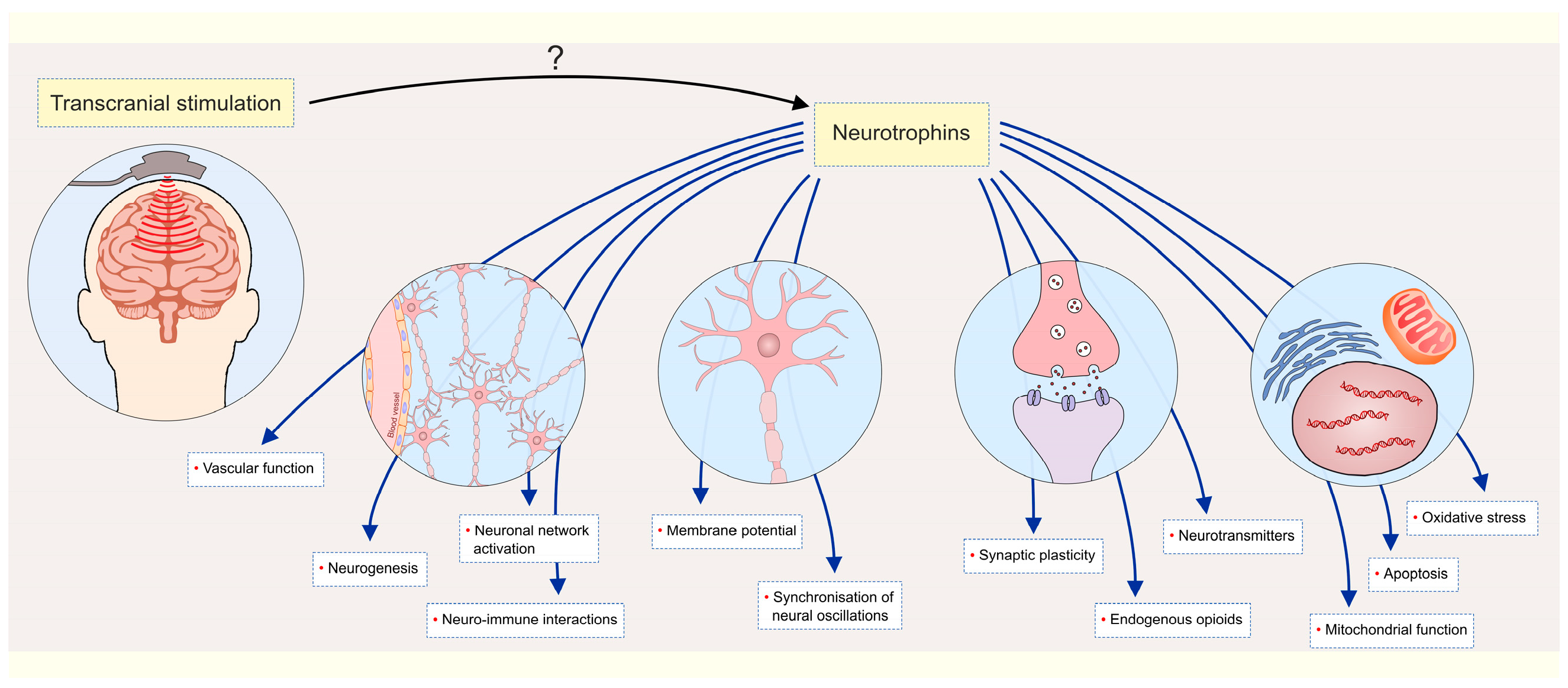

Transcranial Stimulation Methods in the Treatment of MDD Patients—The Role of the Neurotrophin System

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Transcranial Stimulation Methods in the Treatment of MDD Patients

1.2. Neurotrophin System and MDD

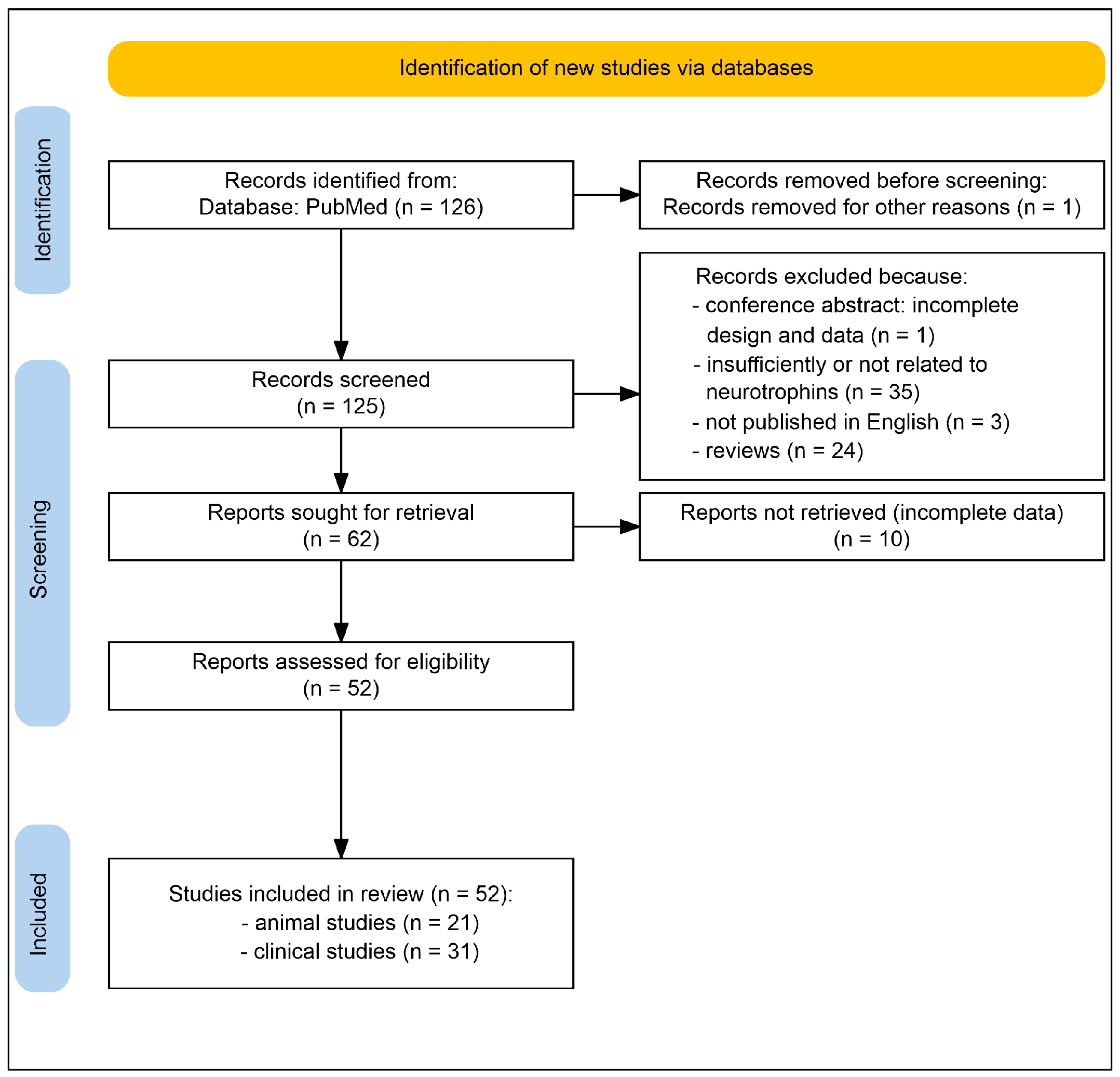

2. Methods

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. An Overview of Non-Invasive Methods of Transcranial Stimulation Impact on the Neurotrophin System Elements in the Treatment of Depression

3.1.1. Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation

| (A) | |||||||

| Applied Methodology | Diagnosis | Neurotrophin System Alterations | Clinical Outcome | Ref. | |||

| Type | Specific Features | Neurotrophins | Neurotrophin Receptors | Downstream Mechanisms | |||

| rTMS (10 Hz, intensity 80% of the resting exercise threshold, a cyclic treatment approach, duration—5 s with an interval of 15 s, the total treatment time—15 min, once per day) 5 days a week, for 4 weeks) | MDD (n = 130) | Non-suicidal self-injury behavior + sertraline | BDNF ↑ NGF ↑ | - | Norepinephrine ↑ Dopamine ↑ 5-hydroxytryptamine ↑ Neuroinflammation ↓ | Positive | [58] |

| rTMS (10 Hz, total of 37.5 min, 4 s of stimulation time and 26 s of latent time, 20 sessions, every weekday for a month) | MDD (n = 51) | - | BDNF ↑ GDNF ↑ | - | - | Positive | [59] |

| rTMS (10 Hz for 3 weeks—5 sessions per week) | MDD (n = 6) | Geriatric depression | BDNF n.c. NGF n.c. | - | - | Initial—positive Follow up—n.c. | [60] |

| rTMS (10 Hz, intensity of 120% motor threshold, 25 trains of 8 s, and an inter-train interval of 26 s, 5 days per week, for 4 weeks) | Mild to moderate DD (n = 100) | + agomelatine | BDNF ↑ | - | Norepinephrine ↑ | Positive | [61] |

| rTMS (10 Hz, the motor threshold was 80% to 110%, stimulation for 5 s, interval of 25 s, once a day for 20 min, 5 times per week, for 8 weeks) | MDD (n = 120) | Middle-aged and elderly + escitalopram | BDNF ↑ | - | - | Positive | [62] |

| rTMS (20 Hz, duration of 2 s, 20 times at 30 s intervals, 100% of the motor threshold, 5 days a week for 4 weeks) | MDD (n = 66) | Treatment-resistant depression | BDNF ↑ GDNF ↑ | - | - | Positive | [63] |

| rTMS (iTBS and cTBS), for 2 weeks | MDD (n = 48) | Treatment-resistant depression | BDNF ↑ NGF n.c. | - | - | Positive | [64] |

| rTMS (iTBS), for 3–6 weeks | MDD (n = 25) | Treatment-resistant depression | BDNF ↑ | - | - | [65] | |

| LFMS (20 min per session, 5 sessions per week, for 6 weeks): RAS and RDS | MDD (n = 29) | - | BDNF ↑ | - | - | Positive | [66] |

| neuronavigation-guided rTMS (10 Hz, 5 s duration, 15 s inter-train intervals, 6000 pulses per session, 100% of the MT) for 7 days (120 trains) | MDD (n = 59) | Treatment-naive depressive patients with suicidal ideation | BDNF ↑ | TrkB ↓ | - | Positive | [67] |

| Arrows (↑ or ↓) indicate p < 0.05; n.c. indicates p > 0.05; n indicates the number of subjects. | |||||||

| (B) | |||||||

| rTMS (10-Hz for 3 weeks) | Depression in rats | CUMS | - | - | FGF2/FGFR1/p-ERK ↑ | Positive | [68] |

| rTMS (15 and 25 Hz) for 4 weeks | Depression in mice | CUMS | BDNF ↑ | TrkB ↑ | p11/BDNF/Homer1a ↑ | Positive | [69] |

| rTMS (10 Hz, 5 s per train, 20 trains per day) for 28 days | Depression in mice | CUMS + fluoxetine | BDNF ↑ | TrkB ↑ | BDNF/TrkB ↑ | Positive | [70] |

iTBS for 2 weeks:

| Depression in rats | Poststroke + CUMS | BDNF ↑ | - | cAMP/PKA/CREB ↑ | Positive | [71] |

rTMS (10 Hz, 3 min) for 4 weeks:

| Depression in mice | Olfactory bulbectomy | BDNF ↑ | - | Cell proliferation ↑ Neurogenesis ↑ | Positive | [72] |

| Arrows (↑ or ↓) indicate p < 0.05. | |||||||

3.1.2. Transcranial Current Stimulation

| Applied Methodology | Diagnosis | Neurotrophin System Alterations | Clinical Outcome | Ref. | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Type | Specific Features | Neurotrophins | Neurotrophin Receptors | Downstream Mechanisms | |||

| CLINICAL TRIALS | |||||||

| tDCS—high current (2.5 mA, 30 min) and low current (0.034 mA, two 60 s current ramps up to 1 and 0.5 mA) in 20 sessions for 4 weeks | Unipolar and bipolar depression (n = 130) | + paroxetine | - | - | - | Positive | [76] |

| tDCS (left DLPFC, 0.5 mA, for 10 days) as 30 and 20 min sessions | Moderate depression (n = 69) | + sertraline | BDNF n.c. | - | - | Positive | [77] |

| tDCS (2 mA for 30 min, 22 sessions—15 in the first 3 weeks and 7 from week 3 to 10, once a week) | MDD (treatment-resistant, chronic, and recurrent) (n = 236) | + escitalopram | BDNF n.c. GDNF n.c. NGF n.c. | - | Neuroinflammation ↓ | Positive | [78] |

| tDCS (2 mA, 30 min/d, 10 days, and another 2 times, one at week 4 and at week 6) | Moderate to severe bipolar depression (n = 52) | - | BDNF n.c. GDNF n.c. NGF n.c. | - | Neuroinflammation ↓ | Positive | [79] |

| ANIMAL MODEL | |||||||

| tDCS (prefrontal, 50 μA anodal tDCS (13.33 A/m2) 15 min): acute (single) chronic (14 days) | Depression in adolescent rats | Olfactory bulbectomy | BDNF ↑ | - | 5-hydroxytryptamine downstream mechanisms ↑ | Positive | [80] |

3.1.3. Electroconvulsive Therapy

| (A) | |||||||

| Applied Methodology | Diagnosis | Neurotrophin System Alterations | Clinical Outcome | Ref. | |||

| Type | Specific Features | Neurotrophins | Neurotrophin Receptors | Downstream Mechanisms | |||

| ECT (hand-held electrodes) | MDD (n = 111) | BDNF n.c. | - | - | Positive | [84] | |

| ECT (bilateral electrode placement) | MDD (n = 30) | BDNF n.c. | - | - | Positive | [85] | |

| ECT (unilateral electrode position) | MDD (n = 88) | Late-life patients | BDNF n.c. | - | Hippocampal volume ↑ | Positive | [86] |

| ECT (unilateral/bilateral electrode position) | MDD (n = 61) | Late-life patients | BDNF n.c. | - | Hippocampal volume ↑ | Positive | [88] |

| ECT (bilateral electrode position) | MDD (n = 35) | BDNF n.c. | - | - | Positive | [89] | |

| ECT (unilateral electrode position) | MDD (n = 31) | Unipolar and bipolar | BDNF ↑ (when low baseline) | - | - | Positive | [90] |

| ECT | MDD (n = 94) | BDNF n.c. | - | - | Positive | [91] | |

| ECT (bilateral electrode position) | MDD (n = 74) | BDNF n.c. | - | - | Positive | [92] | |

| ECT (unilateral electrode position) | MDD (n = 24) | pBDNF n.c. sBDNF ↑ | - | - | Positive | [93] | |

| ECT (unilateral electrode position) | MDD (n = 13) | sBDNF ↑ | - | - | Positive | [94] | |

| ECT (unilateral/bilateral electrode position) | MDD (n = 9) | BDNF (in CSF) ↑ sBDNF n.c. | - | - | Positive | [95] | |

| ECT (unilateral/bilateral electrode position) | MDD (n = 36) | sBDNF ↑ | - | - | Positive | [96] | |

| ECT | MDD (n = 60) | + aerobic exercise | BDNF ↑ | - | - | Positive | [97] |

| ECT (unilateral electrode position) | MDD (n = 99) | Late-life patients | BDNF ↑ (n.s.) | - | Neuroinflammation ↓ TNF-α/BDNF ratio ↓ | Positive | [98] |

| ECT (bitemporal electrode position) | MDD (n = 19) | Unipolar and bipolar | BDNF ↑ | - | BDNF/ERK1/CREB ↑ | Positive | [99] |

| ECT (bitemporal electrode position) | MDD (n = 75) | BDNF ↑ | - | Neurogenesis ↑ | Positive | [100] | |

| ECT (bitemporal electrode position) | MDD (n = 9) | BDNF ↑ | - | Neuroinflammation ↓ | Positive | [101] | |

| Arrows (↑ or ↓) indicate p < 0.05; n.c. indicates p > 0.05; n indicates the number of subjects. | |||||||

| (B) | |||||||

| ECS (corneal electrode, 100 pulse/s, 0.3 ms, 1 s shock, and 50 mA) | CUMS—adult mice | BDNF ↑ | - | Neurogenesis ↑ | Positive | [102] | |

| ECS | CUMS—rats | BDNF ↑ | - | Ferroptosis ↓ | Positive | [103] | |

| ECS (7 sessions—100 pulse/s, 3 ms, 1 s shock duration, 50 mA, for 15 days) | BDNF disrupts production—mice | Bdnf-e1 mice | - | - | Neuroplasticity ↑ | Positive | [104] |

| ECS (ear clip electrodes 55 to 70 mA in 0.5 s, 100 Hz/d, for 10 days) | Flinders Sensitive and Resistant Line rats | Prone to depressive-like behavior | BDNF ↑ | - | Neurogenesis ↑ Neuroplasticity ↑ | Positive | [105] |

| ECS (40 mA on the first 5 days and 50 mA on the following 5 days for 0.5 s, 50 Hz) | Rats | Naive | pro-BDNF n.c. BDNF ↑ | - | BDNF/TrkB ↑ | - | [106] |

| Arrows (↑ or ↓) indicate p < 0.05. | |||||||

3.1.4. Transcranial Photobiomodulation

| Applied Methodology | Diagnosis | Neurotrophin System Alterations | Outcome | Ref. | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Type | Specific Features | Neurotrophins | Neurotrophin Receptors | Downstream Mechanisms | |||

| tPBM (810 nm, 8 J/cm2 fluence, 10 Hz pulsed wave mode) for 2 weeks | Noise-induced depression in mice | + enriched environment | BDNF ↑ | TrkB ↑ | BDNF/TrkB/CREB ↑ | Positive | [118] |

| TUS (15 min stimulation of the prelimbic cortex every day) for 2 weeks | Restraint stress-induced depression in rats | BDNF ↑ | - | - | Positive | [119] | |

| TUS (dorsal lateral nucleus 30 min/d) for 3 weeks | Corticosterone-induced depression in mice | BDNF n.c. | - | 5-hydroxytryptamine ↑ | Positive | [120] | |

3.1.5. Transcranial Ultrasound Stimulation

3.2. An Overview of Invasive Methods of Transcranial Stimulation Impact on the Neurotrophin System Elements in the Treatment of MDD

3.2.1. Deep Brain Stimulation

3.2.2. Vagus Nerve Stimulation

4. Conclusions

5. Future Directions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| MDD | Major Depressive Disorder |

| TMS | Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation |

| tDCS | transcranial Direct Current Stimulation |

| tRNS | transcranial Random Noise Stimulation |

| tPBM | transcranial Photobiomodulation |

| TUS | Transcranial Ultrasound Stimulation |

| FUS | Focused Ultrasound Stimulation |

| TNS | Trigeminal Nerve Stimulation |

| ECT | Electroconvulsive Therapy |

| ECS | Electroconvulsive Stimulation |

| DBS | Deep Brain Stimulation |

| VNS | Vagus Nerve Stimulation |

| BDNF | Brain-Derived Neurotrophic Factor |

| NT-3 | Neurotrophin-3 |

| NGF | Nerve Growth Factor |

| MADRS | Montgomery–Asberg Depression Rating Scale |

| CGI | Clinical Global Impression Scale |

| HDRS | Hamilton Depression Rating Scale |

| PFC | prefrontal cortex |

| CUMS | Chronic Unpredictable Mild Stress |

| TRD | Treatment-Resistant Depression |

References

- Cui, L.; Li, S.; Wang, S.; Wu, X.; Liu, Y.; Yu, W.; Wang, Y.; Tang, Y.; Xia, M.; Li, B. Major depressive disorder: Hypothesis, mechanism, prevention and treatment. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2024, 9, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vasudeva, S.; Wong, S.; Le, G.H.; Dri, C.E.; Teopiz, K.M.; Ho, R.; Rhee, T.G.; McIntyre, R.S. Efficacy and safety profiles of FDA-approved dual orexin receptor antagonists in depression: A systematic review of pre-clinical and clinical studies. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2025, 191, 752–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zamfirache, F.; Dumitru, C.; Trandafir, D.-M.; Bratu, A.; Radu, B.M. A Review of Transcranial Electrical and Magnetic Stimulation Usefulness in Major Depression Disorder—Lessons from Animal Models and Patient Studies. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 4020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gebodh, N.; Esmaeilpour, Z.; Adair, D.; Schestattsky, P.; Fregni, F.; Bikson, M. Transcranial Direct Current Stimulation Among Technologies for Low-Intensity Transcranial Electrical Stimulation: Classification, History, and Terminology. In Practical Guide to Transcranial Direct Current Stimulation: Principles, Procedures and Applications; Knotkova, H., Nitsche, M.A., Bikson, M., Woods, A.J., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 3–43. [Google Scholar]

- Correia, A.S.; Cardoso, A.; Vale, N. BDNF Unveiled: Exploring Its Role in Major Depression Disorder Serotonergic Imbalance and Associated Stress Conditions. Pharmaceutics 2023, 15, 2081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaiswal, A.; Shreekantiah, U.; Goyal, N. Nerve Growth Factor in Psychiatric Disorders: A Scoping Review. Indian J. Psychol. Med. 2023, 45, 555–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shatri, H.; Pranandi, M.; Ardani, Y.; Firmansyah, I.; Faisal, E.; Putranto, R. The role of Neurotrophin 3 (NT-3) on neural plasticity in depression: A literature review. Intisari Sains Medis 2023, 14, 1103–1108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krasner, H.; Ong, C.V.; Hewitt, P.; Vida, T.A. From Stress to Synapse: The Neuronal Atrophy Pathway to Mood Dysregulation. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 3219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levy, M.J.F.; Boulle, F.; Steinbusch, H.W.; van den Hove, D.L.A.; Kenis, G.; Lanfumey, L. Neurotrophic factors and neuroplasticity pathways in the pathophysiology and treatment of depression. Psychopharmacology 2018, 235, 2195–2220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amidfar, M.; Réus, G.Z.; de Moura, A.B.; Quevedo, J.; Kim, Y.K. The Role of Neurotrophic Factors in Pathophysiology of Major Depressive Disorder. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2021, 1305, 257–272. [Google Scholar]

- Dahiya, S.; Sharma, P.; Sharma, B.; Saroj, P.; Kharkwal, H.; Sharma, N. The Intricate Relationship of Trk Receptors in Brain Diseases and Disorders. Mol. Neurobiol. 2025, 62, 14883–14922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitrovic, M.; Selakovic, D.; Jovicic, N.; Ljujic, B.; Rosic, G. BDNF/proBDNF Interplay in the Mediation of Neuronal Apoptotic Mechanisms in Neurodegenerative Diseases. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 4926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Almeida, F.B.; Barros, H.M.T.; Pinna, G. Neurosteroids and Neurotrophic Factors: What Is Their Promise as Biomarkers for Major Depression and PTSD? Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 1758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Shi, J.; Li, J.; Liu, R.; Yu, Y.; Xu, Y. Role of brain-derived neurotrophic factor in the molecular neurobiology of major depressive disorder. Transl. Perioper. Pain. Med. 2017, 4, 20–30. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, T.; Nie, Z.; Shu, H.; Kuang, Y.; Chen, X.; Cheng, J.; Yu, S.; Liu, H. The Role of BDNF on Neural Plasticity in Depression. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 2020, 14, 82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Hao, M.; Yu, H.; Tian, Y.; Yang, C.; Fan, H.; Zhao, X.; Geng, F.; Mo, D.; Xia, L.; et al. The associations of brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) levels with psychopathology and lipid metabolism parameters in adolescents with major depressive disorder. Eur. Arch. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavaleri, D.; Moretti, F.; Bartoccetti, A.; Mauro, S.; Crocamo, C.; Carrà, G.; Bartoli, F. The role of BDNF in major depressive disorder, related clinical features, and antidepressant treatment: Insight from meta-analyses. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2023, 149, 105159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Ma, J.; Zhang, W.X.; Cao, Y.L.; Lei, C. Serum Brain-derived Neurotrophic Factor Levels as a Biomarker of Treatment Response in Patients With Depression: Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Actas Esp. Psiquiatr. 2025, 53, 857–867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Memon, A.A.; Hedelius, A.; Grundberg, A.; Sundquist, J.; Sundquist, K. Elevated plasma brain-derived neurotrophic factor as a potential risk biomarker for major depressive disorder in middle-aged women: A nested case-control study. J. Affect. Disord. 2026, 392, 120202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gelle, T.; Samey, R.A.; Plansont, B.; Bessette, B.; Jauberteau-Marchan, M.O.; Lalloué, F.; Girard, M. BDNF and pro-BDNF in serum and exosomes in major depression: Evolution after antidepressant treatment. Prog. Neuro-Psychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry 2021, 109, 110229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Gao, C.; Li, Z.; Jiang, T.; Liang, Y.; Jiang, T.; Yu, C.; Yan, S.; Li, P.; Zhou, L. The changes of tPA/PAI-1 system are associated with the ratio of BDNF/proBDNF in major depressive disorder and SSRIs antidepressant treatment. Neuroscience 2024, 559, 220–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshimura, R.; Okamoto, N.; Chibaatar, E.; Natsuyama, T.; Ikenouchi, A. The Serum Brain-Derived Neurotrophic Factor Increases in Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitor Responders Patients with First-Episode, Drug-Naïve Major Depression. Biomedicines 2023, 11, 584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madsen, C.A.; Navarro, M.L.; Elfving, B.; Kessing, L.V.; Castrén, E.; Mikkelsen, J.D.; Knudsen, G.M. The effect of antidepressant treatment on blood BDNF levels in depressed patients: A review and methodological recommendations for assessment of BDNF in blood. Eur. Neuro-Psychopharmacol. 2024, 87, 35–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zwolińska, W.; Skibinska, M.; Słopień, A.; Dmitrzak-Węglarz, M. ProBDNF as an Indicator of Improvement among Women with Depressive Episodes. Metabolites 2022, 12, 358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, L.Y.; Kelliny, S.; Liu, L.C.; Al-Hawwas, M.; Zhou, X.F.; Bobrovskaya, L. Peripheral ProBDNF Delivered by an AAV Vector to the Muscle Triggers Depression-Like Behaviours in Mice. Neurotox. Res. 2020, 38, 626–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Philpotts, R.; Gillan, N.; Barrow, M.; Seidler, K. Stress-induced alterations in hippocampal BDNF in the pathophysiology of major depressive disorder and the antidepressant effect of saffron. J. Affect. Disord. Rep. 2023, 14, 100630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.R.; Zhang, X.Y.; Liu, Y.; Du, J.Y.; Liang, R.; Yu, M.; Zhang, F.Q.; Mu, X.F.; Li, F.; Zhou, L.; et al. Antidepressant Drugs Correct the Imbalance Between proBDNF/p75NTR/Sortilin and Mature BDNF/TrkB in the Brain of Mice with Chronic Stress. Neurotox. Res. 2020, 37, 171–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.R.; Liang, R.; Liu, Y.; Meng, F.J.; Zhou, F.; Zhang, X.Y.; Ning, L.; Wang, Z.Q.; Liu, S.; Zhou, X.F. Upregulation of proBDNF/p75NTR signaling in immune cells and its correlation with inflammatory markers in patients with major depression. FASEB J. 2024, 38, e23312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Zhao, M.; Jiang, C.; Zhao, H.; Wu, C.; Li, Y.; Zhang, S.; Xu, P.; Mou, T.; Xu, Y.; et al. Elevated Plasma Levels of Mature Brain-Derived Neurotrophic Factor in Major Depressive Disorder Patients with Higher Suicidal Ideation. Brain Sci. 2023, 13, 1223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, Y. Corticosterone-Mediated BDNF Changes and Their Effects on Adult Neurogenesis in Depression. Sci. Technol. Eng. Chem. Environ. Prot. 2024, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herhaus, B.; Heni, M.; Bloch, W.; Petrowski, K. Dynamic interplay of cortisol and BDNF in males under acute and chronic psychosocial stress—A randomized controlled study. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2024, 170, 107192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Toader, C.; Serban, M.; Munteanu, O.; Covache-Busuioc, R.A.; Enyedi, M.; Ciurea, A.V.; Tataru, C.P. From Synaptic Plasticity to Neurodegeneration: BDNF as a Transformative Target in Medicine. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 4271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, D.; Lee, G.; Lee, W.G.; Kim, B.; Lee, Y.; Kim, J.W. The therapeutic potential of psilocybin beyond psychedelia through shared mechanisms with ketamine. Mol. Psychiatry 2025, 30, 4910–4927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borsellino, P.; Krider, R.I.; Chea, D.; Grinnell, R.; Vida, T.A. Ketamine and the Disinhibition Hypothesis: Neurotrophic Factor-Mediated Treatment of Depression. Pharmaceuticals 2023, 16, 742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kao, C.F.; Liu, Y.L.; Yu, Y.W.; Yang, A.C.; Lin, E.; Kuo, P.H.; Tsai, S.J. Gene-based analysis of genes related to neurotrophic pathway suggests association of BDNF and VEGFA with antidepressant treatment-response in depressed patients. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 6983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Li, O.; Li, N.; Sha, Z.; Zhao, Z.; Xu, J. Association between the BDNF Val66Met polymorphism and major depressive disorder: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Front. Psychiatry 2023, 14, 1143833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramawat, R.B.; Quraishi, R.; Deep, R.; Kumar, R.; Mishra, A.K.; Jain, R. An Observational Case-control Study for BDNF Val66Met Polymorphism and Serum BDNF in Patients with Major Depressive Disorder (MDD). Indian J. Psychol. Med. 2024, 02537176241280050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hartig, J.; Nemeş, B. BDNF-related mutations in major depressive disorder: A systematic review. Acta Neuropsychiatr. 2023, 35, 5–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, M.; Zeng, D.; Tan, W.; Chen, X.; Bai, S.; Wu, Q.; Chen, Y.; Wei, Z.; Mei, Y.; Zeng, Y. Brain region-specific roles of brain-derived neurotrophic factor in social stress-induced depressive-like behavior. Neural Regen. Res. 2025, 20, 159–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von Bohlen Und Halbach, O.; von Bohlen Und Halbach, V. BDNF effects on dendritic spine morphology and hippocampal function. Cell Tissue Res. 2018, 373, 729–741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tartt, A.N.; Mariani, M.B.; Hen, R.; Mann, J.J.; Boldrini, M. Dysregulation of adult hippocampal neuroplasticity in major depression: Pathogenesis and therapeutic implications. Mol. Psychiatry 2022, 27, 2689–2699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.H.; Lee, J.; Shin, J.; Yoo, J.H.; Kim, J.-W. 4.37 The Relationship Between Serum Brain-Derived Neurotrophic Factor and Hippocampal Resting-State Functional Connectivity in Adolescents With MDD. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2023, 62, S244–S245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, J.; Ma, L.; Jiao, X.; Dong, W.; Lin, J.; Qiu, Y.; Wu, W.; Liu, Q.; Chen, C.; Huang, H.; et al. Impaired synaptic plasticity and decreased excitability of hippocampal glutamatergic neurons mediated by BDNF downregulation contribute to cognitive dysfunction in mice induced by repeated neonatal exposure to ketamine. CNS Neurosci. Ther. 2024, 30, e14604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jialin, A.; Zhang, H.G.; Wang, X.H.; Wang, J.F.; Zhao, X.Y.; Wang, C.; Cao, M.N.; Li, X.J.; Li, Y.; Cao, L.L.; et al. Cortical activation patterns in generalized anxiety and major depressive disorders measured by multi-channel near-infrared spectroscopy. J. Affect. Disord. 2025, 379, 549–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.; Zhao, H.L.; Kurban, N.; Qin, Y.; Chen, X.; Cui, S.Y.; Zhang, Y.H. Reduction of BDNF Levels and Biphasic Changes in Glutamate Release in the Prefrontal Cortex Correlate with Susceptibility to Chronic Stress-Induced Anhedonia. eNeuro 2023, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, S.H.; Yu, Y.H.; He, A.; Ou, C.Y.; Shyu, B.C.; Huang, A.C.W. BDNF Protein and BDNF mRNA Expression of the Medial Prefrontal Cortex, Amygdala, and Hippocampus during Situational Reminder in the PTSD Animal Model. Behav. Neurol. 2021, 2021, 6657716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Šimić, G.; Tkalčić, M.; Vukić, V.; Mulc, D.; Španić, E.; Šagud, M.; Olucha-Bordonau, F.E.; Vukšić, M.; Hof, P.R. Understanding Emotions: Origins and Roles of the Amygdala. Biomolecules 2021, 11, 823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorenzetti, V.; Costafreda, S.G.; Rimmer, R.M.; Rasenick, M.M.; Marangell, L.B.; Fu, C.H.Y. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor association with amygdala response in major depressive disorder. J. Affect. Disord. 2020, 267, 103–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; He, Y.; Fan, H.; Wang, Z.; Huang, J.; Wen, G.; Wang, X.; Xie, Q.; Qiu, P. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor upregulates synaptic GluA1 in the amygdala to promote depression in response to psychological stress. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2021, 192, 114740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salsabil, L.; Shahriar, M.; Islam, S.M.A.; Bhuiyan, M.A.; Qusar, M.S.; Islam, M.R. Higher serum nerve growth factor levels are associated with major depressive disorder pathophysiology: A case-control study. J. Int. Med. Res. 2023, 51, 3000605231166222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maes, M.; Rachayon, M.; Jirakran, K.; Sodsai, P.; Sughondhabirom, A. Lower Nerve Growth Factor Levels in Major Depression and Suicidal Behaviors: Effects of Adverse Childhood Experiences and Recurrence of Illness. Brain Sci. 2023, 13, 1090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheldrick, A.; Camara, S.; Ilieva, M.; Riederer, P.; Michel, T.M. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) and neurotrophin 3 (NT3) levels in post-mortem brain tissue from patients with depression compared to healthy individuals—A proof of concept study. Eur. Psychiatry 2017, 46, 65–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Miranda, A.S.; de Barros, J.; Teixeira, A.L. Is neurotrophin-3 (NT-3): A potential therapeutic target for depression and anxiety? Expert Opin. Ther. Targets 2020, 24, 1225–1238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasakura, N.; Murata, Y.; Suzuki, K.; Segi-Nishida, E. Role of endogenous NT-3 in neuronal activity and neurogenesis in the hippocampal dentate gyrus. Neurosci. Res. 2025, 218, 104923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liberati, A.; Altman, D.G.; Tetzlaff, J.; Mulrow, C.; Gøtzsche, P.C.; Ioannidis, J.P.; Clarke, M.; Devereaux, P.J.; Kleijnen, J.; Moher, D. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: Explanation and elaboration. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2009, 62, e1–e34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- George, M.S.; Wassermann, E.M.; Williams, W.A.; Callahan, A.; Ketter, T.A.; Basser, P.; Hallett, M.; Post, R.M. Daily repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS) improves mood in depression. NeuroReport 1995, 6, 1853–1856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pascual-Leone, A.; Rubio, B.; Pallardó, F.; Catalá, M.D. Rapid-rate transcranial magnetic stimulation of left dorsolateral prefrontal cortex in drug-resistant depression. Lancet 1996, 348, 233–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, J.; Guan, J.; Xiong, J.; Wang, F. Effects of Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation Combined with Sertraline on Cognitive Level, Inflammatory Response and Neurological Function in Depressive Disorder Patients with Non-suicidal Self-injury Behavior. Actas Esp. Psiquiatr. 2024, 52, 28–36. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ozkan, B.N.; Bozali, K.; Boylu, M.E.; Velioglu, H.A.; Aktas, S.; Kirpinar, I.; Guler, E.M. Altered blood parameters in “major depression” patients receiving repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS) therapy: A randomized case-control study. Transl. Psychiatry 2024, 14, 264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nicoletti, V.G.; Fisicaro, F.; Aguglia, E.; Bella, R.; Calcagno, D.; Cantone, M.; Concerto, C.; Ferri, R.; Mineo, L.; Pennisi, G.; et al. Challenging the Pleiotropic Effects of Repetitive Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation in Geriatric Depression: A Multimodal Case Series Study. Biomedicines 2023, 11, 958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pu, Z.; Hou, Q.; Yan, H.; Lin, Y.; Guo, Z. Efficacy of repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation and agomelatine on sleep quality and biomarkers of adult patients with mild to moderate depressive disorder. J. Affect. Disord. 2023, 323, 55–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Fan, X.; Zhang, L.; Liu, X.; Ji, Z. Repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation in the treatment of middle-aged and elderly major depressive disorder: A randomized controlled trial. Medicine 2023, 102, e34841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Demiroz, D.; Cicek, I.E.; Kurku, H.; Eren, I. Neurotrophic Factor Levels and Cognitive Functions before and after the Repetitive Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation in Treatment Resistant Depression. J. Coll. Physicians Surg. Pak. 2022, 32, 335–339. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Valiuliene, G.; Valiulis, V.; Zentelyte, A.; Dapsys, K.; Germanavicius, A.; Navakauskiene, R. Anti-neuroinflammatory microRNA-146a-5p as a potential biomarker for neuronavigation-guided rTMS therapy success in medication resistant depression disorder. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2023, 166, 115313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valiuliene, G.; Valiulis, V.; Dapsys, K.; Vitkeviciene, A.; Gerulskis, G.; Navakauskiene, R.; Germanavicius, A. Brain stimulation effects on serum BDNF, VEGF, and TNFα in treatment-resistant psychiatric disorders. Eur. J. Neurosci. 2021, 53, 3791–3802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, L.; Correll, C.U.; Feng, L.; Xiang, Y.T.; Feng, Y.; Hu, C.Q.; Li, R.; Wang, G. Rhythmic low-field magnetic stimulation may improve depression by increasing brain-derived neurotrophic factor. CNS Spectr. 2019, 24, 313–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, F.; Mou, T.; Shao, J.; Chen, H.; Tao, S.; Wang, L.; Jiang, C.; Zhao, M.; Wang, Z.; Hu, S.; et al. Effects of neuronavigation-guided rTMS on serum BDNF, TrkB and VGF levels in depressive patients with suicidal ideation. J. Affect. Disord. 2023, 323, 617–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, J.; Zhang, F.; Niu, L.; Wang, X.; Lu, X.; Ma, C.; Zhang, C.; Song, J.; Zhang, Z. High-frequency repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation mitigates depression-like behaviors in CUMS-induced rats via FGF2/FGFR1/p-ERK signaling pathway. Brain Res. Bull. 2022, 183, 94–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuo, C.; Cao, H.; Ding, F.; Zhao, J.; Huang, Y.; Li, G.; Huang, S.; Jiang, H.; Jiang, Y.; Wang, F. Neuroprotective efficacy of different levels of high-frequency repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation in mice with CUMS-induced depression: Involvement of the p11/BDNF/Homer1a signaling pathway. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2020, 125, 152–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Q.; Lei, Y.; Yu, K.; Wu, J.; Xu, Z.; Wen, C.; Liu, Y.; Wang, W.; He, J. Repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation and fluoxetine attenuate astroglial activation and benefit behaviours in a chronic unpredictable mild stress mouse model of depression. World J. Biol. Psychiatry 2024, 25, 82–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Gui, T.; Zhang, S.; Wang, T.; Chen, X.; Ren, H.; Xu, C.; He, D.; Yao, L. Intermittent Theta Burst Stimulation Over Cerebellum Facilitates Neurological Recovery in Poststroke Depression via the cAMP/PKA/CREB Pathway. Stroke 2025, 56, 1266–1279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heath, A.; Lindberg, D.R.; Makowiecki, K.; Gray, A.; Asp, A.J.; Rodger, J.; Choi, D.S.; Croarkin, P.E. Medium- and high-intensity rTMS reduces psychomotor agitation with distinct neurobiologic mechanisms. Transl. Psychiatry 2018, 8, 126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cash, R.F.H.; Udupa, K.; Gunraj, C.A.; Mazzella, F.; Daskalakis, Z.J.; Wong, A.H.C.; Kennedy, J.L.; Chen, R. Influence of BDNF Val66Met polymorphism on excitatory-inhibitory balance and plasticity in human motor cortex. Clin. Neurophysiol. 2021, 132, 2827–2839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, C.M.; Hong, C.J.; Lin, H.C.; Chu, P.J.; Chen, M.H.; Tu, P.C.; Bai, Y.M.; Chang, W.H.; Juan, C.H.; Lin, W.C.; et al. Predictive roles of brain-derived neurotrophic factor Val66Met polymorphism on antidepressant efficacy of different forms of prefrontal brain stimulation monotherapy: A randomized, double-blind, sham-controlled study. J. Affect. Disord. 2022, 297, 353–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nitsche, M.A.; Paulus, W. Excitability changes induced in the human motor cortex by weak transcranial direct current stimulation. J. Physiol. 2000, 527 Pt 3, 633–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loo, C.K.; Husain, M.M.; McDonald, W.M.; Aaronson, S.; O’Reardon, J.P.; Alonzo, A.; Weickert, C.S.; Martin, D.M.; McClintock, S.M.; Mohan, A.; et al. International randomized-controlled trial of transcranial Direct Current Stimulation in depression. Brain Stimul. 2018, 11, 125–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavlova, E.L.; Menshikova, A.A.; Semenov, R.V.; Bocharnikova, E.N.; Gotovtseva, G.N.; Druzhkova, T.A.; Gersamia, A.G.; Gudkova, A.A.; Guekht, A.B. Transcranial direct current stimulation of 20- and 30-minutes combined with sertraline for the treatment of depression. Prog. Neuro-Psychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry 2018, 82, 31–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunoni, A.R.; Padberg, F.; Vieira, E.L.M.; Teixeira, A.L.; Carvalho, A.F.; Lotufo, P.A.; Gattaz, W.F.; Benseñor, I.M. Plasma biomarkers in a placebo-controlled trial comparing tDCS and escitalopram efficacy in major depression. Prog. Neuro-Psychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry 2018, 86, 211–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goerigk, S.; Cretaz, E.; Sampaio-Junior, B.; Vieira, É.L.M.; Gattaz, W.; Klein, I.; Lafer, B.; Teixeira, A.L.; Carvalho, A.F.; Lotufo, P.A.; et al. Effects of tDCS on neuroplasticity and inflammatory biomarkers in bipolar depression: Results from a sham-controlled study. Prog. Neuro-Psychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry 2021, 105, 110119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waye, S.C.; Dinesh, O.C.; Hasan, S.N.; Conway, J.D.; Raymond, R.; Nobrega, J.N.; Blundell, J.; Bambico, F.R. Antidepressant action of transcranial direct current stimulation in olfactory bulbectomised adolescent rats. J. Psychopharmacol. 2021, 35, 1003–1016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunoni, A.R.; Carracedo, A.; Amigo, O.M.; Pellicer, A.L.; Talib, L.; Carvalho, A.F.; Lotufo, P.A.; Benseñor, I.M.; Gattaz, W.; Cappi, C. Association of BDNF, HTR2A, TPH1, SLC6A4, and COMT polymorphisms with tDCS and escitalopram efficacy: Ancillary analysis of a double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Braz. J. Psychiatry 2020, 42, 128–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tillotson, K.J.; Sulzbach, W. A Comparative Study And Evaluation Of Electric Shock Therapy In Depressive States. Am. J. Psychiatry 1945, 101, 455–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz, A.C.; Haseeb, A.; Baumgartner, W.; Leung, E.; Scaini, G.; Quevedo, J. Correction: New insights into the mechanisms of electroconvulsive therapy in treatment-resistant depression. Front. Psychiatry 2025, 16, 1700480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, K.M.; Dunne, R.; McLoughlin, D.M. BDNF plasma levels and genotype in depression and the response to electroconvulsive therapy. Brain Stimul. 2018, 11, 1123–1131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorri, A.; Järventausta, K.; Kampman, O.; Lehtimäki, K.; Björkqvist, M.; Tuohimaa, K.; Hämäläinen, M.; Moilanen, E.; Leinonen, E. Effect of electroconvulsive therapy on brain-derived neurotrophic factor levels in patients with major depressive disorder. Brain Behav. 2018, 8, e01101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouckaert, F.; Dols, A.; Emsell, L.; De Winter, F.L.; Vansteelandt, K.; Claes, L.; Sunaert, S.; Stek, M.; Sienaert, P.; Vandenbulcke, M. Relationship Between Hippocampal Volume, Serum BDNF, and Depression Severity Following Electroconvulsive Therapy in Late-Life Depression. Neuropsychopharmacology 2016, 41, 2741–2748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Waarde, J.A.; Verwey, B.; van den Broek, W.W.; van der Mast, R.C. Electroconvulsive therapy in the Netherlands: A questionnaire survey on contemporary practice. J. ECT 2009, 25, 190–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Den Bossche, M.J.A.; Emsell, L.; Dols, A.; Vansteelandt, K.; De Winter, F.L.; Van den Stock, J.; Sienaert, P.; Stek, M.L.; Bouckaert, F.; Vandenbulcke, M. Hippocampal volume change following ECT is mediated by rs699947 in the promotor region of VEGF. Transl. Psychiatry 2019, 9, 191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Allen, A.P.; Naughton, M.; Dowling, J.; Walsh, A.; Ismail, F.; Shorten, G.; Scott, L.; McLoughlin, D.M.; Cryan, J.F.; Dinan, T.G.; et al. Serum BDNF as a peripheral biomarker of treatment-resistant depression and the rapid antidepressant response: A comparison of ketamine and ECT. J. Affect. Disord. 2015, 186, 306–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freire, T.F.; Fleck, M.P.; da Rocha, N.S. Remission of depression following electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) is associated with higher levels of brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF). Brain Res. Bull. 2016, 121, 263–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Zutphen, E.M.; Rhebergen, D.; van Exel, E.; Oudega, M.L.; Bouckaert, F.; Sienaert, P.; Vandenbulcke, M.; Stek, M.; Dols, A. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor as a possible predictor of electroconvulsive therapy outcome. Transl. Psychiatry 2019, 9, 155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maffioletti, E.; Gennarelli, M.; Gainelli, G.; Bocchio-Chiavetto, L.; Bortolomasi, M.; Minelli, A. BDNF Genotype and Baseline Serum Levels in Relation to Electroconvulsive Therapy Effectiveness in Treatment-Resistant Depressed Patients. J. ECT 2019, 35, 189–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanicek, T.; Kranz, G.S.; Vyssoki, B.; Fugger, G.; Komorowski, A.; Höflich, A.; Saumer, G.; Milovic, S.; Lanzenberger, R.; Eckert, A.; et al. Acute and subsequent continuation electroconvulsive therapy elevates serum BDNF levels in patients with major depression. Brain Stimul. 2019, 12, 1041–1050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vanicek, T.; Kranz, G.S.; Vyssoki, B.; Komorowski, A.; Fugger, G.; Höflich, A.; Micskei, Z.; Milovic, S.; Lanzenberger, R.; Eckert, A.; et al. Repetitive enhancement of serum BDNF subsequent to continuation ECT. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 2019, 140, 426–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mindt, S.; Neumaier, M.; Hellweg, R.; Sartorius, A.; Kranaster, L. Brain-Derived Neurotrophic Factor in the Cerebrospinal Fluid Increases During Electroconvulsive Therapy in Patients With Depression: A Preliminary Report. J. ECT 2020, 36, 193–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kranaster, L.; Hellweg, R.; Sartorius, A. Association between the novel seizure quality index for the outcome prediction in electroconvulsive therapy and brain-derived neurotrophic factor serum levels. Neurosci. Lett. 2019, 704, 164–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salehi, I.; Hosseini, S.M.; Haghighi, M.; Jahangard, L.; Bajoghli, H.; Gerber, M.; Pühse, U.; Holsboer-Trachsler, E.; Brand, S. Electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) and aerobic exercise training (AET) increased plasma BDNF and ameliorated depressive symptoms in patients suffering from major depressive disorder. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2016, 76, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loef, D.; Vansteelandt, K.; Oudega, M.L.; van Eijndhoven, P.; Carlier, A.; van Exel, E.; Rhebergen, D.; Sienaert, P.; Vandenbulcke, M.; Bouckaert, F.; et al. The ratio and interaction between neurotrophin and immune signaling during electroconvulsive therapy in late-life depression. Brain Behav. Immun. Health 2021, 18, 100389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schurgers, G.; Walter, S.; Pishva, E.; Guloksuz, S.; Peerbooms, O.; Incio, L.R.; Arts, B.M.G.; Kenis, G.; Rutten, B.P.F. Longitudinal alterations in mRNA expression of the BDNF neurotrophin signaling cascade in blood correlate with changes in depression scores in patients undergoing electroconvulsive therapy. Eur. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2022, 63, 60–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, X.H.; Xu, S.X.; Yao, L.; Chen, M.M.; Zhang, H.; Wang, C.; Nagy, C.; Liu, Z. Altered in vivo early neurogenesis traits in patients with depression: Evidence from neuron-derived extracellular vesicles and electroconvulsive therapy. Brain Stimul. 2024, 17, 19–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falhani, N.; Brunner, L.M.; Melchner, D.; Schwarzbach, J.V.; Rupprecht, R.; Nothdurfter, C. Electroconvulsive Therapy Changes Peripheral Blood Neurotrophic and Inflammatory Markers in Depressed Patients. J. ECT 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maynard, K.R.; Hobbs, J.W.; Rajpurohit, S.K.; Martinowich, K. Electroconvulsive seizures influence dendritic spine morphology and BDNF expression in a neuroendocrine model of depression. Brain Stimul. 2018, 11, 856–859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, X.; Hu, J.; Zang, X.; Xing, J.; Mo, X.; Hei, Z.; Gong, C.; Chen, C.; Zhou, S. Etomidate Improves the Antidepressant Effect of Electroconvulsive Therapy by Suppressing Hippocampal Neuronal Ferroptosis via Upregulating BDNF/Nrf2. Mol. Neurobiol. 2023, 60, 6584–6597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramnauth, A.D.; Maynard, K.R.; Kardian, A.S.; Phan, B.N.; Tippani, M.; Rajpurohit, S.; Hobbs, J.W.; Page, S.C.; Jaffe, A.E.; Martinowich, K. Induction of Bdnf from promoter I following electroconvulsive seizures contributes to structural plasticity in neurons of the piriform cortex. Brain Stimul. 2022, 15, 427–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, F.; Ardalan, M.; Elfving, B.; Wegener, G.; Madsen, T.M.; Nyengaard, J.R. Mitochondria Are Critical for BDNF-Mediated Synaptic and Vascular Plasticity of Hippocampus following Repeated Electroconvulsive Seizures. Int. J. Neuro-Psychopharmacol. 2018, 21, 291–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enomoto, S.; Shimizu, K.; Nibuya, M.; Suzuki, E.; Nagata, K.; Kondo, T. Activated brain-derived neurotrophic factor/TrkB signaling in rat dorsal and ventral hippocampi following 10-day electroconvulsive seizure treatment. Neurosci. Lett. 2017, 660, 45–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freire, T.F.; Rocha, N.S.; Fleck, M.P. Combining ECT with pharmacological treatment of depressed inpatients in a naturalistic study is not associated with serum BDNF level increase. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2016, 76, 30–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prudic, J.; Olfson, M.; Marcus, S.C.; Fuller, R.B.; Sackeim, H.A. Effectiveness of electroconvulsive therapy in community settings. Biol. Psychiatry 2004, 55, 301–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Available online: https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT02667353 (accessed on 27 October 2025).

- Stephani, C.; Shoukier, M.; Ahmed, R.; Wolff-Menzler, C. Polymorphism of the brain-derived neurotrophic factor and dynamics of the seizure threshold of electroconvulsive therapy. Eur. Arch. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 2017, 267, 787–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Psychiatric Association; Task Force on Electroconvulsive Therapy. The Practice of ECT: Recommendations for Treatment, Training and Privileging. Convuls. Ther. 1990, 6, 85–120. [Google Scholar]

- Espinoza, R.T.; Kellner, C.H. Electroconvulsive Therapy. N. Engl. J. Med. 2022, 386, 667–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enns, M.W.; Reiss, J.P. Electroconvulsive therapy. Can. J. Psychiatry 1992, 37, 671–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kobayashi, Y.; Segi-Nishida, E. Search for factors contributing to resistance to the electroconvulsive seizure treatment model using adrenocorticotrophic hormone-treated mice. Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav. 2019, 186, 172767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, F.; Danladi, J.; Wegener, G.; Madsen, T.M.; Nyengaard, J.R. Sustained Ultrastructural Changes in Rat Hippocampal Formation After Repeated Electroconvulsive Seizures. Int. J. Neuro-Psychopharmacol. 2020, 23, 446–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Mao, L.; Huang, Z.; Switzer, J.A.; Hess, D.C.; Zhang, Q. Photobiomodulation: Shining a light on depression. Theranostics 2025, 15, 362–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewy, A.J.; Kern, H.A.; Rosenthal, N.E.; Wehr, T.A. Bright artificial light treatment of a manic-depressive patient with a seasonal mood cycle. Am. J. Psychiatry 1982, 139, 1496–1498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farazi, N.; Mahmoudi, J.; Sadigh-Eteghad, S.; Farajdokht, F.; Rasta, S.H. Synergistic effects of combined therapy with transcranial photobiomodulation and enriched environment on depressive- and anxiety-like behaviors in a mice model of noise stress. Lasers Med. Sci. 2022, 37, 1181–1191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Li, H.; Sun, J.; Hu, W.; Jin, W.; Li, S.; Tong, S. Antidepressant-Like Effect of Low-Intensity Transcranial Ultrasound Stimulation. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng. 2019, 66, 411–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.; He, J.; Zhu, Y.; Wu, J.; Chen, Y.; Yuan, M.; Cheng, Z.; Zeng, L.; Ji, X. Ultrasound neuromodulation ameliorates chronic corticosterone-induced depression- and anxiety-like behaviors in mice. J. Neural Eng. 2023, 20, 036037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lang, A.E.; Lozano, A.M. Parkinson’s disease. Second of two parts. N. Engl. J. Med. 1998, 339, 1130–1143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mayberg, H.S.; Lozano, A.M.; Voon, V.; McNeely, H.E.; Seminowicz, D.; Hamani, C.; Schwalb, J.M.; Kennedy, S.H. Deep brain stimulation for treatment-resistant depression. Neuron 2005, 45, 651–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, F.; Huang, S.; Guo, D.; Li, X.; Han, Y. Deep brain stimulation of ventromedial prefrontal cortex reverses depressive-like behaviors via BDNF/TrkB signaling pathway in rats. Life Sci. 2023, 334, 122222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Z.; Jia, L.; Shi, D.; He, Y.; Ren, Y.; Yang, J.; Ma, X. Deep brain stimulation improved depressive-like behaviors and hippocampal synapse deficits by activating the BDNF/mTOR signaling pathway. Behav. Brain Res. 2022, 419, 113709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dandekar, M.P.; Saxena, A.; Scaini, G.; Shin, J.H.; Migut, A.; Giridharan, V.V.; Zhou, Y.; Barichello, T.; Soares, J.C.; Quevedo, J.; et al. Medial Forebrain Bundle Deep Brain Stimulation Reverses Anhedonic-Like Behavior in a Chronic Model of Depression: Importance of BDNF and Inflammatory Cytokines. Mol. Neurobiol. 2019, 56, 4364–4380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiménez-Sánchez, L.; Linge, R.; Campa, L.; Valdizán, E.M.; Pazos, Á.; Díaz, Á.; Adell, A. Behavioral, neurochemical and molecular changes after acute deep brain stimulation of the infralimbic prefrontal cortex. Neuropharmacology 2016, 108, 91–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, H.C.; Jo, B.G.; Lee, C.Y.; Lee, K.W.; Namgung, U. Hippocampal activation of 5-HT(1B) receptors and BDNF production by vagus nerve stimulation in rats under chronic restraint stress. Eur. J. Neurosci. 2019, 50, 1820–1830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valente, C.; Neves, M.L.; Kraus, S.I.; Silva, M.D.D. Vagus nerve stimulation -induced anxiolytic and neurotrophic effect in healthy rats. An. Acad. Bras. Cienc. 2025, 97, e20241292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shah, A.P.; Carreno, F.R.; Wu, H.; Chung, Y.A.; Frazer, A. Role of TrkB in the anxiolytic-like and antidepressant-like effects of vagal nerve stimulation: Comparison with desipramine. Neuroscience 2016, 322, 273–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia, L.S.; Comim, C.M.; Valvassori, S.S.; Réus, G.Z.; Stertz, L.; Kapczinski, F.; Gavioli, E.C.; Quevedo, J. Ketamine treatment reverses behavioral and physiological alterations induced by chronic mild stress in rats. Prog. Neuro-Psychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry 2009, 33, 450–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zabara, J. Peripheral control of hypersynchronous discharge in epilepsy. Electroencephalogr. Clin. Neurophysiol. 1985, 61, S162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carreno, F.R.; Frazer, A. Activation of signaling pathways downstream of the brain-derived neurotrophic factor receptor, TrkB, in the rat brain by vagal nerve stimulation and antidepressant drugs. Int. J. Neuro-Psychopharmacol. 2014, 17, 247–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furmaga, H.; Shah, A.; Frazer, A. Serotonergic and noradrenergic pathways are required for the anxiolytic-like and antidepressant-like behavioral effects of repeated vagal nerve stimulation in rats. Biol. Psychiatry 2011, 70, 937–945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Non-Invasive | Invasive | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Method | Effect | Method | Effect |

| Transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) | - increased synaptic plasticity - membrane potentials modulation - network activation | Deep brain stimulation (DBS) | - neurotransmitter modulation - network activation - neuroprotection - neurogenesis |

| Transcranial direct and alternating current stimulation (tDCS, tACS) | - membrane potentials modulation - neurotransmitter modulation - oscillations synchronization | Vagus nerve stimulation (VNS) | - neurotransmitter modulation - increased neuroplasticity - anti-inflammatory and anti-apoptotic action |

| Transcranial random noise stimulation (tRNS) | - neural excitability modulation - neurotransmitter modulation | Epidural cortical stimulation | - increased synaptic plasticity - network modulation - increased release of endogenous opioids |

| Transcranial photobiomodulation (tPBM) | - mitochondrial function improvement - antioxidant and anti-inflammatory action - neurogenesis promotion | ||

| Transcranial ultrasound stimulation (TUS) and focused ultrasound stimulation (FUS) | - vascular function modulation - neuronal activity modulation - oscillations modulation | ||

| Trigeminal nerve stimulation (TNS) | - neurotransmitter modulation - vascular function modulation - anti-inflammatory action - brain metabolism modulation | ||

| Electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) | - neurotransmitter modulation - network activation - increased synaptic plasticity - anti-inflammatory action | ||

| Applied Methodology | Induced Depression | Neurotrophin System Alterations | Outcome | Ref. | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Name | Protocol | Neurotrophins | Neurotrophin Receptors | Downstream Mechanisms | |||

| DBS (vmPFC, bilateral) | 130 Hz, 200 μA, 90 μs pulses, 5 h/d, 7 d | CUMS in rat experimental model | BDNF ↑ | TrkB ↑ | ERK1/2 ↑ | Depressive-like behavior ↓ | [123] |

| DBS (vmPFC, unilateral) | 20 Hz, 1 h/d, 28 d | CUMS in rat experimental model | BDNF ↑ | - | BDNF/mTOR ↑ | Depressive-like behavior ↓ | [124] |

| DBS (MFB, unilateral) | 130 Hz, 200-μA amplitude, 90-μs pulse width, 8 h/d, 7 d | CUMS in rat experimental model | BDNF ↑ | - | Neuroinflammation ↓ | Depressive-like behavior ↓ | [125] |

| DBS (IlmPFC, unilateral) | 130 Hz, 200 μA, 90 μs, for 1 h | OBX in rat experimental model | BDNF ↑ | - | ERK/CREB ↑ BDNF/mTOR ↑ | Depressive-like behavior ↓ | [126] |

| VNS (bipolar hook electrode, neck region) | 10 mA, 5 Hz, 5 ms of pulse duration, 5 min, 14 d | CRS in rat experimental model | BDNF ↑ | - | p-Erk1/2 ↑ | Depressive-like behavior ↓ | [127] |

| VNS (ABVN) | Acupuncture needles, pinna skin | None (healthy rats) | BDNF ↑ | - | - | Depressive-like behavior n.c. | [128] |

| VNS (unilateral cervical region) | Acute: 0.25 mA, 20 Hz, 0.25 ms, 30 s on, 300 s off Chronic: 24 d | None (healthy rats) | - | TrkB ↑ | Depressive-like behavior ↓ | [129] | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Selakovic, D.; Mitrovic, M.; Ljujic, B.; Janjic, V.; Milovanovic, D.; Jovicic, N.; Simovic Markovic, B.; Corovic, I.; Vasiljevic, M.; Milanovic, P.; et al. Transcranial Stimulation Methods in the Treatment of MDD Patients—The Role of the Neurotrophin System. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 11878. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262411878

Selakovic D, Mitrovic M, Ljujic B, Janjic V, Milovanovic D, Jovicic N, Simovic Markovic B, Corovic I, Vasiljevic M, Milanovic P, et al. Transcranial Stimulation Methods in the Treatment of MDD Patients—The Role of the Neurotrophin System. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2025; 26(24):11878. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262411878

Chicago/Turabian StyleSelakovic, Dragica, Marina Mitrovic, Biljana Ljujic, Vladimir Janjic, Dragan Milovanovic, Nemanja Jovicic, Bojana Simovic Markovic, Irfan Corovic, Milica Vasiljevic, Pavle Milanovic, and et al. 2025. "Transcranial Stimulation Methods in the Treatment of MDD Patients—The Role of the Neurotrophin System" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 26, no. 24: 11878. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262411878

APA StyleSelakovic, D., Mitrovic, M., Ljujic, B., Janjic, V., Milovanovic, D., Jovicic, N., Simovic Markovic, B., Corovic, I., Vasiljevic, M., Milanovic, P., Stevanovic, M., Rosic, S., Randjelovic, S., Fetahovic, E., Chopra, A., Milosavljevic, J., & Rosic, G. (2025). Transcranial Stimulation Methods in the Treatment of MDD Patients—The Role of the Neurotrophin System. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 26(24), 11878. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262411878