Anti-Inflammatory Properties of Resveratrol

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. A Brief Introductory Overview of Inflammation and Anti-Inflammatory Treatment

2.1. Inflammation

2.2. Typical Anti-Inflammatory Treatments

2.2.1. Non-Steroid Anti-Inflammatory Drugs (NSAIDs)

2.2.2. Glucocorticoids

3. Overall Characteristics of RSV

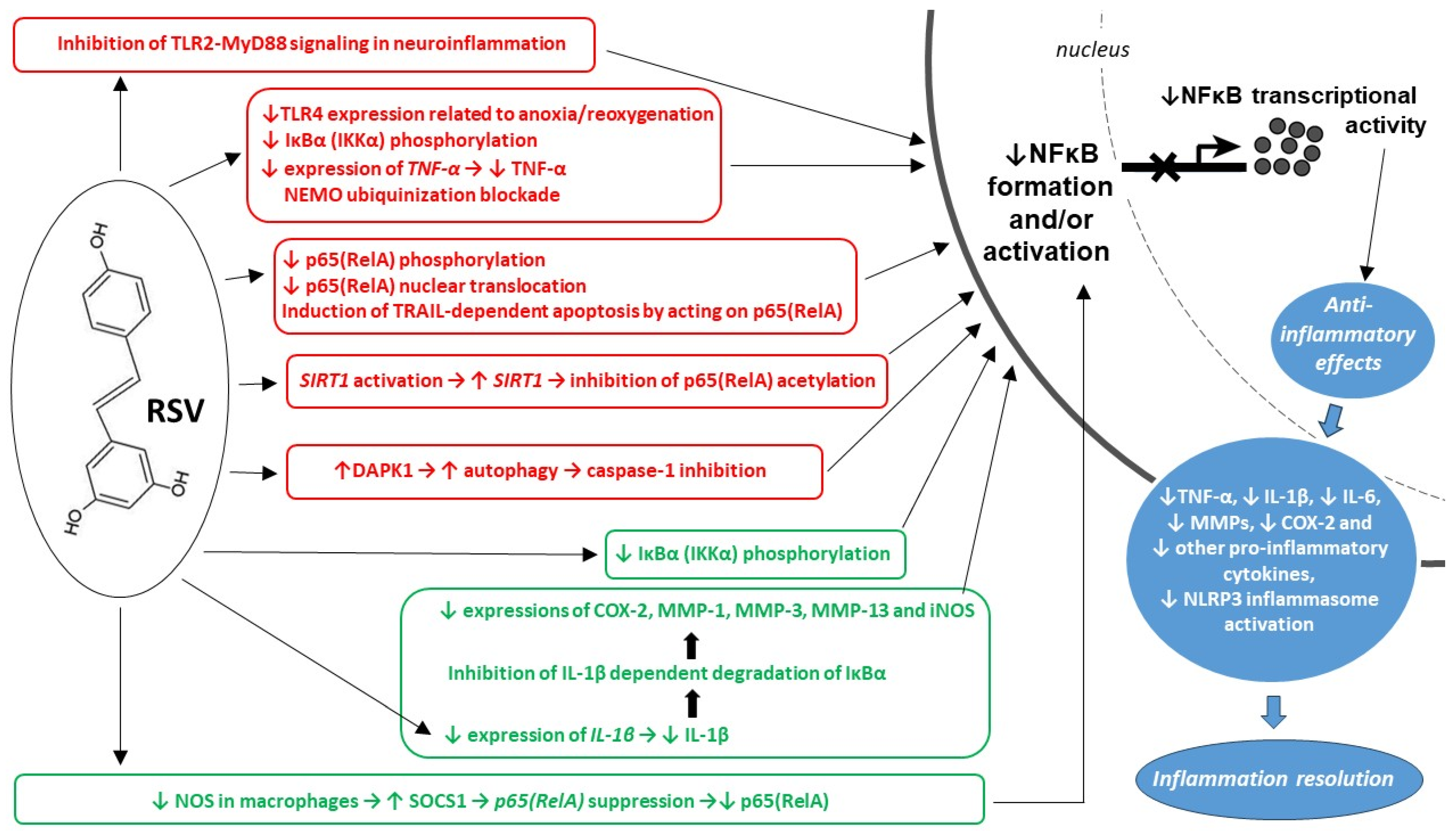

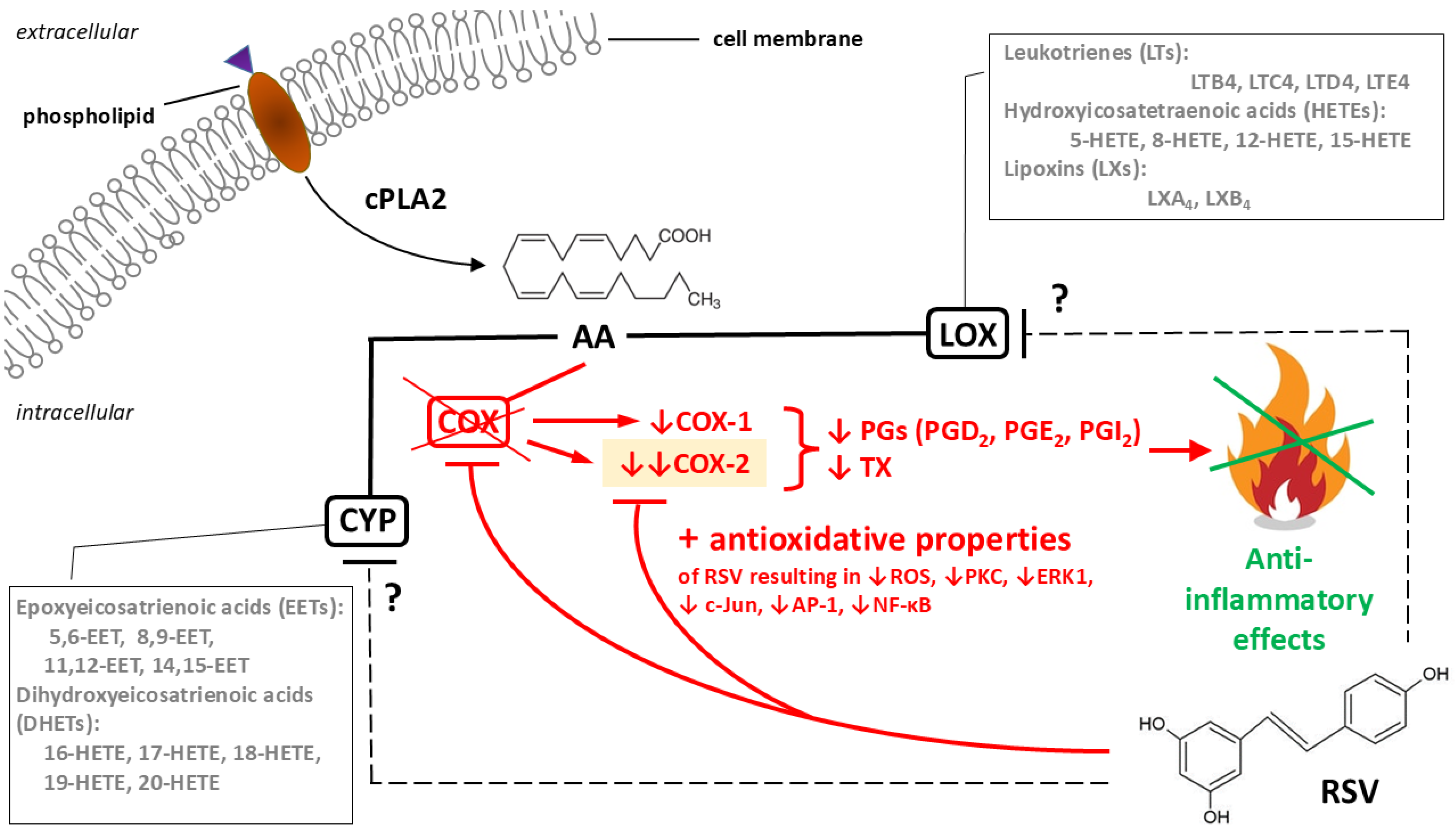

3.1. Mechanisms of RSV’s Anti-Inflammatory Actions

3.1.1. Cellular Response

3.1.2. Molecular Pathways

4. Considerations Related to the Therapeutic Usefulness of RSV

4.1. Notes on Dietary Recommendations

4.2. Problems with RSV Bioavailability

4.3. Issues Related to the Interpretation of RSV Activity Studies

5. Summary and Future Perspectives

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AA | arachidonic acid |

| AMPK | AMP-activated protein kinase |

| AP-1 | activator protein-1 |

| BMK1 | big mitogen-activated protein kinase 1, also known as extracellular signal-regulated kinase 5 (ERK5) or mitogen-activated protein kinase 7 (MAPK7) |

| cAMP | cyclic adenosine monophosphate |

| cGMP | cyclic guanosine monophosphate |

| CAT | catalase |

| c-Jun | a component of the transcription factor AP-1 |

| CNS | central nervous system |

| Con A | concavalin A |

| COX-1, COX-2 | cyclooxygenases 1 and 2, respectively |

| cPLA2 | cytosolic phospholipase A2 |

| CREB | cAMP response element-binding protein |

| CYP-450 | cytochrome P450 |

| DAMP | damage-associated molecular patterns |

| DAPK1 | death-associated protein kinase 1 |

| ER | endoplasmic reticulum |

| ERCC1 | the excision repair cross-complementation group 1 (protein) |

| ERK1/2 | extracellular signal-regulated kinases 1/2 |

| FDA | U.S. Food and Drug Administration |

| FOXP3 | forkhead box P3 transcription factor |

| GPX | glutathione peroxidase |

| H2O2 | hydrogen peroxide |

| HIF-1α | hypoxia-inducible factor 1 alpha |

| HO-1 | heme oxygenase 1 |

| IκBα kinase and IκBβ kinase | inhibitors of nuclear factor kappa B α and β, respectively |

| IFN-γ | interferon γ |

| IKK | IkappaB kinase or IκB kinase |

| IL-1α, IL-1β, IL-2, IL-6, IL-8, IL-12, IL-17 | interleukins: 1-alpha, 1-beta, 2, 6, 8, 12 and 17, respectively |

| iNOS | inducible nitric oxide synthase |

| JAK/STAT | Janus kinase-signal transduction and transcription activation |

| JNK | c-Jun N-terminal kinase |

| LOX | lipoxygenase |

| LPS | lipopolysaccharide |

| MAPK | mitogen-activated protein kinases |

| MCP-1 | monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 |

| MDA | malonyl dialdehyde |

| MMP-1, MMP-3 and MMP-13 | matrix metalloproteinases |

| mTOR | mechanistic target of rapamycin |

| MYD88 | myeloid differentiation primary response 88, an adaptor protein |

| NAD+ | nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide |

| NADPH | nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate |

| NEMO | nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells (NF-κB) essential modulator |

| NF-κB | nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells |

| NLC | nanostructured lipid carriers |

| NLRP3 inflammasome | nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain (NOD), leucine-rich repeat (LRR)-containing protein (NLR) family member 3 inflammasome |

| NO | nitric oxide |

| NOS | nitric oxide synthase |

| NOX4 | nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate oxidase type 4 |

| Nrf2 | nuclear factor erythroid 2 (NF-E2)-related factor 2 |

| NSAID | non-steroid anti-inflammatory drugs |

| p38 | class of mitogen-activated protein kinases |

| p65(RelA) | transcription factor p65, also known as nuclear factor NF-κB p65 subunit (RelA proto-oncogene) |

| PAMP | pathogen-associated molecular patterns |

| PEPCK | phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase |

| PGE2, PGD2, PGI2 | prostaglandins E2 D2 and I2, respectively |

| PI-3K | phosphoinositide 3-kinase |

| PIH | pregnancy-induced hypertension |

| PKC | protein kinase C |

| PMA | phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate, also known as 12-O-tetradecanoylphorbol 13-acetate (TPA) |

| PRR | pattern-recognizing receptors |

| RAGE | receptors for advanced glycation end products |

| ROS | reactive oxygen species |

| RSV | resveratrol |

| SIRT1 | sirtuin 1, an NAD+-dependent deacetylase |

| SLN | solid lipid nanoparticles |

| SOCS1 | suppressor of cytokine signaling 1 |

| SOD | superoxide dismutase TLR—toll-like receptors |

| TCR | T cell receptor |

| TLR2, TLR4 | toll-like receptor 2 and 4, respectively |

| TNF-α | tumor necrosis factor alpha |

| TX | thromboxane |

| TxA2 | thromboxane A2 |

| TPA | 12-O-tetradecanoylphorbol 13-acetate, also known as phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA) |

| TRAIL | tumor necrosis factor-related apoptosis-inducing ligand |

| UVB | ultraviolet B radiation |

| VEGF | vascular endothelial growth factor |

References

- Liu, X.; Zeng, T.; Zhang, E.; Bin, C.; Liu, Q.; Wu, K.; Luo, Y.; Wei, S. Plant-based bioactives and oxidative stress in reproduction: Anti-inflammatory and metabolic protection mechanisms. Front. Nutr. 2025, 12, 1650347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komorowska, J.; Wątroba, M.; Szukiewicz, D. Review of beneficial effects of resveratrol in neurodegenerative diseases such as Alzheimer’s disease. Adv. Med. Sci. 2020, 65, 415–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MHasbullah, A.; Binesh, A.; Venkatachalam, K. Resveratrol as a Regulator of Inflammation, Oxidative Stress, and Glucose Stability in Diabetes. Antiinflamm. Antiallergy Agents Med. Chem. 2025, 24, e18715230414089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawrence, T. The nuclear factor NF-kappaB pathway in inflammation. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2009, 1, a001651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Libby, P. Inflammatory mechanisms: The molecular basis of inflammation and disease. Nutr. Rev. 2007, 65, S140–S146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, W.H.; Fan, K.Y.; Sheng, Y.T.; Cai, W.R. Resveratrol Attenuates Inflammation in Acute Lung Injury through ROS-Triggered TXNIP/NLRP3 Pathway. Chin. J. Integr. Med. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grabowska, A.D.; Wątroba, M.; Witkowska, J.; Mikulska, A.; Sepúlveda, N.; Szukiewicz, D. Interplay between Systemic Glycemia and Neuroprotective Activity of Resveratrol in Modulating Astrocyte SIRT1 Response to Neuroinflammation. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 11640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Renke, G.; Fuschini, A.C.; Clivati, B.; Teixeira, L.M.; Cuyabano, M.L.; Erel, C.T.; Rosado, E.L. New Perspectives on the Use of Resveratrol in the Treatment of Metabolic and Estrogen-Dependent Conditions Through Hormonal Modulation and Anti-Inflammatory Effects. Curr. Issues Mol. Biol. 2025, 47, 692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yin, Y.; Jia, N.; Luo, H.; Feng, X.; He, X.; Huang, J.; Wang, F. Protective effects and mechanism of resveratrol in animal models of pulmonary fibrosis: A preclinical systematic review and meta-analysis. Front. Pharmacol. 2025, 16, 1666698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walle, T. Bioavailability of resveratrol. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2011, 1215, 9–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunnumakkara, A.B.; Sailo, B.L.; Banik, K.; Harsha, C.; Prasad, S.; Gupta, S.C.; Bharti, A.C.; Aggarwal, B.B. Chronic diseases, inflammation, and spices: How are they linked? J. Transl. Med. 2018, 16, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Sá Coutinho, D.; Pacheco, M.T.; Frozza, R.L.; Bernardi, A. Anti-Inflammatory Effects of Resveratrol: Mechanistic Insights. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 1812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Munn, L.L. Cancer and inflammation. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Syst. Biol. Med. 2017, 9, e1370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Linthout, S.; Tschöpe, C. Inflammation-Cause or Consequence of Heart Failure or Both? Curr. Heart Fail. Rep. 2017, 14, 251–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Deng, H.; Cui, H.; Fang, J.; Zuo, Z.; Deng, J.; Li, Y.; Wang, X.; Zhao, L. Inflammatory responses and inflammation-associated diseases in organs. Oncotarget 2017, 9, 7204–7218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serhan, C.N. Treating inflammation and infection in the 21st century: New hints from decoding resolution mediators and mechanisms. FASEB J. 2017, 31, 1273–1288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robb, C.T.; Regan, K.H.; Dorward, D.A.; Rossi, A.G. Key mechanisms governing resolution of lung inflammation. Semin. Immunopathol. 2016, 38, 425–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slavich, G.M.; Irwin, M.R. From stress to inflammation and major depressive disorder: A social signal transduction theory of depression. Psychol. Bull. 2014, 140, 774–815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pelaia, G.; Vatrella, A.; Busceti, M.T.; Gallelli, L.; Calabrese, C.; Terracciano, R.; Maselli, R. Cellular mechanisms underlying eosinophilic and neutrophilic airway inflammation in asthma. Mediat. Inflamm. 2015, 2015, 879783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esser, N.; Legrand-Poels, S.; Piette, J.; Scheen, A.J.; Paquot, N. Inflammation as a link between obesity, metabolic syndrome and type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 2014, 105, 141–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heneka, M.T.; Carson, M.J.; El Khoury, J.; Landreth, G.E.; Brosseron, F.; Feinstein, D.L.; Jacobs, A.H.; Wyss-Coray, T.; Vitorica, J.; Ransohoff, R.M.; et al. Neuroinflammation in Alzheimer’s disease. Lancet Neurol. 2015, 14, 388–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siti, H.N.; Kamisah, Y.; Kamsiah, J. The role of oxidative stress, antioxidants and vascular inflammation in cardiovascular disease (a review). Vasc. Pharmacol. 2015, 71, 40–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szukiewicz, D. Molecular Mechanisms for the Vicious Cycle between Insulin Resistance and the Inflammatory Response in Obesity. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 9818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakamura, K.; Smyth, M.J. Targeting cancer-related inflammation in the era of immunotherapy. Immunol. Cell Biol. 2017, 95, 325–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bindu, S.; Mazumder, S.; Bandyopadhyay, U. Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and organ damage: A current perspective. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2020, 180, 114147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazumder, S.; Bindu, S.; Debsharma, S.; Bandyopadhyay, U. Induction of mitochondrial toxicity by non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs): The ultimate trade-off governing the therapeutic merits and demerits of these wonder drugs. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2024, 228, 116283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kreutzinger, V.; Ziegeler, K.; Luitjens, J.; Joseph, G.B.; Lynch, J.; Lane, N.E.; McCulloch, C.E.; Nevitt, M.; Link, T.M. Limited effects of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) on imaging outcomes in osteoarthritis: Observational data from the osteoarthritis initiative (OAI). BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 2025, 26, 939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Traoré, O.; Diarra, A.S.; Kassogué, O.; Abu, T.; Maïga, A.; Kanté, M. The clinical and endoscopic aspects of peptic ulcers secondary to the use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs of various origins. Pan. Afr. Med. J. 2021, 38, 170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badri, W.; Miladi, K.; Nazari, Q.A.; Greige-Gerges, H.; Fessi, H.; Elaissari, A. Encapsulation of NSAIDs for inflammation management: Overview, progress, challenges and prospects. Int. J. Pharm. 2016, 515, 757–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldkind, L.; Laine, L. A systematic review of NSAIDs withdrawn from the market due to hepatotoxicity: Lessons learned from the bromfenac experience. Pharmacoepidemiol. Drug Saf. 2006, 15, 213–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brzezińska, O.; Cieplucha, A.; Słodkowski, K.; Lewandowska-Polak, A.; Makowska, J. The incidence of hypersensitivity to non-steroid anti-inflammatory drugs in the group of patients with rheumatoid musculoskeletal disorders: The cross-sectional study. Rheumatol. Int. 2025, 45, 82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramamoorthy, S.; Cidlowski, J.A. Corticosteroids: Mechanisms of Action in Health and Disease. Rheum. Dis. Clin. N. Am. 2016, 42, 15–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meduri, G.U.; Psarra, A.G. The Glucocorticoid System: A Multifaceted Regulator of Mitochondrial Function, Endothelial Homeostasis, and Intestinal Barrier Integrity. In Seminars in Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine; Thieme Medical Publishers, Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kadmiel, M.; Cidlowski, J.A. Glucocorticoid receptor signaling in health and disease. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 2013, 34, 518–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whirledge, S.; DeFranco, D.B. Glucocorticoid Signaling in Health and Disease: Insights From Tissue-Specific GR Knockout Mice. Endocrinology 2018, 159, 46–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.; Zhang, T.N.; Knight, J.K.; Goodwin, J.E. The Glucocorticoid Receptor in Cardiovascular Health and Disease. Cells 2019, 8, 1227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Auger, J.P.; Zimmermann, M.; Faas, M.; Stifel, U.; Chambers, D.; Krishnacoumar, B.; Taudte, R.V.; Grund, C.; Erdmann, G.; Scholtysek, C.; et al. Metabolic rewiring promotes anti-inflammatory effects of glucocorticoids. Nature 2024, 629, 184–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cummins, C.L.; Goldstein, I. New anti-inflammatory mechanism of glucocorticoids uncovered. Trends Endocrinol. Metab. 2025, 36, 99–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barnes, P.J. Glucocorticoids. Chem. Immunol. Allergy 2014, 100, 311–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oray, M.; Abu Samra, K.; Ebrahimiadib, N.; Meese, H.; Foster, C.S. Long-term side effects of glucocorticoids. Expert Opin. Drug Saf. 2016, 15, 457–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radeva, L.; Yoncheva, K. Resveratrol-A Promising Therapeutic Agent with Problematic Properties. Pharmaceutics 2025, 17, 134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komorowska, J.; Wątroba, M.; Bednarzak, M.; Grabowska, A.D.; Szukiewicz, D. Anti-Inflammatory Action of Resveratrol in the Central Nervous System in Relation to Glucose Concentration—An In Vitro Study on a Blood-Brain Barrier Model. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 3110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, P.; Li, Z.; Song, Y.; Zhang, B.; Fan, C. Resveratrol-driven macrophage polarization: Unveiling mechanisms and therapeutic potential. Front. Pharmacol. 2025, 15, 1516609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de la Lastra, C.A.; Villegas, I. Resveratrol as an anti-inflammatory and anti-aging agent: Mechanisms and clinical implications. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2005, 49, 405–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meng, T.; Xiao, D.; Muhammed, A.; Deng, J.; Chen, L.; He, J. Anti-Inflammatory Action and Mechanisms of Resveratrol. Molecules 2021, 26, 229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malaguarnera, L. Influence of Resveratrol on the Immune Response. Nutrients 2019, 11, 946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alesci, A.; Nicosia, N.; Fumia, A.; Giorgianni, F.; Santini, A.; Cicero, N. Resveratrol and Immune Cells: A Link to Improve Human Health. Molecules 2022, 27, 424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gramatyka, M. Time Does Matter: The Cellular Response to Resveratrol Varies Depending on the Exposure Duration. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 5542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ren, Z.Q.; Zheng, S.Y.; Sun, Z.; Luo, Y.; Wang, Y.T.; Yi, P.; Li, Y.S.; Huang, C.; Xiao, W.F. Resveratrol: Molecular Mechanisms, Health Benefits, and Potential Adverse Effects. MedComm 2025, 6, e70252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tomé-Carneiro, J.; Larrosa, M.; Yáñez-Gascón, M.J.; Dávalos, A.; Gil-Zamorano, J.; Gonzálvez, M.; García-Almagro, F.J.; Ruiz Ros, J.A.; Tomás-Barberán, F.A.; Espín, J.C.; et al. One-year supplementation with a grape extract containing resveratrol modulates inflammatory-related microRNAs and cytokines expression in peripheral blood mononuclear cells of type 2 diabetes and hypertensive patients with coronary artery disease. Pharmacol. Res. 2013, 72, 69–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalil, A.; Al-Massarani, G.; Aljapawe, A.; Ekhtiar, A.; Bakir, M.A. Resveratrol Modulates the Inflammatory Profile of Immune Responses and Circulating Endothelial Cells’ (CECs’) Population During Acute Whole Body Gamma Irradiation. Front. Pharmacol. 2020, 11, 528400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, Y.; Huang, S.L.; Li, H.; Cui, Y.L.; Li, D. Resveratrol attenuates inflammation by regulating macrophage polarization via inhibition of toll-like receptor 4/MyD88 signaling pathway. Pharmacogn. Mag. 2021, 17, 321–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Liu, Q.; Guo, X.; Xiang, L.; Zhao, G. Resveratrol attenuates IL 33 induced mast cell inflammation associated with inhibition of NF κB activation and the P38 signaling pathway. Mol. Med. Rep. 2020, 21, 1658–1666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kubota, S.; Kurihara, T.; Mochimaru, H.; Satofuka, S.; Noda, K.; Ozawa, Y.; Oike, Y.; Ishida, S.; Tsubota, K. Prevention of ocular inflammation in endotoxin-induced uveitis with resveratrol by inhibiting oxidative damage and nuclear factor-kappaB activation. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2009, 50, 3512–3519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.M.; Wei, R.M.; Zhang, M.Y.; Zhang, K.X.; Zhang, J.Y.; Fang, S.K.; Ge, Y.J.; Kong, X.Y.; Chen, G.H.; Li, X.Y. Resveratrol ameliorates maternal immune activation-associated cognitive impairment in adult male offspring by relieving inflammation and improving synaptic dysfunction. Front. Behav. Neurosci. 2023, 17, 1271653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moussa, C.; Hebron, M.; Huang, X.; Ahn, J.; Rissman, R.A.; Aisen, P.S.; Turner, R.S. Resveratrol regulates neuro-inflammation and induces adaptive immunity in Alzheimer’s disease. J. Neuroinflammation. 2017, 14, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, P.; Jin, Y.; Sun, J.; Zhou, X. The efficacy of resveratrol supplementation on inflammation and oxidative stress in type-2 diabetes mellitus patients: Randomized double-blind placebo meta-analysis. Front. Endocrinol. 2025, 15, 1463027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramdani, L.H.; Bachari, K. Potential therapeutic effects of Resveratrol against SARS-CoV-2. Acta Virol. 2020, 64, 276–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oliveira, A.L.B.; Monteiro, V.V.S.; Navegantes-Lima, K.C.; Reis, J.F.; Gomes, R.S.; Rodrigues, D.V.S.; Gaspar, S.L.F.; Monteiro, M.C. Resveratrol Role in Autoimmune Disease—A Mini-Review. Nutrients 2017, 9, 1306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shahcheraghi, S.H.; Salemi, F.; Small, S.; Syed, S.; Salari, F.; Alam, W.; Cheang, W.S.; Saso, L.; Khan, H. Resveratrol regulates inflammation and improves oxidative stress via Nrf2 signaling pathway: Therapeutic and biotechnological prospects. Phytother. Res. 2023, 37, 1590–1605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yasmin, T.; Menon, S.N.; Pandey, A.; Siddiqua, S.; Kuddus, S.A.; Rahman, M.M.; Khan, F.; Hoque, N.; Rana, M.S.; Subhan, N.; et al. Resveratrol attenuates hepatic oxidative stress and preserves gut mucosal integrity in high-fat diet-fed rats by modulating antioxidant and anti-inflammatory pathways. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 25162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nwachukwu, J.C.; Srinivasan, S.; Bruno, N.E.; Parent, A.A.; Hughes, T.S.; Pollock, J.A.; Gjyshi, O.; Cavett, V.; Nowak, J.; Garcia-Ordonez, R.D.; et al. Resveratrol modulates the inflammatory response via an estrogen receptor-signal integration network. eLife 2014, 3, e02057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farkhondeh, T.; Folgado, S.L.; Pourbagher-Shahri, A.M.; Ashrafizadeh, M.; Samarghandian, S. The therapeutic effect of resveratrol: Focusing on the Nrf2 signaling pathway. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2020, 127, 110234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Shen, Y.; Xiao, H.; Sun, W. Resveratrol attenuates rotenone-induced inflammation and oxidative stress via STAT1 and Nrf2/Keap1/SLC7A11 pathway in a microglia cell line. Pathol. Res. Pract. 2021, 225, 153576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tshivhase, A.M.; Matsha, T.; Raghubeer, S. Resveratrol attenuates high glucose-induced inflammation and improves glucose metabolism in HepG2 cells. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 1106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harwansh, R.K.; Yadav, P.; Deshmukh, R. Current Insight into Novel Delivery Approaches of Resveratrol for Improving Therapeutic Efficacy and Bioavailability with its Clinical Updates. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2023, 29, 2921–2939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, Z.; Wang, L.; Cui, J.; Huoc, Z.; Xue, J.; Cui, H.; Mao, Q.; Yang, R. Resveratrol inhibits NF-kB signaling through suppression of p65 and IkappaB kinase activities. Pharmazie 2013, 68, 689–694. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, X.; Wang, Y.; Xiao, C.; Wei, Z.; Wang, J.; Yang, Z.; Fu, Y. Resveratrol inhibits LPS-induced mice mastitis through attenuating the MAPK and NF-κB signaling pathway. Microb. Pathog. 2017, 107, 462–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Chen, K.; Yu, J.; Wang, X.; Li, Q.; Lv, F.; Shen, H.; Pei, L. Presynaptic Caytaxin prevents apoptosis via deactivating DAPK1 in the acute phase of cerebral ischemic stroke. Exp. Neurol. 2020, 329, 113303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chuang, Y.T.; Fang, L.W.; Lin-Feng, M.H.; Chen, R.H.; Lai, M.Z. The tumor suppressor death-associated protein kinase targets to TCR-stimulated NF-kappa B activation. J. Immunol. 2008, 180, 3238–3249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, T.; Wu, Y.N.; Wang, H.; Ma, J.Y.; Zhai, S.S.; Duan, J. Dapk1 improves inflammation, oxidative stress and autophagy in LPS-induced acute lung injury via p38MAPK/NF-κB signaling pathway. Mol. Immunol. 2020, 120, 13–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lai, M.Z.; Chen, R.H. Regulation of inflammation by DAPK. Apoptosis 2014, 19, 357–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, M.S.; Kim, Y.; Jung, J.Y.; Yang, S.H.; Lee, T.R.; Shin, D.W. Resveratrol induces autophagy through death-associated protein kinase 1 (DAPK1) in human dermal fibroblasts under normal culture conditions. Exp. Dermatol. 2013, 22, 491–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, L.M.; Zong, Y.; Sun, L.; Guo, J.Z.; Zhang, W.; He, Y.; Song, R.; Wang, W.M.; Xiao, C.J.; Lu, D. Resveratrol inhibits inflammatory responses via the mammalian target of rapamycin signaling pathway in cultured LPS-stimulated microglial cells. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e32195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Li, F.; Wang, F.; Li, J.; Lin, C.; Du, J. Resveratrol inhibits the proliferation of A549 cells by inhibiting the expression of COX-2. Onco Targets Ther. 2018, 11, 2981–2989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magrone, T.; Magrone, M.; Russo, M.A.; Jirillo, E. Recent Advances on the Anti-Inflammatory and Antioxidant Properties of Red Grape Polyphenols: In Vitro and In Vivo Studies. Antioxidants 2019, 9, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandrasekharan, N.V.; Dai, H.; Roos, K.L.; Evanson, N.K.; Tomsik, J.; Elton, T.S.; Simmons, D.L. COX-3, a cyclooxygenase-1 variant inhibited by acetaminophen and other analgesic/antipyretic drugs: Cloning, structure, and expression. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2002, 99, 13926–13931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinchuk, J.E.; Liu, R.Q.; Trzaskos, J.M. COX-3: In the wrong frame in mind. Immunol. Lett. 2003, 86, 121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmassmann, A.; Peskar, B.M.; Stettler, C.; Netzer, P.; Stroff, T.; Flogerzi, B.; Halter, F. Effects of inhibition of prostaglandin endoperoxide synthase-2 in chronic gastro-intestinal ulcer models in rats. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1998, 123, 795–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vane, J.R.; Botting, R.M. Mechanism of action of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. Am. J. Med. 1998, 104, 2S–8S; discussion 21S–22S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenhough, A.; Smartt, H.J.; Moore, A.E.; Roberts, H.R.; Williams, A.C.; Paraskeva, C.; Kaidi, A. The COX-2/PGE2 pathway: Key roles in the hallmarks of cancer and adaptation to the tumour microenvironment. Carcinogenesis 2009, 30, 377–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, M.; Cai, L.; Udeani, G.O.; Slowing, K.V.; Thomas, C.F.; Beecher, C.W.; Fong, H.H.; Farnsworth, N.R.; Kinghorn, A.D.; Mehta, R.G.; et al. Cancer chemopreventive activity of resveratrol, a natural product derived from grapes. Science 1997, 275, 218–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szewczuk, L.M.; Forti, L.; Stivala, L.A.; Penning, T.M. Resveratrol is a peroxidase-mediated inactivator of COX-1 but not COX-2: A mechanistic approach to the design of COX-1 selective agents. J. Biol. Chem. 2004, 279, 22727–22737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-García, J.; Micol, V.; de Godos, A.; Gómez-Fernández, J.C. The cancer chemopreventive agent resveratrol is incorporated into model membranes and inhibits protein kinase C alpha activity. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 1999, 372, 382–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorai, T.; Aggarwal, B.B. Role of chemopreventive agents in cancer therapy. Cancer Lett. 2004, 215, 129–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kundu, J.K.; Chun, K.S.; Kim, S.O.; Surh, Y.J. Resveratrol inhibits phorbol ester-induced cyclooxygenase-2 expression in mouse skin: MAPKs and AP-1 as potential molecular targets. Biofactors 2004, 21, 33–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, C.O.; Jeon, B.T.; Shin, H.J.; Jeong, E.A.; Chang, K.C.; Lee, J.E.; Lee, D.H.; Kim, H.J.; Kang, S.S.; Cho, G.J.; et al. Resveratrol activates AMPK and suppresses LPS-induced NF-κB-dependent COX-2 activation in RAW 264.7 macrophage cells. Anat. Cell Biol. 2011, 44, 194–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bode, A.M.; Dong, Z. Mitogen-activated protein kinase activation in UV-induced signal transduction. Sci. STKE 2003, 2003, RE2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bode, A.M.; Dong, Z. Targeting signal transduction pathways by chemopreventive agents. Mutat. Res. 2004, 555, 33–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, T.W.; Michniewicz, M.; Bergmann, D.C.; Wang, Z.Y. Brassinosteroid regulates stomatal development by GSK3-mediated inhibition of a MAPK pathway. Nature 2012, 482, 419–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, G.L.; Lapadat, R. Mitogen-activated protein kinase pathways mediated by ERK, JNK, and p38 protein kinases. Science 2002, 298, 1911–1912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chun, K.S.; Surh, Y.J. Signal transduction pathways regulating cyclooxygenase-2 expression: Potential molecular targets for chemoprevention. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2004, 68, 1089–1100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raingeaud, J.; Gupta, S.; Rogers, J.S.; Dickens, M.; Han, J.; Ulevitch, R.J.; Davis, R.J. Pro-inflammatory cytokines and environmental stress cause p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase activation by dual phosphorylation on tyrosine and threonine. J. Biol. Chem. 1995, 270, 7420–7426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koul, H.K.; Pal, M.; Koul, S. Role of p38 MAP Kinase Signal Transduction in Solid Tumors. Genes Cancer 2013, 4, 342–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, M.Y.; Hsiao, G.; Liu, C.L.; Fong, T.H.; Lin, K.H.; Chou, D.S.; Sheu, J.R. Inhibitory mechanisms of resveratrol in platelet activation: Pivotal roles of p38 MAPK and NO/cyclic GMP. Br. J. Haematol. 2007, 139, 475–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, M.J.; Meng, N. Resveratrol acts via the mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) pathway to protect retinal ganglion cells from apoptosis induced by hydrogen peroxide. Bioengineered 2021, 12, 4878–4886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, G.; Chang, C.C.; Yang, Y.; Yuan, L.; Xu, L.; Ho, C.T.; Li, S. Resveratrol Alleviates Rheumatoid Arthritis via Reducing ROS and Inflammation, Inhibiting MAPK Signaling Pathways, and Suppressing Angiogenesis. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2018, 66, 12953–12960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, H.; Chen, Q.; Kong, D.L.; Guo, J.; Wang, Q.; Yu, S.Y. Effect of resveratrol on gliotransmitter levels and p38 activities in cultured astrocytes. Neurochem. Res. 2011, 36, 17–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, W.; Yang, E.; Ye, J.; Han, W.; Du, Z.L. Resveratrol protects neuronal cells from isoflurane-induced inflammation and oxidative stress-associated death by attenuating apoptosis via Akt/p38 MAPK signaling. Exp. Ther. Med. 2018, 15, 1568–1573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karin, M. The regulation of AP-1 activity by mitogen-activated protein kinases. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 1996, 351, 127–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eferl, R.; Wagner, E.F. AP-1: A double-edged sword in tumorigenesis. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2003, 3, 859–868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manna, S.K.; Mukhopadhyay, A.; Aggarwal, B.B. Resveratrol suppresses TNF-induced activation of nuclear transcription factors NF-kappa B, activator protein-1, and apoptosis: Potential role of reactive oxygen intermediates and lipid peroxidation. J. Immunol. 2000, 164, 6509–6519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subbaramaiah, K.; Chung, W.J.; Michaluart, P.; Telang, N.; Tanabe, T.; Inoue, H.; Jang, M.; Pezzuto, J.M.; Dannenberg, A.J. Resveratrol inhibits cyclooxygenase-2 transcription and activity in phorbol ester-treated human mammary epithelial cells. J. Biol. Chem. 1998, 273, 21875–21882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shen, F.; Chen, S.J.; Dong, X.J.; Zhong, H.; Li, Y.T.; Cheng, G.F. Suppression of IL-8 gene transcription by resveratrol in phorbol ester treated human monocytic cells. J. Asian Nat. Prod. Res. 2003, 5, 151–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Donnelly, L.E.; Newton, R.; Kennedy, G.E.; Fenwick, P.S.; Leung, R.H.; Ito, K.; Russell, R.E.; Barnes, P.J. Anti-inflammatory effects of resveratrol in lung epithelial cells: Molecular mechanisms. Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell. Mol. Physiol. 2004, 287, L774–L783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yao, Y.; Li, J.; Niu, Y.; Yu, J.Q.; Yan, L.; Miao, Z.H.; Zhao, X.X.; Li, Y.J.; Yao, W.X.; Zheng, P.; et al. Resveratrol inhibits oligomeric Aβ-induced microglial activation via NADPH oxidase. Mol. Med. Rep. 2015, 12, 6133–6139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diaz-Gerevini, G.T.; Repossi, G.; Dain, A.; Tarres, M.C.; Das, U.N.; Eynard, A.R. Beneficial action of resveratrol: How and why? Nutrition 2016, 32, 174–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishigaki, A.; Kido, T.; Kida, N.; Kakita-Kobayashi, M.; Tsubokura, H.; Hisamatsu, Y.; Okada, H. Resveratrol protects mitochondrial quantity by activating SIRT1/PGC-1α expression during ovarian hypoxia. Reprod. Med. Biol. 2020, 19, 189–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Wu, D.; Wu, Q.; Wu, Y.; Guo, Z.; Wang, L.; Wang, Y.; Zeng, Q.; Shi, L.; Shi, B.; et al. The Role of Hepatic SIRT1: From Metabolic Regulation to Immune Modulation and Multi-target Therapeutic Strategies. J. Clin. Transl. Hepatol. 2025, 13, 878–898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, X.; Chen, M.; Wu, J.; Song, R. Research progress of SIRTs activator resveratrol and its derivatives in autoimmune diseases. Front. Immunol. 2024, 15, 1390907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarke, T.L.; Mostoslavsky, R. Resveratrol: Friend or Foe? Mol. Cell 2020, 79, 705–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omraninava, M.; Razi, B.; Aslani, S.; Imani, D.; Jamialahmadi, T.; Sahebkar, A. Effect of resveratrol on inflammatory cytokines: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2021, 908, 174380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rafe, T.; Shawon, P.A.; Salem, L.; Chowdhury, N.I.; Kabir, F.; Bin Zahur, S.M.; Akhter, R.; Noor, H.B.; Mohib, M.M.; Sagor, M.A.T. Preventive Role of Resveratrol Against Inflammatory Cytokines and Related Diseases. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2019, 25, 1345–1371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lanzilli, G.; Cottarelli, A.; Nicotera, G.; Guida, S.; Ravagnan, G.; Fuggetta, M.P. Anti-inflammatory effect of resveratrol and polydatin by in vitro IL-17 modulation. Inflammation 2012, 35, 240–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Zhou, Z.X.; Sun, L.X.; Li, X.; Xu, Z.M.; Chen, M.; Zhao, G.L.; Jiang, Z.Z.; Zhang, L.Y. Resveratrol effectively attenuates α-naphthyl-isothiocyanate-induced acute cholestasis and liver injury through choleretic and anti-inflammatory mechanisms. Acta Pharmacol. Sin. 2014, 35, 1527–1536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akash, M.S.H.; Fatima, M.; Rehman, K.; Rehman, Q.; Chauhdary, Z.; Nadeem, A.; Mir, T.M. Resveratrol Mitigates Bisphenol A-Induced Metabolic Disruptions: Insights from Experimental Studies. Molecules 2023, 28, 5865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghahremani, H.; Bahramzadeh, A.; Bolandnazar, K.; Emamgholipor, S.; Hosseini, H.; Meshkani, R. Resveratrol as a Potential Protective Compound Against Metabolic Inflammation. Acta Biochim. Iran. 2023, 1, 50–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faisal, Z.; Mazhar, A.; Batool, S.A.; Akram, N.; Hassan, M.; Khan, M.U.; Afzaal, M.; Hassan, U.U.; Shah, Y.A.; Desta, D.T. Exploring the multimodal health-promoting properties of resveratrol: A comprehensive review. Food Sci. Nutr. 2024, 12, 2240–2258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salehi, B.; Mishra, A.P.; Nigam, M.; Sener, B.; Kilic, M.; Sharifi-Rad, M.; Fokou, P.V.T.; Martins, N.; Sharifi-Rad, J. Resveratrol: A Double-Edged Sword in Health Benefits. Biomedicines 2018, 6, 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.; Hu, Z.; Song, X.; Cui, Q.; Fu, Q.; Jia, R.; Zou, Y.; Li, L.; Yin, Z. Analgesic and Anti-Inflammatory Activities of Resveratrol through Classic Models in Mice and Rats. Evid. Based Complement. Altern. Med. 2017, 2017, 5197567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, M.; Yagnik, U.; Raninga, I.; Banerjee, D. Metabolic regulation of obesity by naturally occurring compounds: Mechanisms and therapeutic potential. Front. Endocrinol. 2025, 16, 1655875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benbaibeche, H.; Boumehira, A.Z.; Khan, N.A. Natural bioactive compounds and their mechanisms of action in the management of obesity: A narrative review. Front. Nutr. 2025, 12, 1614947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pervaiz, S.; Holme, A.L. Resveratrol: Its biologic targets and functional activity. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2009, 11, 2851–2897, Erratum in Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2010, 12, 322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baur, J.A.; Sinclair, D.A. Therapeutic potential of resveratrol: The in vivo evidence. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2006, 5, 493–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murillo-Cancho, A.F.; Lozano-Paniagua, D.; Nievas-Soriano, B.J. Dietary and Pharmacological Modulation of Aging-Related Metabolic Pathways: Molecular Insights, Clinical Evidence, and a Translational Model. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 9643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, M.R.; Ajaj, R.; Rauf, A.; Shanta, S.S.; Al-Imran, M.I.K.; Fakir, M.N.H.; Gianoncelli, A.; Ribaudo, G. The Potential of Resveratrol as an Anticancer Agent: Updated Overview of Mechanisms, Applications, and Perspectives. Arch. Pharm. 2025, 358, e70109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Calabrese, E.J.; Mattson, M.P.; Calabrese, V. Dose response biology: The case of resveratrol. Hum. Exp. Toxicol. 2010, 29, 1034–1037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, X.; Liao, W.; Xia, H.; Wang, S.; Sun, G. The Effect of Resveratrol on Blood Lipid Profile: A Dose-Response Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Nutrients 2022, 14, 3755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erdogan, C.S.; Vang, O. Challenges in Analyzing the Biological Effects of Resveratrol. Nutrients 2016, 8, 353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rotches-Ribalta, M.; Andres-Lacueva, C.; Estruch, R.; Escribano, E.; Urpi-Sarda, M. Pharmacokinetics of resveratrol metabolic profile in healthy humans after moderate consumption of red wine and grape extract tablets. Pharmacol. Res. 2012, 66, 375–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robertson, I.; Wai Hau, T.; Sami, F.; Sajid Ali, M.; Badgujar, V.; Murtuja, S.; Saquib Hasnain, M.; Khan, A.; Majeed, S.; Tahir Ansari, M. The science of resveratrol, formulation, pharmacokinetic barriers and its chemotherapeutic potential. Int. J. Pharm. 2022, 618, 121605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Liu, T.; Chen, P.; Yin, D.; Zhang, H.; Qiu, X.; Zou, S.; Li, W. Pharmacokinetic evaluation of two oral Resveratrol formulations in a randomized, open-label, crossover study in healthy fasting subjects. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 24515, Erratum in Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 35581. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-23692-7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salla, M.; Karaki, N.; El Kaderi, B.; Ayoub, A.J.; Younes, S.; Abou Chahla, M.N.; Baksh, S.; El Khatib, S. Enhancing the Bioavailability of Resveratrol: Combine It, Derivatize It, or Encapsulate It? Pharmaceutics 2024, 16, 569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kemper, C.; Benham, D.; Brothers, S.; Wahlestedt, C.; Volmar, C.H.; Bennett, D.; Hayward, M. Safety and pharmacokinetics of a highly bioavailable resveratrol preparation (JOTROL TM). AAPS Open 2022, 8, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subramanian, L.; Youssef, S.; Bhattacharya, S.; Kenealey, J.; Polans, A.S.; van Ginkel, P.R. Resveratrol: Challenges in translation to the clinic--a critical discussion. Clin. Cancer Res. 2010, 16, 5942–5948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gambini, J.; Inglés, M.; Olaso, G.; Lopez-Grueso, R.; Bonet-Costa, V.; Gimeno-Mallench, L.; Mas-Bargues, C.; Abdelaziz, K.M.; Gomez-Cabrera, M.C.; Vina, J.; et al. Properties of Resveratrol: In Vitro and In Vivo Studies about Metabolism, Bioavailability, and Biological Effects in Animal Models and Humans. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2015, 2015, 837042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zu, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, W.; Zhao, X.; Han, X.; Wang, K.; Ge, Y. Preparation and in vitro/in vivo evaluation of resveratrol-loaded carboxymethyl chitosan nanoparticles. Drug Deliv. 2016, 23, 981–991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chimento, A.; De Amicis, F.; Sirianni, R.; Sinicropi, M.S.; Puoci, F.; Casaburi, I.; Saturnino, C.; Pezzi, V. Progress to Improve Oral Bioavailability and Beneficial Effects of Resveratrol. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 1381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farhan, M.; Rizvi, A. The Pharmacological Properties of Red Grape Polyphenol Resveratrol: Clinical Trials and Obstacles in Drug Development. Nutrients 2023, 15, 4486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gligorijević, N.; Stanić-Vučinić, D.; Radomirović, M.; Stojadinović, M.; Khulal, U.; Nedić, O.; Ćirković Veličković, T. Role of Resveratrol in Prevention and Control of Cardiovascular Disorders and Cardiovascular Complications Related to COVID-19 Disease: Mode of Action and Approaches Explored to Increase Its Bioavailability. Molecules 2021, 26, 2834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nawaz, W.; Zhou, Z.; Deng, S.; Ma, X.; Ma, X.; Li, C.; Shu, X. Therapeutic Versatility of Resveratrol Derivatives. Nutrients 2017, 9, 1188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Zhang, J.; Yin, N.; Wele, P.; Li, F.; Dave, S.; Lin, J.; Xiao, H.; Wu, X. Resveratrol in disease prevention and health promotion: A role of the gut microbiome. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2024, 64, 5878–5895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gal, R.; Deres, L.; Toth, K.; Halmosi, R.; Habon, T. The Effect of Resveratrol on the Cardiovascular System from Molecular Mechanisms to Clinical Results. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 10152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, X.; Jia, Y.; Ren, F. Multidimensional biological activities of resveratrol and its prospects and challenges in the health field. Front. Nutr. 2024, 11, 1408651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, S.; Das, D.K. Anti-inflammatory responses of resveratrol. Inflamm. Allergy Drug Targets 2007, 6, 168–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olholm, J.; Paulsen, S.K.; Cullberg, K.B.; Richelsen, B.; Pedersen, S.B. Anti-inflammatory effect of resveratrol on adipokine expression and secretion in human adipose tissue explants. Int. J. Obes. 2010, 34, 1546–1553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- dos Santos, M.G.; da Luz, D.B.; de Miranda, F.B.; de Aguiar, R.F.; Siebel, A.M.; Arbo, B.D.; Hort, M.A. Resveratrol and Neuroinflammation: Total-Scale Analysis of the Scientific Literature. Nutraceuticals 2024, 4, 165–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dull, A.M.; Moga, M.A.; Dimienescu, O.G.; Sechel, G.; Burtea, V.; Anastasiu, C.V. Therapeutic Approaches of Resveratrol on Endometriosis via Anti-Inflammatory and Anti-Angiogenic Pathways. Molecules 2019, 24, 667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z.X.; Mou, S.F.; Chen, X.Q.; Gong, L.L.; Ge, W.S. Anti-inflammatory activity of resveratrol prevents inflammation by inhibiting NF-κB in animal models of acute pharyngitis. Mol. Med. Rep. 2018, 17, 1269–1274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wątroba, M.; Szukiewicz, D. Anti-Inflammatory Properties of Resveratrol. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 11710. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311710

Wątroba M, Szukiewicz D. Anti-Inflammatory Properties of Resveratrol. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2025; 26(23):11710. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311710

Chicago/Turabian StyleWątroba, Mateusz, and Dariusz Szukiewicz. 2025. "Anti-Inflammatory Properties of Resveratrol" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 26, no. 23: 11710. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311710

APA StyleWątroba, M., & Szukiewicz, D. (2025). Anti-Inflammatory Properties of Resveratrol. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 26(23), 11710. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311710