Luteinizing Hormone-Releasing Hormone (LHRH)-Targeted Treatment in Ovarian Cancer

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Search Strategy

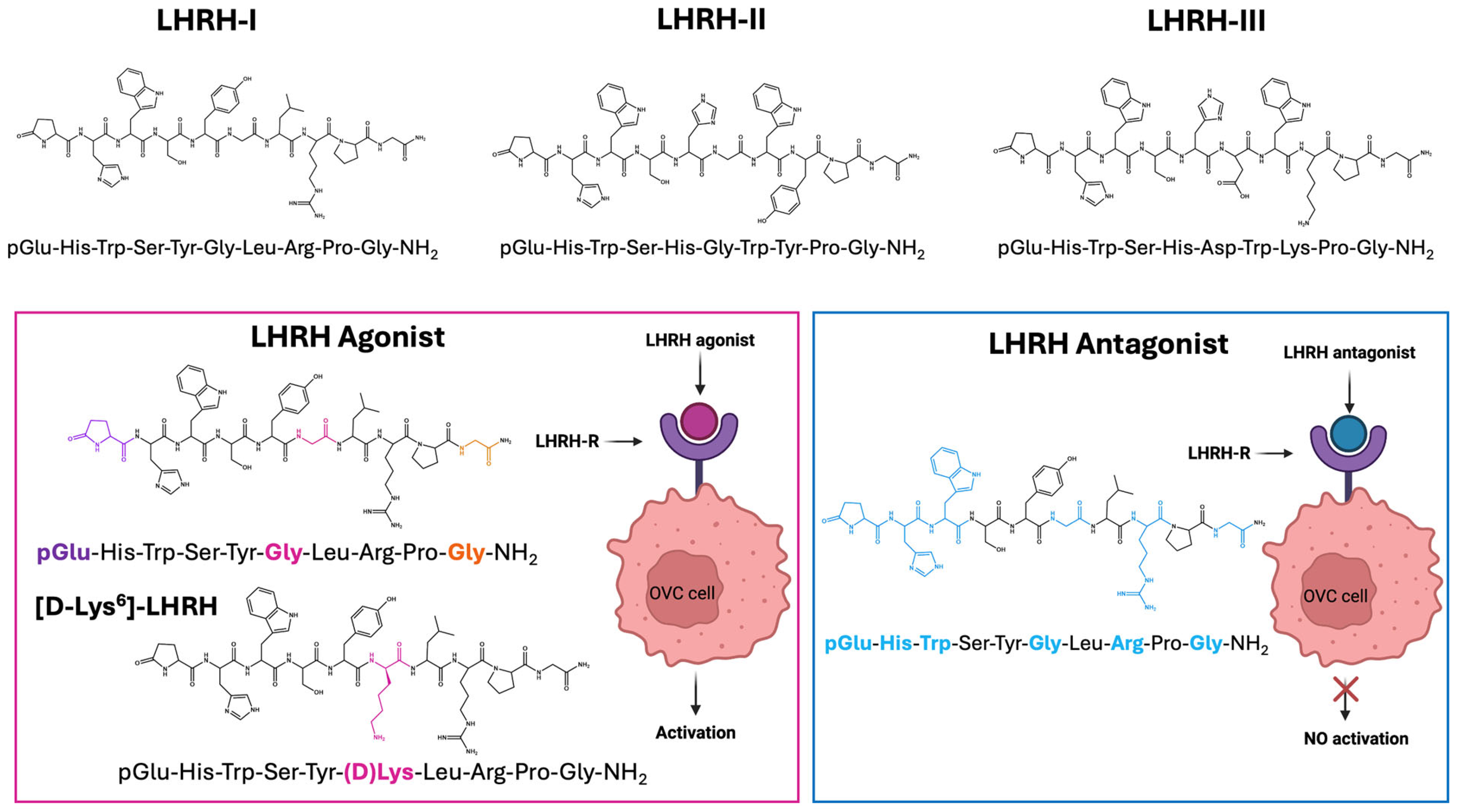

3. LHRH and Its Analogue

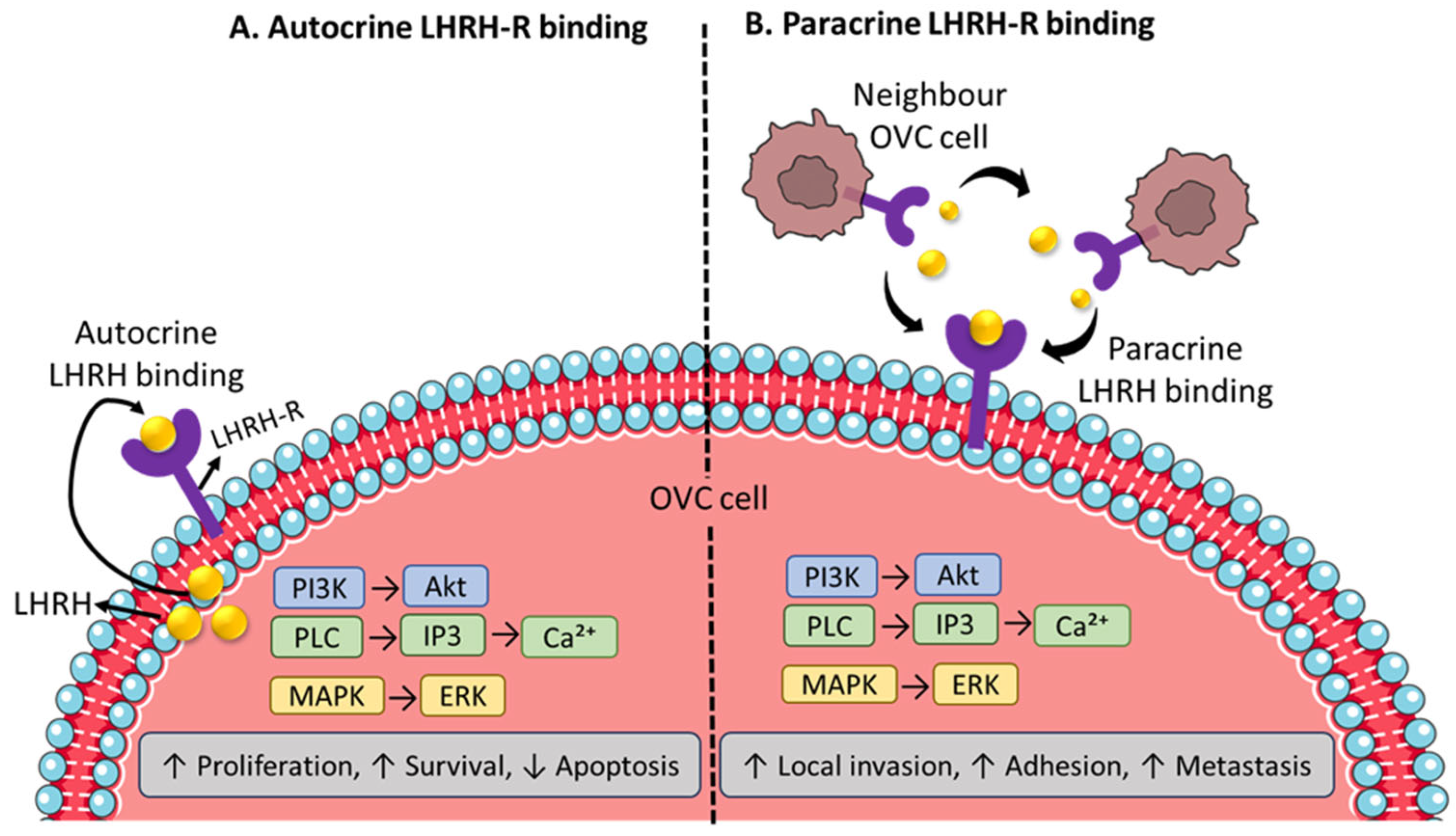

4. LHRH-Receptors and Their Pharmacological Mechanism Overview

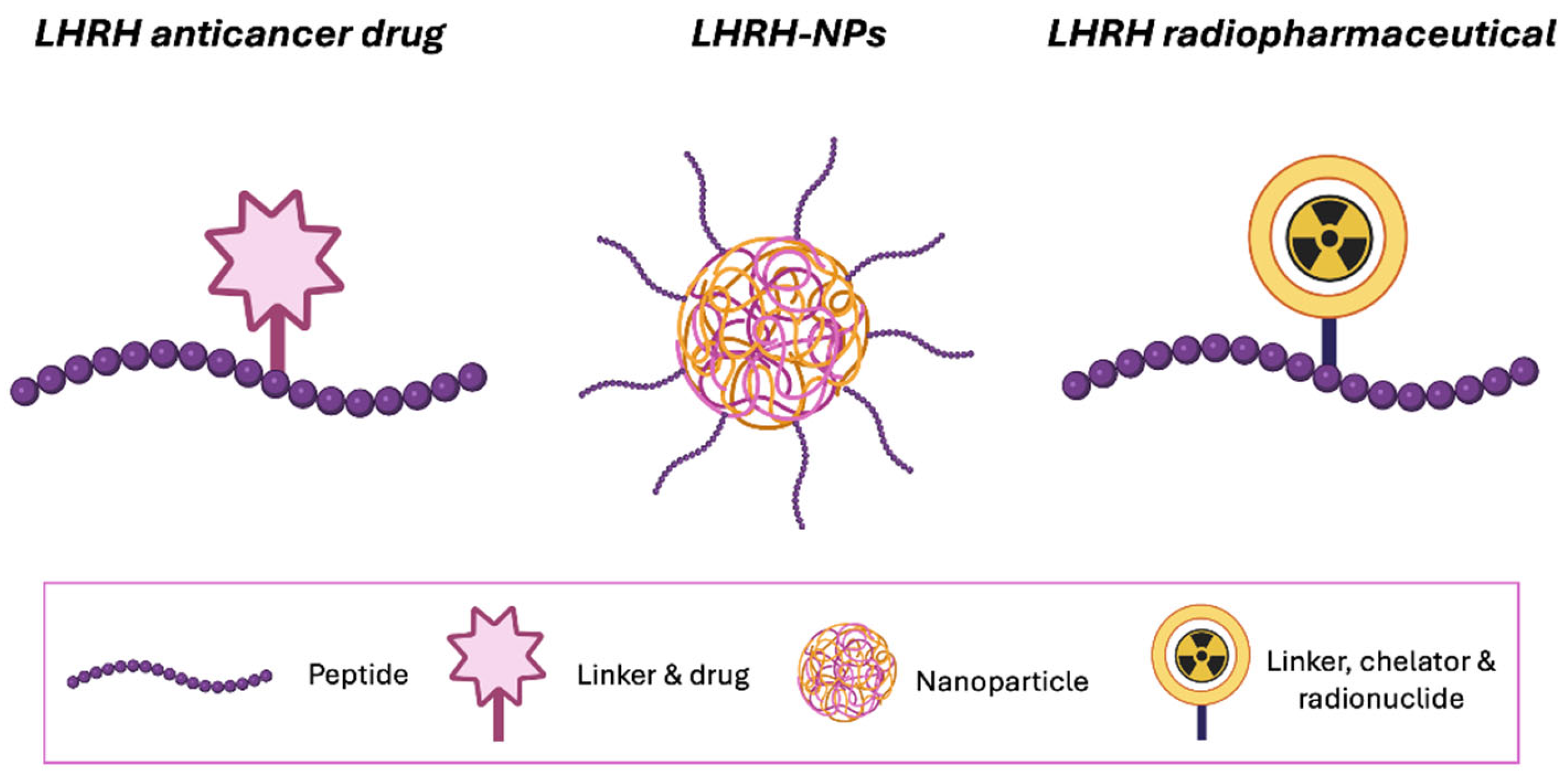

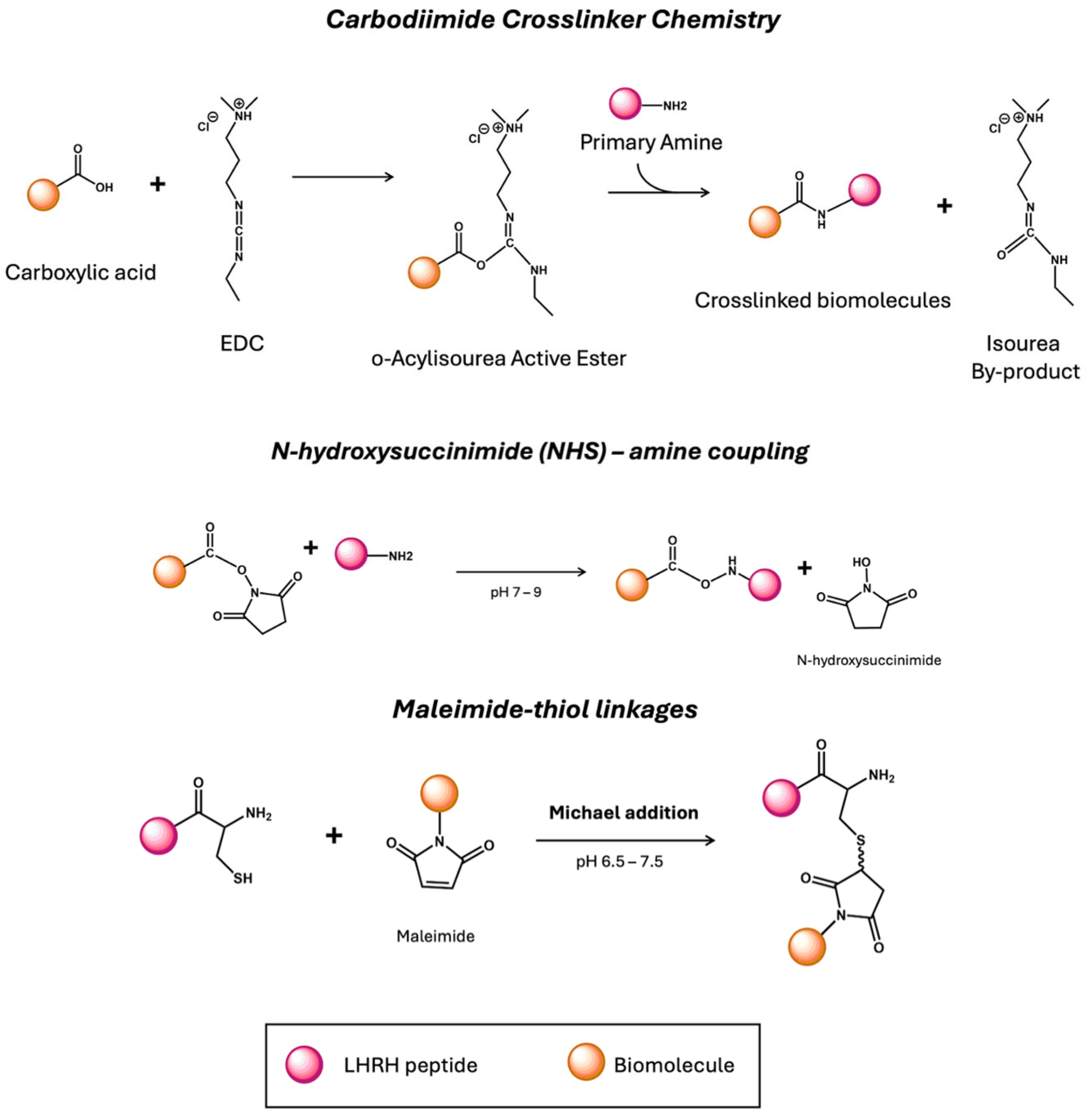

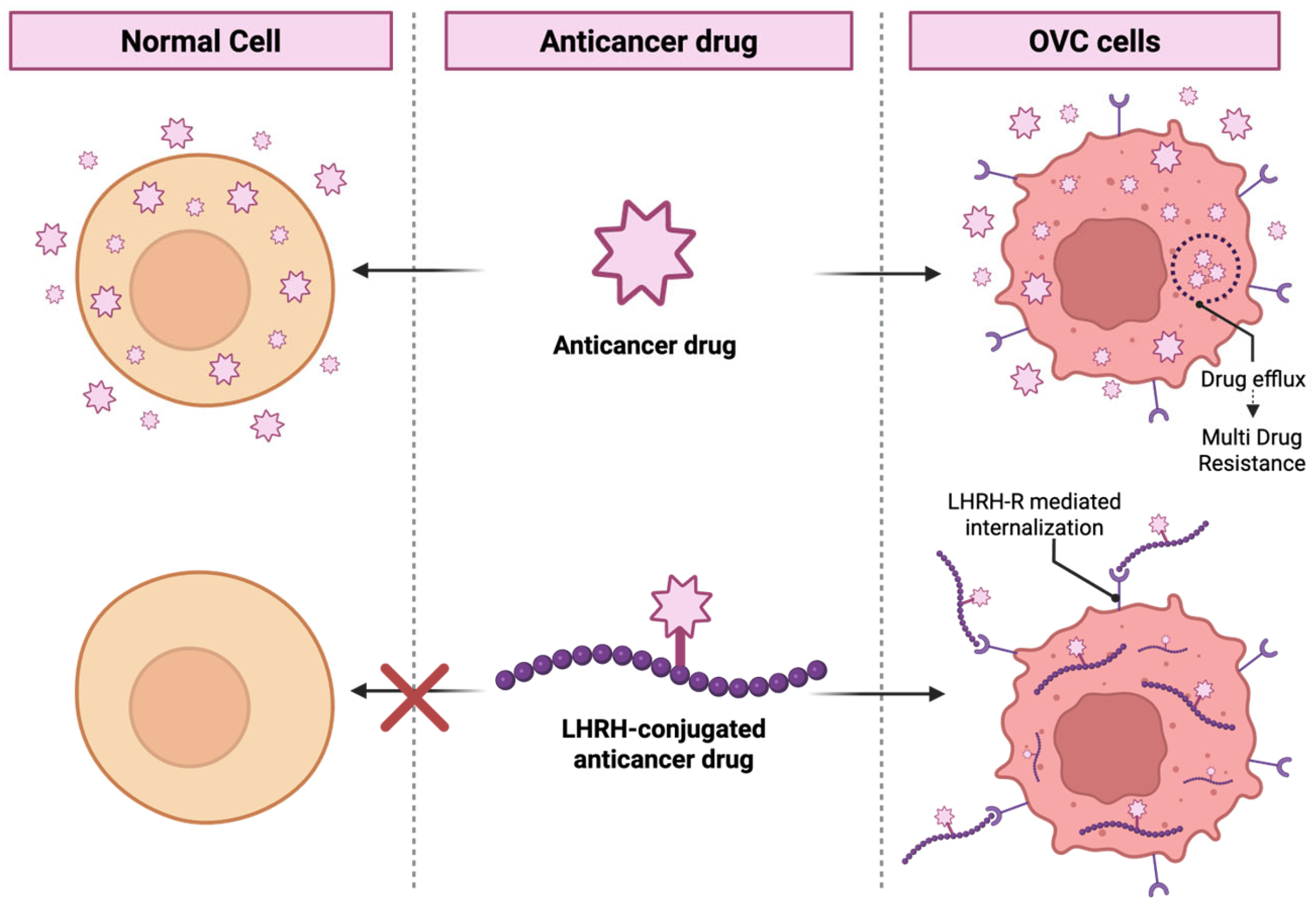

5. LHRH Peptide Engineering for Targeted Delivery

6. LHRH-Conjugated Anticancer Drugs for Targeting Therapy

6.1. Preclinical Studies

6.1.1. Anthracycline Conjugates

6.1.2. Lytic Peptide Conjugates

6.1.3. Other Anticancer Drug Conjugates

| Conjugates /Peptide: Drug | Preclinical Details | Ref. | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| In Vitro Cell Lines (EC50 Ratio) | In Vivo Model (Cell Type) | In Vivo Outcomes (Median Survival or Tumor Size Reduction) | Treatment Group/Dosage/Route of Injection | Key Findings | ||

| AN-152 (D-Lys6-LHRH+ DOX) | EFO-21(1.13 ± 0.06), EFO-27 (1.16 ± 0.16), SKOV-3 (1.57 ± 0.06) | NA | NA | AN-152 or DOX (0.3–100 nM depending on cell line); ±10 μM [D-Trp6]-LHRH preincubation | LHRH-R+ve (EFO-21, EFO-27): Receptor-mediated actions and intranuclear uptake of the AN-152 LHRH-R−ve cells (SKOV-3): AN-152 less active than DOX | [58] |

| AN-152 (D-Lys6-LHRH+ DOX)/1:1 | NA | NIH:OVCAR-3 or SK-OV-3 tumor model | OVCAR-3: AN-152 tumor size reduced to 63–67% of baseline vs. 231–238% in controls. SK-OV-3: No reduction (267% vs. control 275%). | AN-152: 300 or 700 nmol/20 g IV (single dose); DOX equimolar; saline control | The tumor volumes of NIH: OVCAR-3 cancers were reduced significantly 1 week after treatment with AN-152 at both high and low doses | [59] |

| AN-152 (D-Lys6-LHRH+ DOX)/1:1 | EFO-21, NIH: OVCAR-3, SKOV-3 cells EC50: NA | NA | NA | AN-152 or DOX (1–100 nM, 72 h), ± chloroquine (30 µM) or DFP (0.5 mg/mL) | The apoptotic effect of AN-152 is more selective and effective in LHRH-R+ve cells. | [60] |

| AN-152 (D-Lys6-LHRH+ DOX)/1:1 | NA | ES-2 tumor model | 34.5% tumor size reduction with AN-152; DOX 16.3% (NS) | AN-152, DOX, and control/345 nmol/20 g BW/IV | Higher percentages of tumor reduction were found in the AN-152 treatment group than in the DOX. | [61] |

| AN-152 (D-Lys6-LHRH+ DOX)/1:1 | EFO-21, OVCAR-3 cells EC50:NA, % cell viability shown in dose–response curves | NA | NA | 2DG 5–20 mM; AN-152 10−9–10−5 M; GnRH-II antagonist 10−9–10−7 M; 96 h exposure; single and combination treatments | Combining a 2DG with LHRH-R-targeted therapy significantly improves apoptosis and decreases viability in LHRH-R+ve OVC cells. | [62] |

| AN-207 ([D-Lys6]-LHRH + 2-pyrrolino-DOX (AN-201) | ES-2, UCI-107 cells EC50:NA, time- and dose-dependent cytotoxicity shown | NA | NA | ES-2 and UCI-107 cells to AN-207 or AN-201 at 0.1–100 nM (Exp I) or 2–8 nM (Exp II) for 30–240 min. | AN-207 caused cell death in a concentration- and time-dependent manner in ES-2 cells, but not in UCI-107 cells | [63] |

| AN-207 ([D-Lys6]-LHRH + AN-201)/1:1 Blocker: cetrorelix | NA | ES-2 tumor model | AN-207 produced 50–60% tumor inhibition; AN-201 minimally effective; Cetrorelix blocked AN-207 activity | AN-207 (250 nmol/kg IV single or two doses); AN-201 (250 nmol/kg); Cetrorelix 200 µg/mouse SC (blockade) | An unconjugated mixture of drug and peptide was not as effective, whereas AN-207 showed significant inhibition even in a large tumor (400 mm3). | [64] |

| AN-207, AN-215, AN-238 (LHRH/bombesin/somatostatin) linked to AN-201 | NA | UCI-107, OV-1063, ES-2 tumor model | Significant tumor inhibition: 36–75% depending on analogue and model; combinations being the strongest; AN-201 ineffective and toxic | IV doses: 150–200 nmol/kg (single or multiple cycles); combinations at 50% dose each | A combination of LHRH with somatostatin reduced tumor growth by 50–60% in both tumor models, while alone, AnN-201 was not so effective. | [65] |

| EP-100 (GnRH ligand fused to CLIP-71 lytic peptide) | Ovarian cancer cell lines (n = 12); BRCA1/2 mutant and Wild type/EP-100 IC50 = 0.80–2.56 µM | OVCAR5 IP model; HeyA8 IP and SC models | EP-100 reduces tumor weight; EP-100 + Olaparib produces near-complete suppression (0.06 g) | EP-100: 0.02–1 mg/kg IV twice weekly; Olaparib: 50 mg/kg IP daily | The synergistic effect of EP-100 with olaparib and EP-100 sensitizes BRCA wild-type OVC cells to olaparib. | [66] |

| CPT–PEG, CPT–PEG–BH3, CPT–PEG–LHRH/1:1 | A2780 cells IC50 shift: nanomolar to picomolar | NA | NA | CPT-equivalent 3 nM; 48 h exposure; comparison across free CPT and three conjugates | A successful dual-targeting approach that uses BH3 to overcome apoptosis resistance and LHRH for receptor-mediated delivery. | [67] |

| CPT–PEG–LHRH–BH3 and 2×CPT–PEG–2×LHRH–2×BH3 | Primary OVC tumor and malignant ascitic cells | Female athymic mice; SC tumors from primary or ascites-derived cells | Primary tumors: strong regression with 2×CPT–PEG–2×LHRH–2×BH3; Ascites tumors: growth stabilized | CPT-equivalent 10 mg/kg, IP, 6 doses over 3 weeks | Doubling the active components increased the efficacy and reduced off-target toxicity. | [68] |

| 1–3 CPT + 0–3 LHRH copies on PEG | A2780 cells | A2780 tumor model, tumor ~1 cm3 at treatment | 3CPT-PEG-3LHRH produced the strongest tumor reduction vs. all other versions | CPT-equivalent 10 mg/kg single IP injection | 3×CPT-PEG-3×LHRH exhibited higher cellular uptake, the most potent cytotoxicity, and tumor suppression | [69] |

| LHRH-Pt (IV) | A2780 ~9–12 µM; SKOV3 76 µM; SI = 8.2; Highly selective | NA | NA | 0–100 µM (IC50); 10 µM (uptake/DNA); IC70 used for apoptosis/cell cycle | LHRH-Pt (IV) prodrugs to selectively target and kill LHRH-R-overexpressing cancer cells, while posing less toxicity to normal cells. | [70] |

| Con-3/Con-7 LHRH analogues linked to mitoxantrone via disulfide bonds | SKOV-3 Cells EC50:Con-3 = 0.78 nM; Con-7 = 1.8 nM | NA | NA | IV, 0.1 nM–10 µM (proliferation), 1 µM (apoptosis/uptake), cisplatin 30 µg/mL | Con-3 and Con-7 Significantly Inhibit SKOV-3 Cell Proliferation and Induce Apoptosis in a Time-Dependent Manner | [71] |

6.2. Clinical Studies

Summary

6.3. Possible Challenges on LHRH-Targeted Agents

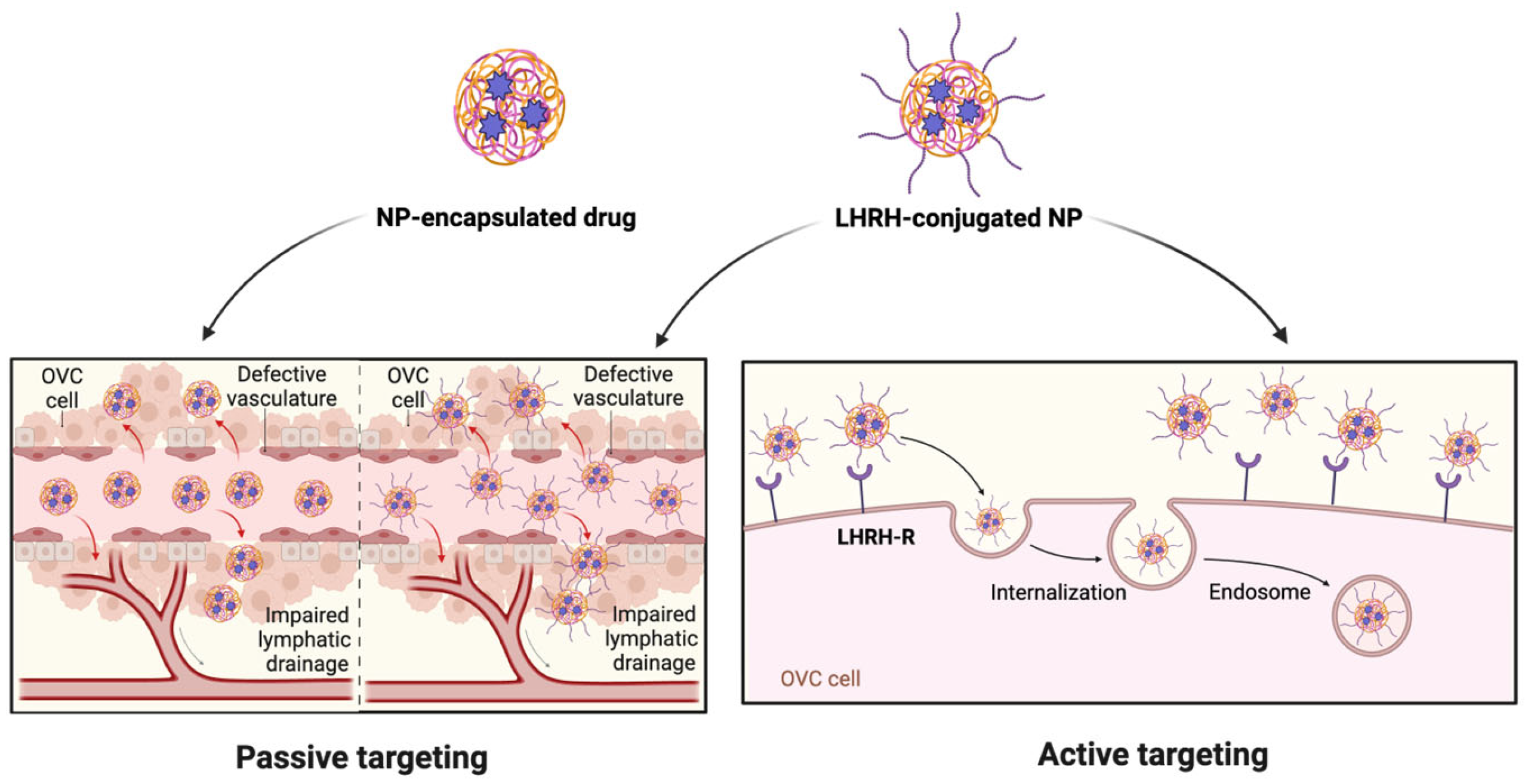

7. LHRH-Conjugated Nanosystem for Receptor-Mediated Cancer Targeting

7.1. LHRH-Functionalized NPs for Drug Delivery

7.2. LHRH-Functionalized NPs for Gene Therapy

7.3. LHRH-Functionalized NPs with Theranostic Applications

7.4. Possible Challenges on LHRH-Conjugated Nanosystem

8. Future Perspectives and Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| NPs | Nanoparticles |

| LHRH | Luteinizing hormone-releasing hormone |

| GnRH | Gonadotropin-releasing hormone |

| LHRH-R | LHRH-Receptors |

| OVC | Ovarian cancer |

| PTX | Paclitaxel |

| LHRHa | LHRH analogues |

| GPCR | G-protein coupled receptor |

| PLC | Phospholipase C |

| EDC | 1-ethyl-3-(3-dimethylaminopropyl)carbodiimide hydrochloride |

| NHS | N-hydroxysuccinimide |

| LHRH-R+ve | LHRH-R-positive |

| LHRH-R−ve | LHRH-R-negative |

| DOX | Doxorubicin |

| AN-152/AEZS-108 | DOX-[D-Lys6]-LHRH |

| 2DG | 2-deoxy-D-glucose |

| AN-201 | 2-pyrrolino-DOX |

| AN-207 | 2-pyrrolino-DOX-[D-Lys6]-LHRH |

| AN-238 | Somatostatin analogues |

| CPT | Camptothecin |

| PEG | Poly(ethylene glycol) |

| SD | Stable disease |

| EPR | Enhanced permeability and retention |

| CHS | Cholesterol hemisuccinate |

| BJOE | Brucea javanica oil |

| PLGA | Poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid |

| CDDP | Cisplatin (cis-diamminedichloroplatinum(II) |

| MTX | Methotrexate |

| siRNA | Small interfering RNA |

| VEGF | Vascular endothelial growth factor |

| PPI | Polypropylenimine |

| PAMAM | Polyamidoamine |

| PEC | Polyelectrolyte complex |

| MNCs | Magnetite-based nanoclusters loaded with cisplatin |

| Pc | Phthalocyanines |

| PDT | Photodynamic therapy |

| PTT | Photothermal therapy |

| CT | Computed tomography |

| MARS SPCCT | Multi-energy spectral photon-counting computed tomography |

| NIR | Near-infrared |

| MRI | Magnetic resonance imaging |

| MNPs | Superparamagnetic iron oxide NPs |

References

- Nayak, P.; Bentivoglio, V.; Varani, M.; Signore, A. Three-Dimensional In Vitro Tumor Spheroid Models for Evaluation of Anticancer Therapy: Recent Updates. Cancers 2023, 15, 4846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, L.; Wang, J.; Li, N.; Cui, J.; Su, Y. Peptides for Diagnosis and Treatment of Ovarian Cancer. Front. Oncol. 2023, 13, 1135523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Global Cancer Observatory (GLOBOCAN). Globocan Factsheets. 2022. Available online: https://gco.iarc.who.int/media/globocan/factsheets/populations/900-world-fact-sheet.pdf (accessed on 20 October 2025).

- Goff, B.A.; Mandel, L.S.; Drescher, C.W.; Urban, N.; Gough, S.; Schurman, K.M.; Patras, J.; Mahony, B.S.; Andersen, M.R. Development of an Ovarian Cancer Symptom Index. Cancer 2007, 109, 221–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, M.; Lee, Y.J.; Seon, K.E.; Kim, S.; Lee, C.; Park, H.; Choi, M.C.; Lee, J.-Y. Morbidity and Mortality Outcomes After Cytoreductive Surgery with Hyperthermic Intraperitoneal Chemotherapy for Treatment of Ovarian Cancer. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 1782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baradács, I.; Teutsch, B.; Vincze, Á.; Hegyi, P.; Szabó, B.; Nyirády, P.; Ács, N.; Melczer, Z.; Bánhidy, F.; Lintner, B. Efficacy and Safety of Combination Therapy with PARP Inhibitors and Anti-Angiogenic Agents in Ovarian Cancer: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 1776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayek, J.; An, A.; Wolf, J.; Lamiman, K.; Kim, M.; Knochenhauer, H.; Goncalves, N.; Alagkiozidis, I. Overall Survival Following Interval Complete Gross Resection of Advanced Ovarian Cancer via Laparoscopy Versus Open Surgery: An Analysis of the National Cancer Database. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 1164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ledermann, J.A.; Raja, F.A.; Fotopoulou, C.; Gonzalez-Martin, A.; Colombo, N.; Sessa, C. Corrections to “Newly Diagnosed and Relapsed Epithelial Ovarian Carcinoma: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for Diagnosis, Treatment and Follow-Up”. Ann. Oncol. 2018, 29, iv259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zafar, A.; Khatoon, S.; Khan, M.J.; Abu, J.; Naeem, A. Advancements and Limitations in Traditional Anti-Cancer Therapies: A Comprehensive Review of Surgery, Chemotherapy, Radiation Therapy, and Hormonal Therapy. Discov. Oncol. 2025, 16, 607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Taratula, O.; Taratula, O.; Schumann, C.; Minko, T. LHRH-Targeted Drug Delivery Systems for Cancer Therapy. Mini-Rev. Med. Chem. 2017, 17, 258–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunjiappan, S.; Panneerselvam, T.; Govindaraj, S.; Parasuraman, P.; Baskararaj, S.; Sankaranarayanan, M.; Arunachalam, S.; Babkiewicz, E.; Jeyakumar, A.; Lakshmanan, M. Design, In Silico Modelling, and Functionality Theory of Novel Folate Receptor Targeted Rutin Encapsulated Folic Acid Conjugated Keratin Nanoparticles for Effective Cancer Treatment. Anticancer Agents Med. Chem. 2020, 19, 1966–1982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, H.; Yang, Z.; Zhang, S.; Cao, S.; Shen, S.; Pang, Z.; Jiang, X. Ligand Modified Nanoparticles Increases Cell Uptake, Alters Endocytosis and Elevates Glioma Distribution and Internalization. Sci. Rep. 2013, 3, 2534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prajapati, A.; Rangra, S.; Patil, R.; Desai, N.; Jyothi, V.G.S.S.; Salave, S.; Amate, P.; Benival, D.; Kommineni, N. Receptor-Targeted Nanomedicine for Cancer Therapy. Receptors 2024, 3, 323–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Worm, D.J.; Els-Heindl, S.; Beck-Sickinger, A.G. Targeting of Peptide-binding Receptors on Cancer Cells with Peptide-drug Conjugates. Pept. Sci. 2020, 112, e24171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varani, M.; Campagna, G.; Bentivoglio, V.; Serafinelli, M.; Martini, M.L.; Galli, F.; Signore, A. Synthesis and Biodistribution of 99mTc-Labeled PLGA Nanoparticles by Microfluidic Technique. Pharmaceutics 2021, 13, 1769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lastoria, S.; Rodari, M.; Sansovini, M.; Baldari, S.; D’Agostini, A.; Cervino, A.R.; Filice, A.; Salgarello, M.; Perotti, G.; Nieri, A.; et al. Lutetium [177Lu]-DOTA-TATE in Gastroenteropancreatic-Neuroendocrine Tumours: Rationale, Design and Baseline Characteristics of the Italian Prospective Observational (REAL-LU) Study. Eur. J. Nucl. Med. Mol. Imaging 2024, 51, 3417–3427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varani, M.; Bentivoglio, V.; Campagna, G.; Nayak, P.; Lauri, C. Evaluation of a New Avidin Chase in Murine Models Pre-Treated with Two 111In Labelled Biotin Analogues. Int. J. Appl. Biol. Pharm. 2024, 15, 17–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giorgio, A.; Varani, M.; Lauri, C.; Bentivoglio, V.; Nayak, P. Radiolabeled LHRH and FSH Analogues as Cancer Theranostic Agents: A Systematic Review. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 7811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bentivoglio, V.; D’Ippolito, E.; Nayak, P.; Giorgio, A.; Lauri, C. Bispecific Radioligands (BRLs): Two Is Better Than One. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 5628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunjiappan, S.; Pavadai, P.; Vellaichamy, S.; Ram Kumar Pandian, S.; Ravishankar, V.; Palanisamy, P.; Govindaraj, S.; Srinivasan, G.; Premanand, A.; Sankaranarayanan, M.; et al. Surface Receptor-mediated Targeted Drug Delivery Systems for Enhanced Cancer Treatment: A State-of-the-art Review. Drug Dev. Res. 2021, 82, 309–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lappano, R.; Maggiolini, M. GPCRs and cancer. Acta Pharmacol. Sin. 2012, 33, 351–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obayemi, J.D.; Salifu, A.A.; Eluu, S.C.; Uzonwanne, V.O.; Jusu, S.M.; Nwazojie, C.C.; Onyekanne, C.E.; Ojelabi, O.; Payne, L.; Moore, C.M.; et al. LHRH-Conjugated Drugs as Targeted Therapeutic Agents for the Specific Targeting and Localized Treatment of Triple Negative Breast Cancer. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 8212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coelingh Bennink, H.J.T.; Roos, E.P.M.; van Moorselaar, R.J.A.; van Melick, H.H.E.; Somford, D.M.; Roeleveld, T.A.; de Haan, T.D.; Reisman, Y.; Schultz, I.J.; Krijgh, J.; et al. Estetrol Inhibits the Prostate Cancer Tumor Stimulators FSH and IGF-1. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 5996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Q.; Madden, N.E.; Wong, A.S.; Chow, B.K.; Lee, L.T. The Role of Endocrine G Protein-Coupled Receptors in Ovarian Cancer Progression. Front. Endocrinol. 2017, 8, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McArdle, C.; Franklin, J.; Green, L.; Hislop, J. Signalling, Cycling and Desensitisation of Gonadotrophin-Releasing Hormone Receptors. J. Endocrinol. 2002, 173, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krsmanovic, L.Z.; Martinez-Fuentes, A.J.; Arora, K.K.; Mores, N.; Tomić, M.; Stojilkovic, S.S.; Catt, K.J. Local Regulation of Gonadotroph Function by Pituitary Gonadotropin-Releasing Hormone. Endocrinology 2000, 141, 1187–1195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gault, P.M.; Maudsley, S.; Lincoln, G.A. Evidence That Gonadotropin-Releasing Hormone II Is Not a Physiological Regulator of Gonadotropin Secretion in Mammals. J. Neuroendocrinol. 2003, 15, 831–839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassanein, E.M.; Szelényi, Z.; Szenci, O. Gonadotropin-Releasing Hormone (GnRH) and Its Agonists in Bovine Reproduction I: Structure, Biosynthesis, Physiological Effects, and Its Role in Estrous Synchronization. Animals 2024, 14, 1473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizvi, S.F.A.; Zhang, H.; Fang, Q. Engineering Peptide Drug Therapeutics through Chemical Conjugation and Implication in Clinics. Med. Res. Rev. 2024, 44, 2420–2471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maggi, R. Physiology of Gonadotropin-Releasing Hormone (Gnrh): Beyond the Control of Reproductive Functions. MOJ Anat. Physiol. 2016, 2, 150–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Y.; Zhang, L.; Song, C. PEGylated Liposomes Modified with LHRH Analogs for Tumor Targeting. J. Control. Release 2011, 152, e29–e31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schally, A. V Luteinizing Hormone-Releasing Hormone Analogs: Their Impact on the Control of Tumorigenesis. Peptides 1999, 20, 1247–1262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, X.; Shen, B.; Chen, Q.; Zhang, X.; Ye, Y.; Wang, F.; Zhang, X. Antitumor Effects of Cecropin B-LHRH’ on Drug-Resistant Ovarian and Endometrial Cancer Cells. BMC Cancer 2016, 16, 251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chatzaki, E.; Bax, C.M.; Eidne, K.A.; Anderson, L.; Grudzinskas, J.G.; Gallagher, C.J. The Expression of Gonadotropin-Releasing Hormone and Its Receptor in Endometrial Cancer, and Its Relevance as an Autocrine Growth Factor. Cancer Res. 1996, 56, 2059–2065. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Shore, N.D.; Abrahamsson, P.-A.; Anderson, J.; Crawford, E.D.; Lange, P. New Considerations for ADT in Advanced Prostate Cancer and the Emerging Role of GnRH Antagonists. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis. 2013, 16, 7–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cook, T.; Sheridan, W.P. Development of GnRH Antagonists for Prostate Cancer: New Approaches to Treatment. Oncologist 2000, 5, 162–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, S.K.; Choi, K.-C.; Cheng, K.W.; Nathwani, P.S.; Auersperg, N.; Leung, P.C.K. Role of Gonadotropin-Releasing Hormone as an Autocrine Growth Factor in Human Ovarian Surface Epithelium1. Endocrinology 2000, 141, 72–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Völker, P.; Gründker, C.; Schmidt, O.; Schulz, K.D.; Emons, G. Expression of receptors for luteinizing hormone-releasing hormone in human ovarian and endometrial cancers: Frequency, autoregulation, and correlation with direct antiproliferative activity of luteinizing hormone-releasing hormone analogues. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2002, 186, 171–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gründker, C.; Emons, G. Role of Gonadotropin-Releasing Hormone (GnRH) in Ovarian Cancer. Cells 2021, 10, 437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarke, I.J. Control of GnRH Secretion: One Step Back. Front. Neuroendocrinol. 2011, 32, 367–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Limonta, P.; Marelli, M.M.; Moretti, R.M. LHRH Analogues as Anticancer Agents: Pituitary and Extrapituitary Sites of Action. Expert Opin. Investig. Drugs 2001, 10, 709–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagy, A.; Schally, A.V. Targeting of Cytotoxic Luteinizing Hormone-Releasing Hormone Analogs to Breast, Ovarian, Endometrial, and Prostate Cancers. Biol. Reprod. 2005, 73, 851–859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, C.K.; Leung, P.C.K. Molecular Biology of Gonadotropin-Releasing Hormone (GnRH)-I, GnRH-II, and Their Receptors in Humans. Endocr. Rev. 2005, 26, 283–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jaszberenyi, M.; Schally, A.V.; Block, N.L.; Nadji, M.; Vidaurre, I.; Szalontay, L.; Rick, F.G. Inhibition of U-87 MG Glioblastoma by AN-152 (AEZS-108), a Targeted Cytotoxic Analog of Luteinizing Hormone-Releasing Hormone. Oncotarget 2013, 4, 422–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sion-Vardi, Ν.; Kaneti, J.; Segal-Abramson, T.; Giat, J.; Levy, J.; Sharoni, Y. Gonadotropin-Releasing Hormone Specific Binding Sites in Normal and Malignant Renal Tissue. J. Urol. 1992, 148, 1568–1570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pati, D.; Habibi, H.R. Inhibition of Human Hepatocarcinoma Cell Proliferation by Mammalian and Fish Gonadotropin-Releasing Hormones. Endocrinology 1995, 136, 75–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moretti, R.M.; Montagnani Marelli, M.; Van Groeninghen, J.C.; Limonta, P. Locally Expressed LHRH Receptors Mediate the Oncostatic and Antimetastatic Activity of LHRH Agonists on Melanoma Cells. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2002, 87, 3791–3797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friess, H.; Büchler, M.; Kiesel, L.; Krüger, M.; Beger, H.G. LH-RH Receptors in the Human Pancreas. Basis for Antihormonal Treatment in Ductal Carcinoma of the Pancreas. Int. J. Pancreatol. 1991, 10, 151–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, J.; Kaake, M.; Low, P.S. Small Molecule Targeted NIR Dye Conjugate for Imaging LHRH Receptor Positive Cancers. Oncotarget 2019, 10, 152–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, Z.; Shepherd, J.H.; Shepherd, D.V.; Ghose, S.; Kew, S.J.; Cameron, R.E.; Best, S.M.; Brooks, R.A.; Wardale, J.; Rushton, N. Effect of 1-Ethyl-3-(3-Dimethylaminopropyl) Carbodiimide and N-Hydroxysuccinimide Concentrations on the Mechanical and Biological Characteristics of Cross-Linked Collagen Fibres for Tendon Repair. Regen. Biomater. 2015, 2, 77–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, R.; Finan, B.; Mayer, J.P.; DiMarchi, R.D. Peptide Conjugates with Small Molecules Designed to Enhance Efficacy and Safety. Molecules 2019, 24, 1855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bentivoglio, V.; Nayak, P.; Varani, M.; Lauri, C.; Signore, A. Methods for Radiolabeling Nanoparticles (Part 3): Therapeutic Use. Biomolecules 2023, 13, 1241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bentivoglio, V.; Varani, M.; Lauri, C.; Ranieri, D.; Signore, A. Methods for Radiolabelling Nanoparticles: PET Use (Part 2). Biomolecules 2022, 12, 1517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Varani, M.; Bentivoglio, V.; Lauri, C.; Ranieri, D.; Signore, A. Methods for Radiolabelling Nanoparticles: SPECT Use (Part 1). Biomolecules 2022, 12, 1522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jadhav, K.; Abhang, A.; Kole, E.B.; Gadade, D.; Dusane, A.; Iyer, A.; Sharma, A.; Rout, S.K.; Gholap, A.D.; Naik, J.; et al. Peptide–Drug Conjugates as Next-Generation Therapeutics: Exploring the Potential and Clinical Progress. Bioengineering 2025, 12, 481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bajusz, S.; Janaky, T.; Csernus, V.J.; Bokser, L.; Fekete, M.; Srkalovic, G.; Redding, T.W.; Schally, A. V Highly Potent Metallopeptide Analogues of Luteinizing Hormone-Releasing Hormone. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1989, 86, 6313–6317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagy, A.; Schally, A.V.; Armatis, P.; Szepeshazi, K.; Halmos, G.; Kovacs, M.; Zarandi, M.; Groot, K.; Miyazaki, M.; Jungwirth, A.; et al. Cytotoxic Analogs of Luteinizing Hormone-Releasing Hormone Containing Doxorubicin or 2-Pyrrolinodoxorubicin, a Derivative 500-1000 Times More Potent. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1996, 93, 7269–7273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westphalen, S.; Kotulla, G.; Kaiser, F.; Krauss, W.; Werning, G.; Elsasser, H.P.; Nagy, A.; Schulz, K.D.; Grundker, C.; Schally, A.V.; et al. Receptor Mediated Antiproliferative Effects of the Cytotoxic LHRH Agonist AN-152 in Human Ovarian and Endometrial Cancer Cell Lines. Int. J. Oncol. 2000, 17, 1063–1072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gründker, C.; Völker, P.; Griesinger, F.; Ramaswamy, A.; Nagy, A.; Schally, A.V.; Emons, G. Antitumor Effects of the Cytotoxic Luteinizing Hormone–Releasing Hormone Analog AN-152 on Human Endometrial and Ovarian Cancers Xenografted into Nude Mice. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2002, 187, 528–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Günthert, A.R.; Gründker, C.; Bongertz, T.; Schlott, T.; Nagy, A.; Schally, A.V.; Emons, G. Internalization of Cytotoxic Analog AN-152 of Luteinizing Hormone-Releasing Hormone Induces Apoptosis in Human Endometrial and Ovarian Cancer Cell Lines Independent of Multidrug Resistance-1 (MDR-1) System. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2004, 191, 1164–1172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arencibia, J.; Schally, A.; Krupa, M.; Bajo, A.; Nagy, A.; Szepeshazi, K.; Plonowski, A. Targeting of Doxorubicin to ES-2 Human Ovarian Cancers in Nude Mice by Linking to an Analog of Luteinizing Hormone-Releasing Hormone Improves Its Effectiveness. Int. J. Oncol. 2001, 19, 571–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reutter, M.; Emons, G.; Gründker, C. Starving Tumors: Inhibition of Glycolysis Reduces Viability of Human Endometrial and Ovarian Cancer Cells and Enhances Antitumor Efficacy of GnRH Receptor-Targeted Therapies. Int. J. Gynecol. Cancer 2013, 23, 34–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arencibia, J.M.; Schally, A.V.; Halmos, G.; Nagy, A.; Kiaris, H. In Vitro Targeting of a Cytotoxic Analog of Luteinizing Hormone-Releasing Hormone AN-207 to ES-2 Human Ovarian Cancer Cells as Demonstrated by Microsatellite Analyses. Anticancer Drugs 2001, 12, 71–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arencibia, J.M.; Bajo, A.M.; Schally, A.V.; Krupa, M.; Chatzistamou, I.; Nagy, A. Effective Treatment of Experimental ES-2 Human Ovarian Cancers with a Cytotoxic Analog of Luteinizing Hormone-Releasing Hormone AN-207. Anticancer Drugs 2002, 13, 949–956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buchholz, S.; Keller, G.; Schally, A.V.; Halmos, G.; Hohla, F.; Heinrich, E.; Koester, F.; Baker, B.; Engel, J.B. Therapy of Ovarian Cancers with Targeted Cytotoxic Analogs of Bombesin, Somatostatin, and Luteinizing Hormone-Releasing Hormone and Their Combinations. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2006, 103, 10403–10407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, S.; Pradeep, S.; Villar-Prados, A.; Wen, Y.; Bayraktar, E.; Mangala, L.S.; Kim, M.S.; Wu, S.Y.; Hu, W.; Rodriguez-Aguayo, C.; et al. GnRH-R–Targeted Lytic Peptide Sensitizes BRCA Wild-Type Ovarian Cancer to PARP Inhibition. Mol. Cancer Ther. 2019, 18, 969–979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dharap, S. Molecular Targeting of Drug Delivery Systems to Ovarian Cancer by BH3 and LHRH Peptides. J. Control. Release 2003, 91, 61–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandna, P.; Khandare, J.J.; Ber, E.; Rodriguez-Rodriguez, L.; Minko, T. Multifunctional Tumor-Targeted Polymer-Peptide-Drug Delivery System for Treatment of Primary and Metastatic Cancers. Pharm. Res. 2010, 27, 2296–2306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khandare, J.J.; Chandna, P.; Wang, Y.; Pozharov, V.P.; Minko, T. Novel Polymeric Prodrug with Multivalent Components for Cancer Therapy. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2006, 317, 929–937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, H.; Xu, Z.; Li, C.; Tse, M.-K.; Tong, Z.; Zhu, G. Synthesis and Cytotoxic Study of a Platinum(IV) Anticancer Prodrug with Selectivity toward Luteinizing Hormone-Releasing Hormone (LHRH) Receptor-Positive Cancer Cells. Inorg. Chem. 2019, 58, 11076–11084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markatos, C.; Biniari, G.; Chepurny, O.G.; Karageorgos, V.; Tsakalakis, N.; Komontachakis, G.; Vlata, Z.; Venihaki, M.; Holz, G.G.; Tselios, T.; et al. Cytotoxic Activity of Novel GnRH Analogs Conjugated with Mitoxantrone in Ovarian Cancer Cells. Molecules 2024, 29, 4127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verschraegen, C.F.; Westphalen, S.; Hu, W.; Loyer, E.; Kudelka, A.; Völker, P.; Kavanagh, J.; Steger, M.; Schulz, K.-D.; Emons, G. Phase II Study of Cetrorelix, a Luteinizing Hormone-Releasing Hormone Antagonist in Patients with Platinum-Resistant Ovarian Cancer. Gynecol. Oncol. 2003, 90, 552–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emons, G.; Gorchev, G.; Sehouli, J.; Wimberger, P.; Stähle, A.; Hanker, L.; Hilpert, F.; Sindermann, H.; Gründker, C.; Harter, P. Efficacy and Safety of AEZS-108 (INN: Zoptarelin Doxorubicin Acetate) an LHRH Agonist Linked to Doxorubicin in Women with Platinum Refractory or Resistant Ovarian Cancer Expressing LHRH Receptors: A Multicenter Phase II Trial of the Ago-Study Group (AGO GYN 5). Gynecol. Oncol. 2014, 133, 427–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Curtis, K.K.; Sarantopoulos, J.; Northfelt, D.W.; Weiss, G.J.; Barnhart, K.M.; Whisnant, J.K.; Leuschner, C.; Alila, H.; Borad, M.J.; Ramanathan, R.K. Novel LHRH-Receptor-Targeted Cytolytic Peptide, EP-100: First-in-Human Phase I Study in Patients with Advanced LHRH-Receptor-Expressing Solid Tumors. Cancer Chemother. Pharmacol. 2014, 73, 931–941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chelariu-Raicu, A.; Nick, A.; Urban, R.; Gordinier, M.; Leuschner, C.; Bavisotto, L.; Molin, G.Z.D.; Whisnant, J.K.; Coleman, R.L. A Multicenter Open-Label Randomized Phase II Trial of Paclitaxel plus EP-100, a Novel LHRH Receptor-Targeted, Membrane-Disrupting Peptide, versus Paclitaxel Alone for Refractory or Recurrent Ovarian Cancer. Gynecol. Oncol. 2021, 160, 418–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miller, D.S.; Scambia, G.; Bondarenko, I.; Westermann, A.M.; Oaknin, A.; Oza, A.M.; Lisyanskaya, A.S.; Vergote, I.; Wenham, R.M.; Temkin, S.M.; et al. ZoptEC: Phase III randomized controlled study comparing zoptarelin with doxorubicin as second-line therapy for locally advanced, recurrent, or metastatic endometrial cancer (NCT01767155). Int. J. Gynecol. Cancer 2018, 28, 1319–1327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- C, L. Targeted Oncolytic Peptide for Treatment of Ovarian Cancers. Int. J. Cancer Res. Mol. Mech. 2017, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, M.; Huang, W.; Yang, N.; Liu, Y. Learn from Antibody–Drug Conjugates: Consideration in the Future Construction of Peptide-Drug Conjugates for Cancer Therapy. Exp. Hematol. Oncol. 2022, 11, 93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoppenz, P.; Els-Heindl, S.; Beck-Sickinger, A.G. Peptide-Drug Conjugates and Their Targets in Advanced Cancer Therapies. Front. Chem. 2020, 8, 571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maggi, R.; Cariboni, A.M.; Marelli, M.M.; Moretti, R.M.; Andre, V.; Marzagalli, M.; Limonta, P. GnRH and GnRH receptors in the pathophysiology of the human female reproductive system. Hum. Reprod. Update 2016, 22, 358–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vankadara, S.; Ke, Z.; Wang, S.; Foo, S.Y.; Gunaratne, J.; Lee, M.A.; Koh, X.; Chia, C.S.B. Cytotoxic Activity and Cell Specificity of a Novel LHRH Peptide Drug Conjugate, D-Cys6-LHRH Vedotin, against Ovarian Cancer Cell Lines. Chem. Biol. Drug Des. 2024, 103, e14516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Ding, H.; Zhang, F.; Xu, Y.; Liang, W.; Huang, L. New Trends in Diagnosing and Treating Ovarian Cancer Using Nanotechnology. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2023, 11, 1160985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pan, Q.; Tian, J.; Zhu, H.; Hong, L.; Mao, Z.; Oliveira, J.M.; Reis, R.L.; Li, X. Tumor-Targeting Polycaprolactone Nanoparticles with Codelivery of Paclitaxel and IR780 for Combinational Therapy of Drug-Resistant Ovarian Cancer. ACS Biomater. Sci. Eng. 2020, 6, 2175–2185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qin, Y.; Song, Q.-G.; Zhang, Z.-R.; Liu, J.; Fu, Y.; He, Q.; Liu, J. Ovarian Tumor Targeting of Docetaxel-Loaded Liposomes Mediated by Luteinizing Hormone-Releasing Hormone Analogues. Arzneimittelforschung 2008, 58, 529–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuan, W.-M.; Song, Q.-G.; Zhang, Z.-R.; Fu, Y.; Liu, J.; He, Q. LHRHa Aided Liposomes Targeting to Human Ovarian Tumor Cells: Preparation and Cellular Uptake. Pharmazie 2008, 63, 434–438. [Google Scholar]

- He, Y.; Zhang, L.; Song, C. Luteinizing Hormone-Releasing Hormone Receptor-Mediated Delivery of Mitoxantrone Using LHRH Analogs Modified with PEGylated Liposomes. Int. J. Nanomed. 2010, 5, 697–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, H.; Liu, X.; Sun, J.; Zhu, S.; Zhu, Y.; Chang, S. Enhanced Therapeutic Efficacy of LHRHa-Targeted Brucea Javanica Oil Liposomes for Ovarian Cancer. BMC Cancer 2016, 16, 831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nukolova, N.V.; Oberoi, H.S.; Zhao, Y.; Chekhonin, V.P.; Kabanov, A.V.; Bronich, T.K. LHRH-Targeted Nanogels as a Delivery System for Cisplatin to Ovarian Cancer. Mol. Pharm. 2013, 10, 3913–3921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.; Yan, S.; Xiao, F.; Xue, M. PLGA Nanoparticles Delivering CPT-11 Combined with Focused Ultrasound Inhibit Platinum Resistant Ovarian Cancer. Transl. Cancer Res. 2021, 10, 1732–1743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taheri, A.; Dinarvand, R.; Atyabi, F.; Ahadi, F.; Nouri, F.S.; Ghahremani, M.H.; Ostad, S.N.; Borougeni, A.T.; Mansoori, P. Enhanced Anti-Tumoral Activity of Methotrexate-Human Serum Albumin Conjugated Nanoparticles by Targeting with Luteinizing Hormone-Releasing Hormone (LHRH) Peptide. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2011, 12, 4591–4608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, N.; Zhou, X.; Ma, N.; Zhang, J.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, X.; Li, A. Integrin Avβ3 and LHRH Receptor Double Directed Nano-Analogue Effective Against Ovarian Cancer in Mice Model. Int. J. Nanomed. 2024, 19, 3071–3086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Hu, X.; Yue, J.; Zhang, W.; Cai, L.; Xie, Z.; Huang, Y.; Jing, X. Luteinizing-Hormone-Releasing-Hormone-Containing Biodegradable Polymer Micelles for Enhanced Intracellular Drug Delivery. J. Mater. Chem. B 2013, 1, 293–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pu, C.; Chang, S.; Sun, J.; Zhu, S.; Liu, H.; Zhu, Y.; Wang, Z.; Xu, R.X. Ultrasound-Mediated Destruction of LHRHa-Targeted and Paclitaxel-Loaded Lipid Microbubbles for the Treatment of Intraperitoneal Ovarian Cancer Xenografts. Mol. Pharm. 2014, 11, 49–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, C.; Yuan, Z.; Kohler, N.; Kim, J.; Chung, M.A.; Sun, S. FePt Nanoparticles as an Fe Reservoir for Controlled Fe Release and Tumor Inhibition. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009, 131, 15346–15351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, Y.; Chen, S.; Li, W.; Wang, H.; Xiao, K.; Wu, L.; Li, Y.; Li, H.; Li, H.; Zhu, Y. An Experimental Study of Ovarian Cancer Imaging and Therapy by Paclitaxel-Loaded Phase-Transformation Lipid Nanoparticles Combined with Low-Intensity Focused Ultrasound. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2018, 504, 203–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, P.; Duraisamy, K.; Raitmayr, C.; Sharma, K.S.; Korzun, T.; Singh, K.; Moses, A.S.; Yamada, K.; Grigoriev, V.; Demessie, A.A.; et al. Precision-Engineered Cobalt-Doped Iron Oxide Nanoparticles: From Octahedron Seeds to Cubical Bipyramids for Enhanced Magnetic Hyperthermia. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2025, 35, 2414719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.H.; Jeong, J.H.; Lee, S.H.; Kim, S.W.; Park, T.G. LHRH Receptor-Mediated Delivery of SiRNA Using Polyelectrolyte Complex Micelles Self-Assembled from SiRNA-PEG-LHRH Conjugate and PEI. Bioconjug Chem. 2008, 19, 2156–2162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, V.; Taratula, O.; Garbuzenko, O.B.; Taratula, O.R.; Rodriguez-Rodriguez, L.; Minko, T. Targeted Nanomedicine for Suppression of CD44 and Simultaneous Cell Death Induction in Ovarian Cancer: An Optimal Delivery of SiRNA and Anticancer Drug. Clin. Cancer Res. 2013, 19, 6193–6204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schumann, C.; Taratula, O.; Khalimonchuk, O.; Palmer, A.L.; Cronk, L.M.; Jones, C.V.; Escalante, C.A.; Taratula, O. ROS-Induced Nanotherapeutic Approach for Ovarian Cancer Treatment Based on the Combinatorial Effect of Photodynamic Therapy and DJ-1 Gene Suppression. Nanomedicine 2015, 11, 1961–1970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schumann, C.; Chan, S.; Khalimonchuk, O.; Khal, S.; Moskal, V.; Shah, V.; Alani, A.W.G.; Taratula, O.; Taratula, O. Mechanistic Nanotherapeutic Approach Based on SiRNA-Mediated DJ-1 Protein Suppression for Platinum-Resistant Ovarian Cancer. Mol. Pharm. 2016, 13, 2070–2083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schumann, C.; Chan, S.; Millar, J.A.; Bortnyak, Y.; Carey, K.; Fedchyk, A.; Wong, L.; Korzun, T.; Moses, A.S.; Lorenz, A.; et al. Intraperitoneal Nanotherapy for Metastatic Ovarian Cancer Based on SiRNA-Mediated Suppression of DJ-1 Protein Combined with a Low Dose of Cisplatin. Nanomedicine 2018, 14, 1395–1405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patil, M.L.; Zhang, M.; Taratula, O.; Garbuzenko, O.B.; He, H.; Minko, T. Internally Cationic Polyamidoamine PAMAM-OH Dendrimers for SiRNA Delivery: Effect of the Degree of Quaternization and Cancer Targeting. Biomacromolecules 2009, 10, 258–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, C.; Ding, B.; Zhang, X.; Deng, X.; Deng, K.; Cheng, Z.; Xing, B.; Jin, D.; Ma, P.; Lin, J. Targeted Iron Nanoparticles with Platinum-(IV) Prodrugs and Anti-EZH2 SiRNA Show Great Synergy in Combating Drug Resistance in Vitro and in Vivo. Biomaterials 2018, 155, 112–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, S.; Guo, J.; Sun, J.; Zhu, S.; Yan, Y.; Zhu, Y.; Li, M.; Wang, Z.; Xu, R.X. Targeted Microbubbles for Ultrasound Mediated Gene Transfection and Apoptosis Induction in Ovarian Cancer Cells. Ultrason. Sonochem 2013, 20, 171–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, M.; Liu, Y.; Hsieh, R.S.; Wang, N.; Tai, W.; Joo, K.-I.; Wang, P.; Gu, Z.; Tang, Y. Clickable Protein Nanocapsules for Targeted Delivery of Recombinant P53 Protein. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014, 136, 15319–15325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alatise, K.L.; Samec, T.; Coffin, C.; Gilmore, S.; Hazelton, A.; Xia, R.; Jones, C.; Alexander-Bryant, A. Multifunctional Tandem Peptide Mediates Targeted SiRNA Delivery to Ovarian Cancer Cells. ACS Appl. Bio Mater. 2025, 8, 4612–4620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garbuzenko, O.B.; Sapiezynski, J.; Girda, E.; Rodriguez-Rodriguez, L.; Minko, T. Personalized Versus Precision Nanomedicine for Treatment of Ovarian Cancer. Small 2024, 20, e2307462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Chen, G.; Li, Y.; Xu, W.; Gong, S. Quantum-Dot-Based Theranostic Micelles Conjugated with an Anti-EGFR Nanobody for Triple-Negative Breast Cancer Therapy. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2017, 9, 30297–30305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biswas Majee, S.; Avlani, D.; Kumar, A.; Bera, R. Harnessing Nanotheranostics for the Management of Breast and Ovarian Cancer. Acad. Nano Sci. Mater. Technol. 2025, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vishwasrao, H.M.; Master, A.M.; Seo, Y.G.; Liu, X.M.; Pothayee, N.; Zhou, Z.; Yuan, D.; Boska, M.D.; Bronich, T.K.; Davis, R.M.; et al. Luteinizing Hormone Releasing Hormone-Targeted Cisplatin-Loaded Magnetite Nanoclusters for Simultaneous MR Imaging and Chemotherapy of Ovarian Cancer. Chem. Mater. 2016, 28, 3024–3040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taratula, O.; Schumann, C.; Naleway, M.A.; Pang, A.J.; Chon, K.J.; Taratula, O. A Multifunctional Theranostic Platform Based on Phthalocyanine-Loaded Dendrimer for Image-Guided Drug Delivery and Photodynamic Therapy. Mol. Pharm. 2013, 10, 3946–3958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taratula, O.; Taratula, O.; Patel, M.; Schumann, C.; Naleway, M.; He, H.; Pang, A. Phthalocyanine-Loaded Graphene Nanoplatform for Imaging-Guided Combinatorial Phototherapy. Int. J. Nanomed. 2015, 10, 2347–2362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.-J.; Kuan, C.-H.; Wang, L.-W.; Wu, H.-C.; Chen, Y.; Chang, C.-W.; Huang, R.-Y.; Wang, T.-W. Integrated Self-Assembling Drug Delivery System Possessing Dual Responsive and Active Targeting for Orthotopic Ovarian Cancer Theranostics. Biomaterials 2016, 90, 12–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savla, R.; Garbuzenko, O.B.; Chen, S.; Rodriguez-Rodriguez, L.; Minko, T. Tumor-Targeted Responsive Nanoparticle-Based Systems for Magnetic Resonance Imaging and Therapy. Pharm. Res. 2014, 31, 3487–3502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, D.; Moghiseh, M.; Chitcholtan, K.; Mutreja, I.; Lowe, C.; Kaushik, A.; Butler, A.; Sykes, P.; Anderson, N.; Raja, A. Correction: LHRH Conjugated Gold Nanoparticles Assisted Efficient Ovarian Cancer Targeting Evaluated via Spectral Photon-Counting CT Imaging: A Proof-of-Concept Research. J. Mater. Chem. B 2023, 11, 4820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, A.; Li, L.; Wang, Z.; Li, X.; Liang, H.; Yang, J.; Nešić, M.D.; Yang, X.; Lin, Q. Ultrasmall Au-GRHa Nanosystem for FL/CT Dual-Mode Imaging-Guided Targeting Photothermal Therapy of Ovarian Cancer. Anal. Chem. 2025, 97, 2232–2243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demessie, A.A.; Park, Y.; Singh, P.; Moses, A.S.; Korzun, T.; Sabei, F.Y.; Albarqi, H.A.; Campos, L.; Wyatt, C.R.; Farsad, K.; et al. An Advanced Thermal Decomposition Method to Produce Magnetic Nanoparticles with Ultrahigh Heating Efficiency for Systemic Magnetic Hyperthermia. Small Methods 2022, 6, e2200916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schottelius, M.; Berger, S.; Poethko, T.; Schwaiger, M.; Wester, H.-J. Development of Novel 68Ga- and 18F-Labeled GnRH-I Analogues with High GnRHR-Targeting Efficiency. Bioconjugate Chem. 2008, 19, 1256–1268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| LHRHa/ Intervention | Patient (n) | Median Age/Range | Condition | Dosage | Treatment Duration | Response Rate% | Trial Phase | Trial Status | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cetrorelix | 17 | 58 (46–76) | Platinum-resistant OVC | 10 mg/day subcutaneous (after initial 7-day dose-escalation) | Median four cycles (range 2–15) | 18% PR (n = 3) 35% SD (n = 6) | Phase-II | Completed | [72] |

| AN-152 | 42 | 61 (37–77) | Platinum-resistant OVC | 267 mg/m2 IV every 3 weeks | 6–8 cycle (21 days each) | 14.3% PR (n = 6) 38% SD (n = 16) | Phase-II | Completed | [73] |

| EP-100 | 8 | 59 (39–80) | Advanced solid tumors | 2.6–11.7 mg/m2 | ≥16 weeks | 25% SD (n = 2) | Phase-I | Completed | [74] |

| EP-100+PTX, PTX alone | 44 (23 combo, 21 control) | 60 (25–75) 68(43–91) | Recurrent OVC | EP-100 30 mg/m2 twice weekly + Paclitaxel 80 mg/m2 weekly | Median four cycles (up to 16) | 35% in combo, 33% in control | Phase-II | Completed | [75] |

| NPs Type; Physico-Chemical Properties | Conjugated LHRH; Modification Method (Peptide/NP Ratio) | Therapeutic/ Diagnostic Agent Delivery | In Vitro Model (Cell Line, Assay, EC50) | In Vivo Model (Cell Type); Injection Route of Pharma | In Vivo Outcome (Median Survival, Tumor Reduction Size) | Key Findings | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Poly-ε-caprolactone (PCL) NPs; 140–160 nm PCL/IR780-PTX; −20 to −30 mV | LHRHa; covalent conjugation via Schiff’s base reaction | Paclitaxel (PTX); IR780 fluorescent agent | Cytotoxicity assay on paclitaxel resistant cell line SKOV3-TR30 (ST30 cells), IC50 of 1285 nM | BALB/c nude mice bearing ST30 xenograft; intravenous injection | Tumor-growth inhibition ratio of 100% for combination therapy (PCL-LHRH/IR780-PTX + Light) | Complete regression of tumor and no recurrence of disease in vivo after treatment with a combination of chemo-photothermal therapy plus functionalized PCL. | [83] |

| Liposomes; 335 ± 15 nm, −26.4 ± 2.1 mV | LHRHa; electrostatic adsorption (1:2) | Docetaxel (CAS 114977-28-5) | Limit of detection (LOD): 0.12 μg/mL; limit of quantification (LOQ) 0.4 ng | Athymic (nu/nu) mice with SKOV 3 cells xenograft; intravenous injection. | Only the biodistribution study | Nine-fold increase in tumor accumulation and reduced off-target distribution of docetaxel in vivo after treatment with LHRHa-targeted liposomal delivery system. | [84] |

| Liposomes; 342 ± 21 nm; −30 to −35 mV | LHRHa; electrostatic adsorption (1:1, 1:2, 1:5, 1:10) | Docetaxel | Cell uptake study with SKOV3 cells (highest value with a ratio of 1:2 LHRHa/liposomes after 2 h of incubation) | NA | NA | Enhanced cellular uptake achieved in vitro using LHRHa-targeted liposomes loaded with docetaxel for OVC therapy. | [85] |

| PEGylated liposomes; 120–145 nm; −18 to −25 mV | Gonadorelin LHRHa (Pyr-His-Trp-Ser-Tyr-Gly-Leu-Arg-Pro-Gly-NH2); covalent binding (2:1) | Mitoxantrone hydrochloride | Cytotoxicity assay on SKOV3 cells (IC50 of 0.578 μg/mL) | NA | NA | NPs facilitated the specific delivery of the drug to LHRH-R overexpressing tumor cells and efficiently inhibited tumor growth. | [86] |

| Liposomes; 155.1 ± 14.5 nm; −24.1 ± 0.54 mV | LHRHa; Biotin-avidin conjugation (biotinylated LHRHa peptide + avidinylating NPs) | Brucea javanica oil (BJOLs) | Cell viability assay on A2780/DDP cells [inhibitory rates of (37.66 ± 1.73)%, (51.26 ± 3.46)%, and (65.45 ± 4.42)% at 24, 48, and 72 h after treatment, respectively]. | Nude athymic (nu/nu) mice bearing A2780/DDP xenograft; intravenous injection. | Median survival: 58.60 ± 1.03 days. | BJOLs and LHRHa-BJOLs groups of mice had significantly longer survival times than PBS and BJOE groups. In particular, LHRHa-BJOLs exhibited the longest survival time. | [87] |

| Nanogel (Poly (ethylene glycol)170-b-poly (methacrylic acid)180 (PEG-b-PMA) diblock copolymer); 139 ± 4 nm and −22.1 ± 1,7 mV (in water, pH7.4),128 ± 4 nm and −6.8 ± 1.1 mV (in PBS, pH 7.4) | (D-Lys6)-LHRHa; covalent conjugation with EDC/NHs chemistry (1:1) | Cisplatin (CDDP); FITC | Cytotoxicity assay on A2780 cells (IC50 of 9.24 ± 0.9 μg/mL) | Nude athymic (nu/nu) mice bearing A2780 xenograft; intravenous injection. | Tumor inhibition: ~75% from day 2, sustained for 20 days; significantly reduced tumor volume compared to other groups; longest survival; no systemic toxicity | LHRH-nanogels/CDDP were more effective and less toxic than equimolar doses of free CDDP or nanogels/CDDP in the treatment of LHRH-R-positive cancers. | [88] |

| Poly lactic-co-glycolic acid (PLGA) NPs; 637.4 ± 57.0 nm; −6.48 ± 6.71 | LHRHa; covalent conjugation with EDC and INHS chemistry | Irinotecan (CPT-11) + ultrasound (US); FITC | Cytotoxicity assay on A2780/DDP cells (IC50 of 0.2 mg/mL at 72 h) | BALB/c nude mice bearing A2780/DDP xenograft; intravenous injection | Tumor-inhibition rate 73.5% (LHRH-a/CPT-11/PLGA with US) | Superior efficacy of the LHRH-a/CPT-11/PLGA with US treatment over other tested groups, including various controls and CPT-11-based treatments without targeted microspheres or ultrasound | [89] |

| Human serum albumin NPs (HSA); 120–138 nm; −10 to −12 mV | LHRHa; covalent conjugation with EDC chemistry (2, 5, and 10 mg of LHRH added to MTX-HSA NPs) | Methotrexate (MTX) | Cytotoxicity assay on T47D cells (IC50 of 5.82 ± 1.08 nM) | NA | NA | Active targeting with LHRH-MTX-HSA NPs significantly increased the anti-tumoral activity of MTX at low concentrations in comparison to non-targeted MTX-HSA NPs. | [90] |

| Liposomes; 108.52 ± 1.63 nm; −22.07 ± 1.56 mV | LHRHa/RGD co-modified NPs; thioether bond with the Mal functional group at the N-terminus of the liposomes-Mal chain | Paclitaxel (PTX) | Cytotoxicity assay on A2780/DDP cells (IC50 of 0.19 µg/mL) | BALB/c nude mice bearing A2780/DDP xenograft; intravenous injection | Tumor weight reduction: LHRHa-RGD-LP-PTX group (0.29 ± 0.07 g) vs. control (1.90 ± 0.48 g) | LHRHa and RGD co-modified liposomes enhanced the in vivo anti-tumor efficacy against LHRH-R-positive OVC | [91] |

| Micelles composed by triblock copolymers (poly (ethylene oxide)-block-poly (allyl glycidyl ether)-block-poly(DL-lactide) (mPEG-b-PAGE-b-PLA); 15–40 nm | LHRHa; covalent conjugation with EDC/NHs chemistry (0.2:1) | Doxorubicin (DOX); FITC | Cellular uptake study on SKOV3 cells | Nude athymic (nu/nu) mice bearing SKOV3 cells xenograft; intravenous injection. | Only the biodistribution study | LHRH-functionalized micelles can be endocytosed more efficiently by LHRH-R+ve cells than by LHRH-R−ve cells. More LHRH-containing micelles were accumulated in the tumor site than LHRH-free micelles at 24 h post administration. | [92] |

| Lipid microbubbles (TPLMBs); 1.8 ± 0.2 μm; −9.6 ± 3.2 mV | LHRHa (pGlu-His-Trp-Ser-Tyr-D-leu-leu-Arg-Pro-NH2); Biotin-avidin conjugation (biotinylated LHRHa peptide + avidinylating NPs) | Paclitaxel (PTX) + ultrasound (US) | Quantitative assessment of apoptosis on ex vivo tumor (A2780/DDP cells). Strongest tumor apoptosis with TPLMBs + US treatment: (AI 55.94 ± 8.94%) | BALB/c nude mice bearing A2780/DDP xenograft; intravenous injection. | Median survival with TPLMBs + US treatment: +52% vs. control. | Ultrasound-mediated destruction of drug-loaded microbubbles after intraperitoneal administration led to a superior therapeutic outcome in comparison with other treatment options | [93] |

| Magnetic NPs (Fe40Pt60); 60–80 nm | LHRH peptide [Gln-His-Trp-Ser-Tyr-DLys(DCys)-Leu-Arg-Pro-NHEt]; covalent binding with EDC + sulfo-NHS chemistry [FePt-COOH NPs (10 mg)+ 0.4 mg of EDC (2 mM), 1.1 mg of sulfo-NHS (5 mM)+ 0.5 mg of LHRH peptide] | Fe (CO)5 used as a therapeutic agent | MTT viability assay with A2780 cells (IC50 of 1.25 µg Fe/mL) | NA | NA | FePt NPs act as a stable Fe reservoir at physiological pH but release Fe under acidic lysosomal conditions, making them promising agents for targeted ROS-mediated cancer therapy. | [94] |

| Lipid NPs; 508 ± 11.26 nm; −30.53 ± 6.34 mV | LHRH-R mAb Biotin-avidin conjugation (biotinylated LHRHR mAb + avidinylating NPs) | Paclitaxel (PTX) + low-intensity focused ultrasound (LIFU) | Cytotoxicity assay on A2780 cells and OVCAR-3 cells (the survival rate of cells gradually decreased with the increasing concentration of PTX) | Nude athymic (nu/nu) mice bearing OVCAR-3 cells; intravenous injection. | Tumor inhibition rate of ~80% with PTX-anti- LHRHR-NPs + LIFU | The combination therapy of PTX-anti-LHRHR-PTNPs + low-intensity focused ultrasound resulted in enhanced drug release and high therapeutic outcomes. | [95] |

| Cobalt-doped iron oxide NPs (Co-IONPs); 14.5 ± 2.5 nm; +12.5 ± 0.61 mV | LHRHa; covalent conjugation via Michael addition (maleimide-thiol reaction) | Magnetite and maghemite phases for magnetic hyperthermia; NIR fluorescence dye SiNc | Cell viability assay (reduction of 35% viability) | BALB/c nude mice bearing ES-2 xenograft; intravenous injection | 100% inhibition of tumor growth with combination therapy | Complete inhibition of tumor growth in vivo after a single magnetic hyperthermia session using LHRH-targeted cubical bipyramidal Co-doped iron oxide NPs. | [96] |

| NPs Type; Physico-chemical Properties | Conjugated LHRH; Modification Method (Peptide/NP Ratio) | Therapeutic/ Diagnostic Agent Delivery | In Vitro Model (Cell Line, Assay, EC50) | In Vivo Model (Cell Type); Injection Route of Pharma | In Vivo Outcome (Median Survival, Tumor Reduction Size) | Key Findings | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Polyelectrolyte complex (PEC) micelles; 150 nm | LHRHa (Gln-His-Trp-Ser-Tyr- DLys-Leu-Arg-Pro); covalent conjugation with EDC and NHs chemistry | VEGF siRNA; Cy3 fluorescent agent | In vitro VEGF gene suppression assay on SK-OV-3 cells (gene silencing of 70.4 ± 9.4%) and on A2780 cells (gene silencing of 63.2 ± 4.0%) | NA | NA | VEGF siRNA-PEG-LHRH/PEC micelles specifically inhibited VEGF expression in cancer cells in an LHRH-R-specific manner | [97] |

| Polypropylenimine (PPI)dendrimer; 100–200 nm, +1.10 ± 1.54 mV | LHRHa [Gln-His-Trp-Ser-Tyr-DLys(D-Cys)-Leu-Arg-Pro)]; covalent conjugation with EDC and NHs chemistry (2:1) | Paclitaxel + CD44 siRNA; NuLight DY-547 fluorophores | Cytotoxicity assay on cancer cells obtained from the peritoneum area of patients with OVC (viability of ascitic cells decreased almost 10-fold when compared with control cells) | Nude athymic (nu/nu) mice bearing human ascitic xenograft; intravenous injection | Combination therapy led to the almost complete shrinkage of the tumor within the 28-day study period | High therapeutic potential for a combinatorial approach using siRNA against CD44 and cytotoxic agents delivered via PPI dendrimer. | [98] |

| PPIG4 dendrimer; 147.5 ± 0.2 nm; +11.9 ± 0.2 mV; | LHRHa ((Gln-His-Trp-Ser-Tyr-DLys(DCys)-Leu-Arg-Pro-NH-Et), w); covalent conjugation with thiol–maleimide reaction | DJ-1 siRNA + photodynamic therapy (PDT); phthalocyanine | Viability assay on ES2 and A2780/AD cells (therapeutic efficacy of the combinatorial approach improved by 6–20% compared to PDT alone) | Nude athymic (nu/nu) mice bearing A2780/AD cells | Tumors treated with combinatorial therapies were almost eradicated from the mice on the 15th day after the treatment | LHRH-targeted nanoplatform delivering DJ-1 siRNA in combination with phthalocyanine-based PDT enhanced ROS generation, overcame oxidative stress resistance, and achieved complete tumor eradication in cisplatin-resistant cells with high DJ-1 expression. | [99] |

| PPIG4 dendrimer 147.8 ± 11.0 nm; +6.44 ± 2.14 | LHRHa (Gln-His-Trp-Ser-Tyr-DLys(DCys)-Leu-Arg-Pro-NH-Et); covalent conjugation with thiol–maleimide reaction (5:1) | DJ-1 siRNA + cisplatin (CDDP) | Cell viability assay on A2780/CDDP, ES2, and IGROV-1 cells (IC50: 23.6 μM, 3.8 μM, and 1.9 μM, respectively) | NA | NA | LHRH-targeted nanoplatform delivering DJ-1 siRNA in combination with CDDP enhanced apoptosis, reduced proliferation, and increased ROS levels in cisplatin-resistant OVC | [100] |

| PPIG4 dendrimer; 145.2 ± 9.1 nm; +7.7 ± 1.6 mV | LHRHa; covalent conjugation with thiol–maleimide reaction (1.6 μmoles of the LHRH: 50 nanomoles of siRNA) | DJ-1 siRNA + cisplatin (CDDP) | Luciferase-expressing ES-2 (ES-2-luc) cells | Nude athymic (nu/nu) mice bearing ES-2 xenograft; intraperitoneal injection | Mice treated with combinatorial therapies (median survival time >35 vs. 3 weeks for the control group). Reduction in the hazard ratio by 89.7% compared to saline-treated animals | The combination of DJ-1-targeted siRNA with low-dose CDDP using an LHRH-functionalized dendrimer nanoplatform enhanced cytotoxic efficacy, overcame CDDP resistance, and achieved complete tumor eradication in vivo. | [101] |

| PAMAM dendrimer 150 nm; +0.11 ± 0.88 mV | LHRHa [Lys6-des-Gly10-Pro9-ethylamide (Gln-His-Trp-Ser-Tyr-d-Lys-Leu-Arg-Pro-NH-Et)]; covalent conjugation via ester bond | BCL2 siRNA; FITC | MTT assay on A2780 cells with plane LHRH-PAMAM (5–10% of cells with high concentrations up to 12.5 μM) | NA | NA | Dendrimers targeting the plasma membrane of cancer cells significantly enhanced siRNA delivery and gene silencing. | [102] |

| Fe3O4 NPs 8–10 nm; +22.9 ± 0.5 mV | LHRHa [(Glp-HWSY(D-K)LRPG-NH2)]; covalent conjugation with EDC and NHs chemistry | EZH2 siRNA + platinum prodrug; Fe3O4 as an MRI contrast agent | MTT assay on A2780 cells and A2780/DDP (IC50 of 21.9 ± 5.3 μM and 55.6 ± 9.6 μM, respectively) | BALB/c nude mice bearing A2780/DDP xenograft; intravenous injection | Significant reduction in tumor volume | Overcoming CDDP resistance and achieving targeted tumor accumulation in vivo using PEG-LHRH-functionalized Fe3O4 NPs co-delivering Pt (IV) and siEZH2. | [103] |

| Lipid microbubbles 2527.6 ± 496.4 nm | LHRHa (D-Leu6-des-Gly10-Pro9-ehtylamine); Biotin-avidin conjugation (biotinylated LHRHR peptide + avidinylating NPs) | pEGFPN1-wtp53 plasmid; ultrasound (US) | Cell apoptosis assay on A2780/DDP cells with combinatorial approach (39.67 ± 5.95%) | NA | NA | Enhanced gene transfection and apoptosis in OVC cells after ultrasound destruction of LHRHa-microbubbles delivering wtp53. | [104] |

| Protein nanocapsules 9.1 ± 0.8 nm; −0.9 mV | LHRHa (Glp-His-Trp-Ser-Tyr-D-Lys-Leu-Arg-Pro-NHEt); covalent conjugation with amide linkage | Recombinant p53 protein | MTS assay on MDA-MB-231 cells (EC50 of 300 nM at 48 h) | NA | NA | LHRH-targeted nanocapsules enabled functional intracellular delivery of p53 and triggered apoptosis in OVC cells overexpressing LHRH-R. | [105] |

| NPs Type; Physico-Chemical Properties | Conjugated LHRH; Modification Method (Peptide/NP Ratio) | Therapeutic/ Diagnostic Agent Delivery | In Vitro Model (Cell Line, Assay, EC50) | In Vivo Model (Cell Type); Injection Route of Pharma | In Vivo Outcome (MEDIAN Survival, Tumor Reduction Size) | Key Findings | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Magnetic nanoclusters ~72.2 nm; −35.4 mV | LHRHa [d-Lys-6-LHRH (Glp–His–Trp–Ser–Tyr– DLys–Leu–Arg–Pro–Gly]; covalent conjugation with EDC and NHs chemistry | cisplatin (CDDP); Superparamagnetic iron oxide NPs as an MRI contrast agent | Cytotoxicity assay on A2780-WT and A2780-CisR cells (IC50 values at 24 h were 3.2 µM and 18.3 µM, respectively.) | NA | NA | Conjugation with LHRHa enhanced cellular uptake, improved cytotoxicity, and exhibited potential as an MRI contrast agent. | [110] |

| PPI G4 dendrimer NPs 62.3± 0.1; +24.4 mV | LHRHa [Lys6-des-Gly10-Pro9-ethylamide (Gln-His-Trp-Ser-Tyr-DLys(DCys)-Leu-Arg-Pro-NH-Et]; covalent conjugation with amide linkage (1:1) | Phthalocyanine for imaging and photodynamic therapy | Calcein AM cell viability assay on A2780-AD and SKOV3 cells (cell viability decreased by 78% after 15 min of light irradiation) | Nude athymic (nu/nu) mice bearing A2780-AD xenograft; intravenous injection | Only the biodistribution study | Higher tumor uptake, stronger photodynamic therapy upon 670 nm laser irradiation, and effective in vivo tumor imaging | [111] |

| Lowoxy graphene-dendrimer NPs ~78.3 ± 9.5 nm; +6.3 mV | LHRHa (Lys6–des-Gly10–Pro9-ethylamide [Gln–His–Trp–Ser–Tyr–DLys(DCys)–Leu–Arg–Pro–NH–Et]); covalent conjugation with thiol–maleimide reaction (1:1) | Phthalocyanine for imaging and photodynamic therapy | Calcein AM cell viability assay on A2780-AD cells (15 min of light irradiation resulted in only 5% of the cells surviving) | Nude athymic (nu/nu) mice bearing A2780-AD xenograft; intravenous injection | Only the biodistribution study | A combination of PTT and PDT resulted in 90–95% cell death and stronger tumor-targeted NIR imaging. | [112] |

| Self-assembling HA NPs 229 ± 5.6 nm | LHRHa (pyroGlu-His-Trp-Ser-Tyr-Gly-Leu-Arg-Pro-Gly-NH2); covalent conjugation with EDC and NHs chemistry (0.1:1) | Doxorubicin (DOX); Cy5 for fluorescent imaging | MTS assay on OVCAR-3 cells (inhibition of proliferation to less than 40% after 48 h) | Nude athymic (nu/nu) mice bearing OVCAR-3 xenograft; intravenous injection | ROI volume of the LHRH-NPs-treated group decreased to almost 30% of original size compared to that at the beginning of therapy | LHRH-NPs demonstrated enhanced cellular uptake with cytotoxicity in OVC cells, while exhibiting minimal cytotoxicity in normal cells, and strong tumor imaging with Cy5. | [113] |

| PEGylated Mn3O4 NPs 26.68 ± 3.49 | LHRHa [Gln-His-Trp-Ser-Tyr-D-Lys(D-Cys)-Leu-Arg-Pro-NHEt]; covalent conjugation with EDC and NHs chemistry | Vemurafenib; Mn3O4 as MRI contrast agent | MTT assay on A2780 cells (IC50 15 mcg/mL) | Nude athymic (nu/nu) mice bearing A2780 xenograft; intraperitoneal injection | Only the biodistribution study | Selective tumor accumulation with an increase of 22.3% of MRI signal intensity | [114] |

| AuNPs 26.40 nm; −8.78 mv | LHRHa (Ac-Gln-H is-Trp-Ser-Tyr-Gly-Leu-Arg-Pro-Gly-Lys-N Hz trifluoroacetate salt); covalent conjugation with EDC and NHs chemistry | Gold material for spectral photon-counting CT imaging | Apoptotic assay on SKOV3 and OVCAR5 cells (number of necrotic cells 1.18% and 4.39%, respectively) | C57/BL6 mice bearing syngeneic ovarian cancer (ID-8Trp53 wild-type cells); intraperitoneal injection | NA | LHRH-AuNPs showed significantly higher accumulation than AuNPs. Increasing LHRH per particle, they also improved the uptake without cytotoxicity. | [115] |

| Ultra-small AuNPs 3.2 nm; −21.6 mV | LHRHa (GRHa); covalent conjugation with EDC and NHs chemistry | Gold material for CT imaging; photothermal therapy | Cell migration assay on SKOV3 cells [lowest migration (31.86 ± 3.22%) compared to control (88.58 ± 2.80%)] with the combinatorial approach | BALB/c mice bearing syngeneic ovarian cancer (ID8 cells); intravenous injection | Mice with the combinatorial approach (Au-GRHa + NIR group) achieved the best tumor suppression effect | Au-GRHa enabled FL/CT dual-mode imaging, showed >67% targeted uptake in SKOV3 cells, and achieved significant tumor suppression via photothermal therapy. | [116] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Nayak, P.; Varani, M.; Giorgio, A.; Campagna, G.; Caserta, D.; Signore, A. Luteinizing Hormone-Releasing Hormone (LHRH)-Targeted Treatment in Ovarian Cancer. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 11884. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262411884

Nayak P, Varani M, Giorgio A, Campagna G, Caserta D, Signore A. Luteinizing Hormone-Releasing Hormone (LHRH)-Targeted Treatment in Ovarian Cancer. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2025; 26(24):11884. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262411884

Chicago/Turabian StyleNayak, Pallavi, Michela Varani, Anna Giorgio, Giuseppe Campagna, Donatella Caserta, and Alberto Signore. 2025. "Luteinizing Hormone-Releasing Hormone (LHRH)-Targeted Treatment in Ovarian Cancer" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 26, no. 24: 11884. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262411884

APA StyleNayak, P., Varani, M., Giorgio, A., Campagna, G., Caserta, D., & Signore, A. (2025). Luteinizing Hormone-Releasing Hormone (LHRH)-Targeted Treatment in Ovarian Cancer. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 26(24), 11884. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262411884