Identification of COL3A1, PLAU, and SPP1 as Key Biomarkers for Early Detection of Esophageal Cancer

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

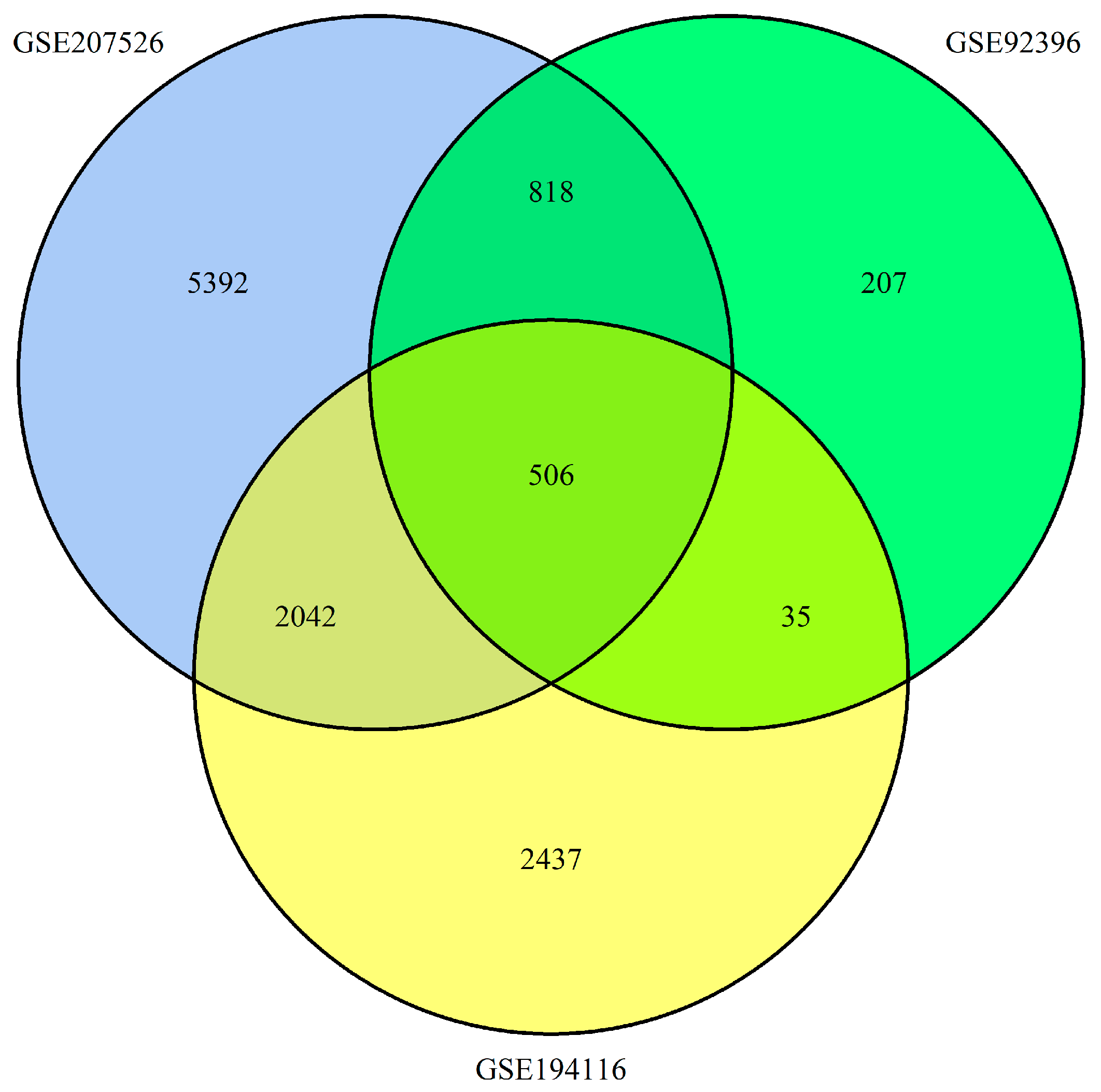

2.1. Identification of DEGs in Esophageal Cancer

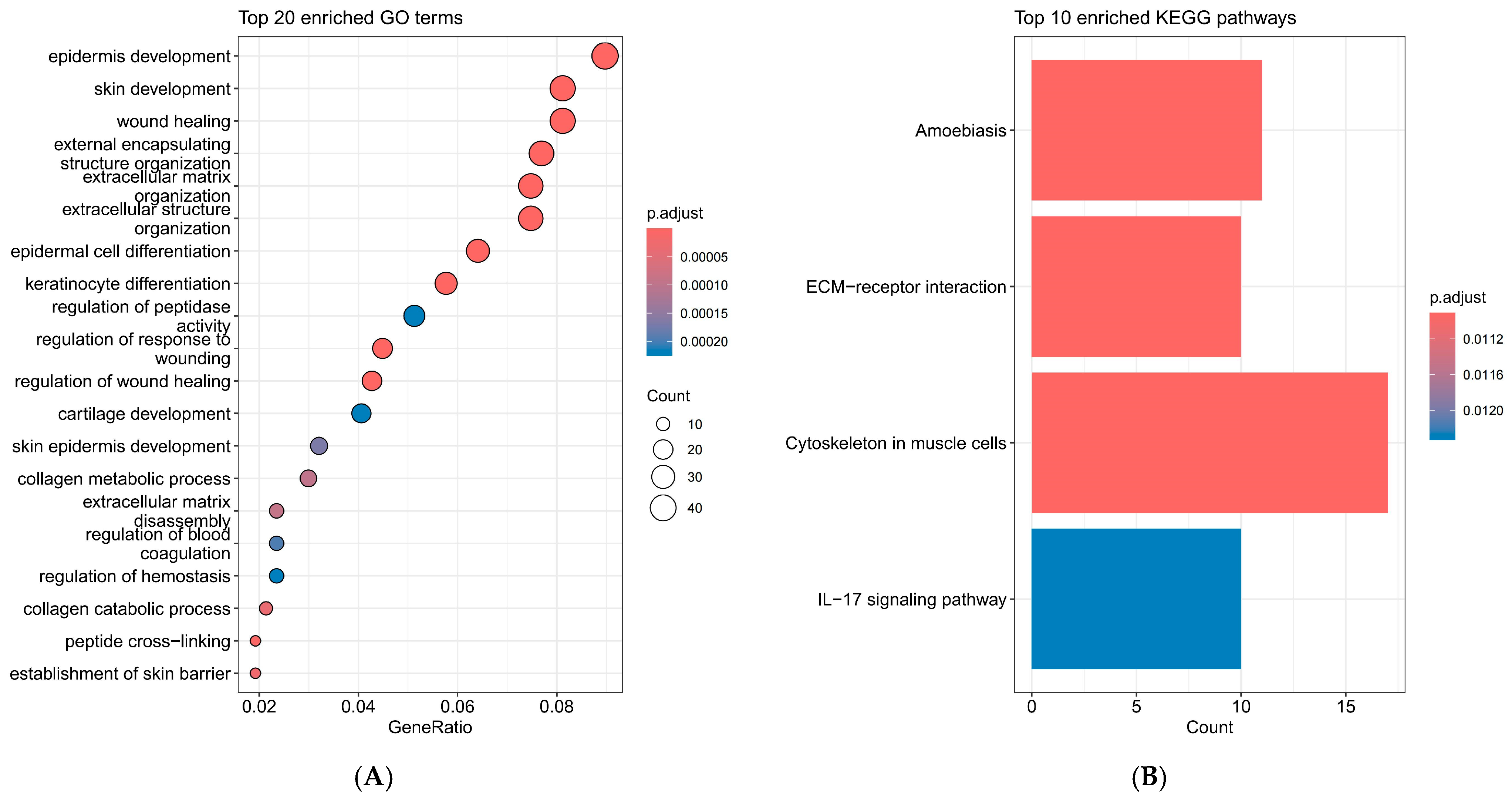

2.2. Interpretation of KEGG and GO Enrichment Analysis Results for DEGs

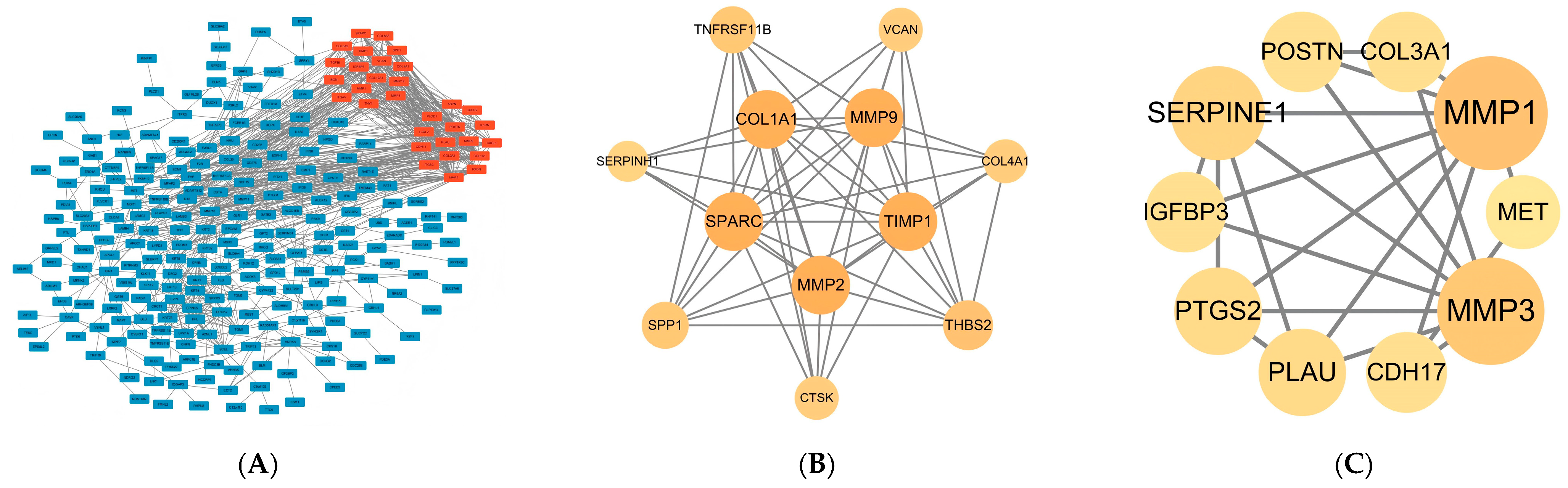

2.3. PPI Network Construction and Hub Gene Selection

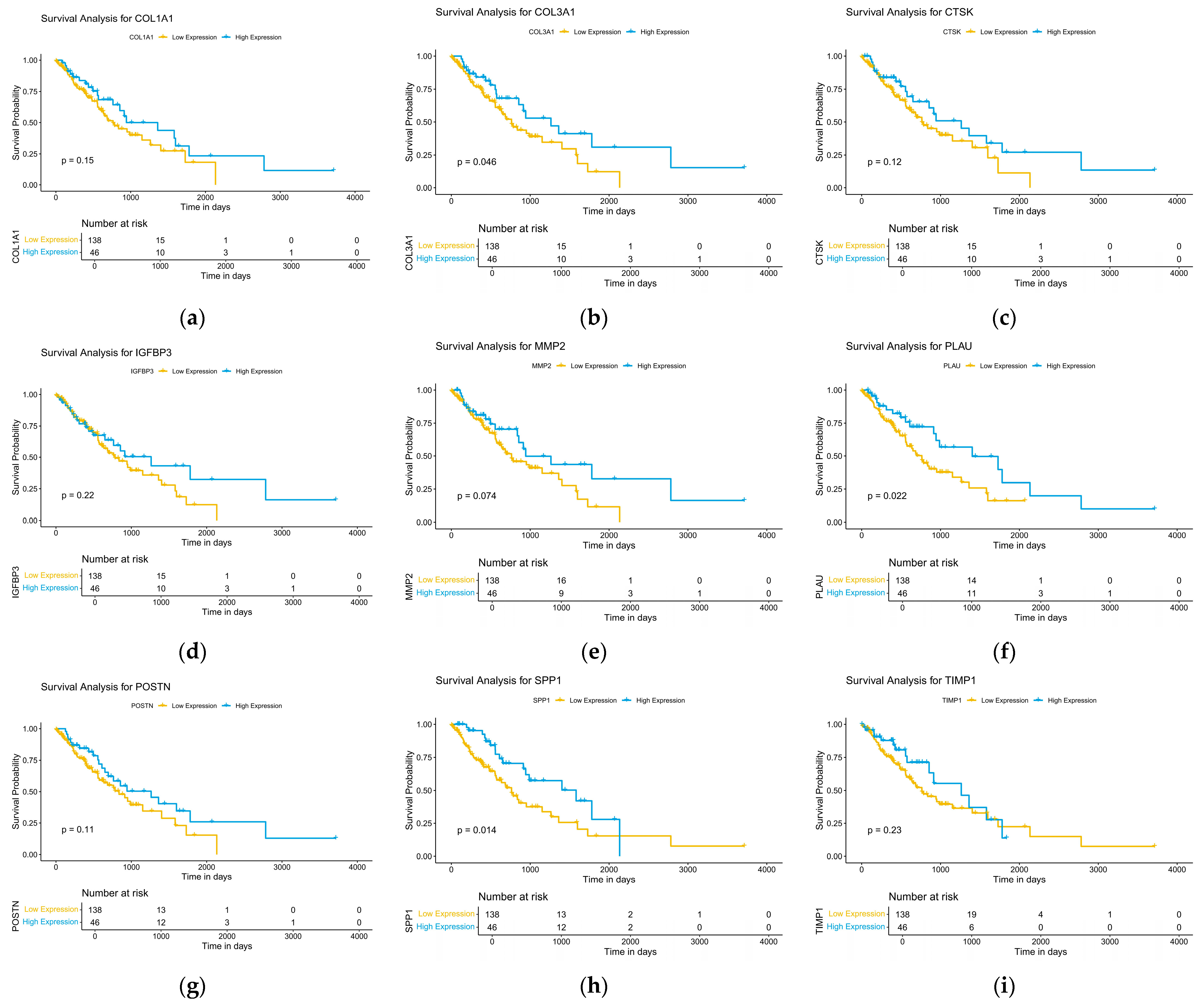

2.4. Analysis of Survival Data

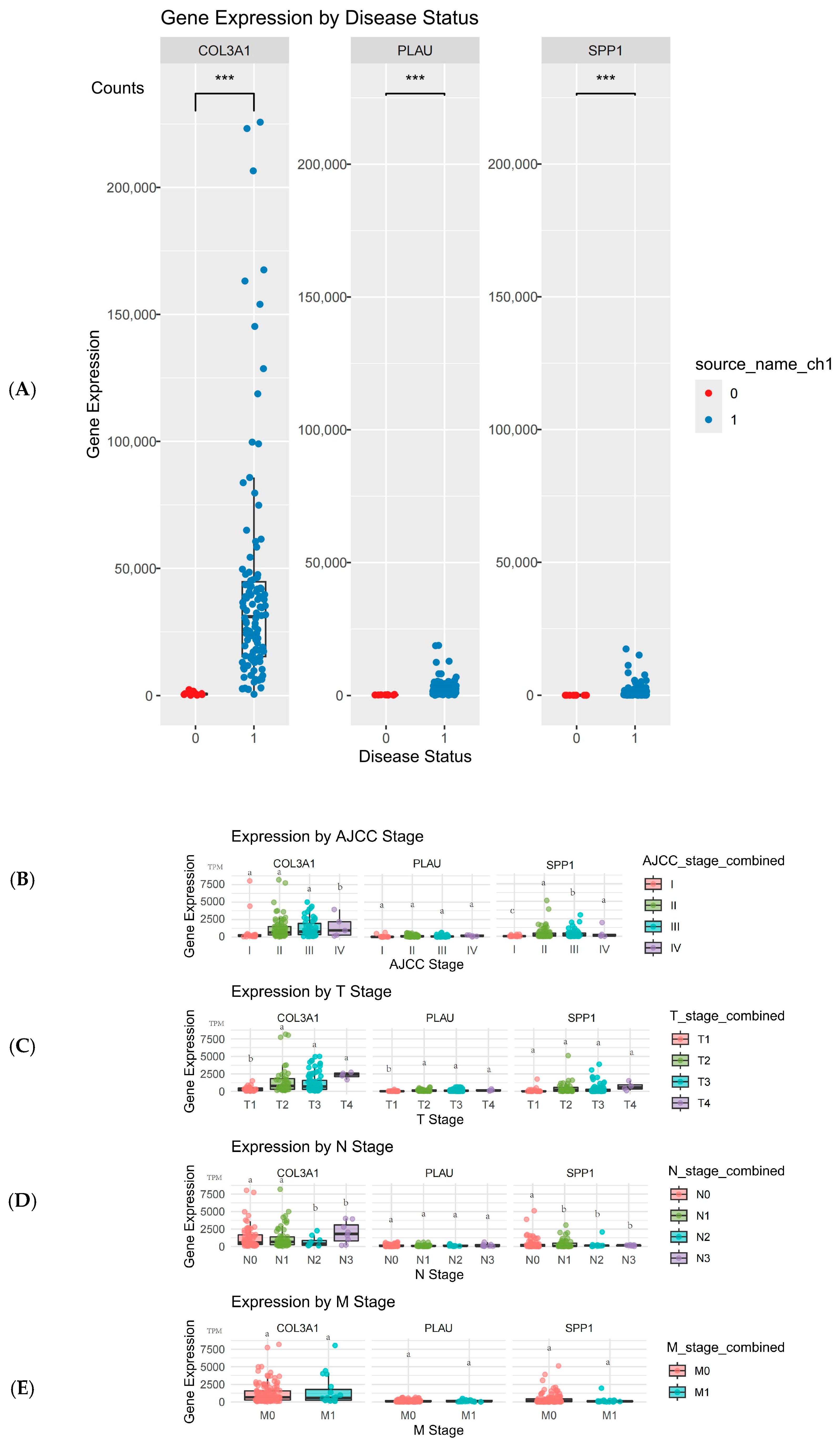

2.5. Validation and Expression Analysis of Hub Genes

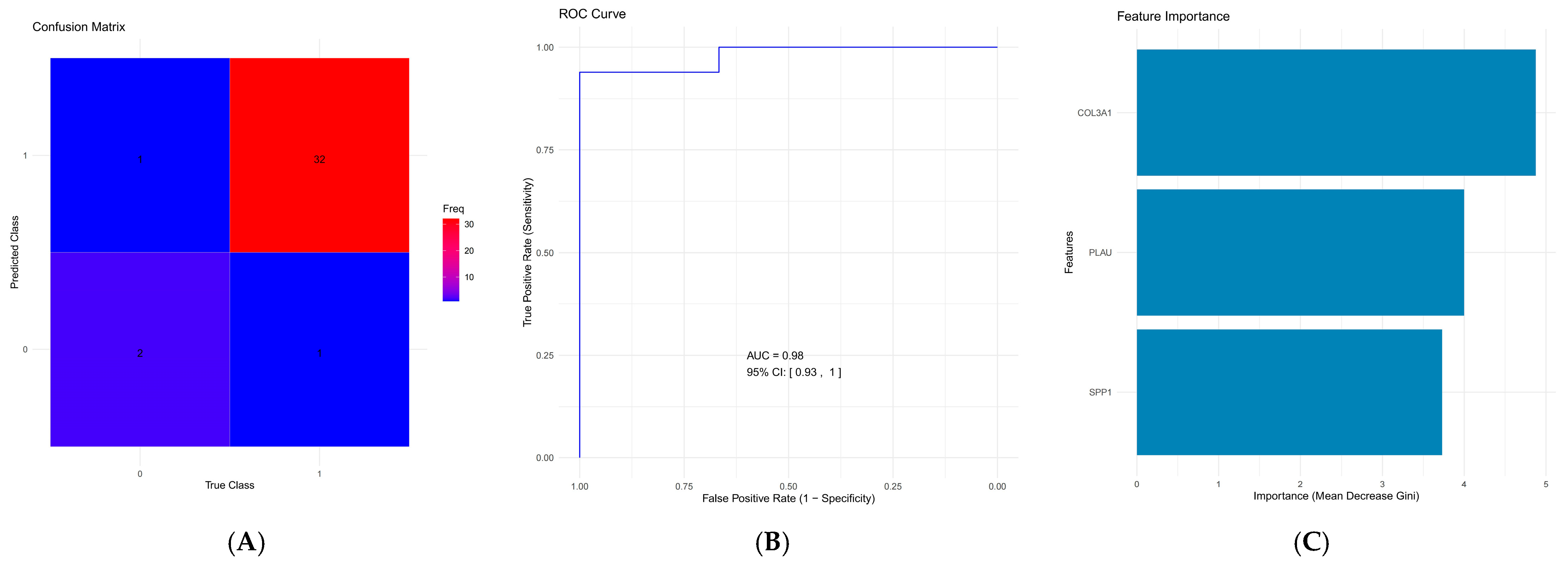

2.6. Development and Validation of the Diagnostic Model

3. Discussion

3.1. Enrichment of Key Pathways in Esophageal Cancer Progression

3.2. Identification of Hub Genes and Their Prognostic Significance

3.3. Development of a Diagnostic Model for Early-Stage Esophageal Cancer Based on COL3A1, PLAU, and SPP1

3.4. Study Limitations and Significance

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Sample Collection and Processing

4.2. Identification of DEGs

4.3. KEGG and GO Enrichment Analyses of DEGs

4.4. PPI Network Construction and Module Analysis

4.5. Hub Genes Selection and Analysis

4.6. Survival Analysis

4.7. Validation of Hub Genes and Differential Expression Analysis

4.8. Diagnostic Model Construction and Validation

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Murphy, G.; McCormack, V.; Abedi-Ardekani, B.; Arnold, M.; Camargo, M.C.; Dar, N.A.; Dawsey, S.M.; Etemadi, A.; Fitzgerald, R.C.; Fleischer, D.E.; et al. International cancer seminars: A focus on esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Ann. Oncol. 2017, 28, 2086–2093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y. Epidemiology of esophageal cancer. World J. Gastroenterol. 2013, 19, 5598–5606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rai, V.; Abdo, J.; Agrawal, D.K. Biomarkers for early detection, prognosis, and therapeutics of esophageal cancers. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 3316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Momose, K.; Yamasaki, M.; Tanaka, K.; Miyazaki, Y.; Makino, T.; Takahashi, T.; Kurokawa, Y.; Nakajima, K.; Takiguchi, S.; Mori, M.; et al. MLH1 expression predicts the response to preoperative therapy and is associated with PD-L1 expression in esophageal cancer. Oncol. Lett. 2017, 14, 958–964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajani, J.A.; Wang, X.; Hayashi, Y.; Maru, D.; Welsh, J.; Hofstetter, W.L.; Lee, J.H.; Bhutani, M.S.; Suzuki, A.; Berry, D.A.; et al. Validated biomarker signatures that predict pathologic response to preoperative chemoradiation therapy with high specificity and desirable sensitivity levels in patients with esophageal cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 2011, 29, 4027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, S.; Lu, C.C.; Yang, L.Y.; Wang, J.J.; Wang, B.S.; Cai, H.Q.; Hao, J.J.; Xu, X.; Cai, Y.; Zhang, Y.; et al. ANXA2 promotes esophageal cancer progression by activating MYC-HIF1A-VEGF axis. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 2018, 37, 183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Li, X.; Chen, S.; Zhang, T.; Song, L.; Pei, J.; Sun, G.; Guo, L. IPO5 Mediates EMT and Promotes Esophageal Cancer Development through the RAS-ERK Pathway. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2022, 2022, 6570879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Lyu, Z.; Qin, Y.; Wang, X.; Sun, L.; Zhang, Y.; Gong, L.; Wu, S.; Han, S.; Tang, Y.; et al. FOXO1 promotes tumor progression by increased M2 macrophage infiltration in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Theranostics 2020, 10, 11535–11548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.-C.; Huang, X.; Chen, J.; Li, Y.; Cong, Y.; Qu, B.-L.; Feng, S.-Q.; Liu, F. Long-term efficacy and predictors of pembrolizumab-based regimens in patients with advanced esophageal cancer in the real world. World J. Gastroenterol. 2023, 29, 5641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, Y.; Wang, Y.; Hu, M.; Lu, X.; Sun, G. Identification of oncogenes and tumor-suppressor genes with hepatocellular carcinoma: A comprehensive analysis based on TCGA and GEO datasets. Front. Genet. 2022, 13, 934883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuan, F.; Pan, X.; Chen, L.; Zhang, Y.-H.; Huang, T.; Cai, Y.-D. Analysis of protein–protein functional associations by using gene ontology and KEGG pathway. BioMed Res. Int. 2019, 2019, 4963289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szklarczyk, D.; Kirsch, R.; Koutrouli, M.; Nastou, K.; Mehryary, F.; Hachilif, R.; Gable, A.L.; Fang, T.; Doncheva, N.T.; Pyysalo, S.; et al. The STRING database in 2023: Protein-protein association networks and functional enrichment analyses for any sequenced genome of interest. Nucleic Acids Res 2023, 51, D638–D646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saito, R.; Smoot, M.E.; Ono, K.; Ruscheinski, J.; Wang, P.-L.; Lotia, S.; Pico, A.R.; Bader, G.D.; Ideker, T. A travel guide to Cytoscape plugins. Nat. Methods 2012, 9, 1069–1076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Menon, S.M.P.; Elengoe, A. Evaluation of the role of kras gene in colon cancer pathway using string and Cytoscape software. Biomed. Res. Ther. 2020, 7, 3835–3842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.; Wang, W.; Yao, W.; Yang, Z.; Gao, P.; Liu, M.; Wang, H.; Chen, S.; Wang, D.; Wang, W.; et al. Gambogic acid affects ESCC progression through regulation of PI3K/AKT/mTOR signal pathway. J. Cancer 2020, 11, 5568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kang, M.R.; Kim, M.S.; Kim, S.S.; Ahn, C.H.; Yoo, N.J.; Lee, S.H. NF-κB signalling proteins p50/p105, p52/p100, RelA, and IKKε are over-expressed in oesophageal squamous cell carcinomas. Pathology 2009, 41, 622–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bao, X.-H.; Takaoka, M.; Hao, H.-F.; Wang, Z.-G.; Fukazawa, T.; Yamatsuji, T.; Sakurama, K.; Sun, D.-S.; Nagasaka, T.; Fujiwara, T.; et al. Esophageal cancer exhibits resistance to a novel IGF-1R inhibitor NVP-AEW541 with maintained RAS-MAPK activity. Anticancer Res. 2012, 32, 2827–2834. [Google Scholar]

- Luo, Q.; Du, R.; Liu, W.; Huang, G.; Dong, Z.; Li, X. PI3K/Akt/mTOR signaling pathway: Role in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma, regulatory mechanisms and opportunities for targeted therapy. Front. Oncol. 2022, 12, 852383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, Z.; Yang, F.; Wang, Y.; Zhao, H.; Wei, F.; Zhang, P.; Zhang, X.; Ren, X. Significantly different immunological score in lung adenocarcinoma and squamous cell carcinoma and a proposal for a new immune staging system. Oncoimmunology 2020, 9, 1828538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Zheng, Z.; Wang, L.; Chen, R.; He, M.; Zhao, X.; Jin, L.; Yao, J. Deciphering STAT3’s negative regulation of LHPP in ESCC progression through single-cell transcriptomics analysis. Mol. Med. 2024, 30, 192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, L.; Wang, J.; Hou, S.; Liu, S.; Zhang, Q.; Zhu, S.; Liu, S.; Zhang, S. Unraveling the tumor microenvironment of esophageal squamous cell carcinoma through single-cell sequencing: A comprehensive review. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Rev. Cancer 2025, 1880, 189264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Hu, J.; Xu, H. Integrated single-cell and bulk RNA sequencing reveals immune-related SPP1+ macrophages as a potential strategy for predicting the prognosis and treatment of liver fibrosis and hepatocellular carcinoma. Front. Immunol. 2024, 15, 1455383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, H.; Yang, L.; Zeng, Q.; Chen, W.; Zhao, H.; Wu, L.; Qin, L.; Yu, Q.Q. Machine Learning Predicts the Oxidative Stress Subtypes Provide an Innovative Insight into Colorectal Cancer. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2023, 2023, 1737501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Gan, L.; Duan, X.; Tuo, B.; Zhang, H.; Liu, S.; Lian, Y.; Liu, E.; Sun, Z. Single-cell transcriptomics reveals hypoxia-driven iCAF_PLAU is associated with stemness and immunosuppression in anorectal malignant melanoma. J. Gastroenterol. 2025, 60, 1242–1258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, G.; Zhao, K.; Bao, K.; Li, J. Radiation increases COL1A1, COL3A1, and COL1A2 expression in breast cancer. Open Med. 2022, 17, 329–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.-Q.; Tang, Z.-X.; Yu, D.; Cui, S.-J.; Jiang, Y.-H.; Zhang, Q.; Wang, J.; Yang, P.-Y.; Liu, F. Epithelial but not stromal expression of collagen alpha-1 (III) is a diagnostic and prognostic indicator of colorectal carcinoma. Oncotarget 2016, 7, 8823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Chen, C.; Wang, J.; Wei, M.; Liu, G.; Qin, Y.; She, L.; Liu, Y.; Huang, D.; Tian, Y.; et al. Overexpressed PLAU and its potential prognostic value in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. PeerJ 2021, 9, e10746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ning, P.; Du, F.; Gong, X.; Yuan, J.; Ding, C.; Zhao, X.; Li, W. PLAU plays a functional role in driving lung squamous cell carcinoma metastasis. Genes Dis. 2024, 11, 554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Li, S.; Cui, X.; Wang, Y. microRNA-944 inhibits breast cancer cell proliferation and promotes cell apoptosis by reducing SPP1 through inactivating the PI3K/Akt pathway. Apoptosis 2023, 28, 1546–1563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsubara, E.; Yano, H.; Pan, C.; Komohara, Y.; Fujiwara, Y.; Zhao, S.; Shinchi, Y.; Kurotaki, D.; Suzuki, M. The significance of SPP1 in lung cancers and its impact as a marker for protumor tumor-associated macrophages. Cancers 2023, 15, 2250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, C.; Sun, L.; Jiang, C.; Zhou, H.; Gu, L.; Liu, Y.; Xu, Q. SPP1, analyzed by bioinformatics methods, promotes the metastasis in colorectal cancer by activating EMT pathway. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2017, 91, 1167–1177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, K.; Bian, Z.; Zhang, Q.; Guo, X.; Yin, C.; Wang, Y.; Zhou, K.; Wan, S.; Shi, M.; Bao, D.; et al. Machine learning-based genome-wide interrogation of somatic copy number aberrations in circulating tumor DNA for early detection of hepatocellular carcinoma. EBioMedicine 2020, 56, 102811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yi, X.; Luo, L.; Zhu, Y.; Deng, H.; Liao, H.; Shen, Y.; Zheng, Y. SPP1 facilitates cell migration and invasion by targeting COL11A1 in lung adenocarcinoma. Cancer Cell Int. 2022, 22, 324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yin, W.; Zhu, H.; Tan, J.; Xin, Z.; Zhou, Q.; Cao, Y.; Wu, Z.; Wang, L.; Zhao, M.; Jiang, X.; et al. Identification of collagen genes related to immune infiltration and epithelial-mesenchymal transition in glioma. Cancer Cell Int. 2021, 21, 276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; Huang, Q.; Ning, H.; Liu, W.; Han, X. Extracellular matrix protein 1 in cancer: Multifaceted roles in tumor progression, prognosis, and therapeutic targeting. Arch. Pharm. Res. 2025, 48, 843–857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Gene Symbol | Full Name | Function |

|---|---|---|

| CDH17 | Cadherin 17 | Mediates calcium-dependent cell-cellcell–cell adhesion in the intestines |

| COL1A1 | Collagen, Type I, Alpha 1 | Produces type I collagen, which is critical for skin, bone, tendon, and other connective tissues |

| COL3A1 | Collagen, Type III, Alpha 1 | Provides structure to tissues such as skin, lung, and vascular tissues |

| COL4A1 | Collagen, Type IV, Alpha 1 | A major component of basement membranes, essential for tissue structure and function |

| CTSK | Cathepsin K | A protease involved in the breakdown of collagen in bones, critical for bone resorption |

| IGFBP3 | Insulin-Like Growth Factor Binding Protein 3 | Regulates the availability of insulin-like growth factors, involved in cell growth and apoptosis |

| MET | MET Proto-Oncogene, Receptor Tyrosine Kinase | Encodes a protein involved in cell growth, development, and wound healing |

| MMP1 | Matrix Metallopeptidase 1 | Breaks down interstitial collagens, involved in tissue remodeling and repair |

| MMP2 | Matrix Metallopeptidase 2 | Degrades type IV collagen in the ECM, involved in tissue remodeling and metastasis |

| MMP3 | Matrix Metallopeptidase 3 | Degrades various components of the ECM, involved in tissue remodeling |

| MMP9 | Matrix Metallopeptidase 9 | Degrades components of the ECM, involved in tissue remodeling, inflammation, and cancer metastasis |

| PLAU | Plasminogen Activator, Urokinase | Converts plasminogen to plasmin, involved in breaking down blood clots and tissue remodeling |

| POSTN | Periostin | Involved in tissue repair, bone development, and maintaining the integrity of the ECM |

| PTGS2 | Prostaglandin-Endoperoxide Synthase 2 | An enzyme involved in inflammation and pain, also known as COX-2 |

| SERPINH1 | Serpin Family H Member 1 | A collagen chaperone involved in collagen biosynthesis and folding |

| SPARC | Secreted Protein, Acidic, Cysteine-Rich (Osteonectin) | Regulates cell-matrix interactions, cell migration, and tissue remodeling |

| SPP1 | Secreted Phosphoprotein 1 (Osteopontin) | Involved in bone remodeling, immune responses, and cell adhesion |

| THBS2 | Thrombospondin 2 | Regulates angiogenesis, tissue repair, and cell adhesion |

| TIMP1 | Tissue Inhibitor of Metalloproteinases 1 | Inhibits matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) and regulates ECM degradation, cell growth, and apoptosis |

| TNFRSF11B | Tumor Necrosis Factor Receptor Superfamily Member 11b | Acts as a decoy receptor for RANKL, inhibiting osteoclastogenesis and bone resorption |

| VCAN | Versican | A large extracellular matrix proteoglycan involved in cell adhesion, proliferation, and ECM organization |

| Clinical Characteristics | N | (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age(years) | <65 | 108 | 58.4 |

| ≥65 | 77 | 41.6 | |

| Gender | Male | 158 | 85.4 |

| Female | 27 | 14.6 | |

| Race | Asian | 46 | 24.9 |

| American | 5 | 2.7 | |

| White | 114 | 61.6 | |

| Not report | 20 | 10.8 | |

| AJCC Stage | I | 18 | 9.7 |

| II | 79 | 42.7 | |

| III | 56 | 30.3 | |

| IV | 9 | 4.9 | |

| T classification | T0 | 1 | 0.5 |

| T1 | 31 | 16.8 | |

| T2 | 43 | 23.2 | |

| T3 | 88 | 47.6 | |

| T4 | 5 | 2.7 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhang, H.; Cheng, X.; Zhang, M.; Zuo, Y.; Zhu, S.; Zuo, Z.; Wang, X.; Lu, S.; Gao, X. Identification of COL3A1, PLAU, and SPP1 as Key Biomarkers for Early Detection of Esophageal Cancer. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 11890. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262411890

Zhang H, Cheng X, Zhang M, Zuo Y, Zhu S, Zuo Z, Wang X, Lu S, Gao X. Identification of COL3A1, PLAU, and SPP1 as Key Biomarkers for Early Detection of Esophageal Cancer. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2025; 26(24):11890. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262411890

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhang, Hong, Xin Cheng, Mengdi Zhang, Yixin Zuo, Shilu Zhu, Zhaorui Zuo, Xingliang Wang, Shan Lu, and Xuan Gao. 2025. "Identification of COL3A1, PLAU, and SPP1 as Key Biomarkers for Early Detection of Esophageal Cancer" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 26, no. 24: 11890. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262411890

APA StyleZhang, H., Cheng, X., Zhang, M., Zuo, Y., Zhu, S., Zuo, Z., Wang, X., Lu, S., & Gao, X. (2025). Identification of COL3A1, PLAU, and SPP1 as Key Biomarkers for Early Detection of Esophageal Cancer. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 26(24), 11890. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262411890