Bifunctional BODIPY-Clioquinol Copper Chelator with Multiple Anti-AD Properties

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

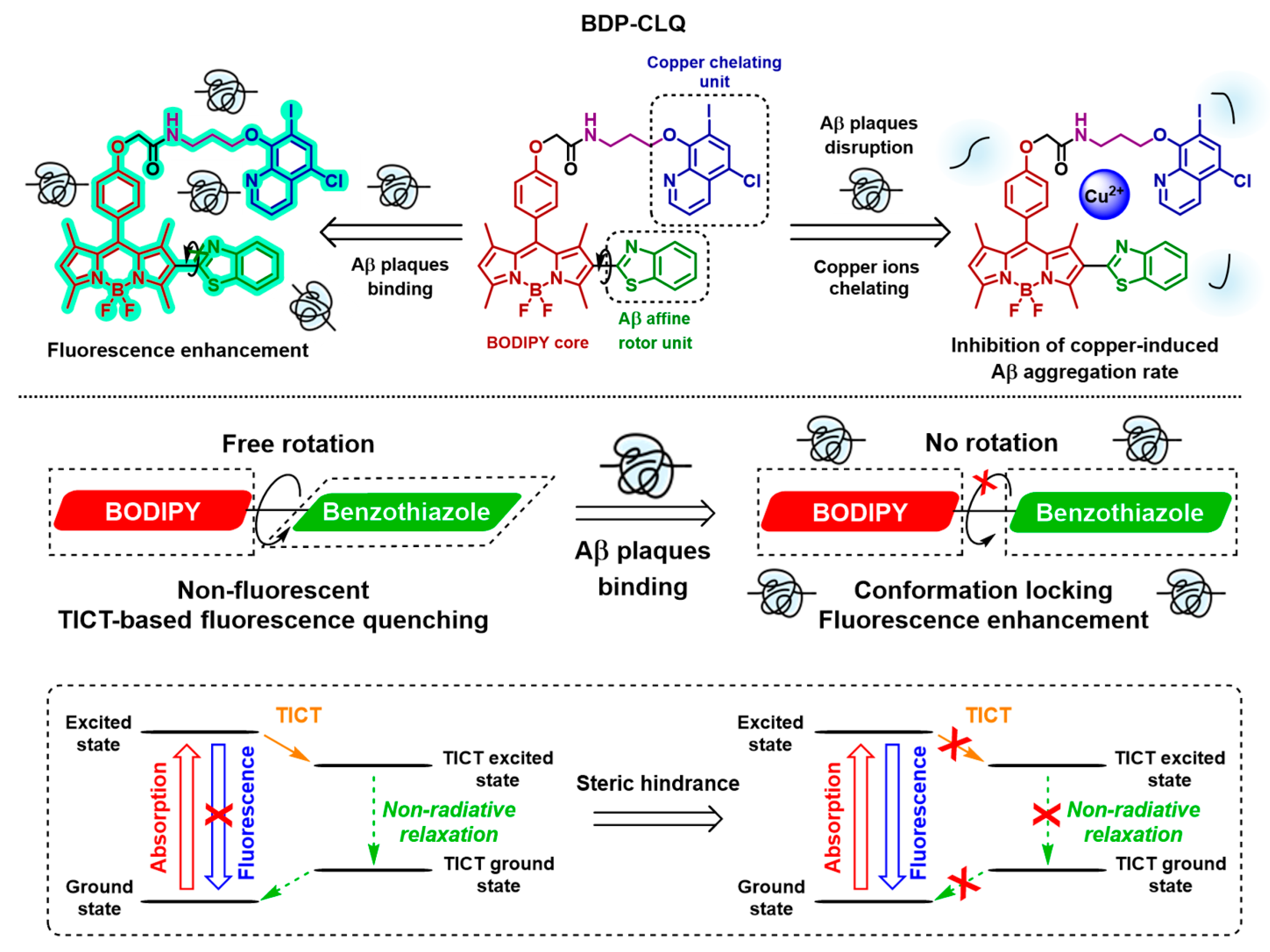

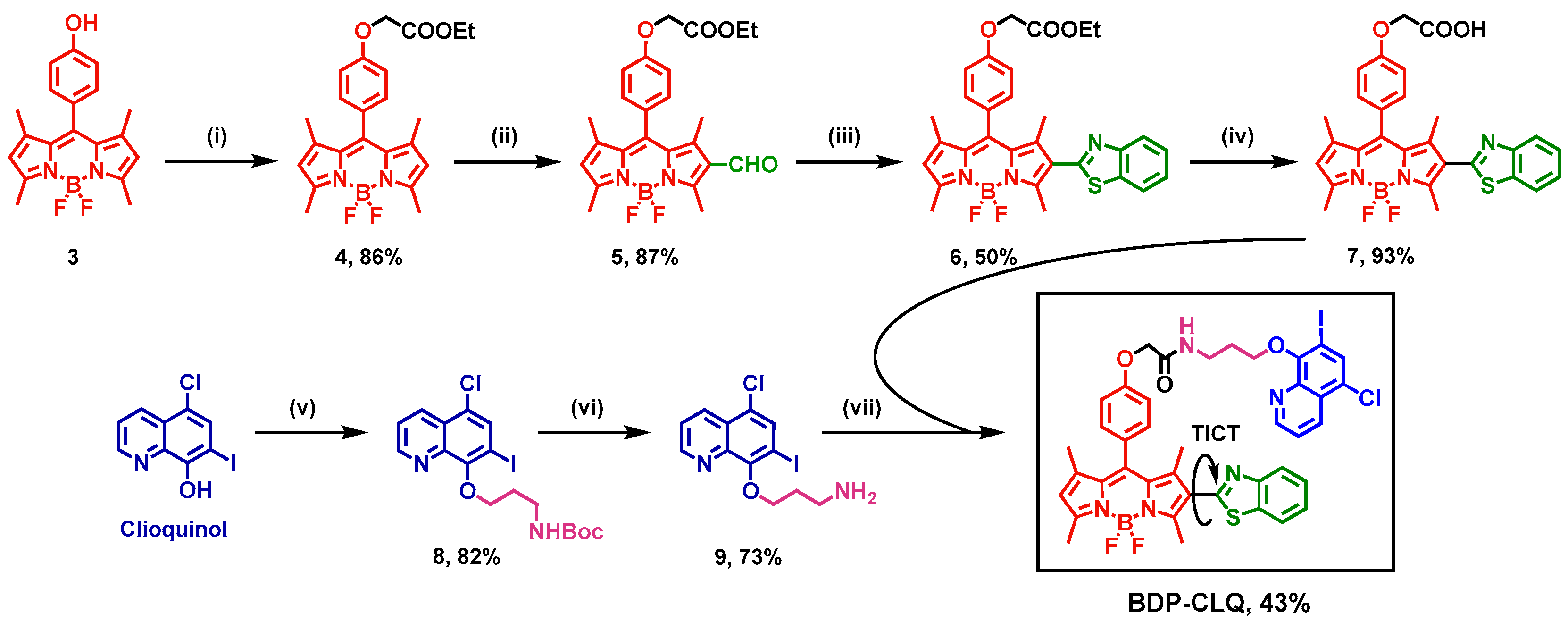

2.1. Design of BDP-CLQ

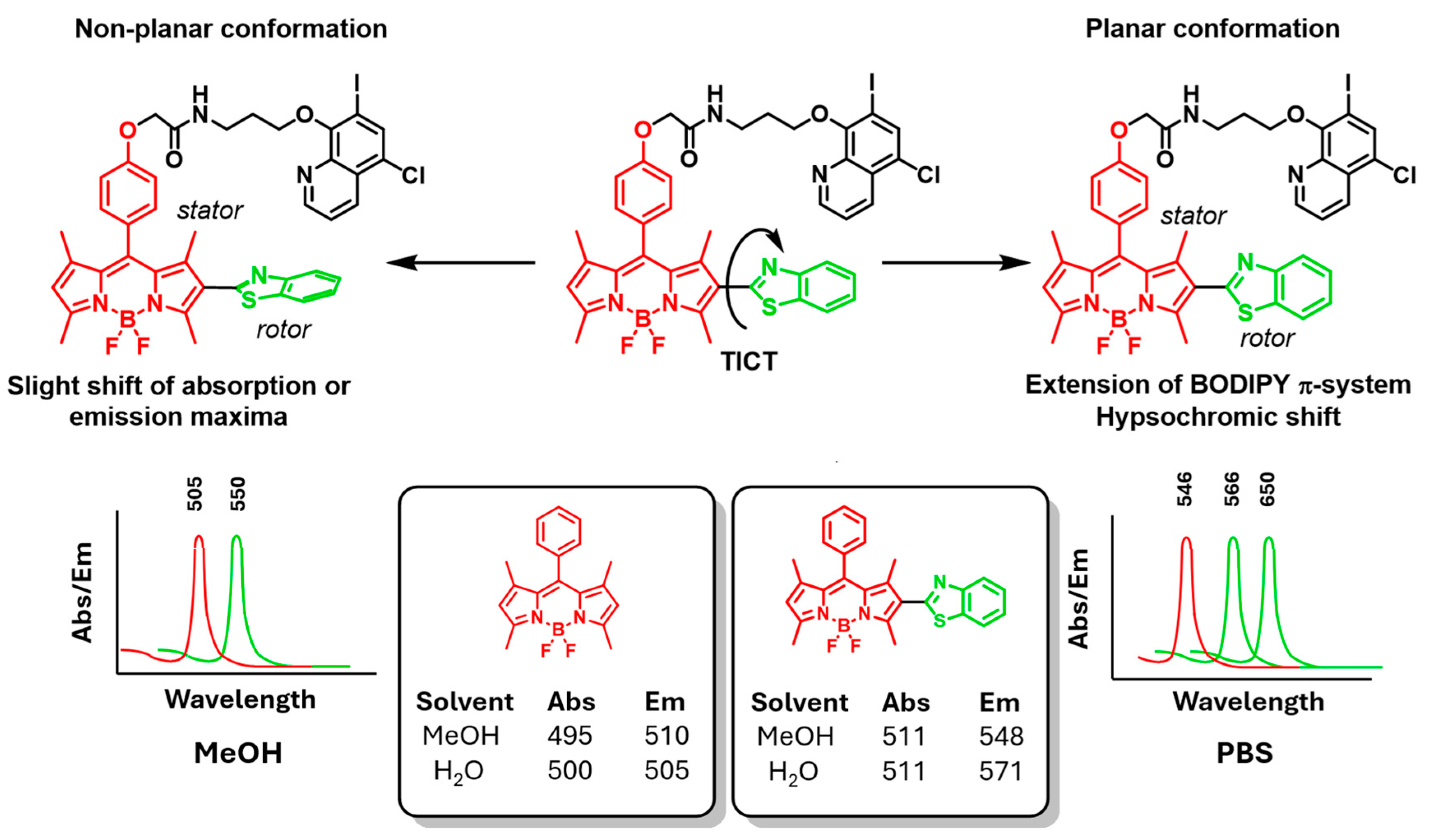

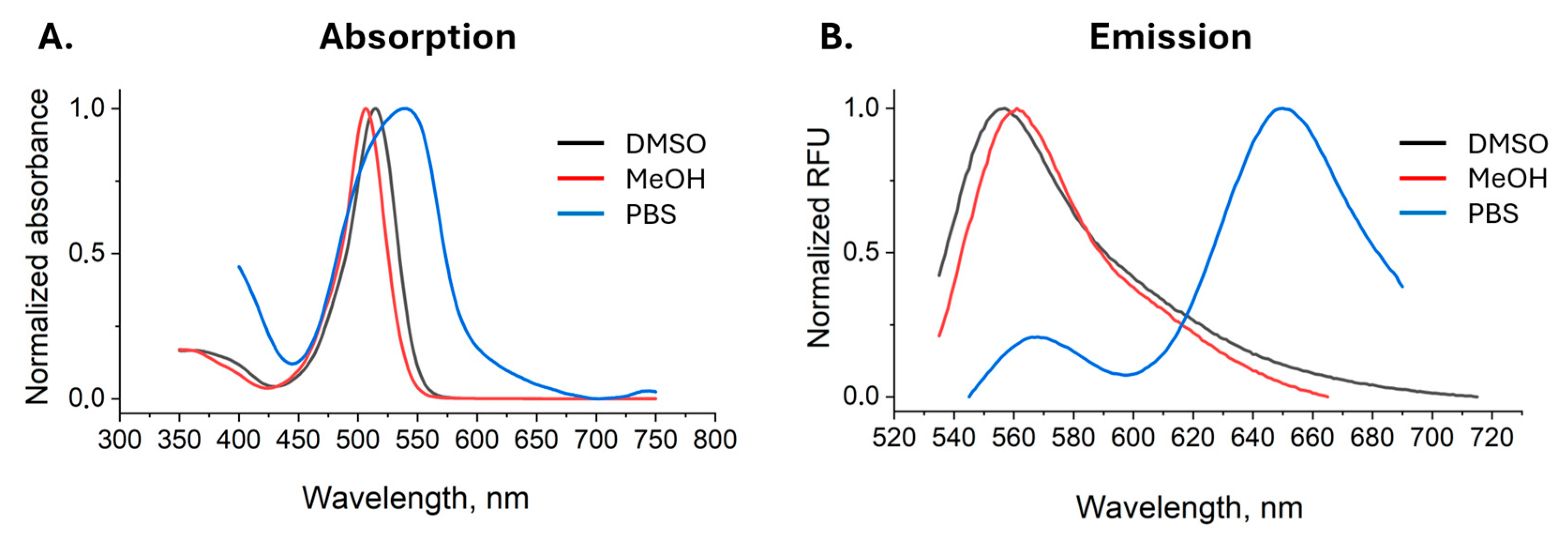

2.2. Photophysical Properties of BDP-CLQ

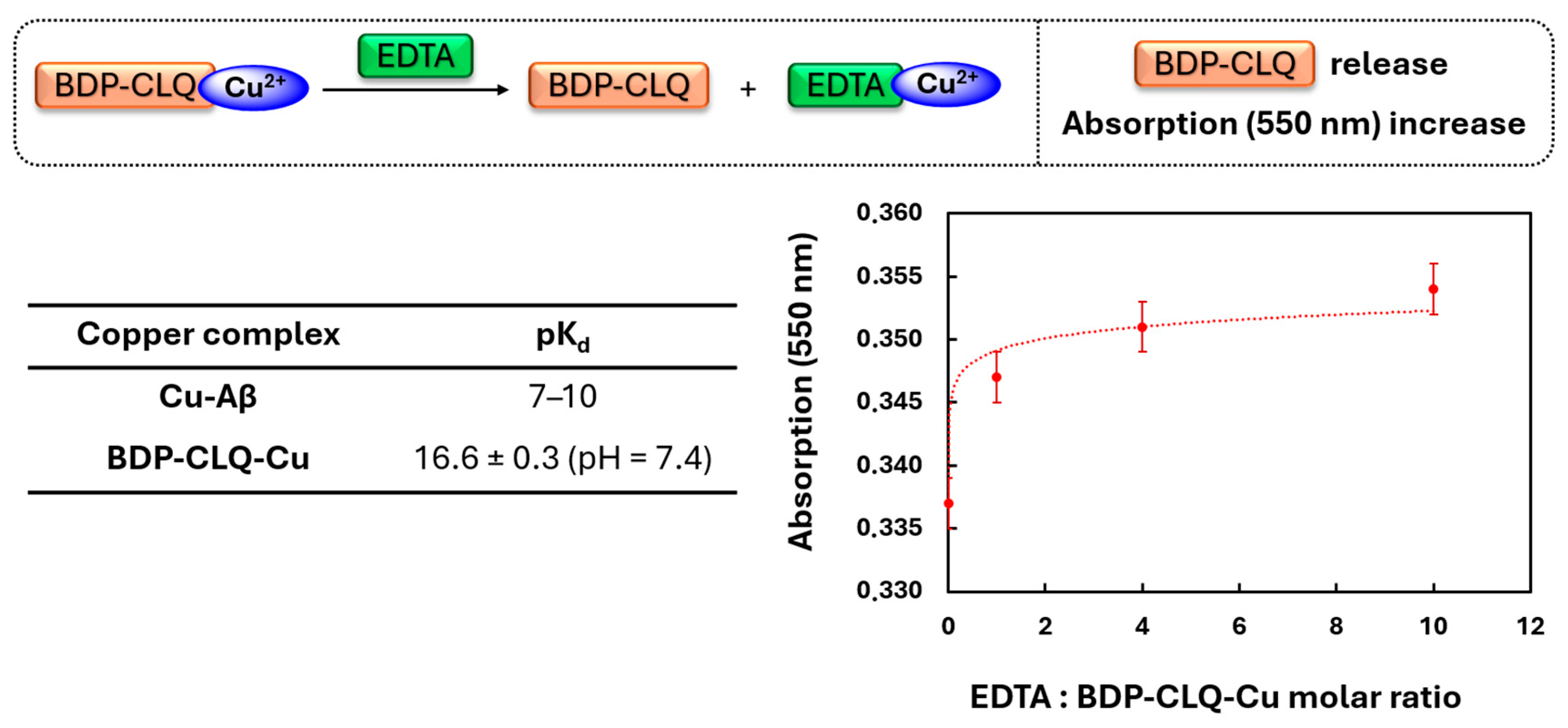

2.3. Copper-Chelating Properties of BDP-CLQ

2.4. BDP-CLQ Cytotoxicity Measurement

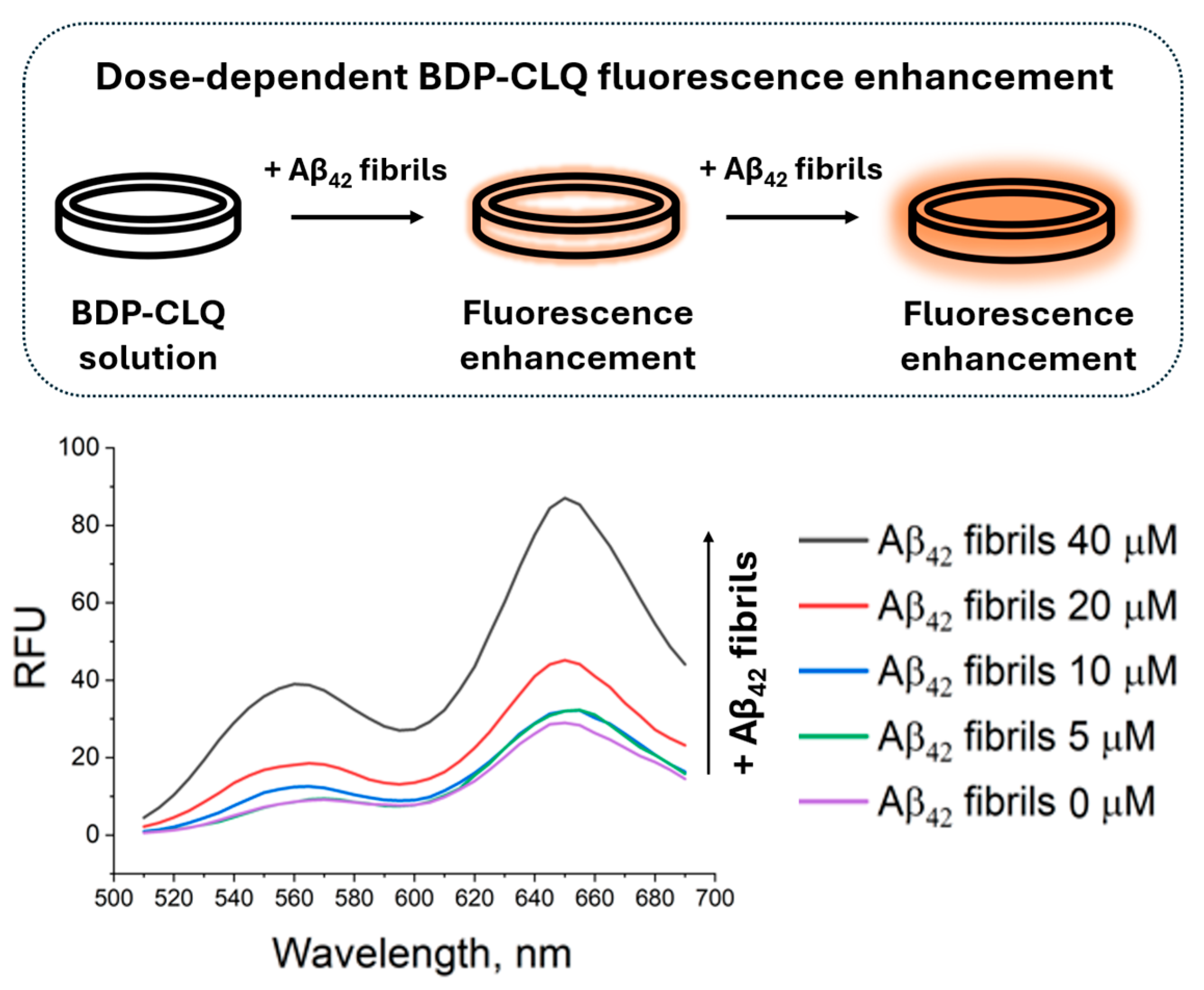

2.5. Fluorescence Enhancement of BDP-CLQ upon Incubation with Beta Amyloid (Aβ42) Fibrils

2.6. Binding Affinity of BDP-CLQ Toward Aβ42 Aggregates

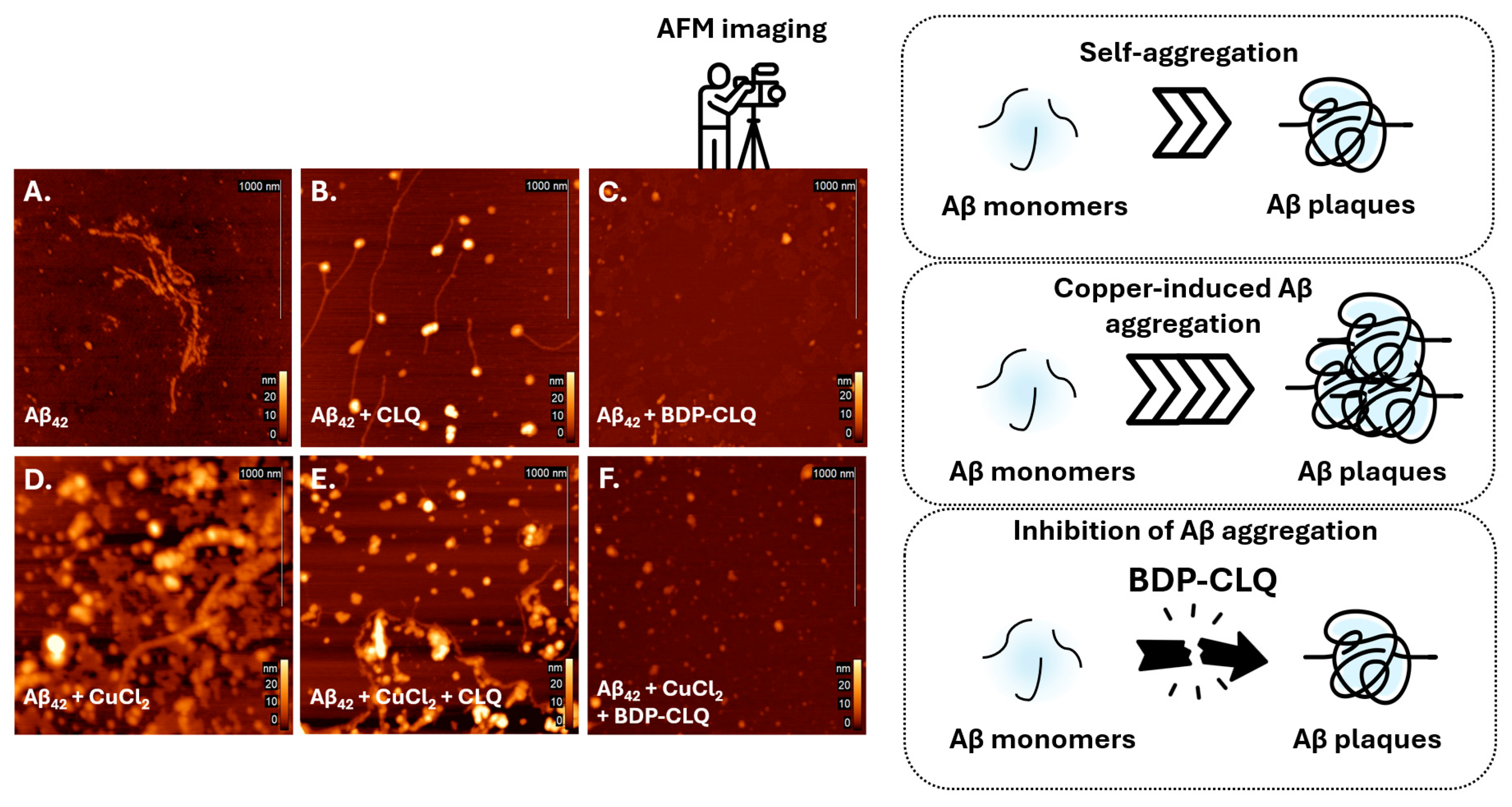

2.7. Inhibition of Aβ42 Aggregation with BDP-CLQ

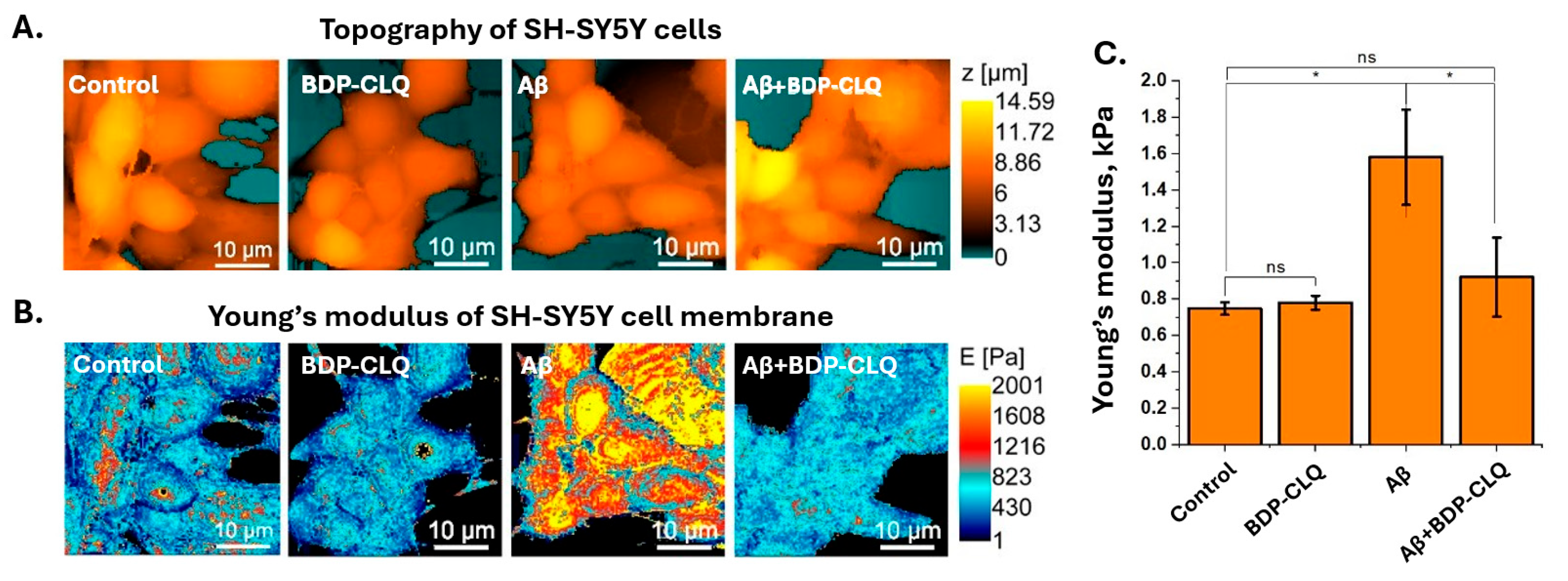

2.8. The Investigation of BDP-CLQ Impact on Mechanical Properties of Aβ42-Affected Neuronal Cells

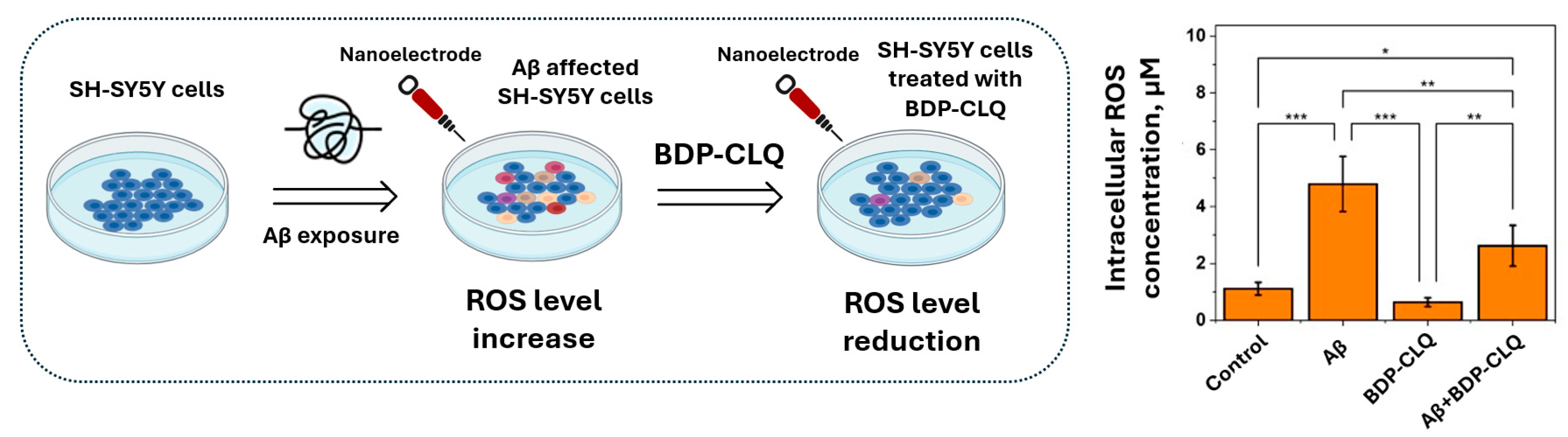

2.9. The Determination of BDP-CLQ Antioxidant Activity via Reduction in Intracellular Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS) Concentration

2.10. In Vivo Aβ Aggregates Detection by BDP-CLQ

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Synthesis

4.2. Absorption and Emission Spectra of BDP-CLQ

4.3. Preparation of Aβ42 Samples

4.4. Fluorescence Enhancement of BDP-CLQ Solution upon Incubation with Aβ42 Fibrils

4.5. Stoichiometry of BDP-CLQ-Cu Complex Determination

4.6. Stability Constant of BDP-CLQ-Cu Complex Determination

4.7. The Saturation Binding Affinity Assay of BDP-CLQ Toward Aβ42 Aggregates

4.8. The Determination of BDP-CLQ Binding Constant Toward Aβ42 Aggregates by Isothermal Titration Calorimetry

4.9. The Effects of BDP-CLQ on Copper-Induced Aβ42 Aggregation

4.10. Cytotoxicity Assay

4.11. Scanning Ion Conductance Microscopy (SICM)

4.12. Amperometric Intracellular ROS Level Measurement in SH-SY5Y Cells

4.13. In Vivo Aβ Plaques Visualization with BDP-CLQ by In Vivo Imaging System (IVIS)

4.14. Biodistribution Assay

4.15. Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

References

- Li, X.; Feng, X.; Sun, X.; Hou, N.; Han, F.; Liu, Y. Global, Regional, and National Burden of Alzheimer’s Disease and Other Dementias, 1990–2019. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2022, 14, 937486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Athar, T.; Al Balushi, K.; Khan, S.A. Recent Advances on Drug Development and Emerging Therapeutic Agents for Alzheimer’s Disease. Mol. Biol. Rep. 2021, 48, 5629–5645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cho, H.-J.; Sharma, A.K.; Zhang, Y.; Gross, M.L.; Mirica, L.M. A Multifunctional Chemical Agent as an Attenuator of Amyloid Burden and Neuroinflammation in Alzheimer’s Disease. ACS Chem. Neurosci. 2020, 11, 1471–1481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Charissopoulos, E.; Pontiki, E. Targeting Metal Imbalance and Oxidative Stress in Alzheimer’s Disease with Novel Multifunctional Compounds. Molecules 2025, 30, 3512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, A.; Pachauri, V.; Flora, S.J.S. Advances in Multi-Functional Ligands and the Need for Metal-Related Pharmacology for the Management of Alzheimer Disease. Front. Pharmacol. 2018, 9, 1247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mot, A.I.; Wedd, A.G.; Sinclair, L.; Brown, D.R.; Collins, S.J.; Brazier, M.W. Metal Attenuating Therapies in Neurodegenerative Disease. Expert Rev. Neurother. 2011, 11, 1717–1745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.; Na, C.; Han, J.; Lim, M.H. Methods for Analyzing the Coordination and Aggregation of Metal–Amyloid-β. Metallomics 2023, 15, mfac102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zubčić, K.; Hof, P.R.; Šimić, G.; Jazvinšćak Jembrek, M. The Role of Copper in Tau-Related Pathology in Alzheimer’s Disease. Front. Mol. Neurosci. 2020, 13, 572308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moynier, F.; Le Borgne, M.; Lahoud, E.; Mahan, B.; Mouton-Ligier, F.; Hugon, J.; Paquet, C. Copper and Zinc Isotopic Excursions in the Human Brain Affected by Alzheimer’s Disease. Alzheimers Dement. Diagn. Assess. Dis. Monit. 2020, 12, e12112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ejaz, H.W.; Wang, W.; Lang, M. Copper Toxicity Links to Pathogenesis of Alzheimer’s Disease and Therapeutics Approaches. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 7660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.K.; Balendra, V.; Obaid, A.A.; Esposto, J.; Tikhonova, M.A.; Gautam, N.K.; Poeggeler, B. Copper-Mediated β-Amyloid Toxicity and Its Chelation Therapy in Alzheimer’s Disease. Metallomics 2022, 14, mfac018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baldari, S.; Di Rocco, G.; Toietta, G. Current Biomedical Use of Copper Chelation Therapy. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 1069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krishnan, H.S.; Bernard-Gauthier, V.; Placzek, M.S.; Dahl, K.; Narayanaswami, V.; Livni, E.; Chen, Z.; Yang, J.; Collier, T.L.; Ran, C.; et al. Metal Protein-Attenuating Compound for PET Neuroimaging: Synthesis and Preclinical Evaluation of [11 C]PBT2. Mol. Pharm. 2018, 15, 695–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bareggi, S.R.; Cornelli, U. Clioquinol: Review of Its Mechanisms of Action and Clinical Uses in Neurodegenerative Disorders. CNS Neurosci. Ther. 2012, 18, 41–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ritchie, C.W.; Bush, A.I.; Mackinnon, A.; Macfarlane, S.; Mastwyk, M.; MacGregor, L.; Kiers, L.; Cherny, R.; Li, Q.-X.; Tammer, A.; et al. Metal-Protein Attenuation with Iodochlorhydroxyquin (Clioquinol) Targeting Aβ Amyloid Deposition and Toxicity in Alzheimer Disease. Arch. Neurol. 2003, 60, 1685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camargo, M.L.M.; Farias, A.B.; Bertazzo, G.B.; Gomes, R.N.; Gomes, K.S.; Bosquetti, L.M.; Takada, S.H.; Braga, F.C.; Augusto, C.C.; Batista, B.L.; et al. Novel Copper Chelators Enhance Spatial Memory and Biochemical Outcomes in Alzheimer’s Disease Model. ACS Chem. Neurosci. 2025, 16, 3267–3281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, X.; Schimmer, A. The Toxicology of Clioquinol. Toxicol. Lett. 2008, 182, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Li, T.; Zhang, P.; Li, X.; Lu, L.; Sun, Y.; Zhang, B.; Allen, S.; White, L.; Phillips, J.; et al. Discovery of Novel Hybrids Containing Clioquinol−1-Benzyl-1,2,3,6-Tetrahydropyridine as Multi-Target-Directed Ligands (MTDLs) Against Alzheimer’s Disease. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2022, 244, 114841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, B.; Jiang, H. Synthesis and Bio-Activities of Bifunctional Tetrahydrosalen Cu (II) Chelators with Potential Efficacy in Alzheimer’s Disease Therapy. J. Inorg. Biochem. 2024, 259, 112636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krasnovskaya, O.; Kononova, A.; Erofeev, A.; Gorelkin, P.; Majouga, A.; Beloglazkina, E. Aβ-Targeting Bifunctional Chelators (BFCs) for Potential Therapeutic and PET Imaging Applications. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 24, 236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krasnovskaya, O.; Abramchuk, D.; Vaneev, A.; Gorelkin, P.; Abakumov, M.; Timoshenko, R.; Kuzmichev, I.; Chmelyuk, N.; Vadehina, V.; Kuanaeva, R.; et al. Bifunctional Copper Chelators Capable of Reducing Aβ Aggregation and Aβ-Induced Oxidative Stress. ACS Omega 2024, 9, 43376–43384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Su, D.; Diao, W.; Li, J.; Pan, L.; Zhang, X.; Wu, X.; Mao, W. Strategic Design of Amyloid-β Species Fluorescent Probes for Alzheimer’s Disease. ACS Chem. Neurosci. 2022, 13, 540–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abramchuk, D.; Voskresenskaya, A.; Kuzmichev, I.; Erofeev, A.; Gorelkin, P.; Abakumov, M.; Beloglazkina, E.; Krasnovskaya, O. BODIPY in Alzheimer’s Disease Diagnostics: A Review. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2024, 276, 116682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dzyuba, S.V. BODIPY Dyes as Probes and Sensors to Study Amyloid-β-Related Processes. Biosensors 2020, 10, 192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, M.-Y.; Chen, Q.-Y.; Yao, L.; Wang, Y.-B. Spectroscopic Study on the Interaction of Aβ42 with Di(Picolyl)Amine Derivatives and the Toxicity to SH-S5Y5 Cells. Spectrochim. Acta Part A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2015, 138, 225–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Huynh, T.T.; Cho, H.-J.; Wang, Y.-C.; Rogers, B.E.; Mirica, L.M. Amyloid β-Binding Bifunctional Chelators with Favorable Lipophilicity for 64 Cu Positron Emission Tomography Imaging in Alzheimer’s Disease. Inorg. Chem. 2021, 60, 12610–12620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, L.; Cho, H.-J.; Sen, S.; Arango, A.S.; Huynh, T.T.; Huang, Y.; Bandara, N.; Rogers, B.E.; Tajkhorshid, E.; Mirica, L.M. Amphiphilic Distyrylbenzene Derivatives as Potential Therapeutic and Imaging Agents for Soluble and Insoluble Amyloid β Aggregates in Alzheimer’s Disease. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2021, 143, 10462–10476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rana, M.; Cho, H.-J.; Arya, H.; Bhatt, T.K.; Bhar, K.; Bhatt, S.; Mirica, L.M.; Sharma, A.K. Azo-Stilbene and Pyridine–Amine Hybrid Multifunctional Molecules to Target Metal-Mediated Neurotoxicity and Amyloid-β Aggregation in Alzheimer’s Disease. Inorg. Chem. 2022, 61, 10294–10309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, H.-J.; Huynh, T.T.; Rogers, B.E.; Mirica, L.M. Design of a Multivalent Bifunctional Chelator for Diagnostic 64 Cu PET Imaging in Alzheimer’s Disease. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2020, 117, 30928–30933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Huynh, T.T.; Sun, L.; Hu, C.-H.; Wang, Y.-C.; Rogers, B.E.; Mirica, L.M. Neutral Ligands as Potential 64 Cu Chelators for Positron Emission Tomography Imaging Applications in Alzheimer’s Disease. Inorg. Chem. 2022, 61, 4778–4787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McInnes, L.E.; Noor, A.; Kysenius, K.; Cullinane, C.; Roselt, P.; McLean, C.A.; Chiu, F.C.K.; Powell, A.K.; Crouch, P.J.; White, J.M.; et al. Potential Diagnostic Imaging of Alzheimer’s Disease with Copper-64 Complexes That Bind to Amyloid-β Plaques. Inorg. Chem. 2019, 58, 3382–3395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Yang, J.; Chen, Q.; Su, J.; Shi, W.-J.; Zhang, L.; Xia, C.; Yan, J. Rotor-Tuning Boron Dipyrromethenes for Dual-Functional Imaging of Aβ Oligomers and Viscosity. ACS Appl. Bio Mater. 2022, 5, 3049–3056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, J.H.; Xu, Z.Y.; Deng, C.C.; Li, N.B.; Luo, H.Q. Rational Design of Push-Pull Fluorescent Probe with Extraordinary Polarity Sensitivity for VOCs Chromic Sensing and Trace Water Detection. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2023, 393, 134089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Chi, W.; Qiao, Q.; Tan, D.; Xu, Z.; Liu, X. Twisted Intramolecular Charge Transfer (TICT) and Twists Beyond TICT: From Mechanisms to Rational Designs of Bright and Sensitive Fluorophores. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2021, 50, 12656–12678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gharai, P.K.; Khan, J.; Mallesh, R.; Garg, S.; Saha, A.; Ghosh, S.; Ghosh, S. Vanillin Benzothiazole Derivative Reduces Cellular Reactive Oxygen Species and Detects Amyloid Fibrillar Aggregates in Alzheimer’s Disease Brain. ACS Chem. Neurosci. 2023, 14, 773–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, X.; Xu, Z.; Cole, J.M. Molecular Design of UV–Vis Absorption and Emission Properties in Organic Fluorophores: Toward Larger Bathochromic Shifts, Enhanced Molar Extinction Coefficients, and Greater Stokes Shifts. J. Phys. Chem. C 2013, 117, 16584–16595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padmanabhan, G.; Becue, I.; Smith, J.B. Clioquinol. In Analytical Profiles of Drug Substances; Academic Press: New York, NY, USA, 1990; pp. 57–90. [Google Scholar]

- Terpstra, K.; Wang, Y.; Huynh, T.T.; Bandara, N.; Cho, H.-J.; Rogers, B.E.; Mirica, L.M. Divalent 2-(4-Hydroxyphenyl)Benzothiazole Bifunctional Chelators for 64 Cu Positron Emission Tomography Imaging in Alzheimer’s Disease. Inorg. Chem. 2022, 61, 20326–20336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zawisza, I.; Rózga, M.; Bal, W. Affinity of Copper and Zinc Ions to Proteins and Peptides Related to Neurodegenerative Conditions (Aβ, APP, α-Synuclein, PrP). Coord. Chem. Rev. 2012, 256, 2297–2307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, C.; Han, J.; Liang, F.; Zhu, M.; Zhang, G.; James, T.D.; Wang, Z. Advances in Multi-Target Fluorescent Probes for Imaging and Analyzing Biomarkers in Alzheimer’s Disease. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2024, 517, 216002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dao, P.; Ye, F.; Liu, Y.; Du, Z.Y.; Zhang, K.; Dong, C.Z.; Meunier, B.; Chen, H. Development of Phenothiazine-Based Theranostic Compounds That Act Both as Inhibitors of β-Amyloid Aggregation and as Imaging Probes for Amyloid Plaques in Alzheimer’s Disease. ACS Chem. Neurosci. 2017, 8, 798–806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Wang, J.; Zhang, W.; Xia, Z.; Zhai, N.; Liu, G.; Wang, K.; Pan, J. Functional Bioprobe for Responsive Imaging and Inhibition of Amyloid-β Oligomer Based on Curcuminoid Scaffold. J. Lumin. 2021, 238, 118218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teoh, C.L.; Su, D.; Sahu, S.; Yun, S.-W.; Drummond, E.; Prelli, F.; Lim, S.; Cho, S.; Ham, S.; Wisniewski, T.; et al. Chemical Fluorescent Probe for Detection of Aβ Oligomers. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2015, 137, 13503–13509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Wang, X.; Xu, D.; Zhang, H.; Chan, H.-N.; Zhan, Z.; Jia, S.; Song, Q.; Song, G.; Li, H.-W.; et al. Multifunctional Theranostic Carbazole-Based Cyanine for Real-Time Imaging of Amyloid-β and Therapeutic Treatment of Multiple Pathologies in Alzheimer’s Disease. J. Mater. Chem. B 2023, 11, 4865–4873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muthuraj, B.; Layek, S.; Balaji, S.N.; Trivedi, V.; Iyer, P.K. Multiple Function Fluorescein Probe Performs Metal Chelation, Disaggregation, and Modulation of Aggregated Aβ and Aβ-Cu Complex. ACS Chem. Neurosci. 2015, 6, 1880–1891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, L.; Han, Y.; He, C.; Huang, X.; Wang, Y. Disaggregation Ability of Different Chelating Molecules on Copper Ion-Triggered Amyloid Fibers. J. Phys. Chem. B 2014, 118, 9298–9305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, K.; Kaur, A.; Goyal, B.; Goyal, D. Harnessing the Therapeutic Potential of Peptides for Synergistic Treatment of Alzheimer’s Disease by Targeting Aβ Aggregation, Metal-Mediated Aβ Aggregation, Cholinesterase, Tau Degradation, and Oxidative Stress. ACS Chem. Neurosci. 2024, 15, 2545–2564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canale, C.; Oropesa-Nuñez, R.; Diaspro, A.; Dante, S. Amyloid and Membrane Complexity: The Toxic Interplay Revealed by AFM. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 2018, 73, 82–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hindo, S.S.; Mancino, A.M.; Braymer, J.J.; Liu, Y.; Vivekanandan, S.; Ramamoorthy, A.; Lim, M.H. Small Molecule Modulators of Copper-Induced Aβ Aggregation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009, 131, 16663–16665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tahmasebinia, F.; Emadi, S. Effect of Metal Chelators on the Aggregation of Beta-Amyloid Peptides in the Presence of Copper and Iron. BioMetals 2017, 30, 285–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, M.E.; Kan, H.-M.; Baas, P.W.; Erisir, A.; Glabe, C.G.; Bloom, G.S. Tau-Dependent Microtubule Disassembly Initiated by Prefibrillar β-Amyloid. J. Cell Biol. 2006, 175, 541–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drews, A. Investigating How Aβ and ASynuclein Oligomers Initially Demage Neuronal Cells. Biophys. J. 2014, 106, 548a. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, F.; He, J.; Manandhar, P.; Yang, Y.; Liu, P.; Gu, N. Gauging Surface Charge Distribution of Live Cell Membrane by Ionic Current Change Using Scanning Ion Conductance Microscopy. Nanoscale 2021, 13, 19973–19984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suchalko, O.; Timoshenko, R.; Vaneev, A.; Kolmogorov, V.; Savin, N.; Klyachko, N.; Barykin, E.; Gorbacheva, L.; Maksimov, G.; Kozin, S.; et al. Cell Stiffness and ROS Level Alterations in Living Neurons Mediated by β-Amyloid Oligomers Measured by Scanning Ion-Conductance Microscopy. Microsc. Microanal. 2021, 27, 500–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolmogorov, V.S.; Erofeev, A.S.; Barykin, E.P.; Timoshenko, R.V.; Lopatukhina, E.V.; Kozin, S.A.; Gorbacheva, L.R.; Salikhov, S.V.; Klyachko, N.L.; Mitkevich, V.A.; et al. Scanning Ion-Conductance Microscopy for Studying β-Amyloid Aggregate Formation on Living Cell Surfaces. Anal. Chem. 2023, 95, 15943–15949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adnan, M.; Siddiqui, A.J.; Bardakci, F.; Surti, M.; Badraoui, R.; Patel, M. Neuroprotective Potential of Quercetin in Alzheimer’s Disease: Targeting Oxidative Stress, Mitochondrial Dysfunction, and Amyloid-β Aggregation. Front. Pharmacol. 2025, 16, 1593264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, D.; Grewal, A.K.; Almasoudi, S.H.; Almehmadi, A.H.; Alsfouk, B.A.; Kumar, A.; Singh, V.; Alexiou, A.; Papadakis, M.; Welson, N.N.; et al. Neuroprotective Effect of Tozasertib in Streptozotocin-Induced Alzheimer’s Mice Model. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 28963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alqahtani, S.M.; Al-Kuraishy, H.M.; Al-Gareeb, A.I.; Alexiou, A.; Fawzy, M.N.; Papadakis, M.; Al-Botaty, B.M.; Alruwaili, M.; El-Saber Batiha, G. The Neuroprotective Role of Humanin in Alzheimer’s Disease: The Molecular Effects. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2025, 998, 177510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Min, N.; Park, H.; Hong, T.; An, G.; Song, G.; Lim, W. Developmental Toxicity of Prometryn Induces Mitochondrial Dysfunction, Oxidative Stress, and Failure of Organogenesis in Zebrafish (Danio rerio). J. Hazard. Mater. 2023, 443, 130202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walia, V.; Kaushik, D.; Mittal, V.; Kumar, K.; Verma, R.; Parashar, J.; Akter, R.; Rahman, M.H.; Bhatia, S.; Al-Harrasi, A.; et al. Delineation of Neuroprotective Effects and Possible Benefits of AntioxidantsTherapy for the Treatment of Alzheimer’s Diseases by Targeting Mitochondrial-Derived Reactive Oxygen Species: Bench to Bedside. Mol. Neurobiol. 2022, 59, 657–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatt, S.; Puli, L.; Patil, C.R. Role of Reactive Oxygen Species in the Progression of Alzheimer’s Disease. Drug Discov. Today 2021, 26, 794–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krasnovskaya, O.O.; Akasov, R.A.; Spector, D.V.; Pavlov, K.G.; Bubley, A.A.; Kuzmin, V.A.; Kostyukov, A.A.; Khaydukov, E.V.; Lopatukhina, E.V.; Semkina, A.S.; et al. Photoinduced Reduction of Novel Dual-Action Riboplatin Pt(IV) Prodrug. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2023, 15, 12882–12894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spector, D.V.; Pavlov, K.G.; Akasov, R.A.; Vaneev, A.N.; Erofeev, A.S.; Gorelkin, P.V.; Nikitina, V.N.; Lopatukhina, E.V.; Semkina, A.S.; Vlasova, K.Y.; et al. Pt(IV) Prodrugs with Non-Steroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs in the Axial Position. J. Med. Chem. 2022, 65, 8227–8244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krasnovskaya, O.O.; Guk, D.A.; Naumov, A.E.; Nikitina, V.N.; Semkina, A.S.; Vlasova, K.Y.; Pokrovsky, V.; Ryabaya, O.O.; Karshieva, S.S.; Skvortsov, D.A.; et al. Novel Copper-Containing Cytotoxic Agents Based on 2-Thioxoimidazolones. J. Med. Chem. 2020, 63, 13031–13063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Z.; Wang, Y.; Li, W.; Mao, F.; Sun, Y.; Huang, L.; Li, X. Design, Synthesis, and Evaluation of Multitarget-Directed Selenium-Containing Clioquinol Derivatives for the Treatment of Alzheimer’s Disease. ACS Chem. Neurosci. 2014, 5, 952–962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Q.; Zhu, H.; Lv, C.; Zhu, Z.; Cui, H.; Fan, Z.; Sun, J.; Huang, Z.; Shi, P. Clioquinol Rescues Yeast Cells from Aβ42 Toxicity via the Inhibition of Oxidative Damage. Biotechnol. J. 2024, 19, 2300662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hou, S.S.; Yang, J.; Lee, J.H.; Kwon, Y.; Calvo-Rodriguez, M.; Bao, K.; Ahn, S.; Kashiwagi, S.; Kumar, A.T.N.; Bacskai, B.J.; et al. Near-Infrared Fluorescence Lifetime Imaging of Amyloid-β Aggregates and Tau Fibrils through the Intact Skull of Mice. Nat. Biomed. Eng. 2023, 7, 270–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, M.S.; Hussain, M.H. Multi-Target Drug Design in Alzheimer’s Disease Treatment: Emerging Technologies, Advantages, Challenges, and Limitations. Pharmacol. Res. Perspect. 2025, 13, e70131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, M.; Gabr, M. Multitarget Therapeutic Strategies for Alzheimer’s Disease. Neural Regen. Res. 2019, 14, 437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turgutalp, B.; Kizil, C. Multi-Target Drugs for Alzheimer’s Disease. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 2024, 45, 628–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cacabelos, R.; Martínez-Iglesias, O.; Cacabelos, N.; Carrera, I.; Corzo, L.; Naidoo, V. Therapeutic Options in Alzheimer’s Disease: From Classic Acetylcholinesterase Inhibitors to Multi-Target Drugs with Pleiotropic Activity. Life 2024, 14, 1555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Wang, H.; Li, X.; Dong, S.; Liu, W.; Gong, Q.; Wang, T.; Tang, Y.; Zhu, J.; Li, J.; et al. Discovery of Novel Propargylamine-Modified 4-Aminoalkyl Imidazole Substituted Pyrimidinylthiourea Derivatives as Multifunctional Agents for the Treatment of Alzheimer’s Disease. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2018, 143, 33–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.; Zhang, H.; Wang, Y.; Liu, W.; Yin, G.; Wang, D.; Li, J.; Shi, T.; Wang, Z. Design, Synthesis, and Biological Evaluation of Carbamate Derivatives of N-Salicyloyl Tryptamine as Multifunctional Agents for the Treatment of Alzheimer’s Disease. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2022, 229, 114044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bubley, A.; Erofeev, A.; Gorelkin, P.; Beloglazkina, E.; Majouga, A.; Krasnovskaya, O. Tacrine-Based Hybrids: Past, Present, and Future. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 1717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tan, R.-X.; Li, W.-H.; Pang, J.-M.; Zhong, S.-M.; Huang, X.-Y.; Deng, J.-Z.; Zhou, L.-Y.; Wu, J.-Q.; Wang, X.-Q. Design, Synthesis, and Evaluation of 2,2′-Bipyridyl Derivatives as Bifunctional Agents against Alzheimer’s Disease. Mol. Divers. 2024, 28, 1225–1238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rana, M.; Terpstra, K.; Gutierrez, C.; Xu, K.; Arya, H.; Bhatt, T.K.; Mirica, L.M.; Sharma, A.K. Evaluation of Anti-Alzheimer’s Potential of Azo-Stilbene-Thioflavin-T Derived Multifunctional Molecules: Synthesis, Metal and Aβ Species Binding and Cholinesterase Activity. Chem. A Eur. J. 2025, 31, e202402748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Shi, Q.; Tian, H.; Li, Y.; Liu, Y.; Xu, Z.; Robert, A.; Liu, Q.; Meunier, B. TDMQ20, a Specific Copper Chelator, Reduces Memory Impairments in Alzheimer’s Disease Mouse Models. ACS Chem. Neurosci. 2021, 12, 140–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noor, A.; Hayne, D.J.; Lim, S.; Van Zuylekom, J.K.; Cullinane, C.; Roselt, P.D.; McLean, C.A.; White, J.M.; Donnelly, P.S. Copper Bis(Thiosemicarbazonato)-Stilbenyl Complexes That Bind to Amyloid-β Plaques. Inorg. Chem. 2020, 59, 11658–11669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Xu, D.; Ho, S.-L.; Li, H.-W.; Yang, R.; Wong, M.S. A Theranostic Agent for in Vivo Near-Infrared Imaging of β-Amyloid Species and Inhibition of β-Amyloid Aggregation. Biomaterials 2016, 94, 84–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Konar, M.; Ghosh, D.; Samanta, S.; Govindaraju, T. Combating Amyloid-Induced Cellular Toxicity and Stiffness by Designer Peptidomimetics. RSC Chem. Biol. 2022, 3, 220–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zatsepina, O.G.; Kechko, O.I.; Mitkevich, V.A.; Kozin, S.A.; Yurinskaya, M.M.; Vinokurov, M.G.; Serebryakova, M.V.; Rezvykh, A.P.; Evgen’ev, M.B.; Makarov, A.A. Amyloid-β with Isomerized Asp7 Cytotoxicity Is Coupled to Protein Phosphorylation. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 3518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walke, G.R.; Ruthstein, S. Does the ATSM-Cu(II) Biomarker Integrate into the Human Cellular Copper Cycle? ACS Omega 2019, 4, 12278–12285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mariasina, S.S.; Chang, C.; Petrova, O.A.; Efimov, S.V.; Klochkov, V.V.; Kechko, O.I.; Mitkevich, V.A.; Sergiev, P.V.; Dontsova, O.A.; Polshakov, V.I. Williams–Beuren Syndrome-Related Methyltransferase WBSCR27: Cofactor Binding and Cleavage. FEBS J. 2020, 287, 5375–5393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yaminsky, I.; Akhmetova, A.; Meshkov, G. Femtoscan Online Software and Visualization of Nano-Objecs in High-Resolution Microscopy. Nanoind. Russ. 2018, 11, 414–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarke, R.W.; Novak, P.; Zhukov, A.; Tyler, E.J.; Cano-Jaimez, M.; Drews, A.; Richards, O.; Volynski, K.; Bishop, C.; Klenerman, D. Low Stress Ion Conductance Microscopy of Sub-Cellular Stiffness. Soft Matter 2016, 12, 7953–7958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ha, C.; Ryu, J.; Park, C.B. Metal Ions Differentially Influence the Aggregation and Deposition of Alzheimer’s β-Amyloid on a Solid Template. Biochemistry 2007, 46, 6118–6125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Savin, N.; Erofeev, A.; Timoshenko, R.; Vaneev, A.; Garanina, A.; Salikhov, S.; Grammatikova, N.; Levshin, I.; Korchev, Y.; Gorelkin, P. Investigation of the Antifungal and Anticancer Effects of the Novel Synthesized Thiazolidinedione by Ion-Conductance Microscopy. Cells 2023, 12, 1666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Erofeev, A.; Gorelkin, P.; Garanina, A.; Alova, A.; Efremova, M.; Vorobyeva, N.; Edwards, C.; Korchev, Y.; Majouga, A. Novel Method for Rapid Toxicity Screening of Magnetic Nanoparticles. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 7462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Solvent | Absorption, nm | Emission, nm | Stoke’s Shift, cm−1 |

|---|---|---|---|

| MeOH | 505 | 561 | 1976.7 |

| DMSO | 513 | 555 | 1475.2 |

| PBS | 540 | 565, 650 | 819.4; 3133.9 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Abramchuk, D.S.; Krasnovskaya, O.O.; Voskresenskaya, A.S.; Vaneev, A.N.; Kuanaeva, R.M.; Mamed-Nabizade, V.V.; Kolmogorov, V.S.; Kechko, O.I.; Mitkevich, V.A.; Makarov, A.A.; et al. Bifunctional BODIPY-Clioquinol Copper Chelator with Multiple Anti-AD Properties. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 11876. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262411876

Abramchuk DS, Krasnovskaya OO, Voskresenskaya AS, Vaneev AN, Kuanaeva RM, Mamed-Nabizade VV, Kolmogorov VS, Kechko OI, Mitkevich VA, Makarov AA, et al. Bifunctional BODIPY-Clioquinol Copper Chelator with Multiple Anti-AD Properties. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2025; 26(24):11876. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262411876

Chicago/Turabian StyleAbramchuk, Daniil S., Olga O. Krasnovskaya, Alevtina S. Voskresenskaya, Alexander N. Vaneev, Regina M. Kuanaeva, Vugara V. Mamed-Nabizade, Vasilii S. Kolmogorov, Olga I. Kechko, Vladimir A. Mitkevich, Alexander A. Makarov, and et al. 2025. "Bifunctional BODIPY-Clioquinol Copper Chelator with Multiple Anti-AD Properties" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 26, no. 24: 11876. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262411876

APA StyleAbramchuk, D. S., Krasnovskaya, O. O., Voskresenskaya, A. S., Vaneev, A. N., Kuanaeva, R. M., Mamed-Nabizade, V. V., Kolmogorov, V. S., Kechko, O. I., Mitkevich, V. A., Makarov, A. A., Nastenko, A. A., Abakumov, M. A., Gorelkin, P. V., Salikhov, S. V., Beloglazkina, E. K., & Erofeev, A. S. (2025). Bifunctional BODIPY-Clioquinol Copper Chelator with Multiple Anti-AD Properties. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 26(24), 11876. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262411876