Contribution of Vasoactive Intestinal Peptide to the Depressant Effects of Glucagon-like Peptide-2 on Neurally Induced Contractile Responses in Mouse Ileal Preparations

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Functional Experiments

2.1.1. Ileal Spontaneous Activity

2.1.2. Neurally Induced Contractile Responses by EFS

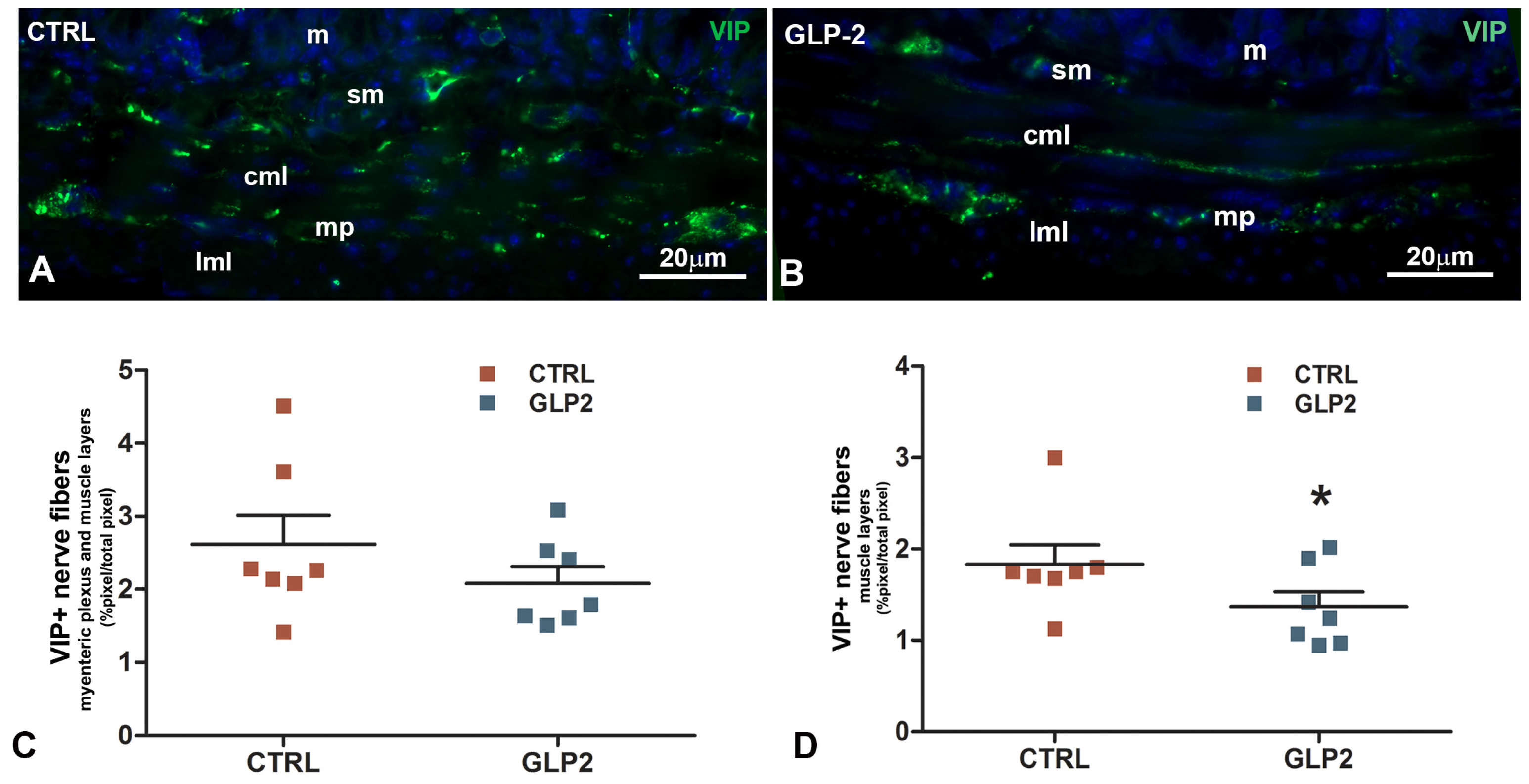

2.2. Immunohistochemical Results

Vasoactive Intestinal Peptide (VIP)-Immunoreactivity (IR) in the Ileal Muscle Coat

3. Discussion

Physiopathological Perspectives

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Animals and Ethical Approval

4.2. Functional Studies

4.2.1. Drugs

4.2.2. Experimental Protocol

4.2.3. Data Analysis and Statistical Tests

4.3. Morphological Studies

4.3.1. Tissue Sampling

4.3.2. Immunohistochemistry

4.3.3. Quantitation and Statistical Analysis

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CTRL | control |

| EFS | electrical field stimulation |

| GLP-2 | glucagon-like peptide-2 |

| GLP-2R | glucagon-like peptide-2 receptor |

| NANC | non-adrenergic, non-cholinergic |

| L-NNA | L-NG-nitro arginine |

| NO | nitric oxide |

| TTX | tetrodotoxin |

| VIP | vasoactive intestinal peptide |

| SBS | short bowel syndrome |

References

- Drucker, D.J.; Yusta, B. Physiology and Pharmacology of the Enteroendocrine Hormone Glucagon-like Peptide-2. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 2014, 76, 561–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rowland, K.J.; Brubaker, P.L. The “Cryptic” Mechanism of Action of Glucagon-like Peptide-2. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 2011, 301, G1–G8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prahm, A.P.; Hvistendahl, M.K.; Brandt, C.F.; Blanche, P.; Hartmann, B.; Holst, J.J.; Jeppesen, P.B. Post-prandial Secretion of Glucagon-like Peptide-2 (GLP-2) After Carbohydrate-, Fat- or Protein-Enriched Meals in Healthy Subjects. Peptides 2023, 169, 171091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brubaker, P.L. The Molecular Determinants of Glucagon-like Peptide Secretion by the Intestinal L Cell. Endocrinology 2022, 163, bqac159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guan, X. The CNS Glucagon-like Peptide-2 Receptor in the Control of Energy Balance and Glucose Homeostasis. Am. J. Physiol. Reg. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 2014, 307, R585–R596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrow, N.M.; Hanson, A.A.; Mulvihill, E.E. Distinct Identity of GLP-1R, GLP-2R, and GIPR Expressing Cells and Signaling Circuits Within the Gastrointestinal Tract. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2021, 9, 703966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Drucker, D.J.; Erlich, P.; Asa, S.L.; Brubaker, P.L. Induction of Intestinal Epithelial Proliferation by Glucagon-like Peptide-2. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1996, 93, 7911–7916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brubaker, P.L. Glucagon-like Peptide-2 and the Regulation of Intestinal Growth and Function. Compr. Physiol. 2018, 8, 1185–1210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldassano, S.; Amato, A.; Caldara, G.F.; Mulè, F. Glucagon-like Peptide-2 Treatment Improves Glucose Dysmetabolism in Mice Fed a High-Fat Diet. Endocrine 2016, 54, 648–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meier, J.J.; Nauck, M.A.; Pott, A.; Heinze, K.; Goetze, O.; Bulut, K.; Schmidt, W.E.; Gallwitz, B.; Holst, J.J. Glucagon-like Peptide-2 Stimulates Glucagon Secretion, Enhances Lipid Absorption, and Inhibits Gastric Acid Secretion in Humans. Gastroenterology 2006, 130, 44–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Koehler, J.; Yusta, B.; Bahrami, J.; Matthews, D.; Rafii, M.; Pencharz, P.B.; Drucker, D.J. Enteroendocrine-Derived Glucagon-like Peptide-2 Controls Intestinal Amino Acid Transport. Mol. Metab. 2017, 6, 245–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moran, A.W.; Al-Rammahi, M.A.; Batchelor, D.J.; Bravo, D.M.; Shirazi-Beechey, S.P. Glucagon-Like Peptide-2 and the Enteric Nervous System Are Components of a Cell–Cell Communication Pathway Regulating Intestinal Na+/Glucose Co-transport. Front. Nutr. 2018, 5, 101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moran, A.W.; Alrammahi, M.; Daly, K.; Weatherburn, D.; Ionescu, C.; Blanchard, A.; Shirazi-Beechey, S.P. Luminal Sweet Sensing and the Enteric Nervous System Participate in Regulation of Intestinal Glucose Transporter GLUT2. Nutrients 2025, 17, 1547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mukherjee, K.; Khan, M.S.A.; Howland, J.G.; Xiao, C. Glucagon-like Peptide-2 Acts Partially Through Central GLP-2R and MC4R in Mobilizing Stored Lipids from the Intestine. Nutrients 2025, 17, 1416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldassano, S.; Amato, A.; Mulè, F. Influence of Glucagon-like Peptide-2 on Energy Homeostasis. Peptides 2016, 86, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Gao, Y.; Cui, L.; Li, Y.; Ling, H.; Tan, X.; Xu, H. Integrative Analysis Revealed the Role of Glucagon-like Peptide-2 in Improving Experimental Colitis in Mice by Inhibiting Inflammatory Pathways, Regulating Glucose Metabolism, and Modulating Gut Microbiota. Front. Microbiol. 2023, 14, 1174308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, A.; Khan, D.; Dubey, V.; Tarasov, A.I.; Flatt, P.R.; Irwin, N. Comparative Effects of GLP-1 and GLP-2 on Beta-Cell Function, Glucose Homeostasis and Appetite Regulation. Biomolecules 2024, 14, 1520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rotondo, A.; Amato, A.; Baldassano, S.; Lentini, L.; Mulè, F. Gastric Relaxation Induced by Glucagon-like Peptide-2 in Mice Fed a High-Fat Diet or Fasted. Peptides 2011, 32, 1587–1592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baccari, M.C.; Vannucchi, M.G.; Idrizaj, E. The Possible Involvement of Glucagon-like Peptide-2 in the Regulation of Food Intake Through the Gut–Brain Axis. Nutrients 2024, 16, 3069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDonagh, S.C.; Lee, J.; Izzo, A.; Brubaker, P.L. Role of Glial Cell–Line Derived Neurotrophic Factor Family Receptor α2 in the Actions of the Glucagon-like Peptides on the Murine Intestine. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 2007, 293, G461–G468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cinci, L.; Faussone-Pellegrini, M.S.; Rotondo, A.; Mulè, F.; Vannucchi, M.G. GLP-2 Receptor Expression in Excitatory and Inhibitory Enteric Neurons and Its Role in Mouse Duodenum Contractility. Neurogastroenterol. Motil. 2011, 23, e383–e392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Halim, M.A.; Degerblad, M.; Sundbom, M.; Karlbom, U.; Holst, J.J.; Webb, D.L.; Hellström, P.M. Glucagon-Like Peptide-1 Inhibits Prandial Gastrointestinal Motility Through Myenteric Neuronal Mechanisms in Humans. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2018, 103, 575–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Idrizaj, E.; Biagioni, C.; Traini, C.; Vannucchi, M.G.; Baccari, M.C. Glucagon-like Peptide-2 Depresses Ileal Contractility in Preparations from Mice Through Opposite Modulatory Effects on Nitrergic and Cholinergic Neurotransmission. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 1855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amato, A.; Rotondo, A.; Cinci, L.; Baldassano, S.; Vannucchi, M.G.; Mulè, F. Role of Cholinergic Neurons in the Motor Effects of Glucagon-like Peptide-2 in Mouse Colon. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 2010, 299, G1038–G1044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Heuvel, E.; Wallace, L.; Sharkey, K.A.; Sigalet, D.L. Glucagon-like Peptide-2 Induces Vasoactive Intestinal Polypeptide Expression in Enteric Neurons via Phosphatidylinositol 3-Kinase-γ Signaling. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 2012, 303, E994–E1005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baccari, M.C.; Traini, C.; Garella, R.; Cipriani, G.; Vannucchi, M.G. Relaxin Exerts Two Opposite Effects on Mechanical Activity and Nitric Oxide Synthase Expression in the Mouse Colon. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 2012, 303, E1142–E1150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verbeure, W.; van Goor, H.; Mori, H.; van Beek, A.P.; Tack, J.; van Dijk, P.R. The Role of Gasotransmitters in Gut Peptide Actions. Front. Pharmacol. 2021, 12, 720703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanders, K.M.; Ward, S.M. Nitric Oxide and Its Role as a Non-Adrenergic, Non-Cholinergic Inhibitory Neurotransmitter in the Gastrointestinal Tract. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2019, 176, 212–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lefebvre, R.A. Non-Adrenergic Non-Cholinergic Neurotransmission in the Proximal Stomach. Gen. Pharmacol. 1993, 24, 257–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garella, R.; Idrizaj, E.; Traini, C.; Squecco, R.; Vannucchi, M.G.; Baccari, M.C. Glucagon-like Peptide-2 Modulates Nitrergic Neurotransmission in Strips from the Mouse Gastric Fundus. World J. Gastroenterol. 2017, 23, 7211–7220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Traini, C.; Idrizaj, E.; Garella, R.; Squecco, R.; Vannucchi, M.G.; Baccari, M.C. Glucagon-like Peptide-2 Interferes with Neurally-Induced Relaxant Responses in Mouse Gastric Strips Through VIP Release. Neuropeptides 2020, 81, 102031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amato, A.; Baldassano, S.; Serio, R.; Mulè, F. Glucagon-like Peptide-2 Relaxes Mouse Stomach Through Vasoactive Intestinal Peptide Release. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 2009, 296, G678–G684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, X.; Karpen, H.E.; Stephens, J.; Bukowski, J.T.; Niu, S.; Zhang, G.; Stoll, B.; Finegold, M.J.; Holst, J.J.; Hadsell, D.; et al. GLP-2 Receptor Localizes to Enteric Neurons and Endocrine Cells Expressing Vasoactive Peptides and Mediates Increased Blood Flow. Gastroenterology 2006, 130, 150–164, Correction in Gastroenterology 2006, 130, 1019–1021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koopmann, M.C.; Nelson, D.W.; Murali, S.G.; Liu, X.; Brownfield, M.S.; Holst, J.J.; Ney, D.M. Exogenous Glucagon-like Peptide-2 (GLP-2) Augments GLP-2 Receptor mRNA and Maintains Proglucagon mRNA Levels in Resected Rats. JPEN J. Parenter. Enteral Nutr. 2008, 32, 254–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boeckxstaens, G.E.; Pelckmans, P.A.; De Man, J.G.; Bult, H.; Herman, A.G.; Van Maercke, Y.M. Evidence for Differential Release of Nitric Oxide and Vasoactive Intestinal Polypeptide by Nonadrenergic Noncholinergic Nerves in Rat Gastric Fundus. Arch. Int. Pharmacodyn. Ther. 1992, 318, 107–115. [Google Scholar]

- Tonini, M.; De Giorgio, R.; De Ponti, F.; Sternini, C.; Spelta, V.; Dionigi, P.; Barbara, G.; Stanghellini, V.; Corinaldesi, R. Role of Nitric Oxide- and Vasoactive Intestinal Polypeptide-Containing Neurones in Human Gastric Fundus Strip Relaxations. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2000, 129, 12–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grider, J.R. Neurotransmitters Mediating the Intestinal Peristaltic Reflex in the Mouse. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2003, 307, 460–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agoston, D.V.; Lisziewicz, J. Calcium Uptake and Protein Phosphorylation in Myenteric Neurons, Like the Release of Vasoactive Intestinal Polypeptide and Acetylcholine, Are Frequency Dependent. J. Neurochem. 1989, 52, 1637–1640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldassano, S.; Liu, S.; Qu, M.H.; Mulè, F.; Wood, J.D. Glucagon-like Peptide-2 Modulates Neurally Evoked Mucosal Chloride Secretion in Guinea Pig Small Intestine In Vitro. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 2009, 297, G800–G805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, X.; De Palma, G.; Boschetti, E.; Nishiharo, Y.; Lu, J.; Shimbori, C.; Costanzini, A.; Saqib, Z.; Kraimi, N.; Sidani, S.; et al. Vasoactive Intestinal Polypeptide Plays a Key Role in the Microbial–Neuroimmune Control of Intestinal Motility. Cell. Mol. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2024, 17, 383–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, B.; Wang, T.; Sun, L. Evolution and Therapeutic Potential of Glucagon-like Peptide-2 Analogs. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2025, 233, 116758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeppesen, P.B.; Pertkiewicz, M.; Messing, B.; Iyer, K.; Seidner, D.L.; O’Keefe, S.J.; Forbes, A.; Heinze, H.; Joelsson, B. Teduglutide Reduces Need for Parenteral Support Among Patients with Short Bowel Syndrome with Intestinal Failure. Gastroenterology 2012, 143, 1473–1481.e3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Skarbaliene, J.; Mathiesen, J.M.; Larsen, B.D.; Thorkildsen, C.; Petersen, Y.M. Glepaglutide, a Novel Glucagon-Like Peptide-2 Agonist, Has Anti-Inflammatory and Mucosal Regenerative Effects in an Experimental Model of Inflammatory Bowel Disease in Rats. BMC Gastroenterol. 2023, 23, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goldschmidt, M.L.; Oliveira, S.; Slaughter, C.; Kocoshis, S.A. Use of Glucagon-Like Peptide-2 Analogs for Intestinal Failure. Expert Opin. Pharmacother. 2024, 25, 2341–2346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pedersen, J.; Pedersen, N.B.; Brix, S.W.; Grunddal, K.V.; Rosenkilde, M.M.; Hartmann, B.; Ørskov, C.; Poulsen, S.S.; Holst, J.J. The Glucagon-Like Peptide-2 Receptor Is Expressed in Enteric Neurons and Not in the Intestinal Epithelium. Peptides 2015, 67, 20–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukherjee, K.; Xiao, C. GLP-2 Regulation of Intestinal Lipid Handling. Front. Physiol. 2024, 15, 1358625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fung, C.; Unterweger, P.; Parry, L.J.; Bornstein, J.C.; Foong, J.P. VPAC1 Receptors Regulate Intestinal Secretion and Muscle Contractility by Activating Cholinergic Neurons in Guinea Pig Jejunum. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 2014, 306, G748–G758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glerup, P.; Sonne, K.; Berner-Hansen, M.; Skarbaliene, J. Short- versus long-term, gender and species differences in the intestinotrophic effects of long-acting glucagon-like peptide 2 analog. Physiol. Res. 2022, 71, 323–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furness, J.B. Integrated Neural and Endocrine Control of Gastrointestinal Function. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2016, 891, 159–173. [Google Scholar]

- Idrizaj, E.; Garella, R.; Francini, F.; Squecco, R.; Baccari, M.C. Relaxin Influences Ileal Muscular Activity Through a Dual Signaling Pathway in Mice. World J. Gastroenterol. 2018, 24, 882–893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulè, F.; Serio, R. NANC inhibitory neurotransmission in mouse isolated stomach: Involvement of nitric oxide, ATP and vasoactive intestinal polypeptide. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2003, 140, 431–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Baccari, M.C.; Conti, D.; Vannucchi, M.G.; Idrizaj, E. Contribution of Vasoactive Intestinal Peptide to the Depressant Effects of Glucagon-like Peptide-2 on Neurally Induced Contractile Responses in Mouse Ileal Preparations. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 11797. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262411797

Baccari MC, Conti D, Vannucchi MG, Idrizaj E. Contribution of Vasoactive Intestinal Peptide to the Depressant Effects of Glucagon-like Peptide-2 on Neurally Induced Contractile Responses in Mouse Ileal Preparations. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2025; 26(24):11797. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262411797

Chicago/Turabian StyleBaccari, Maria Caterina, Donata Conti, Maria Giuliana Vannucchi, and Eglantina Idrizaj. 2025. "Contribution of Vasoactive Intestinal Peptide to the Depressant Effects of Glucagon-like Peptide-2 on Neurally Induced Contractile Responses in Mouse Ileal Preparations" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 26, no. 24: 11797. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262411797

APA StyleBaccari, M. C., Conti, D., Vannucchi, M. G., & Idrizaj, E. (2025). Contribution of Vasoactive Intestinal Peptide to the Depressant Effects of Glucagon-like Peptide-2 on Neurally Induced Contractile Responses in Mouse Ileal Preparations. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 26(24), 11797. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262411797