Role of Apyrase in Mobilization of Phosphate from Extracellular Nucleotides and in Regulating Phosphate Uptake in Arabidopsis

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

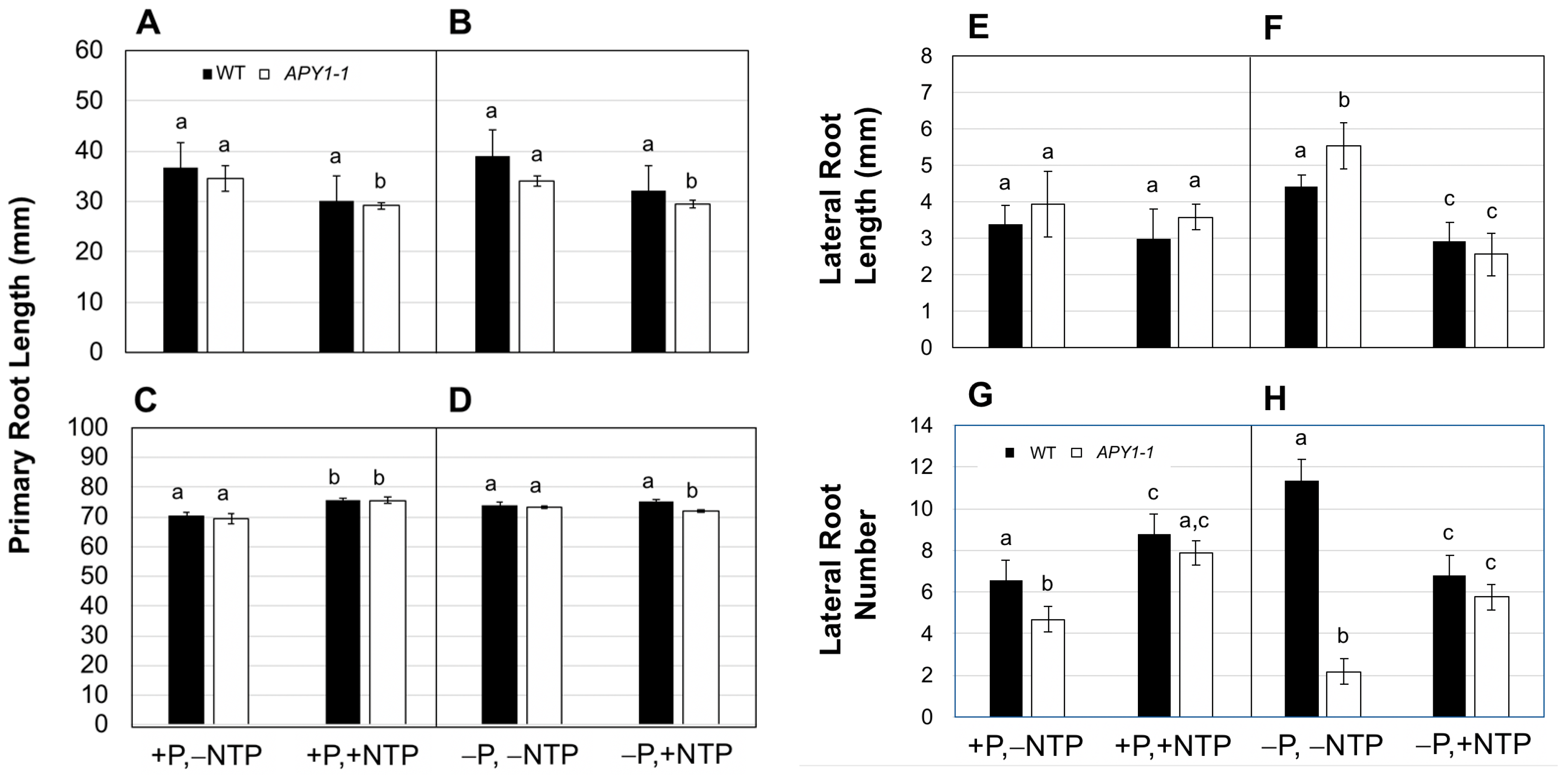

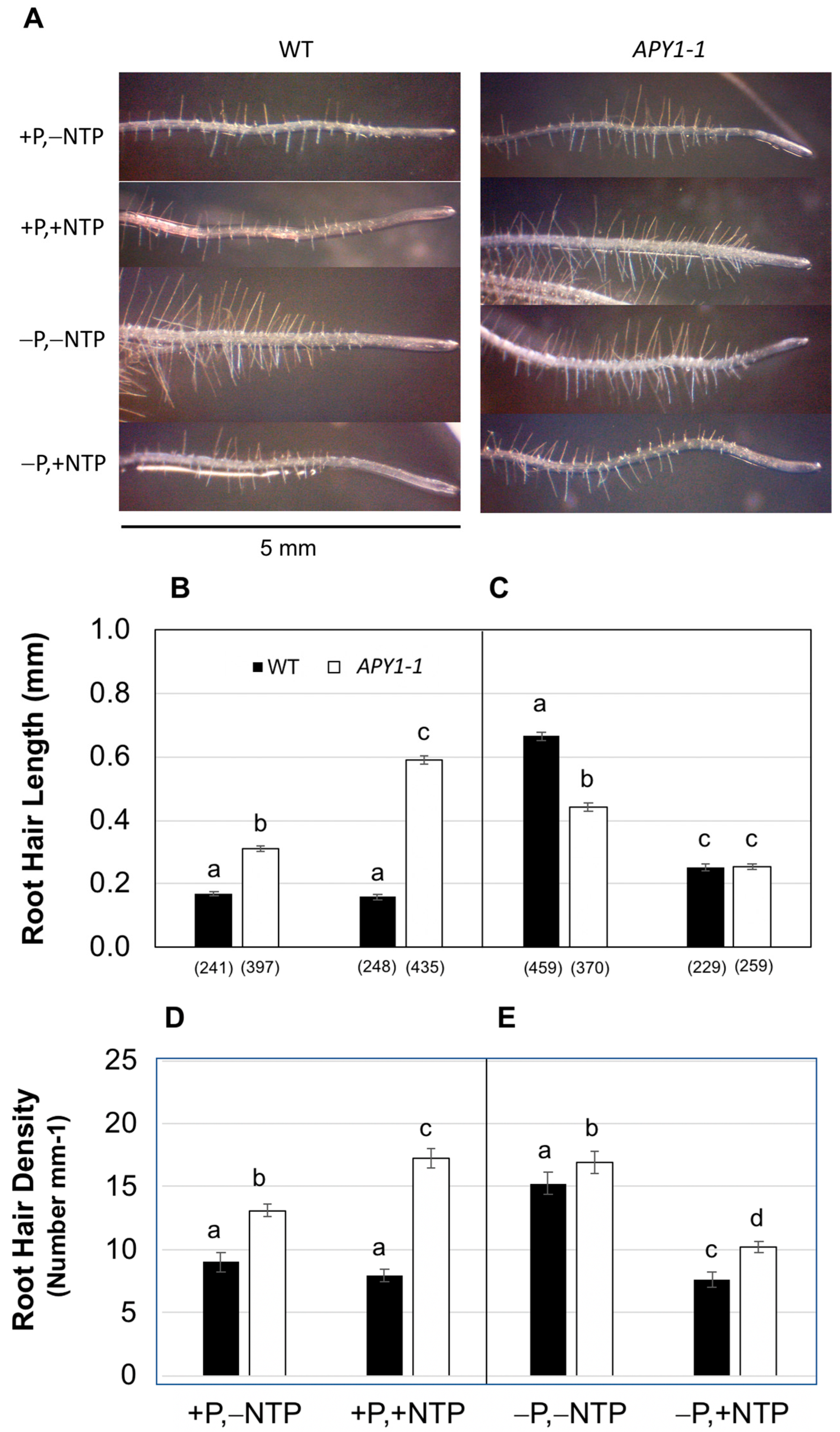

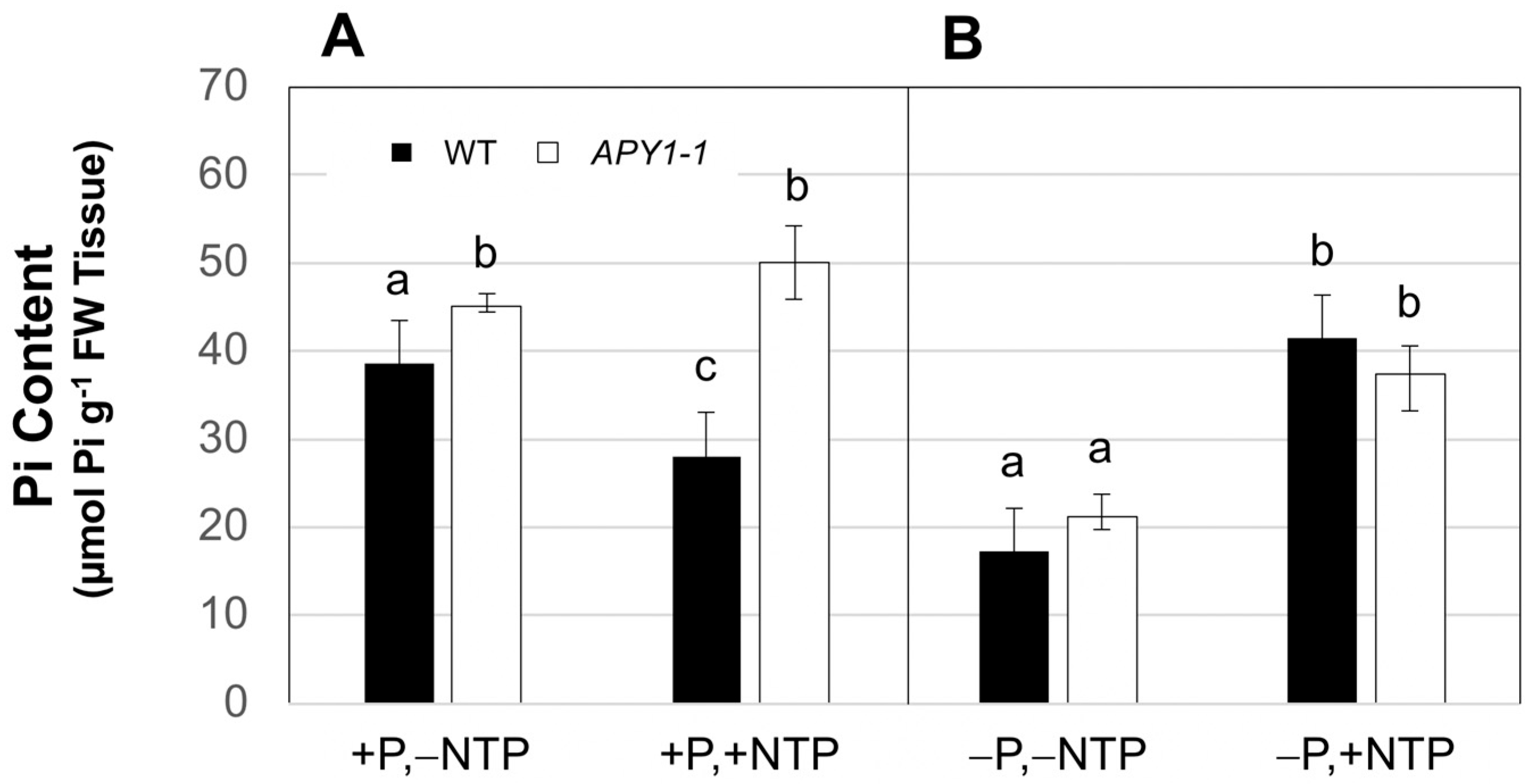

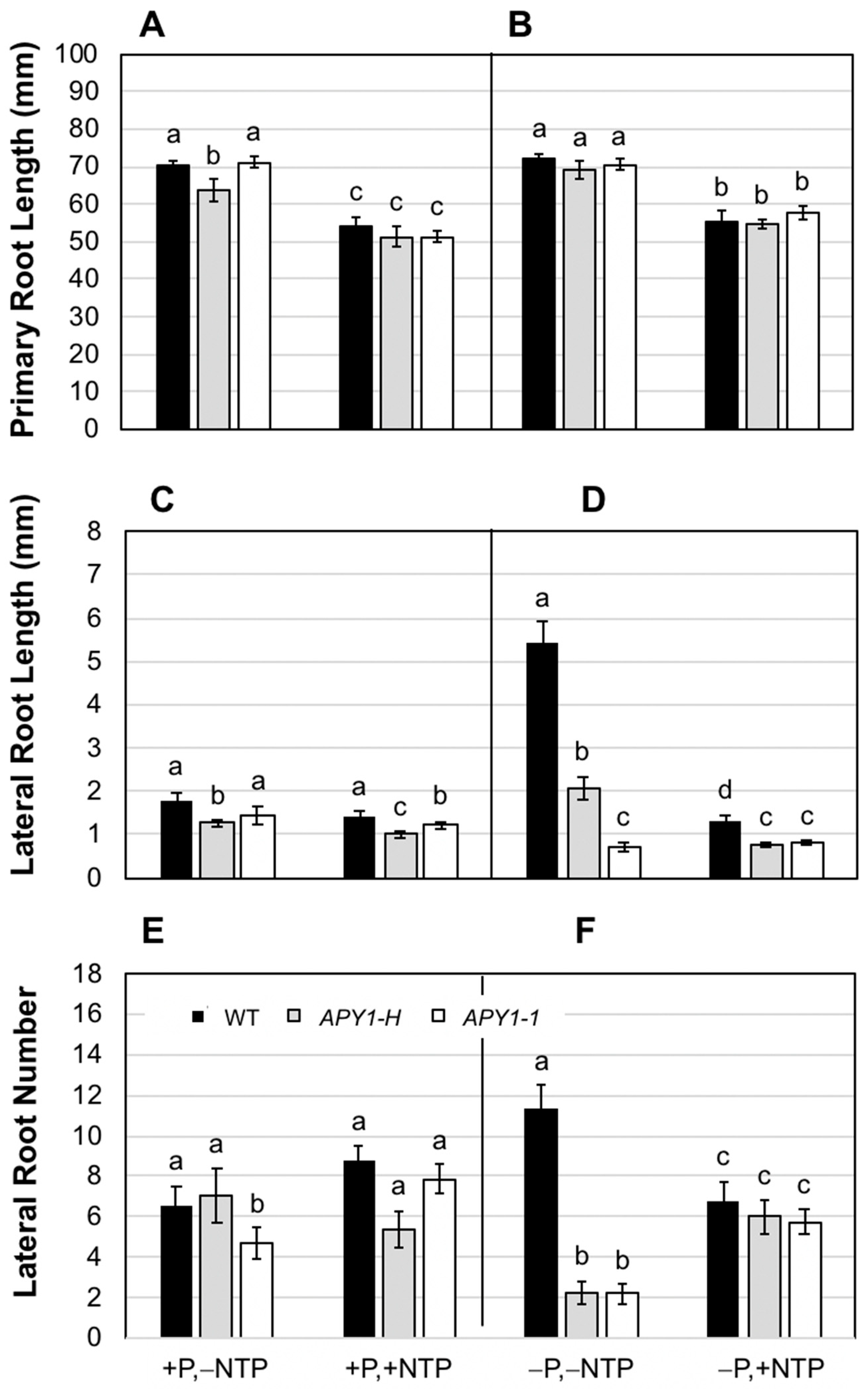

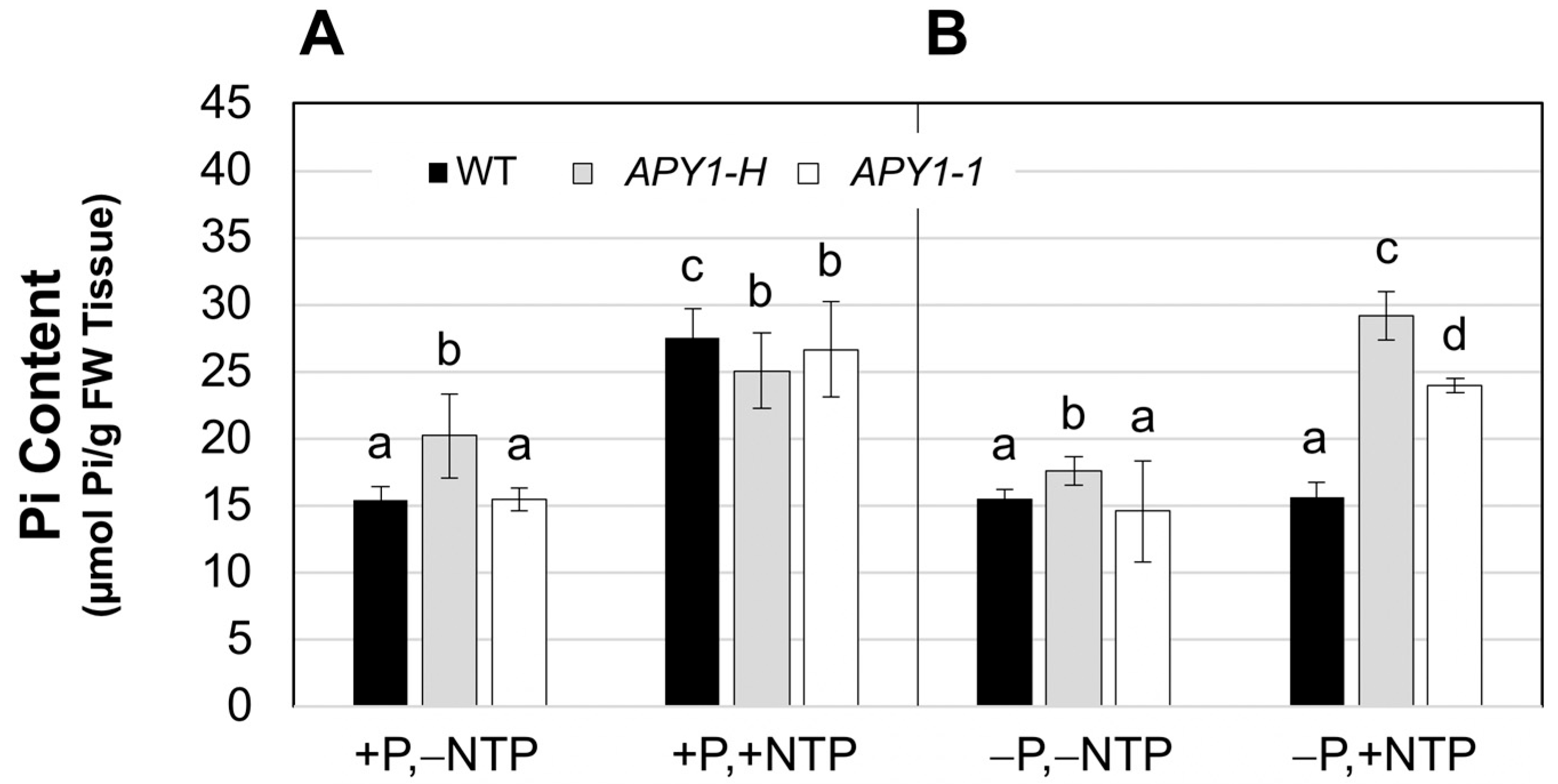

2.1. Effects of P Limitation and Continuous NTP Supplementation on Seedling Root System Architecture and Pi Contents

2.2. Effects of P Limitation and Short-Term NTP or Pi Supplementation on Seedling Root System Architecture and Pi Contents

2.3. Genome-Wide Expression Profiling to Investigate Responses of WT and APY1 Seedlings to P Limitation and NTP Supplementation

2.3.1. Gene Expression Changes in Response to P Limitation

2.3.2. Transcriptome Responses to NTP Under P Limitation

2.3.3. Transcriptome Responses to NTP Under Conditions of P Sufficiency

3. Discussion

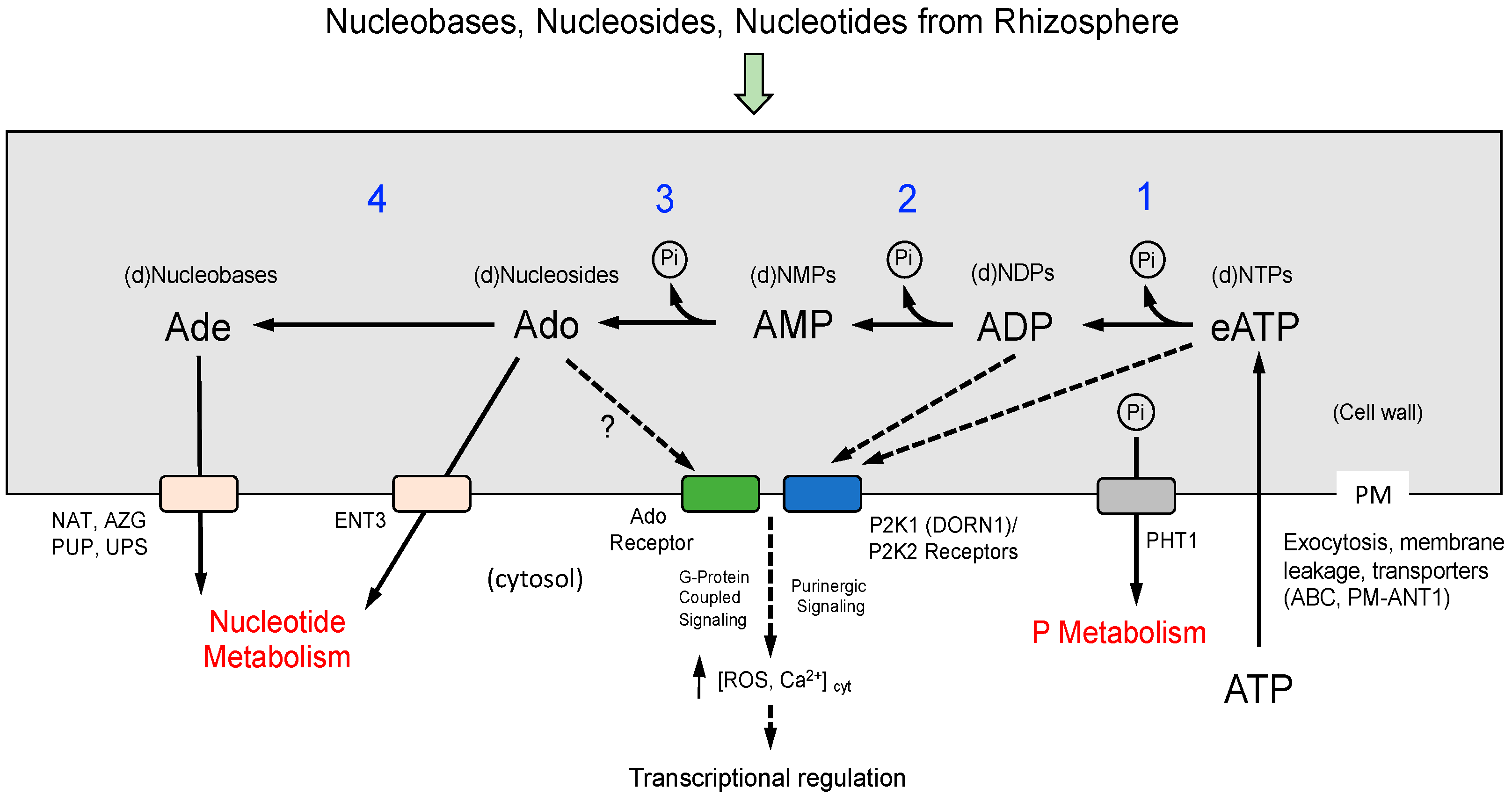

3.1. Metabolism of eNTP as a Source of Pi in Arabidopsis Seedlings

3.2. Extracellular NTP Signaling in APY1 Seedlings Growing Under Pi-Sufficiency

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Growth of Arabidopsis Seedlings

4.2. Root System Architecture (RSA) Analyses

4.3. Seedling Phosphate Content Assay

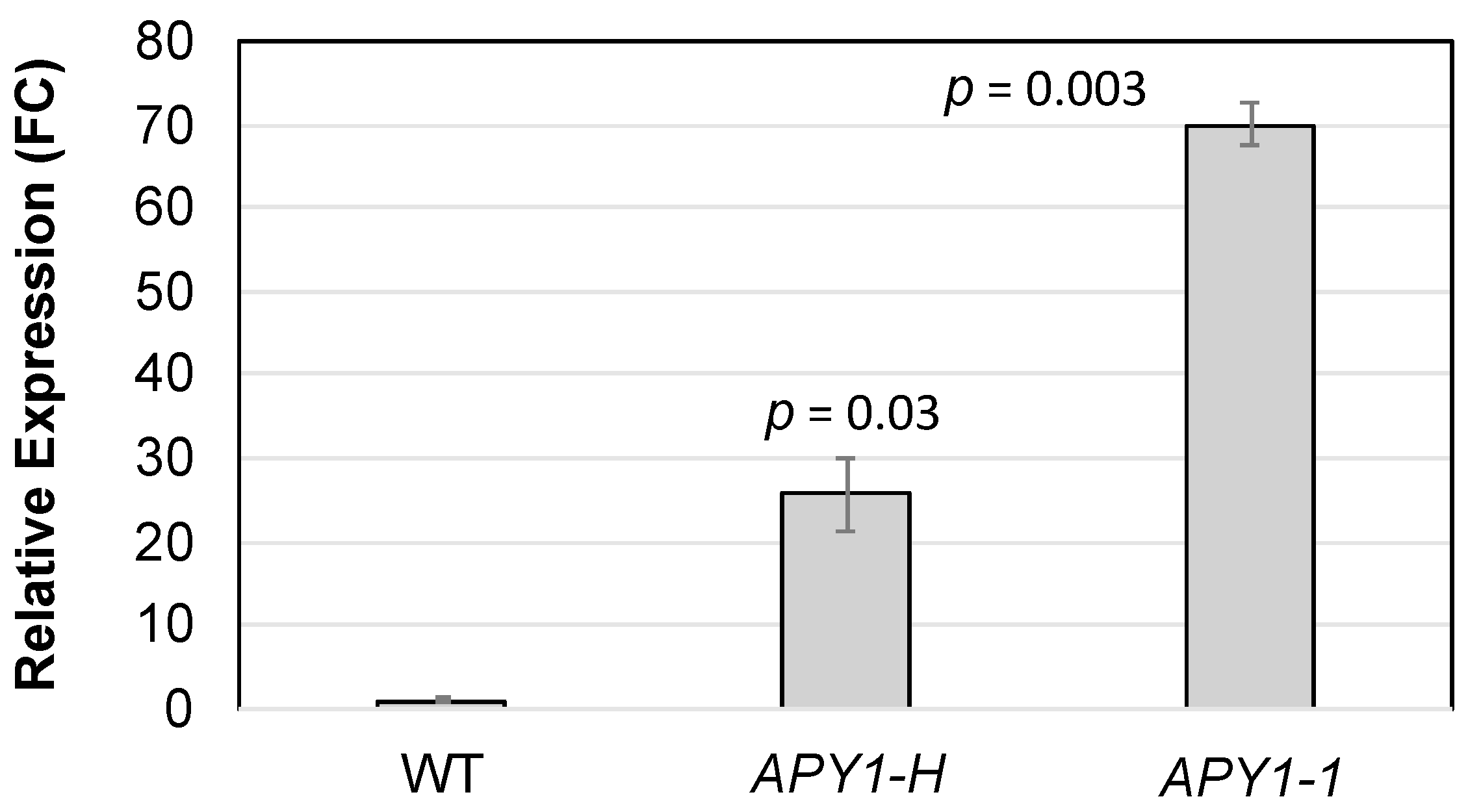

4.4. Construction and Characterization of the APY1 Overexpression Lines

4.5. RNA Isolation, cDNA Synthesis, and qRT-PCR Analyses

4.6. Genome-Wide Expression Analyses

4.7. Statistical Analyses

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| eATP | extracellular ATP |

| AMP | adenosine-5′-monophosphate |

| RSA | root system architecture |

| PSR | phosphate starvation response |

| LR | lateral roots |

| RH | root hairs |

| DEG | differentially expressed gene(s) |

| Pi | inorganic phosphate |

| ECM | extracellular matrix |

References

- Schachtman, D.P.; Reid, R.J.; Ayling, S.M. Phosphorus Uptake by Plants: From Soil to Cell. Plant Physiol. 1998, 116, 447–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Młodzińska, E.; Zboińska, M. Phosphate Uptake and Allocation—A Closer Look at Arabidopsis thaliana L. and Oryza sativa L. Front. Plant Sci. 2016, 7, 1198. [Google Scholar]

- Raghothama, K.G. Phosphate Acquisition. Annu. Rev. Plant Physiol. Plant Mol. Biol. 1999, 50, 665–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, L.M.; Jia, X.X.; Zhang, G.L.; Shao, M.A. Soil Organic Phosphorus Transformation during Ecosystem Development: A Review. Plant Soil 2017, 417, 17–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plassard, C.; Dell, B. Phosphorus Nutrition of Mycorrhizal Trees. Tree Physiol. 2010, 30, 1129–1139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tran, H.; Qian, W.; Hurley, B.; She, Y.-M.; Wang, D.; Plaxton, W.C. Biochemical and Molecular Characterization of AtPAP12 and AtPAP26: The Predominant Purple Acid Phosphatase Isozymes Secreted by Phosphate-Starved Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant. Cell Environ. 2010, 33, 1789–1803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bariola, P.A.; Howard, C.J.; Taylor, C.B.; Verburg, M.T.; Jaglan, V.D.; Green, P.J. The Arabidopsis Ribonuclease Gene RNS1 Is Tightly Controlled in Response to Phosphate Limitation. Plant J. 1994, 6, 673–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, D.L.; Delatorre, C.A.; Bakker, A.; Abel, S. Conditional Identification of Phosphate-Starvation-Response Mutants in Arabidopsis thaliana. Planta 2000, 211, 13–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, W.D.; Park, J.; Tran, H.T.; Del Vecchio, H.A.; Ying, S.; Zins, J.L.; Patel, K.; McKnight, T.D.; Plaxton, W.C. The Secreted Purple Acid Phosphatase Isozymes AtPAP12 and AtPAP26 Play a Pivotal Role in Extracellular Phosphate-Scavenging by Arabidopsis thaliana. J. Exp. Bot. 2012, 63, 6531–6542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lareen, A.; Burton, F.; Schäfer, P. Plant Root-Microbe Communication in Shaping Root Microbiomes. Plant Mol. Biol. 2016, 90, 575–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, J.; Zhao, J.; Wen, T.; Zhao, M.; Li, R.; Goossens, P.; Huang, Q.; Bai, Y.; Vivanco, J.M.; Kowalchuk, G.A.; et al. Root Exudates Drive the Soil-Borne Legacy of Aboveground Pathogen Infection. Microbiome 2018, 6, 156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dark, A.; Demidchik, V.; Richards, S.L.; Shabala, S.; Davies, J.M. Release of Extracellular Purines from Plant Roots and Effect on Ion Fluxes. Plant Signal. Behav. 2011, 6, 1855–1857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pietrowska-Borek, M.; Dobrogojski, J.; Sobieszczuk-Nowicka, E.; Borek, S. New Insight into Plant Signaling: Extracellular ATP and Uncommon Nucleotides. Cells 2020, 9, 345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dyckmans, J.; Chander, K.; Joergensen, R.G.; Priess, J.; Raubuch, M.; Sehy, U. Adenylates as an Estimate of Microbial Biomass C in Different Soil Groups. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2003, 35, 1485–1491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, C.; Sun, Y.; Naus, K.; Lloyd, A.; Roux, S. Apyrase Functions in Plant Phosphate Nutrition and Mobilizes Phosphate from Extracellular ATP. Plant Physiol. 1999, 119, 543–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rieder, B.; Neuhaus, H.E. Identification of an Arabidopsis Plasma Membrane–Located ATP Transporter Important for Anther Development. Plant Cell 2011, 23, 1932–1944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Major, P.; Embley, T.M.; Williams, T.A. Phylogenetic Diversity of NTT Nucleotide Transport Proteins in Free-Living and Parasitic Bacteria and Eukaryotes. Genome Biol. Evol. 2017, 9, 480–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, W.; Lin, Y.; Liu, P.; Chen, Q.; Tian, J.; Liang, C. Association of Extracellular DNTP Utilization with a GmPAP1-like Protein Identified in Cell Wall Proteomic Analysis of Soybean Roots. J. Exp. Bot. 2018, 69, 603–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, S.; Chen, M.; Liang, C.; Xue, Y.; Lin, S.; Tian, J. Characterization of Purple Acid Phosphatase Family and Functional Analysis of GmPAP7a/7b Involved in Extracellular ATP Utilization in Soybean. Front. Plant Sci. 2020, 11, 661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, C.; Tian, J.; Lam, H.M.; Lim, B.L.; Yan, X.; Liao, H. Biochemical and Molecular Characterization of PvPAP3, a Novel Purple Acid Phosphatase Isolated from Common Bean Enhancing Extracellular ATP Utilization. Plant Physiol. 2010, 152, 854–865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kavka, M.; Majcherczyk, A.; Kües, U.; Polle, A. Phylogeny, Tissue-Specific Expression, and Activities of Root-Secreted Purple Acid Phosphatases for P Uptake from ATP in P Starved Poplar. Plant Sci. 2021, 307, 110906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riewe, D.; Grosman, L.; Fernie, A.R.; Zauber, H.; Wucke, C.; Geigenberger, P. A Cell Wall-Bound Adenosine Nucleosidase Is Involved in the Salvage of Extracellular ATP in Solanum tuberosum. Plant Cell Physiol. 2008, 49, 1572–1579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cornelius, S.; Traub, M.; Bernard, C.; Salzig, C.; Lang, P.; Möhlmann, T. Nucleoside Transport across the Plasma Membrane Mediated by Equilibrative Nucleoside Transporter 3 Influences Metabolism of Arabidopsis Seedlings. Plant Biol. 2012, 14, 696–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, G.; Vanegas, D.; Cannon, A.; Jankovik, M.; Huang, R.; Brown, K.A.; McLamore, E.; J. Roux, S. Levels of Extracellular ATP in Growth Zones of Arabidopsis Primary Roots Are Changed by Altered Expression of Apyrase Enzymes. Plant Signal. Behav. 2025, 20, 2555965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Veerappa, R.; Slocum, R.D.; Siegenthaler, A.; Wang, J.; Clark, G.; Roux, S.J. Ectopic Expression of a Pea Apyrase Enhances Root System Architecture and Drought Survival in Arabidopsis and Soybean. Plant. Cell Environ. 2019, 42, 337–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Péret, B.; Desnos, T.; Jost, R.; Kanno, S.; Berkowitz, O.; Nussaume, L. Root Architecture Responses: In Search of Phosphate. Plant Physiol. 2014, 166, 1713–1723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abel, S. Phosphate Scouting by Root Tips. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 2017, 39, 168–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, G.; Wu, M.; Wat, N.; Onyirimba, J.; Pham, T.; Herz, N.; Ogoti, J.; Gomez, D.; Canales, A.A.; Aranda, G.; et al. Both the Stimulation and Inhibition of Root Hair Growth Induced by Extracellular Nucleotides in Arabidopsis Are Mediated by Nitric Oxide and Reactive Oxygen Species. Plant Mol. Biol. 2010, 74, 423–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, W.; Brady, S.R.; Sun, Y.; Muday, G.K.; Roux, S.J. Extracellular ATP Inhibits Root Gravitropism at Concentrations That Inhibit Polar Auxin Transport. Plant Physiol. 2003, 131, 147–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, X.; Wu, J.; Clark, G.; Lundy, S.; Lim, M.; Arnold, D.; Chan, J.; Tang, W.; Muday, G.K.; Gardner, G.; et al. Role for Apyrases in Polar Auxin Transport in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 2012, 160, 1985–1995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, X.; Wang, B.; Farris, B.; Clark, G.; Roux, S.J. Modulation of Root Skewing in Arabidopsis by Apyrases and Extracellular ATP. Plant Cell Physiol. 2015, 56, 2197–2206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williamson, L.C.; Ribrioux, S.P.C.P.; Fitter, A.H.; Ottoline Leyser, H.M. Phosphate Availability Regulates Root System Architecture in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 2001, 126, 875–882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, Z.; Bielenberg, D.G.; Brown, K.M.; Lynch, J.P. Regulation of Root Hair Density by Phosphorus Availability in Arabidopsis Thaliana. Plant. Cell Environ. 2001, 24, 459–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Misson, J.; Raghothama, K.G.; Jain, A.; Jouhet, J.; Block, M.A.; Bligny, R.; Ortet, P.; Creff, A.; Somerville, S.; Rolland, N.; et al. A Genome-Wide Transcriptional Analysis Using Arabidopsis thaliana Affymetrix Gene Chips Determined Plant Responses to Phosphate Deprivation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2005, 102, 11934–11939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, H.; Shin, H.S.; Dewbre, G.R.; Harrison, M.J. Phosphate Transport in Arabidopsis: Pht1;1 and Pht1;4 Play a Major Role in Phosphate Acquisition from Both Low- and High-Phosphate Environments. Plant J. 2004, 39, 629–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, D.P.; Kim, D.; Xuan, Y.H. Extracellular ATP: An Emerging Multifaceted Regulator of Plant Fitness. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2025, 23, 1771–1782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, J.; Zhou, Y.; Xie, Y.; Li, T.; Su, X.; He, J.; Jiang, Y.; Zhu, H.; Qu, H. ATP Homeostasis and Signaling in Plants. Plant Commun. 2024, 5, 100834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, M.; Chen, A.; Sun, S.; Xu, G. Complex Regulation of Plant Phosphate Transporters and the Gap between Molecular Mechanisms and Practical Application: What Is Missing? Mol. Plant 2016, 9, 396–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, L.; Song, L.; Zhang, Y.; Zheng, Z.; Liu, D. Arabidopsis PHL2 and PHR1 Act Redundantly as the Key Components of the Central Regulatory System Controlling Transcriptional Responses to Phosphate Starvation. Plant Physiol. 2016, 170, 499–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Austin, S.; Mayer, A. Phosphate Homeostasis—A Vital Metabolic Equilibrium Maintained Through the INPHORS Signaling Pathway. Front. Microbiol. 2020, 11, 539723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falcone Ferreyra, M.L.; Rius, S.P.; Casati, P. Flavonoids: Biosynthesis, Biological Functions, and Biotechnological Applications. Front. Plant Sci. 2012, 3, 222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jewell, J.B.; Berim, A.; Tripathi, D.; Gleason, C.; Olaya, C.; Pappu, H.R.; Gang, D.R.; Tanaka, K. Activation of Indolic Glucosinolate Pathway by Extracellular ATP in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 2022, 190, 1574–1578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gigolashvili, T.; Berger, B.; Mock, H.P.; Müller, C.; Weisshaar, B.; Flügge, U.I. The Transcription Factor HIG1/MYB51 Regulates Indolic Glucosinolate Biosynthesis in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant J. 2007, 50, 886–901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Bucio, J.; Hernández-Abreu, E.; Sánchez-Calderón, L.; Nieto-Jacobo, M.F.; Simpson, J.; Herrera-Estrella, L. Phosphate Availability Alters Architecture and Causes Changes in Hormone Sensitivity in the Arabidopsis Root System. Plant Physiol. 2002, 129, 244–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsukagoshi, H.; Busch, W.; Benfey, P.N. Transcriptional Regulation of ROS Controls Transition from Proliferation to Differentiation in the Root. Cell 2010, 143, 606–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, R.; Burch, A.Y.; Huppert, K.A.; Tiwari, S.B.; Murphy, A.S.; Guilfoyle, T.J.; Schachtman, D.P. The Arabidopsis Transcription Factor MYB77 Modulates Auxin Signal Transduction. Plant Cell 2007, 19, 2440–2453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Q.; Frugis, G.; Colgan, D.; Chua, N.H. Arabidopsis NAC1 Transduces Auxin Signal Downstream of TIR1 to Promote Lateral Root Development. Genes Dev. 2000, 14, 3024–3036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, T.Y.; Huang, T.K.; Tseng, C.Y.; Lai, Y.S.; Lin, S.I.; Lin, W.Y.; Chen, J.W.; Chioua, T.J. PHO2-Dependent Degradation of PHO1 Modulates Phosphate Homeostasis in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 2012, 24, 2168–2183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aung, K.; Lin, S.I.; Wu, C.C.; Huang, Y.T.; Su, C.L.; Chiou, T.J. Pho2, a Phosphate Overaccumulator, Is Caused by a Nonsense Mutation in a MicroRNA399 Target Gene. Plant Physiol. 2006, 141, 1000–1011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Girke, C.; Daumann, M.; Niopek-Witz, S.; Möhlmann, T. Nucleobase and Nucleoside Transport and Integration into Plant Metabolism. Front. Plant Sci. 2014, 5, 443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Slocum, R.D.; Mejia Peña, C.; Liu, Z. Transcriptional Reprogramming of Nucleotide Metabolism in Response to Altered Pyrimidine Availability in Arabidopsis Seedlings. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14, 1273235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Möhlmann, T.; Bernard, C.; Hach, S.; Ekkehard Neuhaus, H. Nucleoside Transport and Associated Metabolism. Plant Biol. 2010, 12, 26–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, B.; Hoffmann, C.; Möhlmann, T. Arabidopsis Nucleoside Hydrolases Involved in Intracellular and Extracellular Degradation of Purines. Plant J. 2011, 65, 703–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witte, C.P.; Herde, M. Nucleotide Metabolism in Plants. Plant Physiol. 2020, 182, 63–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, J.; Tanaka, K.; Cao, Y.; Qi, Y.; Qiu, J.; Liang, Y.; Lee, S.Y.; Stacey, G. Identification of a Plant Receptor for Extracellular ATP. Science 2014, 343, 290–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pham, A.Q.; Cho, S.H.; Nguyen, C.T.; Stacey, G. Arabidopsis Lectin Receptor Kinase P2K2 Is a Second Plant Receptor for Extracellular ATP and Contributes to Innate Immunity. Plant Physiol. 2020, 183, 1364–1375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Wang, X.; Dong, D.; Guo, L.; Dong, X.; Leng, J.; Zhao, B.; Guo, Y.D.; Zhang, N. Research Advances in Heterotrimeric G-Protein α Subunits and Uncanonical G-Protein Coupled Receptors in Plants. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 8678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aukerman, M.J.; Hirschfeld, M.; Wester, L.; Weaver, M.; Clack, T.; Amasino, R.M.; Sharrock, R.A. A Deletion in the PHYD Gene of the Arabidopsis Wassilewskija Ecotype Defines a Role for Phytochrome D in Red/Far-Red Light Sensing. Plant Cell 1997, 9, 1317–1326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leschevin, M.; Ismael, M.; Quero, A.; San Clemente, H.; Roulard, R.; Bassard, S.; Marcelo, P.; Pageau, K.; Jamet, E.; Rayon, C. Physiological and Biochemical Traits of Two Major Arabidopsis Accessions, Col-0 and Ws, Under Salinity. Front. Plant Sci. 2021, 12, 883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chiu, T.-Y.; Lao, J.; Manalansan, B.; Loqué, D.; Roux, S.J.; Heazlewood, J.L. Biochemical Characterization of Arabidopsis APYRASE Family Reveals Their Roles in Regulating Endomembrane NDP/NMP Homoeostasis. Biochem. J. 2015, 472, 43–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Massalski, C.; Bloch, J.; Zebisch, M.; Steinebrunner, I. The Biochemical Properties of the Arabidopsis Ecto-Nucleoside Triphosphate Diphosphohydrolase AtAPY1 Contradict a Direct Role in Purinergic Signaling. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0115832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, J.; Steinebrunner, I.; Sun, Y.; Butterfield, T.; Torres, J.; Arnold, D.; Gonzalez, A.; Jacob, F.; Reichler, S.; Roux, S.J. Apyrases (Nucleoside Triphosphate-Diphosphohydrolases) Play a Key Role in Growth Control in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 2007, 144, 961–975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, G.; Brown, K.A.; Tripathy, M.K.; Roux, S.J. Recent Advances Clarifying the Structure and Function of Plant Apyrases (Nucleoside Triphosphate Diphosphohydrolases). Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 3283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bozzo, G.G.; Raghothama, K.G.; Plaxton, W.C.; Plaxton, W.C. Purification and Characterization of Two Secreted Purple Acid Phosphatase Isozymes from Phosphate-Starved Tomato (Lycopersicon esculentum) Cell Cultures. Eur. J. Biochem. 2002, 269, 6278–6286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cashikar, A.G.; Kumaresan, R.; Rao, N.M. Biochemical Characterization and Subcellular Localization of the Red Kidney Bean Purple Acid Phosphatase. Plant Physiol. 1997, 114, 907–915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinebrunner, I.; Jeter, C.; Song, C.; Roux, S.J. Molecular and Biochemical Comparison of Two Different Apyrases from Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2000, 38, 913–922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuo, T.; Toyota, M.; Taketa, S. Molecular Cloning of a Root Hairless Gene Rth1 in Rice. Breed. Sci. 2009, 59, 13–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zrenner, R.; Riegler, H.; Marquard, C.R.; Lange, P.R.; Geserick, C.; Bartosz, C.E.; Chen, C.T.; Slocum, R.D. A Functional Analysis of the Pyrimidine Catabolic Pathway in Arabidopsis. New Phytol. 2009, 183, 117–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matthus, E.; Wilkins, K.A.; Mohammad-Sidik, A.; Ning, Y.; Davies, J.M. Spatial Origin of the Extracellular ATP-Induced Cytosolic Calcium Signature in Arabidopsis thaliana Roots: Wave Formation and Variation with Phosphate Nutrition. Plant Biol. 2022, 24, 863–873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, D.E.; Rashotte, A.M.; Murphy, A.S.; Normanly, J.; Tague, B.W.; Peer, W.A.; Taiz, L.; Muday, G.K. Flavonoids Act as Negative Regulators of Auxin Transport in Vivo in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 2001, 126, 524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrášek, J.; Friml, J. Auxin Transport Routes in Plant Development. Development 2009, 136, 2675–2688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tripathy, M.K.; Wang, H.; Slocum, R.D.; Jiang, H.-W.; Nam, J.-C.; Sabharwal, T.; Veerappa, R.; Brown, K.A.; Cai, X.; Allen Faull, P.; et al. Modified Pea Apyrase Has Altered Nuclear Functions and Enhances the Growth of Yeast and Arabidopsis. Front. Plant Sci. 2025, 16, 1584871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lapis-Gaza, H.R.; Jost, R.; Finnegan, P.M. Arabidopsis PHOSPHATE TRANSPORTER1 Genes PHT1;8 and PHT1;9 Are Involved in Root-to-Shoot Translocation of Orthophosphate. BMC Plant Biol. 2014, 14, 334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, G.; Fraley, D.; Steinebrunner, I.; Cervantes, A.; Onyirimba, J.; Liu, A.; Torres, J.; Tang, W.; Kim, J.; Roux, S.J. Extracellular Nucleotides and Apyrases Regulate Stomatal Aperture in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 2011, 156, 1740–1753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, M.R.; Shedge, V.; Kundariya, H.; Lehle, F.R.; Mackenzie, S.A. Ws-2 Introgression in a Proportion of Arabidopsis Thaliana Col-0 Stock Seed Produces Specific Phenotypes and Highlights the Importance of Routine Genetic Verification. Plant Cell 2016, 28, 603–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ye, J.; Coulouris, G.; Zaretskaya, I.; Cutcutache, I.; Rozen, S.; Madden, T.L. Primer-BLAST: A Tool to Design Target-Specific Primers for Polymerase Chain Reaction. BMC Bioinform. 2012, 13, 134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Livak, K.J.; Schmittgen, T.D. Analysis of Relative Gene Expression Data Using Real-Time Quantitative PCR and the 2−ΔΔCT Method. Methods 2001, 25, 402–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lohman, B.K.; Weber, J.N.; Bolnick, D.I. Evaluation of TagSeq, a Reliable Low-Cost Alternative for RNAseq. Mol. Ecol. Resour. 2016, 16, 1315–1321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, C.Y.; Krishnakumar, V.; Chan, A.P.; Thibaud-Nissen, F.; Schobel, S.; Town, C.D. Araport11: A Complete Reannotation of the Arabidopsis thaliana Reference Genome. Plant J. 2017, 89, 789–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Love, M.I.; Huber, W.; Anders, S. Moderated Estimation of Fold Change and Dispersion for RNA-Seq Data with DESeq2. Genome Biol. 2014, 15, 550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Slocum, R.D.; Wang, H.; Cai, X.; Tomasevich, A.A.; Kubecka, K.L.; Clark, G.; Roux, S.J. Role of Apyrase in Mobilization of Phosphate from Extracellular Nucleotides and in Regulating Phosphate Uptake in Arabidopsis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 11857. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262411857

Slocum RD, Wang H, Cai X, Tomasevich AA, Kubecka KL, Clark G, Roux SJ. Role of Apyrase in Mobilization of Phosphate from Extracellular Nucleotides and in Regulating Phosphate Uptake in Arabidopsis. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2025; 26(24):11857. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262411857

Chicago/Turabian StyleSlocum, Robert D., Huan Wang, Xingbo Cai, Alexandra A. Tomasevich, Kameron L. Kubecka, Greg Clark, and Stanley J. Roux. 2025. "Role of Apyrase in Mobilization of Phosphate from Extracellular Nucleotides and in Regulating Phosphate Uptake in Arabidopsis" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 26, no. 24: 11857. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262411857

APA StyleSlocum, R. D., Wang, H., Cai, X., Tomasevich, A. A., Kubecka, K. L., Clark, G., & Roux, S. J. (2025). Role of Apyrase in Mobilization of Phosphate from Extracellular Nucleotides and in Regulating Phosphate Uptake in Arabidopsis. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 26(24), 11857. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262411857