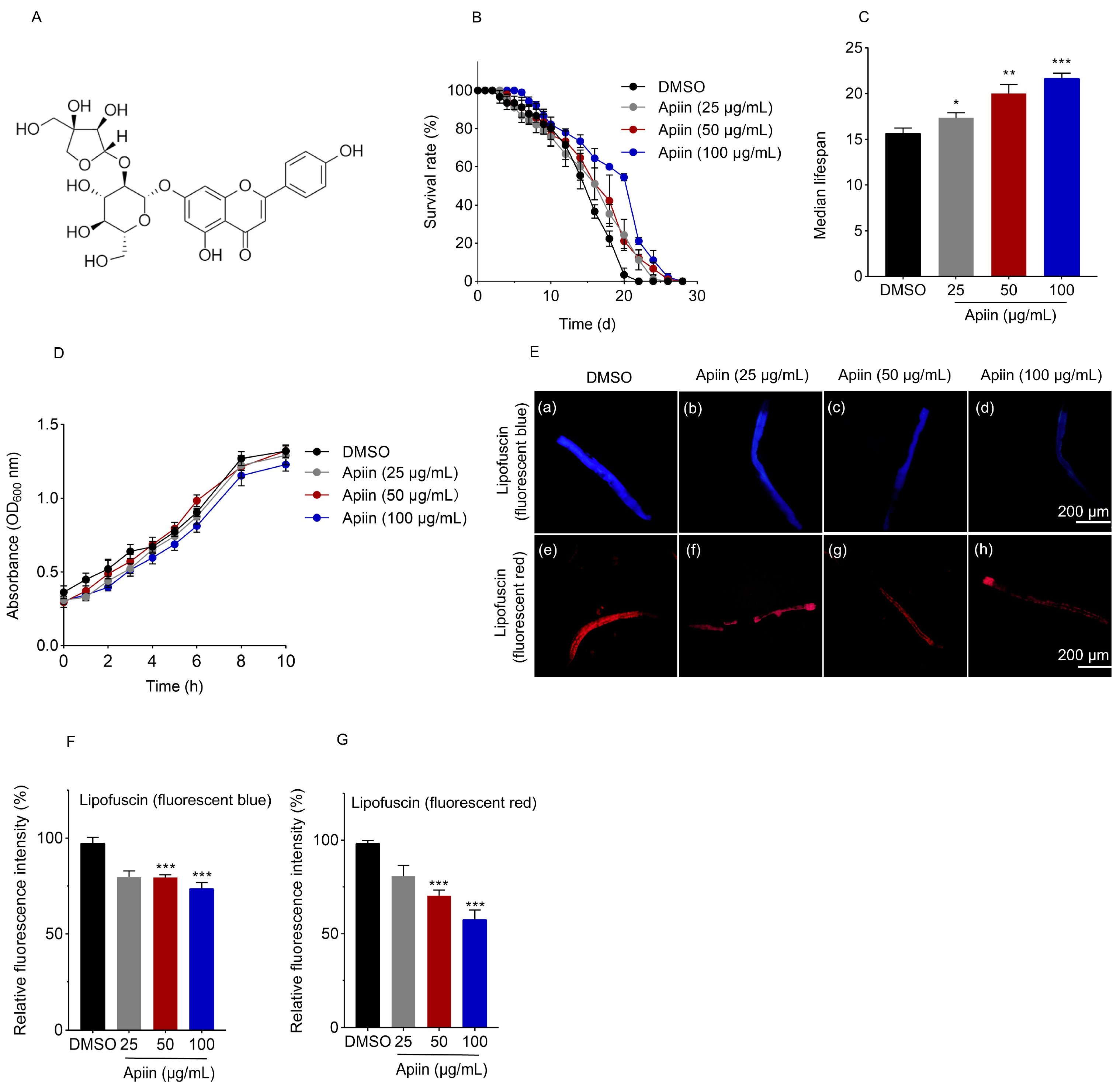

2.1. Apiin Extends C. elegans Lifespan

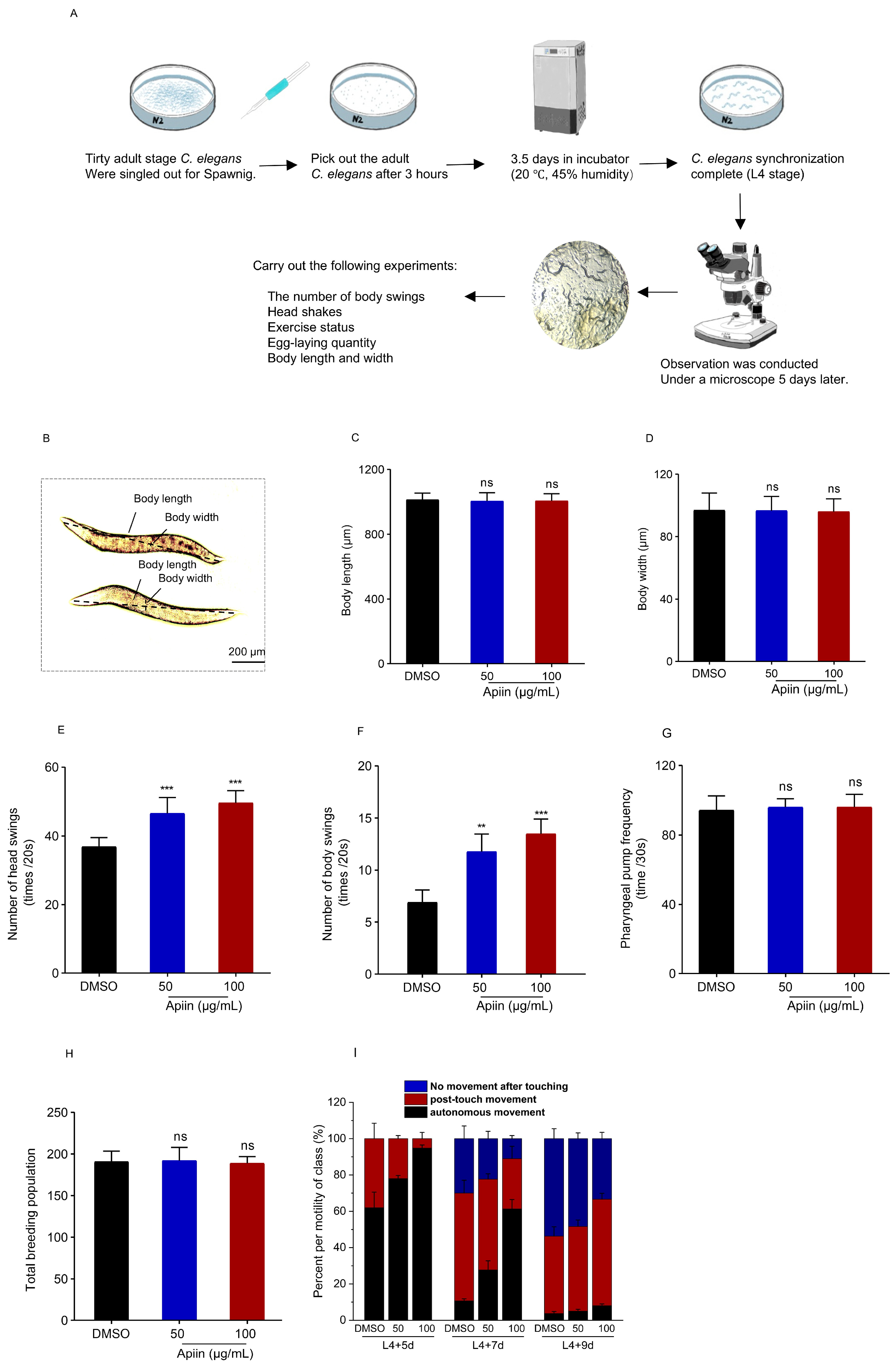

2.2. Healthspan Profile of Apiin-Treated C. elegans

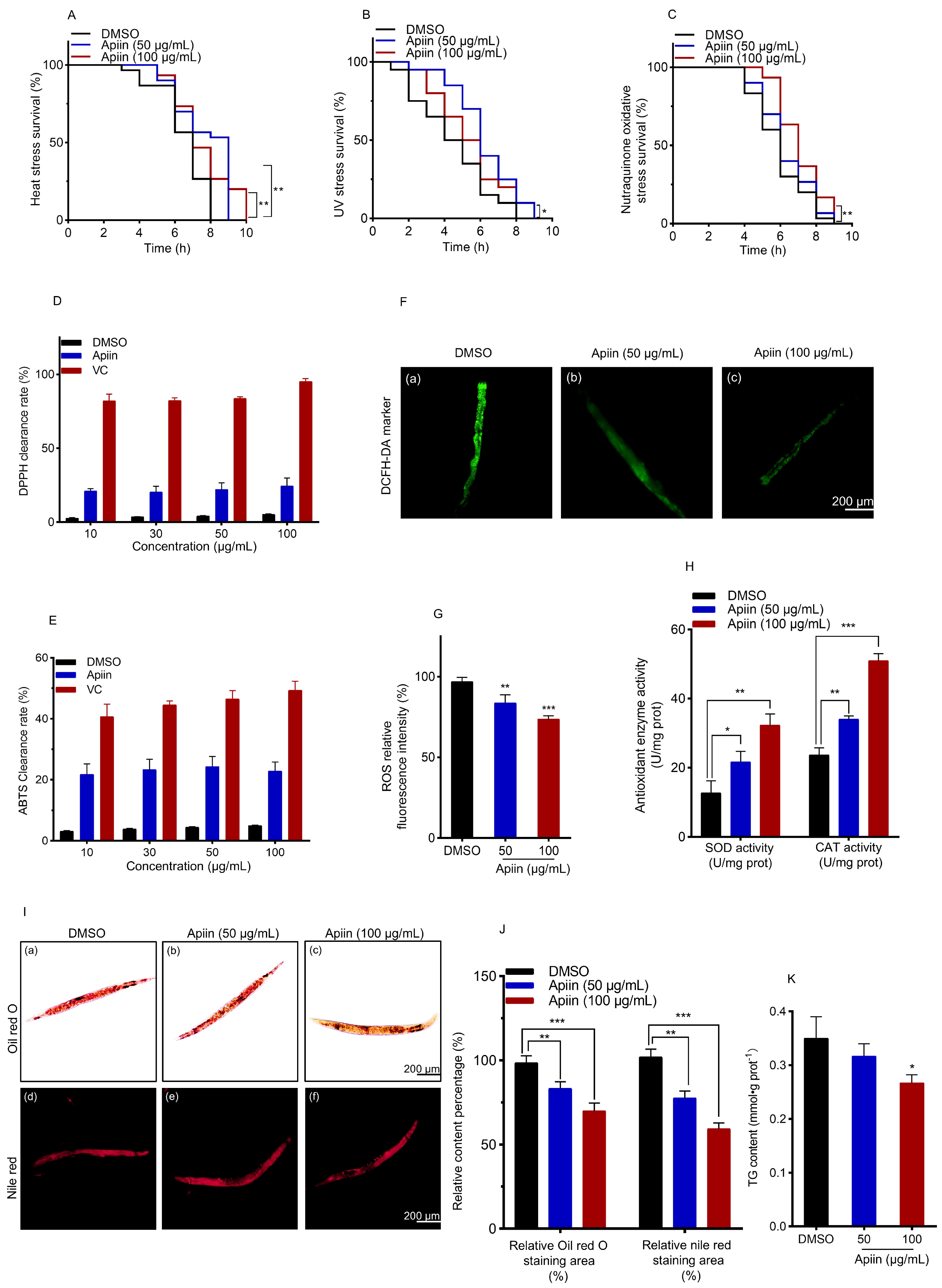

2.3. Apiin Enhances C. elegans Antioxidant Capacity and Reduces Lipid Accumulation

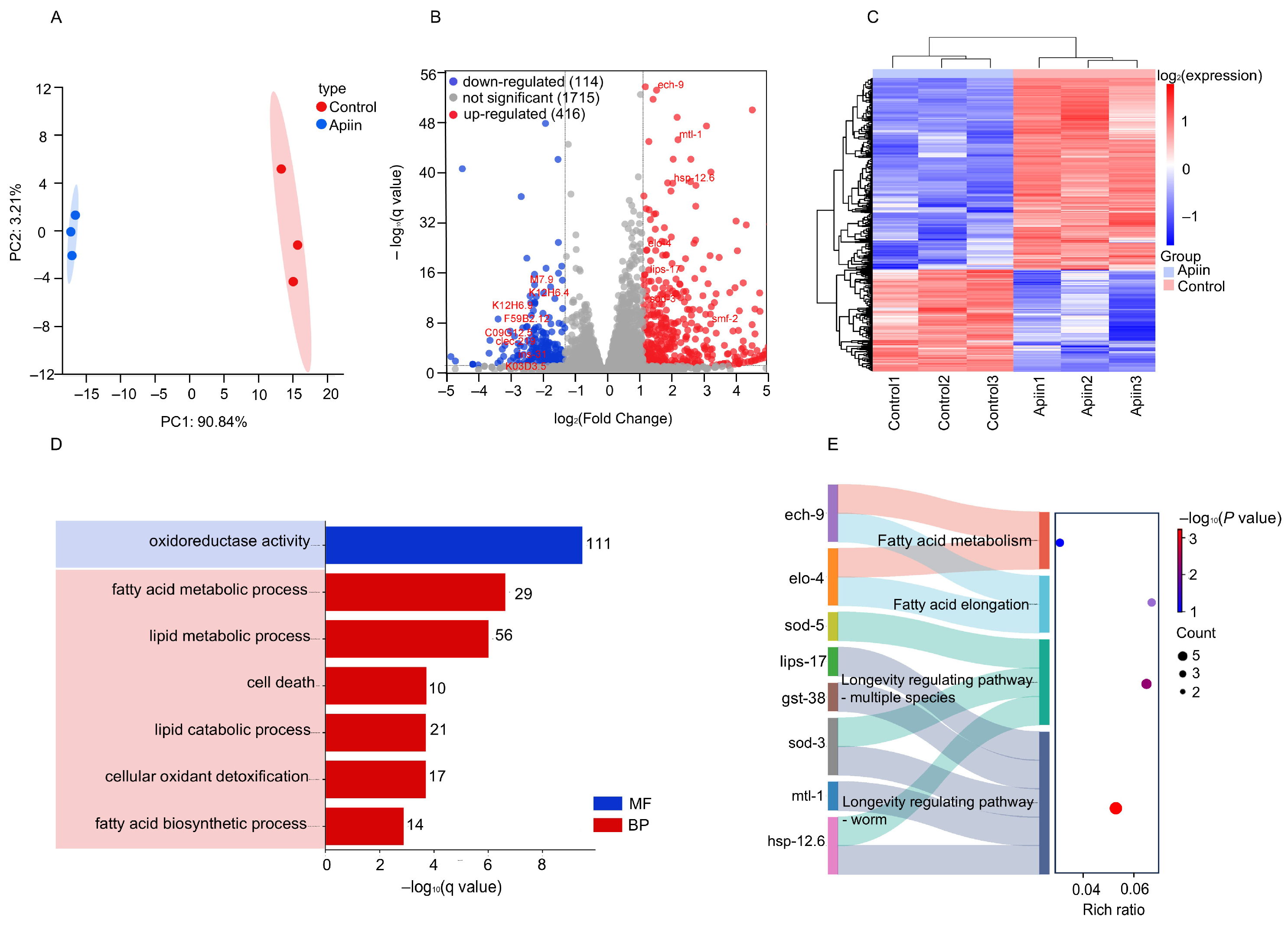

2.4. RNA Sequencing Profile

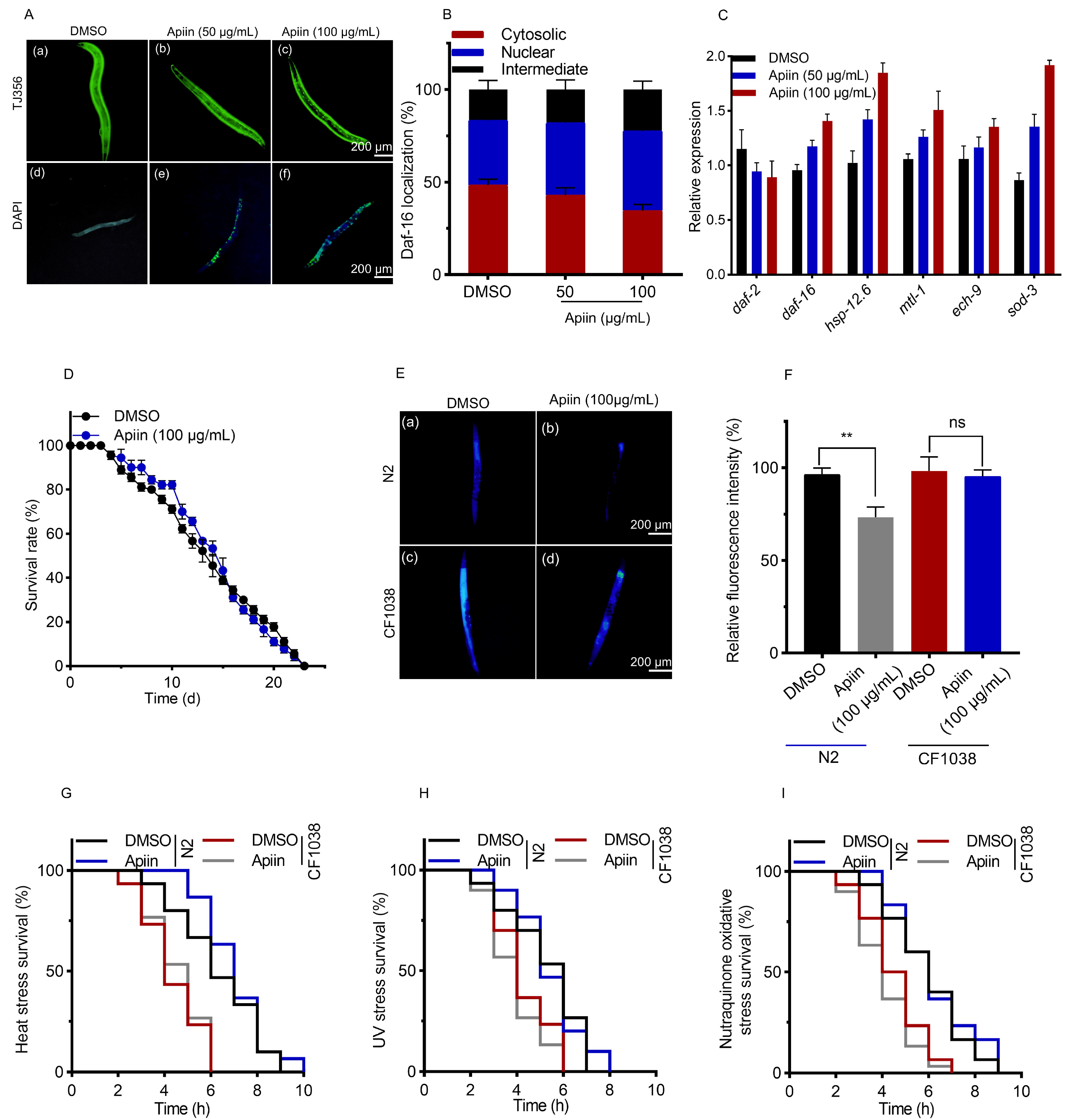

2.5. The Anti-Aging Effect of Apiin Is Mediated by DAF-16

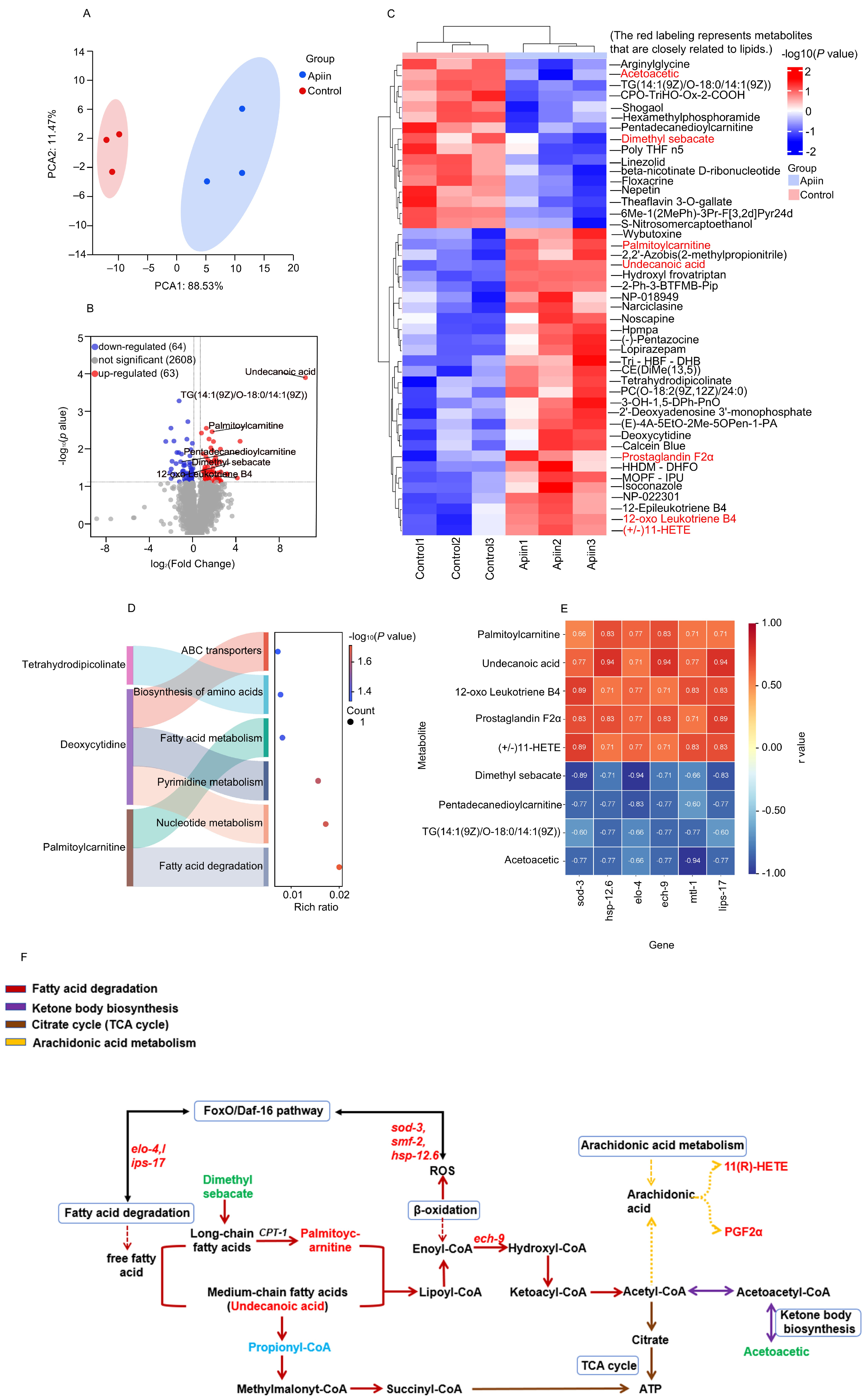

2.6. Metabolomics Analysis Revealed the Mechanism of Action of Apiin on Fatty Acid Catabolism

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Reagents and Materials

4.2. Culture and Treatment of C. elegans

4.3. Lifespan Analysis

4.4. Lipofuscin Assays

4.5. Antibacterial Assay

4.6. Body Length and Width Measurements

4.7. Head and Body Swinging Assays

4.8. Reproduction Assays

4.9. Pharyngeal Pumping Assay

4.10. Stress Tolerance Tests

4.11. In Vitro Antioxidation Assay

4.12. Determination of ROS and Antioxidant Enzymes

4.13. NR Staining

4.14. ORO Staining

4.15. DAF-16::GFP Localization

4.16. Real-Time Quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR)

4.17. TG Assay

4.18. RNA Sequencing

4.19. Metabolomic Profile

4.20. Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| C. elegans | Caenorhabditis elegans |

| ROS | Reactive oxygen species |

| TSPJ | Total saponins from Panax japonicus |

| AGEs | Advanced glycation end products |

| PVAT | Perivascular adipose tissue |

| NR | Nile red |

| ORO | Oil red O |

| RT-qPCR | Real-time quantitative PCR |

| TG | Triglyceride |

References

- Allemann, M.S.; Lee, P.; Beer, J.H.; Saeedi Saravi, S.S. Targeting the redox system for cardiovascular regeneration in aging. Aging Cell 2023, 22, e14020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Culig, L.; Chu, X.; Bohr, V.A. Neurogenesis in aging and age-related neurodegenerative diseases. Ageing Res. Rev. 2022, 78, 101636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Otín, C.; Pietrocola, F.; Roiz-Valle, D.; Galluzzi, L.; Kroemer, G. Meta-hallmarks of aging and cancer. Cell Metab. 2023, 35, 12–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polidori, M.C.; Mecocci, P. Modeling the dynamics of energy imbalance: The free radical theory of aging and frailty revisited. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2022, 181, 235–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mannick, J.B.; Lamming, D.W. Targeting the biology of aging with mTOR inhibitors. Nat. Aging 2023, 3, 642–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bogdanova, D.A.; Kolosova, E.D.; Pukhalskaia, T.V.; Levchuk, K.A.; Demidov, O.N.; Belotserkovskaya, E.V. The Differential Effect of Senolytics on SASP Cytokine Secretion and Regulation of EMT by CAFs. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 4031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarry-Adkins, J.L.; Grant, I.D.; Ozanne, S.E.; Reynolds, R.M.; Aiken, C.E. Efficacy and Side Effect Profile of Different Formulations of Metformin: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Diabetes Ther. 2021, 12, 1901–1914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jomova, K.; Raptova, R.; Alomar, S.Y.; Alwasel, S.H.; Nepovimova, E.; Kuca, K.; Valko, M. Reactive oxygen species, toxicity, oxidative stress, and antioxidants: Chronic diseases and aging. Arch. Toxicol. 2023, 97, 2499–2574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, N.; Zhai, K.; Yin, Q.; Gu, Q.; Zhang, X.; Melencion, M.G.; Chen, Z. Crosstalk between melatonin and reactive oxygen species in fruits and vegetables post-harvest preservation: An update. Front. Nutr. 2023, 10, 1143511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Izadi, M.; Sadri, N.; Abdi, A.; Zadeh, M.M.R.; Jalaei, D.; Ghazimoradi, M.M.; Shouri, S.; Tahmasebi, S. Longevity and anti-aging effects of curcumin supplementation. Geroscience 2024, 46, 2933–2950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheriki, M.; Habibian, M.; Moosavi, S.J. Curcumin attenuates brain aging by reducing apoptosis and oxidative stress. Metab. Brain Dis. 2024, 39, 833–840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Katsube, M.; Ishimoto, T.; Fukushima, Y.; Kagami, A.; Shuto, T.; Kato, Y. Ergothioneine promotes longevity and healthy aging in male mice. Geroscience 2024, 46, 3889–3909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, A.P.; Li, D.; Tan, X.; Xu, R.; Mao, L.X.; Kang, J.J.; Li, S.H.; Liu, Y. Crocin extends lifespan by mitigating oxidative stress and regulating lipid metabolism through the DAF-16/FOXO pathway. Food Funct. 2025, 16, 3369–3383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gu, Q.; Wang, C.; Huang, H.; Wei, D.; Fu, L.; Liu, G.; Zhou, Q.; Yang, J.; Fu, Y. Phlorizin mitigates high glucose-induced metabolic disorders through the IIS pathway in Caenorhabditis elegans. Food Funct. 2025, 16, 3004–3017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Yoon, H.; Park, S.K. Butein Increases Resistance to Oxidative Stress and Lifespan with Positive Effects on the Risk of Age-Related Diseases in Caenorhabditis elegans. Antioxidants 2024, 13, 155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, X.; Li, H.; Lin, D.; Guo, W.; Xu, Z.; Wang, L.; Guan, S. Ginsenoside Prolongs the Lifespan of C. elegans via Lipid Metabolism and Activating the Stress Response Signaling Pathway. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 9668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Shen, X.; Yuan, X.; Huang, J.; Zhu, Y.; Zhu, T.; Zhang, T.; Wu, H.; Wu, Q.; Fan, Y.; et al. Lipopolysaccharide binding protein resists hepatic oxidative stress by regulating lipid droplet homeostasis. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 3213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, Q.; Gong, Y.; Zhu, N.; Shi, Y.; Zhang, C.; Qin, L. Lipids and lipid metabolism in cellular senescence: Emerging targets for age-related diseases. Ageing Res. Rev. 2024, 97, 102294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Wang, S.; Wang, R.; Zhang, Y.; Yuan, Q.; Yuan, C. Total saponins from Panax japonicus regulated the intestinal microbiota to alleviate lipid metabolism disorders in aging mice. Arch. Gerontol. Geriatr. 2024, 125, 105500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, A.; Fusi, F.; Valoti, M. Perivascular adipose tissue modulates the effects of flavonoids on rat aorta rings: Role of superoxide anion and β(3) receptors. Pharmacol. Res. 2022, 180, 106231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pietsch, K.; Saul, N.; Menzel, R.; Stürzenbaum, S.R.; Steinberg, C.E. Quercetin mediated lifespan extension in Caenorhabditis elegans is modulated by age-1, daf-2, sek-1 and unc-43. Biogerontology 2009, 10, 565–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, P.; Jia, J.; Zhang, D.; Xie, J.; Xu, X.; Wei, D. In vitro and in vivo antioxidant activities of a flavonoid isolated from celery (Apium graveolens L. var. dulce). Food Funct. 2014, 5, 50–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mara de Menezes Epifanio, N.; Rykiel Iglesias Cavalcanti, L.; Falcão Dos Santos, K.; Soares Coutinho Duarte, P.; Kachlicki, P.; Ożarowski, M.; Jorge Riger, C.; Siqueira de Almeida Chaves, D. Chemical characterization and in vivo antioxidant activity of parsley (Petroselinum crispum) aqueous extract. Food Funct. 2020, 11, 5346–5356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, B.O.; Che, D.N.; Shin, J.Y.; Kang, H.J.; Kim, J.H.; Jang, S.I. Anti-obesity effects of enzyme-treated celery extract in mice fed with high-fat diet. J. Food Biochem. 2020, 44, e13105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamashita, M.; Fujimori, T.; An, S.; Iguchi, S.; Takenaka, Y.; Kajiura, H.; Yoshizawa, T.; Matsumura, H.; Kobayashi, M.; Ono, E.; et al. The apiosyltransferase celery UGT94AX1 catalyzes the biosynthesis of the flavone glycoside apiin. Plant Physiol. 2023, 193, 1758–1771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, S.; Yamashita, M.; Iguchi, S.; Kihara, T.; Kamon, E.; Ishikawa, K.; Kobayashi, M.; Ishimizu, T. Biochemical Characterization of Parsley Glycosyltransferases Involved in the Biosynthesis of a Flavonoid Glycoside, Apiin. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 17118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Umran, N.S.S.; Mohamed, S.; Lau, S.F.; Mohd Ishak, N.I. Citrus hystrix leaf extract attenuated diabetic-cataract in STZ-rats. J. Food Biochem. 2020, 44, e13258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Zhang, J.; Yan, X.; An, D.; Lei, H. The Anti-atherosclerosis Mechanism of Ziziphora clinopodioides Lam. Based on Network Pharmacology. Cell Biochem. Biophys. 2023, 81, 515–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fox, B.W.; Ponomarova, O.; Lee, Y.U.; Zhang, G.; Giese, G.E.; Walker, M.; Roberto, N.M.; Na, H.; Rodrigues, P.R.; Curtis, B.J.; et al. C. elegans as a model for inter-individual variation in metabolism. Nature 2022, 607, 571–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerrero-Rubio, M.A.; Hernández-García, S.; García-Carmona, F.; Gandía-Herrero, F. Flavonoids’ Effects on Caenorhabditis elegans’ Longevity, Fat Accumulation, Stress Resistance and Gene Modulation Involve mTOR, SKN-1 and DAF-16. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Q.; Qu, Y.; Zhou, X.G.; Chen, J.N.; Luo, H.R.; Wu, G.S. A Dihydroflavonoid Naringin Extends the Lifespan of C. elegans and Delays the Progression of Aging-Related Diseases in PD/AD Models via DAF-16. Oxidative Med. Cell. Longev. 2020, 2020, 6069354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, M.C.; Chen, C.H.; Wang, M.C.; Chen, W.H.; Hu, P.A.; Guo, B.C.; Chang, R.W.; Wang, C.H.; Lee, T.S. Apigenin targets fetuin-A to ameliorate obesity-induced insulin resistance. Int. J. Biol. Sci. 2024, 20, 1563–1577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, H.; Huang, X.; Zhu, H.H.; Wang, N.; Xie, C.; Zhou, Y.L.; Shi, H.L.; Chen, M.M.; Wu, Y.R.; Ruan, Z.H.; et al. Apigenin ameliorates non-eosinophilic inflammation, dysregulated immune homeostasis and mitochondria-mediated airway epithelial cell apoptosis in chronic obese asthma via the ROS-ASK1-MAPK pathway. Phytomedicine 2023, 111, 154646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, J.; Pi, C.; Wang, G. Inhibition of PI3K/Akt/mTOR pathway by apigenin induces apoptosis and autophagy in hepatocellular carcinoma cells. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2018, 103, 699–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, Y.; Zhang, T.; Li, X.; Yu, T.; Meng, F.; Luan, Y.; Cong, H.; Wu, X. Apigenin Improves Ovarian Dysfunction Induced by 4-Vinylcyclohexene Diepoxide via the AKT/FOXO3a Pathway. Cell Biochem. Funct. 2024, 42, e70015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, H.T.; Wang, Z.L.; Chen, N.H.; Huang, W.; Zou, J.L.; Tian, Y.G.; Ye, G.; Huang, J.; Wu, R.; Ye, M. Insights into the Mechanisms of Sugar Acceptor Selectivity of Plant Flavonoid Apiosyltransferases. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2025, 147, 20631–20643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.T.; Wang, Z.L.; Chen, K.; Yao, M.J.; Zhang, M.; Wang, R.S.; Zhang, J.H.; Ågren, H.; Li, F.D.; Li, J.; et al. Insights into the missing apiosylation step in flavonoid apiosides biosynthesis of Leguminosae plants. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 6658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pincus, Z.; Mazer, T.C.; Slack, F.J. Autofluorescence as a measure of senescence in C. elegans: Look to red, not blue or green. Aging 2016, 8, 889–898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Chen, J.; Cui, G.; Dai, Y.; Song, M.; Zhou, C.; Hu, Q.; Chen, Q.; Wang, H.; Chen, W.; et al. Germline loss in C. elegans enhances longevity by disrupting adhesion between niche and stem cells. EMBO J. 2024, 43, 4000–4019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukhopadhyay, A.; Tissenbaum, H.A. Reproduction and longevity: Secrets revealed by C. elegans. Trends Cell Biol. 2007, 17, 65–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, P.; Wang, J.; Wang, J.; Hu, X.; Wang, W.; Lu, S.; Sheng, Y. Anoectochilus roxburghii Extract Extends the Lifespan of Caenorhabditis elegans through Activating the daf-16/FoxO Pathway. Antioxidants 2024, 13, 945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.; Jia, Y.; Wang, C.; Zhou, W.; Shu, Y.; Zhang, K.; Zeng, X.; Guo, R. Lonicera japonica polysaccharides improve longevity and fitness of Caenorhabditis elegans by activating DAF-16. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2023, 229, 81–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Fang, M.; Tu, X.; Mo, X.; Zhang, L.; Yang, B.; Wang, F.; Kim, Y.B.; Huang, C.; Chen, L.; et al. Dietary Polyphenols as Anti-Aging Agents: Targeting the Hallmarks of Aging. Nutrients 2024, 16, 3305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imb, M.; Véghelyi, Z.; Maurer, M.; Kühnel, H. Exploring Senolytic and Senomorphic Properties of Medicinal Plants for Anti-Aging Therapies. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 10419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, A.; Schurman, S.H.; Bektas, A.; Kaileh, M.; Roy, R.; Wilson, D.M., 3rd; Sen, R.; Ferrucci, L. Aging and Inflammation. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Med. 2024, 14, a041197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andonian, B.J.; Hippensteel, J.A.; Abuabara, K.; Boyle, E.M.; Colbert, J.F.; Devinney, M.J.; Faye, A.S.; Kochar, B.; Lee, J.; Litke, R.; et al. Inflammation and aging-related disease: A transdisciplinary inflammaging framework. Geroscience 2025, 47, 515–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Z.; Gao, S.; Chen, C.; Xu, W.; Xiao, P.; Chen, Z.; Du, C.; Chen, B.; Gao, Y.; Wang, C.; et al. The natural product salicin alleviates osteoarthritis progression by binding to IRE1α and inhibiting endoplasmic reticulum stress through the IRE1α-IκBα-p65 signaling pathway. Exp. Mol. Med. 2022, 54, 1927–1939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uddin, M.J.; Farjana, M.; Moni, A.; Hossain, K.S.; Hannan, M.A.; Ha, H. Prospective Pharmacological Potential of Resveratrol in Delaying Kidney Aging. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 8258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.; Luo, T.; Zhang, H.; Fan, X.; Zhang, Q.; Chen, H. Kaempferol enhances intestinal repair and inhibits the hyperproliferation of aging intestinal stem cells in Drosophila. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2024, 12, 1491740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tissenbaum, H.A. DAF-16: FOXO in the Context of C. elegans. Curr. Top. Dev. Biol. 2018, 127, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zečić, A.; Braeckman, B.P. DAF-16/FoxO in Caenorhabditis elegans and Its Role in Metabolic Remodeling. Cells 2020, 9, 109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laguerre, M.; Bily, A.; Roller, M.; Birtić, S. Mass Transport Phenomena in Lipid Oxidation and Antioxidation. Annu. Rev. Food Sci. Technol. 2017, 8, 391–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greatorex, S.; Kaur, S.; Xirouchaki, C.E.; Goh, P.K.; Wiede, F.; Genders, A.J.; Tran, M.; Jia, Y.; Raajendiran, A.; Brown, W.A.; et al. Mitochondria- and NOX4-dependent antioxidant defense mitigates progression to nonalcoholic steatohepatitis in obesity. J. Clin. Investig. 2023, 134, e162533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angelova, P.R.; Esteras, N.; Abramov, A.Y. Mitochondria and lipid peroxidation in the mechanism of neurodegeneration: Finding ways for prevention. Med. Res. Rev. 2021, 41, 770–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Cui, P. Reactive Carbonyl Species Derived from Omega-3 and Omega-6 Fatty Acids. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2015, 63, 6293–6296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhi, X.; Sun, Y.; Cai, F.; Wang, S.; Gao, H.; Wu, F.; Zhang, L.; Shen, Z. Oxidized Low-Density Lipoprotein (Ox-LDL)-Triggered Double-Lock Probe for Spatiotemporal Lipoprotein Oxidation and Atherosclerotic Plaque Imaging. Adv. Healthc. Mater. 2023, 12, e2301595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kang, M.R.; Park, K.H.; Oh, S.J.; Yun, J.; Lee, C.W.; Lee, M.Y.; Han, S.B.; Kang, J.S. Cardiovascular protective effect of glabridin: Implications in LDL oxidation and inflammation. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2015, 29, 914–918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezaei, A.; Kocsis-Jutka, V.; Gunes, Z.I.; Zeng, Q.; Kislinger, G.; Bauernschmitt, F.; Isilgan, H.B.; Parisi, L.R.; Kaya, T.; Franzenburg, S.; et al. Correction of dysregulated lipid metabolism normalizes gene expression in oligodendrocytes and prolongs lifespan in female poly-GA C9orf72 mice. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 3442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farias-Pereira, R.; Zhang, Z.; Park, C.S.; Kim, D.; Kim, K.H.; Park, Y. Butein inhibits lipogenesis in Caenorhabditis elegans. Biofactors 2020, 46, 777–787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamauchi, S.; Sugiura, Y.; Yamaguchi, J.; Zhou, X.; Takenaka, S.; Odawara, T.; Fukaya, S.; Fujisawa, T.; Naguro, I.; Uchiyama, Y.; et al. Mitochondrial fatty acid oxidation drives senescence. Sci. Adv. 2024, 10, eado5887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wong, C.H.; Haque, M.A.; Chang, H.C. Superoxide dismutase SOD-3 regulates redox homeostasis in the intestine. microPubl. Biol. 2023, 1, e161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; He, Y.; Sen, B.; Wang, G. Reactive oxygen species and their applications toward enhanced lipid accumulation in oleaginous microorganisms. Bioresour. Technol. 2020, 307, 123234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Q.; Liu, Z.; Guo, Y.; Lu, S.; Du, H.; Cao, Y. Antioxidant capacity of flavonoids from Folium Artemisiae Argyi and the molecular mechanism in Caenorhabditis elegans. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2021, 279, 114398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Chen, Z.; Zhang, C.; Kang, W. Physicochemical properties and biological activities of Tremella hydrocolloids. Food Chem. 2023, 407, 135164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Navarro-Hortal, M.D.; Romero-Márquez, J.M.; Esteban-Muñoz, A.; Sánchez-González, C.; Rivas-García, L.; Llopis, J.; Cianciosi, D.; Giampieri, F.; Sumalla-Cano, S.; Battino, M.; et al. Strawberry (Fragaria × ananassa cv. Romina) methanolic extract attenuates Alzheimer’s beta amyloid production and oxidative stress by SKN-1/NRF and DAF-16/FOXO mediated mechanisms in C. elegans. Food Chem. 2022, 372, 131272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerrero-Rubio, M.A.; Hernández-García, S.; Escribano, J.; Jiménez-Atiénzar, M.; Cabanes, J.; García-Carmona, F.; Gandía-Herrero, F. Betalain health-promoting effects after ingestion in Caenorhabditis elegans are mediated by DAF-16/FOXO and SKN-1/Nrf2 transcription factors. Food Chem. 2020, 330, 127228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cock, P.J.; Fields, C.J.; Goto, N.; Heuer, M.L.; Rice, P.M. The Sanger FASTQ file format for sequences with quality scores, and the Solexa/lllumina FASTQ variants. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010, 38, 1767–1771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Qian, Y.; Ding, X.; Guo, X.; Bian, N.; Chen, Y.; Han, S.; Song, W.; Wei, L.; Jiang, S. Apiin Promotes Healthy Aging in C. elegans Through Nutritional Activation of DAF-16/FOXO, Enhancing Fatty Acid Catabolism and Oxidative Stress Resistance. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 11888. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262411888

Qian Y, Ding X, Guo X, Bian N, Chen Y, Han S, Song W, Wei L, Jiang S. Apiin Promotes Healthy Aging in C. elegans Through Nutritional Activation of DAF-16/FOXO, Enhancing Fatty Acid Catabolism and Oxidative Stress Resistance. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2025; 26(24):11888. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262411888

Chicago/Turabian StyleQian, Yimin, Xuebin Ding, Xinping Guo, Nan Bian, Ying Chen, Shaoyu Han, Wu Song, Lin Wei, and Shuang Jiang. 2025. "Apiin Promotes Healthy Aging in C. elegans Through Nutritional Activation of DAF-16/FOXO, Enhancing Fatty Acid Catabolism and Oxidative Stress Resistance" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 26, no. 24: 11888. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262411888

APA StyleQian, Y., Ding, X., Guo, X., Bian, N., Chen, Y., Han, S., Song, W., Wei, L., & Jiang, S. (2025). Apiin Promotes Healthy Aging in C. elegans Through Nutritional Activation of DAF-16/FOXO, Enhancing Fatty Acid Catabolism and Oxidative Stress Resistance. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 26(24), 11888. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262411888