Identification of Sulfonamide-Vinyl Sulfone/Chalcone and Berberine-Cinnamic Acid Hybrids as Potent DENV and ZIKV NS2B/NS3 Allosteric Inhibitors

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

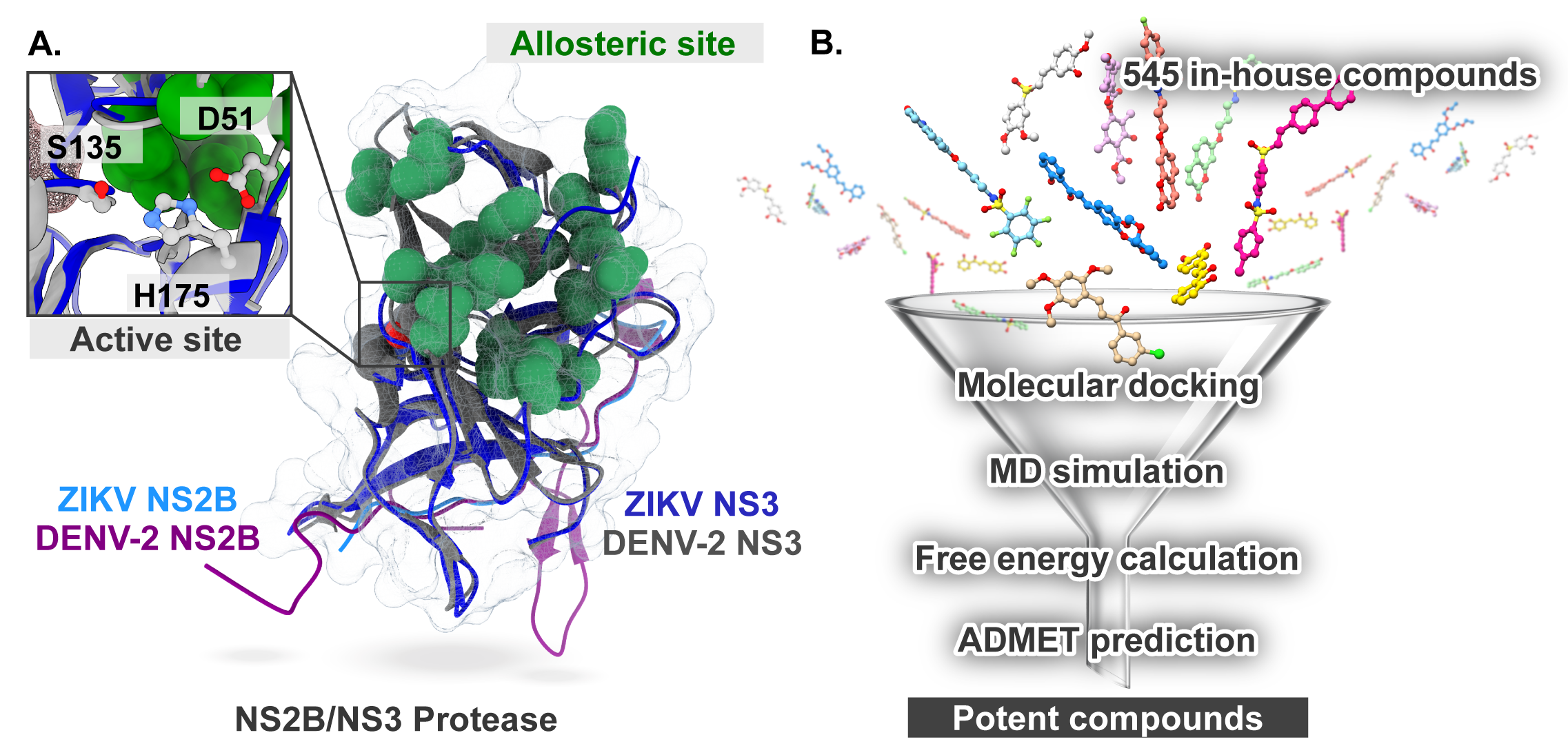

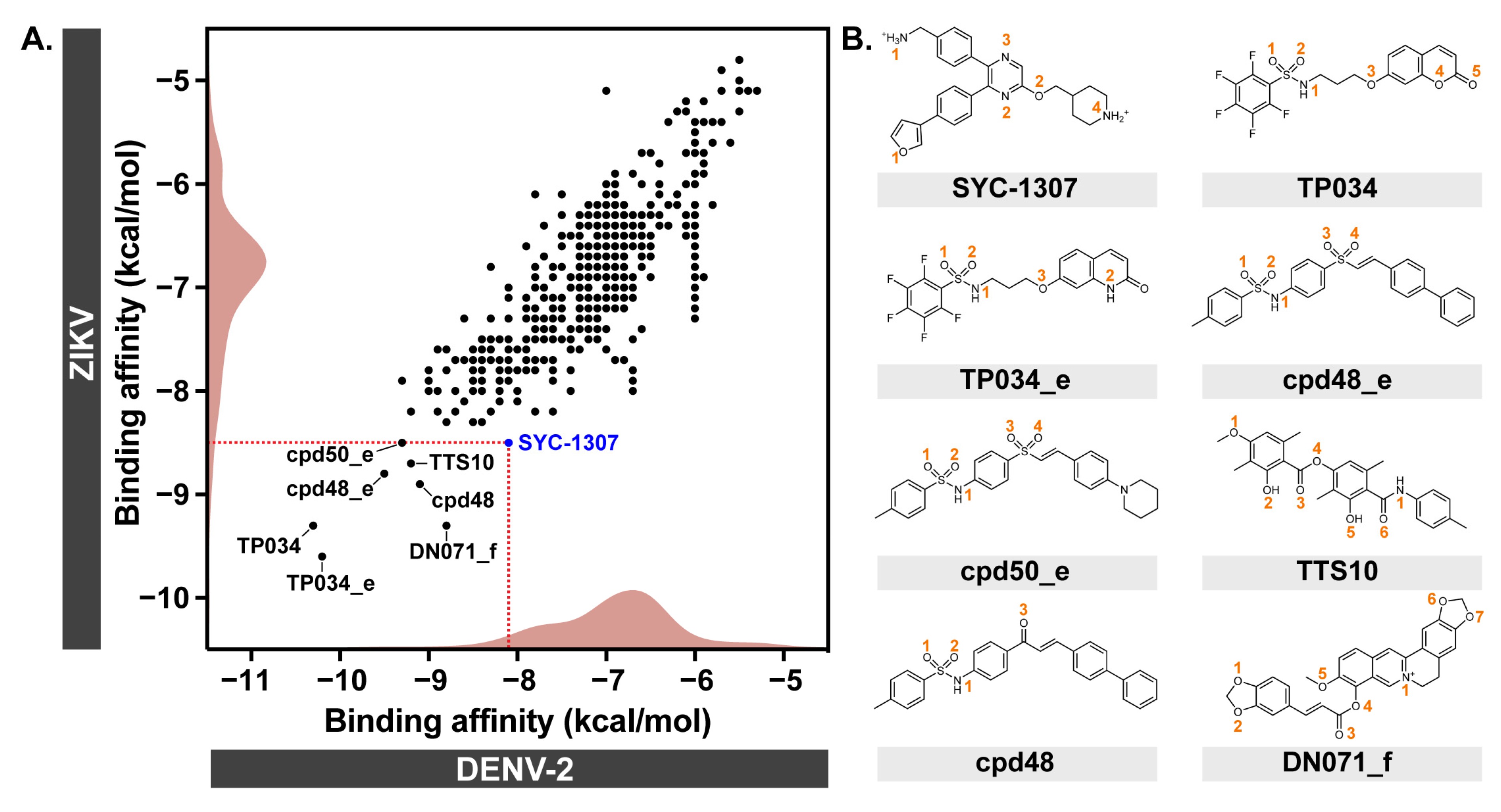

2.1. Molecular Docking

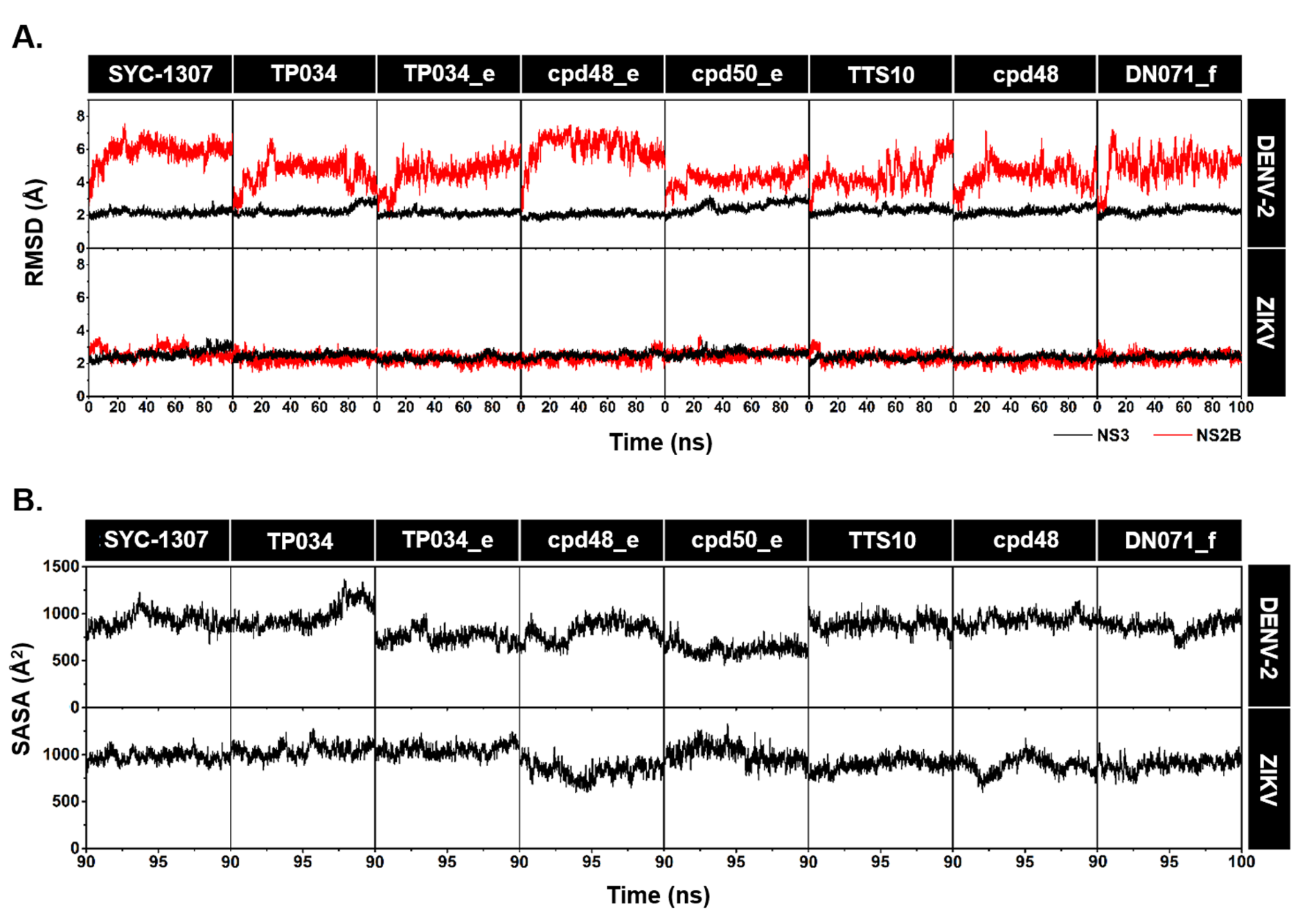

2.2. System Stability and Water Accessibility

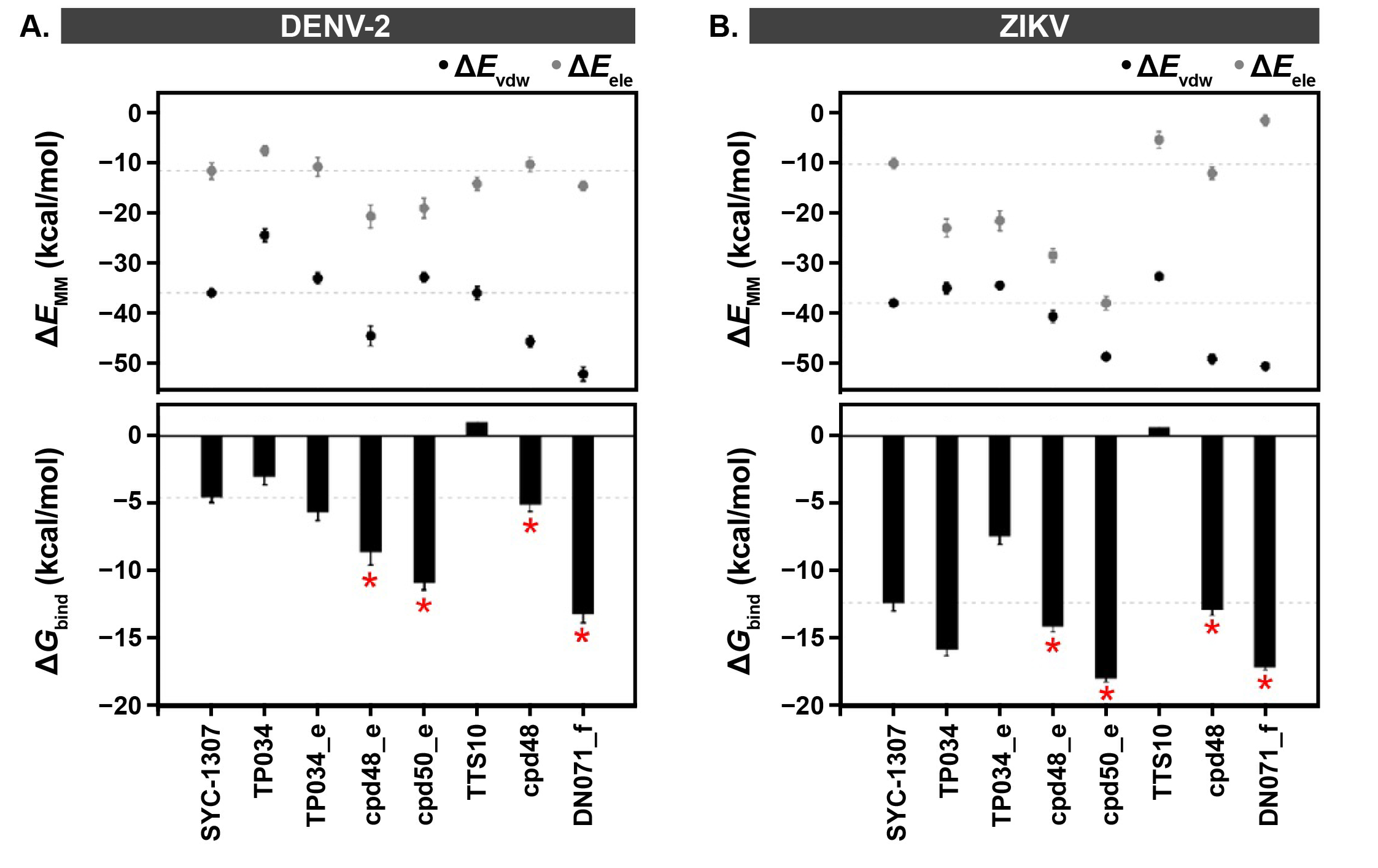

2.3. Binding Susceptibility

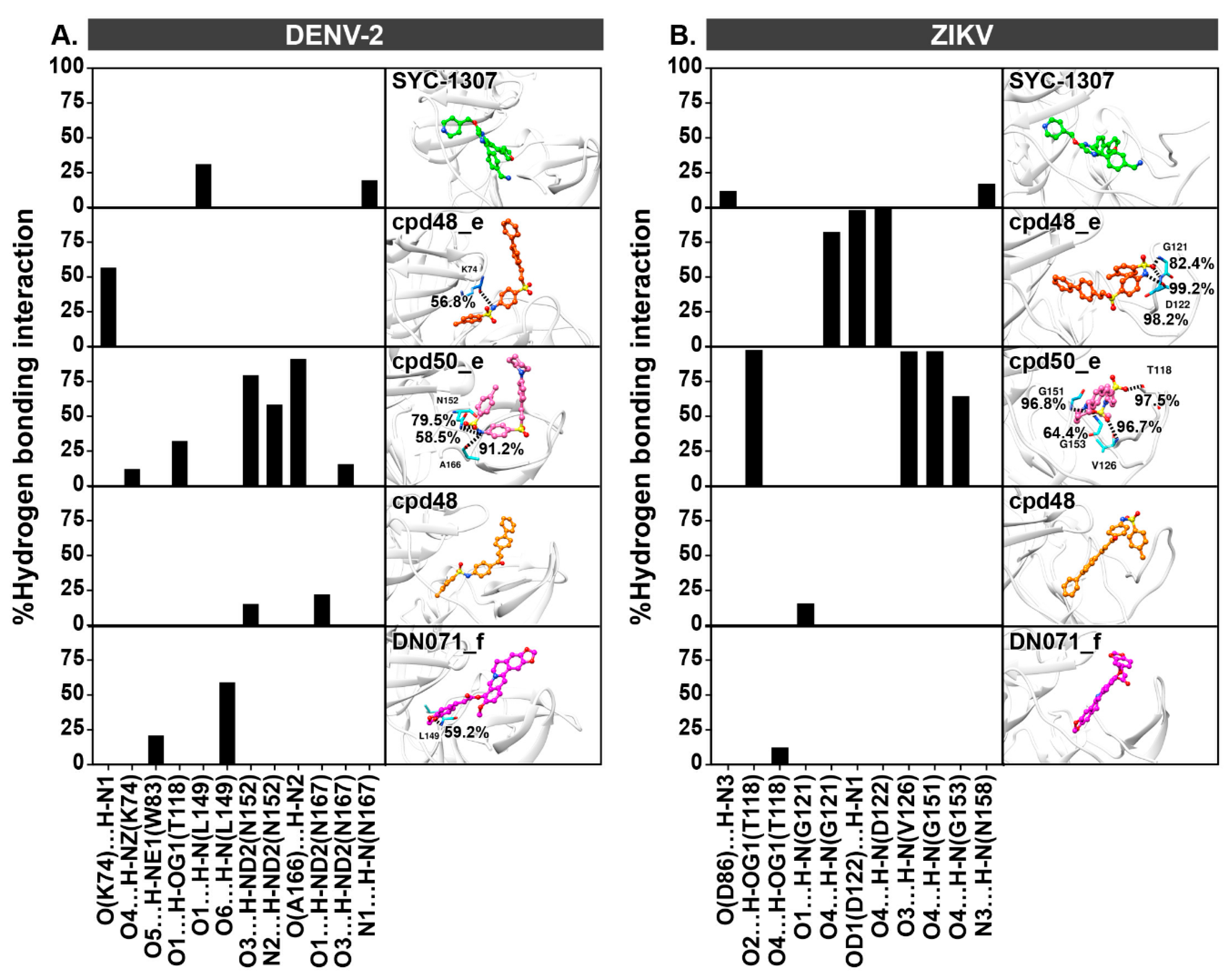

2.4. Hydrogen Bonding

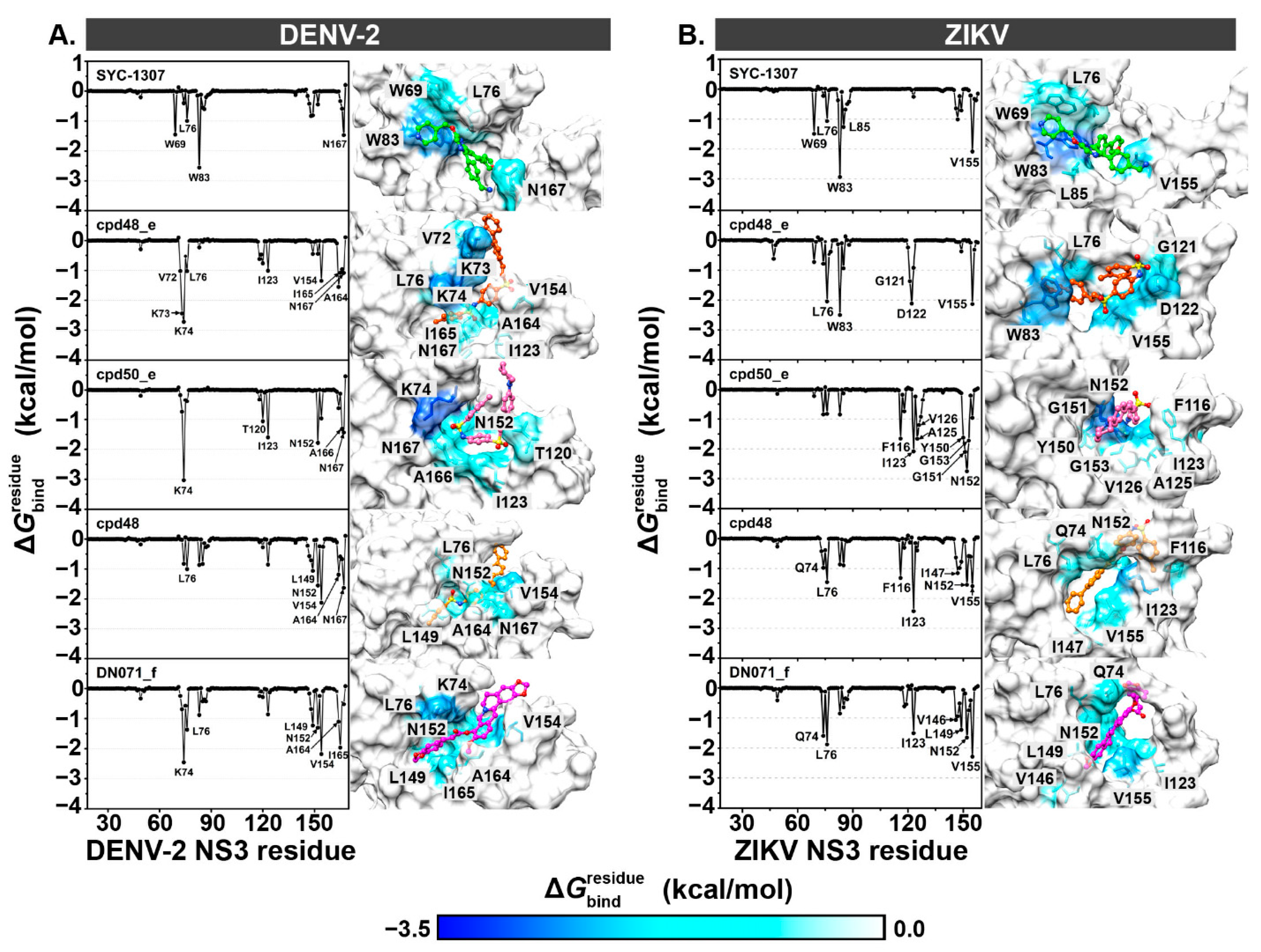

2.5. Key Binding Residues

2.6. Drug-Likeness and Pharmacokinetics

3. Computational Methods

3.1. Structural Preparation and Molecular Docking

3.2. Molecular Dynamics (MD) Simulation

3.3. Structural and Energetic Analyses

3.4. Prediction of Drug-Likeness and Pharmacokinetics

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Silva, N.M.; Santos, N.C.; Martins, I.C. Dengue and Zika Viruses: Epidemiological History, Potential Therapies, and Promising Vaccines. Trop. Med. Infect. Dis. 2020, 5, 150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, D.C.-D.; Weng, S.-C.; Tsao, P.-N.; Chu, J.J.H.; Shiao, S.-H. Co-infection of dengue and Zika viruses mutually enhances viral replication in the mosquito Aedes aegypti. Parasites Vectors 2023, 16, 160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahebwa, A.; Hii, J.; Neoh, K.-B.; Chareonviriyaphap, T. Aedes aegypti and Aedes albopictus (Diptera: Culicidae) ecology, biology, behaviour, and implications on arbovirus transmission in Thailand: Review. One Health 2023, 16, 100555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sekaran, S.D.; Ismail, A.A.; Thergarajan, G.; Chandramathi, S.; Rahman, S.K.H.; Mani, R.R.; Jusof, F.F.; Lim, Y.A.L.; Manikam, R. Host immune response against DENV and ZIKV infections. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2022, 12, 975222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stawicki, S.P.; Sikka, V.; Chattu, V.K.; Popli, R.K.; Galwankar, S.C.; Kelkar, D.; Sawicki, S.G.; Papadimos, T.J. The Emergence of Zika Virus as a Global Health Security Threat: A Review and a Consensus Statement of the INDUSEM Joint working Group (JWG). J. Glob. Infect. Dis. 2016, 8, 3–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chuang, F.-K.; Liao, C.-L.; Hu, M.-K.; Chiu, Y.-L.; Lee, A.-R.; Huang, S.-M.; Chiu, Y.-L.; Tsai, P.-L.; Su, B.-C.; Chang, T.-H.; et al. Antiviral Activity of Compound L3 against Dengue and Zika Viruses In Vitro and In Vivo. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 4050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Zhang, Y.; Jia, R.; Wang, M.; Yin, Z.; Cheng, A. Structure and function of capsid protein in flavivirus infection and its applications in the development of vaccines and therapeutics. Vet. Res. 2021, 52, 98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skoreński, M.; Grzywa, R.; Sieńczyk, M. Why should we target viral serine proteases when developing antiviral agents? Future Virol. 2016, 11, 745–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nutho, B.; Rungrotmongkol, T. Binding recognition of substrates in NS2B/NS3 serine protease of Zika virus revealed by molecular dynamics simulations. J. Mol. Graph. Model. 2019, 92, 227–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yildiz, M.; Ghosh, S.; Bell, J.A.; Sherman, W.; Hardy, J.A. Allosteric Inhibition of the NS2B-NS3 Protease from Dengue Virus. ACS Chem. Biol. 2013, 8, 2744–2752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zephyr, J.; Rao, D.N.; Johnson, C.; Shaqra, A.M.; Nalivaika, E.A.; Jordan, A.; Yilmaz, N.K.; Ali, A.; Schiffer, C.A. Allosteric quinoxaline-based inhibitors of the flavivirus NS2B/NS3 protease. Bioorg. Chem. 2023, 131, 106269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brecher, M.; Li, Z.; Liu, B.; Zhang, J.; Koetzner, C.A.; Alifarag, A.; Jones, S.A.; Lin, Q.; Kramer, L.D.; Li, H. A conformational switch high-throughput screening assay and allosteric inhibition of the flavivirus NS2B-NS3 protease. PLoS Pathog. 2017, 13, e1006411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Millies, B.; von Hammerstein, F.; Gellert, A.; Hammerschmidt, S.; Barthels, F.; Göppel, U.; Immerheiser, M.; Elgner, F.; Jung, N.; Basic, M.; et al. Proline-Based Allosteric Inhibitors of Zika and Dengue Virus NS2B/NS3 Proteases. J. Med. Chem. 2019, 62, 11359–11382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meewan, I.; Shiryaev, S.A.; Kattoula, J.; Huang, C.-T.; Lin, V.; Chuang, C.-H.; Terskikh, A.V.; Abagyan, R. Allosteric Inhibitors of Zika Virus NS2B-NS3 Protease Targeting Protease in “Super-Open” Conformation. Viruses 2023, 15, 1106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gangopadhyay, A.; Saha, A. Exploring allosteric hits of the NS2B-NS3 protease of DENV2 by structure-guided screening. Comput. Biol. Chem. 2023, 104, 107876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sangpheak, K.; Mueller, M.; Darai, N.; Wolschann, P.; Suwattanasophon, C.; Ruga, R.; Chavasiri, W.; Seetaha, S.; Choowongkomon, K.; Kungwan, N.; et al. Computational screening of chalcones acting against topoisomerase IIα and their cytotoxicity towards cancer cell lines. J. Enzym. Inhib. Med. Chem. 2019, 34, 134–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sangpheak, K.; Tabtimmai, L.; Seetaha, S.; Rungnim, C.; Chavasiri, W.; Wolschann, P.; Choowongkomon, K.; Rungrotmongkol, T. Biological Evaluation and Molecular Dynamics Simulation of Chalcone Derivatives as Epidermal Growth Factor-Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitors. Molecules 2019, 24, 1092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aiebchun, T.; Mahalapbutr, P.; Auepattanapong, A.; Khaikate, O.; Seetaha, S.; Tabtimmai, L.; Kuhakarn, C.; Choowongkomon, K.; Rungrotmongkol, T. Identification of Vinyl Sulfone Derivatives as EGFR Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitor: In Vitro and In Silico Studies. Molecules 2021, 26, 2211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hengphasatporn, K.; Aiebchun, T.; Mahalapbutr, P.; Auepattanapong, A.; Khaikate, O.; Choowongkomon, K.; Kuhakarn, C.; Meesin, J.; Shigeta, Y.; Rungrotmongkol, T. Sulfonylated Indeno[1,2-c]quinoline Derivatives as Potent EGFR Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitors. ACS Omega 2023, 8, 19645–19655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, D.V.; Hengphasatporn, K.; Danova, A.; Suroengrit, A.; Boonyasuppayakorn, S.; Fujiki, R.; Shigeta, Y.; Rungrotmongkol, T.; Chavasiri, W. Structure-yeast α-glucosidase inhibitory activity relationship of 9-O-berberrubine carboxylates. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 18865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mottin, M.; Caesar, L.K.; Brodsky, D.; Mesquita, N.C.; de Oliveira, K.Z.; Noske, G.D.; Sousa, B.K.; Ramos, P.R.; Jarmer, H.; Loh, B.; et al. Chalcones from Angelica keiskei (ashitaba) inhibit key Zika virus replication proteins. Bioorg. Chem. 2022, 120, 105649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behrouz, S.; Kühl, N.; Klein, C.D. N-sulfonyl peptide-hybrids as a new class of dengue virus protease inhibitors. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2023, 251, 115227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nguyen, C.Q.; Nguyen, T.H.M.; Nguyen, T.T.T.; Bui, T.B.H.; Nguyen, T.T.; Huynh, N.T.; Le, T.D.; Nguyen, T.M.P.; Nguyen, D.T.; Nguyen, M.T.; et al. Designs, Synthesis, Docking Studies, and Biological Evaluation of Novel Berberine Derivatives Targeting Zika Virus. J. Chem. 2021, 2021, 5567111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dang, M.; Lim, L.; Roy, A.; Song, J. Myricetin Allosterically Inhibits the Dengue NS2B-NS3 Protease by Disrupting the Active and Locking the Inactive Conformations. ACS Omega 2022, 7, 2798–2808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yusufzai, S.K.; Osman, H.; Khan, M.S.; Razik, B.M.A.; Ezzat, M.O.; Mohamad, S.; Sulaiman, O.; Gansau, J.A.; Parumasivam, T. 4-Thiazolidinone coumarin derivatives as two-component NS2B/NS3 DENV flavivirus serine protease inhibitors: Synthesis, molecular docking, biological evaluation and structure-activity relationship studies. Chem. Cent. J. 2018, 12, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yusoff, N.M.; Asari, A.; Addis, S.N.K. The data on molecular docking of cinnamic acid amide on dengue viral target NS2B/NS3. Data Brief 2022, 42, 108036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, Y.; Huo, T.; Lin, Y.-L.; Nie, S.; Wu, F.; Hua, Y.; Wu, J.; Kneubehl, A.R.; Vogt, M.B.; Rico-Hesse, R.; et al. Discovery, X-ray Crystallography and Antiviral Activity of Allosteric Inhibitors of Flavivirus NS2B-NS3 Protease. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2019, 141, 6832–6836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhakat, S.; Delang, L.; Kaptein, S.; Neyts, J.; Leyssen, P.; Jayaprakash, V. Reaching beyond HIV/HCV: Nelfinavir as a potential starting point for broad-spectrum protease inhibitors against dengue and chikungunya virus. RSC Adv. 2015, 5, 85938–85949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirza, M.U.; Alanko, I.; Vanmeert, M.; Muzzarelli, K.M.; Salo-Ahen, O.M.; Abdullah, I.; Kovari, I.A.; Claes, S.; De Jonghe, S.; Schols, D.; et al. The discovery of Zika virus NS2B-NS3 inhibitors with antiviral activity via an integrated virtual screening approach. Eur. J. Pharm. Sci. 2022, 175, 106220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woo, S.Y.; Kim, J.H.; Moon, M.K.; Han, S.-H.; Yeon, S.K.; Choi, J.W.; Jang, B.K.; Song, H.J.; Kang, Y.G.; Kim, J.W.; et al. Discovery of Vinyl Sulfones as a Novel Class of Neuroprotective Agents toward Parkinson’s Disease Therapy. J. Med. Chem. 2014, 57, 1473–1487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timiri, A.K.; Selvarasu, S.; Kesherwani, M.; Vijayan, V.; Sinha, B.N.; Devadasan, V.; Jayaprakash, V. Synthesis and molecular modelling studies of novel sulphonamide derivatives as dengue virus 2 protease inhibitors. Bioorg. Chem. 2015, 62, 74–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, L.H.; Rocha, R.E.O.; Dias, D.L.; Ribeiro, B.M.R.M.; Serafim, M.S.M.; Abrahão, J.S.; Ferreira, R.S. Evaluating Known Zika Virus NS2B-NS3 Protease Inhibitor Scaffolds via In Silico Screening and Biochemical Assays. Pharmaceuticals 2023, 16, 1319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kiat, T.S.; Pippen, R.; Yusof, R.; Ibrahim, H.; Khalid, N.; Rahman, N.A. Inhibitory activity of cyclohexenyl chalcone derivatives and flavonoids of fingerroot, Boesenbergia rotunda (L.), towards dengue-2 virus NS3 protease. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2006, 16, 3337–3340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sahoo, M.; Jena, L.; Daf, S.; Kumar, S. Virtual Screening for Potential Inhibitors of NS3 Protein of Zika Virus. Genom. Inf. 2016, 14, 104–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mukhametov, A.; Newhouse, E.I.; Ab Aziz, N.; Saito, J.A.; Alam, M. Allosteric pocket of the dengue virus (serotype 2) NS2B/NS3 protease: In silico ligand screening and molecular dynamics studies of inhibition. J. Mol. Graph. Model. 2014, 52, 103–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, R.A.D.; Rocha, J.A.D.; Pinheiro, A.S.; Costa, A.D.S.D.; Rocha, E.C.D.; Silva, R.C.; Gonçalves, A.D.S.; Santos, C.B.; Brasil, D.D.S. A Computational Approach Applied to the Study of Potential Allosteric Inhibitors Protease NS2B/NS3 from Dengue Virus. Molecules 2022, 27, 4118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dharmapalan, B.T.; Biswas, R.; Sankaran, S.; Venkidasamy, B.; Thiruvengadam, M.; George, G.; Rebezov, M.; Zengin, G.; Gallo, M.; Montesano, D.; et al. Inhibitory Potential of Chromene Derivatives on Structural and Non-Structural Proteins of Dengue Virus. Viruses 2022, 14, 2656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rehman, H.M.; Sajjad, M.; Ali, M.A.; Gul, R.; Irfan, M.; Naveed, M.; Bhinder, M.A.; Ghani, M.U.; Hussain, N.; Said, A.S.A.; et al. Identification of NS2B-NS3 Protease Inhibitors for Therapeutic Application in ZIKV Infection: A Pharmacophore-Based High-Throughput Virtual Screening and MD Simulations Approaches. Vaccines 2023, 11, 131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Liang, B.; Aarthy, M.; Singh, S.K.; Garg, N.; Mysorekar, I.U.; Giri, R. Hydroxychloroquine Inhibits Zika Virus NS2B-NS3 Protease. ACS Omega 2018, 3, 18132–18141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, Y.; Cheng, F.; Zhang, J.; Su, H.; Hu, H.; Zou, Y.; Li, M.; Xu, Y. Structure-based design of a novel inhibitor of the ZIKA virus NS2B/NS3 protease. Bioorg. Chem. 2022, 128, 106109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vilela, G.G.; Silva, W.F.d.S.; Batista, V.d.M.; Silva, L.R.; Maus, H.; Hammerschmidt, S.J.; Costa, C.A.C.B.; Moura, O.F.d.S.; de Freitas, J.D.; Coelho, G.L.; et al. Fragment-based design of α-cyanoacrylates and α-cyanoacrylamides targeting Dengue and Zika NS2B/NS3 proteases. New J. Chem. 2022, 46, 20322–20346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguilera-Pesantes, D.; Robayo, L.; Méndez, P.; Mollocana, D.; Marrero-Ponce, Y.; Torres, F.; Méndez, M. Discovering key residues of dengue virus NS2b-NS3-protease: New binding sites for antiviral inhibitors design. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2017, 492, 631–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huber, S.; Braun, N.J.; Schmacke, L.C.; Quek, J.P.; Murra, R.; Bender, D.; Hildt, E.; Luo, D.; Heine, A.; Steinmetzer, T. Structure-Based Optimization and Characterization of Macrocyclic Zika Virus NS2B-NS3 Protease Inhibitors. J. Med. Chem. 2022, 65, 6555–6572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mottin, M.; Sousa, B.K.d.P.; Mesquita, N.C.d.M.R.; de Oliveira, K.I.Z.; Noske, G.D.; Sartori, G.R.; Albuquerque, A.d.O.; Urbina, F.; Puhl, A.C.; Moreira-Filho, J.T.; et al. Discovery of New Zika Protease and Polymerase Inhibitors through the Open Science Collaboration Project OpenZika. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2022, 62, 6825–6843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daina, A.; Michielin, O.; Zoete, V. SwissADME: A free web tool to evaluate pharmacokinetics, drug-likeness and medicinal chemistry friendliness of small molecules. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 42717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lipinski, C.A. Lead- and drug-like compounds: The rule-of-five revolution. Drug Discov. Today Technol. 2004, 1, 337–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erbel, P.; Schiering, N.; D’ARcy, A.; Renatus, M.; Kroemer, M.; Lim, S.P.; Yin, Z.; Keller, T.H.; Vasudevan, S.G.; Hommel, U. Structural basis for the activation of flaviviral NS3 proteases from dengue and West Nile virus. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2006, 13, 372–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koebel, M.R.; Schmadeke, G.; Posner, R.G.; Sirimulla, S. AutoDock VinaXB: Implementation of XBSF, new empirical halogen bond scoring function, into AutoDock Vina. J. Cheminform. 2016, 8, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frisch, M.J.; Trucks, G.W.; Schlegel, H.B.; Scuseria, G.E.; Robb, M.A.; Cheeseman, J.R.; Scalmani, G.; Barone, V.; Mennucci, B.; Petersson, G.A.; et al. 75 Gaussian 09, Revision d. 01; Gaussian. Inc.: Wallingford, CT, USA, 2009; Volume 201. [Google Scholar]

- Mahalapbutr, P.; Leechaisit, R.; Thongnum, A.; Todsaporn, D.; Prachayasittikul, V.; Rungrotmongkol, T.; Prachayasittikul, S.; Ruchirawat, S.; Prachayasittikul, V.; Pingaew, R. Discovery of Anilino-1,4-naphthoquinones as Potent EGFR Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitors: Synthesis, Biological Evaluation, and Comprehensive Molecular Modeling. ACS Omega 2022, 7, 17881–17893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanachai, K.; Mahalapbutr, P.; Lee, V.S.; Rungrotmongkol, T.; Hannongbua, S. In Silico Elucidation of Potent Inhibitors and Rational Drug Design against SARS-CoV-2 Papain-like Protease. J. Phys. Chem. B 2021, 125, 13644–13656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oo, A.; Kerdpol, K.; Mahalapbutr, P.; Rungrotmongkol, T. Molecular encapsulation of emodin with various β-cyclodextrin derivatives: A computational study. J. Mol. Liq. 2022, 347, 118002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maier, J.A.; Martinez, C.; Kasavajhala, K.; Wickstrom, L.; Hauser, K.E.; Simmerling, C. ff14SB: Improving the Accuracy of Protein Side Chain and Backbone Parameters from ff99SB. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2015, 11, 3696–3713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahalapbutr, P.; Charoenwongpaiboon, T.; Phongern, C.; Kongtaworn, N.; Hannongbua, S.; Rungrotmongkol, T. Molecular encapsulation of a key odor-active 2-acetyl-1-pyrroline in aromatic rice with β-cyclodextrin derivatives. J. Mol. Liq. 2021, 337, 116394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jorgensen, W.L.; Chandrasekhar, J.; Madura, J.D.; Impey, R.W.; Klein, M.L. Comparison of simple potential functions for simulating liquid water. J. Chem. Phys. 1983, 79, 926–935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darden, T.; York, D.; Pedersen, L. Particle mesh Ewald: An N·log(N) method for Ewald sums in large systems. J. Chem. Phys. 1993, 98, 10089–10092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryckaert, J.-P.; Ciccotti, G.; Berendsen, H.J.C. Numerical integration of the cartesian equations of motion of a system with constraints: Molecular dynamics of n-alkanes. J. Comput. Phys. 1977, 23, 327–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berendsen, H.J.C.; Postma, J.P.M.; Van Gunsteren, W.F.; DiNola, A.; Haak, J.R. Molecular dynamics with coupling to an external bath. J. Chem. Phys. 1984, 81, 3684–3690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uberuaga, B.P.; Anghel, M.; Voter, A.F. Synchronization of trajectories in canonical molecular-dynamics simulations: Observation, explanation, and exploitation. J. Chem. Phys. 2004, 120, 6363–6374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roe, D.R.; Cheatham, T.E. PTRAJ and CPPTRAJ: Software for Processing and Analysis of Molecular Dynamics Trajectory Data. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2013, 9, 3084–3095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Case, D.A.; Belfon, K.A.A.; Ben-Shalom, I.Y.; Brozell, S.R.; Cerutti, D.S.; Cheatham, T.E., III; Cruzeiro, V.W.D.; Darden, T.A.; Duke, R.E.; Giambasu, G.; et al. AMBER 2020; University of California: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Tsui, V.; Case, D.A. Theory and applications of the generalized born solvation model in macromolecular simulations. Biopolymers 2000, 56, 275–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patigo, A.; Hengphasatporn, K.; Cao, V.; Paunrat, W.; Vijara, N.; Chokmahasarn, T.; Maitarad, P.; Rungrotmongkol, T.; Shigeta, Y.; Boonyasuppayakorn, S.; et al. Design, synthesis, in vitro, in silico, and SAR studies of flavone analogs towards anti-dengue activity. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 21646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, V.; Sukanadi, I.P.; Loeanurit, N.; Suroengrit, A.; Paunrat, W.; Vibulakhaopan, V.; Hengphasatporn, K.; Shigeta, Y.; Chavasiri, W.; Boonyasuppayakorn, S. A sulfonamide chalcone inhibited dengue virus with a potential target at the SAM-binding site of viral methyltransferase. Antivir. Res. 2023, 220, 105753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Binding Affinity (kcal/mol) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Compound | Core Structure | DENV-2 | ZIKV |

| SYC-1307 | Reference | −8.1 | −8.5 |

| TP034 | Sulfonamide, Coumarin | −10.3 | −9.3 |

| TP034_e | Sulfonamide, Quinolinone | −10.2 | −9.6 |

| cpd48_e | Sulfonamide, Vinyl sulfone | −9.5 | −8.8 |

| cpd50_e | Sulfonamide, Vinyl sulfone | −9.3 | −8.5 |

| TTS10 | Evernic acid, 4-Methylaniline | −9.2 | −8.7 |

| cpd48 | Sulfonamide, Chalcone | −9.1 | −8.9 |

| DN071_f | Berberine, 3,4-(Methylenedioxy)cinnamic acid | −8.8 | −9.3 |

| Compound | Lipinski’s Rule of Five | Drug-Likeness | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MW (≤500 Da) | HBD (≤5) | HBA (≤10) | RB (≤10) | TPSA (≤140 Å2) | MLogP (≤5) | ||

| SYC-1307 | 442.55 | 2 | 4 | 7 | 92.40 | −5.53 | Yes |

| cpd48_e | 489.61 | 1 | 4 | 7 | 97.07 | 4.42 | Yes |

| cpd50_e | 496.64 | 1 | 4 | 7 | 100.31 | 3.48 | Yes |

| cpd48 | 453.55 | 1 | 3 | 7 | 71.62 | 4.43 | Yes |

| DN071_f | 496.49 | 0 | 7 | 5 | 76.33 | 3.06 | Yes |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mahalapbutr, P.; Hengphasatporn, K.; Manimont, W.; Vajarintarangoon, L.; Shigeta, Y.; Bhat, N.; Aiebchun, T.; Nutho, B.; Hannongbua, S.; Rungrotmongkol, T. Identification of Sulfonamide-Vinyl Sulfone/Chalcone and Berberine-Cinnamic Acid Hybrids as Potent DENV and ZIKV NS2B/NS3 Allosteric Inhibitors. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 11762. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311762

Mahalapbutr P, Hengphasatporn K, Manimont W, Vajarintarangoon L, Shigeta Y, Bhat N, Aiebchun T, Nutho B, Hannongbua S, Rungrotmongkol T. Identification of Sulfonamide-Vinyl Sulfone/Chalcone and Berberine-Cinnamic Acid Hybrids as Potent DENV and ZIKV NS2B/NS3 Allosteric Inhibitors. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2025; 26(23):11762. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311762

Chicago/Turabian StyleMahalapbutr, Panupong, Kowit Hengphasatporn, Wachirapol Manimont, Ladawan Vajarintarangoon, Yasuteru Shigeta, Nayana Bhat, Thitinan Aiebchun, Bodee Nutho, Supot Hannongbua, and Thanyada Rungrotmongkol. 2025. "Identification of Sulfonamide-Vinyl Sulfone/Chalcone and Berberine-Cinnamic Acid Hybrids as Potent DENV and ZIKV NS2B/NS3 Allosteric Inhibitors" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 26, no. 23: 11762. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311762

APA StyleMahalapbutr, P., Hengphasatporn, K., Manimont, W., Vajarintarangoon, L., Shigeta, Y., Bhat, N., Aiebchun, T., Nutho, B., Hannongbua, S., & Rungrotmongkol, T. (2025). Identification of Sulfonamide-Vinyl Sulfone/Chalcone and Berberine-Cinnamic Acid Hybrids as Potent DENV and ZIKV NS2B/NS3 Allosteric Inhibitors. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 26(23), 11762. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311762