Heteroaryl Bishydrazono Nitroimidazoles: A Unique Structural Skeleton with Potent Multitargeting Antibacterial Activity

Abstract

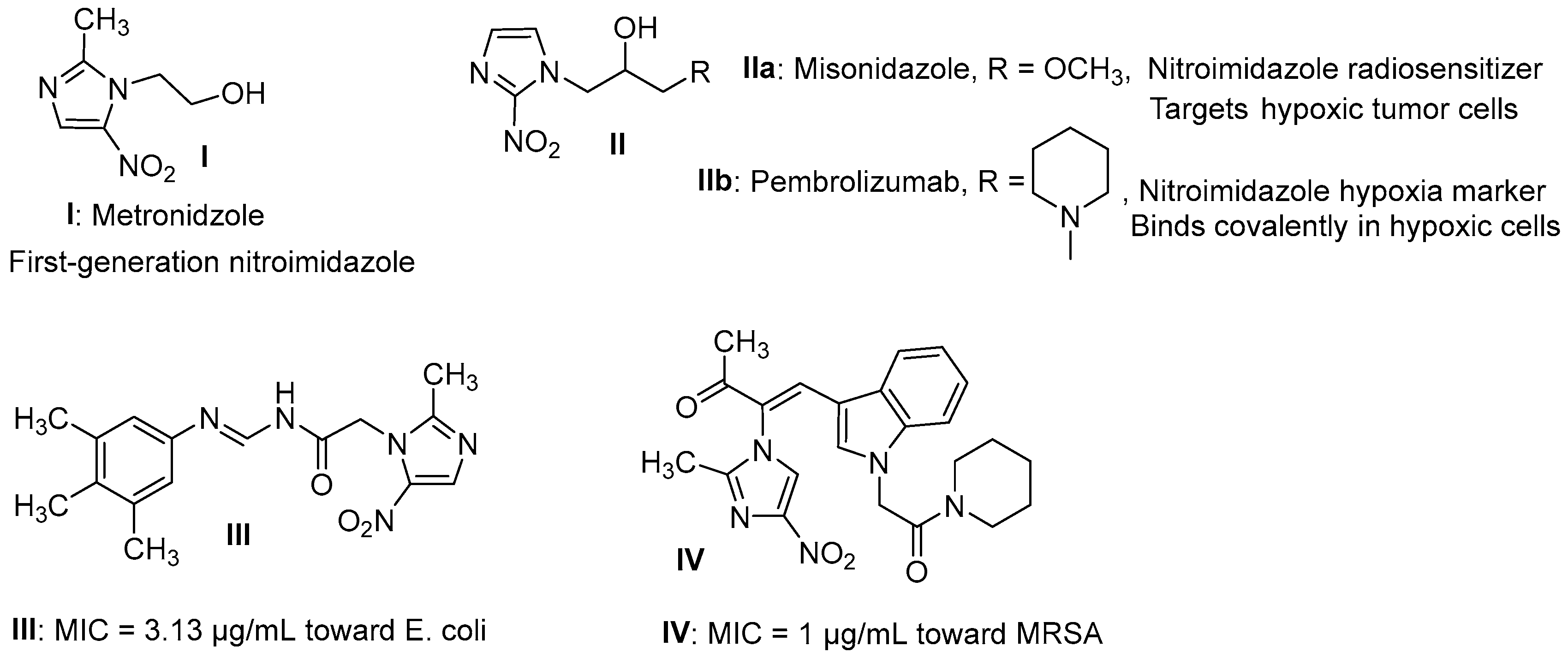

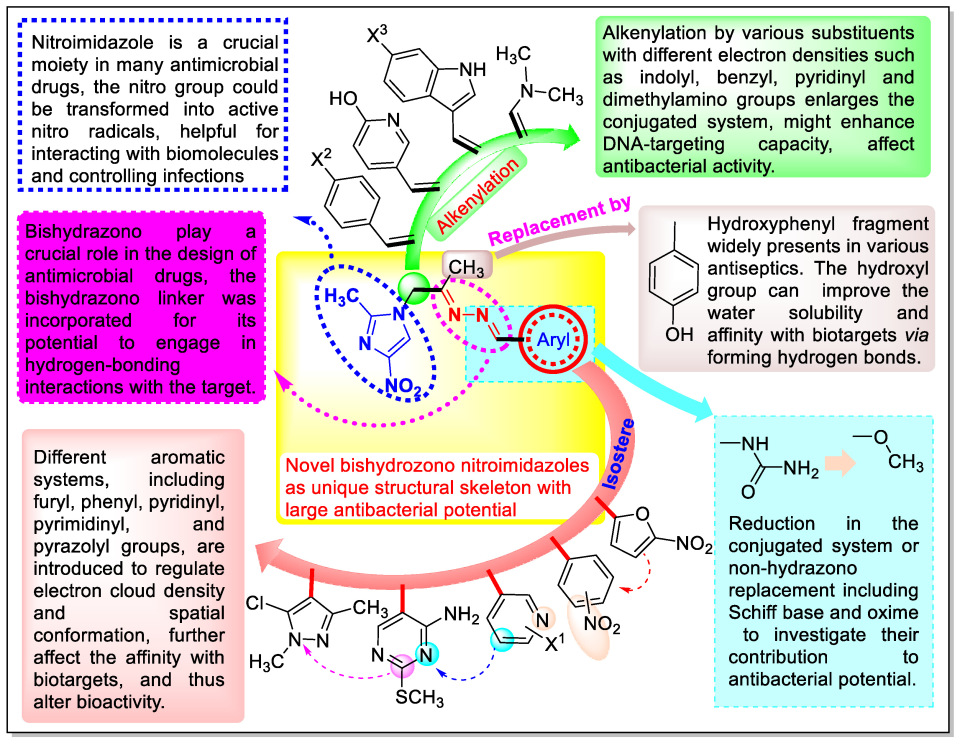

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

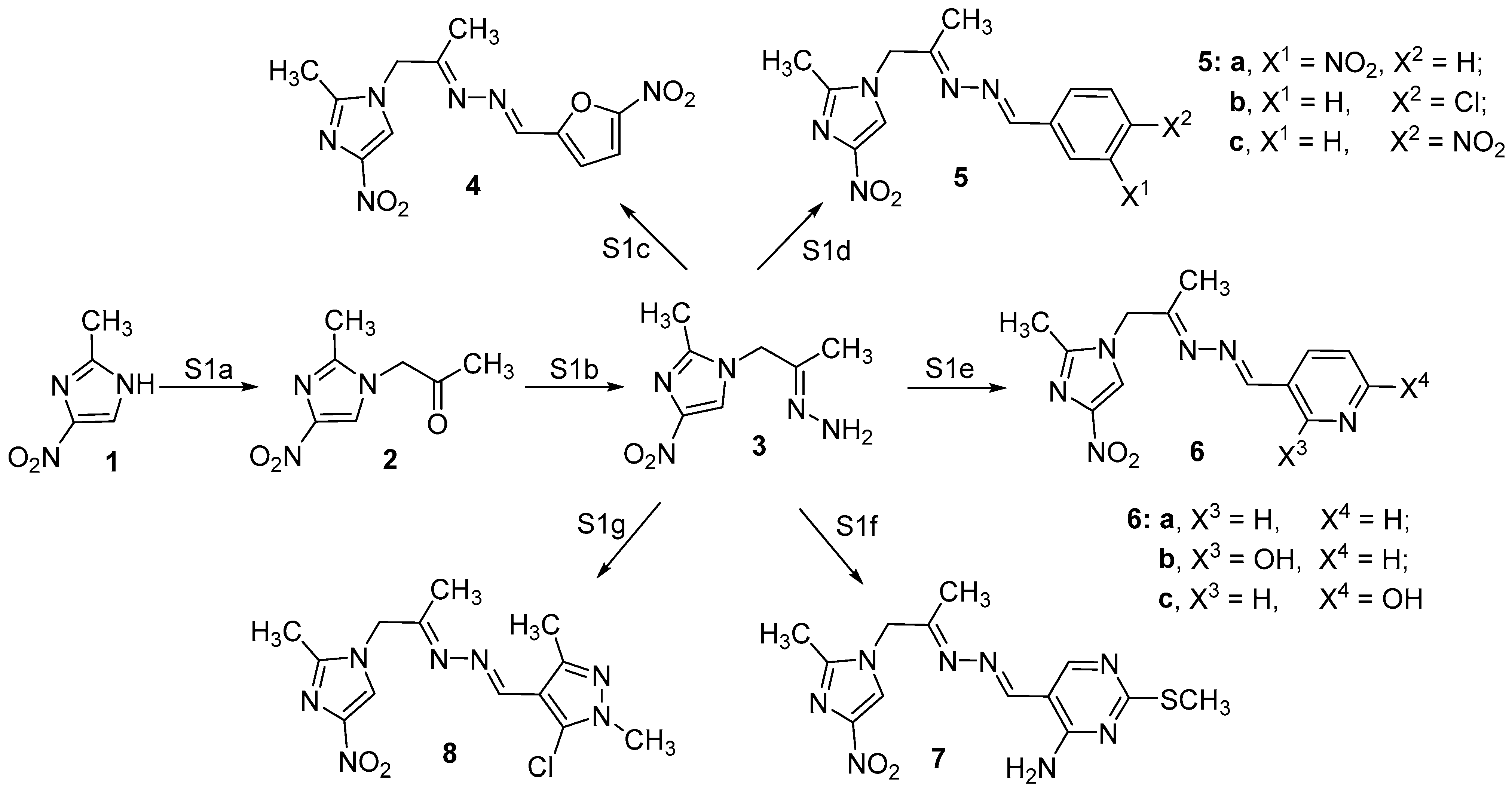

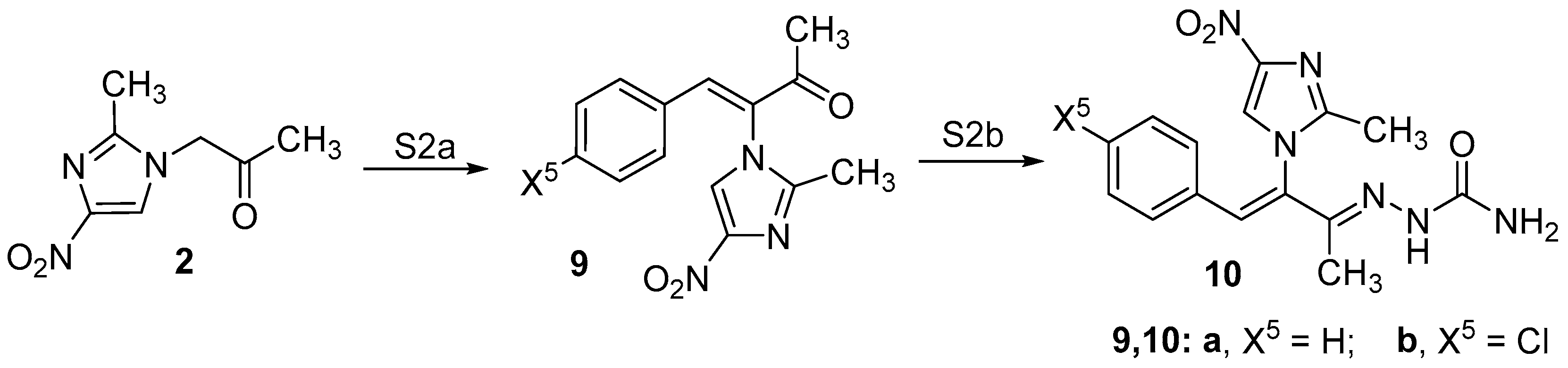

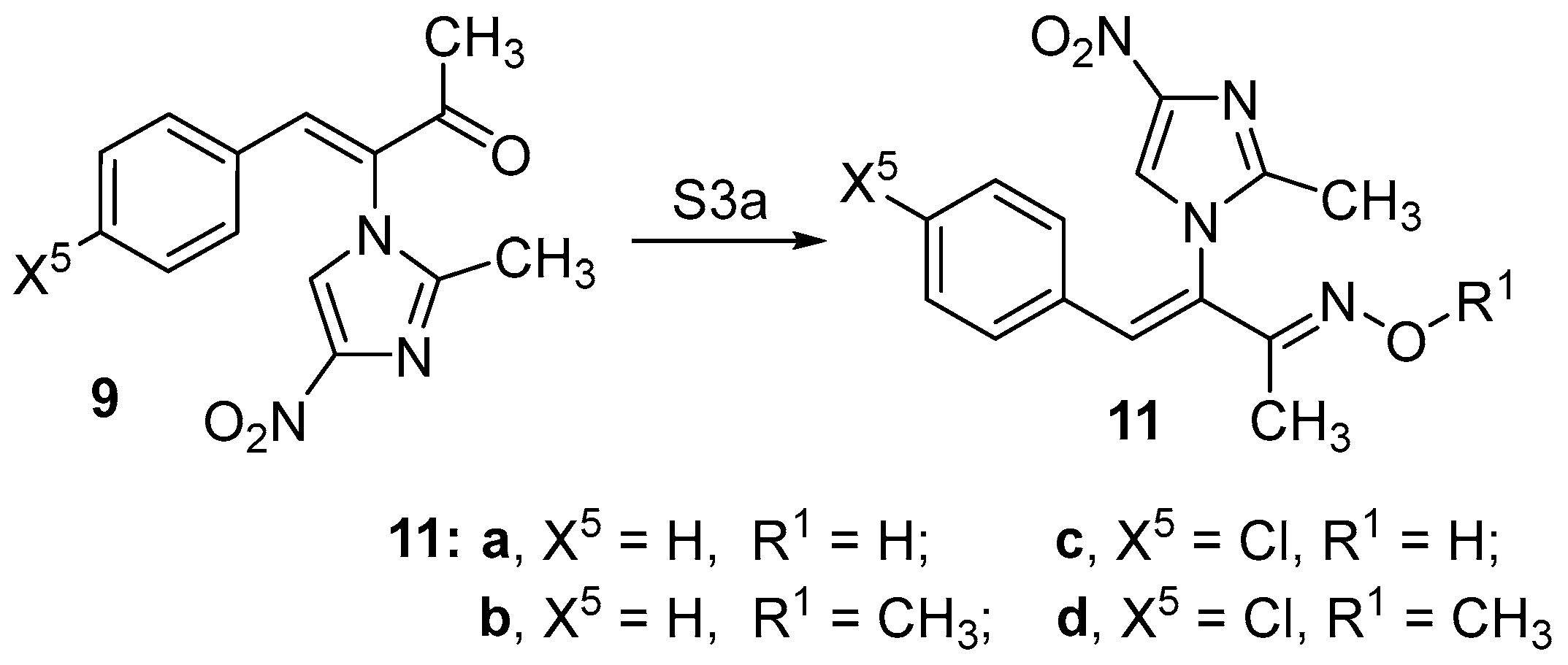

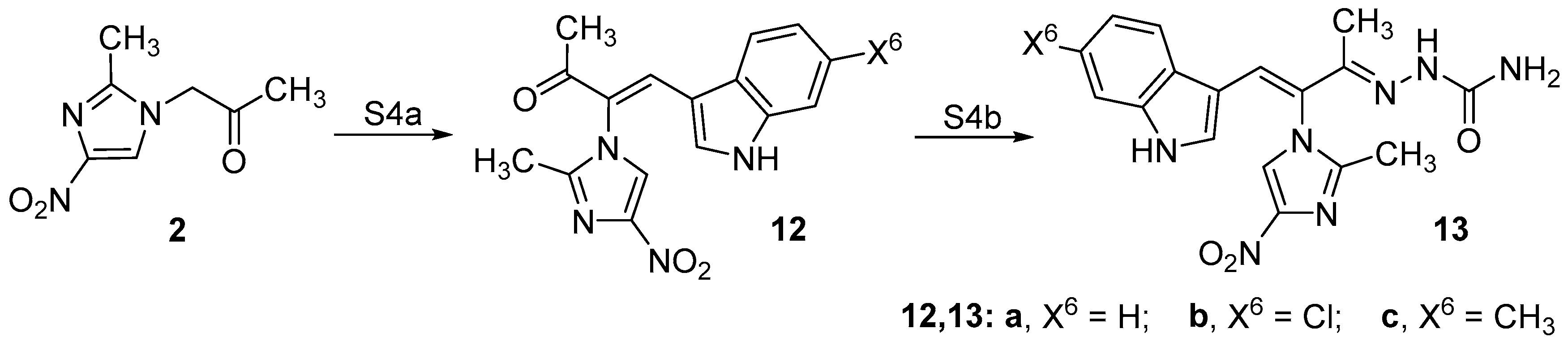

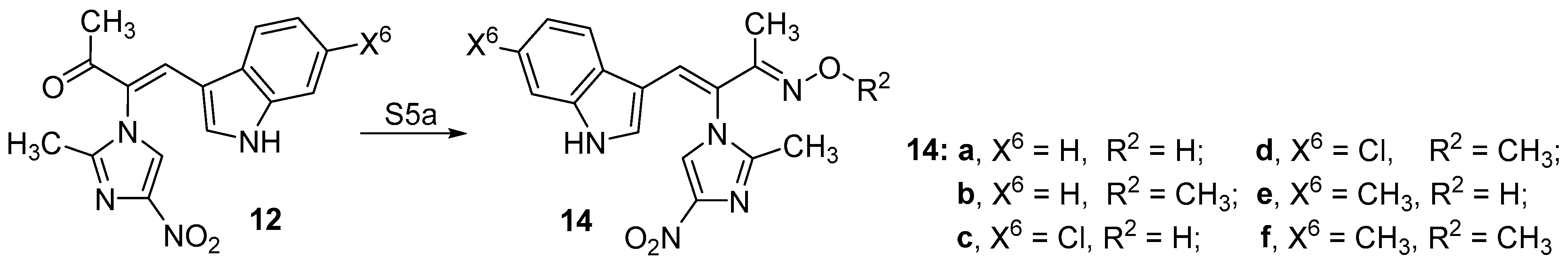

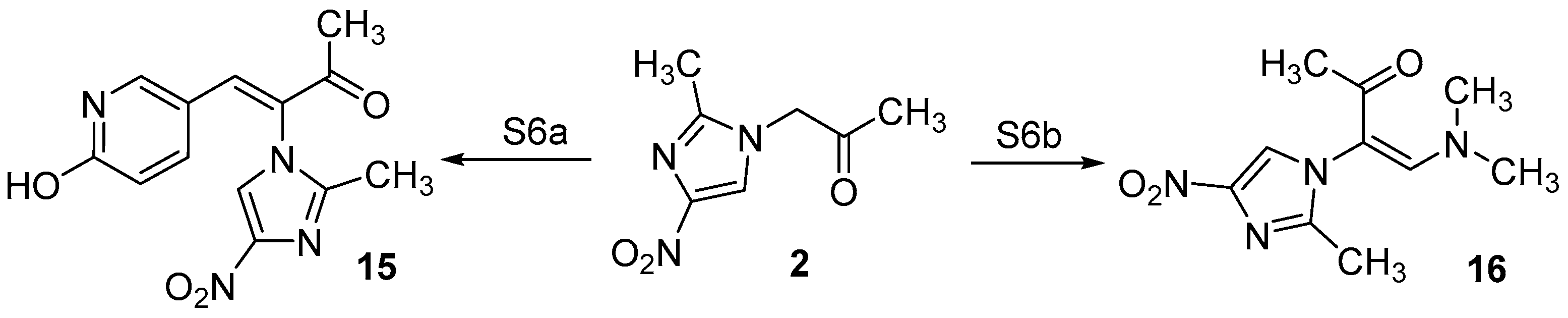

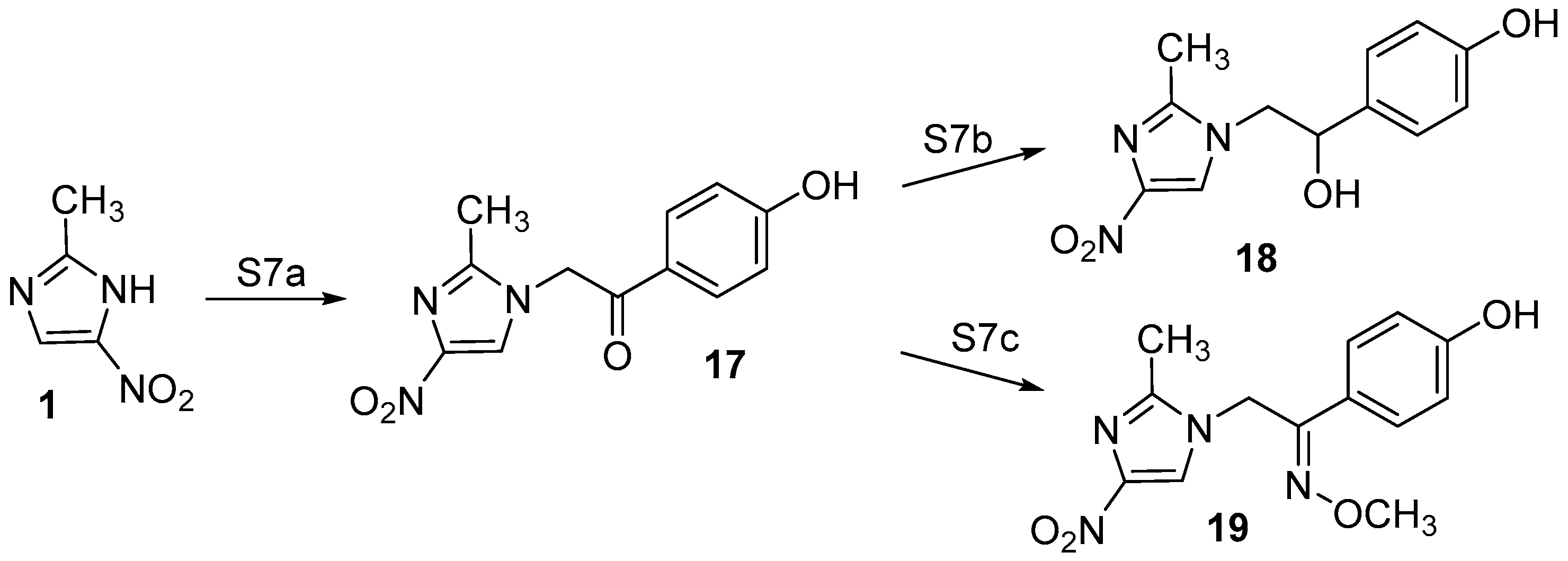

2.1. Chemistry

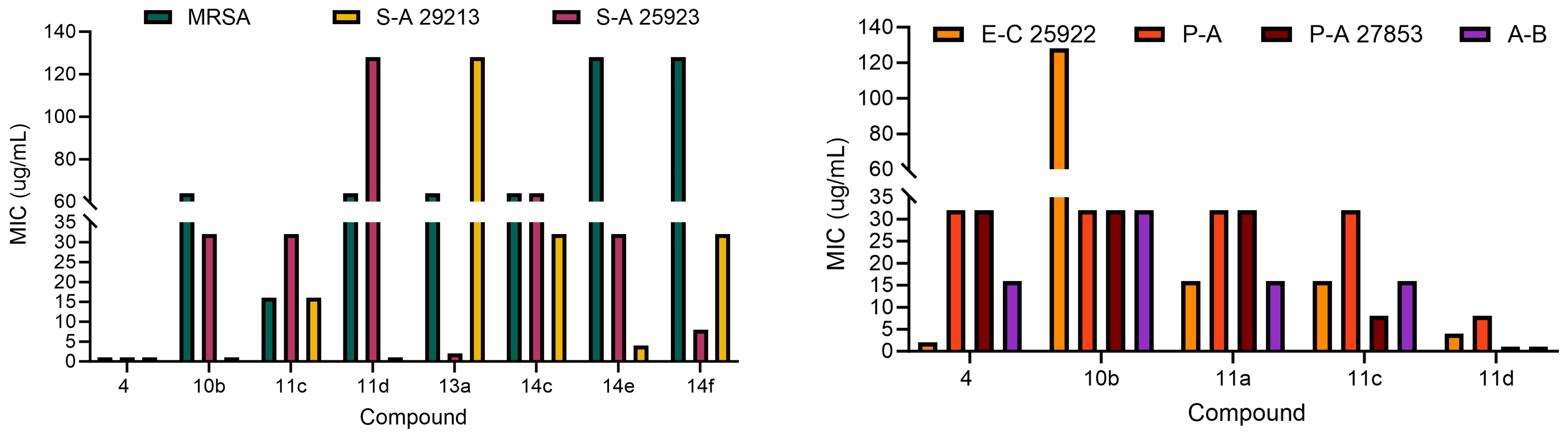

2.2. Antibacterial Activity

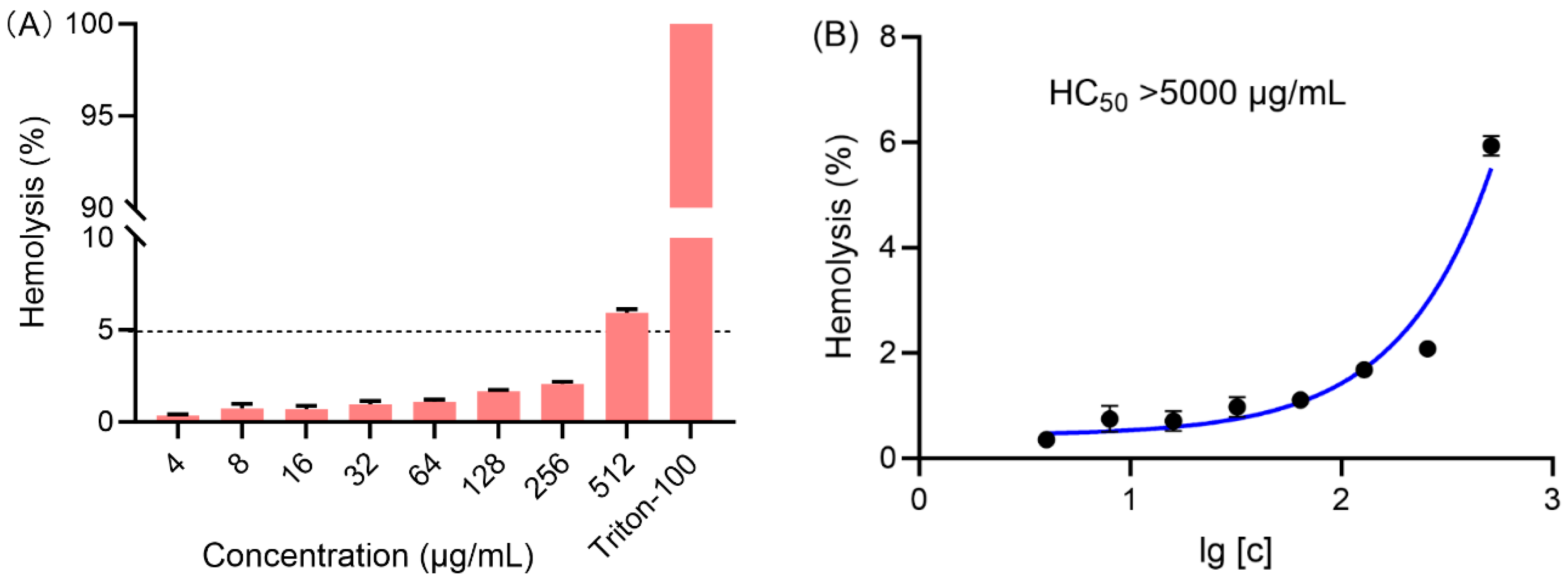

2.3. Hemolytic Study

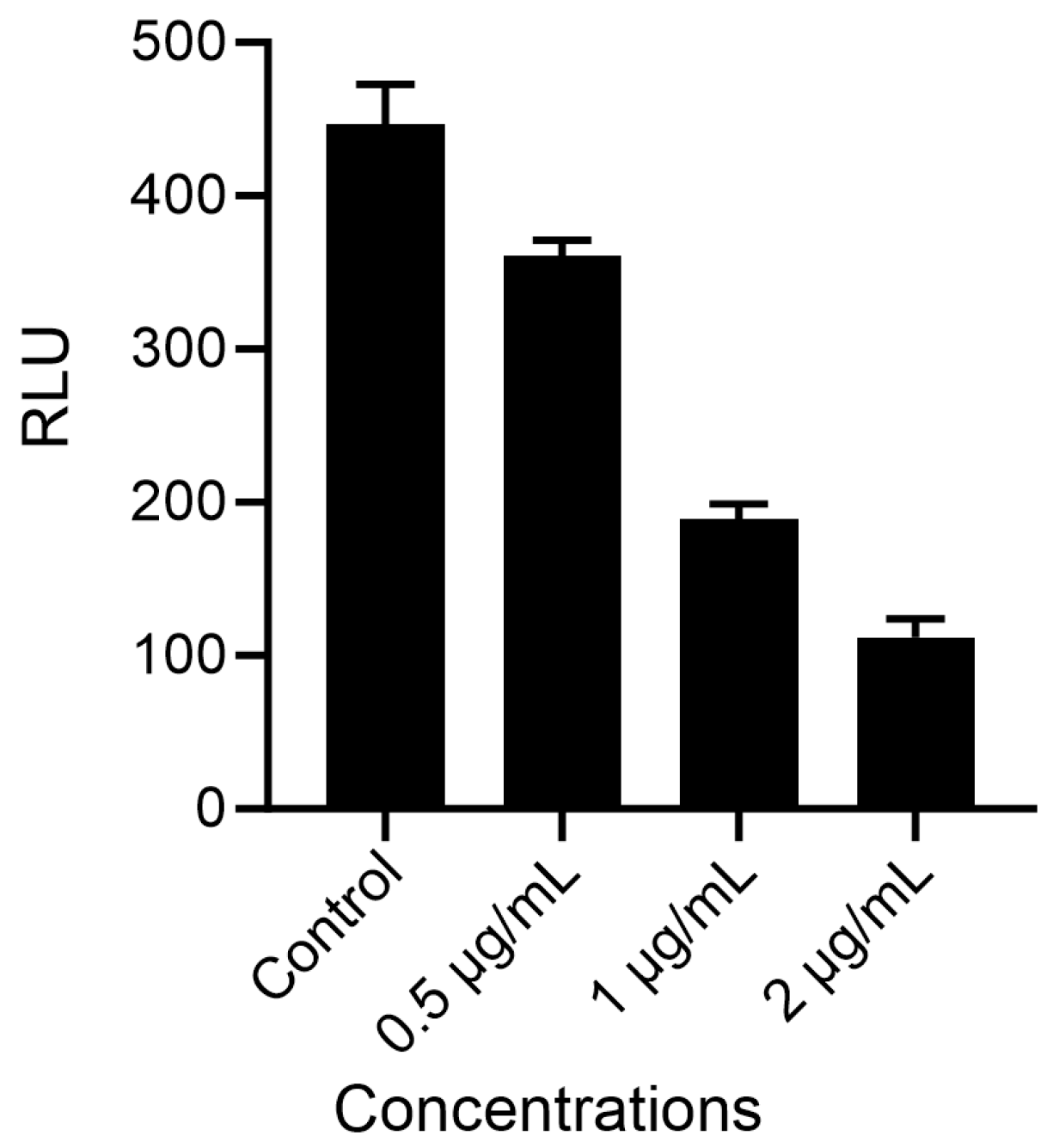

2.4. Proliferation Activity Study

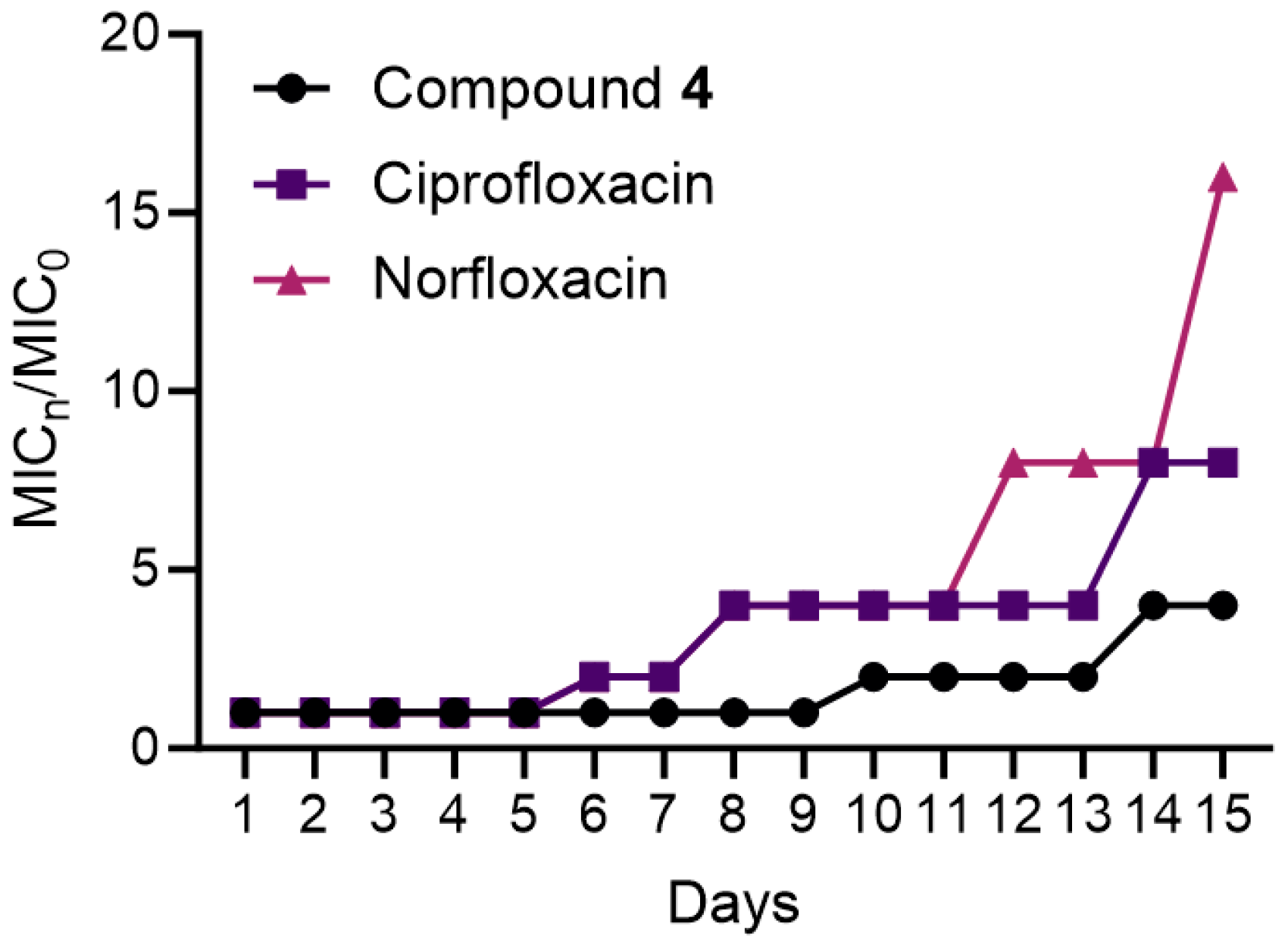

2.5. Bacterial Resistance Study

2.6. Drug Combination Effect

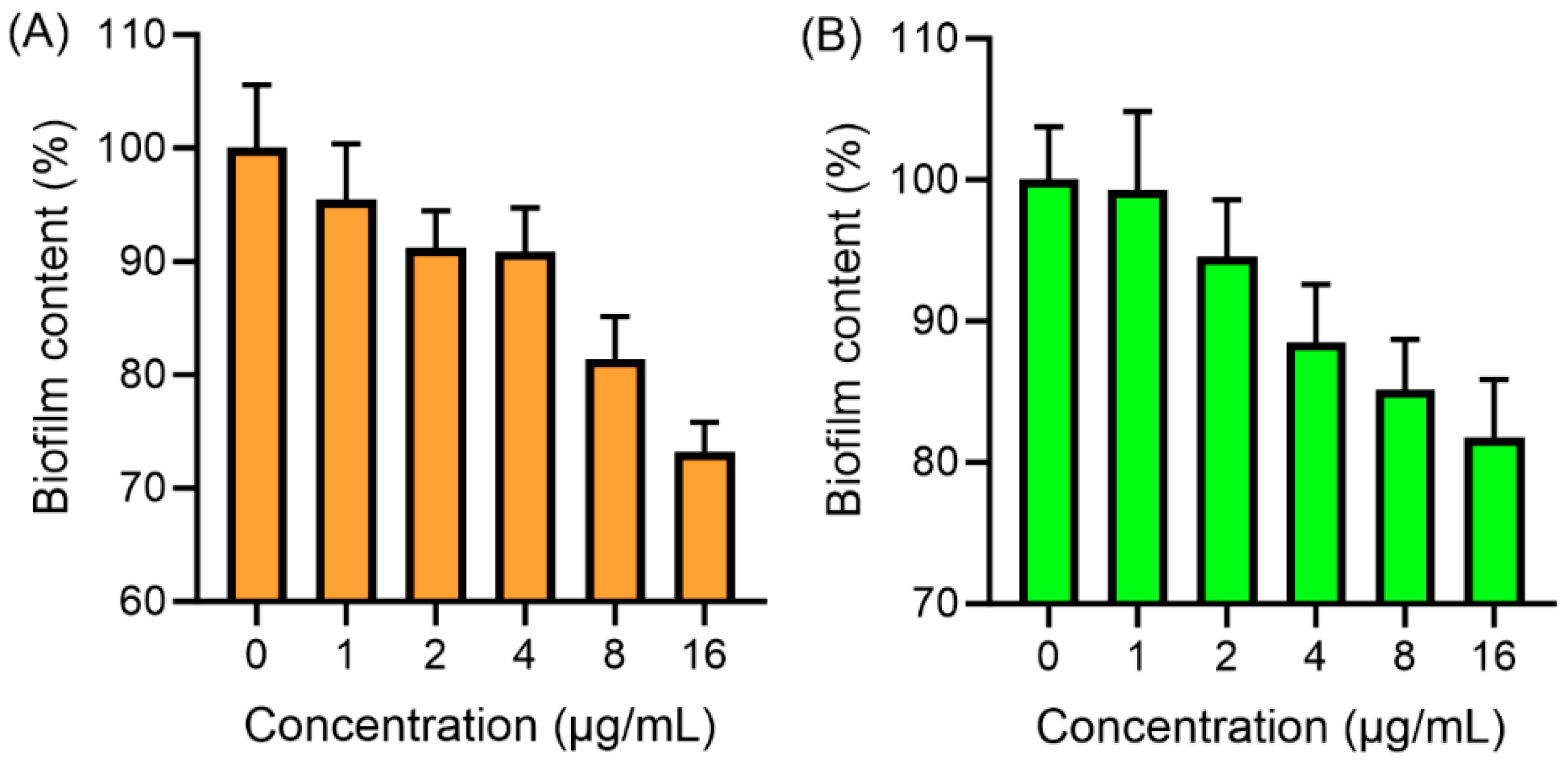

2.7. Antibiofilm Assay

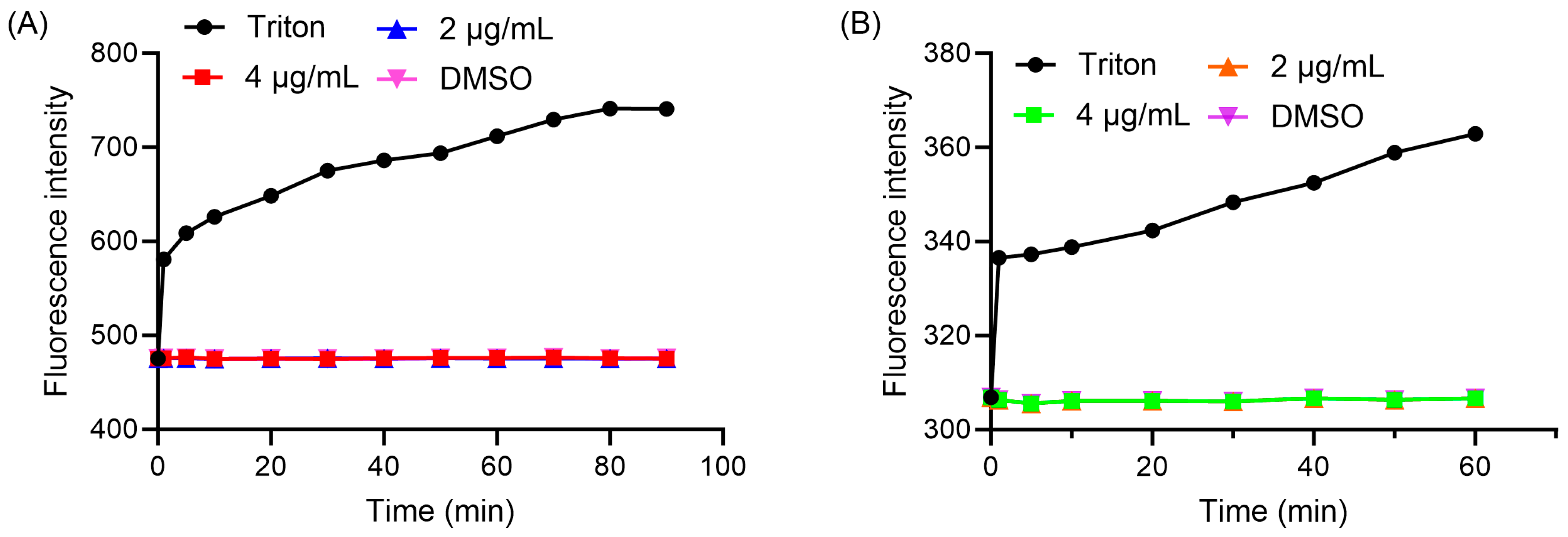

2.8. Membrane Permeability and Depolarization

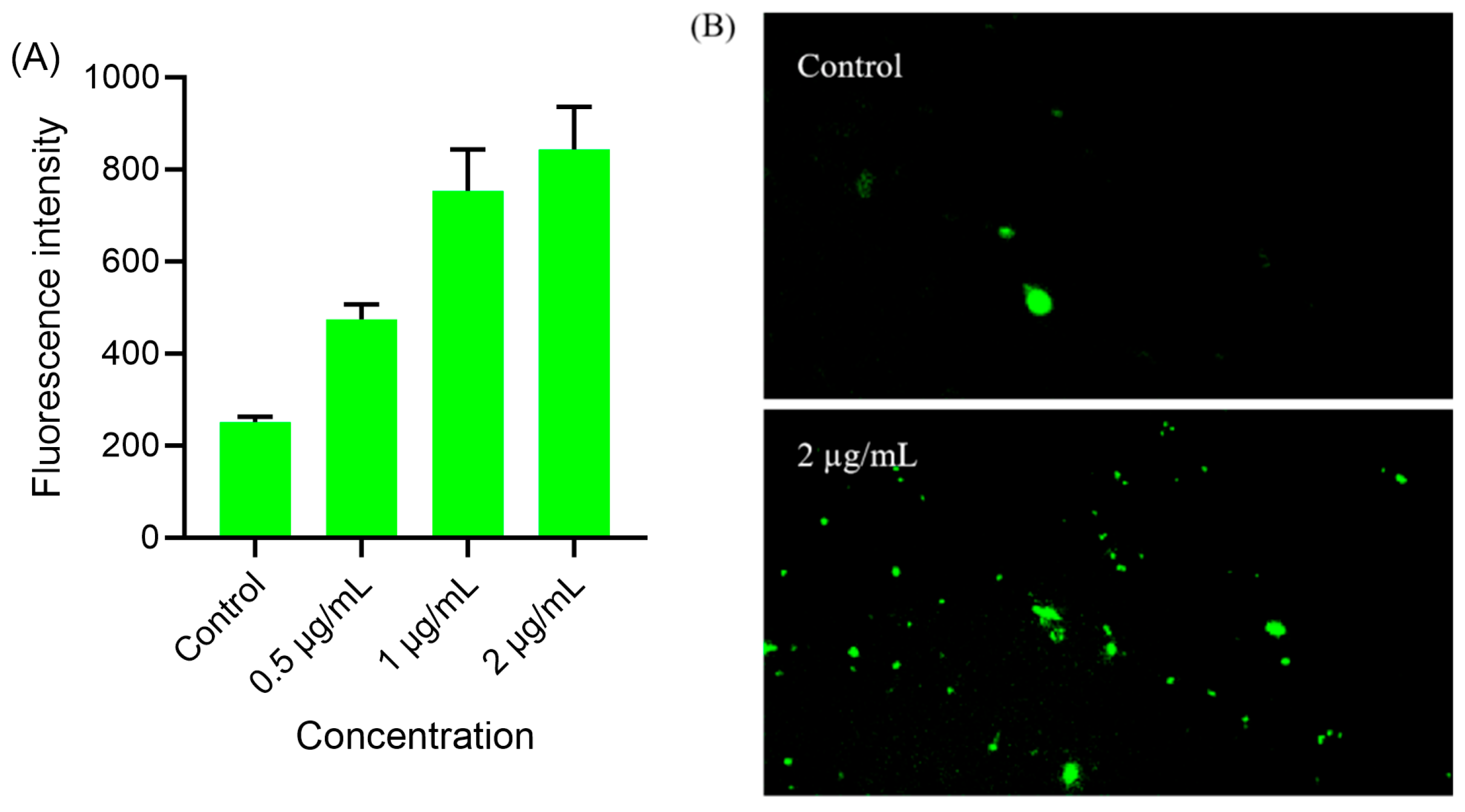

2.9. Intracellular ROS Level

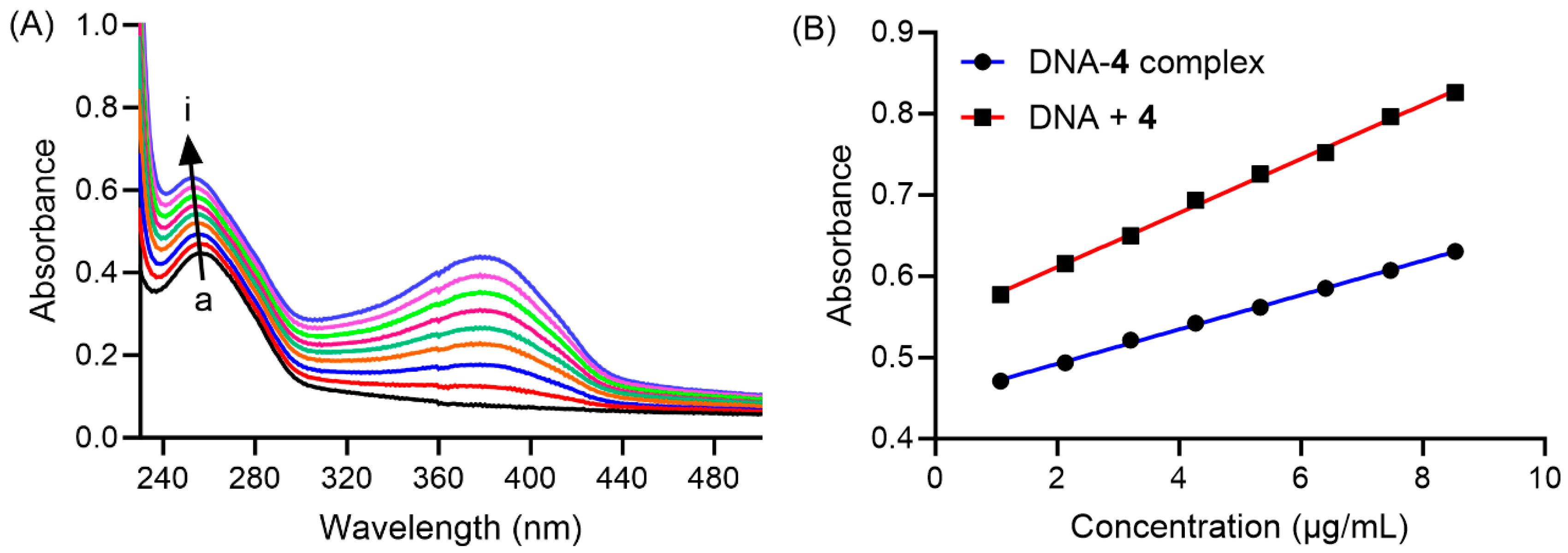

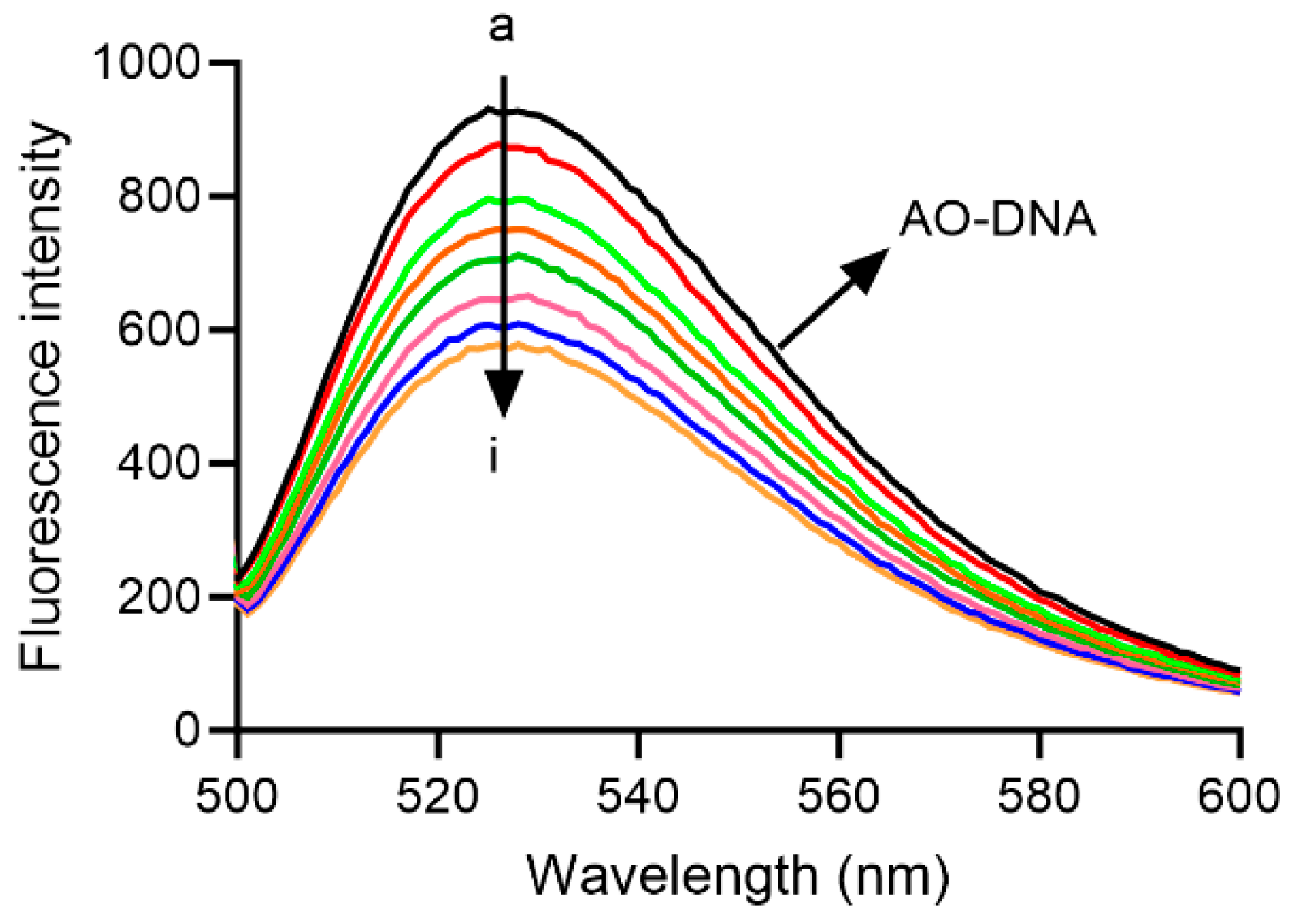

2.10. Interaction of Compound 4 with DNA

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. General Methods and Reagents

3.2. Biological Assays

3.2.1. Antibacterial Assay

3.2.2. Cytotoxicity and Hemolytic Activity

3.2.3. Proliferation Activity

3.2.4. Resistance Study

3.2.5. Drug Combination

3.2.6. Membrane-Disturbing Activity

3.2.7. Biofilm Inhibition and Eradication

3.2.8. Intracellular Oxidative Stress

3.2.9. Interaction with DNA

3.2.10. Molecular Docking

3.2.11. X-Ray Crystallography

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Li, X.Y.; Wu, Y.Y.; Jiang, T.; Chen, B.; Feng, R.; Zhang, J.; Xie, X.Y.; Ruan, Z. China’s plan to combat antimicrobial resistance. Science 2024, 383, 1424–1425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dance, A. Five ways science is tackling the antibiotic resistance crisis. Nature 2024, 632, 494–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.X.; Wang, J.; Mou, L.L.; Zhang, H.Z.; Chen, G.Y.; Zhou, C.H. Comprehensive insights into sulfanilamido-based medicinal design and research. Med. Res. Rev. 2025, 45, 1700–1817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holmes, C.L.; Albin, O.R.; Mobley, H.L.T.; Bachman, M.A. Bloodstream infections: Mechanisms of pathogenesis and opportunities for intervention. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2025, 23, 210–224. [Google Scholar]

- Turner, N.A.; Sharma-Kuinkel, B.K.; Maskarinec, S.A.; Eichenberger, E.M.; Shah, P.P.; Carugati, M.; Holland, T.L.; Fowler, V.G. Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus: An overview of basic and clinical research. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2019, 17, 203–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, A.; De Lencastre, H.; Garau, J.; Kluytmans, J.; Malhotra-Kumar, S.; Peschel, A.; Harbarth, S. Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers 2018, 4, 18033. [Google Scholar]

- Gehrmann, R.; Hertlein, T.; Hopke, E.; Ohlsen, K.; Lalk, M.; Hilgeroth, A. Novel small-molecule hybrid-antibacterial agents against S. aureus and MRSA strains. Molecules 2021, 27, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larsson, D.J.; Flach, C.F. Antibiotic resistance in the environment. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2022, 20, 257e69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huemer, M.; Mairpady, S.S.; Brugger, S.D.; Zinkernagel, A.S. Antibiotic resistance and persistence-implications for human health and treatment perspectives. EMBO Rep. 2020, 21, e51034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Endale, H.; Mathewos, M.; Abdeta, D. Potential causes of spread of antimicrobial resistance and preventive measures in one health perspective—A review. Infect. Drug Resist. 2023, 16, 7515–7545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.R.; Tan, Y.M.; Zhang, L.; Zhou, C.H. Comprehensive insights into medicinal research on imidazole-based supramolecular complexes. Pharmaceutics 2023, 15, 1348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Peng, X.M.; Duma, G.L.V.; Geng, R.X.; Zhou, C.H. Comprehensive review in current developments of imidazole-based medicinal chemistry. Med. Res. Rev. 2014, 34, 340–437. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Zarenezhad, E.; Behmard, E.; Karami, R.; Behrouz, S.; Marzi, M.; Ghasemian, A.; Rad, M.N.S. The antibacterial and anti-biofilm effects of novel synthetized nitroimidazole compounds against methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus and carbapenem-resistant Escherichia coli and Klebsiella pneumonia In Vitro and In Silico. BMC Chem. 2024, 18, 244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jarrad, A.M.; Ang, C.W.; Debnath, A.; Hahn, H.J.; Woods, K.; Tan, L.; Sykes, M.L.; Jones, A.J.; Pelingon, R.; Butler, M.S.; et al. Design, synthesis, and biological evaluation of 2 nitroimidazopyrazin-one/-es with antitubercular and antiparasitic activity. J. Med. Chem. 2018, 61, 11349–11371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nocentini, A.; Trallori, E.; Singh, S.; Lomelino, C.L.; Bartolucci, G.; Mannelli, L.D.C.; Ghelardini, C.; McKenna, R.; Gratteri, P.; Supuran, C.T. 4-Hydroxy-3-nitro-5-ureido-benzenesulfonamides selectively target the tumor-associated carbonic anhydrase isoforms IX and XII showing hypoxia-enhanced antiproliferative profiles. J. Med. Chem. 2018, 61, 10860–10874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Z.Z.; Maddili, S.K.; Tangadanchu, V.K.R.; Bheemanaboina, R.R.Y.; Lin, J.M.; Yang, R.G.; Cai, G.X.; Zhou, C.H. Researches and applications of nitroimidazole heterocycles in medicinal chemistry. Sci. Sin. Chim. 2019, 49, 230–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rocha-Garduño, G.; Hernández-Martínez, N.A.; Colín-Lozano, B.; Estrada-Soto, S.; Hernández-Núñez, E.; Prieto-Martínez, F.D.; Medina-Franco, J.L.; Chale-Dzul, J.B.; Moo-Puc, R.; Navarrete-Vázquez, G. Metronidazole and secnidazole carbamates: Synthesis, antiprotozoal activity, and molecular dynamics studies. Molecules 2020, 25, 793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nocentini, A.; Osman, S.M.; Rodrigues, I.A.; Cardoso, V.S.; Alasmary, F.A.S.; AlOthman, Z.; Supuran, C.T. Appraisal of anti-protozoan activity of nitroaromatic benzenesulfonamides inhibiting carbonic anhydrases from Trypanosoma cruzi and Leishmania donovani. J. Enzyme Inhib. Med. Chem. 2019, 34, 1164–1171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ang, C.W.; Jarrad, A.M.; Cooper, M.A.; Blaskovich, M.A.T. Nitroimidazoles: Molecular fireworks that combat a broad spectrum of infectious diseases. J. Med. Chem. 2017, 60, 7636–7657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, X.L.; Liu, F.; Deng, J.; Dai, P.P.; Qin, Y.; Li, Z.; Wang, B.B.; Fan, A.P.; Wang, Z.; Zhao, Y.J. Electron-accepting micelles deplete reduced nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate and impair two antioxidant cascades for ferroptosis-induced tumor eradication. ACS Nano 2020, 14, 14715–14730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nepali, K.; Lee, H.Y.; Liou, J.P. Nitro-group-containing drugs. J. Med. Chem. 2018, 62, 2851–2893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patel, O.P.S.; Jesumoroti, O.J.; Legoabe, L.J.; Beteck, R.M. Metronidazole-conjugates: A comprehensive review of recent developments towards synthesis and medicinal perspective. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2021, 210, 112994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Zhao, C.P.; Ma, H.P.; Zhao, M.Y.; Xue, Y.R.; Wang, X.M.; Zhu, H.L. Design, synthesis and antimicrobial activities evaluation of Schiff base derived from secnidazole derivatives as potential FabH inhibitors. Bioorg Med. Chem. 2013, 21, 3120–3126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Żwawiak, J.; Olender, D.; Zaprutko, L. Some Nitroimidazole Derivatives as Antibacterial and Antifungal Agents in In Vitro Study. J. Med. Sci. 2019, 1, 47–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alipour, E.; Emami, S.; Yahya-Meymandi, A.; Nakhjiri, M.; Johari, F.; Ardestani, S.K.; Foroumadi, A. Synthesis and antileishmanial activity of 5-(5-nitroaryl)-2-substituted-thio-1,3,4-thiadiazoles. J. Enzyme Inhib. Med. Chem. 2010, 26, 123–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, L.; Ishizaki, H.; Spitzer, M.; Taylor, K.L.; Temperley, N.D.; Johnson, S.L.; Brear, P.; Gautier, P.; Zeng, Z.; Mitchell, A.; et al. ALDH2 mediates 5-nitrofuran activity in multiple species. Cell Chem. Biol. 2012, 19, 883–892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.Z.; Tangadanchu, V.K.R.; Battini, N.; Bheemanaboina, R.R.Y.; Zang, Z.L.; Zhang, S.L.; Zhou, C.H. Indole-nitroimidazole conjugates as efficient manipulators to decrease the genes expression of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2019, 179, 723–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badshah, S.L.; Ullah, A. New developments in non-quinolone-based antibiotics for the inhibiton of bacterial gyrase and topoisomerase IV. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2018, 152, 393–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riveiro, M.E.; Kimpe, N.D.; Moglioni, A.; Vazquez, R.; Monczor, F.; Shayo, C.; Davio, C. Coumarins: Old compounds with novel promising therapeutic perspectives. Curr. Med. Chem. 2010, 17, 1325–1338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, P.T.; Lin, W.P.; Lee, A.R.; Hu, M.K. New 7-[4-(4-(un) substituted) piperazine-1-carbonyl]-piperazin-1-yl] derivatives of fluoroquinolone: Synthesis and antimicrobial evaluation. Molecules 2013, 18, 7557–7569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caruso, A.; Iacopetta, D.; Puoci, F.; Cappello, A.R.; Saturnino, C.; Sinicropi, M.S. Carbazole derivatives: A promising scenario for breast cancer treatment. Mini Rev. Med. Chem. 2016, 16, 630–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.X.; Zhang, P.L.; Gopala, L.; Lv, J.S.; Lin, J.M.; Zhou, C.H. A unique hybridization route to access hydrazylnaphthalimidols as novel structural scaffolds of multitargeting broad-spectrum antifungal candidates. J. Med. Chem. 2024, 67, 8932–8961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raman, N.; Pothiraj, K.; Baskaran, T. DNA-binding, oxidative DNA cleavage, and coordination mode of later 3d transition metal complexes of a Schiff base derived from isatin as antimicrobial agents. J. Coord. Chem. 2011, 64, 3900–3917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brum, J.D.C.; França, T.C.C.; Villar, J.D.F. Synthesis and Biological Activity of Hydrazones and Derivatives: A Review. Mini-Rev. Med. Chem. 2020, 20, 342–368. [Google Scholar]

- Barluenga, J.; Tomás-Gamasa, M.; Aznar, F.; Valdés, C. Metal-free carbon–carbon bond-forming reductive coupling between boronic acids and tosylhydrazones. Nat. Chem. 2009, 1, 494–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dhanaraj, C.J.; Johnson, J. DNA interaction, antioxidant and in vitro cytotoxic activities of some mononuclear metal(II) complexes of a bishydrazone ligand. Mat. Sci. Eng. C-Mater. 2017, 78, 1006–1015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.Y.; Tang, Z.B.; Liu, Z.C. Recent advances in the synthesis and applications of furocoumarin derivatives. Chin. Chem. Lett. 2023, 34, 108396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, K.; Choudhary, M.I.; Saleem, R.S.Z. Heterocyclic pyrimidine derivatives as promising antibacterial agents. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2023, 259, 115701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- More, K.N.; Lee, J.H. Synthesis of (3-(2-Aminopyrimidin-4-yl)-4-hydroxyphenyl)phenyl Methanone Analogues as Inhibitors of Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor Receptor-2 Kinase. Bull. Korean Chem. Soc. 2017, 38, 70–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Z.G.; Dai, A.; Jin, Z.C.; Chi, Y.G.R.; Wu, J. Trifluoromethylpyridine: An important active fragment for the discovery of new pesticides. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2022, 70, 11019–11030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, R.; Chaudhary, S.; Kumar, K.; Gupta, M.K.; Rawal, R.K. Recent synthetic and medicinal perspectives of dihydropyrimidinones: A review. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2017, 132, 108–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Kilby, P.; Frankcombe, T.J.; Schmidt, T.W. The electronic structure of benzene from a tiling of the correlated 126-dimensional wavefunction. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 1210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kadyan, K.; Singh, R.; Sindhu, J.; Kumar, P.; Devi, M.; Lal, S.; Kumar, A.; Singh, D.; Kumar, H. Exploring the structural versatility and dynamic behavior of acyl/aroyl hydrazones: A comprehensive review. Top. Curr. Chem. 2025, 383, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shakir, A.J.; Madalan, A.M.; Ionita, G.; Lupu, S.; Lete, C.; Ionita, P.A. Comparison between nitroxide and hydrazyl free radicals in selective alcohols oxidation. Chem. Phys. 2017, 490, 7–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazumder, R.; Ichudaule, A.G.; Rajat, G.S.D. Significance of chalcone scaffolds in medicinal chemistry. Top. Curr. Chem. 2024, 382, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tok, F.; Sağlık, B.N.; Özkay, Y.; Ilgın, S.; Kaplancıklı, Z.A.; Koçyiğit-Kaymakçıoğlu, B. Synthesis of new hydrazone derivatives and evaluation of their monoamine oxidase inhibitory activity. Bioorg Chem. 2021, 114, 105038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Guo, S.X.; Yu, L.J.; Zhang, W.; Wang, Z.H.; Chi, Y.G.B.; Wu, J. Hydrazone derivatives in agrochemical discovery and development. Chin. Chem. Lett. 2024, 35, 108207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.P.; Battini, N.; Ansari, M.F.; Zhou, C.H. Membrane active 7-thiazoxime quinolones as novel DNA binding agents to decrease the genes expression and exert potent anti-methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus activity. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2021, 217, 113340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Hamon, J.R. Recent Developments in Penta-, Hexa-, and Heptadentate Schiff Base Ligands and Their Metal Complexes. Coordin Chem. Rev. 2019, 389, 94–118. [Google Scholar]

- Marino, A.; Blanco, A.R.; Ginestra, G.; Nostro, A.; Bisignano, G. Ex vivo efficacy of gemifloxacin in experimental keratitis induced by methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 2016, 48, 395–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, L.; Li, J.; Yu, M.M.; Jia, W.B.; Duan, S.; Cao, D.P.; Ding, X.K.; Yu, B.G.; Zhang, X.R.; Xu, F.J. Molecular sizes and antibacterial performance relationships of flexible ionic liquid derivatives. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2020, 142, 20257–20269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, M.M.; Fang, Y.; Chen, Y.C.; Lei, Y.Q.; Fang, L.F.; Zhu, B.K.; Matsuyama, H. Antifouling and antibacterial behavior of membranes containing quaternary ammonium and zwitterionic polymers. J. Colloid. Interface Sci. 2021, 584, 225–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sowmiah, S.; Esperança, J.M.S.S.; Rebelo, L.P.N.; Afonso, C.A.M. Pyridinium salts: From synthesis to reactivity and applications. Org. Chem. Front. 2018, 5, 453–493. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J.; Ansari, M.F.; Zhou, C.H. Identification of unique quinazolone thiazoles as novel structural scaffolds for potential Gram-negative bacterial conquerors. J. Med. Chem. 2021, 64, 7630–7645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.D.; Chen, Q.; Xie, J.Y.; Cong, Z.H.; Cao, C.T.; Zhang, W.J.; Zhang, D.H.; Chen, S.; Gu, J.W.; Deng, S.; et al. Switching from membrane disrupting to membrane crossing, an effective strategy in designing antibacterial polypeptide. Sci. Adv. 2023, 9, eabn0771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, S.R.; Yu, J.C.; Cheng, Y.; Zhou, C.H. Discovery of benzopyronyl imidazolidinediones as new structural skeleton of potential multitargeting antibacterial agents. Bioorg Chem. 2025, 26, 108923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aleksandrova, E.V.; Ma, C.X.; Klepacki, D.; Alizadeh, F.; Vázquez-Laslop, N.; Liang, J.H.; Polikanov, Y.S.; Mankin, A.S. Macrolones target bacterial ribosomes and DNA gyrase and can evade resistance mechanisms. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2024, 20, 1680–1690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, H.; Huang, S.Y.; Jeyakkumar, P.; Cai, G.X.; Fang, B.; Zhou, C.H. Natural berberine-derived azolyl ethanols as new structural antibacterial agents against drug-resistant Escherichia coli. J. Med. Chem. 2022, 65, 436–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mix, A.K.; Nguyen, T.H.N.; Schuhmacher, T.; Szamosvári, D.; Muenzner, P.; Haas, P.; Heeb, L.; Wami, H.T.; Dobrindt, U.; Delikkafa, Y.Ö.; et al. A quinolone N-oxide antibiotic selectively targets Neisseria gonorrhoeae via its toxin-antitoxin system. Nat. Microbiol. 2025, 10, 939–957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, S.A.; Fayed, E.A.; Rizk, H.F.; Desouky, S.E.; Raga, A. Hydrazonoyl bromide precursors as DHFR inhibitors for the synthesis of bis-thiazolyl pyrazole derivatives; antimicrobial activities, antibiofilm, and drug combination studies against MRSA. Bioorg Chem. 2021, 116, 105339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, P.; Li, Y.; Guo, T.; Liu, S.M.; Tancer, R.J.; Hu, C.H.; Zhao, C.Z.; Xue, C.Y.; Liao, G.J. New antifungal strategies: Drug combination and co-delivery. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2023, 198, 114874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, C.L.; Zhou, Y.; Zheng, Y.Q.; Yu, Y.; Yang, K.L.; Chen, Z.Y.; Chen, X.H.; Wen, K.; Chen, Y.J.; Bai, S.L.; et al. Amphiphilic nano-swords for direct penetration and eradication of pathogenic bacterial biofilms. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2023, 15, 20458–20473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, Y.M.; Wang, Y.; Li, S.; Zhang, S.L.; Zhou, C.H. Azolylpyrimidinediols as novel structural scaffolds of DNA-groove binders against intractable Acinetobacter baumannii. J. Med. Chem. 2023, 66, 4910–4931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sauer, K.; Stoodley, P.; Goeres, D.M.; Hall-Stoodley, L.; Burmølle, M.; Stewart, P.S.; Bjarnsholt, T. The biofilm life cycle: Expanding the conceptual model of biofilm formation. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2022, 20, 608–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, S.L.; Wang, J.X.; Yang, K.L.; Zhou, C.L.; Xu, Y.F.; Song, J.F.; Gu, Y.X.; Chen, Z.; Wang, M.; Shoen, C.; et al. A polymeric approach toward resistance-resistant antimicrobial agent with dual-selective mechanisms of action. Sci. Adv. 2021, 7, eabc9917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xia, J.; Xin, L.; Li, J.Y.; Tian, L.; Wu, K.X.; Zhang, S.J.; Yan, W.J.; Li, H.; Zhao, Q.Q.; Liang, C.Y. Discovery of quaternized pyridine-thiazole-pleuromutilin derivatives with broad-spectrum antibacterial and potent anti-MRSA activity. J. Med. Chem. 2023, 66, 5061–5078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, S.R.; Zeng, C.M.; Huang, S.Y.; Ahmad, N.; Peng, X.M.; Meng, J.P.; Zhou, C.H. Heteroarylcyanovinyl benzimidazoles as new antibacterial skeleton with large potential to combat bacterial infections. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2025, 73, 13985–13997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, M.; Wang, S.; Wang, T.; Hu, S.S.; Bhayana, B.; Ishii, M.; Kong, Y.F.; Cai, Y.C.; Dai, T.H.; Cui, W.G.; et al. Bacteria-specific phototoxic reactions triggered by blue light and phytochemical carvacrol. Sci. Transl. Med. 2021, 13, eaba3571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, W.; Ning, Z.; Ma, L.; Yin, X.; Wei, Q.; Yuan, E.; Yang, J.; Ren, J. Recrystallization of dihydromyricetin from Ampelopsis grossedentata and its anti-oxidant activity evaluation. Rejuvenation Res. 2014, 17, 422–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dwyer, D.J.; Belenky, P.A.; Yang, J.H.; MacDonald, I.C.; Martell, J.D.; Takahashi, N.; Chan, C.T.Y.; Lobritz, M.A.; Braff, D.; Schwarz, E.G.; et al. Antibiotics induce redox-related physiological alterations as part of their lethality. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2014, 111, E2100–E2109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Liu, Y.Q.; Xue, C.C.; Hu, Y.; Zhao, Y.Y.; Cai, K.Y.; Li, M.H.; Luo, Z. A protein-based cGAS-STING nanoagonist enhances T cell-mediated anti-tumor immune responses. Nat Commun. 2022, 13, 5685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabharwal, S.; Schumacker, P. Mitochondrial ROS in cancer: Initiators, amplifiers or an Achilles’ heel? Nat. Rev. Cancer 2014, 14, 709–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, M.; Pu, H.S.; Xu, Y.F.; Wu, C.X.; Gu, Y.X.; Cai, Q.Y.; Yin, G.X.; Yin, P.; Zhang, C.H.; Wong, W.L.; et al. Chemical biology investigation of a triple-action, smart-decomposition antimicrobial booster based-combination therapy against “ESKAPE” pathogens. Sci. China Chem. 2024, 67, 3071–3082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, Y.M.; Zhang, J.; Wei, Y.J.; Hu, Y.G.; Li, S.R.; Zhang, S.L.; Zhou, C.H. Cyanomethylquinolones as a new class of potential multitargeting broad-spectrum antibacterial agents. J. Med. Chem. 2024, 67, 9028–9053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xie, J.X.; Wang, L.J.; Zhang, X.Y.; Li, Y.Y.; Liao, X.; Yang, C.X.; Tang, R.Y. Discovery of new anti-MRSA agents based on phenoxyethanol and its mechanism. ACS Infect. Dis. 2022, 8, 2291–2306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banti, C.N.; Papatriantafyllopoulou, C.; Papachristodoulou, C.; Hatzidimitriou, A.G.; Hadjikakou, S.K. New apoptosis inducers containing anti-inflammatory drugs and pnictogen derivatives: A new strategy in the development of mitochondrial targeting chemotherapeutics. J. Med. Chem. 2023, 66, 4131–4149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neidle, S. DNA minor-groove recognition by small molecules. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2001, 18, 291–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, D.N. Ribosome-targeting antibiotics and mechanisms of bacterial resistance. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2014, 12, 35–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guha, S.; Ghimire, J.; Wu, E.; Wimley, W.C. Mechanistic landscape of membrane-permeabilizing peptides. Chem. Rev. 2019, 119, 6040–6085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shukla, R.; Medeiros-Silva, J.; Parmar, A.; Vermeulen, B.J.A.; Das, S.; Paioni, A.L.; Jekhmane, S.; Lorent, J.; Bonvin, A.M.J.J.; Baldus, M.; et al. Mode of action of teixobactins in cellular membranes. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 2457–2848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Bacteria | Norfloxacin | Oxacillin Sodium Monohydrate | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| FICI | Effect | FICI | Effect | |

| MRSA | 0.50 | Synergism | 0.25 | Synergism |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Li, Z.-Z.; Zhou, C.-H.; Liu, Y.-J. Heteroaryl Bishydrazono Nitroimidazoles: A Unique Structural Skeleton with Potent Multitargeting Antibacterial Activity. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 11836. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262411836

Li Z-Z, Zhou C-H, Liu Y-J. Heteroaryl Bishydrazono Nitroimidazoles: A Unique Structural Skeleton with Potent Multitargeting Antibacterial Activity. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2025; 26(24):11836. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262411836

Chicago/Turabian StyleLi, Zhen-Zhen, Cheng-He Zhou, and Yi-Jin Liu. 2025. "Heteroaryl Bishydrazono Nitroimidazoles: A Unique Structural Skeleton with Potent Multitargeting Antibacterial Activity" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 26, no. 24: 11836. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262411836

APA StyleLi, Z.-Z., Zhou, C.-H., & Liu, Y.-J. (2025). Heteroaryl Bishydrazono Nitroimidazoles: A Unique Structural Skeleton with Potent Multitargeting Antibacterial Activity. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 26(24), 11836. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262411836