CD74-Targeting Antibody–Drug Conjugate Enhances Immunosuppression of Glucocorticoid in Systemic Lupus Erythematosus

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

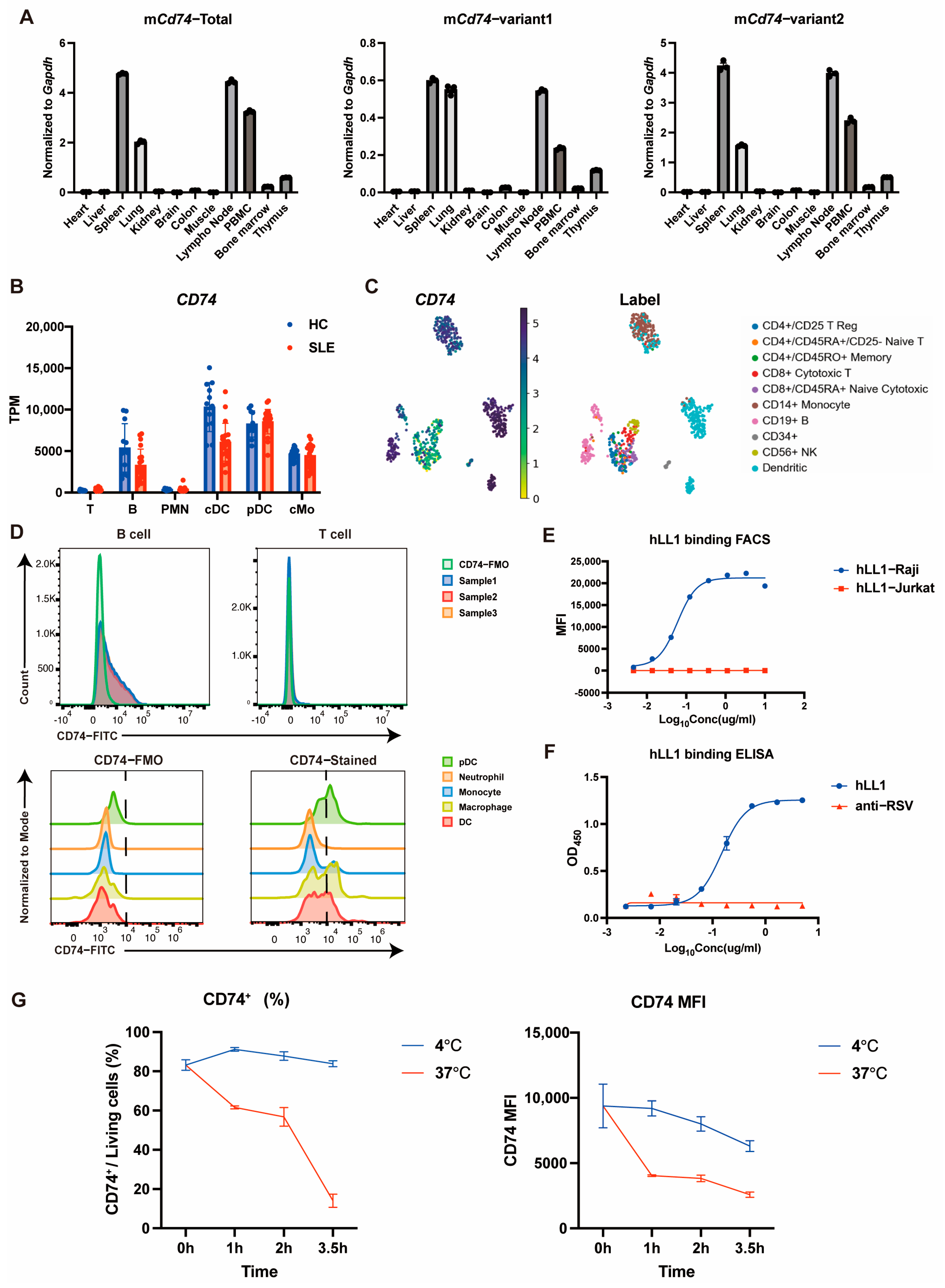

2.1. CD74 Is Highly Expressed on Certain Immune Cell Types and Capable of Rapid Internalization

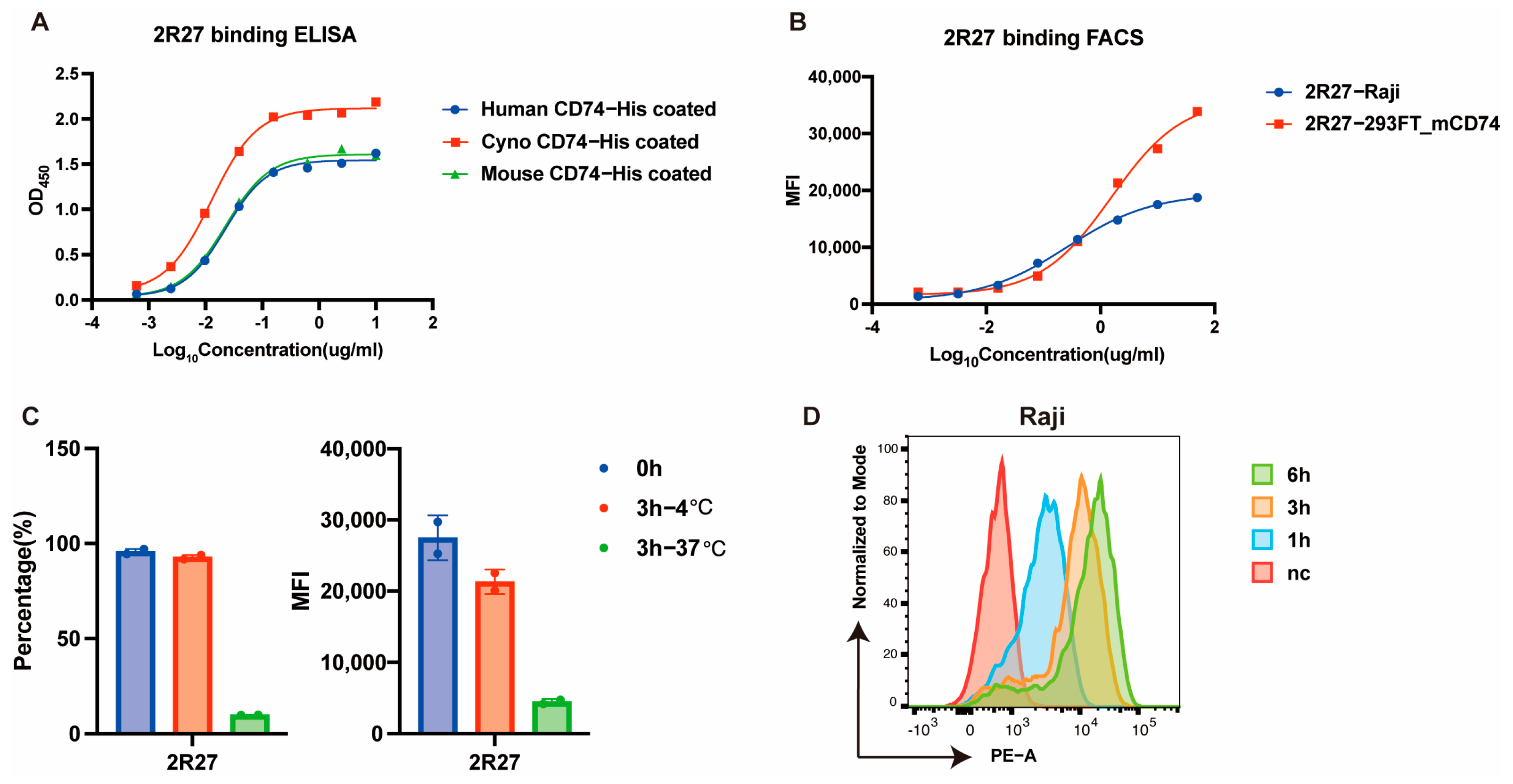

2.2. Development of a Cross-Binding and Rapidly Internalized Anti-CD74 Antibody with Rabbit Single B-Cell Screening Technology

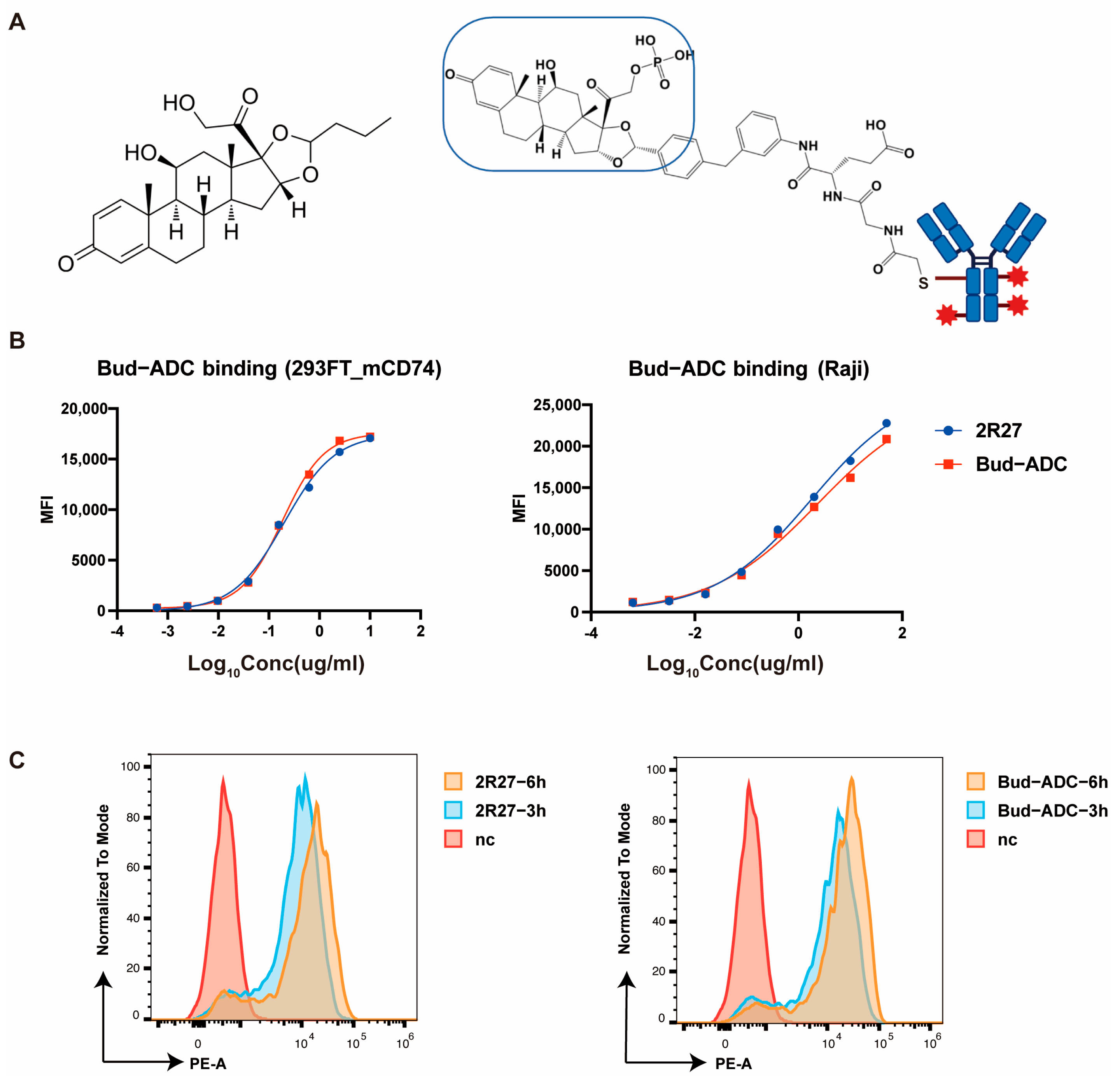

2.3. Conjugation and Evaluation of Bud-ADC

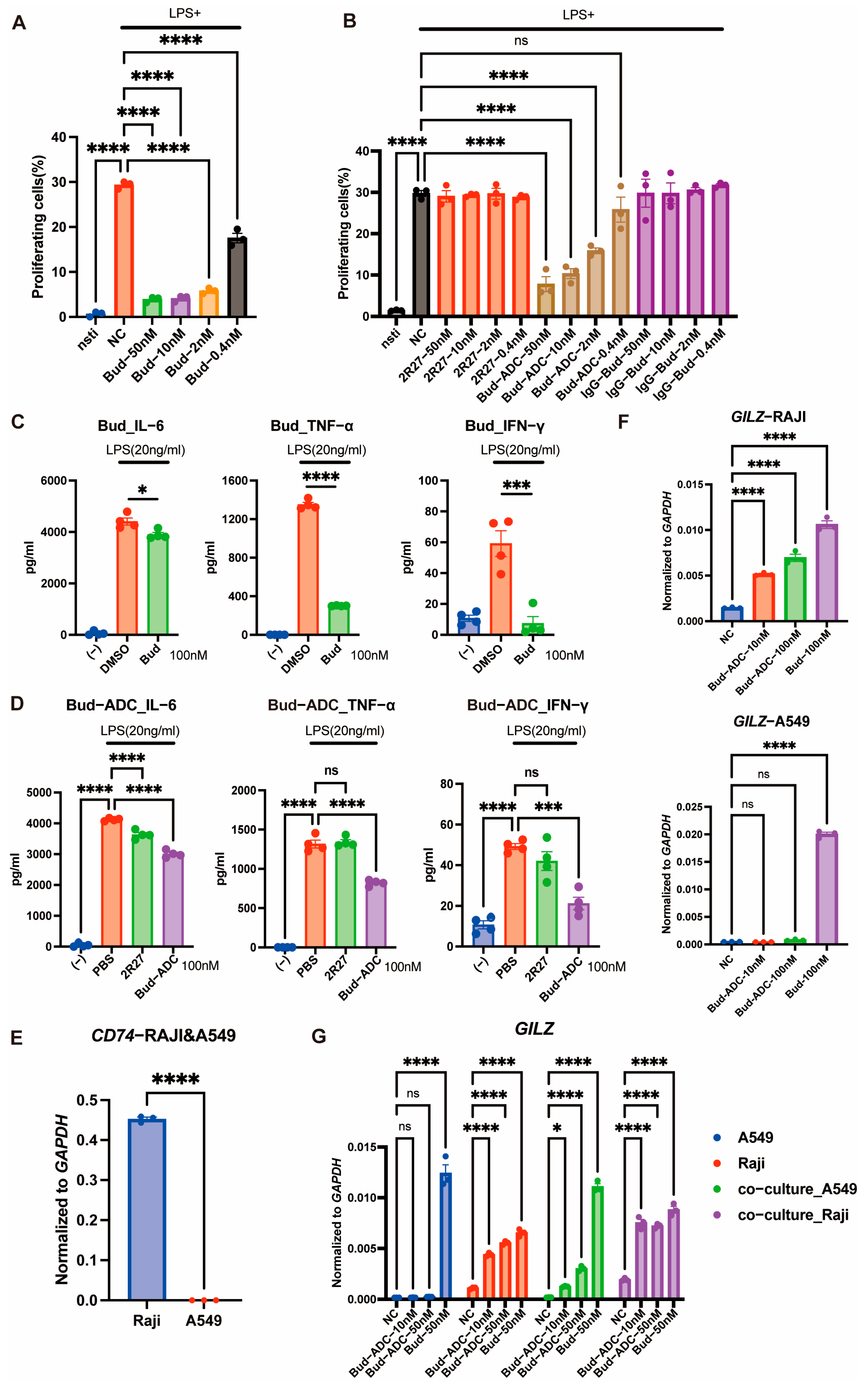

2.4. Bud-ADC Suppresses Immune Cell Activation in a CD74-Dependent Manner and Exerts a Bystander Effect

2.5. Bud-ADC Effectively Alleviates Lupus Phenotypes in a Spontaneous MRL/Lpr SLE Model

2.6. Bud-ADC Effectively Alleviates Lupus Phenotypes in an Induced BM12 SLE Model

2.7. Bud-ADC Does Not Cause Severe Toxicity in Mice Following High-Dose Administration

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Immunization of Rabbit and Screening of Anti-CD74 Monoclonal Antibody by Single Cell RT-PCR

4.2. Expression and Purification of Antibodies

4.3. Cell Culture

4.4. Conjugation and Analysis of Bud-ADC

4.5. Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay (ELISA)

4.6. Internalization Assay

4.7. Flow Cytometric Analysis FACS

4.8. Bystander Effect Assay

4.9. RNA Isolation and Quantification

4.10. MRL/Lpr Model

4.11. BM12 Model

4.12. Toxicological Analysis of Bud-ADC

4.13. Immunohistochemistry (IHC)

4.14. Statistical Analysis

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| GCs | Glucocorticoid drugs |

| SLE | Systemic lupus erythematosus |

| Bud | Budesonide |

| DCs | Dendritic cells |

| pDCs | Plasmacytoid DCs |

| MHC-II | Major Histocompatibility Complex Class II |

| IFN | Interferon |

| RT-PCR | Reverse Transcription Polymerase Chain Reaction |

| PBMCs | Peripheral Blood Mononuclear Cells |

| ELISA | Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay |

| CHO | Chinese Hamster Ovary cells |

| DAR | Drug-to-antibody ratio |

| LC-MS | Liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry |

| SEC | Size-exclusion chromatography |

| LPS | Lipopolysaccharide |

| mAb | monoclonal antibody |

| IL-6 | Interleukin-6 |

| TNF-α | Tumor Necrosis Factor-α |

| cGVHD | Chronic graft-versus-host disease |

| APCs | Antigen-presenting cells |

| TETA | Telitacicept |

References

- Fu, Z.; Li, S.; Han, S.; Shi, C.; Zhang, Y. Antibody Drug Conjugate: The “Biological Missile” for Targeted Cancer Therapy. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2022, 7, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdollahpour-Alitappeh, M.; Lotfinia, M.; Gharibi, T.; Mardaneh, J.; Farhadihosseinabadi, B.; Larki, P.; Faghfourian, B.; Sepehr, K.S.; Abbaszadeh-Goudarzi, K.; Abbaszadeh-Goudarzi, G.; et al. Antibody-Drug Conjugates (ADCs) for Cancer Therapy: Strategies, Challenges, and Successes. J. Cell. Physiol. 2019, 234, 5628–5642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dumontet, C.; Reichert, J.M.; Senter, P.D.; Lambert, J.M.; Beck, A. Antibody–Drug Conjugates Come of Age in Oncology. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2023, 22, 641–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, R.; Hu, B.; Pan, Z.; Mo, C.; Zhao, X.; Liu, G.; Hou, P.; Cui, Q.; Xu, Z.; Wang, W.; et al. Antibody-Drug Conjugates (ADCs): Current and Future Biopharmaceuticals. J. Hematol. Oncol. 2025, 18, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gogia, P.; Ashraf, H.; Bhasin, S.; Xu, Y. Antibody–Drug Conjugates: A Review of Approved Drugs and Their Clinical Level of Evidence. Cancers 2023, 15, 3886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Everts, M.; Kok, R.J.; Asgeirsdóttir, S.A.; Melgert, B.N.; Moolenaar, T.J.M.; Koning, G.A.; van Luyn, M.J.A.; Meijer, D.K.F.; Molema, G. Selective Intracellular Delivery of Dexamethasone into Activated Endothelial Cells Using an E-Selectin-Directed Immunoconjugate. J. Immunol. 2002, 168, 883–889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Svendsen, P.; Graversen, J.H.; Etzerodt, A.; Hager, H.; Røge, R.; Grønbæk, H.; Christensen, E.I.; Møller, H.J.; Vilstrup, H.; Moestrup, S.K. Antibody-Directed Glucocorticoid Targeting to CD163 in M2-Type Macrophages Attenuates Fructose-Induced Liver Inflammatory Changes. Mol. Ther. Methods Clin. Dev. 2017, 4, 50–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brandish, P.E.; Palmieri, A.; Antonenko, S.; Beaumont, M.; Benso, L.; Cancilla, M.; Cheng, M.; Fayadat-Dilman, L.; Feng, G.; Figueroa, I.; et al. Development of Anti-CD74 Antibody–Drug Conjugates to Target Glucocorticoids to Immune Cells. Bioconjug. Chem. 2018, 29, 2357–2369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, A.; Olsen, O.; D’Souza, C.; Shan, J.; Zhao, F.; Yanolatos, J.; Hovhannisyan, Z.; Haxhinasto, S.; Delfino, F.; Olson, W. Development of Novel Glucocorticoids for Use in Antibody–Drug Conjugates for the Treatment of Inflammatory Diseases. J. Med. Chem. 2021, 64, 11958–11971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobson, A.D.; Xu, J.; Welch, D.S.; Marvin, C.C.; McPherson, M.J.; Gates, B.; Liao, X.; Hollmann, M.; Gattner, M.J.; Dzeyk, K.; et al. Discovery of ABBV-154, an Anti-TNF Glucocorticoid Receptor Modulator Immunology Antibody-Drug Conjugate (iADC). J. Med. Chem. 2023, 66, 12544–12558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kvirkvelia, N.; McMenamin, M.; Gutierrez, V.I.; Lasareishvili, B.; Madaio, M.P. Human Anti-A3(IV)NC1 Antibody Drug Conjugates Target Glomeruli to Resolve Nephritis. Am. J. Physiol. Ren. Physiol. 2015, 309, F680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stoffel, B.; McPherson, M.; Hernandez, A.; Goess, C.; Mathieu, S.; Waegell, W.; Bryant, S.; Hobson, A.; Ruzek, M.; Pang, Y.; et al. Pos0365 Anti-Tnf Glucocorticoid Receptor Modulator Antibody Drug Conjugate for the Treatment of Autoimmune Diseases. Annu. Rheum. Dis. 2021, 80, 412–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graversen, J.H.; Svendsen, P.; Dagnæs-Hansen, F.; Dal, J.; Anton, G.; Etzerodt, A.; Petersen, M.D.; Christensen, P.A.; Møller, H.J.; Moestrup, S.K. Targeting the Hemoglobin Scavenger Receptor CD163 in Macrophages Highly Increases the Anti-Inflammatory Potency of Dexamethasone. Mol. Ther. 2012, 20, 1550–1558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Theocharopoulos, C.; Lialios, P.-P.; Samarkos, M.; Gogas, H.; Ziogas, D.C. Antibody-Drug Conjugates: Functional Principles and Applications in Oncology and Beyond. Vaccines 2021, 9, 1111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pal, L.B.; Bule, P.; Khan, W.; Chella, N. An Overview of the Development and Preclinical Evaluation of Antibody–Drug Conjugates for Non-Oncological Applications. Pharmaceutics 2023, 15, 1807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazar, S.; Kahlenberg, J.M. Systemic Lupus Erythematosus: New Diagnostic and Therapeutic Approaches. Annu. Rev. Med. 2023, 74, 339–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moulton, V.R.; Suarez-Fueyo, A.; Meidan, E.; Li, H.; Mizui, M.; Tsokos, G.C. Pathogenesis of Human Systemic Lupus Erythematosus: A Cellular Perspective. Trends Mol. Med. 2017, 23, 615–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsokos, G.C.; Lo, M.S.; Reis, P.C.; Sullivan, K.E. New Insights into the Immunopathogenesis of Systemic Lupus Erythematosus. Nat. Rev. Rheumatol. 2016, 12, 716–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anders, H.-J.; Saxena, R.; Zhao, M.; Parodis, I.; Salmon, J.E.; Mohan, C. Lupus Nephritis. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers 2020, 6, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaul, A.; Gordon, C.; Crow, M.K.; Touma, Z.; Urowitz, M.B.; van Vollenhoven, R.; Ruiz-Irastorza, G.; Hughes, G. Systemic Lupus Erythematosus. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers 2016, 2, 16039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enríquez-Merayo, E.; Cuadrado, M.J. Steroids in Lupus: Enemies or Allies. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 3639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poetker, D.M.; Reh, D.D. A Comprehensive Review of the Adverse Effects of Systemic Corticosteroids. Otolaryngol. Clin. N. Am. 2010, 43, 753–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quatrini, L.; Ugolini, S. New Insights into the Cell- and Tissue-Specificity of Glucocorticoid Actions. Cell. Mol. Immunol. 2021, 18, 269–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lühder, F.; Reichardt, H.M. Novel Drug Delivery Systems Tailored for Improved Administration of Glucocorticoids. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2017, 18, 1836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asgeirsdóttir, S.A.; Kok, R.J.; Everts, M.; Meijer, D.K.F.; Molema, G. Delivery of Pharmacologically Active Dexamethasone into Activated Endothelial Cells by Dexamethasone-Anti-E-Selectin Immunoconjugate. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2003, 65, 1729–1739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McPherson, M.J.; Hobson, A.D.; Hayes, M.E.; Marvin, C.C.; Schmidt, D.; Waegell, W.; Goess, C.; OH, J.Z.; Hernandez, A.; Randolph, J.T.; et al. Glucocorticoid Receptor Agonist and Immunoconjugates Thereof. WO2017210471A1, 1 June 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Kern, J.C.; Dooney, D.; Zhang, R.; Liang, L.; Brandish, P.E.; Cheng, M.; Feng, G.; Beck, A.; Bresson, D.; Firdos, J.; et al. Novel Phosphate Modified Cathepsin B Linkers: Improving Aqueous Solubility and Enhancing Payload Scope of ADCs. Bioconjug. Chem. 2016, 27, 2081–2088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buttgereit, F.; Singhal, A.; Kivitz, A.; Drescher, E.; Taniguchi, Y.; Pérez, R.M.; Anderson, J.; D’Cunha, R.; Zhao, W.; DeVogel, N.; et al. Efficacy and Safety of ABBV-154 for the Treatment of Active Rheumatoid Arthritis: A Phase 2b, Randomized, Placebo-Controlled Trial. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2025, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buttgereit, F.; Aelion, J.; Rojkovich, B.; Zubrzycka-Sienkiewicz, A.; Chen, S.; Yang, Y.; Arikan, D.; D’Cunha, R.; Pang, Y.; Kupper, H.; et al. Efficacy and Safety of ABBV-3373, a Novel Anti–Tumor Necrosis Factor Glucocorticoid Receptor Modulator Antibody–Drug Conjugate, in Adults with Moderate-to-Severe Rheumatoid Arthritis Despite Methotrexate Therapy: A Randomized, Double-Blind, Active-Controlled Proof-of-Concept Phase IIa Trial. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2023, 75, 879–889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Claesson, L.; Larhammar, D.; Rask, L.; Peterson, P.A. cDNA Clone for the Human Invariant Gamma Chain of Class II Histocompatibility Antigens and Its Implications for the Protein Structure. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1983, 80, 7395–7399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gore, Y.; Starlets, D.; Maharshak, N.; Becker-Herman, S.; Kaneyuki, U.; Leng, L.; Bucala, R.; Shachar, I. Macrophage Migration Inhibitory Factor Induces B Cell Survival by Activation of a CD74-CD44 Receptor Complex. J. Biol. Chem. 2008, 283, 2784–2792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gil-Yarom, N.; Radomir, L.; Sever, L.; Kramer, M.P.; Lewinsky, H.; Bornstein, C.; Blecher-Gonen, R.; Barnett-Itzhaki, Z.; Mirkin, V.; Friedlander, G.; et al. CD74 Is a Novel Transcription Regulator. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2017, 114, 562–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schröder, B. The Multifaceted Roles of the Invariant Chain CD74—More than Just a Chaperone. Biochim. Biophys. Acta (BBA)—Mol. Cell Res. 2016, 1863, 1269–1281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kang, I.; Bucala, R. The Immunobiology of MIF: Function, Genetics and Prospects for Precision Medicine. Nat. Rev. Rheumatol. 2019, 15, 427–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Su, H.; Na, N.; Zhang, X.; Zhao, Y. The Biological Function and Significance of CD74 in Immune Diseases. Inflamm. Res. 2017, 66, 209–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ong, G.L.; Goldenberg, D.M.; Hansen, H.J.; Mattes, M.J. Cell Surface Expression and Metabolism of Major Histocompatibility Complex Class II Invariant Chain (CD74) by Diverse Cell Lines. Immunology 1999, 98, 296–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roche, P.A.; Teletski, C.L.; Stang, E.; Bakke, O.; Long, E.O. Cell Surface HLA-DR-Invariant Chain Complexes Are Targeted to Endosomes by Rapid Internalization. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1993, 90, 8581–8585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindner, R. Invariant Chain Complexes and Clusters as Platforms for MIF Signaling. Cells 2017, 6, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navarra, S.V.; Guzmán, R.M.; Gallacher, A.E.; Hall, S.; Levy, R.A.; Jimenez, R.E.; Li, E.K.-M.; Thomas, M.; Kim, H.-Y.; León, M.G.; et al. Efficacy and Safety of Belimumab in Patients with Active Systemic Lupus Erythematosus: A Randomised, Placebo-Controlled, Phase 3 Trial. Lancet 2011, 377, 721–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, D.; Li, J.; Xu, D.; Merrill, J.T.; van Vollenhoven, R.F.; Liu, Y.; Hu, J.; Li, Y.; Li, F.; Huang, C.; et al. Telitacicept in Patients with Active Systemic Lupus Erythematosus: Results of a Phase 2b, Randomised, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Trial. Annu. Rheum. Dis. 2024, 83, 475–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, Y.; Gao, D.; Zhang, Z. Telitacicept, a Novel Humanized, Recombinant TACI-Fc Fusion Protein, for the Treatment of Systemic Lupus Erythematosus. Drugs Today 2022, 58, 23–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jayne, D.; Rovin, B.; Mysler, E.; Furie, R.; Houssiau, F.; Trasieva, T.; Knagenhjelm, J.; Schwetje, E.; Tang, W.; Tummala, R.; et al. Anifrolumab in Lupus Nephritis: Results from Second-Year Extension of a Randomised Phase II Trial. Lupus Sci. Med. 2023, 10, e000910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, X.; Chen, Z.; Yi, C.; Ling, Z.; Ye, J.; Chen, K.; Cong, Y.; Sonam, W.; Cheng, S.; Wang, R.; et al. An Anti-CD47 Antibody Binds to a Distinct Epitope in a Novel Metal Ion-Dependent Manner to Minimize Cross-Linking of Red Blood Cells. J. Biol. Chem. 2025, 301, 110420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frölich, D.; Blaβfeld, D.; Reiter, K.; Giesecke, C.; Daridon, C.; Mei, H.E.; Burmester, G.R.; Goldenberg, D.M.; Salama, A.; Dörner, T. The Anti-CD74 Humanized Monoclonal Antibody, Milatuzumab, Which Targets the Invariant Chain of MHC II Complexes, Alters B-Cell Proliferation, Migration, and Adhesion Molecule Expression. Arthritis Res. Ther. 2012, 14, R54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuenzig, M.E.; Rezaie, A.; Kaplan, G.G.; Otley, A.R.; Steinhart, A.H.; Griffiths, A.M.; Benchimol, E.I.; Seow, C.H. Budesonide for the Induction and Maintenance of Remission in Crohn’s Disease: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis for the Cochrane Collaboration. J. Can. Assoc. Gastroenterol. 2018, 1, 159–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdalla, M.I.; Herfarth, H. Budesonide for the Treatment of Ulcerative Colitis. Expert Opin. Pharmacother. 2016, 17, 1549–1559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Jong, E.M.; Ferrier, C.M.; de Zwart, A.; Wauben-Penris, P.J.; Korstanje, C.; van de Kerkhof, P.C. Effects of Topical Treatment with Budesonide on Parameters for Epidermal Proliferation, Keratinization and Inflammation in Psoriasis. J. Dermatol. Sci. 1995, 9, 185–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rawla, P.; Sunkara, T.; Thandra, K.C.; Gaduputi, V. Efficacy and Safety of Budesonide in the Treatment of Eosinophilic Esophagitis: Updated Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized and Non-Randomized Studies. Drugs R. D 2018, 18, 259–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greiff, L.; Andersson, M.; Svensson, C.; Linden, M.; Wollmer, P.; Brattsand, R.; Persson, C.G. Effects of Orally Inhaled Budesonide in Seasonal Allergic Rhinitis. Eur. Respir. J. 1998, 11, 1268–1273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whelan, C.J.; Payne, A.N.; Planquois, J.M. A Comparison of the Inhibitory Effects of Budesonide, Beclomethasone Dipropionate, Dexamethasone, Hydrocortisone and Tixocortol Pivalate on Cytokine Release from Leukocytes Recovered from Human Bronchoalveolar Lavage. Inflamm. Res. 1999, 48, 224–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szefler, S.J. Pharmacodynamics and Pharmacokinetics of Budesonide: A New Nebulized Corticosteroid. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 1999, 104, 175–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klarquist, J.; Janssen, E.M. The Bm12 Inducible Model of Systemic Lupus Erythematosus (SLE) in C57BL/6 Mice. J. Vis. Exp. 2015, 105, 53319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Chen, Y.; Hou, B.; Liu, K.; Qin, H.; Fang, L.; Du, G. Coptisine Alleviates Pristane-Induced Lupus-Like Disease and Associated Kidney and Cardiovascular Complications in Mice. Front. Pharmacol. 2020, 11, 929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Du, Q.; Yao, S.; Huang, Y.; Zhang, J.; Sonam, W.; Lu, X.; Yang, J.; Cheng, S.; Wang, R.; Xu, J.; et al. CD74-Targeting Antibody–Drug Conjugate Enhances Immunosuppression of Glucocorticoid in Systemic Lupus Erythematosus. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 11761. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311761

Du Q, Yao S, Huang Y, Zhang J, Sonam W, Lu X, Yang J, Cheng S, Wang R, Xu J, et al. CD74-Targeting Antibody–Drug Conjugate Enhances Immunosuppression of Glucocorticoid in Systemic Lupus Erythematosus. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2025; 26(23):11761. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311761

Chicago/Turabian StyleDu, Qizhen, Shengtao Yao, Yuying Huang, Jia Zhang, Wangmo Sonam, Xiao Lu, Jichao Yang, Shipeng Cheng, Ran Wang, Jiefang Xu, and et al. 2025. "CD74-Targeting Antibody–Drug Conjugate Enhances Immunosuppression of Glucocorticoid in Systemic Lupus Erythematosus" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 26, no. 23: 11761. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311761

APA StyleDu, Q., Yao, S., Huang, Y., Zhang, J., Sonam, W., Lu, X., Yang, J., Cheng, S., Wang, R., Xu, J., Ma, L., Liu, Y., Wu, G., Zhang, J., Wang, X., Lu, W., Ling, Z., Yi, C., & Sun, B. (2025). CD74-Targeting Antibody–Drug Conjugate Enhances Immunosuppression of Glucocorticoid in Systemic Lupus Erythematosus. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 26(23), 11761. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311761