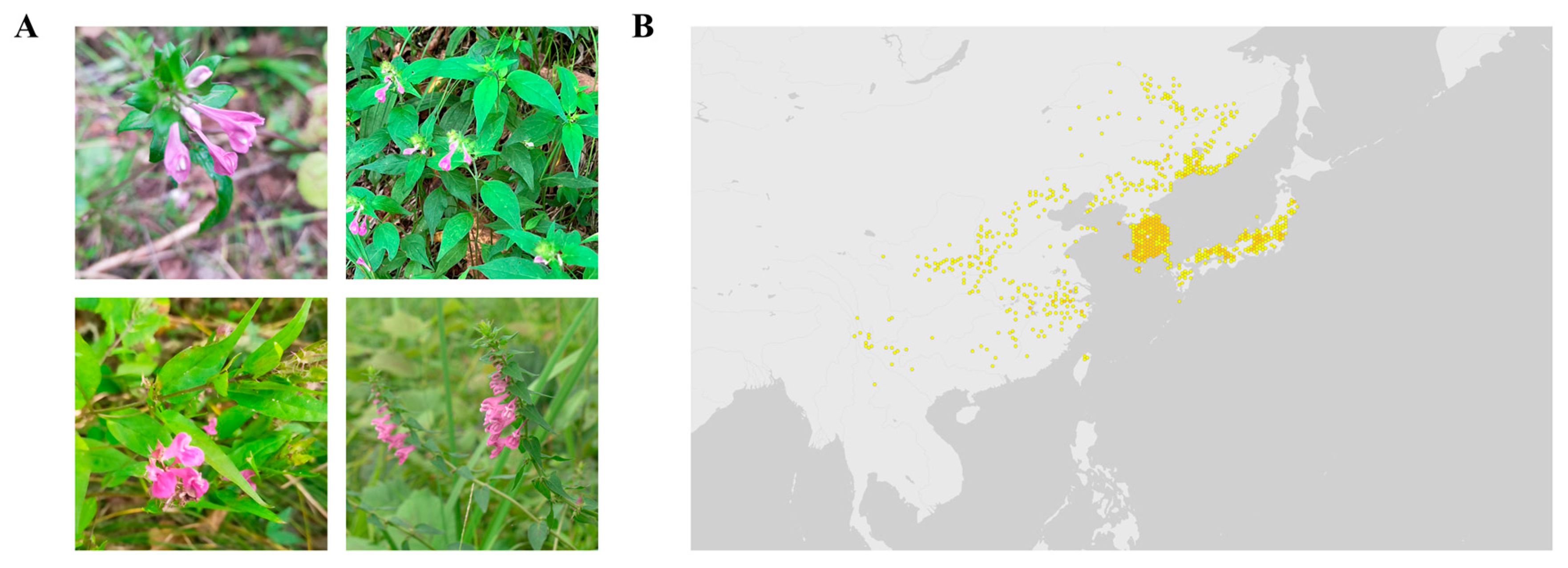

A Multi-Layered Analytical Pipeline Combining Informatics, UHPLC–MS/MS, Network Pharmacology, and Bioassays for Elucidating the Skin Anti-Aging Activity of Melampyrum roseum

Abstract

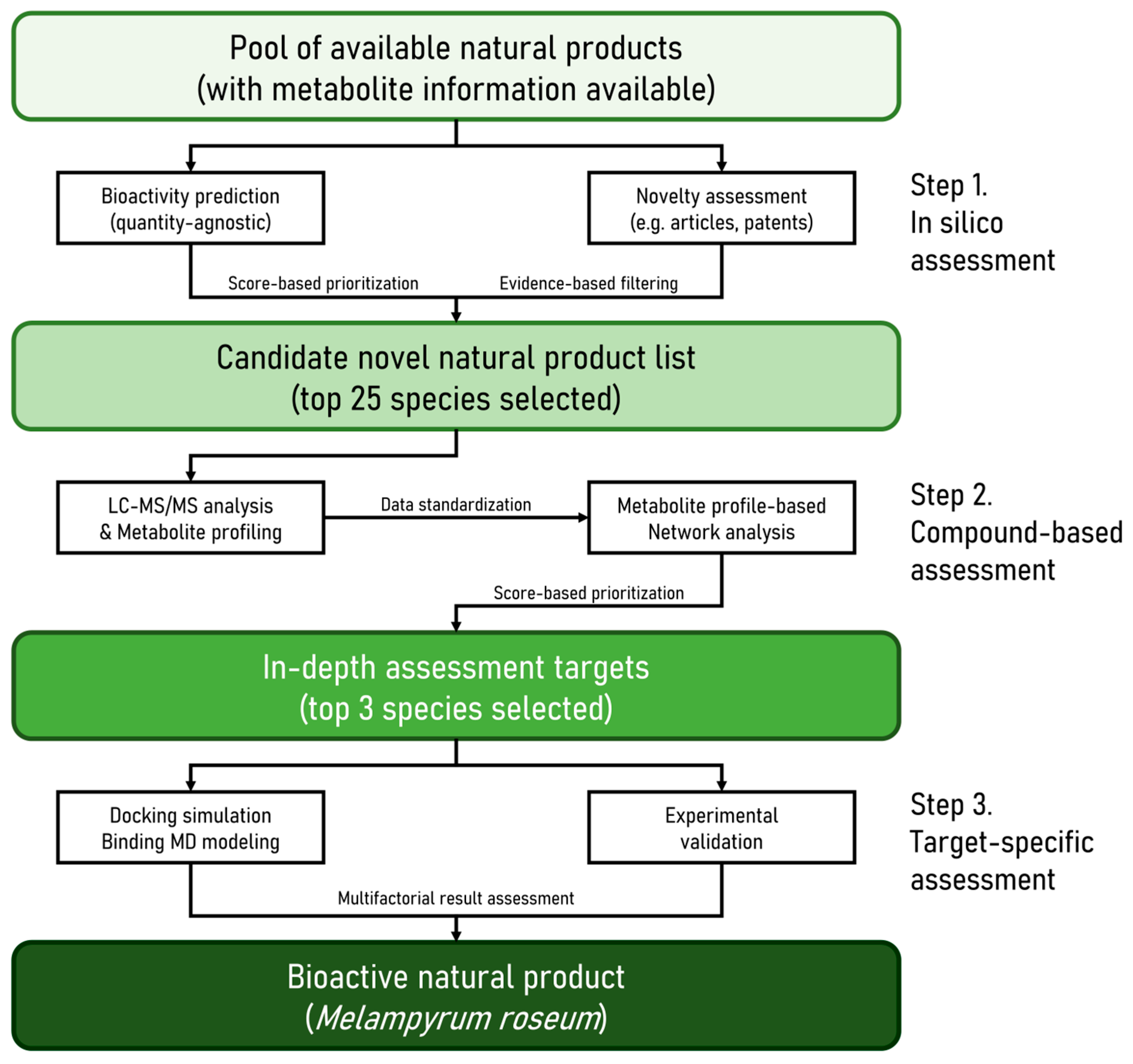

1. Introduction

2. Results

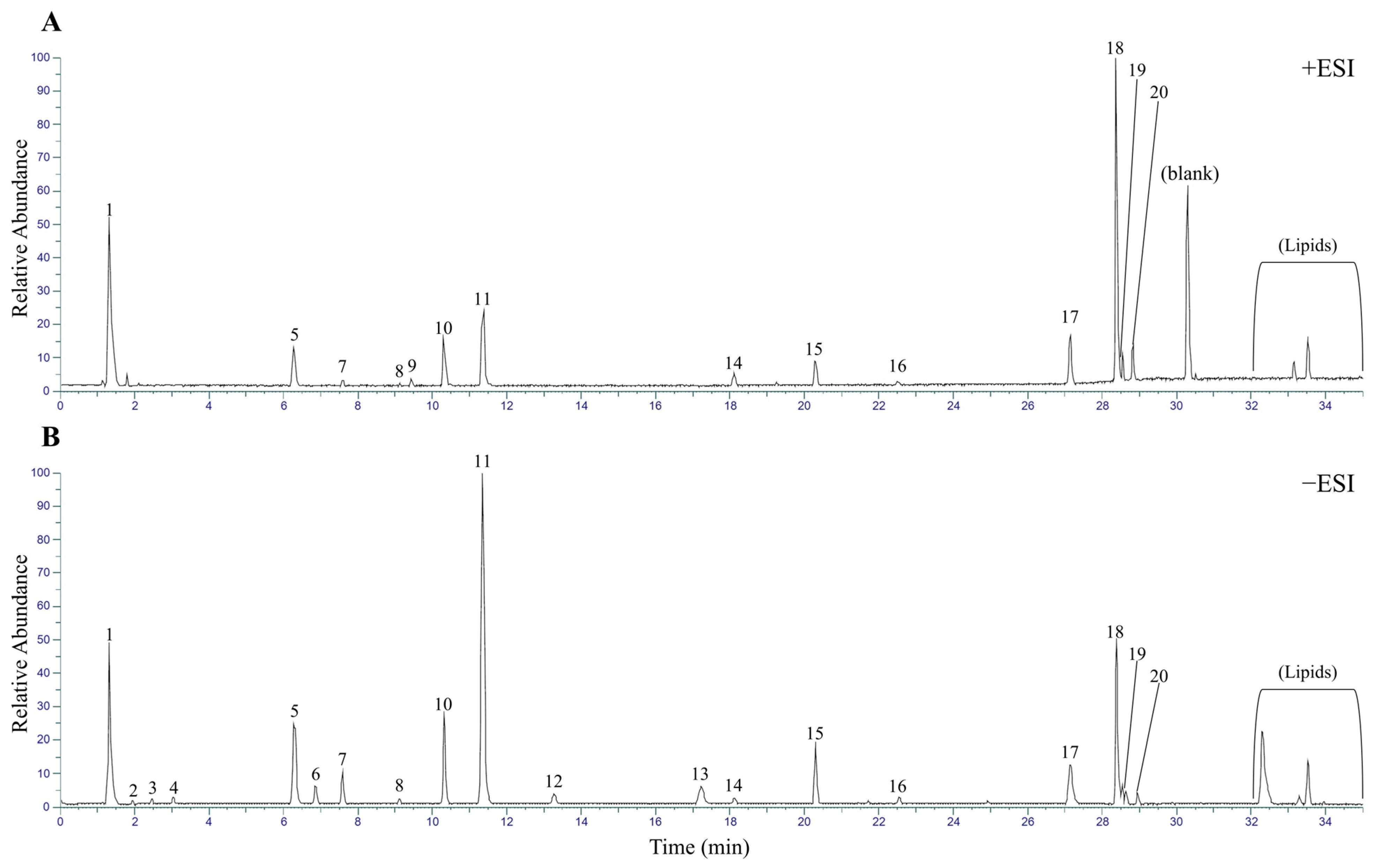

2.1. Metabolite Profiling of M. roseum Extract Using UHPLC-MS/MS

2.2. Identification and Classification of Putative Bioactive Metabolites

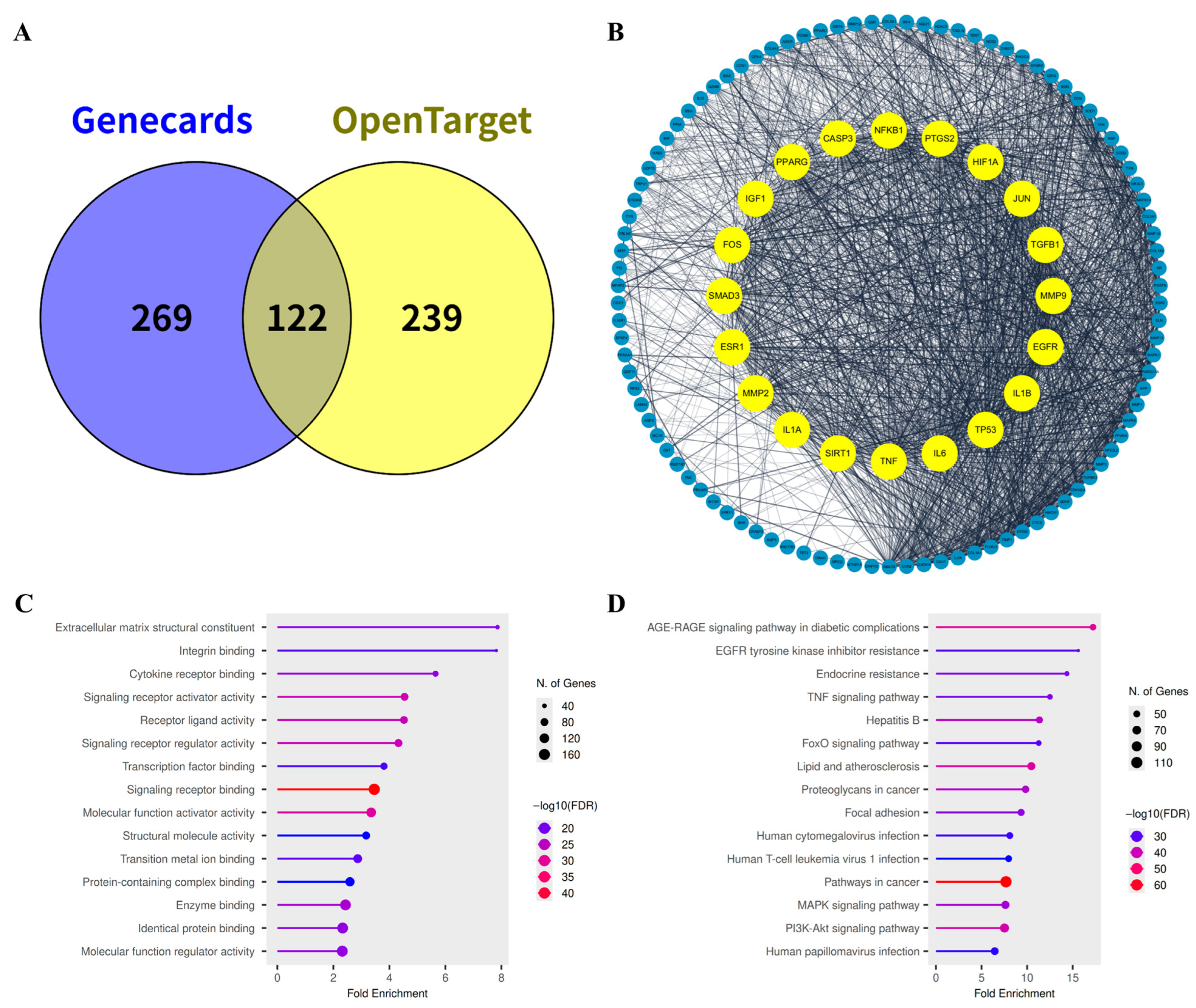

2.3. Identification of Mechanistic Targets Involved in Skin Aging

2.4. Identification of Potential Functional Targets of M. roseum Metabolites

2.5. Network Pharmacology & Pathway Enrichment Analysis

2.6. Molecular Docking and Dynamics Validation

2.6.1. Molecular Docking

2.6.2. MD Simulation

2.7. Experimental Validation

2.7.1. Cell Viability Assessment

2.7.2. Antioxidant Activity Assessment

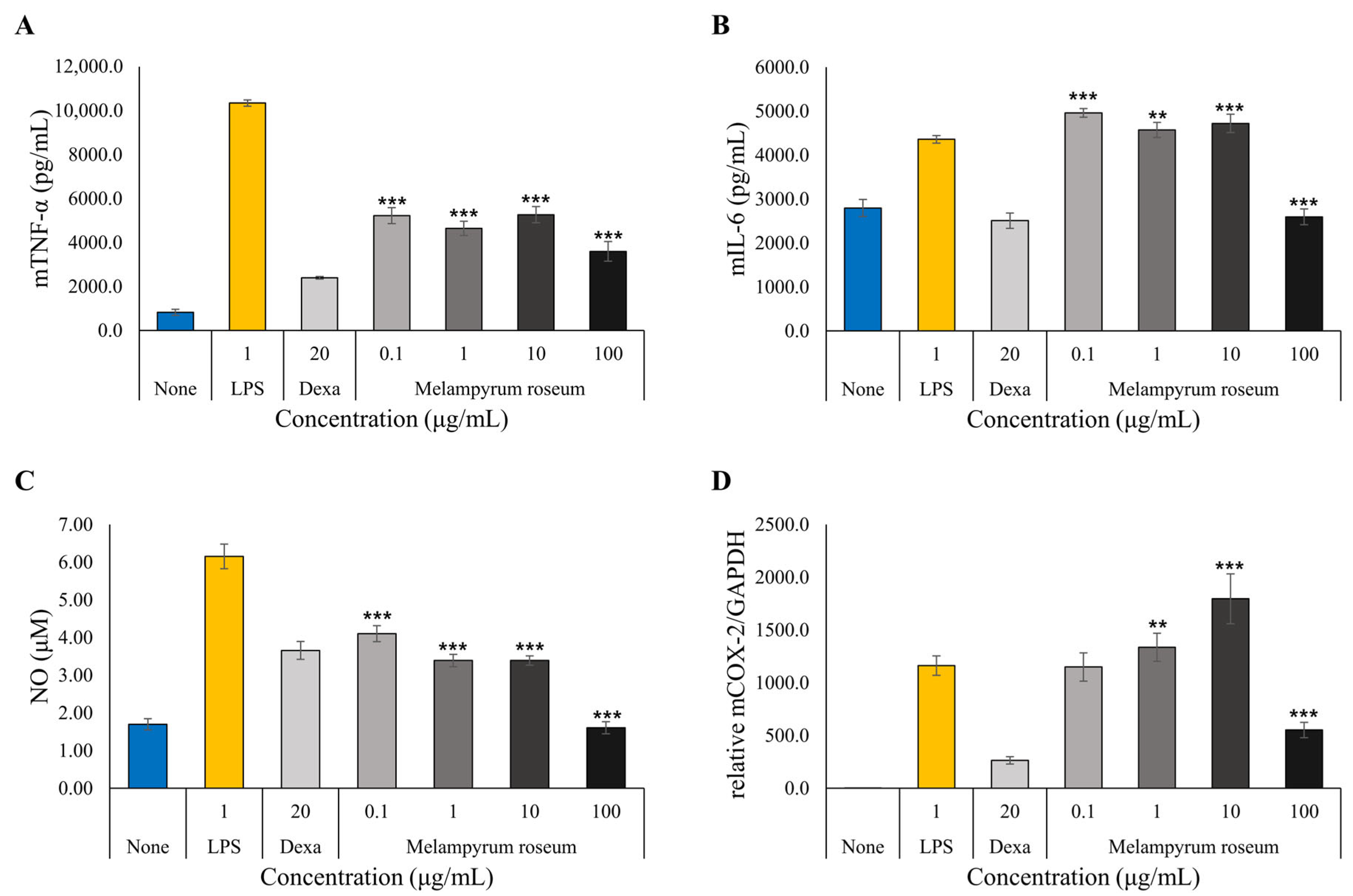

2.7.3. Anti-Inflammatory Activity Assessment

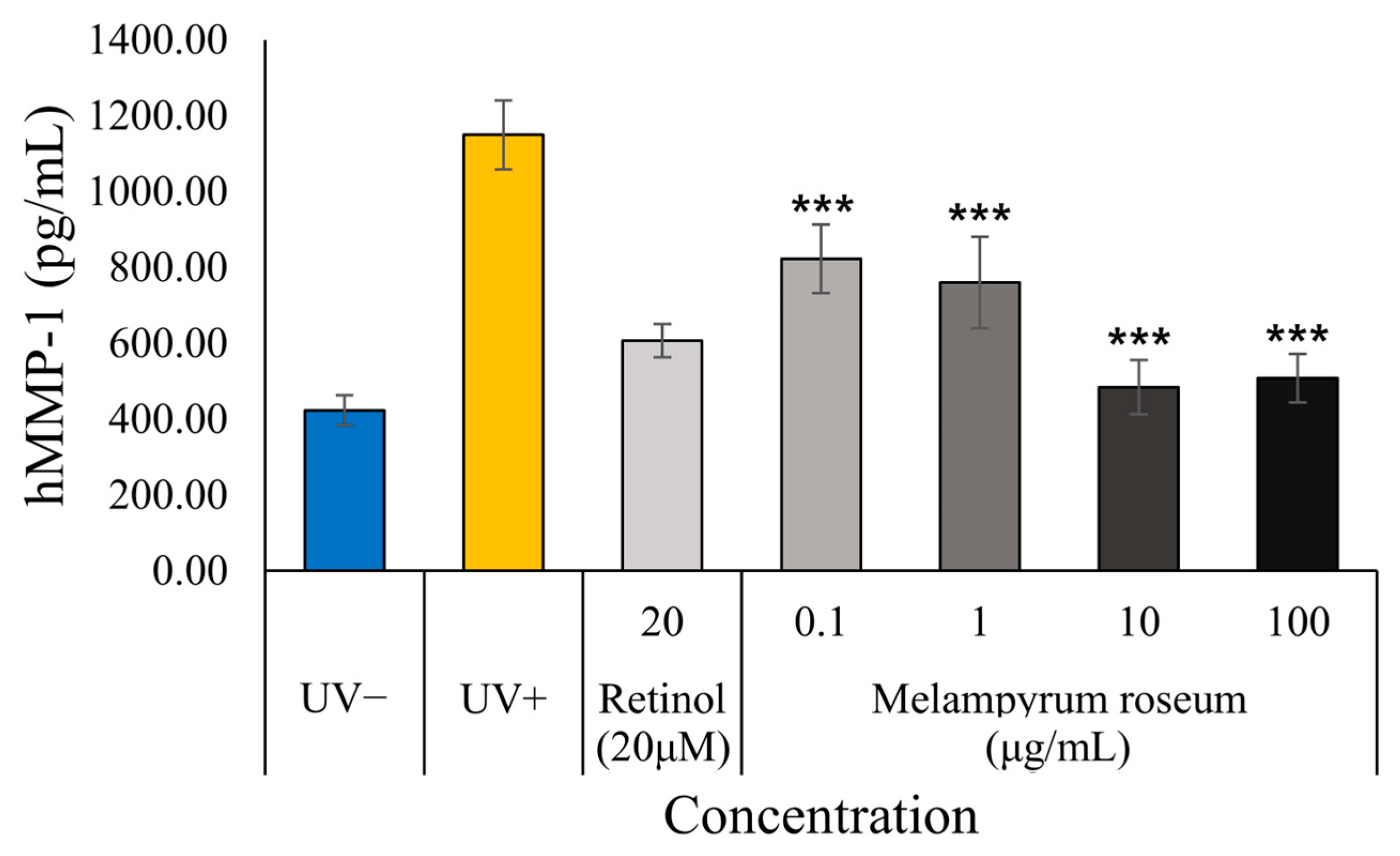

2.7.4. Anti-Photoaging Effect Assessment: Inhibition of MMP-1 Production

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Preparation of Melampyrum roseum Maxim. Extract

4.2. UHPLC–MS/MS Analysis & Metabolite Identification

4.2.1. UHPLC–MS/MS Analysis of M. roseum Extract

4.2.2. Metabolite Identification

4.3. Reference-Based Identification of Potential Targets for Skin Aging

4.4. Metabolite Screening & Compound-Protein Interaction (CPI) Partner Prediction

4.5. Network Pharmacology

4.5.1. Protein-Protein Interaction Network Construction

4.5.2. Pathway Enrichment Analysis

4.6. Molecular Dynamics

4.6.1. Protein Structure Preparation

4.6.2. Molecular Docking

- Selection of the region corresponding to the DNA-binding interface, and

- Identification of potential druggable pockets using the SiteMap module in Maestro.

4.6.3. MD Simulation

4.7. Experimental Validation

4.7.1. MTT Viability Assay

4.7.2. Radical Scavenging Assay

4.7.3. Anti-Inflammatory Activity Assay

4.7.4. Anti-Photoaging Effect Assessment (MMP-1 Assay)

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CPI | Compound-protein interaction |

| ECM | Extracellular matrix |

| GO | Gene ontology |

| HDF | Human dermal fibroblast |

| MD | Molecular dynamics |

| NP | Natural product |

| PPI | Protein-protein interaction |

| RMSD | Root mean square distance |

| ROS | Reactive oxygen species |

| UHPLC | Ultra high performance liquid chromatography |

| UV | Ultraviolet |

References

- Tobin, D.J. Introduction to skin aging. J. Tissue Viability 2017, 26, 37–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varani, J.; Dame, M.K.; Rittie, L.; Fligiel, S.E.; Kang, S.; Fisher, G.J.; Voorhees, J.J. Decreased collagen production in chronologically aged skin: Roles of age-dependent alteration in fibroblast function and defective mechanical stimulation. Am. J. Pathol. 2006, 168, 1861–1868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farage, M.A.; Miller, K.W.; Elsner, P.; Maibach, H.I. Intrinsic and extrinsic factors in skin ageing: A review. Int. J. Cosmet. Sci. 2008, 30, 87–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stout, R.Z.; Birch-Machin, M.A. Mitochondria’s role in skin ageing. Biology 2019, 8, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krutmann, J.; Bouloc, A.; Sore, G.; Bernard, B.A.; Passeron, T. The skin aging exposome. J. Dermatol. Sci. 2017, 85, 152–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisher, G.J.; Kang, S.; Varani, J.; Bata-Csorgo, Z.; Wan, Y.; Datta, S.; Voorhees, J.J. Mechanisms of photoaging and chronological skin aging. Arch. Dermatol. 2002, 138, 1462–1470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pillai, S.; Oresajo, C.; Hayward, J. Ultraviolet radiation and skin aging: Roles of reactive oxygen species, inflammation and protease activation, and strategies for prevention of inflammation-induced matrix degradation. Int. J. Cosmet. Sci. 2005, 27, 17–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rittie, L.; Fisher, G.J. UV-light-induced signal cascades and skin aging. Ageing Res. Rev. 2002, 1, 705–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pizano-Andrade, J.C.; Vargas-Guerrero, B.; Gurrola-Díaz, C.M.; Vargas-Radillo, J.J.; Ruiz-López, M.A. Natural products and their mechanisms in potential photoprotection of the skin. J. Biosci. 2022, 47, 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helfrich, Y.R.; Sachs, D.L.; Voorhees, J.J. Overview of skin aging and photoaging. Dermatol. Nurs. 2008, 20, 177–183. [Google Scholar]

- Narayanan, D.L.; Saladi, R.N.; Fox, J.L. Ultraviolet radiation and skin cancer. Int. J. Dermatol. 2010, 49, 978–986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swiader, A.; Camaré, C.; Guerby, P.; Salvayre, R.; Negre-Salvayre, A. 4-Hydroxynonenal Contributes to Fibroblast Senescence in Skin Photoaging Evoked by UV-A Radiation. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, L.L.; Lim, H.W.; Mohammad, T.F. Sunscreens and Photoaging: A Review of Current Literature. Am. J. Clin. Dermatol. 2021, 22, 819–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milosheska, D.; Roškar, R. Use of Retinoids in Topical Antiaging Treatments: A Focused Review of Clinical Evidence for Conventional and Nanoformulations. Adv. Ther. 2022, 39, 5351–5375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pullar, J.M.; Carr, A.C.; Vissers, M.C.M. The roles of vitamin C in skin health. Nutrients 2017, 9, 866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Connor, A.A.; Lowe, P.M.; Shumack, S.; Lim, A.C. Chemical peels: A review of current practice. Australas. J. Dermatol. 2018, 59, 171–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, T.; Reker, D.; Schneider, P.; Schneider, G. Counting on natural products for drug design. Nat. Chem. 2016, 8, 531–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Newman, D.J.; Cragg, G.M. Natural products as sources of new drugs over the nearly four decades from 01/1981 to 09/2019. J. Nat. Prod. 2020, 83, 770–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atanasov, A.G.; Zotchev, S.B.; Dirsch, V.M.; Supuran, C.T. Natural products in drug discovery: Advances and opportunities. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2021, 20, 200–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feher, M.; Schmidt, J.M. Property distributions: Differences between drugs, natural products, and molecules from combinatorial chemistry. J. Chem. Inf. Comput. Sci. 2003, 43, 218–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harvey, A.L.; Edrada-Ebel, R.; Quinn, R.J. The re-emergence of natural products for drug discovery in the genomics era. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2015, 14, 111–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kirkland, J.L.; Tchkonia, T. Senolytic drugs: From discovery to translation. J. Intern. Med. 2020, 288, 518–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saliev, T.; Singh, P.B. Targeting Senescence: A Review of Senolytics and Senomorphics in Anti-Aging Interventions. Biomolecules 2025, 15, 860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Houghton, C.A.; Fassett, R.G.; Coombes, J.S. Sulforaphane: Translational research from laboratory bench to clinic. Nutr. Rev. 2013, 71, 709–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, Z.Q.; Zheng, S.Y.; Sun, Z.; Luo, Y.; Wang, Y.T.; Yi, P.; Li, Y.S.; Huang, C.; Xiao, W.F. Resveratrol: Molecular Mechanisms, Health Benefits, and Potential Adverse Effects. MedComm 2025, 6, e70252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, H.; Ulrich-Merzenich, G. Synergy research: Approaching a new generation of phytopharmaceuticals. Phytomedicine 2009, 16, 97–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koeberle, A.; Werz, O. Multi-target approach for natural products in inflammation. Drug Discov. Today 2014, 19, 1871–1882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaudêncio, S.P.; Pereira, F. Dereplication: Racing to speed up the natural product discovery process. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2015, 32, 779–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Najmi, A.; Javed, S.A.; Al Bratty, M.; Alhazmi, H.A. Modern Approaches in the Discovery and Development of Plant-Based Natural Products and Their Analogues as Potential Therapeutic Agents. Molecules 2022, 27, 349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, M.; Carver, J.J.; Phelan, V.V.; Sanchez, L.M.; Garg, N.; Peng, Y.; Nguyen, D.D.; Watrous, J.; Kapono, C.A.; Luzzato-Knaan, T.; et al. Sharing and community curation of mass spectrometry data with Global Natural Products Social Molecular Networking. Nat. Biotechnol. 2016, 34, 828–837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, R.; Zhu, X.; Bai, H.; Ning, K. Network pharmacology databases for traditional Chinese medicine: Review and assessment. Front. Pharmacol. 2019, 10, 123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cho, M.H.; Cho, K.H.; No, K.T. PhyloSophos: A high-throughput scientific name mapping algorithm augmented with explicit consideration of taxonomic science, and its application on natural product (NP) occurrence database processing. BMC Bioinform. 2023, 24, 475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cho, M.H. Utilization of Big Data and AI Methodologies for the Discovery of Functional Natural Products. In Proceedings of the 2024 KFN International Symposium and Annual Meeting, Jeju Island, Republic of Korea, 23–25 October 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Cho, M.H. From Data to Discovery: Applying AI and Big Data for Scalable Innovation in Natural Product Research. In Proceedings of the ASNP 2025 The Global Symposium on Natural Products, Jecheon, Republic of Korea, 22–24 September 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, C.H.; Wang, C.M. Melampyrum roseum Maxim. (Scrophulariaceae), a Newly Recorded Genus and Species in Taiwan. Taiwania 2009, 54, 183–186. [Google Scholar]

- Li, H.; Wang, P.; Liu, C.; Wang, Y.; Yang, J. Chemical constituents and pharmacological activities of Pedicularis species. Phytochem. Rev. 2016, 15, 593–617. [Google Scholar]

- Rahmat, E.; Chung, Y.; Nam, H.H.; Lee, A.Y.; Park, J.H.; Kang, Y. Evaluation of Marker Compounds and Biological Activity of In Vitro Regenerated and Commercial Rehmannia glutinosa (Gaertn.) DC. Roots Subjected to Steam Processing. Evid. Based Complement. Altern. Med. 2022, 2022, 1506703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benedec, D.; Oniga, I.; Hanganu, D.; Vlase, A.-M.; Ielciu, I.; Crișan, G.; Fiţ, N.; Niculae, M.; Bab, T.; Pall, E.; et al. Revealing the Phenolic Composition and the Antioxidant, Antimicrobial and Antiproliferative Activities of Two Euphrasia sp. Extracts. Plants 2024, 13, 1790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quan, T.; Qin, Z.; Xia, W.; Shao, Y.; Voorhees, J.J.; Fisher, G.J. Matrix-degrading metalloproteinases in photoaging. J. Investig. Dermatol. Symp. Proc. 2009, 14, 20–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manning, B.D.; Cantley, L.C. AKT/PKB signaling: Navigating downstream. Cell 2007, 129, 1261–1274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aziz, N.; Kim, M.Y.; Cho, J.Y. Anti-inflammatory effects of luteolin: A review of in vitro, in vivo, and in silico studies. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2018, 225, 342–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allemailem, K.S.; Almatroudi, A.; Alharbi, H.O.A.; AlSuhaymi, N.; Alsugoor, M.H.; Aldakheel, F.M.; Khan, A.A.; Rahmani, A.H. Apigenin: A Bioflavonoid with a Promising Role in Disease Prevention and Treatment. Biomedicines 2024, 12, 1353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ambrose, G.O.; Afees, O.J.; Nwamaka, N.C.; Simon, N.; Oluwaseun, A.A.; Soyinka, T.; Oluwaseun, A.S.; Bankole, S. Selection of Luteolin as a potential antagonist from molecular docking analysis of EGFR mutant. Bioinformation 2018, 14, 241–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, J.; Mo, J.; Feng, Y.; Wang, L.; Jiang, H.; Li, J.; Jin, C. Combination of transcriptomic and proteomic approaches helps unravel the mechanisms of luteolin in inducing liver cancer cell death via targeting AKT1 and SRC. Front. Pharmacol. 2024, 15, 1450847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeng, P.; Liu, B.; Wang, Q.; Fan, Q.; Diao, J.X.; Tang, J.; Fu, X.Q.; Sun, X.G. Apigenin Attenuates Atherogenesis through Inducing Macrophage Apoptosis via Inhibition of AKT Ser473 Phosphorylation and Downregulation of Plasminogen Activator Inhibitor-2. Oxidative Med. Cell. Longev. 2015, 2015, 379538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wongkularb, S.; Limboonreung, T.; Tuchinda, P.; Chongthammakun, S. Suppression of PI3K/Akt/mTOR pathway in chrysoeriol-induced apoptosis of rat C6 glioma cells. Vitr. Cell. Dev. Biol. Anim. 2022, 58, 29–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Panche, A.N.; Diwan, A.D.; Chandra, S.R. Flavonoids: An overview. J. Nutr. Sci. 2016, 5, e47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Gong, X.; Bo, A.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, M.; Zang, E.; Zhang, C.; Li, M. Iridoids: Research Advances in Their Phytochemistry, Biological Activities, and Pharmacokinetics. Molecules 2020, 25, 287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alipieva, K.; Korkina, L.; Orhan, I.E.; Georgiev, M.I. Verbascoside—A review of its occurrence, (bio)synthesis and pharmacological significance. Biotechnol. Adv. 2014, 32, 1065–1076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, S.M.; Kim, B.C.; Cho, Y.H.; Choi, K.H.; Chang, J.; Park, M.S.; Kim, M.K.; Cho, K.H.; Kim, J.K. Effects of Flavonoid Compounds on β-amyloid-peptide-induced Neuronal Death in Cultured Mouse Cortical Neurons. Chonnam Med. J. 2014, 50, 45–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rouis-Soussi, L.S.; El Ayeb-Zakhama, A.; Ben Salem, S.; Ben Jannet, H.; Harzallah-Skhiri, F. Isolation of bioactive antioxidant compounds from the aerial parts of Allium roseum var. grandiflorum subvar. typicum Regel. J. Coast. Life Med. 2016, 4, 305–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, W.; Zhong, Y.; Gao, B.; Zheng, B.; Liu, Y. Nrf2-mediated therapeutic effects of dietary flavones in different diseases. Front. Pharmacol. 2023, 14, 1240433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagao, A.; Seki, M.; Kobayashi, H. Inhibition of xanthine oxidase by flavonoids. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 1999, 63, 1787–1790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ryan, M.J.; Jackson, J.R.; Hao, Y.; Leonard, S.S.; Alway, S.E. Inhibition of xanthine oxidase reduces oxidative stress and improves skeletal muscle function in response to electrically stimulated isometric contractions in aged mice. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2011, 51, 38–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Calabrese, E.J.; Mattson, M.P. How does hormesis impact biology, toxicology, and medicine? NPJ Aging Mech. Dis. 2017, 3, 13, Correction in NPJ Aging Mech. Dis. 2023, 9, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vauzour, D. Dietary polyphenols as modulators of brain functions: Biological actions and molecular mechanisms underpinning their beneficial effects. Oxidative Med. Cell. Longev. 2012, 2012, 914273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, T.; Zhang, L.; Joo, D.; Sun, S.C. NF-κB signaling in inflammation. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2017, 2, 17023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Beek, T.A. Chemical analysis of Ginkgo biloba leaves and extracts. J. Chromatogr. A 2002, 967, 21–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Zhang, Y.; Dong, L.; Gao, Q.; Yin, L.; Quan, H.; Chen, R.; Fu, X.; Lin, D. Ethnopharmacology, phytochemistry, and pharmacology of Cornus officinalis Sieb. et Zucc. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2018, 213, 280–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, F.; Chen, M.; Ma, J.; Xie, Y.; Yang, Y.; Yang, C.; Zhou, X.; Chen, D.; Xiao, H.; Dong, X.; et al. Multiomics association analysis of flavonoid glycosides and glycosyltransferases: Insights into the biosynthesis of flavonoid xylosides in Camellia sinensis. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2025, 319, 145490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chuang, S.Y.; Lin, Y.K.; Lin, C.F.; Wang, P.W.; Chen, E.L.; Fang, J.Y. Elucidating the Skin Delivery of Aglycone and Glycoside Flavonoids: How the Structures Affect Cutaneous Absorption. Nutrients 2017, 9, 1304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Li, M.; Yang, Z.; Tao, W.; Wang, P.; Tian, X.; Li, X.; Wang, W. Gardenia jasminoides Ellis: Ethnopharmacology, phytochemistry, and pharmacological and industrial applications of an important traditional Chinese medicine. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2020, 257, 112829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chi, X.; Zhang, F.; Gao, Q.; Xing, R.; Chen, S. A Review on the Ethnomedicinal Usage, Phytochemistry, and Pharmacological Properties of Gentianeae (Gentianaceae) in Tibetan Medicine. Plants 2021, 10, 2383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schymanski, E.L.; Jeon, J.; Gulde, R.; Fenner, K.; Ruff, M.; Singer, H.P.; Hollender, J. Identifying small molecules via high resolution mass spectrometry: Communicating confidence. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2014, 48, 2097–2098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, J.; Jin, H.; Kim, J.; Cho, S.Y.; Moon, S.; Wang, J.; Mao, J.; No, K.T. Leveraging the Fragment Molecular Orbital and MM-GBSA Methods in Virtual Screening for the Discovery of Novel Non-Covalent Inhibitors Targeting the TEAD Lipid Binding Pocket. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 5358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| No. | Molecule Name | RT | Monoisotopic Mass | Molecular Formula | Intensity (POS) | Intensity (N × 10 G) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3 | Aucubin | 2.47 | 346.1264 | C15H22O9 | ND | 1.33 × 106 |

| 4 | Geniposidic acid | 3.05 | 374.1213 | C16H22O10 | ND | 1.62 × 106 |

| 5 | Loganic acid | 6.27 | 393.1634 | C16H24O10 | 2.56 × 106 | 1.39 × 107 |

| 6 | Mussaenosidic acid | 6.85 | 393.1634 | C16H24O10 | 3.73 × 105 | 3.20 × 106 |

| 7 | Secologanin | 7.59 | 388.1369 | C17H24O10 | 7.26 × 105 | 5.92 × 106 |

| 10 | Loganin | 10.3 | 390.1514 | C17H26O10 | 2.99 × 106 | 1.48 × 107 |

| 11 | Mussaenoside | 11.38 | 390.1514 | C17H26O10 | 5.94 × 106 | 5.53 × 107 |

| 14 | Hyperoside | 18.1 | 464.0953 | C21H20O12 | 1.06 × 106 | 1.48 × 106 |

| 15 | (iso)verbascoside | 20.31 | 624.2054 | C29H36O15 | 1.80 × 106 | 1.01 × 107 |

| 16 | Apigenin glucuronide | 22.53 | 446.0849 | C21H18O11 | 6.26 × 105 | 1.80 × 106 |

| 17 | Luteolin | 27.14 | 286.0472 | C15H10O6 | 3.36 × 106 | 6.94 × 106 |

| 18 | Apigenin | 28.37 | 270.0522 | C15H10O5 | 2.21 × 107 | 2.72 × 107 |

| 19 | Chrysoeriol | 28.55 | 300.0627 | C16H12O6 | 2.46 × 106 | 3.58 × 106 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Cho, M.H.; Ha, J.; Jin, H.; An, S.; Chu, S. A Multi-Layered Analytical Pipeline Combining Informatics, UHPLC–MS/MS, Network Pharmacology, and Bioassays for Elucidating the Skin Anti-Aging Activity of Melampyrum roseum. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 11853. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262411853

Cho MH, Ha J, Jin H, An S, Chu S. A Multi-Layered Analytical Pipeline Combining Informatics, UHPLC–MS/MS, Network Pharmacology, and Bioassays for Elucidating the Skin Anti-Aging Activity of Melampyrum roseum. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2025; 26(24):11853. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262411853

Chicago/Turabian StyleCho, Min Hyung, JangHo Ha, Haiyan Jin, SoHee An, and SungJune Chu. 2025. "A Multi-Layered Analytical Pipeline Combining Informatics, UHPLC–MS/MS, Network Pharmacology, and Bioassays for Elucidating the Skin Anti-Aging Activity of Melampyrum roseum" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 26, no. 24: 11853. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262411853

APA StyleCho, M. H., Ha, J., Jin, H., An, S., & Chu, S. (2025). A Multi-Layered Analytical Pipeline Combining Informatics, UHPLC–MS/MS, Network Pharmacology, and Bioassays for Elucidating the Skin Anti-Aging Activity of Melampyrum roseum. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 26(24), 11853. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262411853