Biological Performance and Molecular Mechanisms of Mesyl MicroRNA-Targeted Oligonucleotides in Colorectal Cancer Cells

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Biological Performance of µ-ASO in Caco-2 Cells

2.2. Proteomic Profiling of Caco-2 Cells Following Treatment with µ-ASOs Targeted to miR-21, miR-17, and miR-155

2.2.1. Major Common Biological Processes and Signaling Pathways Regulated by µ-ASOs, Targeting miR-21, miR-17, and miR-155

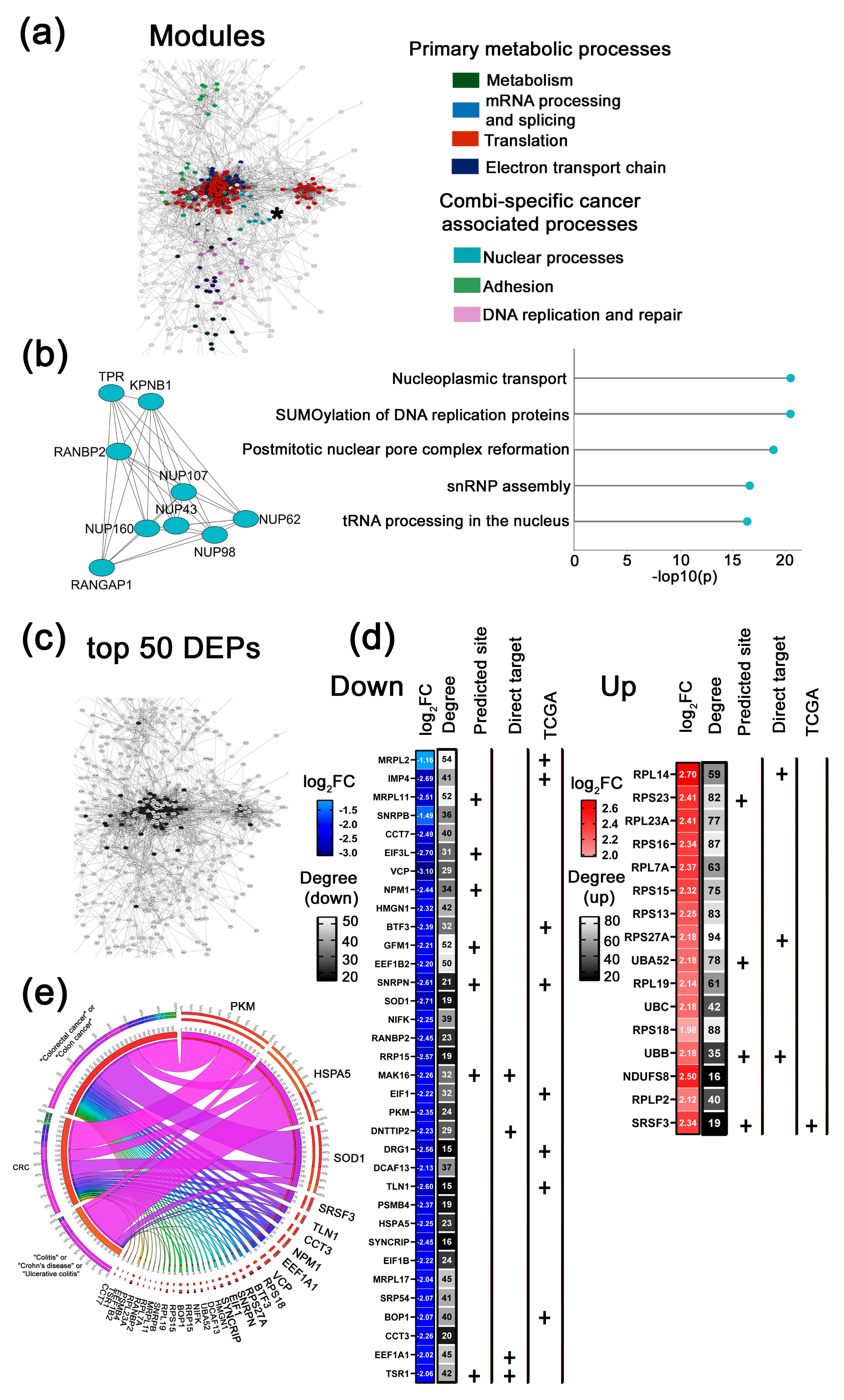

2.2.2. Key Functional Protein Modules and Top 50 Altered DEPs in Response to µ-ASOs Targeting miR-21, miR-17, and miR-155

Key Functional Modules Altered by µ-ASOs Treatment

- 1.

- µ-21-specific cancer-associated modules

- 2.

- µ-17-specific cancer-associated modules

- 3.

- µ-155-specific cancer-associated modules

- 4.

- Combi-specific cancer-associated modules

Key Altered DEPs upon µ-ASOs Targeting to miR-21, miR-17 and miR-155, Treatment

- 1.

- top 50 DEPs altered in response to µ-21

- 2.

- top 50 DEPs altered in response to µ-17

- 3.

- top 50 DEPs altered in response to µ-155

- 4.

- top 50 DEPs altered in response to Combi

3. Discussion

3.1. Therapeutically Beneficial Effects of µ-ASO Targeted to miR-21, miR-17, and miR-155 in Caco-2 Cells

3.2. Compensatory Response of Caco-2 Cells on Treatment with µ-ASO Targeted to miR-21, miR-17 and miR-155

3.3. Correlation with Previously Reported Literature and Clinical Observations

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Oligonucleotide Synthesis

4.2. Transfection of Tumor Cells with µ-ASOs

4.3. Flow Cytometry

4.4. Cell Viability Test

4.5. Scratch Assay

4.6. Stem-Loop PCR

4.7. Proteomic Analysis

4.8. Cell Lysis and Protein Quantification

4.9. Sample Preparation for LC–MS/MS Using S-Trap

4.10. LC–MS/MS Analysis

4.11. Data Processing and Analysis

4.12. Functional Analysis and PPI Network Reconstruction

4.13. Evaluation of Top 50 DEPs and Text Mining Analysis

4.14. Survival Analysis and Tumor Grade Correlation of DEPs

4.15. Statistics

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| µ-ASOs | Methanesulfonyl phosphoramidate-modified antisense oligonucleotides |

| ACAA1 | Acetyl-CoA Acyltransferase 1 |

| ACADS | Acyl-CoA Dehydrogenase, Short Chain |

| ACTG | Gamma-actin |

| ALDH2 | Aldehyde Dehydrogenase 2 |

| ALDH7A1 | Aldehyde Dehydrogenase 7 Family Member A1 |

| ANLN | Anillin, Actin Binding Protein |

| AP2A1 | Adaptor Related Protein Complex 2 Subunit Alpha 1 |

| ARPC2 | Actin-Related Protein 2/3 Complex Subunit 2 |

| ATIC | 5-Aminoimidazole-4-Carboxamide Ribonucleotide Formyltransferase/IMP Cyclohydrolase |

| BCA | Bicinchoninic acid |

| BOP1 | Block of Proliferation 1 Ribosome Biogenesis Factor |

| BTF3 | Basic Transcription Factor 3 |

| CCT2 | Chaperonin Containing TCP1 Subunit 2 |

| CCT3 | Chaperonin Containing TCP1 Subunit 3 |

| CCT5 | Chaperonin Containing TCP1 Subunit 5 |

| CCT7 | Chaperonin Containing TCP1 Subunit 7 |

| CAF | Cancer-Associated Fibroblasts |

| CADM2 | Cell Adhesion Molecule 2 |

| CCNH | Cyclin H |

| CDC37 | Cell Division Cycle 37 |

| CDC42 | Cell Division Cycle 42 |

| CD44 | CD44 Molecule (Cell Surface Glycoprotein) |

| CDH1 | Cadherin 1 (E-Cadherin) |

| CDK1 | Cyclin-dependent kinase 1 |

| CENPF | Centromere protein F |

| CHX | Cycloheximide |

| CLTA | Clathrin Light Chain A |

| COAD | Colorectal adenocarcinoma |

| COX5A | Cytochrome c Oxidase Subunit 5A |

| CRC | Colorectal Cancer |

| DAP3 | Death-Associated Protein 3 |

| DCAF13 | DDB1 And CUL4 Associated Factor 13 |

| DDX39B | DEAD-Box Helicase 39B |

| DEPs | Differentially Expressed Proteins |

| DENR | Density Regulated Re-initiation and Release Factor |

| DLD | Dihydrolipoamide Dehydrogenase |

| DKC1 | Dyskerin Pseudouridine Synthase 1 |

| DNA | Deoxyribonucleic acid |

| DNM2 | Dynamin-2 |

| DNAJB11 | DnaJ Heat Shock Protein Family (Hsp40) Member B11 |

| DNAJC9 | DnaJ Heat Shock Protein Family (Hsp40) Member C9 |

| DRG1 | Developmentally Regulated GTP Binding Protein 1 |

| DYNC1H1 | Dynein Cytoplasmic 1 Heavy Chain 1 |

| ECHS1 | Enoyl Coenzyme A Hydratase, Short Chain, 1 |

| EEF1A1 | Eukaryotic Translation Elongation Factor 1 Alpha 1 |

| EEF1B2 | Eukaryotic Translation Elongation Factor 1 Beta 2 |

| EEF2 | Eukaryotic Translation Elongation Factor 2 |

| EEFSEC | Eukaryotic Elongation Factor, Selenocysteine-specific |

| ECM | Extracellular Matrix |

| EIF1 | Eukaryotic Translation Initiation Factor 1 |

| EIF1B | Eukaryotic Translation Initiation Factor 1B |

| EIF2S3 | Eukaryotic Translation Initiation Factor 2 Subunit 3 |

| EIF3A | Eukaryotic Translation Initiation Factor 3 Subunit A |

| EIF3C | Eukaryotic Translation Initiation Factor 3 Subunit C |

| EIF3CL | Eukaryotic Translation Initiation Factor 3 Subunit C-Like |

| EIF3F | Eukaryotic Translation Initiation Factor 3 Subunit F |

| EIF3H | Eukaryotic Translation Initiation Factor 3 Subunit H |

| EIF3L | Eukaryotic Translation Initiation Factor 3 Subunit L |

| EIF3M | Eukaryotic Translation Initiation Factor 3 Subunit M |

| EIF4A2 | Eukaryotic Translation Initiation Factor 4A2 |

| EIF4A3 | Eukaryotic Translation Initiation Factor 4A3 |

| EPN1 | Epsin 1 |

| ER | Endoplasmic Reticulum |

| ERCC2 | Excision Repair Cross-Complementing 2 |

| EXOSC10 | Exosome Component 10 |

| FC | Fold change |

| FLNA | Filamin A |

| FN1 | Fibronectin 1 |

| FOXO3a | Forkhead Box O3a |

| GANAB | Glucosidase II Alpha Subunit |

| GAPDH | Glyceraldehyde-3-Phosphate Dehydrogenase |

| GFM1 | G Elongation Factor, Mitochondrial 1 |

| GLUD1 | Glutamate Dehydrogenase 1 |

| GLUD2 | Glutamate Dehydrogenase 2 |

| GSPT1 | G1 to S Phase Transition 1/eRF3a |

| GRWD1 | Glutamate Rich WD Repeat Containing 1 |

| GTF2E2 | General Transcription Factor IIE Subunit 2 |

| HMGN1 | High Mobility Group Nucleosomal Binding Domain 1 |

| HPLC | High performance liquid chromatography |

| HSBP2 | Heat Shock Protein Family B (Small) Member 2 |

| HSPD1 | Heat Shock Protein Family D (Hsp60) Member 1 |

| HSPA5 | Heat Shock Protein Family A (Hsp70) Member 5 (BiP/GRP78) |

| HSPE1 | Heat Shock Protein Family E (Hsp10) Member 1 |

| HSP90AA1 | Heat Shock Protein 90 Alpha Family Class A Member 1 |

| HYOU1 | Hypoxia Upregulated 1 |

| IDH1 | Isocitrate Dehydrogenase 1 (NADP+) |

| IL | Interleukin |

| IMP4 | IMP U3 Small Nucleolar Ribonucleoprotein 4 |

| IPO5 | Importin 5 |

| IPO7 | Importin 7 |

| IPO9 | Importin 9 |

| ITGA1 | Integrin Alpha 1 |

| ITGA2 | Integrin Alpha 2 |

| ITGA6 | Integrin Alpha 6 |

| ITGAV | Integrin Alpha V |

| ITGB1 | Integrin Subunit Beta 1 |

| JAK2 | Janus Kinase 2 |

| JNK | c-Jun N-terminal Kinase |

| KPNA2 | Karyopherin Subunit Alpha 2 |

| KPNB1 | Karyopherin Subunit Beta 1 |

| LAMA5 | Laminin Subunit Alpha 5 |

| LAMB1 | Laminin Subunit Beta 1 |

| LAMC1 | Laminin Subunit Gamma 1 |

| MAD2L1 | Mitotic Arrest Deficient 2 Like 1 |

| MAGOH | Mago Homolog |

| MAGOHB | Mago Homolog B |

| MAK16 | MAK16 Ribosome Biogenesis Factor |

| MAPK | Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinase |

| MED4 | Mediator Complex Subunit 4 |

| miRNA, miR | Micro ribonucleic acid |

| MRPL2 | Mitochondrial Ribosomal Protein L2 |

| MRPL11 | Mitochondrial Ribosomal Protein L11 |

| MRPL17 | Mitochondrial Ribosomal Protein L17 |

| MRPL27 | Mitochondrial Ribosomal Protein L27 |

| MRPS9 | Mitochondrial Ribosomal Protein S9 |

| MRPS14 | Mitochondrial Ribosomal Protein S14 |

| MRPS15 | Mitochondrial Ribosomal Protein S15 |

| MRPS24 | Mitochondrial Ribosomal Protein S24 |

| MRRF | Mitochondrial Ribosome Recycling Factor |

| MSH2 | MutS Homolog 2 |

| MSH6 | MutS Homolog 6 |

| NDUFS3 | NADH: Ubiquinone Oxidoreductase Core Subunit S3 |

| NDUFS8 | NADH: Ubiquinone Oxidoreductase Core Subunit S8 |

| NEDD8 | Neural precursor cell Expressed Developmentally Down-regulated 8 |

| NIFK | Nucleolar Protein Interacting with the FHA Domain and Ki67 |

| NOL11 | Nucleolar Protein 11 |

| NPM1 | Nucleophosmin 1 |

| NPC | Nuclear Pore Complex |

| NUDC | Nuclear Distribution C, Dynein Complex Regulator |

| NUP43 | Nucleoporin 43 |

| NUP85 | Nucleoporin 85 |

| NUP98 | Nucleoporin 98 |

| NUP107 | Nucleoporin 107 |

| NUP160 | Nucleoporin 160 |

| NXF1 | Nuclear RNA Export Factor 1 |

| OGDH | Oxoglutarate Dehydrogenase |

| PARP1 | Poly (ADP-Ribose) Polymerase 1 |

| PBS | Phosphate buffered saline |

| PCA | Principal component analysis |

| PCR | Polymerase chain reaction |

| PFDN4 | Prefoldin Subunit 4 |

| PFDN6 | Prefoldin Subunit 6 |

| PDCD4 | Programmed Cell Death Protein 4 |

| PDIA4 | Protein Disulfide Isomerase Family A Member 4 |

| PDIA6 | Protein Disulfide Isomerase Family A Member 6 |

| PES1 | Pescadillo Ribosomal Biogenesis Factor 1 |

| PFKL | Phosphofructokinase, Liver Type |

| PHF5A | PHD Finger Protein 5A |

| PLK1 | Polo Like Kinase 1 |

| POLD2 | DNA Polymerase Delta 2, Accessory Subunit |

| POLD3 | DNA Polymerase Delta 3, Accessory Subunit |

| POLE3 | DNA Polymerase Epsilon 3, Accessory Subunit |

| POLR2A | RNA Polymerase II Subunit A |

| PPI | Protein-protein interaction |

| PPP2CA | Protein Phosphatase 2 Catalytic Subunit Alpha |

| PPP5C | Protein Phosphatase 5 Catalytic Subunit |

| PRIM1 | DNA Primase, Catalytic Subunit 1 |

| PRPF4 | Pre-MRNA Splicing Tri-SnRNP Complex Factor 4 |

| PTEN | Phosphatase And Tensin Homolog |

| PSMB3 | Proteasome Subunit Beta 3 |

| PSMB4 | Proteasome Subunit Beta 4 |

| PSMG1 | Proteasome Assembly Chaperone 1 |

| PSMD1 | Proteasome 26S Subunit, Non-ATPase 1 |

| PSMD2 | Proteasome 26S Subunit, Non-ATPase 2 |

| PSMD3 | Proteasome 26S Subunit, Non-ATPase 3 |

| PSMD5 | Proteasome 26S Subunit, Non-ATPase 5 |

| PSMD14 | Proteasome 26S Subunit, Non-ATPase 14 |

| PSMC | Proteasome 26S Subunit, ATPase |

| PSMA | Proteasome 20S Subunit Alpha |

| RACGAP1 | Rac GTPase Activating Protein 1 |

| RAN | Ras-Related Nuclear Protein |

| RANBP2 | RAN Binding Protein 2 |

| RANGAP1 | Ran GTPase Activating Protein 1 |

| RAS | Rat sarcoma virus |

| RASA1 | RAS p21 Protein Activator 1 |

| RBM39 | RNA Binding Motif Protein 39 |

| RBM42 | RNA Binding Motif Protein 42 |

| RFU | Relative fluorescence unit |

| RHOA | Ras Homolog Family Member A |

| RNA | Ribonucleic acid |

| RNPS1 | RNA Binding Protein With Serine Rich Domain 1 |

| RPA | Replication protein A |

| RPL14 | Ribosomal Protein L14 |

| RPL17 | Ribosomal Protein L17 |

| RPL19 | Ribosomal Protein L19 |

| RPL23A | Ribosomal Protein L23a |

| RPL27 | Ribosomal Protein L27 |

| RPL31 | Ribosomal Protein L31 |

| RPL32 | Ribosomal Protein L32 |

| RPL37a | Ribosomal Protein L37a |

| RPL6 | Ribosomal Protein L6 |

| RPL7A | Ribosomal Protein L7a |

| RPL8 | Ribosomal Protein L8 |

| RPLP0 | Ribosomal Protein Lateral Stalk Subunit P0 |

| RPLP2 | Ribosomal Protein Lateral Stalk Subunit P2 |

| RPS2 | Ribosomal Protein S2 |

| RPS4X | Ribosomal Protein S4, X-Linked |

| RPS7 | Ribosomal Protein S7 |

| RPS9 | Ribosomal Protein S9 |

| RPS13 | Ribosomal Protein S13 |

| RPS14 | Ribosomal Protein S14 |

| RPS15 | Ribosomal Protein S15 |

| RPS15A | Ribosomal Protein S15A |

| RPS16 | Ribosomal Protein S16 |

| RPS18 | Ribosomal Protein S18 |

| RPS20 | Ribosomal Protein S20 |

| RPS23 | Ribosomal Protein S23 |

| RPS27A | Ribosomal Protein S27a |

| RPS29 | Ribosomal Protein S29 |

| RPSA | Ribosomal Protein SA |

| RRP9 | Ribosomal RNA Processing 9 |

| RRP15 | Ribosomal RNA Processing 15 |

| RSL24D1 | Ribosomal L24 Domain Containing 1 |

| RT | Reverse Transcription |

| RUNX3 | RUNX Family Transcription Factor 3 |

| SDS | Sodium Lauryl Sulfate |

| SEC13 | SEC13 Homolog, Nuclear Pore and COPII Component |

| SEC23A | SEC23 Homolog A, COPII Coat Complex Component |

| SF3B3 | Splicing Factor 3b Subunit 3 |

| SKP1 | S-Phase Kinase Associated Protein 1 |

| SKP2 | S-Phase Kinase Associated Protein 2 |

| SNRPB | Small Nuclear Ribonucleoprotein Polypeptide B |

| SNRPD2 | Small Nuclear Ribonucleoprotein D2 |

| SNRPC | Small Nuclear Ribonucleoprotein Polypeptide C |

| SNRPN | Small Nuclear Ribonucleoprotein Polypeptide N |

| SOD1 | Superoxide Dismutase 1 |

| SOD2 | Superoxide Dismutase 2 |

| SRC | SRC Proto-Oncogene, Non-Receptor Tyrosine Kinase |

| SRP54 | Signal Recognition Particle 54 |

| SRSF3 | Serine And Arginine Rich Splicing Factor 3 |

| STAT3 | Signal Transducer And Activator Of Transcription 3 |

| SYNCRIP | SYNaptotagmin Binding Cytoplasmic RNA Binding Protein |

| TCA | Tricarboxylic acid cycle |

| TCEP | Tris(2-chloroethyl) Phosphate |

| TCERG1 | Transcription Elongation Regulator 1 |

| TCGA | The Cancer Genome Atlas |

| TEAB | Tetraethylammonium bromide |

| TEX10 | Testis Expressed 10 |

| TGF-β | Transforming Growth Factor Beta |

| TLN1 | Talin 1 |

| TNM | Tumor Node Metastasis |

| TNPO1 | Transportin 1 |

| TRMT112 | tRNA Methyltransferase 112 |

| TPR | Translocated Promoter Region |

| TPX2 | Targeting Protein for Xklp2 |

| TSR1 | TSR1 Ribosome Maturation Factor |

| TUBA1B | Tubulin Alpha 1B |

| TUBA1C | Tubulin Alpha 1C |

| TUBB4B | Tubulin Beta 4B |

| TUBB | Tubulin Beta |

| TUFM | Tu Translation Elongation Factor, Mitochondrial |

| UBA52 | Ubiquitin A-52 Residue Ribosomal Protein Fusion Product 1 |

| UBC | Ubiquitin C |

| UBB | Ubiquitin B |

| UQCRC1 | Ubiquinol-Cytochrome c Reductase Core Protein I |

| UQCRC2 | Ubiquinol-Cytochrome c Reductase Core Protein II |

| VCP | Valosin Containing Protein |

| VDAC1 | Voltage Dependent Anion Channel 1 |

| VEGF | Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor |

| WDR61 | WD Repeat Domain 61 |

| WNT | Wnt Signaling Molecules |

References

- Matsuda, T.; Fujimoto, A.; Igarashi, Y. Colorectal Cancer: Epidemiology, Risk Factors, and Public Health Strategies. Digestion 2025, 106, 91–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di Martino, M.; Tagliaferri, P.; Tassone, P. MicroRNA in cancer therapy: Breakthroughs and challenges in early clinical applications. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 2025, 44, 126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Niazi, S.K.; Magoola, M. MicroRNA Nobel Prize: Timely Recognition and High Anticipation of Future Products—A Prospective Analysis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 12883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Budakoti, M.; Panwar, A.S.; Molpa, D.; Singh, R.K.; Büsselberg, D.; Mishra, A.P.; Coutinho, H.D.M.; Nigam, M. Micro-RNA: The Darkhorse of Cancer. Cell. Signal. 2021, 83, 109995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, F.; Jiang, W.; Zhou, L.; Chen, Z. Circulating Exosomal MiR-17-5p and MiR-92a-3p Predict Pathologic Stage and Grade of Colorectal Cancer. Transl. Oncol. 2018, 11, 221–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Yang, W.; Luo, Y.; Hu, S.; Zhu, L. Correlation between MiR-21 and MiR-145 and the Incidence and Prognosis of Colorectal Cancer. J. BUON 2018, 23, 29–35. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Bai, Y.; Xiong, Y.; Zhang, Y.Y.; Cheng, L.; Liu, H.; Xu, K.; Wu, Y.Y.; Field, J.; Wang, X.D.; Zhou, L.M. Tangeretin Synergizes with 5-Fluorouracil to Induce Autophagy through MicroRNA-21 in Colorectal Cancer Cells. Am. J. Chin. Med. 2022, 50, 1681–1701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabry, D.; El-Deek, S.E.M.; Maher, M.; El-Baz, M.A.H.; El-Bader, H.M.; Amer, E.; Hassan, E.A.; Fathy, W.; El-Deek, H.E.M. Role of MiRNA-210, MiRNA-21 and MiRNA-126 as Diagnostic Biomarkers in Colorectal Carcinoma: Impact of HIF-1α-VEGF Signaling Pathway. Mol. Cell. Biochem. 2019, 454, 177–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Z.; Hou, Z.; Li, L.; Liu, W.; Yu, Z.; Chen, S. Exosomal CircEPB41L2 Serves as a Sponge for MiR-21-5p and MiR-942-5p to Suppress Colorectal Cancer Progression by Regulating the PTEN/AKT Signalling Pathway. Eur. J. Clin. Investig. 2021, 51, e13581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, L.; Liang, Y.; Wu, K.; Wang, C.; Zhang, T.; Peng, R.; Zou, F. Repressing PDCD4 Activates JNK/ABCG2 Pathway to Induce Chemoresistance to Fluorouracil in Colorectal Cancer Cells. Ann. Transl. Med. 2021, 9, 114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gong, B.; Liu, W.W.; Nie, W.J.; Li, D.F.; Xie, Z.J.; Liu, C.; Liu, Y.H.; Mei, P.; Li, Z.J. MiR-21/RASA1 Axis Affects Malignancy of Colon Cancer Cells via RAS Pathways. World J. Gastroenterol. 2015, 21, 1488–1497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Despotovic, J.; Dragicevic, S.; Nikolic, A. Effects of Chemotherapy for Metastatic Colorectal Cancer on the TGF-β Signaling and Related MiRNAs Hsa-MiR-17-5p, Hsa-MiR-21-5p and Hsa-MiR-93-5p. Cell Biochem. Biophys. 2021, 79, 757–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Wang, S.; Lai, Q.; Fang, Y.; Wu, C.; Liu, Y.; Li, Q.; Wang, X.; Gu, C.; Chen, J.; et al. Cancer-Associated Fibroblasts-Derived Exosomal MiR-17-5p Promotes Colorectal Cancer Aggressive Phenotype by Initiating a RUNX3/MYC/TGF-Β1 Positive Feedback Loop. Cancer Lett. 2020, 491, 22–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-nakhle, H.H. Unraveling the Multifaceted Role of the MiR-17-92 Cluster in Colorectal Cancer: From Mechanisms to Biomarker Potential. Curr. Issues Mol. Biol. 2024, 46, 1832–1850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, W.; Wang, J.; Li, C.; Xuan, M.; Han, S.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, P.; Zhao, Z. MiR-17-5p Promotes the Invasion and Migration of Colorectal Cancer by Regulating HSPB2. J. Cancer 2022, 13, 918–931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Zhao, J.; Wang, Y.; Gao, J.; Yang, H.; Li, H. MiR-17-5p Targets and Downregulates CADM2, Activating the Malignant Phenotypes of Colon Cancer Cells. Mol. Biotechnol. 2022, 64, 1388–1400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Wang, X.; Song, Y.; Si, M.; Sun, Y.; Liu, X.; Cui, S.; Qu, X.; Yu, X. Exosomal MiR-146a-5p and MiR-155-5p Promote CXCL12/CXCR7-Induced Metastasis of Colorectal Cancer by Crosstalk with Cancer-Associated Fibroblasts. Cell Death Dis. 2022, 13, 380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saberinia, A.; Alinezhad, A.; Jafari, F.; Soltany, S.; Akhavan Sigari, R. Oncogenic MiRNAs and Target Therapies in Colorectal Cancer. Clin. Chim. Acta 2020, 508, 77–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, N.; Jiang, F.; Han, X.Y.; Li, M.; Chen, W.J.; Liu, Q.C.; Liao, C.X.; Lv, Y.F. MiRNA-155 Promotes the Invasion of Colorectal Cancer SW-480 Cells through Regulating the Wnt/β-Catenin. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci. 2018, 22, 101–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Haidari, A.A.; Syk, I.; Thorlacius, H. MiR-155-5p Positively Regulates CCL17-Induced Colon Cancer Cell Migration by Targeting RhoA. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 14887–14896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, D.; Geng, W.; Han, L.; Song, R.; Qu, Q.S.; Chen, X.Y.; Luo, X. Pro-Carcinogenic Actions of MiR-155/FOXO3a in Colorectal Cancer Development. Cell. Mol. Biol. 2023, 69, 160–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miroshnichenko, S.K.; Patutina, O.A.; Burakova, E.A.; Chelobanov, B.P.; Fokina, A.A.; Vlassov, V.V.; Altman, S.; Zenkova, M.A.; Stetsenko, D.A. Mesyl Phosphoramidate Antisense Oligonucleotides as an Alternative to Phosphorothioates with Improved Biochemical and Biological Properties. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2019, 116, 1229–1234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patutina, O.; Gaponova, S.K.; Sen’kova, A.V.; Savin, I.A.; Gladkikh, D.V.; Burakova, E.A.; Fokina, A.A.; Maslov, M.A.; Shmendel’, E.V.; Wood, M.J.A.; et al. Mesyl Phosphoramidate Backbone Modified Antisense Oligonucleotides Targeting MiR-21 with Enhanced in Vivo Therapeutic Potency. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2020, 117, 32370–32379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gaponova, S.; Patutina, O.; Sen’kova, A.; Burakova, E.; Savin, I.; Markov, A.; Shmendel, E.; Maslov, M.; Stetsenko, D.; Vlassov, V.; et al. Single Shot vs. Cocktail: A Comparison of Mono- and Combinative Application of MiRNA-Targeted Mesyl Oligonucleotides for Efficient Antitumor Therapy. Cancers 2022, 14, 4396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Lee, J.; Liem, D.; Ping, P. HSPA5 Gene Encoding Hsp70 Chaperone BiP in the Endoplasmic Reticulum. Gene 2017, 618, 14–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, S.; Yang, E.J.; Zong, G.; Mou, P.K.; Ren, G.; Pu, Y.; Chen, L.; Kwon, H.J.; Zhou, J.; Hu, Z.; et al. ER Translocon Inhibitor Ipomoeassin F Inhibits Triple-Negative Breast Cancer Growth via Blocking ER Molecular Chaperones. Int. J. Biol. Sci. 2023, 19, 4020–4035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Hu, J.; Sun, Q.; Guo, S.; Zhang, G.; Lu, A.; Liu, S.; Yang, X.; Wang, L. Identification and Validation of Endoplasmic Reticulum Autophagy-Related Potential Biomarkers in Periodontitis. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 4020–4035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, A.; Narayan, G. Oncogenic potential of nucleoporins in non-hematological cancers: Recent update beyond chromosome translocation and gene fusion. J. Cancer Res. Clin. Oncol. 2019, 145, 2901–2910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aksenova, V.; Smith, A.; Lee, H.; Bhat, P.; Esnault, C.; Chen, S.; Iben, J.; Kaufhold, R.; Yau, K.C.; Echeverria, C.; et al. Nucleoporin TPR is an integral component of the TREX-2 mRNA export pathway. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 4577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meng, Y.; Guo, D.; Lin, L.; Zhao, H.; Xu, W.; Luo, S.; Jiang, X.; Li, S.; He, X.; Zhu, R.; et al. Glycolytic Enzyme PFKL Governs Lipolysis by Promoting Lipid Droplet–Mitochondria Tethering to Enhance β-Oxidation and Tumor Cell Proliferation. Nat. Metab. 2024, 6, 1092–1107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, C.; Yu, X.; Liang, Y.; Zhu, Y.; He, Y.; Liao, L.; Wang, D.; Yang, Y.; Yin, X.; Li, A.; et al. Targeting PFKL with Penfluridol Inhibits Glycolysis and Suppresses Esophageal Cancer Tumorigenesis in an AMPK/FOXO3a/BIM-Dependent Manner. Acta Pharm. Sin. B 2022, 12, 1271–1287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, N.; Wang, X.; Sun, J.; Liu, Y.; Han, A.; Lin, Z.; Yang, Y. MiR-21-5p/Tiam1-Mediated Glycolysis Reprogramming Drives Breast Cancer Progression via Enhancing PFKL Stabilization. Carcinogenesis 2022, 43, 705–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, G.; Yun, F.; Jiang, L.; Yi, Z.; Yi, X.; Yang, L.; Zhang, X.; Li, X.; Yang, Z.; Zhang, Q.; et al. NDUFS3 Promotes Proliferation via Glucose Metabolism Reprogramming Inducing AMPK Phosphorylating PRPS1 to Increase the Purine Nucleotide Synthesis in Melanoma. Cell Death Differ. 2025, 32, 2193–2209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, W.; Wang, Y.; Huang, Y.; Yu, J.; Wang, T.; Li, C.; Yang, L.; Zhang, P.; Shi, L.; Yin, Y.; et al. 4-Octyl Itaconate Inhibits Aerobic Glycolysis by Targeting GAPDH to Promote Cuproptosis in Colorectal Cancer. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2023, 159, 114301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhang, H.; Li, M.; Li, Y.; Wang, Z.R.; Cheng, W.; Liu, Y.; Fang, Z.; Zheng, A.; Wang, J.; et al. Lnc-TPT1-AS1/CBP/ATIC Axis Mediated Purine Metabolism Activation Promotes Breast Cancer Progression. Cancer Sci. 2025, 116, 1565–1578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miyo, M.; Konno, M.; Nishida, N.; Sueda, T.; Noguchi, K.; Matsui, H.; Colvin, H.; Kawamoto, K.; Koseki, J.; Haraguchi, N.; et al. Metabolic Adaptation to Nutritional Stress in Human Colorectal Cancer. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 38415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, W.T.; Jin, X.; Xu, X.E.; Yang, Y.S.; Ma, D.; Shao, Z.M.; Jiang, Y.Z. Inhibition of ACAA1 Restrains Proliferation and Potentiates the Response to CDK4/6 Inhibitors in Triple-Negative Breast Cancer. Cancer Res. 2023, 83, 1711–1724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, W.-L.; Jiang, H.-J.; Shen, Z.-L.; Tang, Y.-L.; Jiang, J.; Liang, X.-H. Identification of ACAA1 and HADHB as Potential Prognostic Biomarkers Based on a Novel Fatty Acid Oxidation-Related Gene Model in Head and Neck Squamous Cell Carcinoma: A Retrospective Study. Arch. Oral. Biol. 2024, 163, 105982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, T.; Li, X.; Zhao, W.; Wang, X.; Jin, L.; Feng, Z.; Li, H.; Zhang, M.; Tian, Y.; Hu, G.; et al. SF3B3-Regulated MTOR Alternative Splicing Promotes Colorectal Cancer Progression and Metastasis. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 2024, 43, 126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tan, L.; He, Y.; Wu, L.; Liu, S.; Peng, P.; Huang, J. NIFK as a Potential Prognostic Biomarker in Colorectal Cancer Correlating with Immune Infiltrates. Medicine 2023, 102, e35452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, T.; Wang, B.; Sun, L. The Nucleolar Protein NIFK Accelerates the Progression of Colorectal Cancer via Activating MYC Pathway. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 2024, 88, 26–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Wang, F.; Lin, X.; Li, Q.; Lu, Y.; Zhang, J.; Shen, X.; Tan, J.; Qin, Z.; Chen, J.; et al. Nuclear VCP Drives Colorectal Cancer Progression by Promoting Fatty Acid Oxidation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2023, 120, e2221653120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shang, Y.; Zhang, F.; Li, D.; Li, C.; Li, H.; Jiang, Y.; Zhang, D. Overexpression of UQCRC2 Is Correlated with Tumor Progression and Poor Prognosis in Colorectal Cancer. Pathol. Res. Pract. 2018, 214, 1613–1620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, X.; Wu, N.; Yang, W.; Sun, J.; Yan, K.; Wu, J. OGDH Promotes the Progression of Gastric Cancer by Regulating Mitochondrial Bioenergetics and Wnt/β-Catenin Signal Pathway. OncoTargets Ther. 2019, 12, 7489–7500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, Q.; Yu, F.; Jin, H.; Zhang, P.; Huang, X.; Peng, J.; Xie, X.; Li, X.; Ma, N.; Wei, Y.; et al. EIF3f Mediates SGOC Pathway Reprogramming by Enhancing Deubiquitinating Activity in Colorectal Cancer. Adv. Sci. 2023, 10, e2300759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mossmann, D.; Müller, C.; Park, S.; Ryback, B.; Colombi, M.; Ritter, N.; Weißenberger, D.; Dazert, E.; Coto-Llerena, M.; Nuciforo, S.; et al. Arginine Reprograms Metabolism in Liver Cancer via RBM39. Cell 2023, 186, 5068–5083.e23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, L.; Guo, W.; Zhao, S.; Tang, J.; Liu, J. Knockdown of Mad2 Induces Osteosarcoma Cell Apoptosis-Involved Rad21 Cleavage. J. Orthop. Sci. 2011, 16, 814–820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meng, Z.Y.; Fan, Y.C.; Zhang, C.S.; Zhang, L.L.; Wu, T.; Nong, M.Y.; Wang, T.; Chen, C.; Jiang, L.H. EXOSC10 Is a Novel Hepatocellular Carcinoma Prognostic Biomarker: A Comprehensive Bioinformatics Analysis and Experiment Verification. PeerJ 2023, 11, e15860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Yi, Y.; Bai, B.; Li, L.; You, T.; Sun, W.; Yu, Y. The Silencing of Replication Protein A1 Induced Cell Apoptosis via Regulating Caspase 3. Life Sci. 2018, 201, 141–149, Erratum in Life Sci. 2025, 383, 124035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shyrokova, E.Y.; Prassolov, V.S.; Spirin, P.V. The Role of the MCTS1 and DENR Proteins in Regulating the Mechanisms Associated with Malignant Cell Transformation. Acta Naturae 2021, 13, 98–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dharmapal, D.; Jyothy, A.; Mohan, A.; Balagopal, P.G.; George, N.A.; Sebastian, P.; Maliekal, T.T.; Sengupta, S. β-Tubulin Isotype, TUBB4B, Regulates The Maintenance of Cancer Stem Cells. Front. Oncol. 2021, 11, 788024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, E.; Yang, X.; Yang, J.; Qu, Q.; Li, X. LAMB1 Promotes Proliferation and Metastasis in Nasopharyngeal Carcinoma and Shapes the Immune-Suppressive Tumor Microenvironment. Braz. J. Otorhinolaryngol. 2025, 91, 101551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, H.; Kim, W.J.; Kang, H.G.; Jang, J.H.; Choi, I.J.; Chun, K.H.; Kim, S.J. Upregulation of Lamb1 via ERK/c-Jun Axis Promotes Gastric Cancer Growth and Motility. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, Y.; Zhang, C.; Liu, L.; Yu, Y.; Shi, L.; Qin, Y. WDR61 Ablation Triggers R-Loop Accumulation and Suppresses Breast Cancer Progression. FEBS J. 2024, 291, 3417–3431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trochet, D.; Bitoun, M. A Review of Dynamin 2 Involvement in Cancers Highlights a Promising Therapeutic Target. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 2021, 40, 238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Q.; Liu, C.; Wang, H.; Li, S.; Yan, H.; Liu, Z.; Chen, K.; Xu, Y.; Yang, R.; Zhou, J.; et al. Deciphering the Impact of Aggregated Autophagy-Related Genes TUBA1B and HSP90AA1 on Colorectal Cancer Evolution: A Single-Cell Sequencing Study of the Tumor Microenvironment. Discov. Oncol. 2024, 15, 431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Q.; Yang, Q.; Xu, J.; Zhang, X.; Kim, D.; Liu, Z.; Da, Q.; Mao, X.; Zhou, Y.; Cai, Y.; et al. ATIC-Associated De Novo Purine Synthesis Is Critically Involved in Proliferative Arterial Disease. Circulation 2022, 146, 1444–1460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavudi, K.; Nuguri, S.M.; Pandey, P.; Kokkanti, R.R.; Wang, Q.E. ALDH and Cancer Stem Cells: Pathways, Challenges, and Future Directions in Targeted Therapy. Life Sci. 2024, 356, 123033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, P.; Liu, H.; Li, Y.; Gao, Q.; Chen, X.; Chang, J.; Li, Y.; Chen, S.; Dong, R.; Wu, H.; et al. Overexpression of TCERG1 as a Prognostic Marker in Hepatocellular Carcinoma: A TCGA Data-Based Analysis. Front. Genet. 2022, 13, 959832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liang, X.; Zhang, H.; Shang, W.; Wang, M.; Li, J.; Zhao, Y.; Fang, C. PPP2CA Inhibition Promotes Ferroptosis Sensitivity Through AMPK/SCD1 Pathway in Colorectal Cancer. Dig. Dis. Sci. 2024, 69, 2083–2095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Q.; Huang, R.; Lv, L.; Ying, H.; Wu, Y.; Huang, Y.Q.; Li, Y.; Ma, W.; Liu, X.; Meng, Q.; et al. FLNA, a Disulfidptosis-Related Gene, Modulates Tumor Immunity and Progression in Colorectal Cancer. Cell. Mol. Biol. Lett. 2025, 30, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Lu, T.; Chen, H.; Yu, Z.; Chen, C. The Up-Regulation of SYNCRIP Promotes the Proliferation and Tumorigenesis via DNMT3A/P16 in Colorectal Cancer. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 21570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, Y.; Koga, Y.; Su, C.; Waterbury, A.L.; Johny, C.L.; Liau, B.B. Versatile Synthetic Route to Cycloheximide and Analogues That Potently Inhibit Translation Elongation. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2019, 58, 5387–5391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, C.R.C.; Abdul-Majeed, S.; Cael, B.; Barta, S.K. Clinical Pharmacokinetics and Pharmacodynamics of Bortezomib. Clin. Pharmacokinet. 2018, 58, 157–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyer, M.L.; Milhollen, M.A.; Ciavarri, J.; Fleming, P.; Traore, T.; Sappal, D.; Huck, J.; Shi, J.; Gavin, J.; Brownell, J.; et al. A Small-Molecule Inhibitor of the Ubiquitin Activating Enzyme for Cancer Treatment. Nat. Med. 2018, 24, 186–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruan, J.; Liang, D.; Yan, W.; Zhong, Y.; Talley, D.C.; Rai, G.; Tao, D.; LeClair, C.A.; Simeonov, A.; Zhang, Y.; et al. A Small-Molecule Inhibitor and Degrader of the RNF5 Ubiquitin Ligase. Mol. Biol. Cell 2022, 33, ar120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zharkov, T.D.; Markov, O.V.; Zhukov, S.A.; Khodyreva, S.N.; Kupryushkin, M.S. Influence of Combinations of Lipophilic and Phosphate Backbone Modifications on Cellular Uptake of Modified Oligonucleotides. Molecules 2024, 29, 452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patutina, O.A.; Bazhenov, M.A.; Miroshnichenko, S.K.; Mironova, N.L.; Pyshnyi, D.V.; Vlassov, V.V.; Zenkova, M.A. Peptide-Oligonucleotide Conjugates Exhibiting Pyrimidine-X Cleavage Specificity Efficiently Silence MiRNA Target Acting Synergistically with RNase H. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 14990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patutina, O.A.; Bichenkova, E.V.; Miroshnichenko, S.K.; Mironova, N.L.; Trivoluzzi, L.T.; Burusco, K.K.; Bryce, R.A.; Vlassov, V.V.; Zenkova, M.A. MiRNases: Novel Peptide-Oligonucleotide Bioconjugates That Silence MiR-21 in Lymphosarcoma Cells. Biomaterials 2017, 122, 163–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Ridzon, D.A.; Broomer, A.J.; Zhou, Z.; Lee, D.H.; Nguyen, J.T.; Barbisin, M.; Xu, N.L.; Mahuvakar, V.R.; Andersen, M.R.; et al. Real-Time Quantification of MicroRNAs by Stem-Loop RT-PCR. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005, 30, e179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varkonyi-Gasic, E.; Hellens, R.P. Quantitative Stem-Loop RT-PCR for Detection of MicroRNAs. In RNAi and Plant Gene Function Analysis: Methods and Protocols; Methods in Molecular Biology; Humana Press: Totowa, NJ, USA, 2011; Volume 744, pp. 145–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perez-Riverol, Y.; Bandla, C.; Kundu, D.J.; Kamatchinathan, S.; Bai, J.; Hewapathirana, S.; John, N.S.; Prakash, A.; Walzer, M.; Wang, S.; et al. The PRIDE database at 20 years: 2025 update. Nucleic Acids Res. 2025, 53, D543–D553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bindea, G.; Mlecnik, B.; Hackl, H.; Charoentong, P.; Tosolini, M.; Kirilovsky, A.; Fridman, W.H.; Pagès, F.; Trajanoski, Z.; Galon, J. ClueGO: A Cytoscape Plug-in to Decipher Functionally Grouped Gene Ontology and Pathway Annotation Networks. Bioinformatics 2009, 25, 1091–1093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markov, A.V.; Odarenko, K.V.; Ilyina, A.A.; Zenkova, M.A. Uncovering the Anti-Angiogenic Effect of Semisynthetic Triterpenoid CDDO-Im on HUVECs by an Integrated Network Pharmacology Approach. Comput. Biol. Med. 2022, 141, 105034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.H.; Zhao, L.F.; Wang, H.F.; Wen, Y.T.; Jiang, K.K.; Mao, X.M.; Zhou, Z.Y.; Yao, K.T.; Geng, Q.S.; Guo, D.; et al. GenCLiP 3: Mining Human Genes’ Functions and Regulatory Networks from Pubmed Based on Co-Occurrences and Natural Language Processing. Bioinformatics 2020, 36, 1973–1975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krzywinski, M.; Schein, J.; Birol, I.; Connors, J.; Gascoyne, R.; Horsman, D.; Jones, S.J.; Marra, M.A. Circos: An Information Aesthetic for Comparative Genomics. Genome Res. 2009, 19, 1639–1645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cui, S.; Yu, S.; Huang, H.Y.; Lin, Y.C.D.; Huang, Y.; Zhang, B.; Xiao, J.; Zuo, H.; Wang, J.; Li, Z.; et al. MiRTarBase 2025: Updates to the Collection of Experimentally Validated MicroRNA-Target Interactions. Nucleic Acids Res. 2025, 53, D147–D156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agarwal, V.; Bell, G.W.; Nam, J.W.; Bartel, D.P. Predicting Effective MicroRNA Target Sites in Mammalian MRNAs. Elife 2015, 4, e05005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, Z.; Kang, B.; Li, C.; Chen, T.; Zhang, Z. GEPIA2: An Enhanced Web Server for Large-Scale Expression Profiling and Interactive Analysis. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019, 47, W556–W560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| µ-21 | ||

| Well-Studied | Moderate-to-Low Association with CRC and Associated Diseases | No Prior Links (Emerging Role in CRC) |

| CD44; HSP90AA1; CDK1; IDH1; HSPD1; MAD2L1 | eIF3F; NPM1; LAMB1; RPL31; RPA1; DKC1; NEDD8; DYNC1H1; RPLP0; RRP9; PSMD14; RPS20; EIF3H; GSPT1; PHF5A; PSMG1; PRPF4; DDX39B; DENR; COX5A; RPS14; HSPE1 | PFKL; NDUFS3; DENR; TUBB4B; EXOSC10; RPL37a; RPS7; RPS23; NUDC; SEC13; MRPS9; RPL32; EEFSEC; MAGOH; NOL11; RNPS1; RSL24D1; SNRPC; NXF1; MRPL27; PSMD3; RPS29; TUFM |

| µ-17 | ||

| Well-Studied | Moderate-to-Low Association with CRC and Associated Diseases | No Prior Links (Emerging Role in CRC) |

| RPSA; IDH1; SKP2; ALDH2; SOD2 | RPS2; MRPL11; RPL27; RPS4X; SNRPD2; TEX10; UQCRC1; ACAA1; EIF3C; COX5A; GLUD2; UQCRC2; ALDH7A1; RPL17; EIF2S3; POLR2A; SEC23A; RRP15; ECHS1; RPS15A; DNM2; ACADS; PES1; EIF3H; ATIC; GLUD1; EEF2 | RPS23; MRPL17; MRPS9; RPLP2; IF3L; MAGOH; MRPS15; IF3CL; MRPS24; MAGOHB; RPL17-C18orf32; ECHDC1; SNRPC; DRG1; WDR61; PSMD5; RBM42; MAK16 |

| µ-155 | ||

| Well-Studied | Moderate-to-Low Association with CRC and Associated Diseases | No Prior Links (Emerging Role in CRC) |

| CDH1; VDAC1; NPM1; FLNA; EIF4A3; IDH1 | TUBB; SNRPD2; EPN1; RPS9; NUP107; RBM39; OGDH; EIF3I; RPS4X; TUBA1B; RPL23A; GRWD1; ARPC2; EIF4A2; PSMD2; BOP1; RPL17; SKP1; SF3B3; RPL19; GAPDH; RPS20; PPP2CA | RPLP2; RPL32; IMP4; MRPS14; MRRF; EIF3L; MRPS9; RPL6; MRPS24; PSMB3; TRMT112; DLD; AP2A1; MRPL17; TUFM; RPL8; MAGOH; RNPS1;CLTA; DAP3; TCERG1 |

| Combi | ||

| Well-Studied | Moderate-to-Low Association with CRC and Associated Diseases | No Prior Links (Emerging Role in CRC) |

| RPS18; VCP; EEF1A1; NPM1; CCT3; TLN1; SRSF3; SOD1; HSPA5; PKM | CCT7; TSR1; EEF1B2; PSMB4; RPL23A; RANBP2; RPL7A; MRPL11; SNRPB; RPL19; RPS15; BOP1; RRP15; NIFK; UBA52; DCAF13; HMGN1; SYNCRIP; EIF1; SNRPN; RPS27A; BTF3 | RPL14; MRPL2; RPS23; IMP4; RPS16; EIF3L; RPS13; GFM1; MAK16; UBC; DNTTIP2; UBB; DRG1; NDUFS8; RPLP2; EIF1B; MRPL17; SRP54 |

| ASO | Sequence 5′-3′ |

| μ-17 | CμTμAμCμCμTμGμCμAμCμTμGμTμAμAμGμCμAμCμTμTμTμG |

| μ-21 | TμCμAμAμCμAμTμCμAμGμTμCμTμGμAμTμAμAμGμCμTμA |

| μ-155 | AμAμCμCμCμCμTμAμTμCμAμCμGμAμTμTμAμGμCμAμTμTμAμA |

| μ-Scr | CμAμAμGμTμCμTμCμGμTμAμTμGμTμAμGμTμGμGμTμT |

| FITC-μ-21 | FITC-TμCμAμAμCμAμTμCμAμGμTμCμTμGμAμTμAμAμGμCμTμA |

| Primer | Sequence 5′-3′ |

| Reverse transcription primers | |

| RT-mir-17 | GTCGTATCCAGTGCAGGGTCCGAGGTATTCGCACTGGATACGACCTACCTGCAC |

| RT-mir-155 | GTCGTATCCAGTGCAGGGTCCGAGGTATTCGCACTGGATACGACGACACCCCTATCA |

| RT-mir-21 | GTCGTATCCAGTGCAGGGTCCGAGGTATTCGCACTGGATACGACTCAACATCAG |

| RT-U6 | GTCGTATCCAGTGCAGGGTCCGAGGTATTCGCACTGGATACGACAAAAATATGGAACG |

| PCR primers | |

| mir-17-F | AGACAAAGTGCTTACAGTGC |

| mir-155-F | ACTTAATGCTAATTGTGATAGG |

| mir-21-F | AGACTAGCTTATCAGACTGA |

| U6-F | CTCGCTTCGGCAGCACA |

| Universal reverse | GTGCAGGGTCCGAGGT |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Miroshnichenko, S.K.; Patutina, O.A.; Markov, A.V.; Kupryushkin, M.S.; Vlassov, V.V.; Zenkova, M.A. Biological Performance and Molecular Mechanisms of Mesyl MicroRNA-Targeted Oligonucleotides in Colorectal Cancer Cells. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 11747. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311747

Miroshnichenko SK, Patutina OA, Markov AV, Kupryushkin MS, Vlassov VV, Zenkova MA. Biological Performance and Molecular Mechanisms of Mesyl MicroRNA-Targeted Oligonucleotides in Colorectal Cancer Cells. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2025; 26(23):11747. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311747

Chicago/Turabian StyleMiroshnichenko, Svetlana K., Olga A. Patutina, Andrey V. Markov, Maxim S. Kupryushkin, Valentin V. Vlassov, and Marina A. Zenkova. 2025. "Biological Performance and Molecular Mechanisms of Mesyl MicroRNA-Targeted Oligonucleotides in Colorectal Cancer Cells" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 26, no. 23: 11747. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311747

APA StyleMiroshnichenko, S. K., Patutina, O. A., Markov, A. V., Kupryushkin, M. S., Vlassov, V. V., & Zenkova, M. A. (2025). Biological Performance and Molecular Mechanisms of Mesyl MicroRNA-Targeted Oligonucleotides in Colorectal Cancer Cells. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 26(23), 11747. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311747