Microproteins in Metabolic Biology: Emerging Functions and Potential Roles as Nutrient-Linked Biomarkers

Abstract

1. Introduction

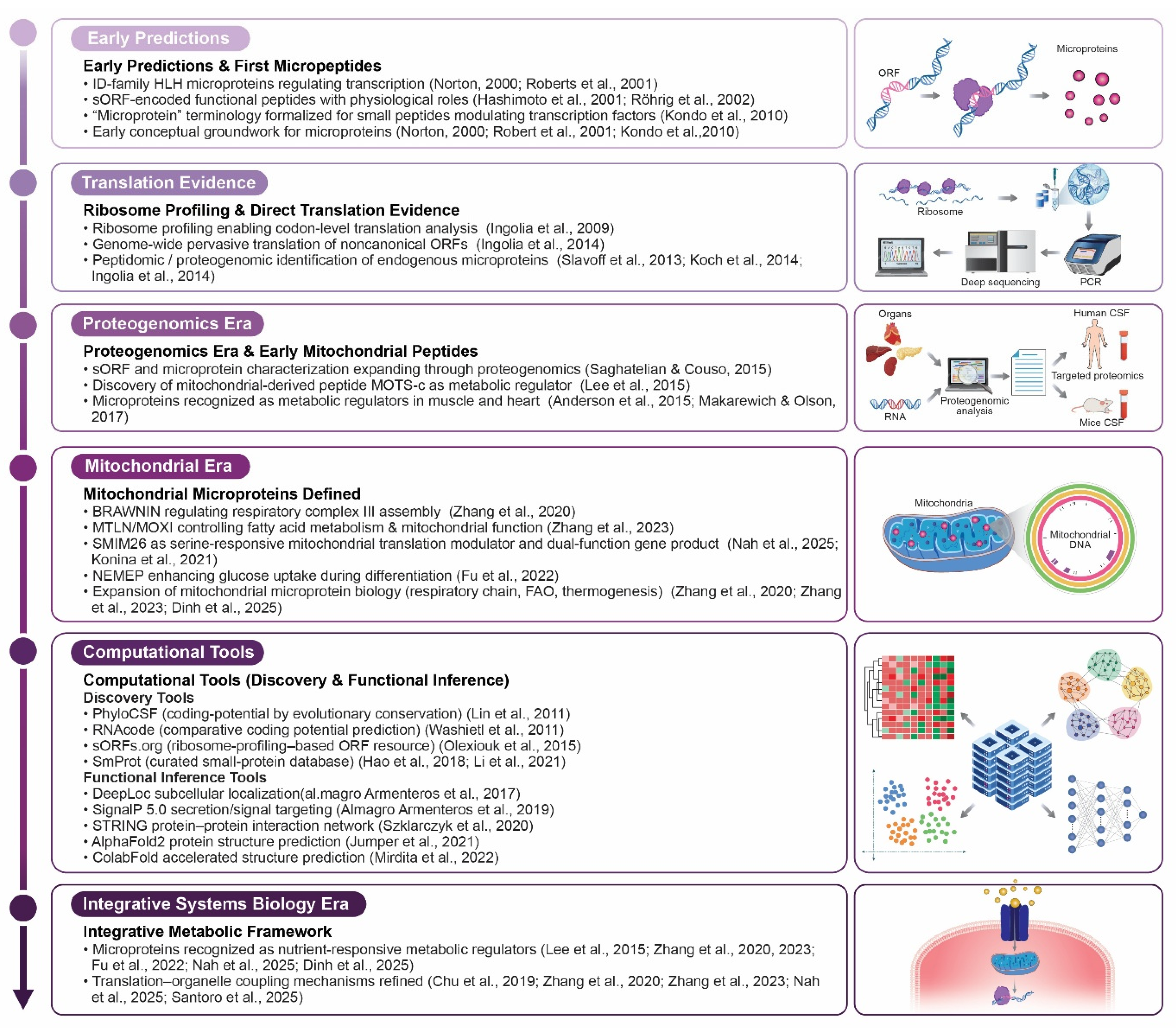

2. Discovery of Nutrient-Responsive Microproteins

2.1. Overview of sORF-Encoded Microproteins in Nutrient Sensing

- (1)

- (2)

- (3)

- (4)

- Stress- and hormone-responsive peptides, such as the mitochondria-derived peptide MOTS-c [52].

2.2. SMIM26 and Serine Availability of Mitochondrial Translation

2.3. NEMEP and Glucose Uptake During Differentiation

3. Mechanistic Paradigm Shift

3.1. Transcriptional/Post-Translational Control Versus Translational Level

3.2. Ribosome-Centered Nutrient Sensing Mediated by Microproteins

4. Integration with Classical Nutrient Pathways

4.1. Comparison of the AMPK–PPAR Axis and Microprotein-Mediated Translation

- (1)

- Fed state (0–3 h post-meal): Nutrient absorption, insulin secretion, and glycogen/lipid storage are predominant.

- (2)

- Post-absorptive/Early fasting (~3–12/18 h): Hepatic glycogenolysis maintains blood glucose.

- (3)

- Fasting (~18–48 h): Glycogen depletion shifts the reliance on adipose lipolysis and hepatic gluconeogenesis.

- (4)

- Starvation (days/weeks): Ketogenesis provides alternative fuels, sparing glucose for obligate tissues such as those of the central nervous system.

4.1.1. AMPK–PPAR Axis in the Fed–Fast Cycle

- -

- Fed state (0–3 h postprandial)

- -

- Early fasting state (3–12/18 h postprandial)

- -

- Fasting state (18–48 h)

- -

- Starvation (days to weeks)

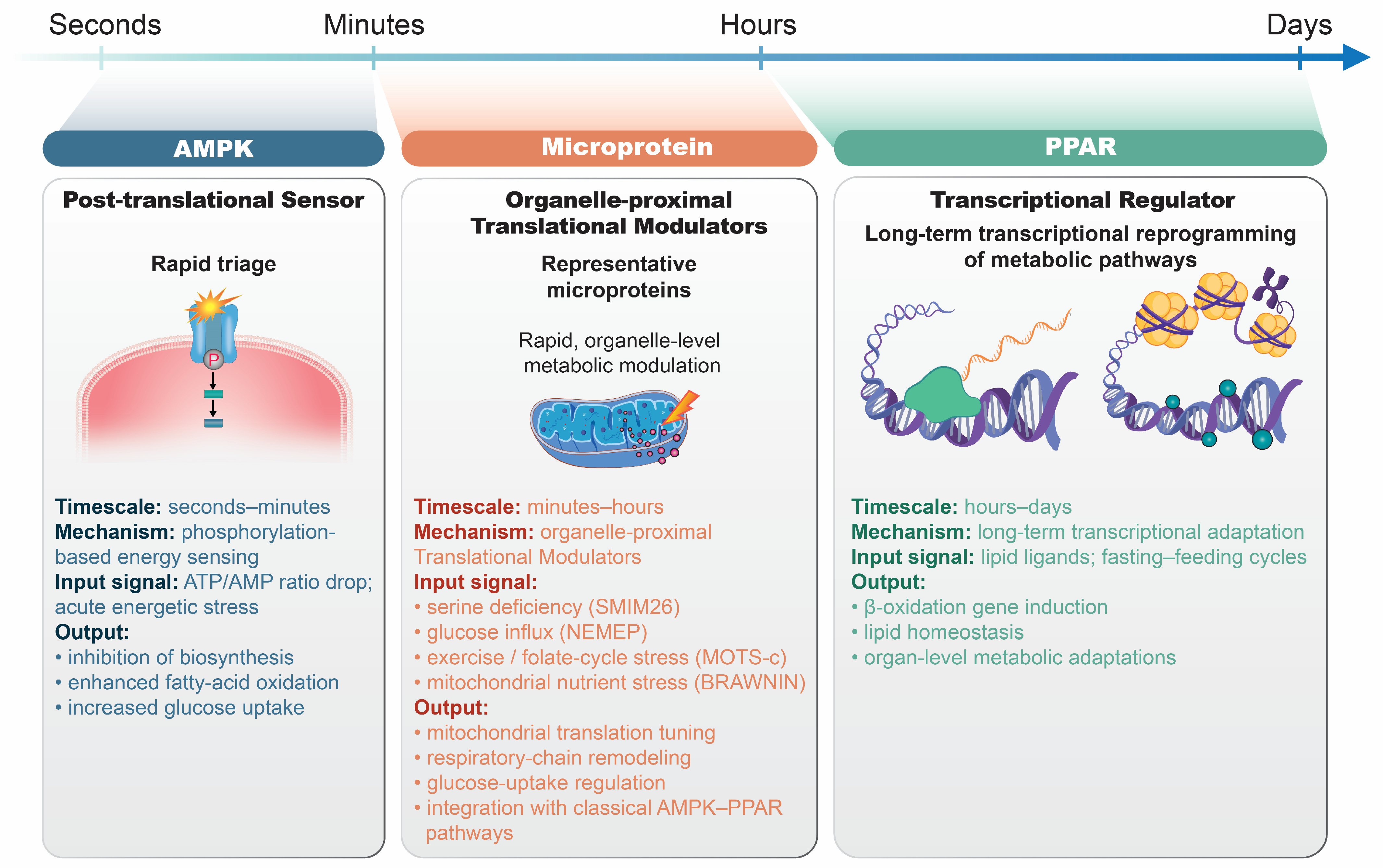

4.1.2. Temporal Dynamics of the AMPK–PPAR Axis and Microprotein

4.1.3. Comparison with Microprotein-Mediated Translational Control

4.2. Crosstalk Between Nutrient Transporters, Mitochondria, and Ribosomes

5. Physiological and Pathological Implications of Nutrient-Sensing Microproteins

5.1. Microproteins in Obesity and Energy Homeostasis

5.2. Therapeutic Potential of Microproteins in Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus (T2DM)

5.2.1. Microproteins Implicated in Glucose and Insulin Regulation

MOTS-c

Adrenomedullins (ADMs)

Mitoregulin

HN

BRAWNIN

Mitolamban (Mtlbn)

PIGBOS

5.2.2. Translational and Clinical Applications in Diabetes Management

5.3. Microproteins in Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease (NAFLD) and Lipid Metabolism

5.4. Stress-Responsive Microproteins and Cellular Protection

5.4.1. Ubiquitination Basics

5.4.2. Why UFD1s Is Different

6. Diet-Responsive Microproteins and Nutritional Regulation

6.1. Adaptive Microproteins Governing Brown Adipose Thermogenesis

6.2. Nutritional Targeting of Mitochondrial Microproteins

6.3. Caloric Restriction, Fasting, and sORF Expression

6.3.1. Caloric Restriction/Rapamycin Remodel Non-Canonical ORF Translation

6.3.2. Adropin as a Nutrient-Responsive Microprotein Hormone

CR and Adropin

Adropin, a Metabolic Modulator

6.4. Nutrient-Sensitive Peptides as Endocrine Regulators

6.4.1. Nnat Links Glucose Sensing

6.4.2. lncRNA TUNAR Encodes Dual Microproteins with Metabolic and Neural Functions

Microproteins as β-Cell and Neuronal Lineage Regulators

Microprotein Complementing Metabolic Roles of pTUNAR

7. Challenges and Future Directions

7.1. Functional Validation Bottlenecks

7.2. Lack of Annotation in Reference Genomes

7.3. Need for Proteogenomic and Ribosome-Profiling Integration

8. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AICAR | 5-Aminoimidazole-4-carboxamide ribonucleotide |

| ACC | Acetyl-CoA carboxylase |

| AC | Adenylate cyclase |

| ADM | Adrenomedullin |

| ADM2 | Adrenomedullin 2 |

| AMP | Adenosine monophosphate |

| AMPK | AMP-activated protein kinase |

| ATP | Adenosine triphosphate |

| bHLH | Basic helix–loop–helix |

| BAT | Brown adipose tissue |

| BNLN | β-cell and neuronal lineage regulator |

| CIII | Complex III (cytochrome bc1 complex) |

| CLR | Calcitonin receptor-like receptor |

| ChREBP | Carbohydrate response element-binding protein |

| CR | Caloric restriction |

| CPT1B | Carnitine palmitoyltransferase 1B |

| CPT1 | Carnitine palmitoyltransferase 1 |

| DUB | Deubiquitinating enzyme |

| eNOS | Endothelial nitric oxide synthase |

| ENHO | Energy homeostasis-associated gene |

| ER | Endoplasmic reticulum |

| FAO | Fatty acid oxidation |

| FAM210A | Family with sequence similarity 210 member A |

| Gαs | Guanine nucleotide-binding protein alpha subunit (stimulatory) |

| GLUT | Glucose transporter |

| GLUT1 | Glucose transporter type 1 |

| GLUT3 | Glucose transporter type 3 |

| GLUT4 | Glucose transporter type 4 |

| HIF-1 | Hypoxia-inducible factor-1 |

| HN | Humanin |

| ID | Inhibitor of DNA binding |

| JNK | c-Jun N-terminal kinase |

| KO | Knockout |

| lncRNA | Long non-coding RNA |

| MAPK | Mitogen-activated protein kinase |

| MAP3K20 | Mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase kinase 20 (ZAKα) |

| MARCHF7 | Membrane-associated ring-CH-type finger 7 |

| mRNA | Messenger RNA |

| MIEF1 | Mitochondrial elongation factor 1 |

| MICT1 | Microprotein for thermogenesis 1 |

| MITR | Mitochondrial ribosome (mitoribosome) |

| MitoK_ATP | Mitochondrial ATP-sensitive potassium channel |

| MOTS-c | Mitochondrial open reading frame of the 12S rRNA type-c |

| mTORC1 | Mechanistic target of rapamycin complex 1 |

| Mtln | Mitoregulin |

| Mtlbn | Mitolamban |

| NADH | Nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (reduced form) |

| NAFLD | Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease |

| NASH | Nonalcoholic steatohepatitis |

| ND5 | NADH dehydrogenase subunit 5 |

| NEMEP | Non-coding RNA expressed in mesoderm-inducing cells encoded with peptide |

| Nnat | Neuronatin |

| OXPHOS | Oxidative phosphorylation |

| pTUNAR | Peptide encoded by TUNAR lncRNA (neural isoform) |

| PKA | Protein kinase A |

| PP2B | Protein phosphatase 2B (Calcineurin) |

| PPAR | Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor |

| PPARα | Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor alpha |

| PPARγ | Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma |

| PPARδ | Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor delta |

| PGC-1α | Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma coactivator 1-alpha |

| PTP1B | Protein tyrosine phosphatase 1B |

| RAMP | Receptor activity-modifying protein |

| RAMP2 | Receptor activity-modifying protein 2 |

| RAMP3 | Receptor activity-modifying protein 3 |

| RIIβ | Protein kinase A regulatory subunit II beta |

| RNA | Ribonucleic acid |

| RNP | Ribonucleoprotein |

| sORF | Small open reading frame |

| SERCA | Sarco/endoplasmic reticulum Ca2+-ATPase |

| SFXN | Sideroflexin |

| SFXN1 | Sideroflexin 1 |

| SFXN2 | Sideroflexin 2 |

| SMIM26 | Small integral membrane protein 26 |

| TCA | Tricarboxylic acid cycle |

| TG | Triglyceride |

| TUNAR | TUNA RNA (long non-coding RNA, also known as LINC00617) |

| T2DM | Type 2 diabetes mellitus |

| UCP1 | Uncoupling protein 1 |

| UFD1s | Ubiquitin fusion degradation 1 short isoform |

| UPR | Unfolded protein response |

| uORF | Upstream open reading frame |

| ZAKα | Sterile alpha motif and leucine zipper-containing kinase alpha |

References

- Hassel, K.R.; Brito-Estrada, O.; Makarewich, C.A. Microproteins: Overlooked regulators of physiology and disease. iScience 2023, 26, 106781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Claverie, J.M. Computational methods for the identification of genes in vertebrate genomic sequences. Hum. Mol. Genet. 1997, 6, 1735–1744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohsen, J.J.; Martel, A.A.; Slavoff, S.A. Microproteins-Discovery, structure, and function. Proteomics 2023, 23, e2100211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Qu, L.; Sang, L.; Wu, X.; Jiang, A.; Liu, J.; Lin, A. Micropeptides translated from putative long non-coding RNAs. Acta Biochim. Biophys. Sin. 2022, 54, 292–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, X.; Zhang, K.; Xun, C.; Chu, T.; Liang, S.; Zeng, Y.; Liu, Z. Small Open Reading Frame-Encoded Micro-Peptides: An Emerging Protein World. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 10562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsumoto, A.; Pasut, A.; Matsumoto, M.; Yamashita, R.; Fung, J.; Monteleone, E.; Saghatelian, A.; Nakayama, K.I.; Clohessy, J.G.; Pandolfi, P.P. mTORC1 and muscle regeneration are regulated by the LINC00961-encoded SPAR polypeptide. Nature 2017, 541, 228–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Y.; Tang, R.; Li, B.; Cheng, L.; Ye, S.; Yang, T.; Han, Y.C.; Liu, C.; Dong, Y.; Qu, L.H.; et al. The cardiac translational landscape reveals that micropeptides are new players involved in cardiomyocyte hypertrophy. Mol. Ther. 2021, 29, 2253–2267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anderson, D.M.; Makarewich, C.A.; Anderson, K.M.; Shelton, J.M.; Bezprozvannaya, S.; Bassel-Duby, R.; Olson, E.N. Widespread control of calcium signaling by a family of SERCA-inhibiting micropeptides. Sci. Signal. 2016, 9, ra119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.Y.; Gao, Q.; Sun, Y.; Qiu, X.B. Biochemical targets of the micropeptides encoded by lncRNAs. Noncoding RNA Res. 2024, 9, 964–969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, Y.; Ran, Y.; Li, H.; Wen, J.; Cui, X.; Zhang, X.; Guan, X.; Cheng, M. Micropeptides: Origins, identification, and potential role in metabolism-related diseases. J. Zhejiang Univ. Sci. B 2023, 24, 1106–1122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Lima, N.G.; Ma, J.; Winkler, L.; Chu, Q.; Loh, K.H.; Corpuz, E.O.; Budnik, B.A.; Lykke-Andersen, J.; Saghatelian, A.; Slavoff, S.A. A human microprotein that interacts with the mRNA decapping complex. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2017, 13, 174–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.J.; Guerrero, N.; Wassef, G.; Xiao, J.; Mehta, H.H.; Cohen, P.; Yen, K. The mitochondrial-derived peptide humanin activates the ERK1/2, AKT, and STAT3 signaling pathways and has age-dependent signaling differences in the hippocampus. Oncotarget 2016, 7, 46899–46912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yen, K.; Lee, C.; Mehta, H.; Cohen, P. The emerging role of the mitochondrial-derived peptide humanin in stress resistance. J. Mol. Endocrinol. 2013, 50, R11–R19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Makarewich, C.A.; Bezprozvannaya, S.; Gibson, A.M.; Bassel-Duby, R.; Olson, E.N. Gene Therapy with the DWORF Micropeptide Attenuates Cardiomyopathy in Mice. Circ. Res. 2020, 127, 1340–1342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Staudt, A.C.; Wenkel, S. Regulation of protein function by ‘microProteins’. EMBO Rep. 2011, 12, 35–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Wang, S.; Wang, J.; Guo, X.; Song, Y.; Fu, K.; Gao, Z.; Liu, D.; He, W.; Yang, L.-L. Energy metabolism in health and diseases. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2025, 10, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chun, Y.; Kim, J. AMPK-mTOR Signaling and Cellular Adaptations in Hypoxia. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 9765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cui, Y.; Chen, J.; Zhang, Z.; Shi, H.; Sun, W.; Yi, Q. The role of AMPK in macrophage metabolism, function and polarisation. J. Transl. Med. 2023, 21, 892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barish, G.D.; Narkar, V.A.; Evans, R.M. PPAR delta: A dagger in the heart of the metabolic syndrome. J. Clin. Investig. 2006, 116, 590–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heidenreich, S.; Weber, P.; Stephanowitz, H.; Petricek, K.M.; Schütte, T.; Oster, M.; Salo, A.M.; Knauer, M.; Goehring, I.; Yang, N.; et al. The glucose-sensing transcription factor ChREBP is targeted by proline hydroxylation. J. Biol. Chem. 2020, 295, 17158–17168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziello, J.E.; Jovin, I.S.; Huang, Y. Hypoxia-Inducible Factor (HIF)-1 regulatory pathway and its potential for therapeutic intervention in malignancy and ischemia. Yale J. Biol. Med. 2007, 80, 51–60. [Google Scholar]

- Nah, J.; Mahendran, S.; Kerouanton, B.; Cui, L.; Hock, D.H.; Cabrera-Orefice, A.; Dunlap, K.; Robinson, D.; Tung, D.W.H.; Leong, S.H.; et al. Microprotein SMIM26 drives oxidative metabolism via serine-responsive mitochondrial translation. Mol. Cell 2025, 85, 2759–2775.e12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ho, C.W.; Lee, J.W.; Shin, C.H.; Min, K.W. LncRNA-Encoded Micropeptides: Expression Validation, Translational Mechanisms, and Roles in Cellular Metabolism. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 5913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, W.; Zhang, L.; Lin, Y.; Rao, X.; Wang, X.; Hua, F.; Ying, J. Mitochondria-derived peptide MOTS-c: Effects and mechanisms related to stress, metabolism and aging. J. Transl. Med. 2023, 21, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez, T.F.; Lyons-Abbott, S.; Bookout, A.L.; De Souza, E.V.; Donaldson, C.; Vaughan, J.M.; Lau, C.; Abramov, A.; Baquero, A.F.; Baquero, K.; et al. Profiling mouse brown and white adipocytes to identify metabolically relevant small ORFs and functional microproteins. Cell Metab. 2023, 35, 166–183.e11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saghatelian, A.; Couso, J.P. Discovery and characterization of smORF-encoded bioactive polypeptides. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2015, 11, 909–916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Lee, R.; Buljan, M.; Lang, B.; Weatheritt, R.J.; Daughdrill, G.W.; Dunker, A.K.; Fuxreiter, M.; Gough, J.; Gsponer, J.; Jones, D.T.; et al. Classification of Intrinsically Disordered Regions and Proteins. Chem. Rev. 2014, 114, 6589–6631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jumper, J.; Evans, R.; Pritzel, A.; Green, T.; Figurnov, M.; Ronneberger, O.; Tunyasuvunakool, K.; Bates, R.; Žídek, A.; Potapenko, A.; et al. Highly accurate protein structure prediction with AlphaFold. Nature 2021, 596, 583–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirdita, M.; Schütze, K.; Moriwaki, Y.; Heo, L.; Ovchinnikov, S.; Steinegger, M. ColabFold: Making protein folding accessible to all. Nat. Methods 2022, 19, 679–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, J.; DeBerardinis, R.J. Mechanisms and Implications of Metabolic Heterogeneity in Cancer. Cell Metab. 2019, 30, 434–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hashimoto, Y.; Niikura, T.; Tajima, H.; Yasukawa, T.; Sudo, H.; Ito, Y.; Kita, Y.; Kawasumi, M.; Kouyama, K.; Doyu, M.; et al. A rescue factor abolishing neuronal cell death by a wide spectrum of familial Alzheimer’s disease genes and Aβ. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2001, 98, 6336–6341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Röhrig, H.; Schmidt, J.; Miklashevichs, E.; Schell, J.; John, M. Soybean ENOD40 encodes two peptides that bind to sucrose synthase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2002, 99, 1915–1920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kondo, T.; Plaza, S.; Zanet, J.; Benrabah, E.; Valenti, P.; Hashimoto, Y.; Kobayashi, S.; Payre, F.; Kageyama, Y. Small peptides switch the transcriptional activity of Shavenbaby during Drosophila embryogenesis. Science 2010, 329, 336–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ingolia, N.T.; Hussmann, J.A.; Weissman, J.S. Ribosome Profiling: Global Views of Translation. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2019, 11, a032698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, J.; Ward, C.C.; Jungreis, I.; Slavoff, S.A.; Schwaid, A.G.; Neveu, J.; Budnik, B.A.; Kellis, M.; Saghatelian, A. Discovery of human sORF-encoded polypeptides (SEPs) in cell lines and tissue. J. Proteome Res. 2014, 13, 1757–1765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ingolia, N.T.; Brar, G.A.; Stern-Ginossar, N.; Harris, M.S.; Talhouarne, G.J.S.; Jackson, S.E.; Wills, M.R.; Weissman, J.S. Ribosome Profiling Reveals Pervasive Translation Outside of Annotated Protein-Coding Genes. Cell Rep. 2014, 8, 1365–1379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, M.F.; Jungreis, I.; Kellis, M. PhyloCSF: A comparative genomics method to distinguish protein coding and non-coding regions. Bioinformatics 2011, 27, i275–i282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olexiouk, V.; Crappé, J.; Verbruggen, S.; Verhegen, K.; Martens, L.; Menschaert, G. sORFs.org: A repository of small ORFs identified by ribosome profiling. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015, 44, D324–D329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clauwaert, J.; Menschaert, G.; Waegeman, W. DeepRibo: A neural network for precise gene annotation of prokaryotes by combining ribosome profiling signal and binding site patterns. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019, 47, e36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, Y.; Zhang, L.; Niu, Y.; Cai, T.; Luo, J.; He, S.; Zhang, B.; Zhang, D.; Qin, Y.; Yang, F.; et al. SmProt: A database of small proteins encoded by annotated coding and non-coding RNA loci. Brief. Bioinform. 2018, 19, 636–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almagro Armenteros, J.J.; Sønderby, C.K.; Sønderby, S.K.; Nielsen, H.; Winther, O. DeepLoc: Prediction of protein subcellular localization using deep learning. Bioinformatics 2017, 33, 3387–3395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almagro Armenteros, J.J.; Tsirigos, K.D.; Sønderby, C.K.; Petersen, T.N.; Winther, O.; Brunak, S.; von Heijne, G.; Nielsen, H. SignalP 5.0 improves signal peptide predictions using deep neural networks. Nat. Biotechnol. 2019, 37, 420–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szklarczyk, D.; Gable, A.L.; Nastou, K.C.; Lyon, D.; Kirsch, R.; Pyysalo, S.; Doncheva, N.T.; Legeay, M.; Fang, T.; Bork, P.; et al. The STRING database in 2021: Customizable protein–protein networks, and functional characterization of user-uploaded gene/measurement sets. Nucleic Acids Res. 2020, 49, D605–D612, Erratum in Nucleic Acids Res. 2021, 49, 10800. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkab835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Consortium, T.G.O. The Gene Ontology resource: Enriching a GOld mine. Nucleic Acids Res. 2020, 49, D325–D334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Konina, D.; Sparber, P.; Viakhireva, I.; Filatova, A.; Skoblov, M. Investigation of LINC00493/SMIM26 Gene Suggests Its Dual Functioning at mRNA and Protein Level. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 8477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roberts, E.C.; Deed, R.W.; Inoue, T.; Norton, J.D.; Sharrocks, A.D. Id helix-loop-helix proteins antagonize pax transcription factor activity by inhibiting DNA binding. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2001, 21, 524–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norton, J.D. ID helix-loop-helix proteins in cell growth, differentiation and tumorigenesis. J. Cell Sci. 2000, 113, 3897–3905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Guo, Y.; Fidelito, G.; Robinson, D.R.L.; Liang, C.; Lim, R.; Bichler, Z.; Guo, R.; Wu, G.; Xu, H.; et al. LINC00116-encoded microprotein mitoregulin regulates fatty acid metabolism at the mitochondrial outer membrane. iScience 2023, 26, 107558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Reljić, B.; Liang, C.; Kerouanton, B.; Francisco, J.C.; Peh, J.H.; Mary, C.; Jagannathan, N.S.; Olexiouk, V.; Tang, C.; et al. Mitochondrial peptide BRAWNIN is essential for vertebrate respiratory complex III assembly. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 1312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinh, J.; Yi, D.; Lin, F.; Xue, P.; Holloway, N.D.; Xie, Y.; Ibe, N.U.; Nguyen, H.P.; Viscarra, J.A.; Wang, Y.; et al. The microprotein C16orf74/MICT1 promotes thermogenesis in brown adipose tissue. EMBO J. 2025, 44, 3381–3412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Shao, F.; Qian, Q.; Yu, W.; Zhang, Z.; Chen, B.; Su, D.; Guo, Y.; Phan, A.V.; Song, L.S.; et al. A putative long noncoding RNA-encoded micropeptide maintains cellular homeostasis in pancreatic β cells. Mol. Ther. Nucleic Acids 2021, 26, 307–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Makarewich, C.A.; Olson, E.N. Mining for Micropeptides. Trends Cell Biol. 2017, 27, 685–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, L.; Zhu, Y.; Deng, C.; Liang, Z.; Chen, J.; Chen, Y.; Wang, X.; Liu, Y.; Tian, Y.; Yang, Y. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma coactivator-1 (PGC-1) family in physiological and pathophysiological process and diseases. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2024, 9, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, H.; Wang, T.; Kong, X.; Yan, K.; Yang, Y.; Cao, J.; Yuan, Y.; Wang, N.; Kee, K.; Lu, Z.J.; et al. A Nodal enhanced micropeptide NEMEP regulates glucose uptake during mesendoderm differentiation of embryonic stem cells. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 3984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santoro, M.M. The intersection between metabolism and translation through a subcellular lens. Trends Cell Biol. 2025; in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, C.; Zeng, J.; Drew, B.G.; Sallam, T.; Martin-Montalvo, A.; Wan, J.; Kim, S.J.; Mehta, H.; Hevener, A.L.; de Cabo, R.; et al. The mitochondrial-derived peptide MOTS-c promotes metabolic homeostasis and reduces obesity and insulin resistance. Cell Metab. 2015, 21, 443–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, D.M.; Anderson, K.M.; Chang, C.L.; Makarewich, C.A.; Nelson, B.R.; McAnally, J.R.; Kasaragod, P.; Shelton, J.M.; Liou, J.; Bassel-Duby, R.; et al. A micropeptide encoded by a putative long noncoding RNA regulates muscle performance. Cell 2015, 160, 595–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, Q.; Martinez, T.F.; Novak, S.W.; Donaldson, C.J.; Tan, D.; Vaughan, J.M.; Chang, T.; Diedrich, J.K.; Andrade, L.; Kim, A.; et al. Regulation of the ER stress response by a mitochondrial microprotein. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 4883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slavoff, S.A.; Mitchell, A.J.; Schwaid, A.G.; Cabili, M.N.; Ma, J.; Levin, J.Z.; Karger, A.D.; Budnik, B.A.; Rinn, J.L.; Saghatelian, A. Peptidomic discovery of short open reading frame-encoded peptides in human cells. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2013, 9, 59–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ingolia, N.T.; Ghaemmaghami, S.; Newman, J.R.S.; Weissman, J.S. Genome-Wide Analysis in Vivo of Translation with Nucleotide Resolution Using Ribosome Profiling. Science 2009, 324, 218–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Washietl, S.; Findeiss, S.; Müller, S.A.; Kalkhof, S.; von Bergen, M.; Hofacker, I.L.; Stadler, P.F.; Goldman, N. RNAcode: Robust discrimination of coding and noncoding regions in comparative sequence data. RNA 2011, 17, 578–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koch, A.; Gawron, D.; Steyaert, S.; Ndah, E.; Crappé, J.; De Keulenaer, S.; De Meester, E.; Ma, M.; Shen, B.; Gevaert, K.; et al. A proteogenomics approach integrating proteomics and ribosome profiling increases the efficiency of protein identification and enables the discovery of alternative translation start sites. Proteomics 2014, 14, 2688–2698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinberg, G.R.; Carling, D. AMP-activated protein kinase: The current landscape for drug development. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2019, 18, 527–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardie, D.G.; Ross, F.A.; Hawley, S.A. AMP-activated protein kinase: A target for drugs both ancient and modern. Chem. Biol. 2012, 19, 1222–1236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Issemann, I.; Green, S. Activation of a member of the steroid hormone receptor superfamily by peroxisome proliferators. Nature 1990, 347, 645–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uyeda, K.; Repa, J.J. Carbohydrate response element binding protein, ChREBP, a transcription factor coupling hepatic glucose utilization and lipid synthesis. Cell Metab. 2006, 4, 107–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.; Sarkar, T.; Jakubison, B.; Gadomski, S.; Spradlin, A.; Gudmundsson, K.O.; Keller, J.R. Inhibitor of DNA binding proteins revealed as orchestrators of steady state, stress and malignant hematopoiesis. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 934624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Straub, D.; Wenkel, S. Cross-Species Genome-Wide Identification of Evolutionary Conserved MicroProteins. Genome Biol. Evol. 2017, 9, 777–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeasmin, F.; Yada, T.; Akimitsu, N. Micropeptides Encoded in Transcripts Previously Identified as Long Noncoding RNAs: A New Chapter in Transcriptomics and Proteomics. Front. Genet. 2018, 9, 144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ling, F.; Kang, B.; Sun, X.H. Id proteins: Small molecules, mighty regulators. Curr. Top. Dev. Biol. 2014, 110, 189–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ovens, A.J.; Scott, J.W.; Langendorf, C.G.; Kemp, B.E.; Oakhill, J.S.; Smiles, W.J. Post-Translational Modifications of the Energy Guardian AMP-Activated Protein Kinase. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 1229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Li, Z.; Li, J.; Peng, Y. Small open reading frame-encoded microproteins in cancer: Identification, biological functions and clinical significance. Mol. Cancer 2025, 24, 105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wadding-Lee, C.A.; Makarewich, C.A. Microproteins in Metabolism. Cells 2025, 14, 859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Millership, S.J.; Da Silva Xavier, G.; Choudhury, A.I.; Bertazzo, S.; Chabosseau, P.; Pedroni, S.M.; Irvine, E.E.; Montoya, A.; Faull, P.; Taylor, W.R.; et al. Neuronatin regulates pancreatic β cell insulin content and secretion. J. Clin. Investig. 2018, 128, 3369–3381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, K.; Wu, D.; Wang, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Shen, H.; Yao, J.; Huang, X.; Li, X.; Zhou, Z.; Wang, Z.; et al. The mitochondrial calcium uniporter engages UCP1 to form a thermoporter that promotes thermogenesis. Cell Metab. 2022, 34, 1325–1341.e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeFronzo, R.A. Pathogenesis of type 2 diabetes mellitus. Med. Clin. N. Am. 2004, 88, 787–835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prentki, M.; Nolan, C.J. Islet beta cell failure in type 2 diabetes. J. Clin. Investig. 2006, 116, 1802–1812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kersten, S. Integrated physiology and systems biology of PPARα. Mol. Metab. 2014, 3, 354–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krako Jakovljevic, N.; Pavlovic, K.; Jotic, A.; Lalic, K.; Stoiljkovic, M.; Lukic, L.; Milicic, T.; Macesic, M.; Stanarcic Gajovic, J.; Lalic, N.M. Targeting Mitochondria in Diabetes. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 6642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Averina, O.A.; Permyakov, O.A.; Emelianova, M.A.; Guseva, E.A.; Grigoryeva, O.O.; Lovat, M.L.; Egorova, A.E.; Grinchenko, A.V.; Kumeiko, V.V.; Marey, M.V.; et al. Kidney-Related Function of Mitochondrial Protein Mitoregulin. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 9106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Makarewich, C.A.; Munir, A.Z.; Bezprozvannaya, S.; Gibson, A.M.; Young Kim, S.; Martin-Sandoval, M.S.; Mathews, T.P.; Szweda, L.I.; Bassel-Duby, R.; Olson, E.N. The cardiac-enriched microprotein mitolamban regulates mitochondrial respiratory complex assembly and function in mice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2022, 119, e2120476119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lowell, B.B.; Shulman, G.I. Mitochondrial Dysfunction and Type 2 Diabetes. Science 2005, 307, 384–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boudina, S.; Abel, E.D. Diabetic Cardiomyopathy Revisited. Circulation 2007, 115, 3213–3223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Shi, Y.; Li, W.; Han, X.; Lin, X.; Liu, D.; Lin, Y.; Shen, L. Knockdown of BRAWNIN minimally affect mitochondrial complex III assembly in human cells. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Mol. Cell Res. 2024, 1871, 119601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sergi, D.; Naumovski, N.; Heilbronn, L.K.; Abeywardena, M.; O’Callaghan, N.; Lionetti, L.; Luscombe-Marsh, N. Mitochondrial (Dys)function and Insulin Resistance: From Pathophysiological Molecular Mechanisms to the Impact of Diet. Front. Physiol. 2019, 10, 532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pacifici, F.; Malatesta, G.; Mammi, C.; Pastore, D.; Marzolla, V.; Ricordi, C.; Chiereghin, F.; Infante, M.; Donadel, G.; Curcio, F.; et al. A Novel Mix of Polyphenols and Micronutrients Reduces Adipogenesis and Promotes White Adipose Tissue Browning via UCP1 Expression and AMPK Activation. Cells 2023, 12, 714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reynolds, J.C.; Lai, R.W.; Woodhead, J.S.T.; Joly, J.H.; Mitchell, C.J.; Cameron-Smith, D.; Lu, R.; Cohen, P.; Graham, N.A.; Benayoun, B.A.; et al. MOTS-c is an exercise-induced mitochondrial-encoded regulator of age-dependent physical decline and muscle homeostasis. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kong, B.S.; Min, S.H.; Lee, C.; Cho, Y.M. Mitochondrial-encoded MOTS-c prevents pancreatic islet destruction in autoimmune diabetes. Cell Rep. 2021, 36, 109447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Wei, X.; Wei, P.; Lu, H.; Zhong, L.; Tan, J.; Liu, H.; Liu, Z. MOTS-c Functionally Prevents Metabolic Disorders. Metabolites 2023, 13, 125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boutari, C.; Pappas, P.D.; Theodoridis, T.D.; Vavilis, D. Humanin and diabetes mellitus: A review of in vitro and in vivo studies. World J. Diabetes 2022, 13, 213–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuliawat, R.; Klein, L.; Gong, Z.; Nicoletta-Gentile, M.; Nemkal, A.; Cui, L.; Bastie, C.; Su, K.; Huffman, D.; Surana, M.; et al. Potent humanin analog increases glucose-stimulated insulin secretion through enhanced metabolism in the β cell. Faseb J. 2013, 27, 4890–4898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muzumdar, R.H.; Huffman, D.M.; Atzmon, G.; Buettner, C.; Cobb, L.J.; Fishman, S.; Budagov, T.; Cui, L.; Einstein, F.H.; Poduval, A.; et al. Humanin: A novel central regulator of peripheral insulin action. PLoS ONE 2009, 4, e6334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, H.; Kang, R.; Bae, S.; Yoon, Y. AICAR, an activator of AMPK, inhibits adipogenesis via the WNT/β-catenin pathway in 3T3-L1 adipocytes. Int. J. Mol. Med. 2011, 28, 65–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coradduzza, D.; Congiargiu, A.; Chen, Z.; Cruciani, S.; Zinellu, A.; Carru, C.; Medici, S. Humanin and Its Pathophysiological Roles in Aging: A Systematic Review. Biology 2023, 12, 558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, K.G.; Trevaskis, J.L.; Lam, D.D.; Sutton, G.M.; Koza, R.A.; Chouljenko, V.N.; Kousoulas, K.G.; Rogers, P.M.; Kesterson, R.A.; Thearle, M.; et al. Identification of adropin as a secreted factor linking dietary macronutrient intake with energy homeostasis and lipid metabolism. Cell Metab. 2008, 8, 468–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasanpour-Segherlou, Z.; Butler, A.A.; Candelario-Jalil, E.; Hoh, B.L. Role of the Unique Secreted Peptide Adropin in Various Physiological and Disease States. Biomolecules 2024, 14, 1613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stevens, J.R.; Kearney, M.L.; St-Onge, M.P.; Stanhope, K.L.; Havel, P.J.; Kanaley, J.A.; Thyfault, J.P.; Weiss, E.P.; Butler, A.A. Inverse association between carbohydrate consumption and plasma adropin concentrations in humans. Obesity 2016, 24, 1731–1740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, S.; Ghoshal, S.; Stevens, J.R.; McCommis, K.S.; Gao, S.; Castro-Sepulveda, M.; Mizgier, M.L.; Girardet, C.; Kumar, K.G.; Galgani, J.E.; et al. Hepatocyte expression of the micropeptide adropin regulates the liver fasting response and is enhanced by caloric restriction. J. Biol. Chem. 2020, 295, 13753–13768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rooban, S.; Arul Senghor, K.A.; Vinodhini, V.M.; Kumar, J.S. Adropin: A crucial regulator of cardiovascular health and metabolic balance. Metab. Open 2024, 23, 100299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, I.; D’Souza, C.; Singh, J.; Adeghate, E. Adropin’s Role in Energy Homeostasis and Metabolic Disorders. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 8318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, S.; McMillan, R.P.; Zhu, Q.; Lopaschuk, G.D.; Hulver, M.W.; Butler, A.A. Therapeutic effects of adropin on glucose tolerance and substrate utilization in diet-induced obese mice with insulin resistance. Mol. Metab. 2015, 4, 310–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghoshal, S.; Stevens, J.R.; Billon, C.; Girardet, C.; Sitaula, S.; Leon, A.S.; Rao, D.C.; Skinner, J.S.; Rankinen, T.; Bouchard, C.; et al. Adropin: An endocrine link between the biological clock and cholesterol homeostasis. Mol. Metab. 2018, 8, 51–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joseph, R.M. Neuronatin gene: Imprinted and misfolded: Studies in Lafora disease, diabetes and cancer may implicate NNAT-aggregates as a common downstream participant in neuronal loss. Genomics 2014, 103, 183–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qiu, H.; Schlegel, V. Impact of nutrient overload on metabolic homeostasis. Nutr. Rev. 2018, 76, 693–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, H.; Gang, X.; He, G.; Liu, Y.; Wang, Y.; Zhao, X.; Wang, G. The Molecular Mechanisms Underlying Mitochondria-Associated Endoplasmic Reticulum Membrane-Induced Insulin Resistance. Front. Endocrinol. 2020, 11, 592129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Wang, X.; Liu, X.; Shan, G.; Chen, L. A UFD1 variant encoding a microprotein modulates UFD1f and IPMK ubiquitination to play pivotal roles in anti-stress responses. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 6695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, O.R., Jr.; Serna, J.D.C.; Caldeira da Silva, C.C.; Camara, H.; Kodani, S.D.; Festuccia, W.T.; Tseng, Y.H.; Kowaltowski, A.J. Mitochondrial ATP-sensitive K(+) channels (MitoK(ATP)) regulate brown adipocyte differentiation and metabolism. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 2025, 329, C574–C584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narimatsu, Y.; Kato, M.; Iwakoshi-Ukena, E.; Moriwaki, S.; Ogasawara, A.; Furumitsu, M.; Ukena, K. Neurosecretory Protein GM-Expressing Neurons Participate in Lipid Storage and Inflammation in Newly Developed Cre Driver Male Mice. Biomedicines 2023, 11, 3230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, H.; Lai, C.C.; Bonnavion, R.; Alnouri, M.W.; Wang, S.; Roquid, K.A.; Kawase, H.; Campos, D.; Chen, M.; Weinstein, L.S.; et al. Endothelial insulin resistance induced by adrenomedullin mediates obesity-associated diabetes. Science 2025, 387, 674–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dai, H.B.; Wang, F.Z.; Kang, Y.; Sun, J.; Zhou, H.; Gao, Q.; Li, Z.Z.; Qian, P.; Zhu, G.Q.; Zhou, Y.B. Adrenomedullin Attenuates Inflammation in White Adipose Tissue of Obese Rats Through Receptor-Mediated PKA Pathway. Obesity 2021, 29, 86–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chauhan, M.; Ross, G.R.; Yallampalli, U.; Yallampalli, C. Adrenomedullin-2, a Novel Calcitonin/Calcitonin-Gene-Related Peptide Family Peptide, Relaxes Rat Mesenteric Artery: Influence of Pregnancy. Endocrinology 2007, 148, 1727–1735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, S.Y.; Xu, M.J.; Wang, X. Adrenomedullin 2/intermedin: A putative drug candidate for treatment of cardiometabolic diseases. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2018, 175, 1230–1240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, Y.; Zhang, S.-Y.; Liang, X.; Zhang, H.; Xu, Z.; Liu, B.; Xu, M.-J.; Jiang, C.; Shang, J.; Wang, X. Adrenomedullin 2 Enhances Beiging in White Adipose Tissue Directly in an Adipocyte-autonomous Manner and Indirectly through Activation of M2 Macrophages. J. Biol. Chem. 2016, 291, 23390–23402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weidemüller, P.; Kholmatov, M.; Petsalaki, E.; Zaugg, J.B. Transcription factors: Bridge between cell signaling and gene regulation. Proteomics 2021, 21, 2000034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, T.I.; Young, R.A. Transcriptional regulation and its misregulation in disease. Cell 2013, 152, 1237–1251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, X.; Wang, J.; Li, K.; Lv, B.; Hou, B.; Ding, Z. Protein post-translational modifications in auxin signaling. J. Genet. Genom. 2024, 51, 279–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardie, D.G.; Ross, F.A.; Hawley, S.A. AMPK: A nutrient and energy sensor that maintains energy homeostasis. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2012, 13, 251–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spriggs, K.A.; Bushell, M.; Willis, A.E. Translational Regulation of Gene Expression during Conditions of Cell Stress. Mol. Cell 2010, 40, 228–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalla Venezia, N.; Vincent, A.; Marcel, V.; Catez, F.; Diaz, J.J. Emerging Role of Eukaryote Ribosomes in Translational Control. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 1226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greber, B.J.; Ban, N. Structure and Function of the Mitochondrial Ribosome. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2016, 85, 103–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poitevin, F.; Kushner, A.; Li, X.; Dao Duc, K. Structural Heterogeneities of the Ribosome: New Frontiers and Opportunities for Cryo-EM. Molecules 2020, 25, 4262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, T.D.; Rousseau, A. Translation regulation in response to stress. Febs J. 2024, 291, 5102–5122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uematsu, S.; Qian, S.-B. Interpreting ribosome dynamics during mRNA translation. J. Biol. Chem. 2025, 301, 110469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Darnell, A.M.; Subramaniam, A.R.; O’Shea, E.K. Translational Control through Differential Ribosome Pausing during Amino Acid Limitation in Mammalian Cells. Mol. Cell 2018, 71, 229–243.e11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Snieckute, G.; Genzor, A.V.; Vind, A.C.; Ryder, L.; Stoneley, M.; Chamois, S.; Dreos, R.; Nordgaard, C.; Sass, F.; Blasius, M.; et al. Ribosome stalling is a signal for metabolic regulation by the ribotoxic stress response. Cell Metab. 2022, 34, 2036–2046.e8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vind, A.C.; Genzor, A.V.; Bekker-Jensen, S. Ribosomal stress-surveillance: Three pathways is a magic number. Nucleic Acids Res. 2020, 48, 10648–10661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.C.-C.; Peterson, A.; Zinshteyn, B.; Regot, S.; Green, R. Ribosome Collisions Trigger General Stress Responses to Regulate Cell Fate. Cell 2020, 182, 404–416.e14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Youn, D.; Kim, B.; Jeong, D.; Lee, J.Y.; Kim, S.; Sumberzul, D.; Ginting, R.P.; Lee, M.-W.; Song, J.H.; Park, Y.S.; et al. Cross-talks between Metabolic and Translational Controls during Beige Adipocyte Differentiation. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 3373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rathore, A.; Chu, Q.; Tan, D.; Martinez, T.F.; Donaldson, C.J.; Diedrich, J.K.; Yates, J.R., 3rd; Saghatelian, A. MIEF1 Microprotein Regulates Mitochondrial Translation. Biochemistry 2018, 57, 5564–5575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sareen Gropper, J.S.; Timothy, C. Advanced Nutrition and Human Metabolism; International Student Edition; Thomson Wadsworth: Belmont, CA, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Papakonstantinou, E.; Oikonomou, C.; Nychas, G.; Dimitriadis, G.D. Effects of Diet, Lifestyle, Chrononutrition and Alternative Dietary Interventions on Postprandial Glycemia and Insulin Resistance. Nutrients 2022, 14, 823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wachsmuth, H.R.; Weninger, S.N.; Duca, F.A. Role of the gut-brain axis in energy and glucose metabolism. Exp. Mol. Med. 2022, 54, 377–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garcia, D.; Shaw, R.J. AMPK: Mechanisms of Cellular Energy Sensing and Restoration of Metabolic Balance. Mol. Cell 2017, 66, 789–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saxton, R.A.; Sabatini, D.M. mTOR Signaling in Growth, Metabolism, and Disease. Cell 2017, 168, 960–976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehrke, M.; Lazar, M.A. The many faces of PPARgamma. Cell 2005, 123, 993–999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.; Katerelos, M.; Gleich, K.; Galic, S.; Kemp, B.E.; Mount, P.F.; Power, D.A. Phosphorylation of Acetyl-CoA Carboxylase by AMPK Reduces Renal Fibrosis and Is Essential for the Anti-Fibrotic Effect of Metformin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2018, 29, 2326–2336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dagher, Z.; Ruderman, N.; Tornheim, K.; Ido, Y. Acute Regulation of Fatty Acid Oxidation and AMP-Activated Protein Kinase in Human Umbilical Vein Endothelial Cells. Circ. Res. 2001, 88, 1276–1282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramakrishnan, S.K.; Khuder, S.S.; Al-Share, Q.Y.; Russo, L.; Abdallah, S.L.; Patel, P.R.; Heinrich, G.; Muturi, H.T.; Mopidevi, B.R.; Oyarce, A.M.; et al. PPARα (Peroxisome Proliferator-activated Receptor α) Activation Reduces Hepatic CEACAM1 Protein Expression to Regulate Fatty Acid Oxidation during Fasting-refeeding Transition. J. Biol. Chem. 2016, 291, 8121–8129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kersten, S.; Seydoux, J.; Peters, J.M.; Gonzalez, F.J.; Desvergne, B.; Wahli, W. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor alpha mediates the adaptive response to fasting. J. Clin. Investig. 1999, 103, 1489–1498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.X.; Lee, C.H.; Tiep, S.; Yu, R.T.; Ham, J.; Kang, H.; Evans, R.M. Peroxisome-proliferator-activated receptor delta activates fat metabolism to prevent obesity. Cell 2003, 113, 159–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bougarne, N.; Weyers, B.; Desmet, S.J.; Deckers, J.; Ray, D.W.; Staels, B.; De Bosscher, K. Molecular Actions of PPARα in Lipid Metabolism and Inflammation. Endocr. Rev. 2018, 39, 760–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ratman, D.; Mylka, V.; Bougarne, N.; Pawlak, M.; Caron, S.; Hennuyer, N.; Paumelle, R.; De Cauwer, L.; Thommis, J.; Rider, M.H.; et al. Chromatin recruitment of activated AMPK drives fasting response genes co-controlled by GR and PPARα. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016, 44, 10539–10553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamradt, M.L.; Makarewich, C.A. Mitochondrial microproteins: Critical regulators of protein import, energy production, stress response pathways, and programmed cell death. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 2023, 325, C807–C816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, M.; Fan, W.; Zhong, D.; Dai, X.; Wang, Q.; Liu, W.; Li, S. Ribosome Pausing Negatively Regulates Protein Translation in Maize Seedlings during Dark-to-Light Transitions. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 7985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Couso, J.P.; Patraquim, P. Classification and function of small open reading frames. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2017, 18, 575–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sivitz, W.I.; Yorek, M.A. Mitochondrial dysfunction in diabetes: From molecular mechanisms to functional significance and therapeutic opportunities. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2010, 12, 537–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sergiev, P.; Averina, O.; Golubeva, J.; Vyssokikh, M.; Dontsova, O. Mitoregulin, a tiny protein at the crossroads of mitochondrial functioning, stress, and disease. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2025, 13, 1545359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makarewich, C.A. The hidden world of membrane microproteins. Exp. Cell Res. 2020, 388, 111853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, N.; Li, F.; Zhang, M.; Zhou, H.; Chen, Z.; Ma, X.; Yang, L.; Wu, X.; Zhong, J.; Xiao, F.; et al. An Upstream Open Reading Frame in Phosphatase and Tensin Homolog Encodes a Circuit Breaker of Lactate Metabolism. Cell Metab. 2021, 33, 128–144.e9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Puig, M.; Shubow, S. Immunogenicity of therapeutic peptide products: Bridging the gaps regarding the role of product-related risk factors. Front. Immunol. 2025, 16, 1608401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, W.; Jiang, W.; Chen, Z.; Huang, Y.; Mao, J.; Zheng, W.; Hu, Y.; Shi, J. Advance in peptide-based drug development: Delivery platforms, therapeutics and vaccines. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2025, 10, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Govaere, O.; Hasoon, M.; Alexander, L.; Cockell, S.; Tiniakos, D.; Ekstedt, M.; Schattenberg, J.M.; Boursier, J.; Bugianesi, E.; Ratziu, V.; et al. A proteo-transcriptomic map of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease signatures. Nat. Metab. 2023, 5, 572–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, T.-t.; Huang, Y.; Li, Y.; Dai, X.-l.; He, Y.-h.; Ding, J.-c.; Ran, T.; Shi, Y.; Yuan, Q.; Li, W.-j.; et al. MAVI1, an endoplasmic reticulum–localized microprotein, suppresses antiviral innate immune response by targeting MAVS on mitochondrion. Sci. Adv. 2023, 9, eadg7053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chothani, S.; Ho, L.; Schafer, S.; Rackham, O. Discovering microproteins: Making the most of ribosome profiling data. RNA Biol. 2023, 20, 943–954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fan, Y.H.; Zhang, S.; Wang, Y.; Wang, H.; Li, H.; Bai, L. Inter-organ metabolic interaction networks in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Front. Endocrinol. 2024, 15, 1494560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pickart, C.M. Mechanisms Underlying Ubiquitination. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2001, 70, 503–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, L.; Liu, S.; Zhao, Q.; Liu, X.; Zhang, Q.; Liu, M.; Zhao, W. The role of ubiquitination and deubiquitination in the pathogenesis of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Front. Immunol. 2025, 16, 1535362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, N.; Shabek, N. Ubiquitin Ligases: Structure, Function, and Regulation. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2017, 86, 129–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komander, D.; Rape, M. The Ubiquitin Code. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2012, 81, 203–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Xiao, J.; Jiang, M.; Phillips, C.J.C.; Shi, B. Thermogenesis and Energy Metabolism in Brown Adipose Tissue in Animals Experiencing Cold Stress. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 3233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Osuna-Prieto, F.J.; Martinez-Tellez, B.; Sanchez-Delgado, G.; Aguilera, C.M.; Lozano-Sánchez, J.; Arráez-Román, D.; Segura-Carretero, A.; Ruiz, J.R. Activation of Human Brown Adipose Tissue by Capsinoids, Catechins, Ephedrine, and Other Dietary Components: A Systematic Review. Adv. Nutr. 2019, 10, 291–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saito, M.; Matsushita, M.; Yoneshiro, T.; Okamatsu-Ogura, Y. Brown Adipose Tissue, Diet-Induced Thermogenesis, and Thermogenic Food Ingredients: From Mice to Men. Front. Endocrinol. 2020, 11, 222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, J.; Khedr, M.A.; Pan, M.; Ferreira, C.R.; Chen, J.; Snyder, M.M.; Ajuwon, K.M.; Yue, F.; Kuang, S. Ablation of FAM210A in Brown Adipocytes of Mice Exacerbates High-Fat Diet-Induced Metabolic Dysfunction. Diabetes 2025, 74, 282–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zárate, S.C.; Traetta, M.E.; Codagnone, M.G.; Seilicovich, A.; Reinés, A.G. Humanin, a Mitochondrial-Derived Peptide Released by Astrocytes, Prevents Synapse Loss in Hippocampal Neurons. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2019, 11, 123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, Z.; Goetzman, E.; Muzumdar, R.H. Cardio-protective role of Humanin in myocardial ischemia-reperfusion. Biochimica Biophys. Acta (BBA)—Gen. Subj. 2022, 1866, 130066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, H.; Liu, Y.; Men, H.; Zheng, Y. Protective Mechanism of Humanin Against Oxidative Stress in Aging-Related Cardiovascular Diseases. Front. Endocrinol. 2021, 12, 683151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.; Huang, X.; Dou, L.; Yan, M.; Shen, T.; Tang, W.; Li, J. Aging and aging-related diseases: From molecular mechanisms to interventions and treatments. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2022, 7, 391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butler, A.A.; Zhang, J.; Price, C.A.; Stevens, J.R.; Graham, J.L.; Stanhope, K.L.; King, S.; Krauss, R.M.; Bremer, A.A.; Havel, P.J. Low plasma adropin concentrations increase risks of weight gain and metabolic dysregulation in response to a high-sugar diet in male nonhuman primates. J. Biol. Chem. 2019, 294, 9706–9719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miller, B.; Kim, S.-J.; Kumagai, H.; Mehta, H.H.; Xiang, W.; Liu, J.; Yen, K.; Cohen, P. Peptides derived from small mitochondrial open reading frames: Genomic, biological, and therapeutic implications. Exp. Cell Res. 2020, 393, 112056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abulmeaty, M.M.A.; Almajwal, A.M.; Alnumair, K.S.; Razak, S.; Hasan, M.M.; Fawzy, A.; Farraj, A.I.; Abudawood, M.; Aljuraiban, G.S. Effect of Long-Term Continuous Light Exposure and Western Diet on Adropin Expression, Lipid Metabolism, and Energy Homeostasis in Rats. Biology 2021, 10, 413, Erratum in Biology 2023, 12, 209. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology12020209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tripathi, S.; Maurya, S.; Singh, A. Adropin mitigates reproductive and metabolic dysfunctions in streptozotocin induced hyperglycemic mice. J. Endocrinol. 2025, 266, e250072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mittal, N.; Ataman, M.; Tintignac, L.; Ham, D.J.; Jörin, L.; Schmidt, A.; Sinnreich, M.; Ruegg, M.A.; Zavolan, M. Calorie restriction and rapamycin distinctly restore non-canonical ORF translation in the muscles of aging mice. Npj Regen. Med. 2024, 9, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stevens, J.R.; Girardet, C.; Zhou, M.; Gamie, F.; Aggarwal, G.; McMillan, R.P.; Hulver, M.W.; Martinez, L.O.; van der Brug, M.; Vellas, B.; et al. Adropin expression reflects circadian, lipoprotein, and mitochondrial processes in human tissues. Mol. Metab. 2025, 99, 102196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofer, S.J.; Carmona-Gutierrez, D.; Mueller, M.I.; Madeo, F. The ups and downs of caloric restriction and fasting: From molecular effects to clinical application. EMBO Mol. Med. 2022, 14, e14418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butler, A.A.; Havel, P.J. Adropin: A cardio-metabolic hormone in the periphery, a neurohormone in the brain? Peptides 2025, 187, 171391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thapa, D.; Xie, B.; Manning, J.R.; Zhang, M.; Stoner, M.W.; Huckestein, B.R.; Edmunds, L.R.; Zhang, X.; Dedousis, N.L.; O’Doherty, R.M.; et al. Adropin reduces blood glucose levels in mice by limiting hepatic glucose production. Physiol. Rep. 2019, 7, e14043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Ding, N.; Chen, C.; Gu, S.; Liu, J.; Wang, Y.; Lin, L.; Zheng, Y.; Li, Y. Adropin: A key player in immune cell homeostasis and regulation of inflammation in several diseases. Front. Immunol. 2025, 16, 1482308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Chen, Q.; Lin, X.; Chen, M.; Liu, Q. A Review of Adropin as the Medium of Dialogue between Energy Regulation and Immune Regulation. Oxidative Med. Cell. Longev. 2020, 2020, 3947806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senís, E.; Esgleas, M.; Najas, S.; Jiménez-Sábado, V.; Bertani, C.; Giménez-Alejandre, M.; Escriche, A.; Ruiz-Orera, J.; Hergueta-Redondo, M.; Jiménez, M.; et al. TUNAR lncRNA Encodes a Microprotein that Regulates Neural Differentiation and Neurite Formation by Modulating Calcium Dynamics. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2021, 9, 747667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.N.; Wang, W.; Yang, N.; Huang, X.M.; Liu, C.F. Regulation of Glucose and Lipid Metabolism by Long Non-coding RNAs: Facts and Research Progress. Front. Endocrinol. 2020, 11, 457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brar, G.A.; Weissman, J.S. Ribosome profiling reveals the what, when, where, and how of protein synthesis. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2015, 16, 651–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leong, A.Z.-X.; Lee, P.Y.; Mohtar, M.A.; Syafruddin, S.E.; Pung, Y.-F.; Low, T.Y. Short open reading frames (sORFs) and microproteins: An update on their identification and validation measures. J. Biomed. Sci. 2022, 29, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, H.; Wang, S.; Wang, Y.; Ni, X.; Yang, Z.; Hu, X.; Sen, Y. LncCat: An ORF attention model to identify LncRNA based on ensemble learning strategy and fused sequence information. Comput. Struct. Biotechnol. J. 2023, 21, 1433–1447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, L.; Liu, H.; Zhang, L.; Meng, J. lncRScan-SVM: A Tool for Predicting Long Non-Coding RNAs Using Support Vector Machine. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0139654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Park, H.J.; Dasari, S.; Wang, S.; Kocher, J.P.; Li, W. CPAT: Coding-Potential Assessment Tool using an alignment-free logistic regression model. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013, 41, e74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, J.; Wang, R.; Shang, F.; Ma, R.; Rong, Y.; Zhang, Y. Functional Micropeptides Encoded by Long Non-Coding RNAs: A Comprehensive Review. Front. Mol. Biosci. 2022, 9, 817517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrews, S.J.; Rothnagel, J.A. Emerging evidence for functional peptides encoded by short open reading frames. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2014, 15, 193–204, Erratum in Nat. Rev. Genet. 2014, 15, 286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trivedi, R.; Nagarajaram, H.A. Intrinsically Disordered Proteins: An Overview. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 14050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maiti, S.; Singh, A.; Maji, T.; Saibo, N.V.; De, S. Experimental methods to study the structure and dynamics of intrinsically disordered regions in proteins. Curr. Res. Struct. Biol. 2024, 7, 100138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yandell, M.; Ence, D. A beginner’s guide to eukaryotic genome annotation. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2012, 13, 329–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prensner, J.R.; Abelin, J.G.; Kok, L.W.; Clauser, K.R.; Mudge, J.M.; Ruiz-Orera, J.; Bassani-Sternberg, M.; Moritz, R.L.; Deutsch, E.W.; van Heesch, S. What Can Ribo-Seq, Immunopeptidomics, and Proteomics Tell Us About the Noncanonical Proteome? Mol. Cell. Proteom. 2023, 22, 100631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Zhou, H.; Chen, X.; Zheng, Y.; Kang, Q.; Hao, D.; Zhang, L.; Song, T.; Luo, H.; Hao, Y.; et al. SmProt: A Reliable Repository with Comprehensive Annotation of Small Proteins Identified from Ribosome Profiling. Genom. Proteom. Bioinform. 2021, 19, 602–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valdivia-Francia, F.; Sendoel, A. No country for old methods: New tools for studying microproteins. iScience 2024, 27, 108972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pruitt, K.D.; Brown, G.R.; Hiatt, S.M.; Thibaud-Nissen, F.; Astashyn, A.; Ermolaeva, O.; Farrell, C.M.; Hart, J.; Landrum, M.J.; McGarvey, K.M.; et al. RefSeq: An update on mammalian reference sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014, 42, D756–D763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olexiouk, V.; Van Criekinge, W.; Menschaert, G. An update on sORFs.org: A repository of small ORFs identified by ribosome profiling. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018, 46, D497–D502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunet, M.A.; Brunelle, M.; Lucier, J.-F.; Delcourt, V.; Levesque, M.; Grenier, F.; Samandi, S.; Leblanc, S.; Aguilar, J.-D.; Dufour, P.; et al. OpenProt: A more comprehensive guide to explore eukaryotic coding potential and proteomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018, 47, D403–D410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, M.; Xie, Y.; Wang, L.; Jungreis, I.; Ou, T.; Kellis, M.; Wang, J.; Zhu, Y. Proteogenomics-enabled discovery of novel small open reading frame (sORF)-encoded polypeptides in human and mouse tissues. Nucleic Acids Res. 2025, 53, gkaf687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilkinson, M.D.; Dumontier, M.; Aalbersberg, I.J.; Appleton, G.; Axton, M.; Baak, A.; Blomberg, N.; Boiten, J.-W.; da Silva Santos, L.B.; Bourne, P.E.; et al. The FAIR Guiding Principles for scientific data management and stewardship. Sci. Data 2016, 3, 160018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mudge, J.M.; Harrow, J. The state of play in higher eukaryote gene annotation. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2016, 17, 758–772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmadian, M.; Suh, J.M.; Hah, N.; Liddle, C.; Atkins, A.R.; Downes, M.; Evans, R.M. PPARγ signaling and metabolism: The good, the bad and the future. Nat Med. 2013, 19, 557–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vrbnjak, K.; Sewduth, R.N. Multi-Omic Approaches in Cancer-Related Micropeptide Identification. Proteomes 2024, 12, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Microprotein | Genomic Origin | Primary Nutrient/ Stress Cue | Localization | Major Metabolic or Signaling Role | Physiological Context | Key References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SMIM26 | Nuclear sORF [mitochondrial-targeted] | Serine deficiency; one-carbon metabolism | Mitochondria | Regulation of SFXN1/2; support of ND5 mitoribosomal translation; OXPHOS stabilization | Serine starvation, mitochondrial dysfunction | [22,45,72] |

| MTLN [Mitoregulin/MOXI] | LINC00116-encoded microprotein | FA oxidation state; mitochondrial lipid stress | Outer mitochondrial membrane | Modulation of FA β-oxidation; interaction with CPT1B/CYB5B; respiratory efficiency | Obesity; insulin resistance | [48,79,80] |

| Mitolamban [Mtlbn] | Nuclear-encoded microprotein [cardiac-enriched] | Mitochondrial respiratory stress | Inner mitochondrial membrane | Assembly/organization of Complex III and supercomplexes; redox balance | Cardiomyopathy; diabetes-related mitochondrial dysfunction | [81,82,83] |

| BRAWNIN | Nuclear sORF | Nutrient stress; AMPK activation | Inner mitochondrial membrane | Essential assembly factor for Complex III; supports OXPHOS | Mitochondrial dysfunction; metabolic stress | [49,84,85,86] |

| NEMEP | Nuclear-encoded microprotein | Growth-factor availability; glucose influx | Plasma membrane/endosomes | GLUT1/3 interaction; regulation of glucose uptake; glycolytic flux modulation | Embryogenesis; metabolic flexibility | [23,54] |

| MOTS-c | mtDNA-encoded [12S rRNA region] | Exercise; folate-cycle stress; glucose fluctuations | Cytosol → nucleus | AMPK activation; metabolic flexibility; stress adaptation | Obesity; type 2 diabetes | [24,56,87,88,89] |

| Humanin | mtDNA/NUMT | Oxidative stress | Cytosol, mitochondria | Anti-apoptotic and antioxidant signaling; mitochondrial protection | Aging; insulin resistance | [31,90,91,92,93,94] |

| Adropin | Nuclear-encoded secreted peptide [ENHO] | Feeding–fasting states; caloric restriction | Circulation | Substrate-use switching; lipid–glucose homeostasis | Dyslipidemia; NAFLD; insulin resistance | [95,96,97,98,99,100,101,102] |

| Neuronatin [Nnat] | Nuclear sORF [imprinted gene] | Glucose flux; ER Ca2+ handling | ER | Regulation of Ca2+-dependent insulin secretion; proinsulin processing | β-cell physiology; T2DM | [74,103] |

| BNLN | lncRNA-derived micropeptide | ER stress | ER | Ca2+ dynamics regulation; enhancement of GSIS | β-cell physiology | [51] |

| PIGBOS | Nuclear-encoded microprotein | ER–mitochondrial stress | Mitochondrial outer membrane [MOM] | Modulation of UPR; ER stress signaling | Metabolic stress | [58,104,105] |

| UFD1s | Nuclear-encoded [alternative splice-derived microprotein] | Metabolic stress; lipid overload | Cytosol | Modulates UFD1f/IPMK ubiquitination [K48/K63]; promotes autophagy and FA oxidation | NAFLD; NASH protection | [106] |

| MICT1 | Nuclear-encoded | Cold exposure | Mitochondria | Enhancement of BAT thermogenesis; amplification of β-adrenergic signaling | Obesity; energy expenditure | [50,107] |

| FAM237B [Gm8773 peptide] | Nuclear-encoded secreted microprotein | Feeding state; adiposity signals | Hypothalamic arcuate nucleus; circulation | Central orexigenic signaling; regulation of food intake | Obesity; brain–adipose axis | [25,108] |

| ADM/ADM2 | Nuclear-encoded peptide hormones | Circulating metabolic cues | Endocrine circulation | Regulation of insulin action; vascular perfusion; glucose delivery | Diabetes; metabolic syndrome | [109,110,111,112,113] |

| Category | Conventional Metabolic Regulators | SMIM26 |

|---|---|---|

| (Kinases/Transcription Factors) | (Microprotein) | |

| Target | Signal transduction/Transcriptional regulation | Direct regulation of ribosome/translation protein complexes |

| Level of Response | Transcription or post-translational signaling | Regulation at the translation level, directly influencing Complex I assembly |

| Nutrient Sensing | Typically mediated by AMPK, HIF-1-alpha, PPARs, etc. | Serine deficiency directly acts as a signal regulating SMIM26 expression |

| Mechanism | Indirect involves multiple transcriptional pathways | A novel regulatory axis via microprotein-mediated translational control |

| Level | Primary Sensor/Level | Typical Onset | Dominant Functional Role | Representative References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AMPK | Cellular energy charge; post-translational phosphorylation | Seconds–minutes | Acute metabolic triage: suppression of biosynthesis, stimulation of fatty acid oxidation, and enhanced glucose uptake | [18,133,136,137] |

| PPARs (α/γ/δ) | Lipid ligands; transcriptional regulation | Hours–days | Durable fuel selection and organ-level metabolic adaptation during fasting–feeding transitions | [19,78,135,138,139] |

| SMIM26 | Nutrient-responsive peptides; translational control | Minutes | Direct modulation of mitochondrial translation (ND5) and respiratory chain activity | [22,45,72,143] |

| MOTS-c | Stress-induced mitochondrial peptides; peptide–kinase–transcription axis | Minutes–hours | Coupling of mitochondrial stress signals to AMPK and PPAR programs, thereby integrating acute and chronic metabolic regulation | [24,56,87,88] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ko, S.-H.; Cho, B.; Shin, D. Microproteins in Metabolic Biology: Emerging Functions and Potential Roles as Nutrient-Linked Biomarkers. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 11883. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262411883

Ko S-H, Cho B, Shin D. Microproteins in Metabolic Biology: Emerging Functions and Potential Roles as Nutrient-Linked Biomarkers. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2025; 26(24):11883. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262411883

Chicago/Turabian StyleKo, Seong-Hee, BeLong Cho, and Dayeon Shin. 2025. "Microproteins in Metabolic Biology: Emerging Functions and Potential Roles as Nutrient-Linked Biomarkers" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 26, no. 24: 11883. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262411883

APA StyleKo, S.-H., Cho, B., & Shin, D. (2025). Microproteins in Metabolic Biology: Emerging Functions and Potential Roles as Nutrient-Linked Biomarkers. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 26(24), 11883. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262411883