Distinct Spectral Profiles of Pleural Effusions from Malignant Tumors Using Raman Spectroscopy

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Patients’ Standard Cytology

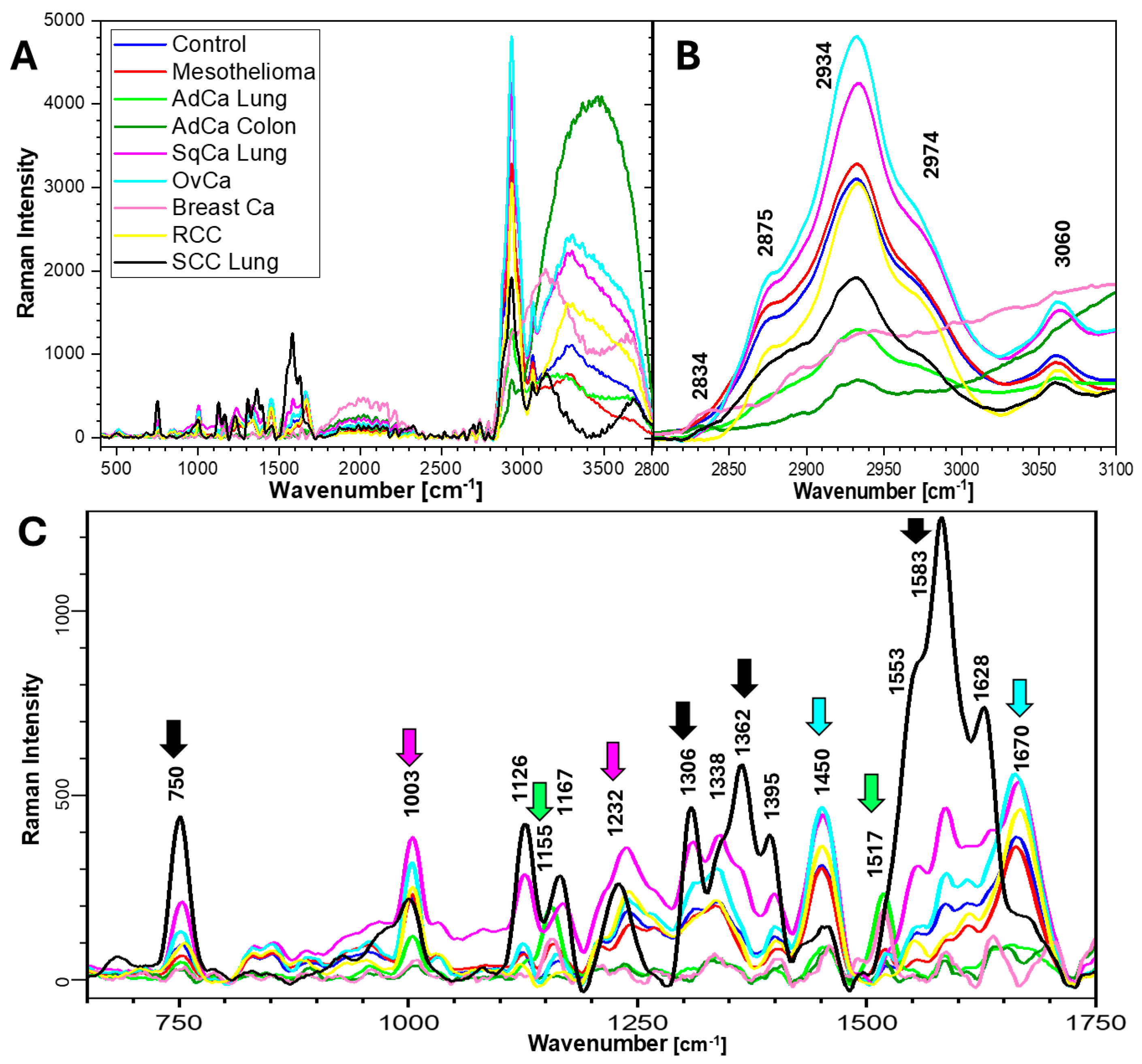

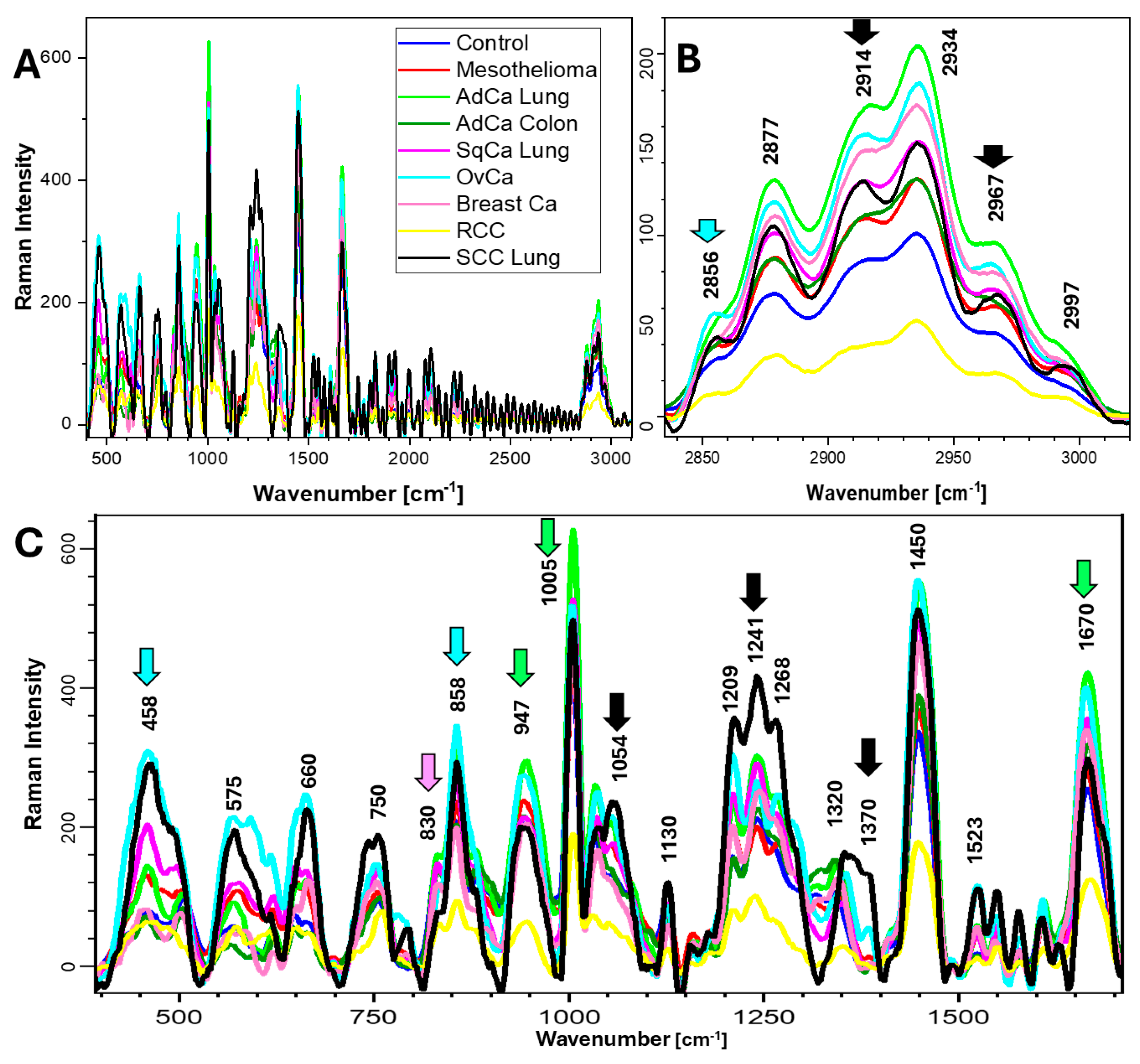

2.2. Raman Spectra and Biochemical Components of Samples

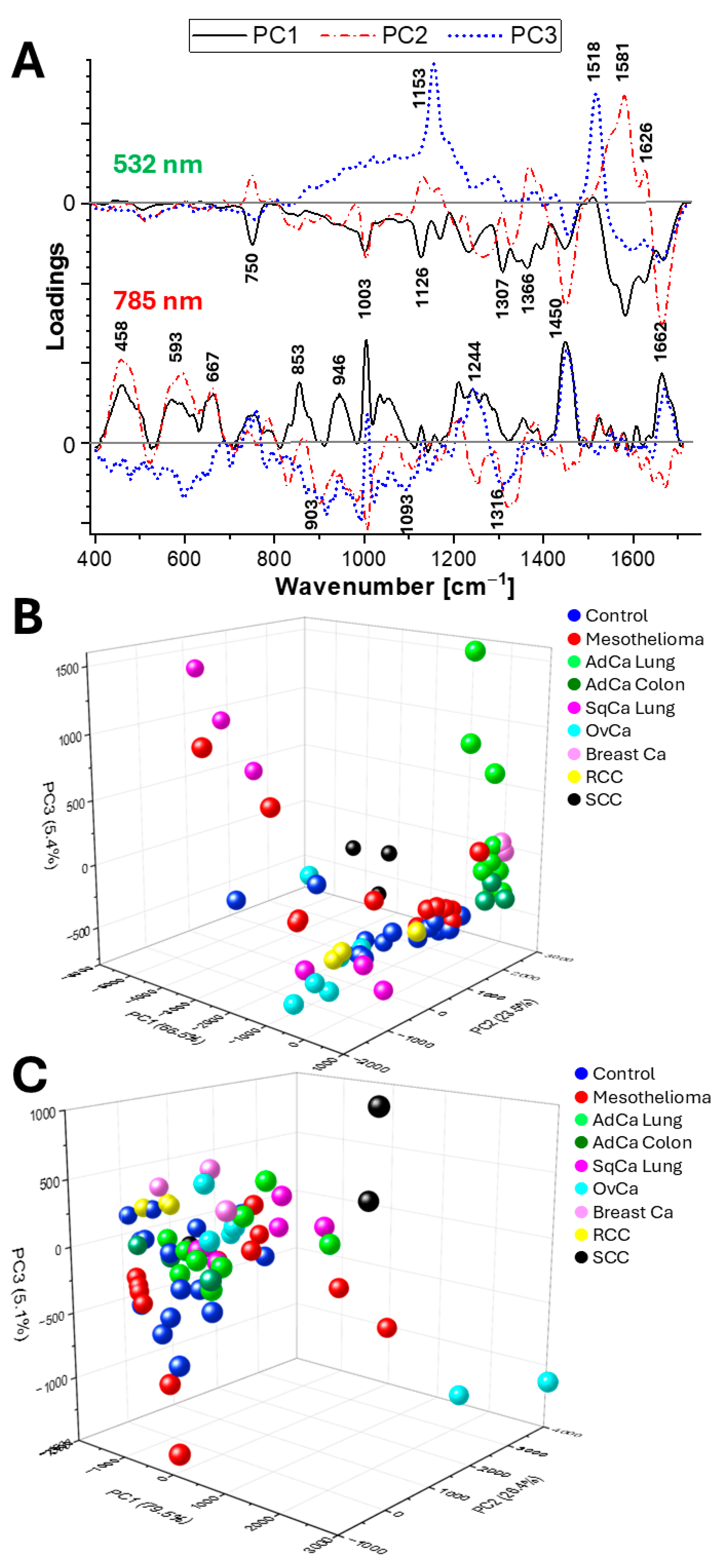

2.3. Principal Component Analysis (PCA)

3. Discussion

3.1. RS of Pleural Effusions

3.2. The Value of Pleural Samples

3.3. RS of Tumors Detected in Pleural Effusions

3.4. Study Limitations

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Experimental Samples

4.2. Raman Spectroscopy

4.3. Data Analysis and Visualization

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| RS | Raman Spectroscopy |

| Mes | Mesothelioma |

| AdCa | Adenocarcinoma (of the lung or colon) |

| SqCa | Squamous Carcinoma |

| OvCa | Ovarian Carcinoma (serous type) |

| SCC | Small-Cell Carcinoma |

| RCC | Renal Cell Carcinoma |

| PCA | Principal Component Analysis |

References

- Korczyński, P.; Górska, K.; Konopka, D.; Al-Haj, D.; Filipiak, K.J.; Krenke, R. Significance of congestive heart failure as a cause of pleural effusion: Pilot data from a large multidisciplinary teaching hospital. Cardiol. J. 2020, 27, 254–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sears, D.; Hajdu, S.I. The cytologic diagnosis of malignant neoplasms in pleural and peritoneal effusions. Acta Cytol. 1987, 31, 85–97. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Monte, S.A.; Ehya, H.; Lang, W.R. Positive effusion cytology as the initial presentation of malignancy. Acta Cytol. 1987, 31, 448–452. [Google Scholar]

- Bray, F.; Laversanne, M.; Sung, H.; Ferlay, J.; Siegel, R.L.; Soerjomataram, I.; Jemal, A. Global cancer statistics 2022: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2024, 74, 229–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bibby, A.C.; Tsim, S.; Kanellakis, N.; Ball, H.; Talbot, D.C.; Blyth, K.G.; Maskell, N.A.; Psallidas, I. Malignant pleural mesothelioma: An update on investigation, diagnosis and treatment. Eur. Respir. Rev. 2016, 25, 472–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amin, M.B.; Edge, S.; Greene, F.; Byrd, D.R.; Brookland, R.K.; Washington, M.K.; Gershenwald, J.E.; Compton, C.C.; Hess, K.R.; Sullivan, D.C.; et al. AJCC Cancer Staging Manual, 8th ed.; Springer International Publishing: New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, M.C.; Ghosh, M.; Chowdhury, J. Fabrication of gold nano-particles embedded in the Langmuir Blodgett film of Poly (methyl methacrylate) for rapid screening of melamine adulterant in milk powder. Opt. Mater. 2026, 169, 117549. [Google Scholar]

- Hardy, M.; Chu, H.O.M. Laser wavelength selection in Raman spectroscopy. Analyst 2025, 150, 1986–2008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giamougiannis, P.; Morais, C.L.; Grabowska, R.; Ashton, K.M.; Wood, N.J.; Martin-Hirsch, P.L.; Martin, F.L. A comparative analysis of different biofluids towards ovarian cancer diagnosis using Raman microspectroscopy. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2021, 413, 911–922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kujdowicz, M.; Placha, W.; Mech, B.; Chrabaszcz, K.; Okoń, K.; Malek, K. In Vitro Spectroscopy-Based Profiling of Urothelial Carcinoma: A Fourier Transform Infrared and Raman Imaging Study. Cancers 2021, 13, 123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, Y.; Liu, Y.; Luo, J. Recent application of Raman spectroscopy in tumor diagnosis: From conventional methods to artificial intelligence fusion. PhotoniX 2023, 4, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hauptmann, A.; Hoelzl, G.; Mueller, M.; Bechtold-Peters, K.; Loerting, T. Raman Marker Bands for Secondary Structure Changes of Frozen Therapeutic Monoclonal Antibody Formulations During Thawing. J. Pharm. Sci. 2023, 112, 51–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sjöberg, B.; Foley, S.; Cardey, B.; Enescu, M. An experimental and theoretical study of the amino acid side chain Raman bands in proteins. Spectrochim. Acta-Part A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2014, 128, 300–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández, B.; Coïc, Y.M.; Kruglik, S.G.; Sanchez-Cortes, S.; Ghomi, M. The relationship between the tyrosine residue 850–830 cm−1 Raman doublet intensity ratio and the aromatic side chain χ1 torsion angle. Spectrochim. Acta Part A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2024, 308, 123681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pezzotti, G. Raman spectroscopy in cell biology and microbiology. J. Raman Spectrosc. 2021, 52, 2348–2443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishimaru, Y.; Oshima, Y.; Imai, Y.; Iimura, T.; Takanezawa, S.; Hino, K.; Miura, H. Raman Spectroscopic Analysis to Detect Reduced Bone Quality after Sciatic Neurectomy in Mice. Molecules 2018, 25, 3081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brauchle, E.; Schenke-Layland, K. Raman spectroscopy in biomedicine—Non-invasive in vitro analysis of cells and extracellular matrix components in tissues. Biotechnol. J. 2018, 8, 288–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kujdowicz, M.; Perez-Guaita, D.; Chlosta, P.; Okon, K.; Malek, K. Evaluation of grade and invasiveness of bladder urothelial carcinoma using infrared imaging and machine learning. Analyst 2023, 148, 278–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kowalska, A.A.; Czaplicka, M.; Nowicka, A.B.; Chmielewska, I.; Kędra, K.; Szymborski, T.; Kamińska, A. Lung Cancer: Spectral and Numerical Differentiation among Benign and Malignant Pleural Effusions Based on the Surface-Enhanced Raman Spectroscopy. Biomedicines 2022, 10, 993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, K.; Jin, S.; Song, Z.; Jiang, L. High accuracy detection of malignant pleural effusion based on label-free surface-enhanced Raman spectroscopy and multivariate statistical analysis. Spectrochim. Acta-Part A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2020, 226, 117632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shamseddin, M.; Obacz, J.; Garnett, M.J.; Rintoul, R.C.; Francies, H.E.; Marciniak, S.J. Use of preclinical models for malignant pleural mesothelioma. Thorax 2021, 76, 1154–1162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zipprick, J.; Demir, E.; Krynska, H.; Köprülüoğlu, S.; Strauß, K.; Skribek, M.; Hutyra-gram Ötvös, R.; Gad, A.K.; Dobra, K. Ex-Vivo Drug-Sensitivity Testing to Predict Clinical Response in Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer and Pleural Mesothelioma: A Systematic Review and Narrative Synthesis. Cancers 2025, 17, 986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shatar, L.; Pillai, N.; Chee, H.Y.; Mustafa, F.H.; Nasir, M.N.; Zakaria, R.; Mustafa, M.K.; Zain, M.N.; Suhailin, F.H. Enhancement in surface-enhanced Raman spectroscopy (SERS) substrates and the potential for diseases detection. Appl. Spectrosc. Rev. 2025, 1–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pimenta, S.; Correia, J.H. Biomedical Applications of Raman Spectroscopy: A Review. Photochem 2025, 5, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cialla-May, D.; Bonifacio, A.; Markin, A.; Markina, N.; Fornasaro, S.; Dwivedi, A.; Dib, T.; Farnesi, E.; Liu, C.; Ghosh, A.; et al. Recent advances of surface enhanced Raman spectroscopy (SERS) in optical biosensing. TrAC Trends Anal. Chem. 2024, 181, 117990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, D.; Huang, Z.; Chen, J.; Lu, Y. pH-Adjusted Liquid SERS Approach: Toward a Reliable Plasma-Based Early Stage Lung Cancer Detection. Anal. Chem. 2025, 97, 508–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, N.; Rao, S.; Noothalapati, H.; Mazumder, N.; Paul, B. Raman spectroscopy in the detection and diagnosis of lung cancer: A meta-analysis. Lasers Med. Sci. 2025, 40, 164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, C.; Hao, J.; Hao, X.; Xu, W.; Xiao, C.; Zhang, J.; Pu, Q.; Liu, L. The accuracy of Raman spectroscopy in the diagnosis of lung cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Transl. Cancer Res. 2021, 10, 3680–3693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kowalska, A.A.; Czaplicka, M.; Chmielewska, I.; Pankowski, J.; Kaminska, A. The Lung Cancer Detection and Type Determination From Plasma and Lung Tissues by Surface-Enhanced Raman Spectroscopy. J. Raman Spectrosc. 2025, 56, 689–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanna, K.; Krzoska, E.; Shaaban, A.M.; Muirhead, D.; Abu-Eid, R.; Speirs, V. Raman spectroscopy: Current applications in breast cancer diagnosis, challenges and future prospects. Br. J. Cancer 2022, 126, 1125–1139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharjee, T.; Tawde, S.; Hudlikar, R.; Mahimkar, M.; Maru, G.; Ingle, A.; Murali Krishna, C. Ex vivo Raman spectroscopic study of breast metastatic lesions in lungs in animal models. J. Biomed. Opt. 2015, 20, 85006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melitto, A.S.; Arias, V.E.A.; Shida, J.Y.; Gebrim, L.H.; Silveira, L. Diagnosing molecular subtypes of breast cancer by means of Raman spectroscopy. Lasers Surg. Med. 2022, 54, 1143–1156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frimpong, D.; Shore, A.C.; Gardner, B.; Newton, C.; Pawade, J.; Frost, J.; Atherton, L.; Stone, N. Raman spectroscopy of ovarian and peritoneal tissue in the assessment of ovarian cancer. Analyst 2025, 150, 1303–1309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kluz-Barłowska, M.; Kluz, T.; Paja, W.; Pancerz, K.; Łączyńska-Madera, M.; Miziak, P.; Cebulski, J.; Depciuch, J. FT-Raman and FTIR spectroscopy as a tools showing marker of platinum-resistant phenomena in women suffering from ovarian cancer. Sci. Rep. 2014, 14, 11025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fousková, M.; Vališ, J.; Synytsya, A.; Habartová, L.; Petrtýl, J.; Petruželka, L.; Setnička, V. In vivo Raman spectroscopy in the diagnostics of colon cancer. Analyst 2023, 148, 2518–2526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, C.; Wu, X.; Zhou, J.; Chen, Y.; Ye, J. Raman optical identification of renal cell carcinoma via machine learning. Spectrochim. Acta-Part A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2021, 252, 119520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Chen, F.; Yang, B.; Zhang, K.; Lv, X.; Chen, C. A novel diagnostic method: FT-IR, Raman and derivative spectroscopy fusion technology for the rapid diagnosis of renal cell carcinoma serum. Spectrochim. Acta Part A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2022, 269, 120684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Musa, M.; Croce, A.; Allegrina, M.; Rinaudo, C.; Belluso, E.; Bellis, D.; Toffalorio, F.; Veronesi, G. The use of Raman spectroscopy to identify inorganic phases in iatrogenic pathological lesions of patients with malignant pleural mesothelioma. Vib. Spectrosc. 2012, 61, 66–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bard, D.; Yarwood, J.; Tylee, B. Asbestos fibre identification by Raman microspectroscopy. J. Raman Spectrosc. 1997, 28, 803–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbas, S.; Simsek Ozek, N.; Emri, S.; Koksal, D.; Severcan, M.; Severcan, F. Diagnosis of malignant pleural mesothelioma from pleural fluid by Fourier transform-infrared spectroscopy coupled with chemometrics. J. Biomed. Opt. 2018, 23, 105003, Erratum in J. Biomed. Opt. 2018, 23, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Chan, S.C.; Pang, W.S.; Chow, S.H.; Lok, V.; Zhang, L.; Lin, X.; Lucero-Prisno, D.E.; Xu, W.; Zheng, Z.J.; et al. Global Incidence, Risk Factors, and Temporal Trends of Mesothelioma: A Population-Based Study. J. Thorac. Oncol. 2023, 18, 792–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wasifuddin, M.; Ilerhunmwuwa, N.; Hakobyan, N.; Sedeta, E.; Uche, I.; Aiwuyo, H.O.; Perry, J.C.; Heravi, O.; Boris, A. Malignant Pleural Effusion As the Initial Presentation of Renal Cell Carcinoma: A Case Report and Literature Review. Cureus 2023, 15, e37128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xia, H.; Wang, X.J.; Zhou, Q.; Shi, H.Z.; Tong, Z.H. Efficacy and safety of talc pleurodesis for malignant pleural effusion: A meta-analysis. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e87060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Nr | Sex | Age [Years] | Side | Experimental Group | Color | MTC | SqC | Lym | Neu | MPh | NC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | M | 72 | R | RCC | W | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| 2 | K | 57 | R | Mes | W | 2 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| 3 | K | 75 | L | SqCa Lung | W | 0 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 |

| 4 | M | 84 | L | Control | W | 0 | 0 | 1 | 3 | 2 | 0 |

| 5 | K | 61 | R | Control | W | 3 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 3 | 0 |

| 6 | M | 70 | L | SqCa Lung | LB | 1 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 |

| 7 | M | 73 | L | Control | W | 3 | 0 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| 8 | K | 74 | R | Control | W | 2 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| 9 | M | 67 | L | Control | W | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 3 | 0 |

| 10 | M | 71 | L | Mes | W | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| 11 | K | 70 | R | OvCa | LB | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| 12 | M | 88 | R | SCC Lung | B | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 2 |

| 13 | K | 67 | R | Mes | W | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 |

| 14 | K | 64 | R | OvCa | W | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| 15 | M | 61 | R | Mes | Y | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 |

| 16 | M | 70 | R | AdCa Lung | LB | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| 17 | K | 75 | L | AdCa Lung | Y | 1 | 0 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 3 |

| 18 | M | 65 | L | AdCa Lung | W | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| 19 | M | 80 | R | AdCa Colon | W | 2 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 |

| 20 | K | 75 | R | Breast Ca | W | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Effusion Cause | Biochemical Components and Bands Assigned to Them [cm−1] | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Proteins | Nucleic Acids | Lipids | Carbohydrates | Trp | Phe | Tyr | |

| 1232, 1362, 1395, 1450, 1583, 1670 | 458, 593, 750, 1362, 1553 | 667, 1450, 2875, 2934, 2974 | 667, 1338 | 750, 1126, 1316, 1362 | 1003, 1155 | 593, 830, 858, 946, 1155, 1517, 1628 | |

| Control | ++ | + | + | + | −/+ | + | −/+ |

| Mes | + | + | +++ | + | −/+ | + | + |

| AdCa Lung | + | + | −/+ | − | −/+ | ++ | +++ |

| AdCa Colon | −/+ | + | −/+ | + | −/+ | ++ | + |

| SqCa Lung | +++ | ++ | ++ | +++ | ++ | +++ | ++ |

| OvCa | ++ | + | +++ | + | + | ++ | − |

| Breast Ca | + | + | −/+ | − | −/+ | −/+ | + |

| RCC | ++ | + | ++ | + | −/+ | ++ | − |

| SCC Lung | +++ | +++ | −/+ | ++ | +++ | + | ++ |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kujdowicz, M.; Jeleń, P.; Sitarz, M.; Marcinek, M.; Włodarczyk, J.; Wiłkojć, M.; Rudnicka, L.; Adamek, D. Distinct Spectral Profiles of Pleural Effusions from Malignant Tumors Using Raman Spectroscopy. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 11707. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311707

Kujdowicz M, Jeleń P, Sitarz M, Marcinek M, Włodarczyk J, Wiłkojć M, Rudnicka L, Adamek D. Distinct Spectral Profiles of Pleural Effusions from Malignant Tumors Using Raman Spectroscopy. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2025; 26(23):11707. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311707

Chicago/Turabian StyleKujdowicz, Monika, Piotr Jeleń, Maciej Sitarz, Marta Marcinek, Janusz Włodarczyk, Michał Wiłkojć, Lucyna Rudnicka, and Dariusz Adamek. 2025. "Distinct Spectral Profiles of Pleural Effusions from Malignant Tumors Using Raman Spectroscopy" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 26, no. 23: 11707. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311707

APA StyleKujdowicz, M., Jeleń, P., Sitarz, M., Marcinek, M., Włodarczyk, J., Wiłkojć, M., Rudnicka, L., & Adamek, D. (2025). Distinct Spectral Profiles of Pleural Effusions from Malignant Tumors Using Raman Spectroscopy. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 26(23), 11707. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311707