Gene Polymorphisms Determining Sex Hormone-Binding Globulin Levels and Endometriosis Risk

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Forecasted Functionality of Endometriosis-Associated Polymorphisms

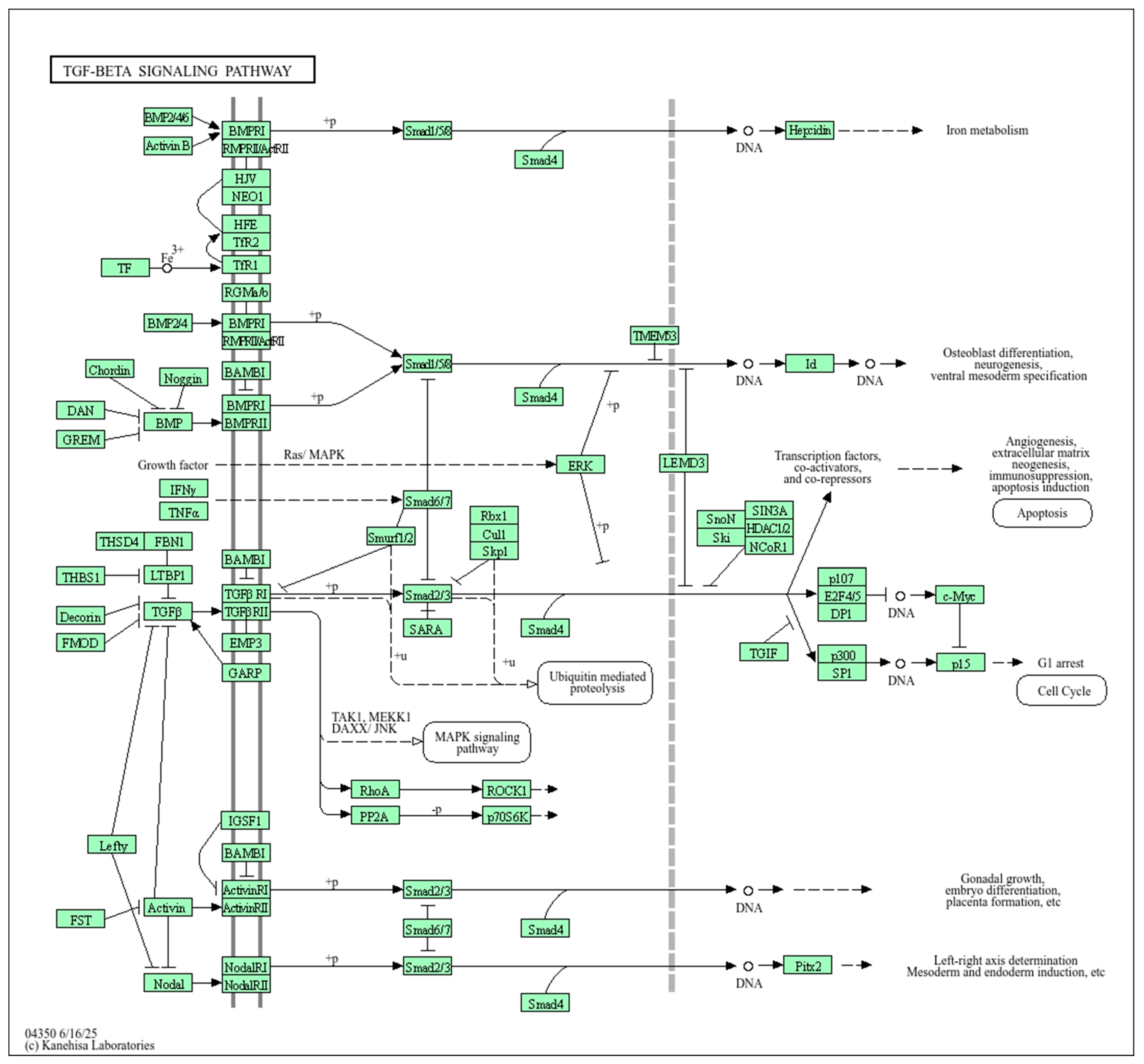

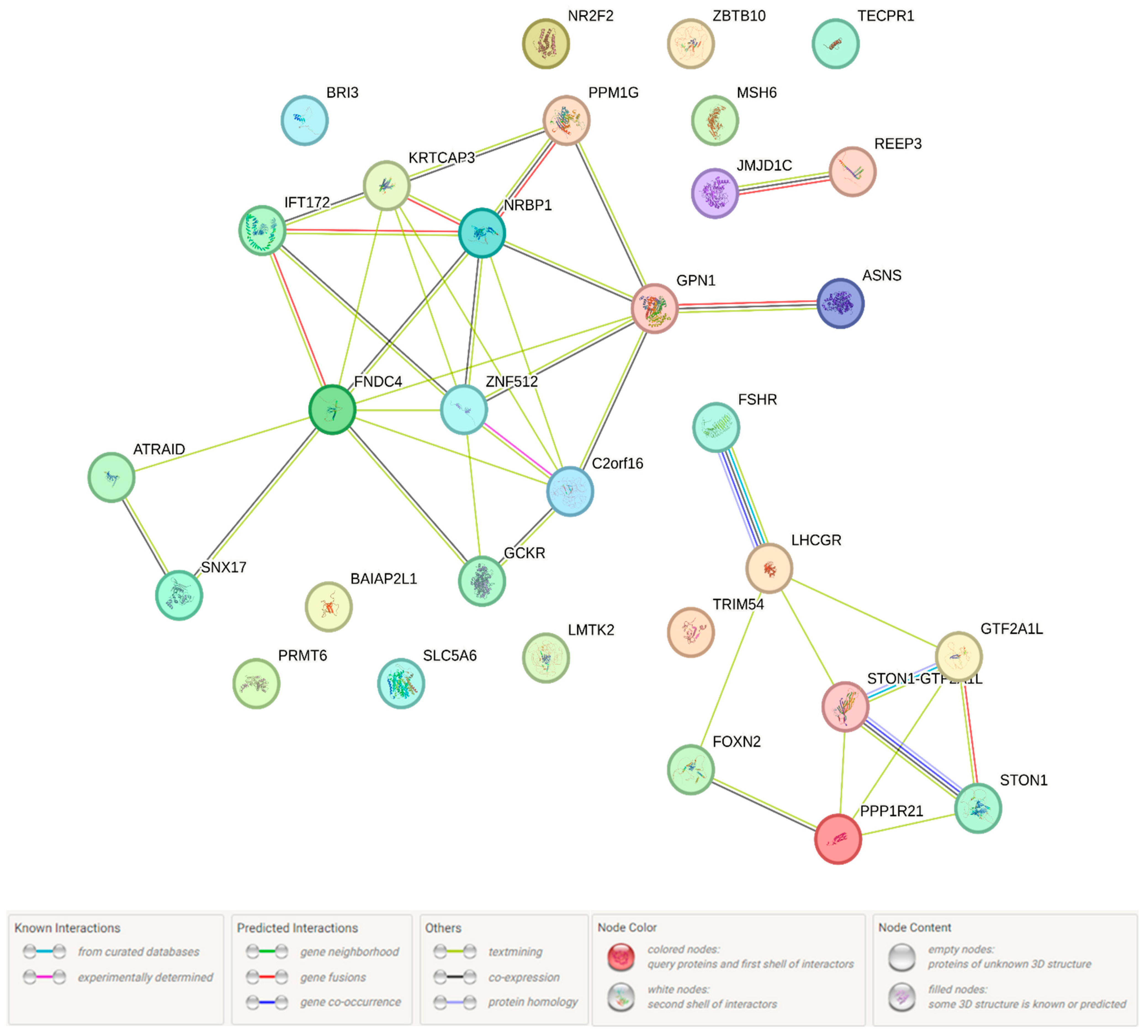

2.1.1. Functional Annotation of the Endometriosis-Causal SNP rs440837 (A > G) ZBTB10

2.1.2. Functional Annotation of the Endometriosis-Associated Variants

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Study Subjects

4.2. Experimental Analysis of the DNA (Selection and Genotyping of SNP)

4.3. Statistical Analysis of Experimental Genetic Data (SNP and Multi-SNPs Association Analysis)

4.4. Analysis of Forecasted Functionality at Endometriosis-Associated Polymorphisms (In Silico Study)

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| SHBG | Sex hormone-binding globulin |

| SHBGlevel | Sex hormone-binding globulin level |

| SNP | Single-nucleotide polymorphism |

| GWAS | Genome-wide association studies |

| BMI | Body mass index |

| DNA | Deoxyribonucleic acid |

| LD | Linkage disequilibrium |

| TFs | Transcription factors |

References

- Zondervan, K.T.; Becker, C.M.; Missmer, S.A. Endometriosis. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 382, 1244–1256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taylor, H.S.; Kotlyar, A.M.; Flores, V.A. Endometriosis is a chronic systemic disease: Clinical challenges and novel innovations. Lancet 2021, 397, 839–852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cano-Herrera, G.; Salmun Nehmad, S.; Ruiz de Chávez Gascón, J.; Méndez Vionet, A.; van Tienhoven, X.A.; Osorio Martínez, M.F.; Muleiro Alvarez, M.; Vasco Rivero, M.X.; López Torres, M.F.; Barroso Valverde, M.J.; et al. Endometriosis: A Comprehensive Analysis of the Pathophysiology, Treatment, and Nutritional Aspects, and Its Repercussions on the Quality of Life of Patients. Biomedicines 2024, 12, 1476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nnoaham, K.E.; Hummelshoj, L.; Webster, P.; d’Hooghe, T.; de Cicco Nardone, F.; de Cicco Nardone, C.; Jenkinson, C.; Kennedy, S.H.; Zondervan, K.T.; World Endometriosis Research Foundation Global Study of Women’s Health Consortium. Impact of endometriosis on quality of life and work productivity: A multicenter study across ten countries. Fertil. Steril. 2011, 96, 366–373.e8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smolarz, B.; Szyłło, K.; Romanowicz, H. Endometriosis: Epidemiology, classification, pathogenesis, treatment and genetics (Review of literature). Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 10554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simoens, S.; Dunselman, G.; Dirksen, C.; Hummelshoj, L.; Bokor, A.; Brandes, I.; Brodszky, V.; Canis, M.; Colombo, G.L.; DeLeire, T.; et al. The burden of endometriosis: Costs and quality of life of women with endometriosis and treated in referral centres. Hum. Reprod. 2012, 27, 1292–1299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saha, R.; Pettersson, H.J.; Svedberg, P.; Olovsson, M.; Bergqvist, A.; Marions, L.; Tornvall, P.; Kuja-Halkola, R. Heritability of endometriosis. Fertil. Steril. 2015, 104, 947–952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Treloar, S.A.; O’Connor, D.T.; O’Connor, V.M.; Martin, N.G. Genetic influences on endometriosis in an Australian twin sample. Fertil. Steril. 1999, 71, 701–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, S.H.; Harold, D.; Nyholt, D.R.; ANZGene Consortium; International Endogene Consortium; Genetic and Environmental Risk for Alzheimer’s disease Consortium; Goddard, M.E.; Zondervan, K.T.; Williams, J.; Montgomery, G.W.; et al. Estimation and partitioning of polygenic variation captured by common SNPs for Alzheimer’s disease, multiple sclerosis and endometriosis. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2012, 4, 832–841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adachi, S.; Tajima, A.; Quan, J.; Haino, K.; Yoshihara, K.; Masuzaki, H.; Katabuchi, H.; Ikuma, K.; Suginami, H.; Nishida, N.; et al. Meta-analysis of genome-wide association scans for genetic susceptibility to endometriosis in Japanese population. J. Hum. Genet. 2010, 55, 816–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uno, S.; Zembutsu, H.; Hirasawa, A.; Takahashi, A.; Kubo, M.; Akahane, T.; Aoki, D.; Kamatani, N.; Hirata, K.; Nakamura, Y. A genome-wide association study identifies genetic variants in the CDKN2BAS locus associated with endometriosis in Japanese. Nat. Genet. 2010, 42, 707–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Painter, J.N.; Anderson, C.A.; Nyholt, D.R.; Macgregor, S.; Lin, J.; Lee, S.H.; Lambert, A.; Zhao, Z.Z.; Roseman, F.; Guo, Q.; et al. Genome-wide association study identifies a locus at 7p15.2 associated with endometriosis. Nat. Genet. 2011, 43, 51–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nyholt, D.R.; Low, S.K.; Anderson, C.A.; Painter, J.N.; Uno, S.; Morris, A.P.; MacGregor, S.; Gordon, S.D.; Henders, A.K.; Martin, N.G.; et al. Genome-wide association meta-analysis identifies new endometriosis risk loci. Nat. Genet. 2012, 44, 1355–1359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albertsen, H.M.; Chettier, R.; Farrington, P.; Ward, K. Genome-wide association study link novel loci to endometriosis. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e58257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borghese, B.; Tost, J.; de Surville, M.; Busato, F.; Letourneur, F.; Mondon, F.; Vaiman, D.; Chapron, C. Identification of susceptibility genes for peritoneal, ovarian, and deep infiltrating endometriosis using a pooled sample-based genome-wide association study. Biomed. Res. Int. 2015, 2015, 461024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sapkota, Y.; Steinthorsdottir, V.; Morris, A.P.; Fassbender, A.; Rahmioglu, N.; De Vivo, I.; Buring, J.E.; Zhang, F.; Edwards, T.L.; Jones, S.O.D.; et al. Meta-analysis identifies five novel loci associated with endometriosis highlighting key genes involved in hormone metabolism. Nat. Commun. 2017, 8, 15539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sobalska-Kwapis, M.; Smolarz, B.; Słomka, M.; Szaflik, T.; Kępka, E.; Kulig, B.; Siewierska-Górska, A.; Polak, G.; Romanowicz, H.; Strapagiel, D.; et al. New variants near RHOJ and C2, HLA-DRA region and susceptibility to endometriosis in the Polish population-The genome-wide association study. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 2017, 217, 106–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Li, Y.; Li, S.; Wu, Z.; Yuan, M.; Wang, T.; Wang, S. Pooling-Based Genome-Wide Association Study Identifies Risk Loci in the Pathogenesis of Ovarian Endometrioma in Chinese Han Women. Reprod. Sci. 2017, 24, 400–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uimari, O.; Rahmioglu, N.; Nyholt, D.R.; Vincent, K.; Missmer, S.A.; Becker, C.; Morris, A.P.; Montgomery, G.W.; Zondervan, K.T. Genome-wide genetic analyses highlight mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) signaling in the pathogenesis of endometriosis. Hum. Reprod. 2017, 32, 780–793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Painter, J.N.; O’Mara, T.A.; Morris, A.P.; Cheng, T.H.T.; Gorman, M.; Martin, L.; Hodson, S.; Jones, A.; Martin, N.G.; Gordon, S.; et al. Genetic overlap between endometriosis and endometrial cancer: Evidence from cross-disease genetic correlation and GWAS meta-analyses. Cancer Med. 2018, 7, 1978–1987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, W.; Nielsen, J.B.; Fritsche, L.G.; Dey, R.; Gabrielsen, M.E.; Wolford, B.N.; LeFaive, J.; VandeHaar, P.; Gagliano, S.A.; Gifford, A.; et al. Efficiently controlling for case-control imbalance and sample relatedness in large-scale genetic association studies. Nat. Genet. 2018, 50, 1335–1341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishigaki, K.; Akiyama, M.; Kanai, M.; Takahashi, A.; Kawakami, E.; Sugishita, H.; Sakaue, S.; Matoba, N.; Low, S.K.; Okada, Y.; et al. Large-scale genome-wide association study in a Japanese population identifies novel susceptibility loci across different diseases. Nat. Genet. 2020, 52, 669–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Masuda, T.; Low, S.K.; Akiyama, M.; Hirata, M.; Ueda, Y.; Matsuda, K.; Kimura, T.; Murakami, Y.; Kubo, M.; Kamatani, Y.; et al. GWAS of five gynecologic diseases and cross-trait analysis in Japanese. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 2020, 28, 95–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adewuyi, E.O.; Mehta, D.; Sapkota, Y.; International Endogene Consortium; 23andMe Research Team; Auta, A.; Yoshihara, K.; Nyegaard, M.; Griffiths, L.R.; Montgomery, G.W.; et al. Genetic analysis of endometriosis and depression identifies shared loci and implicates causal links with gastric mucosa abnormality. Hum. Genet. 2021, 140, 529–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Backman, J.D.; Li, A.H.; Marcketta, A.; Sun, D.; Mbatchou, J.; Kessler, M.D.; Benner, C.; Liu, D.; Locke, A.E.; Balasubramanian, S.; et al. Exome sequencing and analysis of 454,787 UK Biobank participants. Nature 2021, 599, 628–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chou, Y.C.; Chen, M.J.; Chen, P.H.; Chang, C.W.; Yu, M.H.; Chen, Y.J.; Tsai, E.M.; Tsai, S.F.; Kuo, W.S.; Tzeng, C.R. Integration of genome-wide association study and expression quantitative trait locus mapping for identification of endometriosis-associated genes. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, L.; Zheng, Z.; Fang, H.; Yang, J. A generalized linear mixed model association tool for biobank-scale data. Nat. Genet. 2021, 53, 1616–1621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakaue, S.; Kanai, M.; Tanigawa, Y.; Karjalainen, J.; Kurki, M.; Koshiba, S.; Narita, A.; Konuma, T.; Yamamoto, K.; Akiyama, M.; et al. A cross-population atlas of genetic associations for 220 human phenotypes. Nat. Genet. 2021, 53, 1415–1424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGrath, I.M.; International Endometriosis Genetics Consortium; Montgomery, G.W.; Mortlock, S. Genomic characterisation of the overlap of endometriosis with 76 comorbidities identifies pleiotropic and causal mechanisms underlying disease risk. Hum. Genet. 2023, 142, 1345–1360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahmioglu, N.; Mortlock, S.; Ghiasi, M.; Møller, P.L.; Stefansdottir, L.; Galarneau, G.; Turman, C.; Danning, R.; Law, M.H.; Sapkota, Y.; et al. The genetic basis of endometriosis and comorbidity with other pain and inflammatory conditions. Nat. Genet. 2023, 55, 423–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walters, R.G.; Millwood, I.Y.; Lin, K.; Schmidt Valle, D.; McDonnell, P.; Hacker, A.; Avery, D.; Edris, A.; Fry, H.; Cai, N.; et al. Genotyping and population characteristics of the China Kadoorie Biobank. Cell Genom. 2023, 3, 100361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Auwerx, C.; Jõeloo, M.; Sadler, M.C.; Tesio, N.; Ojavee, S.; Clark, C.J.; Mägi, R.; Estonian Biobank Research Team; Reymond, A.; Kutalik, Z. Rare copy-number variants as modulators of common disease susceptibility. Genome Med. 2024, 16, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verma, A.; Huffman, J.E.; Rodriguez, A.; Conery, M.; Liu, M.; Ho, Y.L.; Kim, Y.; Heise, D.A.; Guare, L.; Panickan, V.A.; et al. Diversity and scale: Genetic architecture of 2068 traits in the VA Million Veteran Program. Science 2024, 385, eadj1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, T.Y.; Lu, H.F.; Chen, Y.C.; Liao, C.C.; Lin, Y.J.; Yang, J.S.; Liao, W.L.; Lin, W.D.; Chen, S.Y.; Huang, Y.C.; et al. Diversity and longitudinal records: Genetic architecture of disease associations and polygenic risk in the Taiwanese Han population. Sci. Adv. 2025, 11, eadt0539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pujol Gualdo, N.; Džigurski, J.; Rukins, V.; Pajuste, F.D.; Wolford, B.N.; Võsa, M.; Golob, M.; Haug, L.; Alver, M.; Läll, K.; et al. Atlas of genetic and phenotypic associations across 42 female reproductive health diagnoses. Nat. Med. 2025, 31, 1626–1634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shigesi, N.; Harris, H.R.; Fang, H.; Ndungu, A.; Lincoln, M.R.; International Endometriosis Genome Consortium; 23andMe Research Team; Cotsapas, C.; Knight, J.; Missmer, S.A.; et al. The phenotypic and genetic association between endometriosis and immunological diseases. Hum. Reprod. 2025, 40, 1195–1209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panidis, D.; Kokkinos, T.; Vavilis, D.; Rousso, D.; Tantanassis, T.; Kalogeropoulos, A. SHBG-Serumspiegel bein Frauen mit Endometriose vor, während und nach Danazol-Langzeittherapie [SHBG serum level in women with endometriosis before, during and after long-term danazol therapy]. Geburtshilfe Frauenheilkd. 1993, 53, 121–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Misao, R.; Hori, M.; Ichigo, S.; Fujimoto, J.; Tamaya, T. Levels of sex hormone-binding globulin (SHBG) and corticosteroid-binding globulin (CBG) messenger ribonucleic acid (mRNAs) in ovarian endometriosis. Reprod. Nutr. Dev. 1995, 35, 155–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Misao, R.; Nakanishi, Y.; Fujimoto, J.; Tamaya, T. Expression of sex hormone-binding globulin exon VII splicing variant messenger ribonucleic acid in human ovarian endometriosis. Fertil. Steril. 1998, 69, 324–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crespi, B. Variation among human populations in endometriosis and PCOS A test of the inverse comorbidity model. Evol. Med. Public Health 2021, 9, 95–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinsdale, N.; Nepomnaschy, P.; Crespi, B. The evolutionary biology of endometriosis. Evol. Med. Public Health 2021, 9, 74–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinsdale, N.L.; Crespi, B.J. Endometriosis and polycystic ovary syndrome are diametric disorders. Evol. Appl. 2021, 14, 1693–1715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foster, W.G.; Leonardi, M. Endometriosis—Novel approaches and controversies debated. Reprod Fertil. 2021, 2, C39–C41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saunders, P.T.K. Insights from genomic studies on the role of sex steroids in the aetiology of endometriosis. Reprod. Fertil. 2022, 3, R51–R65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McGrath, I.M.; International Endometriosis Genetics Consortium; Montgomery, G.W.; Mortlock, S. Polygenic risk score phenome-wide association study reveals an association between endometriosis and testosterone. BMC Med. 2023, 21, 482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coviello, A.D.; Zhuang, W.V.; Lunetta, K.L.; Bhasin, S.; Ulloor, J.; Zhang, A.; Karasik, D.; Kiel, D.P.; Vasan, R.S.; Murabito, J.M. Circulating testosterone and SHBG concentrations are heritable in women: The Framingham Heart Study. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2011, 96, E1491–E1495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balogh, A.; Karpati, E.; Schneider, A.E.; Hetey, S.; Szilagyi, A.; Juhasz, K.; Laszlo, G.; Hupuczi, P.; Zavodszky, P.; Papp, Z.; et al. Sex hormone-binding globulin provides a novel entry pathway for estradiol and influences subsequent signaling in lymphocytes via membrane receptor. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammond, G.L. Plasma steroid-binding proteins: Primary gatekeepers of steroid hormone action. J. Endocrinol. 2016, 230, R13–R25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinnott-Armstrong, N.; Naqvi, S.; Rivas, M.; Pritchard, J.K. GWAS of three molecular traits highlights core genes and pathways alongside a highly polygenic background. Elife 2021, 10, e58615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunn, J.F.; Nisula, B.C.; Rodbard, D. Transport of steroid hormones: Binding of 21 endogenous steroids to both testosterone-binding globulin and corticosteroid-binding globulin in human plasma. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 1981, 53, 58–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohlsson, C.; Wallaschofski, H.; Lunetta, K.L.; Stolk, L.; Perry, J.R.; Koster, A.; Petersen, A.K.; Eriksson, J.; Lehtimäki, T.; Huhtaniemi, I.T.; et al. Genetic determinants of serum testosterone concentrations in men. PLoS Genet. 2011, 7, e1002313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prescott, J.; Thompson, D.J.; Kraft, P.; Chanock, S.J.; Audley, T.; Brown, J.; Leyland, J.; Folkerd, E.; Doody, D.; Hankinson, S.E.; et al. Genome-wide association study of circulating estradiol, testosterone, and sex hormone-binding globulin in postmenopausal women. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e37815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coviello, A.D.; Haring, R.; Wellons, M.; Vaidya, D.; Lehtimäki, T.; Keildson, S.; Lunetta, K.L.; He, C.; Fornage, M.; Lagou, V.; et al. A genome-wide association meta-analysis of circulating sex hormone-binding globulin reveals multiple Loci implicated in sex steroid hormone regulation. PLoS Genet. 2012, 8, e1002805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruth, K.S.; Campbell, P.J.; Chew, S.; Lim, E.M.; Hadlow, N.; Stuckey, B.G.; Brown, S.J.; Feenstra, B.; Joseph, J.; Surdulescu, G.L.; et al. Genome-wide association study with 1000 genomes imputation identifies signals for nine sex hormone-related phenotypes. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 2016, 24, 284–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruth, K.S.; Day, F.R.; Tyrrell, J.; Thompson, D.J.; Wood, A.R.; Mahajan, A.; Beaumont, R.N.; Wittemans, L.; Martin, S.; Busch, A.S.; et al. Using human genetics to understand the disease impacts of testosterone in men and women. Nat. Med. 2020, 26, 252–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haas, C.B.; Hsu, L.; Lampe, J.W.; Wernli, K.J.; Lindström, S. Cross-ancestry Genome-wide Association Studies of Sex Hormone Concentrations in Pre- and Postmenopausal Women. Endocrinology 2022, 163, bqac020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison, S.; Davies, N.M.; Howe, L.D.; Hughes, A. Testosterone and socioeconomic position: Mendelian randomization in 306,248 men and women in UK Biobank. Sci. Adv. 2021, 7, eabf8257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shafrir, A.L.; Mu, F.; Eliassen, A.H.; Thombre Kulkarni, M.; Terry, K.L.; Hankinson, S.E.; Missmer, S.A. Endogenous Steroid Hormone Concentrations and Risk of Endometriosis in Nurses’ Health Study II. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2023, 192, 573–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Vaart, J.F.; Merki-Feld, G.S. Sex hormone-related polymorphisms in endometriosis and migraine: A narrative review. Womens Health 2022, 18, 17455057221111315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golovchenko, I.; Aizikovich, B.; Golovchenko, O.; Reshetnikov, E.; Churnosova, M.; Aristova, I.; Ponomarenko, I.; Churnosov, M. Sex Hormone Candidate Gene Polymorphisms Are Associated with Endometriosis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 13691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garitazelaia, A.; Rueda-Martínez, A.; Arauzo, R.; de Miguel, J.; Cilleros-Portet, A.; Marí, S.; Bilbao, J.R.; Fernandez-Jimenez, N.; García-Santisteban, I. A Systematic two-sample Mendelian randomization analysis identifies shared genetic origin of endometriosis and associated phenotypes. Life 2021, 11, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ponomarenko, M.; Reshetnikov, E.; Churnosova, M.; Aristova, I.; Abramova, M.; Novakov, V.; Churnosov, V.; Polonikov, A.; Plotnikov, D.; Churnosov, M.; et al. Genetic Variants Linked with the Concentration of Sex Hormone-Binding Globulin Correlate with Uterine Fibroid Risk. Life 2025, 15, 1150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sinnott-Armstrong, N.; Tanigawa, Y.; Amar, D.; Mars, N.; Benner, C.; Aguirre, M.; Venkataraman, G.R.; Wainberg, M.; Ollila, H.M.; Kiiskinen, T.; et al. Genetics of 35 blood and urine biomarkers in the UK Biobank. Nat. Genet. 2021, 53, 185–194, Erratum in Nat Genet. 2021, 53, 1622. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41588-021-00956-2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, J.; Huffman, J.E.; Huang, Y.; Do Valle, Í.; Assimes, T.L.; Raghavan, S.; Voight, B.F.; Liu, C.; Barabási, A.L.; Huang, R.D.L.; et al. Genomics and phenomics of body mass index reveals a complex disease network. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 7973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Backonja, U.; Buck Louis, G.M.; Lauver, D.R. Overall Adiposity, Adipose Tissue Distribution, and Endometriosis: A Systematic Review. Nurs. Res. 2016, 65, 151–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yong, L.; Weiyuan, Z. Association between body mass index and endometriosis risk: A meta-analysis. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 46928–46936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shafrir, A.L.; Farland, L.V.; Shah, D.K.; Harris, H.R.; Kvaskoff, M.; Zondervan, K.; Missmer, S.A. Risk for and consequences of endometriosis: A critical epidemiologic review. Best. Pract. Res. Clin. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2018, 51, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byun, J.; Peterson, C.M.; Backonja, U.; Taylor, R.N.; Stanford, J.B.; Allen-Brady, K.L.; Smith, K.R.; Louis, G.M.B.; Schliep, K.C. Adiposity and endometriosis severity and typology. J. Minim. Invasive Gynecol. 2020, 27, 1516–1523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahmioglu, N.; Macgregor, S.; Drong, A.W.; Hedman, Å.K.; Harris, H.R.; Randall, J.C.; Prokopenko, I.; International Endogene Consortium (IEC); The GIANT Consortium; Nyholt, D.R.; et al. Genome-wide enrichment analysis between endometriosis and obesity-related traits reveals novel susceptibility loci. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2015, 24, 1185–1199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baglietto, L.; English, D.R.; Hopper, J.L.; MacInnis, R.J.; Morris, H.A.; Tilley, W.D.; Krishnan, K.; Giles, G.G. Circulating steroid hormone concentrations in postmenopausal women in relation to body size and composition. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2009, 115, 171–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liedtke, S.; Schmidt, M.E.; Vrieling, A.; Lukanova, A.; Becker, S.; Kaaks, R.; Zaineddin, A.K.; Buck, K.; Benner, A.; Chang-Claude, J.; et al. Postmenopausal sex hormones in relation to body fat distribution. Obesity 2012, 20, 1088–1095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.W.; Hang, D.; Kværner, A.S.; Giovannucci, E.; Song, M. Associations between body shape across the life course and adulthood concentrations of sex hormones in men and pre- and postmenopausal women: A multicohort study. Br. J. Nutr. 2022, 127, 1000–1009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hammond, G.L. Diverse roles for sex hormone-binding globulin in reproduction. Biol. Reprod. 2011, 85, 431–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giordano, C.; Accattatis, F.M.; Gelsomino, L.; Del Console, P.; Győrffy, B.; Giuliano, M.; Veneziani, B.M.; Arpino, G.; De Angelis, C.; De Placido, P.; et al. miRNAs in the Box: Potential Diagnostic Role for Extracellular Vesicle-Packaged miRNA-27a and miRNA-128 in Breast Cancer. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 15695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Mertens-Talcott, S.U.; Zhang, S.; Kim, K.; Ball, J.; Safe, S. MicroRNA-27a Indirectly Regulates Estrogen Receptor α Expression and Hormone Responsiveness in MCF-7 Breast Cancer Cells. Endocrinology 2010, 151, 2462–2473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, W.; Zhu, J.; Su, S.; Wu, W.; Liu, Q.; Su, F.; Yu, F. MiR-27 as a prognostic marker for breast cancer progression and patient survival. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e51702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, Y.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, Z.; Shu, Y.; Luo, X.; Yang, Y.; Wang, X.; Yang, G.; Li, L.; Feng, Y. The microRNA-27a: ZBTB10-specificity protein pathway is involved in follicle stimulating hormone-induced VEGF, Cox2 and survivin expression in ovarian epithelial cancer cells. Int. J. Oncol. 2013, 42, 776–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ponomarenko, I.; Pasenov, K.; Churnosova, M.; Sorokina, I.; Aristova, I.; Churnosov, V.; Ponomarenko, M.; Reshetnikov, E.; Churnosov, M. Sex-Hormone-Binding Globulin Gene Polymorphisms and Breast Cancer Risk in Caucasian Women of Russia. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 2182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benagiano, G.; Brosens, I.; Habiba, M. Structural and molecular features of the endomyometrium in endometriosis and adenomyosis. Hum. Reprod. Update 2014, 20, 386–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hedrick, E.; Cheng, Y.; Jin, U.-H.; Kim, K.; Safe, S. Specificity protein (Sp) transcription factors Sp1, Sp3 and Sp4 are non-oncogene addiction genes in cancer cells. Oncotarget 2016, 7, 22245–22256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varghese, J.S.; Smith, P.L.; Folkerd, E.; Brown, J.; Leyland, J.; Audley, T.; Warren, R.M.; Dowsett, M.; Easton, D.F.; Thompson, D.J. The heritability of mammographic breast density and circulating sex-hormone levels: Two independent breast cancer risk factors. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomarkers Prev. 2012, 21, 2167–2175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimou, N.L.; Papadimitriou, N.; Gill, D.; Christakoudi, S.; Murphy, N.; Gunter, M.J.; Travis, R.C.; Key, T.J.; Fortner, R.T.; Haycock, P.C.; et al. Sex hormone binding globulin and risk of breast cancer: A Mendelian randomization study. Int. J. Epidemiol. 2019, 48, 807–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asai, M.; Ohsawa, M.; Ichikawa, Y.; Wu, M.C.; Masahashi, T.; Narita, O.; Matsui, N.; Kashiwamata, S. Changes in % free testosterone and sex-hormone binding globulin during danazol administration. Nihon Sanka Fujinka Gakkai Zasshi 1985, 37, 1001–1006. (In Japanese) [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Crespi, B.J.; Evans, S.F. Prenatal Origins of Endometriosis Pathology and Pain: Reviewing the Evidence of a Role for Low Testosterone. J. Pain. Res. 2023, 16, 307–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wood, A.R.; Perry, J.R.; Tanaka, T.; Hernandez, D.G.; Zheng, H.F.; Melzer, D.; Gibbs, J.R.; Nalls, M.A.; Weedon, M.N.; Spector, T.D.; et al. Imputation of variants from the 1000 Genomes Project modestly improves known associations and can identify low-frequency variant-phenotype associations undetected by HapMap based imputation. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e64343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golovchenko, I.O. Genetic determinants of sex hormone levels in endometriosis patients. Res. Results Biomed. 2023, 9, 5–21. (In Russian) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abramova, M.; Churnosova, M.; Efremova, O.; Aristova, I.; Reshetnikov, E.; Polonikov, A.; Churnosov, M.; Ponomarenko, I. Effects of pre-pregnancy over-weight/obesity on the pattern of association of hypertension susceptibility genes with preeclampsia. Life 2022, 12, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Churnosov, M.; Abramova, M.; Reshetnikov, E.; Lyashenko, I.V.; Efremova, O.; Churnosova, M.; Ponomarenko, I. Polymorphisms of hypertension susceptibility genes as a risk factors of preeclampsia in the Caucasian population of central Russia. Placenta 2022, 129, 51–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sergeeva, K.N.; Sorokina, I.N. Assessment of the relationship between marriage and migration characteristics of the population of the Belgorod region in dynamics over 130 years. Res. Results Biomed. 2024, 10, 374–388. (In Russian) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Society for Reproductive Medicine. Revised American Society for Reproductive Medicine classification of endometriosis: 1996. Fertil. Steril. 1997, 5, 817–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novakov, V.; Novakova, O.; Churnosova, M.; Sorokina, I.; Aristova, I.; Polonikov, A.; Reshetnikov, E.; Churnosov, M. Intergenic Interactions of SBNO1, NFAT5 and GLT8D1 Determine the Susceptibility to Knee Osteoarthritis among Europeans of Russia. Life 2023, 13, 405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reshetnikov, E.; Ponomarenko, I.; Golovchenko, O.; Sorokina, I.; Batlutskaya, I.; Yakunchenko, T.; Dvornyk, V.; Polonikov, A.; Churnosov, M. The VNTR polymorphism of the endothelial nitric oxide synthase gene and blood pressure in women at the end of pregnancy. Taiwan. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2019, 58, 390–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eliseeva, N.; Ponomarenko, I.; Reshetnikov, E.; Dvornyk, V.; Churnosov, M. LOXL1 gene polymorphism candidates for exfoliation glaucoma are also associated with a risk for primary open-angle glaucoma in a Caucasian population from central Russia. Mol. Vis. 2021, 27, 262–269. [Google Scholar]

- Fantus, R.J.; Na, R.; Wei, J.; Shi, Z.; Resurreccion, W.K.; Halpern, J.A.; Franco, O.; Hayward, S.W.; Isaacs, W.B.; Zheng, S.L.; et al. Genetic Susceptibility for Low Testosterone in Men and Its Implications in Biology and Screening: Data from the UK Biobank. Eur. Urol. Open Sci. 2021, 29, 36–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ponomarenko, I.; Pasenov, K.; Churnosova, M.; Sorokina, I.; Aristova, I.; Churnosov, V.; Ponomarenko, M.; Reshetnikova, Y.; Reshetnikov, E.; Churnosov, M. Obesity-Dependent Association of the rs10454142 PPP1R21 with Breast Cancer. Biomedicines 2024, 12, 818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Churnosov, V.I. Associations of polymorphic loci of candidate genes with the level of sex hormones in patients with endometrial hyperplasia. Res. Results Biomed. 2025, 11, 243–262. (In Russian) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ponomarenko, M.; Reshetnikov, E.; Churnosova, M.; Aristova, I.; Abramova, M.; Novakov, V.; Churnosov, V.; Polonikov, A.; Churnosov, M.; Ponomarenko, I. Obesity/Overweight as a Meaningful Modifier of Associations Between Gene Polymorphisms Affecting the Sex Hormone-Binding Globulin Content and Uterine Myoma. Life 2025, 15, 1459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pasenov, K.N. Features of associations of SHBG-related genes with breast cancer in women, depending on the presence of hereditary burden and mutations in the BRCA1/CHEK2 genes. Res. Results Biomed. 2024, 10, 69–88. (In Russian) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ponomarenko, M.S. The relationship between the genetic determinants of SHBG and the hormonal profile of patients with uterine fibroids. Res. Results Biomed. 2025, 11, 628–642. (In Russian) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavlova, N.; Demin, S.; Churnosov, M.; Reshetnikov, E.; Aristova, I.; Churnosova, M.; Ponomarenko, I. The Modifying Effect of Obesity on the Association of Matrix Metalloproteinase Gene Polymorphisms with Breast Cancer Risk. Biomedicines 2022, 10, 2617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivanova, T.; Churnosova, M.; Abramova, M.; Plotnikov, D.; Ponomarenko, I.; Reshetnikov, E.; Aristova, I.; Sorokina, I.; Churnosov, M. Sex-Specific Features of the Correlation between GWAS-Noticeable Polymorphisms and Hypertension in Europeans of Russia. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 7799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novakov, V.; Novakova, O.; Churnosova, M.; Aristova, I.; Ponomarenko, M.; Reshetnikova, Y.; Churnosov, V.; Sorokina, I.; Ponomarenko, I.; Efremova, O.; et al. Polymorphism rs143384 GDF5 reduces the risk of knee osteoarthritis development in obese individuals and increases the disease risk in non-obese population. Arthroplasty 2024, 6, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Purcell, S.; Neale, B.; Todd-Brown, K.; Thomas, L.; Ferreira, M.A.; Bender, D.; Maller, J.; Sklar, P.; de Bakker, P.I.; Daly, M.J.; et al. PLINK: A tool set for whole-genome association and population-based linkage analyses. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2007, 81, 559–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Che, R.; Jack, J.R.; Motsinger-Reif, A.A.; Brown, C.C. An adaptive permutation approach for genome-wide association study: Evaluation and recommendations for use. BioData Min. 2014, 7, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gauderman, A.; Gauderman, W.; Morrison, J.M.; Gauderman, W.J.; Morrison, J.M.; Morrison, W.G.J. QUANTO 1.1: A Computer Program for Power and Sample Size Calculations Genetic–Epidemiology Studies. 2006. Available online: https://www.scienceopen.com/document?vid=2944f68a-3b3d-4e86-90a3-3d3c1fab3ffa (accessed on 10 June 2025).

- Ivanova, T.; Churnosova, M.; Abramova, M.; Ponomarenko, I.; Reshetnikov, E.; Aristova, I.; Sorokina, I.; Churnosov, M. Risk Effects of rs1799945 Polymorphism of the HFE Gene and Intergenic Interactions of GWAS-Significant Loci for Arterial Hypertension in the Caucasian Population of Central Russia. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 8309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calle, M.L.; Urrea, V.; Malats, N.; Van Steen, K. Mbmdr: An R package for exploring gene-gene interactions associated with binary or quantitative traits. Bioinformatics 2010, 26, 2198–2199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, J.H.; Gilbert, J.C.; Tsai, C.T.; Chiang, F.T.; Holden, T.; Barney, N.; White, B.C. A flexible computational framework for detecting, characterizing, and interpreting statistical patterns of epistasis in genetic studies of human disease susceptibility. J. Theor. Biol. 2006, 241, 252–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reshetnikova, Y.; Churnosova, M.; Stepanov, V.; Bocharova, A.; Serebrova, V.; Trifonova, E.; Ponomarenko, I.; Sorokina, I.; Efremova, O.; Orlova, V.; et al. Maternal Age at Menarche Gene Polymorphisms Are Associated with Offspring Birth Weight. Life 2023, 13, 1525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minyaylo, O.; Ponomarenko, I.; Reshetnikov, E.; Dvornyk, V.; Churnosov, M. Functionally significant polymorphisms of the MMP-9 gene are associated with peptic ulcer disease in the Caucasian population of Central Russia. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 13515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavlova, N.; Demin, S.; Churnosov, M.; Reshetnikov, E.; Aristova, I.; Churnosova, M.; Ponomarenko, I. Matrix Metalloproteinase Gene Polymorphisms Are Associated with Breast Cancer in the Caucasian Women of Russia. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 12638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reshetnikov, E.; Churnosova, M.; Reshetnikova, Y.; Stepanov, V.; Bocharova, A.; Serebrova, V.; Trifonova, E.; Ponomarenko, I.; Sorokina, I.; Efremova, O.; et al. Maternal Age at Menarche Genes Determines Fetal Growth Restriction Risk. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 2647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ward, L.D.; Kellis, M. HaploReg v4: Systematic mining of putative causal variants, cell types, regulators and target genes for human complex traits and disease. Nucleic. Acids Res. 2016, 44, D877–D881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GTEx Consortium. The GTEx Consortium atlas of genetic regulatory effects across human tissues. Science 2020, 369, 1318–1330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szklarczyk, D.; Kirsch, R.; Koutrouli, M.; Nastou, K.; Mehryary, F.; Hachilif, R.; Gable, A.L.; Fang, T.; Doncheva, N.T.; Pyysalo, S.; et al. The STRING database in 2023: Protein-protein association networks and functional enrichment analyses for any sequenced genome of interest. Nucleic Acids Res. 2023, 51, D638–D646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Parameters | Cases (n = 395) ± SD/% (n) | Controls (n = 973) ± SD/% (n) | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 39.75 ± 9.01 | 40.71 ± 8.60 | >0.05 |

| Height, m | 1.65 ± 0.06 | 1.65 ± 0.06 | >0.05 |

| Weight, kg | 72.65 ± 14.38 | 72.47 ± 13.36 | >0.05 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 26.63 ± 5.31 | 26.65 ± 4.60 | >0.05 |

| Proportion of the participants by relative BMI, % (n): | |||

| Underweight (<18.50) | 4.30 (17) | 1.13 (11) | |

| Normal weight (18.50–24.99) | 37.72 (149) | 42.55 (414) | >0.05 |

| Overweight (25.00–29.99) | 31.65 (125) | 30.32 (295) | |

| Obese (>30.00) | 26.33 (104) | 26.00 (253) | |

| Family history of endometriosis (yes) | 6.07 (24) | 1.95 (19) | <0.001 |

| Married | 82.53 (326) | 85.82 (835) | >0.05 |

| Smoking (yes) | 18.22 (72) | 17.47 (170) | >0.05 |

| Drinking alcohol (≥7 drinks per week) | 4.05 (16) | 3.08 (30) | >0.05 |

| History of pelvic surgery (laparoscopy and/or laparotomy) | 15.19 (60) | 9.76 (95) | <0.01 |

| Oral contraceptive use | 8.10 (32) | 9.76 (95) | >0.05 |

| Age at menarche and menstrual cycle | |||

| Age at menarche, years | 13.29 ± 1.27 | 13.26 ± 1.25 | >0.05 |

| Proportion of the participants by relative age at menarche, % (n) | |||

| Early (<12 years) | 6.36 (25) | 6.47 (63) | |

| Average (12–14 years) | 81.17 (319) | 80.16 (780) | >0.05 |

| Late (>14 years) | 12.47 (49) | 13.36 (130) | |

| Duration of bleeding menstrual (mean, days) | 5.13 ± 1.56 | 4.95 ± 0.93 | >0.05 |

| Menstrual cycle length (mean, days) | 27.66 ± 2.28 | 28.16 ± 2.25 | <0.001 |

| Reproductive characteristic | |||

| Age at first birth (mean. years) | 21.25 ± 3.04 | 21.70 ± 3.48 | >0.05 |

| Gravidity (mean) | 2.60 ± 2.31 | 2.46 ± 1.56 | >0.05 |

| No. of births (mean) | 1.07 ± 0.97 | 1.51 ± 0.67 | <0.001 |

| No. of spontaneous abortions (mean) | 0.21 ± 0.61 | 0.24 ± 0.51 | >0.05 |

| No. of induced abortions (mean) | 1.25 ± 1.61 | 0.67 ± 0.99 | <0.001 |

| No. of induced abortions: | |||

| 0 | 46.58 (184) | 58.99 (574) | |

| 1 | 17.22 (68) | 23.54 (229) | |

| 2 | 19.24 (76) | 10.48 (102) | |

| 3 | 8.61 (34) | 5.45 (53) | <0.001 |

| ≥4 | 8.35 (33) | 1.54 (15) | |

| History of infertility | 32.42 (132) | 5.24 (51) | <0.001 |

| Gynecological pathologies | |||

| Uterine leiomyoma | 52.40 (207) | - | - |

| Endometrial hyperplasia | 46.33 (183) | - | - |

| Adenomyosis | 43.04 (170) | - | - |

| SNP | Gene | Minor Allele | n | Allelic Model | Additive Model | Dominant Model | Recessive Model | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | 95%CI | p | OR | 95%CI | p | OR | 95%CI | P | OR | 95%CI | p | ||||||||

| L95 | U95 | L95 | U95 | L95 | U95 | L95 | U95 | ||||||||||||

| rs17496332 | PRMT6 | G | 1292 | 1.01 | 0.84 | 1.20 | 0.941 | 1.03 | 0.86 | 1.23 | 0.761 | 1.01 | 0.78 | 1.30 | 0.959 | 1.01 | 0.77 | 1.57 | 0.598 |

| rs780093 | GCKR | T | 1310 | 0.98 | 0.83 | 1.17 | 0.828 | 0.97 | 0.81 | 1.16 | 0.727 | 0.97 | 0.75 | 1.26 | 0.836 | 0.93 | 0.66 | 1.33 | 0.699 |

| rs10454142 | PPP1R21 | C | 1291 | 0.87 | 0.72 | 1.05 | 0.153 | 0.91 | 0.74 | 1.10 | 0.321 | 0.84 | 0.65 | 1.08 | 0.170 | 1.03 | 0.67 | 1.58 | 0.907 |

| rs3779195 | BAIAP2L1 | A | 1290 | 1.02 | 0.82 | 1.27 | 0.870 | 1.02 | 0.81 | 1.29 | 0.860 | 1.12 | 0.86 | 1.47 | 0.405 | 0.49 | 0.20 | 1.15 | 0.100 |

| rs440837 | ZBTB10 | G | 1282 | 1.01 | 0.83 | 1.24 | 0.915 | 1.02 | 0.82 | 1.26 | 0.868 | 0.91 | 0.70 | 1.18 | 0.474 | 1.91 | 1.13 | 2.98 | 0.023 |

| rs7910927 | JMJD1C | T | 1311 | 0.89 | 0.75 | 1.05 | 0.164 | 0.89 | 0.75 | 1.07 | 0.208 | 0.80 | 0.61 | 1.07 | 0.128 | 0.93 | 0.69 | 1.25 | 0.610 |

| rs4149056 | SLCO1B1 | C | 1264 | 0.93 | 0.76 | 1.14 | 0.490 | 0.94 | 0.76 | 1.17 | 0.601 | 0.91 | 0.70 | 1.18 | 0.472 | 1.06 | 0.60 | 1.87 | 0.852 |

| rs8023580 | NR2F2 | C | 1304 | 0.99 | 0.82 | 1.19 | 0.905 | 1.03 | 0.85 | 1.26 | 0.763 | 1.13 | 0.87 | 1.45 | 0.355 | 0.78 | 0.47 | 1.27 | 0.316 |

| rs12150660 | SHBG | T | 1323 | 0.91 | 0.74 | 1.10 | 0.327 | 0.88 | 0.72 | 1.09 | 0.243 | 0.92 | 0.71 | 1.18 | 0.495 | 0.64 | 0.36 | 1.12 | 0.120 |

| N | SNP × SNP Interaction Models | NH | betaH | WH | NL | betaL | WL | pperm |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Two-order interaction models (p = 1.25 × 10−3) | ||||||||

| 1 | rs440837 ZBTB10-rs3779195 BAIAP2L1 | 1 | 0.412 | 4.07 | 1 | −0.513 | 10.41 | 0.008 |

| Three-order interaction models (p = 8.33 × 10−6) | ||||||||

| 2 | rs8023580 NR2F2-rs440837 ZBTB10-rs3779195 BAIAP2L1 | 5 | 0.612 | 19.86 | 2 | −0.495 | 9.20 | 0.001 |

| Four-order interaction models (p = 9.65 × 10−8) | ||||||||

| 3 | rs440837 ZBTB10-rs10454142 PPP1R21-rs780093 GCKR-rs17496332 PRMT6 | 7 | 1.193 | 28.44 | 2 | −1.118 | 6.81 | 0.001 |

| Five-order interaction models (p = 1.95 × 10−11) | ||||||||

| 4 | rs8023580 NR2F2-rs7910927 JMJD1C-rs440837 ZBTB10-rs3779195 BAIAP2L1- rs780093 GCKR | 9 | 1.550 | 45.02 | 1 | −1.384 | 4.67 | 0.001 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ponomareva, T.; Altukhova, O.; Churnosova, M.; Aristova, I.; Reshetnikov, E.; Churnosov, M.; Ponomarenko, I. Gene Polymorphisms Determining Sex Hormone-Binding Globulin Levels and Endometriosis Risk. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 11630. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311630

Ponomareva T, Altukhova O, Churnosova M, Aristova I, Reshetnikov E, Churnosov M, Ponomarenko I. Gene Polymorphisms Determining Sex Hormone-Binding Globulin Levels and Endometriosis Risk. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2025; 26(23):11630. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311630

Chicago/Turabian StylePonomareva, Tatiana, Oxana Altukhova, Maria Churnosova, Inna Aristova, Evgeny Reshetnikov, Mikhail Churnosov, and Irina Ponomarenko. 2025. "Gene Polymorphisms Determining Sex Hormone-Binding Globulin Levels and Endometriosis Risk" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 26, no. 23: 11630. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311630

APA StylePonomareva, T., Altukhova, O., Churnosova, M., Aristova, I., Reshetnikov, E., Churnosov, M., & Ponomarenko, I. (2025). Gene Polymorphisms Determining Sex Hormone-Binding Globulin Levels and Endometriosis Risk. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 26(23), 11630. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311630