1. Introduction

Fluorescence fluctuation spectroscopy (FFS) [

1,

2,

3,

4] offers a powerful suite of tools, such as Number and Brightness (N&B) [

5,

6,

7,

8], Spatial Intensity Distribution Analysis (SpIDA) [

9,

10], and Fluorescence Intensity Fluctuation (FIF) [

11,

12,

13], to probe molecular interactions and protein oligomerization in living systems. These techniques rely on measurements of molecular brightness, defined as the average fluorescence intensity per diffusing fluorescent particle within a given excitation volume [

14,

15,

16,

17]. Molecular brightness scales linearly with the number of fluorophores in an oligomer, making it an attractive metric for quantifying protein oligomer size. For example, a homodimer tagged with one fluorophore per monomer is expected to produce a molecular brightness approximately twice that of a monomer under otherwise identical conditions.

While FFS-based methods offer several advantages, particularly for live-cell and dilute-solution measurements, they are part of a broader landscape of techniques used to study protein oligomerization. Solution-based methods such as size exclusion chromatography (SEC) [

18], analytical ultracentrifugation (AUC) [

19], and dynamic light scattering (DLS) [

20] provide estimates of hydrodynamic size and aggregation states but generally require high-concentration, purified samples and may lack the resolution to resolve closely spaced oligomeric states. Electrophoretic techniques like native polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE) [

21] offer qualitative insights into molecular weight but can introduce artifacts related to buffer or detergent conditions. In cellular environments, the organized smooth endoplasmic reticulum (OSER) assay [

22] infers self-association through morphological alterations in the endoplasmic reticulum but lacks stoichiometric precision. Methods such as SEC, AUC, DLS, PAGE, or OSER may be more practical for high-concentration purified samples or qualitative screening of self-association, whereas the intensity-based FFS approach is most advantageous when quantifying oligomeric state in live cells or low-concentration environments where molecular brightness readouts are already central to the experimental design. In this context, FFS techniques provide a complementary approach, offering high spatial and temporal resolution with quantitative insight into oligomerization under near-physiological conditions. When calibrated using monomeric controls, molecular brightness becomes a direct proxy for oligomer size: the ratio of observed brightness to a calibrated value of the monomeric molecular brightness, that is, the fluorescence output of a single, non-aggregated fluorophore under the same conditions, reveals the number of proteins comprising the complex, assuming one fluorophore per protein subunit [

11,

12,

23,

24,

25,

26].

The standard route to estimating monomeric brightness is via fluctuation analysis, where fluorescence intensity fluctuations, recorded from a dilute population of monomeric forms of the fluorescent label in solution or embedded within membranes, are used to compute molecular brightness per particle [

11,

27]. This method has the obvious advantage of being the same analytical framework applied to probe the oligomerization in biological samples of interest. However, this method is not immune to artifacts: even trace amounts of dimers or higher-order aggregates in a nominally monomeric preparation can elevate the apparent molecular brightness. Fluorescent proteins such as EGFP and Citrine are prone to self-association, even in their mostly “monomeric” forms [

28,

29] (e.g., mCitrine, the A206K mutant form of Citrine). This propensity for dimerization or higher-order oligomerization can result in an overestimated monomeric brightness value, leading to underestimation of oligomeric size in samples with unknown properties.

To address the limitations of fluctuation-based calibration of monomeric brightness, we explore an alternative approach: estimating monomeric molecular brightness,

, from solution-based measurements using the rather straightforward relation

, where

I represents the average fluorescence intensity,

C the fluorophore concentration (in molecules per volume), and

the effective observation volume from which the signal arises [

30], such that

has units of fluorescence intensity per molecule. In practice, this involves plotting fluorescence intensity as a function of fluorophore concentration and extracting the slope of the resulting line [

11,

31,

32]. If a value for

can be determined, molecular brightness

can be extracted directly by dividing the slope of the linear fit by

. However, under focused excitation, common to laser-scanning microscopes, this calculation is complicated by the Gaussian nature of the beam. Molecules experience varying excitation intensities depending on their position in the beam, and the boundaries of the excitation field are ill-defined [

14,

15]. To overcome these challenges, we adopt the concept of a virtual observation volume: a hypothetical region that, if uniformly illuminated at the beam’s peak intensity, would produce the same total fluorescence signal as the real, spatially varying excitation field [

14,

15,

30]. This construct allows us to apply the intensity–concentration–volume framework using a physically meaningful estimate of

. The underlying mathematical model is described in

Section 4.3.

In this study, we comparatively evaluate the average-intensity-based approach to estimating monomeric molecular brightness and the traditional intensity fluctuation-based method. We begin by empirically calibrating the effective excitation volume using sub-diffraction size fluorescent nanobeads. The observation volume, denoted

, provides a physical basis for connecting average intensity measurements to absolute molecular brightness, and serves as a conceptual bridge between fluctuation- and intensity-derived analyses. We then apply both methods to mCitrine under uninhibited aggregation conditions and show that the two approaches diverge significantly in their monomeric brightness estimates. Under highly controlled preparation conditions, which are labor-intensive and often better reserved for samples containing the biological system of interest, this discrepancy is significantly reduced but not eliminated, highlighting the underlying sensitivity of fluctuation-derived brightness to sample handling. Finally, we evaluate both methods using Janelia Fluor 525 (JF

525) conjugated to HaloTag [

33], a small-molecule labeling system expected to exhibit reduced aggregation compared with fluorescent proteins [

34,

35]. In this benchmark system, the two approaches yield closely matching brightness estimates, consistent with a truly monomeric population.

The results presented in this manuscript establish that the intensity-based determination of monomeric brightness, when paired with careful volume and concentration measurement, offers a robust and interpretable path to monomeric brightness estimation based on separate knowledge of the fluorophore concentration and the effective observation volume. Accurate measurement of both these quantities is straightforward in solution-phase experiments but may be difficult or impossible in spatially heterogeneous environments such as membranes or organelles. However, as we demonstrate, the commonly used fluctuation-based approach also exhibits strong concentration dependence in practice, particularly for fluorescent proteins prone to weak self-association. Even modest changes in sample concentration can elevate the apparent brightness due to transient or low-affinity oligomerization, leading to overestimates of the monomeric reference. Therefore, our findings support a multipronged strategy for brightness calibration.

In addition to addressing monomeric brightness calibration challenges in isolation, this work also contributes to a broader class of fluorescence techniques where accurate monomeric brightness measurements are essential. One such example is intensity fluctuation and resonance energy transfer (iFRET) [

36]. In iFRET, donor and acceptor intensity fluctuations within a small subregion in the sample are analyzed simultaneously alongside the mean donor and acceptor intensities (which allow computation of the FRET efficiency occurring between the two) within said region, to extract information about the size, spatial organization, and distribution of molecular complexes in living cells. By integrating the complementary information provided by variance- and mean-based readouts from the same dataset, iFRET reduces ambiguity and increases interpretive power.

A similar philosophy underlies the present calibration strategy: although average-intensity and fluctuation-based estimates of molecular brightness each have distinct strengths and limitations, their joint application provides cross-validating constraints that improve the robustness of both. In this light, it is fitting that the same principle of methodological complementarity not only enhances the accuracy of monomeric brightness calibration itself, but also directly benefits iFRET workflows. In particular, accurately calibrated intensity-based brightness enables more rigorous fluctuation analysis in iFRET, where assumptions about monomeric brightness critically influence derived complex sizes and populations. Thus, the methods developed here serve not only to benchmark fluorophore brightness, but also to enhance the precision and reliability of iFRET and other fluorescence fluctuation spectroscopy techniques.

2. Results

2.1. Estimating the Effective Excitation Volume Using Fluorescent Nanobeads

In this study, we used a custom-built two-photon microscope, described previously [

37,

38], which combines a pulsed Ti:Sapphire laser with a tunable center wavelength, a spatial light modulator that shapes the excitation beam into multiple focused spots, and an EMCCD camera for sensitive fluorescence detection. This setup enables simultaneous measurements at multiple locations, making it well-suited for high-throughput brightness analysis of proteins in solution.

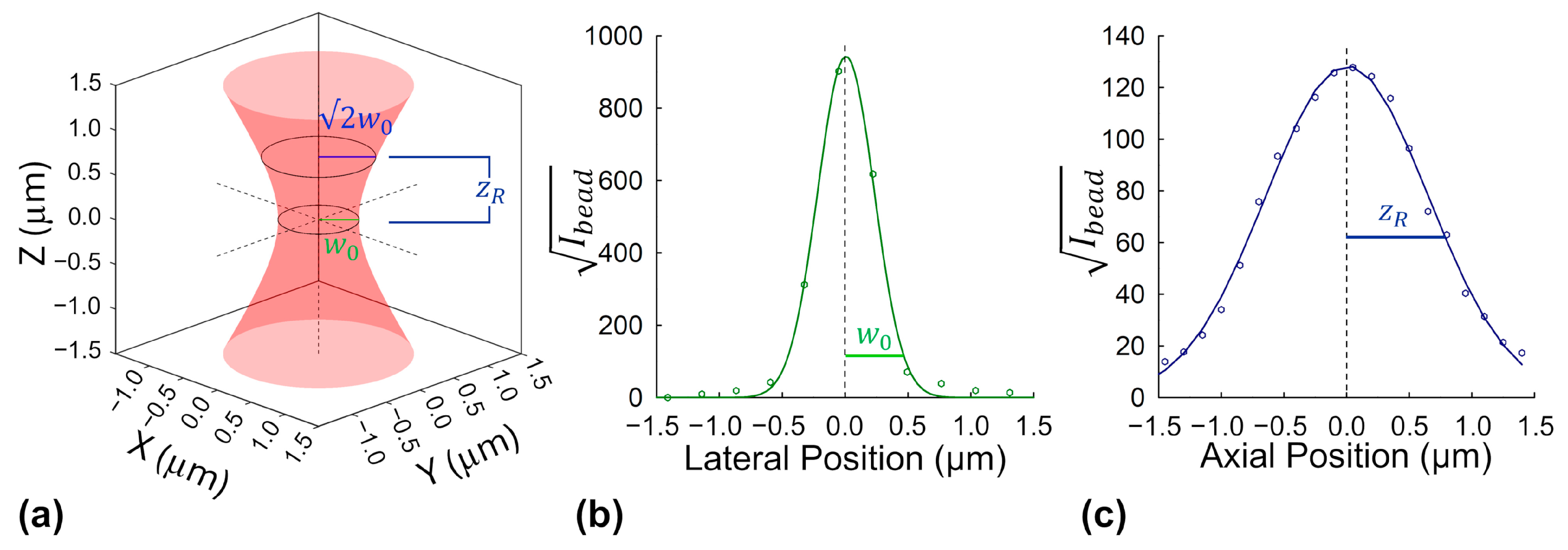

To determine the effective excitation volume required for intensity-based molecular brightness calculations, we used sub-diffraction fluorescent nanobeads embedded in a transparent hydrogel matrix (see

Section 4.1.1). These beads serve as point-like emitters that allow precise mapping of the microscope’s focal volume. By scanning the beads laterally and axially under excitation conditions matched to those used in protein measurements, we extracted key optical parameters of the beam: the lateral beam waist (

) and the axial Rayleigh length (

).

To map the beam’s lateral profile, we measured the fluorescence intensity across individual nanobeads in the focal plane. Because fluorescence from two-photon excitation depends on the square of the beam intensity, we analyzed the square root of the signal to better reflect the beam’s actual shape. The resulting profiles were fit to a Gaussian curve, and the beam width was characterized using the 1/e

2 radius, a standard measure of beam spread. A similar approach was used axially by scanning through the bead in small steps along the z-direction and fitting the vertical intensity profile. See

Section 4.2.2 for more details on this process.

The final averaged

and

parameters were used to calculate the effective excitation volume, as described in Equations (5)–(8). Although the measured Rayleigh range slightly exceeded (by ~20%) the theoretically predicted value for a diffraction-limited Gaussian beam with a width of

, the empirical value was used for all downstream volume calculations, yielding an effective excitation volume of

. This calibrated volume was subsequently used in all intensity-based monomeric molecular brightness estimations throughout the study. Representative bead profiles in both lateral and axial directions are shown in

Figure 1.

2.2. Framework for Comparing Fluctuation-Based and Intensity-Based Brightness Estimation

To assess the robustness and consistency of monomeric molecular brightness estimation across different experimental conditions, we employed a dual-analysis strategy that compares two approaches: (1) fluctuation-based analysis, which estimates brightness from temporal intensity fluctuations in fluorescence traces, and (2) intensity-based calibration, which derives brightness from the average fluorescence intensity, known fluorophore concentration, and a calibrated effective observation volume. This framework enables direct comparison between the traditional fluctuation-derived approach of determining monomeric brightness and the proposed average intensity-based method, particularly in systems where aggregation may distort fluctuation-derived estimates. The same data acquisition and analysis pipeline, described below, was applied to a variety of fluorophore samples under different preparation conditions, as detailed in subsequent sections.

Fluorescence measurements of fluorophore solutions were carried out using the custom two-photon microscope described in

Section 4.2.1. The excitation beam was patterned into a fixed 6 × 1 array, illuminating six distinct spots within the sample chamber simultaneously. With the beamlets held stationary during acquisition, 10,000 consecutive frames were captured at 100 µsec exposure time per frame, producing six independent fluorescence intensity traces—one for each beamlet. This process was repeated across multiple sample positions to improve statistical sampling. The resulting traces were then analyzed using both fluctuation- and intensity-based approaches to estimate the monomeric molecular brightness.

In the fluctuation-based approach, an effective molecular brightness value,

, was derived from each intensity trace based on the variance,

, and mean, ⟨

⟩, of the intensity distribution according to the following [

7,

11]:

Here

represents the variance due to detector noise (determined from calibration measurements [

11]), and γ is a geometric shape factor related to the laser point-spread function (PSF) and acquisition volume [

14]. The resulting

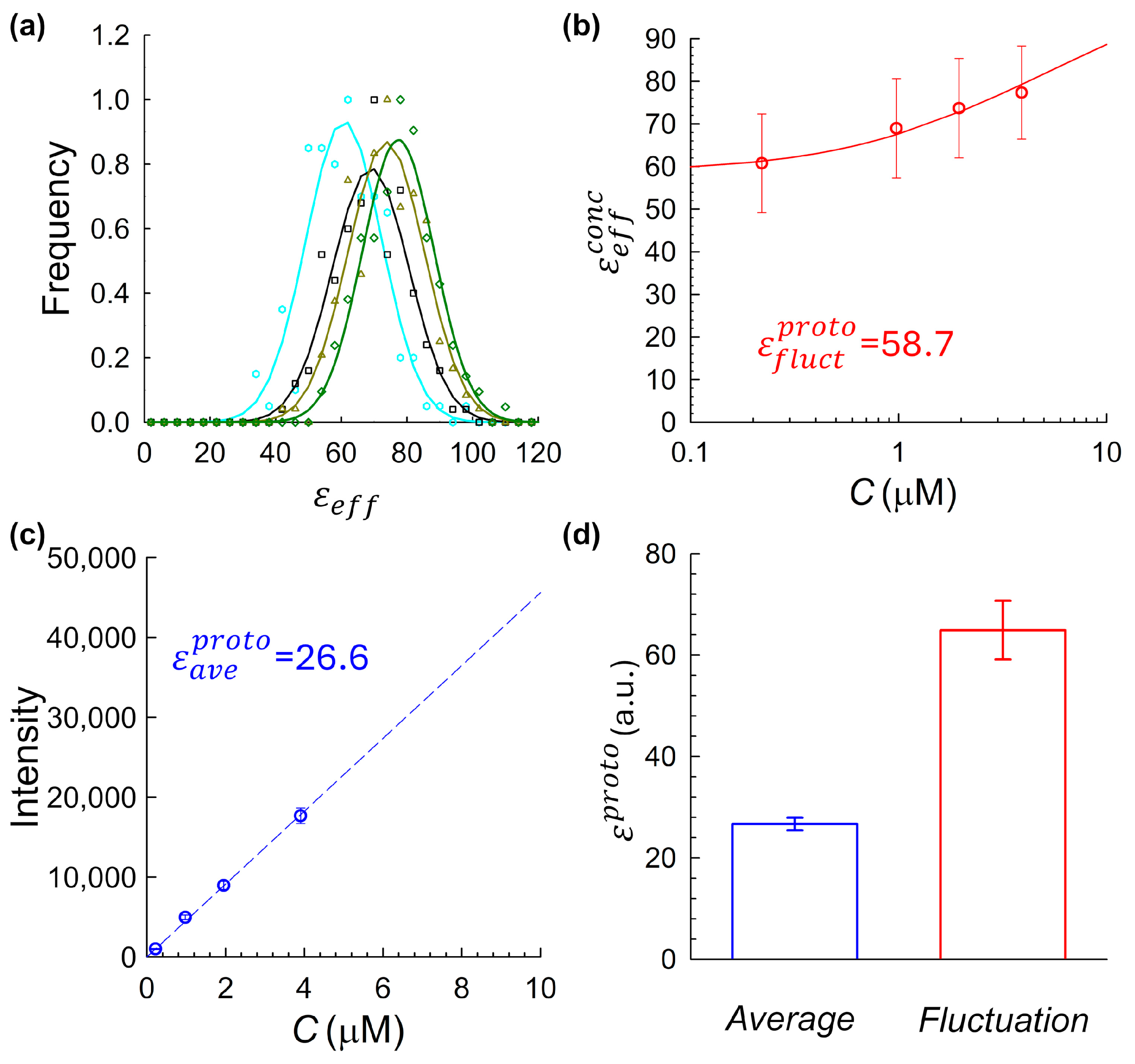

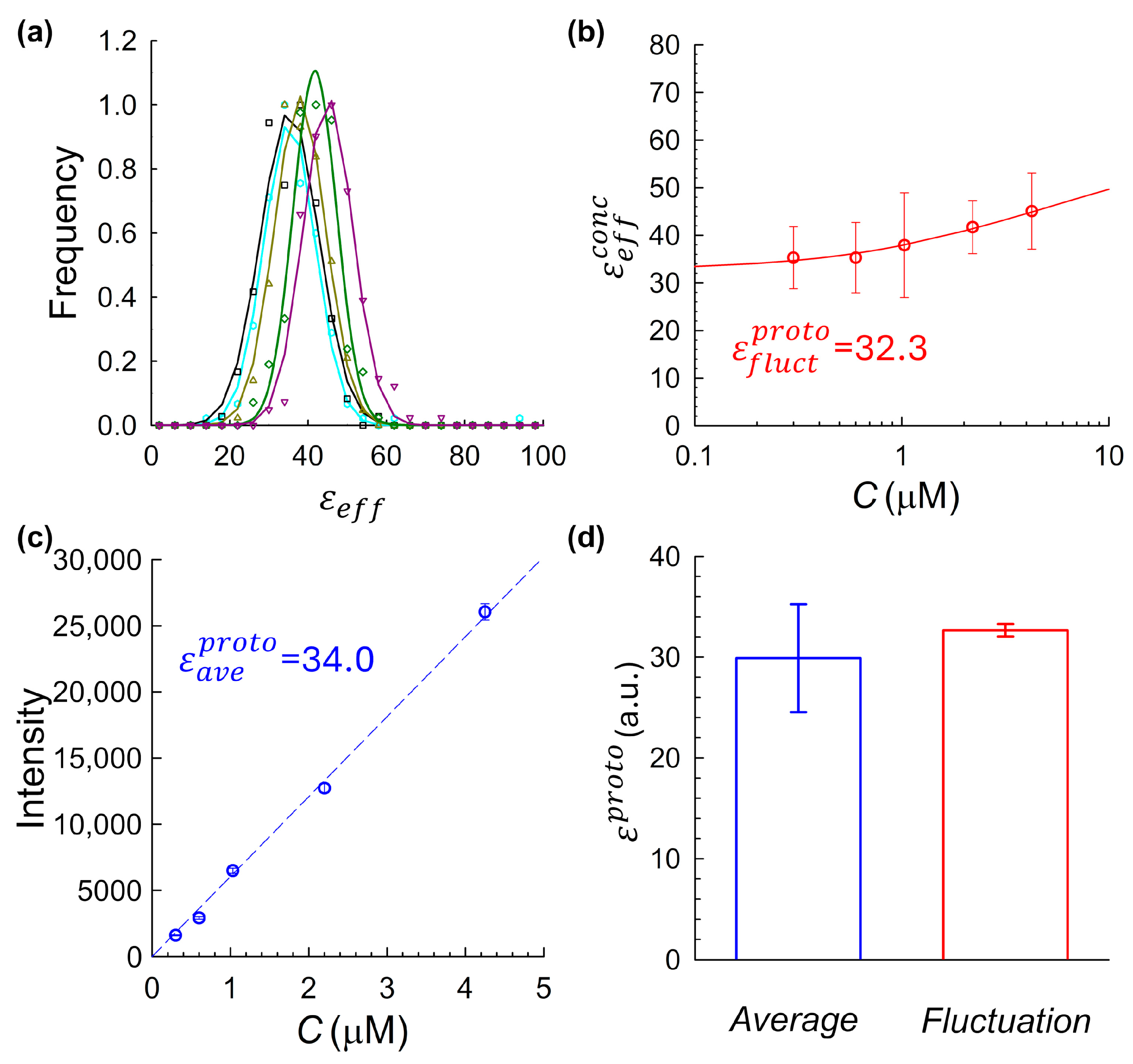

values from all traces at a given concentration were compiled into a histogram (

Figure 2a). These histograms were fit to Gaussian functions, and the mean of each fit, denoted as

, was used as the representative brightness value for the corresponding fluorophore concentration.

Figure 2b shows

, as a function of the measured fluorophore concentration. Fluorophore concentrations were independently verified by UV-Vis absorption spectroscopy. Across all tested samples, a consistent upward trend in brightness with increasing concentration was observed, indicating a degree of fluorophore self-association or aggregation, a pattern that varied in magnitude depending on the fluorophore and sample preparation conditions (as further detailed in

Section 2.3,

Section 2.4 and

Section 2.5 below). To quantify this effect and extrapolate the monomeric baseline brightness computed via the fluctuation approach,

, we fit the fluctuation-derived brightness data using a model based on the Law of Mass Action, assuming a simple monomer–dimer equilibrium [

11]. In this framework, the total effective brightness at a given fluorophore concentration C is expressed as

where

is the monomeric baseline brightness,

is the dissociation constant, and C is the total concentration of fluorophores of interest. This model was fitted to the experimental data using nonlinear regression, allowing both

and

to vary as free parameters. The fitted value of

provides the intrinsic monomeric brightness inferred from the fluctuation approach.

In the average intensity-based approach, we analyzed the same intensity traces described above using an average intensity vs. concentration method. For each fluorophore concentration, the mean fluorescence signal from every trace was computed and averaged across replicates at each concentration. The resulting plot of average signal versus concentration (

Figure 2c) was fitted with a linear regression., as shown in

Figure 2c [

31,

32]. The resulting slope of this fitted line,

, represents the detected fluorescence intensity per unit concentration (in digital units per µM). This value was then converted to monomeric molecular brightness computed via the intensity-based method,

, by dividing by the empirically measured observation volume:

where the calibrated volume

was derived from nanobead-based beam profiling (

Section 2.1).

To summarize the notation used throughout this work to describe molecular brightness estimates: we use ε to denote the molecular brightness of a fluorophore. The term refers to the effective brightness measured for a given sample, which could reflect a heterogeneous population of monomers, dimers, and higher-order species. Repeat measurements across different locations within the same sample yield a distribution of values; these are compiled into histograms and fit with Gaussians, and the resulting means are denoted , which represents the mean for a sample for a single concentration. In contrast, a superscript “proto” () indicates a reference monomeric brightness value, measured under conditions chosen to minimize self-association. Subscripts “fluct” () and “ave” () specify the method used to determine monomeric brightness, either via fluctuation-based analysis or average-intensity-based calibration, respectively.

To evaluate reproducibility and agreement between the two molecular brightness estimation strategies, this dual-analysis workflow was repeated across multiple independent experimental replicates. For each replicate, brightness was calculated both from fluorescence fluctuations and from the average intensity–based method described above. Subsequent sections explore how this comparison evolves across fluorescent proteins with varied aggregation tendencies. These include mCitrine under varying sample preparation conditions and JF525–HaloTag ligand as a minimally aggregating control. In each case, both brightness estimation methods were applied using the same data acquisition framework, enabling direct, quantitative comparison.

2.3. mCitrine Under Aggregation-Prone Conditions Reveals Divergence Between Brightness Methods

The first complete dual-method analysis was performed using an mCitrine sample that, unintentionally, omitted several of the handling steps later found to be important for reducing aggregation and isolating monomeric species (see

Section 4.1.2). Specifically, the sample was not flash-frozen, was not originally eluted into a dithiothreitol (DTT)-containing buffer, and although it was processed by fast protein liquid chromatography (FPLC), the collected fraction spanned a broad elution window that likely included higher-order species. This dataset was initially collected during early validation of the intensity-based brightness calibration procedure and was expected to represent a reliable monomeric control, as it used mCitrine containing the A206K monomerizing mutation. However, the sample was later found to be aggregation-prone, providing an unexpected yet illustrative test case for comparing the two analysis methods and demonstrating that protein aggregation could strongly distort fluctuation-based monomeric brightness estimates.

Using the fluorescence acquisition and analysis pipeline described in

Section 2.2, we computed monomeric molecular brightness values using both fluctuation- and -intensity-based methods. For the fluctuation approach, histograms of

values were generated for each concentration (

Figure 2a) and fit with Gaussian functions. The resulting fitted means,

, were plotted as a function of fluorophore concentration (

Figure 2b), revealing a clear upward trend across the tested range. This increase strongly suggests fluorophore self-association. Importantly, because

varies with concentration, no single concentration provides an unambiguous monomeric baseline, underscoring a fundamental challenge in using this approach alone. To estimate a true monomeric brightness value, we fit the data shown in

Figure 2b using a monomer–dimer equilibrium model based on the Law of Mass Action (Equation (2)), yielding a monomeric baseline of

. However, applying the average-intensity-based method to the same data yielded a markedly lower monomeric brightness value of

(

Figure 2c). To assess reproducibility, the full dual-method analysis was repeated across three independently prepared mCitrine samples, using the same aggregation-prone protocol. As shown in

Figure 2d, fluctuation-derived estimates of monomeric brightness were consistently higher than those obtained using the intensity-based method. This substantial discrepancy raised a central question: was one method failing, or were the two methods fundamentally sensitive to different aggregation-related artifacts?

To explore discrepancy between methods further, we subjected the same mCitrine preparation to FPLC fractionation and collected two narrow elution peaks corresponding to distinct apparent molecular sizes (

Supplementary Figure S1). Brightness measurements were then repeated on both fractions under matched concentration conditions. In the fluctuation-derived brightness, the earlier FPLC peak (corresponding to a larger-size) showed a markedly higher

value. In contrast, the average-intensity-derived brightness remained essentially unchanged across both fractions (see

Supplementary Figure S1). This result pointed to the presence of higher-order oligomers in the larger-size peak, which inflate fluctuation-derived brightness estimates due to their disproportionate signal contribution, yet contribute proportionally to total fluorescence intensity at fixed concentration.

These results provide initial evidence that aggregation can substantially distort fluctuation-based brightness estimation, whereas the average-intensity calibration approach remains comparatively stable, even in the presence of molecular heterogeneity. This contrast suggests that intensity-based methods, when paired with accurate concentration and volume calibration, may offer a more consistent path to monomeric brightness estimation in aggregation-prone systems. Notably, this holds true even for fluorescent proteins engineered with monomerization mutations (e.g., A206K), indicating that standard constructs alone may not be sufficient to eliminate self-association effects. In the following section, we test this hypothesis under more rigorously controlled preparation conditions using the same fluorophore.

2.4. mCitrine Under Controlled Preparation Conditions Yields Improved Agreement Between Brightness Methods

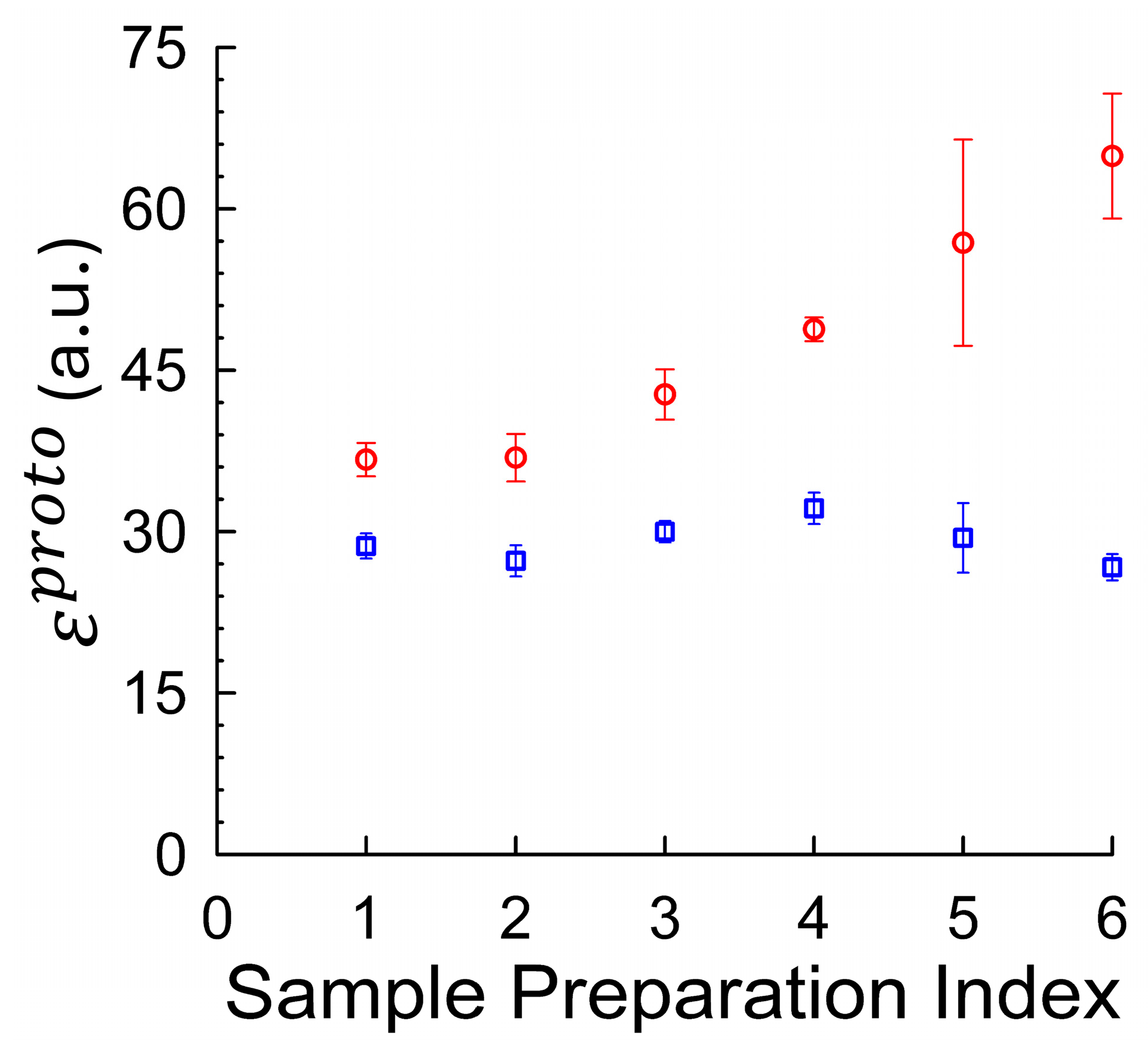

To systematically explore how sample handling influences the agreement between brightness estimation methods, we analyzed six distinct mCitrine preparation protocols, indexed 1–6 (See

Table 1). These protocols varied in key factors, such as FPLC elution buffer composition (±1 mM DTT), storage condition (fresh vs. flash-frozen), inclusion of 1% polyethylene glycol (PEG) as a cryoprotectant during freezing, and the extent of size-based fractionation via FPLC (

Supplementary Figure S1). 10 mM 4-(2-hydroxyethyl)-1-piperazineethanesulfonic acid (HEPES) at pH 7.2 was used as the standard buffer throughout to ensure stable, near-physiological pH throughout sample handling and measurement. DTT (1 mM) was included in some preparations to maintain reducing conditions and prevent disulfide-mediated aggregation. PEG (1%

w/

v) was added as a cryoprotectant in selected samples to reduce aggregation induced during flash freezing. For each indexed condition, monomeric molecular brightness was computed using both fluctuation-based (

) and average-intensity-based approaches (

).

Figure 3 summarizes the results across all six protocols. The fluctuation-derived brightness values (red circles) showed pronounced variability across conditions, ranging from 36.7 to 64.9 units per molecule. In contrast, the average-intensity-derived brightness (blue squares) remained relatively stable, with values clustered between 27 and 32 units. This divergence underscores the sensitivity of fluctuation analysis to even modest aggregation levels, while highlighting the comparative robustness of the intensity-based calibration method.

To further investigate conditions that yield the best agreement between brightness estimation methods, we examined the sample indexed by 2, which was eluted into 1 mM DTT during high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) purification and flash-frozen in the presence of 1% PEG (

w/

v) as a cryoprotectant to reduce oxidation and aggregation. To estimate the sensitivity of the fluctuation-based method to even minor handling artifacts, we compared these results to Index 3, which differed only in the omission of PEG during freezing. Despite identical buffer conditions, this small change produced a marked elevation in fluctuation-derived brightness, consistent with freezing-induced aggregation (see

Supplementary Figure S2).

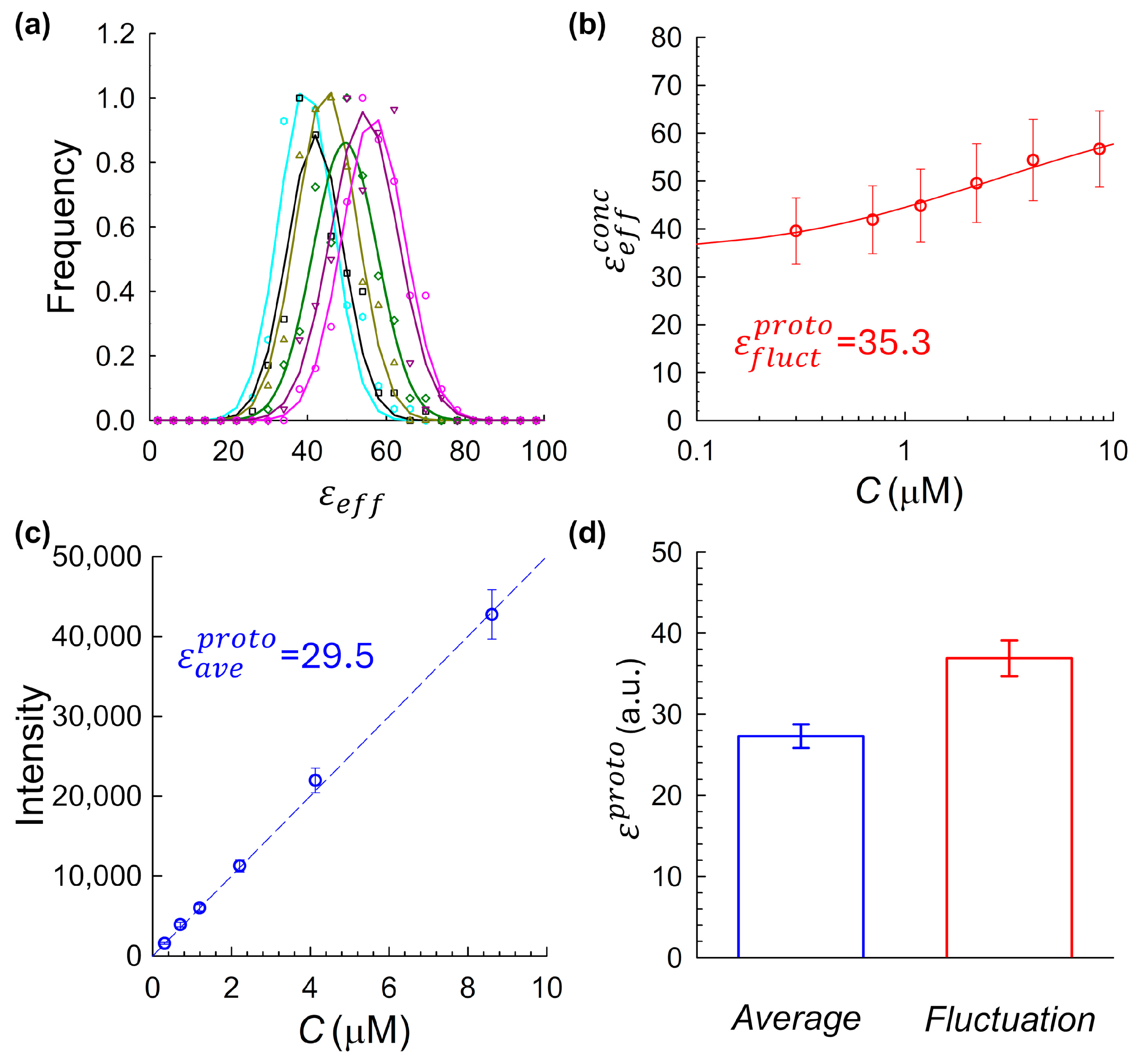

Under these more controlled conditions, five independent mCitrine preparations were each measured across a range of concentrations to enable full brightness calibration using both fluctuation-based and intensity-based approaches.

Figure 4 shows results from one of these five independent experiments, laid out using the same panel structure as in

Figure 2. Histograms of fluctuation-derived brightness values computed from intensity traces across a range of concentrations were fit by Gaussian functions to extract the mean brightness for each concentration sample (panel a). These values, plotted against concentration in panel b, revealed a clear upward trend, suggestive of weak concentration-dependent self-association, even under these controlled conditions. The slope of the intensity–concentration plot yielded a molecular brightness of 29.5. Panel d summarizes the results across all five replicates of samples prepared according to index 2, shown as a bar chart with means and standard deviations. On average, fluctuation-based analysis yielded an average value of

, which is significantly different than the value of

from the intensity-based method. Importantly, reproducibility of mCitrine brightness measurements required careful handling. Brightness estimates were only compiled from samples that were either (a) freshly purified and immediately measured (see

Section 4.1.2), or (b) flash-frozen in the presence of 1% PEG as a cryoprotectant to minimize aggregation.

Together, these findings show that while careful sample handling improves agreement between the two brightness estimation methods, a discrepancy still remains. This persistent gap underscores the need for further validation of the intensity-based calibration approach using an alternative fluorophore with minimal aggregation propensity, which is discussed next.

2.5. JF525–HaloTag Ligand as a Minimally Aggregating Benchmark System

To further compare the accuracy of the two molecular brightness-determination approaches, we used protein–fluorophore system that is theoretically less prone to aggregation: the Janelia Fluor 525 (JF

525)–HaloTag conjugate. HaloTag is widely used in quantitative fluorescence studies and, in multiple experimental contexts, has been shown to exhibit reduced self-association compared to aggregation-prone fluorescent proteins [

34,

35]. In these studies, both HaloTag and fluorescent proteins were fused to the same protein of interest, and the aggregation behavior of the fusion constructs was compared. HaloTag fusions preserved the dynamic or phase behavior of the target proteins more faithfully, suggesting a lower propensity for self-association in this context. However, direct, quantitative comparisons to mCitrine and related variants remain limited in the literature. It was for this reason that we conducted pKa-based electrostatic modeling using the Rosetta-pH algorithm to assess the aggregation propensity of the HaloTag conjugate under physiological pH conditions [

39,

40]. The Rosetta-pH modeling estimated a net charge of −33 for HaloTag at pH 7.2, expressed in units of elementary charge (e). This value reflects the total protonation state of all ionizable residues, as predicted from the protein structure and local environment at the specified pH. Notably, previous studies have shown that increased negative surface charge correlates strongly with improved protein solubility and reduced aggregation tendency [

41]. Therefore, the substantial negative charge obtained from Rosetta simulations supports our use of HaloTag as a minimally aggregating reference system. For comparison, we also performed Rosetta-pH modeling on Citrine, which yielded a net charge of −3e at pH 7.2. Although the structure lacked the A206K mutation present in our mCitrine construct, the large discrepancy in net electrostatic charge between the two proteins, HaloTag (−33e) vs. Citrine (−3e), supports the reduced aggregation propensity of HaloTag and its suitability as a solubility reference. Combined with JF

525, a bright, rhodamine dye developed by the Lavis Lab at Janelia Research Campus [

33], the system serves as a useful benchmark for evaluating brightness estimation methods where aggregation is expected to be minimal.

To experimentally evaluate the system, we applied both fluctuation-based and intensity-based brightness estimation methods to JF

525–HaloTag conjugates across a range of concentrations, as summarized in

Figure 5. The fluctuation-derived brightness showed only a modest concentration-dependent increase (

Figure 5b), consistent with weak self-association. Although smaller in magnitude than for mCitrine, this trend suggests a degree of residual aggregation at higher concentrations. These effects were measurable but minor, reinforcing the suitability of JF

525–HaloTag as a comparative benchmark system. The intensity-based method yielded a closely matching monomeric brightness estimate of (

Figure 5c). To evaluate the reproducibility of the agreement between the two molecular brightness estimation strategies, we repeated the dual analysis described above across four independent experimental replicates, each using freshly prepared JF

525–HaloTag samples. Across these replicates, the fluctuation-based method produced a mean brightness of

, while the average-intensity-based method yielded

(

Figure 5d). Although the results are in close agreement, a modest residual discrepancy persists, likely reflecting small variations in the intensity-based estimate, which is sensitive to factors such as fluorophore extinction coefficient in the measurement buffer, and pH mismatch between cuvette and imaging chambers. Still, the overall convergence strongly supports the average-intensity calibration method as a reliable route to determining molecular brightness, particularly when used in tandem with accurate concentration and volume characterization.

3. Discussion

Quantitative fluorescence fluctuation spectroscopy (FFS), including applications such as iFRET [

36] and SpiDA [

9,

10], relies heavily on accurate estimates of the monomeric molecular brightness to infer stoichiometry and oligomeric states of the proteins of interest [

42,

43]. However, the results presented here underscore the inherent difficulty of establishing reliable monomeric brightness standards using fluctuation-based approaches alone, particularly for fluorophores prone to self-association. Even constructs engineered to be monomeric, such as mCitrine with the A206K mutation, exhibited strong concentration-dependent brightness increases under standard experimental conditions. These artifacts can arise from transient interactions, low-level aggregation, or incomplete separation of oligomeric species during purification. A key challenge is that, in such cases, the inferred brightness of the “monomeric control” is not constant, but varies systematically with fluorophore concentration, compromising its utility as a baseline standard because the value extracted from calibration measurements depends on the concentration of the samples undergoing measurement.

This study highlights a complementary strategy for estimating monomeric molecular brightness based on measured fluorescence intensity, independently verified fluorophore concentration, and an empirically determined size for the observation volume. In multiple experimental contexts, this average-intensity method demonstrated greater stability than traditional fluctuation-based estimates, particularly in scenarios where self-association or sample heterogeneity introduced non-monomeric species. In the well-controlled JF525–HaloTag system, both methods yielded closely matching results, validating the method’s accuracy under aggregation-minimized conditions. In contrast, for more aggregation-prone systems such as mCitrine, the intensity-based method was less sensitive to sample handling variability and produced more consistent brightness estimates across replicates, even in preparations where the fluctuation-derived values were elevated. Thus, the divergence between the two methods by itself carries diagnostic value. A widening gap, especially when the intensity-based estimate remains stable, can signal oligomeric contamination or ongoing molecular interactions.

At first glance, the average-intensity-based approach may appear limited by its reliance on externally measured quantities: namely, fluorophore concentration and the effective observation volume. However, as this study demonstrates, the commonly used fluctuation-based approach is not exempt from similar dependencies to fluorophore concentration. Particularly for fluorescent proteins that exhibit weak or transient self-association, even small variations in concentration can produce substantial changes in apparent brightness, leading to inflated monomeric baselines. In such cases, the fluctuation-derived brightness baseline is itself concentration-dependent, undermining its role as a fixed calibration point. While accurate determination of concentration is relatively straightforward in well-controlled solution- experiments, such calibration is more difficult in spatially heterogeneous environments, such as membranes or cellular organelles [

44,

45]. Moreover, even when concentration is well characterized, extracting monomeric brightness from brightness-versus-concentration data requires assumptions about the underlying interaction model, for example, fitting to a simple monomer–dimer equilibrium may not capture systems with higher-order or multi-state associations, potentially confounding interpretation.

While more elaborate binding models might improve the fit to these datasets—incorporating factors such as multi-site interactions, higher-order oligomerization, or dark fluorophore fractions—to better fit the concentration-dependent brightness curves, such approaches introduce significant modeling complexity. In the case of mCitrine, variability across preparations suggests that distinct interaction mechanisms or aggregation pathways may be at play, making it difficult to apply a single reliable model. While such strategies may be appropriate for targeted mechanistic studies, the dimerization model is used in this work as a tool for determining the oligomer brightness by simple extrapolation of the theoretical fit to low concentrations of proteins. Rather than investing effort into explaining the behavior of a “monomeric control,” we show that a more stable, orthogonal calibration method frees researchers to focus their modeling on systems where the biology is meaningful, such as ligand-induced receptor oligomerization in membrane environments [

11,

12,

23,

46].

Despite its robustness, the intensity-based method relies on several important assumptions. First, it depends on accurate fluorophore concentration measurements, typically obtained via absorbance spectroscopy using extinction coefficients that may vary with buffer composition, pH, or labeling environment [

47,

48]. Second, fluorescence yield can be modulated by the local chemical environment, meaning that calibration performed in bulk solution may not accurately reflect intracellular behavior. Third, the method assumes linear excitation conditions, where fluorescence intensity scales proportionally with excitation power. As shown by Nagy, Wu, and Berland [

15,

30], this linearity holds in the low-power regime but breaks down at higher excitation intensities, where photon absorption approaches or exceeds the spontaneous emission rate. This leads to excitation saturation, distorting the PSF shape and invalidating volume models based on Gaussian optics. To avoid such artifacts, all experiments in this study were performed under carefully validated linear conditions. However, when applying the method to other systems, users should independently verify that excitation remains in the linear regime to ensure accurate quantification.

Finally, the intensity-based approach assumes a well-characterized and stable observation volume,

, derived from the squared point-spread function (PSF

2). In this study, the volume was estimated using nanobead-based 3D PSF profiling, constructed by stepping the objective in fixed axial increments (150 nm). However, in certain instances, the actual step size may deviate from the commanded value due to things such as mechanical backlash, thermal expansion, or positioning errors inherent to motorized systems. These deviations can distort the integrated PSF

2 profile and introduce systematic over- or underestimation of the observation volume, even within a single acquisition, particularly during z-stack sequences. While averaging across multiple beads helps reduce variability, it cannot fully correct for such systematic distortions. Future implementations could benefit from hardware-based axial stabilization, such as FREVR (Focus Readjustment for Enhanced Vertical Resolution) [

49], which uses interferometric feedback to maintain sub-nanometer z-positioning throughout acquisition.

It is also important to note that all measurements in this study were acquired on a custom-built two-photon micro-spectroscope, as described in

Section 4.2.1 and in previous work [

38]. The absolute excitation volume reported here is therefore instrument specific. Implementing the intensity-based calibration strategy on other microscopes will require analogous characterization of the point-spread function and observation volume on each platform, together with verification that excitation remains in the linear regime.

While the primary focus of this work was to establish a robust calibration strategy for monomeric molecular brightness, it has not escaped our attention that the slope-based method described here, when used in conjunction with fluctuation-derived brightness estimates, can be extended to determine equilibrium dissociation constants by analyzing changes in apparent oligomeric state across a range of concentrations, particularly under conditions where molecular interactions are preserved (KD). Extracting reliable KD values in this context requires a carefully controlled system with known labeling stoichiometry, non-perturbative measurement conditions, and constructs that retain reversible binding properties over a measurable concentration range. In our present manuscript we have pursued the opposite goal and therefore chose samples and experimental conditions that reduce oligomerization. However, we are actively pursuing this line of approach in a parallel study using mEGFP-derived dimers and higher-order oligomers to evaluate this combined strategy for benchmarking KD estimates under physiological and non-inhibitory conditions. These findings will be described in future publications.

The findings presented here underscore the need for rigorous, validated approaches to monomeric brightness calibration in FFS. While fluctuation-based analyses using “monomeric controls” are standard practice, such controls are vulnerable to low-level aggregation that can distort monomeric brightness estimates. This study demonstrates that calculating molecular brightness from average fluorescence intensity, known fluorophore concentration, and a carefully calibrated observation volume offers a reliable and complementary alternative, one that is less susceptible to aggregation artifacts and preparation variability. Neither method is universally robust in isolation: both carry assumptions and limitations. Instead, a dual-calibration strategy that leverages both approaches provides cross-validation, improves detection of aggregation-related distortions, and strengthens confidence in monomeric baselines. While JF525–HaloTag served as a validation system here, monomeric brightness calibration is ideally performed using the same fluorophore employed in the experiment, to capture condition-specific behavior. In aggregation-prone constructs such as mCitrine, the intensity-based method yielded more consistent brightness values across replicates, even when fluctuation-derived estimates were distorted by non-monomeric species. Used in tandem, intensity- and fluctuation-based approaches provide complementary insights, internal consistency checks, and enhanced confidence in interpreting molecular stoichiometry in complex biological systems.