Chloroplast Responses to Drought: Integrative Mechanisms and Mitigation Strategies

Abstract

1. Introduction

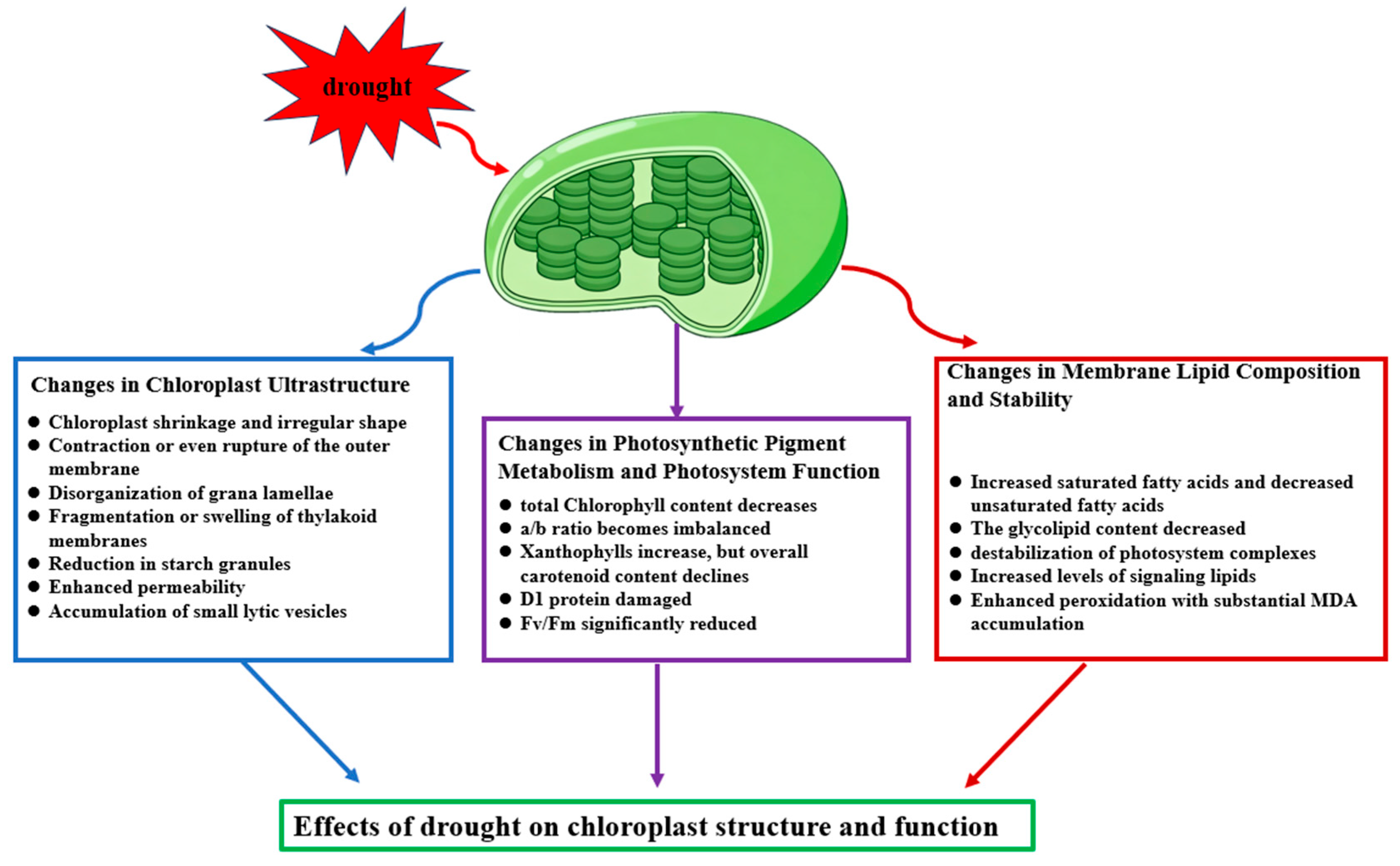

2. Effects of Drought on Chloroplast Structure and Function

2.1. Changes in Chloroplast Ultrastructure

2.2. Changes in Photosynthetic Pigment Metabolism and Photosystem Function

2.3. Changes in Membrane Lipid Composition and Stability

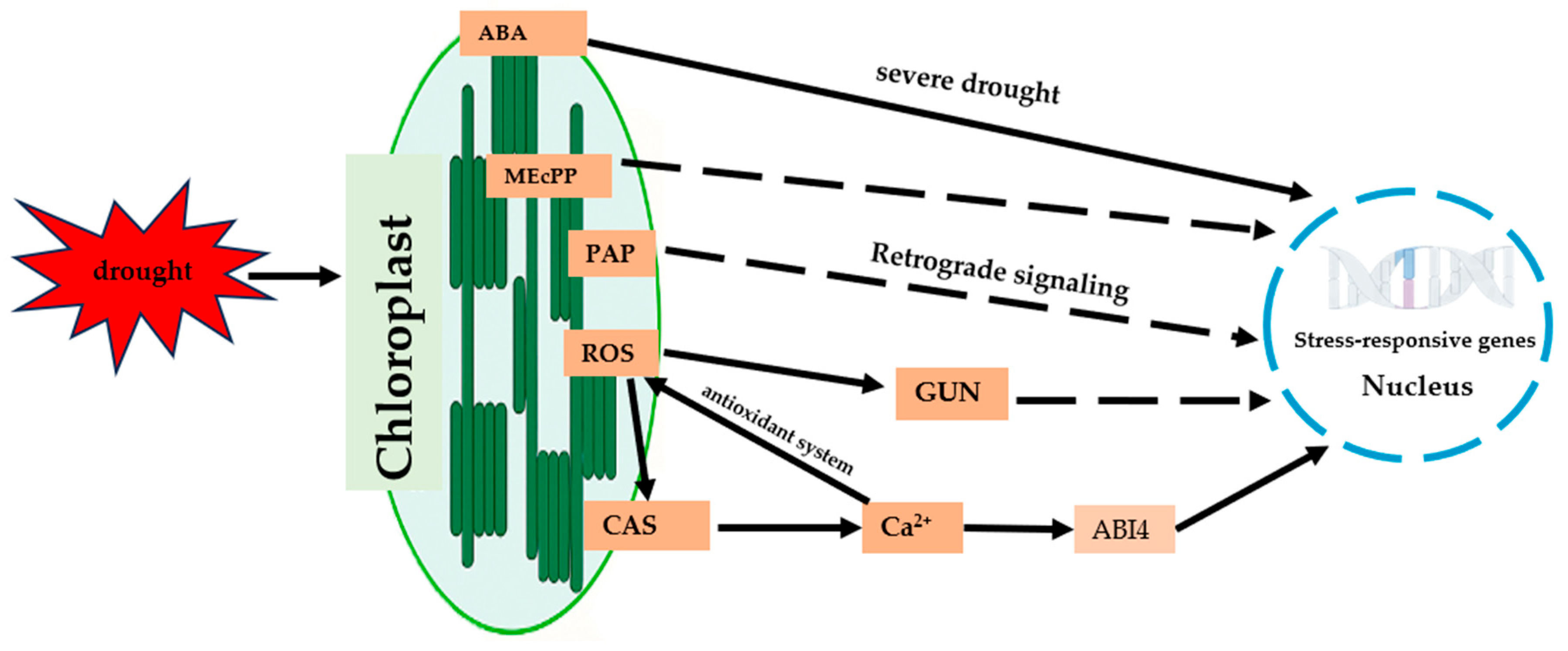

3. Chloroplast Signaling Under Drought Stress

3.1. ROS Signaling and Antioxidant Systems

3.2. Calcium Signaling and Membrane Receptors

3.3. Chloroplast Retrograde Signaling

3.3.1. The GUN Pathway

3.3.2. The PAP Signaling Pathway

3.3.3. The MEcPP Signaling Pathway

3.3.4. Signal Integration and Crosstalk

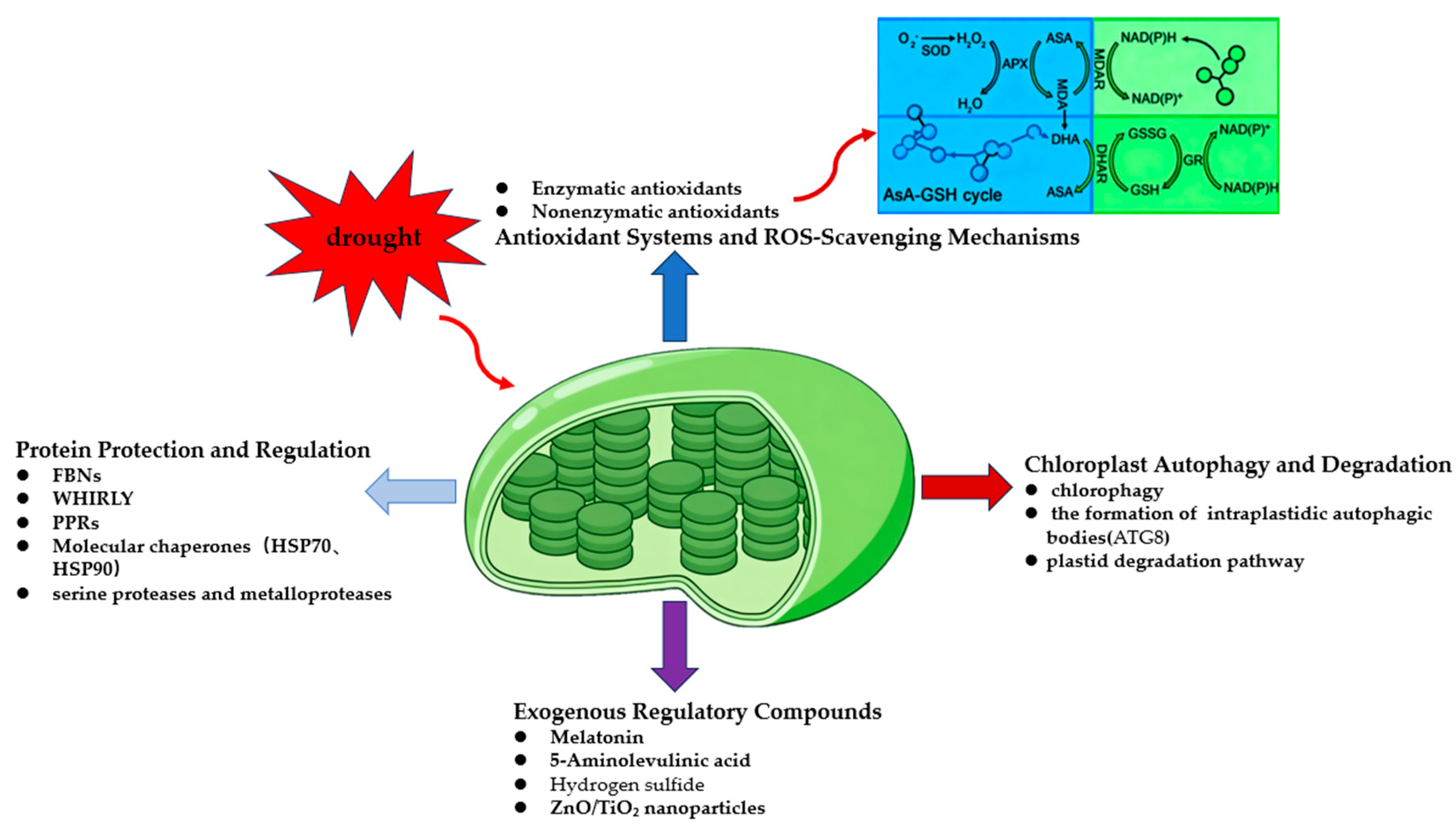

4. Chloroplast Protection and Repair Mechanisms

4.1. Protein Protection and Regulation

4.2. Antioxidant Systems and ROS-Scavenging Mechanisms

4.3. Functional Regulators

4.4. Chloroplast Autophagy and Degradation

5. Perspectives and Future Directions

5.1. Systematic Analysis of Chloroplast Signaling Networks

5.2. Applications of Regulatory Compounds and Novel Materials

5.3. Prospects for Molecular Breeding

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ozturk, M.; Turkyilmaz Unal, B.; García-Caparrós, P.; Khursheed, A.; Gul, A.; Hasanuzzaman, M. Osmoregulation and its actions during the drought stress in plants. Physiol. Plant. 2021, 172, 1321–1335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, S.; Wu, S.; Gao, J.; Liu, L.; Li, D.; Yan, R.; Wang, J. Increased stress from compound drought and heat events on vegetation. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 949, 175113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tripathy, K.P.; Mukherjee, S.; Mishra, A.K.; Mann, M.E.; Williams, A.P. Climate change will accelerate the high-end risk of compound drought and heatwave events. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2023, 120, e2219825120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sato, H.; Mizoi, J.; Shinozaki, K.; Yamaguchi-Shinozaki, K. Complex plant responses to drought and heat stress under climate change. Plant J. 2024, 117, 1873–1892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filek, M.; Łabanowska, M.; Kurdziel, M.; Wesełucha-Birczyńska, A.; Bednarska-Kozakiewicz, E. Structural and biochemical response of chloroplasts in tolerant and sensitive barley genotypes to drought stress. J. Plant Physiol. 2016, 207, 61–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haghpanah, M.; Hashemipetroudi, S.; Arzani, A.; Araniti, F. Drought tolerance in plants: Physiological and molecular responses. Plants 2024, 13, 2962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, X.; Lu, M.; Wang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Liu, Z.; Chen, S. Response mechanism of plants to drought stress. Horticulturae 2021, 7, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Y.-S.; Javed, T.; Liu, T.-T.; Ali, A.; Gao, S.-J. Mechanisms of Abscisic acid (ABA)-mediated plant defense responses: An updated review. Plant Stress 2025, 15, 100724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farquhar, G.D.; von Caemmerer, S.; Berry, J.A. A biochemical model of photosynthetic CO2 assimilation in leaves of C3 species. Planta 1980, 149, 78–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qiao, M.; Hong, C.; Jiao, Y.; Hou, S.; Gao, H. Impacts of Drought on Photosynthesis in Major Food Crops and the Related Mechanisms of Plant Responses to Drought. Plants 2024, 13, 1808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richter, A.S.; Nägele, T.; Grimm, B.; Kaufmann, K.; Schroda, M.; Leister, D.; Kleine, T. Retrograde signaling in plants: A critical review focusing on the GUN pathway and beyond. Plant Commun. 2023, 4, 100511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Kim, C. Chloroplast ROS and stress signaling. Plant Commun. 2022, 3, 100264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krupinska, K.; Desel, C.; Frank, S.; Hensel, G. WHIRLIES are multifunctional DNA-Binding proteins with impact on plant development and stress resistance. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 880423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dilnawaz, F.; Misra, A.N.; Apostolova, E. Involvement of nanoparticles in mitigating plant’s abiotic stress. Plant Stress 2023, 10, 100280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mittler, R. Oxidative stress, antioxidants and stress tolerance. Trends Plant Sci. 2002, 7, 405–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zivcak, M.; Brestic, M.; Balatova, Z.; Drevenakova, P.; Olsovska, K.; Kalaji, H.M.; Yang, X.; Allakhverdiev, S.I. Photosynthetic electron transport and specific photoprotective responses in wheat leaves under drought stress. Photosynth. Res. 2013, 117, 529–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sevanto, S. Phloem transport and drought. J. Exp. Bot. 2014, 65, 1751–1759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawson, T.; Matthews, J. Guard cell metabolism and stomatal function. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2020, 71, 273–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benning, C. Mechanisms of lipid transport involved in organelle biogenesis in plant cells. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 2009, 25, 71–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tambussi, E.A.; Bartoli, C.G.; Beltrano, J.; Guiamet, J.J.; Araus, J.L. Oxidative damage to thylakoid proteins in water-stressed leaves of wheat (Triticum aestivum). Physiol. Plant. 2000, 108, 398–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Z.; Zhang, Y.Q.; Zhang, H.H.; Luo, W.H.; Chen, A.P. Effects of drought stress on chloroplast ultrastructure and physiological characteristics of Seriphidium transiliense seedlings. Pratacultural Sci. 2025, 42, 1403–1413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, F.; Zhang, Y.; Guo, J. Effects of drought stress on photosynthetic physiological characteristics, leaf microstructure, and related gene expression of yellow horn. Plant Signal. Behav. 2023, 18, 2215025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, R.X.; Xin, L.F.; Zheng, H.F.; Li, L.L.; Ran, W.L.; Mao, J.; Yang, Q.H. Changes in chloroplast ultrastructure in leaves of drought-stressed maize inbred lines. Photosynthetica 2016, 54, 74–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F.; Zhang, K.; Du, C.; Li, J.; Xing, Y.; Yang, L.; Li, Y. Effect of drought stress on anatomical structure and chloroplast ultrastructure in leaves of sugarcane. Sugar Tech. 2014, 17, 41–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grigorova, B.; Vassileva, V.; Klimchuk, D.; Vaseva, I.; Demirevska, K.; Feller, U. Drought, high temperature, and their combination affect ultrastructure of chloroplasts and mitochondria in wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) leaves. J. Plant Interact. 2012, 7, 204–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarma, B.; Kashtoh, H.; Lama Tamang, T.; Bhattacharyya, P.N.; Mohanta, Y.K.; Baek, K.-H. Abiotic stress in rice: Visiting the physiological response and its tolerance mechanisms. Plants 2023, 12, 3948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- V, P.; Ali, K.; Singh, A.; Vishwakarma, C.; Krishnan, V.; Chinnusamy, V.; Tyagi, A. Starch accumulation in rice grains subjected to drought during grain filling stage. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2019, 142, 440–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Li, R.; Guo, P.; Xia, Y.; Tian, C.; Miao, S. Impact of drought stress on the ultrastructure of leaf cells in three barley genotypes differing in level of drought tolerance. Chin. Bull. Bot. 2011, 46, 28–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hajibarat, Z.; Saidi, A. Senescence-associated proteins and nitrogen remobilization in grain filling under drought stress condition. J. Genet. Eng. Biotechnol. 2022, 20, 101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ni, K.; Dai, M.; Lu, X.; Zhang, Y.; Fan, Y.; Xu, N.; Feng, X.; Huang, H.; Wang, J.; Rui, C.; et al. Pretreatment of NaCl enhances the drought resistance of cotton by regulating the biosynthesis of carotenoids and abscisic acid. Front. Environ. Sci. 2022, 10, 998141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, C.; Zhang, J. Effects of water stress on photosystem II photochemistry and its thermostability in wheat plants. J. Exp. Bot. 1999, 50, 1199–1206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barber, J. Photosystem II: A multisubunit membrane protein that oxidises water. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 2002, 12, 523–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barber, J.; Nield, J.; Morris, E.P.; Hankamer, B. Subunit positioning in photosystem II revisited. Trends Biochem. Sci. 1999, 24, 43–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Küpper, H.; Benedikty, Z.; Morina, F.; Andresen, E.; Mishra, A.; Trtílek, M. Analysis of OJIP chlorophyll fluorescence kinetics and QA reoxidation kinetics by direct fast imaging. Plant Physiol. 2019, 179, 369–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Govindjee, G. On the evolution of the concept of two light reactions and two photosystems for oxygenic photosynthesis: A personal perspective. Photosynthetica 2023, 61, 37–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demmig-Adams, B.; Hodges, A.K.; Polutchko, S.K.; Adams, W.W. Zeaxanthin and other carotenoids: Roles in abiotic stress defense with implications for biotic defense. Plants 2025, 14, 2703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nosalewicz, A.; Okoń, K.; Skorupka, M. Non-photochemical quenching under drought and fluctuating light. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 5182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghotbi-Ravandi, A.A.; Sedighi, M.; Aghaei, K.; Mohtadi, A. Differential changes in D1 protein content and quantum yield of wild and cultivated barley genotypes caused by moderate and severe drought stress in relation to oxidative stress. Plant Mol. Biol. Rep. 2021, 39, 501–507, Correction to Plant Mol. Biol. Rep. 2022, 40, 218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bashir, N.; Athar, H.-u.-R.; Kalaji, H.M.; Wróbel, J.; Mahmood, S.; Zafar, Z.U.; Ashraf, M. Is photoprotection of PSII one of the key mechanisms for drought tolerance in Maize? Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 13490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colom, M.R.; Vazzana, C. Photosynthesis and PSII functionality of drought-resistant and drought-sensitive weeping lovegrass plants. Environ. Exp. Bot. 2003, 49, 135–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trueba, S.; Pan, R.; Scoffoni, C.; John, G.P.; Davis, S.D.; Sack, L. Thresholds for leaf damage due to dehydration: Declines of hydraulic function, stomatal conductance and cellular integrity precede those for photochemistry. New Phytol. 2019, 223, 134–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chng, C.P.; Wang, K.; Ma, W.; Hsia, K.J.; Huang, C. Chloroplast membrane lipid remodeling protects against dehydration by limiting membrane fusion and distortion. Plant Physiol. 2022, 188, 526–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Liu, L.N.; Meng, Q.; Fan, H.; Sui, N. The roles of chloroplast membrane lipids in abiotic stress responses. Plant Signal. Behav. 2020, 15, 1807152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y.; Xia, Z.; Wu, J.; Ma, H. Effects of repeated drought stress on the physiological characteristics and lipid metabolism of Bombax ceiba L. during subsequent drought and heat stresses. BMC Plant Biol. 2021, 21, 467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, D.; Wang, S.; Qi, L.; Yin, L.; Deng, X. Galactolipid remodeling is involved in drought-induced leaf senescence in maize. Environ. Exp. Bot. 2018, 150, 57–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, S.; Liu, D.; Chu, M.; Liu, X.; Wei, Y.; Che, X.; Zhu, L.; He, L.; Xu, J. Dynamic and adaptive membrane lipid remodeling in leaves of sorghum under salt stress. Crop J. 2022, 10, 1557–1569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasanuzzaman, M.; Bhuyan, M.H.M.B.; Parvin, K.; Bhuiyan, T.F.; Anee, T.I.; Nahar, K.; Hossen, M.S.; Zulfiqar, F.; Alam, M.M.; Fujita, M. Regulation of ROS metabolism in plants under environmental stress: A review of recent experimental evidence. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 8695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Juan, C.A.; Pérez de la Lastra, J.M.; Plou, F.J.; Pérez-Lebeña, E. The chemistry of reactive oxygen species (ROS) revisited: Outlining their role in biological macromolecules (DNA, Lipids and Proteins) and induced pathologies. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 4642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, M.; Ding, N.Z. Plant unsaturated fatty acids: Multiple roles in stress response. Front. Plant Sci. 2020, 11, 562785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Zhang, X.; Huang, G.; Feng, F.; Liu, X.; Guo, R.; Gu, F.; Zhong, X.; Mei, X. Dynamic changes in membrane lipid composition of leaves of winter wheat seedlings in response to PEG-induced water stress. BMC Plant Biol. 2020, 20, 84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kranzlein, M.; Schmockel, S.M.; Geilfus, C.M.; Schulze, W.X.; Altenbuchinger, M.; Hrenn, H.; Roessner, U.; Zorb, C. Lipid remodeling of contrasting maize (Zea mays L.) hybrids under repeated drought. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14, 1050079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, L.; Zhou, C.; Fan, J.; Shanklin, J.; Xu, C. Mechanisms and functions of membrane lipid remodeling in plants. Plant J. 2021, 107, 37–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, P.; Lakra, N.; Goyal, A.; Ahlawat, Y.K.; Zaid, A.; Siddique, K.H.M. Drought and heat stress mediated activation of lipid signaling in plants: A critical review. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14, 1216835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Wang, B.; Li, W.-J.; Wang, X.-J.; Zhao, S.-Z. Research Progress on Production, Scavenging and Signal Transduction of ROS Under Drought Stress. Biotechnol. Bull. 2021, 37, 194–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.P.; Kim, C. Photosynthetic ROS and retrograde signaling pathways. New Phytol. 2024, 244, 1183–1198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grieco, M.; Roustan, V.; Dermendjiev, G.; Rantala, S.; Jain, A.; Leonardelli, M.; Neumann, K.; Berger, V.; Engelmeier, D.; Bachmann, G.; et al. Adjustment of photosynthetic activity to drought and fluctuating light in wheat. Plant Cell Environ. 2020, 43, 1484–1500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhuang, X.; Jiang, L. Chloroplast degradation: Multiple routes into the vacuole. Front. Plant Sci. 2019, 10, 359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Foyer, C.H.; Shigeoka, S. Understanding oxidative stress and antioxidant functions to enhance photosynthesis. Plant Physiol. 2011, 155, 93–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noctor, G.; Foyer, C.H. Ascorbate and glutathione: Keeping active oxygen under control. Annu. Rev. Plant Physiol. Plant Mol. Biol. 1998, 49, 249–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moussa, H.R.; Abdel-Aziz, S.M. Comparative response of drought tolerant and drought sensitive maize genotypes to water stress. Aust. J. Crop Sci. 2008, 1, 31–36. [Google Scholar]

- Harb, A.; Awad, D.; Samarah, N. Gene expression and activity of antioxidant enzymes in barley (Hordeum vulgare L.) under controlled severe drought. J. Plant Interact. 2015, 10, 109–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Hou, L.; Song, C.; Wang, Z.; Xue, Q.; Li, Y.; Qin, J.; Cao, N.; Jia, C.; Zhang, Y.; et al. Biological function of calcium-sensing receptor (CAS) and its coupling calcium signaling in plants. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2022, 180, 74–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Navazio, L.; Formentin, E.; Cendron, L.; Szabo, I. Chloroplast calcium signaling in the spotlight. Front. Plant Sci. 2020, 11, 186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weinl, S.; Held, K.; Schlucking, K.; Steinhorst, L.; Kuhlgert, S.; Hippler, M.; Kudla, J. A plastid protein crucial for Ca2+-regulated stomatal responses. New Phytol. 2008, 179, 675–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corti, F.; Festa, M.; Stein, F.; Stevanato, P.; Siroka, J.; Navazio, L.; Vothknecht, U.C.; Alboresi, A.; Novak, O.; Formentin, E.; et al. Comparative analysis of wild-type and chloroplast MCU-deficient plants reveals multiple consequences of chloroplast calcium handling under drought stress. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14, 1228060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giridhar, M.; Meier, B.; Imani, J.; Kogel, K.-H.; Peiter, E.; Vothknecht, U.C.; Chigri, F. Comparative analysis of stress-induced calcium signals in the crop species barley and the model plant Arabidopsis thaliana. BMC Plant Biol. 2022, 22, 447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teardo, E.; Carraretto, L.; Moscatiello, R.; Cortese, E.; Vicario, M.; Festa, M.; Maso, L.; De Bortoli, S.; Calì, T.; Vothknecht, U.C.; et al. A chloroplast-localized mitochondrial calcium uniporter transduces osmotic stress in Arabidopsis. Nat. Plants 2019, 5, 581–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, P.; Baum, M.; Grando, S.; Ceccarelli, S.; Bai, G.; Li, R.; von Korff, M.; Varshney, R.K.; Graner, A.; Valkoun, J. Differentially expressed genes between drought-tolerant and drought-sensitive barley genotypes in response to drought stress during the reproductive stage. J. Exp. Bot. 2009, 60, 3531–3544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lasorella, C.; Fortunato, S.; Dipierro, N.; Jeran, N.; Tadini, L.; Vita, F.; Pesaresi, P.; de Pinto, M.C. Chloroplast-localized GUN1 contributes to the acquisition of basal thermotolerance in Arabidopsis thaliana. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 1058831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Veen, E.; Kupers, J.J.; Gommers, C.M.M. Plastids in a pinch: Coordinating stress and developmental responses through retrograde signalling. Plant Cell Environ. 2025, 48, 6897–6911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shimizu, T.; Masuda, T. The role of tetrapyrrole and GUN1 dependent signaling on chloroplast biogenesis. Plants 2021, 10, 196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crawford, T.; Lehotai, N.; Strand, Å. The role of retrograde signals during plant stress responses. J. Exp. Bot. 2017, 69, 2783–2795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estavillo, G.M.; Crisp, P.A.; Pornsiriwong, W.; Wirtz, M.; Collinge, D.; Carrie, C.; Giraud, E.; Whelan, J.; David, P.; Javot, H.; et al. Evidence for a SAL1-PAP chloroplast retrograde pathway that functions in drought and high light signaling in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 2011, 23, 3992–4012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benn, G.; Bjornson, M.; Ke, H.; De Souza, A.; Balmond, E.I.; Shaw, J.T.; Dehesh, K. Plastidial metabolite MEcPP induces a transcriptionally centered stress-response hub via the transcription factor CAMTA3. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2016, 113, 8855–8860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bali, S.; Mohapatra, S.; Michael, R.; Arora, R.; Dogra, V. Plastidial metabolites and retrograde signaling: A case study of MEP pathway intermediate MEcPP that orchestrates plant growth and stress responses. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2025, 222, 109747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Y.; Savchenko, T.; Baidoo, E.E.K.; Chehab, W.E.; Hayden, D.M.; Tolstikov, V.; Corwin, J.A.; Kliebenstein, D.J.; Keasling, J.D.; Dehesh, K. Retrograde signaling by the plastidial metabolite MEcPP regulates expression of nuclear stress-response genes. Cell 2012, 149, 1525–1535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pornsiriwong, W.; Estavillo, G.M.; Chan, K.X.; Tee, E.E.; Ganguly, D.; Crisp, P.A.; Phua, S.Y.; Zhao, C.; Qiu, J.; Park, J.; et al. A chloroplast retrograde signal, 3′-phosphoadenosine 5′-phosphate, acts as a secondary messenger in abscisic acid signaling in stomatal closure and germination. eLife 2017, 6, e23361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saxena, I.; Srikanth, S.; Chen, Z. Cross talk between H2O2 and interacting signal molecules under plant stress response. Front. Plant Sci. 2016, 7, 570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, H.; Feng, P.; Chi, W.; Sun, X.; Xu, X.; Li, Y.; Ren, D.; Lu, C.; David Rochaix, J.; Leister, D.; et al. Plastid-nucleus communication involves calcium-modulated MAPK signalling. Nat. Commun. 2016, 7, 12173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, G.-Z.; Bock, R. GUN control in retrograde signaling: How GENOMES UNCOUPLED proteins adjust nuclear gene expression to plastid biogenesis. Plant Cell 2021, 33, 457–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Song, S.; Zhang, H.; Li, Y.; Niu, L.; Zhang, J.; Wang, W. Signaling transduction of ABA, ROS, and Ca2+ in plant stomatal closure in response to drought. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 14824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Sappah, A.H.; Li, J.; Yan, K.; Zhu, C.; Huang, Q.; Zhu, Y.; Chen, Y.; El-Tarabily, K.A.; AbuQamar, S.F. Fibrillin gene family and its role in plant growth, development, and abiotic stress. Front. Plant Sci. 2024, 15, 1453974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, I.; Kim, E.-H.; Choi, Y.-r.; Kim, H.U. Fibrillin2 in chloroplast plastoglobules participates in photoprotection and jasmonate-induced senescence. Plant Physiol. 2022, 189, 1363–1379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taylor, R.E.; West, C.E.; Foyer, C.H. WHIRLY protein functions in plants. Food Energy Secur. 2023, 12, e379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, T.; Zhao, P.; Sun, J.; Zhao, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Yang, Q.; Wang, W.; Chen, Z.; Mai, T.; Zou, Y.; et al. Research progress of PPR proteins in RNA editing, stress response, plant growth and development. Front. Genet. 2021, 12, 765580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Yang, Z.; Zhang, M.; Ai, P. A chloroplast-localized pentatricopeptide repeat protein involved in RNA editing and splicing and its effects on chloroplast development in rice. BMC Plant Biol. 2022, 22, 437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Y.; Li, X.; Fan, B.; Zhu, C.; Chen, Z. Chloroplasts protein quality control and turnover: A multitude of mechanisms. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 7760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lindahl, M.; Spetea, C.; Hundal, T.; Oppenheim, A.B.; Adam, Z.; Andersson, B. The thylakoid FtsH protease plays a role in the light-induced turnover of the photosystem II D1 protein. Plant Cell 2000, 12, 419–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haußühl, K.; Andersson, B.; Adamska, I. A chloroplast DegP2 protease performs the primary cleavage of the photodamaged D1 protein in plant photosystem II. EMBO J. 2001, 20, 713–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Samanta, S.; Seth, C.S.; Roychoudhury, A. The molecular paradigm of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and reactive nitrogen species (RNS) with different phytohormone signaling pathways during drought stress in plants. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2024, 206, 108259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foyer, C.H.; Noctor, G. Redox Homeostasis and Antioxidant Signaling: A Metabolic Interface between Stress Perception and Physiological Responses. Plant Cell 2005, 17, 1866–1875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foyer, C.H.; Kunert, K. The ascorbate–glutathione cycle coming of age. J. Exp. Bot. 2024, 75, 2682–2699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sofo, A.; Scopa, A.; Nuzzaci, M.; Vitti, A. Ascorbate peroxidase and catalase activities and their genetic regulation in plants subjected to drought and salinity stresses. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2015, 16, 13561–13578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Liu, H.; Yu, F.; Hu, B.; Jia, Y.; Sha, H.; Zhao, H. Differential activity of the antioxidant defence system and alterations in the accumulation of osmolyte and reactive oxygen species under drought stress and recovery in rice (Oryza sativa L.) tillering. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 8543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ren, J.; Sun, L.N.; Zhang, Q.Y.; Song, X.S. Drought tolerance is correlated with the activity of antioxidant enzymes in cerasus humilis seedlings. BioMed Res. Int. 2016, 2016, 9851095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, D.; Liu, W.; Chen, K.; Ning, S.; Gao, Q.; Chen, J.; Liu, J.; Sun, X.; Xu, W. Exogenous substances used to relieve plants from drought stress and their associated underlying mechanisms. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 9249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasheed, R.; Yasmeen, H.; Hussain, I.; Iqbal, M.; Ashraf, M.A.; Parveen, A. Exogenously applied 5-aminolevulinic acid modulates growth, secondary metabolism and oxidative defense in sunflower under water deficit stress. Physiol. Mol. Biol. Plants 2020, 26, 489–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, H.; Xu, Y.; An, Y.; Wang, L. Effect of 5-Aminolevulinic Acid (5-ALA) on leaf chlorophyll fast fluorescence characteristics and mineral element content of buxus megistophylla grown along urban roadsides. Horticulturae 2021, 7, 95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, D.; Ding, H.; Wang, C.; Qin, H.; Han, Q.; Hou, J.; Lu, H.; Xie, Y.; Guo, T. Alleviation of drought stress by hydrogen sulfide is partially related to the abscisic acid signaling pathway in wheat. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0163082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, Z.; Xue, S.; Luo, Y.; Tian, B.; Fang, H.; Li, H.; Pei, Y. Hydrogen sulfide interacting with abscisic acid in stomatal regulation responses to drought stress in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2013, 62, 41–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, L.; Song, F.; Guo, J.; Zhu, X.; Liu, S.; Liu, F.; Li, X. Nano-ZnO-induced drought tolerance is associated with melatonin synthesis and metabolism in maize. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waqas Mazhar, M.; Ishtiaq, M.; Hussain, I.; Parveen, A.; Hayat Bhatti, K.; Azeem, M.; Thind, S.; Ajaib, M.; Maqbool, M.; Sardar, T.; et al. Seed nano-priming with Zinc Oxide nanoparticles in rice mitigates drought and enhances agronomic profile. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0264967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moshirian Farahi, S.M.; Taghavizadeh Yazdi, M.E.; Einafshar, E.; Akhondi, M.; Ebadi, M.; Azimipour, S.; Mahmoodzadeh, H.; Iranbakhsh, A. The effects of titanium dioxide (TiO2) nanoparticles on physiological, biochemical, and antioxidant properties of Vitex plant (Vitex agnus-Castus L). Heliyon 2023, 9, e22144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avendaño, V.A.; Sampedro-Guerrero, J.; Gómez-Cadenas, A.; Clausell-Terol, C. Modern approaches to enhancing abiotic stress tolerance using phytoprotectants: A focus on encapsulated proline. J. Plant Physiol. 2025, 315, 154602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, C.; Ling, Q. Functions of autophagy in chloroplast protein degradation and homeostasis. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 993215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yanagisawa, M.; Chuong, S.D.X. Chloroplast envelopes play a role in the formation of autophagy-related structures in plants. Plants 2023, 12, 443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buet, A.; Costa, M.L.; Martinez, D.E.; Guiamet, J.J. Chloroplast protein degradation in senescing leaves: Proteases and lytic compartments. Front. Plant Sci. 2019, 10, 747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodriguez-Concepcion, M.; D’Andrea, L.; Pulido, P. Control of plastidial metabolism by the Clp protease complex. J. Exp. Bot. 2018, 70, 2049–2058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, B.; Liu, G.; Wang, Y.; Wei, Y.; Shi, H. Overexpression of banana ATG8f modulates drought stress resistance in Arabidopsis. Biomolecules 2019, 9, 814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agbemafle, W.; Wong, M.M.; Bassham, D.C. Transcriptional and post-translational regulation of plant autophagy. J. Exp. Bot. 2023, 74, 6006–6022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hickey, K.; Wood, M.; Sexton, T.; Sahin, Y.; Nazarov, T.; Fisher, J.; Sanguinet, K.A.; Cousins, A.; Kirchhoff, H.; Smertenko, A. Drought tolerance strategies and autophagy in resilient wheat genotypes. Cells 2022, 11, 1765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, J.; Bassham, D.C. Autophagy during drought: Function, regulation, and potential application. Plant J. 2022, 109, 390–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Category of Effects | Specific Affected Phenomena | Direct/Indirect Effect |

|---|---|---|

| Chloroplast Ultrastructure | Reduced volume, membrane rupture, disorganized thylakoids | Direct effect |

| Stroma alterations | Decrease in starch grains, increase in lytic vesicles | Direct effect |

| Chlorophyll degradation | Reduced Chl a/b | Indirect effect |

| Carotenoid changes | Increase in xanthophylls/overall decline | Mainly indirect effect |

| PSII damage | D1 oxidation, decreased Fv/Fm | Indirect effect |

| PSI inhibition | Reduced Fd/NADP+ | Indirect effect |

| Increased NPQ | Enhanced energy dissipation | Indirect effect |

| Membrane lipid changes | Decrease in MGDG, increased saturation | Direct effect |

| Lipid peroxidation | Increased MDA | Indirect/mixed effect |

| Feature | Normal Conditions | Drought Conditions |

|---|---|---|

| Chloroplast morphology | Ellipsoidal and structurally intact | Irregular shape with reduced volume |

| Thylakoid lamellae | Well-organized with distinct grana | Disrupted or swollen; grana disintegration |

| Outer membrane | Intact double-membrane structure | Constricted or ruptured; increased permeability |

| Stroma | Rich in starch granules; few osmotic vesicles | Reduced starch granules; accumulation of small vesicles |

| Parameter | Normal Conditions | Drought Conditions |

|---|---|---|

| Chlorophyll content | Stable levels with a normal a/b ratio | Total content decreases; a/b ratio becomes imbalanced |

| Carotenoids | Moderate levels with normal photoprotective activity | Xanthophylls increase, but overall carotenoid content declines |

| Photosystem II (PSII) | D1 protein remains stable; Fv/Fm at normal level | D1 protein damaged; Fv/Fm significantly reduced |

| Photosystem I (PSI) | Smooth electron transport; active reduction of Fd and NADP+ | Electron transport impeded; reduced capacity of Fd and NADP+ |

| Energy dissipation (NPQ) | Maintained at basal level | NPQ enhanced, improving photoprotective capacity |

| Parameter | Normal Conditions | Drought Conditions |

|---|---|---|

| Fatty acid composition | Higher proportion of unsaturated fatty acids | Increased saturated fatty acids; decreased unsaturated fatty acids |

| Glycolipids (MGDG, DGDG) | Stable content supporting thylakoid stacking | Decreased levels; destabilization of photosystem complexes |

| Signaling lipids (e.g., phosphatidic acid) | Low baseline levels maintaining homeostasis | Elevated levels involved in stress signaling regulation |

| Lipid peroxidation | Low peroxidation; normal MDA content | Enhanced peroxidation with substantial MDA accumulation |

| Component Type | Major Members | Functional Roles |

|---|---|---|

| Enzymatic antioxidant | SOD, APX, CAT, GR | Eliminate O2− and H2O2; maintain the ASA–GSH cycle |

| Non-enzymatic antioxidants | ASA, GSH, tocopherols, carotenoids, flavonoids | Scavenge 1O2 and ·OH; dissipate excess excitation energy |

| Cooperative mechanisms | ASA–GSH cycle, ROS signaling regulation | Balance ROS scavenging and signal transduction |

| Lipid peroxidation | Low level, normal MDA content | Enhanced peroxidation and substantial MDA accumulation |

| Regulators | Primary Effects | Features |

|---|---|---|

| Melatonin | Enhances antioxidant enzyme activities and maintains thylakoid membrane integrity | Scavenges ROS and delays photosystem damage |

| ALA (5-aminolevulinic acid) | Promotes chlorophyll synthesis and accelerates D1 protein repair | Stabilizes PSII and improves photosynthetic rate |

| H2S (Hydrogen sulfide) | Increases membrane lipid unsaturation and reduces MDA accumulation | Mitigates lipid peroxidation and interacts with ABA signaling |

| ZnO/TiO2 nanoparticles | Enhances pigment stability and promotes electron transport | Improves light-harvesting efficiency and activates the antioxidant system |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wang, S.; Ma, Q.; Li, C.; Zhang, S.; Liu, X. Chloroplast Responses to Drought: Integrative Mechanisms and Mitigation Strategies. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 11872. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262411872

Wang S, Ma Q, Li C, Zhang S, Liu X. Chloroplast Responses to Drought: Integrative Mechanisms and Mitigation Strategies. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2025; 26(24):11872. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262411872

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Sanjiao, Qinghua Ma, Chen Li, Sihan Zhang, and Xiaomin Liu. 2025. "Chloroplast Responses to Drought: Integrative Mechanisms and Mitigation Strategies" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 26, no. 24: 11872. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262411872

APA StyleWang, S., Ma, Q., Li, C., Zhang, S., & Liu, X. (2025). Chloroplast Responses to Drought: Integrative Mechanisms and Mitigation Strategies. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 26(24), 11872. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262411872