Integrative Neuroimmune Role of the Parasympathetic Nervous System, Vagus Nerve and Gut Microbiota in Stress Modulation: A Narrative Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

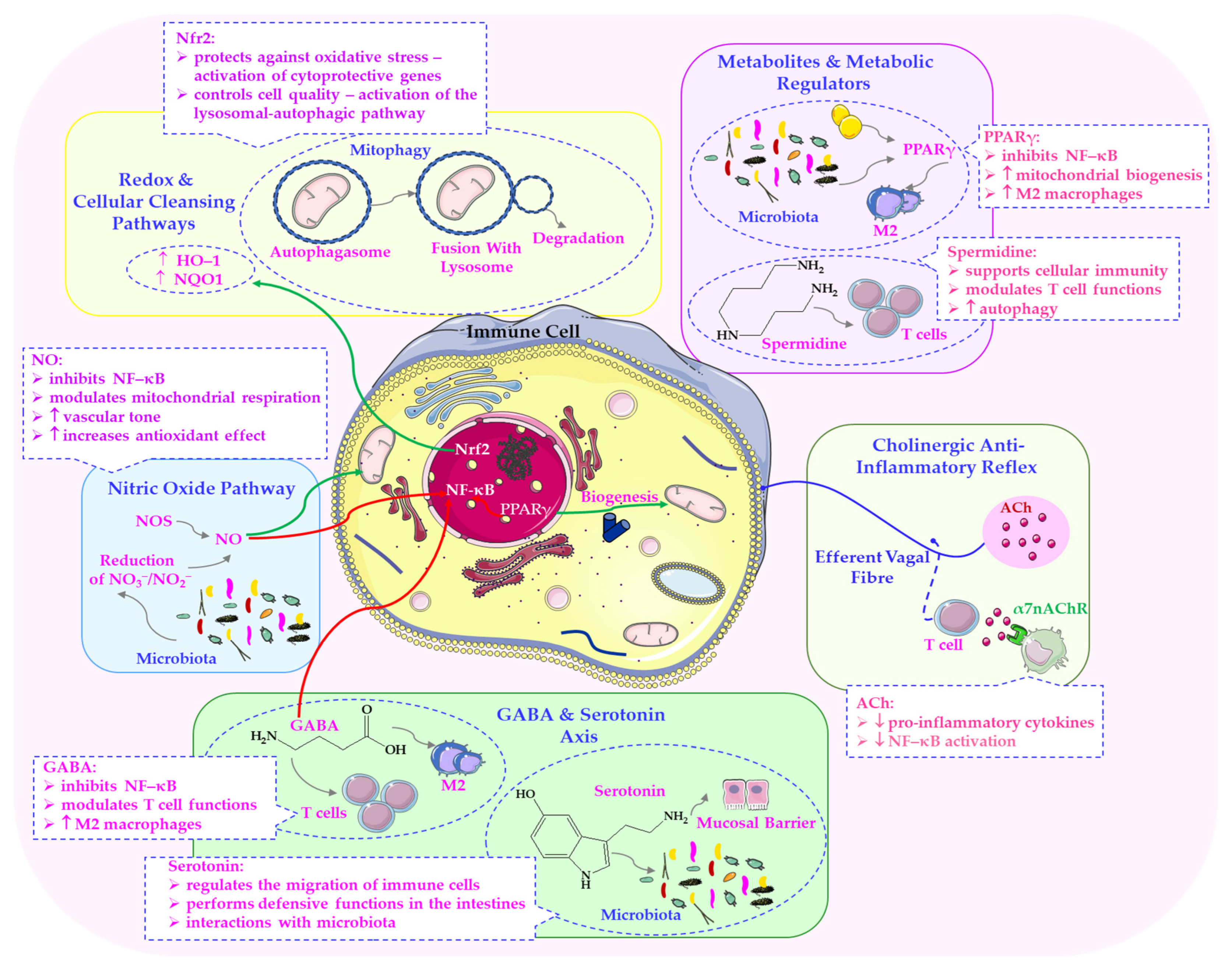

2. Physiological and Molecular Basis of Parasympathetic Activity

2.1. Parasympathetic Regulation of Systemic Homeostasis: Inflammation, Metabolism, and Adaptation

2.2. The Vagus Nerve: A Central Hub Linking Neural, Immune, and Microbial Networks

2.3. Non-Neuronal Acetylcholine and Cell Function

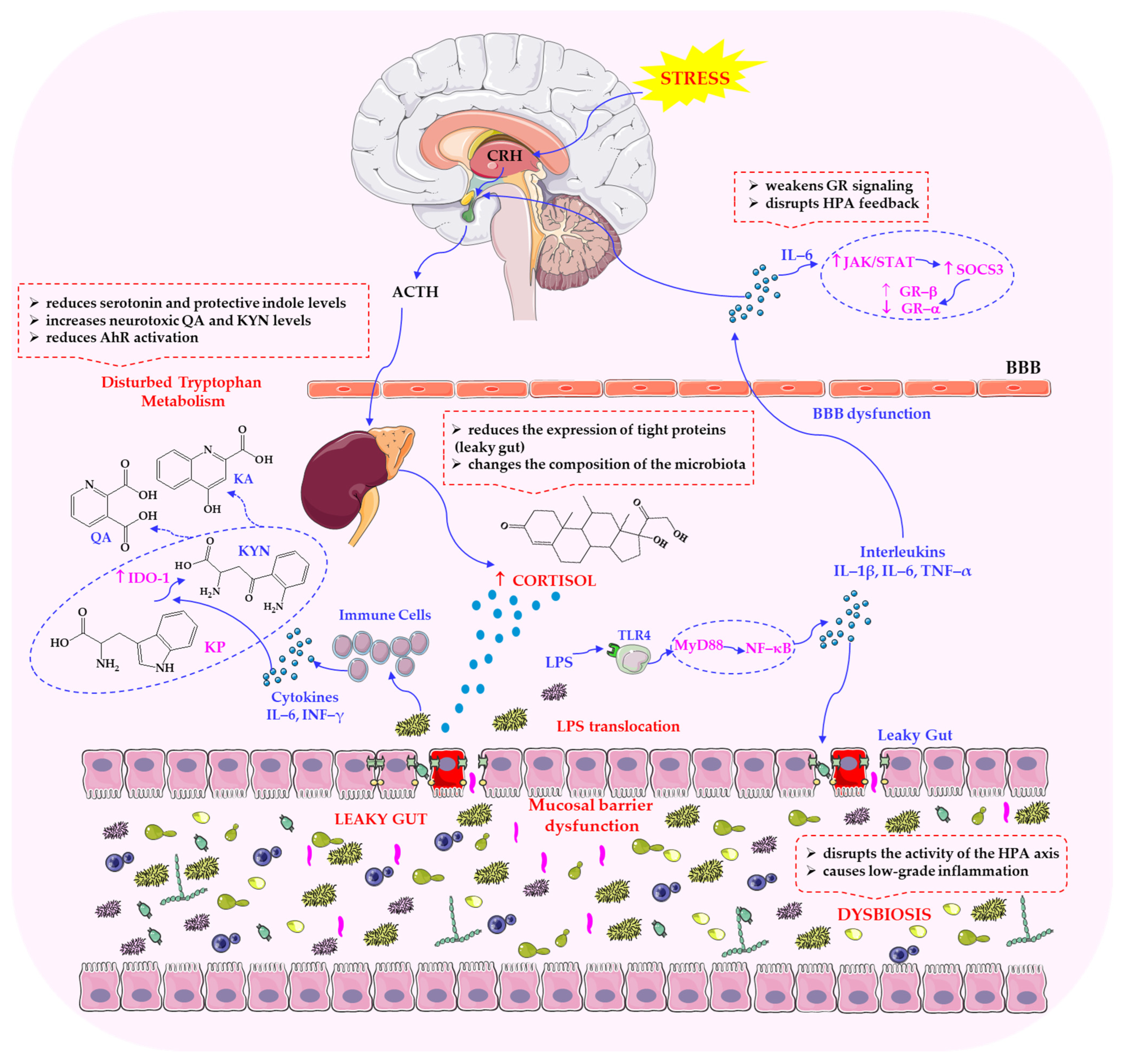

3. Mechanisms Linking Parasympathetic Function to Stress Regulation

3.1. Vagal Anti-Inflammatory Pathways and Modulation of the HPA Axis

3.2. Parasympathetic Influence on Metabolic Flexibility and Stress Adaptation

4. Strategic Modulation of Parasympathetic Activity

4.1. Lifestyle-Based Interventions: Intermittent Hypoxia, Exercise and Diet

4.2. Novel Approaches to Enhancing Vagal Tone and Physiological Resilience

4.3. Integration with Microbiota-Targeted Strategies

5. The Gut Microbiome as a Therapeutic Target in Stress

5.1. Microbiome-Mediated Regulation of Stress Responses

5.2. The Microbiome–Vagus Nerve Axis and Its Neuroimmune and Metabolic Pathways

5.3. Microbial Mediators of Neuroendocrine and Immune Crosstalk

5.4. Parasympathetic Modulation of GABAergic and Serotonergic Signalling in the Gut–Brain Axis

6. Pathophysiology and Disease Implications

6.1. Consequences of Parasympathetic Dysfunction and Microbial Imbalance

6.2. Vagal–Microbiota Interactions in Neuropsychiatric, Metabolic and Inflammatory Disorders

6.3. Cellular Mechanisms: Lysosomal Function, Autophagy and Microbial Homeostasis

7. Clinical Implications and Therapeutic Opportunities

7.1. Emerging Therapies: Neuromodulation, Probiotics, Prebiotics, and Lifestyle Optimisation

7.2. Personalised Approaches: Integrating Physiology, the Microbiome and Patient-Specific Stress Profiles

8. Conclusions and Future Perspectives

9. Limitations

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional: Review Board Statement

Informed: Consent Statement

Data: Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Knezevic, E.; Nenic, K.; Milanovic, V.; Knezevic, N.N. The Role of Cortisol in Chronic Stress, Neurodegenerative Diseases, and Psychological Disorders. Cells 2023, 12, 2726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheperjans, F.; Aho, V.; Pereira, P.A.; Koskinen, K.; Paulin, L.; Pekkonen, E.; Haapaniemi, E.; Kaakkola, S.; Eerola-Rautio, J.; Pohja, M.; et al. Gut Microbiota Are Related to Parkinson’s Disease and Clinical Phenotype. Mov. Disord. 2015, 30, 350–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gershon, M.D.; Margolis, K.G. The Gut, Its Microbiome, and the Brain: Connections and Communications. J. Clin. Investig. 2021, 131, e143768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, X.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, X.; Li, S.; Mei, H.; Xiao, H.; Ma, X.; Liu, Z.; Li, R. Gut Microbiome and Serum Amino Acid Metabolome Alterations in Autism Spectrum Disorder. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 4037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Claudino Dos Santos, J.C.; Oliveira, L.F.; Noleto, F.M.; Gusmão, C.T.P.; Brito, G.A.C.; Viana, G.S.B. Gut-Microbiome-Brain Axis: The Crosstalk between the Vagus Nerve, Alpha-Synuclein and the Brain in Parkinson’s Disease. Neural Regen. Res. 2023, 18, 2611–2614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauer, K.C.; Trehan, R.; Ruf, B.; Myojin, Y.; Benmebarek, M.R.; Ma, C.; Seifert, M.; Nur, A.; Qi, J.; Huang, P.; et al. The Gut Microbiome Controls Liver Tumors via the Vagus Nerve. bioRxiv 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wessler, I.; Kirkpatrick, C.J. Acetylcholine beyond Neurons: The Non-Neuronal Cholinergic System in Humans. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2008, 154, 1558–1571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalile, B.; Van Oudenhove, L.; Vervliet, B.; Verbeke, K. The Role of Short-Chain Fatty Acids in Microbiota-Gut-Brain Communication. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2019, 16, 461–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van de Wouw, M.; Boehme, M.; Lyte, J.M.; Wiley, N.; Strain, C.; O’Sullivan, O.; Clarke, G.; Stanton, C.; Dinan, T.G.; Cryan, J.F. Short-Chain Fatty Acids: Microbial Metabolites That Alleviate Stress-Induced Brain-Gut Axis Alterations. J. Physiol. 2018, 596, 4923–4944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Y.; Wang, B.; Gao, H.; He, C.; Hua, R.; Liang, C.; Zhang, S.; Wang, Y.; Xin, S.; Xu, J. Vagus Nerve and Underlying Impact on the Gut Microbiota-Brain Axis in Behavior and Neurodegenerative Diseases. J. Inflamm. Res. 2022, 15, 6213–6230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, C.; Yan, Q.; Ma, Y.; Fang, J.; Yang, Y. Recognizing the Role of the Vagus Nerve in Depression from Microbiota-Gut-Brain Axis. Front. Neurol. 2022, 13, 1015175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ullah, H.; Arbab, S.; Tian, Y.; Liu, C.Q.; Chen, Y.; Qijie, L.; Khan, M.I.U.; Hassan, I.U.; Li, K. The Gut Microbiota-Brain Axis in Neurological Disorder. Front. Neurosci. 2023, 17, 1225875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rutsch, A.; Kantsjö, J.B.; Ronchi, F. The Gut-Brain Axis: How Microbiota and Host Inflammasome Influence Brain Physiology and Pathology. Front. Immunol. 2020, 11, 604179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, Y.P.; Bernardi, A.; Frozza, R.L. The Role of Short-Chain Fatty Acids from Gut Microbiota in Gut-Brain Communication. Front. Endocrinol. 2020, 11, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herman, J.P.; McKlveen, J.M.; Ghosal, S.; Kopp, B.; Wulsin, A.; Makinson, R.; Scheimann, J.; Myers, B. Regulation of the Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Adrenocortical Stress Response. Compr. Physiol. 2016, 6, 603–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kinlein, S.A.; Karatsoreos, I.N. The Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Adrenal Axis as a Substrate for Stress Resilience: Interactions with the Circadian Clock. Front. Neuroendocrinol. 2020, 56, 100819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonaz, B.; Sinniger, V.; Pellissier, S. The Vagus Nerve in the Neuro-Immune Axis: Implications in the Pathology of the Gastrointestinal Tract. Front. Immunol. 2017, 8, 1452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bonaz, B.; Bazin, T.; Pellissier, S. The Vagus Nerve at the Interface of the Microbiota-Gut-Brain Axis. Front. Neurosci. 2018, 12, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.E.; Lee, J.S. Advances in the Regulation of Inflammatory Mediators in Nitric Oxide Synthase: Implications for Disease Modulation and Therapeutic Approaches. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 1204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hong, P.P.; Zhu, X.X.; Yuan, W.J.; Niu, G.J.; Wang, J.X. Nitric Oxide Synthase Regulates Gut Microbiota Homeostasis by ERK-NF-κB Pathway in Shrimp. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 778098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Chen, Y.; Xie, H.; Feng, Y.; Chen, S.; Bao, B. Effects of Inducible Nitric Oxide Synthase (iNOS) Gene Knockout on the Diversity, Composition, and Function of Gut Microbiota in Adult Zebrafish. Biology 2024, 13, 372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Y.; Wu, W. Multimodal Non-Invasive Non-Pharmacological Therapies for Chronic Pain: Mechanisms and Progress. BMC Med. 2023, 21, 372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weaver, A.K.; Head, J.R.; Gould, C.F.; Carlton, E.J.; Remais, J.V. Environmental Factors Influencing COVID-19 Incidence and Severity. Annu. Rev. Public Health 2022, 43, 271–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ford, J.D.; Zavaleta-Cortijo, C.; Ainembabazi, T.; Anza-Ramirez, C.; Arotoma-Rojas, I.; Bezerra, J.; Chicmana-Zapata, V.; Galappaththi, E.K.; Hangula, M.; Kazaana, C.; et al. Interactions between Climate and COVID-19. Lancet Planet. Health 2022, 6, e825–e833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tindle, J.; Tadi, P. Neuroanatomy, Parasympathetic Nervous System. In StatPearls; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2025; [Updated 31 October 2022]. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK553141/ (accessed on 30 May 2025).

- Waxenbaum, J.A.; Reddy, V.; Varacallo, M.A. Anatomy, Autonomic Nervous System. In StatPearls; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2025; [Updated 24 July 2023]. [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez-Manso, J.C.; Gujarathi, R.; Varacallo, M.A. Autonomic Dysfunction. In StatPearls; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2025; [Updated 4 August 2023]. [Google Scholar]

- Carlson, A.B.; Kraus, G.P. Physiology, Cholinergic Receptors. In StatPearls; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2025; [Updated 14 August 2023]. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK526134/ (accessed on 30 May 2025).

- Tanahashi, Y.; Komori, S.; Matsuyama, H.; Kitazawa, T.; Unno, T. Functions of Muscarinic Receptor Subtypes in Gastrointestinal Smooth Muscle: A Review of Studies with Receptor-Knockout Mice. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sam, C.; Bordoni, B. Physiology, Acetylcholine. In StatPearls; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2025; [Updated 10 April 2023]. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK557825/ (accessed on 30 May 2025).

- Tizabi, Y.; Getachew, B.; Tsytsarev, V.; Csoka, A.B.; Copeland, R.L.; Heinbockel, T. Central Nicotinic and Muscarinic Receptors in Health and Disease. In Acetylcholine—Recent Advances and New Perspectives; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsimpili, H.; Zoidis, G. A New Era of Muscarinic Acetylcholine Receptor Modulators in Neurological Diseases, Cancer and Drug Abuse. Pharmaceuticals 2025, 18, 369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baccari, M.C.; Calamai, F.; Staderini, G. Modulation of Cholinergic Transmission by Nitric Oxide, VIP and ATP in the Gastric Muscle. Neuroreport 1994, 5, 905–908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murr, M.M.; Balsiger, B.M.; Farrugia, G.; Sarr, M.G. Role of Nitric Oxide, Vasoactive Intestinal Polypeptide, and ATP in Inhibitory Neurotransmission in Human Jejunum. J. Surg. Res. 1999, 84, 8–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holzer, P.; Farzi, A. Neuropeptides and the Microbiota-Gut-Brain Axis. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2014, 817, 195–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kay, M.W.; Jain, V.; Panjrath, G.; Mendelowitz, D. Targeting Parasympathetic Activity to Improve Autonomic Tone and Clinical Outcomes. Physiology 2022, 37, 39–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavlov, V.A.; Tracey, K.J. The Cholinergic Anti-Inflammatory Pathway. Brain Behav. Immun. 2005, 19, 493–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tracey, K.J. The Inflammatory Reflex. Nature 2002, 420, 853–859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czura, C.J.; Friedman, S.G.; Tracey, K.J. Neural Inhibition of Inflammation: The Cholinergic Anti-Inflammatory Pathway. J. Endotoxin Res. 2003, 9, 409–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Breit, S.; Kupferberg, A.; Rogler, G.; Hasler, G. Vagus Nerve as Modulator of the Brain-Gut Axis in Psychiatric and Inflammatory Disorders. Front. Psychiatry 2018, 9, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, J.; Li, S.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, J.; Xin, C.; Wang, Y.; Rong, P. Anti-Neuroinflammation Effects of Transcutaneous Auricular Vagus Nerve Stimulation Against Depression-Like Behaviors via Hypothalamic α7nAchR/JAK2/STAT3/NF-κB Pathway in Rats Exposed to Chronic Unpredictable Mild Stress. CNS Neurosci. Ther. 2023, 29, 2634–2644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parrish, W.R.; Rosas-Ballina, M.; Gallowitsch-Puerta, M.; Ochani, M.; Ochani, K.; Yang, L.H.; Hudson, L.; Lin, X.; Patel, N.; Johnson, S.M.; et al. Modulation of TNF Release by Choline Requires Alpha7 Subunit Nicotinic Acetylcholine Receptor-Mediated Signaling. Mol. Med. 2008, 14, 567–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pechlivanidou, M.; Ninou, E.; Karagiorgou, K.; Tsantila, A.; Mantegazza, R.; Francesca, A.; Furlan, R.; Dudeck, L.; Steiner, J.; Tzartos, J.; et al. Autoimmunity to Neuronal Nicotinic Acetylcholine Receptors. Pharmacol. Res. 2023, 192, 106790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mashimo, M.; Moriwaki, Y.; Misawa, H.; Kawashima, K.; Fujii, T. Regulation of Immune Functions by Non-Neuronal Acetylcholine (ACh) via Muscarinic and Nicotinic ACh Receptors. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 6818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawashima, K.; Fujii, T.; Moriwaki, Y.; Misawa, H.; Horiguchi, K. Non-Neuronal Cholinergic System in Regulation of Immune Function with a Focus on α7 nAChRs. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2015, 29, 127–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reale, M.; Costantini, E. Cholinergic Modulation of the Immune System in Neuroinflammatory Diseases. Diseases 2021, 9, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, L.; Wang, H.-B.; Hashimoto, K. The Vagus Nerve: An Old but New Player in Brain-Body Communication. Brain Behav. Immun. 2025, 124, 28–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Che Mohd Nassir, C.M.N.; Che Ramli, M.D.; Mohamad Ghazali, M.; Jaffer, U.; Abdul Hamid, H.; Mehat, M.Z.; Hein, Z.M. The Microbiota-Gut-Brain Axis: Key Mechanisms Driving Glymphopathy and Cerebral Small Vessel Disease. Life 2024, 15, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kurhaluk, N. Tricarboxylic Acid Cycle Intermediates and Individual Ageing. Biomolecules 2024, 14, 260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zanesco, A.; Antunes, E. Effects of Exercise Training on the Cardiovascular System: Pharmacological Approaches. Pharmacol. Ther. 2007, 114, 307–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadad, R.; Akobe, S.F.; Weber, P.; Madsen, C.V.; Larsen, B.S.; Madsbad, S.; Nielsen, O.W.; Dominguez, M.H.; Haugaard, S.B.; Sajadieh, A. Parasympathetic Tonus in Type 2 Diabetes and Pre-Diabetes and Its Clinical Implications. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 18020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiwari, R.; Kumar, R.; Malik, S.; Raj, T.; Kumar, P. Analysis of Heart Rate Variability and Implication of Different Factors on Heart Rate Variability. Curr. Cardiol. Rev. 2021, 17, e160721189770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laborde, S.; Mosley, E.; Thayer, J.F. Heart Rate Variability and Cardiac Vagal Tone in Psychophysiological Research—Recommendations for Experiment Planning, Data Analysis, and Data Reporting. Front. Psychol. 2017, 8, 213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, A.A.; Lip, G.Y.H.; Shantsila, A. Heart Rate Variability in Atrial Fibrillation: The Balance between Sympathetic and Parasympathetic Nervous System. Eur. J. Clin. Investig. 2019, 49, e13174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sic, A.; Bogicevic, M.; Brezic, N.; Nemr, C.; Knezevic, N.N. Chronic Stress and Headaches: The Role of the HPA Axis and Autonomic Nervous System. Biomedicines 2025, 13, 463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, H.; Silberstein, S.D. Vagus Nerve and Vagus Nerve Stimulation, a Comprehensive Review: Part II. Headache 2016, 56, 259–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prescott, S.L.; Liberles, S.D. Internal Senses of the Vagus Nerve. Neuron 2022, 110, 579–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andalib, S.; Divani, A.A.; Ayata, C.; Baig, S.; Arsava, E.M.; Topcuoglu, M.A.; Cáceres, E.L.; Parikh, V.; Desai, M.J.; Majid, A.; et al. Vagus Nerve Stimulation in Ischemic Stroke. Curr. Neurol. Neurosci. Rep. 2023, 23, 947–962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, Y.K.; Oh, J.S. Interaction of the Vagus Nerve and Serotonin in the Gut-Brain Axis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 1160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCorry, L.K. Physiology of the Autonomic Nervous System. Am. J. Pharm. Educ. 2007, 71, 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gallowitsch-Puerta, M.; Pavlov, V.A. Neuro-Immune Interactions via the Cholinergic Anti-Inflammatory Pathway. Life Sci. 2007, 80, 2325–2329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giri, P.; Hu, F.; La Gamma, E.F.; Nankova, B.B. Absence of Gut Microbial Colonization Attenuates the Sympathoadrenal Response to Hypoglycemic Stress in Mice: Implications for Human Neonates. Pediatr. Res. 2019, 85, 574–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LaGamma, E.F.; Hu, F.; Pena Cruz, F.; Bouchev, P.; Nankova, B.B. Bacteria-Derived Short Chain Fatty Acids Restore Sympathoadrenal Responsiveness to Hypoglycemia after Antibiotic-Induced Gut Microbiota Depletion. Neurobiol. Stress 2021, 15, 100376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Margolis, K.G.; Cryan, J.F.; Mayer, E.A. The Microbiota-Gut-Brain Axis: From Motility to Mood. Gastroenterology 2021, 160, 1486–1501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wessler, I.K.; Kirkpatrick, C.J. Activation of Muscarinic Receptors by Non-Neuronal Acetylcholine. Handb. Exp. Pharmacol. 2012, 208, 469–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wessler, I.K.; Kirkpatrick, C.J. Non-Neuronal Acetylcholine Involved in Reproduction in Mammals and Honeybees. J. Neurochem. 2017, 142 (Suppl. S2), 144–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawashima, K.; Fujii, T. Expression of Non-Neuronal Acetylcholine in Lymphocytes and Its Contribution to the Regulation of Immune Function. Front. Biosci. 2004, 9, 2063–2085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujii, T.; Mashimo, M.; Moriwaki, Y.; Misawa, H.; Ono, S.; Horiguchi, K.; Kawashima, K. Expression and Function of the Cholinergic System in Immune Cells. Front. Immunol. 2017, 8, 1085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shelukhina, I.; Siniavin, A.; Kasheverov, I.; Ojomoko, L.; Tsetlin, V.; Utkin, Y. α7- and α9-Containing Nicotinic Acetylcholine Receptors in the Functioning of Immune System and in Pain. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 6524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Halder, N.; Yadav, S.; Lal, G. Neuroimmune Communication of the Cholinergic System in Gut Inflammation and Autoimmunity. Autoimmun. Rev. 2024, 23, 103678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fujii, T.; Horiguchi, K.; Sunaga, H.; Moriwaki, Y.; Misawa, H.; Kasahara, T.; Tsuji, S.; Kawashima, K. SLURP-1, an Endogenous α7 Nicotinic Acetylcholine Receptor Allosteric Ligand, Is Expressed in CD205(+) Dendritic Cells in Human Tonsils and Potentiates Lymphocytic Cholinergic Activity. J. Neuroimmunol. 2014, 267, 43–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pavlov, V.A.; Tracey, K.J. The Vagus Nerve and the Inflammatory Reflex—Linking Immunity and Metabolism. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 2012, 8, 743–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujii, T.; Mashimo, M.; Moriwaki, Y.; Misawa, H.; Ono, S.; Horiguchi, K.; Kawashima, K. Physiological Functions of the Cholinergic System in Immune Cells. J. Pharmacol. Sci. 2017, 134, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mashimo, M.; Komori, M.; Matsui, Y.Y.; Murase, M.X.; Fujii, T.; Takeshima, S.; Okuyama, H.; Ono, S.; Moriwaki, Y.; Misawa, H.; et al. Distinct Roles of α7 nAChRs in Antigen-Presenting Cells and CD4+ T Cells in the Regulation of T Cell Differentiation. Front. Immunol. 2019, 10, 1102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malin, S.G.; Shavva, V.S.; Tarnawski, L.; Olofsson, P.S. Functions of Acetylcholine-Producing Lymphocytes in Immunobiology. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 2020, 62, 115–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, H.; Yepuri, N.; Meng, Q.; Dhawan, R.; Leech, C.A.; Chepurny, O.G.; Holz, G.G.; Cooney, R.N. Therapeutic Potential of α7 Nicotinic Acetylcholine Receptor Agonists to Combat Obesity, Diabetes, and Inflammation. Rev. Endocr. Metab. Disord. 2020, 21, 431–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olofsson, P.S.; Steinberg, B.E.; Sobbi, R.; Cox, M.A.; Ahmed, M.N.; Oswald, M.; Szekeres, F.; Hanes, W.M.; Introini, A.; Liu, S.F.; et al. Blood Pressure Regulation by CD4+ Lymphocytes Expressing Choline Acetyltransferase. Nat. Biotechnol. 2016, 34, 1066–1071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drummond, G.R.; Vinh, A.; Guzik, T.J.; Sobey, C.G. Immune Mechanisms of Hypertension. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2019, 19, 517–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhawan, S.; De Palma, G.; Willemze, R.A.; Hilbers, F.W.; Verseijden, C.; Luyer, M.D.; Nuding, S.; Wehkamp, J.; Souwer, Y.; de Jong, E.C.; et al. Acetylcholine-Producing T Cells in the Intestine Regulate Antimicrobial Peptide Expression and Microbial Diversity. Am. J. Physiol.-Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 2016, 311, G920–G933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, S.; Wang, Y.; Li, H. The Regulation Effect of α7nAChRs and M1AChRs on Inflammation and Immunity in Sepsis. Mediat. Inflamm. 2021, 2021, 9059601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chrousos, G.P. The Role of Stress and the Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Adrenal Axis in the Pathogenesis of the Metabolic Syndrome: Neuro-Endocrine and Target Tissue-Related Causes. Int. J. Obes. 2000, 24 (Suppl. S2), S50–S55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsigos, C.; Chrousos, G.P. Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Adrenal Axis, Neuroendocrine Factors and Stress. J. Psychosom. Res. 2002, 53, 865–871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.; Wu, X. Modulation of the Gut Microbiota in Memory Impairment and Alzheimer’s Disease via the Inhibition of the Parasympathetic Nervous System. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 13574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gitler, A.; Bar Yosef, Y.; Kotzer, U.; Levine, A.D. Harnessing Non-Invasive Vagal Neuromodulation: HRV Biofeedback and SSP for Cardiovascular and Autonomic Regulation (Review). Med. Int. 2025, 5, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cork, S.C. The Role of the Vagus Nerve in Appetite Control: Implications for the Pathogenesis of Obesity. J. Neuroendocrinol. 2018, 30, e12643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Longo, S.; Rizza, S.; Federici, M. Microbiota-Gut-Brain Axis: Relationships among the Vagus Nerve, Gut Microbiota, Obesity, and Diabetes. Acta Diabetol. 2023, 60, 1007–1017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Duan, C.; Du, X.; Zhu, Y.; Wang, L.; Hu, J.; Sun, Y. Vagus Nerve and Gut-Brain Communication. Neuroscientist 2025, 31, 262–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Jian, Y.P.; Zhang, Y.N.; Li, Y.; Gu, L.T.; Sun, H.H.; Liu, M.D.; Zhou, H.L.; Wang, Y.S.; Xu, Z.X. Short-Chain Fatty Acids in Diseases. Cell Commun. Signal. 2023, 21, 212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Riordan, K.J.; Collins, M.K.; Moloney, G.M.; Knox, E.G.; Aburto, M.R.; Fülling, C.; Morley, S.J.; Clarke, G.; Schellekens, H.; Cryan, J.F. Short Chain Fatty Acids: Microbial Metabolites for Gut-Brain Axis Signalling. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 2022, 546, 111572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, H.; Leyrolle, Q.; Koistinen, V.; Kärkkäinen, O.; Layé, S.; Delzenne, N.; Hanhineva, K. Microbiota-Derived Metabolites as Drivers of Gut-Brain Communication. Gut Microbes 2022, 14, 2102878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guzel, T.; Mirowska-Guzel, D. The Role of Serotonin Neurotransmission in Gastrointestinal Tract and Pharmacotherapy. Molecules 2022, 27, 1680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Yang, Q.; Liu, X. The Microbiota-Gut-Brain Axis and Neurodevelopmental Disorders. Protein Cell 2023, 14, 762–775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- You, M.; Chen, N.; Yang, Y.; Cheng, L.; He, H.; Cai, Y.; Liu, Y.; Liu, H.; Hong, G. The gut microbiota-brain axis in neurological disorders. MedComm 2024, 5, e656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bano, N.; Khan, S.; Ahamad, S.; Kanshana, J.S.; Dar, N.J.; Khan, S.; Nazir, A.; Bhat, S.A. Microglia and Gut Microbiota: A Double-Edged Sword in Alzheimer’s Disease. Ageing Res. Rev. 2024, 101, 102515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sebastiani, L.; Di Gruttola, F.; Incognito, O.; Menardo, E.; Santarcangelo, E.L. The Higher the Basal Vagal Tone the Better the Motor Imagery Ability. Arch. Ital. Biol. 2019, 157, 3–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Décarie-Spain, L.; Hayes, A.M.R.; Lauer, L.T.; Kanoski, S.E. The Gut-Brain Axis and Cognitive Control: A Role for the Vagus Nerve. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 2024, 156, 201–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavlov, V.A. The Evolving Obesity Challenge: Targeting the Vagus Nerve and the Inflammatory Reflex in the Response. Pharmacol. Ther. 2021, 222, 107794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weissman, D.G.; Mendes, W.B. Correlation of Sympathetic and Parasympathetic Nervous System Activity during Rest and Acute Stress Tasks. Int. J. Psychophysiol. 2021, 162, 60–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurhaluk, N. Supplementation with L-Arginine and Nitrates vs Age and Individual Physiological Reactivity. Nutr. Rev. 2024, 82, 1239–1259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kurhaluk, N. The Effectiveness of L-Arginine in Clinical Conditions Associated with Hypoxia. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 8205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finkel, T.; Menazza, S.; Holmström, K.M.; Parks, R.J.; Liu, J.; Sun, J.; Liu, J.; Pan, X.; Murphy, E. The Ins and Outs of Mitochondrial Calcium. Circ. Res. 2015, 116, 1810–1819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, A.; Zhang, Z.; Ding, Q.; Yang, Y.; Bindelle, J.; Ran, C.; Zhou, Z. Intestinal Cetobacterium and Acetate Modify Glucose Homeostasis via Parasympathetic Activation in Zebrafish. Gut Microbes 2021, 13, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurhaluk, N.; Lukash, O.; Kamiński, P.; Tkaczenko, H. Adaptive Effects of Intermittent Hypoxia Training on Oxygen-Dependent Processes as a Potential Therapeutic Strategy Tool. Cell. Physiol. Biochem. 2024, 58, 226–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurhaluk, N.; Lukash, O.; Kamiński, P.; Tkaczenko, H. L-Arginine and Intermittent Hypoxia Are Stress-Limiting Factors in Male Wistar Rat Models. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 12364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naeini, S.H.; Mavaddatiyan, L.; Kalkhoran, Z.R.; Taherkhani, S.; Talkhabi, M. Alpha-Ketoglutarate as a Potent Regulator for Lifespan and Healthspan: Evidences and Perspectives. Exp. Gerontol. 2023, 175, 112154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serebrovskaya, T.V. Intermittent Hypoxia Research in the Former Soviet Union and the Commonwealth of Independent States: History and Review of the Concept and Selected Applications. High Alt. Med. Biol. 2002, 3, 205–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Faassen, E.E.; Bahrami, S.; Feelisch, M.; Hogg, N.; Kelm, M.; Kim-Shapiro, D.B.; Kozlov, A.V.; Li, H.; Lundberg, J.O.; Mason, R.; et al. Nitrite as Regulator of Hypoxic Signaling in Mammalian Physiology. Med. Res. Rev. 2009, 29, 683–741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Serebrovskaya, T.V.; Xi, L. Intermittent Hypoxia Training as Non-Pharmacologic Therapy for Cardiovascular Diseases: Practical Analysis on Methods and Equipment. Exp. Biol. Med. 2016, 241, 1708–1723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wessler, I.; Kirkpatrick, C.J.; Racké, K. The Cholinergic ‘Pitfall’: Acetylcholine, a Universal Cell Molecule in Biological Systems, Including Humans. Clin. Exp. Pharmacol. Physiol. 1999, 26, 198–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wessler, I.; Kilbinger, H.; Bittinger, F.; Kirkpatrick, C.J. The Biological Role of Non-Neuronal Acetylcholine in Plants and Humans. Jpn. J. Pharmacol. 2001, 85, 2–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellocchi, C.; Carandina, A.; Montinaro, B.; Targetti, E.; Furlan, L.; Rodrigues, G.D.; Tobaldini, E.; Montano, N. The Interplay between Autonomic Nervous System and Inflammation across Systemic Autoimmune Diseases. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 2449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gergalova, G.; Lykhmus, O.; Kalashnyk, O.; Koval, L.; Chernyshov, V.; Kryukova, E.; Tsetlin, V.; Komisarenko, S.; Skok, M. Mitochondria Express α7 Nicotinic Acetylcholine Receptors to Regulate Ca2+ Accumulation and Cytochrome c Release: Study on Isolated Mitochondria. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e31361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Skok, M.; Gergalova, G.; Lykhmus, O.; Kalashnyk, O.; Koval, L.; Uspenska, K. Nicotinic Acetylcholine Receptors in Mitochondria: Subunit Composition, Function and Signaling. Neurotransmitter 2016, 3, e1290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, W.; Cunlin, G.; Lu, H.; Yuanqing, Z.; Yanjun, T.; Qiong, W. Neuroprotective Effect of Intermittent Hypobaric Hypoxia Preconditioning on Cerebral Ischemia/Reperfusion in Rats. Int. J. Clin. Exp. Pathol. 2020, 13, 2860–2869. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Q.; Zhao, W.; Li, S.; Ding, Y.; Wang, Y.; Ji, X. Intermittent Hypoxia Conditioning: A Potential Multi-Organ Protective Therapeutic Strategy. Int. J. Med. Sci. 2023, 20, 1551–1561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bekker, I.; Kooistra, A.; van Dijk, P.R.; Lefrandt, J.D.; Veeger, N.J.G.M.; van Beek, A.P. The Influence of Exercise and Physical Activity on Autonomic Nervous System Function Measured by Heart Rate Variability in Individuals with Type 1 Diabetes Mellitus—A Systematic Review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 7096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grässler, B.; Thielmann, B.; Böckelmann, I.; Hökelmann, A. Effects of Different Exercise Interventions on Heart Rate Variability and Cardiovascular Health Factors in Older Adults: A Systematic Review. Eur. Rev. Aging Phys. Act. 2021, 18, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Malahi, O.; Mohajeri, D.; Mincu, R.; Bäuerle, A.; Rothenaicher, K.; Knuschke, R.; Rammos, C.; Rassaf, T.; Lortz, J. Beneficial Impacts of Physical Activity on Heart Rate Variability: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0299793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ristori, S.; Bertoni, G.; Bientinesi, E.; Monti, D. The Role of Nutraceuticals and Functional Foods in Mitigating Cellular Senescence and Its Related Aspects: A Key Strategy for Delaying or Preventing Aging and Neurodegenerative Disorders. Nutrients 2025, 17, 1837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tkaczenko, H.; Kurhaluk, N. Antioxidant-Rich Functional Foods and Exercise: Unlocking Metabolic Health Through Nrf2 and Related Pathways. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 1098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Meijel, R.L.J.; Venema, K.; Canfora, E.E.; Blaak, E.E.; Goossens, G.H. Mild Intermittent Hypoxia Exposure Alters Gut Microbiota Composition in Men with Overweight and Obesity. Benef. Microbes 2022, 13, 355–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Meijel, R.L.J.; Wang, P.; Bouwman, F.; Blaak, E.E.; Mariman, E.C.M.; Goossens, G.H. The Effects of Mild Intermittent Hypoxia Exposure on the Abdominal Subcutaneous Adipose Tissue Proteome in Overweight and Obese Men: A First-in-Human Randomized, Single-Blind, and Cross-Over Study. Front. Physiol. 2022, 12, 791588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moreno-Indias, I.; Torres, M.; Sanchez-Alcoholado, L.; Cardona, F.; Almendros, I.; Gozal, D.; Montserrat, J.M.; Queipo-Ortuño, M.I.; Farré, R. Normoxic Recovery Mimicking Treatment of Sleep Apnea Does Not Reverse Intermittent Hypoxia-Induced Bacterial Dysbiosis and Low-Grade Endotoxemia in Mice. Sleep 2016, 39, 1891–1897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, W.; Sun, L.; Yue, H.; Guo, X.; Chen, L.; Zhang, J.; Chen, Z.; Wang, Y.; Wang, J.; Lei, W. Associations of Intermittent Hypoxia Burden with Gut Microbiota Dysbiosis in Adult Patients with Obstructive Sleep Apnea. Nat. Sci. Sleep 2024, 16, 1483–1495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olson, C.A.; Iñiguez, A.J.; Yang, G.E.; Fang, P.; Pronovost, G.N.; Jameson, K.G.; Rendon, T.K.; Paramo, J.; Barlow, J.T.; Ismagilov, R.F.; et al. Alterations in the Gut Microbiota Contribute to Cognitive Impairment Induced by the Ketogenic Diet and Hypoxia. Cell Host Microbe 2021, 29, 1378–1392.e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, D.; Xue, J.; Miyamoto, Y.; Poulsen, O.; Eckmann, L.; Haddad, G.G. Microbiota Modulates Cardiac Transcriptional Responses to Intermittent Hypoxia and Hypercapnia. Front. Physiol. 2021, 12, 680275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, M.; Liang, X.; Zhu, T.; Xu, T.; Xie, L.; Feng, Y. Reoxygenation Mitigates Intermittent Hypoxia-Induced Systemic Inflammation and Gut Microbiota Dysbiosis in High-Fat Diet-Induced Obese Rats. Nat. Sci. Sleep 2024, 16, 517–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, C.; Shi, S. Gut Microbiota and Metabolic Profiles in Chronic Intermittent Hypoxia-Induced Rats: Disease-Associated Dysbiosis and Metabolic Disturbances. Front. Endocrinol. 2024, 14, 1224396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bodkin, D.; Cai, C.L.; Manlapaz-Mann, A.; Mustafa, G.; Aranda, J.V.; Beharry, K.D. Neonatal Intermittent Hypoxia, Fish Oil, and/or Antioxidant Supplementation on Gut Microbiota in Neonatal Rats. Pediatr. Res. 2022, 92, 109–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurhaluk, N.; Kamiński, P.; Bilski, R.; Kołodziejska, R.; Woźniak, A.; Tkaczenko, H. Role of Antioxidants in Modulating the Microbiota-Gut-Brain Axis and Their Impact on Neurodegenerative Diseases. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 3658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tremblay, R.; Lee, S.; Rudy, B. GABAergic Interneurons in the Neocortex: From Cellular Properties to Circuits. Neuron 2016, 91, 260–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bercik, P.; Park, A.J.; Sinclair, D.; Khoshdel, A.; Lu, J.; Huang, X.; Deng, Y.; Blennerhassett, P.A.; Fahnestock, M.; Moine, D.; et al. The Anxiolytic Effect of Bifidobacterium longum NCC3001 Involves Vagal Pathways for Gut-Brain Communication. Neurogastroenterol. Motil. 2011, 23, 1132–1139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lei, A.A.; Phang, V.W.X.; Lee, Y.Z.; Kow, A.S.F.; Tham, C.L.; Ho, Y.C.; Lee, M.T. Chronic Stress-Associated Depressive Disorders: The Impact of HPA Axis Dysregulation and Neuroinflammation on the Hippocampus—A Mini Review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 2940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, D.; Ren, L.; Zhang, W.; Wu, S.; Yu, M.; He, X.; Wei, Z. Therapeutic Effects and Mechanisms of Fecal Microbiota Transplantation on EAE Partly through HPA Axis-Mediated Neuroendocrine Regulation. Heliyon 2024, 10, e33214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, H.; Liu, P.; Sun, T.; Li, Y.; Wu, J.; Huang, Y.; Yang, J.; Yuan, M.; Zhang, J.; Yang, J.; et al. Dynamic Alterations of Depressive-Like Behaviors, Gut Microbiome, and Fecal Metabolome in Social Defeat Stress Mice. Transl. Psychiatry 2025, 15, 115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borrego-Ruiz, A.; Borrego, J.J. An Updated Overview on the Relationship between Human Gut Microbiome Dysbiosis and Psychiatric and Psychological Disorders. Prog. Neuro-Psychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry 2024, 128, 110861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warren, A.; Nyavor, Y.; Beguelin, A.; Frame, L.A. Dangers of the Chronic Stress Response in the Context of the Microbiota-Gut-Immune-Brain Axis and Mental Health: A Narrative Review. Front. Immunol. 2024, 15, 1365871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- P, S.; Vellapandian, C. Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Adrenal (HPA) Axis: Unveiling the Potential Mechanisms Involved in Stress-Induced Alzheimer’s Disease and Depression. Cureus 2024, 16, e67595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huo, R.; Zeng, B.; Zeng, L.; Cheng, K.; Li, B.; Luo, Y.; Wang, H.; Zhou, C.; Fang, L.; Li, W.; et al. Microbiota Modulate Anxiety-Like Behavior and Endocrine Abnormalities in Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Adrenal Axis. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2017, 7, 489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saturio, S.; Nogacka, A.M.; Alvarado-Jasso, G.M.; Salazar, N.; de Los Reyes-Gavilán, C.G.; Gueimonde, M.; Arboleya, S. Role of Bifidobacteria on Infant Health. Microorganisms 2021, 9, 2415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, H.; Perkins, M.H.; Novaes, L.S.; Qian, F.; Zhang, T.; Neckel, P.H.; Scherer, S.; Ley, R.E.; Han, W.; de Araujo, I.E. Stress-Sensitive Neural Circuits Change the Gut Microbiome via Duodenal Glands. Cell 2024, 187, 5393–5412.e30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perry, R.J.; Peng, L.; Barry, N.A.; Cline, G.W.; Zhang, D.; Cardone, R.L.; Petersen, K.F.; Kibbey, R.G.; Goodman, A.L.; Shulman, G.I. Acetate Mediates a Microbiome-Brain-β-Cell Axis to Promote Metabolic Syndrome. Nature 2016, 534, 213–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.X.; Wang, Y.P. Gut Microbiota-Brain Axis. Chin. Med. J. 2016, 129, 2373–2380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Y.; Eguchi, A.; Wan, X.; Chang, L.; Wang, X.; Qu, Y.; Mori, C.; Hashimoto, K. A Role of Gut-Microbiota-Brain Axis via Subdiaphragmatic Vagus Nerve in Depression-Like Phenotypes in Chrna7 Knock-Out Mice. Prog. Neuro-Psychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry 2023, 120, 110652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ortega, V.A.; Mercer, E.M.; Giesbrecht, G.F.; Arrieta, M.C. Evolutionary Significance of the Neuroendocrine Stress Axis on Vertebrate Immunity and the Influence of the Microbiome on Early-Life Stress Regulation and Health Outcomes. Front. Microbiol. 2021, 12, 634539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Yao, J.; Yang, C.; Yu, S.; Yang, Z.; Wang, L.; Li, S.; He, N. Gut Microbiota-Derived Short Chain Fatty Acids Act as Mediators of the Gut-Liver-Brain Axis. Metab. Brain Dis. 2025, 40, 122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berni Canani, R.; Di Costanzo, M.; Leone, L. The Epigenetic Effects of Butyrate: Potential Therapeutic Implications for Clinical Practice. Clin. Epigenet. 2012, 4, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Lu, Y.; Xue, G.; Han, L.; Jia, H.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, J.; Liu, P.; Yang, C.; Zhou, Y. Role of Short-Chain Fatty Acids in Host Physiology. Anim. Models Exp. Med. 2024, 7, 641–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lapp, H.E.; Bartlett, A.A.; Hunter, R.G. Stress and Glucocorticoid Receptor Regulation of Mitochondrial Gene Expression. J. Mol. Endocrinol. 2019, 62, R121–R128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sorrells, S.F.; Sapolsky, R.M. An Inflammatory Review of Glucocorticoid Actions in the CNS. Brain Behav. Immun. 2007, 21, 259–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikolić, T.; Bogosavljević, M.V.; Stojković, T.; Kanazir, S.; Lončarević-Vasiljković, N.; Radonjić, N.V.; Popić, J.; Petronijević, N. Effects of Antipsychotics on the Hypothalamus-Pituitary-Adrenal Axis in a Phencyclidine Animal Model of Schizophrenia. Cells 2024, 13, 1425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strehl, C.; Ehlers, L.; Gaber, T.; Buttgereit, F. Glucocorticoids—All-Rounders Tackling the Versatile Players of the Immune System. Front. Immunol. 2019, 10, 1744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shahini, A.; Shahini, A. Role of Interleukin-6-Mediated Inflammation in the Pathogenesis of Inflammatory Bowel Disease: Focus on the Available Therapeutic Approaches and Gut Microbiome. J. Cell Commun. Signal. 2023, 17, 55–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nikisch, G. Involvement and Role of Antidepressant Drugs of the Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Adrenal Axis and Glucocorticoid Receptor Function. Neuro Endocrinol. Lett. 2009, 30, 11–16. [Google Scholar]

- Rusch, J.A.; Layden, B.T.; Dugas, L.R. Signalling Cognition: The Gut Microbiota and Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Adrenal Axis. Front. Endocrinol. 2023, 14, 1130689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasarello, K.; Cudnoch-Jedrzejewska, A.; Czarzasta, K. Communication of Gut Microbiota and Brain via Immune and Neuroendocrine Signaling. Front. Microbiol. 2023, 14, 1118529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Sun, Z.; Yang, T.; Lin, F.; Ye, S.; Yan, J.; Li, T.; Chen, J. Sodium Butyrate Facilitates CRHR2 Expression to Alleviate HPA Axis Hyperactivity in Autism-Like Rats Induced by Prenatal Lipopolysaccharides through Histone Deacetylase Inhibition. mSystems 2023, 8, e0041523, Erratrum mSystems 2023, 8, e0091523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swaab, D.F.; Bao, A.M.; Lucassen, P.J. The Stress System in the Human Brain in Depression and Neurodegeneration. Ageing Res. Rev. 2005, 4, 141–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savulescu-Fiedler, I.; Benea, S.N.; Căruntu, C.; Nancoff, A.S.; Homentcovschi, C.; Bucurica, S. Rewiring the Brain Through the Gut: Insights into Microbiota-Nervous System Interactions. Curr. Issues Mol. Biol. 2025, 47, 489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lund, M.L.; Egerod, K.L.; Engelstoft, M.S.; Dmytriyeva, O.; Theodorsson, E.; Patel, B.A.; Schwartz, T.W. Enterochromaffin 5-HT Cells—A Major Target for GLP-1 and Gut Microbial Metabolites. Mol. Metab. 2018, 11, 70–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, C.M.; Farrand, A.Q.; Andresen, M.C.; Beaumont, E. Vagus Nerve Stimulation Activates Nucleus of Solitary Tract Neurons via Supramedullary Pathways. J. Physiol. 2021, 599, 5261–5279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pokusaeva, K.; Johnson, C.; Luk, B.; Uribe, G.; Fu, Y.; Oezguen, N.; Matsunami, R.K.; Lugo, M.; Major, A.; Mori-Akiyama, Y.; et al. GABA-Producing Bifidobacterium dentium Modulates Visceral Sensitivity in the Intestine. Neurogastroenterol. Motil. 2017, 29, e12904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tette, F.M.; Kwofie, S.K.; Wilson, M.D. Therapeutic Anti-Depressant Potential of Microbial GABA Produced by Lactobacillus rhamnosus Strains for GABAergic Signaling Restoration and Inhibition of Addiction-Induced HPA Axis Hyperactivity. Curr. Issues Mol. Biol. 2022, 44, 1434–1451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Jonge, W.J.; Ulloa, L. The Alpha7 Nicotinic Acetylcholine Receptor as a Pharmacological Target for Inflammation. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2007, 151, 915–929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agus, A.; Planchais, J.; Sokol, H. Gut Microbiota Regulation of Tryptophan Metabolism in Health and Disease. Cell Host Microbe 2018, 23, 716–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savelieva, K.V.; Zhao, S.; Pogorelov, V.M.; Rajan, I.; Yang, Q.; Cullinan, E.; Lanthorn, T.H. Genetic Disruption of Both Tryptophan Hydroxylase Genes Dramatically Reduces Serotonin and Affects Behavior in Models Sensitive to Antidepressants. PLoS ONE 2008, 3, e3301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Réus, G.Z.; Jansen, K.; Titus, S.; Carvalho, A.F.; Gabbay, V.; Quevedo, J. Kynurenine Pathway Dysfunction in the Pathophysiology and Treatment of Depression: Evidences from Animal and Human Studies. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2015, 68, 316–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, K.; Mu, C.L.; Farzi, A.; Zhu, W.Y. Tryptophan Metabolism: A Link Between the Gut Microbiota and Brain. Adv. Nutr. 2020, 11, 709–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaw, C.; Hess, M.; Weimer, B.C. Microbial-Derived Tryptophan Metabolites and Their Role in Neurological Disease: Anthranilic Acid and Anthranilic Acid Derivatives. Microorganisms 2023, 11, 1825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaufman, D.L.; Houser, C.R.; Tobin, A.J. Two Forms of the Gamma-Aminobutyric Acid Synthetic Enzyme Glutamate Decarboxylase Have Distinct Intraneuronal Distributions and Cofactor Interactions. J. Neurochem. 1991, 56, 720–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yunes, R.A.; Poluektova, E.U.; Dyachkova, M.S.; Klimina, K.M.; Kovtun, A.S.; Averina, O.V.; Orlova, V.S.; Danilenko, V.N. GABA Production and Structure of gadB/gadC Genes in Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium Strains from Human Microbiota. Anaerobe 2016, 42, 197–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dantzer, R.; Cohen, S.; Russo, S.J.; Dinan, T.G. Resilience and Immunity. Brain Behav. Immun. 2018, 74, 28–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Rossum, T.; Haiß, A.; Knoll, R.L.; Marißen, J.; Podlesny, D.; Pagel, J.; Bleskina, M.; Vens, M.; Fortmann, I.; Siller, B.; et al. Bifidobacterium and Lactobacillus Probiotics and Gut Dysbiosis in Preterm Infants: The PRIMAL Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Pediatr. 2024, 178, 985–995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Madison, A.; Kiecolt-Glaser, J.K. Stress, Depression, Diet, and the Gut Microbiota: Human-Bacteria Interactions at the Core of Psychoneuroimmunology and Nutrition. Curr. Opin. Behav. Sci. 2019, 28, 105–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Xue, P.; Zhang, H.; Tan, C.; Zhao, S.; Li, X.; Sun, L.; Zheng, H.; Wang, J.; Zhang, B.; et al. Gut Brain Interaction Theory Reveals Gut Microbiota Mediated Neurogenesis and Traditional Chinese Medicine Research Strategies. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2022, 12, 1072341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brun, P.; Akbarali, H.I.; Castagliuolo, I. Editorial: The Gut Microbiota Orchestrates the Neuronal-Immune System. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2021, 9, 672685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, A.; Fonseca, S.; Carding, S.R. Gut Microbes and Metabolites as Modulators of Blood-Brain Barrier Integrity and Brain Health. Gut Microbes 2020, 11, 135–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Missiego-Beltrán, J.; Beltrán-Velasco, A.I. The Role of Microbial Metabolites in the Progression of Neurodegenerative Diseases—Therapeutic Approaches: A Comprehensive Review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 10041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Riordan, K.J.; Moloney, G.M.; Keane, L.; Clarke, G.; Cryan, J.F. The Gut Microbiota-Immune-Brain Axis: Therapeutic Implications. Cell Rep. Med. 2025, 6, 101982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janssens, S.; Beyaert, R. Role of Toll-Like Receptors in Pathogen Recognition. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2003, 16, 637–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sameer, A.S.; Nissar, S. Toll-Like Receptors (TLRs): Structure, Functions, Signaling, and Role of Their Polymorphisms in Colorectal Cancer Susceptibility. BioMed Res. Int. 2021, 2021, 1157023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutiérrez-Vázquez, C.; Quintana, F.J. Regulation of the Immune Response by the Aryl Hydrocarbon Receptor. Immunity 2018, 48, 19–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esser, C. The Aryl Hydrocarbon Receptor in Immunity: Tools and Potential. Methods Mol. Biol. 2016, 1371, 239–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Facchin, S.; Bertin, L.; Bonazzi, E.; Lorenzon, G.; De Barba, C.; Barberio, B.; Zingone, F.; Maniero, D.; Scarpa, M.; Ruffolo, C.; et al. Short-Chain Fatty Acids and Human Health: From Metabolic Pathways to Current Therapeutic Implications. Life 2024, 14, 559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harsono, A.D.; Prasetyono, T.O.H.; Dilogo, I.H. The Role of Interleukin 10 in Keloid Therapy: A Literature Review. Ann. Plast. Surg. 2022, 88, 617–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Der Zanden, E.P.; Boeckxstaens, G.E.; de Jonge, W.J. The Vagus Nerve as a Modulator of Intestinal Inflammation. Neurogastroenterol. Motil. 2009, 21, 6–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karimi, K.; Bienenstock, J.; Wang, L.; Forsythe, P. The Vagus Nerve Modulates CD4+ T Cell Activity. Brain Behav. Immun. 2010, 24, 316–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarnawski, L.; Shavva, V.S.; Kort, E.J.; Zhuge, Z.; Nilsson, I.; Gallina, A.L.; Martínez-Enguita, D.; Sahlgren, B.H.; Weiland, M.; Caravaca, A.S.; et al. Cholinergic Regulation of Vascular Endothelial Function by Human ChAT+ T Cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2023, 120, e2212476120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Browning, K.N.; Travagli, R.A. Central Nervous System Control of Gastrointestinal Motility and Secretion and Modulation of Gastrointestinal Functions. Compr. Physiol. 2014, 4, 1339–1368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rocha, B.S.; Laranjinha, J. Nitrate from Diet Might Fuel Gut Microbiota Metabolism: Minding the Gap Between Redox Signaling and Inter-Kingdom Communication. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2020, 149, 37–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Shao, R.; Wang, N.; Zhou, N.; Du, K.; Shi, J.; Wang, Y.; Zhao, Z.; Ye, X.; Zhang, X.; et al. Sulforaphane Activates a Lysosome-Dependent Transcriptional Program to Mitigate Oxidative Stress. Autophagy 2021, 17, 872–887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Xu, J.; Chen, Y. Regulation of Neurotransmitters by the Gut Microbiota and Effects on Cognition in Neurological Disorders. Nutrients 2021, 13, 2099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mhanna, A.; Martini, N.; Hmaydoosh, G.; Hamwi, G.; Jarjanazi, M.; Zaifah, G.; Kazzazo, R.; Mohamad, A.H.; Alshehabi, Z. The Correlation Between Gut Microbiota and Both Neurotransmitters and Mental Disorders: A Narrative Review. Medicine 2024, 103, e37114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ning, P.; Lin, S.; Shi, Y.; Liu, T. Potential Role of Gut-Related Factors in the Pathology of Cartilage in Osteoarthritis. Front. Nutr. 2025, 11, 1515806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Feng, W.; Wu, J.; Cui, H.; Wang, Y.; Liang, T.; An, J.; Chen, W.; Guo, Z.; Lei, H. A Narrative Review: Immunometabolic Interactions of Host-Gut Microbiota and Botanical Active Ingredients in Gastrointestinal Cancers. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 9096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oshaghi, M.; Kourosh-Arami, M.; Roozbehkia, M. Role of Neurotransmitters in Immune-Mediated Inflammatory Disorders: A Crosstalk Between the Nervous and Immune Systems. Neurol. Sci. 2023, 44, 99–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMenamin, C.A.; Travagli, R.A.; Browning, K.N. Inhibitory Neurotransmission Regulates Vagal Efferent Activity and Gastric Motility. Exp. Biol. Med. 2016, 241, 1343–1350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Reardon, J.P.; Cristancho, P.; Peshek, A.D. Vagus Nerve Stimulation (VNS) and Treatment of Depression: To the Brainstem and Beyond. Psychiatry 2006, 3, 54–63. [Google Scholar]

- Carreno, F.R.; Frazer, A. Vagal Nerve Stimulation for Treatment-Resistant Depression. Neurotherapeutics 2017, 14, 716–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, N.; Sun, S.; Wang, P.; Sun, Y.; Hu, Q.; Wang, X. The Mechanism of Secretion and Metabolism of Gut-Derived 5-Hydroxytryptamine. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 7931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jovanovic, H.; Perski, A.; Berglund, H.; Savic, I. Chronic Stress Is Linked to 5-HT(1A) Receptor Changes and Functional Disintegration of the Limbic Networks. NeuroImage 2011, 55, 1178–1188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Browning, K.N. Role of Central Vagal 5-HT3 Receptors in Gastrointestinal Physiology and Pathophysiology. Front. Neurosci. 2015, 9, 413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broadbelt, K.G.; Paterson, D.S.; Rivera, K.D.; Trachtenberg, F.L.; Kinney, H.C. Neuroanatomic Relationships Between the GABAergic and Serotonergic Systems in the Developing Human Medulla. Auton. Neurosci. 2010, 154, 30–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, S.L.; O’Leary, G.H.; Austelle, C.W.; Gruber, E.; Kahn, A.T.; Manett, A.J.; Short, B.; Badran, B.W. A Review of Parameter Settings for Invasive and Non-Invasive Vagus Nerve Stimulation (VNS) Applied in Neurological and Psychiatric Disorders. Front. Neurosci. 2021, 15, 709436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Góralczyk-Bińkowska, A.; Szmajda-Krygier, D.; Kozłowska, E. The Microbiota-Gut-Brain Axis in Psychiatric Disorders. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 11245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazemi, A.; Noorbala, A.A.; Azam, K.; Eskandari, M.H.; Djafarian, K. Effect of Probiotic and Prebiotic vs Placebo on Psychological Outcomes in Patients with Major Depressive Disorder: A Randomized Clinical Trial. Clin. Nutr. 2019, 38, 522–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, P.; Chen, Y.; Zhu, H.; Wang, L.; Qian, X.; Zou, R.; Zhao, J.; Zhang, H.; Qian, L.; Wang, Q.; et al. Bifidobacterium breve CCFM1025 Attenuates Major Depression Disorder via Regulating Gut Microbiome and Tryptophan Metabolism: A Randomized Clinical Trial. Brain Behav. Immun. 2022, 100, 233–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, P.; Zou, R.; Wang, L.; Chen, Y.; Qian, X.; Zhao, J.; Zhang, H.; Qian, L.; Wang, Q.; Wang, G.; et al. Multi-Probiotics Ameliorate Major Depressive Disorder and Accompanying Gastrointestinal Syndromes via Serotonergic System Regulation. J. Adv. Res. 2023, 45, 117–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, X.; Lin, F.; Yang, F.; Chen, J.; Cai, W.; Zou, T. Gut Microbiome Characteristics of Comorbid Generalized Anxiety Disorder and Functional Gastrointestinal Disease: Correlation with Alexithymia and Personality Traits. Front. Psychiatry 2022, 13, 946808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, D.W.; Adams, J.B.; Vargason, T.; Santiago, M.; Hahn, J.; Krajmalnik-Brown, R. Distinct Fecal and Plasma Metabolites in Children with Autism Spectrum Disorders and Their Modulation after Microbiota Transfer Therapy. mSphere 2020, 5, e00314–e00320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nirmalkar, K.; Qureshi, F.; Kang, D.W.; Hahn, J.; Adams, J.B.; Krajmalnik-Brown, R. Shotgun Metagenomics Study Suggests Alteration in Sulfur Metabolism and Oxidative Stress in Children with Autism and Improvement after Microbiota Transfer Therapy. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 13481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ornish, D.; Madison, C.; Kivipelto, M.; Kemp, C.; McCulloch, C.E.; Galasko, D.; Artz, J.; Rentz, D.; Lin, J.; Norman, K.; et al. Effects of Intensive Lifestyle Changes on the Progression of Mild Cognitive Impairment or Early Dementia Due to Alzheimer’s Disease: A Randomized, Controlled Clinical Trial. Alzheimers Res. Ther. 2024, 16, 122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tran, T.T.T.; Corsini, S.; Kellingray, L.; Hegarty, C.; Le Gall, G.; Narbad, A.; Müller, M.; Tejera, N.; O’Toole, P.W.; Minihane, A.-M.; et al. APOE Genotype Influences the Gut Microbiome Structure and Function in Humans and Mice: Relevance for Alzheimer’s Disease Pathophysiology. FASEB J. 2019, 33, 8221–8231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ben-Yacov, O.; Godneva, A.; Rein, M.; Shilo, S.; Lotan-Pompan, M.; Weinberger, A.; Segal, E. Gut Microbiome Modulates the Effects of a Personalised Postprandial-Targeting (PPT) Diet on Cardiometabolic Markers: A Diet Intervention in Pre-Diabetes. Gut 2023, 72, 1486–1496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mei, L.; Yang, Z.; Zhang, X.; Liu, Z.; Wang, M.; Wu, X.; Chen, X.; Huang, Q.; Huang, R. Sustained Drug Treatment Alters the Gut Microbiota in Rheumatoid Arthritis. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 704089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cox, S.R.; Lindsay, J.O.; Fromentin, S.; Stagg, A.J.; McCarthy, N.E.; Galleron, N.; Ibraim, S.B.; Roume, H.; Levenez, F.; Pons, N.; et al. Effects of Low FODMAP Diet on Symptoms, Fecal Microbiome, and Markers of Inflammation in Patients with Quiescent Inflammatory Bowel Disease in a Randomized Trial. Gastroenterology 2020, 158, 176–188.e7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cignarella, F.; Cantoni, C.; Ghezzi, L.; Salter, A.; Dorsett, Y.; Chen, L.; Phillips, D.; Weinstock, G.M.; Fontana, L.; Cross, A.H.; et al. Intermittent Fasting Confers Protection in CNS Autoimmunity by Altering the Gut Microbiota. Cell Metab. 2018, 27, 1222–1235.e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Luo, S.; Ye, Y.; Yin, S.; Fan, J.; Xia, M. Intermittent Fasting Improves Cardiometabolic Risk Factors and Alters Gut Microbiota in Metabolic Syndrome Patients. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2021, 106, 64–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rottenberg, J.; Chambers, A.S.; Allen, J.J.; Manber, R. Cardiac Vagal Control in the Severity and Course of Depression: The Importance of Symptomatic Heterogeneity. J. Affect. Disord. 2007, 103, 173–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klusek, J.; LaFauci, G.; Adayev, T.; Brown, W.T.; Tassone, F.; Roberts, J.E. Reduced Vagal Tone in Women with the FMR1 Premutation Is Associated with FMR1 mRNA but Not Depression or Anxiety. J. Neurodev. Disord. 2017, 9, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, F.; Zhang, X.; Wang, S.; Jia, G.; Cheng, L. Vagus Nerve Stimulation Regulates the Th17/Treg Balance and Alleviates Lung Injury in Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome by Upregulating α7nAChR. Biomedicines 2025, 13, 1294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Komaroff, A.L.; Lipkin, W.I. ME/CFS and Long COVID Share Similar Symptoms and Biological Abnormalities: Road Map to the Literature. Front. Med. 2023, 10, 1187163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pope, B.S.; Wood, S.K. Advances in Understanding Mechanisms and Therapeutic Targets to Treat Comorbid Depression and Cardiovascular Disease. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2020, 116, 337–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iida, T.; Yokoyama, Y.; Wagatsuma, K.; Hirayama, D.; Nakase, H. Impact of Autophagy of Innate Immune Cells on Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Cells 2018, 8, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, Y.; Wu, M.; Song, S.; Bian, Y.; Shi, Y. TXNIP Deficiency Attenuates Renal Fibrosis by Modulating mTORC1/TFEB-Mediated Autophagy in Diabetic Kidney Disease. Ren. Fail. 2024, 46, 2338933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulfig, A.; Bader, V.; Varatnitskaya, M.; Lupilov, N.; Winklhofer, K.F.; Leichert, L.I. Hypochlorous Acid-Modified Human Serum Albumin Suppresses MHC Class II-Dependent Antigen Presentation in Pro-Inflammatory Macrophages. Redox Biol. 2021, 43, 101981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, E.J.; Wu, M.Y.; Ren, Z.Y.; Zheng, Y.; Ye, R.D.; Tan, C.S.H.; Wang, Y.; Lu, J.H. Targeting Macrophage Autophagy for Inflammation Resolution and Tissue Repair in Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Burn. Trauma 2023, 11, tkad004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiraly, S.; Stanley, J.; Eden, E.R. Lysosome-Mitochondrial Crosstalk in Cellular Stress and Disease. Antioxidants 2025, 14, 125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnson, J.L.; Jones, M.B.; Cobb, B.A. Polysaccharide A from the Capsule of Bacteroides fragilis Induces Clonal CD4+ T Cell Expansion. J. Biol. Chem. 2015, 290, 5007–5014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alula, K.M.; Theiss, A.L. Autophagy in Crohn’s Disease: Converging on Dysfunctional Innate Immunity. Cells 2023, 12, 1779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramos-Molina, B.; Queipo-Ortuño, M.I.; Lambertos, A.; Tinahones, F.J.; Peñafiel, R. Dietary and Gut Microbiota Polyamines in Obesity- and Age-Related Diseases. Front. Nutr. 2019, 6, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dekker, J.P.; Frank, K.M. Salmonella, Shigella, and Yersinia. Clin. Lab. Med. 2015, 35, 225–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, J.F.; Ning, Y.J.; Zhang, W.; Lu, Z.H.; Lin, L. T300A Polymorphism of ATG16L1 and Susceptibility to Inflammatory Bowel Diseases: A Meta-Analysis. World J. Gastroenterol. 2010, 16, 1258–1266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clement, M.; Raffort, J.; Lareyre, F.; Tsiantoulas, D.; Newland, S.; Lu, Y.; Masters, L.; Harrison, J.; Saveljeva, S.; Ma, M.K.; et al. Impaired Autophagy in CD11b+ Dendritic Cells Expands CD4+ Regulatory T Cells and Limits Atherosclerosis in Mice. Circ. Res. 2019, 125, 1019–1034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miao, Z.X.; Meng, H.; Wang, J.; Hou, X.T.; Cheng, W.W.; Liu, B.H.; Zhang, Q.G.; Yuan, S. Autophagy in Inflammatory Bowel Disease: Immunization, Etiology, and Therapeutic Potential. Front. Immunol. 2025, 16, 1543040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galluzzi, L.; Bravo-San Pedro, J.M.; Levine, B.; Green, D.R.; Kroemer, G. Pharmacological Modulation of Autophagy: Therapeutic Potential and Persisting Obstacles. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2017, 16, 487–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Ishima, T.; Zhang, J.; Qu, Y.; Chang, L.; Pu, Y.; Fujita, Y.; Tan, Y.; Wang, X.; Hashimoto, K. Ingestion of Lactobacillus intestinalis and Lactobacillus reuteri Causes Depression- and Anhedonia-Like Phenotypes in Antibiotic-Treated Mice via the Vagus Nerve. J. Neuroinflamm. 2020, 17, 241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, S.K.; Kim, D.H. Lactobacillus mucosae and Bifidobacterium longum Synergistically Alleviate Immobilization Stress-Induced Anxiety/Depression in Mice by Suppressing Gut Dysbiosis. J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2019, 29, 1369–1374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosi, A.; Banfi, D.; Bistoletti, M.; Giaroni, C.; Baj, A. Tryptophan Metabolites Along the Microbiota-Gut-Brain Axis: An Interkingdom Communication System Influencing the Gut in Health and Disease. Int. J. Tryptophan Res. 2020, 13, 1178646920928984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, T.S.; Mayer, E. Advances in Brain-Gut-Microbiome Interactions: A Comprehensive Update on Signaling Mechanisms, Disorders, and Therapeutic Implications. Cell. Mol. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2024, 18, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Vincenzo, F.; Del Gaudio, A.; Petito, V.; Lopetuso, L.R.; Scaldaferri, F. Gut Microbiota, Intestinal Permeability, and Systemic Inflammation: A Narrative Review. Intern. Emerg. Med. 2024, 19, 275–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, L.; Wang, D.; Pan, H.; Huang, L.; Sun, X.; He, C.; Wei, Q. Non-Invasive Vagus Nerve Stimulation in Cerebral Stroke: Current Status and Future Perspectives. Front. Neurosci. 2022, 16, 820665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yan, L.; Li, H.; Qian, Y.; Zhang, J.; Cong, S.; Zhang, X.; Wu, L.; Wang, Y.; Wang, M.; Yu, T. Transcutaneous Vagus Nerve Stimulation: A New Strategy for Alzheimer’s Disease Intervention Through the Brain-Gut-Microbiota Axis? Front. Aging Neurosci. 2024, 16, 1334887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faraji, N.; Payami, B.; Ebadpour, N.; Gorji, A. Vagus Nerve Stimulation and Gut Microbiota Interactions: A Novel Therapeutic Avenue for Neuropsychiatric Disorders. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2025, 169, 105990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garland, E.L.; Hanley, A.W.; Baker, A.K.; Howard, M.O. Biobehavioral Mechanisms of Mindfulness as a Treatment for Chronic Stress: An RDoC Perspective. Chronic Stress 2017, 1, 2470547017711912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerritsen, R.J.S.; Band, G.P.H. Breath of Life: The Respiratory Vagal Stimulation Model of Contemplative Activity. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2018, 12, 397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mörkl, S.; Narrath, M.; Schlotmann, D.; Sallmutter, M.T.; Putz, J.; Lang, J.; Brandstätter, A.; Pilz, R.; Lackner, H.K.; Goswami, N.; et al. Multi-Species Probiotic Supplement Enhances Vagal Nerve Function—Results of a Randomized Controlled Trial in Patients with Depression and Healthy Controls. Gut Microbes 2025, 17, 2492377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Antonino, D.; Teixeira, A.L.; Maia-Lopes, P.M.; Souza, M.C.; Sabino-Carvalho, J.L.; Murray, A.R.; Deuchars, J.; Vianna, L.C. Non-Invasive Vagus Nerve Stimulation Acutely Improves Spontaneous Cardiac Baroreflex Sensitivity in Healthy Young Men: A Randomized Placebo-Controlled Trial. Brain Stimul. 2017, 10, 875–881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clancy, J.A.; Mary, D.A.; Witte, K.K.; Greenwood, J.P.; Deuchars, S.A.; Deuchars, J. Non-Invasive Vagus Nerve Stimulation in Healthy Humans Reduces Sympathetic Nerve Activity. Brain Stimul. 2014, 7, 871–877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ansari, F.; Neshat, M.; Pourjafar, H.; Jafari, S.M.; Samakkhah, S.A.; Mirzakhani, E. The Role of Probiotics and Prebiotics in Modulating of the Gut-Brain Axis. Front. Nutr. 2023, 10, 1173660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, P.; Chen, C.; Patil, S.; Dong, S. Unveiling the Therapeutic Symphony of Probiotics, Prebiotics, and Postbiotics in Gut-Immune Harmony. Front. Nutr. 2024, 11, 1355542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monda, V.; Villano, I.; Messina, A.; Valenzano, A.; Esposito, T.; Moscatelli, F.; Viggiano, A.; Cibelli, G.; Chieffi, S.; Monda, M.; et al. Exercise Modifies the Gut Microbiota with Positive Health Effects. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2017, 2017, 3831972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strasser, B.; Wolters, M.; Weyh, C.; Krüger, K.; Ticinesi, A. The Effects of Lifestyle and Diet on Gut Microbiota Composition, Inflammation and Muscle Performance in Our Aging Society. Nutrients 2021, 13, 2045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aljeradat, B.; Kumar, D.; Abdulmuizz, S.; Kundu, M.; Almealawy, Y.F.; Batarseh, D.R.; Atallah, O.; Ennabe, M.; Alsarafandi, M.; Alan, A.; et al. Neuromodulation and the Gut-Brain Axis: Therapeutic Mechanisms and Implications for Gastrointestinal and Neurological Disorders. Pathophysiology 2024, 31, 244–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohebali, N.; Weigel, M.; Hain, T.; Sütel, M.; Bull, J.; Kreikemeyer, B.; Breitrück, A. Faecalibacterium prausnitzii, Bacteroides faecis and Roseburia intestinalis Attenuate Clinical Symptoms of Experimental Colitis by Regulating Treg/Th17 Cell Balance and Intestinal Barrier Integrity. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2023, 167, 115568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moreno-Indias, I.; Torres, M.; Montserrat, J.M.; Sanchez-Alcoholado, L.; Cardona, F.; Tinahones, F.J.; Gozal, D.; Poroyko, V.A.; Navajas, D.; Queipo-Ortuño, M.I.; et al. Intermittent Hypoxia Alters Gut Microbiota Diversity in a Mouse Model of Sleep Apnoea. Eur. Respir. J. 2015, 45, 1055–1065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shabani, M.; Ghoshehy, A.; Mottaghi, A.M.; Chegini, Z.; Kerami, A.; Shariati, A.; Taati Moghadam, M. The Relationship Between Gut Microbiome and Human Diseases: Mechanisms, Predisposing Factors and Potential Intervention. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2025, 15, 1516010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasqualette, L.; Fidalgo, T.K.D.S.; Freitas-Fernandes, L.B.; Souza, G.G.L.; Imbiriba, L.A.; Lobo, L.A.; Volchan, E.; Domingues, R.M.C.P.; Valente, A.P.; Miranda, K.R. Alterations in Vagal Tone Are Associated with Changes in the Gut Microbiota of Adults with Anxiety and Depression Symptoms: Analysis of Fecal Metabolite Profiles. Metabolites 2024, 14, 450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kurhaluk, N.; Lukash, O.; Tkaczenko, H. Do the Effects of Krebs Cycle Intermediates on Oxygen-Dependent Processes in Hypoxia Mediated by the Nitric Oxide System Have Reciprocal or Competitive Relationships? Cell. Physiol. Biochem. 2023, 57, 426–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kurhaluk, N.; Kamiński, P.; Lukash, O.; Tkaczenko, H. Nitric Oxide-Dependent Regulation of Oxygen-Related Processes in a Rat Model of Lead Neurotoxicity: Influence of the Hypoxia Resistance Factor. Cell. Physiol. Biochem. 2024, 58, 597–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tkaczenko, H.; Lukash, O.; Kamiński, P.; Kurhaluk, N. Elucidation of the Role of L-Arginine and Nω-Nitro-L-Arginine in the Treatment of Rats with Different Levels of Hypoxic Tolerance and Exposure to Lead Nitrate. Cell. Physiol. Biochem. 2024, 58, 336–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLaughlin, K.A.; Rith-Najarian, L.; Dirks, M.A.; Sheridan, M.A. Low Vagal Tone Magnifies the Association Between Psychosocial Stress Exposure and Internalizing Psychopathology in Adolescents. J. Clin. Child Adolesc. Psychol. 2015, 44, 314–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibbons, S.M.; Gurry, T.; Lampe, J.W.; Chakrabarti, A.; Dam, V.; Everard, A.; Goas, A.; Gross, G.; Kleerebezem, M.; Lane, J.; et al. Perspective: Leveraging the Gut Microbiota to Predict Personalized Responses to Dietary, Prebiotic, and Probiotic Interventions. Adv. Nutr. 2022, 13, 1450–1461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsuura, N.; Kanayama, M.; Watanabe, Y.; Yamada, H.; Lili, L.; Torii, A. Effect of Personalized Prebiotic and Probiotic Supplements on the Symptoms of Irritable Bowel Syndrome: An Open-Label, Single-Arm, Multicenter Clinical Trial. Nutrients 2024, 16, 3333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Peng, Y.; Shen, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, L.; Yang, X. Dietary polyphenols: Regulate the advanced glycation end products-RAGE axis and the microbiota-gut-brain axis to prevent neurodegenerative diseases. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2022, 63, 9816–9842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, A.; Mateus, N.; de Freitas, V. Polyphenol-Dietary Fiber Conjugates from Fruits and Vegetables: Nature and Biological Fate in a Food and Nutrition Perspective. Foods 2023, 12, 1052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Guo, X.; Jiang, K.; Shi, B.; Liu, L.; Hou, R.; Chen, G.; Farag, M.A.; Yan, N.; Liu, L. Dietary polyphenols regulate appetite mechanism via gut-brain axis and gut homeostasis. Food Chem. 2024, 446, 138739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, K.; Bai, Y.; Hou, R.; Chen, G.; Liu, L.; Ciftci, O.N.; Farag, M.A.; Liu, L. Advances in dietary polyphenols: Regulation of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) via bile acid metabolism and the gut-brain axis. Food Chem. 2025, 472, 142932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Study Models | Methods and Doses | Key Findings | Molecular Mechanisms | References | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Transgenic mice (Glp1r[GCamp6]) with abdominal window for in vivo imaging of Brunner’s glands | Cholecystokinin injection at 10 µg/kg; vagotomy and sensory denervation used to assess vagal role | Stress suppresses vagal activity → reduces Brunner’s gland secretion → alters microbiome (↓ Lactobacillus) | Stress inhibits central amygdala → lowers dorsal motor nucleus of the vagus activity → reduces parasympathetic output to duodenum → modifies the gut microbiota composition | [141] |

| 2 | Rats on high-fat diet (HFD) for 3 days or 4 weeks; induced metabolic disturbances resembling insulin resistance and hyperphagia model | Acetate infusion (2, 8, or 20 µmol/kg/min); metabolic assessments | Microbiota-derived acetate activates vagus nerve → ↑ insulin secretion, ↑ ghrelin, ↑ appetite → metabolic syndrome | Acetate stimulates parasympathetic signalling to β-cells → promotes hyperinsulinemia and obesity | [142] |

| 3 | Review of animal and human studies on the gut–microbiota–brain axis | Systematic literature review; no experimental interventions or dosing | Gut microbiota influences brain function through multiple systems including the autonomic nervous system, especially parasympathetic pathways | Parasympathetic signalling via the vagus nerve is one of five key routes linking the gut microbiota to the brain, along with neuroendocrine, immune, neurotransmitter, and barrier mechanisms | [143] |

| 4 | Human case–control study comparing fecal microbiota in 72 Parkinson’s disease patients and 72 healthy controls | 16S rRNA gene pyrosequencing (V1–V3 regions); statistical analysis using generalized linear models. No treatment or dosing applied | Parkinson’s disease patients had a 77.6% reduction in Prevotellaceae abundance. Decreased Prevotellaceae was associated with PD diagnosis, while Enterobacteriaceae abundance correlated with postural instability and gait difficulty | Altered gut microbiota may influence disease through interactions with the enteric nervous system and vagus nerve, both early targets of α-synuclein pathology in Parkinson’s disease | [2] |

| 5 | Mice with hepatocellular carcinoma; liver vagotomy, CD8+ T cell manipulation, microbiota transfer | Hepatic vagotomy; pharmacologic vagal activation; CD8+ T cell depletion; Chrm3 knockout; microbiota transplantation from HCC donors | Vagotomy → ↓ liver tumor growth, ↓ fatigue, ↓ anxiety. Vagal stimulation → ↑ tumor progression via immune suppression. Microbiota from HCC donors → impaired behavior and immunity | Vagal acetylcholine → CHRM3 receptor on CD8+ T cells → ↓ anti-tumor immunity. Gut microbiota + vagus nerve → regulate liver immune response and behavior | [6] |

| 6 | Mice lacking the α7 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor gene (Chrna7 knock-out), compared to wild-type mice. Subdiaphragmatic vagotomy was performed to investigate vagus nerve involvement | Subdiaphragmatic vagotomy; behavioral tests for depression; linear discriminant analysis effect size microbiota analysis; plasma metabolomics; synaptic protein analysis in medial prefrontal cortex | Chrna7 KO → ↑ depression-like behaviors, ↑ inflammation, ↓ synaptic proteins in mPFC. Subdiaphragmatic vagotomy → reversed depressive behavior and altered microbiota composition (↑ Lactobacillus spp.). | Chrna7 deletion → gut dysbiosis + systemic inflammation → affects brain via vagus nerve. Subdiaphragmatic vagotomy → modifies gut–brain communication → normalizes behavior and brain protein expression | [144] |

| 7 | Combined human gut microbiota data from 410 individuals with mild cognitive impairment or Alzheimer’s disease, and a rat model of memory impairment induced by pharmacological parasympathetic suppression | Scopolamine was injected in rats at a dose of 2 mg per kg of body weight to suppress parasympathetic nervous system activity over six weeks, combined with a high-fat diet. | Suppression of the parasympathetic nervous system → associated with altered gut microbiota in both humans and rats → increased abundance of Blautia, Escherichia, Clostridium, and Pseudomonas in memory-impaired groups → reduced Bacteroides and Bilophila | Parasympathetic inhibition via the vagus nerve → contributes to gut dysbiosis → affects cognition by disrupting gut–brain axis communication, potentially facilitating the progression from mild cognitive impairment to Alzheimer’s disease | [83] |

| 8 | Zebrafish fed omnivorous, herbivorous, or carnivorous diets; gnotobiotic larval zebrafish model used for microbiota intervention | Dietary intervention with specific feeding habits; administration of Cetobacterium somerae and acetate supplementation; glucose and insulin assessments | Omnivorous and herbivorous diets → ↑ glucose homeostasis, ↑ C. somerae abundance. C. somerae administration → ↑ insulin expression and improved glucose regulation. Acetate supplementation → mimicked these effects | C. somerae → ↑ acetate production → activates parasympathetic signaling → improves glucose homeostasis via a microbiota–brain–pancreas axis | [102] |

| 9 | Germ-free mice and conventional mice exposed to insulin-induced hypoglycemia to assess stress hormone responses | Induction of hypoglycemia using insulin; measurement of plasma and urine catecholamines; cecal short-chain fatty acid analysis; adrenal gene expression profiling | Absence of gut microbiota → ↓ baseline and stress-induced epinephrine levels, despite normal corticosterone and glucagon responses. Germ-free mice → delayed expression of adrenal stress-related genes | Lack of microbiota and short-chain fatty acids → impairs sympathoadrenal signaling → reduces epinephrine synthesis and release during stress | [62] |

| 10 | Young adult C57Bl6 male mice treated with antibiotics to deplete gut microbiota, with or without recolonization; tested for stress response to insulin-induced hypoglycemia | Broad-spectrum, non-absorbable antibiotics in drinking water for two weeks; insulin injection to induce hypoglycemia; SCFA supplementation; fecal microbiome profiling via shotgun sequencing | Antibiotic treatment → ↓ gut microbial diversity, ↓ short-chain fatty acids → ↓ baseline and stress-induced epinephrine. Recolonization restored microbiota but not epinephrine response. SCFA supplementation → partially restored stress-induced epinephrine release | Gut microbiome depletion → ↓ SCFA signaling → impairs sympathoadrenal epinephrine release, while parasympathetic and HPA axis responses remain intact | [63] |

| Disease/Models | Study Design and Conditions; Intervention/Dosage | Key Findings | Mechanisms/Microbiome–ANS interaction | References | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Major depressive disorder (MDD)/human (in vivo, clinical trial) | Randomized, placebo-controlled human clinical trial with 45 MDD patients over 4 weeks. Evaluations included HDRS-24, MADRS, BPRS, GSRS, and serum biomarkers (cortisol, TNF-α, IL-β) | Daily oral administration of Bifidobacterium breve CCFM1025 (1010 CFU) vs. maltodextrin placebo | CCFM1025 significantly improved depressive and gastrointestinal symptoms; it reduced serum serotonin turnover and modulated tryptophan metabolism; these changes were associated with increased alpha diversity and shifts in microbial composition, implicating gut microbiota–serotonin pathway interactions via the gut–brain axis | [207] |

| 2 | Major depressive disorder (MDD)/human (in vivo) and mouse (in vivo) | Combined human clinical trial + chronic stress-induced depressive mouse model. 16S rRNA microbiome analysis; clinical evaluation via HDRS, MADRS, BPRS, GSRS | 3-strain probiotic mix: B. breve CCFM1025, B. longum CCFM687, P. acidilactici CCFM6432 (freeze-dried, daily for 4 weeks) | Multi-strain probiotic reduced depression and GI symptoms more effectively than placebo in humans; confirmed psychotropic effects in mice. Serotonergic system modulation identified as the primary mechanism. Likely involvement of vagus nerve and microbial-derived metabolites | [208] |

| 3 | Functional gastrointestinal disorders with or without generalized anxiety disorder/human (in vivo) | Observational study (125 participants). Gut microbiota analyzed by 16S ribosomal RNA gene sequencing. Psychological traits measured using validated questionnaires (e.g., Hamilton Anxiety and Depression Scales, Toronto Alexithymia Scale) | No intervention | Patients with both conditions had higher levels of Clostridium. Haemophilus influenzae was elevated in those with gastrointestinal symptoms only. Microbiota patterns were linked to emotional and personality traits; increased Fusobacterium and Megamonas were associated with difficulty identifying or describing feelings, neurotic personality, and negative views of illness, suggesting a gut–brain interaction | [209] |

| 4 | Autism spectrum disorder/human (in vivo) | Non-randomized controlled study in children (30 with autism, 30 neurotypical). Gut microbiota assessed via metagenomic sequencing; serum metabolites analyzed by liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry | No intervention | Children with autism had lower microbial richness, altered microbiota (e.g., decreased Faecalibacterium prausnitzii, increased Veillonellaceae), and disrupted amino acid metabolism (low ornithine, high valine). Microbial shifts affected metabolic pathways such as galactose metabolism and the peptides/nickel transport system, potentially influencing brain function through altered gut–brain signalling | [4] |

| 5 | Autism spectrum disorder/human (in vivo, open-label clinical trial) | Open-label study of microbiota transfer therapy in children with autism. Plasma and fecal metabolite profiles were analyzed before and after treatment using mass spectrometry | Intensive fecal microbiota transplant (microbiota transfer therapy) | Children with autism showed altered plasma metabolites at baseline (low nicotinamide riboside, high caprylate); microbiota transfer therapy shifted plasma metabolite profiles closer to typically developing children; changes in microbiota influenced systemic metabolism, especially nicotinate and purine pathways. Lowering of p-cresol sulfate correlated with reduction in Desulfovibrio, supporting gut–brain metabolic interactions | [210] |

| 6 | Autism spectrum disorder/human (in vivo) | Shotgun metagenomic analysis before and after microbiota transfer therapy; 10-week and 2-year follow-up | Microbiota transfer therapy (fecal transplant) | Increased beneficial microbes (e.g., Prevotella, Bifidobacterium); improved microbial gene function; restoration of folate, sulfur, and oxidative stress pathways; lasting gut–brain effects | [211] |

| 7 | Alzheimer’s disease (early stage)/human (in vivo) | Randomized controlled trial, 51 participants with mild cognitive impairment or early dementia, 20-week duration | Intensive lifestyle changes: plant-based diet, exercise, stress reduction, social support | Improved memory and daily functioning; reduced cognitive decline; increased plasma beta-amyloid 42 to 40 ratio; lifestyle changes improved brain function and gut microbiota, suggesting modulation of the gut–brain axis and amyloid processing | [212] |

| 8 | Alzheimer’s disease risk (APOE genotype)/human and mouse (in vivo) | Comparative study using fecal microbiota sequencing and metabolomics in humans with different apolipoprotein E genotypes and in transgenic mice with human APOE genes | No intervention | Specific bacterial families (e.g., Prevotellaceae, Ruminococcaceae) and butyrate-producing genera varied by apolipoprotein E genotype; differences confirmed in mice; apolipoprotein E genotype influences gut microbial composition and metabolic output (e.g., short-chain fatty acids), suggesting a link between host genetics, gut microbiota, and neurodegenerative risk | [213] |