Pomegranate and Cherry Leaf Extracts as Stabilizers of Magnetic Hydroxyapatite Nanocarriers for Nucleic Acid Delivery

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Characterization of Plant Extract

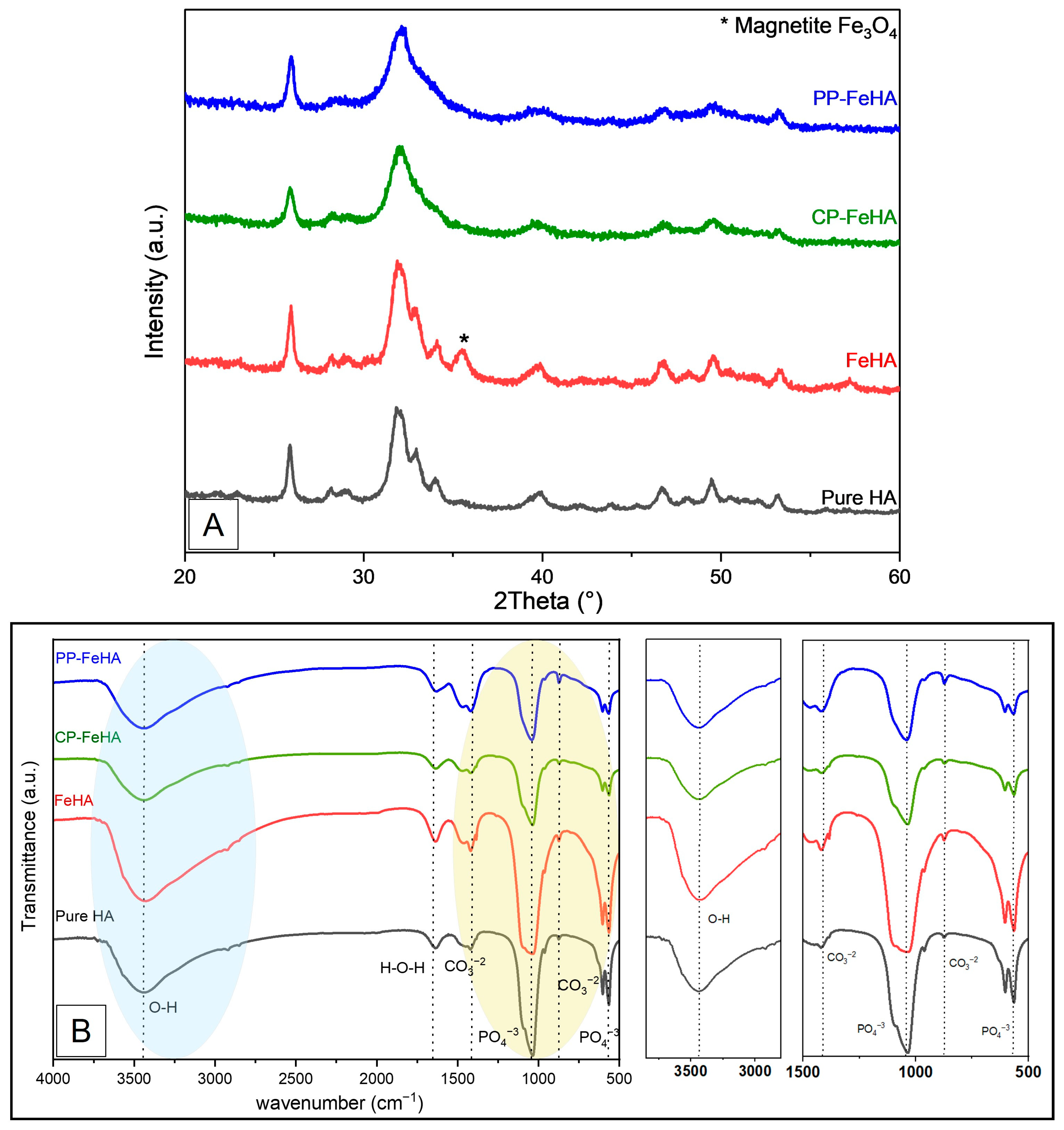

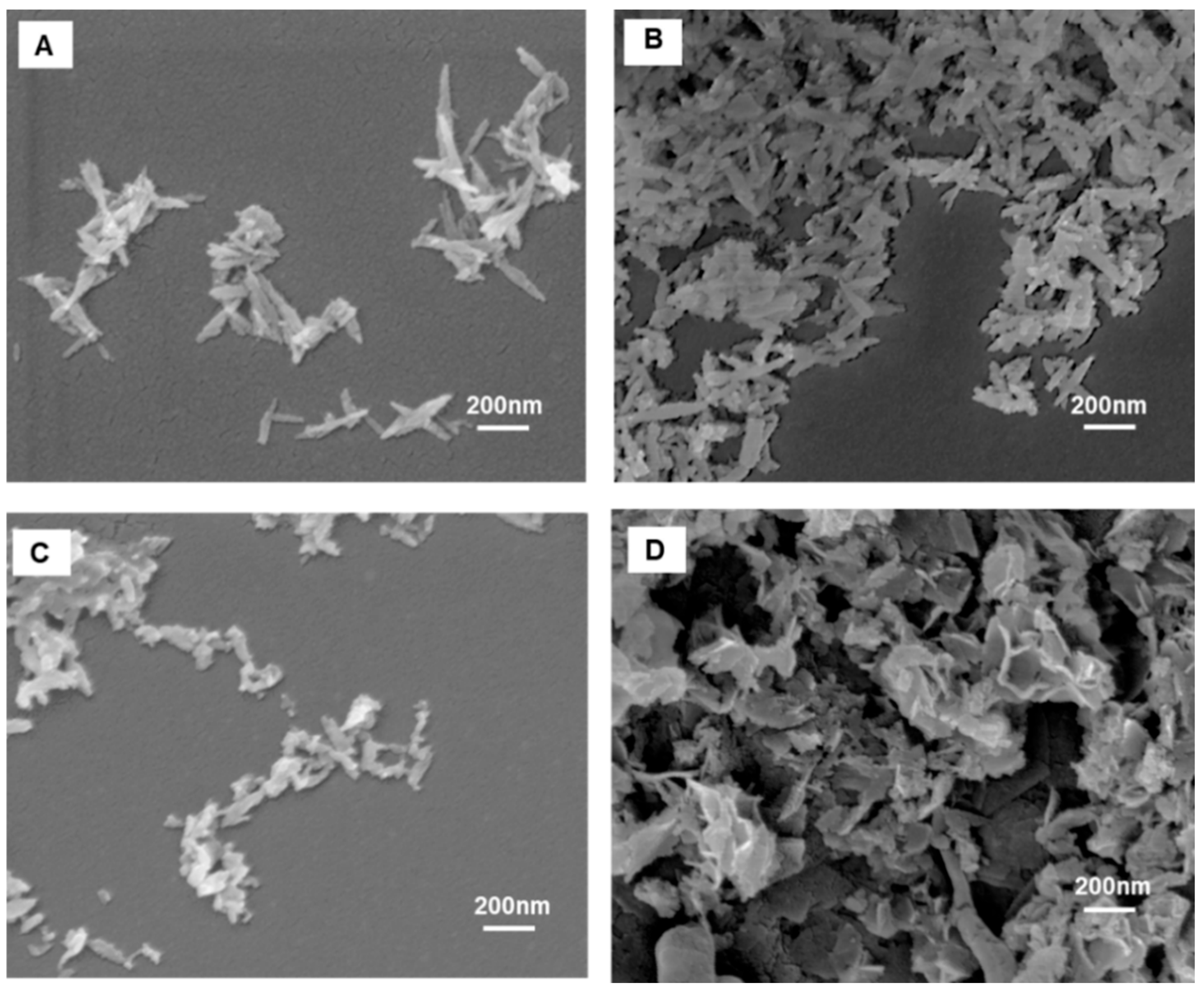

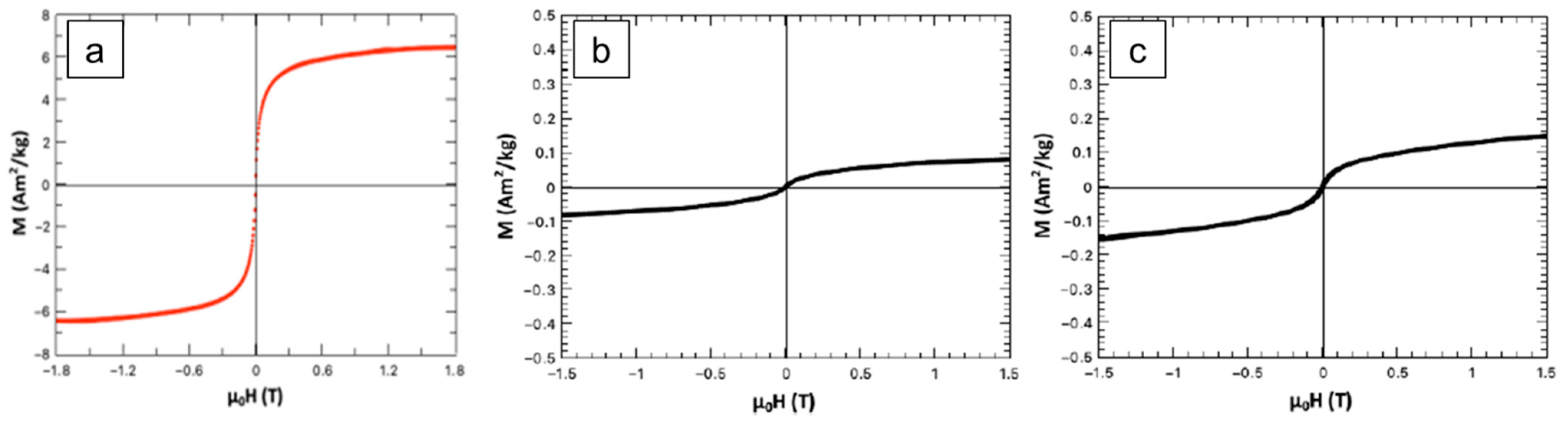

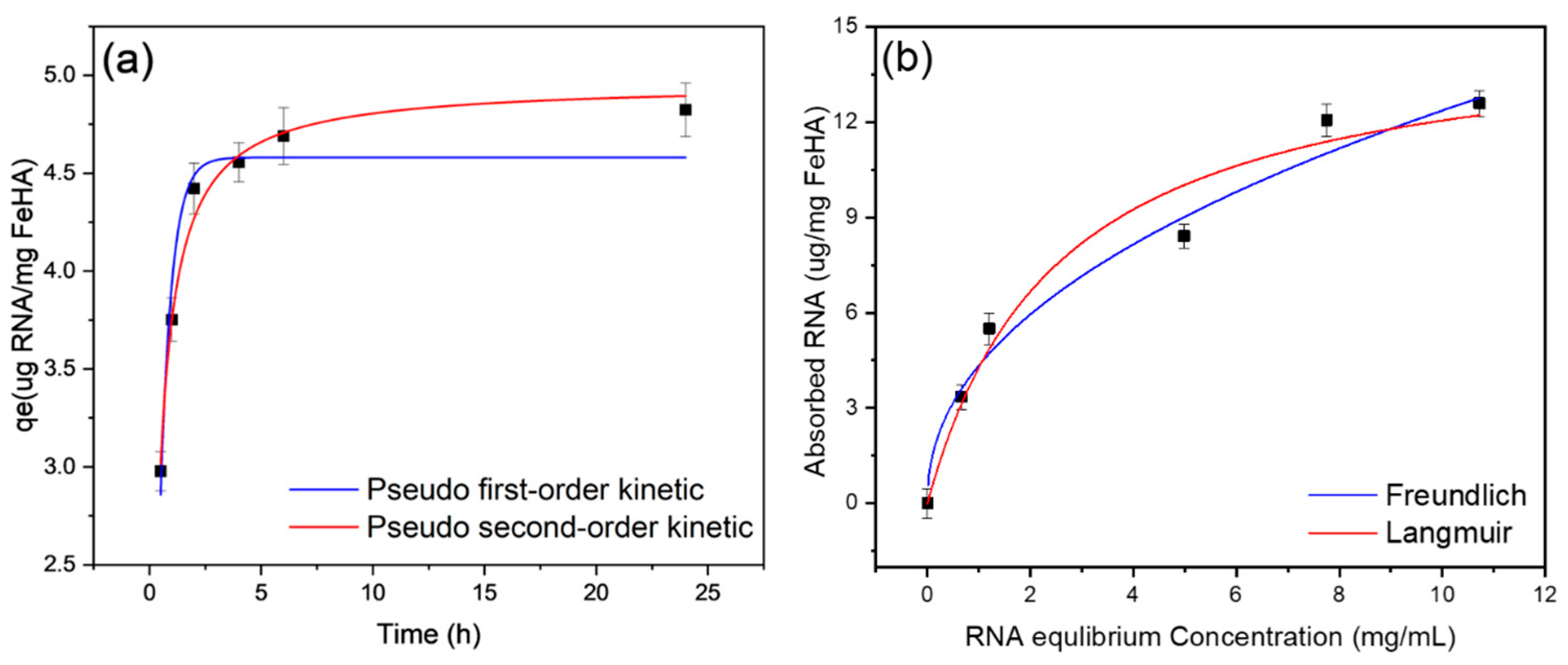

2.2. Characterization of Pure Hydroxyapatite, FeHA, CP-FeHA, and PP-FeHA

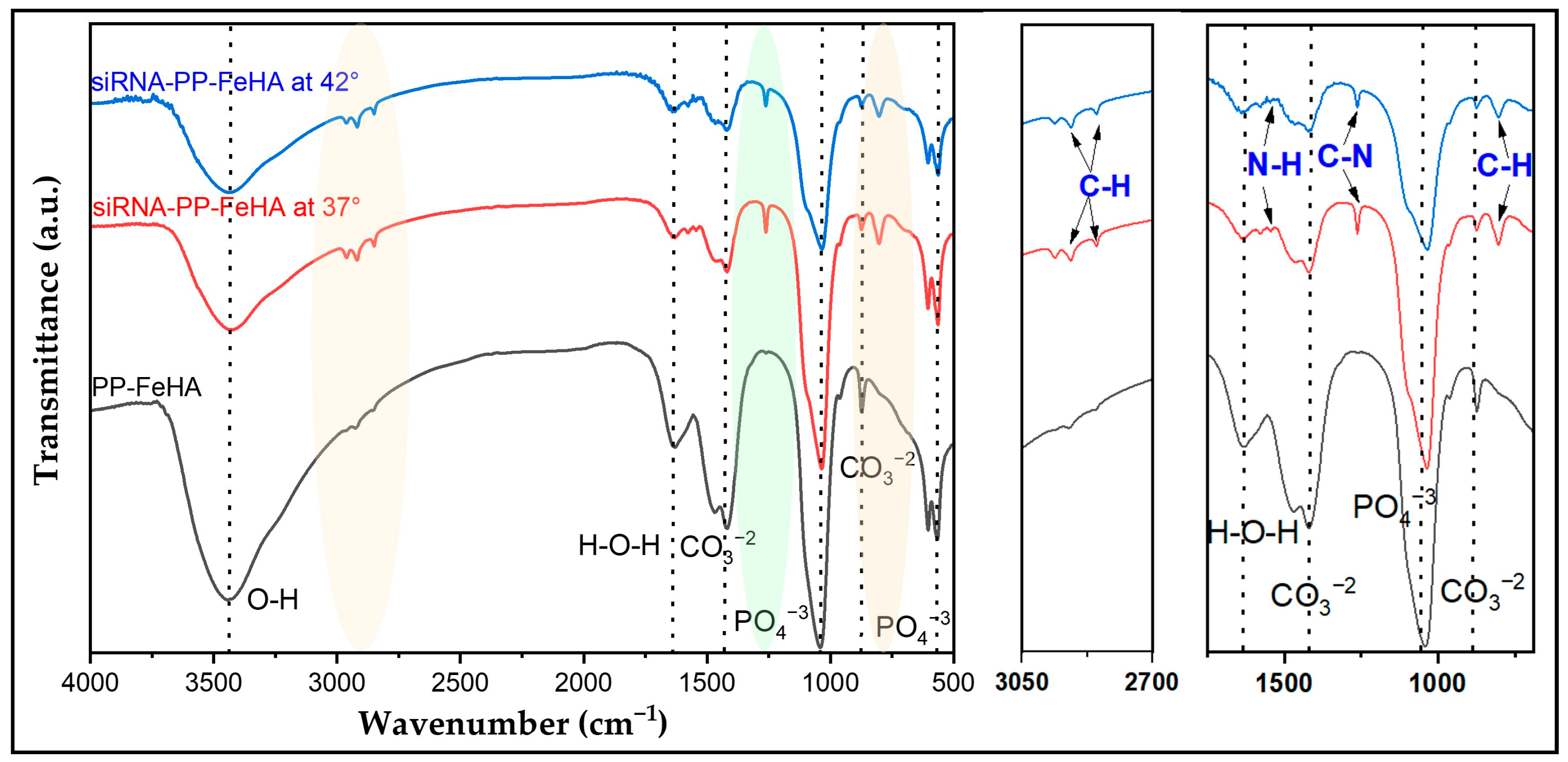

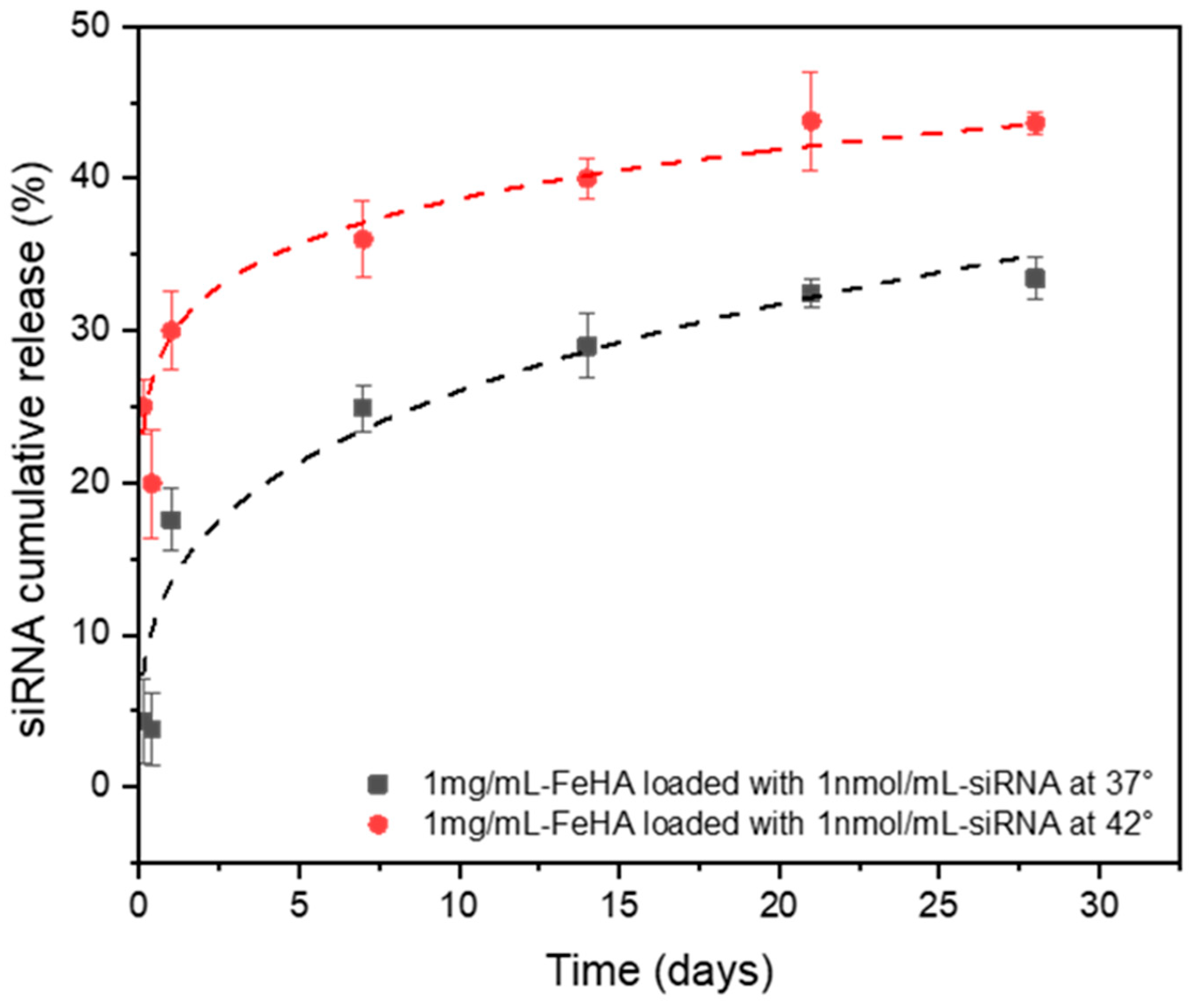

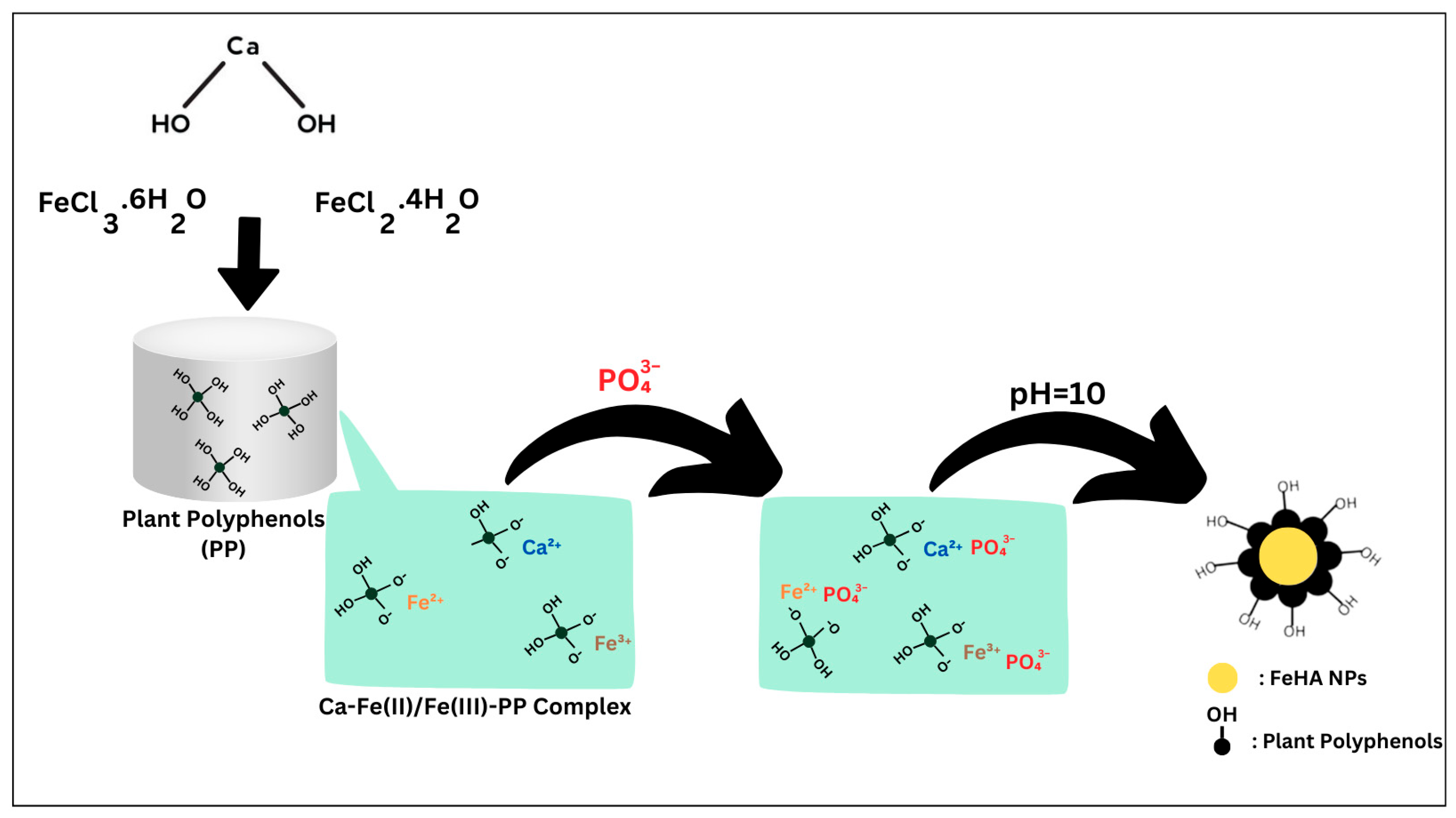

2.3. Characterization of siRNA-Loaded PP-FeHA NPs and Release Properties

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Materials

3.2. Preparation of Cherry Plant (CP) and Pomegranate Plant (PP) Leaf Extracts

3.3. Synthesis of HA, FeHA, CP-FeHA, and PP-FeHA

3.4. Determination of Antioxidant Activity Using the DPPH Assay

3.5. FeHA and PP-FeHA Characterization

3.6. siRNA Loading on PP-FeHA

3.7. Characterization of siRNA-PP-FeHA and siRNA Release

3.8. Study of siRNA Loading on FeHA-NPs

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Davidson, B.L.; McCray, P.B., Jr. Current prospects for RNA interference-based therapies. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2011, 12, 329–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitehead, K.A.; Langer, R.; Anderson, D.G. Knocking down barriers: Advances in siRNA delivery. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2009, 8, 129–138, Erratum in Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2010, 9, 412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lam, J.K.W.; Chow, M.Y.T.; Zhang, Y.; Leung, S.W.S. siRNA versus miRNA as therapeutics for gene silencing. Mol. Ther.—Nucleic Acids 2015, 4, e252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedrich, M.; Aigner, A. Therapeutic siRNA: State-of-the-art and future perspectives. BioDrugs 2022, 36, 549–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanasty, R.; Dorkin, J.R.; Vegas, A.; Anderson, D. Delivery materials for siRNA therapeutics. Nat. Mater. 2013, 12, 967–977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kesharwani, P.; Gajbhiye, V.; Jain, N.K. A review of nanocarriers for the delivery of small interfering RNA. Biomaterials 2012, 33, 7138–7150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, W.; Zhang, X.; Xu, X. Biomaterials in siRNA delivery: A comprehensive review. Adv. Healthc. Mater. 2016, 5, 2715–2731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Islam, R.A.; Al-Busaidi, H.; Zaman, R.; Abidin, S.A.Z.; Othman, I.; Chowdhury, E.H. Carbonate apatite and hydroxyapatite formulated with minimal ingredients to deliver SiRNA into breast cancer cells in vitro and in vivo. J. Funct. Biomater. 2020, 11, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pupilli, F.; Tavoni, M.; Marsan, O.; Drouet, C.; Tampieri, A.; Sprio, S. Tuning Mg doping and features of bone-like apatite nanoparticles obtained via hydrothermal synthesis. Langmuir 2024, 40, 16557–16570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inam, H.; Degli Esposti, L.; Pupilli, F.; Tavoni, M.; Casoli, F.; Sprio, S.; Tampieri, A. Iron-Doped Hydroxyapatite Nanoparticles for Magnetic Guided siRNA Delivery. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 7712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vo, T.S.; Chit, P.P.; Hwang, U.; Yu, J.; Cho, Y.; Ju, M.; Vo, T.T.B.C.; Pham, D.T.; Nguyen, V.Q.; Kim, K.J.C.; et al. Comparative Stability of Hydroxyapatite Nanoparticles: Poly (ethylene glycol) and Pectin as Stabilizers. Colloids Surf. A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2025, 728, 138674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mustafa, A.M.J.P.i.C. Colorants and Coatings, Optimizing Electrophoretic Deposition Parameters and Corrosion Resistance of Nano-Hydroxyapatite/Chitosan Coatings on Ti-6Al-7Nb Alloy Under Various Current Types. Prog. Color Color. Coat. 2025, in press. [Google Scholar]

- Duguet, E.; Vasseur, S.; Mornet, S.; Devoisselle, J.-M. Magnetic nanoparticles and their applications in medicine. Nanomedicine 2006, 1, 157–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colombo, M.; Carregal-Romero, S.; Casula, M.F.; Gutiérrez, L.; Morales, M.P.; Böhm, I.B.; Heverhagen, J.T.; Prosperi, D.; Parak, W.J. Biological applications of magnetic nanoparticles. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2012, 41, 4306–4334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laurent, S.; Saei, A.A.; Behzadi, S.; Panahifar, A.; Mahmoudi, M. Superparamagnetic iron oxide nanoparticles for delivery of therapeutic agents: Opportunities and challenges. Expert Opin. Drug Deliv. 2014, 11, 1449–1470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tampieri, A.; D’Alessandro, T.; Sandri, M.; Sprio, S.; Landi, E.; Bertinetti, L.; Panseri, S.; Pepponi, G.; Goettlicher, J.; Bañobre-López, M. Intrinsic magnetism and hyperthermia in bioactive Fe-doped hydroxyapatite. Acta Biomater. 2012, 8, 843–851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benedetti, G.; Zabini, F.; Tagliavento, L.; Meneguzzo, F.; Calderone, V.; Testai, L.J.A. An overview of the health benefits, extraction methods and improving the properties of pomegranate. Antioxidants 2023, 12, 1351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bar-Ya’AKov, I.; Tian, L.; Amir, R.; Holland, D. Primary metabolites, anthocyanins, and hydrolyzable tannins in the pomegranate fruit. Front. Plant Sci. 2019, 10, 620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- García, P.; Fredes, C.; Cea, I.; Lozano-Sánchez, J.; Leyva-Jiménez, F.J.; Robert, P.; Vergara, C.; Jimenez, P. Recovery of bioactive compounds from pomegranate (Punica granatum L.) peel using pressurized liquid extraction. Foods 2021, 10, 203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunes, A.R.; Flores-Félix, J.D.; Gonçalves, A.C.; Falcão, A.; Alves, G.; Silva, L.R. Anti-inflammatory and antimicrobial activities of Portuguese Prunus avium L. (sweet cherry) by-products extracts. Nutrients 2022, 14, 4576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frusciante, L.; Nyong’a, C.N.; Trezza, A.; Shabab, B.; Olmastroni, T.; Barletta, R.; Mastroeni, P.; Visibelli, A.; Orlandini, M.; Raucci, L.; et al. Bioactive Potential of Sweet Cherry (Prunus avium L.) Waste: Antioxidant and Anti-Inflammatory Properties for Sustainable Applications. Foods 2025, 14, 1523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benguiar, R.; Yahla, I.; Benaraba, R.; Bouamar, S.; Riazi, A. Phytochemical analysis, antibacterial and antioxidant activities of pomegranate (Punica granatum L.) peel extracts. Int. J. Biosci. 2020, 16, 35–44. [Google Scholar]

- Kazazic, M.; Mehic, E.; Djapo-Lavic, M. Phenolic content and bioactivity of two sour cherry cultivars and their products. Bull. Chem. Technol. Bosnia Herzeg. 2022, 58, 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Panche, A.N.; Diwan, A.D.; Chandra, S.R. Flavonoids: An overview. J. Nutr. Sci. 2016, 5, e47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, R.; Garg, R.; Bali, M.; Eddy, N.O. Biogenic synthesis of iron oxide nanoparticles using leaf extract of Spilanthes acmella: Antioxidation potential and adsorptive removal of heavy metal ions. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2023, 195, 1345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravikumar, K.; Kubendiran, H.; Ramesh, K.; Rani, S.; Mandal, T.K.; Pulimi, M.; Natarajan, C.; Mukherjee, A.J.E.T. Batch and column study on tetracycline removal using green synthesized NiFe nanoparticles immobilized alginate beads. Environ. Technol. Innov. 2020, 17, 100520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gopal, G.; Ravikumar, K.V.G.; Salma, M.; Chandrasekaran, N.; Mukherjee, A. Green synthesized Fe/Pd and in-situ Bentonite-Fe/Pd composite for efficient tetracycline removal. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2020, 8, 104126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ifeanyichukwu, U.L.; Fayemi, O.E.; Ateba, C.N. Green synthesis of zinc oxide nanoparticles from pomegranate (Punica granatum) extracts and characterization of their antibacterial activity. Molecules 2020, 25, 4521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gulcin, I.; Alwasel, S.H. DPPH radical scavenging assay. Processes 2023, 11, 2248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hazra, B.; Biswas, S.; Mandal, N. Antioxidant and free radical scavenging activity of Spondias pinnata. BMC Complement. Altern. Med. 2008, 8, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wojdylo, A.; Oszmianski, J.; Czemerys, R. Antioxidant activity and phenolic compounds in 32 selected herbs. Food Chem. 2007, 105, 940–949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kähkönen, M.P.; Hopia, A.I.; Vuorela, H.J.; Rauha, J.-P.; Pihlaja, K.; Kujala, T.S.; Heinonen, M. Antioxidant activity of plant extracts containing phenolic compounds. J. Agric. Food Chem. 1999, 47, 3954–3962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, B.; Singh, J.P.; Kaur, A.; Singh, N. Phenolic compounds as beneficial phytochemicals in pomegranate (Punica granatum L.) peel: A review. Food Chem. 2018, 261, 75–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belounis, Y.; Moualek, I.; Sebbane, H.; Ait Issad, H.; Saci, S.; Saoudi, B.; Nabti, E.-H.; Trabelsi, L.; Houali, K.; Cruz, C. Potential Natural Antioxidant and Anti-Inflammatory Properties of Carthamus caeruleus L. Root Aqueous Extract: An In Vitro Evaluation. Processes 2025, 13, 878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sa, Y.; Guo, Y.; Feng, X.; Wang, M.; Li, P.; Gao, Y.; Yang, X.; Jiang, T. Are different crystallinity-index-calculating methods of hydroxyapatite efficient and consistent? New J. Chem. 2017, 41, 5723–5731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, X.; Yi, Z.; Li, X. Novel Synthesis Approach for Natural Tea Polyphenol-Integrated Hydroxyapatite. Pharmaceuticals 2024, 17, 251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iannotti, V.; Adamiano, A.; Ausanio, G.; Lanotte, L.; Aquilanti, G.; Coey, J.M.D.; Lantieri, M.; Spina, G.; Fittipaldi, M.; Margaris, G.; et al. Fe-Doping-Induced Magnetism in Nano-Hydroxyapatites. Inorg. Chem. 2017, 56, 4446–4458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Călin, C.; Sîrbu, E.-E.; Tănase, M.; Győrgy, R.; Popovici, D.R.; Banu, I. A Thermogravimetric Analysis of Biomass Conversion to Biochar: Experimental and Kinetic Modeling. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 9856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasser, S.M.; Abbas, M.; Trari, M. Understanding the rate-limiting step adsorption kinetics onto biomaterials for mechanism adsorption control. Prog. React. Kinet. Mech. 2024, 49, 14686783241226858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, J.; Wang, L. Comparison between linear and non-linear forms of pseudo-first-order and pseudo-second-order adsorption kinetic models for the removal of methylene blue by activated carbon. Front. Environ. Sci. Eng. China 2009, 3, 320–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Liu, Y.-J. Biosorption isotherms, kinetics and thermodynamics. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2008, 61, 229–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aljabbari, A.; Lokras, A.G.; Kirkensgaard, J.J.K.; Rades, T.; Franzyk, H.; Thakur, A.; Zhang, Y.; Foged, C. Elucidating the nanostructure of small interfering RNA-loaded lipidoid-polymer hybrid nanoparticles. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2023, 633, 907–922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Song, W.; Cui, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Mei, S.; Wang, Q. Calcium-siRNA nanocomplexes optimized by bovine serum albumin coating can achieve convenient and efficient siRNA delivery for periodontitis therapy. Int. J. Nanomed. 2020, 15, 9241–9253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, X.; Niu, X.; Ma, K.; Huang, P.; Grothe, J.; Kaskel, S.; Zhu, Y. Graphene quantum dots-capped magnetic mesoporous silica nanoparticles as a multifunctional platform for controlled drug delivery, magnetic hyperthermia, and photothermal therapy. Small 2017, 13, 1602225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paarakh, M.P.; Jose, P.A.; Setty, C.; Peterchristoper, G. Release kinetics–concepts and applications. Int. J. Pharm. Res. Technol. (IJPRT) 2018, 8, 12–20. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, S.J.; Ko, W.-K.; Han, G.H.; Lee, D.; Cho, M.J.; Sheen, S.H.; Sohn, S. Axon guidance gene-targeted siRNA delivery system improves neural stem cell transplantation therapy after spinal cord injury. Biomater. Res. 2023, 27, 101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeley, M.; Long, A. Advances in siRNA delivery to T-cells: Potential clinical applications for inflammatory disease, cancer and infection. Biochem. J. 2013, 455, 133–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamtekar, S.; Keer, V.; Patil, V. Estimation of phenolic content, flavonoid content, antioxidant and alpha amylase inhibitory activity of marketed polyherbal formulation. J. Appl. Pharm. Sci. 2014, 4, 061–065. [Google Scholar]

- Sen, S.; De, B.; Devanna, N.; Chakraborty, R. Total phenolic, total flavonoid content, and antioxidant capacity of the leaves of Meyna spinosa Roxb., an Indian medicinal plant. Chin. J. Nat. Med. 2013, 11, 149–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Antioxidants | DPPH IC50 (µg/mL) | Adjusted R2 |

|---|---|---|

| Gallic acid | 54.23 ± 4 | 0.991 |

| Pomegranate leaf extract | 145.84 ± 10 | 0.988 |

| Cherry leaf extract | 349.3 ± 30 | 0.993 |

| Sample | Ca/P (mol) a | (Ca + Fe)/P (mol) a | Fe (wt.%) a * | Fe2+ (wt.%) b * | Fe3+/Fe2+ | Fe2+/Fe3+ | Fe2+ % (Fe2+/Fe tot) | Fe3+ % (Fe3+/Fe tot) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HA | 1.69 ± 0.01 | 1.69 ± 0.01 | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| FeHA | 1.47 ± 0.01 | 1.78 ± 0.02 | 13 ± 1 | 0.74 ± 0.01 | 16.57 | 0.06 | 5.69 | 94.29 |

| CP-FeHA | 1.64 ± 0.01 | 1.81 ± 0.01 | 5 ± 0.1 | 0.37 ± 0.01 | 12.51 | 0.08 | 7.40 | 92.60 |

| PP-FeHA | 1.63 ± 0.01 | 1.90 ± 0.03 | 7.8 ± 0.4 | 0.96 ± 0.02 | 7.12 | 0.14 | 12.31 | 87.69 |

| Sample | SSABET (m2/g) | Z-Average (nm) b | PdI b | ζ-Potential (mV) b | Water Loss % (20–250 °C) a | Organic Decomposition % (250–500 °C) a | Carbonate Loss % (600–1100 °C) a | Total Loss % (20–1100 °C) a |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HA | 97.18 | 220 ± 1 | 0.27 ± 0.01 | −18 ± 3 | 5.14 | N/A | 1.98 | 7.11 |

| FeHA | 102.65 | 195 ± 1 | 0.26 ± 0.05 | −24 ± 3 | 4.96 | N/A | 2.58 | 7.54 |

| CP-FeHA | 182 | 80 ± 1 | 0.29 ± 0.02 | −32 ± 2 | 8.21 | 4.9 | 3.20 | 16.27 |

| PP-FeHA | 235.75 | 88 ± 1 | 0.18 ± 0.01 | −35 ± 4 | 7.75 | 6.4 | 7.61 | 21.75 |

| Model | Adjusted R2 | Qads,e (mg RNA/g FeHA) | k1/k2 (min−1) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pseudo first-order | 0.956 | 4.58 ± 0.09 | 1.96 ± 0.15 |

| Pseudo second-order | 0.988 | 4.96 ± 0.06 | 0.62 ± 0.05 |

| Model | Adjusted R2 | Qm (µg RNA/mg FeHA) | KL/KF (µM−1) | n |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Langmuir | 0.963 | 15.09 ± 1.61 | 0.40 ± 0.13 | - |

| Freundlich | 0.959 | - | 4.51 ± 0.53 | 0.44 ± 0.058 |

| Sample | siRNA Payload (nmol/mg) | siRNA Loading Efficiency (%) | Z-Average (nm) | PdI | ζ-Potential (mV) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| siRNA-PP-FeHA at 37°C | 0.57 ± 0.04 | 75.00 ± 0.32 | 179.0 ± 1.2 | 0.22 ± 0.01 | −30.3 ± 4.1 |

| siRNA-PP-FeHA at 42°C | 0.63 ± 0.03 | 88.00 ± 0.20 | 180.0 ± 1.5 | 0.26 ± 0.02 | −32.4 ± 3.3 |

| Sample | K (Release Constant) | n (Release Exponent) | Release Mechanism | R-Square (COD) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| siRNA-PP-FeHA at 37° | 0.135 ± 0.020 | 0.286 ± 0.050 | Fickian Diffusion | 0.93 |

| siRNA-PP-FeHA at 42° | 0.296 ± 0.011 | 0.116 ± 0.012 | Fickian Diffusion | 0.96 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Inam, H.; Sprio, S.; Pupilli, F.; Tavoni, M.; Tampieri, A. Pomegranate and Cherry Leaf Extracts as Stabilizers of Magnetic Hydroxyapatite Nanocarriers for Nucleic Acid Delivery. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 11562. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311562

Inam H, Sprio S, Pupilli F, Tavoni M, Tampieri A. Pomegranate and Cherry Leaf Extracts as Stabilizers of Magnetic Hydroxyapatite Nanocarriers for Nucleic Acid Delivery. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2025; 26(23):11562. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311562

Chicago/Turabian StyleInam, Hina, Simone Sprio, Federico Pupilli, Marta Tavoni, and Anna Tampieri. 2025. "Pomegranate and Cherry Leaf Extracts as Stabilizers of Magnetic Hydroxyapatite Nanocarriers for Nucleic Acid Delivery" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 26, no. 23: 11562. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311562

APA StyleInam, H., Sprio, S., Pupilli, F., Tavoni, M., & Tampieri, A. (2025). Pomegranate and Cherry Leaf Extracts as Stabilizers of Magnetic Hydroxyapatite Nanocarriers for Nucleic Acid Delivery. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 26(23), 11562. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311562