Complex Relationships Between Homologous Recombination Deficiency (HRD) Score and Mutational Status of Homologous Recombination Repair (HRR) Genes in Prostate Carcinomas

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

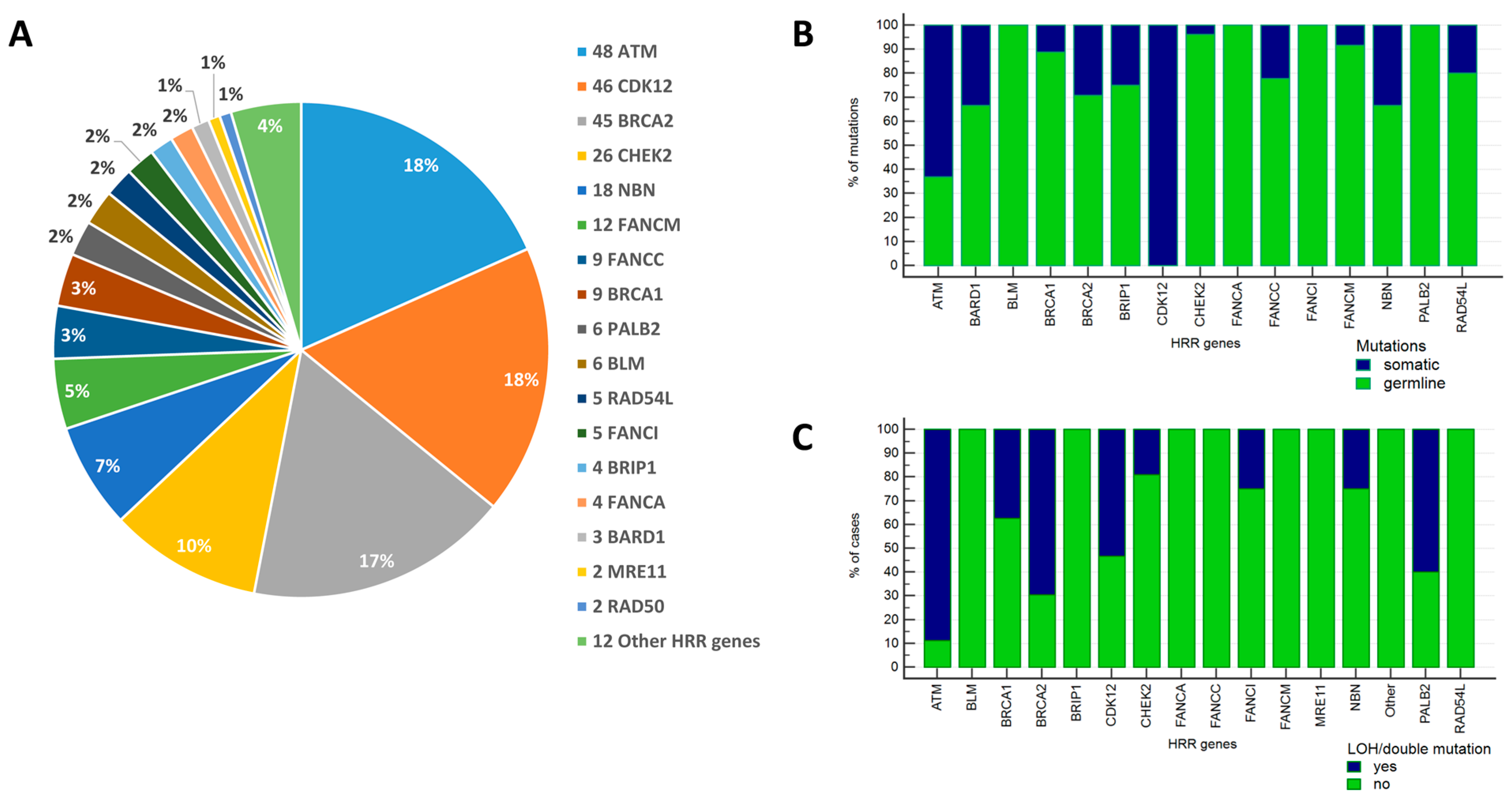

2.1. Frequency and Spectrum of Mutations in HRR Genes

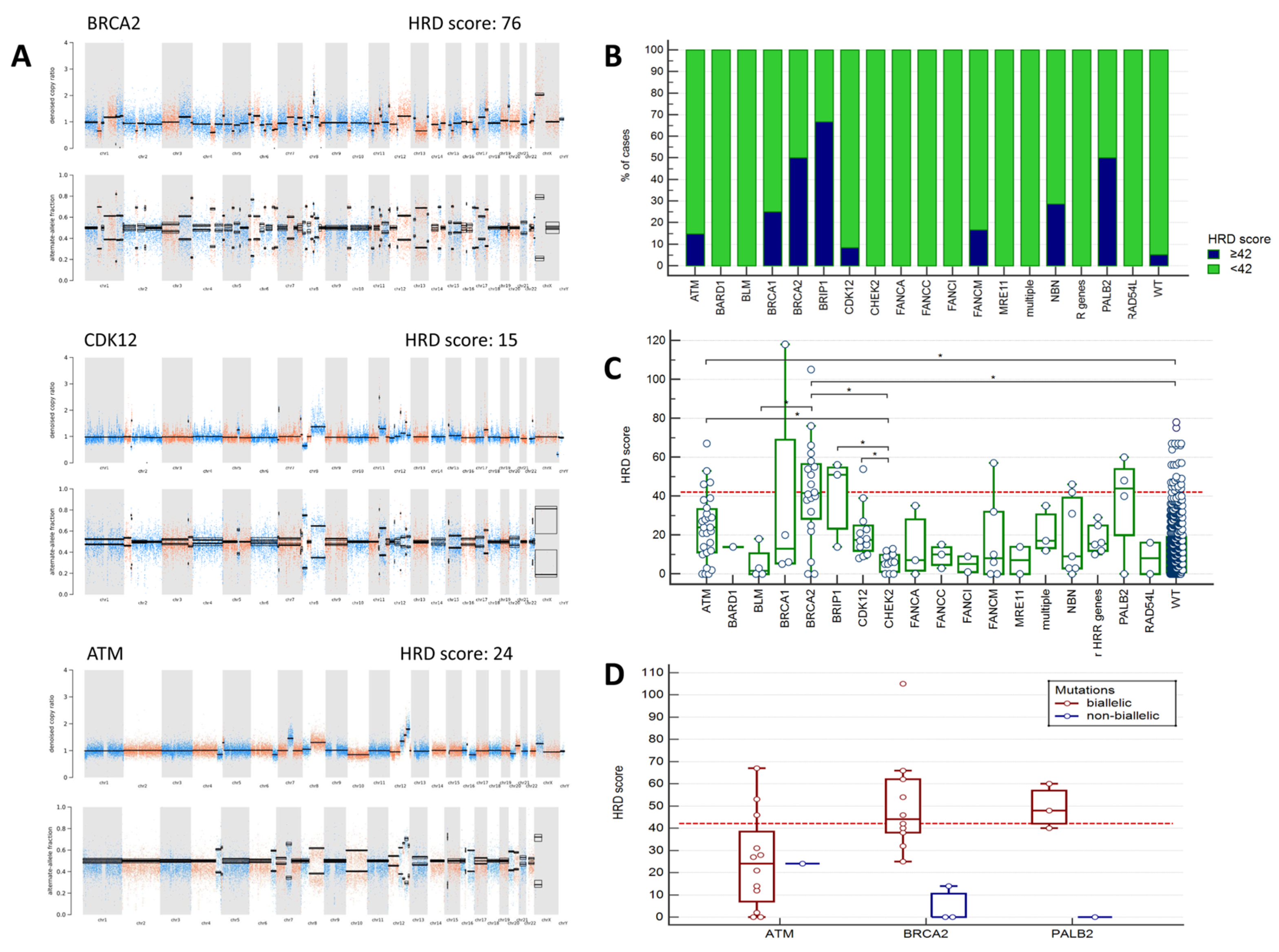

2.2. Analysis of HRD Scores

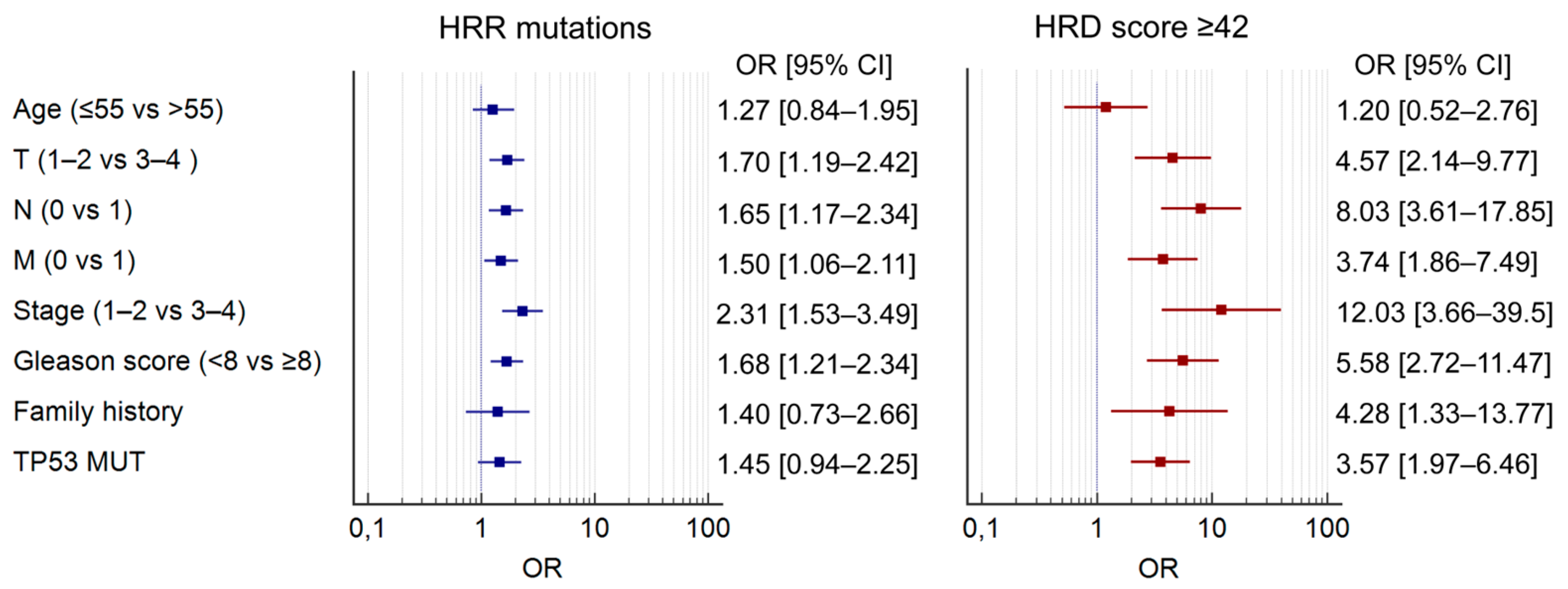

2.3. Clinicopathological Associations

3. Discussion

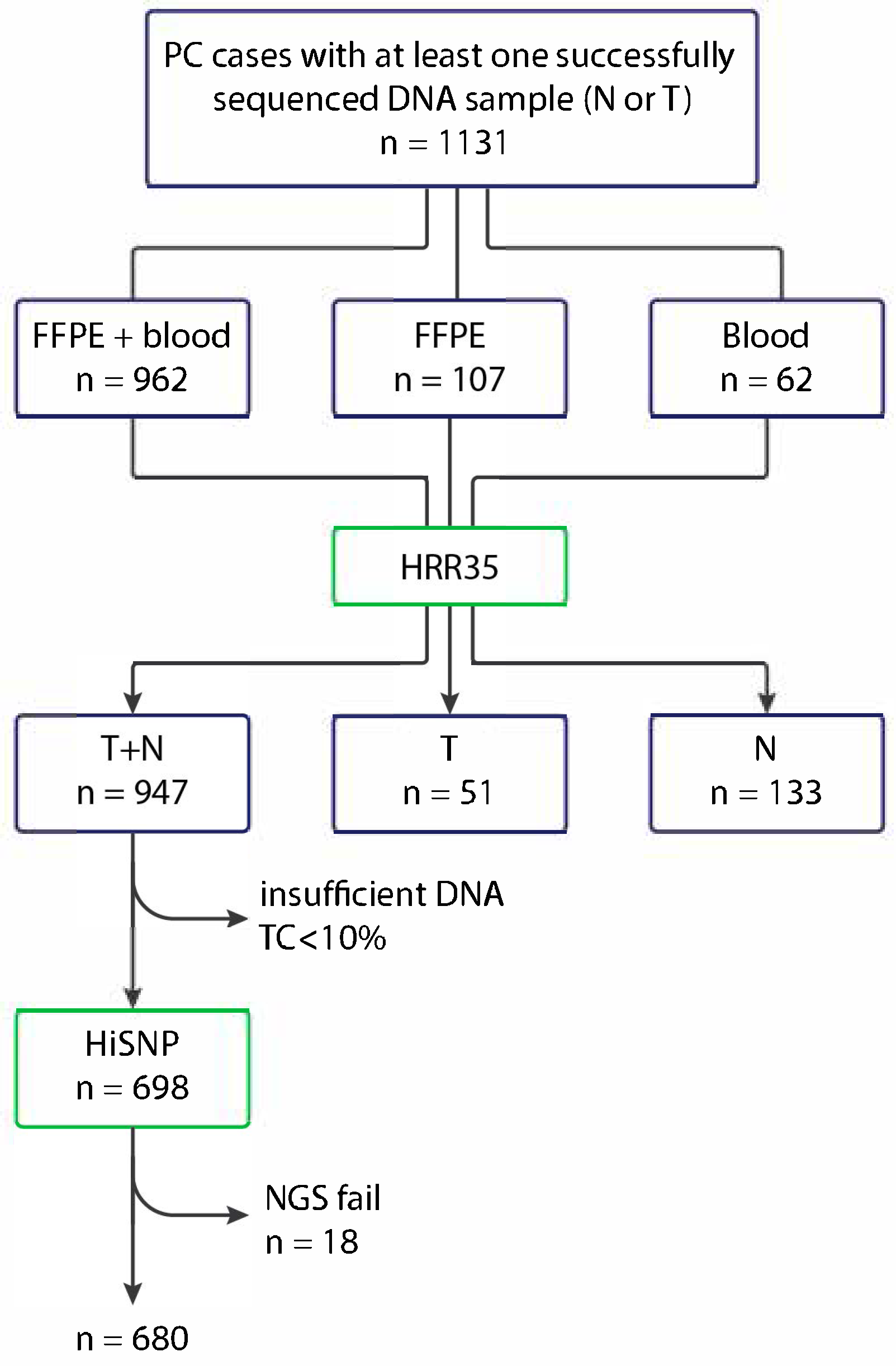

4. Materials and Methods

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CI | Confidence interval |

| HRD | Homologous recombination deficiency |

| HRR | Homologous recombination repair |

| LOH | Loss of heterozygosity |

| mCRPC | Metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer |

| OR | Odds ratio |

| PARPi | Poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase inhibitors |

| PC | Prostate cancer |

References

- Robinson, D.; van Allen, E.M.; Wu, Y.M.; Schultz, N.; Lonigro, R.J.; Mosquera, J.M.; Montgomery, B.; Taplin, M.E.; Pritchard, C.C.; Attard, G.; et al. Integrative Clinical Genomics of Advanced Prostate Cancer. Cell 2015, 162, 454, Erratum in Cell 2015, 162, 454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pritchard, C.C.; Mateo, J.; Walsh, M.F.; De Sarkar, N.; Abida, W.; Beltran, H.; Garofalo, A.; Gulati, R.; Carreira, S.; Eeles, R.; et al. Inherited DNA-Repair Gene Mutations in Men with Metastatic Prostate Cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2016, 375, 443–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fenor de la Maza, M.D.; Pérez Gracia, J.L.; Miñana, B.; Castro, E. PARP inhibitors alone or in combination for prostate cancer. Ther. Adv. Urol. 2024, 16, 17562872241272929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Bono, J.; Mateo, J.; Fizazi, K.; Saad, F.; Shore, N.; Sandhu, S.; Chi, K.N.; Sartor, O.; Agarwal, N.; Olmos, D.; et al. Olaparib for Metastatic Castration-Resistant Prostate Cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 382, 2091–2102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Bono, J.S.; Mehra, N.; Scagliotti, G.V.; Castro, E.; Dorff, T.; Stirling, A.; Stenzl, A.; Fleming, M.T.; Higano, C.S.; Saad, F.; et al. Talazoparib monotherapy in metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer with DNA repair alterations (TALAPRO-1): An open-label; phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2021, 9, 1250–1264, Erratum in Lancet Oncol. 2022, 23, e207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agarwal, N.; Azad, A.A.; Carles, J.; Fay, A.P.; Matsubara, N.; Szczylik, C.; De Giorgi, U.; Young Joung, J.; Fong, P.C.C.; Voog, E.; et al. Talazoparib plus enzalutamide in men with metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer: Final overall survival results from the randomised; placebo-controlled; phase 3 TALAPRO-2 trial. Lancet 2025, 406, 447–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stopsack, K.H. Efficacy of PARP inhibition in metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer is very different with non-BRCA DNA repair alterations: Reconstructing prespecified endpoints for cohort B from the phase 3 PROfound trial of olaparib. Eur. Urol. 2021, 79, 442–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Póti, Á.; Gyergyák, H.; Németh, E.; Rusz, O.; Tóth, S.; Kovácsházi, C.; Chen, D.; Szikriszt, B.; Spisák, S.; Takeda, S.; et al. Correlation of homologous recombination deficiency induced mutational signatures with sensitivity to PARP inhibitors and cytotoxic agents. Genome Biol. 2019, 20, 240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fallah, J.; Xu, J.; Weinstock, C.; Gao, X.; Heiss, B.L.; Maguire, W.F.; Chang, E.; Agrawal, S.; Tang, S.; Amiri-Kordestani, L.; et al. Efficacy of Poly(ADP-ribose) Polymerase Inhibitors by Individual Genes in Homologous Recombination Repair Gene-Mutated Metastatic Castration-Resistant Prostate Cancer: A US Food and Drug Administration Pooled Analysis. J. Clin. Oncol. 2024, 42, 1687–1698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abida, W.; Campbell, D.; Patnaik, A.; Bryce, A.H.; Shapiro, J.; Bambury, R.M.; Zhang, J.; Burke, J.M.; Castellano, D.; Font, A.; et al. Rucaparib for the Treatment of Metastatic Castration-resistant Prostate Cancer Associated with a DNA Damage Repair Gene Alteration: Final Results from the Phase 2 TRITON2 Study. Eur. Urol. 2023, 84, 21–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, M.R.; Scher, H.I.; Sandhu, S.; Efstathiou, E.; Lara, P.N., Jr.; Yu, E.Y.; George, D.J.; Chi, K.N.; Saad, F.; Ståhl, O.; et al. Niraparib in patients with metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer and DNA repair gene defects (GALAHAD): A multicentre; open-label; phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2022, 23, 362–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilkes, D.C.; Sailer, V.; Xue, H.; Cheng, H.; Collins, C.C.; Gleave, M.; Wang, Y.; Demichelis, F.; Beltran, H.; Rubin, M.A.; et al. A germline FANCA alteration that is associated with increased sensitivity to DNA damaging agents. Cold Spring Harb. Mol. Case Stud. 2017, 3, a001487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polak, P.; Kim, J.; Braunstein, L.Z.; Karlic, R.; Haradhavala, N.J.; Tiao, G.; Rosebrock, D.; Livitz, D.; Kübler, K.; Mouw, K.W.; et al. A mutational signature reveals alterations underlying deficient homologous recombination repair in breast cancer. Nat. Genet. 2017, 49, 1476–1486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, L.W.M.; Martens, J.; van Hoeck, A.; Cuppen, E. Pan-cancer landscape of homologous recombination deficiency. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 5584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dillon, K.M.; Bekele, R.T.; Sztupinszki, Z.; Hanlon, T.; Rafiei, S.; Szallasi, Z.; Choudhury, A.D.; Mouw, K.W. PALB2 or BARD1 loss confers homologous recombination deficiency and PARP inhibitor sensitivity in prostate cancer. npj Precis. Oncol. 2022, 6, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Torres-Esquius, S.; Llop-Guevara, A.; Gutiérrez-Enríquez, S.; Romey, M.; Teulé, À.; Llort, G.; Herrero, A.; Sánchez-Henarejos, P.; Vallmajó, A.; González-Santiago, S.; et al. Prevalence of Homologous Recombination Deficiency Among Patients With Germline RAD51C/D Breast or Ovarian Cancer. JAMA Netw. Open 2024, 7, e247811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davies, H.; Glodzik, D.; Morganella, S.; Yates, L.R.; Staaf, J.; Zou, X.; Ramakrishna, M.; Martin, S.; Boyault, S.; Sieuwerts, A.M.; et al. HRDetect is a predictor of BRCA1 and BRCA2 deficiency based on mutational signatures. Nat. Med. 2017, 23, 517–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quigley, D.A.; Dang, H.X.; Zhao, S.G.; Lloyd, P.; Aggarwal, R.; Alumkal, J.J.; Foye, A.; Kothari, V.; Perry, M.D.; Bailey, A.M.; et al. Genomic Hallmarks and Structural Variation in Metastatic Prostate Cancer. Cell 2018, 174, 758–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Telli, M.L.; Timms, K.M.; Reid, J.; Hennessy, B.; Mills, G.B.; Jensen, K.C.; Szallasi, Z.; Barry, W.T.; Winer, E.P.; Tung, N.M.; et al. Homologous Recombination Deficiency (HRD) Score Predicts Response to Platinum-Containing Neoadjuvant Chemotherapy in Patients with Triple-Negative Breast Cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 2016, 22, 3764–3773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirza, M.R.; Monk, B.J.; Herrstedt, J.; Oza, A.M.; Mahner, S.; Redondo, A.; Fabbro, M.; Ledermann, J.A.; Lorusso, D.; Vergote, I.; et al. Niraparib Maintenance Therapy in Platinum-Sensitive; Recurrent Ovarian Cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2016, 375, 2154–2164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swisher, E.M.; Lin, K.K.; Oza, A.M.; Scott, C.L.; Giordano, H.; Sun, J.; Konecny, G.E.; Coleman, R.L.; Tinker, A.V.; O’Malley, D.M.; et al. Rucaparib in relapsed; platinum-sensitive high-grade ovarian carcinoma (ARIEL2 Part 1): An international; multicentre; open-label; phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2017, 18, 75–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coleman, R.L.; Oza, A.M.; Lorusso, D.; Aghajanian, C.; Oaknin, A.; Dean, A.; Colombo, N.; Weberpals, J.I.; Clamp, A.; Scambia, G.; et al. Rucaparib maintenance treatment for recurrent ovarian carcinoma after response to platinum therapy (ARIEL3): A randomised; double-blind; placebo-controlled; phase 3 trial. Lancet 2017, 390, 1949–1961, Erratum in Lancet. 2017, 390, 1948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sokolenko, A.P.; Gorodnova, T.V.; Bizin, I.V.; Kuligina, E.S.; Kotiv, K.B.; Romanko, A.A.; Ermachenkova, T.I.; Ivantsov, A.O.; Preobrazhenskaya, E.V.; Sokolova, T.N.; et al. Molecular predictors of the outcome of paclitaxel plus carboplatin neoadjuvant therapy in high-grade serous ovarian cancer patients. Cancer Chemother. Pharmacol. 2021, 88, 439–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lotan, T.L.; Kaur, H.B.; Salles, D.C.; Murali, S.; Schaeffer, E.M.; Lanchbury, J.S.; Isaacs, W.B.; Brown, R.; Richardson, A.L.; Cussenot, O.; et al. Homologous recombination deficiency (HRD) score in germline BRCA2- versus ATM-altered prostate cancer. Mod. Pathol. 2021, 34, 1185–1193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, D.; Wang, A.; Li, Y.; Cai, X.; Zhao, J.; Zhang, T.; Zhao, Y.; Dong, Y.; Zhou, F.; Li, Y.; et al. Establishing the homologous recombination score threshold in metastatic prostate cancer patients to predict the efficacy of PARP inhibitors. J. Natl. Cancer Cent. 2024, 4, 280–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, S.; Zhao, J.; Nie, L.; Yin, W.; Zhang, Y.; Zhao, F.; Ni, Y.; Zhang, X.; Wang, Z.; Dai, J.; et al. Homologous recombination deficiency (HRD) score in aggressive prostatic adenocarcinoma with or without intraductal carcinoma of the prostate (IDC-P). BMC Med. 2022, 20, 237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sokol, E.S.; Pavlick, D.; Khiabanian, H.; Frampton, G.M.; Ross, J.S.; Gregg, J.P.; Lara, P.N.; Oesterreich, S.; Agarwal, N.; Necchi, A.; et al. Pan-Cancer Analysis of BRCA1 and BRCA2 Genomic Alterations and Their Association With Genomic Instability as Measured by Genome-Wide Loss of Heterozygosity. JCO Precis. Oncol. 2020, 4, 442–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, B.; Mota, J.M.; Nandakumar, S.; Stopsack, K.H.; Weg, E.; Rathkopf, D.; Morris, M.J.; Scher, H.I.; Kantoff, P.W.; Gopalan, A.; et al. Pan-cancer Analysis of CDK12 Alterations Identifies a Subset of Prostate Cancers with Distinct Genomic and Clinical Characteristics. Eur. Urol. 2020, 78, 671–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.M.; Cieślik, M.; Lonigro, R.J.; Vats, P.; Reimers, M.A.; Cao, X.; Ning, Y.; Wang, L.; Kunju, L.P.; de Sarkar, N.; et al. Inactivation of CDK12 Delineates a Distinct Immunogenic Class of Advanced Prostate Cancer. Cell 2018, 173, 1770–1782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lukashchuk, N.; Barnicle, A.; Adelman, C.A.; Armenia, J.; Kang, J.; Barrett, J.C.; Harrington, E.A. Impact of DNA damage repair alterations on prostate cancer progression and metastasis. Front. Oncol. 2023, 13, 1162644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shui, I.M.; Burcu, M.; Shao, C.; Chen, C.; Liao, C.Y.; Jiang, S.; Cristescu, R.; Parikh, R.B. Real-world prevalence of homologous recombination repair mutations in advanced prostate cancer: An analysis of two clinico-genomic databases. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis. 2024, 27, 728–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ni Raghallaigh, H.; Eeles, R. Genetic predisposition to prostate cancer: An update. Fam. Cancer 2022, 21, 101–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kote-Jarai, Z.; Jugurnauth, S.; Mulholland, S.; Leongamornlert, D.A.; Guy, M.; Edwards, S.; Tymrakiewitcz, M.; O’Brien, L.; Hall, A.; Wilkinson, R.; et al. A recurrent truncating germline mutation in the BRIP1/FANCJ gene and susceptibility to prostate cancer. Br. J. Cancer 2009, 100, 426–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stempa, K.; Wokołorczyk, D.; Kluźniak, W.; Rogoża-Janiszewska, E.; Malińska, K.; Rudnicka, H.; Huzarski, T.; Gronwald, J.; Gliniewicz, K.; Dębniak, T.; et al. Do BARD1 Mutations Confer an Elevated Risk of Prostate Cancer? Cancers 2021, 13, 5464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ledet, E.M.; Antonarakis, E.S.; Isaacs, W.B.; Lotan, T.L.; Pritchard, C.; Sartor, A.O. Germline BLM mutations and metastatic prostate cancer. Prostate 2020, 80, 235–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otahalova, B.; Volkova, Z.; Soukupova, J.; Kleiblova, P.; Janatova, M.; Vocka, M.; Macurek, L.; Kleibl, Z. Importance of Germline and Somatic Alterations in Human MRE11, RAD50, and NBN Genes Coding for MRN Complex. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 5612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olmos, D.; Lorente, D.; Jambrina, A.; Tello-Velasco, D.; Ovejero-Sánchez, M.; Gonzalez-Ginel, I.; Romero-Laorden, N.; Nunes-Carneiro, D.; Balongo, M.; Gutierrez-Pecharromán, A.M.; et al. BRCA1/2 and homologous recombination repair alterations in high- and low-volume metastatic hormone-sensitive prostate cancer: Prevalence and impact on outcomes. Ann. Oncol. 2025, 36, 1190–1202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Dettman, E.J.; Zhou, W.; Gozman, A.; Jin, F.; Lee, L.C.; Ren, Y.; Zhou, H.; Cristescu, R.; Shao, C. Prevalence of homologous recombination biomarkers in multiple tumor types: An observational study. Future Oncol. 2024, 20, 2357–2370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takamatsu, S.; Brown, J.B.; Yamaguchi, K.; Hamanishi, J.; Yamanoi, K.; Takaya, H.; Kaneyasu, T.; Mori, S.; Mandai, M.; Matsumura, N. Utility of Homologous Recombination Deficiency Biomarkers Across Cancer Types. JCO Precis. Oncol. 2022, 6, e2200085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Sarkar, N.; Dasgupta, S.; Chatterjee, P.; Coleman, I.; Ha, G.; Ang, L.S.; Kohlbrenner, E.A.; Frank, S.B.; Nunez, T.A.; Salipante, S.J.; et al. Genomic attributes of homology-directed DNA repair deficiency in metastatic prostate cancer. JCI Insight 2021, 6, e152789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, A.; Geyer, F.C.; Blecua, P.; Lee, J.Y.; Selenica, P.; Brown, D.N.; Pareja, F.; Lee, S.S.K.; Kumar, R.; Rivera, B.; et al. Homologous recombination DNA repair defects in PALB2-associated breast cancers. npj Breast Cancer 2019, 5, 23, Correction in npj Breast Cancer 2019, 5, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preobrazhenskaya, E.V.; Shleykina, A.U.; Gorustovich, O.A.; Martianov, A.S.; Bizin, I.V.; Anisimova, E.I.; Sokolova, T.N.; Chuinyshena, S.A.; Kuligina, E.S.; Togo, A.V.; et al. Frequency and molecular characteristics of PALB2-associated cancers in Russian patients. Int. J. Cancer 2021, 148, 203–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horak, P.; Weischenfeldt, J.; von Amsberg, G.; Beyer, B.; Schütte, A.; Uhrig, S.; Gieldon, L.; Klink, B.; Feuerbach, L.; Hübschmann, D.; et al. Response to olaparib in a PALB2 germline mutated prostate cancer and genetic events associated with resistance. Cold Spring Harb. Mol. Case Stud. 2019, 5, a003657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciccone, M.A.; Adams, C.L.; Bowen, C.; Thakur, T.; Ricker, C.; Culver, J.O.; Maoz, A.; Melas, M.; Idos, G.E.; Jeyasekharan, A.D.; et al. Inhibition of poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase induces synthetic lethality in BRIP1 deficient ovarian epithelial cells. Gynecol. Oncol. 2020, 159, 869–876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antonarakis, E.S.; Isaacsson Velho, P.; Fu, W.; Wang, H.; Agarwal, N.; Sacristan Santos, V.; Maughan, B.L.; Pili, R.; Adra, N.; Sternberg, C.N.; et al. CDK12-Altered Prostate Cancer: Clinical Features and Therapeutic Outcomes to Standard Systemic Therapies; Poly (ADP-Ribose) Polymerase Inhibitors; and PD-1 Inhibitors. JCO Precis. Oncol. 2020, 4, 370–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mateo, J.; Porta, N.; Bianchini, D.; McGovern, U.; Elliott, T.; Jones, R.; Syndikus, I.; Ralph, C.; Jain, S.; Varughese, M.; et al. Olaparib in patients with metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer with DNA repair gene aberrations (TOPARP-B): A multicentre; open-label; randomised; phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2020, 21, 162–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agarwal, N.; Azad, A.A.; Carles, J.; Fay, A.P.; Matsubara, N.; Heinrich, D.; Szczylik, C.; De Giorgi, U.; Young Joung, J.; Fong, P.C.C.; et al. Talazoparib plus enzalutamide in men with first-line metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer (TALAPRO-2): A randomised; placebo-controlled; phase 3 trial. Lancet 2023, 402, 291–303, Erratum in Lancet 2023, 402, 290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, C.B.; Reimers, M.A.; Perera, C.; Abida, W.; Chou, J.; Feng, F.Y.; Antonarakis, E.S.; McKay, R.R.; Pachynski, R.K.; Zhang, J.; et al. Evaluating Immune Checkpoint Blockade in Metastatic Castration-Resistant Prostate Cancers with Deleterious CDK12 Alterations in the Phase 2 IMPACT Trial. Clin. Cancer Res. 2024, 30, 3200–3210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tien, J.C.; Luo, J.; Chang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Cheng, Y.; Wang, X.; Yang, J.; Mannan, R.; Mahapatra, S.; Shah, P.; et al. CDK12 loss drives prostate cancer progression, transcription-replication conflicts, and synthetic lethality with paralog CDK13. Cell Rep. Med. 2024, 5, 101758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frank, S.; Persse, T.; Coleman, I.; Bankhead, A., 3rd; Li, D.; De-Sarkar, N.; Wilson, D.; Rudoy, D.; Vashisth, M.; Galipeau, P.; et al. Molecular consequences of acute versus chronic CDK12 loss in prostate carcinoma nominates distinct therapeutic strategies. bioRxiv 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Decker, B.; Karyadi, D.M.; Davis, B.W.; Karlins, E.; Tillmans, L.S.; Stanford, J.L.; Thibodeau, S.N.; Ostrander, E.A. Biallelic BRCA2 Mutations Shape the Somatic Mutational Landscape of Aggressive Prostate Tumors. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2016, 98, 818–829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barnett, E.S.; Schultz, N.; Stopsack, K.H.; Lam, E.T.; Arfe, A.; Lee, J.; Zhao, J.L.; Schonhoft, J.D.; Carbone, E.A.; Keegan, N.M.; et al. Analysis of BRCA2 Copy Number Loss and Genomic Instability in Circulating Tumor Cells from Patients with Metastatic Castration-resistant Prostate Cancer. Eur. Urol. 2023, 83, 112–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van der Auwera, G.A.; Carneiro, M.O.; Hartl, C.; Poplin, R.; Del Angel, G.; Levy-Moonshine, A.; Jordan, T.; Shakir, K.; Roazen, D.; Thibault, J.; et al. From FastQ data to high confidence variant calls: The Genome Analysis Toolkit best practices pipeline. Curr. Protoc. Bioinform. 2013, 43, 11-10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timms, K.M.; Abkevich, V.; Hughes, E.; Neff, C.; Reid, J.; Morris, B.; Kalva, S.; Potter, J.; Tran, T.V.; Chen, J.; et al. Association of BRCA1/2 defects with genomic scores predictive of DNA damage repair deficiency among breast cancer subtypes. Breast Cancer Res. 2014, 16, 475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Characteristic | PC Cases Tested for HRR Mutations (n = 1131) | PC Cases Tested for HRD Score (n = 680) |

|---|---|---|

| Mean age at diagnosis; years (age range) | 64.6 (40–87) | 64.9 (41–85) |

| Cases with age at diagnosis ≤ 55 years | 146 (12.9%) | 79 (11.6%) |

| Tumor size (T) | ||

| T1 | 169 (14.9%) | 157 (23.1%) |

| T2 | 205 (18.1%) | 105 (15.4%) |

| T3 | 305 (27.0%) | 141 (20.7%) |

| T4 | 182 (16.1%) | 95 (14.0%) |

| Nd * | 270 (23.9%) | 182 (26.8%) |

| Lymph node status (N) | ||

| N0 | 468 (41.4%) | 305 (44.9%) |

| N1 | 362 (32.0%) | 180 (26.5%) |

| Nd | 301 (26.6%) | 195 (28.7%) |

| Distant metastases (M) | ||

| M0 | 438 (38.7%) | 275 (40.4%) |

| M1 | 403 (35.6%) | 206 (30.3%) |

| Nd | 290 (25.6%) | 199 (29.3%) |

| Stage | ||

| 1 | 165 (14.6%) | 152 (22.4%) |

| 2 | 117 (10.3%) | 61 (9.0%) |

| 3 | 75 (6.6%) | 28 (4.1%) |

| 4 | 477 (42.2%) | 238 (35.0%) |

| Nd | 297 (26.3%) | 201 (29.6%) |

| Gleason score | ||

| <8 | 566 (50.0%) | 397 (58.4%) |

| ≥8 | 397 (35.1%) | 204 (30.0%) |

| Nd | 168 (14.9%) | 79 (11.6%) |

| HRR Mutations | Significance, p-Value | HRD Score ≥ 42 | Significance, p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age at diagnosis | ||||

| ≤55 | 33/146 (22.6%) | 0.251 | 7/79 (8.9%) | 0.666 |

| >55 | 183/984 (18.6%) | 45/601 (7.5%) | ||

| Tumor size (T) | ||||

| T1 | 21/169 (12.4%) | 0.022 | 1/157 (0.6%) | <0.0001 |

| T2 | 35/205 (17.1%) | 8/105 (7.6%) | ||

| T3 | 78/304 (25.7%) | 16/141 (11.3%) | ||

| T4 | 34/182 (18.7%) | 17/95 (17.9%) | ||

| Nodal involvement (N) | ||||

| N0 | 74/467 (15.8%) | 0.004 | 8/305 (2.6%) | <0.0001 |

| N1 | 86/362 (23.8%) | 32/180 (17.8%) | ||

| Distant metastases (M) | ||||

| M0 | 72/437 (16.5%) | 0.020 | 12/275 (4.4%) | 0.0001 |

| M1 | 92/403 (22.8%) | 30/206 (14.6%) | ||

| Tumor stage | ||||

| 1 | 20/165 (12.1%) | 0.0002 | 1/152 (0.7%) | <0.0001 |

| 2 | 13/117 (11.1%) | 2/61 (3.3%) | ||

| 3 | 18/74 (24.3%) | 1/28 (3.6%) | ||

| 4 | 111/477 (23.3%) | 38/238 (16.0%) | ||

| Family history of cancer | ||||

| Negative or no data | 203/1077 (18.8%) | 0.305 | 48/664 (7.2%) | 0.028 |

| Positive | 13/53 (24.5%) | 4/16 (25.0%) | ||

| Gleason grade | ||||

| <8 | 84/566 (14.8%) | 0.002 | 11/397 (2.8%) | <0.0001 |

| ≥8 | 90/397 (22.7%) | 28/204 (13.7%) | ||

| TP53 somatic mutation | ||||

| WT | 163/823 (19.8%) | 0.090 | 31/558 (5.6%) | <0.0001 |

| MUT | 28/193 (14.5%) | 21/121 (17.4%) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Iyevleva, A.G.; Aleksakhina, S.N.; Sokolenko, A.P.; Otradnova, E.A.; Nikitina, A.S.; Kashko, K.A.; Syomina, M.V.; Shestakova, A.D.; Kuligina, E.S.; Morozova, N.S.; et al. Complex Relationships Between Homologous Recombination Deficiency (HRD) Score and Mutational Status of Homologous Recombination Repair (HRR) Genes in Prostate Carcinomas. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 11851. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262411851

Iyevleva AG, Aleksakhina SN, Sokolenko AP, Otradnova EA, Nikitina AS, Kashko KA, Syomina MV, Shestakova AD, Kuligina ES, Morozova NS, et al. Complex Relationships Between Homologous Recombination Deficiency (HRD) Score and Mutational Status of Homologous Recombination Repair (HRR) Genes in Prostate Carcinomas. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2025; 26(24):11851. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262411851

Chicago/Turabian StyleIyevleva, Aglaya G., Svetlana N. Aleksakhina, Anna P. Sokolenko, Ekaterina A. Otradnova, Alisa S. Nikitina, Kira A. Kashko, Maria V. Syomina, Anna D. Shestakova, Ekaterina S. Kuligina, Natalia S. Morozova, and et al. 2025. "Complex Relationships Between Homologous Recombination Deficiency (HRD) Score and Mutational Status of Homologous Recombination Repair (HRR) Genes in Prostate Carcinomas" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 26, no. 24: 11851. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262411851

APA StyleIyevleva, A. G., Aleksakhina, S. N., Sokolenko, A. P., Otradnova, E. A., Nikitina, A. S., Kashko, K. A., Syomina, M. V., Shestakova, A. D., Kuligina, E. S., Morozova, N. S., Popov, S. V., Vyazovcev, P. V., Luchkova, T. Y., Peremyshlenko, A. S., Topuzov, T. M., Gudkova, O. M., Orlova, R. V., Levushkin, A. V., Moiseev, D. O., ... Imyanitov, E. N. (2025). Complex Relationships Between Homologous Recombination Deficiency (HRD) Score and Mutational Status of Homologous Recombination Repair (HRR) Genes in Prostate Carcinomas. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 26(24), 11851. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262411851