Integrated Omics Analysis Revealed the Differential Metabolism of Pigments in Three Varieties of Gastrodia elata Bl

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

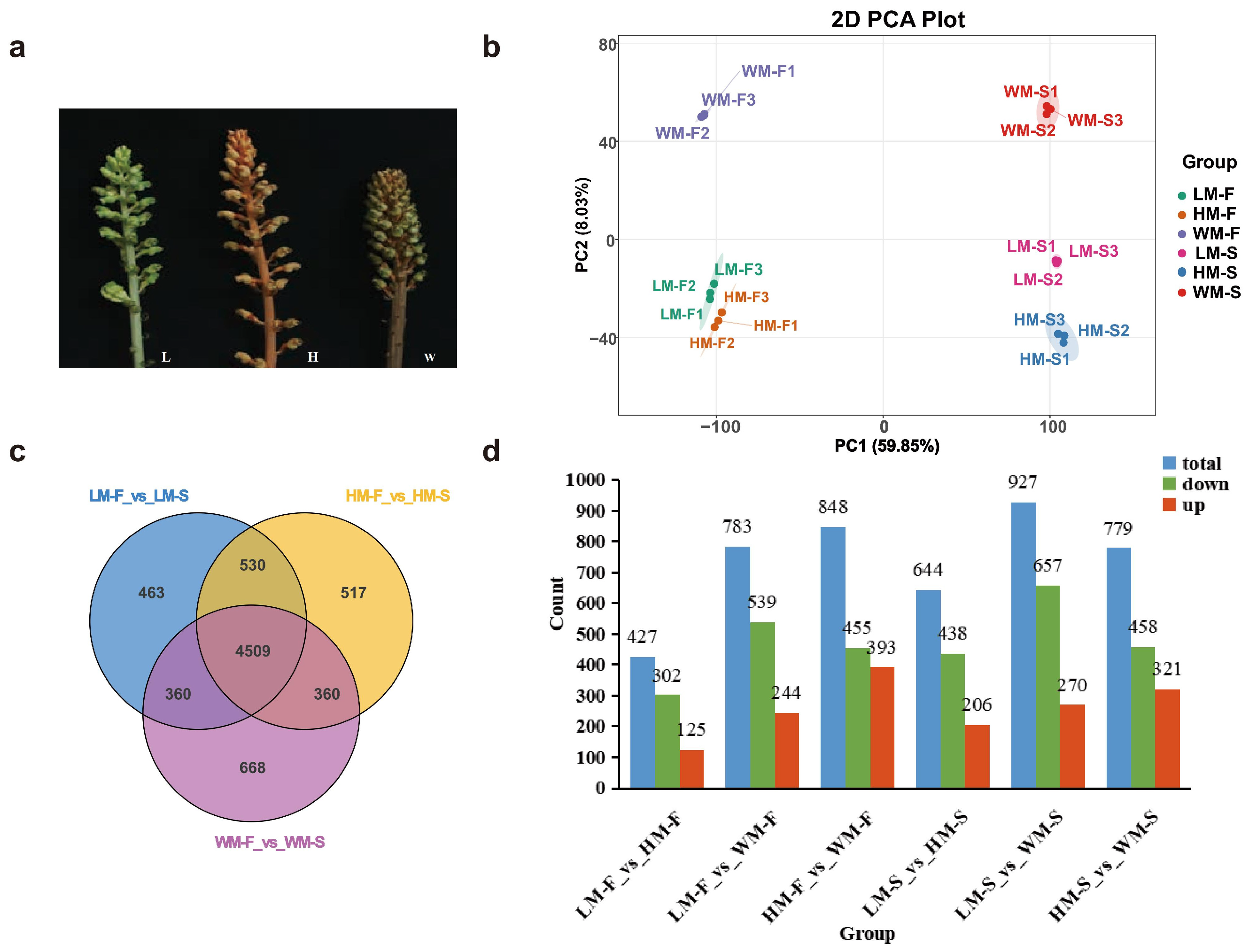

2.1. Transcriptome Sequencing and Differential Gene Expression Analysis in Different Varieties of G. elata

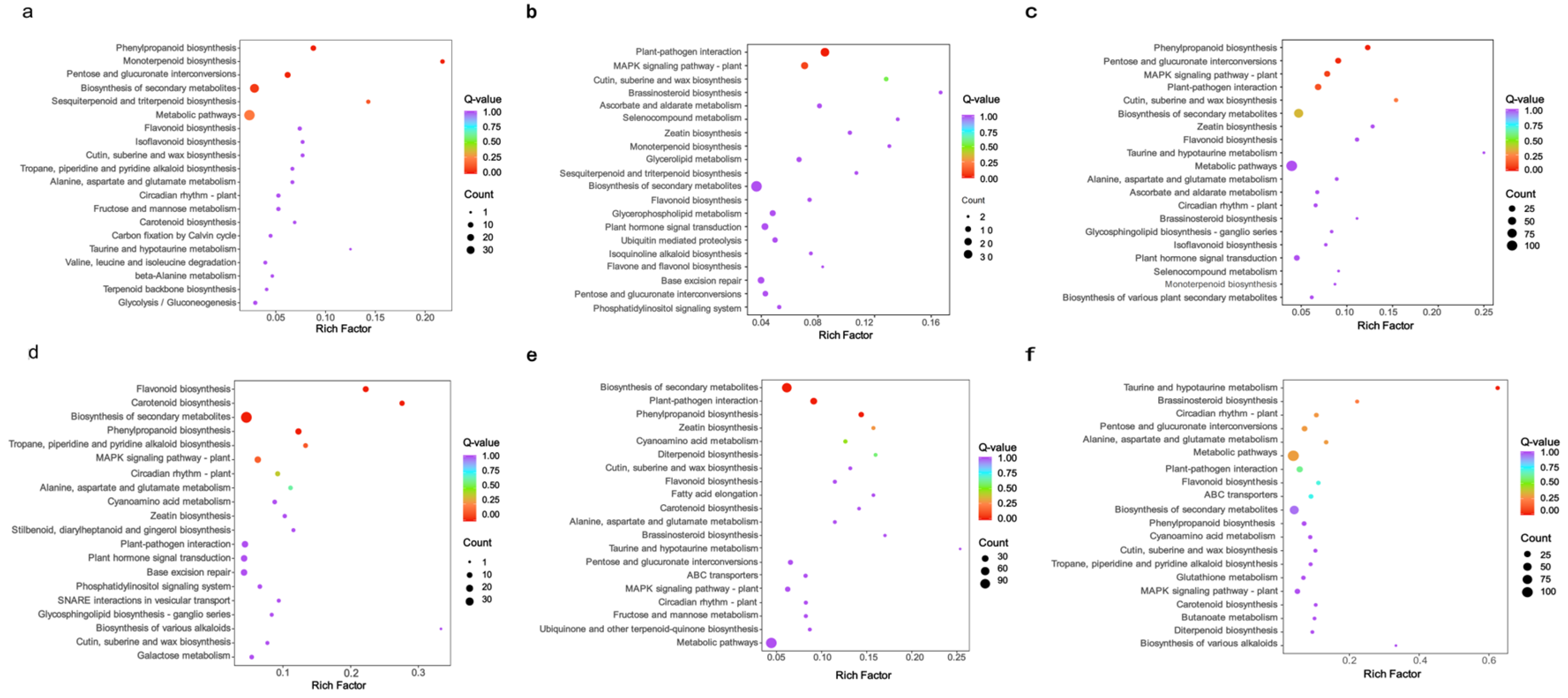

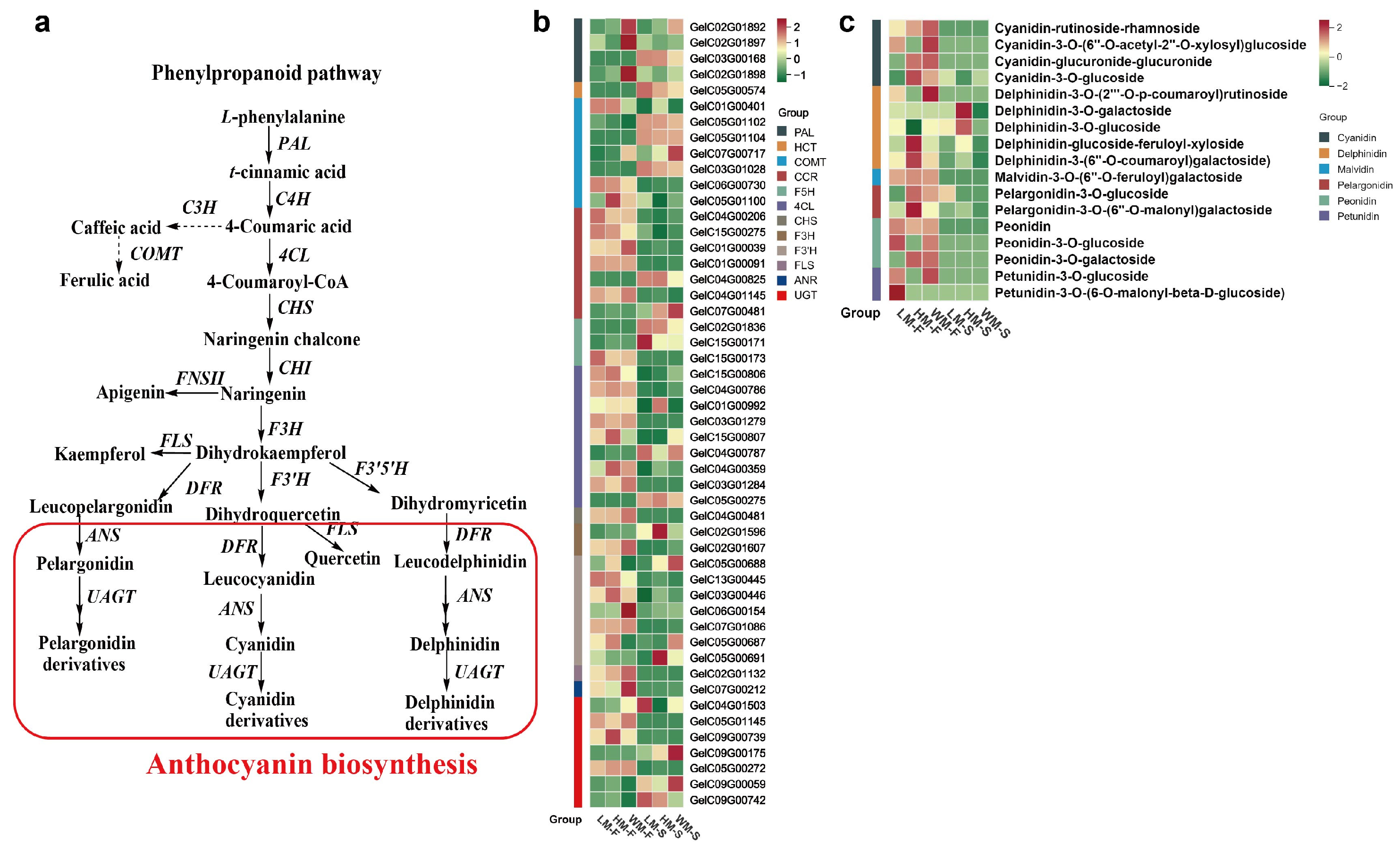

2.2. The Anthocyanin Biosynthesis Pathway in G. elata Varieties

2.3. Metabolomic Analysis of Anthocyanins in G. elata Varieties

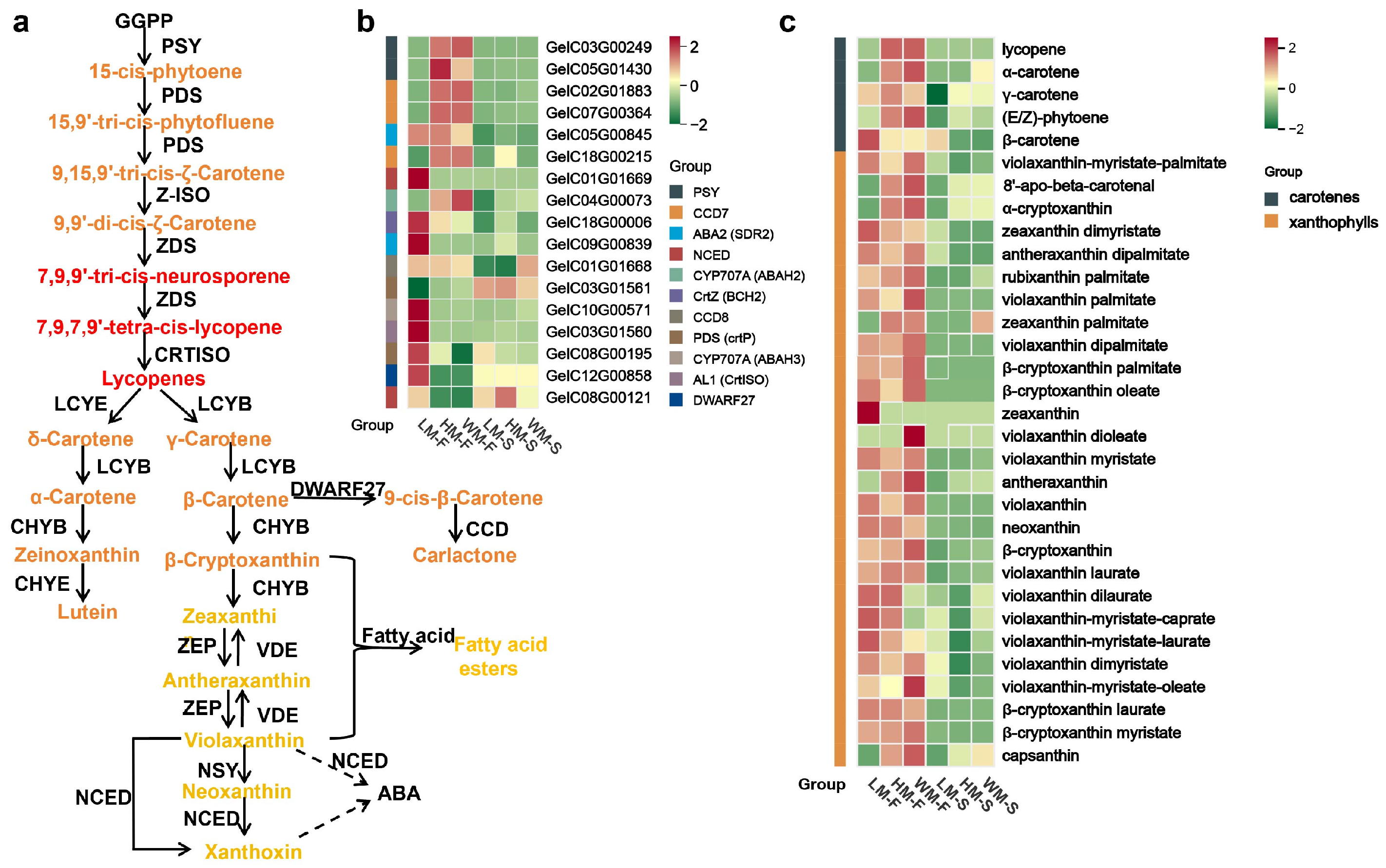

2.4. The Carotenoid Biosynthesis Pathway and Accumulation in G. elata Varieties

2.5. Carotenoids That Contributed to the Pigmentation of G. elata Varieties

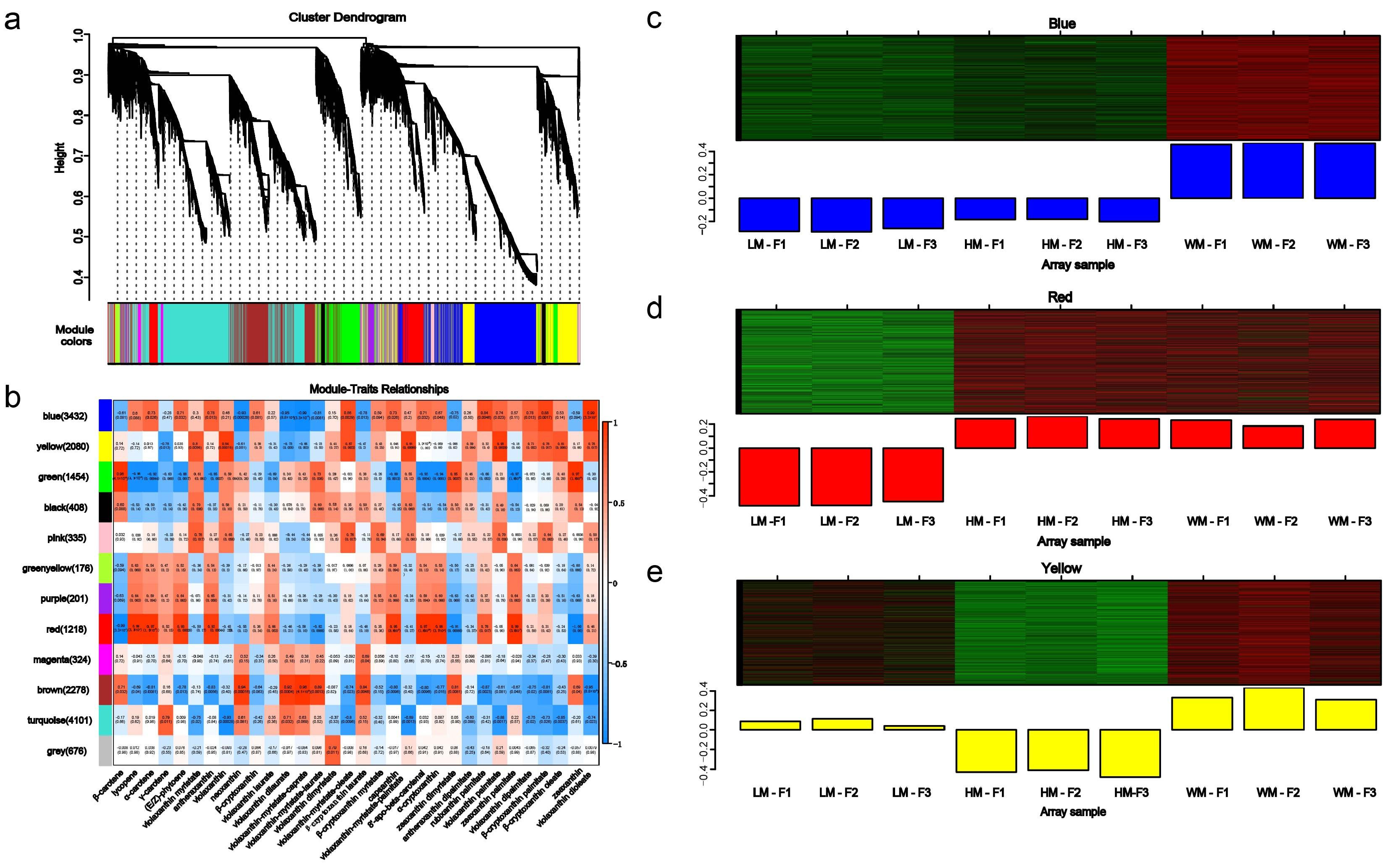

2.6. Weighed Gene Co-Expression Network Analysis (WGCNA)

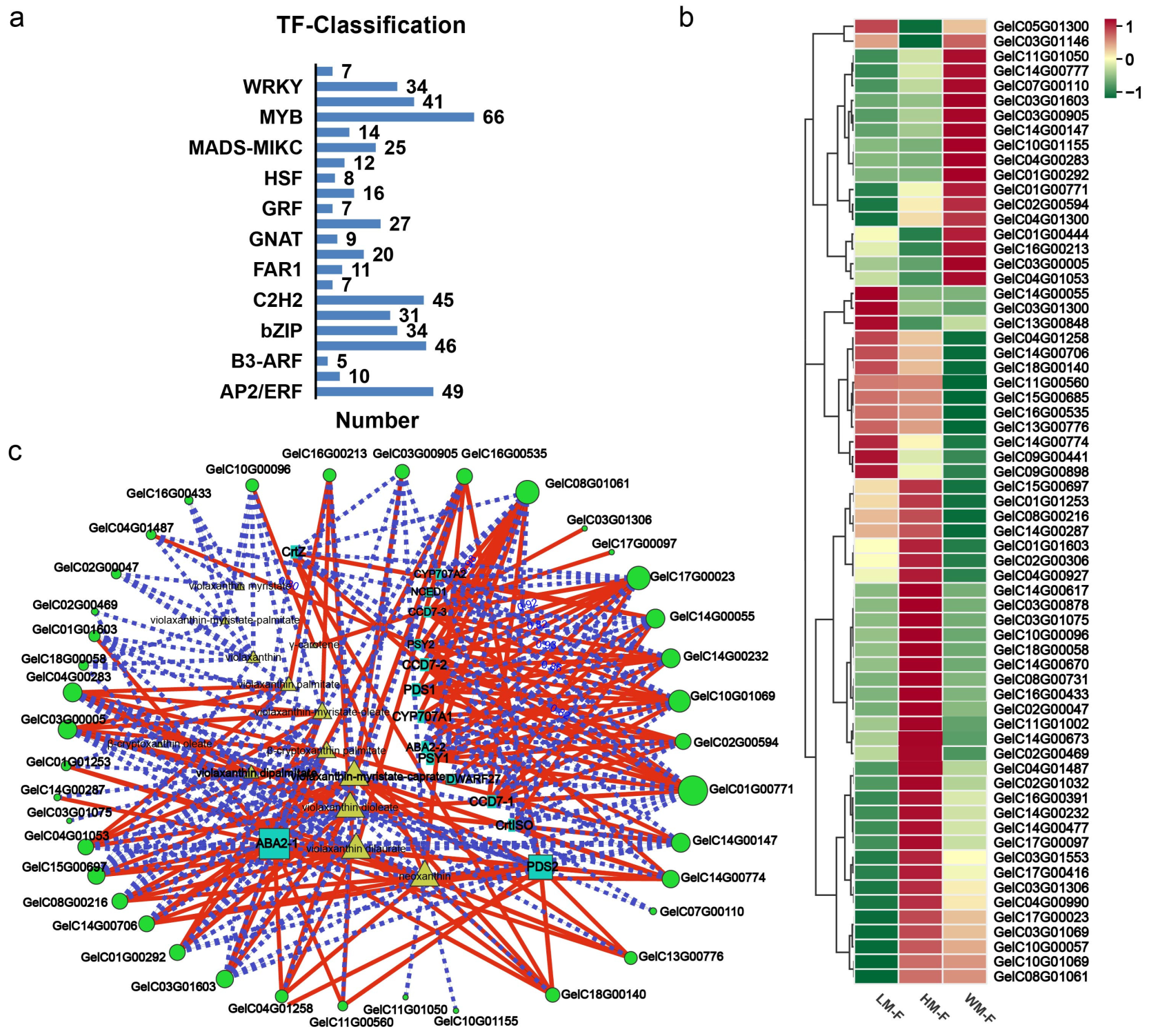

2.7. MYB Transcription Factors Related to Carotenoids’ Synthesis in G. elata

3. Discussion

3.1. Pigment Composition and Accumulation Govern Phenotypic Color Diversity

3.2. The Regulation of Pigments’ Biosynthetic Pathway

3.3. TFs Play a Critical Role in Orchestrating Color in Different Varieties of G. elata

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Plant Materials and Sampling

4.2. Metabolites Analysis

4.2.1. Targeted Metabolomics Analysis for Anthocyanins

4.2.2. The Metabolic Analysis of Carotenoids

4.3. RNA Extraction and Library Sequencing

4.4. Transcriptome Data Analysis

4.5. Integrative Analysis of Transcriptomic and Metabolomic Profiles

4.6. Data Processing and Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Rodriguez-Concepcion, M.; Avalos, J.; Bonet, M.L.; Boronat, A.; Gomez-Gomez, L.; Hornero-Mendez, D.; Limon, M.C.; Meléndez-Martínez, A.J.; Olmedilla-Alonso, B.; Palou, A.; et al. A global perspective on carotenoids: Metabolism, biotechnology, and benefits for nutrition and health. Prog. Lipid Res. 2018, 70, 62–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tanaka, Y.; Sasaki, N.; Ohmiya, A. Biosynthesis of plant pigments: Anthocyanins, Betalains and Carotenoids. Plant J. 2008, 54, 733–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yadav, S.; Rahim, M.S.; Devi, A.; Sharma, R.K. Revolutionizing Speciality Teas: Multi-omics Prospective to Breed Anthocyanin-rich Tea. Food Res. Int. 2025, 209, 116312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeng, D.; Qin, R.; Tang, L.; Jing, C.; Wen, J.; He, P.; Zhang, J. Enrichment of Rice Endosperm with Anthocyanins by Endosperm-specific Expression of Rice Endogenous Genes. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2024, 219, 109428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Q.; Yu, S.; Zeng, D.; Liu, H.; Wang, H.; Yang, Z.; Xie, X.; Shen, R.; Tan, J.; Li, H.; et al. Development of “Purple Endosperm Rice” by Engineering Anthocyanin Biosynthesis in the Endosperm with a High-Efficiency Transgene Stacking System. Mol. Plant 2017, 10, 918–929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, C.; Deng, L.; Du, M.; Zhao, J.; Chen, Q.; Huang, T.; Jiang, H.; Li, C.-B.; Li, C. A Transcriptional Network Promotes Anthocyanin Biosynthesis in Tomato Flesh. Mol. Plant 2020, 13, 42–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mackon, E.; Jeazet Dongho Epse Mackon, G.C.; Guo, Y.; Ma, Y.; Yao, Y.; Liu, P. Development and Application of CRISPR/Cas9 to Improve Anthocyanin Pigmentation in Plants: Opportunities and Perspectives. Plant Sci. 2023, 333, 111746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, X.; Li, J.; Chen, T.; Li, Y.; Guo, S. Global Metabolic Profile and Multiple Phytometabolites in the Different Varieties of Gastrodia elata Blume. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14, 1249456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, M.-Q.; Lai, F.-F.; Chen, J.-Z.; Li, X.-H.; Chen, Y.-J.; He, Y. Traditional Uses, Phytochemistry, Pharmacology, Applications, and Quality Control of Gastrodia elata Blume: A Comprehensive Review. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2024, 319, 117128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rai, A.; Saito, K.; Yamazaki, M. Integrated Omics Analysis of Specialized Metabolism in Medicinal Plants. Plant J. 2017, 90, 764–787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schweiggert, R.M.; Vargas, E.; Conrad, J.; Hempel, J.; Gras, C.C.; Ziegler, J.U.; Mayer, A.; Jiménez, V.; Esquivel, P.; Carle, R. Carotenoids, Carotenoid Esters, and Anthocyanins of Yellow-, Orange-, and Red-Peeled Cashew Apples (Anacardium occidentale L.). Food Chem. 2016, 200, 274–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, L.; Zhang, Y.; Cui, G.; Duan, Q.; Jia, W.; Xu, F.; Du, W.; Wang, X.; Li, X.; Chen, F.; et al. Transcriptome Analysis of Key Genes Involved in Color Variation between Blue and White Flowers of Iris bulleyana. BioMed Res. Int. 2023, 2023, 7407772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xia, Y.; Chen, W.; Xiang, W.; Wang, D.; Xue, B.; Liu, X.; Xing, L.; Wu, D.; Wang, S.; Guo, Q.; et al. Integrated Metabolic Profiling and Transcriptome Analysis of Pigment Accumulation in Lonicera japonica Flower Petals During Colour-transition. BMC Plant Biol. 2021, 21, 98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, N.; Xing, S.; Sun, G.; Shang, J.; Yao, J.-L.; Li, N.; Zhou, D.; Wang, Y.; Lu, Y.; Bi, J.; et al. Multi-omics Analyses Unveil Dual Genetic Loci Governing Four Distinct Watermelon Flesh Color Phenotypes. Mol. Hortic. 2025, 5, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, B.; Liu, X.; Liu, Y.; Luo, L.; Pan, H.; Zhang, Q.; Yu, C. Targeted Metabolite and Molecular Profiling of Carotenoids in rose petals: A Step Forward Towards Functional Food Applications. Food Chem. 2024, 464, 141675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.; Wang, J.; Muhammad, T.; Yang, T.; Li, N.; Yang, H.; Yu, Q.; Wang, B. Integrative Analysis of Metabolome and Transcriptome of Carotenoid Biosynthesis Reveals the Mechanism of Fruit Color Change in Tomato (Solanum lycopersicum). Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 6493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Song, Z.; Zhan, X.; Li, X.; Ye, L.; Lin, M.; Wang, R.; Huang, H.; Guo, J.; Sun, L.; et al. Chromosome-level Genome Assembly Assisting for Dissecting Mechanism of Anthocyanin Regulation in Kiwifruit (Actinidia arguta). Mol. Hortic. 2025, 5, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, W.; Zhang, W.; Liu, D.; Yin, M.; Wang, X.; Wang, S.; Shen, S.; Liu, S.; Huang, Y.; Li, X.; et al. Evolution-guided Multiomics Provide Insights into the Strengthening of Bioactive Flavone Biosynthesis in Medicinal Pummelo. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2023, 21, 1577–1589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ni, J.; Liao, Y.; Zhang, M.; Pan, C.; Yang, Q.; Bai, S.; Teng, Y. Blue Light Simultaneously Induces Peel Anthocyanin Biosynthesis and Flesh Carotenoid/Sucrose Biosynthesis in Mango Fruit. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2022, 70, 16021–16035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz, A.B.; Bianchetti, R.E.; Alves, F.R.R.; Purgatto, E.; Peres, L.E.P.; Rossi, M.; Freschi, L. Light, Ethylene and Auxin Signaling Interaction Regulates Carotenoid Biosynthesis During Tomato Fruit Ripening. Front. Plant Sci. 2018, 9, 1370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gang, M.; Lancui, Z.; Rin, K.; Hayato, I.; Kan, M.; Masashi, Y.; Nami, K.; Masaki, Y.; Hikaru, M.; Masaya, K. Auxin Induced Carotenoid Accumulation in GA and PDJ-treated Citrus Fruit after Harvest. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2021, 181, 111676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, T.; Yuan, H.; Cao, H.; Yazdani, M.; Tadmor, Y.; Li, L. Carotenoid Metabolism in Plants: The Role of Plastids. Mol. Plant 2018, 11, 58–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lv, J.; Zhang, R.; Mo, Y.; Zhou, H.; Li, M.; Wu, R.; Cheng, H.; Zhang, M.; Wang, H.; Hua, W.; et al. Integrative Metabolome and Transcriptome Analyses Provide Insights into Carotenoid Variation in Different-Colored Peppers. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 16563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, F.; Wan, R.; Shi, Z.; Ma, W.; Wang, H.; Chen, Y.; Bo, J.; Li, Y.; An, W.; Qin, K.; et al. Transcriptomics and Metabolomics Reveal the Critical Genes of Carotenoid Biosynthesis and Color Formation of Goji (Lycium barbarum L.) Fruit Ripening. Plants 2023, 12, 2791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, Y.; Zhu, C.; Hu, Y.; Yan, S.; Luo, Z.; Zou, Y.; Wu, W.; Zeng, J. Integrated Hormone and Transcriptome Profiles Provide Insight into the Pericarp Differential Development Mechanism between Mandarin ‘Shatangju’ and ‘Chunhongtangju’. Front. Plant Sci. 2024, 15, 1461316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Chen, B.; Zhang, J.; Lan, S.; Wu, S.; Xie, W. Transcriptome and Metabolome Analysis Revealed the Changes of Geniposide and Crocin Content in Gardenia jasminoides fruit. Mol. Biol. Rep. 2023, 50, 6851–6861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perrin, F.; Hartmann, L.; Dubois-Laurent, C.; Welsch, R.; Huet, S.; Hamama, L.; Briard, M.; Peltier, D.; Gagné, S.; Geoffriau, E. Carotenoid Gene Expression Explains the Difference of Carotenoid Accumulation in Carrot Root Tissues. Planta 2017, 245, 737–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, L.J.; Agustini, M.A.; Anderson, J.V.; Vieira, E.A.; de Souza, C.R.; Chen, S.; Schaal, B.A.; Silva, J.P. Natural Variation in Expression of Genes Associated with Carotenoid Biosynthesis and Accumulation in Cassava (Manihot esculenta Crantz) storage root. BMC Plant Biol. 2016, 16, 133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Carvalho, R.R.B.; Marmolejo Cortes, D.F.; Bandeira E Sousa, M.; de Oliveira, L.A.; de Oliveira, E.J. Image-based Phenotyping of Cassava Roots for Diversity Studies and Carotenoids Prediction. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, 0263326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Zhou, Y.; Zhang, M.; Li, X.; Liu, T.; Liu, Y.; Xie, H.; Wang, K.; Li, P.; Xu, Z.; et al. Resolving Floral Development Dynamics Using Genome and Single-cell Temporal Transcriptome of Dendrobium devonianum. Plant Biotech. J. 2025, 23, 2997–3011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ampomah-Dwamena, C.; Thrimawithana, A.H.; Dejnoprat, S.; Lewis, D.; Espley, R.V.; Allan, A.C. A Kiwifruit (Actinidia deliciosa) R2R3-MYB Transcription Factor Modulates Chlorophyll and Carotenoid Accumulation. New Phytol. 2018, 221, 309–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, S.; Zhang, Y.; Zhu, K.; Yang, W.; Ye, J.; Chai, L.; Xu, Q.; Deng, X. The Citrus Transcription Factor CsMADS6 Modulates Carotenoid Metabolism by Directly Regulating Carotenogenic Genes. Plant Physiol. 2018, 176, 2657–2676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhat, Z.Y.; Mohiuddin, T.; Kumar, A.; López-Jiménez, A.J.; Ashraf, N. Crocus Transcription Factors CstMYB1 and CstMYB1R2 Modulate Apocarotenoid Metabolism by Regulating Carotenogenic Genes. Plant Mol. Biol. 2021, 107, 49–62, Erratum in Plant Mol. Biol. 2021, 107, 207. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11103-021-01192-2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, H.; Fu, X.; Shao, J.; Tang, Y.; Yu, M.; Li, L.; Huang, L.; Tang, K. Transcriptional Regulatory Network of High-value Active Ingredients in Medicinal Plants. Trends Plant Sci. 2023, 28, 429–446, Erratum in Trends Plant Sci. 2023, 28, 856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Fang, Y.; Jiang, F.; Liao, Y.; Pan, C.; Li, J.; Wu, J.; Yang, Q.; Qin, R.; Bai, S.; et al. CRY1–GAIP1 Complex Mediates Blue Light to Hinder the Repression of PIF5 on AGL5 to Promote Carotenoid Biosynthesis in Mango Fruit. Plant Biotech. J. 2025, 23, 2769–2789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bi, M.; Xu, L.; Wang, J.; Liu, X.; Yang, P.; Bai, J.; Luo, Y.; Yang, C.; Yang, Y.; Ming, J. Three Transcription Factors form an Activation–inhibition Module to Regulate Anthocyanin Accumulation in Asiatic hybrid lilies. Plant Physiol. 2025, 198, kiaf203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fraga, C.G.; Clowers, B.H.; Moore, R.J.; Zink, E.M. Signature-Discovery Approach for Sample Matching of a Nerve-Agent Precursor Using Liquid Chromatography−Mass Spectrometry, XCMS, and Chemometrics. Anal. Chem. 2010, 82, 4165–4173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Li, X.; Zhu, H.; Zhang, B.; Liu, D. Integrated Omics Analysis Revealed the Differential Metabolism of Pigments in Three Varieties of Gastrodia elata Bl. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 11839. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262411839

Li X, Zhu H, Zhang B, Liu D. Integrated Omics Analysis Revealed the Differential Metabolism of Pigments in Three Varieties of Gastrodia elata Bl. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2025; 26(24):11839. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262411839

Chicago/Turabian StyleLi, Xiaohua, Huaijing Zhu, Bingbing Zhang, and Dahui Liu. 2025. "Integrated Omics Analysis Revealed the Differential Metabolism of Pigments in Three Varieties of Gastrodia elata Bl" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 26, no. 24: 11839. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262411839

APA StyleLi, X., Zhu, H., Zhang, B., & Liu, D. (2025). Integrated Omics Analysis Revealed the Differential Metabolism of Pigments in Three Varieties of Gastrodia elata Bl. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 26(24), 11839. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262411839