Grief-Related Psychopathology from Complicated Grief to DSM-5-TR Prolonged Grief Disorder: A Systematic Review of Biochemical Findings

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Literature Search

2.2. Eligibility and Exclusion Criteria

- Human studies.

- Studies assessing grief reactions by means of validated psychometric scales.

- Studies that investigated biomarkers associated with bereavement in any kind of biological matrices, plasma, serum, saliva, blood cells and urine to ensure selection of a wider data collection.

- Articles available in the English language.

- Articles presenting data derived from animal models.

- Preprints and publications in the form of abstracts, reviews and editorials.

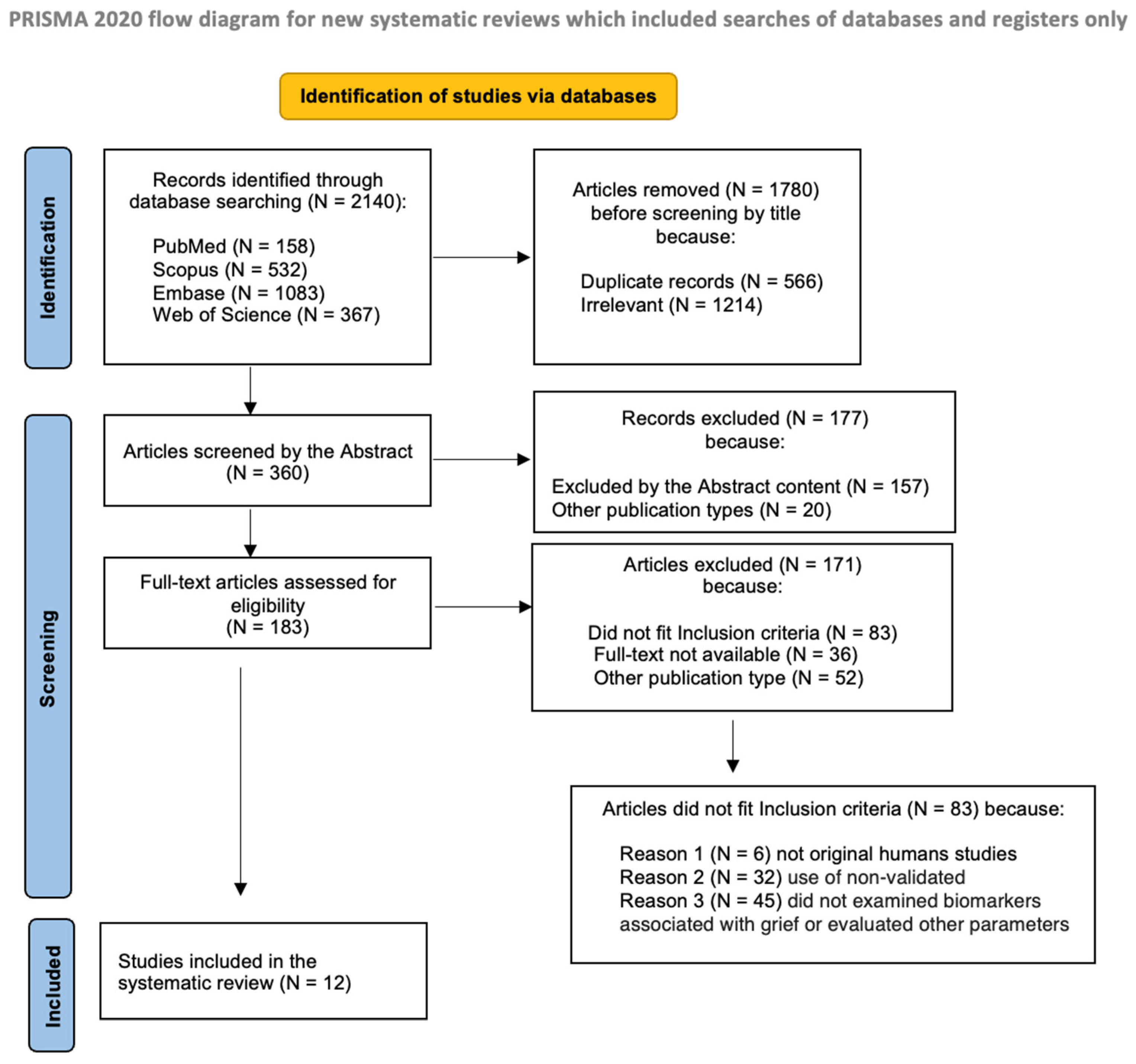

2.3. Screening and Selection Process

2.4. Quality Assessment

3. Results

3.1. Study Characteristics

3.2. Sample Characteristics

3.3. Assessments

3.3.1. Grief Assessment

3.3.2. Psychiatric Comorbidity

3.4. Biomarkers

3.4.1. Biological Matrices

3.4.2. HPA Axis: Cortisol

3.4.3. Catecholamines

3.4.4. Oxytocin

3.4.5. Endocannabinoid System

3.4.6. Immunity/Inflammatory Factors

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, DSM-5-TR; American Psychiatric Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Maercker, A.; Lalor, J. Diagnostic and clinical considerations in prolonged grief disorder. Dialogues J. Clin. Neurosci. 2012, 14, 167–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prigerson, H.G.; Horowitz, M.J.; Jacobs, S.C.; Parkes, C.M.; Aslan, M.; Goodkin, K.; Maciejewski, P.K. Prolonged grief disorder: Psychometric validation of criteria proposed for DSM-V and ICD-11. PLoS Med. 2009, 6, e1000121, Correction in PLoS Med. 2013, 10. https://doi.org/10.1371/annotation/a1d91e0d-981f-4674-926c-0fbd2463b5ea. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simon, N.M. Treating complicated grief. JAMA 2013, 310, 416–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shear, M.K.; Simon, N.; Wall, M.; Zisook, S.; Neimeyer, R.; Duan, N.; Reynolds, C.; Lebowitz, B.; Sung, S.; Ghesquiere, A.; et al. Complicated grief and related bereavement issues for DSM-5. Depress. Anxiety 2011, 28, 103–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horowitz, M.J.; Siegel, B.; Holen, A.; Bonanno, G.A.; Milbrath, C.; Stinson, C.H. Diagnostic criteria for complicated grief disorder. Am. J. Psychiatry 1997, 154, 904–910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simon, N.M.; Shear, M.K. Prolonged Grief Disorder. N. Engl. J. Med. 2024, 391, 1227–1236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th ed; American Psychiatric Association: Arlington, VA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Boelen, P.A.; van de Schoot, R.; van den Hout, M.A.; de Keijser, J.; van den Bout, J. Prolonged Grief Disorder, depression, and posttraumatic stress disorder are distinguishable syndromes. J. Affect. Disord. 2010, 125, 374–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Szuhany, K.L.; Malgaroli, M.; Miron, C.D.; Simon, N.M. Prolonged Grief Disorder: Course, Diagnosis, Assessment, and Treatment. Focus 2021, 19, 161–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carmassi, C.; Shear, M.K.; Socci, C.; Corsi, M.; Dell’Osso, L.; First, M.B. Complicated grief and manic comorbidity in the aftermath of the loss of a son. J. Psychiatr. Pract. 2013, 19, 419–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lundorff, M.; Holmgren, H.; Zachariae, R.; Farver-Vestergaard, I.; O’Connor, M. Prevalence of prolonged grief disorder in adult bereavement: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Affect. Disord. 2017, 212, 138–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosner, R.; Comtesse, H.; Vogel, A.; Doering, B.K. Prevalence of prolonged grief disorder. J. Affect. Disord. 2021, 287, 301–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Djelantik, A.A.A.M.J.; Smid, G.E.; Mroz, A.; Kleber, R.J.; Boelen, P.A. The prevalence of prolonged grief disorder in bereaved individuals following unnatural losses: Systematic review and meta regression analysis. J. Affect. Disord. 2020, 265, 146–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Comtesse, H.; Smid, G.E.; Rummel, A.M.; Spreeuwenberg, P.; Lundorff, M.; Dückers, M.L.A. Cross-national analysis of the prevalence of prolonged grief disorder. J. Affect. Disord. 2024, 350, 359–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Békés, V.; Roberts, K.; Németh, D. Competitive neurocognitive processes following bereavement. Brain Res. Bull. 2023, 199, 110663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arizmendi, B.; Kaszniak, A.W.; O’Connor, M.F. Disrupted prefrontal activity during emotion processing in complicated grief: An fMRI investigation. Neuroimage 2016, 124 Pt A, 968–976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Michel, C.A.; Mann, J.J.; Schneck, N. Neural correlates of deceased-related attention during acute grief in suicide-related bereavement. J. Affect. Disord. 2024, 347, 285–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kakarala, S.E.; Roberts, K.E.; Rogers, M.; Coats, T.; Falzarano, F.; Gang, J.; Chilov, M.; Avery, J.; Maciejeski, P.K.; Lichtenthal, W.G.; et al. The neurobiological reward system in Prolonged Grief Disorder (PGD): A systematic review. Psychiatry Res. Neuroimaging 2020, 303, 111135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, R.G.; Florio, E.; Punzo, D.; Borrelli, E. The Brain’s Reward System in Health and Disease. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2021, 1344, 57–69. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Bluett, R.J.; Báldi, R.; Haymer, A.; Gaulden, A.D.; Hartley, N.D.; Parrish, W.P.; Baechle, J.; Marcus, D.J.; Mardam-Bey, R.; Shonesy, B.C.; et al. Endocannabinoid signalling modulates susceptibility to traumatic stress exposure. Nat. Commun. 2017, 8, 14782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volkow, N.D.; Hampson, A.J.; Baler, R.D. Don’t worry, be happy: Endocannabinoids and cannabis at the intersection of stress and reward. Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 2017, 57, 285–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheele, D.; Wille, A.; Kendrick, K.M.; Stoffel-Wagner, B.; Becker, B.; Güntürkün, O.; Maier, W.; Hurlemann, R. Oxytocin enhances brain reward system responses in men viewing the face of their female partner. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2013, 110, 20308–20313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thurston, M.D.; Ericksen, L.C.; Jacobson, M.M.; Bustamante, A.; Koppelmans, V.; Mickey, B.J.; Love, T.M. Oxytocin differentially modulates reward system responses to social and non-social incentives. Psychopharmacology 2025, 242, 449–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pohl, T.T.; Young, L.J.; Bosch, O.J. Lost connections: Oxytocin and the neural, physiological, and behavioral consequences of disrupted relationships. Int. J. Psychophysiol. 2019, 136, 54–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fagundes, C.P.; Wu, E.L. Matters of the Heart: Grief, Morbidity, and Mortality. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 2020, 29, 235–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McEwen, B.S. Stress, adaptation, and disease: Allostasis and allostatic load. In Molecular Aspects, Integrative Systems, and Clinical Advances; McCann, S.M., Lipton., J.M., Sternberg, E.M., Chrousos., G.P., Gold, P.W., Smith, C.C., Eds.; The New York Academy of Sciences: New York, NY, USA, 1998; pp. 33–44. [Google Scholar]

- McEwen, B.S. Stressed or stressed out: What is the difference? J. Psychiatry Neurosci. 2005, 30, 315–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leonard, B.E. The HPA and immune axes in stress: The involvement of the serotonergic system. Eur. Psychiatry 2005, 20 (Suppl. S3), S302–S306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palego, L.; Giannaccini, G.; Betti, L. Neuroendocrine Response to Psychosocial Stressors, Inflammation Mediators and Brain-periphery Pathways of Adaptation. Cent. Nerv. Syst. Agents Med. Chem. 2021, 21, 2–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juster, R.P.; Misiak, B. Advancing the allostatic load model: From theory to therapy. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2023, 154, 106289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alotiby, A. Immunology of Stress: A Review Article. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 6394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruces, J.; Venero, C.; Pereda-Pérez, I.; De la Fuente, M. The effect of psychological stress and social isolation on neuroimmunoendocrine communication. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2014, 20, 4608–4628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hopf, D.; Eckstein, M.; Aguilar-Raab, C.; Warth, M.; Ditzen, B. Neuroendocrine mechanisms of grief and bereavement: A systematic review and implications for future interventions. J. Neuroendocrinol. 2020, 32, e12887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adam, E.K.; Quinn, M.E.; Tavernier, R.; McQuillan, M.T.; Dahlke, K.A.; Gilbert, K.E. Diurnal cortisol slopes and mental and physical health outcomes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2017, 83, 25–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seiler, A.; von Känel, R.; Slavich, G.M. The Psychobiology of bereavement and health: A conceptual review from the perspective of social signal transduction theory of depression. Front. Psychiatry 2020, 11, 565239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dietz, L.J.; Stoyak, S.; Melhem, N.; Porta, G.; Matthews, K.A.; Walker Payne, M.; Brent, D.A. Cortisol response to social stress in parentally bereaved youth. Biol. Psychiatry 2013, 73, 379–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobs, S.C.; Mason, J.W.; Kosten, T.R.; Wahby, V.; Kasl, S.V.; Ostfeld, A.M. Bereavement and catecholamines. J. Psychosom. Res. 1986, 30, 489–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vitlic, A.; Khanfer, R.; Lord, J.M.; Carroll, D.; Phillips, A.C. Bereavement reduces neutrophil oxidative burst only in older adults: Role of the HPA axis and immunesenescence. Immun. Ageing 2014, 11, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baik, J.H. Stress and the dopaminergic reward system. Exp. Mol. Med. 2020, 52, 1879–1890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neumann, I.D. Involvement of the brain oxytocin system in stress coping: Interactions with the hypothalamo-pituitary-adrenal axis. Prog. Brain Res. 2002, 139, 147–162. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, Z.V.; Young, L.J. Neurobiological mechanisms of social attachment and pair bonding. Curr. Opin. Behav. Sci. 2015, 3, 38–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerra, G.; Monti, D.; Panerai, A.E.; Sacerdote, P.; Anderlini, R.; Avanzini, P.; Zaimovic, A.; Brambilla, F.; Franceschi, C. Long-term immune-endocrine effects of bereavement: Relationships with anxiety levels and mood. Psychiatry Res. 2003, 121, 145–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. Br. Med. J. 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murad, M.H.; Sultan, S.; Haffar, S.; Bazerbachi, F. Methodological quality and synthesis of case series and case reports. BMJ Evid. Based Med. 2018, 23, 60–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Connor, M.F.; Wellisch, D.K.; Stanton, A.L.; Olmstead, R.; Irwin, M.R. Diurnal cortisol in Complicated and Non-Complicated Grief: Slope differences across the day. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2012, 37, 725–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Connor, M.-F.; Shear, M.K.; Fox, R.; Skritskaya, N.; Campbell, B.; Ghesquiere, A.; Glickman, K. Catecholamine predictors of complicated grief treatment outcomes. Int. J. Psychophysiol. 2013, 88, 349–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Kaplow, J.B.; Shapiro, D.N.; Wardecker, B.M.; Howell, K.H.; Abelson, J.L.; Worthman, C.M.; Prossin, A.R. Psychological and environmental correlates of HPA axis functioning in parentally bereaved children: Preliminary findings. J. Trauma. Stress 2013, 26, 233–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holland, J.M.; Rozalski, V.; Thompson, K.L.; Tiongson, R.J.; Schatzberg, A.F.; O’Hara, R.; Gallagher-Thompson, D. The unique impact of late-life bereavement and prolonged grief on diurnal cortisol. J. Gerontol. Ser. B Psychol. Sci. Soc. Sci. 2014, 69, 4–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, J.M.; Mason, T.M.; Buck, H.G.; Tofthagen, C.S.; Duffy, A.R.; Groër, M.W.; McHale, J.P.; Kip, K.E. Challenges in Obtaining and Assessing Salivary Cortisol and α-Amylase in an Over 60 Population Undergoing Psychotherapeutic Treatment for Complicated Grief: Lessons Learned. Clin. Nurs. Res. 2021, 30, 680–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pettingale, K.W.; Watson, M.; Tee, D.E.H.; Inayat, Q.; Alhaq, A. Pathological grief, psychiatric symptoms and immune status following conjugal bereavement. Stress Med. 1989, 5, 77–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schultze-Florey, C.R.; Martínez-Maza, O.; Magpantay, L.; Breen, E.C.; Irwin, M.R.; Gündel, H.; O’Connor, M.F. When grief makes you sick: Bereavement induced systemic inflammation is a question of genotype. Brain Behav. Immun. 2012, 26, 1066–1071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fagundes, C.P.; Brown, R.L.; Chen, M.A.; Murdock, K.W.; Saucedo, L.; LeRoy, A.; Wu, E.L.; Garcini, L.M.; Shahane, A.D.; Baameur, F.; et al. Grief, depressive symptoms, and inflammation in the spousally bereaved. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2019, 100, 190–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bui, E.; Hellberg, S.N.; Hoeppner, S.S.; Rosencrans, P.; Young, A.; Ross, R.A.; Hoge, E.; Simon, N.M. Circulating levels of oxytocin may be elevated in complicated grief: A pilot study. Eur. J. Psychotraumatol. 2019, 10, 1646603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harfmann, E.J.; McAuliffe, T.L.; Larson, E.R.; Claesges, S.A.; Sauber, G.; Hillard, C.J.; Goveas, J.S. Circulating endocannabinoid concentrations in grieving adults. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2020, 120, 104801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, M.; Bohorquez-Montoya, L.; McAuliffe, T.; Claesges, S.A.; Blair, N.O.; Sauber, G.; Reynolds, C.F., 3rd; Hillard, C.J.; Goveas, J.S. Loneliness, Circulating Endocannabinoid Concentrations, and Grief Trajectories in Bereaved Older Adults: A Longitudinal Study. Front. Psychiatry 2021, 12, 783187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, R.L.; LeRoy, A.S.; Chen, M.A.; Suchting, R.; Jaremka, L.M.; Liu, J.; Heijnen, C.; Fagundes, C.P. Grief Symptoms Promote Inflammation During Acute Stress Among Bereaved Spouses. Psychol. Sci. 2022, 33, 859–873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prigerson, H.G.; Maciejewski, P.K.; Reynolds, C.F., 3rd; Bierhals, A.J.; Newsom, J.T.; Fasiczka, A.; Frank, E.; Doman, J.; Miller, M. Inventory of Complicated Grief: A scale to measure maladaptive symptoms of loss. Psychiatry Res. 1995, 59, 65–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carmassi, C.; Shear, M.K.; Massimetti, G.; Wall, M.; Mauro, C.; Gemignani, S.; Conversano, C.; Dell’Osso, L. Validation of the Italian version Inventory of Complicated Grief (ICG): A study comparing CG patients versus bipolar disorder, PTSD and healthy controls. Compr. Psychiatry 2014, 55, 1322–1329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanders, C.M.; Mauger, P.A.; Strong, P.N., Jr. A Manual for the Grief Experience Inventory; Loss and Bereavement Resource Center, University of South Florida: Tampa, FL, USA, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Bui, E.; Mauro, C.; Robinaugh, D.J.; Skritskaya, N.A.; Wang, Y.; Gribbin, C.; Ghesquiere, A.; Horenstein, A.; Duan, N.; Reynolds, C.; et al. The Structured Clinical Interview for Complicated Grief: Reliability, Validity, and Exploratory Factor Analysis. Depress. Anxiety 2015, 32, 485–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melhem, N.M.; Porta, G.; Walker Payne, M.; Brent, D.A. Identifying prolonged grief reactions in children: Dimensional and diagnostic approaches. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2013, 52, 599–607.e7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engel, S.; Laufer, S.; Klusmann, H.; Schulze, L.; Schumacher, S.; Knaevelsrud, C. Cortisol response to traumatic stress to predict PTSD symptom development—A systematic review and meta-analysis of experimental studies. Eur. J. Psychotraumatol. 2023, 14, 2225153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Gutiérrez, M.S.; Navarrete, F.; Sala, F.; Gasparyan, A.; Austrich-Olivares, A.; Manzanares, J. Biomarkers in Psychiatry: Concept, Definition, Types and Relevance to the Clinical Reality. Front. Psychiatry 2020, 11, 432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stolfi, F.; Abreu, H.; Sinella, R.; Nembrini, S.; Centonze, S.; Landra, V.; Brasso, C.; Cappellano, G.; Rocca, P.; Chiocchetti, A. Omics approaches open new horizons in major depressive disorder: From biomarkers to precision medicine. Front. Psychiatry 2024, 15, 1422939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- An, M.; Gao, Y. Urinary Biomarkers of Brain Diseases. Genom. Proteom. Bioinform. 2015, 13, 345–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Study | Year | Country | Quality Rating | Type of Study | Sample Characteristics | Grief Assessment | Measured Markers | Biological Sample | Main Findings | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Grief Types/Groups | Loss Relation | Time Since Loss | N/n per Group | Age (Years, Mean/Range or SD) | |||||||||

| O’Connor et al. [46] | 2012 | USA | Good | Case-control study | Bereaved women; CG vs. Non-CG | Mother; sister (death to breast cancer) | Up to 5 years post-loss | N = 24, women CG N = 12 Non-CG N = 12 | CG = 42.67 (10.54) Non-CG = 46.91 (9.32) | ICG | Cortisol | Salivary (at waking, 45 min post-waking, 4 PM and 9 PM on three consecutive days) | Lower cortisol levels at 45 min post-waking, and higher cortisol levels at 4 PM in CG group vs. Non-CG group—flatter diurnal cortisol rhythms associated with CG. |

| O’Connor et al. [47] | 2013 | USA | Good | Randomized clinical trial | Bereaved adult individuals | Parent (44%), spouse (31%), child (6%), sibling (13%), other (e.g., close friend, 6%) | Widely variable: mean 87 months (SD = 123.9), median 38 months | N = 16; females N = 14 (87.5%); males N = 2 (12.5%) | 64 (SD = 4.3) | ICG (at study intake—up to 4 weeks before the first therapy session- and at week 20, following the termination of treatment | Catecholamines (norepinephrine, epinephrine, dopamine) | Plasma | Pre-treatment epinephrine levels were predictive of post-treatment ICG scores, taking into account the pre-treatment ICG score, whereas pre-treatment levels of other catecholamines were not. Age was not a significant predictor within the model. When each catecholamine level was used to predict grief symptom levels at post-treatment only, none of the catecholamine levels were able to predict ICG nor BDI-II scores, taking into account pre-treatment BDI-II results. |

| Kaplow et al. [48] | 2013 | USA | Good | Randomized clinical trial | Parentally bereaved children (recent parental loss) and their surviving caregivers | Parent | Previous 6 months | N = 66; children N = 38 (20 girls); their surviving caregivers N = 28 (23 women) | Children: 9.6 (SD = 2.04); surviving caregivers: 42.76 (SD = 8.33) | ICG-R in children; PG-13 in surviving caregivers | Cortisol in Awakening Response (CAR) | Salivary (at waking and 30 min post-waking, on three consecutive days) | Significant correlation between attenuation of first-day CAR and increased symptoms of anxiety, depression, post-traumatic stress and avoidant coping strategies. Higher levels of maladaptive grief were associated with attenuation of first-day CAR. |

| Holland et al. [49] | 2020 | USA | Fair | Case-control study | Older adults: depressed non-bereaved individuals (Group 1); depressed bereaved individuals without elevated PGD symptoms (Group 2); depressed bereaved individuals with elevated PGD symptoms (Group 3) | Spouse or partner (33%); parent (16.7%); sibling (12.5%), friend (12.5%): child (4.2%). Most of deaths were due to natural causes (87.5%) | On average 3.1 years | N = 56; Group 1 N = 32; Group 2 N = 15; Group 3 N = 9; females N = 34 (60.7%); males N = 22 (39.3%) | 69.9 (SD = 7.6); Group 1 70.4 (SD = 7.5); Group 2 69.4 (SD = 7.5); Group 3 68 SD = 7.3) | PG-13 | Cortisol | Salivary (at wake, 5 pm and 9 pm across two consecutive days) | Bereaved subjects had significantly lower levels of log-cortisol at wake and dysregulated cortisol rhythm compared to depressed non-bereaved. No significant differences in waking cortisol levels between the two bereaved groups (Groups 2 and 3). |

| Bell et al. [50] | 2020 | USA | Good | Randomized clinical trial | Older bereaved adults (aged 60 years or older) with a diagnosis of CG | // | At least 12 months prior to enrollment | N = 54; N = 32 randomly assigned to receive ART (accelerated resolution therapy) psychotherapy intervention immediately; N = 22 assigned to the control condition (4-week waitlist); females N = 42 (84%); males N = 8 (16%) | 68 (SD = 6.7); age group by years: less than 65 34%; 65–74 46%; 75 or older 20%; age group by sex: females 67.4; males 71.1 | ICG | Cortisol (before and after ART session 1 and 4) and salivary Alfa-Amylase (sAA) (before and after each ART session) | Salivary | The change in pre-ART salivary cortisol level in relation to perceived stress was not associated with the change in cortisol level before and after ART. The variable most strongly associated with cortisol change was antibiotic/antiviral drug use; other associated variables included the use of over-the-counter supplements and the number of ART visits. Conversely, pre-ART sAA was strongly associated with changes in sAA before and after ART. However, consistent with the cortisol findings, the most strongly associated variable was antibiotic/antiviral drug use. Other variables of influence were different medications, months and number of hospital admissions since the loved one’s death. |

| Study | Year | Country | Quality Rating | Type of Study | Sample Characteristics | Grief Assessment | Measured Markers | Biological Sample | Main Findings | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Grief Types/Groups | Loss Relation | Time Since Bereavement | N/n per Group | Age (Years, Mean/Range or SD) | |||||||||

| Pettingale et al. [51] | 1989 | UK | Fair | Cross-sectional study | Bereaved spouses | Spouse | In average 2 years (from one to three and half years) | N = 33; females N = 27; men N = 6 | Mean = 63 years | Grief Experience Inventory | IgG, IgA, IgM, transferrin, alpha-I acid glycoprotein, alpha-2 macroglobulin, cerulosplasmin and alpha-1 anti-trypsin, CD3+ve lymphocytes (total T), CD4+ve lymphocytes (helper/inducer T), CD8+ lymphocytes (cytotoxic T) and CD16+ve (natural killer cells). | Serum (serum proteins) Blood mononuclear cells Two blood samples (between 9 and 10 am) | Reported grief was negatively correlated with the number of CD16+ T cells and alpha-2 macroglobulin levels. The duration of grief was negatively correlated with the number of CD8+ T cells (p < 0.04) and serum levels of IgG (p < 0.05) and transferrin (p < 0.05). |

| Schultze-Florey et al. [52] | 2012 | USA | Good | Case-control study | Bereaved spouses vs. non-bereaved married/partnered | Spouse or partner | in the past 2 years (mean: 23.75 months; range 2–69 months) | N = 64; Bereaved N = 36, among which N = 13 satisfying diagnostic threshold for CG; Non-bereaved N = 28 | Bereaved = 72.9 (SD = 5.8); Non-Bereaved = 72.4 (SD = 4.2) | ICG | IL-6 IL-1RA sTNFRII | Plasma | Circulating levels of IL-1RA and IL-6 were significantly higher in the bereaved group compared to non-bereaved controls. No differences in plasma cytokine levels were found between the two subgroups of bereaved individuals (CG and Non-CG groups). |

| Fagundes et al. [53] | 2019 | USA | Fair | Randomized clinical trial | Bereaved spouses | Spouse (married for at least 3 years) | Up to 14 weeks after loss | N = 99; Females N = 71 (72%); Males N = 28 (28%) | 68.61 (SD = 10.7) | ICG | IFN-γ IL-6 TNF-α IL17-A IL-2. | Supernatants from mitogen-activated whole blood cell cultures | Individuals experiencing greater grief and severe symptomatology had higher levels of the proinflammatory cytokines IFN-γ, IL-6, and TNF-α than those experiencing less grief. Subjects with higher depression scores had higher levels of proinflammatory cytokines. |

| Bui et al. [54] | 2019 | USA | Good | Case-control study | Bereaved adults with a primary diagnosis of CG (Group 1) and a primary diagnosis of MDD (Group 2); psychiatrically healthy bereaved controls (Group 3) | Parent; spouse; other | // | N = 139; Group 1 N = 47; Group 2 N = 46; Group 3 N = 46 Females N = 97 (69.8%); Males N = 42 (30.2%) | Group 1 49.49 (SD = 12.87); Group 2 49.33 (SD = 13.27); Group 3 48.65 (SD = 12.7) | ICG SCI-CG | Oxytocin | Plasma | Patients with primary CG had significantly higher oxytocin levels than those with primary MDD, but not compared to bereaved controls. Using regression models, a primary or probable CG diagnosis was associated with significantly higher oxytocin levels. |

| Harfmann et al. [55] | 2020 | USA | Good | Cross-sectional study | Grievers (N = 44) vs. HC (N = 17). Grievers further divided into high grief (ICG score > 30) vs. low grief (ICG score < 30) groups | 59% lost spouse/partner or child; 32% lost a parent or sibling. | Mean 160 ± 91.6 days (~5 months). | N = 61; Grievers N = 44 Controls N = 17 | Grievers: 65.8 ± 9.2 Controls: 71.4 ± 7.9. | ICG | Endocannabinoids: N-arachidonoylethanolamide (AEA) and 2-arachidonoylglycerol (2-AG). | Serum, fasting morning blood draw (7–11 a.m.). | Grievers showed significantly higher AEA than healthy controls, but no difference in 2-AG. AEA levels were positively correlated with the severity of depression and anxiety symptoms, but only in grievers belonging to the low-grief group. No association was found for 2-AG. |

| Kang et al. [56] | 2021 | USA | Good | Repeated cross-sectional study | Adults aged ≥50 years divided in two groups: Grief and HC. Grief group divided in two subgroups: Grief with High loneliness (Grief-HL Group) and Low loneliness (Grief-LL Group) | Grief-HLgroup: Spouse 33%; son 22%; parent 39%; other 1% Grief-HL group: Spouse 62%; son 19%; parent 8%; other 12% | Up to 13 months before enrollment | N = 64; Grief-HL Group: N = 18; grief LL Group: N = 26; HC: N = 20 Females N = 49 (76.5%); Males N = 15 (23.5%) | Grief-HL group: 60.5 (SD = 7.5); Grief-LL group: 70.5 years (SD = 9.7); HC 70.6 (SD = 9.0) | ICG (Baseline clinical assessment and at weeks 8, 16 and 26) | Endocannabinoids: N-arachidonoylethanolamine (AEA) and 2-arachidonoylglycerol (2-AG) and cortisol (within 20.5 ± 13 days of the baseline clinical visit) | Serum | Serum AEA concentrations were significantly increased in the Grief-HL group compared with HC, but not between the two Grief groups. Serum 2-AG and cortisol concentrations did not differ among the three groups. |

| Brown et al. [57] | 2022 | USA | Fair | Cross-sectional study | Bereaved spouses divided in two subgroups: High-Grief Group (ICG score > 25); Low-Grief Group (ICG score < 25) | Spouse | Approximately 4 months after loss | N = 111; High-grief group N = 38; Low-grief group N = 73 Females N = 72 (65%); Males N = 39 (35%) | High-grief group: 66.29 (SD = 9.94); Low-grief group: 69.04 (SD = 9.04) | ICG | Interleukin-6 (IL-6) | Serum | Subjects with high grief symptoms experienced a 45% increase in IL-6 levels per hour, while those in the low grief group showed only a 26% increase. Thus, high grief was associated with a 19% greater increase in IL-6 per hour than low grief. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Pedrinelli, V.; Rimoldi, B.; Conti, L.; Bordacchini, A.; Parrini, L.; Betti, L.; Giannaccini, G.; Dell’Oste, V.; Carmassi, C. Grief-Related Psychopathology from Complicated Grief to DSM-5-TR Prolonged Grief Disorder: A Systematic Review of Biochemical Findings. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 11835. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262411835

Pedrinelli V, Rimoldi B, Conti L, Bordacchini A, Parrini L, Betti L, Giannaccini G, Dell’Oste V, Carmassi C. Grief-Related Psychopathology from Complicated Grief to DSM-5-TR Prolonged Grief Disorder: A Systematic Review of Biochemical Findings. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2025; 26(24):11835. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262411835

Chicago/Turabian StylePedrinelli, Virginia, Berenice Rimoldi, Lorenzo Conti, Andrea Bordacchini, Livia Parrini, Laura Betti, Gino Giannaccini, Valerio Dell’Oste, and Claudia Carmassi. 2025. "Grief-Related Psychopathology from Complicated Grief to DSM-5-TR Prolonged Grief Disorder: A Systematic Review of Biochemical Findings" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 26, no. 24: 11835. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262411835

APA StylePedrinelli, V., Rimoldi, B., Conti, L., Bordacchini, A., Parrini, L., Betti, L., Giannaccini, G., Dell’Oste, V., & Carmassi, C. (2025). Grief-Related Psychopathology from Complicated Grief to DSM-5-TR Prolonged Grief Disorder: A Systematic Review of Biochemical Findings. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 26(24), 11835. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262411835