Raman and Infrared Spectroscopy of Materials for Lithium-Ion Batteries

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Spectroscopy Background

2.1. Photon–Matter Interactions

2.2. Site Symmetry and Vibrational Modes

2.3. Vibration of Nanoparticles

2.4. Raman Single-Point and Mapping Measurements

2.4.1. Experimental In Situ Raman Setups

2.4.2. Optical Skin Depth

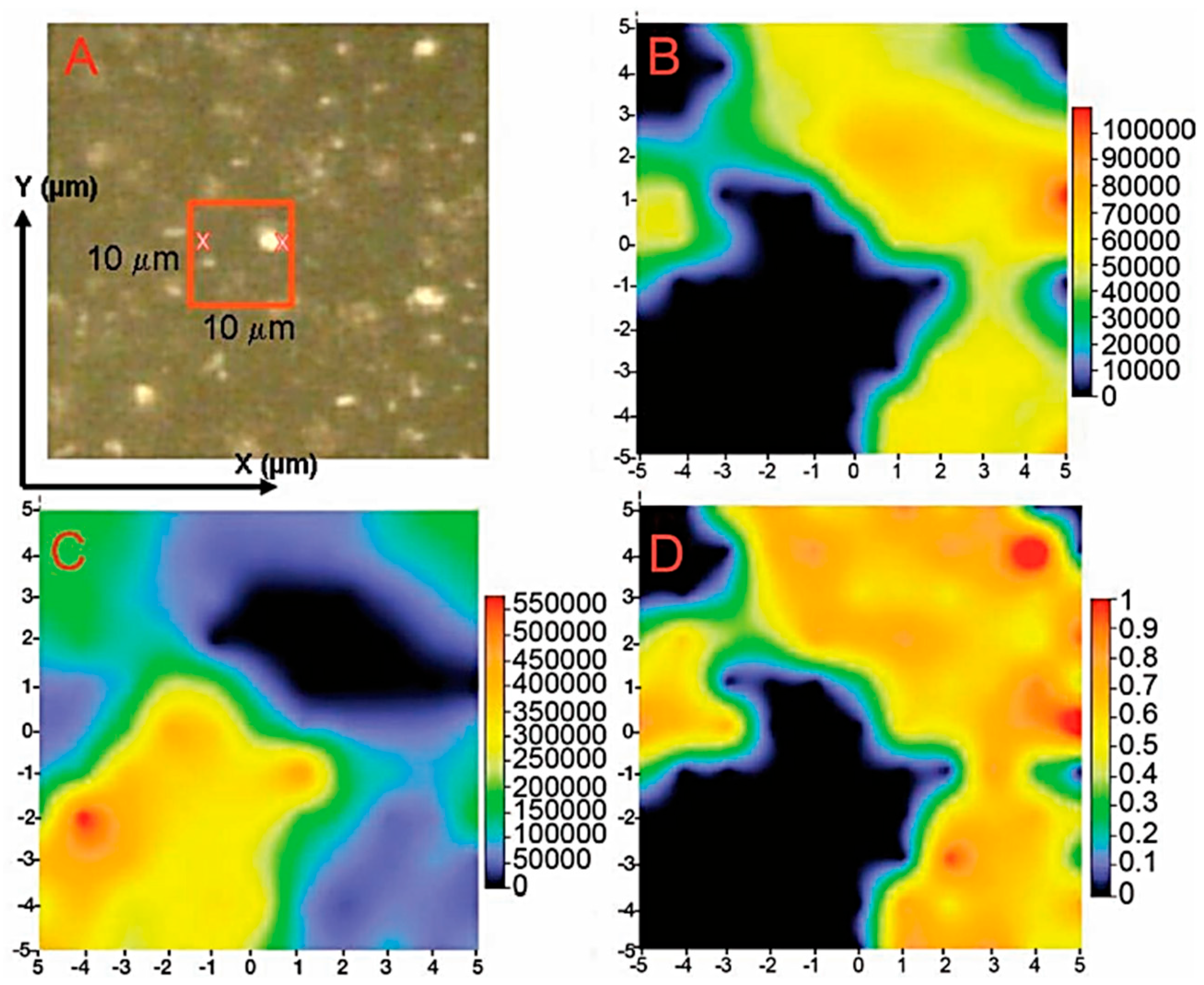

2.4.3. In Situ Raman Imaging

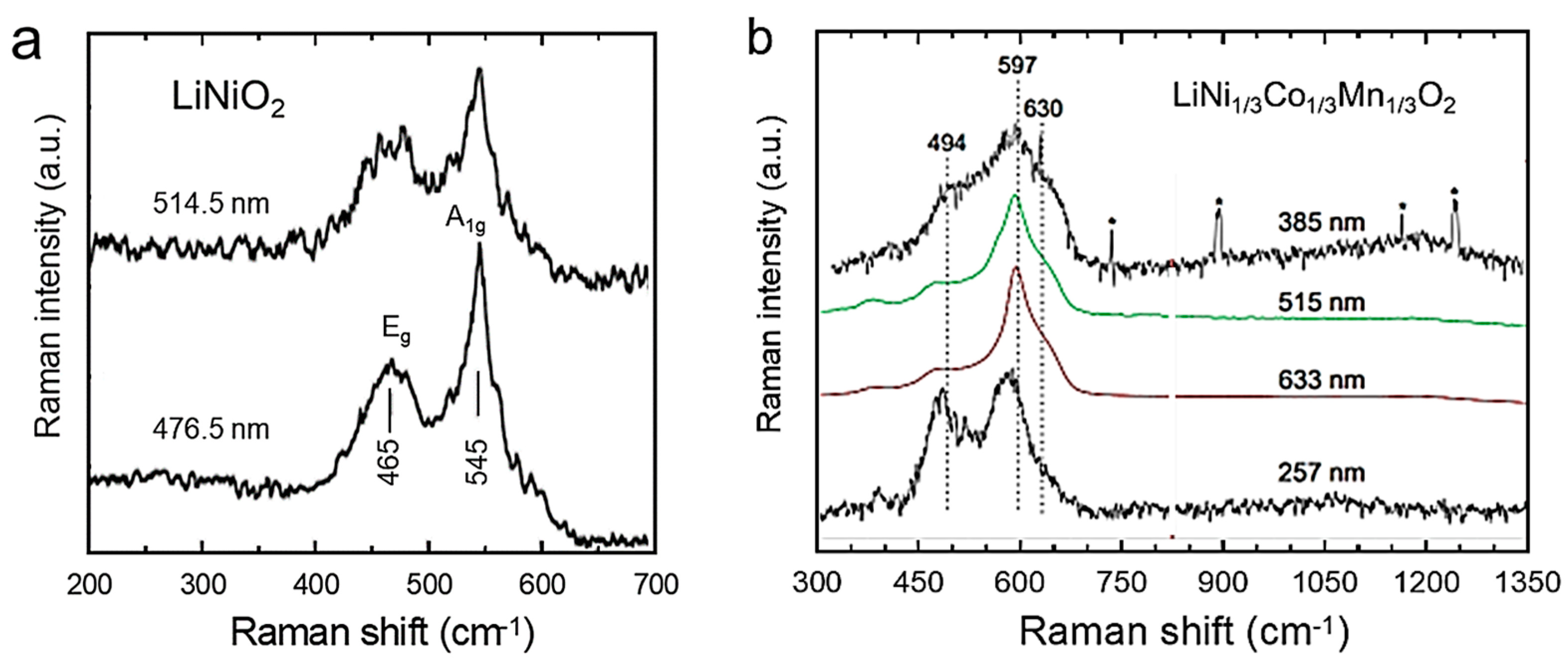

2.5. Resonance Raman Spectroscopy

3. Tools for Raman Analysis

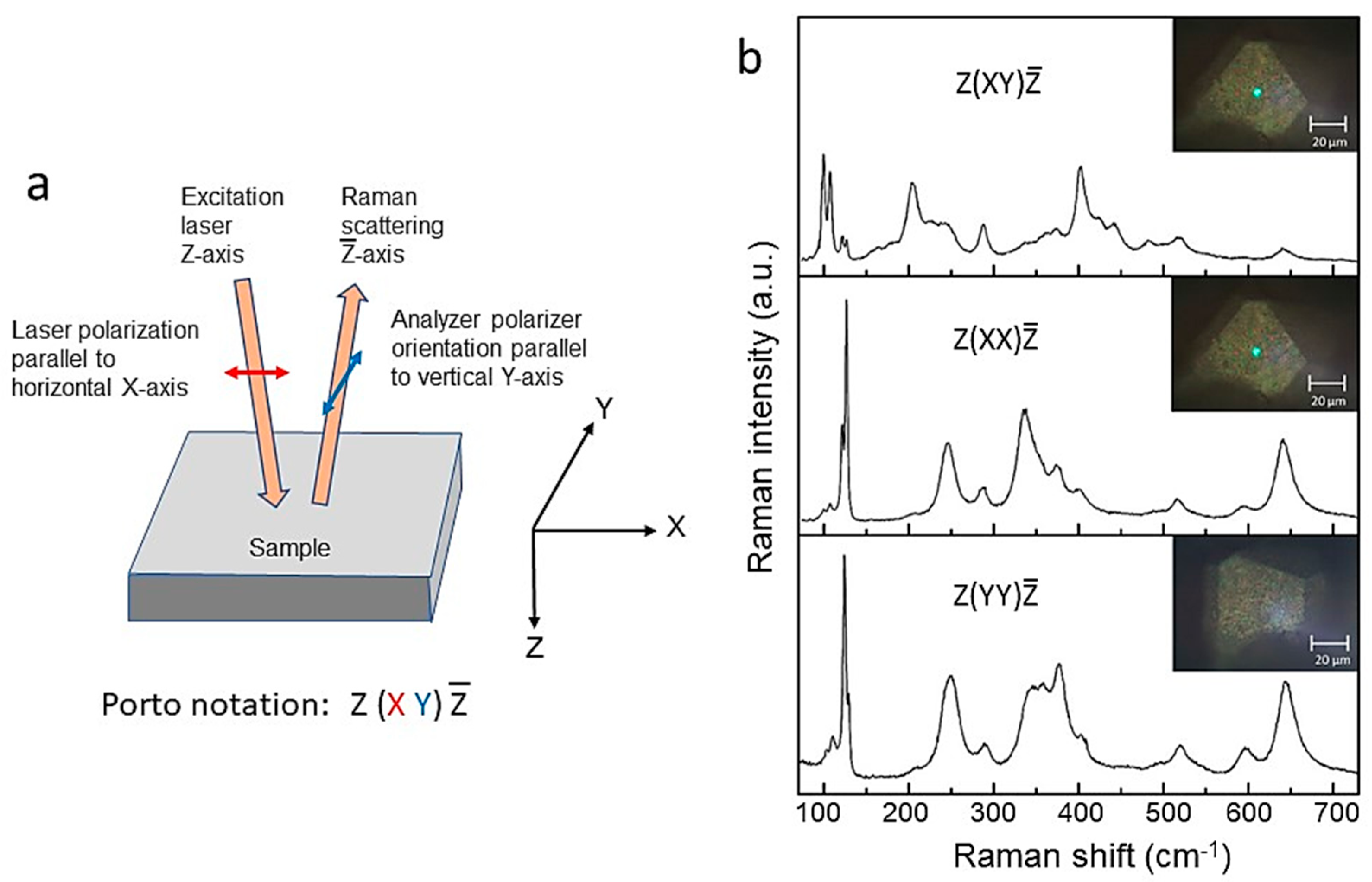

3.1. Polarization Analysis

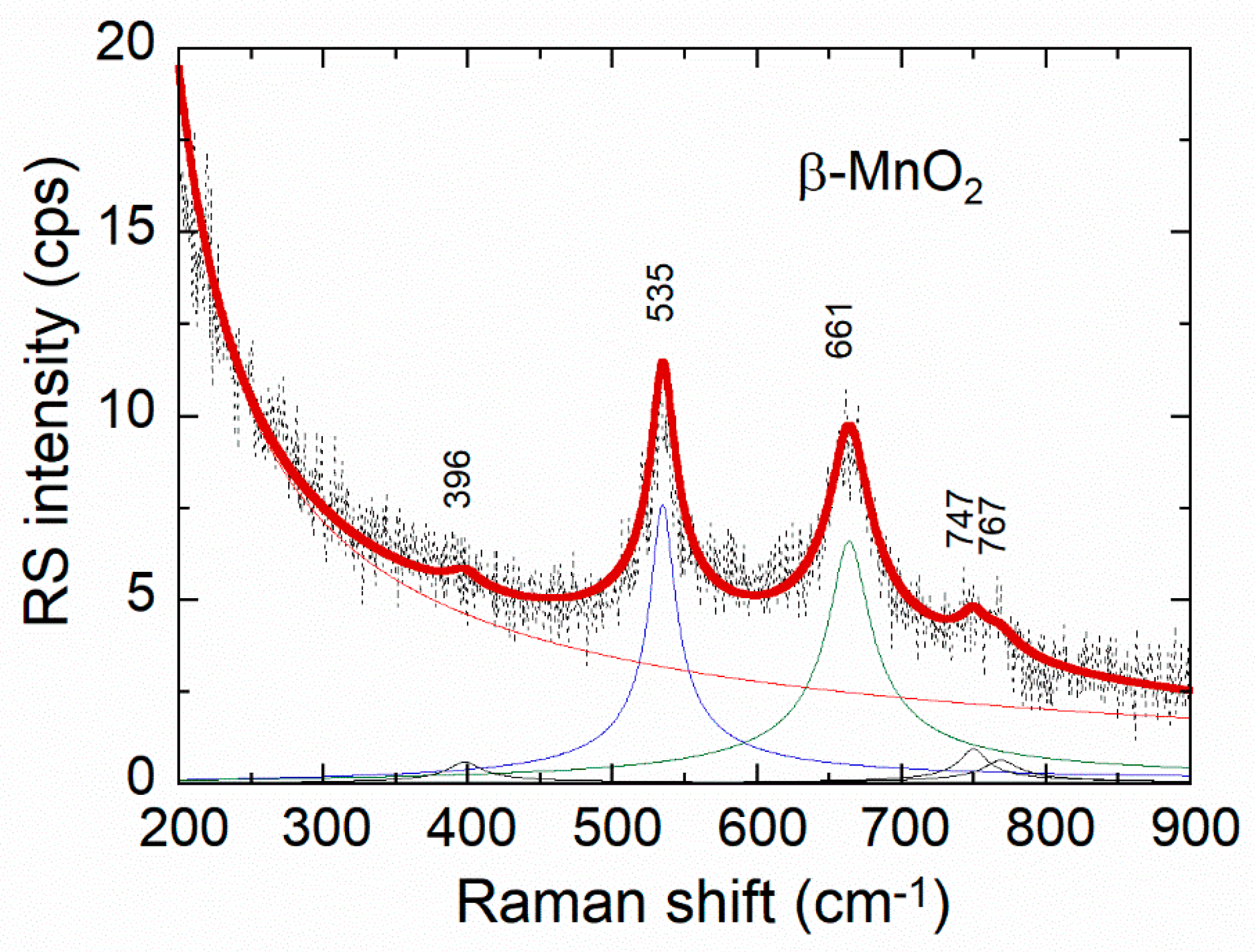

3.2. Curves Fitting

4. Raman and FTIR Analysis of Cathode Materials

4.1. Layered (Rock-Salt) Structure

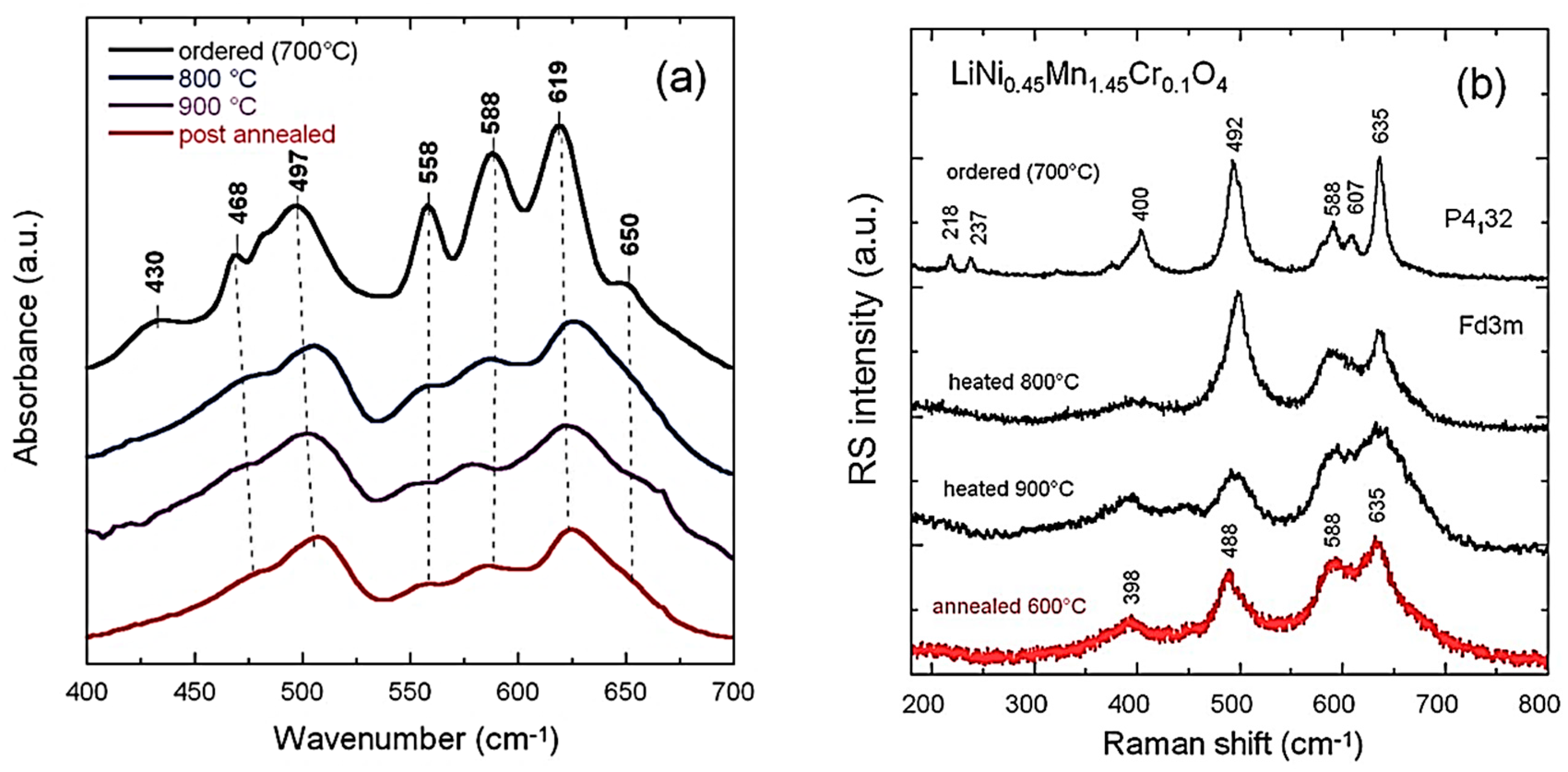

4.2. Spinel (Cubic) Structure

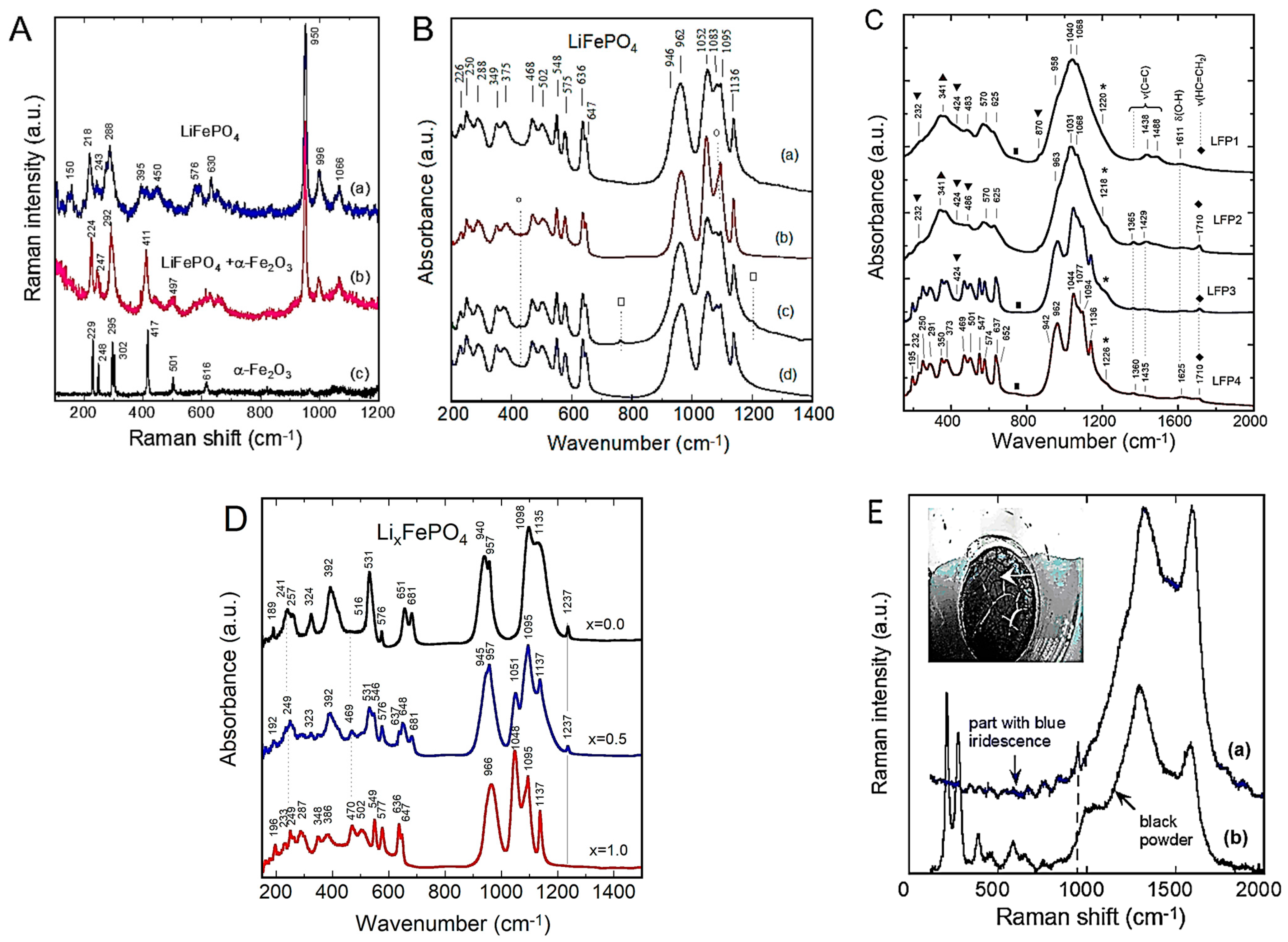

4.3. Phosphate (Olivine) Structure

5. Raman and FTIR Analysis of Anode Materials

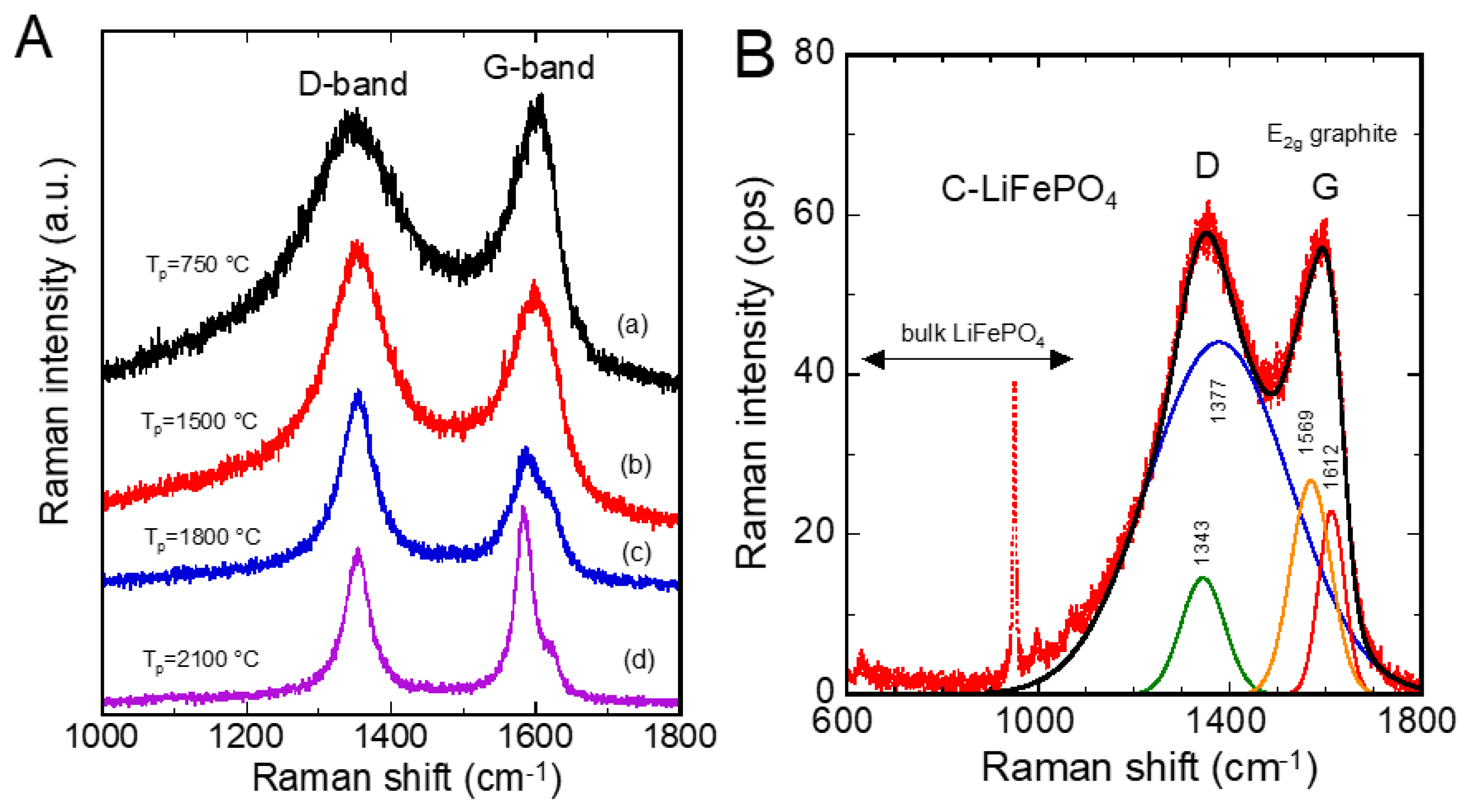

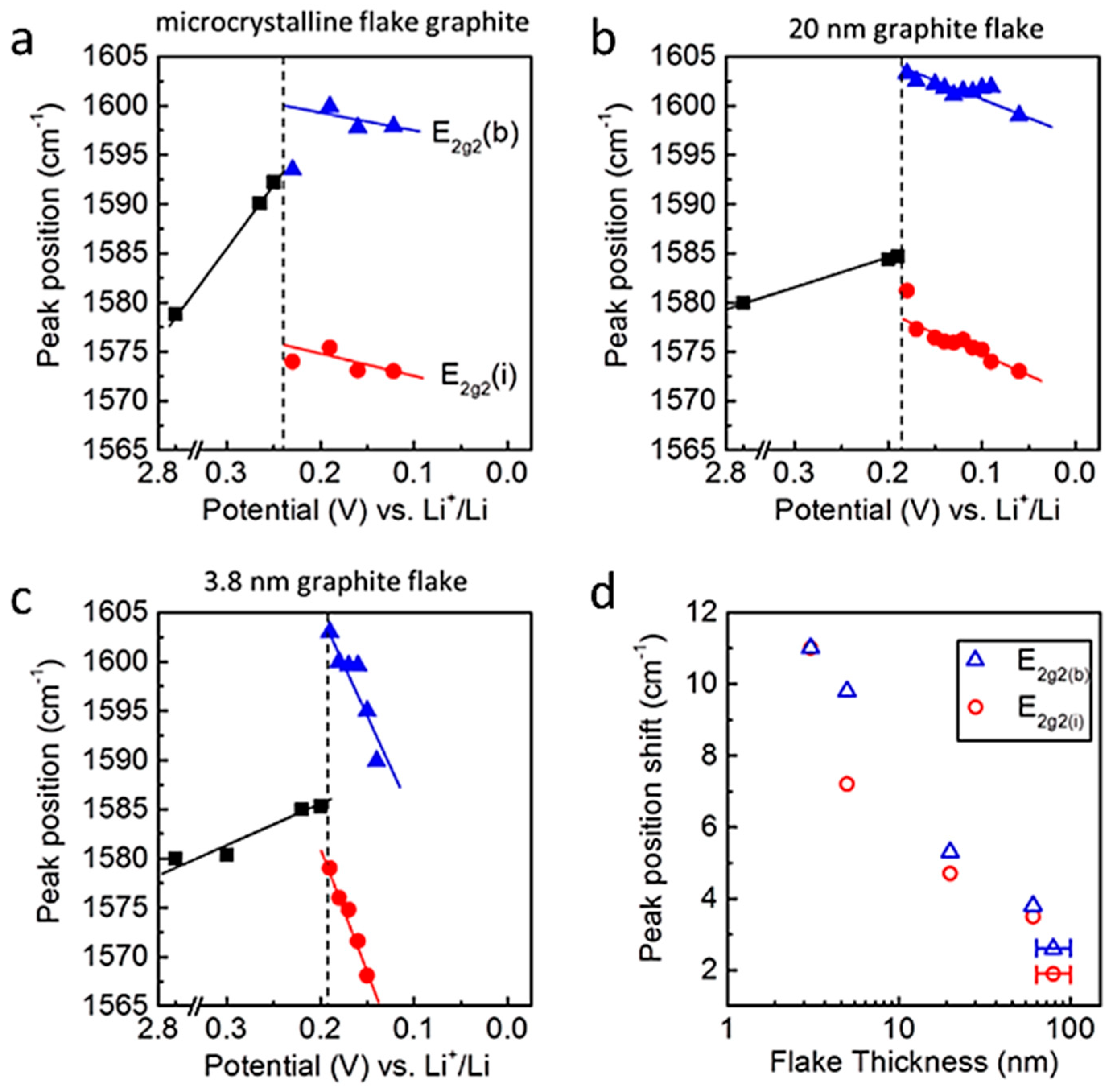

5.1. Nano-Carbon Anode

5.2. Nano-Silicon Anode

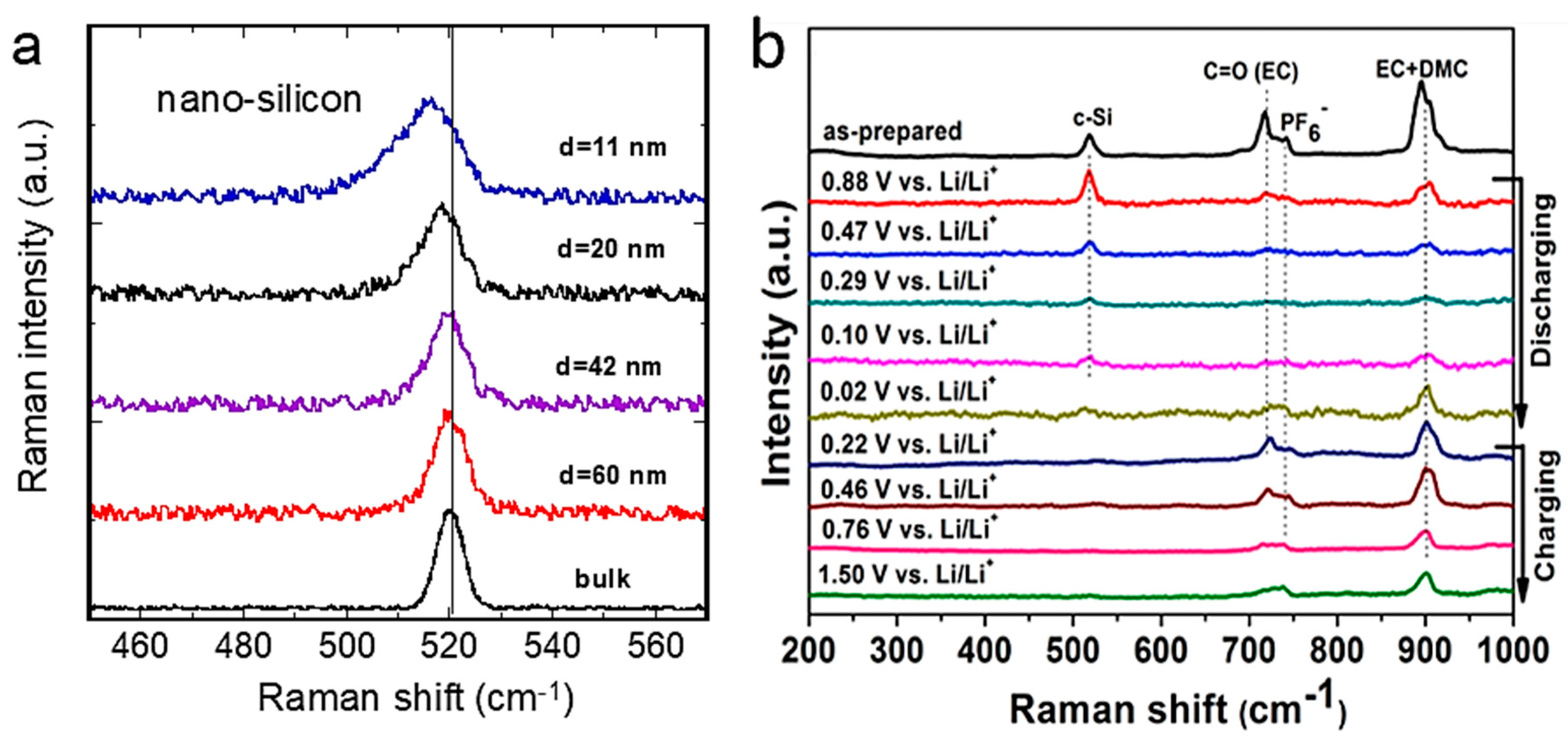

5.3. Titanate-Based Anodes

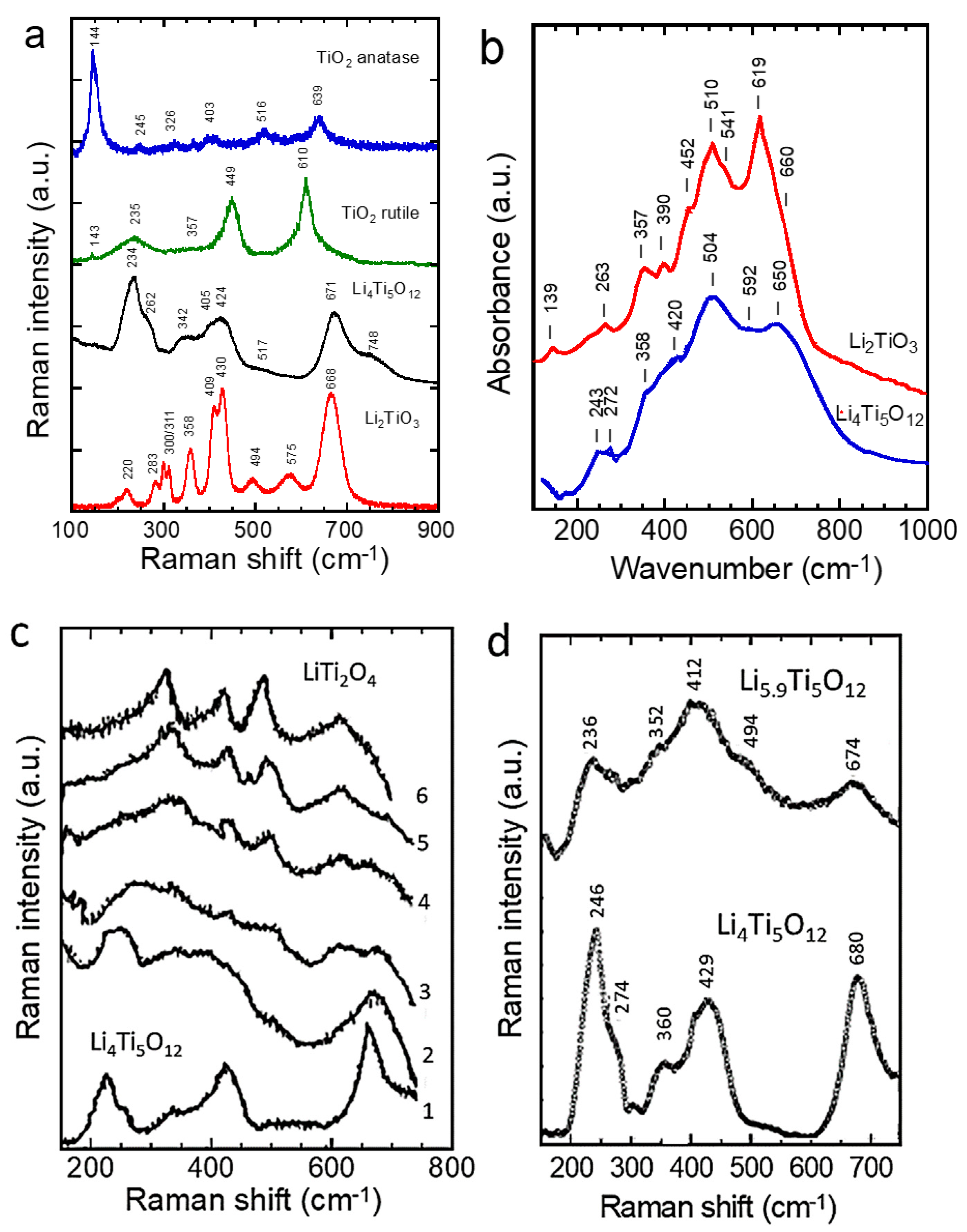

6. Raman and FTIR Analysis of Electrolytes

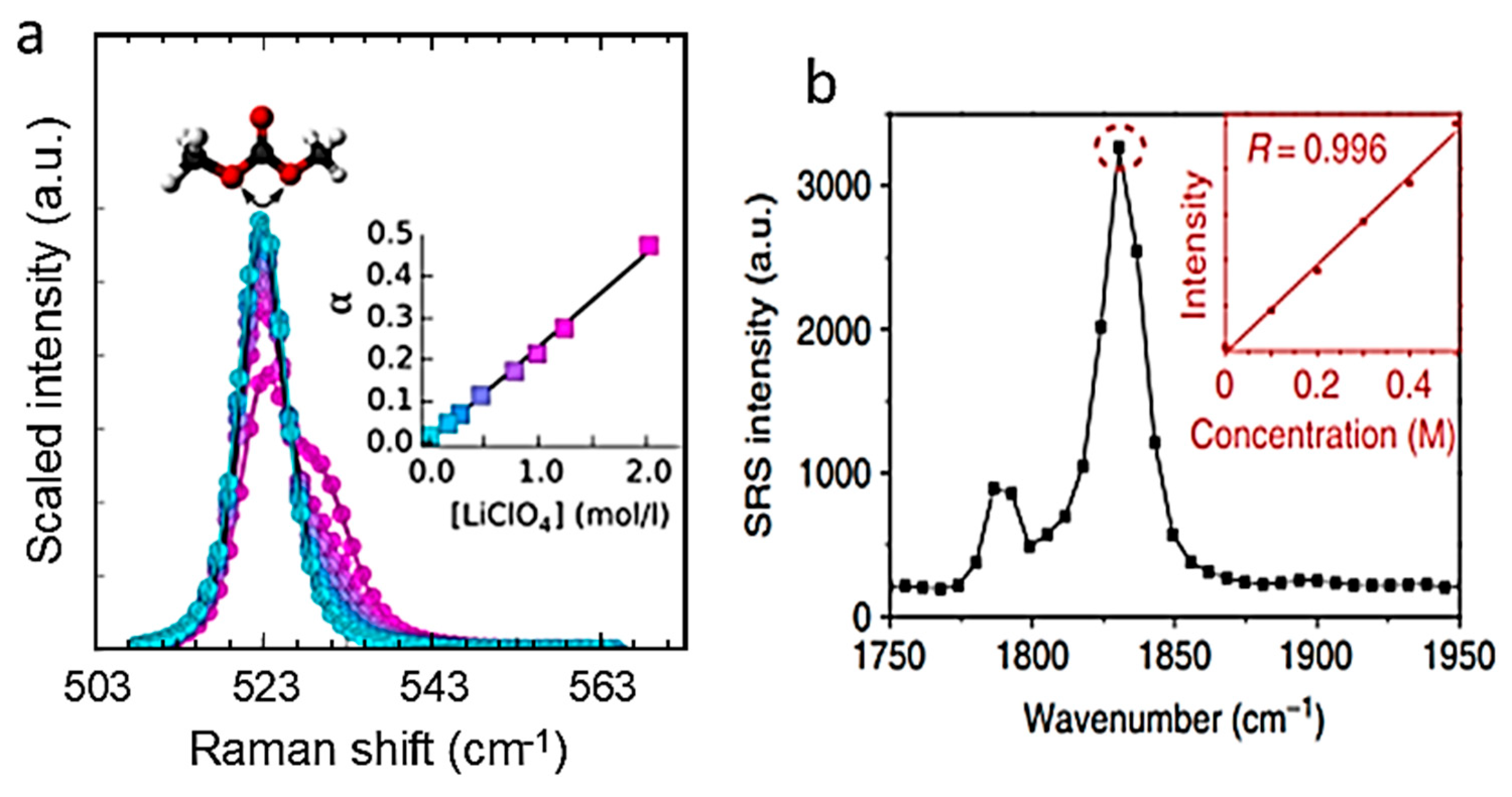

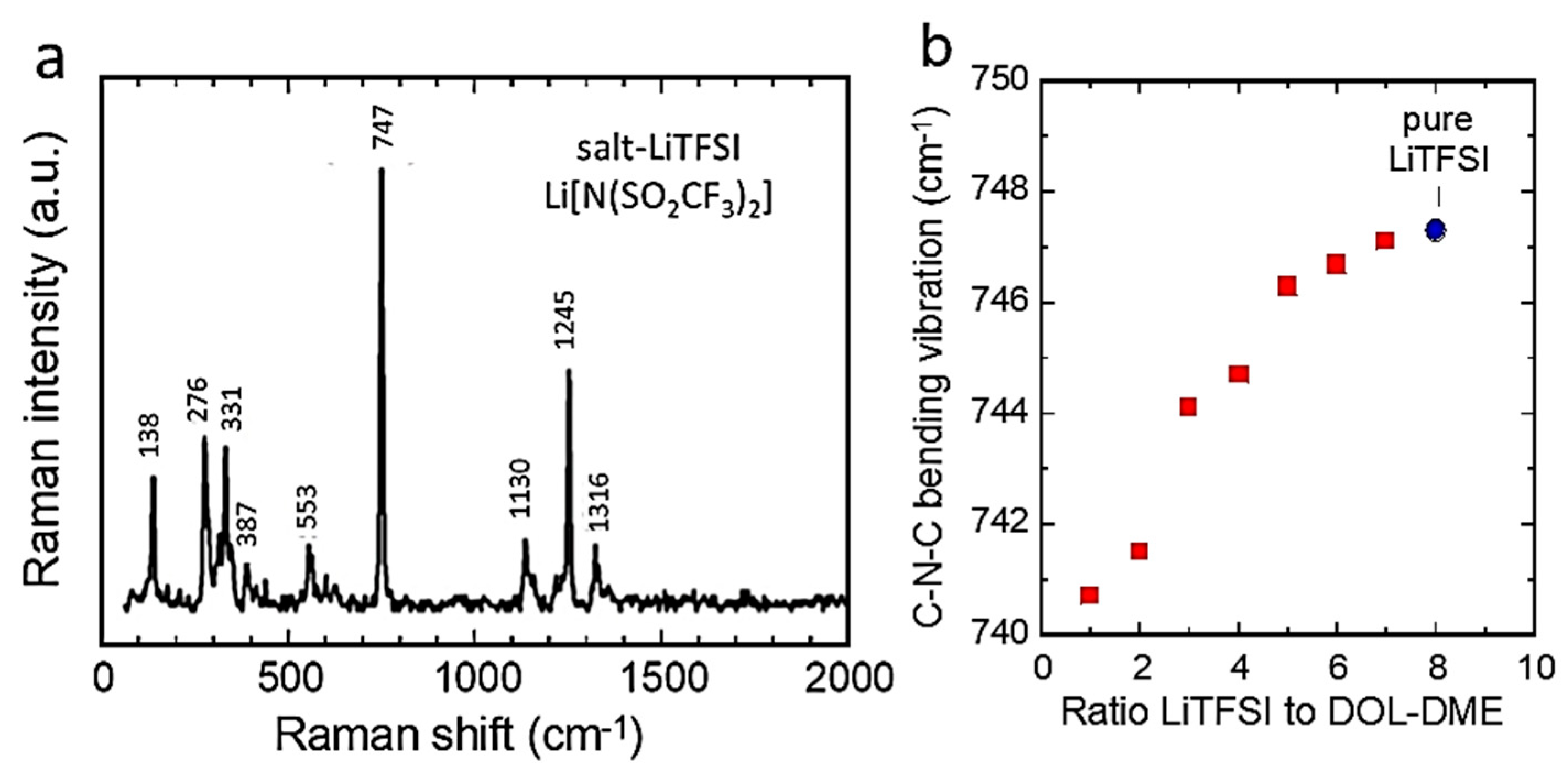

6.1. Liquid Electrolytes

6.2. Solid-State Electrolytes (SSEs)

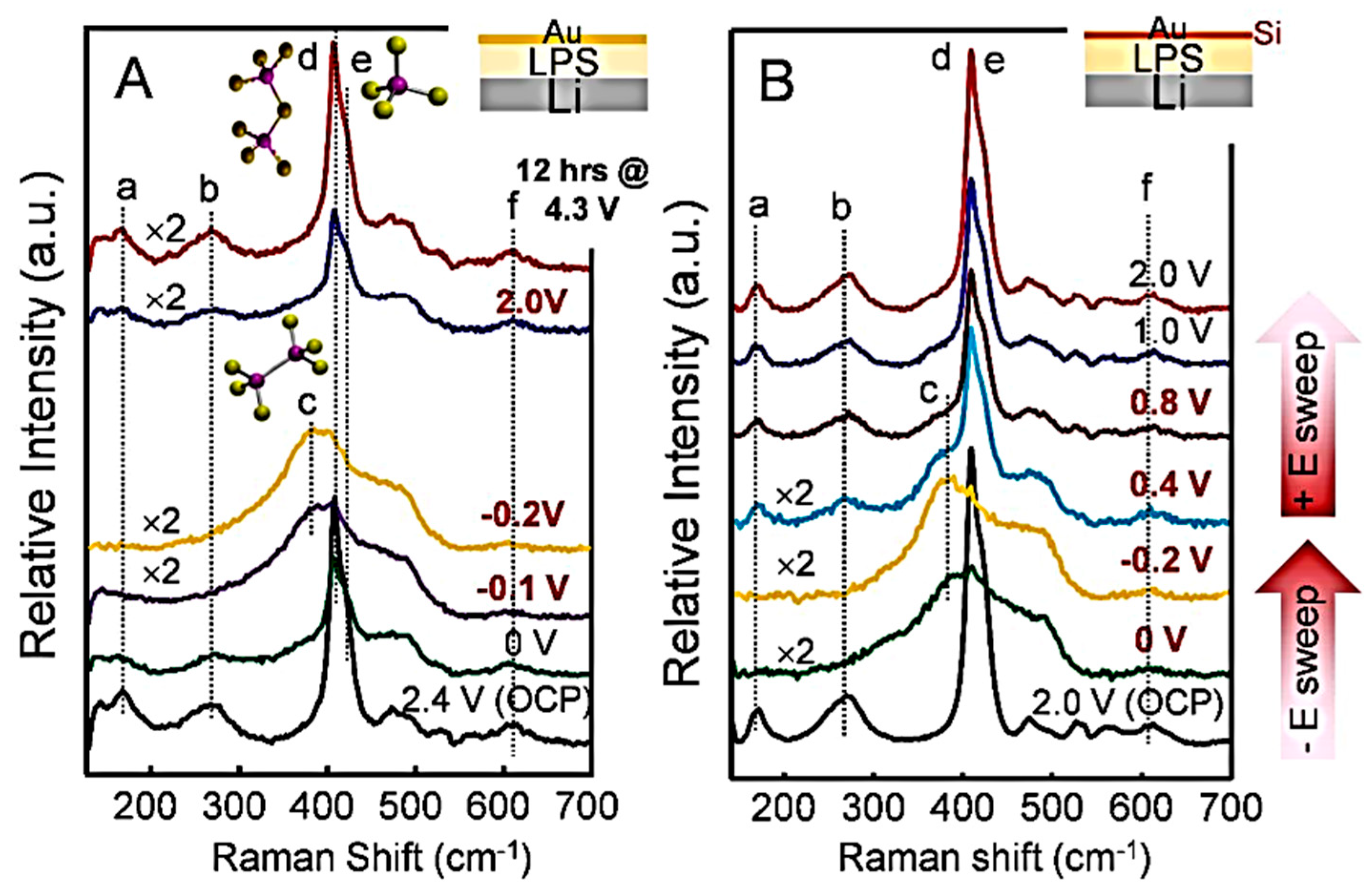

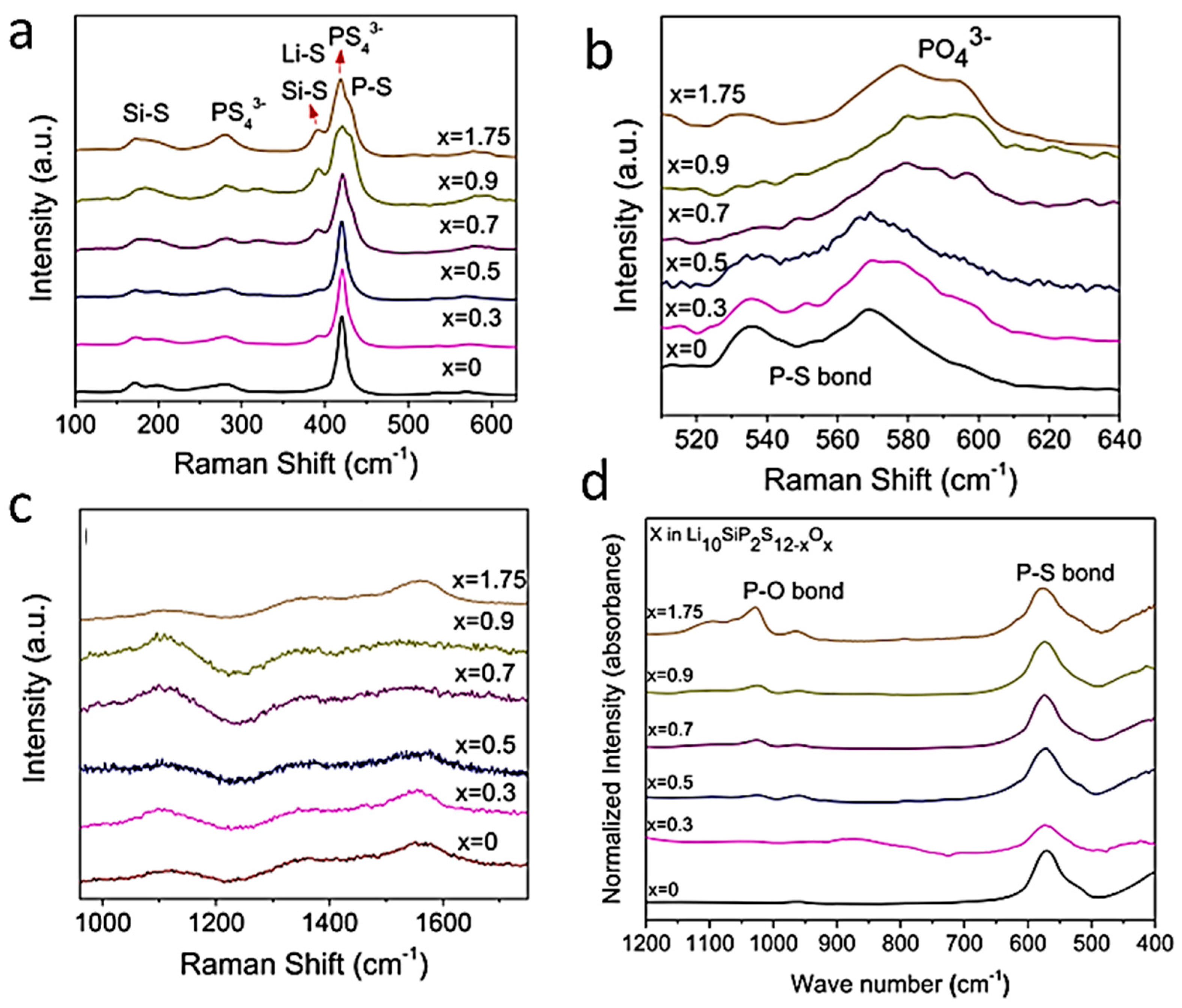

6.2.1. Sulfide Electrolytes

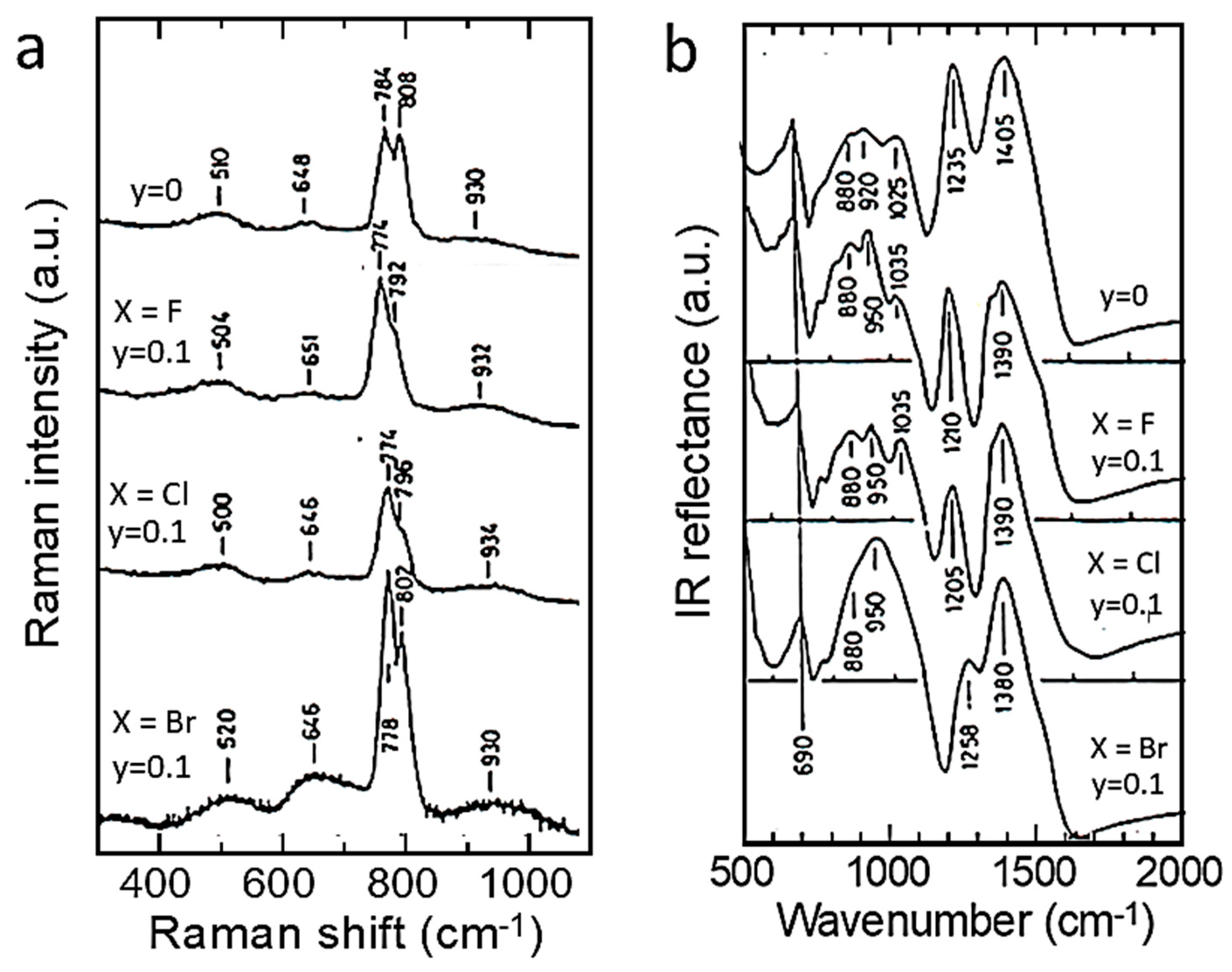

6.2.2. Oxyhalide-Type Solid Electrolytes

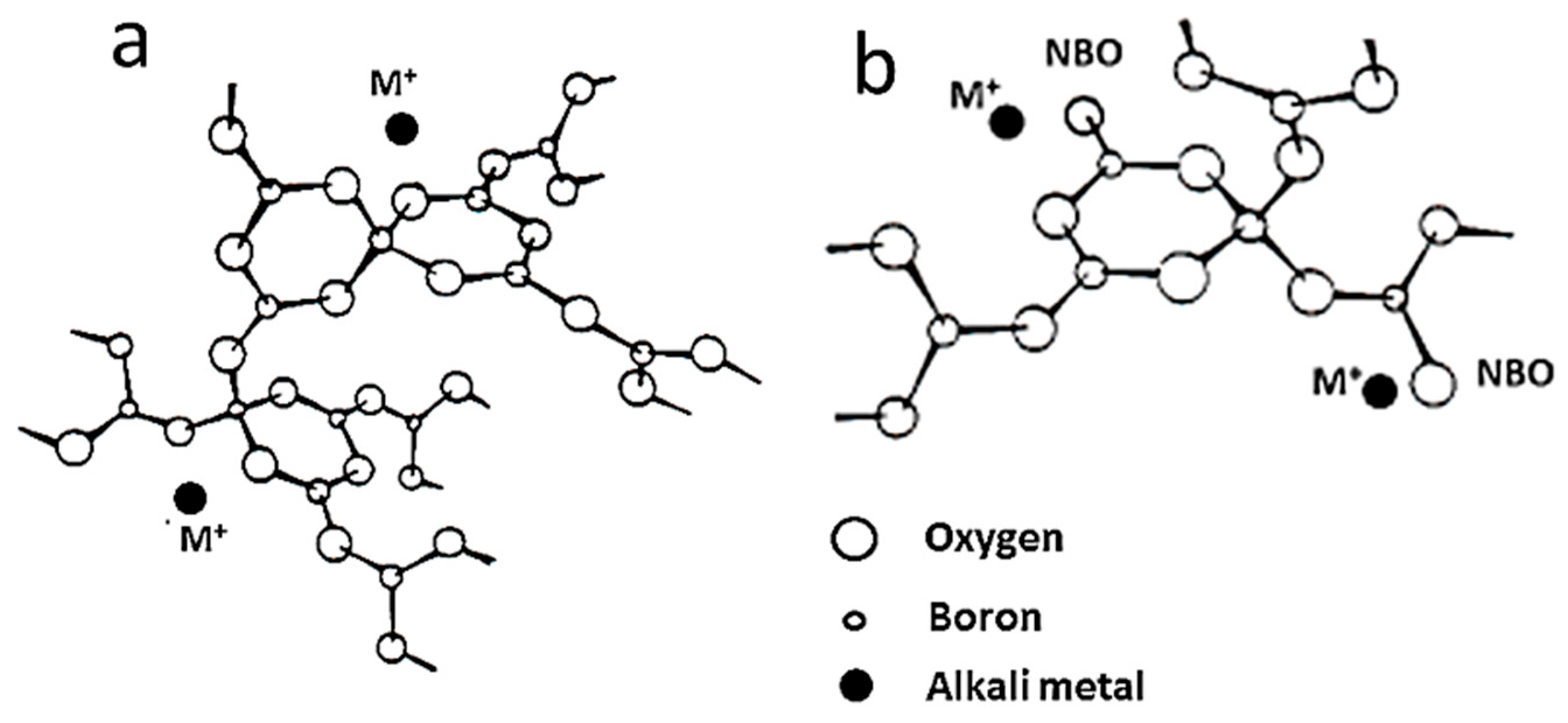

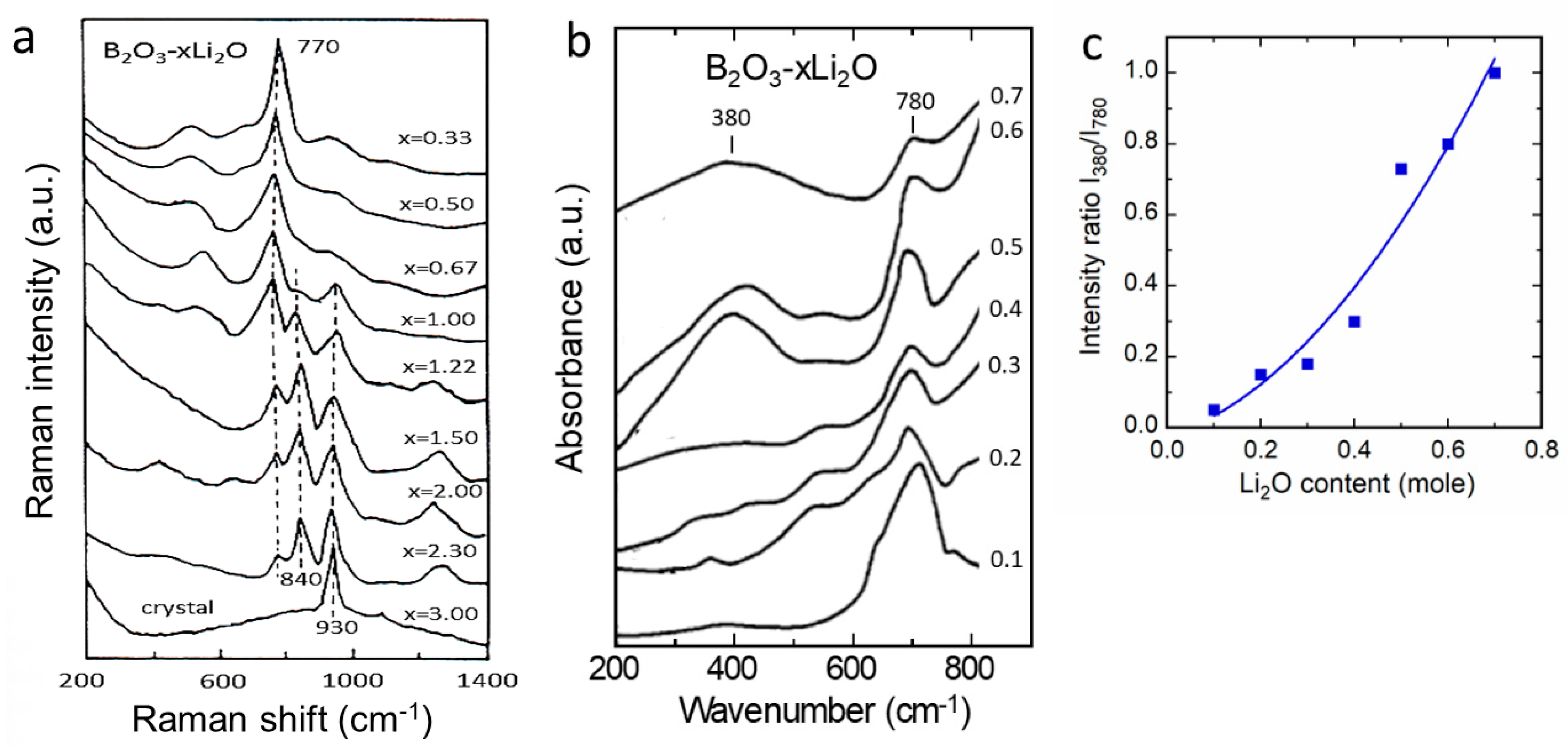

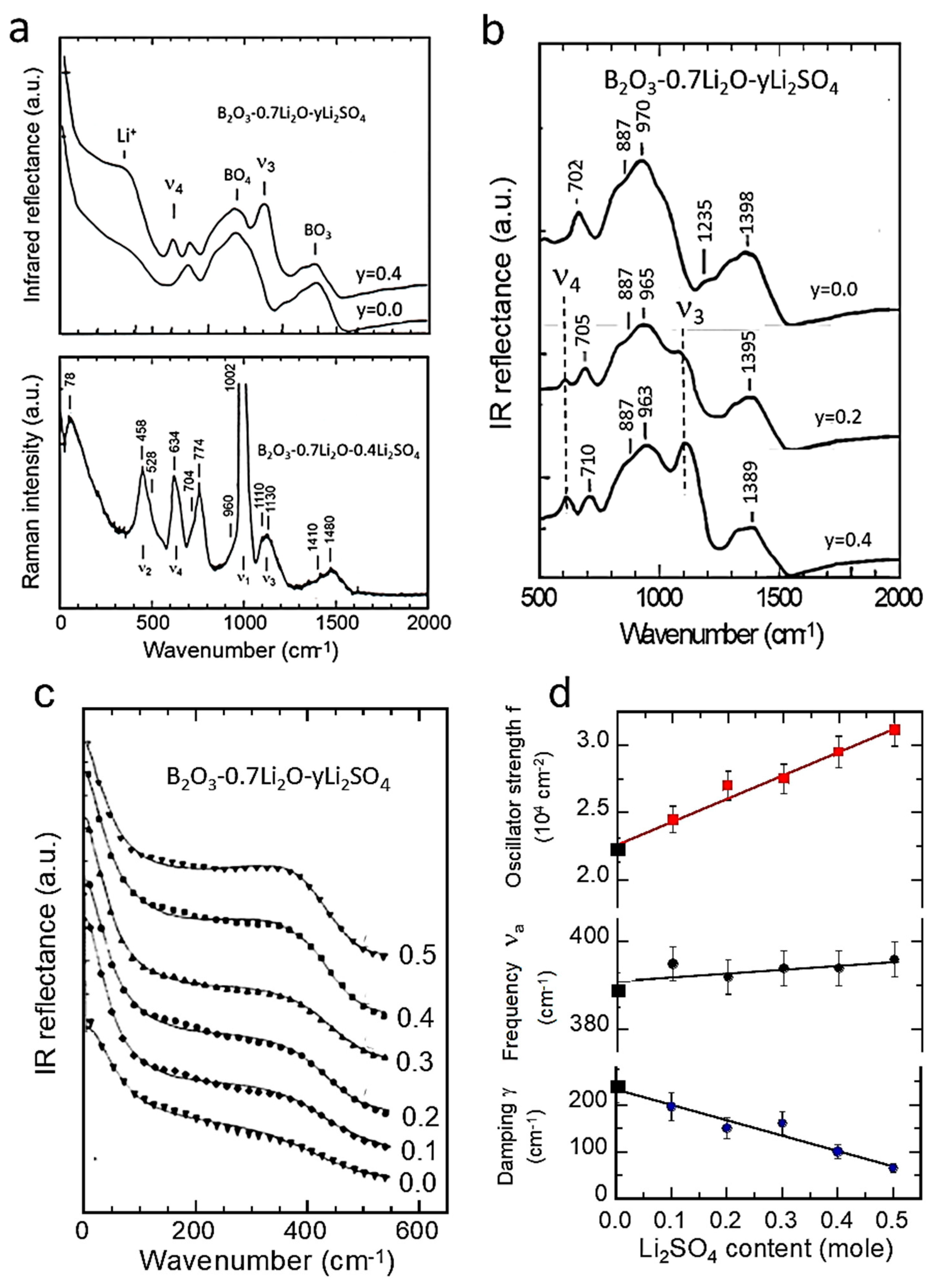

6.2.3. Oxide Glasses

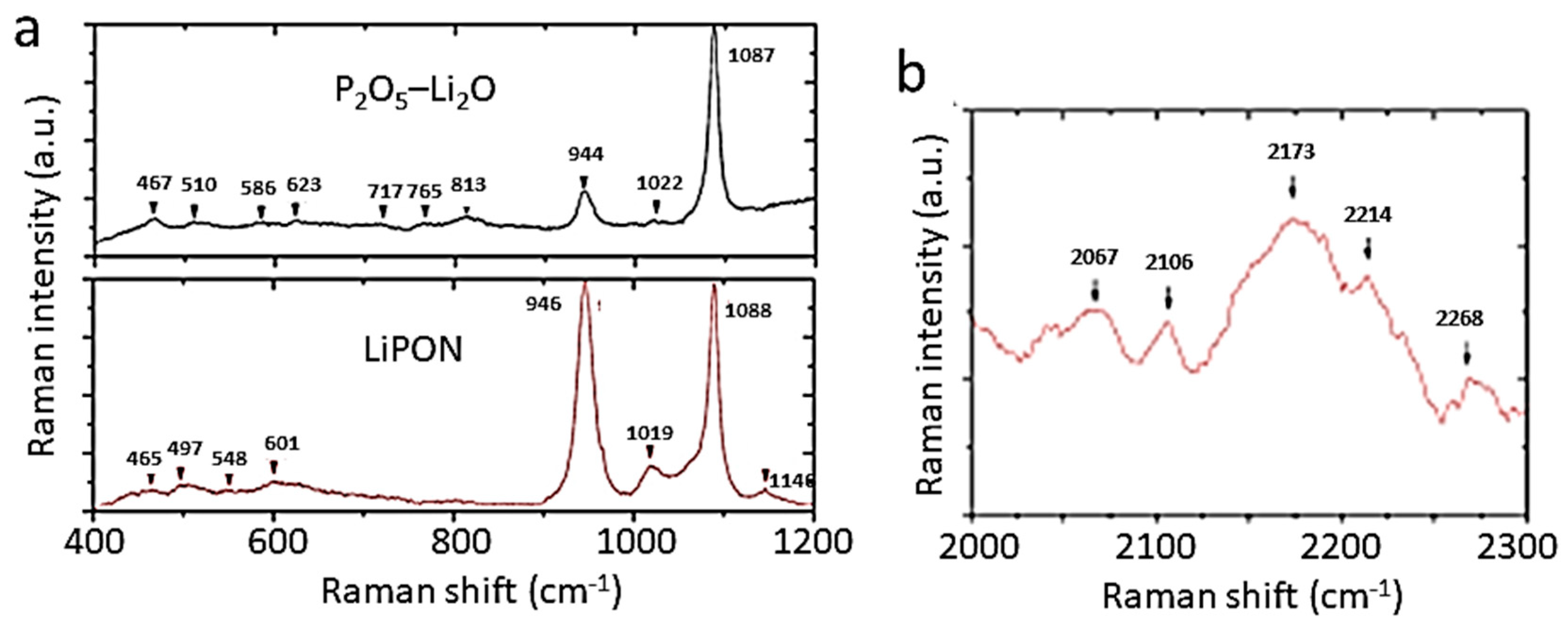

6.2.4. LiPON

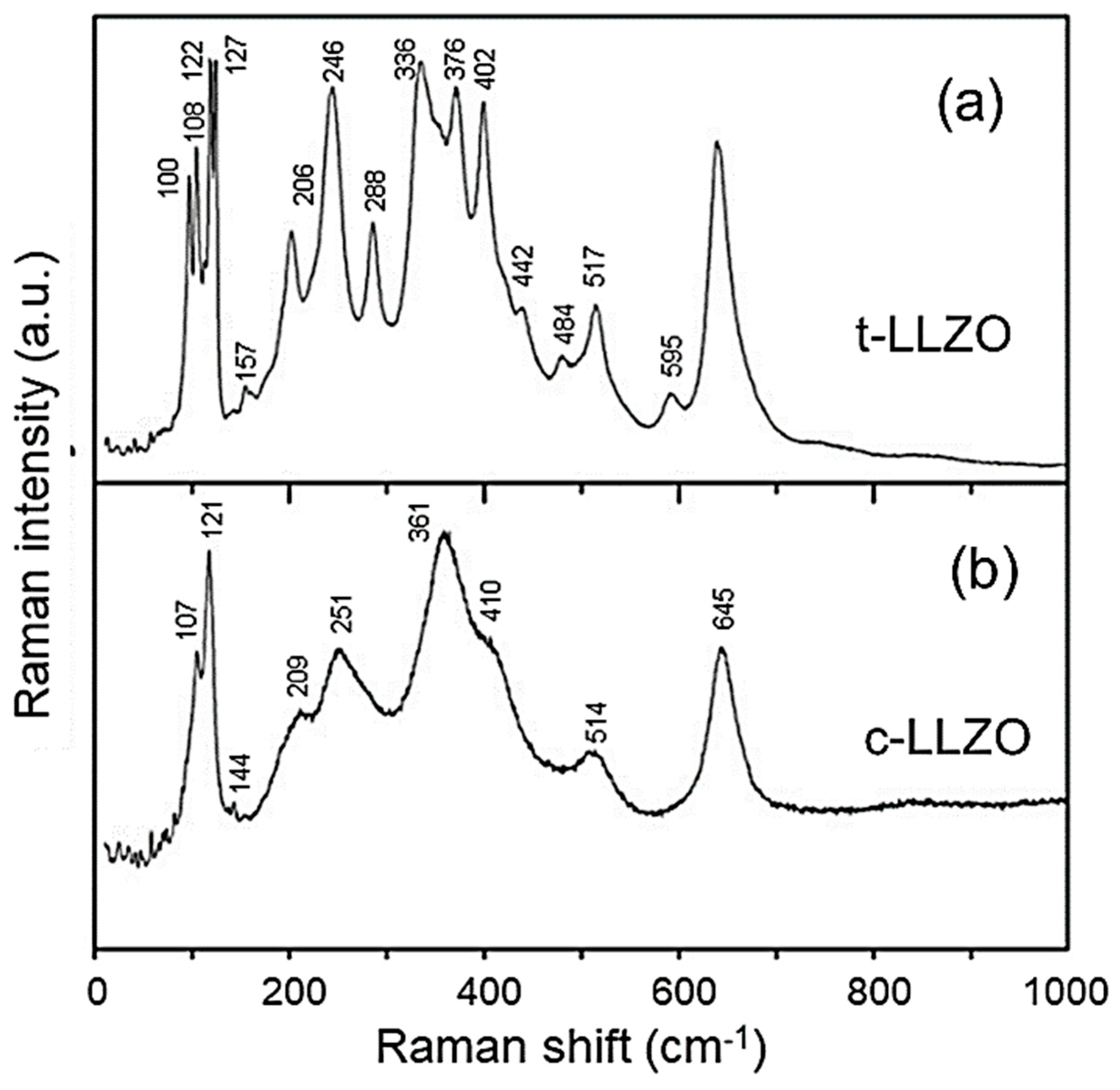

6.2.5. Garnet-Type FICs

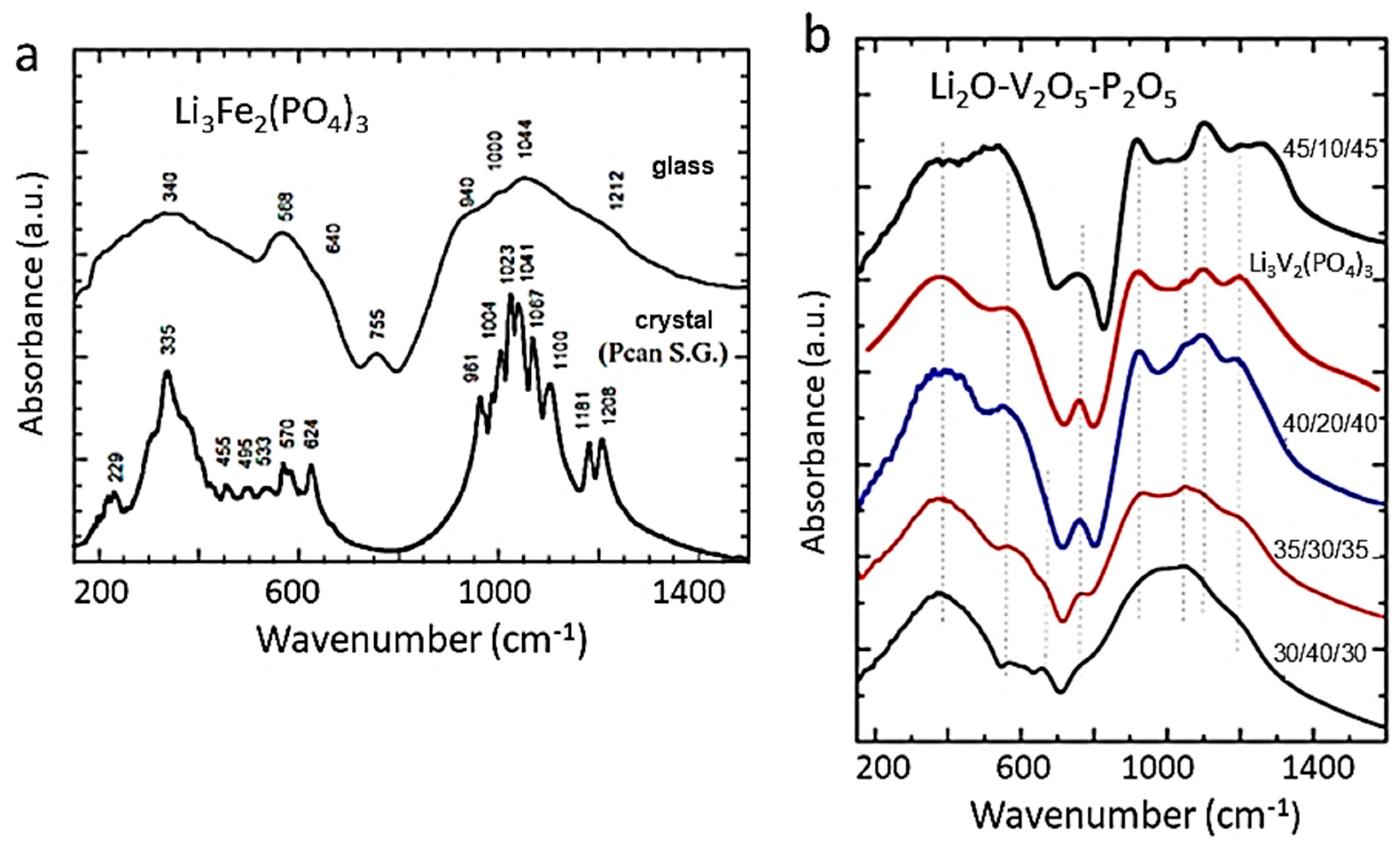

6.2.6. Nasicon-like FICs

6.2.7. Perovskite-Type FICs

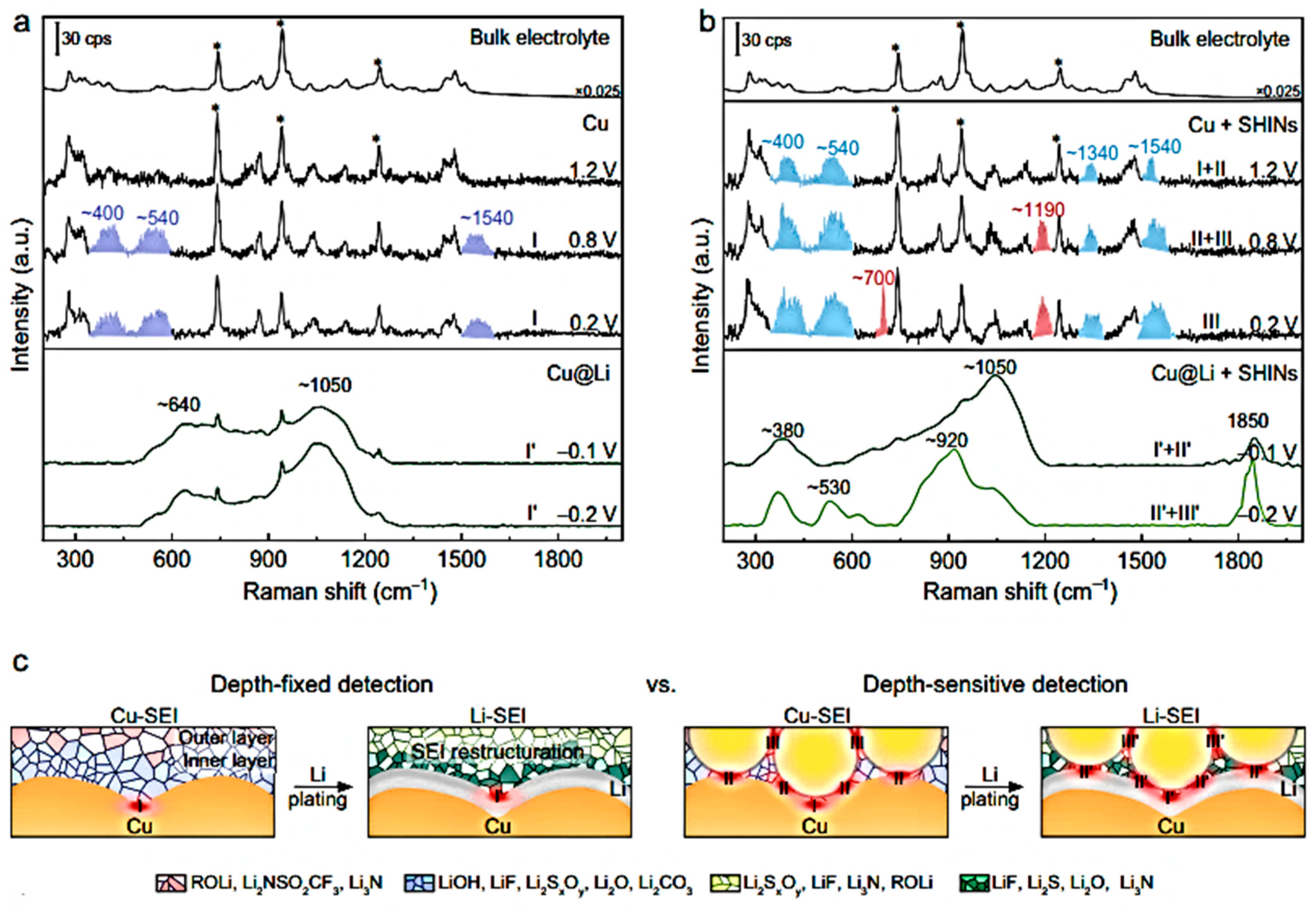

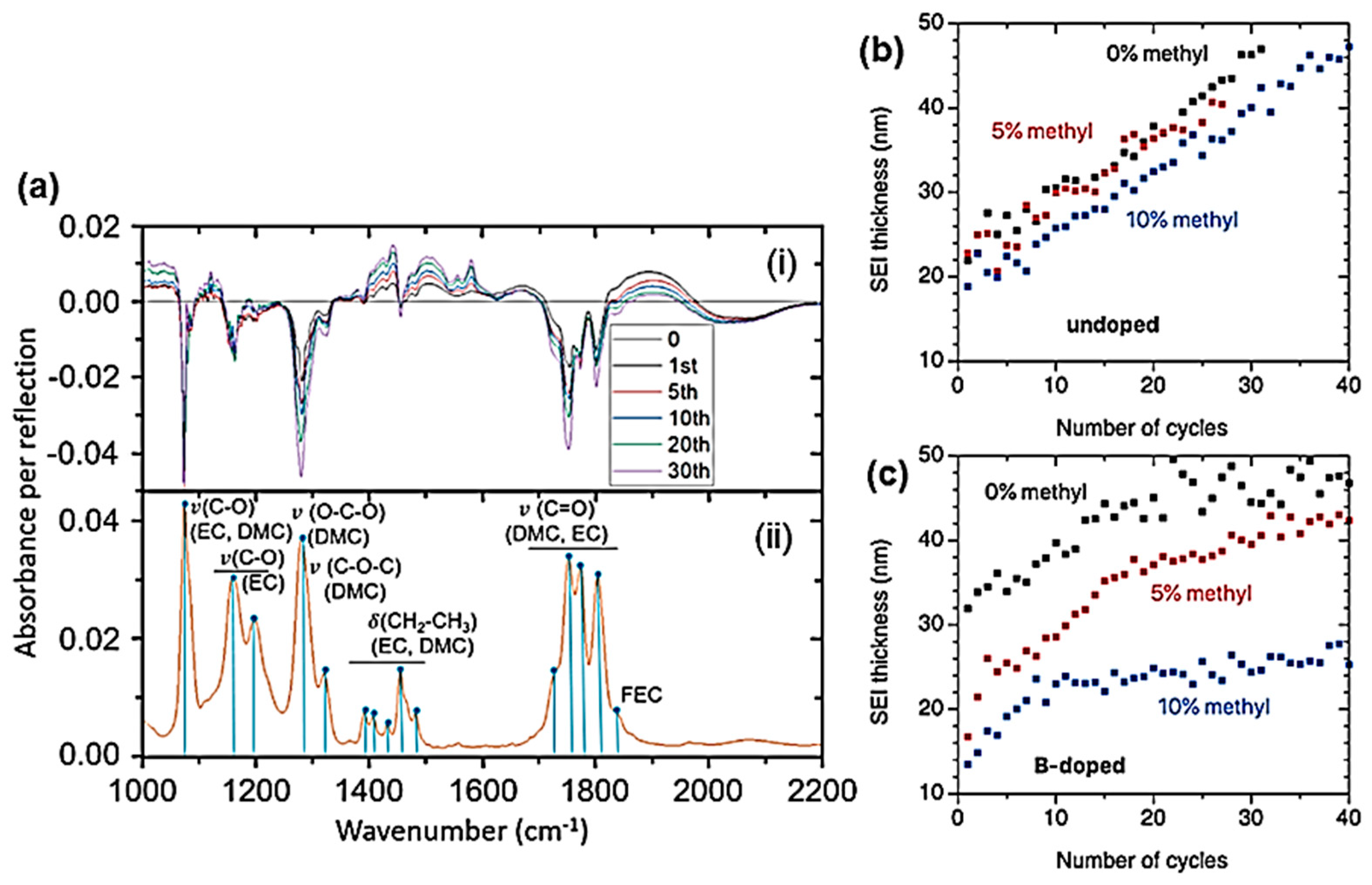

6.3. Solid Electrolyte Interphase (SEI)

6.4. Cathode Electrolyte Interphase (CEI)

7. Concluding Remarks

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| 3D | Three-dimensional |

| ASSBs | All-solid-state batteries |

| ATR | Attenuated total reflectance |

| BP | Boson peak |

| BWF | Breit–Wigner–Fano |

| CE | Counter electrode |

| CEI | Cathode electrolyte interphase |

| CN | Coordination number |

| DME | Dimethoxyethane |

| DOL | Dioxolane |

| EC | Ethylene carbonate |

| EMC | Ethyl methyl carbonate |

| FTIR | Fourier transform infrared |

| FIC | Fast ionic conductor |

| FWHM | Full-width-at-half-maximum |

| KJMA | Kolmogorov–Johnson–Mehl–Avrami |

| LATP | Li1.3Al0.3Ti1.7(PO4)3 |

| LCO | LiCoO2 |

| LFP | LiFePO4 |

| LGPS | Li10GeP2S12 |

| LIBs | Lithium-ion batteries |

| LiPON | Lithium phosphorus oxynitride |

| LiTFSI | LiN(SO2CF3)2 |

| LLTO | Li3xLa(2/3)−x(1/3)−2xTiO3 |

| LLZO | Li7La3Zr2O12 |

| LPS | Li7P3S11 |

| LNM | Li[Ni0.5Mn1.5]O4 |

| LNO | LiNiO2 |

| LSPS | Li10SiP2S12 |

| LSPSO | Li10SiP2S12−xOx |

| LTO | Li4Ti5O12 |

| LTP | LiTi2(PO4)3 |

| NBO | Non-bridging oxygen |

| NCA | LiNi0.8Co0.15Al0.05O2 |

| NMC | LiNi1−x−yMnxCoyO2 |

| PEO | Poly(ethylene oxide) |

| PERS | Plasmon-enhanced Raman spectroscopy |

| RE | Reference electrode |

| RRS | Resonance Raman spectroscopy |

| RS | Raman scattering |

| TEGDME | Tetraethylene glycol dimethyl ether |

| TMO | Transition-metal oxide |

| TMSB | Tris(trimethylsilyl)borate |

| SEI | Solid electrolyte interphase |

| SERS | Surface-enhanced Raman spectroscopy |

| SHIN | Shell-isolated nanoparticle |

| SIS | Solvent-in-salt |

| SOC | State of charge |

| SSE | Solid-state electrolyte |

| SSR | Solid-state reaction |

| TERS | Tip-enhanced Raman spectroscopy |

| VC | Vinylene carbonate |

| WE | Working electrode |

| XRD | X-ray diffraction |

References

- Julien, C.M. Local cationic environment in lithium nickel-cobalt oxides used as cathode materials for lithium batteries. Solid State Ion. 2000, 136–137, 887–896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujimori, H.; Kakihana, M.; Ioku, K.; Goto, S.; Yoshimura, M. Advantages of anti-Stokes Raman scattering for high-temperature measurements. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2001, 79, 937–939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Julien, C.M.; Mauger, A. Nano-aspect of vibration spectra methods in lithium-ion batteries. In Nanoscale Technology for Advanced Lithium Batteries; Osaka, T., Ogumi, Z., Eds.; Springer Science: New York, NY, USA, 2014; Chapter 13; pp. 167–206. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson, E.B.; Decius, J.C.; Cross, P.C. Molecular Vibrations: The Theory of Infrared and Raman Vibration Spectra; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1955. [Google Scholar]

- Exarhos, G.J. Interionic vibrations and glass transitions in ionic oxide metaphosphate glasses. J. Chem. Phys. 1974, 60, 4145–4155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarte, P.; Preudhomme, J. 6Li-7Li isotopic shifts in the infrared spectrum of inorganic lithium compounds-II. Rhombohedral LiXO2 compounds. Spectrochim. Acta A 1970, 26, 747–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duval, E.; Boukenter, A.; Champagnon, B. Vibration eigenmodes and size of microcrystallites in glass: Observation by very-low-frequency Raman scattering. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1986, 56, 2052–2055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Campbell, I.H.; Fauchet, P.M. The effects of microcrystal size and shape on the phonon Raman spectra of crystalline semiconductors. Solid State Commun. 1986, 58, 739–741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richter, H.; Wang, Z.P.; Ley, Y. The one phonon Raman spectrum in microcrystalline silicon. Solid State Commun. 1981, 39, 625–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adu, K.W.; Xiong, Q.; Gutierrez, H.R.; Chen, G.; Eklund, P.C. Raman scattering as a probe of phonon confinement and surface optical modes in semiconducting nanowires. Appl. Phys. A 2006, 85, 287–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stancovski, V.; Badilescu, S. In situ Raman spectroscopic–electrochemical studies of lithium-ion battery materials: A historical overview. J. Appl. Electrochem. 2014, 44, 23–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baddour-Hadjean, R.; Pereira-Ramos, J.P. Raman microspectrometry applied to the study of electrode materials for lithium batteries. Chem. Rev. 2010, 110, 1278–1319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Doerrer, C.; Kasemchainan, J.; Bruce, P.G.; Pasta, M.; Hardwick, L.J. Observation of interfacial degradation of Li6PS5Cl against lithium metal and LiCoO2 via in situ electrochemical Raman microscopy. Batter. Supercaps 2020, 3, 647–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gross, T.; Giebeler, L.; Hess, C. Novel in situ cell for Raman diagnostics of lithium-ion batteries. Rev. Sci. Instrum. 2013, 84, 073109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gross, T.; Hess, C. Raman diagnostics of LiCoO2 electrodes for lithium-ion batteries. J. Power Sources 2014, 256, 220–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burba, C.M.; Frech, R. Modified coin cells for in situ Raman spectro-electrochemical measurements of LixV2O5 for lithium rechargeable batteries. Appl. Spectrosc. 2006, 60, 490–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, J.-X.; Li, B.; Liu, B.; Liu, B.-J.; Zhao, J.-B.; Ren, B. Structural evolution of NM (Ni and Mn) lithium-rich layered material revealed by in-situ electrochemical Raman spectroscopic study. J Power Sources 2016, 310, 85–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghanty, C.; Markovsky, B.; Erickson, E.M.; Talianker, M.; Haik, O.; Tal-Yossef, Y.; Mor, A.; Aurbach, D.; Lampert, J.; Volkov, A.; et al. Li+-ion extraction/insertion of Ni-rich Li1+x(NiyCozMnz)wO2 (0.005 < x < 0.03; y:z = 8:1, w≈1) electrodes: In situ XRD and Raman spectroscopy study. ChemElectroChem 2015, 2, 1479–1486. [Google Scholar]

- Pollak, E.; Salitra, G.; Baranchugov, V.; Aurbach, D. In situ conductivity, impedance spectroscopy, and ex situ Raman spectra of amorphous silicon during the insertion/extraction of lithium. J. Phys. Chem. C 2007, 111, 11437–11444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuinstra, F.; Koenig, J.L. Raman spectrum of graphite. J. Chem. Phys. 1970, 53, 1126–1130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kostecki, R.; Schnyder, B.; Alliata, D.; Song, X.; Kinoshita, K.; Kötz, R. Surface studies of carbon films from pyrolyzed photoresist. Thin Solid Films 2001, 396, 36–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panitz, J.-C.; Joho, F.; Novak, P. In situ characterization of a graphite electrode in a secondary lithium-ion battery using Raman microscopy. Appl. Spectr. 1999, 53, 1188–1199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flores, E.; Novák, P.; Berg, E.J. In situ and operando Raman spectroscopy of layered transition metal oxides for Li-ion battery cathodes. Front. Energy Res. 2018, 6, 82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otoyama, M.; Ito, Y.; Hayashi, A.; Tatsumisago, M. Raman imaging for LiCoO2 composite positive electrodes in all-solid state lithium batteries using Li2SeP2S5 solid electrolytes. J. Power Sources 2016, 302, 419–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharafi, A.; Yu, S.; Naguib, M.; Lee, M.; Ma, C.; Meyer, H.M.; Nanda, J.; Chi, M.; Siegel, D.J.; Sakamoto, J. Impact of air exposure and surface chemistry on Li–Li7La3Zr2O12 interfacial resistance. J. Mater. Chem. A 2017, 5, 13475–13487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panitz, J.C.; Novák, P. Raman spectroscopy as a quality control tool for electrodes of lithium-ion batteries. J. Power Sources 2001, 97–98, 174–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kostecki, R.; Lei, J.; McLarnon, F.; Shim, J.; Sriebel, K. Diagnostic evaluation of detrimental phenomena in high-power lithium-ion batteries. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2006, 153, A669–A672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nanda, J.; Remillard, J.; O’Neill, A.; Bernardi, D.; Ro, T.; Nietering, K.E.; Go, J.-Y.; Miller, T.J. Local state-of-charge mapping of lithium-ion battery electrodes. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2011, 21, 3282–3290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ueda, H.; Ida, Y.; Kadota, K.; Tozuka, Y. Raman mapping for kinetic analysis of crystallization of amorphous drug based on distribution images. Int. J. Pharm. 2014, 462, 115–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Härtel, B.; Jonckheere, R.; Wauschkuhn, B.; Ratschbacher, L. The closure temperature(s) of zircon Raman dating. Geochronology 2021, 3, 259–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strommen, D.P.; Nakamoto, K. Resonance Raman spectroscopy. J. Chem. Educ. 1997, 54, 474–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuschel, D. Exploring resonance Raman spectroscopy. Spectroscopy 2018, 33, 12–19. [Google Scholar]

- Julien, C.M.; Massot, M. Raman scattering of LiNi1−yAlyO2. Solid State Ion. 2002, 148, 53–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ammundsen, B.; Burns, G.R.; Islam, M.S.; Kanoh, H.; Rozière, J. Lattice dynamics and vibrational spectra of lithium manganese oxides: A computer simulation and spectroscopic study. J. Phys. Chem. B 1999, 103, 5175–5180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, J.; McLarnon, F.; Kostecki, R. In situ Raman microscopy of individual LiNi0.8Co0.15Al0.05O2 particles in a Li-ion battery composite cathode. J. Phys. Chem. B 2005, 109, 952–957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dokko, K.; Mohamedi, M.; Anzue, N.; Itoh, T.; Uchida, I. In situ Raman spectroscopic studies of LiNixMn2−xO4 thin film cathode materials for lithium ion secondary batteries. J. Mater. Chem. 2002, 12, 3688–3693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerlau, M.; Marcinek, M.; Srinivasan, V.; Kostecki, R.M. Studies of local degradation phenomena in composite cathodes for lithium-ion batteries. Electrochim. Acta 2007, 53, 1385–1392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aroca, R.; Nazri, M.; Lemma, T.; Rougier, A.; Nazri, G.A. Materials for Lithium-Ion Batteries; Julien, C., Stoynov, Z., Eds.; NATO-ASI Series, Ser.3-85; Kluwer Acad. Publ.: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2000; p. 327. [Google Scholar]

- Heber, M.; Hofmann, K.; Hess, C. Raman diagnostics of cathode materials for Li-ion batteries using multi-wavelength excitation. Batteries 2022, 8, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, J.F.; Porto, S.P.S. Longitudinal and transverse optical lattice vibrations in quartz. Phys. Rev. 1967, 161, 903–910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tietz, F.; Wegener, T.; Gerhards, M.T.; Giarola, M.; Mariotto, G. Synthesis and Raman micro-spectroscopy investigation of Li7La3Zr2O12. Solid State Ion. 2013, 230, 77–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marquardt, D.W. An algorithm for least-squares estimation of nonlinear parameters. J. Soc. Ind. Appl. Math. 1963, 11, 431–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meier, R. On art and science in curve-fitting vibrational spectra. Vib. Spectrosc. 2005, 39, 266–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hiraoka, K.; Yokoyama, Y.; Mine, S.; Yamamoto, K.; Seki, S. Advanced Raman spectroscopy for battery applications: Materials characterization and operando measurements. APL Energy 2025, 3, 021502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radtke, M.; Hess, C. Operando Raman shift replaces current in electrochemical analysis of Li-ion batteries: A comparative study. Molecules 2021, 26, 4667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Julien, C.; Letranchant, C.; Rangan, S.; Lemal, M.; Ziolkiewicz, S.; Castro-Garcia, S.; El-Farh, L.; Benkaddour, M. Layered LiNi0.5Co0.5O2 cathode materials grown by soft-chemistry via various solution methods. Mater. Sci. Eng. B 2000, 76, 145–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohzuku, T.; Makimura, Y. Layered lithium insertion material LiCo1/3Ni1/3Mn1/3O2 for lithium-ion batteries. Chem. Lett. 2001, 30, 642–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koyama, Y.; Yabuuchi, N.; Tanaka, I.; Adachiand, H.; Ohzuku, T. Solid-state chemistry and electrochemistry of LiCo1/3Ni1/3Mn1/3O2 for advanced lithium-ion batteries. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2004, 151, A1545–A1551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Mauger, A.; Lu, Q.; Groult, H.; Perrigaud, L.; Gendron, F.; Julien, C.M. Synthesis and characterization of LiNi1/3Mn1/3Co1/3O2 by wet-chemical method. Electrochim. Acta 2010, 55, 6440–6449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Jiang, W.; Zhu, X.; Mauger, A.; Qilu, A.; Julien, C. Aging of LiNi1/3Mn1/3Co1/3O2 cathode material upon exposure to H2O. J. Power Sources 2011, 196, 5102–5108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brooker, M.H.; Bates, J.B. Raman and infrared spectral studies of anhydrous Li2CO3 and Na2CO3. J. Chem. Phys. 1971, 54, 4788–4796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manthiram, A.; Goodenough, J.B. Refinement of the critical V–V separation for spontaneous magnetism in oxides. Can. J. Phys. 1987, 65, 1309–1317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaghib, K.; Guerfi, A.; Charest, P.; Dontigny, M.; Labrecque, J.F.; Kopec, K.; Mauger, A.; Gendron, F.; Julien, C.M. Aging of LiFePO4 upon exposure to H2O. J. Power Sources 2008, 185, 698–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuang, G.V.; Chen, G.; Shim, J.; Song, X.; Ross, P.N.; Richardson, T.J. Li2CO3 in LiNi0.8Co0.15Al0.05O2 cathodes and its effects on capacity and power. J. Power Sources 2004, 134, 293–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Zhong, J.; Feng, J.; Li, J.; Kang, F. Highly reversible anion redox of manganese-based cathode material realized by electrochemical ion exchange for lithium-ion batteries. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2021, 31, 2103594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Julien, C.M.; Mauger, A. Review of 5-V electrodes for Li-ion batteries: Status and trends. Ionics 2013, 19, 951–988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.; Zhu, W.; Trottier, J.; Gagnon, F.; Barray, F.; Gariépy, V.; Guerfi, A.; Mauger, A.; Groult, H.; Julien, C.M.; et al. Spinel materials for high-voltage cathodes in Li-ion batteries. RSC Adv. 2014, 4, 154–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amdouni, N.; Zaghib, K.; Gendron, F.; Mauger, A.; Julien, C.M. Structure and insertion properties of disordered and ordered LiNi0.5Mn1.5O4 spinels prepared by wet chemistry. Ionics 2006, 12, 117–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gryffroy, D.; Vaudenberghe, R.E. Cation distribution, cluster structure and ionic ordering of the spinel series LiNi0.5Mn1.5−xTixO4 and LiNi0.5−yMgyMn1.5O4. J. Phys. Chem. Solids 1992, 53, 777–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padhi, A.K.; Nanjundaswamy, K.S.; Goodenough, J.B. Phospho-olivines as positive-electrode materials for rechargeable lithium batteries. J. Electrochem. Soc. 1997, 144, 1188–1194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burba, C.M.; Frech, R. Vibrational spectroscopic studies of monoclinic and rhombohedral Li3V2(PO4)3. Solid State Ion. 2007, 177, 3445–3454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abrahams, I.; Easson, K.S. Structure of lithium nickel phosphate. Acta Crystallogr. 1993, 49, 925–926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ait-Salah, A.; Mauger, A.; Julien, C.M.; Gendron, F. Nano-sized impurity phases in relation to the mode of preparation of LiFePO4. Mater. Sci. Eng. B 2006, 129, 232–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravet, N.; Gauthier, M.; Zaghib, K.; Goodenough, J.B.; Mauger, A.; Gendron, F.; Julien, C.M. Mechanism of the Fe3+ reduction at low temperature for LiFePO4 synthesis from polymeric precursor. Chem. Mater. 2007, 19, 2595–2602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ait-Salah, A.; Jozwiak, P.; Zaghib, K.; Garbarczyk, J.; Gendron, F.; Mauger, A.; Julien, C.M. FTIR features of lithium-iron phosphates as electrode materials for rechargeable lithium batteries. Spectrochim. Acta 2006, 65, 1007–1013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burba, C.M.; Frech, R.J. Raman and FTIR spectroscopic study of LixFePO4 (0 ≤ x ≤ 1). J. Electrochem. Soc. 2004, 151, A1032–A1038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucas, I.T.; McLeod, A.S.; Syzdek, J.S.; Middlemiss, D.S.; Grey, C.P.; Basov, D.N.; Kostecki, R. IR near-field spectroscopy and imaging of single LixFePO4 microcrystals. Nano Lett. 2015, 15, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ait-Salah, A.; Jozwiak, P.; Garbarczyk, J.; Benkhouja, K.; Zaghib, K.; Gendron, F.; Julien, C.M. Local structure and redox energies of lithium phosphates with olivine- and Nasicon-like structures. J. Power Sources 2005, 140, 370–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barj, M.; Lucazeau, G.; Delmas, C. Raman and infrared spectra of some chromium Nasicon-type materials: Short-range disorder characterization. J. Solid State Chem. 1992, 100, 141–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okazaki, S.; Ohtori, N.; Okada, I. Raman spectroscopic study on the vibrational and rotational relaxation of OH− ions in molten LiOH. 1989. J. Chem. Phys. 1989, 91, 5587–5592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knight, D.S.; White, W.B. Characterization of diamond films by Raman spectroscopy. J. Mater. Res. 1989, 4, 385–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pocsik, I.; Hundhausen, M.; Koos, M.; Ley, L. Origin of the D peak in the Raman spectrum of microcrystalline graphite. J. Non-Cryst. Solids 1998, 227–230, 1083–1086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrari, A.C.; Robertson, J. Interpretation of Raman spectra of disordered and amorphous carbon. Phys. Rev. B 2000, 61, 14095–14107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrari, A.C.; Robertson, J. Resonant Raman spectroscopy of disordered, amorphous and diamondlike carbon. Phys. Rev. B 2001, 64, 075414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chien, C.; Dresselhaus, G.; Endo, M. Raman studies of benzene-derived graphite fibers. Phys. Rev. B 1982, 26, 5867–5877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakata, H.; Dresselhaus, G.; Dresselhaus, M.S.; Endo, M. Effect of uniaxial stress on the Raman spectra of graphite fibers. J. Appl. Phys. 1988, 63, 2769–2772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Young, R.J. Effect of fibre microstructure upon the modulus of PAN- and pitch-based carbon. Carbon 1995, 33, 97–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robertson, J.; O’Reilly, E.P. Electronic and atomic structure of amorphous carbon. Phys. Rev. B 1987, 35, 2946–2957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Young, R.J.; Broadbridge, A.; So, S.L. Analysis of SiC fibres and composites using Raman microscopy. J. Microsc. 1999, 196, 257–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, X.; Li, H.; Zhao, Z.; Wang, Y.; Wang, X. The use of in-situ Raman spectroscopy in investigating carbon materials as anodes of alkali metal-ion batteries. New Carbon Mater. 2021, 36, 93–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Julien, C.M.; Zaghib, K.; Mauger, A.; Massot, M.; Ait-Salah, A.; Selmane, M.; Gendron, F. Characterization of the carbon-coating onto LiFePO4 particles used in lithium batteries. J. Appl. Phys. 2006, 100, 63511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaghib, K.; Mauger, A.; Gendron, F.; Julien, C.M. Surface effects on the physical and electrochemical properties of thin LiFePO4 particles. Chem. Mater. 2008, 20, 462–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, J.; Sole, C.; Drewett, N.E.; Velicky, M.; Harwick, L.J. In situ study of Li intercalation into highly crystalline graphitic flakes of varying thicknesses. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2016, 7, 4291–4296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piscanec, S.; Contoro, M.; Ferrari, A.C.; Zapien, J.A.; Lifshitz, Y.; Lee, S.T.; Hoffman, S.H.; Robertson, J. Raman spectroscopy of silicon nanowires. Phys Rev B 2003, 68, 241312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.B.; Ju, D.P.; Zhang, S.L. Raman spectral study of silicon nanowires. Phys. Rev. B 1999, 59, 1645–1648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Kraytsberg, A.; Ein-Eli, Y. In-situ Raman spectroscopy mapping of Si based anode material lithiation. J. Power Sources 2015, 282, 294–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tardif, S.; Pavlenko, E.; Quazuguel, L.; Boniface, M.; Marechal, M.; Micha, J.-S.; Gonon, L.; Mareau, V.; Gebel, G.; Bayle-Guillemaud, P.; et al. Operando Raman spectroscopy and synchrotron X-ray diffraction of lithiation/delithiation in silicon nanoparticle anodes. ACS Nano 2017, 11, 11306–11316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krause, A.; Tkacheva, O.; Omar, A.; Langklotz, U.; Giebeler, L.; Dorfler, S.; Fauth, F.; Mikolajick, T.; Weber, W.M. In situ Raman spectroscopy on silicon nanowire anodes integrated in lithium ion batteries. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2019, 166, A5378–A5385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colbow, K.M.; Dahn, J.R.; Haering, R.R. Structure and electrochemistry of the spinel oxides LiTi2O4 and Li4/3Ti5/3O4. J. Power Sources 1989, 26, 397–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Julien, C.M.; Mauger, A. Fabrication of Li4Ti5O12 (LTO) as anode material for Li-ion batteries. Micromachines 2024, 15, 310. [Google Scholar]

- Ohsaka, T. Temperature dependence of the Raman spectrum in anatase TiO2. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 1980, 48, 1661–1668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.A.; Huang, Y.S.; Chung, W.H.; Tsai, D.S.; Tiong, K.K. Raman spectroscopy study of the phase transformation on nanocrystalline titania films prepared via metal organic vapor deposition. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Electron. 2009, 20, 303–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, C.Y.; Zhang, P.X.; Yan, L. Blue shift of Raman peak from coated TiO2 nanoparticles. J. Raman Spectrosc. 2001, 32, 862–865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, H.C.; Jung, Y.M.; Kim, S.B. Size effects in the Raman spectra of TiO2 nanoparticles. Vib. Spectrosc. 2005, 37, 33–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.Z.; Hayes, W.; Kurmoo, M.; Dalton, M.; Chen, C. Raman scattering of the Li1+xTi2−xO4 superconducting system. Phys. C 1994, 235–240, 1203–1204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldon, L.; Kubiak, P.; Womes, M.; Jumas, J.C.; Olivier-Fourcade, J.; Tirado, J.L.; Corredor, J.I.; Perez-Vicente, C. Chemical and electrochemical Li-insertion into the Li4Ti5O12 spinel. Chem. Mater. 2004, 16, 5721–5725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narayanan, P.S. Raman spectrum of rutile (TiO2). Proc. Math. Sci. 1950, 32, 279–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porto, S.P.S.; Fleury, P.A.; Damen, T.C. Raman spectra of TiO2, MgF2, ZnF2, FeF2 and MnF2. Phys. Rev. 1967, 154, 522–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Challagulla, S.; Tarafder, K.; Ganesan, R.; Roy, S. Structure sensitive photocatalytic reduction of nitroarenes over TiO2. Sci. Rep. 2017, 17, 8783. [Google Scholar]

- Proskuryakova, E.V.; Kondratov, Q.I.; Porotnikov, N.V.; Petrov, K.I. Vibrational spectra of lithium titanate with spinel structure. Zh. Neorg. Khim. 1983, 28, 1402–1406. [Google Scholar]

- Kalbáč, M.; Zukalová, M.; Kavan, L. Phase-pure nanocrystalline Li4Ti5O12 for a lithium-ion battery. J. Solid State Electrochem. 2003, 8, 2–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leonidov, I.A.; Leonidova, O.N.; Perelyaeva, L.A.; Samigullina, R.F.; Kovyazina, S.A.; Patrakeev, M.V. Structure, ionic conduction, and phase transformations in lithium titanate Li4Ti5O12. Phys. Solid State 2003, 45, 2183–2188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Julien, C.M.; Zaghib, K. Electrochemistry and local structure of nano-sized Li4/3Me5/3O4 (Me=Mn, Ti) spinels. Electrochim. Acta 2004, 50, 411–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, S.T.; Hine, N.D.M. Point defects and non-stoichiometry in Li2TiO3. Chem. Mater. 2014, 26, 1629–1638. [Google Scholar]

- Julien, C.M.; Massot, M. Lattice vibrations of materials for lithium rechargeable batteries. III Lithium manganese oxides. Mater. Sci. Eng. B 2003, 100, 69–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Endres, P.; Fuchs, B.; Kemmler-Sack, S.; Brandt, K.; Faust-Becker, G.; Praas, H.W. Influence of processing on the Li:Mn ratio in spinel phases of the system Li1+xMn2−xO4–δ. Solid State Ion. 1996, 89, 221–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pelegov, D.V.; Nasara, R.N.; Tu, C.; Lin, S. Defects in Li4Ti5O12 induced by carbon deposition: An analysis of unidentified bands in Raman spectra. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2019, 21, 20757–20763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nikiforov, A.A.; Krylov, A.S.; Krylova, S.N.; Gorshkov, V.S.; Pelegov, D.V. Temperature Raman study of Li4Ti5O12 and ambiguity in the number of its bands. J. Raman Spectr. 2024, 55, 406–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, L.; Curran, D.; Brow, R.; Santhanagopalan, S.; Porter, J. Operando measurements of electrolyte Li-ion concentration during fast charging with FTIR/ATR. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2021, 168, 090502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miele, E.; Dose, W.M.; Manyakin, I.; Frosz, M.H.; Ruff, Z.; De Volder, M.F.L.; Grey, C.P.; Baumberg, J.J.; Euser, T.G. Hollow-core optical fibre sensors for operando Raman spectroscopy investigation of Li-ion battery liquid electrolytes. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 1651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Y.; Cai, W.-B.; Xing, X.-K.; Scherson, D.A. In situ, time resolved Raman spectromicrotopography of an operating lithium ion battery. Electrochem. Solid-State Lett. 2004, 7, E1–E5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alía, J.M.; Edwards, H.G.M.; Lawson, E.E. Preferential solvation and ionic association in lithium and silver trifluomethanesulfonate solutions in acrylonitrile/dimethylsulfoxide mixed solvent a Raman spectroscopic study. Vibrat. Spectrosc. 2004, 34, 187–197. [Google Scholar]

- Markarian, S.A.; Gabrielian, L.S.; Zatikyan, A.L.; Bonora, S.; Trinchero, A. FT-IR and Raman study of lithium salts solutions in diethylsulfoxide. Vibrat. Spectrosc. 2005, 39, 220–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardwick, L.J.; Holzapfel, M.; Wokaun, A.; Novak, P. Raman study of lithium coordination in EMI-TFSI additive systems as lithium-ion battery ionic liquid electrolytes. J. Raman Spectrosc. 2007, 38, 110–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forster, J.D.; Harris, S.J.; Urban, J.J. Mapping Li+ concentration and transport via in situ confocal Raman microscopy. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2014, 5, 2007–2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamanaka, T.; Nakagawa, H.; Tsubouchi, S.; Domi, Y.; Doi, T.; Abe, T.; Ogumi, Z. In situ diagnosis of the electrolyte solution in a laminate lithium ion battery by using ultrafine multi-probe Raman spectroscopy. J. Power Sources 2017, 359, 435–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rey, I.; Bruneel, J.-L.; Grondin, J.; Servant, L.; Lassegues, J.-C. Raman spectroelectrochemistry of a lithium/polymer electrolyte symmetric cell. J. Electrochem. Soc. 1998, 145, 3034–3042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.-S.; Jeong, S.-K. Raman spectroscopy for understanding of lithium intercalation into graphite in propylene carbonated-based solutions. J. Spectrosc. 2015, 2015, 323649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klassen, B.; Aroca, R.; Nazri, M.; Nazri, G.A. Raman spectra and transport properties of lithium perchlorate in ethylene carbonate based binary solvent systems for lithium batteries. J. Phys. Chem. B 1998, 102, 4795–4801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Q.; Wei, L.; Liu, Z.; Ni, N.; Sang, Z.; Zhu, B.; Xu, W.; Chen, M.; Miao, Y.; Chen, L.-Q.; et al. Operando and three-dimensional visualization of anion depletion and lithium growth by stimulated Raman scattering microscopy. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 2942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Georén, P.; Adebahr, J.; Jacobsson, P.; Lindbergh, G. Concentration polarization of a polymer electrolyte. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2002, 149, A1015–A1019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, H.-Y.; Fukutsuka, T.; Miyazaki, K.; Abe, T. In situ Raman investigation of electrolyte solutions in the vicinity of graphite negative electrodes. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2016, 18, 27486–27492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suo, L.; Zheng, F.; Hu, Y.-S.; Chen, L. FT-Raman spectroscopy study of solvent-in-salt electrolytes. Chinese Phys. B 2016, 25, 016101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rey, I.; Lassègues, J.C.; Grondin, J.; Servant, L. Infrared and Raman study of the PEO-LiTFSI polymer electrolyte. Electrochim. Acta 1998, 43, 1505–1510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Katayama, Y.; Tatara, R.; Giordano, L.; Yu, Y.; Fraggedakis, D.; Sun, J.G.; Maglia, F.; Jung, R.; Bazant, M.Z.; et al. Revealing electrolyte oxidation via carbonate dehydrogenation on Ni-based oxides in Li-ion batteries by in situ Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy. Energy Environ. Sci. 2020, 13, 183–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fawdon, J.; Ihli, J.; La Mantia, F.; Pasta, M. Characterizing lithium-ion electrolytes via operando Raman microspectroscopy. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 4053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reddy, M.V.; Julien, C.M.; Mauger, A.; Zaghib, K. Sulfide and oxide inorganic solid electrolytes for all-solid-state batteries: A review. Nanomaterials 2020, 10, 1606. [Google Scholar]

- Borjesson, L.; Torell, L.M. Raman scattering evidence of rotating SO42− in solid sulphate electrolytes. Solid State Ion. 1986, 18–19, 582–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Zheng, C.; Li, L.; Xia, Y.; Huang, H.; Gan, Y.; Liang, C.; He, X.; Tao, X.; Zhang, W. Unraveling the intra and intercycle interfacial evolution of Li6PS5Cl-based all-solid-state lithium batteries. Adv. Energy Mater. 2020, 10, 1903311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hakari, T.; Deguchi, M.; Mitsuhara, K.; Ohta, T.; Saito, K.; Orikasa, Y.; Uchimoto, Y.; Kowada, Y.; Hayashi, A.; Tatsumisago, M. Structural and electronic-state changes of a sulfide solid electrolyte during the Li deinsertion–insertion processes. Chem. Mater. 2017, 29, 4768–4774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sang, L.; Bassett, K.L.; Castro, F.C.; Young, M.J.; Chen, L.; Haasch, R.T.; Elam, J.W.; Dravid, V.P.; Nuzzo, R.G.; Gewirth, A.A. Understanding the effect of interlayers at the thiophosphate solid electrolyte/lithium interface for all solid-state Li batteries. Chem. Mater. 2018, 30, 8747–8756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dietrich, C.; Weber, D.A.; Sedlmaier, S.J.; Indris, S.; Culver, S.P.; Walter, D.; Janek, J.; Zeier, W.G. Lithium ion conductivity in Li2S-P2S5 glasses-building units and local structure evolution during the crystallization of superionic conductors Li3PS4, Li7P3S11 and Li4P2S7. J. Mater. Chem. A 2017, 5, 18111–18119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preefer, M.B.; Grebenkemper, J.H.; Schroeder, F.; Bocarsly, J.D.; Pilar, K.; Cooley, J.A.; Zhang, W.; Hu, J.; Misra, S.; Seeler, F.; et al. Rapid and tunable assisted-microwave preparation of glass and glass-ceramic thiophosphate “Li7P3S11” Li-ion conductors. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2019, 11, 42280–42287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Guan, H.; Ma, Z.; Liang, M.; Song, D.; Zhang, H.; Shi, X.; Li, C.; Jiao, L.; Zhang, L. In/ex-situ Raman spectra combined with EIS for observing interface reactions between Ni-rich layered oxide cathode and sulfide electrolyte. J. Energy Chem. 2020, 48, 195–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.H.; Martin, S.W. Structures and properties of oxygen-substituted Li10GeP2S12−xOx solid-state electrolytes. Chem. Mater. 2019, 31, 3984–3991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.-T.; Marple, M.A.T.; Tan, D.H.S.; Ham, S.-Y.; Sayahpour, B.; Li, W.-K.; Yang, H.; Lee, J.B.; Hah, H.J.; Wu, E.A.; et al. Investigating dry room compatibility of sulfide solid-state electrolytes for scalable manufacturing. J. Mater. Chem. A 2022, 10, 7155–7164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, W.; Cui, Y.; Long, Z.; Shan, H.; Chamidah, N.; Yamamoto, K.; Kotobuki, M.; Li, H.; Hu, N.; Song, S. New oxyhalide solid electrolytes with enhanced conductivity for all-solid-state batteries. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2025, 16, 8283–8289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwak, H.; Han, D.; Lyoo, J.; Park, J.; Jung, S.H.; Han, Y.; Kwon, G.; Kim, H.; Hong, S.; Nam, K.; et al. New cost-effective halide solid electrolytes for all-solid-state batteries: Mechanochemically prepared Fe3+-substituted Li2ZrCl6. Adv. Energy Mater. 2021, 11, 2003190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, S.; Wei, F.; Xue, W.; Cui, Y.; Long, Z.; Shan, H.; Hu, N. Amorphous oxyhalide solid electrolytes with improved ionic conductivity and reductive stability for all-solid-state batteries. J. Mater. Chem. A 2025, 13, 26478–26486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeon, H.-J.; Subramanian, Y.; Ryu, K.-S. Variation of electrochemical performance of Li2ZrCl6 halide solid electrolyte with Mn substitution for all-solid-state batteries. J. Power Sources 2024, 602, 234343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Xu, X.; Cui, C.; Zeng, C.; Liang, J.; Fu, J.; Zhang, R.; Zhai, T.; Li, H. Air sensitivity and degradation evolution of halide solid state electrolytes upon exposure. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2022, 32, 2108805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Liang, J.; Li, M.; Adair, K.R.; Li, X.; Hu, Y.; Xiao, Q.; Feng, R.; Li, R.; Zhang, L.; et al. Unraveling the origin of moisture stability of halide solid-state electrolytes by in situ and operando synchrotron X-ray analytical techniques. Chem. Mater. 2020, 32, 7019–7027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilo, J.A.V.; Chang, C.K.; Chuang, Y.C.; Fang, M.H. Coprecipitation strategy for halide-based solid-state electrolytes and atmospheric-dependent in situ analysis. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2024, 16, 27394–27399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Usami, T.; Tanibata, N.; Takeda, H.; Nakayama, M. Influence of atmospheric moisture on the gas evolution tolerance of halide solid electrolyte. J. Solid State Electrochem. 2024, 28, 4427–4436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Liang, J.; Adair, K.R.; Li, J.; Li, W.; Zhao, F.; Hu, Y.; Sham, T.K.; Zhang, L.; Zhao, S.; et al. Origin of superionic Li3Y1−xInxCl6 halide solid electrolytes with high humidity tolerance. Nano Lett. 2020, 20, 4384–4392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Levasseur, A.; Brethous, J.C.; Réau, J.M.; Hagenmuller, P. Etude comparée de la conductivité ionique du lithium dans les halogenoborates vitreux. Mater. Res. Bull. 1979, 14, 921–927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krogh-Moe, J. The structure of vitreous and liquid boron oxide. J. Non-Cryst. Solids 1969, 1, 269–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamitsos, E.I.; Patsis, A.P.; Karakassides, M.A.; Chryssikos, G.D. Infrared reflectance spectra of lithium borate glasses. J. Non-Cryst. Solids 1990, 126, 52–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamitsos, E.I.; Karakassides, M.A.; Chryssikos, G.D. A vibrational study of lithium sulfate based fast ionic conducting borate glasses. J. Phys. Chem. 1986, 90, 4528–4533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massot, M.; Haro, E.; Oueslati, M.; Balkanski, M.; Levasseur, A.; Menetrier, M. Structural investigation of doped lithium borate glasses. Mater. Sci. Eng. B 1989, 3, 57–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Julien, C.; Massot, M.; Balkanski, M.; Krol, A.; Nazarewicz, W. Infrared studies of the structure of borate glasses. Mater. Sci. Eng. B 1989, 3, 307–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balkanski, M.; Darianian, I.; Buret, P.A.; Massot, M.; Julien, C. Dynamical properties of lithium in borate glasses B2O3-xLi2O-yLi2SO4 deduced from IR spectroscopy. Mater. Sci. Eng. B 1989, 3, 177–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turcotte, D.E.; Risen, W.M.; Kamitsos, E.I. A Raman study of lithium fluoride containing fast ionic conducting glasses. Solid State Commun. 1984, 51, 313–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massot, M.; Haro, E.; Oueslati, M.; Balkanski, M. Spectroscopic studies of fast ionic conducting halogenaborate glasses. Mat. Res. Soc. Symp. Proc. 1988, 135, 207–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shuker, R.; Gammon, R.W. Raman-scattering selection-rule breaking and the density of states in amorphous materials. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1970, 25, 222–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cazanelli, E.; Fresh, R. Raman spectra of 7Li2SO4 and 6Li2SO4. J. Chem. Phys. 1983, 79, 2615–2620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Exarhos, G.J.; Miller, P.J.; Risen, W.M. Calculation of ionic conductivity activation energies in ionic oxide glasses from spectroscopic data. Solid State Commun. 1975, 17, 29–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bates, J.B.; Dudney, N.J.; Gruzalski, G.R.; Zuhr, R.A.; Choudhury, A.; Luck, C.F. Electrical properties of amorphous lithium electrolyte thin films. Solid State Ion. 1992, 53–56, 647–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bates, J.B.; Dudney, N.J.; Neudecker, B.; Ueda, A.; Evans, C.D. Thin-film lithium and lithium-ion batteries. Solid State Ion. 2000, 135, 33–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navone, C.; Tintignac, S.; Pereira-Ramos, J.P.; Baddour-Hadjean, R.; Salot, R. Electrochemical behaviour of sputtered c-V2O5 and LiCoO2 thin films for solid state lithium microbatteries. Solid State Ion. 2011, 192, 343–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pichonat, T.; Lethiena, C.; Tiercelin, N.; Godey, S.; Pichonat, E.; Roussel, P.; Colmont, M.; Rolland, P.A. 2010. Further studies on the lithium phosphorus oxynitride solid electrolyte. Mater. Chem. Phys. 2010, 123, 231–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bunker, B.C.; Tallant, D.R.; Balfen, C.A. Structure of phosphorus oxynitride glasses. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 1987, 70, 675–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awaka, J.; Kijima, N.; Hayakawa, H.; Akimoto, J. Synthesis and structure analysis of tetragonal Li7La3Zr2O12 with the garnet-related type structure. J. Solid State Chem. 2009, 182, 2046–2052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koningstein, J.; Mortensen, O. Laser-excited phonon Raman spectrum of garnets. J. Mol. Spectrosc. 1968, 27, 343–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, T.; Wolfenstine, J.; Allen, J.L.; Johannes, M.; Huq, A.; Davida, I.N.; Sakamoto, J. Tetragonal vs. cubic phase stability in Al–free Ta doped Li7La3Zr2O12 (LLZO). J. Mater. Chem. A 2014, 2, 13431–13436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janani, N.; Deviannapoorani, C.; Dhivya, L.; Murugan, R. Influence of sintering additives on densification and Li+ conductivity of Al doped Li7La3Zr2O12 lithium garnet. RSC Adv. 2014, 4, 51228–51238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larraz, G.; Orera, A.; Sanjuan, M.L. Cubic phases of garnet-type Li7La3Zr2O12: The role of hydration. J. Mater. Chem. A 2013, 1, 11419–11428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narayanan, S.; Hitz, G.T.; Washsman, E.D.; Thangadurai, V. Effect of excess Li on the structural and electrical properties of garnet-type Li6La3Ta1.5Y0.5O12. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2015, 162, A1772–A1777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Il’ina, E.; Lyalin, E.D.; Antonov, B.D.; Pankratov, A.A.; Vovkotrub, E.G. Sol-gel synthesis of Al- and Nb-co-doped Li7La3Zr2O12 solid electrolytes. Ionics 2020, 26, 3239–3247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, C.L.; Ma, Q.; Dellen, C.; Lobe, S.; Vondahlen, F.; Windmüller, A.; Grüner, D.; Zheng, H.; Uhlenbruck, S.; Finsterbusch, M.; et al. A garnet structure-based all-solid-state Li battery without interface modification: Resolving incompatibility issues on positive electrodes. Sustain. Energy Fuels 2019, 3, 280–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delmas, C.; Nadiri, A.; Soubeyroux, J.L. The Nasicon-type titanium phosphates LiTi2(PO4)3, NaTi2(PO4)3 as electrode materials. Solid State Ion. 1998, 28–30, 419–423. [Google Scholar]

- Tarte, P.; Rulmont, A.; Merckaert-Ansay, C. Vibrational spectrum of Nasicon-like, rhombohedral orthophosphates MIMIV2(PO4)3. Spectrochim. Acta A 1986, 42, 1009–1016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bih, H.; Bih, L.; Maniun, B.; Azdouz, M.; Benmokhtar, S.; Lazor, P. Raman spectroscopic study of the phase transitions sequence in Li3Fe2(PO4)3 and Na3Fe2(PO4)3 at high temperature. J. Molecul. Struct. 2009, 936, 147–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barj, M. Relations between sublattice disorder, phase transitions and conductivity in NASICON. Solid State Ion. 1983, 9–10, 845–850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kravchenko, V.V.; Michailov, V.I.; Sigaryov, S.E. Some features of vibrational spectra of Li3M2(PO4)3 (M = Sc, Fe)- compounds near a superionic phase transition. Solid State Ion. 1992, 50, 19–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butt, G.; Sammes, N.; Tompsett, G.; Smirnova, A.; Yamamoto, O. Raman spectroscopy of superionic Ti-doped Li3Fe2(PO4)3 and LiNiPO4 structures. J. Power Sources 2004, 134, 72–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aatiq, A.; Tigha, M.R.; Benmokhtar, S. Structure, infrared and Raman spectroscopic studies of new Sr0.50SbFe(PO4)3 and SrSb0.50Fe1.50(PO4)3 Nasicon phases. J. Mater. Sci. 2012, 47, 1354–1364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Francisco, B.E.; Stoldt, C.R.; M’Peko, J.C. Lithium-ion trapping from local structural distortions in sodium super ionic conductor (NASICON) electrolytes. Chem. Mater. 2014, 26, 4741–4749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Francisco, B.E.; Stoldt, C.R.; M’Peko, J.C. Energetics of ion transport in NASICON-type electrolytes. J. Phys. Chem. C 2015, 119, 16432–16442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, K.J.; Sobha, K.C.; Kumar, S. Infrared and Raman spectroscopy studies of glasses with NASICON-type chemistry. Proc. Indian Acad. Sci. (Chem. Sci.) 2001, 113, 497–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pikl, R.; De Waal, D.; Aatiq, A.; El Jazouli, A. Vibrational spectra and factor group analysis of Li2xMn0.5−xTi2(PO4)3 (x = 0, 0.25, 0.50). Mater. Res. Bull. 1998, 33, 955–961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burba, C.M.; Frech, R. Vibrational spectroscopic study of lithium intercalation into LiTi2(PO4)3. Solid State Ion. 2006, 177, 1489–1494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkateswara Rao, A.; Veeraiah, V.; Prasada Rao, A.V.; Kishore Babu, B.; Brahmayya, M. Spectroscopic characterization and conductivity of Sn substituted LiTi2(PO4)3. Res. Chem. Intermed. 2015, 41, 4327–4337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, Y.; Pang, W. Hydrothermal synthesis of MTi2(PO4)3 (M = Li, Na, K). Mater. Res. Bull. 1990, 25, 841–844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rulmont, A.; Cahay, R.; Liegeois-Duyckaerts, M.; Tarte, P. Vibrational spectroscopy of phosphate: Some general correlations between structure and spectra. Eur. J. Solid Inorg. Chem. 1991, 28, 207–219. [Google Scholar]

- Hezel, A.; Ross, S.D. The vibrational spectra of some divalent metal pyrophosphates. Spectrochim. Acta A 1967, 23, 1583–1589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giarola, M.; Sanson, A.; Tietz, F.; Pristat, S.; Dashjav, E.; Rettenwander, D.; Redhammer, G.J.; Mariotto, G. Structure and vibrational dynamics of NASICON-type LiTi2(PO4)3. J. Phys. Chem. C 2017, 121, 3697–3706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jimenez, R.; Del Campo, A.; Calzada, M.L.; Sanz, J.; Kobylianska, S.D.; Solopan, S.O.; Belous, A.G. Lithium La0.57Li0.33TiO3 perovskite and Li1.3Al0.3Ti1.7(PO4)3 Li-NASICON supported thick films electrolytes prepared by tape casting method. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2016, 163, A1653–A1659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abhilash, K.P.; Selvin, P.C.; Nalini, B.; Jose, R.; Hui, X.; Elim, H.I.; Reddy, M.V. Correlation study on temperature dependent conductivity and line profile along the LLTO/LFP-C cross section for all solid-state lithium-ion batteries. Solid State Ion. 2019, 341, 115032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moriwake, H.; Gao, X.; Kuwabara, A.; Fisher, C.A.J.; Kimura, T.; Ikuhara, Y.H.; Kohama, K.; Tojigamori, T.; Ikuhara, Y. Domain boundaries and their influence on Li migration in solid-state electrolyte (La,Li)TiO3. J. Power Sources 2015, 276, 203–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inaguma, Y.; Nakashima, M. A rechargeable lithium-air battery using a lithium ion-conducting lanthanum lithium titanate ceramics as an electrolyte separator. J. Power Sources 2013, 228, 250–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Y.; Ji, L.; Guo, B.; Lin, Z.; Yao, Y.; Li, Y.; Alcoutlabi, M.; Qiu, Y.; Zhang, X. Preparation and electrochemical characterization of ionic-conducting lithium lanthanum titanate oxide/polyacrylonitrile submicron composite fiber-based lithium-ion battery separators. J. Power Sources 2011, 196, 436–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, S.L.; Gasparotto, G.; Ferreira-Teixeira, G.; Cebim, M.A.; Longo, E.; Zaghete, M.A. Lithium lanthanum titanate perovskite ionic conductor: Influence of europium doping on structural and optical properties. Ceram. Int. 2018, 44, 21578–21584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanjuán, M.L.; Laguna, M.A. Raman study of antiferroelectric instability in La(2−x)/3LixTiO3 (0.1 < x < 0.5) double perovskites. Phys. Rev. B 2001, 64, 174305. [Google Scholar]

- Laguna, M.A.; Sanjuán, M.L.; Várez, A.; Sanz, J. Lithium dynamics and disorder effects in the Raman spectrum of La(2−x)/3LixTiO3. Phys. Rev. B 2002, 66, 054301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanjuán, M.L.; Laguna, M.A.; Belous, A.G.; V’yunov, O.I. On the local structure and lithium dynamics of La0.5(Li,Na)0.5TiO3 ionic conductors. A Raman study. Chem. Mater. 2005, 17, 5862–5866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanjuán, M.L.; Laguna, M.A.; Várez, A.; Sanz, J. Effect of quenching on structure and antiferroelectric instability of La(2−x)/3LixTiO3 compounds: A Raman study. J. Eur. Ceram. Soc. 2004, 24, 1135–1139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mei, A.; Wang, X.-L.; Feng, Y.-C.; Zhao, S.-J.; Li, G.L.; Geng, H.-X.; Lin, Y.-H.; Nan, C.-W. Enhanced ionic transport in lithium lanthanum titanium oxide solid state electrolyte by introducing silica. Solid State Ion. 2008, 179, 2255–2259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verma, P.; Maire, P.; Novák, P. A review of the features and analyses of the solid electrolyte interphase in Li-ion batteries. Electrochim. Acta 2010, 55, 6332–6341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karapin-Springorum, L.; Sarycheva, A.; Dopilka, A.; Cha, H.; Ihsan-Ul-Haq, M.; Larson, J.M.; Kostecki, R. An infrared, Raman, and X-ray database of battery interphase components. Sci. Data 2025, 12, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hy, S.; Felix; Chen, Y.-H.; Liu, J.-y.; Rick, J.; Hwang, B.-J. In situ surface enhanced Raman spectroscopic studies of solid electrolyte interphase formation in lithium ion battery electrodes. J. Power Sources 2014, 256, 324–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ha, Y.; Tremolet de Villers, B.J.; Li, Z.; Xu, Y.; Stradins, P.; Zakutayev, A.; Burrell, A.; Han, S.-D. Probing the evolution of surface chemistry at the silicon–electrolyte Interphase via in situ surface-enhanced Raman spectroscopy. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2019, 11, 286–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gajan, A.; Lecourt, C.; Bautista, B.E.T.; Fillaud, L.; Demeaux, J.; Lucas, I.T. Solid electrolyte interphase instability in operating lithium-ion batteries unraveled by enhanced-Raman spectroscopy. ACS Energy Lett. 2021, 6, 1757–1763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmitz, R.; Müller, R.A.; Schmitz, R.W.; Schreiner, C.; Kunze, M.; Lex-Balducci, A.; Passerini, S.; Winter, M. SEI investigations on copper electrodes after lithium plating with Raman spectroscopy and mass spectrometry. J. Power Sources 2013, 233, 110–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gogoi, N.; Melin, T.; Berg, E.J. Elucidating the step-wise solid electrolyte interphase formation in lithium-ion batteries with operando Raman spectroscopy. Adv. Mater. Interfaces 2022, 9, 2200945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piernas-Muñoz, M.J.; Tornheim, A.; Trask, S.; Zhang, Z.; Bloom, I. Surface-enhanced Raman spectroscopy (SERS): A powerful technique to study the SEI layer in batteries. Chem. Commun. 2021, 57, 2253–2256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gu, Y.; You, E.-M.; Lin, J.-D.; Wang, J.-H.; Luo, S.-H.; Zhou, R.-Y.; Zhang, C.-J.; Yao, J.-L.; Li, H.-Y.; Li, G.; et al. Resolving nanostructure and chemistry of solid-electrolyte interphase on lithium anodes by depth-sensitive plasmon-enhanced Raman spectroscopy. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 3536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phung, N.T.; Feng, Y.; Poupardin, T.M.; Koo, B.M.; Henry de Villeneuce, C.; Rosso, M.; Ozanam, F. Infrared operando study of the solid-electrolyte interphase of amorphous Si electrodes for Li-ion batteries: Effects of methylation and boron doping. ACS Appl. Energy Mater. 2025, 8, 4299–4310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edström, K.; Gustafsson, T.; Thomas, J.O. The cathode electrolyte interface in the Li-ion battery. Electrochim. Acta 2004, 50, 397–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Wang, X.; Bai, Y.; Wu, C. Charactering and optimizing cathode electrolytes interface for advanced rechargeable batteries: Promises and challenges. Green Energy Environ. 2022, 7, 606–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsui, M.; Dokko, K.; Kanamura, K. Dynamic behavior of surface Film on LiCoO2 thin film electrode. J. Power Sources 2008, 177, 184–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akita, Y.; Segawa, M.; Munakata, H.; Kanamura, K. In-situ Fourier transform infrared spectroscopic analysis on dynamic behavior of electrolyte solution on LiFePO4 cathode. J. Power Sources 2013, 239, 175–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsui, M.; Dokko, K.; Kanamura, K. Surface layer formation and stripping process on LiMn2O4 and LiNi1/2Mn3/2O4 thin film electrodes. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2010, 157, A121–A129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsushita, T.; Dokko, K.; Kanamura, K. In situ FT-IR measurement for electrochemical oxidation of electrolyte with ethylene carbonate and diethyl carbonate on cathode active material used in rechargeable lithium batteries. J. Power Sources 2005, 146, 360–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsui, M.; Dokko, K.; Akita, Y.; Munakata, H.; Kanamura, K. Surface layer formation of LiCoO2 thin film electrodes in non aqueous electrolyte containing lithium bis(oxalate)borate. J. Power Sources 2012, 210, 60–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, Y.; Chen, G.; Shi, L.; Liu, H.; Zhang, D. Operando Fourier transform infrared investigation of cathode electrolyte interphase dynamic reversible evolution on Li1.2Ni0.2Mn0.6O2. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2019, 11, 45108–45117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cowan, A.J.; Hardwick, L.J. Advanced spectroelectrochemical techniques to study electrode interfaces within lithium-ion and lithium-oxygen batteries. Annu. Rev. Anal. Chem. 2019, 12, 323–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, C.; Yu, Y.; Wang, C.; Zhang, Y.; Zheng, S.; Li, J.; Maglia, F.; Jung, R.; Tian, Z.-Q.; Yang, S.-H. Surface changes of LiNixMnyCo1−x−yO2 in Li-ion batteries using in situ surface-enhanced Raman spectroscopy. J. Phys. Chem. C 2020, 124, 4024–4031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.; Zhang, X.; Ma, S.; Fan, E.; Lin, J.; Chen, R.; Wu, F.; Li, L. A new insight into capacity decay mechanism of Ni-rich layered oxide cathode for lithium-ion batteries. Nano Micro Small 2022, 18, 2204613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tremolet de Villers, B.J.; Bak, S.-M.; Yang, J.; Han, S.-D. In situ ATR-FTIR study of the cathode–electrolyte interphase: Electrolyte solution structure, transition metal redox, and surface layer evolution. Batter. Supercaps 2021, 4, 778–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Gao, H.; Wang, Z.; Gao, H.; Che, L.; Xiao, K.; Dong, A. In situ Raman spectroscopy reveals structural evolution and key intermediates on Cu-based catalysts for electrochemical CO2 reduction. Nanomaterials 2025, 15, 1517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laurenti, B.; Gonzalez-Rosillo, J.C.; Chiabrera, F.; Fiocco, A.; Freitas, F.M.; Chaigneau, M.; Morata, A.; Tarancon, A. Unraveling nanoscale interfacial kinetics in battery cathodes through operando tip-enhanced Raman spectroscopy. EES Batteries 2025, 1, 1147–1157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Cation | rM-O (Å) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 4 | 6 | 8 | 10 | 12 | |

| Li | 1.99 | 2.16 | 2.32 | - | - |

| Na | 2.39 | 2.42 | 2.58 | - | - |

| K | 2.77 | 2.78 | 2.91 | 2.99 | 3.04 |

| Type of Structure | Space Group | Raman Activity |

|---|---|---|

| Layered hexagonal rock-salt | A1g + Eg | |

| Layered monoclinic rock-salt | –C2/m | 2Ag + 2Bg |

| Normal cubic spinel | –Fd3m | A1g + Eg + 3F2g |

| Modified cubic spinel | –Fd3m | A1g + Eg + 3F2g |

| Normal tetragonal spinel | –I41/amd | 2A1g + B1g + 3B2g + 4Eg |

| Inverse cubic spinel | – | A1g + Eg + 3F2g |

| Ordered cubic spinel (I) | O7–P4132 | 6A1 + 14E + 20F2 |

| Ordered cubic spinel (II) | –P4122 | 9A1 + 10B1 + 11B2 + 21E |

| Ordered cubic spinel (III) | – | 3A1 + 3E + 6F2 |

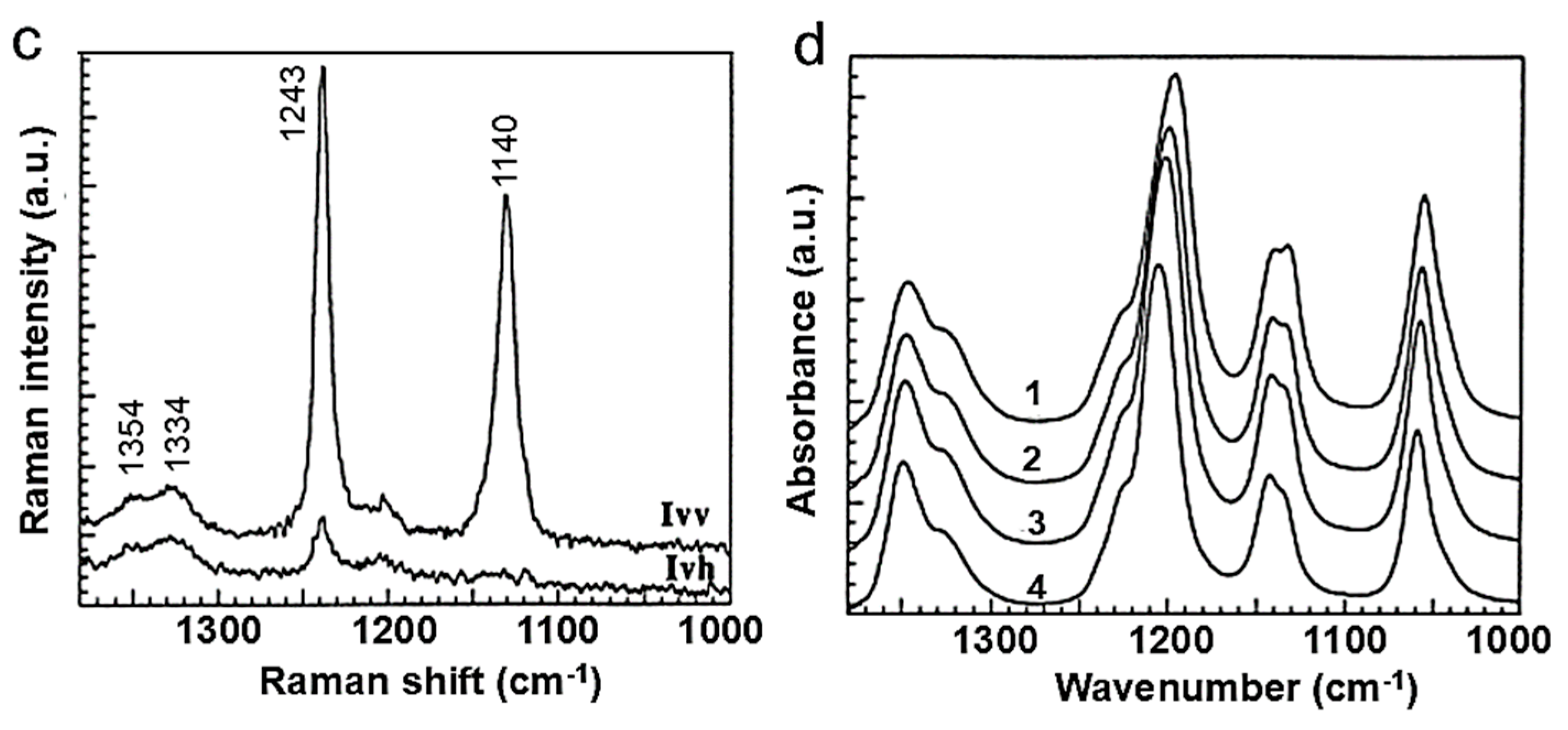

| Vibration | (H2O)266/LiFTSI at 25 °C | P(EO)15/LiTFSI at 80 °C | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| IR | Raman | IR | Raman | |

| νa(SO2) | 1354, 1333 | 1354, 1334 | 1349, 1325 | 1350, 1330 |

| νs(SO2) | 1136 | 1140 | 1143–1135 | 1131 |

| νa(CF3) | 1193 | - | 1206 | - |

| νs(CF3) | - | 1243 | - | 1239 |

| νa(SNS) | 1060 | - | 1055 | - |

| Frequency (cm−1) | Assignment | |

|---|---|---|

| P2O5-Li2O | LiPON | |

| 467 | 465 | Li(2)-O stretching |

| 510, 586, 623, 944 | 497, 946 | P-O bond in orthophosphate PO43− |

| 601, 625 | P−N bond | |

| 802 | P−N=P bond | |

| 1022 | 1019 | P-O bond in pyrophosphate P2O74− |

| 1146 | P-O bond in metaphosphate (PO3−)n | |

| Raman Shift (cm−1) | Symmetry | Displacements |

|---|---|---|

| 140 | Eg | Ti in-plane |

| 230 | Eg | O(3) in-plane |

| 315 | A1g | Ti c-axis |

| 450 | A1g (forbidden) | O(1,2) c-axis |

| 525 | Eg | O(3) in-plane |

| 550, 580 | A1g (allowed) | O(3) c-axis |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Julien, C.M.; Mauger, A. Raman and Infrared Spectroscopy of Materials for Lithium-Ion Batteries. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 11879. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262411879

Julien CM, Mauger A. Raman and Infrared Spectroscopy of Materials for Lithium-Ion Batteries. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2025; 26(24):11879. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262411879

Chicago/Turabian StyleJulien, Christian M., and Alain Mauger. 2025. "Raman and Infrared Spectroscopy of Materials for Lithium-Ion Batteries" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 26, no. 24: 11879. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262411879

APA StyleJulien, C. M., & Mauger, A. (2025). Raman and Infrared Spectroscopy of Materials for Lithium-Ion Batteries. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 26(24), 11879. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262411879