Transcriptomics and Metabolomics Insights into the Dysregulation of Chondrocyte Differentiation Induced by T-2 Toxin

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Transcriptomic Alterations of ATDC5 Cell Lines Induced by T-2 Toxin During Different Differential Stage

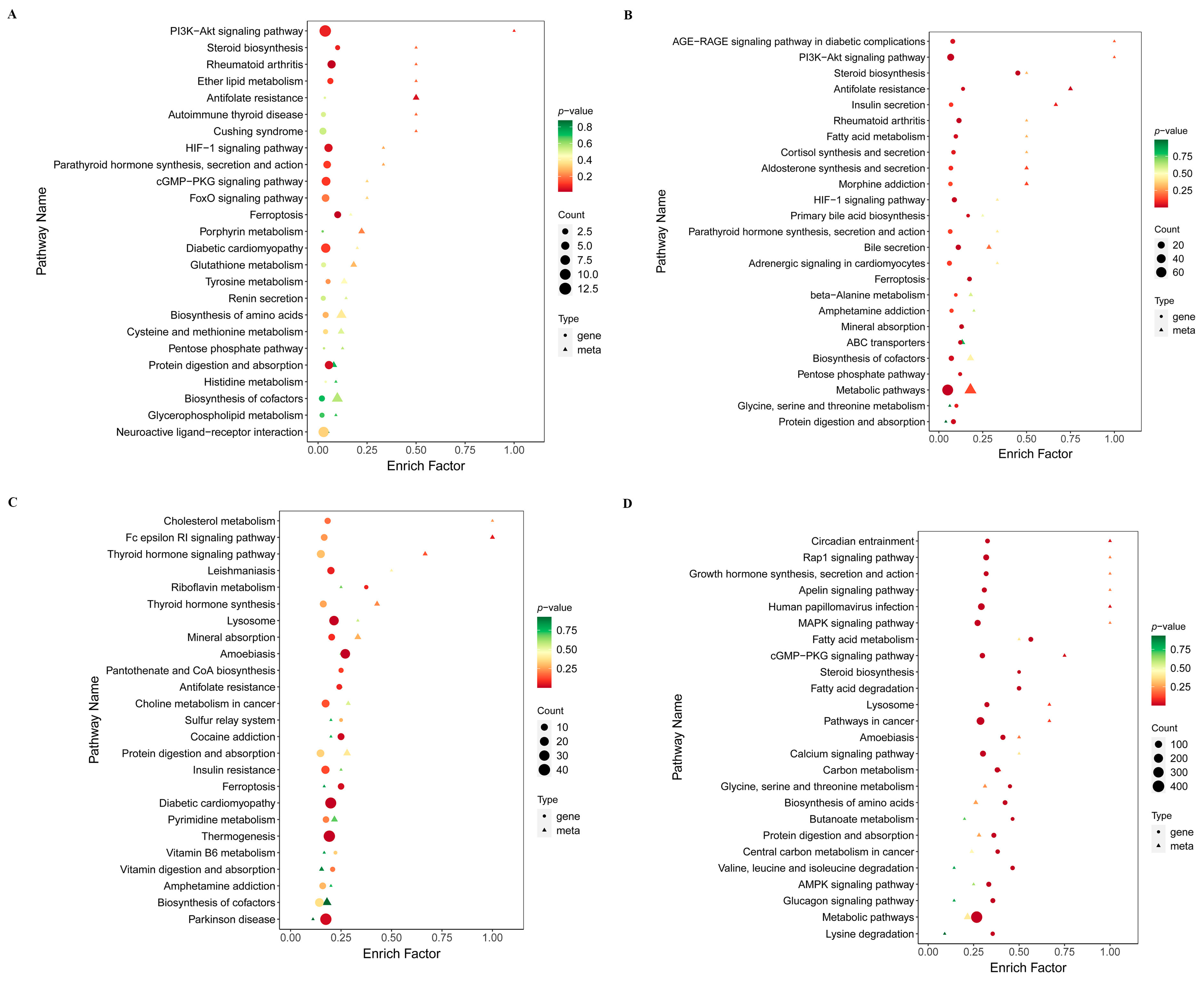

2.2. Widely Targeted Metabolomics Analysis of ATDC5 Cell Lines Induced by T-2 Toxin During Different Differential Stage

2.3. Integration Analysis of Transcriptomic and Metabolomic

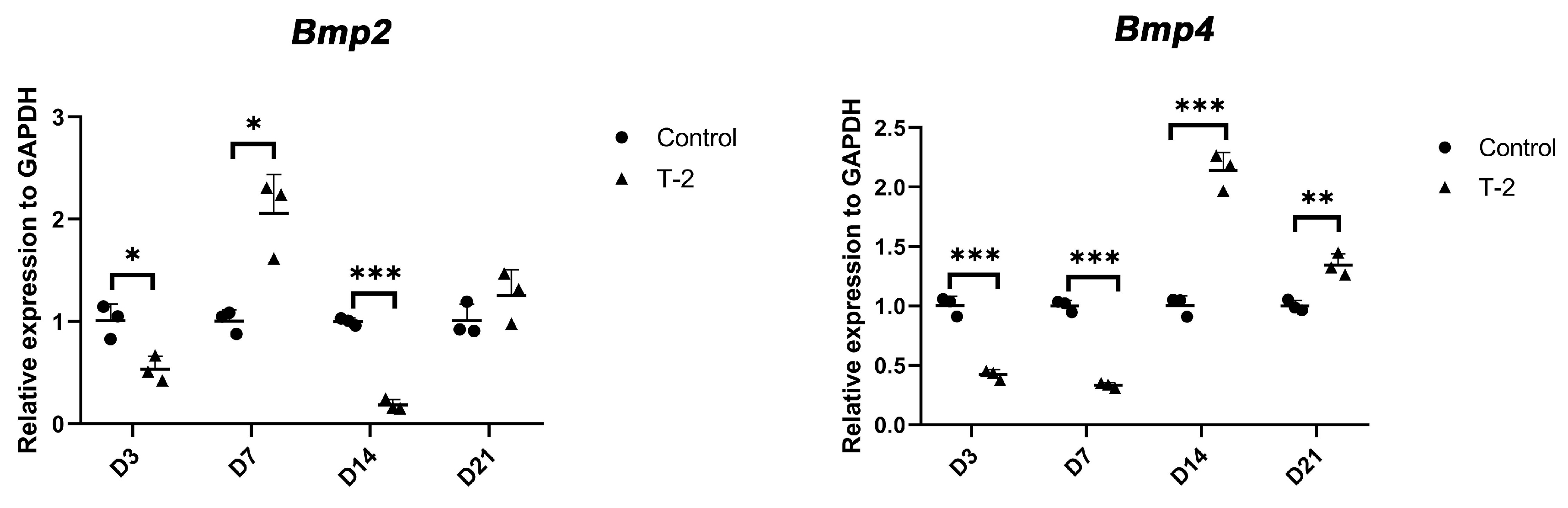

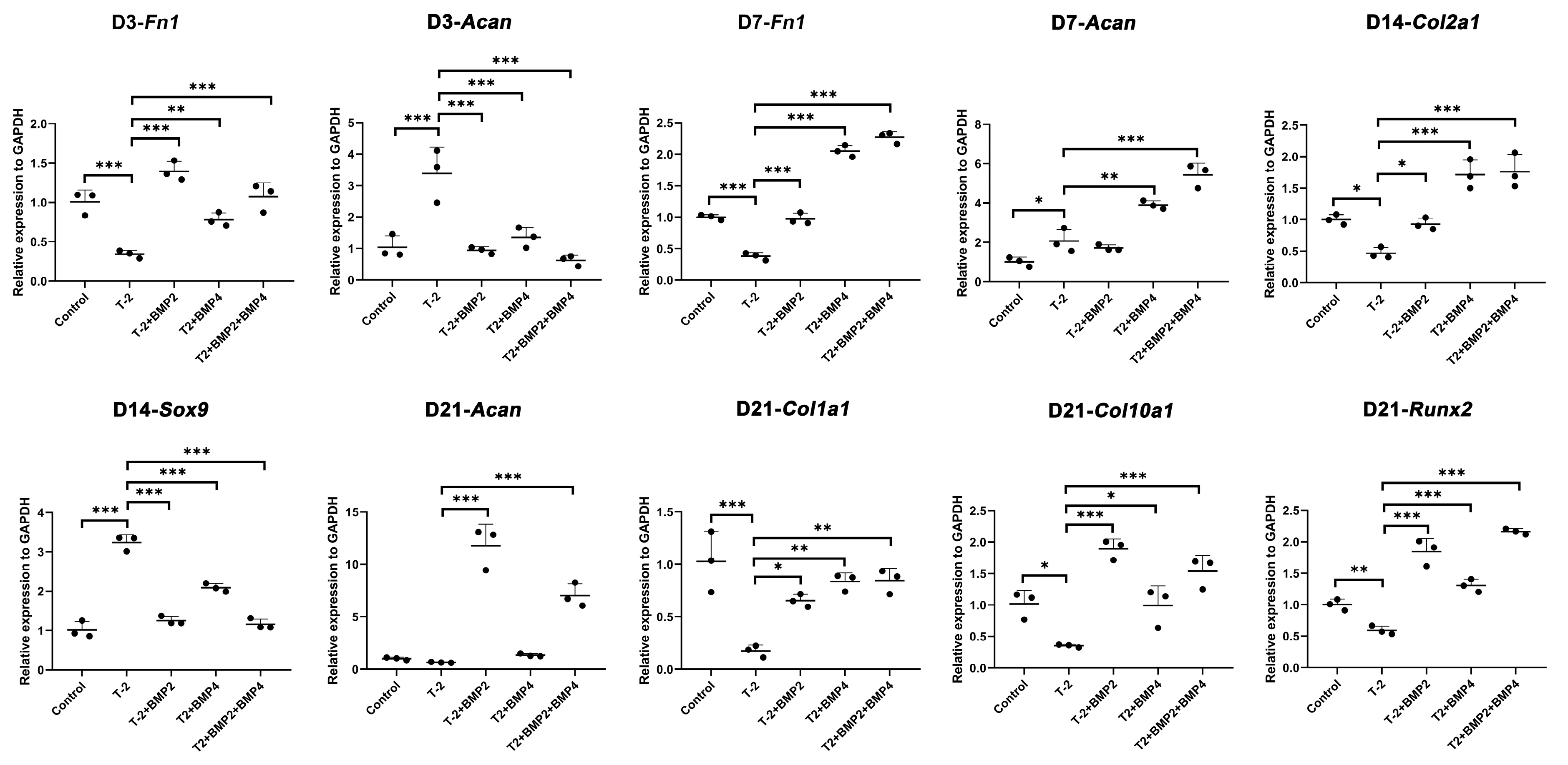

2.4. Intervention of ATDC5 Cells with T-2 Toxin and BMP Recombinant Protein

2.5. Alcian Blue Staining Reveals Impaired Extracellular Matrix Formation Under T-2 Toxin Exposure

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Cell Viability Assay and Sample Preparation

4.2. RNA Sequencing Analysis

4.3. Metabolomic Analysis

4.4. Integrated Analysis of Transcriptomic and Metabolomic Data

4.5. Intervention of ATDC5 Cells with T-2 Toxin and BMP Recombinant Protein

4.6. Quantitative Real-Time Polymerase Chain Reaction Analysis (RT-qPCR)

4.7. Alcian Blue Staining

4.8. Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| KBD | Kashin–Beck disease |

| ITS | Insulin, Transferrin, Selenium |

| CCK8 | cell counting kit-8 |

| DMSO | dimethyl sulfoxide |

| FDR | false discovery rate |

| DEGs | differentially expressed genes |

| GO | Gene Ontology |

| KEGG | Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes |

| LC-ESI-MS/MS | liquid chromatography-electrospray ionization-tandem mass spectrometry |

| PCA | principal component analysis |

| VIP | Variable Importance in Projection |

| FC | fold change |

| OPLS-DA | orthogonal partial least squares discriminant analysis |

| MSEA | metabolite set enrichment analysis |

| HMDB | Human Metabolome Database |

| RT-qPCR | Real-time quantitative polymerase chain reaction |

| PFA | paraformaldehyde |

| SD | standard deviation |

| NC | normal controls |

Appendix A

References

- Janik, E.; Niemcewicz, M.; Podogrocki, M.; Ceremuga, M.; Stela, M.; Bijak, M. T-2 Toxin-The Most Toxic Trichothecene Mycotoxin: Metabolism, Toxicity, and Decontamination Strategies. Molecules 2021, 26, 6868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.-J.; Nie, J.-Y.; Yan, Z.; Li, Z.-X.; Cheng, Y.; Farooq, S. Multi-mycotoxin exposure and risk assessments for Chinese consumption of nuts and dried fruits. J. Integr. Agric. 2018, 17, 1676–1690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nathanail, A.V.; Varga, E.; Meng-Reiterer, J.; Bueschl, C.; Michlmayr, H.; Malachova, A.; Fruhmann, P.; Jestoi, M.; Peltonen, K.; Adam, G.; et al. Metabolism of the Fusarium Mycotoxins T-2 Toxin and HT-2 Toxin in Wheat. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2015, 63, 7862–7872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nazari, L.; Pattori, E.; Terzi, V.; Morcia, C.; Rossi, V. Influence of temperature on infection, growth, and mycotoxin production by Fusarium langsethiae and F. sporotrichioides in durum wheat. Food Microbiol. 2014, 39, 19–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Wang, B.; Wang, P.; Hua, Z.; Zhang, S.; Wang, X.; Yang, X.; Zhang, C. Review of neurotoxicity of T-2 toxin. Mycotoxin Res. 2024, 40, 85–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, C.; Das Gupta, S.; Wang, Z.; Jiang, H.; Velkov, T.; Shen, J. T-2 toxin and its cardiotoxicity: New insights on the molecular mechanisms and therapeutic implications. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2022, 167, 113262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, W.; Wang, Y.; Huang, T.; Liu, Y.; Chen, F.; Chen, Y.; Jiang, Y.; Zhang, C.; Yang, X. T-2 toxin metabolism and its hepatotoxicity: New insights on the molecular mechanism and detoxification. Environ. Pollut. 2023, 330, 121784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, X.; Liu, P.; Cui, Y.; Xiao, B.; Liu, M.; Song, M.; Huang, W.; Li, Y. Review of the Reproductive Toxicity of T-2 Toxin. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2020, 68, 727–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, X.; Liu, H.; Qiao, L.; Deng, H.; Bao, M.; Yang, Z.; He, Y.; Xiang, R.; He, H.; Han, J. Chondrocyte autophagy mediated by T-2 toxin via AKT/TSC/Rheb/mTOR signaling pathway and protective effect of CSA-SeNP. Osteoarthr. Cartil. 2024, 32, 1283–1294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, F.F.; Yu, S.Y.; Sun, L.; Zuo, J.; Luo, K.T.; Wang, M.; Fu, X.L.; Zhang, F.; Huang, H.; Zhou, G.Y.; et al. T-2 toxin induces mitochondrial dysfunction in chondrocytes via the p53-cyclophilin D pathway. J. Hazard. Mater. 2024, 465, 133090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Li, H.; Qi, F.; Yu, Q.; Jiang, H.; Lin, B.; Dong, H.; Li, H.; Yu, J. T-2 toxin induces chondrocyte extracellular matrix degradation by regulating the METTL3-mediated Ctsk m6A modification. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2024, 143 Pt 2, 113390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, G. Diagnostic, clinical and radiological characteristics of Kashin-Beck disease in Shaanxi Province, PR China. Int. Orthop. 2001, 25, 147–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, X.; Ma, W.J.; Zhang, F.; Ren, F.L.; Qu, C.J.; Lammi, M.J. Recent advances in the research of an endemic osteochondropathy in China: Kashin-Beck disease. Osteoarthr. Cartil. 2014, 22, 1774–1783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, M.; Wu, S.; Chen, W.; Li, Y.-P. The roles and regulatory mechanisms of TGF-β and BMP signaling in bone and cartilage development, homeostasis and disease. Cell Res. 2024, 34, 101–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavill, R.; Jennen, D.; Kleinjans, J.; Briedé, J.J. Transcriptomic and metabolomic data integration. Brief. Bioinform. 2016, 17, 891–901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, Z.; Zhong, R.; Yang, Y.; Xia, T.; Wang, W.; Wang, Y.; Xing, N.; Luo, Y.; Li, S.; Shang, L.; et al. Systems pharmacology reveals the mechanism of activity of Ge-Gen-Qin-Lian decoction against LPS-induced acute lung injury: A novel strategy for exploring active components and effective mechanism of TCM formulae. Pharmacol. Res. 2020, 156, 104759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, Y.; Wang, Y. ATDC5: An excellent in vitro model cell line for skeletal development. J. Cell. Biochem. 2013, 114, 1223–1229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Huang, N.; Huang, R.; Wang, L.; Ke, Q.; Cai, L.; Wu, S. Single-cell rna seq analysis identifies the biomarkers and differentiation of chondrocyte in human osteoarthritis. Am. J. Transl. Res. 2020, 12, 7326–7339. [Google Scholar]

- Tian, J.; Yan, J.; Wang, W.; Zhong, N.; Tian, L.; Sun, J.; Min, Z.; Ma, J.; Lu, S. T-2 toxin enhances catabolic activity of hypertrophic chondrocytes through ROS-NF-κB-HIF-2α pathway. Toxicol. Vitr. 2012, 26, 1106–1113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akiyama, H.; Shukunami, C.; Nakamura, T.; Hiraki, Y. Differential expressions of BMP family genes during chondrogenic differentiation of mouse ATDC5 cells. Cell Struct. Funct. 2000, 25, 195–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shukunami, C.; Ohta, Y.; Sakuda, M.; Hiraki, Y. Sequential progression of the differentiation program by bone morphogenetic protein-2 in chondrogenic cell line ATDC5. Exp. Cell Res. 1998, 241, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luyten, F.P.; Chen, P.; Paralkar, V.; Reddi, A.H. Recombinant bone morphogenetic protein-4, transforming growth factor-beta 1, and activin A enhance the cartilage phenotype of articular chondrocytes in vitro. Exp. Cell Res. 1994, 210, 224–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, H.; Xiao, X.; Chilufya, M.M.; Qiao, L.; Lv, Y.; Guo, Z.; Lei, J.; Liu, J.; Zhao, Y.; Zhang, J.; et al. Altered Expression of the Hedgehog Pathway Proteins BMP2, BMP4, SHH, and IHH Involved in Knee Cartilage Damage of Patients with Osteoarthritis and Kashin-Beck Disease. Cartilage 2022, 13, 19476035221087706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyons, K.M.; Pelton, R.W.; Hogan, B.L.M. Organogenesis and pattern formation in the mouse: RNA distribution patterns suggest a role for Bone Morphogenetic Protein-2A (BMP-2A). Development 1990, 109, 833–844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Yan, S.; Qu, C.; Wang, L.; Guo, X.; Han, J. Decreased Expression of CHST-12, CHST-13, and UST in the Proximal Interphalangeal Joint Cartilage of School-Age Children with Kashin–Beck Disease: An Endemic Osteoarthritis in China Caused by Selenium Deficiency. Biol. Trace Elem. Res. 2019, 191, 276–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, H.; Chen, X.; Xue, P.; Ma, X.; Li, J.; Zhang, J. FN1 promotes chondrocyte differentiation and collagen production via TGF-β/PI3K/Akt pathway in mice with femoral fracture. Gene 2021, 769, 145253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Granero-Moltó, F.; Weis, J.A.; Miga, M.I.; Landis, B.; Myers, T.J.; O’Rear, L.; Longobardi, L.; Jansen, E.D.; Mortlock, D.P.; Spagnoli, A. Regenerative Effects of Transplanted Mesenchymal Stem Cells in Fracture Healing. Stem Cells 2009, 27, 1887–1898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; von der Mark, K.; Henry, S.; Norton, W.; Adams, H.; de Crombrugghe, B. Chondrocytes Transdifferentiate into Osteoblasts in Endochondral Bone during Development, Postnatal Growth and Fracture Healing in Mice. PLoS Genet. 2014, 10, e1004820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Guo, X.; Chen, J.; Xu, P.; Lammi, M.J. Morphology and phenotype expression of types I, II, III, and X collagen and MMP-13 of chondrocytes cultured from articular cartilage of Kashin-Beck Disease. J. Rheumatol. 2008, 35, 696. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, M.; Choe, S. BMPs and their clinical potentials. BMB Rep. 2011, 44, 619–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, T.; Fu, X.; Wang, F.; Zhang, X.; Cai, Y.; Wu, X.; Sun, L. The WNT/β-catenin signalling pathway induces chondrocyte apoptosis in the cartilage injury caused by T-2 toxin in rats. Toxicon 2021, 204, 14–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Li, Z.; He, Y.; Liu, Y.; Mi, G.; Chen, J. T-2 toxin induces articular cartilage damage by increasing the expression of MMP-13 via the TGF-β receptor pathway. Hum. Exp. Toxicol. 2022, 41, 9603271221075555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, J.; Wang, L.; Guo, X.; Pang, Q.; Wu, S.; Wu, C.; Xu, P.; Bai, Y. The role of mitochondria in T-2 toxin-induced human chondrocytes apoptosis. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e108394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.N.; Mu, Y.D.; Wang, H.; Zhang, M.; Shi, Y.W.; Mi, G.; Peng, L.X.; Chen, J.H. Endoplasmic reticulum stress pathway mediates T-2 toxin-induced chondrocyte apoptosis. Toxicology 2021, 464, 152989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martí-Pàmies, Í.; Thoonen, R.; Seale, P.; Vite, A.; Caplan, A.; Tamez, J.; Graves, L.; Han, W.; Buys, E.S.; Bloch, D.B.; et al. Deficiency of bone morphogenetic protein-3b induces metabolic syndrome and increases adipogenesis. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 2020, 319, E363–E375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Constant, B.; Kamzolas, I.; Yang, X.; Guo, J.; Rodriguez-Fdez, S.; Mali, I.; Rodriguez-Cuenca, S.; Petsalaki, E.; Vidal-Puig, A.; Li, W. Distinct signalling dynamics of BMP4 and BMP9 in brown versus white adipocytes. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 15971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shukunami, C.; Ishizeki, K.; Atsumi, T.; Ohta, Y.; Suzuki, F.; Hiraki, Y. Cellular hypertrophy and calcification of embryonal carcinoma-derived chondrogenic cell line ATDC5 in vitro. J. Bone Miner. Res. 1997, 12, 1174–1188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Love, M.I.; Huber, W.; Anders, S. Moderated estimation of fold change and dispersion for RNA-seq data with DESeq2. Genome Biol. 2014, 15, 550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, M.D.; McCarthy, D.J.; Smyth, G.K. edgeR: A Bioconductor package for differential expression analysis of digital gene expression data. Bioinformatics 2010, 26, 139–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.; Hwang, S.W.; Kim, S.; Lee, Y.S.; Kim, T.Y.; Lee, S.H.; Kim, S.J.; Yoo, H.J.; Kim, E.N.; Kweon, M.N. Dietary cellulose prevents gut inflammation by modulating lipid metabolism and gut microbiota. Gut Microbes 2020, 11, 944–961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanehisa, M.; Araki, M.; Goto, S.; Hattori, M.; Hirakawa, M.; Itoh, M.; Katayama, T.; Kawashima, S.; Okuda, S.; Tokimatsu, T.; et al. KEGG for linking genomes to life and the environment. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008, 36, D480–D484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sahraeian, S.M.E.; Mohiyuddin, M.; Sebra, R.; Tilgner, H.; Afshar, P.T.; Au, K.F.; Bani Asadi, N.; Gerstein, M.B.; Wong, W.H.; Snyder, M.P.; et al. Gaining comprehensive biological insight into the transcriptome by performing a broad-spectrum RNA-seq analysis. Nat. Commun. 2017, 8, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Group | KEGG Pathway | Description | Biological Relevance |

|---|---|---|---|

| D3_C vs. D3_T2 | ko04216 | Ferroptosis | Early activation of ferroptosis suggests that T-2 toxin triggers oxidative stress and disrupts redox homeostasis at the initial stage of chondrogenic differentiation, potentially impairing BMP–mediated survival and lineage commitment. |

| D3_C vs. D3_T2 | ko05323 | Rheumatoid arthritis | Enrichment of RA-related pathways reflects early induction of inflammation and catabolic activity by T-2 toxin, consistent with ECM degradation and reduced expression of chondrogenic markers. |

| D7_C vs. D7_T2 | ko01100 | Steroid biosynthesis | Disruption of steroid biosynthesis may alter membrane composition and intracellular signaling required for chondrocyte proliferation and differentiation, interfering with TGF-β/BMP-dependent pathways. |

| D7_C vs. D7_T2 | ko04978 | Mineral absorption | Impaired ion homeostasis affects collagen synthesis and enzymatic activities essential for cartilage ECM assembly, compromising the progression of normal chondrogenesis. |

| D14_C vs. D14_T2 | ko04142 | Lysosome | Lysosomal pathway activation indicates enhanced cellular stress, contributing to ECM breakdown and reduced matrix accumulation during the hypertrophic transition phase. |

| D14_C vs. D14_T2 | ko04979 | Cholesterol metabolism | Altered cholesterol homeostasis may impair chondrocyte membrane signaling and metabolic adaptation, weakening anabolic processes required for cartilage maturation. |

| D21_C vs. D21_T2 | ko00480 | Metabolic pathways | Widespread metabolic disruption suggests cumulative toxic effects of T-2 toxin on late-stage cartilage formation, contributing to impaired ECM deposition and skeletal tissue integrity. |

| D21_C vs. D21_T2 | ko01212 | Fatty acid metabolism | Dysregulated lipid metabolism affects energy production and chondrocyte maturation, potentially hindering BMP-7–linked anabolic signaling and matrix synthesis. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Cheng, S.; Liu, H.; Yang, X.; Liu, L.; Cheng, B.; Wen, Y.; Jia, Y.; Zhang, F. Transcriptomics and Metabolomics Insights into the Dysregulation of Chondrocyte Differentiation Induced by T-2 Toxin. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 11858. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262411858

Cheng S, Liu H, Yang X, Liu L, Cheng B, Wen Y, Jia Y, Zhang F. Transcriptomics and Metabolomics Insights into the Dysregulation of Chondrocyte Differentiation Induced by T-2 Toxin. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2025; 26(24):11858. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262411858

Chicago/Turabian StyleCheng, Shiqiang, Huan Liu, Xuena Yang, Li Liu, Bolun Cheng, Yan Wen, Yumeng Jia, and Feng Zhang. 2025. "Transcriptomics and Metabolomics Insights into the Dysregulation of Chondrocyte Differentiation Induced by T-2 Toxin" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 26, no. 24: 11858. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262411858

APA StyleCheng, S., Liu, H., Yang, X., Liu, L., Cheng, B., Wen, Y., Jia, Y., & Zhang, F. (2025). Transcriptomics and Metabolomics Insights into the Dysregulation of Chondrocyte Differentiation Induced by T-2 Toxin. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 26(24), 11858. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262411858