Platinum Meets Pyridine: Affinity Studies of Pyridinecarboxylic Acids and Nicotinamide for Platinum—Based Drugs

Abstract

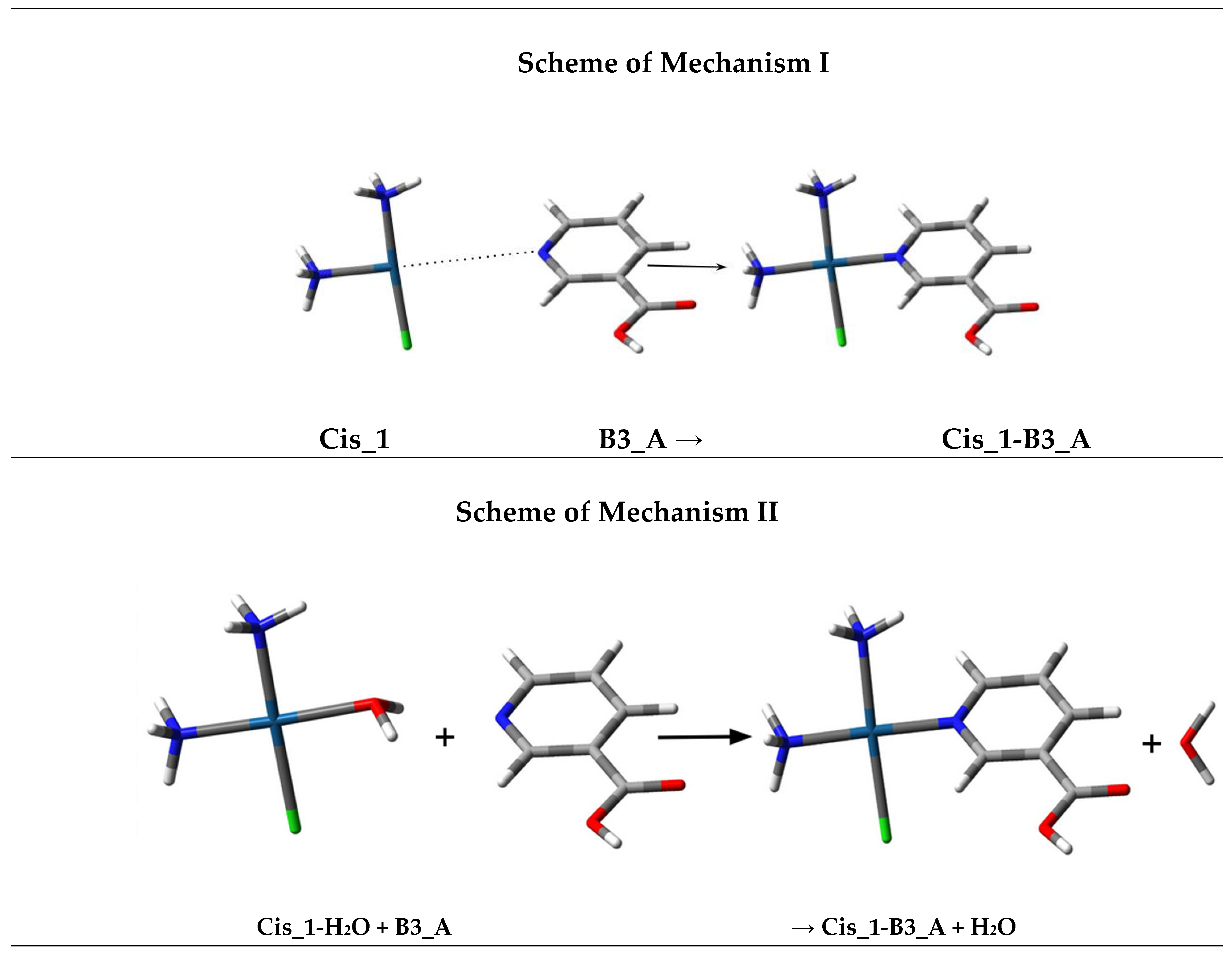

1. Introduction

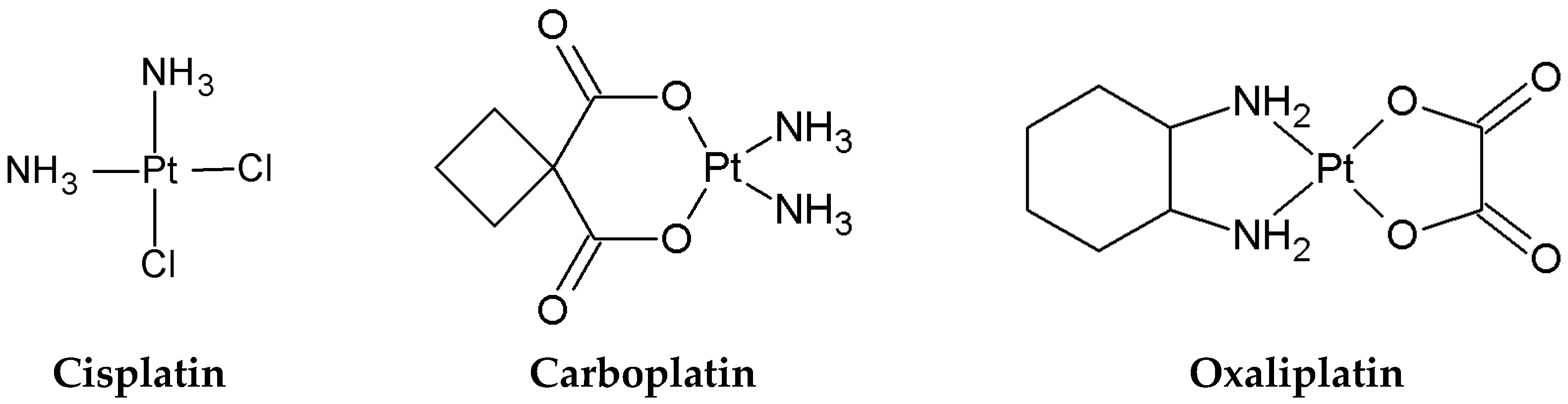

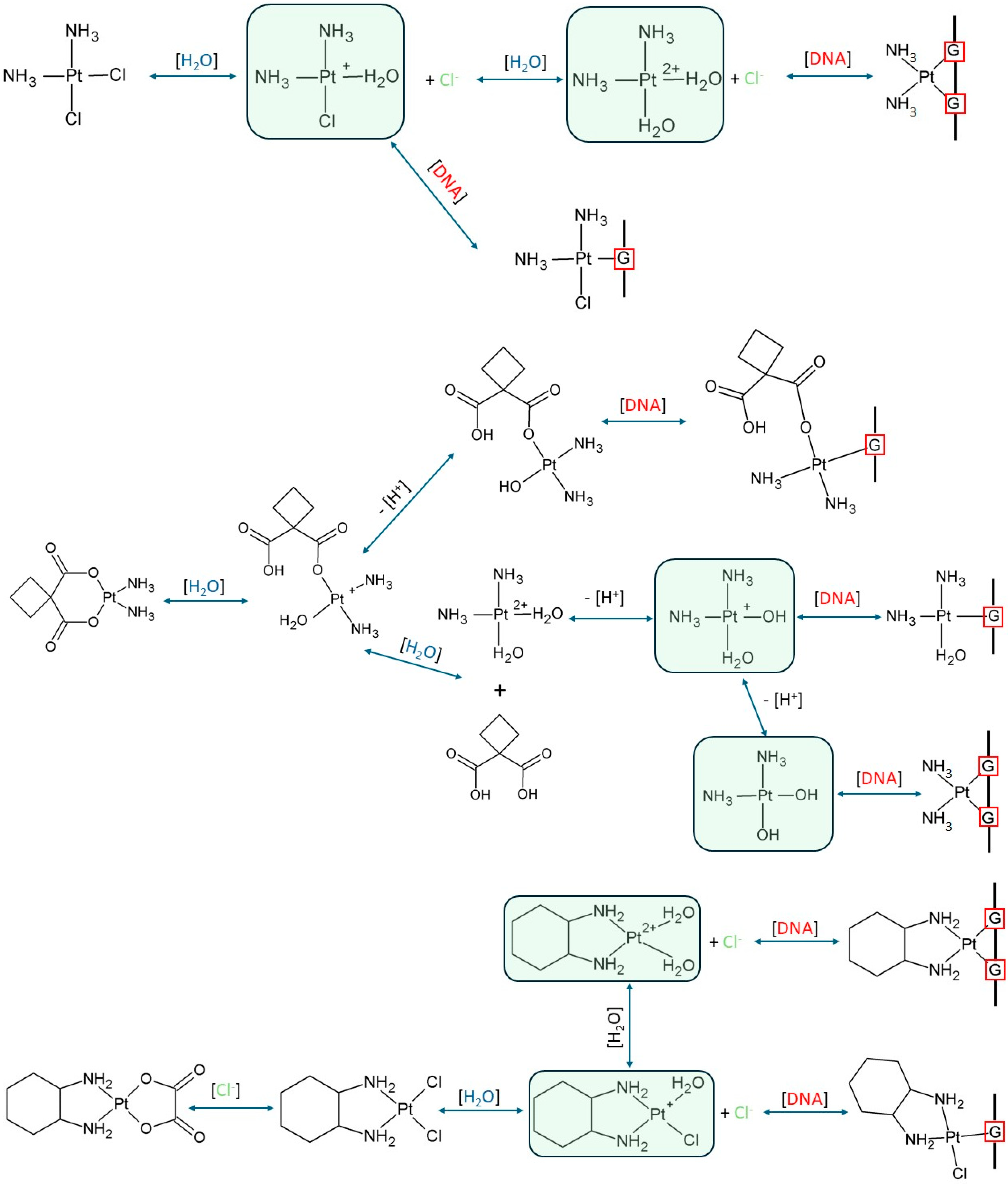

1.1. Mode of Action

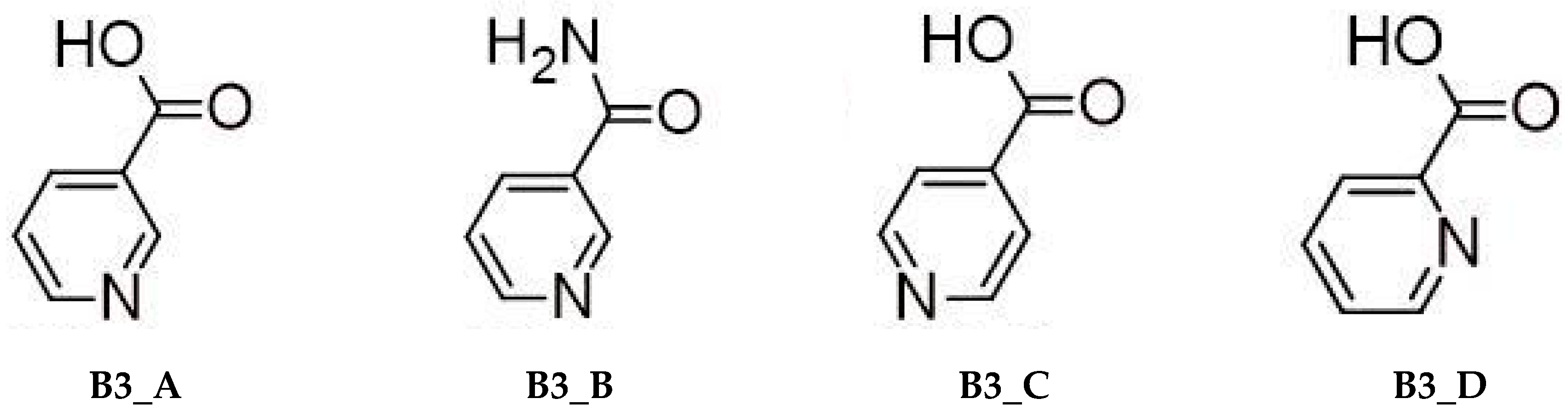

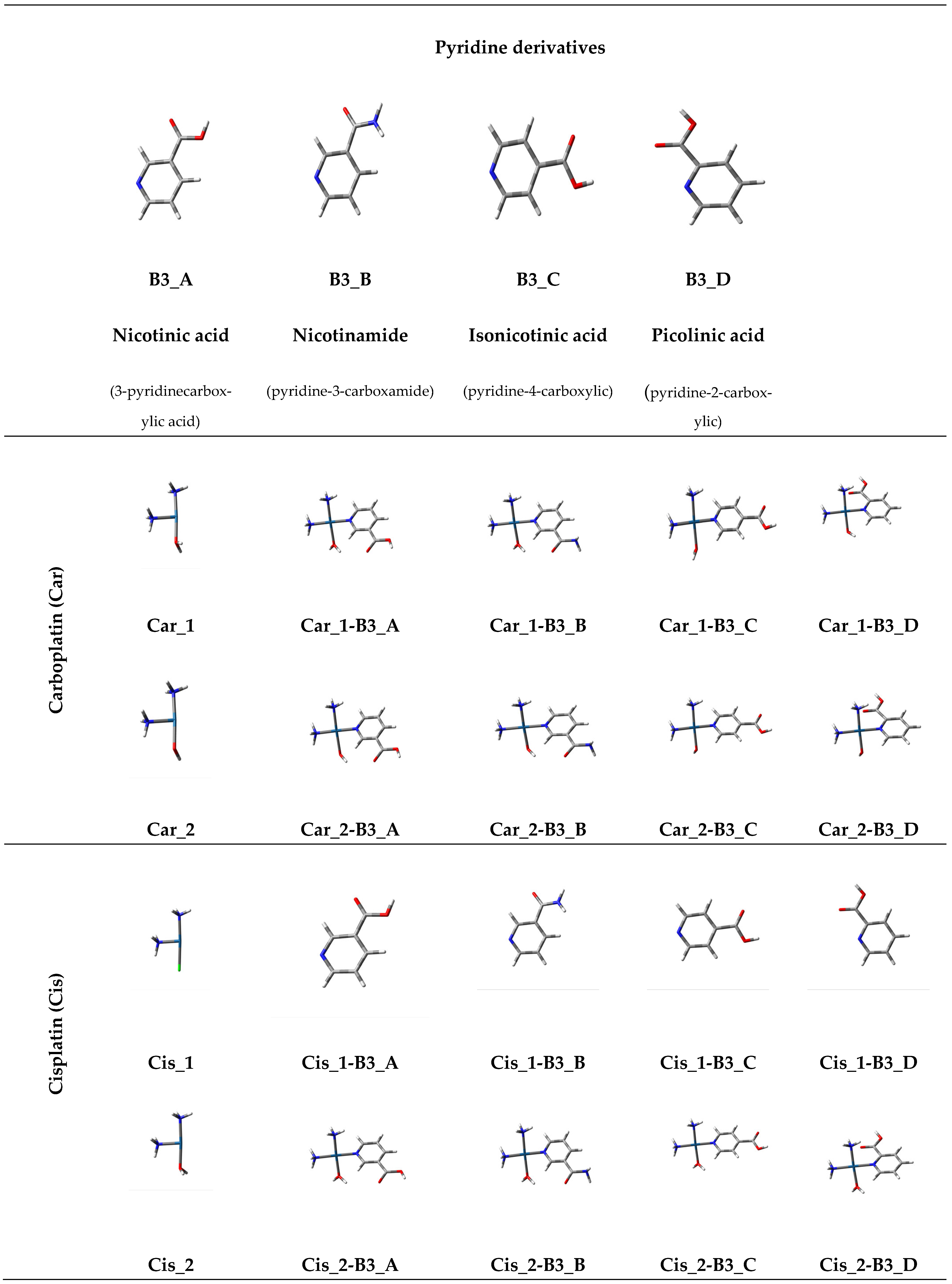

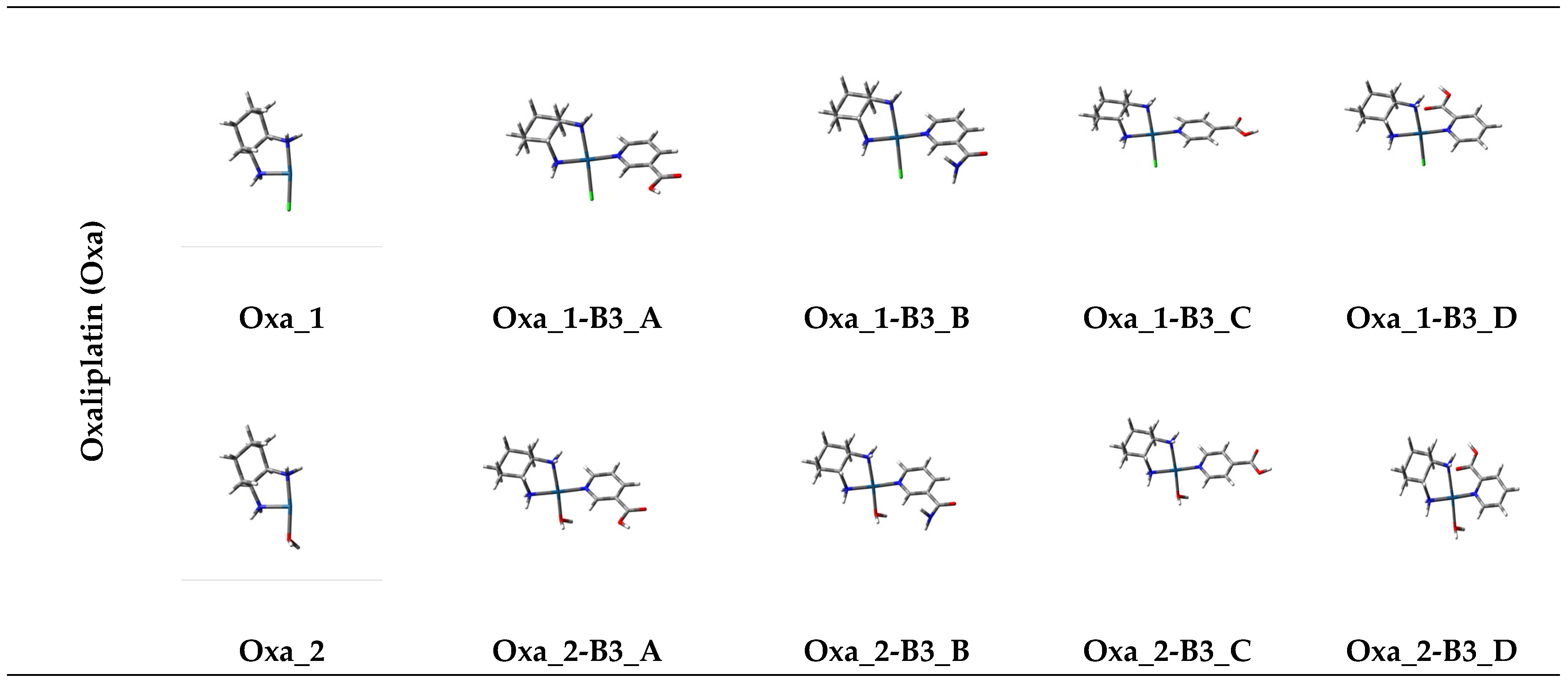

1.2. Pyridine Derivatives

- Nicotinic acid (3-pyridinecarboxylic acid, B3_A).

- Nicotinamide (pyridine-3-carboxamide, B3_B).

- Isonicotinic acid (pyridine-4-carboxylic, B3_C).

- Picolinic acid (pyridine-2-carboxylic, B3_D).

1.3. Significance of Vitamin B3 in the Human Body

- Coenzyme Precursors: Nicotinic acid and Nicotinamide serve as precursors for the vital coenzymes Nicotinamide Adenine Dinucleotide (NAD+) and its phosphorylated form, Nicotinamide Adenine Dinucleotide Phosphate (NADP+).

- Metabolic Role: These coenzymes are required for over 50 oxidation–reduction (redox) reactions in the body. NAD+ is primarily involved in catabolic processes that generate energy from carbohydrates, fats, and proteins, while NADP+ is essential for anabolic reactions, such as the synthesis of fatty acids and cholesterol.

- Cellular Function: The NAD+ system is also a substrate for non-redox reactions, including those involved in DNA repair, cell signalling, and protein modification, which are crucial for maintaining genome stability.

- Deficiency: A severe deficiency of Vitamin B3 causes pellagra, a disease characterized by the “three Ds”: dermatitis, diarrhea, and dementia.

1.4. Pharmacological Importance of Vitamin B3

- Nicotinic Acid (Niacin): It is a long-established prescription medication primarily used to treat dyslipidaemia (high cholesterol and triglycerides). It significantly lowers LDL (“bad”) cholesterol and triglycerides while increasing HDL (“good”) cholesterol.

- Nicotinamide (Niacinamide): This form is preferred for treating niacin deficiency (pellagra) as it avoids the severe flushing side effect caused by Nicotinic acid. Pharmacologically, it is used in dermatology for conditions like acne, rosacea, and has been shown to reduce the incidence of non-melanoma skin cancer (NMSC) in high-risk patients by enhancing DNA repair. It may also be used adjunctively for osteoarthritis and diabetes.

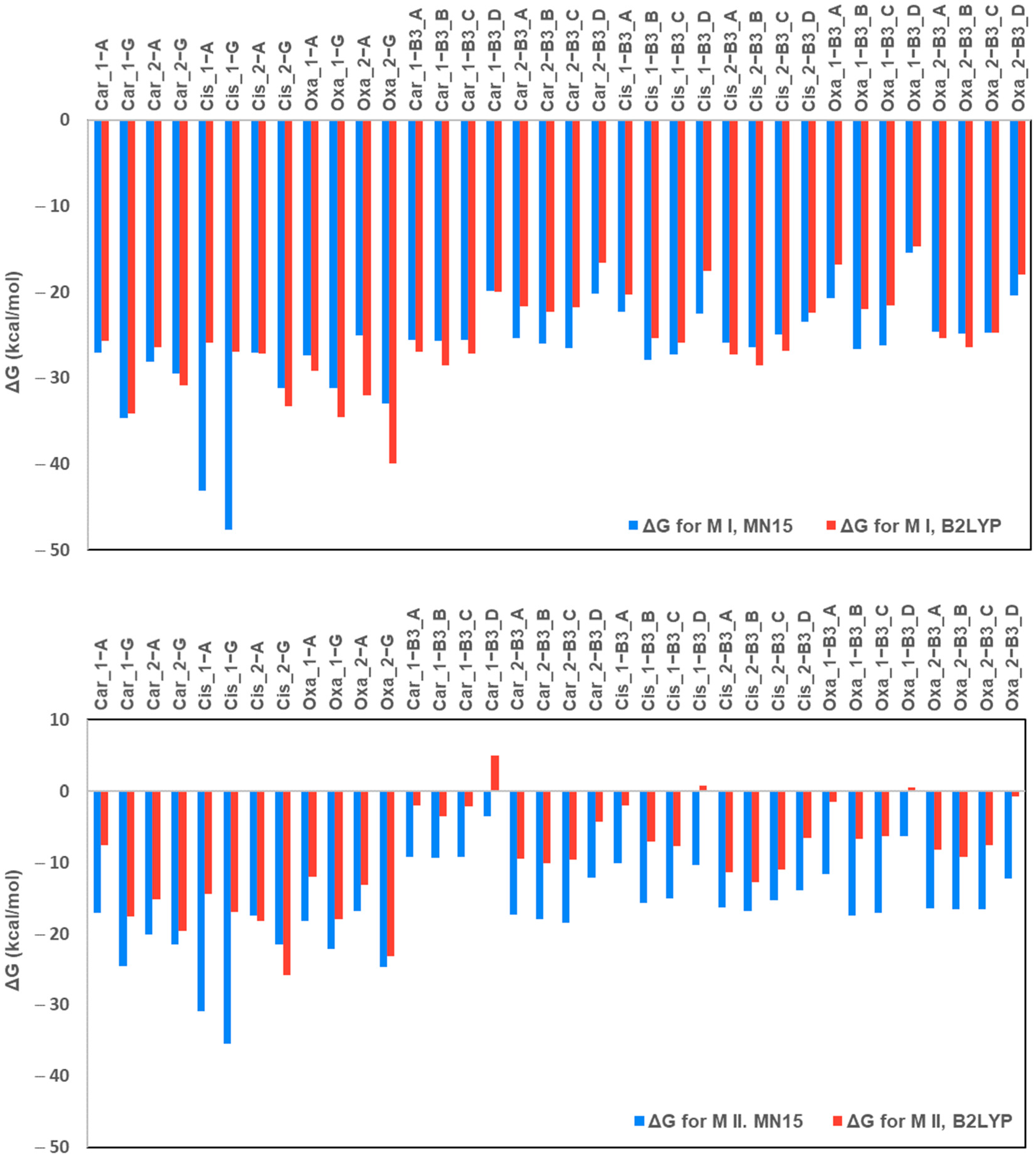

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Gibbs Free Energy Changes (ΔGrs)

2.1.1. Comparison of Computational Methods (B3LYP vs. MN15)

- (i)

- All water substitution reactions remain thermodynamically favourable;

- (ii)

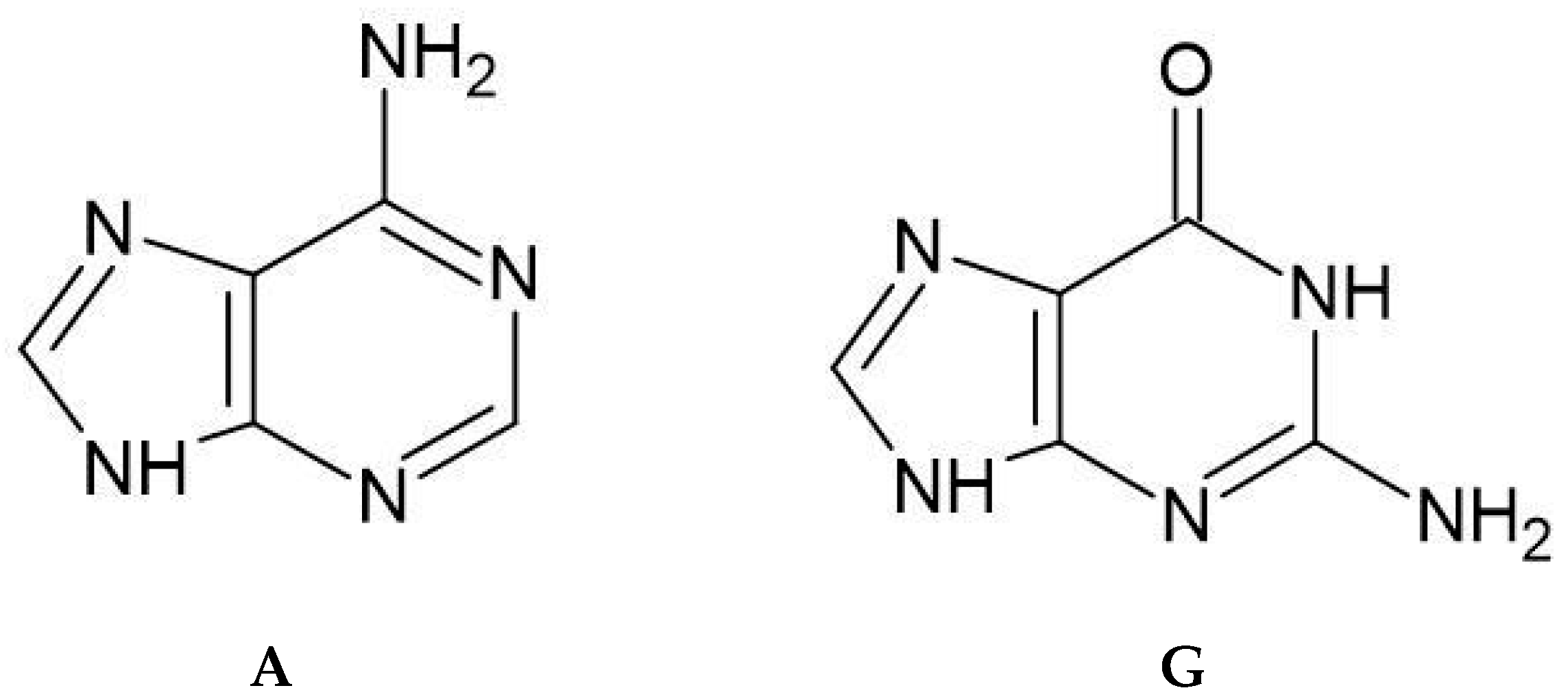

- Guanine consistently exhibits the strongest affinity among all ligands;

- (iii)

- Nicotinamide (B3_B) is the most favourable pyridine derivative; and

- (iv)

- Picolinic acid (B3_D) is the least favourable ligand.

2.1.2. Affinity Trend for Pyridine Derivatives

2.2. HOMO–LUMO Energies and Chemical Properties of Studied Molecules

2.2.1. Properties of Complexes and Method Comparison

- Reactivity: The smaller energy gap (ΔEgap) and higher global electrophilicity index (ω) of the platinum hydrolysis products (Pt-drugs) confirm their nature as highly reactive electrophiles, ready to accept electrons from the ligands.

- Complex Stability: Upon complexation with the ligands, the energy gap (ΔEgap) generally increases, suggesting the resulting complex is more stable and less reactive than the initial Pt-drug fragment.

- Method Consistency: The overall electronic property trends calculated by the MN15 method were consistent with those from the B3LYP method, although minor numerical differences in the values were observed.

2.2.2. Correlation with Gibbs Free Energy (ΔGrs)

2.2.3. Thermodynamic Spontaneity

- Affinity: All hydrolysed platinum forms (Cis_1, Cis_2, Car_1, Car_2, Oxa_1, Oxa_2) exhibit an affinity for all tested compounds (Pyridine derivatives and nucleobases).

- Spontaneity: This affinity is confirmed by the negative ΔGrs values across all complexation reactions calculated by both the B3LYP and MN15 methods, indicating that complex formation is thermodynamically spontaneous.

2.2.4. Correlation of Electronic Structure with Affinity (ΔGrs)

- Overall Highest Affinity: Guanine (G) exhibits the highest affinity among all tested compounds, consistent with its role as the most potent nucleophile, possessing the highest EHOMO and lowest absolute electronegativity (χ) among the free ligands.

- Highest Affinity Pyridine Derivative: Among the Pyridine derivatives, the Pt-drugs show the highest overall affinity for Nicotinamide (B3_B).

- Lowest Affinity Pyridine Derivative: Picolinic acid (B3_D) consistently displayed the lowest affinity among the Pyridine derivatives across nearly all platinum species and methods. The study suggests this lower affinity is due to the unfavourable position of the carboxylic substitution (at position 2).

- Method-Dependent Affinity Trend: The MN15 method generally showed higher affinity for Adenine (A) compared to the Pyridine derivatives, while the B3LYP method showed similar affinities between Adenine and the Pyridine derivatives.

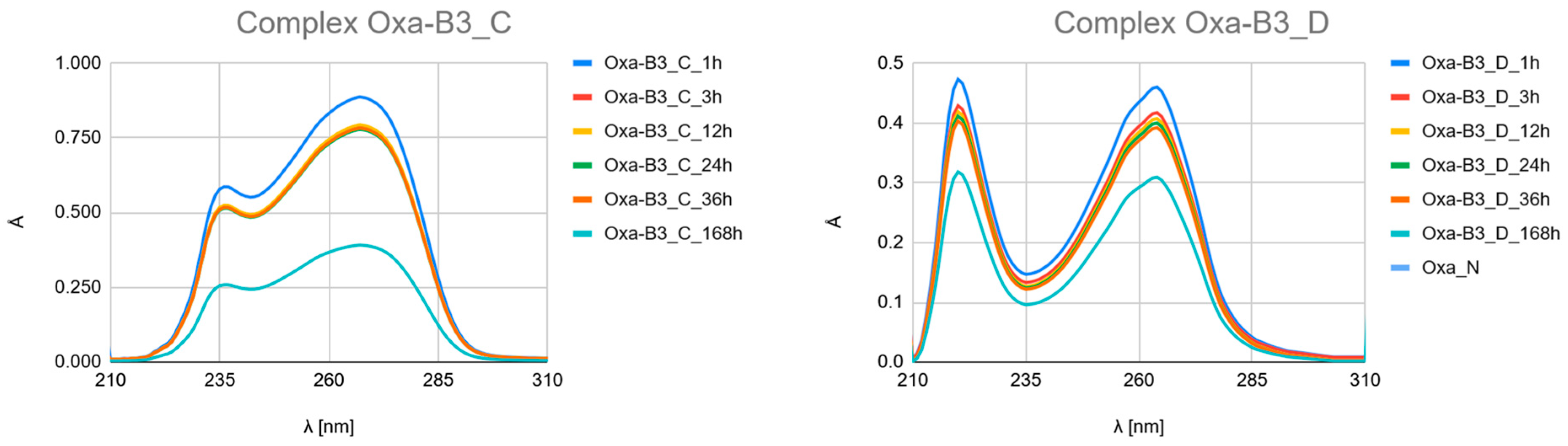

2.3. UVVIS UV-Vis Spectroscopy Analysis and Correlation with Computational Data

2.3.1. Analysis of Experimental UV-Vis Results, the Time-Resolved Evolution of the UV Spectra and Thermodynamic Disparity

The Time-Resolved Evolution of UV Spectra as Hydrolysis and Complexation Kinetics

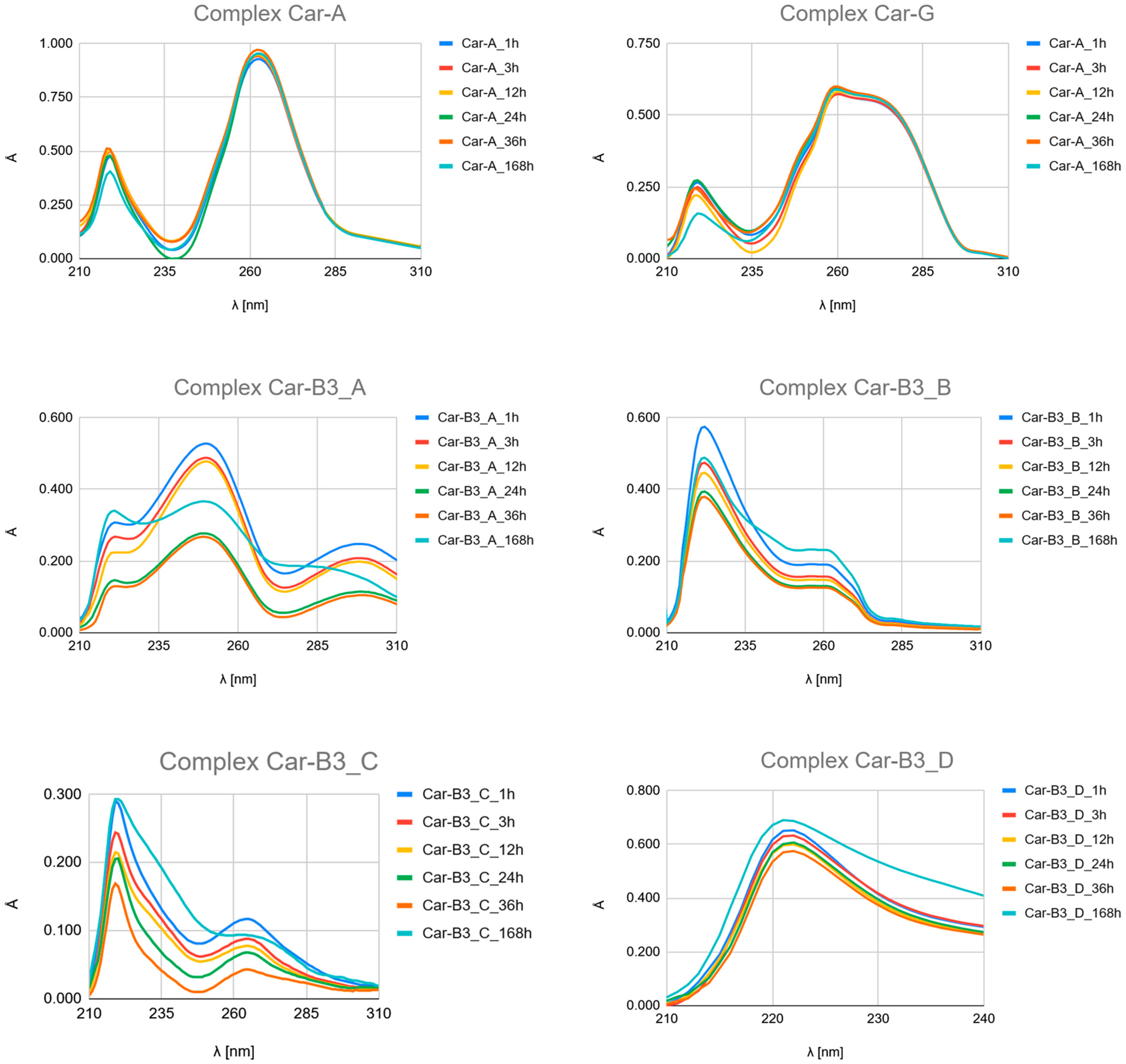

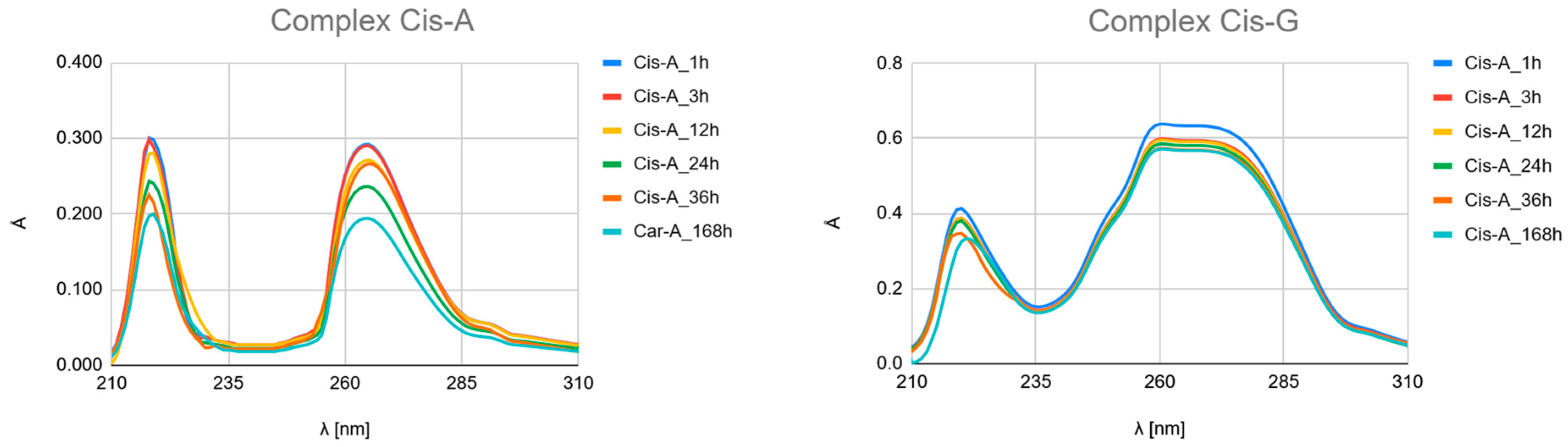

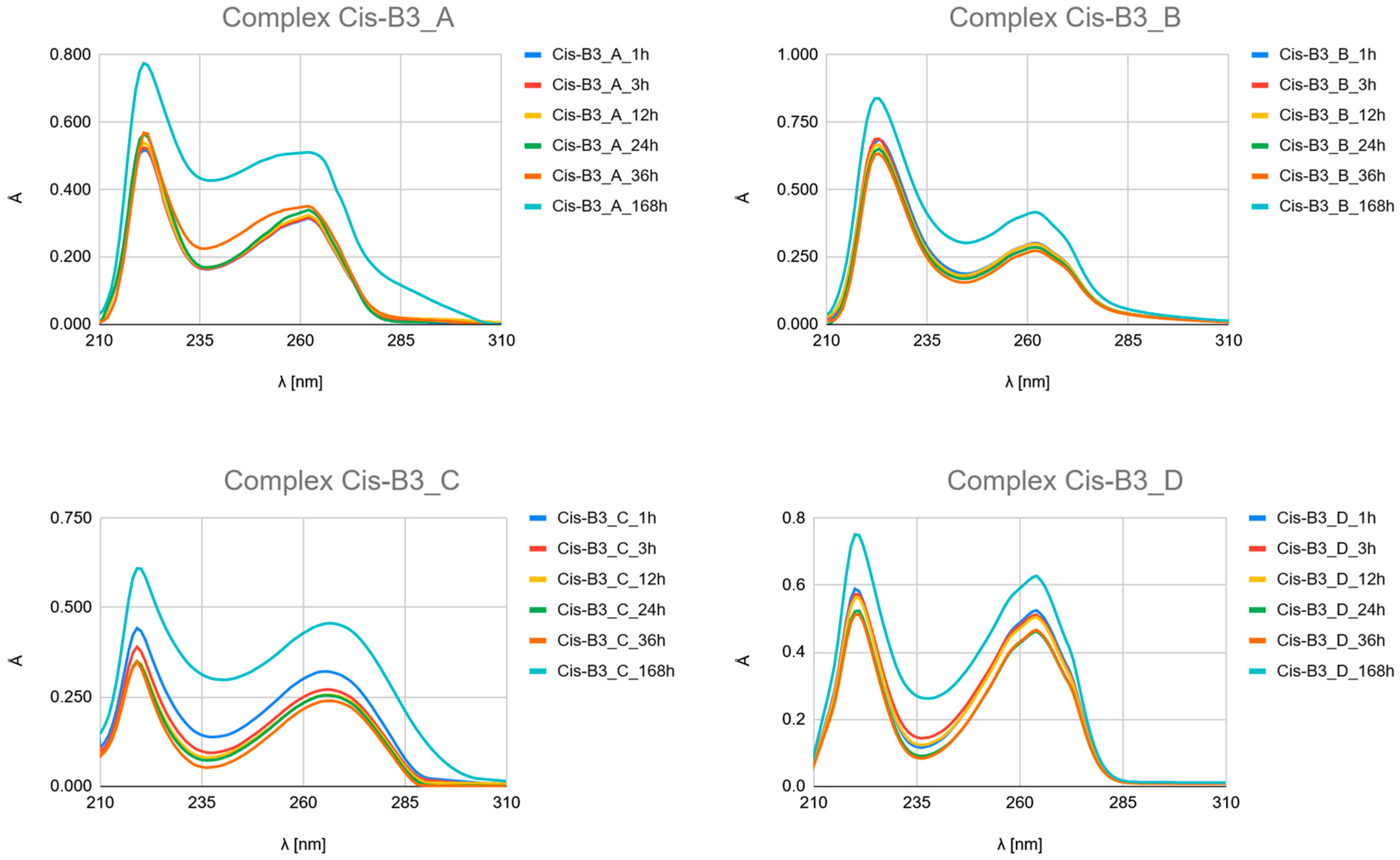

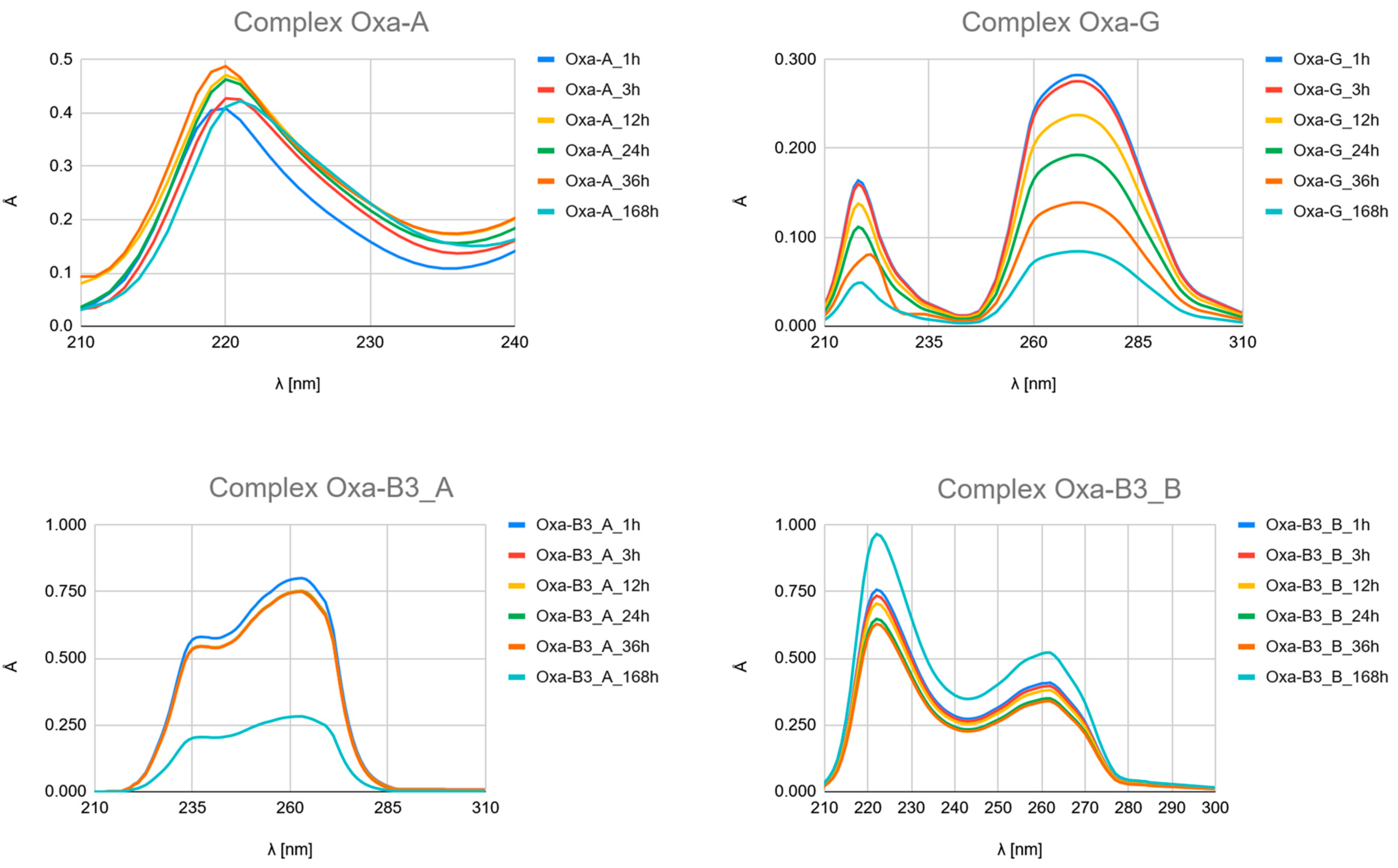

- Carboplatin Hydrolysis (Figure 7 and Figures S6–S10): The observed marked decrease in absorbance peaks (≈220 nm and ≈275 nm) over 168 h is consistent with the slow hydrolysis of the parent drug into less chromophoric aquated species (Car_1 and Car_2), which are the actual reactive intermediates.

- Ligand Binding (Figure 7, Figure 8 and Figure 9 and Figures S4–S24): All spectra confirm the time-dependent formation of new complexes, supporting the multi-step mechanism: hydrolysis followed by ligand substitution.

- Kinetic Outlier (Picolinic Acid, B3_D): Picolinic acid (B3_D) exhibits the most significant spectral evolution, characterized by a substantial and rapid increase in absorbance (e.g., around 220 nm and 265 nm) over time (Figure 7, Figure 8 and Figure 9, Figures S10, S17 and S24). This pronounced change is indicative of a high kinetic preference and rapid formation of a stable, chromophoric chelate complex. This kinetic superiority, however, contrasts sharply with the computational thermodynamic data.

Correlation with Computational Data (ΔGrs, and HOMO-LUMO Gap)

Experimental Time-Resolved Evolution of UV Spectra vs. Computational Thermodynamics and Enthalpy

| Ligand | UV-Vis Evolution | ΔGrs (Thermodynamic Stability) | Conclusion |

| Picolinic Acid (B3_D) | Fastest and most complete reaction. | Lowest affinity (least negative ΔGrs among pyridines). | The chelate effect provides a kinetic advantage, enabling a faster reaction, but the resulting complex is the least thermodynamically stable. |

| Nicotinamide (B3_B) | Fast initial change, stable final complex. | Highest affinity (most negative ΔGrs among pyridines). | The complex is both kinetically accessible and thermodynamically favoured, likely due to optimal electronic fit and bond strength. |

Correlation with Electronic Properties (HOMO-LUMO Gap)

- Nicotinamide (B3_B): Exhibits the lowest ΔEgap (5.8 eV) among the Pyridine derivatives, indicating it is the electronically ‘softest’ ligand. This ‘softness’ aligns perfectly with its highest observed thermodynamic affinity (ΔGrs) for the soft Platinum(II) centre.

- Picolinic Acid (B3_D): Possesses the largest ΔEgap (6.2 eV), confirming its relative electronic “hardness.” This electronic property justifies its lowest calculated thermodynamic stability.

Comparison with Calculated UV-Vis λmax

2.3.2. New Findings and Conclusions from Spectroscopic and Correlative Analysis

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Theoretical Study

- 1.

- B3LYP/6-31G(d,p) [77,78], where platinum atoms were treated with the LanL2DZ [79] basis set, which incorporates relativistic effective core potentials suitable for heavy elements. The B3LYP functional is a hybrid approach recognized for its broad applicability and has been validated in studies of cisplatin–nucleobase interactions.

- 2.

- MN15/def2-TZVP. The MN15 functional is a newer hybrid functional optimized for electronically complex and larger systems, offering enhanced accuracy and reduced error rates [80].

- Energy Gap (ΔEgap): the difference between LUMO and HOMO energies (LUMO-HOMO), serving as an indicator of molecular stability and reactivity. Generally, a smaller gap corresponds to higher reactivity and more facile electronic transitions.

- Chemical Potential (μ): describes the tendency of electrons to escape from a molecular system.

- Absolute Hardness (η): reflects the resistance of a molecule to charge transfer or distortion of its electron cloud; higher values correspond to harder (less reactive) species.

- Absolute Softness (σ): the reciprocal of hardness, indicating how easily charge transfer can occur.

- Global Electrophilicity (ω): quantifies the overall tendency of a molecule to accept electrons, larger values signify stronger electrophilic character.

- Global Softness (S): another measure inversely related to hardness.

- Additional Electronic Charge (ΔNmax): represents the maximum amount of electronic charge a molecule can accommodate.

3.2. Experimental Study

- Pyridine derivatives: Nicotinic acid (99.5% purity) and Nicotinamide (99% purity) from POCH (Avantor Performance Materials Poland S.A., Gliwice, Poland); Isonicotinic acid (100% purity) from Thermo Scientific (Waltham, MA, USA); and Picolinic acid (99% purity) from POL-AURA (Morąg, Poland).

- Nucleosides: Adenosine (99% purity) and Guanosine (98% purity) from TCI (Tokyo, Japan).

- Platinum-based compounds: Cisplatin (98% purity) from Angene (Nanjing, Chine); Carboplatin (98% purity) from TCI (Japan); and Oxaliplatin (98% purity) from POL-AURA (Poland).

4. Conclusions

- Thermodynamic stability (ΔGrs) is governed primarily by the ligand’s electronic properties (HOMO–LUMO gap, softness, and electronegativity);

- Reaction kinetics are significantly influenced by structural factors such as chelation geometry and substituent position;

- Soft–soft electronic complementarity between Pt(II) centres and soft nitrogen-donor ligands underlies the high affinity of Nicotinamide and related compounds.

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Global Cancer Burden Growing, Amidst Mounting Need for Services. Available online: https://www.who.int/news/item/01-02-2024-global-cancer-burden-growing--amidst-mounting-need-for-services (accessed on 7 October 2025).

- Feldman, L.E.R.; Mohapatra, S.; Jones, R.T.; Scholtes, M.; Tilton, C.B.; Orman, M.V.; Joshi, M.; Deiter, C.S.; Broneske, T.P.; Qu, F.; et al. Regulation of Volume-Regulated Anion Channels Alters Sensitivity to Platinum Chemotherapy. Sci. Adv. 2024, 10, eadr9364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenberg, B.; Vancamp, L.; Trosko, J.E.; Mansour, V.H. Platinum Compounds: A New Class of Potent Antitumour Agents. Nature 1969, 222, 385–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosenberg, B.; Van Camp, L.; Krigas, T. Inhibition of Cell Division in Escherichia Coli by Electrolysis Products from a Platinum Electrode. Nature 1965, 205, 698–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kelland, L. The Resurgence of Platinum-Based Cancer Chemotherapy. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2007, 7, 573–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiltshaw, E. Cisplatin in the Treatment of Cancer. Platin. Met. Rev. 1979, 23, 90–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Discovery–Cisplatin and The Treatment of Testicular and Other Cancers-NCI. Available online: https://www.cancer.gov/research/progress/discovery/cisplatin (accessed on 7 October 2025).

- Wagstaff, A.J.; Ward, A.; Benfield, P.; Heel, R.C. Carboplatin: A Preliminary Review of Its Pharmacodynamic and Pharmacokinetic Properties and Therapeutic Efficacy in the Treatment of Cancer. Drugs 1989, 37, 162–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, J.; Robin Ganellin, C. Analogue-Based Drug Discovery; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2006; pp. 1–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Dowd, P.D.; Sutcliffe, D.F.; Griffith, D.M. Oxaliplatin and Its Derivatives–An Overview. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2023, 497, 215439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mariconda, A.; Ceramella, J.; Catalano, A.; Saturnino, C.; Sinicropi, M.S.; Longo, P. Cisplatin, the Timeless Molecule. Inorganics 2025, 13, 246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koster, R.; van Vugt, M.A.; Timmer-Bosscha, H.; Gietema, J.A.; de Jong, S. Unravelling Mechanisms of Cisplatin Sensitivity and Resistance in Testicular Cancer. Expert. Rev. Mol. Med. 2013, 15, e12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ateşşahin, A.; Şanna, E.; Türk, G.; Çeribaşi, A.O.; Yilmaz, S.; Yüce, A.; Bulmuş, Ö. Chemoprotective Effect of Melatonin against Cisplatin-Induced Testicular Toxicity in Rats. J. Pineal Res. 2006, 41, 21–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Armstrong, D.K.; Bundy, B.; Wenzel, L.; Huang, H.Q.; Baergen, R.; Lele, S.; Copeland, L.J.; Walker, J.L.; Burger, R.A. Intraperitoneal Cisplatin and Paclitaxel in Ovarian Cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2006, 354, 34–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knapp, D.W.; Glickman, N.W.; Widmer, W.R.; DeNicola, D.B.; Adams, L.G.; Kuczek, T.; Bonney, P.L.; DeGortari, A.E.; Han, C.; Glickman, L.T. Cisplatin versus Cisplatin Combined with Piroxicam in a Canine Model of Human Invasive Urinary Bladder Cancer. Cancer Chemother. Pharmacol. 2000, 46, 221–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, D.M.; Gupta, S.; Kitchlu, A.; Meraz-Munoz, A.; North, S.A.; Alimohamed, N.S.; Blais, N.; Sridhar, S.S. Defining Cisplatin Eligibility in Patients with Muscle-Invasive Bladder Cancer. Nat. Rev. Urol. 2021, 18, 104–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fennell, D.A.; Summers, Y.; Cadranel, J.; Benepal, T.; Christoph, D.C.; Lal, R.; Das, M.; Maxwell, F.; Visseren-Grul, C.; Ferry, D. Cisplatin in the Modern Era: The Backbone of First-Line Chemotherapy for Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer. Cancer Treat. Rev. 2016, 44, 42–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, G.; Reed, E.; Li, Q.Q. Molecular Basis of Cellular Response to Cisplatin Chemotherapy in Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer (Review). Oncol. Rep. 2004, 12, 955–965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossi, A.; Di Maio, M.; Chiodini, P.; Rudd, R.M.; Okamoto, H.; Skarlos, D.V.; Früh, M.; Qian, W.; Tamura, T.; Samantas, E.; et al. Carboplatin-or Cisplatin-Based Chemotherapy in First-Line Treatment of Small-Cell Lung Cancer: The COCIS Meta-Analysis of Individual Patient Data. J. Clin. Oncol. 2012, 30, 1692–1698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brahmer, J.R.; Ettinger, D.S. Carboplatin in the Treatment of Small Cell Lung Cancer. Oncologist 1998, 3, 143–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, L.; Candelieri-Surette, D.; Anglin-Foote, T.; Lynch, J.A.; Maxwell, K.N.; D’Avella, C.; Singh, A.; Aakhus, E.; Cohen, R.B.; Brody, R.M. Cetuximab-Based vs Carboplatin-Based Chemoradiotherapy for Patients with Head and Neck Cancer. JAMA Otolaryngol.–Head Neck Surg. 2022, 148, 1022–1028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenberger, M.; Hornedo, J.; Silva, H.; Donehower, R.; Spaulding, M.; Van Echo, D. Carboplatin (NSC-241-240): An Active Platinum Analog for the Treatment of Squamous-Cell Carcinoma of the Head and Neck. J. Clin. Oncol. 1986, 4, 1506–1509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waxman, J.; Barton, C. Carboplatin-Based Chemotherapy for Bladder Cancer. Cancer Treat. Rev. 1993, 19, 21–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoneyama, T.; Tobisawa, Y.; Yoneyama, T.; Yamamoto, H.; Imai, A.; Hatakeyama, S.; Hashimoto, Y.; Koie, T.; Ohyama, C. Carboplatin-Based Combination Chemotherapy for Elderly Patients with Advanced Bladder Cancer. Int. J. Clin. Oncol. 2015, 20, 369–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruno, P.M.; Liu, Y.; Park, G.Y.; Murai, J.; Koch, C.E.; Eisen, T.J.; Pritchard, J.R.; Pommier, Y.; Lippard, S.J.; Hemann, M.T. A Subset of Platinum-Containing Chemotherapeutic Agents Kills Cells by Inducing Ribosome Biogenesis Stress. Nat. Med. 2017, 23, 461–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Comella, P.; Casaretti, R.; Sandomenico, C.; Avallone, A.; Franco, L. Role of Oxaliplatin in the Treatment of Colorectal Cancer. Ther. Clin. Risk Manag. 2009, 5, 229–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arango, D.; Wilson, A.J.; Shi, Q.; Corner, G.A.; Arañes, M.J.; Nicholas, C.; Lesser, M.; Mariadason, J.M.; Augenlicht, L.H. Molecular Mechanisms of Action and Prediction of Response to Oxaliplatin in Colorectal Cancer Cells. Br. J. Cancer 2004, 91, 1931–1946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Xu, C.; Gao, X.; Yao, Q. Platinum-Based Drugs for Cancer Therapy and Anti-Tumor Strategies. Theranostics 2022, 12, 2115–2132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spreckelmeyer, S.; Orvig, C.; Casini, A. Cellular Transport Mechanisms of Cytotoxic Metallodrugs: An Overview beyond Cisplatin. Molecules 2014, 19, 15584–15610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larson, C.A.; Blair, B.G.; Safaei, R.; Howell, S.B. The Role of the Mammalian Copper Transporter 1 in the Cellular Accumulation of Platinum-Based Drugs. Mol. Pharmacol. 2009, 75, 324–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omondi, R.O.; Ojwach, S.O.; Jaganyi, D. Review of Comparative Studies of Cytotoxic Activities of Pt(II), Pd(II), Ru(II)/(III) and Au(III) Complexes, Their Kinetics of Ligand Substitution Reactions and DNA/BSA Interactions. Inorganica Chim. Acta 2020, 512, 119883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sherman, S.E.; Gibson, D.; Wang, A.H.J.; Lippard, S.J. X-Ray Structure of the Major Adduct of the Anticancer Drug Cisplatin with DNA: Cis-[Pt(NH3)2{d(PGpG)}]. Science (1979) 1985, 230, 412–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Panina, N.S.; Belyaev, A.N.; Eremin, A.V.; Stepanova, M.A.; Panin, A.I. Quantum Chemical Modeling of Nucleophilic Substitution Reactions in the Complexes Cis-Pt(NH3)2Cl2 and Cis-Pd(NH3)2Cl2. Russ. Chem. Bull. 2012, 61, 796–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivanov, A.I.; Christodoulou, J.; Parkinson, J.A.; Barnham, K.J.; Tucker, A.; Woodrow, J.; Sadler, P.J. Cisplatin Binding Sites on Human Albumin. J. Biol. Chem. 1998, 273, 14721–14730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baik, M.H.; Friesner, R.A.; Lippard, S.J. Theoretical Study of Cisplatin Binding to Purine Bases: Why Does Cisplatin Prefer Guanine over Adenine? J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2003, 125, 14082–14092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodsell, D.S. The Molecular Perspective: Cisplatin. Stem Cells 2006, 24, 514–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elding, L.I.; ÖSten, G. Kinetics and Mechanism for Ligand Substitution Reactions of Square-Planar (Dimethyl Sulfoxide)Platinum(II) Complexes. Stability and Reactivity Correlations. Inorg. Chem. 2002, 17, 1872–1880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Links to Inorganic Chemistry 8th Edition (OUP) by Mark Weller, Jonathan Rourke, Fraser Armstrong, Simon Lancaster and Tina Overton. Available online: https://www.chemtube3d.com/wellerlink/ (accessed on 7 November 2025).

- Section 7.3: Ligand Substitution Mechanisms-Chemistry LibreTexts. Available online: https://chem.libretexts.org/Courses/Centre_College/CHE_332%3A_Inorganic_Chemistry/07%3A_Coordination_Chemistry-_Reactions_and_Mechanisms/7.03%3A_Ligand_Substitution_Mechanisms (accessed on 7 November 2025).

- Substitution Reactions in Square Planar Complexes|Inorganic Chemistry II Class Notes. Available online: https://fiveable.me/inorganic-chemistry-ii/unit-4/substitution-reactions-square-planar-complexes/study-guide/zBFvnXicbma8JGEL (accessed on 7 November 2025).

- Taube, H. Rates and Mechanisms of Substitution in Inorganic Complexes in Solution. Chem. Rev. 2002, 50, 69–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fred, B. Mechanisms of Inorganic Reactions; A Study of Metal Complexes in Solution; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 1920. [Google Scholar]

- Berners-Price, S.J.; Ronconi, L.; Sadler, P.J. Insights into the Mechanism of Action of Platinum Anticancer Drugs from Multinuclear NMR Spectroscopy. Prog. Nucl. Magn. Reson. Spectrosc. 2006, 49, 65–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pizarro, A.M.; Barry, N.P.E.; Sadler, P.J. Metal–DNA Coordination Complexes. In Comprehensive Inorganic Chemistry II; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2013; pp. 751–784. ISBN 978-0-08-096529-1. [Google Scholar]

- Otto, S.; Elding, L.I. Low Temperature Kinetic Study of Very Fast Substitution Reactions at Platinum(II) Trans to Olefins. J. Chem. Society. Dalton Trans. 2002, 11, 2354–2360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samanta, A.; Ghosh, G.K.; Mitra, I.; Mukherjee, S.; Jagadeesh, C.B.K.; Mukhopadhyay, S.; Linert, W.; Moi, S.C. Ligand Substitution Reaction on a Platinum(II) Complex with Bio-Relevant Thiols: Kinetics, Mechanism and Bioactivity in Aqueous Medium. RSC Adv. 2014, 4, 43516–43524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romeo, R.; Plutino, M.R.; Scolaro, L.M.; Stoccoro, S.; Minghetti, G. Role of Cyclometalation in Controlling the Rates of Ligand Substitution at Platinum(II) Complexes. Inorg. Chem. 2000, 39, 4749–4755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicholls, D. Complexes and First-Row Transition Elements. In Complexes and First-Row Transition Elements; Red Globe Press: London, UK, 1974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, E.; Giandornenico, C.M. Current Status of Platinum-Based Antitumor Drugs. Chem. Rev. 1999, 99, 2451–2466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamieson, E.R.; Lippard, S.J. Structure, Recognition, and Processing of Cisplatin−DNA Adducts. Chem. Rev. 1999, 99, 2467–2498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di Pasqua, A.J.; Goodisman, J.; Kerwood, D.J.; Toms, B.B.; Dubowy, R.L.; Dabrowiak, J.C. Activation of Carboplatin by Carbonate. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 2005, 19, 139–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reedijk, J. New Clues for Platinum Antitumor Chemistry: Kinetically Controlled Metal Binding to DNA. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2003, 100, 3611–3616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zayed, A.; Jones, G.D.D.; Reid, H.J.; Shoeib, T.; Taylor, S.E.; Thomas, A.L.; Wood, J.P.; Sharp, B.L. Speciation of Oxaliplatin Adducts with DNA Nucleotides. Metallomics 2011, 3, 991–1000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ip, V.; McKeage, M.J.; Thompson, P.; Damianovich, D.; Findlay, M.; Liu, J.J. Platinum-Specific Detection and Quantification of Oxaliplatin and Pt(R,R-Diaminocyclohexane)Cl2 in the Blood Plasma of Colorectal Cancer Patients. J. Anal. Spectrom. 2008, 23, 881–884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jerremalm, E.; Hedeland, M.; Wallin, I.; Bondesson, U.; Ehrsson, H. Oxaliplatin Degradation in the Presence of Chloride: Identification and Cytotoxicity of the Monochloro Monooxalato Complex. Pharm. Res. 2004, 21, 891–894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raymond, E.; Chaney, S.G.; Taamma, A.; Cvitkovic, E. Oxaliplatin: A Review of Preclinical and Clinical Studies. Ann. Oncol. 1998, 9, 1053–1071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riddell, I.A.; Lippard, S.J. Cisplatin and Oxaliplatin: Our Current Understanding of Their Actions. In Metallo-Drugs: Development and Action of Anticancer Agents; De Gruyter: Berlin, Germany, 2018; pp. 1–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, F.; Lin, X.; Okuda, T.; Howell, S.B. DNA Polymerase ζ Regulates Cisplatin Cytotoxicity, Mutagenicity, and The Rate of Development of Cisplatin Resistance. Cancer Res. 2004, 64, 8029–8035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szefler, B.; Czeleń, P.; Szczepanik, A.; Cysewski, P. Does the Affinity of Cisplatin to B-Vitamins Impair the Therapeutic Effect in the Case of Patients with Lung Cancer-Consuming Carrot or Beet Juice? Anticancer Agents Med. Chem. 2019, 19, 1775–1783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szefler, B.; Czeleń, P.; Krawczyk, P. The Affinity of Carboplatin to B-Vitamins and Nucleobases. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 3634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szefler, B.; Czeleń, P.; Wojtkowiak, K.; Jezierska, A. Affinities to Oxaliplatin: Vitamins from B Group vs. Nucleobases. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 10567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szefler, B.; Czeleń, P.; Kruszewski, S.; Siomek-Górecka, A.; Krawczyk, P. The Assessment of Physicochemical Properties of Cisplatin Complexes with Purines and Vitamins B Group. J. Mol. Graph. Model. 2022, 113, 108144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Szupryczyński, K.; Szefler, B. Interactions of Nedaplatin with Nucleobases and Purine Alkaloids: Their Role in Cancer Therapy. Biomedicines 2025, 13, 1551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goyal, R.N.; Sangal, A. Electrochemical Investigations of Adenosine at Solid Electrodes. J. Electroanal. Chem. 2002, 521, 72–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, J. Specific Detection of Nucleotides, Creatine Phosphate, and Their Derivatives from Tissue Samples in a Simple, Isocratic, Recycling, Low-Volume System. LC-GC Int. 1995, 8, 254–264. [Google Scholar]

- Saha, D.; Diamai, S.; Warjri, W.; Negi, D.P.S. Effect of PH on the Interaction of Hypoxanthine and Guanine with Colloidal ZnS Nanoparticles: A Spectroscopic Approach. J. Mol. Liq. 2019, 278, 460–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nkungli, N.K.; Ghogomu, J.N.; Nogheu, L.N.; Gadre, S.R.; Nkungli, N.K.; Ghogomu, J.N.; Nogheu, L.N.; Gadre, S.R. DFT and TD-DFT Study of Bis [2-(5-Amino-[1,3,4]-Oxadiazol-2-Yl) Phenol](Diaqua)M(II) Complexes [M = Cu, Ni and Zn]: Electronic Structures, Properties and Analyses. Comput. Chem. 2015, 3, 29–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartecki, A.; Szoke, J.; Varsanyi, G.; Vizesy, M. Absorption Spectra in the Ultraviolet and Visible Region. Phys. Today 1966, 3, 280. [Google Scholar]

- Velho, P.; Rebelo, C.S.; Macedo, E.A. Extraction of Gallic Acid and Ferulic Acid for Application in Hair Supplements. Molecules 2023, 28, 2369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 2-Pyridinecarboxylic Acid-Optional[UV-VIS]-Spectrum-SpectraBase. Available online: https://spectrabase.com/spectrum/55HDqv4kAqB (accessed on 13 October 2025).

- Tamer, Ö.; Tamer, S.A.; İdil, Ö.; Avcı, D.; Vural, H.; Atalay, Y. Antimicrobial Activities, DNA Interactions, Spectroscopic (FT-IR and UV-Vis) Characterizations, and DFT Calculations for Pyridine-2-Carboxylic Acid and Its Derivates. J. Mol. Struct. 2018, 1152, 399–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soori, H.; Rabbani-Chadegani, A.; Davoodi, J. Exploring Binding Affinity of Oxaliplatin and Carboplatin, to Nucleoprotein Structure of Chromatin: Spectroscopic Study and Histone Proteins as a Target. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2015, 89, 844–850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poodat, M.; Divsalar, A.; Ghalandari, B.; Khavarinezhad, R. A New Nano-Delivery System for Cisplatin Using Green-Synthesized Iron Oxide Nanoparticles. J. Iran. Chem. Soc. 2023, 20, 739–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kohn, W.; Sham, L.J. Self-Consistent Equations Including Exchange and Correlation Effects. Phys. Rev. 1965, 140, A1133–A1138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hohenberg, P.; Kohn, W. Inhomogeneous Electron Gas. Phys. Rev. 1964, 136, B864–B871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 76. Frisch, M.J.; Trucks, G.W.; Schlegel, H.B.; Scuseria, G.E.; Robb, M.A.; Cheeseman, J.R.; Scalmani, G.; Barone, V.; Petersson, G.A.; Nakatsuji, H.; et al. Gaussian 16; Revision A.03; Gaussian, Inc.: Wallingford, CT, USA, 2016; Gaussian 16|Gaussian.com. [Google Scholar]

- Becke, A.D. Density-functional Thermochemistry. III. The Role of Exact Exchange. J. Chem. Phys. 1993, 98, 5648–5652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ditchfield, R.; Hehre, W.J.; Pople, J.A. Self-Consistent Molecular-Orbital Methods. IX. An Extended Gaussian-Type Basis for Molecular--Orbital Studies of Organic Molecules. J. Chem. Phys. 1971, 54, 724–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunning, T.H., Jr. Gaussian Basis Sets for Use in Correlated Molecular Calculations. I. The Atoms Boron through Neon and Hydrogen. J. Chem. Phys. 1989, 90, 1007–1023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weigend, F.; Ahlrichs, R. Balanced Basis Sets of Split Valence, Triple Zeta Valence and Quadruple Zeta Valence Quality for H to Rn: Design and Assessment of Accuracy. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2005, 7, 3297–3305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barone, V.; Cossi, M.; Tomasi, J. A New Definition of Cavities for the Computation of Solvation Free Energies by the Polarizable Continuum Model. J. Chem. Phys. 1997, 107, 3210–3221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perdew, J.P.; Burke, K.; Ernzerhof, M. Generalized Gradient Approximation Made Simple. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1996, 77, 3865–3868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, T.; Chen, F. Multiwfn: A Multifunctional Wavefunction Analyzer. J. Comput. Chem. 2012, 33, 580–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bukheet Hassan, H. Density Function Theory B3LYP/6-31G**Calculation of Geometry Optimization and Energies of Donor-Bridge-Acceptor Molecular System. Int. J. Curr. Eng. Technol. 2014, 4, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Omondi, R.O.; Jaganyi, D.; Ojwach, S.O.; Fatokun, A.A. (Pyridyl)Benzoazole Ruthenium(III) Complexes: Kinetics of Ligand Substitution Reaction and Potential Cytotoxic Properties. Inorganica Chim. Acta 2018, 482, 213–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Reaction | Mechanism I | Mechanism II |

|---|---|---|

| ΔGrs [kcal/mol] | ||

| Cis_1 + A → Cis_1 − A | −25.86 | −14.44 |

| Cis_1 + G → Cis_1 − G | −26.92 | −17.00 |

| Cis_1 + B3_A → Cis_1 − B3_A | −20.30 | −2.01 |

| Cis_1 + B3_B → Cis_1 − B3_B | −25.33 | −7.04 |

| Cis_1 + B3_C → Cis_1 − B3_C | −25.94 | −7.65 |

| Cis_1 + B3_D → Cis_1 − B3_D | −17.55 | 0.73 |

| Cis_2 + A → Cis_2 − A | −27.15 | −18.18 |

| Cis_2 + G → Cis_2 − G | −33.33 | −25.85 |

| Cis_2 + B3_A → Cis_2 − B3_A | −27.27 | −11.43 |

| Cis_2 + B3_B → Cis_2 − B3_B | −28.56 | −12.72 |

| Cis_2 + B3_C → Cis_2 − B3_C | −26.79 | −10.94 |

| Cis_2 + B3_D → Cis_2 − B3_D | −22.38 | −6.53 |

| Car_1 + A → Car_1 − A | −25.73 | −7.4 |

| Car_1 + G → Car_1 − G | −34.12 | −17.53 |

| Car_1 + B3_A → Car_1 − B3_A | −26.96 | −1.99 |

| Car_1 + B3_B → Car_1 − B3_B | −28.54 | −3.58 |

| Car_1 + B3_C → Car_1 − B3_C | −27.16 | −2.19 |

| Car_1 + B3_D → Car_1 − B3_D | −19.97 | 5.00 |

| Car_2 + A → Car_2 − A | −26.46 | −15.15 |

| Car_2 + G → Car_2 − G | −30.89 | −19.66 |

| Car_2 + B3_A → Car_2 − B3_A | −21.70 | −9.51 |

| Car_2 + B3_B → Car_2 − B3_B | −22.34 | −10.15 |

| Car_2 + B3_C → Car_2 − B3_C | −21.76 | −9.57 |

| Car_2 + B3_D → Car_2 − B3_D | −16.64 | −4.27 |

| Oxa_1 + A → Oxa_1 − A | −29.20 | −12.01 |

| Oxa_1 + G → Oxa_1 − G | −34.52 | −17.99 |

| Oxa_1 + B3_A → Oxa_1 − B3_A | −16.78 | −1.46 |

| Oxa_1 + B3_B → Oxa_1 − B3_B | −21.95 | −6.63 |

| Oxa_1 + B3_C → Oxa_1 − B3_C | −21.61 | −6.29 |

| Oxa_1 + B3_D → Oxa_1 − B3_D | −14.75 | 0.56 |

| Oxa_2 + A → Oxa_2 − A | −31.98 | −13.12 |

| Oxa_2 + G → Oxa_2 − G | −39.97 | −23.10 |

| Oxa_2 + B3_A → Oxa_2 − B3_A | −25.34 | −8.16 |

| Oxa_2 + B3_B → Oxa_2 − B3_B | −26.43 | −9.26 |

| Oxa_2 + B3_C → Oxa_2 − B3_C | −24.73 | −7.56 |

| Oxa_2 + B3_D → Oxa_2 − B3_D | −17.97 | −0.80 |

| Reaction | Mechanism I | Mechanism II |

|---|---|---|

| ΔGrs [kcal/mol] | ||

| Cis_1 + A → Cis_1 − A | −43.06 | −30.86 |

| Cis_1 + G → Cis_1 − G | −47.66 | −35.46 |

| Cis_1 + B3_A → Cis_1 − B3_A | −22.27 | −10.07 |

| Cis_1 + B3_B → Cis_1 − B3_B | −27.89 | −15.69 |

| Cis_1 + B3_C → Cis_1 − B3_C | −27.22 | −15.02 |

| Cis_1 + B3_D → Cis_1 − B3_D | −22.55 | −10.35 |

| Cis_2 + A → Cis_2 − A | −27.08 | −17.45 |

| Cis_2 + G → Cis_2 − G | −31.18 | −21.55 |

| Cis_2 + B3_A → Cis_2 − B3_A | −25.90 | −16.27 |

| Cis_2 + B3_B → Cis_2 − B3_B | −26.46 | −16.84 |

| Cis_2 + B3_C → Cis_2 − B3_C | −24.94 | −15.31 |

| Cis_2 + B3_D → Cis_2 − B3_D | −23.51 | −13.89 |

| Car_1 + A → Car_1 − A | −27.08 | −17.02 |

| Car_1 + G → Car_1 − G | −34.66 | −24.59 |

| Car_1 + B3_A → Car_1 − B3_A | −25.61 | −9.27 |

| Car_1 + B3_B → Car_1 − B3_B | −25.68 | −9.33 |

| Car_1 + B3_C → Car_1 − B3_C | −25.54 | −9.19 |

| Car_1 + B3_D → Car_1 − B3_D | −19.83 | −3.49 |

| Car_2 + A → Car_2 − A | −28.16 | −20.14 |

| Car_2 + G → Car_2 − G | −29.48 | −21.46 |

| Car_2 + B3_A → Car_2 − B3_A | −25.34 | −17.32 |

| Car_2 + B3_B → Car_2 − B3_B | −26.00 | −17.98 |

| Car_2 + B3_C → Car_2 − B3_C | −26.48 | −18.46 |

| Car_2 + B3_D → Car_2 − B3_D | −20.21 | −12.19 |

| Oxa_1 + A → Oxa_1 − A | −27.36 | −18.26 |

| Oxa_1 + G → Oxa_1 − G | −31.22 | −22.12 |

| Oxa_1 + B3_A → Oxa_1 − B3_A | −20.68 | −11.57 |

| Oxa_1 + B3_B → Oxa_1 − B3_B | −26.58 | −17.48 |

| Oxa_1 + B3_C → Oxa_1 − B3_C | −26.18 | −17.08 |

| Oxa_1 + B3_D → Oxa_1 − B3_D | −15.44 | −6.34 |

| Oxa_2 + A → Oxa_2 − A | −25.05 | −16.85 |

| Oxa_2 + G → Oxa_2 − G | −32.92 | −24.72 |

| Oxa_2 + B3_A → Oxa_2 − B3_A | −24.67 | −16.47 |

| Oxa_2 + B3_B → Oxa_2 − B3_B | −24.80 | −16.59 |

| Oxa_2 + B3_C → Oxa_2 − B3_C | −24.78 | −16.58 |

| Oxa_2 + B3_D → Oxa_2 − B3_D | −20.42 | −12.22 |

| Property | Nucleobases (Adenine (A), Guanine (G)) | Pyridine Derivatives (B3_A, B3_B, B3_C, B3_D) | Platinum Hydrolysis Products (Cis_1, Car_1, Oxa_2, etc.) |

|---|---|---|---|

| HOMO Energy (EHOMO) | Significantly Higher Less Negative, (e.g., G ≈ −6.0 eV) | Lower (More Negative, e.g., B3_A ≈ −7.7 eV) | Generally lower than ligands. |

| Conclusion | These compounds are superior electron donors (nucleophiles). | Poorer electron donors compared to nucleobases. | |

| Electrophilicity (ω) | Lower (e.g., G ≈ 13.7 eV). | Higher (e.g., B3_D ≈ 33.4). | Significantly Highest (e.g., Cis_2). |

| Conclusion | Weaker electrophiles. | Weaker electrophiles compared to Pt-drugs. | Strong electrophiles (electron acceptors). |

| Energy Gap (ΔEgap) | High (5.8–5.9 eV). | High (5.8–6.2 eV). | Significantly Lowest (4.3–4.5 eV). |

| Structure | B3LYP/6-31G(d,p)/LANL2DZ | MN15/def2-TZVP | Experimental Data | Experimental Data from Literature |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A (Adenina) | 237.2 | 234.0 | 218.0; 264.0 | 220.0; 260.0 [64,65] |

| G (Guanina) | 232.5 | 227.8 | 219.00; 260.0 | 219.0; 249.0; 270.0 [64,65,66] |

| B3_A Nicotinic acid (3-pyridinecarboxylic acid) | 241.0 | 238.0 | 236.0; 263.0 | 215.0; 260.0 [67] |

| B3_B Nicotinamide (pyridine-3-carboxamide) | 252.4 | 244.6 | 239.0; 262.0 | 215.0; 265.0 [68] |

| B3_C Isonicotinic acid (pyridine-4-carboxylic) | 256.1 | 245.8 | 237.0; 268.0 | 215.0; 260.0 [69] |

| B3_D Picolinic acid (pyridine-2-carboxylic) | 239.8 | 229.0; 266.8 | 236.0; 268.0 | 228.0; 245.0; 265.0 [70,71] |

| Car | 219.0; 275.0 | 220.0; 270.0 [51,72] | ||

| Cis | 219.0, 276.0 | 207.0; 275.0 [73] | ||

| Oxa | 218.0, 274.0 | 210.0; 260.0 [72] | ||

| Car_A | 219.0; 262.0 | |||

| Car_G | 219; 260.0 | |||

| Cis_A | 218.0; 265.0 | |||

| Cis_G | 220.0; 265.0 | |||

| Oxa_A | 220.0; 263.0 | |||

| Oxa_G | 218.0; 270.0 | |||

| Car-B3_A | 221.0; 250; 297.0 | |||

| Car-B3_B | 222.0; 255.0 | |||

| Car-B3_C | 219.0; 264.0 | |||

| Car-B3_D | 222.0; 264.0 | |||

| Cis-B3_A | 221.0; 262.0 | |||

| Cis-B3_B | 223.0; 262.0 | |||

| Cis-B3_C | 219.0; 266.0 | |||

| Cis-B3_D | 220.0; 264.0 | |||

| Oxa-B3_A | 237.0; 263.0 | |||

| Oxa-B3_B | 222.0; 261.0 | |||

| Oxa-B3_C | 236.0; 267.0 | |||

| Oxa-B3_D | 220.0; 264.0 | |||

| Car_1 | 560.7 | 523.3 | ||

| Car_2 | 582.9 | 505.8 | ||

| Car_1_A | 310.4 | 289.7 | ||

| Car_1_G | 305.0 | 260.2 | ||

| Car_2_A | 280.8 | 262.6 | ||

| Car_2_G | 276.2 | 266.3 | ||

| Car_1-B3_A | 292.8 | 279.2 | ||

| Car_1-B3_B | 294.4 | 279.2 | ||

| Car_1-B3_C | 290.4 | 284.8 | ||

| Car_1-B3_D | 294.4 | 297.7 | ||

| Car_2-B3_A | 357.4 | 297.6 | ||

| Car_2-B3_B | 340.3 | 299.2 | ||

| Car_2-B3_C | 376.0 | 374.0; 291.0 | ||

| Car_2-B3_D | 367.0 | 352.0 | ||

| Cis_1 | 489.6 | 463.7 | ||

| Cis_2 | 555.0 | 405.0; 520.2 | ||

| Cis_1_A | 316.6 | 287.4 | ||

| Cis_1_G | 319.2 | 286.8 | ||

| Cis_2_A | 306.1 | 289.7 | ||

| Cis_2_G | 306.1 | 292.5 | ||

| Cis_1-B3_A | 309.6 | 292.4 | ||

| Cis_1-B3_B | 310.4 | 283.3 | ||

| Cis_1-B3_C | 331.2 | 303.2 | ||

| Cis_1-B3_D | 334.0 | 303.7 | ||

| Cis_2-B3_A | 316.0 | 284.8 | ||

| Cis_2-B3_B | 320.8 | 270.1 | ||

| Cis_2-B3_C | 301.6 | 295.3 | ||

| Cis_2-B3_D | 334.0 | 303.0 | ||

| Oxa 1 | 457.3 | 428.1 | ||

| Oxa 2 | 555.0 | 514.1 | ||

| Oxa 1 A | 315.8 | 289.8 | ||

| Oxa 1 G | 301.1 | 283.2 | ||

| Oxa 2 A | 309.6 | 285.3 | ||

| Oxa 2 G | 308.0 | 260.3 | ||

| Oxa_1-B3_A | 309.6 | 292.5 | ||

| Oxa_1-B3_B | 310.4 | 288.3 | ||

| Oxa_1-B3_C | 331.2 | 303.2 | ||

| Oxa_1-B3_D | 334.0 | 303.7 | ||

| Oxa_2-B3_A | 316.0 | 284.8 | ||

| Oxa_2-B3_B | 320.8 | 270.1 | ||

| Oxa_2-B3_C | 301.6 | 295.3 | ||

| Oxa_2-B3_D | 334.0 | 303.0 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Szefler, B.; Szupryczyński, K.; Czeleń, P. Platinum Meets Pyridine: Affinity Studies of Pyridinecarboxylic Acids and Nicotinamide for Platinum—Based Drugs. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 11875. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262411875

Szefler B, Szupryczyński K, Czeleń P. Platinum Meets Pyridine: Affinity Studies of Pyridinecarboxylic Acids and Nicotinamide for Platinum—Based Drugs. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2025; 26(24):11875. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262411875

Chicago/Turabian StyleSzefler, Beata, Kamil Szupryczyński, and Przemysław Czeleń. 2025. "Platinum Meets Pyridine: Affinity Studies of Pyridinecarboxylic Acids and Nicotinamide for Platinum—Based Drugs" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 26, no. 24: 11875. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262411875

APA StyleSzefler, B., Szupryczyński, K., & Czeleń, P. (2025). Platinum Meets Pyridine: Affinity Studies of Pyridinecarboxylic Acids and Nicotinamide for Platinum—Based Drugs. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 26(24), 11875. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262411875