Genetic Determinants of Progressive Pulmonary Fibrosis: A Comprehensive Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Genetic Architecture of Progressive Pulmonary Fibrosis

2.1. MUC5B Promoter Variant

2.2. Additional GWAS-Identified Loci

2.3. Telomere Maintenance Genes

2.4. Cell Adhesion and Signaling

2.5. Mitotic Spindle Assembly

2.6. mTOR Signaling

2.7. Rare Genetic Variants

2.8. Telomere-Related Genes

2.9. Surfactant Protein Genes

2.10. Hermansky–Pudlak Syndrome

3. Epigenetic Regulation

3.1. Epigenetic Modifications

3.2. DNA Methylation

3.3. Histone Modifications

3.4. Non-Coding RNA Regulation

4. Gene–Environment Interactions

4.1. Environmental Risk Factors

4.2. Occupational and Environmental Exposures

4.3. Implications for Disease Penetrance and Progression

5. Clinical Implications of Genetic Testing

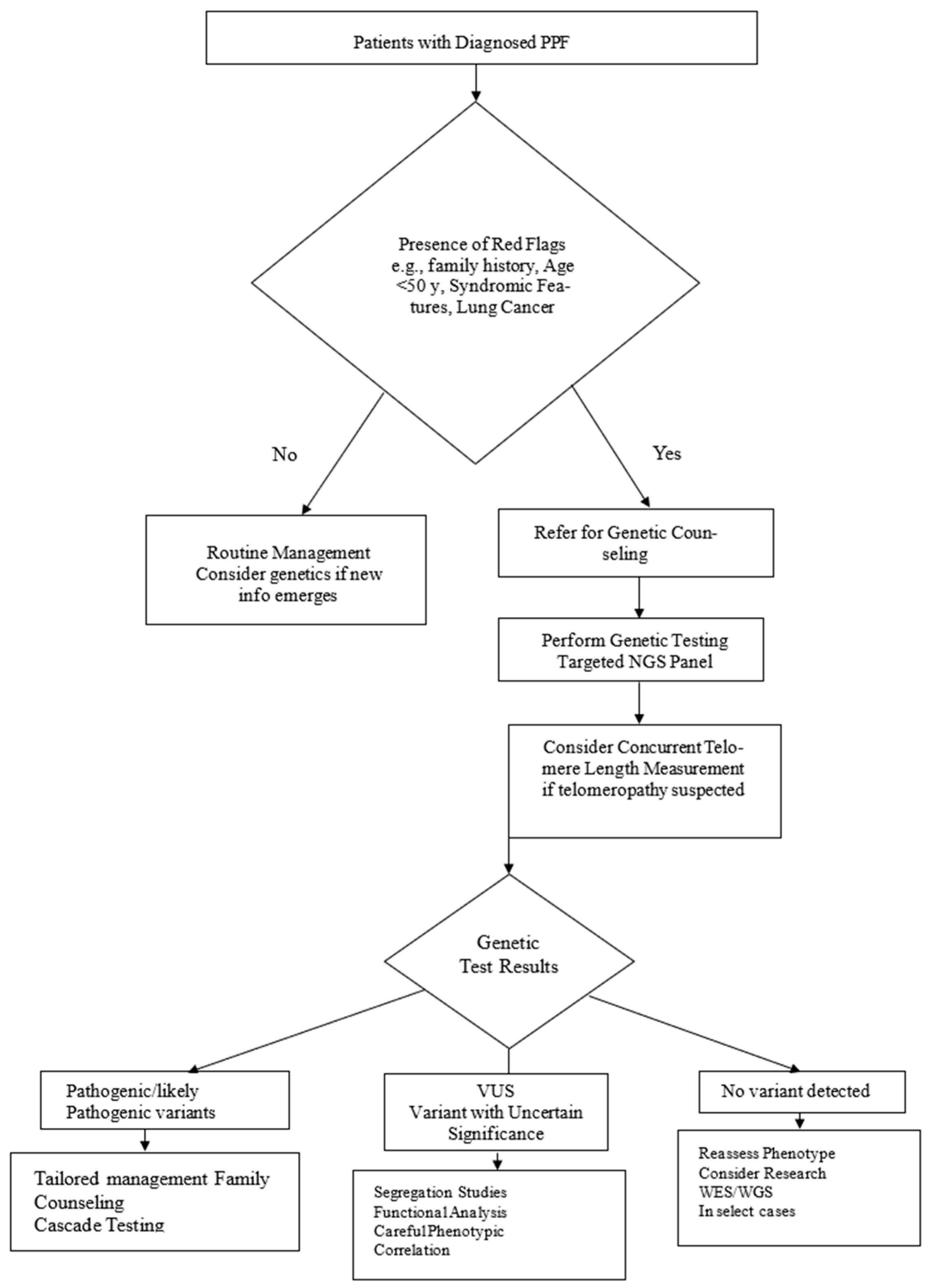

5.1. Indications and Testing Strategies

5.2. Genetic Testing Methodologies

- Step 1: Initial clinical assessment

- -

- Confirm diagnosis of PPF based on clinical, radiological (HRCT), and, when needed, histopathological criteria.

- Step 2: Red flags for genetic evaluation

- -

- Family history of interstitial lung disease in ≥1 first-degree relative.

- -

- Early-onset PPF (<50 years)

- -

- Syndromic features (premature hair greying, bone marrow failure, liver dysfunction, immunodeficiency).

- -

- Coexisting lung adenocarcinoma, especially with familial cases or in younger patients.

- Step 3: Referral for genetic counselling

- -

- Discuss goals, implications, and possible results of genetic testing (e.g., pathogenic variant, variant of uncertain significance (VUS), negative result).

- -

- Obtain detailed family history and construct a pedigree.

- Step 4. Genetic testing strategy

- -

- Perform an NGS panel covering telomere-maintenance genes (TERT, TERC, RTEL1, PARN), surfactant genes (SFTPC, SFTPA1, SFTPA2, ABCA3), and syndromic genes (HPS1, HPS3) when indicated.

- -

- Measure telomere length (Flow-FISH) in individuals with suspected telomeropathies.

- Step 5. Result interpretation and management decisions

- -

- Pathogenic variants → tailored clinical management and family counselling.

- -

- VUS → segregation studies or additional phenotyping as appropriate.

- -

- No variant detected → reassess phenotype and exposures; consider WES/WGS in select cases.

5.3. Interpretation and Clinical Management

5.4. Prognostic Information

5.5. Surveillance Recommendations

5.6. Treatment Considerations

5.7. Treatment Consequences and Lung Transplantation Planning

5.8. Telomere-Related Gene Variants (TERT, TERC, RTEL1, PARN)

5.8.1. Antifibrotic Medications

5.8.2. Immunosuppression

5.8.3. Lung Transplantation

5.8.4. Malignancy, Liver, and Bone Marrow Surveillance

5.9. Surfactant Protein Gene Variants (SFTPC, SFTPA1, SFTPA2, ABCA3)

5.9.1. Lung Cancer Screening

5.9.2. Antifibrotic Therapy

5.9.3. Early Transplant Referral

5.10. MUC5B Promoter Variant

Prognosis

5.11. Hermansky–Pudlak Syndrome

Management of Bleeding Risk

5.12. Pulmonary Fibrosis Treatment

5.13. Family Counselling and Cascade Testing

6. Genetic Biomarkers and Therapeutic Targets

6.1. Biomarkers for Diagnosis and Prognosis

6.2. Protein Biomarkers

6.3. Emerging Therapeutic Strategies

6.3.1. Telomerase Activation

6.3.2. Endoplasmic Reticulum (ER) Stress

6.3.3. Mucociliary Clearance and Airway Mucus Hypersecretion

6.3.4. Inflammatory Pathways and Innate Immunity

7. Future Perspectives and Precision Medicine

8. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| PPF | progressive pulmonary fibrosis |

| IPF | idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis |

| GWAS | genome-wide association studies |

| TGF-β | transforming growth factor-β |

| VUS | variants of uncertain significance |

| PRS | polygenic risk scores |

| MMP-7 | matrix metalloproteinase-7 |

| FPF | familial pulmonary fibrosis |

| DNA | deoxyribonucleic acid |

| RNA | ribonucleic acid |

| MAF | minor allele frequency |

| FVC | forced vital capacity |

| DLCO | Diffusing Capacity of the Lungs for Carbon Monoxide |

| mTOR | mammalian target of rapamycin |

| NSIP | nonspecific interstitial pneumonia |

| DIP | desquamative interstitial pneumonia |

| UIP | usual interstitial pneumonia |

| ILD | interstitial lung disease |

| CT | computed tomography |

| HRCT | high-resolution computed tomography |

| SNP | single-nucleotide polymorphisms |

| TLR | Toll-like receptor |

| FISH | fluorescent in situ hybridization |

| NGS | next-generation sequencing |

| WES/WGS | whole-exome/whole-genome sequencing |

| ER | endoplasmic reticulum |

| RA-ILD | rheumatoid-arthritis-associated interstitial lung disease |

References

- Allen, R.J.; Guillen-Guio, B.; Croot, E.; Kraven, L.M.; Moss, S.; Stewart, I.; Jenkins, R.G.; Wain, L.V. Genetic overlap between idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis and COVID-19. Eur. Respir. J. 2022, 60, 2103132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Froidure, A.; Wémeau-Stervinou, L.; Cottin, V. The genetics of pulmonary fibrosis: From rare to common variants. Hum. Genet. 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Golchin, N.; Patel, A.; Scheuring, J.; Wan, V.; Hofer, K.; Collet, J.-P.; Elpers, B.; Lesperance, T. Incidence and prevalence of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: A systematic literature review and meta-analysis. BMC Pulm. Med. 2025, 25, 378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raghu, G.; Remy-Jardin, M.; Richeldi, L.; Thomson, C.C.; Inoue, Y.; Johkoh, T.; Kreuter, M.; Lynch, D.A.; Maher, T.M.; Martinez, F.J.; et al. Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis (an Update) and Progressive Pulmonary Fibrosis in Adults: An Official ATS/ERS/JRS/ALAT Clinical Practice Guideline. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2022, 205, e18–e47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wijsenbeek, M.; Cottin, V. Spectrum of Fibrotic Lung Diseases. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 383, 958–968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sgalla, G.; Iovene, B.; Calvello, M.; Ori, M.; Varone, F.; Richeldi, L. Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: Pathogenesis and management. Respir. Res. 2018, 19, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pulmonary Fibrosis Foundation. Genetic Testing in Pulmonary Fibrosis for Health Care Providers; Pulmonary Fibrosis Foundation: Chicago, IL, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, D.; Newton, C.A. Familial Pulmonary Fibrosis: Genetic Features and Clinical Implications. Chest 2021, 160, 1764–1773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, R.J.; Martinez, F.J.; Jenkins, R.G. Genome-wide association study of progressive fibrosing interstitial lung disease. medRxiv 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adegunsoye, A.; Kropski, J.A.; Behr, J.; Blackwell, T.S.; Corte, T.J.; Cottin, V.; Glanville, A.R.; Glassberg, M.K.; Griese, M.; Hunninghake, G.M.; et al. Genetics and Genomics of Pulmonary Fibrosis: Charting the Molecular Landscape and Shaping Precision Medicine. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2024, 210, 401–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seibold, M.A.; Wise, A.L.; Speer, M.C.; Steele, M.P.; Brown, K.K.; Loyd, J.E.; Fingerlin, T.E.; Zhang, W.; Gudmundsson, G.; Groshong, S.D.; et al. A common MUC5B promoter polymorphism and pulmonary fibrosis. N. Engl. J. Med. 2011, 364, 1503–1512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stuart, B.D.; Choi, J.; Zaidi, S.; Xing, C.; Holohan, B.; Chen, R.; Choi, M.; Dharwadkar, P.; Torres, F.; Girod, C.E.; et al. Exome sequencing links mutations in PARN and RTEL1 with familial pulmonary fibrosis and telomere shortening. Nat. Genet. 2015, 47, 512–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armanios, M.; Blackburn, E.H. The telomere syndromes. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2012, 13, 693–704, Erratum in Nat. Rev. Genet. 2013, 14, 235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Noth, I.; Garcia, J.G.N.; Kaminski, N. A variant in the promoter of MUC5B and idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. N. Engl. J. Med. 2011, 364, 1576–1577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alonso-Gonzalez, A.; Tosco-Herrera, E.; Molina-Molina, M.; Flores, C. Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis and the role of genetics in the era of precision medicine. Front. Med. 2023, 10, 1152211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peljto, A.L.; Zhang, Y.; Fingerlin, T.E.; Ma, S.-F.; Garcia, J.G.N.; Richards, T.J.; Silveira, L.J.; Lindell, K.O.; Steele, M.P.; Loyd, J.E.; et al. Association between the MUC5B promoter polymorphism and survival in patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. JAMA 2013, 309, 2232–2239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Biondini, D.; Cocconcelli, E.; Bernardinello, N.; Lorenzoni, G.; Rigobello, C.; Lococo, S.; Castelli, G.; Baraldo, S.; Cosio, M.G.; Gregori, D.; et al. Prognostic role of MUC5B rs35705950 genotype in patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) on antifibrotic treatment. Respir. Res. 2021, 22, 98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dhooria, S.; Bal, A.; Sehgal, I.S.; Prasad, K.T.; Kashyap, D.; Sharma, R.; Muthu, V.; Agarwal, R.; Aggarwal, A.N. MUC5B Promoter Polymorphism and Survival in Indian Patients With Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis. Chest 2022, 162, 824–827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, H.; Hu, Y.; Shang, L.; Li, Y.; Yang, L.; Chen, Y. Association between MUC5B polymorphism and susceptibility and severity of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Int. J. Clin. Exp. Pathol. 2015, 8, 14953–14958. [Google Scholar]

- Allen, R.J.; Porte, J.; Braybrooke, R.; Flores, C.; Fingerlin, T.E.; Oldham, J.M.; Guillen-Guio, B.; Ma, S.-F.; Okamoto, T.; John, A.E.; et al. Genetic variants associated with susceptibility to idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis in people of European ancestry: A genome-wide association study. Lancet Respir. Med. 2017, 5, 869–880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fingerlin, T.E.; Murphy, E.; Zhang, W.; Peljto, A.L.; Brown, K.K.; Steele, M.P.; Loyd, J.E.; Cosgrove, G.P.; Lynch, D.; Groshong, S.; et al. Genome-wide association study identifies multiple susceptibility loci for pulmonary fibrosis. Nat. Genet. 2013, 45, 613–620, Erratum in Nat. Genet. 2013, 45, 1409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, A.; Mathai, S.K.; Schwartz, D.A. Recent advances in the genetics of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Curr. Opin. Pulm. Med. 2023, 29, 399–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doubkova, M.; Kriegova, E.; Littnerova, S.; Schneiderova, P.; Sterclova, M.; Bartos, V.; Plackova, M.; Zurkova, M.; Bittenglova, R.; Lostaková, V.; et al. DSP rs2076295 variants influence nintedanib and pirfenidone outcomes in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: A pilot study. Ther. Adv. Respir. Dis. 2021, 15, 17534666211042529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonella, F.; Campo, I.; Zorzetto, M.; Boerner, E.; Ohshimo, S.; Theegarten, D.; Taube, C.; Costabel, U. Potential clinical utility of MUC5B und TOLLIP single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in the management of patients with IPF. Orphanet J. Rare Dis. 2021, 16, 111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oldham, J.M.; Ma, S.-F.; Martinez, F.J.; Anstrom, K.J.; Raghu, G.; Schwartz, D.A.; Valenzi, E.; Witt, L.; Lee, C.; Vij, R.; et al. TOLLIP, MUC5B, and the Response to N-Acetylcysteine among Individuals with Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2015, 192, 1475–1482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lipinski, J.H.; Erb-Downward, J.R.; Huffnagle, G.B.; Flaherty, K.R.; Martinez, F.J.; Moore, B.B.; Dickson, R.P.; Noth, I.; O’Dwyer, D.N. Toll-Interacting Protein and Altered Lung Microbiota in Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2022, 206, 224–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, Y.; Li, Z.; Ren, Y.; Dai, H. Association of family sequence similarity gene 13A gene polymorphism and interstitial lung disease susceptibility: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Mol. Genet. Genom. Med. 2023, 11, e2279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathai, S.K.; Pedersen, B.S.; Smith, K.; Russell, P.; Schwarz, M.I.; Brown, K.K.; Steele, M.P.; Loyd, J.E.; Crapo, J.D.; Silverman, E.K.; et al. Desmoplakin Variants Are Associated with Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2016, 193, 1151–1160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobbs, B.D. Genetic Association Study Advances Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis Pathophysiology and Health Equity. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2022, 206, 4–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hollmén, M.; Laaka, A.; Partanen, J.J.; Koskela, J.; Sutinen, E.; Kaarteenaho, R.; Ainola, M.; Myllärniemi, M. KIF15 missense variant is associated with the early onset of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Respir. Res. 2023, 24, 240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammadi-Nejad, A.-R.; Allen, R.J.; Kraven, L.M.; Leavy, O.C.; Jenkins, R.G.; Wain, L.V.; Auer, D.P.; Sotiropoulos, S.N. DEMISTIFI Consortium. Mapping brain endophenotypes associated with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis genetic risk. eBioMedicine 2022, 86, 104356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerezales, P.; Cruz, M.J. Spanish Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Management of Familial Pulmonary Fibrosis. Arch. Bronconeumol. 2022, 58, 210–220. [Google Scholar]

- Cogan, J.D.; Kropski, J.A.; Zhao, M.; Mitchell, D.B.; Rives, L.; Markin, C.; Garnett, E.T.; Montgomery, K.H.; Mason, W.R.; McKean, D.F.; et al. Rare variants in RTEL1 are associated with familial interstitial pneumonia. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2015, 191, 646–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borie, R.; Bouvry, D.; Cottin, V.; Gauvain, C.; Cazes, A.; Debray, M.-P.; Cadranel, J.; Dieude, P.; Degot, T.; Dominique, S.; et al. Regulator of telomere length 1 (RTEL1) mutations are associated with heterogeneous pulmonary and extra-pulmonary phenotypes. Eur. Respir. J. 2019, 53, 1800508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diaz de Leon, A.; Cronkhite, J.T.; Katzenstein, A.-L.A.; Godwin, J.D.; Raghu, G.; Glazer, C.S.; Rosenblatt, R.L.; Girod, C.E.; Garrity, E.R.; Xing, C.; et al. Telomere lengths, pulmonary fibrosis and telomerase (TERT) mutations. PLoS ONE 2010, 5, e10680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia, C.K. Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: Update on genetic discoveries. Proc. Am. Thorac. Soc. 2011, 8, 158–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borie, R.; Tabèze, L.; Thabut, G.; Nunes, H.; Cottin, V.; Marchand-Adam, S.; Prevot, G.; Tazi, A.; Cadranel, J.; Mal, H.; et al. Prevalence and characteristics of TERT and TERC mutations in suspected genetic pulmonary fibrosis. Eur. Respir. J. 2016, 48, 1721–1731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newton, C.A.; Batra, K.; Torrealba, J.; Kozlitina, J.; Glazer, C.S.; Aravena, C.; Meyer, K.; Raghu, G.; Collard, H.R.; Garcia, C.K. Telomere-related lung fibrosis is diagnostically heterogeneous but uniformly progressive. Eur. Respir. J. 2016, 48, 1710–1720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baratella, E.; Ruaro, B.; Giudici, F.; Wade, B.; Santagiuliana, M.; Salton, F.; Confalonieri, P.; Simbolo, M.; Scarpa, A.; Tollot, S.; et al. Evaluation of Correlations between Genetic Variants and High-Resolution Computed Tomography Patterns in Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis. Diagnostics 2021, 11, 762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Philippot, Q.; Kannengiesser, C.; Debray, M.P.; Gauvain, C.; Ba, I.; Vieri, M.; Gondouin, A.; Naccache, J.-M.; Reynaud-Gaubert, M.; Uzunhan, Y.; et al. Interstitial lung diseases associated with mutations of poly(A)-specific ribonuclease: A multicentre retrospective study. Respirology 2022, 27, 226–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alder, J.K.; Chen, J.J.L.; Lancaster, L.; Danoff, S.; Su, S.C.; Cogan, J.D.; Vulto, I.; Xie, M.; Qi, X.; Tuder, R.M.; et al. Short telomeres are a risk factor for idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2008, 105, 13051–13056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borie, R.; Kannengiesser, C.; Hirschi, S.; Le Pavec, J.; Mal, H.; Bergot, E.; Jouneau, S.; Naccache, J.-M.; Revy, P.; Boutboul, D.; et al. Severe hematologic complications after lung transplantation in patients with telomerase complex mutations. J. Heart Lung Transplant. 2015, 34, 538–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, A.Q.; Lane, K.; Phillips, J.; Prince, M.; Markin, C.; Speer, M.; Schwartz, D.A.; Gaddipati, R.; Marney, A.; Johnson, J.; et al. Heterozygosity for a surfactant protein C gene mutation associated with usual interstitial pneumonitis and cellular nonspecific interstitial pneumonitis in one kindred. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2002, 165, 1322–1328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salerno, T.; Peca, D.; Menchini, L.; Schiavino, A.; Boldrini, R.; Esposito, F.; Danhaive, O.; Cutrera, R. Surfactant Protein C-associated interstitial lung disease; three different phenotypes of the same SFTPC mutation. Ital. J. Pediatr. 2016, 42, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ono, S.; Tanaka, T.; Ishida, M.; Kinoshita, A.; Fukuoka, J.; Takaki, M.; Sakamoto, N.; Ishimatsu, Y.; Kohno, S.; Hayashi, T.; et al. Surfactant protein C G100S mutation causes familial pulmonary fibrosis in Japanese kindred. Eur. Respir. J. 2011, 38, 861–869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glasser, S.W.; Hardie, W.D.; Hagood, J.S. Pathogenesis of Interstitial Lung Disease in Children and Adults. Pediatr. Allergy Immunol. Pulmonol. 2010, 23, 9–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Moorsel, C.H.M.; van der Vis, J.J.; Grutters, J.C. Genetic disorders of the surfactant system: Focus on adult disease. Eur. Respir. Rev. Off. J. Eur. Respir. Soc. 2021, 30, 200085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Legendre, M.; Butt, A.; Borie, R.; Debray, M.P.; Bouvry, D.; Filhol-Blin, E.; Desroziers, T.; Nau, V.; Copin, B.; Dastot-Le Moal, F.; et al. Functional assessment and phenotypic heterogeneity of SFTPA1 and SFTPA2 mutations in interstitial lung diseases and lung cancer. Eur. Respir. J. 2020, 56, 2002806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Seidl, E.; Knoflach, K.; Gothe, F.; Forstner, M.E.; Michel, K.; Pawlita, I.; Gesenhues, F.; Sattler, F.; Yang, X.; et al. ABCA3-related interstitial lung disease beyond infancy. Thorax 2023, 78, 587–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campo, I.; Zorzetto, M.; Mariani, F.; Kadija, Z.; Morbini, P.; Dore, R.; Kaltenborn, E.; Frixel, S.; Zarbock, R.; Liebisch, G.; et al. A large kindred of pulmonary fibrosis associated with a novel ABCA3 gene variant. Respir. Res. 2014, 15, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nolan, J.; Rodgers, J.; Mackintosh, J.A. ABCA3 Surfactant-Related Gene Variant Associated Interstitial Lung Disease in Adults: A Case Series and Review of the Literature. Respirol. Case Rep. 2025, 13, e70304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vicary, G.W.; Vergne, Y.; Santiago-Cornier, A.; Young, L.R.; Roman, J. Pulmonary Fibrosis in Hermansky-Pudlak Syndrome. Ann. Am. Thorac. Soc. 2016, 13, 1839–1846, Erratum in Ann. Thorac. Soc. 2017, 14, 152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huizing, M.; Malicdan, M.C.V.; Wang, J.A.; Pri-Chen, H.; Hess, R.A.; Fischer, R.; O’Brien, K.J.; Merideth, M.A.; Gahl, W.A.; Gochuico, B.R. Hermansky-Pudlak syndrome: Mutation update. Hum. Mutat. 2020, 41, 543–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Jesus Rojas, W.; Young, L.R. Hermansky–Pudlak Syndrome. Semin. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2020, 41, 238–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hengst, M.; Naehrlich, L.; Mahavadi, P.; Grosse-Onnebrink, J.; Terheggen-Lagro, S.; Skanke, L.H.; Schuch, L.A.; Brasch, F.; Guenther, A.; Reu, S.; et al. Hermansky-Pudlak syndrome type 2 manifests with fibrosing lung disease early in childhood. Orphanet J. Rare Dis. 2018, 13, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.; Wei, Z.; Wu, Y.; Zhao, M.; Zhou, L.; Lin, Q. Pathogenesis and Therapy of Hermansky–Pudlak Syndrome (HPS)-Associated Pulmonary Fibrosis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 11270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yokoyama, T.; Gochuico, B.R. Hermansky-Pudlak syndrome pulmonary fibrosis: A rare inherited interstitial lung disease. Eur. Respir. Rev. 2021, 30, 200193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, I.V.; Schwartz, D.A. Epigenetic control of gene expression in the lung. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2011, 183, 1295–1301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanders, Y.Y.; Ambalavanan, N.; Halloran, B.; Zhang, X.; Liu, H.; Crossman, D.K.; Bray, M.; Zhang, K.; Thannickal, V.J.; Hagood, J.S. Altered DNA methylation profile in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2012, 186, 525–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, L. Competing endogenous RNA networks in pulmonary fibrosis: Regulatory mechanisms and therapeutic potential. Biochem. Genet. 2024, 62, 1443–1462. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, H.; Song, M.; Guo, J.; Ma, J.; Qiu, M.; Yang, Z. The function of non-coding RNAs in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Open Med. (Wars) 2021, 16, 481–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pandit, K.V.; Corcoran, D.; Yousef, H.; Yarlagadda, M.; Tzouvelekis, A.; Gibson, K.F.; Konishi, K.; Yousem, S.A.; Singh, M.; Handley, D.; et al. Inhibition and role of let-7d in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2010, 182, 220–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Zhao, X.; Shan, H.; Liang, H. MicroRNAs in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: Involvement in pathogenesis and potential use in diagnosis and therapeutics. Acta Pharm. Sin. B 2016, 6, 531–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, D.A.; Van Hoeven, K.H.; Merchant, J.A. Genetics and environmental interactions in pulmonary fibrosis. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 2011, 73, 223–245. [Google Scholar]

- Taskar, V.S.; Coultas, D.B. Is idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis an environmental disease? Proc. Am. Thorac. Soc. 2006, 3, 293–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spagnolo, P.; Kreuter, M.; Ryerson, C.J.; Cottin, V.; Jones, M.G.; King, C.S.; de Lema, B.K.; Maher, T.M. Toward personalized medicine in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care. Med. 2024, 209, 1167–1176. [Google Scholar]

- Oldham, J.M. Polygenic risk scores in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: A step towards personalized medicine. Eur. Respir. J. 2023, 62, 2300897. [Google Scholar]

- Moll, M.; Peljto, A.L.; Kim, J.S.; Xu, H.; Debban, C.L.; Chen, X.; Menon, A.; Putman, R.K.; Ghosh, A.J.; Saferali, A.; et al. A Polygenic Risk Score for Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis and Interstitial Lung Abnormalities. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2023, 208, 791–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Richards, S.; Aziz, N.; Bale, S.; Bick, D.; Das, S.; Gastier-Foster, J.; Grody, W.W.; Hegde, M.; Lyon, E.; Spector, E.; et al. ACMG Laboratory Quality Assurance Committee. Standards and guidelines for the interpretation of sequence variants: A joint consensus recommendation of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics and the Association for Molecular Pathology. Genet Med. 2015, 17, 405–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Raghu, G.; Rochwerg, B.; Zhang, Y.; Garcia, C.A.C.; Azuma, A.; Behr, J.; Brozek, J.L.; Collard, H.R.; Cunningham, W.; Homma, S.; et al. An Official ATS/ERS/JRS/ALAT Clinical Practice Guideline: Treatment of Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis. An Update of the 2011 Clinical Practice Guideline. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2015, 192, e3–e19, Erratum in Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care. Med. 2015, 192, 644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Kuan, P.J.; Xing, C.; Cronkhite, J.T.; Torres, F.; Rosenblatt, R.L.; DiMaio, J.M.; Kinch, L.N.; Grishin, N.V.; Garcia, C.K. Genetic defects in surfactant protein A2 are associated with pulmonary fibrosis and lung cancer. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2009, 84, 52–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newton, C.A.; Oldham, J.M. Genetics of pulmonary fibrosis. Eur. Respir. Rev. 2020, 29, 200035. [Google Scholar]

- George, G.; Renzoni, E.A.; Seo, S. Lung transplantation for telomerase related interstitial lung disease: A single center experience. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2020, 201, A7633. [Google Scholar]

- Justet, A.; Debray, M.-P.; Kannengiesser, C.; Dieudé, P.; Borie, R.; Crestani, B.; Cottin, V. Safety and Efficacy of Pirfenidone and Nintedanib in Patients with Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis and Carrying a Telomere-Related Gene Mutation. Eur. Respir. J. 2021, 57, 2003198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flaherty, K.R.; Wells, A.U.; Cottin, V.; Devaraj, A.; Walsh, S.L.F.; Inoue, Y.; Richeldi, L.; Kolb, M.; Tetzlaff, K.; Stowasser, S.; et al. Nintedanib in Progressive Fibrosing Interstitial Lung Diseases. N. Engl. J. Med. 2019, 381, 1718–1727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silhan, L.L.; Shah, P.D.; Chambers, D.C.; Snyder, L.D.; Riise, G.C.; Wagner, C.L.; Hellström-Lindberg, E.; Orens, J.B.; Mewton, J.F.; Danoff, S.K.; et al. Lung transplantation in telomerase mutation carriers with pulmonary fibrosis. Eur. Respir. J. 2014, 44, 178–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- George, G.; Rosas, I.O.; Cui, Y.; McKane, C.; Hunninghake, G.M.; Camp, P.C.; Raby, B.A.; Goldberg, H.J.; El-Chemaly, S. Short telomeres, telomeropathy, and subclinical extrapulmonary organ damage in patients with interstitial lung disease. Chest 2015, 147, 1549–1557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillips-Houlbracq, M.; Mal, H.; Cottin, V.; Gauvain, C.; Beier, F.; Sicre de Fontbrune, F.; Sidali, S.; Mornex, J.F.; Hirschi, S.; Roux, A.; et al. Determinants of survival after lung transplantation in telomerase-related gene mutation carriers: A retrospective cohort. Am. J. Transplant. 2022, 22, 1236–1244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newton, C.A.; Zhang, D.; Oldham, J.M.; Kozlitina, J.; Ma, S.-F.; Martinez, F.J.; Raghu, G.; Noth, I.; Garcia, C.K. Telomere Length and Use of Immunosuppressive Medications in Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2019, 200, 336–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gahl, W.A.; Brantly, M.; Kaiser-Kupfer, M.I.; Iwata, F.; Hazelwood, S.; Shotelersuk, V.; Duffy, L.F.; Kuehl, E.M.; Troendle, J.; Bernardini, I. Genetic defects and clinical characteristics of patients with a form of oculocutaneous albinism (Hermansky-Pudlak syndrome). N. Engl. J. Med. 1998, 338, 1258–1264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spagnolo, P.; Tzouvelekis, A.; Maher, T.M. Personalized medicine in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: Facts and promises. Curr. Opin. Pulm. Med. 2015, 21, 470–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Planas-Cerezales, L.; Arias-Salgado, E.G.; Berastegui, C.; Montes-Worboys, A.; González-Montelongo, R.; Lorenzo-Salazar, J.M.; Vicens-Zygmunt, V.; Garcia-Moyano, M.; Dorca, J.; Flores, C.; et al. Lung Transplant Improves Survival and Quality of Life Regardless of Telomere Dysfunction. Front. Med. 2021, 8, 695919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kropski, J.A.; Blackwell, T.S.; Loyd, J.E. The genetic basis of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Eur. Respir. J. 2015, 45, 1717–1727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spagnolo, P.; Maher, T.M.; Richeldi, L. Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: Recent advances on pharmacological therapy. Pharmacol. Ther. 2015, 152, 18–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maher, T.M.; Simpson, J.K.; Porter, J.C.; Wilson, F.J.; Chan, R.; Eames, R.; Cui, Y.; Siederer, S.; Parry, S.; Kenny, J.; et al. A positron emission tomography imaging study to confirm target engagement in the lungs of patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis following a single dose of a novel inhaled αvβ6 integrin inhibitor. Respir. Res. 2020, 21, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Z.; Tang, M.; Wang, N.; Liu, J.; Tan, X.; Ma, H.; Luo, J.; Xie, K. Genetic variation reveals the therapeutic potential of BRSK2 in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. BMC Med. 2025, 23, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernardes de Jesus, B.; Blasco, M.A. Telomerase at the intersection of cancer and aging. Trends Genet. TIG 2013, 29, 513–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Townsley, D.M.; Dumitriu, B.; Liu, D.; Biancotto, A.; Weinstein, B.; Chen, C.; Hardy, N.; Mihalek, A.D.; Lingala, S.; Kim, Y.J.; et al. Danazol Treatment for Telomere Diseases. N. Engl. J. Med. 2016, 374, 1922–1931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mackintosh, J.A.; Pietsch, M.; Lutzky, V.; Enever, D.; Bancroft, S.; Apte, S.H.; Tan, M.; Yerkovich, S.T.; Dickinson, J.L.; Pickett, H.A.; et al. TELO-SCOPE study: A randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 2 trial of danazol for short telomere related pulmonary fibrosis. BMJ Open Respir. Res. 2021, 8, e001127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawson, W.E.; Cheng, D.-S.; Degryse, A.L.; Tanjore, H.; Polosukhin, V.V.; Xu, X.C.; Newcomb, D.C.; Jones, B.R.; Roldan, J.; Lane, K.B.; et al. Endoplasmic reticulum stress enhances fibrotic remodeling in the lungs. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2011, 108, 10562–10567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burman, A.; Tanjore, H.; Blackwell, T.S. Endoplasmic reticulum stress in pulmonary fibrosis. Matrix Biol. J. Int. Soc. Matrix Biol. 2018, 68–69, 355–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, B.; Fu, L.; Hu, B.; Zhang, Z.-C.; Tan, Z.-X.; Li, S.-R.; Chen, Y.-H.; Zhang, C.; Wang, H.; Xu, D.-X.; et al. Tauroursodeoxycholic acid alleviates pulmonary endoplasmic reticulum stress and epithelial-mesenchymal transition in bleomycin-induced lung fibrosis. BMC Pulm. Med. 2021, 21, 149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hancock, L.A.; Hennessy, C.E.; Solomon, G.M.; Dobrinskikh, E.; Estrella, A.; Hara, N.; Hill, D.B.; Kissner, W.J.; Markovetz, M.R.; Grove Villalon, D.E.; et al. Muc5b overexpression causes mucociliary dysfunction and enhances lung fibrosis in mice. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 5363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Gene/Locus | Biological Pathway/Function | Variant Type | Key Clinical Associations/Implications |

|---|---|---|---|

| MUC5B | Mucin production, mucociliary clearance | Common promoter variant (rs35705950) |

|

| TERT, TERC, PARN, RTEL1 | Telomere maintenance | Rare deleterious variants and common SNPs |

|

| SFTPC, SFTPA1, SFTPA2, ABCA3 | Surfactant metabolism and homeostasis | Rare missense/loss-of-function variants |

|

| DSP (Desmoplakin) | Cell adhesion, epithelial integrity | Common SNP (rs2076295) |

|

| TOLLIP | Innate immunity, TLR signaling | Common SNPs (rs5743890, rs3750920) |

|

| FAM13A | Wnt/β-catenin signaling, possibly (function not fully defined) | Common SNP (rs2609255) |

|

| KIF15, MAD1L1 | Mitotic spindle assembly, cell cycle regulation | Common SNPs and rare variants |

|

| DEPTOR | mTOR signaling inhibition | Common SNP |

|

| HPS1, HPS3, HPS4 | Lysosome-related organelle biogenesis (Hermansky–Pudlak Syndrome) | Rare loss-of-function variants |

|

| Genetic Finding | Key Clinical Implications |

|---|---|

| Telomere-related gene variants (TERT, TERC, RTEL1, PARN) |

|

| Surfactant protein gene variants (SFTPC, SFTPA1, SFTPA2, ABCA3) |

|

| MUC5B promoter variant (rs35705950) |

|

| Hermansky–Pudlak syndrome genes (HPS1, HPS3, HPS4) |

|

| DSP variant (rs2076295, desmoplakin) |

|

| TOLLIP variants (rs5743890, rs3750920) |

|

| Genetic Finding | Key Management Considerations |

|---|---|

| Telomere-related gene variants (TERT, TERC, RTEL1, PARN) | Antifibrotics: Use with caution; monitor for side effects (cytopenias, liver dysfunction). Immunosuppression: Generally avoid/minimize due to high risk of cytopenias and infections. Transplant: Higher peri- and post-transplant risks; requires multidisciplinary assessment and tailored immunosuppression. Surveillance: Regular monitoring for bone marrow failure, liver disease, and hematological malignancies. |

| Surfactant protein gene variants (i.e., SFTPC, SFTPA1, SFTPA2, ABCA3) | Cancer screening: Enhanced surveillance for lung adenocarcinoma (especially for SFTPA1/A2). Antifibrotics: Indicated, but efficacy may be variable; personalized assessment needed. Transplant: Consider earlier referral due to potential for rapid progression. |

| MUC5B promoter variant (rs35705950) | Prognosis: Often indicates a slower disease trajectory; may allow for less frequent monitoring in stable patients. |

| Hermansky–Pudlak Syndrome (i.e., HPS1, HPS3, HPS4) | Bleeding risk: Manage bleeding diathesis; avoid antiplatelet agents unless essential. PF Management: Disease is often aggressive; early antifibrotic therapy and transplant planning are recommended. |

| DSP rs2076295 | Treatment selection: G allele carriers may respond better to nintedanib; TT homozygotes may benefit more from pirfenidone (preliminary evidence). |

| TOLLIP variants | Prognosis and therapy: rs5743890 minor allele may indicate poorer prognosis. rs3750920 may predict response to N-acetylcysteine (historical context). |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhumagaliyeva, A.; Chorostowska-Wynimko, J.; Jezela-Stanek, A. Genetic Determinants of Progressive Pulmonary Fibrosis: A Comprehensive Review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 11846. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262411846

Zhumagaliyeva A, Chorostowska-Wynimko J, Jezela-Stanek A. Genetic Determinants of Progressive Pulmonary Fibrosis: A Comprehensive Review. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2025; 26(24):11846. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262411846

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhumagaliyeva, Ardak, Joanna Chorostowska-Wynimko, and Aleksandra Jezela-Stanek. 2025. "Genetic Determinants of Progressive Pulmonary Fibrosis: A Comprehensive Review" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 26, no. 24: 11846. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262411846

APA StyleZhumagaliyeva, A., Chorostowska-Wynimko, J., & Jezela-Stanek, A. (2025). Genetic Determinants of Progressive Pulmonary Fibrosis: A Comprehensive Review. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 26(24), 11846. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262411846