Critical Systematic Review of 3D Bioprinting in Biomedicine

Abstract

1. Introduction

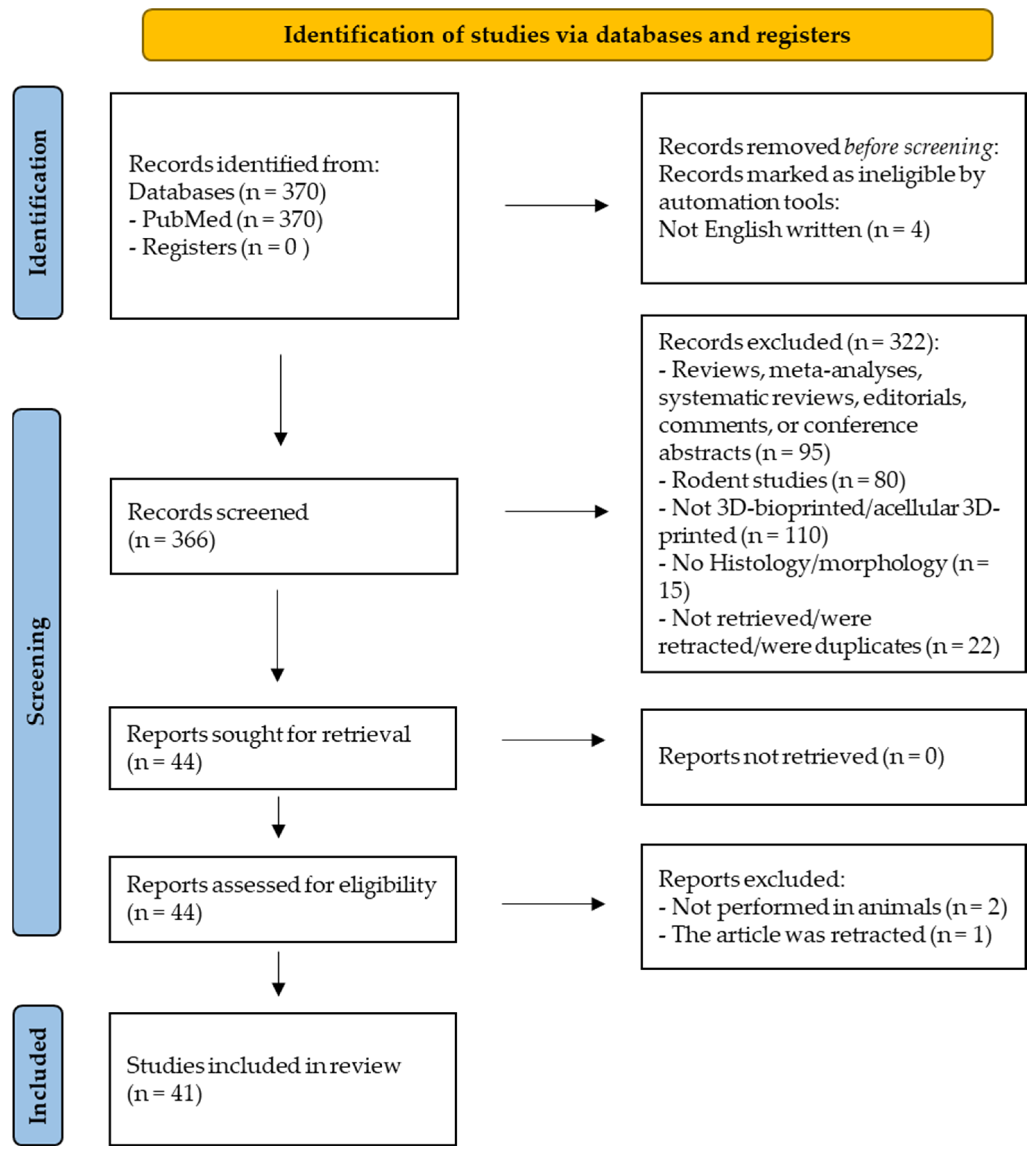

2. Methods

2.1. Prisma Guidelines and PROSPERO Registration

2.2. Search Request

2.3. Study Selection

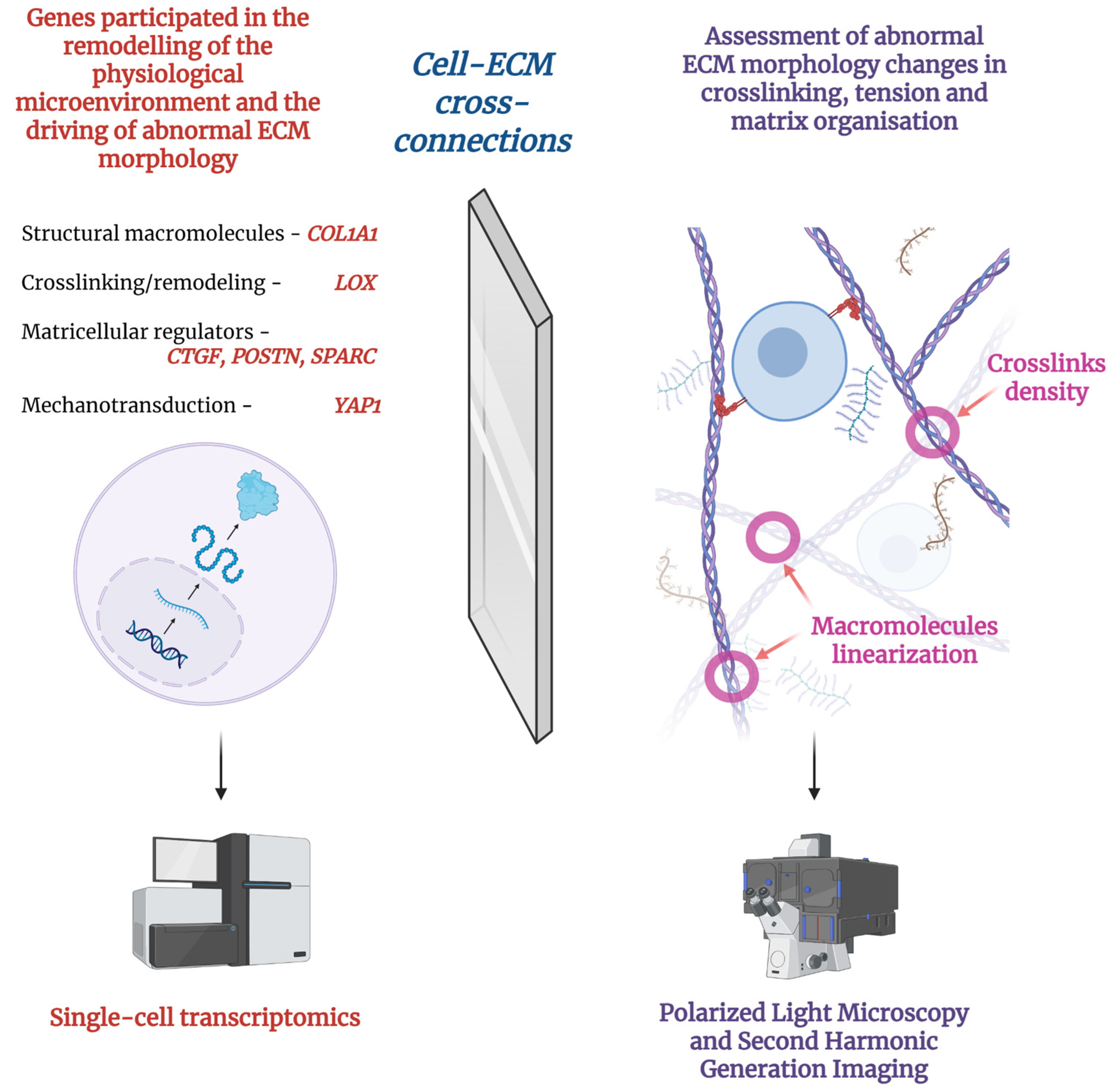

2.4. Outcomes Assessment

2.5. Data Extraction

2.6. Assessment of Risk of Bias in Individual Studies

2.7. Synthesis Methods

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AI | Artificial Intelligence |

| IHC | Immunohistochemistry |

| H&E | Hematoxylin and Eosin |

| SHG | Second Harmonic Generation |

References

- Bertassoni, L.E. Bioprinting of Complex Multicellular Organs with Advanced Functionality—Recent Progress and Challenges Ahead. Adv. Mater. 2022, 34, 2101321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klebe, R.J. Cytoscribing: A method for micropositioning cells and the construction of two-and three-dimensional synthetic tissues. Exp. Cell Res. 1988, 179, 362–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mironov, V.; Reis, N.; Derby, B. Bioprinting: A beginning. Tissue Eng. 2006, 12, 631–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhan, Y.; Jiang, W.; Liu, Z.; Wang, Z.; Guo, K.; Sun, J. Utilizing bioprinting to engineer spatially organized tissues from the bottom-up. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2024, 15, 101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahranavard, M.; Sarkari, S.; Safavi, S.; Ghorbani, F. Three-dimensional bio-printing of decellularized extracellular matrix-based bio-inks for cartilage regeneration: A systematic review. Biomater. Transl. 2022, 3, 105. [Google Scholar]

- Sztankovics, D.; Moldvai, D.; Petővári, G.; Gelencsér, R.; Krencz, I.; Raffay, R.; Dankó, T.; Sebestyén, A. 3D bioprinting and the revolution in experimental cancer model systems—A review of developing new models and experiences with in vitro 3D bioprinted breast cancer tissue-mimetic structures. Pathol. Oncol. Res. 2023, 29, 1610996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garciamendez-Mijares, C.E.; Agrawal, P.; García Martínez, G.; Cervantes Juarez, E.; Zhang, Y.S. State-of-art affordable bioprinters: A guide for the DiY community. Appl. Phys. Rev. 2021, 8, 031312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiorini, E.; Veghini, L.; Corbo, V. Modeling cell communication in cancer with organoids: Making the complex simple. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2020, 8, 166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hautefort, I.; Poletti, M.; Papp, D.; Korcsmaros, T. Everything you always wanted to know about organoid-based models (and never dared to ask). Cell. Mol. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2022, 14, 311–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandrycky, C.; Wang, Z.; Kim, K.; Kim, D.H. 3D bioprinting for engineering complex tissues. Biotechnol. Adv. 2016, 34, 422–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Datta, P.; Ayan, B.; Ozbolat, I.T. Bioprinting for vascular and vascularized tissue biofabrication. Acta Biomater. 2017, 51, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grover, H.; Spatarelu, C.-P.; De’DE’, K.; Zhao, S.; Yang, K.; Zhang, Y.S.; Chen, Z. Vascularization in 3D printed tissues: Emerging technologies to overcome longstanding obstacles. AIMS Cell Tissue Eng. 2018, 2, 163–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pu, X.; Wu, Y.; Liu, J.; Wu, B. 3D Bioprinting of Microbial-based Living Materials for Advanced Energy and Environmental Applications. Chem. Bio Eng. 2024, 1, 568–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chimene, D.; Lennox, K.K.; Kaunas, R.R.; Gaharwar, A.K. Advanced Bioinks for 3D Printing: A Materials Science Perspective. Ann. Biomed. Eng. 2016, 44, 2090–2102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dwijaksara, N.L.B.; Andromeda, S.; Rahmaning Gusti, A.W.; Siswanto, P.A.; Lestari Devi, N.L.P.M.; Sri Arnita, N.P. Innovations in Bioink Materials and 3D Bioprinting for Precision Tissue Engineering. Metta J. Ilmu Multidisiplin. 2024, 4, 101–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matai, I.; Kaur, G.; Seyedsalehi, A.; McClinton, A.; Laurencin, C.T. Progress in 3D bioprinting technology for tissue/organ regenerative engineering. Biomaterials 2020, 226, 119536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morouço, P.; Azimi, B.; Milazzo, M.; Mokhtari, F.; Fernandes, C.; Reis, D.; Danti, S. Four-Dimensional (Bio-)printing: A Review on Stimuli-Responsive Mechanisms and Their Biomedical Suitability. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 9143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashammakhi, N.; Ahadian, S.; Zengjie, F.; Suthiwanich, K.; Lorestani, F.; Orive, G.; Ostrovidov, S.; Khademhosseini, A. Advances and Future Perspectives in 4D Bioprinting. Biotechnol. J. 2018, 13, e1800148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, G.H.; Yeo, M.; Koo, Y.W.; Kim, G.H. 4D Bioprinting: Technological Advances in Biofabrication. Macromol. Biosci. 2019, 19, e1800441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Irvine, S.A.; Venkatraman, S.S. Bioprinting and Differentiation of Stem Cells. Molecules 2016, 21, 1188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ullah, M.W.; Ul-Islam, M.; Shehzad, A.; Manan, S.; Islam, S.U.; Fatima, A.; Al-Saidi, A.K.; Nokab, M.E.H.E.; Sanchez, J.Q.; Sebakhy, K.O. From Bioinks to Functional Tissues and Organs: Advances, Challenges, and the Promise of 3D Bioprinting. Macromol. Mater. Eng. 2025, e00251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lam, E.H.Y.; Yu, F.; Zhu, S.; Wang, Z. 3D Bioprinting for Next-Generation Personalized Medicine. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 6357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, B.; Yang, Q.; Zhao, X.; Jin, G.; Ma, Y.; Xu, F. 4D Bioprinting for Biomedical Applications. Trends Biotechnol. 2016, 34, 746–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falmagne, J.C.; Doignon, J.P. Learning Spaces: Interdisciplinary Applied Mathematics; Springer Science & Business Media: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Dondossola, E.; Friedl, P. Host responses to implants revealed by intravital microscopy. Nat. Rev. Mater. 2022, 7, 6–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rousselle, S.D.; Ramot, Y.; Nyska, A.; Jackson, N.D. Pathology of bioabsorbable implants in preclinical studies. Toxicol. Pathol. 2019, 47, 358–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, S.Y.; Choi, J.W.; Park, J.-K.; Song, E.H.; A Park, S.; Kim, Y.S.; Shin, Y.S.; Kim, C.-H. Tissue-engineered artificial oesophagus patch using three-dimensionally printed polycaprolactone with mesenchymal stem cells: A preliminary report. Interact. Cardiovasc. Thorac. Surg. 2016, 22, 712–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, G.; Li, S.; Yu, K.; He, B.; Hong, J.; Xu, T.; Meng, J.; Ye, C.; Chen, Y.; Shi, Z.; et al. A 3D-printed PRP-GelMA hydrogel promotes osteochondral regeneration through M2 macrophage polarization in a rabbit model. Acta Biomater. 2021, 128, 150–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, W.; Sun, M.; Hu, X.; Ren, B.; Cheng, J.; Li, C.; Duan, X.; Fu, X.; Zhang, J.; Chen, H.; et al. Structurally and Functionally Optimized Silk-Fibroin-Gelatin Scaffold Using 3D Printing to Repair Cartilage Injury In Vitro and In Vivo. Adv. Mater. 2017, 29, 1701089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, X.; Zhou, W.; Tang, Z.; Wu, H.; Liu, Y.; Dong, H.; Wang, N.; Huang, H.; Bao, S.; Shi, L.; et al. Magnesium surface-activated 3D printed porous PEEK scaffolds for in vivo osseointegration by promoting angiogenesis and osteogenesis. Bioact. Mater. 2022, 20, 16–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, L.; Tianyuan, Z.; Zhen, Y.; Fuyang, C.; Jiang, W.; Zineng, Y.; Zhengang, D.; Shuyun, L.; Chunxiang, H.; Zhiguo, Y.; et al. Biofabrication of cell-free dual drug-releasing biomimetic scaffolds for meniscal regeneration. Biofabrication 2021, 14, 015001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamimi, F.; Comeau, P.; Le Nihouannen, D.; Zhang, Y.; Bassett, D.; Khalili, S.; Gbureck, U.; Tran, S.; Komarova, S.; Barralet, J. Perfluorodecalin and bone regeneration. Eur. Cell Mater. 2013, 25, 22–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.H.; Seo, Y.B.; Yeon, Y.K.; Lee, Y.J.; Park, H.S.; Sultan, T.; Lee, J.M.; Lee, J.S.; Lee, O.J.; Hong, H.; et al. 4D-bioprinted silk hydrogels for tissue engineering. Biomaterials 2020, 260, 120281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Torsello, M.; Salvati, A.; Borro, L.; Meucci, D.; Tropiano, M.L.; Cialente, F.; Secinaro, A.; Del Fattore, A.; Emiliana, C.M.; Francalanci, P.; et al. 3D bioprinting in airway reconstructive surgery: A pilot study. Int. J. Pediatr. Otorhinolaryngol. 2022, 161, 111253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teotia, A.K.; Dienel, K.E.; Qayoom, I.; van Bochove, B.; Gupta, S.; Partanen, J.; Seppälä, J.V.; Kumar, A. Improved Bone Regeneration in Rabbit Bone Defects Using 3D Printed Composite Scaffolds Functionalized with Osteoinductive Factors. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2020, 12, 48340–48356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adamo, F.; Farina, M.; Thekkedath, U.R.; Grattoni, A.; Sesana, R. Mechanical characterization and numerical simulation of a subcutaneous implantable 3D printed cell encapsulation system. J. Mech. Behav. Biomed. Mater. 2018, 82, 133–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, B.; Wang, J.; Xie, M.; Xu, M.; Zhang, Y.; Hao, H.; Xing, X.; Lu, W.; Han, Q.; Liu, W. 3D printed biomimetic epithelium/stroma bilayer hydrogel implant for corneal regeneration. Bioact. Mater. 2022, 17, 234–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, J.; Yan, Y.; Gao, J.; Li, Y.; Wang, R.; Wang, J.; Zou, Q.; Zuo, Y.; Zhu, M.; Li, J. 3D-printed hydroxyapatite microspheres reinforced PLGA scaffolds for bone regeneration. Biomater. Adv. 2022, 133, 112618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, H.; You, Z.; Yan, X.; Liu, W.; Nan, Z.; Xing, D.; Huang, C.; Du, Y. TGase-Enhanced Microtissue Assembly in 3D-Printed-Template-Scaffold (3D-MAPS) for Large Tissue Defect Reparation. Adv. Healthc. Mater. 2020, 9, e2000531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiesa-Estomba, C.M.; Hernáez-Moya, R.; Rodiño, C.; Delgado, A.; Fernández-Blanco, G.; Aldazabal, J.; Paredes, J.; Izeta, A.; Aiastui, A. Ex Vivo Maturation of 3D-Printed, Chondrocyte-Laden, Polycaprolactone-Based Scaffolds Prior to Transplantation Improves Engineered Cartilage Substitute Properties and Integration. Cartilage 2022, 13, 105–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Chen, W.; Chen, Z.; Li, Y.; Wu, K.; Song, Y. Preparation of 3D Printing PLGA Scaffold with BMP-9 and P-15 Peptide Hydrogel and Its Application in the Treatment of Bone Defects in Rabbits. Contrast Media Mol. Imaging 2022, 2022, 1081957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, G.; Dong, H.; Wu, R.; Wang, J.; Ao, Y.; Xu, Y. 3D-printed regenerative polycaprolactone/silk fibroin osteogenic and chondrogenic implant for treatment of hip dysplasia. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2022, 636 Pt 1, 96–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fang, D.; Roskies, M.; Abdallah, M.N.; Bakkar, M.; Jordan, J.; Lin, L.-C.; Tamimi, F.; Tran, S.D. Three-Dimensional Printed Scaffolds with Multipotent Mesenchymal Stromal Cells for Rabbit Mandibular Reconstruction and Engineering. Methods Mol. Biol. 2017, 1553, 273–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, D.; Jin, D.; Wang, Q.; Gao, M.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, H.; Bai, J.; Feng, B.; Chen, M.; Huang, Y.; et al. Tissue-engineered trachea from a 3D-printed scaffold enhances whole-segment tracheal repair in a goat model. J. Tissue Eng. Regen. Med. 2019, 13, 694–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Tang, J.; Sun, L.; Zheng, T.; Pu, X.; Chen, Y.; Yang, K. Three-dimensional printed tissue engineered bone for canine mandibular defects. Genes Dis. 2019, 7, 138–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, C.; Attarilar, S.; Li, K.; Wang, C.; Liu, J.; Wang, L.; Yang, J.; Tang, Y. 3D-printed HA15-loaded β-Tricalcium Phosphate/Poly (Lactic-co-glycolic acid) Bone Tissue Scaffold Promotes Bone Regeneration in Rabbit Radial Defects. Int. J. Bioprint. 2021, 7, 317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, Y.; Gao, C.; Liu, H.; Liu, H.; Feng, Y.; Li, Z.; Liu, H.; Wang, J.; Yang, B.; Lin, Q. Infliximab-based self-healing hydrogel composite scaffold enhances stem cell survival, engraftment, and function in rheumatoid arthritis treatment. Acta Biomater. 2021, 121, 653–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, R.; Cheng, W.; Liu, H.; Luo, R.; Zou, H.; Zhang, L.; Ren, T.; Xu, C. Effect of Mechanical Loading on Bone Regeneration in HA/β-TCP/SF Scaffolds Prepared by Low-Temperature 3D Printing In Vivo. ACS Biomater. Sci. Eng. 2023, 9, 4980–4993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, Y.; Gong, J.; Lu, K.; Hong, Y.; Zhu, Z.; Zhang, J.; Zou, Y.; Zhou, F.; Zhang, C.; Zhou, S.; et al. DLP printed hDPSC-loaded GelMA microsphere regenerates dental pulp and repairs spinal cord. Biomaterials 2023, 299, 122137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oh, G.-W.; Nguyen, V.-T.; Heo, S.-Y.; Ko, S.-C.; Kim, C.S.; Park, W.S.; Choi, I.-W.; Jung, W.-K. 3D PCL/fish collagen composite scaffolds incorporating osteogenic abalone protein hydrolysates for bone regeneration application: In vitro and in vivo studies. J. Biomater. Sci. Polym. Ed. 2021, 32, 355–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Wu, Q.; Gao, F.; Wei, Y.; Ma, Y.; Jiang, W.; Dai, K. 3D-bioprinting ready-to-implant anisotropic menisci recapitulate healthy meniscus phenotype and prevent secondary joint degeneration. Theranostics 2021, 11, 5160–5173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, L.; Li, J.; Zhang, J.; Pan, Z.; Liu, Y.; Zhou, F.; Hong, Y.; Hu, Y.; Gu, Y.; Ouyang, H.; et al. An interleukin-4-loaded bi-layer 3D printed scaffold promotes osteochondral regeneration. Acta Biomater. 2020, 117, 246–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, M.; Feng, Z.; Guo, W.; Yang, D.; Gao, S.; Li, Y.; Shen, S.; Yuan, Z.; Huang, B.; Zhang, Y.; et al. PCL-MECM-Based Hydrogel Hybrid Scaffolds and Meniscal Fibrochondrocytes Promote Whole Meniscus Regeneration in a Rabbit Meniscectomy Model. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2019, 11, 41626–41639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, P.; Cui, L.; Chen, G.; You, T.; Li, W.; Zuo, J.; Wang, C.; Zhang, W.; Jiang, C. The application of BMP-12-overexpressing mesenchymal stem cells loaded 3D-printed PLGA scaffolds in rabbit rotator cuff repair. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2019, 138, 79–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.H.; Jung, S.Y.; Lee, C.; Ban, M.J.; Lee, S.J.; Kim, H.Y.; Oh, H.J.; Kim, B.K.; Park, H.S.; Jang, S.; et al. A 3D-printed polycaprolactone/β-tricalcium phosphate mandibular prosthesis: A pilot animal study. Laryngoscope 2020, 130, 358–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.-Y.; Ahn, G.; Kim, C.; Lee, J.-S.; Lee, I.-G.; An, S.-H.; Yun, W.-S.; Kim, S.-Y.; Shim, J.-H. Synergistic Effects of Beta Tri-Calcium Phosphate and Porcine-Derived Decellularized Bone Extracellular Matrix in 3D-Printed Polycaprolactone Scaffold on Bone Regeneration. Macromol. Biosci. 2018, 18, e1800025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, S.; Shi, Y.; Zhang, X.; Ma, J. Evaluation of BMP-2 and VEGF loaded 3D printed hydroxyapatite composite scaffolds with enhanced osteogenic capacity in vitro and in vivo. Mater. Sci. Eng. C Mater. Biol. Appl. 2020, 112, 110893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, J.; Huang, J.; Jin, J.; Xie, C.; Xue, B.; Lai, J.; Cheng, B.; Li, L.; Jiang, Q. The Design and Characterization of a Strong Bio-Ink for Meniscus Regeneration. Int. J. Bioprint. 2022, 8, 600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bae, S.-W.; Lee, K.-W.; Park, J.-H.; Lee, J.; Jung, C.-R.; Yu, J.; Kim, H.-Y.; Kim, D.-H. 3D Bioprinted Artificial Trachea with Epithelial Cells and Chondrogenic-Differentiated Bone Marrow-Derived Mesenchymal Stem Cells. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 1624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, F.; Fan, X.; Wu, H.; Ou, Y.; Zhao, X.; Chen, T.; Qian, Y.; Kang, H. Mastoid obliteration and external auditory canal reconstruction using 3D printed bioactive glass S53P4/polycaprolactone scaffold loaded with bone morphogenetic protein-2: A simulation clinical study in rabbits. Regen. Ther. 2022, 21, 469–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.-Z.; Wang, S.-J.; Zhang, J.-Y.; Jiang, W.-B.; Huang, A.-B.; Qi, Y.-S.; Ding, J.-X.; Chen, X.-S.; Jiang, D.; Yu, J.-K. 3D-Printed Poly(ε-caprolactone) Scaffold Augmented with Mesenchymal Stem Cells for Total Meniscal Substitution: A 12- and 24-Week Animal Study in a Rabbit Model. Am. J. Sports Med. 2017, 45, 1497–1511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.Y.; Choi, Y.J.; Shim, J.H.; Park, J.H.; Cho, D.W. Development of a 3D cell printed structure as an alternative to autologous cartilage for auricular reconstruction. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. B Appl. Biomater. 2017, 105, 1016–1028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huan, Y.; Zhou, D.; Wu, X.; He, X.; Chen, H.; Li, S.; Jia, B.; Dou, Y.; Fei, X.; Wu, S.; et al. 3D bioprinted autologous bone particle scaffolds for cranioplasty promote bone regeneration with both implanted and native BMSCs. Biofabrication 2023, 15, 025016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, P.; Li, Q.; Yang, Q.; Zhang, S.; Yi, K.; Zhang, G.; Tang, Z. Evaluation of the effect of 3D-bioprinted gingival fibroblast-encapsulated ADM scaffolds on keratinized gingival augmentation. J. Periodontal Res. 2023, 58, 564–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, J.-H.; Yoon, J.-K.; Lee, J.B.; Shin, Y.M.; Lee, K.-W.; Bae, S.-W.; Lee, J.; Yu, J.; Jung, C.-R.; Youn, Y.-N.; et al. Experimental Tracheal Replacement Using 3-dimensional Bioprinted Artificial Trachea with Autologous Epithelial Cells and Chondrocytes. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 2103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, D.; Wang, Y.; Yu, Z.; Wang, C.; Zhang, H.; Han, D.; Li, Q. Co-culture bioprinting of tissue-engineered bone-periosteum biphasic complex for repairing critical-sized skull defects in rabbits. Int. J. Bioprint. 2023, 9, 698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Liu, Y.; Zuo, Q.; Wang, Q.; Li, Z.; Yan, K.; Yuan, T.; Zhang, Y.; Shen, K.; Xie, R.; et al. 3D Bioprinting of Biomimetic Bilayered Scaffold Consisting of Decellularized Extracellular Matrix and Silk Fibroin for Osteochondral Repair. Int. J. Bioprint. 2021, 7, 401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baranovskii, D.S.; Klabukov, I.D.; Arguchinskaya, N.V.; Yakimova, A.O.; Kisel, A.A.; Yatsenko, E.M.; Ivanov, S.A.; Shegay, P.V.; Kaprin, A.D. Adverse events, side effects and complications in mesenchymal stromal cell-based therapies. Stem Cell Investig. 2022, 9, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kulakov, A.; Kogan, E.; Brailovskaya, T.; Vedyaeva, A.; Zharkov, N.; Krasilnikova, O.; Krasheninnikov, M.; Baranovskii, D.; Rasulov, T.; Klabukov, I. Mesenchymal Stromal Cells Enhance Vascularization and Epithelialization within 7 Days after Gingival Augmentation with Collagen Matrices in Rabbits. Dent. J. 2021, 9, 101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kovina, M.V.; Krasheninnikov, M.E.; Dyuzheva, T.G.; Danilevsky, M.I.; Klabukov, I.D.; Balyasin, M.V.; Chivilgina, O.K.; Lyundup, A.V. Human endometrial stem cells: High-yield isolation and characterization. Cytotherapy 2018, 20, 361–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saini, G.; Segaran, N.; Mayer, J.L.; Saini, A.; Albadawi, H.; Oklu, R. Applications of 3D Bioprinting in Tissue Engineering and Regenerative Medicine. J. Clin. Med. 2021, 10, 4966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kandasamy, M.; Vijayananth, K.; Parasuraman, A.; Ayrilmis, N. 3D Bioprinting of Biomaterials: A Review of Advances in Techniques, Materials, and Applications. Polym. Adv. Technol. 2025, 36, e70324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boularaoui, S.; Al Hussein, G.; Khan, K.A.; Christoforou, N.; Stefanini, C. An overview of extrusion-based bioprinting with a focus on induced shear stress and its effect on cell viability. Bioprinting 2020, 20, e00093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blaeser, A.; Duarte Campos, D.F.; Puster, U.; Richtering, W.; Stevens, M.M.; Fischer, H. Controlling Shear Stress in 3D Bioprinting is a Key Factor to Balance Printing Resolution and Stem Cell Integrity. Adv. Healthc. Mater. 2016, 5, 326–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Isaeva, E.V.; Beketov, E.E.; Yuzhakov, V.V.; Arguchinskaya, N.V.; Kisel, A.A.; Malakhov, E.P.; Lagoda, T.S.; Yakovleva, N.D.; Shegai, P.V.; Ivanov, S.A.; et al. The use of collagen with high concentration in cartilage tissue engineering by means of 3D-bioprinting. Cell Tissue Biol. 2021, 15, 493–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’cOnnell, C.D.; Di Bella, C.; Thompson, F.; Augustine, C.; Beirne, S.; Cornock, R.; Richards, C.J.; Chung, J.; Gambhir, S.; Yue, Z.; et al. Development of the Biopen: A handheld device for surgical printing of adipose stem cells at a chondral wound site. Biofabrication 2016, 8, 015019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Y.L.; Hu, J.; Genin, G.M.; Lu, T.J.; Xu, F. BioPen: Direct writing of functional materials at the point of care. Sci. Rep. 2014, 4, 4872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S. Animal models of cancer in the head and neck region. Clin. Exp. Otorhinolaryngol. 2009, 2, 55–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mauro, R.S.; Zotarelli-Filho, I.J. 3D bioprinting strategies and their application in studies in vivo and in vitro animal models for skin regeneration: A concise systematic review and meta-analysis. MedNEXT J. Med. Health Sci. 2023, 4, e23206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albanna, M.; Binder, K.W.; Murphy, S.V.; Kim, J.; Qasem, S.A.; Zhao, W.; Tan, J.; El-Amin, I.B.; Dice, D.D.; Marco, J.; et al. In situ bioprinting of autologous skin cells accelerates wound healing of extensive excisional full-thickness wounds. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 1856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shestakova, V.A.; Klabukov, I.D.; Baranovskii, D.S.; Shegay, P.V.; Kaprin, A.D. Assessment of immunological responses-a novel challenge in tissue engineering and regenerative medicine. Biomed. Res. Ther. 2022, 9, 5384–5386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazlouskaya, V.; Malhotra, S.; Lambe, J.; Idriss, M.H.; Elston, D.; Andres, C. The utility of elastic Verhoeff-Van Gieson staining in dermatopathology. J. Cutan. Pathol. 2013, 40, 211–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horny, L.; Kronek, J.; Chlup, H.; Zitny, R.; Vesely, J.; Hulan, M. Orientations of collagen fibers in aortic histological section. Bull. Appl. Mech. 2010, 6, 25–29. [Google Scholar]

- Jadidi, M.; Sherifova, S.; Sommer, G.; Kamenskiy, A.; Holzapfel, G.A. Constitutive modeling using structural information on collagen fiber direction and dispersion in human superficial femoral artery specimens of different ages. Acta Biomater. 2021, 121, 461–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quinn, K.P.; Golberg, A.; Broelsch, G.F.; Khan, S.; Villiger, M.; Bouma, B.; Austen, W.G.; Sheridan, R.L.; Mihm, M.C.; Yarmush, M.L.; et al. An automated image processing method to quantify collagen fibre organization within cutaneous scar tissue. Exp. Dermatol. 2015, 24, 78–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, C.; Jia, Z.; Liu, S.; Liao, X.; Kang, H.; Niu, X.; Fan, Y. Evolutionary Patterns of Collagen Fiber Arrangement and Calcification in Atherosclerosis. Research 2025, 8, 0798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Gulick, L.; Saby, C.; Jaisson, S.; Okwieka, A.; Gillery, P.; Dervin, E.; Morjani, H.; Beljebbar, A. An integrated approach to investigate age-related modifications of morphological, mechanical and structural properties of type I collagen. Acta Biomater. 2022, 137, 64–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Traini, T.; Degidi, M.; Strocchi, R.; Caputi, S.; Piattelli, A. Collagen fiber orientation near dental implants in human bone: Do their organization reflect differences in loading? J. Biomed. Mater. Res. B Appl. Biomater. 2005, 74, 538–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jan, N.J.; Lathrop, K.; Sigal, I.A. Collagen Architecture of the Posterior Pole: High-Resolution Wide Field of View Visualization and Analysis Using Polarized Light Microscopy. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2017, 58, 735–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, N.; Mirando, A.J.; Cofer, G.; Qi, Y.; Hilton, M.J.; Johnson, G.A. Characterization complex collagen fiber architecture in knee joint using high-resolution diffusion imaging. Magn. Reson. Med. 2020, 84, 908–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, B.; Lee, P.Y.; Hua, Y.; Brazile, B.; Waxman, S.; Ji, F.; Zhu, Z.; Sigal, I.A. Instant polarized light microscopy for imaging collagen microarchitecture and dynamics. J. Biophotonics 2021, 14, e202000326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Ding, J.; Zhang, H.; Li, M.; Lai, X. The Spatial Distribution of Renal Fibrosis Investigated by Micro-probe Terahertz Spectroscopy System. Diagnostics 2022, 12, 1602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Gulick, L.; Saby, C.; Mayer, C.; Fossier, E.; Jaisson, S.; Okwieka, A.; Gillery, P.; Chenais, B.; Mimouni, V.; Morjani, H.; et al. Biochemical and morpho-mechanical properties, and structural organization of rat tail tendon collagen in diet-induced obesity model. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 254 Pt 3, 127936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, C.Y.; Lee, J.K.; Chuck, R.S. Second Harmonic Generation Imaging Analysis of Collagen Arrangement in Human Cornea. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2015, 56, 5622–5629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pendleton, E.G.; Tehrani, K.F.; Barrow, R.P.; Mortensen, L.J. Second harmonic generation characterization of collagen in whole bone. Biomed. Opt. Express. 2020, 11, 4379–4396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Rao, Y.; Wong, S.H.; Wu, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Yang, R.; Tsui, S.K.; Ker, D.F.E.; Mao, C.; Frith, J.E.; et al. Transcriptome-Optimized Hydrogel Design of a Stem Cell Niche for Enhanced Tendon Regeneration. Adv. Mater. 2025, 37, e2313722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sancho, A.; Aldazabal, J.; Rainer, A.; De-Juan-Pardo, E.M. Rational Design of Artificial Cellular Niches for Tissue Engineering. In Tissue Engineering. Computational Methods in Applied Sciences; Fernandes, P., Bartolo, P., Eds.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2014; Volume 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansouri, M.; Leipzig, N.D. Advances in removing mass transport limitations for more physiologically relevant in vitro 3D cell constructs. Biophys. Rev. 2021, 2, 021305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martín, C.; Mojena, D.; Matesanz, A.; Velasco, D.; Acedo, P.; Jorcano, J.L. Smart biomaterials for skin tissue engineering and health monitoring. In New Trends in Smart Nanostructured Biomaterials in Health Sciences; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2023; pp. 211–258. [Google Scholar]

- Douglas, K. Bioprinting: To Make Ourselves Anew; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Klabukov, I.; Eygel, D.; Isaeva, E.; Kisel, A.; Isaev, E.I.; Potievskiy, M.; Atiakshin, D.; Shestakova, V.; Baranovskii, D.; Akhmedov, B.; et al. Synergistic Effects of Non-Ionizing Radiation in the Targeted Modification of Living Tissues. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 11415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arguchinskaya, N.V.; Beketov, E.E.; Kisel, A.A.; Isaeva, E.V.; Osidak, E.O.; Domogatsky, S.P.; Mikhailovsky, N.V.; Sevryukov, F.E.; Silantyeva, N.K.; Agababyan, T.A.; et al. The Technique of thyroid cartilage scaffold support formation for extrusion-based bioprinting. Int. J. Bioprint. 2021, 7, 348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, D.; Negi, N.P. 3D bioprinting: Printing the future and recent advances. Bioprinting 2022, 27, e00211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, E.; Rego, G.P.; Ghosh, R.N.; Sahithi, V.B.; Poojary, D.P.; Namboothiri, P.K.; Peter, M. Advances in In Situ Bioprinting: A Focus on Extrusion and Inkjet-Based Bioprinting Techniques. Regen. Eng. Transl. Med. 2025, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manzoli, S.; Merotto, E.; Piccoli, M.; Gobbo, P.; Todros, S.; Pavan, P.G. An Overview of 3D Bioprinting Impact on Cell Viability: From Damage Assessment to Protection Solutions. J. Funct. Biomater. 2025, 16, 436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, G.; Kim, S.J.; Jang, J. Multidisciplinary Approaches to Address Resolution, Scalability, and Geometric Constraints in Bioprinting. Int. J. Precis. Eng. Manuf. 2025, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakkungal, D.; Bhatt, A. 3D Bioprinting: A Comprehensive Review of 3D Bioprinting, Biomaterials, and Characterization Methods. Regen. Eng. Transl. Med. 2025, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramakrishnan, R.; Dinesan, A. Advantages and Disadvantages of 3D Bioprinting. In Compendium of 3D Bioprinting Technology; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2025; pp. 147–176. [Google Scholar]

- Gebeshuber, I.C.; Khawas, S.; Sharma, R.; Sharma, N. Bioprinted Scaffolds for Biomimetic Applications: A State-of-the-Art Technology. Biomimetics 2025, 10, 595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alparslan, C.; Bayraktar, Ş. Advances in digital light processing (DLP) bioprinting: A review of biomaterials and its applications, innovations, challenges, and future perspectives. Polymers 2025, 17, 1287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babayigit, C.; Tavares-Negrete, J.A.; Esfandyarpour, R.; Boyraz, O. High-resolution bioprinting of complex bio-structures via engineering of the photopatterning approaches and adaptive segmentation. Biofabrication 2025, 17, 025026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, H.; Zhang, X.; Yuan, X.; Lian, Z.; Xu, J.; Shan, D.; Guo, B. 3D Bioprinting Technology in Tissue Engineering Printing Method and Material Selection. BioNanoScience 2025, 15, 199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitana, W.; Apsite, I.; Ionov, L. 3D (Bio) Printing Combined Fiber Fabrication Methods for Tissue Engineering Applications: Possibilities and Limitations. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2025, 2500450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasouli, R.; Sweeney, C.; Frampton, J.P. Heterogeneous and composite bioinks for 3D-bioprinting of complex tissue. Biomed. Mater. Devices 2025, 3, 108–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teague, B.P.; Guye, P.; Weiss, R. Synthetic morphogenesis. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2016, 8, a023929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klabukov, I.; Smirnova, A.; Evstratova, E.; Baranovskii, D. Development of a biodegradable prosthesis through tissue engineering: The lack of the physiological abstractions prevents bioengineering innovations. Ann. Hepatol. 2025, 30, 101587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Faber, L.; Yau, A.; Chen, Y. Translational biomaterials of four-dimensional bioprinting for tissue regeneration. Biofabrication 2023, 16, 012001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arif, Z.U.; Khalid, M.; Ahmed, W.; Arshad, H. A review on four-dimensional (4D) bioprinting in pursuit of advanced tissue engineering applications. Bioprinting 2022, 27, e00203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alanazi, B.N.; Ahmed, H.A.; Alharbi, N.S.; Ebrahim, N.A.A.; Soliman, S.M.A. Exploring 4D printing of smart materials for regenerative medicine applications. RSC Adv. 2025, 15, 32155–32171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liew, A.W.L.; Zhang, A.Y. In vitro pre-vascularization strategies for tissue engineered constructs-Bioprinting and others. Int. J. Bioprint. 2017, 3, 008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yeo, M.; Sarkar, A.; Singh, Y.P.; Derman, I.D.; Datta, P.; Ozbolat, I.T. Synergistic coupling between 3D bioprinting and vascularization strategies. Biofabrication 2023, 16, 012003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jo, Y.; Hwang, D.G.; Kim, M.; Yong, U.; Jang, J. Bioprinting-assisted tissue assembly to generate organ substitutes at scale. Trends Biotechnol. 2023, 41, 93–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, B.; Dong, J.; Ruelas, M.; Ye, X.; He, J.; Yao, R.; Fu, Y.; Liu, Y.; Hu, J.; Wu, T.; et al. Artificial Intelligence-Assisted High-Throughput Screening of Printing Conditions of Hydrogel Architectures for Accelerated Diabetic Wound Healing. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2022, 32, 2201843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christou, C.D.; Tsoulfas, G. Role of three-dimensional printing and artificial intelligence in the management of hepatocellular carcinoma: Challenges and opportunities. World J. Gastrointest. Oncol. 2022, 14, 765–793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| General Direction | Methods |

|---|---|

| Imaging and radiological assessment | 1. Microcomputed tomography (MicroCT) was used to assess bone tissue regeneration, providing quantitative data on bone tissue volume, density, and integration with the matrix. 2. Traditional CT and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) were used for larger structures: the trachea, mandible, and menisci. 3. Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) allowed for ultrastructural analysis of the grafts. |

| Histological and histomorphometric analysis | 1. Hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining was the main method used to evaluate tissue morphology. 2. Specialized stains such as safranin-O, Masson’s trichrome, Van Gieson’s stain, and Sirius red were used to detect proteoglycans in cartilage and collagen deposits. 3. Quantitative analysis of histological sections based on histomorphometry allowed measurement of the bone-implant contact ratio, tissue ingrowth area, and glycosaminoglycan (GAG) content. |

| Immunohistochemistry (IHC) | IHC was aimed at identifying specific tissue components and cell types with the following targets: 1. Collagen types I and II—differentiation of fibrous tissue from hyaline cartilage. 2. CD31—detection of vascular endothelial cells. 3. Osteocalcin—detection of bone tissue. 4. Macrophage markers (CD163, Arg1)—characterization of the immune response. |

| Biochemical assays | Quantitative determination of DNA, sulfated glycosaminoglycans (s-GAG), and total collagen content was used to assess the biochemical composition and quality of the regenerated tissue. |

| Biomechanical testing | Mechanical tests, including uniaxial compression, tensile testing, and push-out testing, were performed to investigate and evaluate the functional integration and strength of the tissue. |

| Immunological and cytokine analysis | Measurement of systemic or local levels of inflammatory cytokines (e.g., IL-1β, IL-6, TNF-α) by ELISA was used to assess the body’s immune response to the implant. |

| No. | Type of Bioprinted Tissue | Host Tissue and Animal Used | Technique of In Vivo Implantation | Evaluation of Outcomes | Refs. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 3D printing polycaprolactone-only scaffold and fibrin/mesenchymal stem cells-coated 3D printing polycaprolactone scaffolds | Femurs and tibias; New Zealand white rabbits | The prepared 3D-printed matrices were implanted into a 10 × 5 mm wedge-shaped defect in the cervical esophagus. | Computed tomography; Histology (hematoxylin and eosin); IHC with desmin staining to assess smooth muscle formation. | [28] |

| 2 | Platelet-rich plasma gelatin methacryloyl hydrogel scaffold | Bone and cartilage; Male New Zealand white rabbits | Prepared 3D-printed hydrogel scaffolds were implanted into the defects on the center of the distal articular cartilage of the femur on both sides of the knee. | The macroscopic samples (n = 5) were assessed according to the cartilage repair assessment tool; 3 samples were measured by a Micro-CT scanner; Histology (hematoxylin and eosin staining and Safranin-O fast green staining); IHC (Arg1, CD163, CCR7). | [29] |

| 3 | Affinity peptide E7 loaded onto the SF-gelatin scaffolds | Bone and cartilage; Adult male New Zealand white rabbits | 3D-printed material was injected into microfractured knee joints | Histology (H&E staining, toluidine blue staining); IHC (collagen type II); Quantification of inflammatory cytokines; Magnetic resonance imaging; Scanning electron microscope. | [30] |

| 4 | Porous polyether-ether-ketone cylinder shaped scaffolds with a diameter of 6 mm and a height of 10 mm were either immersed into (hydroxymethyl)aminomethane and dopamine solution or into (hydroxymethyl)aminomethane and MgCl2 solution | Bone and cartilage; Male New Zealand White rabbits | Bilateral femoral condylar bone defects were constructed and scaffold was inserted | Van Gieson’s staining was conducted by Stevenel’s blue and picric acid magenta dye solution. The optical microscope was used to observe sections after staining. The area of bone (stained with dark red) inside the scaffolds was measured and ratio of bone area and total scaffold area was also calculated. The bone-implant contact ratio was measured by calculating the ratio of the length of bone tissue which is directly contacted with the scaffolds to the total length of the surface of scaffolds. | [31] |

| 5 | Platelet-derived growth factor-BB, kartogenin, within biomimetic matrix scaffolds (composed of hyaluronic acid methacrylate, lithium phenyl-2,4,6-trimethylbenzoyl phosphinate and meniscal extracellular) | Bone and cartilage; Male New Zealand White rabbits | Major meniscectomy was performed and scaffold was inserted | Macroscopic evaluation using Osteoarthritis Research Society International grading for damaged cartilage and osteophyte development; Biochemical analysis (glycosaminoglycan and total collagen contents of the neomeniscus were assessed using a hydroxyproline assay kit (Nanjing Jiancheng, China) and a tissue GAG Total-Content DMMB Colorimetry Kit (GenMed, Shanghai, China); MRI (regenerations was also analyzed according to the Whole-Organ Magnetic Resonance Imaging Score (WORMS) system); Biomechanical testing (uniaxial mechanical testing machine); Histology (H&E, toluidine blue, sirius red); IHC (collagen 1 and collagen 2). | [32] |

| 6 | Calcium phosphate cements loaded with perfluorodecalin and autologous bone marrow | Bone; Adult New Zealand rabbits | A 1 cm long bone defect was created in each ulna after removing the periosteum from the site and 3D-printed specimens were implanted | Histology (H&E); Backscattered scanning electron microscopy; Histomorphometric analysis (assessing bone and soft tissue growth). | [33] |

| 7 | Digital light processing3D printed trachea made with silk fibroin and glycidyl methacrylate solution (Sil-MA) loaded with human chondrocytes (labeled with PKH26) and turbinate-derived mesenchymal stem cells (human or rabbit; labeled withPKH67) | Trachea; Male New Zealand white rabbits | A circumferential defect was cut into the anterior tracheal wall using a scalpel. A tissue-engineered trachea was then inserted and anastomosed. | Histology (H&E used to assess the tissue morphology; Safranin O staining used to assess the presence of proteoglycan-rich matrix; Masson’s trichrome staining used to detect collagen production). | [34] |

| 8 | Polycaprolactone laryngo-tracheal scaffold loaded with mesenchymal stem cells | Larynx and trachea; Female sheep | Laryngotracheal reconstruction surgery by cervicotomy and laryngofissure with implantation of two scaffolds, one in the laryngeal site and one in the tracheal site | Histology (H&E). | [35] |

| 9 | Poly(trimethylene carbonate) with tricalcium phosphate or hydroxyapatite-loaded either with cryogel or bone morphogenetic protein or zoledronic acid (and their different combinations) printed with stereolithography | Bone; Male New Zealand white rabbits (tibial defects) and Belgian white rabbits (cranial defects) | Tibial (near knee joints) and cranial defects (trephine on either side of midline with frontal and parietal bones receiving two defects each) | Micro-CT (quantitative morphometric analysis; mineralized bone volume, tissue mineralization, and scaffold-bone integration were assessed); Histology (H&E, Masson’s trichrome staining). | [36] |

| 10 | 3D printed polylactic acid system termed neovascularized implantable cell homing and encapsulation (filled with 300 μL platelet-rich plasma alginate hydrogel) | Subcutaneous tissue; Yucatan minipigs | Implants were implanted in the dorsum of Yucatan minipigs | Monotonic axial central compression tests; Histology (H&E and Picrosirius staining). | [37] |

| 11 | Gelatin methacrylate and long-chain poly(ethylene glycol) diacrylate blended and laden with L929 mouse fibroblast cells and rabbit corneal epithelial cells | Eye cornea; Adult male rabbits | Anterior lamellar keratoplasty was performed. Then scaffolds were punched with a trephine and carefully put on the corneal defect area with the printed epithelia layer facing upwards. | Slit lamp monitoring; Histology (H&E); IHC (cytokeratin 3, collagen type I, lumican, and alpha smooth muscle actin); Gene expression comparison (KERA, ALDH, AQP1 genes). | [38] |

| 12 | Hydroxyapatite/poly (lactic-co-glycolic acid) (HA/PLGA) three-dimensional porous scaffolds | Femoral condyle; New Zealand White rabbits | Grafts were implanted in the distal condyle of the femur on the right and left sides, in which a cylindrical bone defect (diameter—5.5 mm, depth—6 mm) was drilled. | Three-dimensional analysis using the vivaCT40 micro-CT system; Microtomographic data sets using direct 3D morphometry (visual assessment of structural images of bones and skeletons and morphometric parameters); Histology. | [39] |

| 13 | A rubber-like thermoplastic co-polyester, Flexifill, used to print template loaded with adipose-derived mesenchymal stem cells | Cartilage; Male New Zealand white rabbits | The incision was made along the auricular central arteriovenous branch and filled with a 3D template. | Micro-CT; Atomic force microscopy | [40] |

| 14 | Polycaprolactone scaffolds laden with rabbit auricular chondrocytes | Cartilage; Male New Zealand white rabbits. | A perichondrium pocket was designed (circle shape biopsy of elastic cartilage of 1 cm of diameter was extracted without penetrating the lateral skin). | Histology (glycosaminoglycan content was visualized by Alcian Blue-Safranin O staining); IHC (type I and type II collagens); Gene expression (ACAN, COL1A1, COL2A1, COL10A1, and SOX9); Scanning electron microscopy; Uniaxial compression tests | [41] |

| 15 | Polylactic acid glycolic acid scaffold with bone morphogenetic protein-9 and P-15 peptide hydrogel | Bone; Japanese big ear rabbits | The hole was created in the bone above the articular surface of the lateral condyle of the femur, then filled with the scaffold. | MicroCT; Gene expression (ALP, COL-1, OCN, RUNX2, and Sp7) | [42] |

| 16 | Osteogenic part (3D printed polycaprolactone crosslinked with dopamine; Chondrogenic part (silk fibroin loaded with bone morphogenetic protein 2) | Bone and cartilage; Mature New Zealand white rabbits | Defects were made in the acetabulum then filled with the implants | Histology (H&E), Safranin O-Fast Green, toluidine blue, and Masson’s trichrome); IHC (Collagen II, assessed semi-quantitatively with the use of a microscope and Image-Pro Plus software (Media Cybernetics, https://mediacy.com/image-pro/ accessed on 5 December 2025); the relative density (integral optical density/area) was calculated to semi-quantify the content of collagen II); CT; MRI; Unconfined compressive strength. | [43] |

| 17 | Bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stromal cells and adipose tissue-derived stem cells loaded onto 3D- printed scaffolds | Bone; Mature New Zealand male rabbits | Mandibular bone defect was created, then filled with the scaffold | Micro-CT. | [44] |

| 18 | Poly(caprolactone) scaffold loaded with goat autologous auricular cartilage cells | Trachea; Shanghai white goats | Goat native trachea (covering four full cartilage rings) was surgically excised and replaced by tissue-engineered trachea | Bronchoscopy; CT; Histology (H&E, toluidine blue, and Safranin O); IHC (type II collagen, cytokeratin); TUNEL staining (In Situ Cell Death Detection Kit; score for apoptotic cells). | [45] |

| 19 | Nanoporous hydroxyapatite implant loaded with autologous bone marrow stromal cells | Bone; Mature Beagles | Bone defect was created in the mandibules; the cell scaffold composite was placed in the defects and firmly fixed with titanium plates and titanium nails. | CT and micro-CT; Electron microscopy; Histology (methylene blue-acid fuchsin). | [46] |

| 20 | β-tricalcium phosphate /poly (lactic-co-glycolic acid) scaffold was loaded with HA15 (osteogenesis-promoting drug) | Bone; New Zealand white rabbits | Radial defects were made, then filled with the scaffold. | Micro-CT (assessing bone volume/total volume, bone mineral density, trabecular thickness, and the structural model index); Microfil-angiography. | [47] |

| 21 | 3D printed porous metal scaffolds filled with hyaluronic acid-hydrazide and hyaluronic acid-aldehyde, Infliximab and seeded with adipose-derived mesenchymal stem cells | Bone; 30-week-old female New Zealand white rabbits | A cylindrical defect in the femoral condyle was produced using a drill, the scaffold was implanted into the defect | Histology (H&E and Masson staining; qualitative analysis of bone in-growth); In vivo measurement of cytokines in serum at 3 months (IL-1β, IL-6, TNF-α, and OVA-Ab); Micro-CT; Push out test. | [48] |

| 22 | Hydroxyapatite/β tricalcium phosphate/silk fibroin scaffolds seeded with MC3T3-E1 cells (a mouse monoclonal preosteoblastic cell line from C57BL/6 mouse calvaria). | Bone; 6-month old New Zealand white rabbits | Scaffolds implanted into the proximal tibia | Micro-CT; Van Gieson’s staining without decalcification; IHC (Fluorescent double-labeling detection of subcutaneous injected tetracycline and calcein); Axial loading test in alive animals. | [49] |

| 23 | Human dental pulp stem cells laden onto the gelatin methacrylate scaffold. | Teeth; Female Panama minipigs | Scaffolds were implanted into the dental root canals, the corona was filled with resin. | Histology (H&E) | [50] |

| 24 | Poly (ε-caprolactone) scaffolds with fish collagen and the osteogenic abalone intestine gastro-intestinal digests from Haliotis discus hannai seeded with mouse mesenchymal stem cells. | Bone; Rabbits (not elaborated) | A bone tunnel of 2.1 mm in diameter created in the center of each tibia bone where the scaffolds were later implanted. | X-ray; Micro-CT (rate of new bone volume); Histology (H&E). | [51] |

| 25 | Poly(ε-caprolactone) molten to fabricate scaffolding structure with synovium-derived mesenchymal stem cells-laden hydrogel encapsulating poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid) microspheres carrying transforming growth factor, beta 3 or connective tissue growth factor and magnesium ions | Bone and cartilage; Rabbits (not elaborated). | Total medial meniscus was dissected, and the engineered meniscus construct was transplanted in situ. | IHC (CD31, alpha smooth muscle actin, collagen I, collagen II). | [52] |

| 26 | Bi-layer scaffold: an interleukin-4-loaded radially oriented gelatin methacrylate scaffold printed with digital light processing in the upper layer and a porous polycaprolactone and hydroxyapatite scaffold printed with fused deposition modeling in the lower layer | Bone; Adult male New Zealand white rabbits. | Osteochondral cylindrical cartilage defects were created on the patellar groove; the bi-layer scaffolds were then implanted. | Histology (safranin-O); Immunohistochemistry (COL2); Tensile-compressive testing; Micro-CT. | [53] |

| 27 | Poly(ε-caprolactone) scaffold as a backbone, followed by injection with the meniscus extracellular matrix | Bone and cartilage; Skeletally mature New Zealand White rabbits | Total medial meniscectomy except 5% of the external rim where scaffold was implanted | Meniscus covering rate; Histology (H&E; toluidine blue); IHC (collagen I, collagen II); GAG content assay; Compressive and tensile strengths; X-ray; MRI. | [54] |

| 28 | Bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells transfected with a recombinant adenovirus encoding bone morphogenic protein 12 and loaded onto polylactic-co-glycolic acid scaffolds | Tendon and bone; Adult rabbits (not elaborated) | Scaffolds placed in the interface between the supraspinatus tendon and bone | Biomechanical tension testing; Histology (H&E); Modified tendon maturing score (histological signs of fibrous tissue ingrowth, fibrocartilage cells and a tidemark). | [55] |

| 29 | Human tonsil-derived mesenchymal stem cells-laden polycaprolactone and beta-tricalcium phosphate scaffold | Bone 12-week old male New Zealand white rabbits | Bone defect in the middle portion of the inferior mandibular margin made with a surgical drill and osteotome and filled with scaffold | Conventional CT; Micro-CT (region of interest between the proximal and distal fixing screws within the scaffold); Mechanical compression assessment; Histology (H&E; Masson’s trichrome staining); IHC (CD31; anti-nuclei antibody). | [56] |

| 30 | Polycaprolactone beta-tricalcium phosphate scaffolds placed in porcine neutralized bone decellularized extracellular matrix | Bone; 12-week old male New Zealand white rabbits | Micro-CT (radiodensity analysis used to measure bone volume and density); Histology (H&E; Masson’s trichrome staining; Von Kossa staining). | [57] | |

| 31 | Hydroxyapatite loaded with bone morphogenic protein-2 and vascular endothelial growth factor. | Bone; New Zealand white rabbits | The scaffolds were implanted into the calvarian defects. | Micro-CT (bone volume to tissue volume, trabecular number); Histology (H&E); IHC (lectin; collagen type I) | [58] |

| 32 | Poly (vinyl alcohol) loaded with rabbit meniscal decellularized extracellular matrix. | Bone; Female New Zealand white rabbits | Circular defect was created in the central part of lateral meniscus and replaced with scaffold. | Macroscopic evaluation; Micro-MRI; Histology (H&E, toluidine blue, Safranin O); IHC (Collagen II). | [59] |

| 33 | Rabbit bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells (bMSC) and rabbit respiratory epithelial cells-laden polycaprolactone formed artificial trachea | Trachea; Male, 3-month-old New Zealand white rabbits | Half-pipe-shaped partial tracheal resection that was later replaced with an artificial trachea | Bronchoscopy; Conventional CT; Histology (H&E); Safranin-O/fast green). | [60] |

| 34 | Bone morphogenetic protein-2-loaded onto bioactive glass S53P4/ polycaprolactone scaffold. | Bone and cartilage; 5-month-old New Zealand rabbits | Outer 1/3 of the external auditory canal and the bone of the lateral wall of the auditory bulla area were abraded. Scaffold was implanted | Otolaryngoscopy; Micro-CT (region of interest, and the total volume, new bone volume, new bone volume fraction. | [61] |

| 35 | Poly(ε-caprolactone) scaffold laden with rabbit bone-marrow derived mesenchymal stem cells. | Bone and cartilage; Skeletally mature, male New Zealand White rabbits | Total meniscectomy was performed by resecting the medial meniscus sharply along the periphery and detaching it from its anterior and posterior junction. Scaffold was implanted | Gross evaluation (implant integration, implant position, horn position, shape, presence of tears in the implant, implant surface, implant size, tissue quality, and condition of the synovia); Synovial fluid analysis (IL-1, TNF-a; ELISA); Histology (H&E and toluidine blue); IHC (picrosirius red, collagen I, collagen II); Biomechanical testing (tensile testing, elastic modulus, confined compression testing). | [62] |

| 36 | Rabbit-ear primary chondrocytes-alginate bio-ink printed with polycaprolactone. | Cartilage; 12-week-old male New Zealand white rabbits | Circular defects were created using an 8 mm biopsy puncher in the proximal region of the rabbit ears | Histology (H&E; Alcian Blue); IHC (green fluorescent dye, labeled chondrocytes were observed under the confocal laser scanning microscope). | [63] |

| 37 | Beagle autologous bone and a bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cell hydrogel. | Bone; Beagle dogs | 2 cm diameter full-thickness cranial defect was made in the flat part of the head which was 2.5 cm to the right of the midline and 2.5 cm behind the anterior fontanelle. Scaffolds were implanted 3 months after the operation | Micro-CT (bone volume per tissue volume, trabecular number, trabecular spacing); CT; Histology (H&E, Masson’s trichrome staining, Safranine O-Fast green); IHC (TNF-α, IL-1β, collagen I, collagen II, aggrecan, osteocalcin, CD31, Col1, Col2, CD105, CD90, stromal cell-derived factor 1); SDF1 (ELISA). | [64] |

| 38 | Acellular porcine dermal matrix gelatin, sodium alginate combined with beagle dog gingival fibroblasts. | Bone and gingiva; Healthy male Beagles | Complexes were transplanted into the mandibular gingival defects | Histology (H&E, Masson and Sirius Red staining); IHC(collagen I, collagen III, vascular endothelial- derived growth factor-A). | [65] |

| 39 | Multi-layer structure including PCL layers, hydrogel layer with rabbit nasal epithelial cells and hydrogel layer with rabbit auricular cartilage cells | Trachea; Mature male New Zealand White rabbits | The ventral portion of the trachea was cut into a semi-cylindrical shape measuring approximately 1.5 × 1.5 cm, and the artificial trachea was put into place | X-ray; Respiration pattern assessment; Histology (H&E, Masson’s trichrome, and safranin O). | [66] |

| 40 | Poly-L-lactic acid/hydroxyapatite scaffold printed with rabbit bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells -laden and rabbit periosteum-derived stem cells-laden gelatin methacryl hydrogel | Bone; Male New Zealand White rabbits | Symmetrical 8 mm-diameter hole-shaped bone defects were established along the midline of the sutura cranii with a circular drill and filled with scaffolds | Micro-CT (regenerated bone volume, bone volume/total volume, trabecular number, trabecular thickness, and trabecular spacing); Histology (H&E, Masson’s trichrome); IHC (osteocalcin) | [67] |

| 41 | Rabbit bone marrow stem cells were used in decellularized bone extracellular matrix (loaded with bone morphogenetic protein-2) and in decellularized cartilage extracellular matrix (loaded with transforming growth factor-beta) combined with silk fibroin bioinks, polycaprolactone was used as a scaffold. | Bone; New Zealand white rabbits weighted 2.0–3.0 kg | Osteochondral defects were caused on the patellar groove of a right knee joint, scaffolds were implanted into the defects. | Histology (safranin O and Masson’s trichrome); IHC (collagen type II, osteocalcin); Biochemical analysis (collagen and sulfated- glycosaminoglycan). | [68] |

| Histological Technique | Spatial Scale Resolution, μm | Angular Resolution | Refs. |

|---|---|---|---|

| Van Gieson | 1–10 | Low (Qualitative) | [83,84,85] |

| Masson | 1–10 | Low (Qualitative) | [86,87] |

| Silver staining | 1–10 | Low (Qualitative) | [88,89] |

| Polarized light | 1–100 | High | [90,91,92] |

| Terahertz spectroscopy | 10–100 | Moderate | [93] |

| Second Harmonic Generation (SHG) Imaging | <1 (sub-micron) | Very High | [94,95,96] |

| Technique | Principle | Features of the Morphology of Bioprinted Structures | Effects on the Cell Fate and Physiological Relevancy | Refs. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Inkjet Bioprinting | A printing head is used to eject droplets of bioink onto a substrate. | Initial additive placement of various types of spheroids or tissue compartments with high spatial resolution. | Cell viability can be affected by shear stress and heat. | [105,106,107,108] |

| Laser-Assisted Bioprinting | A high-pressure bubble is generated using laser pulses, which propels small droplets of bioink toward a receiving substrate. | High printing precision and spatial resolution of formed constructs. | Cell regulation could be affected by combined irradiation and impulse pressure. | [106,109,110] |

| Stereolithography or Digital Light Processing Bioprinting | Photosensitive bioinks are photopolymerized by light (usually UV or visible) in a layer-by-layer process. | Extremely high resolution and smooth surface finish. Rapid printing time. Restricted to photo-crosslinkable bioinks. | Potential phototoxicity to cells if not carefully controlled. | [109,111,112] |

| Extrusion Bioprinting | Pneumatic, piston, and screw-driven systems are used to extrude continuous strands of bioink through a nozzle. | The resolution is lower compared to methods using inkjet or laser-assisted methods. | Shear stress occurs on cells during extrusion. | [105,113] |

| Electrospinning or electrohydrodynamic bioprinting | Fine fibers or droplets are drawn from a polymer solution or bioink using electric fields. | Nanofibrous scaffolds that mimic the ECM can be created. | Cell viability is often limited due to electric fields and solvent use. | [114,115] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Klabukov, I.; Shestakova, V.; Garifullin, A.; Yakimova, A.; Baranovskii, D.; Yatsenko, E.; Ignatyuk, M.; Atiakshin, D.; Shegay, P.; Kaprin, A.D. Critical Systematic Review of 3D Bioprinting in Biomedicine. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 11882. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262411882

Klabukov I, Shestakova V, Garifullin A, Yakimova A, Baranovskii D, Yatsenko E, Ignatyuk M, Atiakshin D, Shegay P, Kaprin AD. Critical Systematic Review of 3D Bioprinting in Biomedicine. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2025; 26(24):11882. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262411882

Chicago/Turabian StyleKlabukov, Ilya, Victoria Shestakova, Airat Garifullin, Anna Yakimova, Denis Baranovskii, Elena Yatsenko, Michael Ignatyuk, Dmitrii Atiakshin, Peter Shegay, and Andrey D. Kaprin. 2025. "Critical Systematic Review of 3D Bioprinting in Biomedicine" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 26, no. 24: 11882. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262411882

APA StyleKlabukov, I., Shestakova, V., Garifullin, A., Yakimova, A., Baranovskii, D., Yatsenko, E., Ignatyuk, M., Atiakshin, D., Shegay, P., & Kaprin, A. D. (2025). Critical Systematic Review of 3D Bioprinting in Biomedicine. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 26(24), 11882. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262411882