ALKBH7 and NLRP3 Co-Expression: A Potential Prognostic and Immunometabolic Marker Set in Breast Cancer Subtypes

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Comparison of Clinicopathological Data in Patient Groups

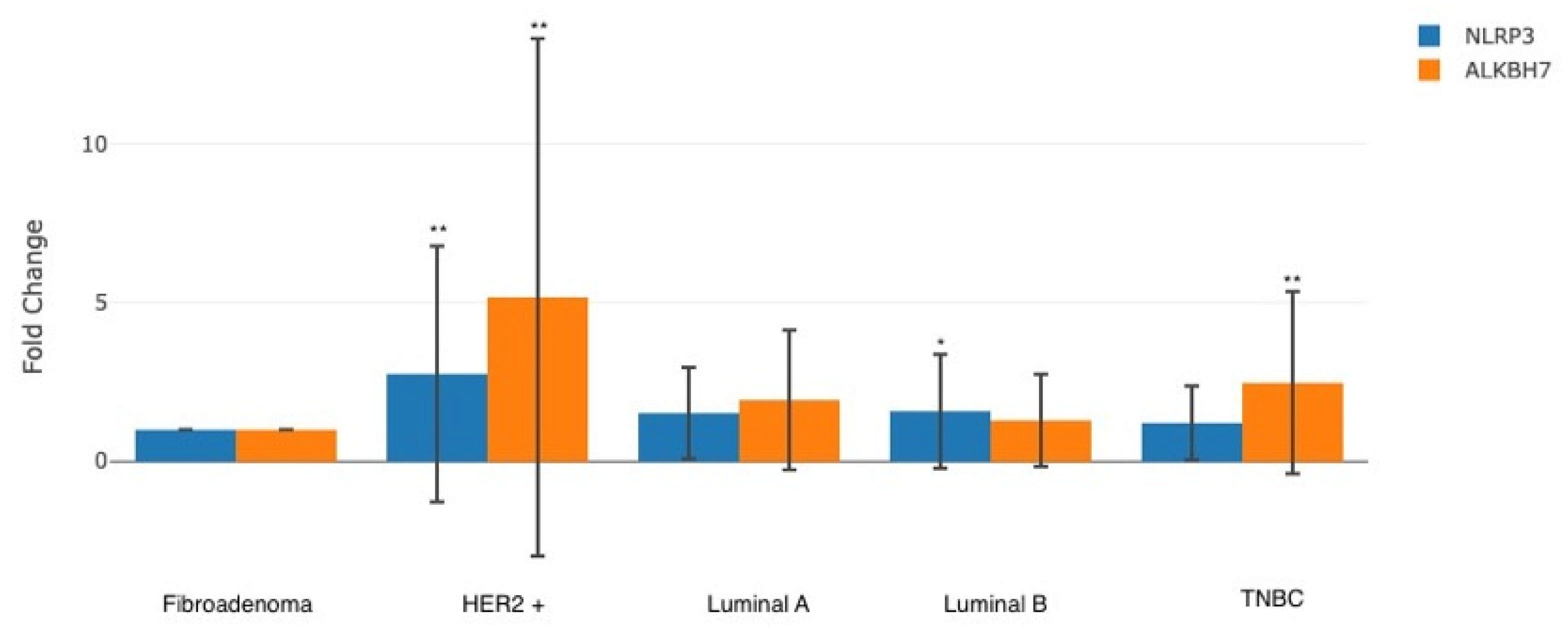

2.2. Comparison of Gene Expression Levels of Groups

2.3. Relationship Between Gene Expression and Clinical Data in Groups

2.4. Comparison of Gene Expression Correlation Between Groups

3. Discussion

Limitations and Future Directions

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Selection of the Study Group

4.2. RNA Extraction from Biopsy Tissue Samples

4.3. Gene Expression Analysis via Quantitative Real-Time PCR (qRT-PCR)

- ALKBH7: Sense:5′-GGAGCCAGATGTTGAGAG-3′Antisense: 5′-CTGAGGCTACAATTCCAGGTC-3′

- NLRP3: Sense: 5′-CAGCCTCATCAGAAAGAAGC-3′Antisense: 5′-GTGCTGCAGTTTCTCCAGG-3′

- GAPDH (reference gene): Sense: 5′-CTTCCTGAGCCTACTGCTGG-3′Antisense: 5′-AGTCGAAGTTGAGGCACTGG-3′

Ethical Statement

4.4. Statistical Analysis

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Swarbrick, A.; Fernandez-Martinez, A.; Perou, C.M. Gene-Expression Profiling to Decipher Breast Cancer Inter- and Intratumor Heterogeneity. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Med. 2024, 14, a041320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goldhirsch, A.; Winer, E.P.; Coates, A.S.; Gelber, R.D.; Piccart-Gebhart, M.; Thürlimann, B.; Senn, H.-J. Personalizing the treatment of women with early breast cancer: Highlights of the St Gallen International Expert Consensus on the Primary Therapy of Early Breast Cancer 2013. Ann. Oncol. 2013, 24, 2206–2223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yap, T.A.; Parkes, E.E.; Peng, W.; Moyers, J.T.; Curran, M.A.; Tawbi, H.A. Development of Immunotherapy Combination Strategies in Cancer. Cancer Discov. 2021, 11, 1368–1397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vanneman, M.; Dranoff, G. Combining immunotherapy and targeted therapies in cancer treatment. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2012, 12, 237–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, H.R.; Chlon, L.; Pharoah, P.D.; Markowetz, F.; Caldas, C. Patterns of Immune Infiltration in Breast Cancer and Their Clinical Implications: A Gene-Expression-Based Retrospective Study. PLoS Med. 2016, 13, e1002194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; Xu, J.; Zhong, Y.; He, S.; Hao, Z.; Zhang, B.; Liu, Z.; Zhou, X. Mammary hydroxylated oestrogen activates the NLRP3 inflammasome in tumor-associated macrophages to promote breast cancer progression and metastasis. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2024, 142 Pt A, 113034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voronov, E.; Shouval, D.S.; Krelin, Y.; Cagnano, E.; Benharroch, D.; Iwakura, Y.; Dinarello, C.A.; Apte, R.N. IL-1 is required for tumor invasiveness and angiogenesis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2003, 100, 2645–2650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shadab, A.; Mahjoor, M.; Abbasi-Kolli, M.; Afkhami, H.; Moeinian, P.; Safdarian, A.R. Divergent functions of NLRP3 inflammasomes in cancer: A review. Cell Commun. Signal. 2023, 21, 232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, X.; Zhu, Z.; Ding, L.; Du, W.; Pei, D. ALKBH4 impedes 5-FU Sensitivity through suppressing GSDME induced pyroptosis in gastric cancer. Cell Death Dis. 2024, 15, 435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sancar, A.; Lindsey-Boltz, L.A.; Unsal-Kaçmaz, K.; Linn, S. Molecular mechanisms of mammalian DNA repair and the DNA damage checkpoints. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2004, 73, 39–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, T.Q.; Ishak Gabra, M.B.; Lowman, X.H.; Yang, Y.; Reid, M.A.; Pan, M.; O’Connor, T.R.; Kong, M. Glutamine deficiency induces DNA alkylation damage and sensitizes cancer cells to alkylating agents through inhibition of ALKBH enzymes. PLoS Biol. 2017, 15, e2002810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fedeles, B.I.; Singh, V.; Delaney, J.C.; Li, D.; Essigmann, J.M. The AlkB Family of Fe(II)/α-Ketoglutarate-dependent Dioxygenases: Repairing Nucleic Acid Alkylation Damage and Beyond. J. Biol. Chem. 2015, 290, 20734–20742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, K.; Shen, D.; Tan, L.; Lai, D.; Han, Y.; Gu, Y.; Lu, C.; Gu, X. A Pan-Cancer Analysis Reveals the Prognostic and Immunotherapeutic Value of ALKBH7. Front. Genet. 2022, 13, 822261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, Z.; Li, C.; Kang, B.; Gao, G.; Li, C.; Zhang, Z. GEPIA: A web server for cancer and normal gene expression profiling and interactive analyses. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017, 45, W98–W102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borges, U.S.; Costa-Silva, D.R.; da Silva-Sampaio, J.P.; Escórcio-Dourado, C.S.; Conde, A.M., Jr.; Campelo, V.; Gebrim, L.H.; da Silva, B.B.; Lopes-Costa, P.V. A comparative study of Ki-67 antigen expression between luminal A and triple-negative subtypes of breast cancer. Med. Oncol. 2017, 34, 156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Wu, J.; Zhang, P.; Fei, X.; Zong, Y.; Chen, X.; Huang, O.; He, J.R.; Chen, W.; Li, Y.; et al. Prognostic and predictive value of Ki-67 in triple-negative breast cancer. Oncotarget 2016, 7, 31079–31087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, J.H.; Kim, D.H.; Surh, Y.J. Dynamic roles of inflammasomes in inflammatory tumor microenvironment. npj Precis. Oncol. 2021, 5, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Zhou, L.; Li, J.; Hu, K. ALKBH family members as novel biomarkers and prognostic factors in human breast cancer. Aging 2022, 14, 6579–6593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Chen, L.; Dang, W.Q.; Cao, M.F.; Xiao, J.F.; Lv, S.Q.; Jiang, W.J.; Yao, X.H.; Lu, H.M.; Miao, J.Y.; et al. CCL8 secreted by tumor-associated macrophages promotes invasion and stemness of glioblastoma cells via ERK1/2 signaling. Lab. Investig. 2020, 100, 619–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riabov, V.; Gudima, A.; Wang, N.; Mickley, A.; Orekhov, A.; Kzhyshkowska, J. Role of tumor associated macrophages in tumor angiogenesis and lymphangiogenesis. Front. Physiol. 2014, 5, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Lin, B.; Cai, B.; Cao, Z.; Liang, C.; Wu, S.; Xu, E.; Li, L.; Peng, H.; Liu, H. Integrative pan-cancer analysis reveals the prognostic and immunotherapeutic value of ALKBH7 in HNSC. Aging 2024, 16, 12781–12805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, Y.; Wang, Z.; Han, L.; Guo, Z.; Yan, B.; Guo, L.; Zhao, H.; Wei, M.; Hou, N.; Ye, J.; et al. PRMT5 regulates RNA m6A demethylation for doxorubicin sensitivity in breast cancer. Mol. Ther. 2022, 30, 2603–2617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aboelella, N.S.; Brandle, C.; Kim, T.; Ding, Z.C.; Zhou, G. Oxidative Stress in the Tumor Microenvironment and Its Relevance to Cancer Immunotherapy. Cancers 2021, 13, 986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, B.R.; Kanneganti, T.D. NLRP3 inflammasome in cancer and metabolic diseases. Nat. Immunol. 2021, 22, 550–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, X.; Yu, W.; Liu, J.; Tang, D.; Yang, L.; Chen, X. Oxidative cell death in cancer: Mechanisms and therapeutic opportunities. Cell Death Dis. 2024, 15, 556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, H.S.; Mbah, N.E.; Shan, M.; Loesel, K.; Lin, L.; Sajjakulnukit, P.; Correa, L.O.; Andren, A.; Lin, J.; Hayashi, A.; et al. OXPHOS promotes apoptotic resistance and cellular persistence in TH17 cells in the periphery and tumor microenvironment. Sci. Immunol. 2022, 7, eabm8182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, D.; Liwinski, T.; Elinav, E. Inflammasome activation and regulation: Toward a better understanding of complex mechanisms. Cell Discov. 2020, 6, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.; He, Q.; Feng, C.; Liu, Y.; Deng, Z.; Qi, X.; Wu, W.; Mei, P.; Chen, Z. The atomic resolution structure of human AlkB homolog 7 (ALKBH7), a key protein for programmed necrosis and fat metabolism. J. Biol. Chem. 2014, 289, 27924–27936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | Fibroadenoma (n = 33) | HER2+ (n = 34) | TNBC (n = 22) | Luminal A (n = 34) | Luminal B (n = 28) | F Test | p-Value | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean ± SD | Mean ± SD | Mean ± SD | Mean ± SD | Mean ± SD | |||||||||

| Age (years) | 43.9 ± 10.6 | 50.1 ± 6.9 | 42.6 ± 9.3 | 45.2 ± 8.1 | 47.8 ± 7.6 | 28.665 | <0.001 | ||||||

| Ki-67 | - | 40.5 ± 8.2 | 50.8 ± 7.5 | 15.3 ± 5.4 | 25.7 ± 6.1 | 26.620 | <0.001 | ||||||

| n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | χ2 test: | p-value | ||

| ER Status | Positive | 0 | 0.0 | 28 | 82.4 | 1 | 4.5 | 34 | 100 | 28 | 100 | 259.245 | p < 0.001 |

| Negative | 0 | 0.0 | 6 | 17.6 | 21 | 95.5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||

| PR Status | Positive | 0 | 0.0 | 28 | 82.4 | 11 | 50 | 34 | 100 | 27 | 96.4 | 189.099 | p < 0.001 |

| Negative | 0 | 0.0 | 6 | 17.6 | 11 | 50 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 3.6 | |||

| CerbB2 Status | Score 0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0 | 6 | 27.3 | 1 | 2.9 | 5 | 17.9 | 284.438 | p < 0.001 |

| Score 1 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 4.5 | 2 | 5.9 | 7 | 25.0 | |||

| Score 2 | 0 | 0.0 | 5 | 14.7 | 2 | 9.1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||

| Score 3 | 0 | 0.0 | 29 | 85.3 | 13 | 59.1 | 31 | 92.1 | 16 | 57.1 | |||

| Variable | Group | n | Mean | SD | F Test | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ALKBH7 mRNA | Fibroadenoma | 33 | - | - | 14.666 | <0.001 * |

| Luminal A | 34 | 0.9506 | 0.9007 | |||

| Luminal B | 28 | 0.3689 | 0.8536 | |||

| HER2+ | 34 | 2.3679 | 1.8120 | |||

| TNBC | 22 | 1.3024 | 0.9578 | |||

| NLRP3 mRNA | Fibroadenoma | 33 | - | - | 4.757 | 0.004 * |

| Luminal A | 34 | 0.6025 | 0.8091 | |||

| Luminal B | 28 | 0.6566 | 1.2108 | |||

| HER2+ | 34 | 1.4617 | 1.7943 | |||

| TNBC | 22 | 0.2789 | 0.8285 |

| Variable | Group | NLRP3 mRNA | |

|---|---|---|---|

| ALKBH7 mRNA | Luminal A | r | 0.346 |

| p | 0.045 * | ||

| Luminal B | r | 0.568 | |

| p | 0.002 * | ||

| HER2+ | r | 0.812 | |

| p | 0.001 * | ||

| TNBC | r | 0.454 | |

| p | 0.034 * |

| Group | ALKBH7 mRNA | NLRP3 mRNA | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | r | 0.031 | 0.243 |

| p | 0.710 | 0.003 * | |

| Ki-67 | r | −0.276 | 0.103 |

| p | 0.003 * | 0.275 | |

| ER Status | r | 0.690 | 0.648 |

| p | 0.040 * | 0.042 * | |

| PR Status | r | −0.967 | −0.785 |

| p | 0.004 * | 0.025 * | |

| CerbB2 Status | r | 0.182 | 0.068 |

| p | 0.049 * | 0.466 |

| ALKBH7 | NLRP3 | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Luminal A n = 34 | Luminal B n = 28 | HER2+ n = 34 | TNBC n = 22 | Luminal A n = 34 | Luminal B n = 28 | HER2+ n = 34 | TNBC n = 22 | ||

| Age | r | 0.483 | 0.418 | 0.371 | 0.210 | 0.517 | −0.470 | 0.434 | 0.223 |

| p | 0.000 ** | 0.002 ** | 0.006 * | 0.011 * | 0.000 ** | 0.002 * | 0.003 * | 0.010 * | |

| Ki-67 | rs | 0.560 | 0.511 | −0.457 | −0.313 | 0.644 | 0.559 | −0.448 | 0.269 |

| p | 0.000 ** | 0.000 ** | 0.003 * | 0.006 * | 0.000 ** | 0.000 ** | 0.003 * | 0.016 * | |

| ER Status | r | 0.664 | 0.587 | −0.663 | 0.508 | −0.653 | 0.565 | −0.659 | 0.442 |

| p | 0.000 ** | 0.000 ** | 0.000 ** | 0.000 ** | 0.000 ** | 0.000 ** | 0.000 ** | 0.003 * | |

| PR Status | r | 0.754 | 0.668 | −0.771 | 0.575 | 0.661 | 0.646 | 0.754 | 0.571 |

| p | 0.000 ** | 0.000 ** | 0.000 ** | 0.000 ** | 0.000 ** | 0.000 ** | 0.000 ** | 0.000 ** | |

| CerbB2 Status | r | 0.702 | 0.542 | 0.348 | 0.461 | −0.596 | −0.305 | 0.336 | 0.264 |

| p | 0.000 ** | 0.000 ** | 0.006 * | 0.003 * | 0.000 ** | 0.007 * | 0.006 * | 0.014 * | |

| ALKBH7 | NLRP3 | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Luminal A n = 34 | Luminal B n = 28 | HER2+ n = 34 | TNBC n = 22 | Luminal A n = 34 | Luminal B n = 28 | HER2+ n = 34 | TNBC n = 22 | ||

| Age | r | −0.181 | 0.205 | −0.269 | −0.267 | −0.014 | −0.070 | −0.274 | −0.205 |

| p | 0.305 | 0.296 | 0.124 | 0.229 | 0.937 | 0.725 | 0.117 | 0.361 | |

| Ki-67 | rs | −0.136 | 0.855 | −0.109 | −0.027 | 0.079 | 0.361 | −0.039 | 0.188 |

| p | 0.442 | 0.037 | 0.539 | 0.911 | 0.656 | 0.064 | 0.829 | 0.428 | |

| ER Status | r | 0.135 | 0.071 | −0.069 | 0.031 | −0.207 | 0.065 | 0.882 | 0.263 |

| p | 0.158 | 0.118 | 0.696 | 0.891 | 0.027 | 0.489 | 0.014 | 0.237 | |

| PR Status | r | 0.108 | 0.046 | −0.069 | 0.054 | 0.123 | 0.166 | 0.068 | 0.373 |

| p | 0.245 | 0.815 | 0.696 | 0.812 | 0.186 | 0.399 | 0.703 | 0.087 | |

| CerbB2 Status | r | 0.053 | −0.255 | 0.172 | 0.057 | −0.059 | −0.300 | 0.016 | 0.154 |

| p | 0.767 | 0.191 | 0.330 | 0.799 | 0.739 | 0.121 | 0.929 | 0.493 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Senturk, A.; Kazan, N.; Sen, S.; Cakar, G.C.; Sert, L.T.; Mutlu, F.; Taydas, O.; Mantoglu, B.; Gunduz, Y.; Ercan, M.; et al. ALKBH7 and NLRP3 Co-Expression: A Potential Prognostic and Immunometabolic Marker Set in Breast Cancer Subtypes. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 11661. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311661

Senturk A, Kazan N, Sen S, Cakar GC, Sert LT, Mutlu F, Taydas O, Mantoglu B, Gunduz Y, Ercan M, et al. ALKBH7 and NLRP3 Co-Expression: A Potential Prognostic and Immunometabolic Marker Set in Breast Cancer Subtypes. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2025; 26(23):11661. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311661

Chicago/Turabian StyleSenturk, Adem, Nur Kazan, Selen Sen, Gozde Cakirsoy Cakar, Lacin Tatliadim Sert, Fuldem Mutlu, Onur Taydas, Barıs Mantoglu, Yasemin Gunduz, Metin Ercan, and et al. 2025. "ALKBH7 and NLRP3 Co-Expression: A Potential Prognostic and Immunometabolic Marker Set in Breast Cancer Subtypes" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 26, no. 23: 11661. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311661

APA StyleSenturk, A., Kazan, N., Sen, S., Cakar, G. C., Sert, L. T., Mutlu, F., Taydas, O., Mantoglu, B., Gunduz, Y., Ercan, M., Bayhan, Z., Yildirim, E., & Uzun, H. (2025). ALKBH7 and NLRP3 Co-Expression: A Potential Prognostic and Immunometabolic Marker Set in Breast Cancer Subtypes. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 26(23), 11661. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311661