Role of Reactive Astrocytes and Microglia: Wnt/β-Catenin Signaling in Neuroprotection and Repair in Parkinson’s Disease

Abstract

1. Introduction

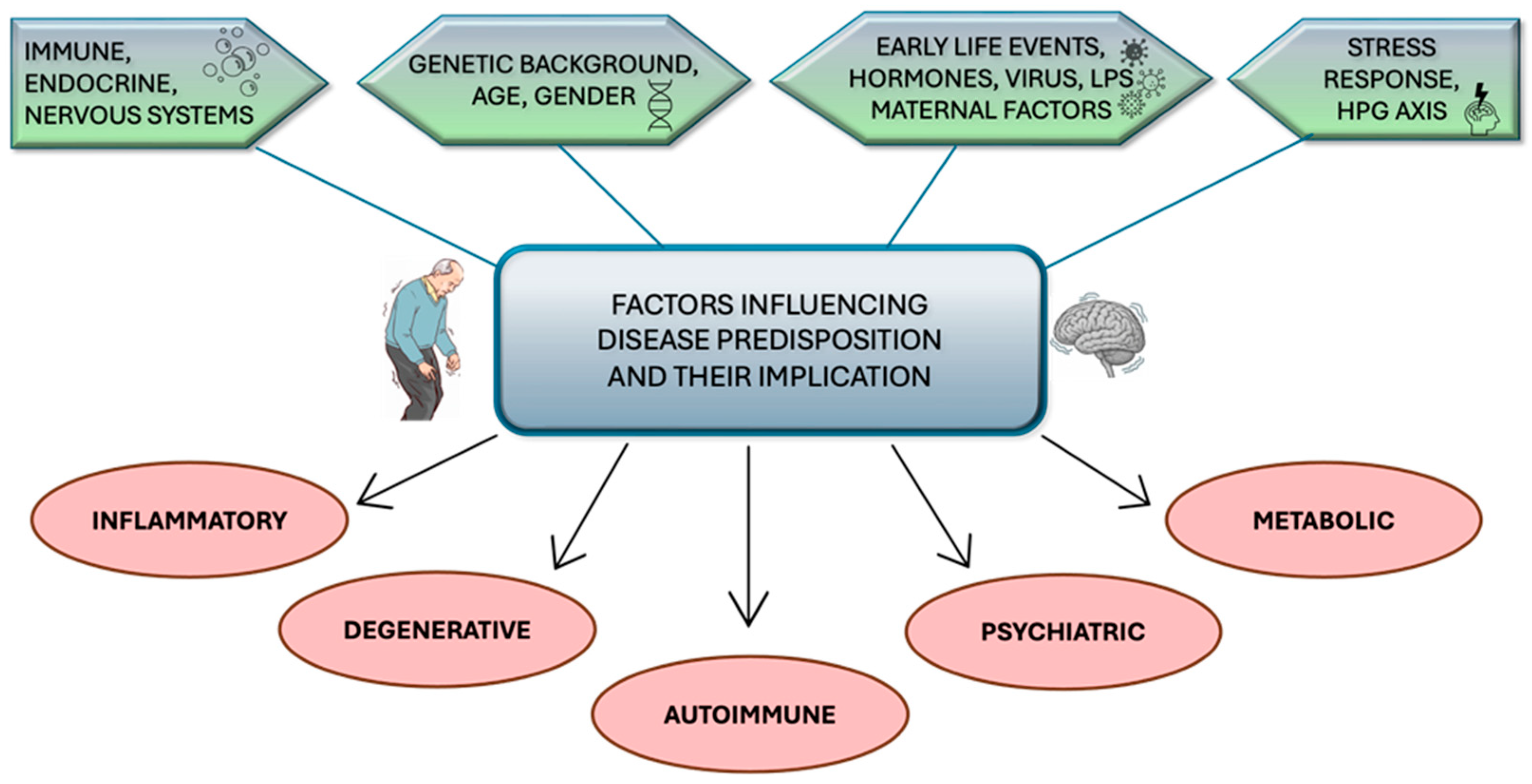

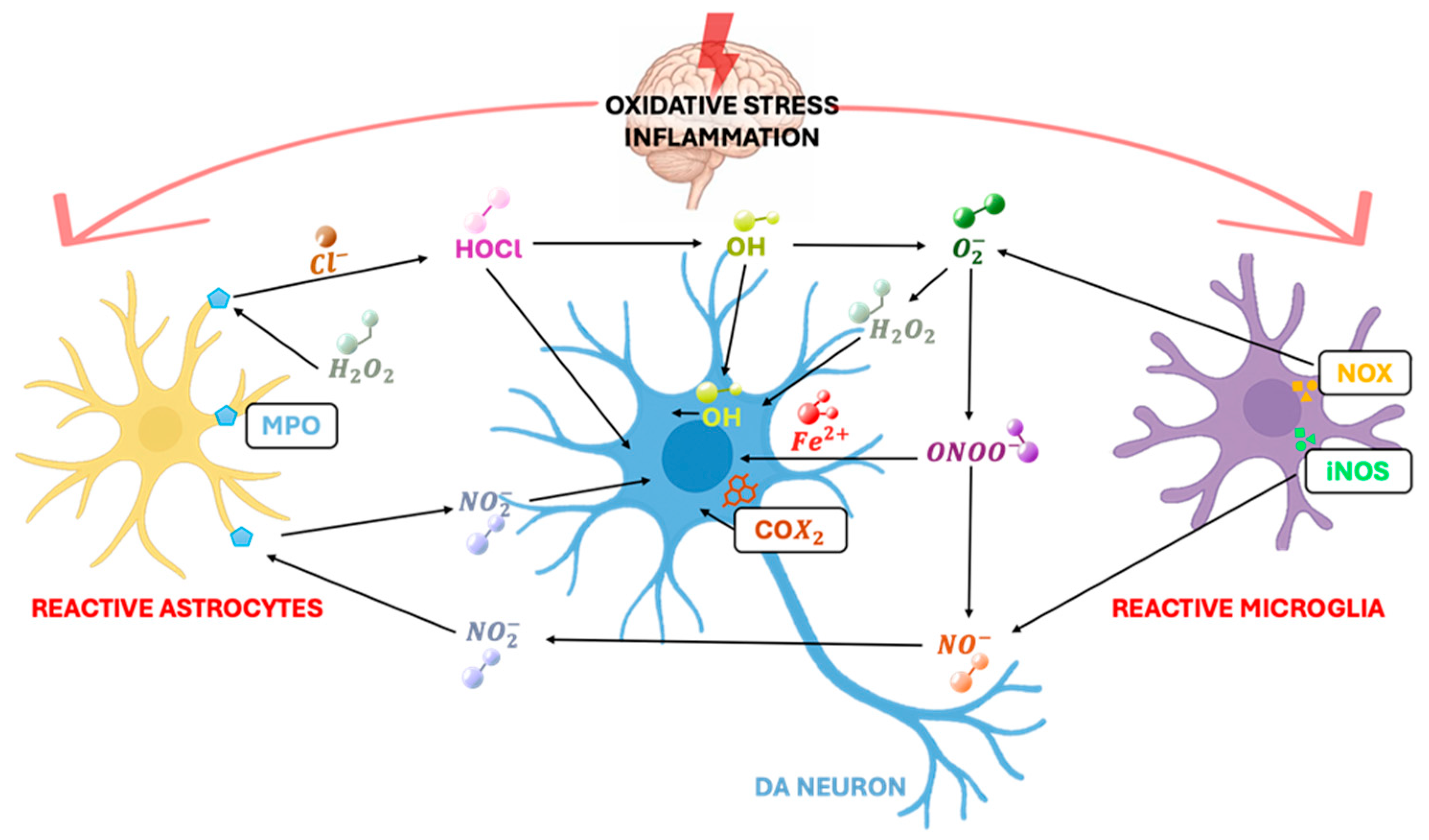

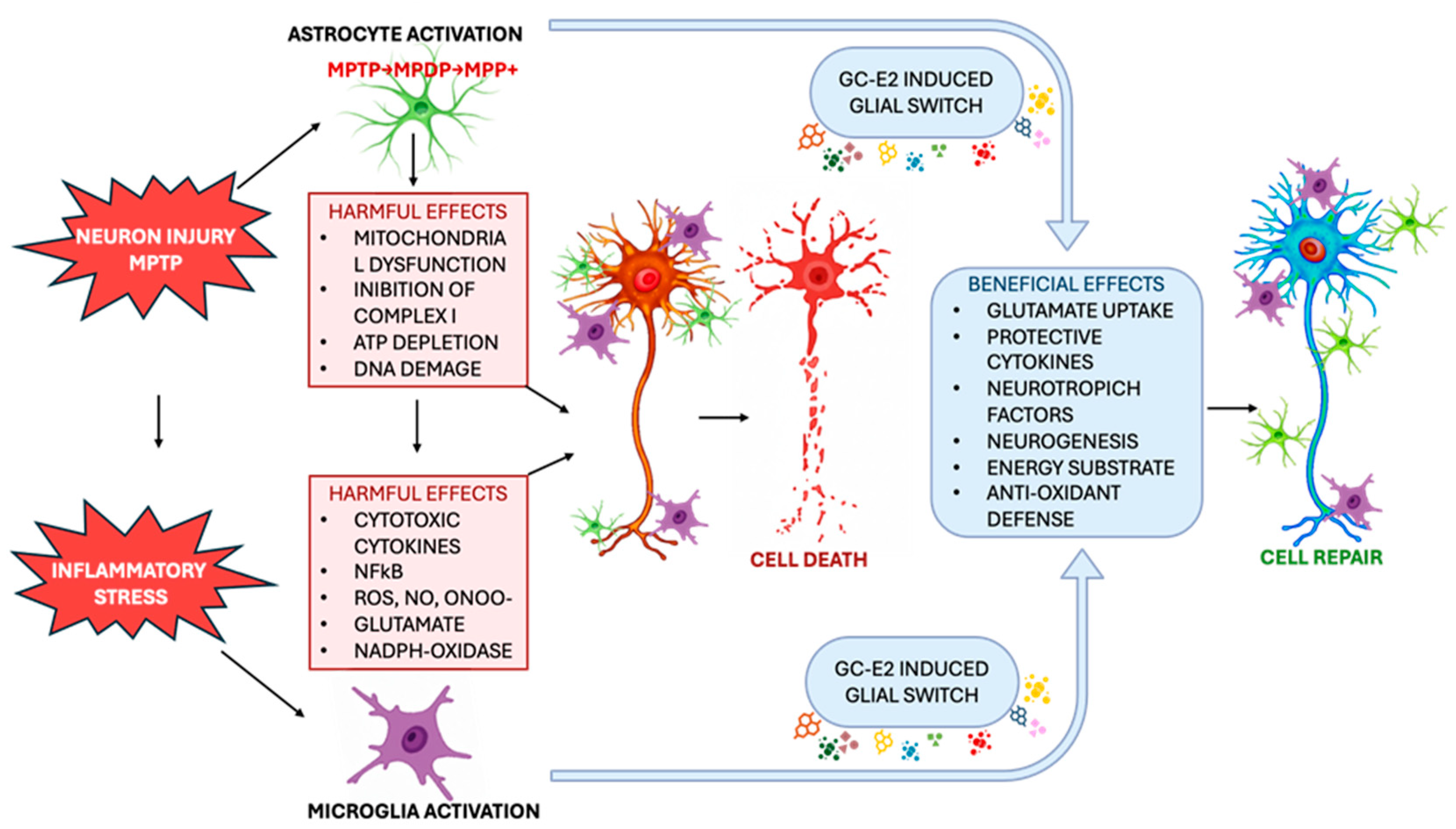

2. Chronic Inflammation as a Determining Factor in the Progression of Parkinsonian Neurodegeneration

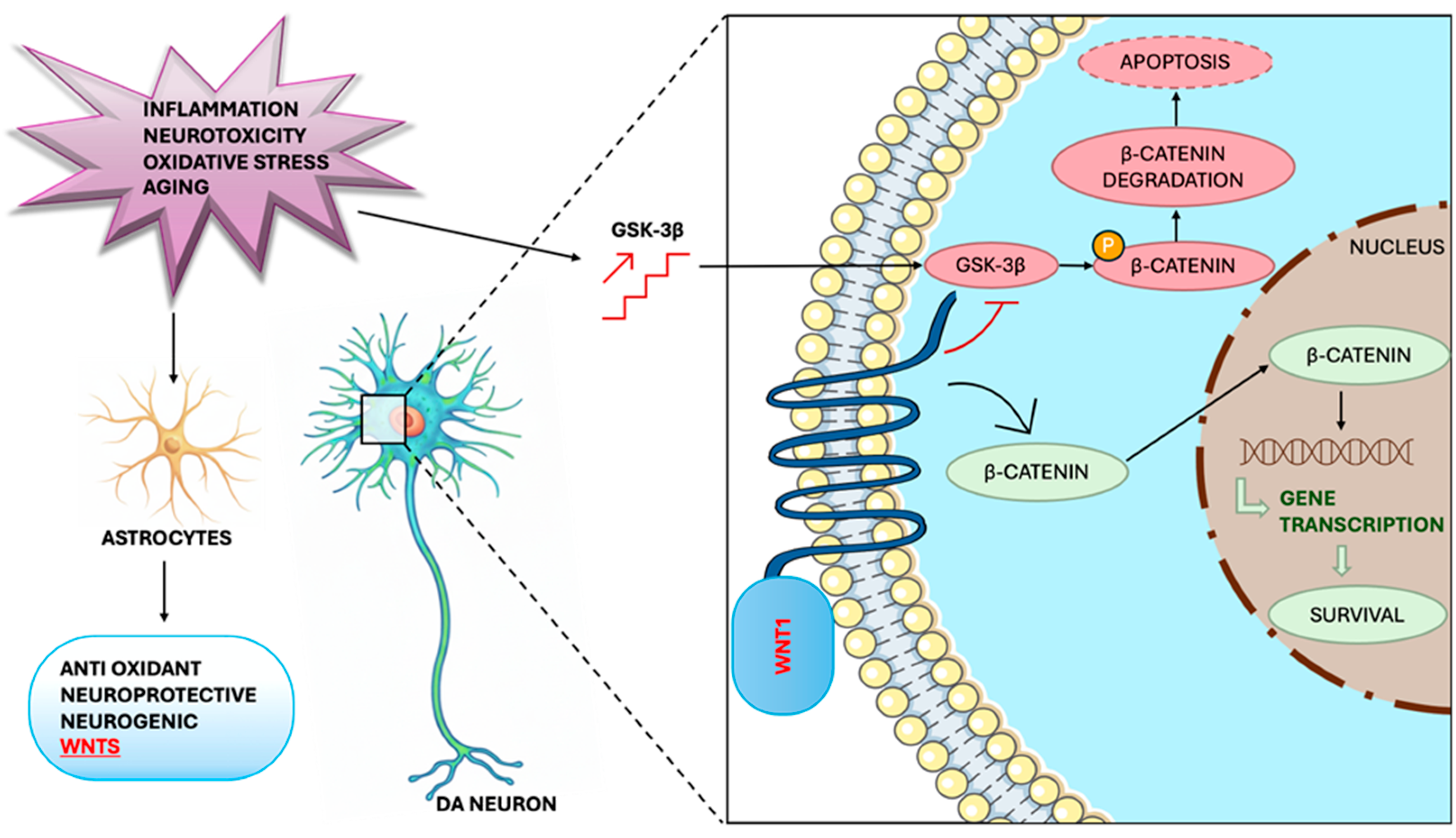

3. Glial Mechanisms in Dopaminergic Neuroprotection: A Target Analysis on Astrocytes

4. The Role of the Glial Pathways in Endogenous Dopaminergic Neuronal Restoration

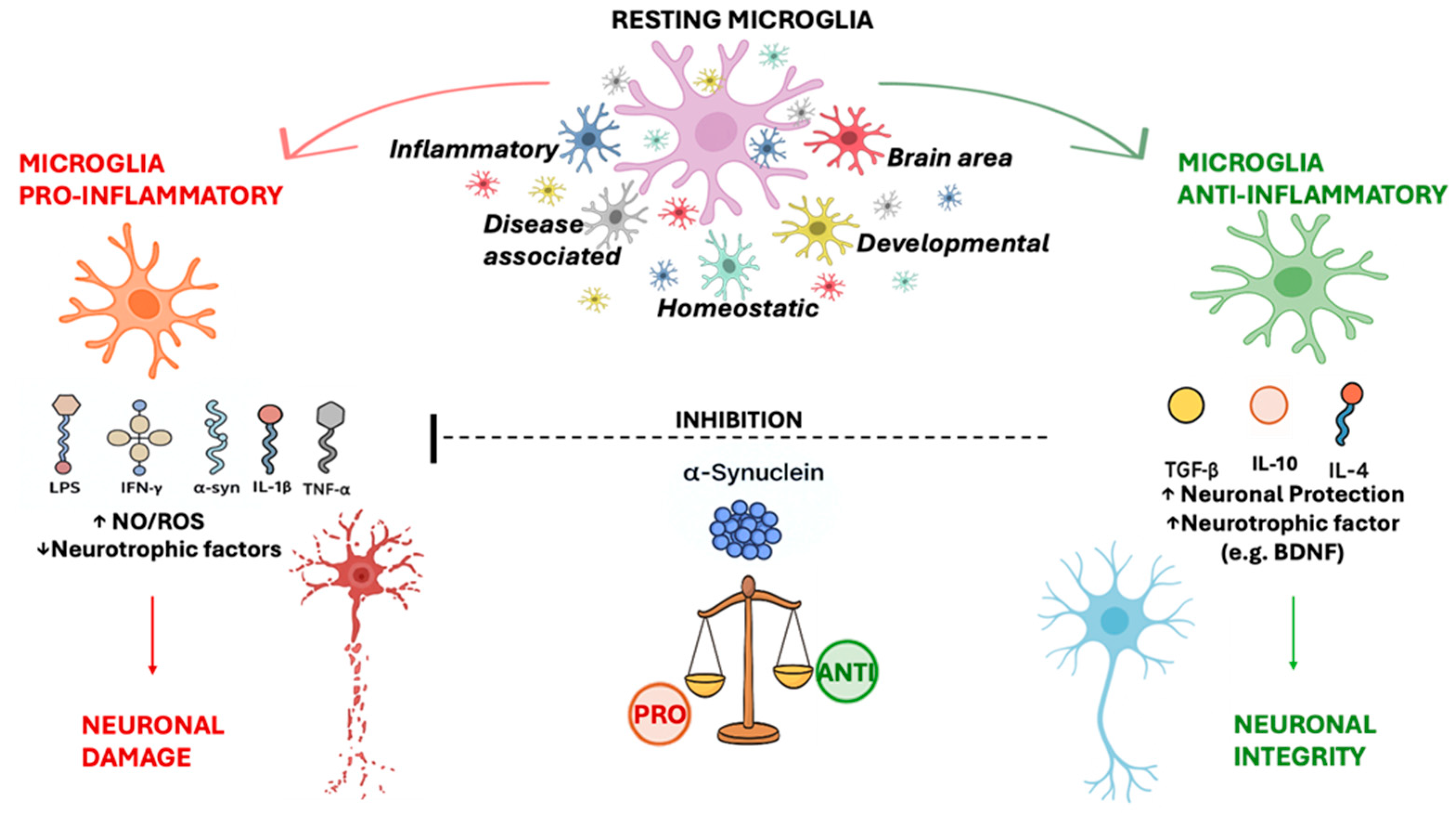

5. The Role of Microglial Cells in Parkinson’s Disease

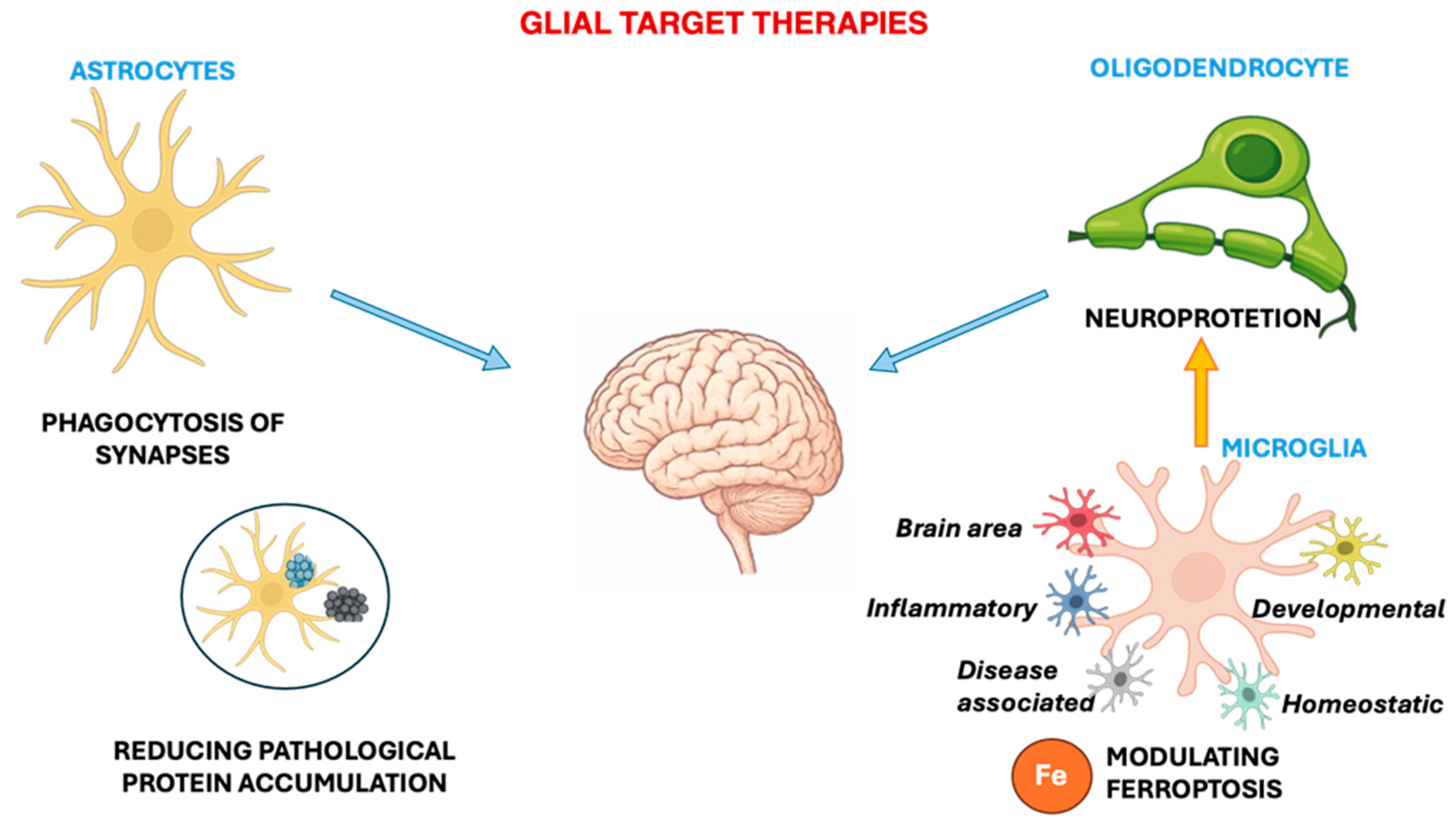

6. Glial-Targeted Therapies: Strengths and Limitations

7. iPSC-Derived Astrocytes as a Model to Study the Role of the Wnt/β-Catenin Pathway in Parkinson’s

8. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| 6-OHDA | 6-Hydroxydopamine |

| ADN | Activity-Dependent Neurotrophic Factor |

| aNPCs | adult Neural Precursor Cells |

| ARE | Antioxidant Response Element |

| BDNF | Brain-Derived Neurotrophic Factor |

| BBB | Blood–Brain Barrier |

| CNS | Central Nervous System |

| COX-2 | Cyclooxygenase-2 |

| CTNF | Ciliary Neurotrophic Factor |

| DA | Dopamine |

| DAergic | Dopaminergic |

| E2 | Estradiol |

| ECM | Extracellular Matrix |

| En-1 | Engrailed-1 (DA-specific transcription factor) |

| ER-α/ER-β | Estrogen Receptor alpha/beta |

| FGF2 | Basic Fibroblast Growth Factor |

| GABA | Gamma–Aminobutyric Acid |

| GCs | Glucocorticoids |

| GDNF | Glial cell line-Derived Neurotrophic Factor |

| GFAP | Glial Fibrillary Acidic Protein |

| GLU | Glutamate |

| GC | Glucocorticoid |

| GR | Glucocorticoid Receptor |

| GSH | Glutathione |

| GSK3β | glycogen synthase kinase 3beta |

| H2O2 | Hydrogen Peroxide |

| HGF | Hepatocyte Growth Factor |

| hiPSCs | human induced Pluripotent Stem Cells |

| IFN-γ | Interferon gamma |

| IL-1β/IL-4/IL-6 | Interleukins (beta, 4, 6) |

| iNOS | inducible Nitric Oxide Synthase |

| iPSCs | induced Pluripotent Stem Cells |

| LPS | Lipopolysaccharide |

| LRP5/6 | low-density lipoprotein receptor-related proteins |

| MAO/MAO-B | Monoamine Oxidase/Monoamine Oxidase B |

| MANF | Mesencephalic Astrocyte-derived Neurotrophic Factor |

| MHC | Major Histocompatibility Complex |

| MMP-9/MMPs | Matrix Metalloproteinase-9/Matrix Metalloproteinases |

| MPP+ | 1-methyl-4-phenylpyridinium |

| MPTP | 1-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine |

| MRP1 | Multidrug Resistance-Associated Protein 1 |

| NADPH | Nicotinamide Adenine Dinucleotide Phosphate |

| NF-κB | Nuclear Factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells |

| NGF | Nerve Growth Factor |

| NO | Nitric Oxide |

| NPCs | Neural Precursor Cells |

| Nrf2 | NF-E2–related factor 2 |

| NSAIDs | Non-Steroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs |

| NSCs | Neural Stem Cells |

| NT-3 | Neurotrophin-3 |

| ONOO- | Peroxynitrite |

| Otx-2 | Orthodenticle Homeobox 2 (DA-specific transcription factor) |

| Pax-2 | Paired Box 2 (DA-specific transcription factor) |

| PD | Parkinson’s disease |

| PGs | Prostaglandins |

| PHOX | NADPH oxidase |

| PGE2 | Prostaglandin E2 |

| RNS | Reactive Nitrogen Species |

| ROS | Reactive Oxygen Species |

| SD | Serum Deprivation |

| SNpc | Substantia Nigra pars compacta |

| SOD | Superoxide Dismutase |

| STAT1 | Signal Transducer and Activator of Transcription 1 |

| SVZ | Subventricular Zone |

| TH+ neurons | Tyrosine Hydroxylase–positive neurons |

| TNF-α | Tumor Necrosis Factor alpha |

| TGF-β1 | Transforming Growth Factor Beta 1 |

| VM | Ventral Midbrain |

| Wnt/Wnt1/Wnt5a | Wingless-type MMTV integration site family |

References

- de Lau, L.M.L.; Breteler, M.M.B. Epidemiology of Parkinson’s Disease. Lancet Neurol. 2006, 5, 525–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez-Rodriguez, P.; Zampese, E.; Surmeier, D.J. Chapter 3—Selective Neuronal Vulnerability in Parkinson’s Disease. In Progress in Brain Research; Björklund, A., Cenci, M.A., Eds.; Recent Advances in Parkinson’s Disease; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2020; Volume 252, pp. 61–89. [Google Scholar]

- He, S.; Ru, Q.; Chen, L.; Xu, G.; Wu, Y. Advances in Animal Models of Parkinson’s Disease. Brain Res. Bull. 2024, 215, 111024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalia, L.V.; Lang, A.E. Parkinson’s Disease. Lancet Lond. Engl. 2015, 386, 896–912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein, C.; Westenberger, A. Genetics of Parkinson’s Disease. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Med. 2012, 2, a008888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nalls, M.A.; Blauwendraat, C.; Vallerga, C.L.; Heilbron, K.; Bandres-Ciga, S.; Chang, D.; Tan, M.; Kia, D.A.; Noyce, A.J.; Xue, A.; et al. Identification of Novel Risk Loci, Causal Insights, and Heritable Risk for Parkinson’s Disease: A Meta-Analysis of Genome-Wide Association Studies. Lancet Neurol. 2019, 18, 1091–1102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gillies, G.E.; Pienaar, I.S.; Vohra, S.; Qamhawi, Z. Sex Differences in Parkinson’s Disease. Front. Neuroendocrinol. 2014, 35, 370–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourque, M.; Soulet, D.; Di Paolo, T. Androgens and Parkinson’s Disease: A Review of Human Studies and Animal Models. Androg. Clin. Res. Ther. 2021, 2, 294–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ascherio, A.; Schwarzschild, M.A. The Epidemiology of Parkinson’s Disease: Risk Factors and Prevention. Lancet Neurol. 2016, 15, 1257–1272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, H.; Li, S. Dose-Response Meta-Analysis on Coffee, Tea and Caffeine Consumption with Risk of Parkinson’s Disease. Geriatr. Gerontol. Int. 2014, 14, 430–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.-F.; Schwarzschild, M.A. Do Caffeine and More Selective Adenosine A2A Receptor Antagonists Protect against Dopaminergic Neurodegeneration in Parkinson’s Disease? Parkinsonism Relat. Disord. 2020, 80 (Suppl. S1), S45–S53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saygili, S.; Hegde, S.; Shi, X.-Z. Effects of Coffee on Gut Microbiota and Bowel Functions in Health and Diseases: A Literature Review. Nutrients 2024, 16, 3155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, S.Y.; Chun, S.; Cho, E.B.; Han, K.; Yoo, J.; Yeo, Y.; Yoo, J.E.; Jeong, S.M.; Min, J.-H.; Shin, D.W. Changes in Smoking, Alcohol Consumption, and the Risk of Parkinson’s Disease. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2023, 15, 1223310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soares, É.N.; Costa, A.C.D.S.; de J. Ferrolho, G.; Ureshino, R.P.; Getachew, B.; Costa, S.L.; da Silva, V.D.A.; Tizabi, Y. Nicotinic Acetylcholine Receptors in Glial Cells as Molecular Target for Parkinson’s Disease. Cells 2024, 13, 474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soares, A.R.; Picciotto, M.R. Nicotinic Regulation of Microglia: Potential Contributions to Addiction. J. Neural Transm. 2024, 131, 425–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herraiz, T.; Chaparro, C. Human Monoamine Oxidase Is Inhibited by Tobacco Smoke: Beta-Carboline Alkaloids Act as Potent and Reversible Inhibitors. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2005, 326, 378–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, X.; Chen, H.; Schwarzschild, M.A.; Ascherio, A. Use of Ibuprofen and Risk of Parkinson Disease. Neurology 2011, 76, 863–869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mustapha, M.; Mat Taib, C.N. MPTP-Induced Mouse Model of Parkinson’s Disease: A Promising Direction of Therapeutic Strategies. Bosn. J. Basic Med. Sci. 2021, 21, 422–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lind-Holm Mogensen, F.; Seibler, P.; Grünewald, A.; Michelucci, A. Microglial Dynamics and Neuroinflammation in Prodromal and Early Parkinson’s Disease. J. Neuroinflammation 2025, 22, 136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirsch, E.C.; Vyas, S.; Hunot, S. Neuroinflammation in Parkinson’s Disease. Parkinsonism Relat. Disord. 2012, 18 (Suppl. S1), S210–S212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miller, D.W.; Cookson, M.R.; Dickson, D.W. Glial Cell Inclusions and the Pathogenesis of Neurodegenerative Diseases. Neuron Glia Biol. 2004, 1, 13–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tansey, M.G.; Romero-Ramos, M. Immune System Responses in Parkinson’s Disease: Early and Dynamic. Eur. J. Neurosci. 2019, 49, 364–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subramaniam, S.R.; Federoff, H.J. Targeting Microglial Activation States as a Therapeutic Avenue in Parkinson’s Disease. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2017, 9, 176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kempuraj, D.; Ahmed, M.E.; Selvakumar, G.P.; Thangavel, R.; Dhaliwal, A.S.; Dubova, I.; Mentor, S.; Premkumar, K.; Saeed, D.; Zahoor, H.; et al. Brain Injury-Mediated Neuroinflammatory Response and Alzheimer’s Disease. Neurosci. Rev. J. Bringing Neurobiol. Neurol. Psychiatry 2020, 26, 134–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sierra, A.; Beccari, S.; Diaz-Aparicio, I.; Encinas, J.M.; Comeau, S.; Tremblay, M.-È. Surveillance, Phagocytosis, and Inflammation: How Never-Resting Microglia Influence Adult Hippocampal Neurogenesis. Neural Plast. 2014, 2014, 610343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- L’Episcopo, F.; Tirolo, C.; Testa, N.; Caniglia, S.; Morale, M.C.; Marchetti, B. Reactive Astrocytes Are Key Players in Nigrostriatal Dopaminergic Neurorepair in the Mptp Mouse Model of Parkinson’s Disease: Focus on Endogenous Neurorestoration. Curr. Aging Sci. 2013, 6, 45–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hampel, H.; Caraci, F.; Cuello, A.C.; Caruso, G.; Nisticò, R.; Corbo, M.; Baldacci, F.; Toschi, N.; Garaci, F.; Chiesa, P.A.; et al. A Path Toward Precision Medicine for Neuroinflammatory Mechanisms in Alzheimer’s Disease. Front. Immunol. 2020, 11, 456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tansey, M.G.; Goldberg, M.S. Neuroinflammation in Parkinson’s Disease: Its Role in Neuronal Death and Implications for Therapeutic Intervention. Neurobiol. Dis. 2010, 37, 510–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pekny, M.; Pekna, M. Astrocyte Reactivity and Reactive Astrogliosis: Costs and Benefits. Physiol. Rev. 2014, 94, 1077–1098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liddelow, S.A.; Barres, B.A. Reactive Astrocytes: Production, Function, and Therapeutic Potential. Immunity 2017, 46, 957–967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, W.-L.; Gong, X.-X.; Qin, Z.-H.; Wang, Y. Molecular Mechanisms of Excitotoxicity and Their Relevance to the Pathogenesis of Neurodegenerative Diseases-an Update. Acta Pharmacol. Sin. 2025, 46, 3129–3142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valiukas, Z.; Tangalakis, K.; Apostolopoulos, V.; Feehan, J. Microglial Activation States and Their Implications for Alzheimer’s Disease. J. Prev. Alzheimers Dis. 2025, 12, 100013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, H.S.; Koh, S.-H. Neuroinflammation in Neurodegenerative Disorders: The Roles of Microglia and Astrocytes. Transl. Neurodegener. 2020, 9, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, K.; Li, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Shi, Y.; Zhang, C.; Bai, Y.; Wang, S. Neuroinflammation in Parkinson’s Disease: Focus on the Relationship between miRNAs and Microglia. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 2024, 18, 1429977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isik, S.; Yeman Kiyak, B.; Akbayir, R.; Seyhali, R.; Arpaci, T. Microglia Mediated Neuroinflammation in Parkinson’s Disease. Cells 2023, 12, 1012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çınar, E.; Tel, B.C.; Şahin, G. Neuroinflammation in Parkinson’s Disease and Its Treatment Opportunities. Balk. Med. J. 2022, 39, 318–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- L’Episcopo, F.; Tirolo, C.; Caniglia, S.; Testa, N.; Serra, P.A.; Impagnatiello, F.; Morale, M.C.; Marchetti, B. Combining Nitric Oxide Release with Anti-Inflammatory Activity Preserves Nigrostriatal Dopaminergic Innervation and Prevents Motor Impairment in a 1-Methyl-4-Phenyl-1,2,3,6-Tetrahydropyridine Model of Parkinson’s Disease. J. Neuroinflammation 2010, 7, 83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kouli, A.; Camacho, M.; Allinson, K.; Williams-Gray, C.H. Neuroinflammation and Protein Pathology in Parkinson’s Disease Dementia. Acta Neuropathol. Commun. 2020, 8, 211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halliday, G.M.; Stevens, C.H. Glia: Initiators and Progressors of Pathology in Parkinson’s Disease. Mov. Disord. Off. J. Mov. Disord. Soc. 2011, 26, 6–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kano, M.; Takanashi, M.; Oyama, G.; Yoritaka, A.; Hatano, T.; Shiba-Fukushima, K.; Nagai, M.; Nishiyama, K.; Hasegawa, K.; Inoshita, T.; et al. Reduced Astrocytic Reactivity in Human Brains and Midbrain Organoids with PRKN Mutations. NPJ Park. Dis. 2020, 6, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sofroniew, M.V.; Vinters, H.V. Astrocytes: Biology and Pathology. Acta Neuropathol. 2010, 119, 7–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segura-Aguilar, J.; Mannervik, B.; Inzunza, J.; Varshney, M.; Nalvarte, I.; Muñoz, P. Astrocytes Protect Dopaminergic Neurons against Aminochrome Neurotoxicity. Neural Regen. Res. 2022, 17, 1861–1866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Liu, Y.; Sun, Y.; Guo, H.; Lv, S.; Guo, W.; Ren, J.; Wang, Y.; Zu, J.; Yan, J.; et al. Targeting Astrocytes Polarization after Spinal Cord Injury: A Promising Direction. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 2024, 18, 1478741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verkhratsky, A.; Nedergaard, M. Physiology of Astroglia. Physiol. Rev. 2018, 98, 239–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khakh, B.S.; Sofroniew, M.V. Diversity of Astrocyte Functions and Phenotypes in Neural Circuits. Nat. Neurosci. 2015, 18, 942–952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Hua, Z.; Li, Z. The Role of Glutamate and Glutamine Metabolism and Related Transporters in Nerve Cells. CNS Neurosci. Ther. 2024, 30, e14617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersen, J.V. The Glutamate/GABA-Glutamine Cycle: Insights, Updates, and Advances. J. Neurochem. 2025, 169, e70029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giaume, C.; Leybaert, L.; Naus, C.C.; Sáez, J.C. Connexin and Pannexin Hemichannels in Brain Glial Cells: Properties, Pharmacology, and Roles. Front. Pharmacol. 2013, 4, 88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanz-Gálvez, R.; Falardeau, D.; Kolta, A.; Inglebert, Y. The Role of Astrocytes from Synaptic to Non-Synaptic Plasticity. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 2024, 18, 1477985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perea, G.; Navarrete, M.; Araque, A. Tripartite Synapses: Astrocytes Process and Control Synaptic Information. Trends Neurosci. 2009, 32, 421–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levi, S.; Ripamonti, M.; Moro, A.S.; Cozzi, A. Iron Imbalance in Neurodegeneration. Mol. Psychiatry 2024, 29, 1139–1152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magistretti, P.J.; Allaman, I. A Cellular Perspective on Brain Energy Metabolism and Functional Imaging. Neuron 2015, 86, 883–901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bélanger, M.; Allaman, I.; Magistretti, P.J. Brain Energy Metabolism: Focus on Astrocyte-Neuron Metabolic Cooperation. Cell Metab. 2011, 14, 724–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aoyama, K. Glutathione in the Brain. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 5010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jurcau, M.-C.; Jurcau, A.; Diaconu, R.-G. Oxidative Stress in the Pathogenesis of Neurodegenerative Diseases. Stresses 2024, 4, 827–849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, M.; Xu, K.; Ge, J.; Luo, X.; Wu, M.; Wang, N.; Zeng, J. Targeting Ferroptosis in Parkinson’s Disease: Mechanisms and Emerging Therapeutic Strategies. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 13042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, B.; Wang, G.; He, J.; Yang, Q.; Li, D.; Li, J.; Zhang, F. Icariin Attenuates Neuroinflammation and Exerts Dopamine Neuroprotection via an Nrf2-Dependent Manner. J. Neuroinflammation 2019, 16, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soni, P.; Sharma, S.M.; Pieper, A.A.; Paul, B.D.; Thomas, B. Nrf2/Bach1 Signaling Axis: A Promising Multifaceted Therapeutic Strategy for Alzheimer’s Disease. Neurother. J. Am. Soc. Exp. Neurother. 2025, 22, e00586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshi, G.; Johnson, J.A. The Nrf2-ARE Pathway: A Valuable Therapeutic Target for the Treatment of Neurodegenerative Diseases. Recent Patents CNS Drug Discov. 2012, 7, 218–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takahashi, S.; Mashima, K. Neuroprotection and Disease Modification by Astrocytes and Microglia in Parkinson Disease. Antioxidants 2022, 11, 170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Ovejero, D.; Veiga, S.; García-Segura, L.M.; Doncarlos, L.L. Glial Expression of Estrogen and Androgen Receptors after Rat Brain Injury. J. Comp. Neurol. 2002, 450, 256–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, J.; Ma, N.; Zhong, J.; Yu, B.; Wan, J.; Zhang, W. Age-Associated Changes in Microglia and Astrocytes Ameliorate Blood-Brain Barrier Dysfunction. Mol. Ther. Nucleic Acids 2021, 26, 970–986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Nicola, A.F.; Labombarda, F.; Gonzalez, S.L.; Gonzalez Deniselle, M.C.; Guennoun, R.; Schumacher, M. Steroid Effects on Glial Cells: Detrimental or Protective for Spinal Cord Function? Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2003, 1007, 317–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ros-Bernal, F.; Hunot, S.; Herrero, M.T.; Parnadeau, S.; Corvol, J.-C.; Lu, L.; Alvarez-Fischer, D.; Carrillo-de Sauvage, M.A.; Saurini, F.; Coussieu, C.; et al. Microglial Glucocorticoid Receptors Play a Pivotal Role in Regulating Dopaminergic Neurodegeneration in Parkinsonism. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2011, 108, 6632–6637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dluzen, D.E. Neuroprotective Effects of Estrogen upon the Nigrostriatal Dopaminergic System. J. Neurocytol. 2000, 29, 387–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sánchez, M.G.; Morissette, M.; Di Paolo, T. Effect of a Chronic Treatment with 17β-Estradiol on Striatal Dopamine Neurotransmission and the Akt/GSK3 Signaling Pathway in the Brain of Ovariectomized Monkeys. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2012, 37, 280–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sonninen, T.-M.; Hämäläinen, R.H.; Koskuvi, M.; Oksanen, M.; Shakirzyanova, A.; Wojciechowski, S.; Puttonen, K.; Naumenko, N.; Goldsteins, G.; Laham-Karam, N.; et al. Metabolic Alterations in Parkinson’s Disease Astrocytes. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 14474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saldanha, C.J.; Duncan, K.A.; Walters, B.J. Neuroprotective Actions of Brain Aromatase. Front. Neuroendocrinol. 2009, 30, 106–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, S.-Y.; Chen, Y.-W.; Tsai, S.-F.; Wu, S.-N.; Shih, Y.-H.; Jiang-Shieh, Y.-F.; Yang, T.-T.; Kuo, Y.-M. Estrogen Ameliorates Microglial Activation by Inhibiting the Kir2.1 Inward-Rectifier K+ Channel. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 22864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barreto, G.E.; Santos-Galindo, M.; Garcia-Segura, L.M. Selective Estrogen Receptor Modulators Regulate Reactive Microglia after Penetrating Brain Injury. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2014, 6, 132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acosta-Martínez, M. Shaping Microglial Phenotypes Through Estrogen Receptors: Relevance to Sex-Specific Neuroinflammatory Responses to Brain Injury and Disease. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2020, 375, 223–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Tan, X.; Tang, C. Estrogen-Immuno-Neuromodulation Disorders in Menopausal Depression. J. Neuroinflammation 2024, 21, 159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spence, R.D.; Voskuhl, R.R. Neuroprotective Effects of Estrogens and Androgens in CNS Inflammation and Neurodegeneration. Front. Neuroendocrinol. 2012, 33, 105–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timoshina, Y.A.; Pavlova, A.K.; Voronkov, D.N.; Abaimov, D.A.; Latanov, A.V.; Fedorova, T.N. Assessment of the Behavioral and Neurochemical Characteristics in a Mice Model of the Premotor Stage of Parkinson’s Disease Induced by Chronic Administration of a Low Dose of MPTP. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 8856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blesa, J.; Trigo-Damas, I.; Dileone, M.; Del Rey, N.L.-G.; Hernandez, L.F.; Obeso, J.A. Compensatory Mechanisms in Parkinson’s Disease: Circuits Adaptations and Role in Disease Modification. Exp. Neurol. 2017, 298, 148–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krieglstein, K.; Henheik, P.; Farkas, L.; Jaszai, J.; Galter, D.; Krohn, K.; Unsicker, K. Glial Cell Line-Derived Neurotrophic Factor Requires Transforming Growth Factor-Beta for Exerting Its Full Neurotrophic Potential on Peripheral and CNS Neurons. J. Neurosci. Off. J. Soc. Neurosci. 1998, 18, 9822–9834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Airaksinen, M.S.; Saarma, M. The GDNF Family: Signalling, Biological Functions and Therapeutic Value. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2002, 3, 383–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindholm, D.; Mäkelä, J.; Di Liberto, V.; Mudò, G.; Belluardo, N.; Eriksson, O.; Saarma, M. Current Disease Modifying Approaches to Treat Parkinson’s Disease. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2016, 73, 1365–1379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovaleva, V.; Yu, L.-Y.; Ivanova, L.; Shpironok, O.; Nam, J.; Eesmaa, A.; Kumpula, E.-P.; Sakson, S.; Toots, U.; Ustav, M.; et al. MANF Regulates Neuronal Survival and UPR through Its ER-Located Receptor IRE1α. Cell Rep. 2023, 42, 112066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, F.; Liu, Y.; Tu, J.; Wan, J.; Zhang, J.; Wu, B.; Chen, S.; Zhou, J.; Mu, Y.; Wang, L. Activated Astrocytes Enhance the Dopaminergic Differentiation of Stem Cells and Promote Brain Repair through bFGF. Nat. Commun. 2014, 5, 5627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robel, S.; Berninger, B.; Götz, M. The Stem Cell Potential of Glia: Lessons from Reactive Gliosis. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2011, 12, 88–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Z.; Duan, J.; Cao, A.; Gong, Z.; Liu, H.; Shen, D.; Ye, T.; Zhu, S.; Cen, Q.; He, S.; et al. Activating Wnt1/β-Catenin Signaling Pathway to Restore Otx2 Expression in the Dopaminergic Neurons of Ventral Midbrain. Exp. Neurol. 2025, 388, 115216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parish, C.L.; Castelo-Branco, G.; Rawal, N.; Tonnesen, J.; Sorensen, A.T.; Salto, C.; Kokaia, M.; Lindvall, O.; Arenas, E. Wnt5a-Treated Midbrain Neural Stem Cells Improve Dopamine Cell Replacement Therapy in Parkinsonian Mice. J. Clin. Invest. 2008, 118, 149–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caruso, A.; Motolese, M.; Iacovelli, L.; Caraci, F.; Copani, A.; Nicoletti, F.; Terstappen, G.C.; Gaviraghi, G.; Caricasole, A. Inhibition of the Canonical Wnt Signaling Pathway by Apolipoprotein E4 in PC12 Cells. J. Neurochem. 2006, 98, 364–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rim, E.Y.; Clevers, H.; Nusse, R. The Wnt Pathway: From Signaling Mechanisms to Synthetic Modulators. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2022, 91, 571–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prunier, C.; Hocevar, B.A.; Howe, P.H. Wnt Signaling: Physiology and Pathology. Growth Factors 2004, 22, 141–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inestrosa, N.C.; Arenas, E. Emerging Roles of Wnts in the Adult Nervous System. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2010, 11, 77–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oliva, C.A.; Vargas, J.Y.; Inestrosa, N.C. Wnts in Adult Brain: From Synaptic Plasticity to Cognitive Deficiencies. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 2013, 7, 224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, J.; Xiao, Q.; Xiao, J.; Niu, C.; Li, Y.; Zhang, X.; Zhou, Z.; Shu, G.; Yin, G. Wnt/β-Catenin Signalling: Function, Biological Mechanisms, and Therapeutic Opportunities. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2022, 7, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- L’episcopo, F.; Serapide, M.F.; Tirolo, C.; Testa, N.; Caniglia, S.; Morale, M.C.; Pluchino, S.; Marchetti, B. A Wnt1 Regulated Frizzled-1/β-Catenin Signaling Pathway as a Candidate Regulatory Circuit Controlling Mesencephalic Dopaminergic Neuron-Astrocyte Crosstalk: Therapeutical Relevance for Neuron Survival and Neuroprotection. Mol. Neurodegener. 2011, 6, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- L’Episcopo, F.; Tirolo, C.; Testa, N.; Caniglia, S.; Morale, M.C.; Cossetti, C.; D’Adamo, P.; Zardini, E.; Andreoni, L.; Ihekwaba, A.E.C.; et al. Reactive Astrocytes and Wnt/β-Catenin Signaling Link Nigrostriatal Injury to Repair in 1-Methyl-4-Phenyl-1,2,3,6-Tetrahydropyridine Model of Parkinson’s Disease. Neurobiol. Dis. 2011, 41, 508–527, Erratum in: Neurobiol. Dis. 2011, 42, 539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- L’Episcopo, F.; Tirolo, C.; Serapide, M.F.; Caniglia, S.; Testa, N.; Leggio, L.; Vivarelli, S.; Iraci, N.; Pluchino, S.; Marchetti, B. Microglia Polarization, Gene-Environment Interactions and Wnt/β-Catenin Signaling: Emerging Roles of Glia-Neuron and Glia-Stem/Neuroprogenitor Crosstalk for Dopaminergic Neurorestoration in Aged Parkinsonian Brain. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2018, 10, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- L’Episcopo, F.; Tirolo, C.; Testa, N.; Caniglia, S.; Morale, M.C.; Serapide, M.F.; Pluchino, S.; Marchetti, B. Wnt/β-Catenin Signaling Is Required to Rescue Midbrain Dopaminergic Progenitors and Promote Neurorepair in Ageing Mouse Model of Parkinson’s Disease. Stem Cells Dayt. Ohio 2014, 32, 2147–2163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marchetti, B. Wnt/β-Catenin Signaling Pathway Governs a Full Program for Dopaminergic Neuron Survival, Neurorescue and Regeneration in the MPTP Mouse Model of Parkinson’s Disease. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 3743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grondin, R.; Zhang, Z.; Yi, A.; Cass, W.A.; Maswood, N.; Andersen, A.H.; Elsberry, D.D.; Klein, M.C.; Gerhardt, G.A.; Gash, D.M. Chronic, Controlled GDNF Infusion Promotes Structural and Functional Recovery in Advanced Parkinsonian Monkeys. Brain J. Neurol. 2002, 125, 2191–2201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arenas, E. Wnt Signaling in Midbrain Dopaminergic Neuron Development and Regenerative Medicine for Parkinson’s Disease. J. Mol. Cell Biol. 2014, 6, 42–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szewczyk, L.M.; Lipiec, M.A.; Liszewska, E.; Meyza, K.; Urban-Ciecko, J.; Kondrakiewicz, L.; Goncerzewicz, A.; Rafalko, K.; Krawczyk, T.G.; Bogaj, K.; et al. Astrocytic β-Catenin Signaling via TCF7L2 Regulates Synapse Development and Social Behavior. Mol. Psychiatry 2024, 29, 57–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faust, T.E.; Lee, Y.-H.; O’Connor, C.D.; Boyle, M.A.; Gunner, G.; Durán-Laforet, V.; Ferrari, L.L.; Murphy, R.E.; Badimon, A.; Sakers, K.; et al. Microglia-Astrocyte Crosstalk Regulates Synapse Remodeling via Wnt Signaling. Cell 2025, 188, 5212–5230.e21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ming, G.-L.; Song, H. Adult Neurogenesis in the Mammalian Brain: Significant Answers and Significant Questions. Neuron 2011, 70, 687–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gage, F.H. Adult Neurogenesis in Mammals. Science 2019, 364, 827–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baig, S.; Nadaf, J.; Allache, R.; Le, P.U.; Luo, M.; Djedid, A.; Nkili-Meyong, A.; Safisamghabadi, M.; Prat, A.; Antel, J.; et al. Identity and Nature of Neural Stem Cells in the Adult Human Subventricular Zone. iScience 2024, 27, 109342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shan, X.; Chi, L.; Bishop, M.; Luo, C.; Lien, L.; Zhang, Z.; Liu, R. Enhanced de Novo Neurogenesis and Dopaminergic Neurogenesis in the Substantia Nigra of 1-Methyl-4-Phenyl-1,2,3,6-Tetrahydropyridine-Induced Parkinson’s Disease-like Mice. Stem Cells Dayt. Ohio 2006, 24, 1280–1287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mourtzi, T.; Dimitrakopoulos, D.; Kakogiannis, D.; Salodimitris, C.; Botsakis, K.; Meri, D.K.; Anesti, M.; Dimopoulou, A.; Charalampopoulos, I.; Gravanis, A.; et al. Characterization of Substantia Nigra Neurogenesis in Homeostasis and Dopaminergic Degeneration: Beneficial Effects of the Microneurotrophin BNN-20. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2021, 12, 335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hermann, A.; Maisel, M.; Wegner, F.; Liebau, S.; Kim, D.-W.; Gerlach, M.; Schwarz, J.; Kim, K.-S.; Storch, A. Multipotent Neural Stem Cells from the Adult Tegmentum with Dopaminergic Potential Develop Essential Properties of Functional Neurons. Stem Cells Dayt. Ohio 2006, 24, 949–964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kohman, R.A.; Rhodes, J.S. Neurogenesis, Inflammation and Behavior. Brain. Behav. Immun. 2013, 27, 22–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smirnova, M.I.; Quan, N. Modulation of Adult Hippocampal Neurogenesis by Interleukin 1 Signaling. Neurobiol. Sleep Circadian Rhythms 2025, 18, 100123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyle, C.C.; Bower, J.E.; Eisenberger, N.I.; Irwin, M.R. Stress to Inflammation and Anhedonia: Mechanistic Insights from Preclinical and Clinical Models. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2023, 152, 105307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valero, J.; Mastrella, G.; Neiva, I.; Sánchez, S.; Malva, J.O. Long-Term Effects of an Acute and Systemic Administration of LPS on Adult Neurogenesis and Spatial Memory. Front. Neurosci. 2014, 8, 83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shohayeb, B.; Diab, M.; Ahmed, M.; Ng, D.C.H. Factors That Influence Adult Neurogenesis as Potential Therapy. Transl. Neurodegener. 2018, 7, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blum-Degen, D.; Müller, T.; Kuhn, W.; Gerlach, M.; Przuntek, H.; Riederer, P. Interleukin-1 Beta and Interleukin-6 Are Elevated in the Cerebrospinal Fluid of Alzheimer’s and de Novo Parkinson’s Disease Patients. Neurosci. Lett. 1995, 202, 17–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pons-Espinal, M.; Blasco-Agell, L.; Fernandez-Carasa, I.; Andrés-Benito, P.; di Domenico, A.; Richaud-Patin, Y.; Baruffi, V.; Marruecos, L.; Espinosa, L.; Garrido, A.; et al. Blocking IL-6 Signaling Prevents Astrocyte-Induced Neurodegeneration in an iPSC-Based Model of Parkinson’s Disease. JCI Insight 2024, 9, e163359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asl, S.S.; Jalili, C.; Artimani, T.; Ramezani, M.; Mirzaei, F. Inflammasome Can Affect Adult Neurogenesis: A Review Article. Open Neurol. J. 2021, 15, 25–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butovsky, O.; Ziv, Y.; Schwartz, A.; Landa, G.; Talpalar, A.E.; Pluchino, S.; Martino, G.; Schwartz, M. Microglia Activated by IL-4 or IFN-Gamma Differentially Induce Neurogenesis and Oligodendrogenesis from Adult Stem/Progenitor Cells. Mol. Cell. Neurosci. 2006, 31, 149–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Früholz, I.; Meyer-Luehmann, M. The Intricate Interplay between Microglia and Adult Neurogenesis in Alzheimer’s Disease. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 2024, 18, 1456253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cacci, E.; Ajmone-Cat, M.A.; Anelli, T.; Biagioni, S.; Minghetti, L. In Vitro Neuronal and Glial Differentiation from Embryonic or Adult Neural Precursor Cells Are Differently Affected by Chronic or Acute Activation of Microglia. Glia 2008, 56, 412–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosseini, S.M.; Nemati, S.; Karimi-Abdolrezaee, S. Astrocytes Originated from Neural Stem Cells Drive the Regenerative Remodeling of Pathologic CSPGs in Spinal Cord Injury. Stem Cell Rep. 2024, 19, 1451–1473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fauser, M.; Loewenbrück, K.F.; Rangnick, J.; Brandt, M.D.; Hermann, A.; Storch, A. Adult Neural Stem Cells from Midbrain Periventricular Regions Show Limited Neurogenic Potential after Transplantation into the Hippocampal Neurogenic Niche. Cells 2021, 10, 3021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arredondo, S.B.; Valenzuela-Bezanilla, D.; Mardones, M.D.; Varela-Nallar, L. Role of Wnt Signaling in Adult Hippocampal Neurogenesis in Health and Disease. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2020, 8, 860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heneka, M.T.; Carson, M.J.; El Khoury, J.; Landreth, G.E.; Brosseron, F.; Feinstein, D.L.; Jacobs, A.H.; Wyss-Coray, T.; Vitorica, J.; Ransohoff, R.M.; et al. Neuroinflammation in Alzheimer’s Disease. Lancet Neurol. 2015, 14, 388–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J.; Torres, C. Astrocyte Senescence: Evidence and Significance. Aging Cell 2019, 18, e12937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harry, G.J. Microglia during Development and Aging. Pharmacol. Ther. 2013, 139, 313–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stevens, B.; Allen, N.J.; Vazquez, L.E.; Howell, G.R.; Christopherson, K.S.; Nouri, N.; Micheva, K.D.; Mehalow, A.K.; Huberman, A.D.; Stafford, B.; et al. The Classical Complement Cascade Mediates CNS Synapse Elimination. Cell 2007, 131, 1164–1178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henstridge, C.M.; Tzioras, M.; Paolicelli, R.C. Glial Contribution to Excitatory and Inhibitory Synapse Loss in Neurodegeneration. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 2019, 13, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarlus, H.; Heneka, M.T. Microglia in Alzheimer’s Disease. J. Clin. Invest. 2017, 127, 3240–3249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, T.; Zhang, Z. Activated Microglia Facilitate the Transmission of α-Synuclein in Parkinson’s Disease. Neurochem. Int. 2021, 148, 105094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, M.S. Microglia in Parkinson’s Disease. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2019, 1175, 335–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, Y.; Le, W. Differential Roles of M1 and M2 Microglia in Neurodegenerative Diseases. Mol. Neurobiol. 2016, 53, 1181–1194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; He, W.; Zhang, J. A Richer and More Diverse Future for Microglia Phenotypes. Heliyon 2023, 9, e14713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins-Ferreira, R.; Calafell-Segura, J.; Leal, B.; Rodríguez-Ubreva, J.; Martínez-Saez, E.; Mereu, E.; Pinho E Costa, P.; Laguna, A.; Ballestar, E. The Human Microglia Atlas (HuMicA) Unravels Changes in Disease-Associated Microglia Subsets across Neurodegenerative Conditions. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, C.; Chen, B.; Yang, H.; Zhou, X. The Dual Role of Microglia in Alzheimer’s Disease: From Immune Regulation to Pathological Progression. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2025, 17, 1554398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Liu, P.; Zhang, B.; Yuan, Z.; Guo, M.; Zou, X.; Qian, Y.; Deng, S.; Zhu, L.; Cao, X.; et al. Acute Ischemia Induces Spatially and Transcriptionally Distinct Microglial Subclusters. Genome Med. 2023, 15, 109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, H.; Li, H.; Zhang, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Liu, H.; Xu, H.; Zhu, L.; Zhang, G.; Wang, J.; Li, Z.; et al. Microglia Exhibit Distinct Heterogeneity Rather than M1/M2 Polarization within the Early Stage of Acute Ischemic Stroke. Aging Dis. 2023, 14, 2284–2302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balak, C.D.; Han, C.Z.; Glass, C.K. Deciphering Microglia Phenotypes in Health and Disease. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 2024, 84, 102146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, X. Microglia/Macrophage Polarization: Fantasy or Evidence of Functional Diversity? J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. Off. J. Int. Soc. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 2020, 40, S134–S136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, S.; Wang, H.; Yin, Y. Microglia Polarization From M1 to M2 in Neurodegenerative Diseases. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2022, 14, 815347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, R.-H.; Sun, H.-B.; Hu, Z.-L.; Lu, M.; Ding, J.-H.; Hu, G. Kir6.1/K-ATP Channel Modulates Microglia Phenotypes: Implication in Parkinson’s Disease. Cell Death Dis. 2018, 9, 404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, Y.R.; Kang, S.-J.; Kim, J.-M.; Lee, S.-J.; Jou, I.; Joe, E.-H.; Park, S.M. FcγRIIB Mediates the Inhibitory Effect of Aggregated α-Synuclein on Microglial Phagocytosis. Neurobiol. Dis. 2015, 83, 90–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varinou, L.; Ramsauer, K.; Karaghiosoff, M.; Kolbe, T.; Pfeffer, K.; Müller, M.; Decker, T. Phosphorylation of the Stat1 Transactivation Domain Is Required for Full-Fledged IFN-Gamma-Dependent Innate Immunity. Immunity 2003, 19, 793–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Zheng, J.; Xu, S.; Fang, Y.; Wu, Y.; Zeng, J.; Shao, A.; Shi, L.; Lu, J.; Mei, S.; et al. Mer Regulates Microglial/Macrophage M1/M2 Polarization and Alleviates Neuroinflammation Following Traumatic Brain Injury. J. Neuroinflammation 2021, 18, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawrence, T.; Natoli, G. Transcriptional Regulation of Macrophage Polarization: Enabling Diversity with Identity. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2011, 11, 750–761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, Z.; Zhang, W.; Cao, Q.; Zou, L.; Fan, X.; Qi, C.; Yan, Y.; Song, B.; Wu, B. JAK2/STAT3 Pathway Regulates Microglia Polarization Involved in Hippocampal Inflammatory Damage Due to Acute Paraquat Exposure. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2022, 234, 113372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xin, P.; Xu, X.; Deng, C.; Liu, S.; Wang, Y.; Zhou, X.; Ma, H.; Wei, D.; Sun, S. The Role of JAK/STAT Signaling Pathway and Its Inhibitors in Diseases. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2020, 80, 106210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lashgari, N.-A.; Roudsari, N.M.; Momtaz, S.; Sathyapalan, T.; Abdolghaffari, A.H.; Sahebkar, A. The Involvement of JAK/STAT Signaling Pathway in the Treatment of Parkinson’s Disease. J. Neuroimmunol. 2021, 361, 577758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liddelow, S.A.; Guttenplan, K.A.; Clarke, L.E.; Bennett, F.C.; Bohlen, C.J.; Schirmer, L.; Bennett, M.L.; Münch, A.E.; Chung, W.-S.; Peterson, T.C.; et al. Neurotoxic Reactive Astrocytes Are Induced by Activated Microglia. Nature 2017, 541, 481–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tremblay, M.-E.; Cookson, M.R.; Civiero, L. Glial Phagocytic Clearance in Parkinson’s Disease. Mol. Neurodegener. 2019, 14, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayerra, L.; Abellanas, M.A.; Basurco, L.; Tamayo, I.; Conde, E.; Tavira, A.; Trigo, A.; Vidaurre, C.; Vilas, A.; San Martin-Uriz, P.; et al. Nigrostriatal Degeneration Determines Dynamics of Glial Inflammatory and Phagocytic Activity. J. Neuroinflammation 2024, 21, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Chen, M.; Li, H.; Gao, D.; Zhao, L.; Zhu, M. Glial Cells Improve Parkinson’s Disease by Modulating Neuronal Function and Regulating Neuronal Ferroptosis. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2024, 12, 1510897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noh, M.-Y.; Kwon, H.S.; Kwon, M.-S.; Nahm, M.; Jin, H.K.; Bae, J.; Kim, S.H. Biomarkers and Therapeutic Strategies Targeting Microglia in Neurodegenerative Diseases: Current Status and Future Directions. Mol. Neurodegener. 2025, 20, 82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, T.R.F.; Rowe, R.K. Quantifying Microglial Morphology: An Insight into Function. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 2024, 216, 221–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Battaglini, M.; Marino, A.; Montorsi, M.; Carmignani, A.; Ceccarelli, M.C.; Ciofani, G. Nanomaterials as Microglia Modulators in the Treatment of Central Nervous System Disorders. Adv. Healthc. Mater. 2024, 13, 2304180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gopinath, A.; Mackie, P.M.; Phan, L.T.; Tansey, M.G.; Khoshbouei, H. The Complex Role of Inflammation and Gliotransmitters in Parkinson’s Disease. Neurobiol. Dis. 2023, 176, 105940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, K.; Wang, H.; Ilyas, I.; Mahmood, A.; Hou, L. Microglia and Astrocytes Dysfunction and Key Neuroinflammation-Based Biomarkers in Parkinson’s Disease. Brain Sci. 2023, 13, 634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yarkova, E.S.; Grigor’eva, E.V.; Medvedev, S.P.; Pavlova, S.V.; Zakian, S.M.; Malakhova, A.A. IPSC-Derived Astrocytes Contribute to In Vitro Modeling of Parkinson’s Disease Caused by the GBA1 N370S Mutation. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 25, 327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Rus Jacquet, A.; Alpaugh, M.; Denis, H.L.; Tancredi, J.L.; Boutin, M.; Decaestecker, J.; Beauparlant, C.; Herrmann, L.; Saint-Pierre, M.; Parent, M.; et al. The Contribution of Inflammatory Astrocytes to BBB Impairments in a Brain-Chip Model of Parkinson’s Disease. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 3651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, J.-J.; Oh, S.-M.; Kwon, O.-C.; Wulansari, N.; Lee, H.-S.; Chang, M.-Y.; Lee, E.; Sun, W.; Lee, S.-E.; Chang, S.; et al. Cografting Astrocytes Improves Cell Therapeutic Outcomes in a Parkinson’s Disease Model. J. Clin. Investig. 2018, 128, 463–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szeky, B.; Jurakova, V.; Fouskova, E.; Feher, A.; Zana, M.; Karl, V.R.; Farkas, J.; Bodi-Jakus, M.; Zapletalova, M.; Pandey, S.; et al. Efficient Derivation of Functional Astrocytes from Human Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells (hiPSCs). PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0313514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marchetti, B. Nrf2/Wnt Resilience Orchestrates Rejuvenation of Glia-Neuron Dialogue in Parkinson’s Disease. Redox Biol. 2020, 36, 101664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, M.; Nguyen, N.T.P.; Milanese, M.; Bonanno, G. Insights into Human-Induced Pluripotent Stem Cell-Derived Astrocytes in Neurodegenerative Disorders. Biomolecules 2022, 12, 344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Booth, H.D.E.; Hirst, W.D.; Wade-Martins, R. The Role of Astrocyte Dysfunction in Parkinson’s Disease Pathogenesis. Trends Neurosci. 2017, 40, 358–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirsch, E.C.; Standaert, D.G. Ten Unsolved Questions About Neuroinflammation in Parkinson’s Disease. Mov. Disord. Off. J. Mov. Disord. Soc. 2021, 36, 16–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Q.; Liu, Y.; Zhou, J. Neuroinflammation in Parkinson’s Disease and Its Potential as Therapeutic Target. Transl. Neurodegener. 2015, 4, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selvaraj, N.R.; Nandan, D.; Nair, B.G.; Nair, V.A.; Venugopal, P.; Aradhya, R. Oxidative Stress and Redox Imbalance: Common Mechanisms in Cancer Stem Cells and Neurodegenerative Diseases. Cells 2025, 14, 511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- L’ Episcopo, F.; Tirolo, C.; Testa, N.; Caniglia, S.; Morale, M.C.; Marchetti, B. Glia as a Turning Point in the Therapeutic Strategy of Parkinson’s Disease. CNS Neurol. Disord. Drug Targets 2010, 9, 349–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chinta, S.J.; Woods, G.; Rane, A.; Demaria, M.; Campisi, J.; Andersen, J.K. Cellular Senescence and the Aging Brain. Exp. Gerontol. 2015, 68, 3–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Li, Z.; Wang, W.; Zhou, Y.; Li, W.; Wang, Y. Adult Hippocampal Neurogenesis: New Avenues for Treatment of Brain Disorders. Stem Cell Rep. 2025, 20, 102600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramakrishna, K.; Nalla, L.V.; Naresh, D.; Venkateswarlu, K.; Viswanadh, M.K.; Nalluri, B.N.; Chakravarthy, G.; Duguluri, S.; Singh, P.; Rai, S.N.; et al. WNT-β Catenin Signaling as a Potential Therapeutic Target for Neurodegenerative Diseases: Current Status and Future Perspective. Diseases 2023, 11, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Huang, X.; Su, Y.; Yin, G.; Wang, S.; Yu, B.; Li, H.; Qi, J.; Chen, H.; Zeng, W.; et al. Activation of Wnt/β-Catenin Pathway Mitigates Blood–Brain Barrier Dysfunction in Alzheimer’s Disease. Brain 2022, 145, 4474–4488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pascual, D.M.; Jebreili Rizi, D.; Kaur, H.; Marcogliese, P.C. Excess Wnt in Neurological Disease. Biochem. J. 2025, 482, 601–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Grasso, M.; Mascali, C.; L’Episcopo, F. Role of Reactive Astrocytes and Microglia: Wnt/β-Catenin Signaling in Neuroprotection and Repair in Parkinson’s Disease. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 11880. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262411880

Grasso M, Mascali C, L’Episcopo F. Role of Reactive Astrocytes and Microglia: Wnt/β-Catenin Signaling in Neuroprotection and Repair in Parkinson’s Disease. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2025; 26(24):11880. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262411880

Chicago/Turabian StyleGrasso, Margherita, Chiara Mascali, and Francesca L’Episcopo. 2025. "Role of Reactive Astrocytes and Microglia: Wnt/β-Catenin Signaling in Neuroprotection and Repair in Parkinson’s Disease" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 26, no. 24: 11880. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262411880

APA StyleGrasso, M., Mascali, C., & L’Episcopo, F. (2025). Role of Reactive Astrocytes and Microglia: Wnt/β-Catenin Signaling in Neuroprotection and Repair in Parkinson’s Disease. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 26(24), 11880. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262411880