Dentinogenic Effect of BMP-7 on Wharton’s Jelly Mesenchymal Stem Cells Cultured in Decellularized Dental Pulp

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. MTT Assays

2.2. Histological Evaluation of Human Dental Pulp and Decellularized Scaffold

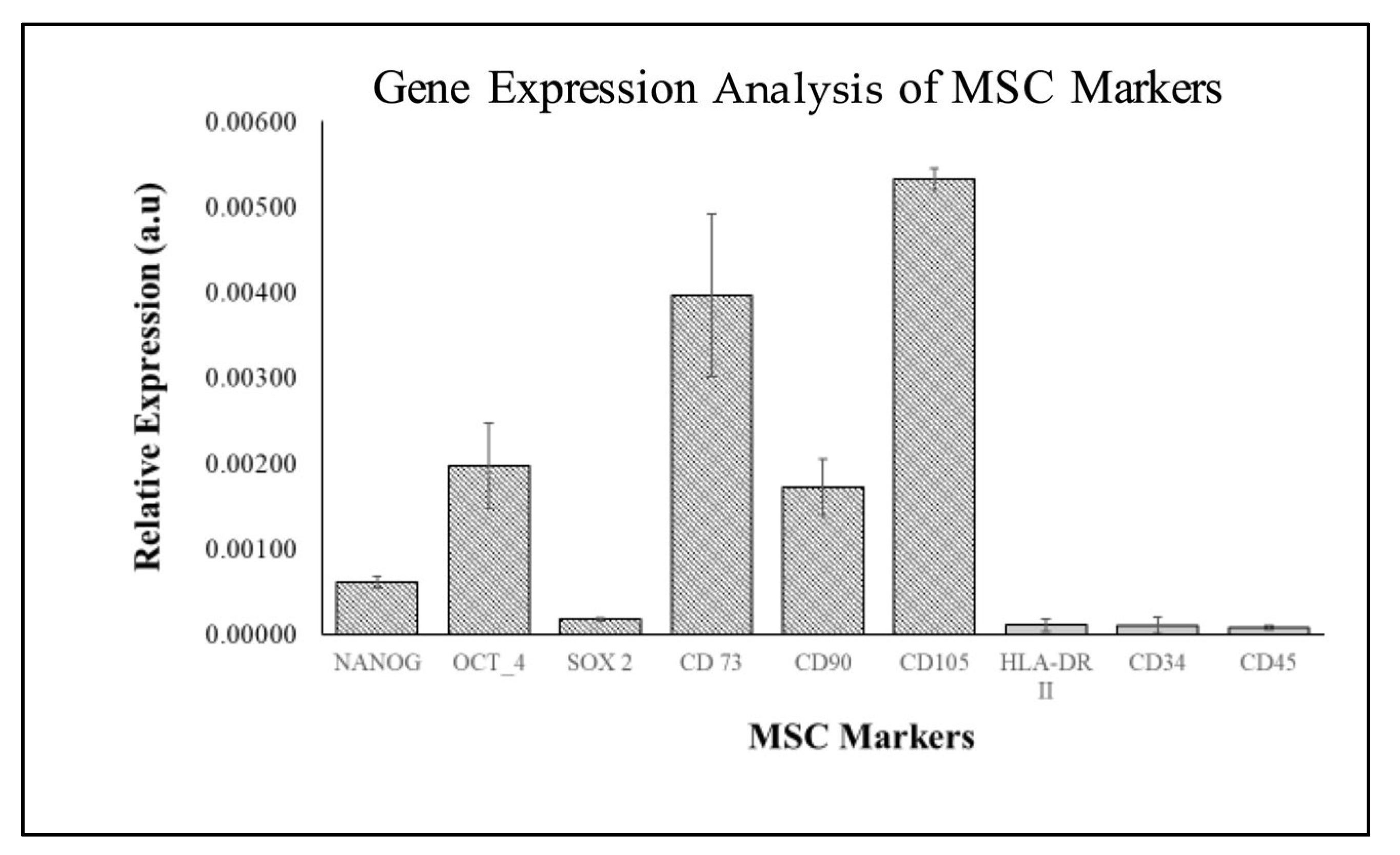

2.3. Characterization of WJMSC

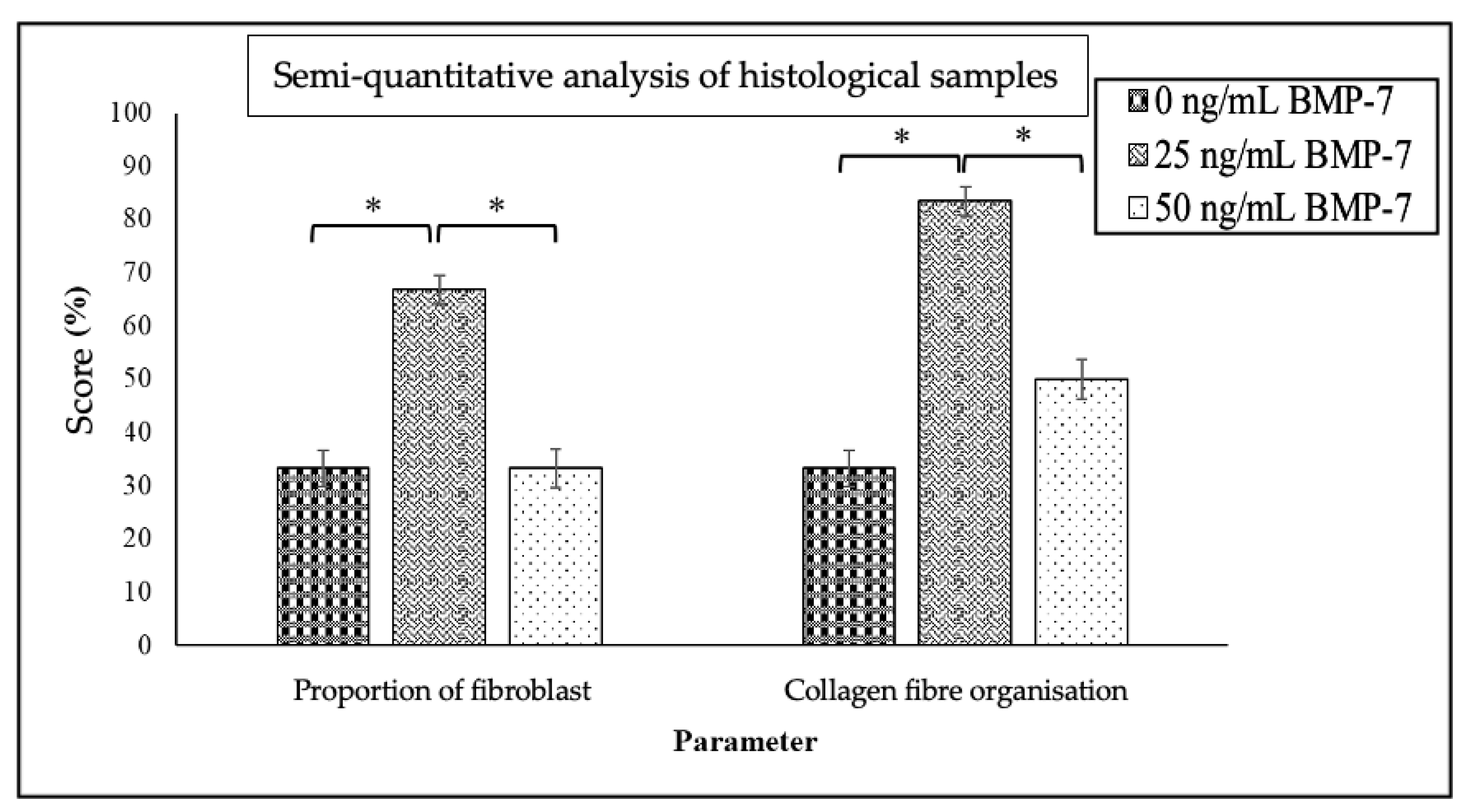

2.4. Histological Analysis of Repopulated DHDP with and Without BMP-7

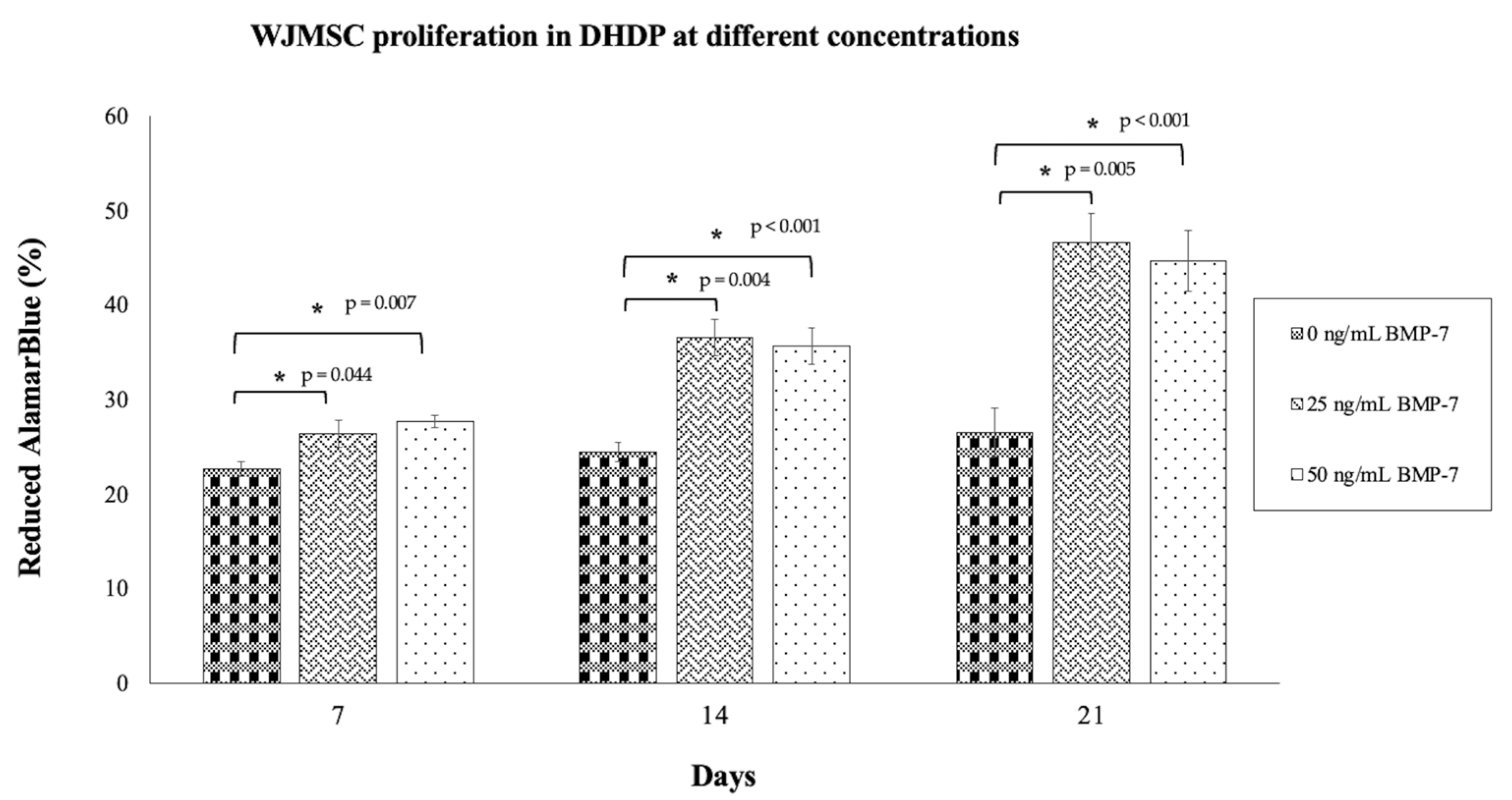

2.5. Proliferation of WJMSCs on DHDP

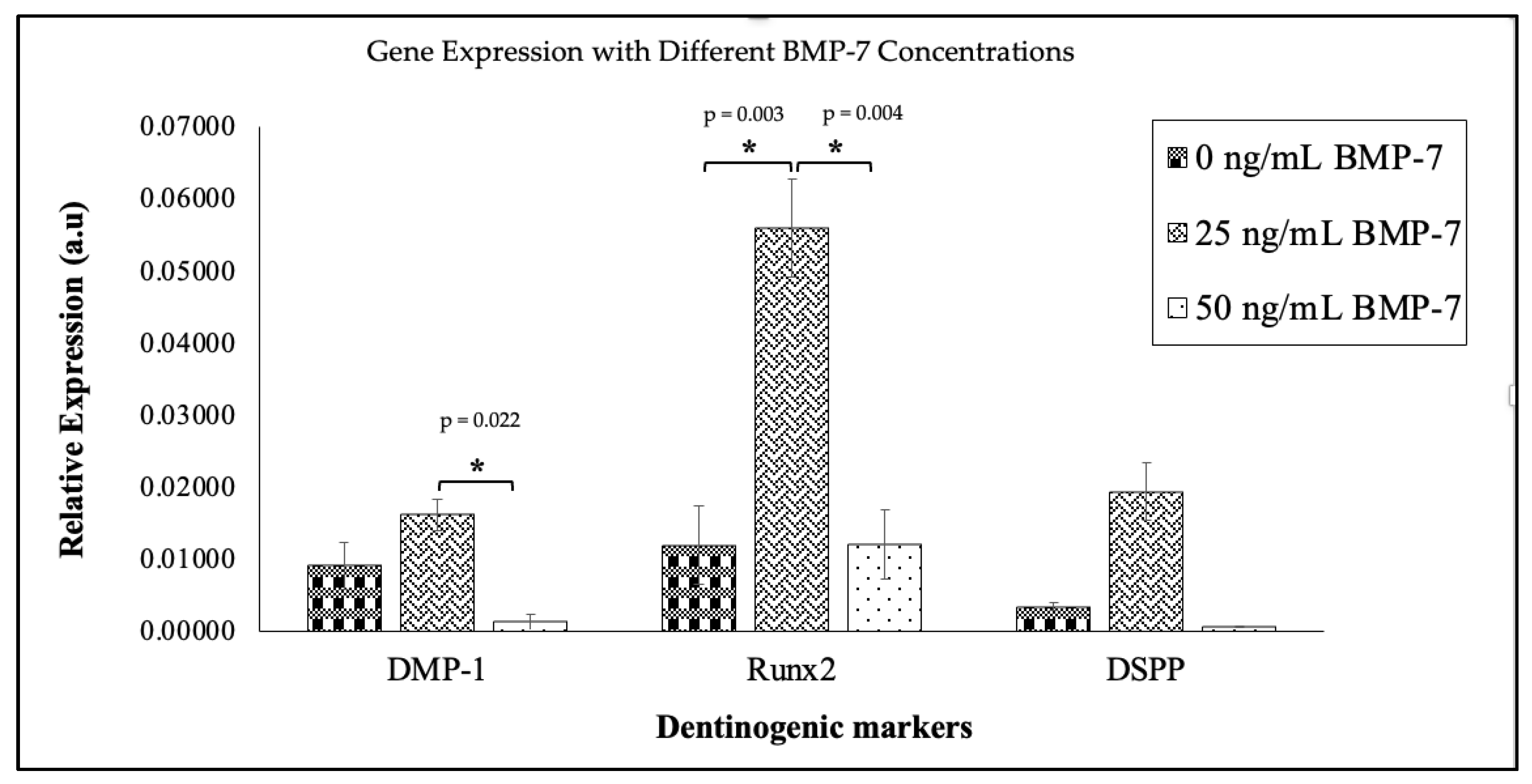

2.6. Expression of Dentinogenic Markers in Repopulated DHDP

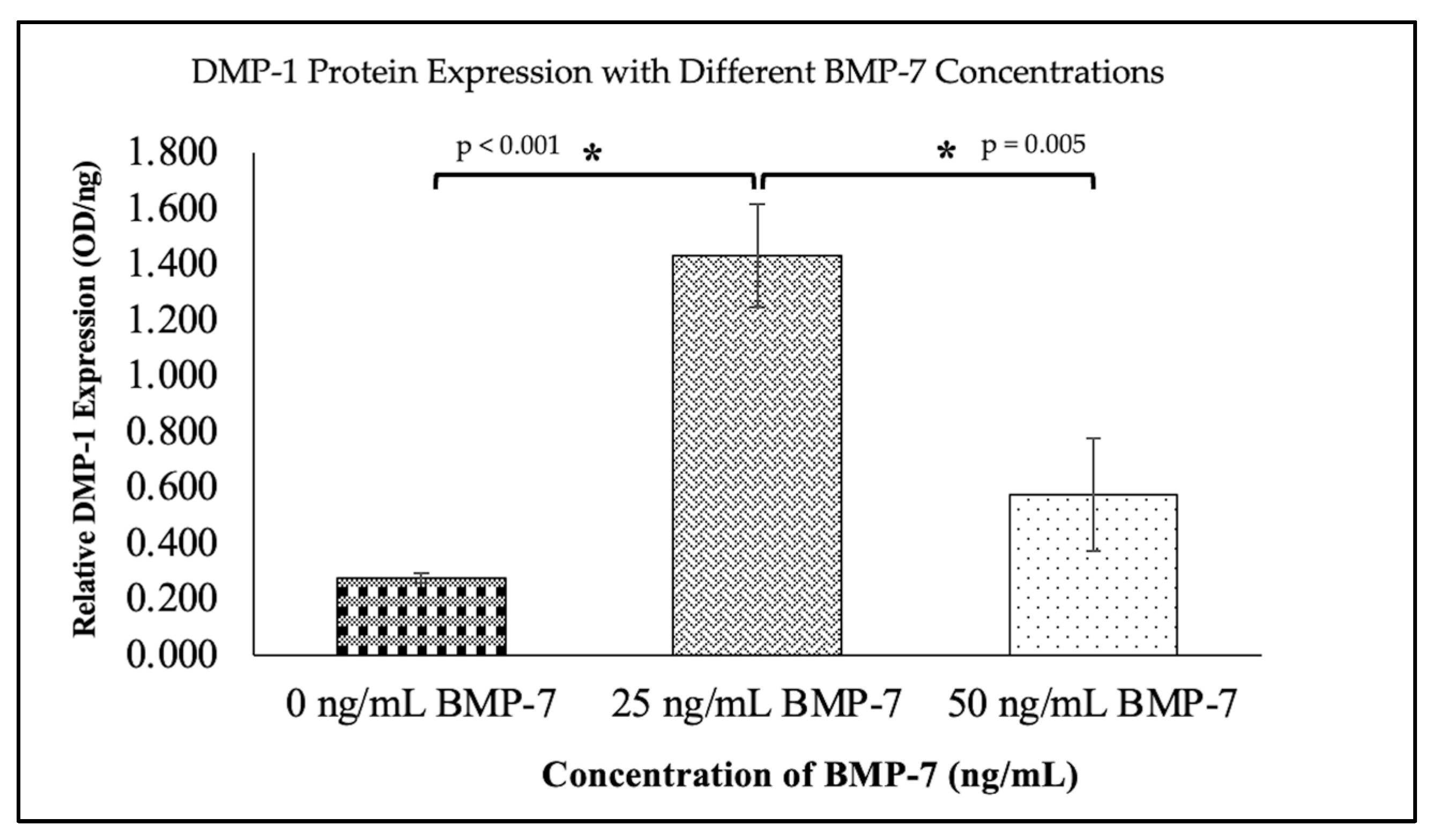

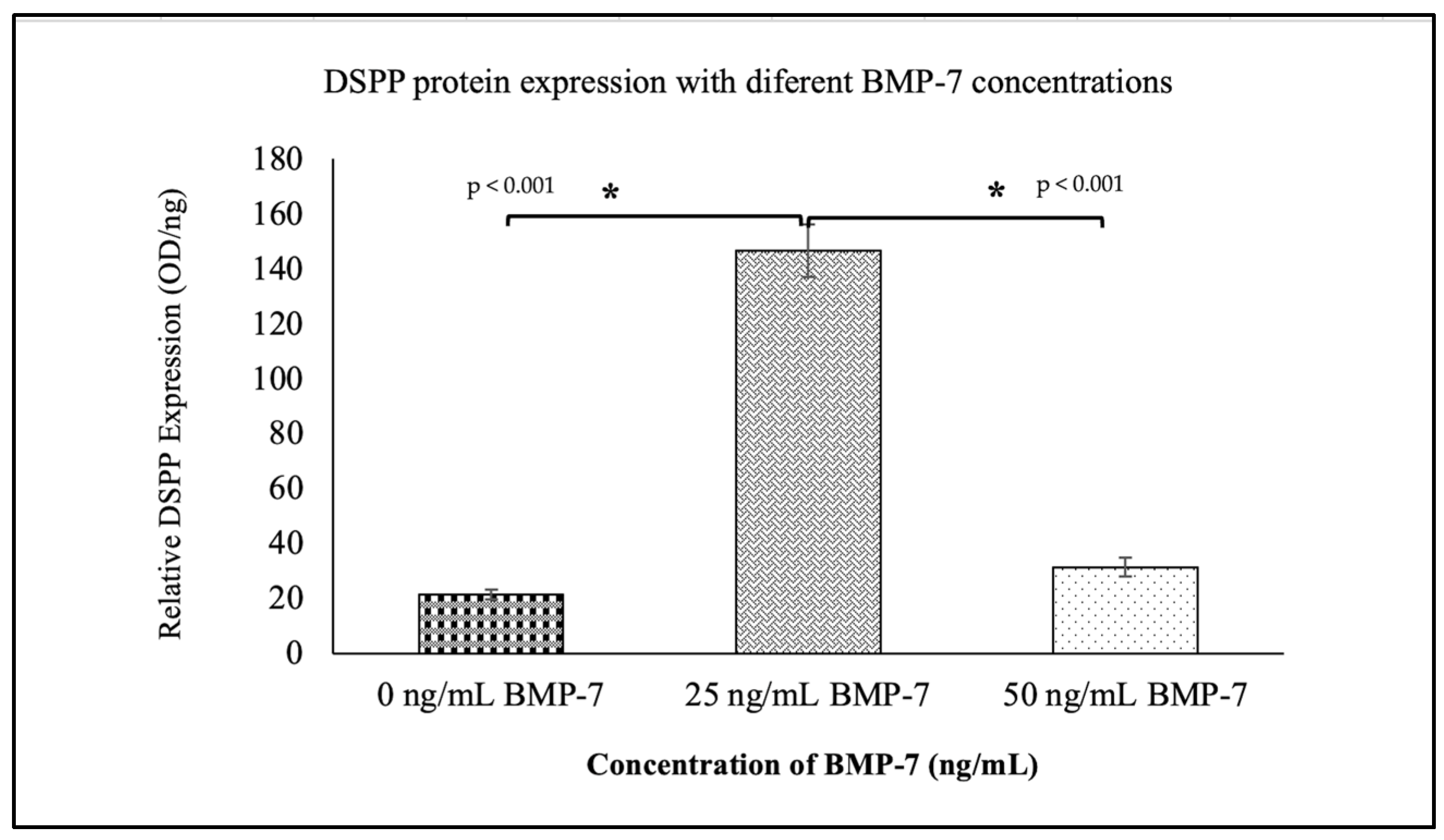

2.7. Expression of Dentinogenic Proteins in WJMSCs Cultured on DHDP with and Without BMP-7

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Optimization of BMP-7 Concentration (MTT Assay)

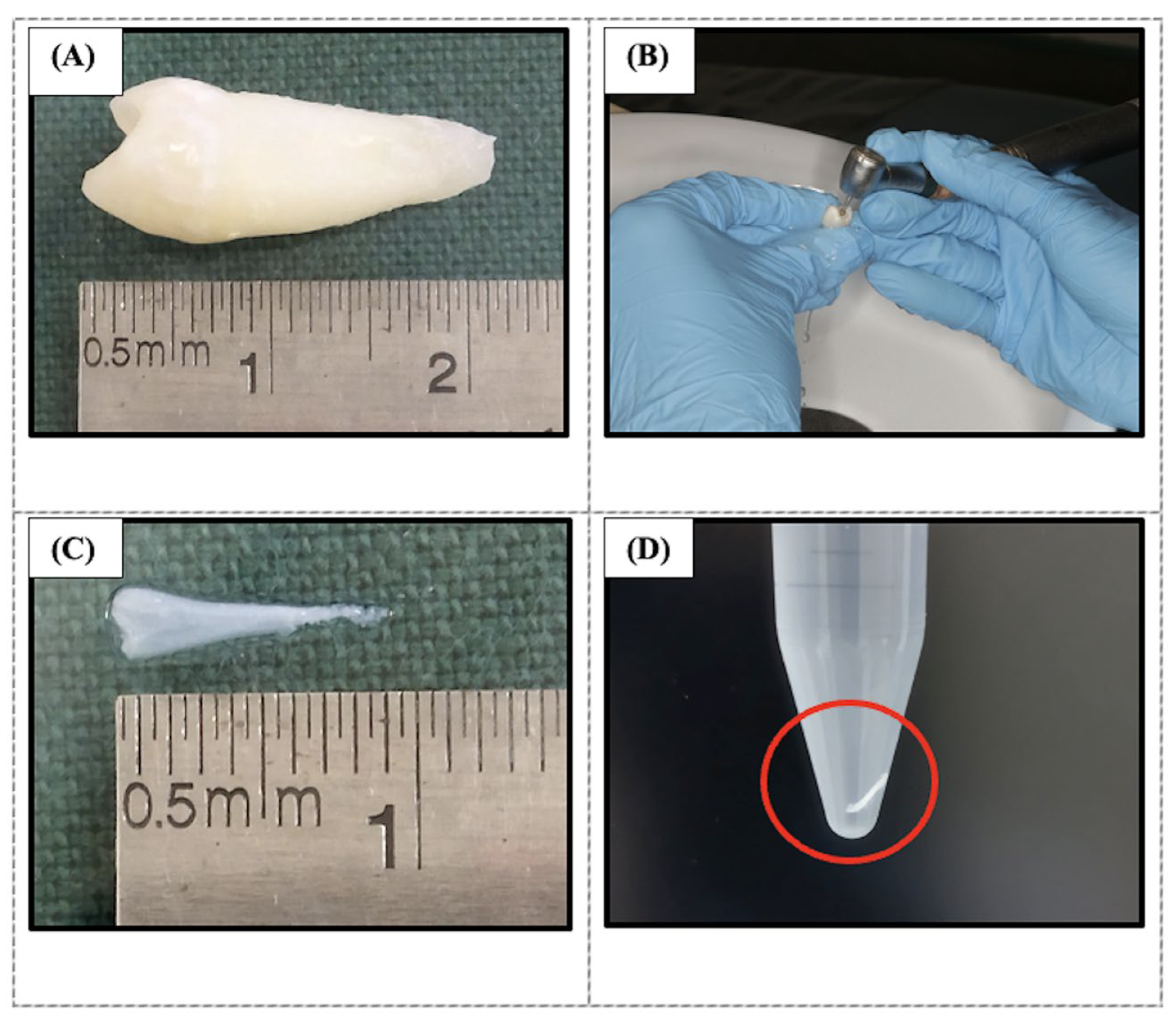

4.2. Decellularization of Human Dental Pulp

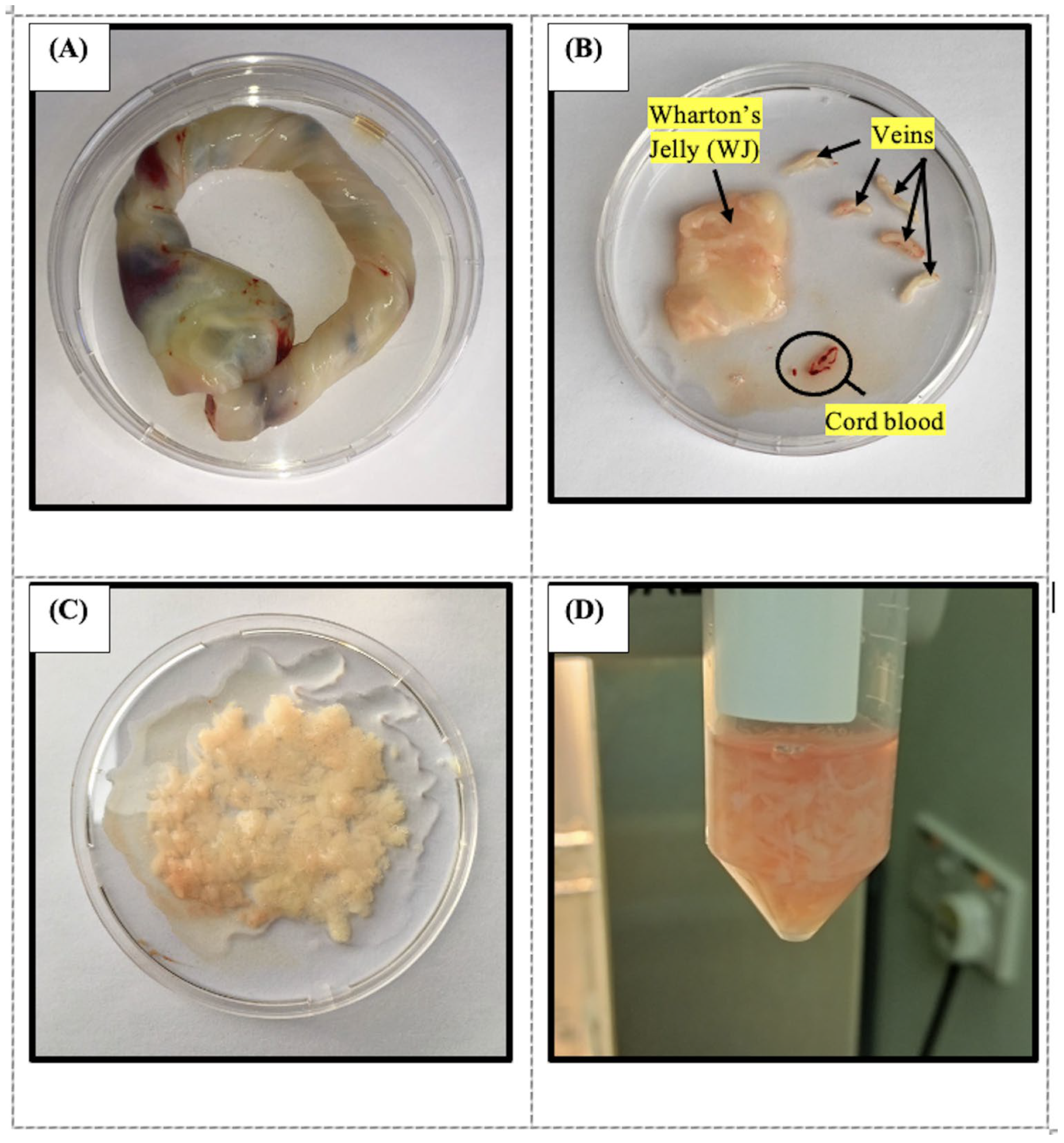

4.3. Wharton’s Jelly Mesenchymal Stem Cells Isolation and Culture

4.4. Characterization of WJMSCs

4.5. Repopulation of Decellularized Pulp Tissues with WJMSC

4.6. Cell Proliferation Assay

4.7. Histological and Semi-Quantitative Analysis

- Score 0: No fibroblasts;

- Score 1: Presence of fibroblasts (spindle-shaped cells).

- Score 0: Loose arrangement of collagen fibres (loosely arranged and interwoven in all directions);

- Score 1: Dense (clearly arranged with collagen fibres forming collagen lamellae) [88].

4.8. Gene Expression Analysis

- ΔCq control = Data quantification reading GADPH

- ΔCq sample = Data quantification reading of each primer (DSPP, DMP-1, and Runx2)

4.9. Protein Expression Analysis

4.10. Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| BMP-7 | Bone morphogenetic protein 7 |

| DHDP | Decellularized human dental pulp |

| DPSC | Dental pulp stem cell |

| DSPP | Dentin sialophosphoprotein |

| DMP-1 | Dentin matrix acidic phosphoprotein 1 |

| GADPH | Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase |

| ECM | Extracellular matrix |

| GDM | Gestational diabetes mellitus; |

| MSC | Mesenchymal stem cell |

| RET | Regenerative endodontic therapy |

| RCT | Root canal treatment |

| SDS | Sodium dodecyl sulfate |

| VEGF | Vascular endothelial growth factor |

| WJMSC | Wharton’s jelly mesenchymal stem cell |

References

- Nakashima, M.; Iohara, K.; Murakami, M.; Nakamura, H.; Sato, Y.; Ariji, Y.; Matsushita, K. Pulp regeneration by transplantation of dental pulp stem cells in pulpitis: A pilot clinical study. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2017, 8, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galler, K.M.; Krastl, G.; Simon, S.; Van Gorp, G.; Meschi, N.; Vahedi, B.; Lambrechts, P. European Society of Endodontology position statement: Revitalization procedures. Int. Endod. J. 2016, 49, 717–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burns, L.E.; Kim, J.; Wu, Y.; Alzwaideh, R.; McGowan, R.; Sigurdsson, A. Outcomes of primary root canal therapy: An updated systematic review of longitudinal clinical studies published between 2003 and 2020. Int. Endod. J. 2022, 55, 714–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ng, Y.-L.; Mann, V.; Gulabivala, K. A prospective study of the factors affecting outcomes of non-surgical root canal treatment: Part 2: Tooth survival. Int. Endod. J. 2011, 44, 610–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rao, V.; Shah, A.G.; Desai, E.C.; Agrawal, H.; Patel, K.; Patel, P.; Kothari, A.; Agrawal, D.; Jain, R.; Bharti, R. Outcomes of single-visit versus multi-visit root canal therapy: A meta-analysis of success rates. J. Endod. Res. 2025, 15, 62–67. [Google Scholar]

- Elemam, R.F.; Pretty, I. Comparison of the success rate of endodontic treatment and implant treatment. ISRN Dent. 2011, 2011, 640509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majno, G.; Joris, I. Cells, Tissues, and Disease: Principles of General Pathology, 2nd ed.; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, V.; Abbas, A.; Aster, J. Robbins and Cotran Pathologic Basis of Diseases, 10th ed.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2020; p. 1450. [Google Scholar]

- American Association of Endodontists. AAE Clinical Considerations for a Regenerative Procedure [Internet]. 2021. Available online: https://www.aae.org/specialty/wp-content/uploads/sites/2/2021/08/ClinicalConsiderationsApprovedByREC062921.pdf. (accessed on 29 October 2025).

- Yan, H.; De Deus, G.; Kristoffersen, I.M.; Wiig, E.; Reseland, J.E.; Johnsen, G.F.; Silva, E.J.N.L.; Haugen, H.J. Regenerative Endodontics by Cell Homing: A Review of Recent Clinical Trials. J. Endod. 2023, 49, 4–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, G.; Ricucci, D.; Gibbs, J.L.; Lin, L.M. Histological Findings of Revascularized/Revitalized Immature Permanent Molar with Apical Periodontitis Using Platelet-Rich Plasma. J. Endod. 2013, 39, 138–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, G.T.; Garcia-Godoy, F. Missing Concepts in De Novo Pulp Regeneration. J. Dent. Res. 2014, 93, 717–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goyal, A.; Nikhil, V.; Jha, P. Regenerative endodontic treatment in immature teeth: A meta-analysis of clinical outcomes. J. Endod. 2017, 43, 406–416. [Google Scholar]

- Chrepa, V.; Austah, O.; Diogenes, A. Clinical outcomes of immature teeth treated with regenerative endodontic procedures: A retrospective cohort study. J. Endod. 2020, 46, 1074–1084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, I.K.; Kim, S.G.; Kim, J. Clinical outcomes of regenerative endodontic treatment in immature permanent teeth: A retrospective study. J. Korean Acad. Pediatr. Dent. 2021, 48, 449–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Wang, Y.; Chen, X. Success rates of regenerative endodontic procedures in mature permanent teeth: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Oral. Health Prev. Dent. 2023, 21, 141–152. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Zhang, S.; Zhang, W.; Li, Y.; Ren, L.; Deng, H.; Yin, X.; Gao, X.; Pan, S.; Niu, L. Human Umbilical Cord Mesenchymal Stem Cell Differentiation into Odontoblast-Like Cells and Endothelial Cells: A Potential Cell Source for Dental Pulp Tissue Engineering. Front. Physiol. 2020, 11, 593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garzon, I.; Perez-Kohler, B.; Garrido-Gomez, J.; Carriel, V.; Nieto-Aguilar, R.; Martin-Piedra, M.A.; Garcia-Hondubilla, N.; Bujan, J.; Campos, A.; Alaminos, M. Evaluation of the cell viability of human Wharton’s jelly stem cells for use in cell therapy. Tissue Eng. Part C Methods 2012, 18, 408–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Romanov, Y.A.; Svintsitskaya, V.A.; Smirnov, V.N. Searching for alternative sources of postnatal human mesenchymal stem cells: Candidate MSC-like cells from umbilical cord. Stem Cells 2003, 21, 105–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charitos, I.A.; Ballini, A.; Cantore, S.; Boccellino, M.; Di Domenico, M.; Borsani, E.; Nocini, R.; Di Cosola, M.; Santacroce, L.; Bottalico, L. Stem cells: A historical review about biological, religious, and ethical issues. Stem Cells Int. 2021, 2021, 9978837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marino, L.; Castaldi, M.A.; Rosamilio, R.; Ragni, E.; Vitolo, R.; Fulgione, C.; Castaldi, S.G.; Serio, B.; Bianco, R.; Guida, M.; et al. Mesenchymal stem cells from the Wharton’s jelly of the human umbilical cord: Biological properties and therapeutic potential. Int. J. Stem Cells 2019, 12, 218–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, P.; Maurya, D.K. Wharton’s jelly mesenchymal stem cells: Future regenerative medicine for clinical applications in mitigation of radiation injury. World J. Stem Cells 2024, 16, 742–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, D.J.; Miguez, P.; Kwon, J.; Daniel, R.; Padilla, R.; Min, S.; Zalal, R.; Ko, C.C.; Shin, H.W. Decellularized pulp matrix as scaffold for mesenchymal stem cell-mediated bone regeneration. J. Tissue Eng. 2020, 11, 2041731420981672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, J.S.; Takimoto, K.; Jeon, M.; Vadakekalam, J.; Ruparel, N.B.; Diogenes, A. Decellularized Human Dental Pulp as a Scaffold for Regenerative Endodontics. J. Dent. Res. 2017, 96, 640–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, L.; Ma, J.; Mu, R.; Zhu, R.; Chen, F.; Wei, X.; Shi, X.; Zang, S.; Jin, L. Bone morphogenetic protein 7 promotes odontogenic differentiation of dental pulp stem cells in vitro. Life Sci. 2018, 202, 175–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cecchi, S.; Bennet, S.J.; Arora, M. Bone morphogenetic protein-7: Review of signalling and efficacy in fracture healing. J. Orthop. Transl. 2016, 4, 28–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matoug-Elwerfelli, M.; Duggal, M.; Nazzal, H.; Esteves, F.; Raïf, E. A Biocompatible Decellularized Pulp Scaffold for Regenerative Endodontics. Int. Endod. J. 2018, 51, 663–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elnawam, H.; Thabet, A.; Mobarak, A.; Abdallah, A.; Elbackly, R. Preparation and characterization of bovine dental pulp-derived extracellular matrix hydrogel for regenerative endodontic applications: An in vitro study. BMC Oral Health 2024, 24, 1281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Faulk, D.M.; Carruthers, C.A.; Warner, H.J.; Kramer, C.R.; Reing, J.E.; Zhang, L.; D’Amore, A.; Badylak, S.F. The effect of detergents on the basement membrane complex of a biologic scaffold material. Acta Biomater. 2014, 10, 183–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, P.; Nakamura, N.; Kimura, T.; Nam, K.; Fujisato, T.; Funamoto, S.; Higami, Y.; Kishida, A. Decellularized porcine aortic intima-media as a potential cardiovascular biomaterial. Interact. Cardiovasc. Thorac. Surg. 2015, 21, 189–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Rao, Z.; Zhao, Y.; Xu, Y.; Chen, L.; Shen, Z.; Bai, Y.; Lin, Z.; Huang, Q. A Decellularized Matrix Hydrogel Derived from Human Dental Pulp Promotes Dental Pulp Stem Cell Proliferation, Migration, and Induced Multidirectional Differentiation In Vitro. J. Endod. 2020, 46, 1438–1447.e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yazdanian, M.; Arefi, A.H.; Alam, M.; Abbasi, K.; Tebyaniyan, H.; Tahmasebi, E.; Ranjbar, R.; Seifalian, A.; Rahbar, M. Decellularized and biological scaffolds in dental and craniofacial tissue engineering: A comprehensive overview. J. Mat. Res. Tech. 2021, 15, 1217–1251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, I.H.; Jeon, M.; Cheon, K.; Kim, S.H.; Jung, H.S.; Shin, Y.; Kang, C.M.; Kim, S.O.; Choi, H.J.; Lee, H.S.; et al. In Vivo Evaluation of Decellularized Human Tooth Scaffold for Dental Tissue Regeneration. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 8472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dominici, M.; Le Blanc, K.; Mueller, I.; Slaper-Cortenbach, I.; Marini, F.; Krause, D.; Deans, R.; Keating, A.; Prockop, D.J.; Horwitz, E. Minimal criteria for defining multipotent mesenchymal stromal cells. The International Society for Cellular Therapy position statement. Cytotherapy 2006, 8, 315–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pierantozzi, E.; Gava, B.; Manini, I.; Roviello, F.; Marotta, G.; Chiavarelli, M.; Sorrentino, V. Pluripotency regulators in human mesenchymal stem cells: Expression of NANOG but not of OCT-4 and SOX-2. Stem Cells Dev. 2011, 20, 915–923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, W.; Zhang, F.; Zeng, X.; He, F.; Shang, G.; Guo, T.; Wang, Q.; Wu, J.; Li, T.; Zhong, Z.Z.; et al. A GMP-compliant manufacturing method for Wharton’s jelly-derived mesenchymal stromal cells. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2024, 15, 131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panwar, U.; Mishra, K.; Patel, P.; Bharadva, S.; Vaniawala, S.; Shah, A.; Vundinti, B.R.; Kothari, S.L.; Ghosh, K. Assessment of Long-Term in vitro Multiplied Human Wharton’s Jelly-Derived Mesenchymal Stem Cells prior to Their Use in Clinical Administration. Cells Tissues Organs 2021, 210, 239–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdul Rahman, R.; Abdul Razak, F.; Mohd Yunus, M.H. Characterization of Wharton’s jelly-derived mesenchymal stem cells by gene expression profiling. Sains Malays. 2019, 48, 941–952. [Google Scholar]

- Abouelnaga, H.; El-Khateeb, D.; Moemen, Y.; El-Fert, A.; Elgazzar, M.; Khalil, A. Characterization of mesenchymal stem cells isolated from Wharton’s jelly of the human umbilical cord. Egypt. Liver J. 2022, 12, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, G.Y.; Choi, G.T.; Park, J.; Lee, J.; Do, J.T. Comparative Analysis of Porcine Adipose- and Wharton’s Jelly-Derived Mesenchymal Stem Cells. Animals 2023, 13, 2947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Guo, H.; Shi, C.; Sun, H. BMP signaling in the development and regeneration of tooth roots: From mechanisms to applications. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2023, 11, 1272201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Goldman, G.; MacDougall, M.; Chen, S. BMP Signaling Pathway in Dentin Development and Diseases. Cells 2022, 11, 2216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amir, M.; Jeevithan, L.; Barkat, M.; Fatima, S.H.; Khan, M.; Israr, S.; Naseer, F.; Fayyaz, S.; Elango, J.; Wu, W.; et al. Advances in Regenerative Dentistry: A Systematic Review of Harnessing Wnt/β-Catenin in Dentin-Pulp Regeneration. Cells 2024, 13, 1153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuroda, Y.; Kawai, T.; Goto, K.; Matsuda, S. Clinical application of injectable growth factor for bone regeneration: A systematic review. Inflamm. Regen. 2019, 39, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qin, W.; Zhu, H.; Chen, L.; Yang, X.; Huang, Q.; Lin, Z. Dental pulp cells that express adeno-associated virus serotype 2-mediated BMP-7 gene enhanced odontoblastic differentiation. Dent. Mater. J. 2014, 33, 656–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, S.G.; Zhou, J.; Solomon, C.; Zheng, Y.; Suzuki, T.; Chen, M.; Song, S.; Jiang, N.; Cho, S.; Mao, J.J. Effects of growth factors on dental stem/progenitor cells. Dent. Clin. N. Am. 2012, 56, 563–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toth, F.; Tozser, J.; Hegedus, C. Effect of Inducible BMP-7 Expression on the Osteogenic Differentiation of Human Dental Pulp Stem Cells. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 6182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Omi, M.; Kulkarni, A.K.; Raichur, A.; Fox, M.; Uptergrove, A.; Zhang, H.; Mishina, Y. BMP-Smad Signaling Regulates Postnatal Crown Dentinogenesis in Mouse Molar. JBMR Plus 2019, 4, e10249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, L.; Wang, S.; Zhang, F.; Huang, L.; Xie, Q.; Zhang, C. Mechanisms of BMP7-mediated promotion of proliferation and odontogenic differentiation in human mesenchymal stem cells derived from Wharton’s Jelly. Tissue Eng. Part A 2019, 5, 1130–1141. [Google Scholar]

- Qin, X.; Wang, Q.; Wang, J.; Bai, W.; Cao, H.; Mo, W. BMP7 induces odontoblastic differentiation via BMP/Smad and MAPK pathways in human dental pulp stem cells. J. Endod. 2016, 42, 278–287. [Google Scholar]

- Fan, Z.; Mao, A.; Fan, C.; Li, Q.; Bi, X. Comparative analysis of BMP2 versus BMP7 in regeneration of dentin-pulp complex: Signaling pathways and functional outcomes. J. Tissue Eng. Regen. Med. 2015, 9, 631–641. [Google Scholar]

- Meurer, S.K.; Esser, M.; Tihaa, L.; Weiskirchen, R. BMP-7/TGF-β1 signalling in myoblasts: Components involved in signalling and BMP-7-dependent blockage of TGF-β-mediated CTGF expression. Eur. J. Cell Biol. 2012, 91, 450–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, B.; Wei, A.; Whittaker, S.; Williams, L.A.; Tao, H.; Ma, D.D.F.; Diwan, A.D. The role of BMP-7 in chondrogenic and osteogenic differentiation of human bone marrow multipotent mesenchymal stromal cells in vitro. J. Cell Biochem. 2009, 109, 406–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, C.; Liang, Q.; Xu, X.; Liu, X.; Gao, X.; Li, M.; Yang, J.; Xing, X.; Huang, H.; Tang, Q. Bone morphogenetic protein 7 mediates stem cells migration and angiogenesis: Therapeutic potential for endogenous pulp regeneration. Int. J. Oral Sci. 2022, 14, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paulsen, M.; Legewie, S.; Eils, R.; Karaulanov, E.; Niehrs, C. Negative feedback in the bone morphogenetic protein 4 (BMP4) synexpression group governs its dynamic signaling range and canalizes development. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2011, 108, 10202–10207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deschaseaux, F.; Christan, C.; Ring, J.; Ringe, K. Dose-dependent responses of human mesenchymal stem cells to BMP-7: Proliferation plateau due to receptor saturation. PLoS ONE 2009, 4, e5682. [Google Scholar]

- Langenbach, F.; Handschel, J. Effects of BMP-2 concentrations on proliferation and differentiation of human mesenchymal stem cells. Biomaterials 2007, 28, 2871–2879. [Google Scholar]

- Mendelson, A.; Kang, H.; Atanassova, N.; Kulkarni, R.N. Negative feedback regulation of BMP signaling by inhibitory Smads in mesenchymal stem cells. Stem Cells Dev. 2013, 22, 1175–1185. [Google Scholar]

- Nakashima, K.; Zhou, X.; Kunkel, G.; Zhang, Z.; Deng, J.-M.; Behringer, R.R.; de Crombrugghe, B. The novel zinc finger-containing transcription factor osterix is required for osteoblast differentiation and bone formation. Cell 2002, 108, 17–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, G.; Deng, C.; Li, Y.P. TGF-β and BMP signaling in osteoblast differentiation and bone formation. Int. J. Biol. Sci. 2012, 8, 272–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conolly, R.B.; Lutz, W.K. Nonmonotonic dose-response relationships: Mechanistic basis, kinetic modeling, and implications for risk assessment. Toxicol. Sci. 2004, 77, 151–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, F.; Bi, D.; Cheng, C.; Ma, S.; Liu, Y.; Cheng, K. Bone morphogenetic protein 7 enhances the osteogenic differentiation of human dermal-derived CD105+ fibroblast cells through the Smad and MAPK pathways. Int. J. Mol. Med. 2019, 43, 37–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landin, M.A.; Shabestari, M.; Babaie, E.; Reseland, J.E.; Osmundsen, H. Gene expression profiling during murine tooth development. Front. Genet. 2012, 3, 139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pascal, L.E.; True, L.D.; Campbell, D.S.; Deutsch, E.W.; Risk, M.; Coleman, I.M.; Eichner, L.J.; Nelson, P.S.; Liu, A.Y. Correlation of mRNA and protein levels: Cell type-specific gene expression in the human prostate. BMC Genom. 2008, 9, 246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vogel, C.; Marcotte, E.M. Insights into the regulation of protein abundance. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2012, 13, 227–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wan, T.; Nie, L.; Xiang, A.B.C.; Dai, T.; Wang, Y.; Gu, M. microRNA-21 regulates the odontogenic differentiation of human dental pulp cells. J. Endod. 2014, 40, 1972–1977. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, J.; Wan, C.; Jiang, Y.; Li, X.; Zhu, Y. MicroRNA-221 suppresses the odontogenic differentiation of human dental pulp stem cells by targeting dentin sialophosphoprotein. Arch. Oral Biol. 2017, 82, 10–17. [Google Scholar]

- Glisovic, T.; Bachorik, J.L.; Yong, J.; Dreyfuss, G. RNA-binding proteins and post-transcriptional gene regulation. FEBS Lett. 2008, 582, 1977–1986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gygi, S.P.; Rochon, Y.; Franza, B.R.; Aebersold, R. Correlation between protein and mRNA abundance in yeast. Mol. Cell Biol. 1999, 19, 1720–1730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Beyer, A.; Aebersold, R. On the dependency of cellular protein levels on mRNA abundance. Cell 2016, 165, 535–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Liu, C.; Zhang, W. Roles of microRNAs in odontogenesis. Curr. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2016, 11, 381–391. [Google Scholar]

- Arora, S.; Cooper, P.R.; Ratnayake, J.T.; Friedlander, L.T.; Rizwan, S.B.; Seo, B.; Hussaini, H.M. A critical review of in vitro research methodologies used to study mineralization in human dental pulp cell cultures. Int. Endod. J. 2022, 55 (Suppl. S1), 3–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eischen-Loges, M.; Tahmasebi Birgani, Z.; Alaoui Selsouli, Y.; Eijssen, L.; Rho, H.; Sthijns, M.; van Griensven, M.; LaPointe, V.; Habibović, P. A roadmap of osteogenic differentiation in human mesenchymal stem cells assessed by protein multiplex analysis. Cells Mater. 2024, 47, 170–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Y.; Qu, Y.; Hu, X.; Zhao, J.; Xu, S.; Zheng, L.; Liang, X. E7 peptide modified poly(ε-caprolactone)/silk fibroin/octacalcium phosphate nanofiber membranes with “recruitment-osteoinduction” potentials for effective guided bone regeneration. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2025, 305 Pt 1, 140862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crapo, P.M.; Gilbert, T.W.; Badylak, S.F. An overview of tissue and whole organ decellularization processes. Biomaterials 2011, 32, 3233–3243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown, B.N.; Valentin, J.E.; Stewart-Akers, A.M.; McCabe, G.P.; Badylak, S.F. Macrophage phenotype and remodeling outcome in response to biologic scaffold materials. Acta Biomater. 2009, 5, 36–43. [Google Scholar]

- Badylak, S.F.; Gilbert, T.W. Immune response to biologic scaffold materials. Semin. Immunol. 2008, 20, 109–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golebiowska, A.A.; Intravaia, J.T.; Sathe, V.M.; Kumbar, S.G.; Nukavarapu, S.P. Decellularized extracellular matrix biomaterials for regenerative therapies: Advances, challenges and clinical prospects. Bioact. Mater. 2023, 32, 98–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Park, S.E.; Kim, M.; Kim, H.; Kwon, J.Y.; Jeon, H.B.; Chang, J.W.; Lee, J. Safety and tolerability of Wharton’s jelly-derived mesenchymal stem cells for patients with Duchenne muscular dystrophy: A phase 1 clinical study. J. Clin. Neurol. 2025, 21, 40–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baranovskii, D.S.; Klabukov, I.D.; Arguchinskaya, N.V.; Yakimova, A.O.; Kisel, A.A.; Yatsenko, E.M.; Ivanov, S.A.; Shegay, P.V.; Kaprin, A.D. Adverse events, side effects and complications in mesenchymal stromal cell-based therapies. Stem Cell Investig. 2022, 9, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.; Yu, X.; Wang, Z.; Wang, F.; Wang, L.; Gao, H.; Chen, Y.; Zhao, W.; Jia, Z.; Yan, S.; et al. Long-term effects of the implantation of Wharton’s jelly-derived mesenchymal stem cells from the umbilical cord for newly-onset type 1 diabetes mellitus. Endocr. J. 2023, 60, 347–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, Y.Y.; Abdullah, D.; Abu Kasim, N.H.; Yazid, F.; Mahamad Apandi, N.I.; Ramanathan, A.; Soo, E.; Radzi, R.; Teh, L.A. Histological characterization of pulp regeneration using decellularized human dental pulp and mesenchymal stem cells in a feline model. Tissue Cell 2024, 90, 102484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raoof, M.; Yaghoobi, M.M.; Derakhshani, A.; Kamal-Abadi, A.M.; Ebrahimi, B.; Abbasnejad, M.; Shokouhinejad, N. A modified efficient method for dental pulp stem cell isolation. Dent. Res. J. 2014, 11, 244–250. [Google Scholar]

- Traphagen, S.B.; Fourligas, N.; Xylas, J.F.; Sengupta, S.; Kaplan, D.L.; Georgakoudi, I.; Yelick, P.C. Characterization of natural, decellularized and reseeded porcine tooth bud matrices. Biomaterials 2012, 33, 5287–5296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Datta, S.; Rameshbabu, A.P.; Bankoti, K.; Roy, M.; Gupta, C.; Jana, S.; Das, A.K.; Sen, R.; Dhara, S. Decellularized bone matrix/oleoyl chitosan derived supramolecular injectable hydrogel promotes efficient bone integration. Mater. Sci. Eng. C Mater. Biol. Appl. 2021, 119, 111604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Obut, M.; Çayönü Kahraman, N.; Sucu, S.; Keleş, A.; Arat, Ö.; Yücel Celik, O.; Bucak, M.; Cakir, A.; Şahın, D.; Yücel, A. Comparison of Feto-Maternal Outcomes Between Emergency and Elective Cesarean Deliveries in Patients with Gestational Diabetes. Turk. J. Diabetes Obes. 2023, 7, 52–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moure, S.P.; Carrard, V.C.; Lauxen, I.S.; Manso, P.P.; Oliveira, M.G.; Martins, M.D.; Sant Ana Filho, M. Collagen and elastic fibers in odontogenic entities: Analysis using light and confocal laser microscopic methods. Open Dent. J. 2011, 5, 116–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vandesompele, J.; De Preter, K.; Pattyn, F.; Poppe, B.; Van Ory, N.; De Paepe, A.; Spelemen, F. Accurate normalization of real-time quantitative RT-PCR data by geometric averaging of multiple internal control genes. Genome Biol. 2022, 3, research0034.1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakanishi, Y.; Okada, T.; Takeuchi, N.; Kozono, N.; Senju, T.; Nakayama, K.; Nakashima, Y. Histological evaluation of tendon formation using a scaffold-free three-dimensional-bioprinted construct of human dermal fibroblasts under in vitro static tensile culture. Regen. Ther. 2019, 11, 47–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bustin, S.A.; Benes, V.; Garson, J.A.; Hellemans, J.; Huggett, J.; Kubista, M.; Mueller, R.; Nolan, T.; Pfaffl, M.W.; Shipley, G.L.; et al. The MIQE guidelines: Minimum information for publication of quantitative real-time PCR experiments. Clin. Chem. 2009, 55, 611–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Chemical Solution | Time (h) | Cycle | References | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tris-HCl buffer | 48 | 1 | Traphagen et al. (2012) [84] | |

| 1% SDS 1% Triton X-100 | 24 |  | 3 | Song et al. (2017) [24] |

| 24 | ||||

| 1% SDS 1% Triton X-100 | 24 | |||

| 24 | ||||

| 1% SDS 1% Triton X-100 | 24 | |||

| 24 | ||||

| PBS + 1% A/A | 24 | 1 | Datta et al. (2021) [85] | |

| Type of Markers | Gene | Primer Sequences (5′–3′) [Forward, F] [Reverse, R] | Fragment Length (bp) | Accession Number |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Housekeeping | GAPDH | F: CAATGACCCCTTCATTGACC R: TTGATTTTGGAGGGATCTCG | 160 | NM_002046.5 |

| Pluripotent | NANOG | F: TCCTCCTGCCTGAGTCTCTC R: ATACAGGGCTAGGCTGGTGA | 199 | NM_024865 |

| OCT-4 | F: GCAAAGCAGAAACCCTCGTG R: AACCACACTCGGACCACATC | 172 | NM_002701 | |

| SOX2 | F: ATGGGTTCGGTGGTCAAGTC R: ACATGTGAAGTCTGCTGGGG | 166 | NM_003106 | |

| MSC Positive | CD73 | F: CCAGCAGTTGAAGGTCGGAT R: CTGTCACAAAGCCAGGTCCT | 196 | NM_002526 |

| CD90 | F: TGGTGAGAAGAGCTGCTGTG R: CACACAGTGCCGCTCATTTC | 122 | NM_006288 | |

| CD105 | F: CCTACGTGTCCTGGCTCATC R: CGAAGGATGCCACAATGCTG | 174 | NM_000118 | |

| MSC Negative | HLA-DR II | F: GTCAATGTCACGTGGCTTCG R: TCCACCCTGCAGTCGTAAAC | 149 | NM_019111.5 |

| CD34 | F: CTCAGCTCAATCGCCTCCAT R: CAAGCCACCTCCCTTCTCTG | 191 | NM_001025109 | |

| CD45 | F: ATGATTGCTGCTCAGGGACC R: TCTCCCCAGTACTGAGCACA | 140 | NM_002838 |

| Gene | Primer Sequences (5′–3′) [Forward, F] [Reverse, R] | Fragment Length (bp) | Accession Number |

|---|---|---|---|

| GAPDH | F: CAATGACCCCTTCATTGACC R: TTGATTTTGGAGGGATCTCG | 160 | NM_002046.5 |

| DSPP | F: GACACCCAGAAGCTCAACCA R: CACTGCTGGGACCCTTGATT | 124 | NM_014208.3 |

| DMP-1 | F: GCACACACTCTCCCACTCAA R: CTCGCTCTGACTCTCTGCTG | 169 | NM_004407.4 |

| Runx2 | F: CTGTGGCATGCACTTTGACC R: CTTGGGTGGGTGGAGGATTC | 161 | NM_001024630.4 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ahmad Shuhaimi, N.A.; Abdullah, D.; Yazid, F.; Ng, S.L.; Mahamad Apandi, N.I.; Abdul Ghani, N.A. Dentinogenic Effect of BMP-7 on Wharton’s Jelly Mesenchymal Stem Cells Cultured in Decellularized Dental Pulp. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 11760. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311760

Ahmad Shuhaimi NA, Abdullah D, Yazid F, Ng SL, Mahamad Apandi NI, Abdul Ghani NA. Dentinogenic Effect of BMP-7 on Wharton’s Jelly Mesenchymal Stem Cells Cultured in Decellularized Dental Pulp. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2025; 26(23):11760. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311760

Chicago/Turabian StyleAhmad Shuhaimi, Nur Athirah, Dalia Abdullah, Farinawati Yazid, Sook Luan Ng, Nurul Inaas Mahamad Apandi, and Nur Azurah Abdul Ghani. 2025. "Dentinogenic Effect of BMP-7 on Wharton’s Jelly Mesenchymal Stem Cells Cultured in Decellularized Dental Pulp" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 26, no. 23: 11760. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311760

APA StyleAhmad Shuhaimi, N. A., Abdullah, D., Yazid, F., Ng, S. L., Mahamad Apandi, N. I., & Abdul Ghani, N. A. (2025). Dentinogenic Effect of BMP-7 on Wharton’s Jelly Mesenchymal Stem Cells Cultured in Decellularized Dental Pulp. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 26(23), 11760. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311760