CPX-351 and the Frontier of Nanoparticle-Based Therapeutics in Acute Myeloid Leukemia

Abstract

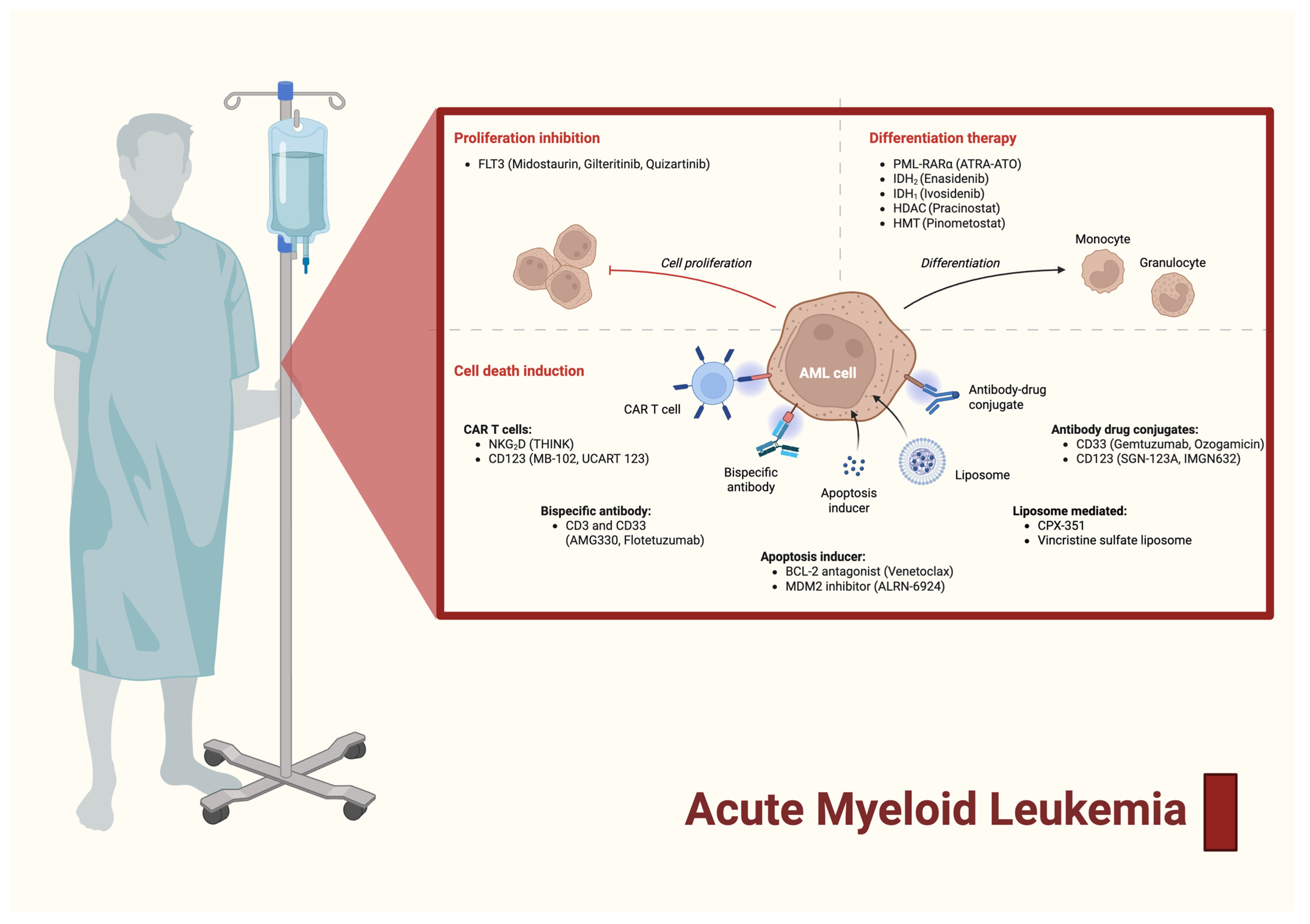

1. Introduction

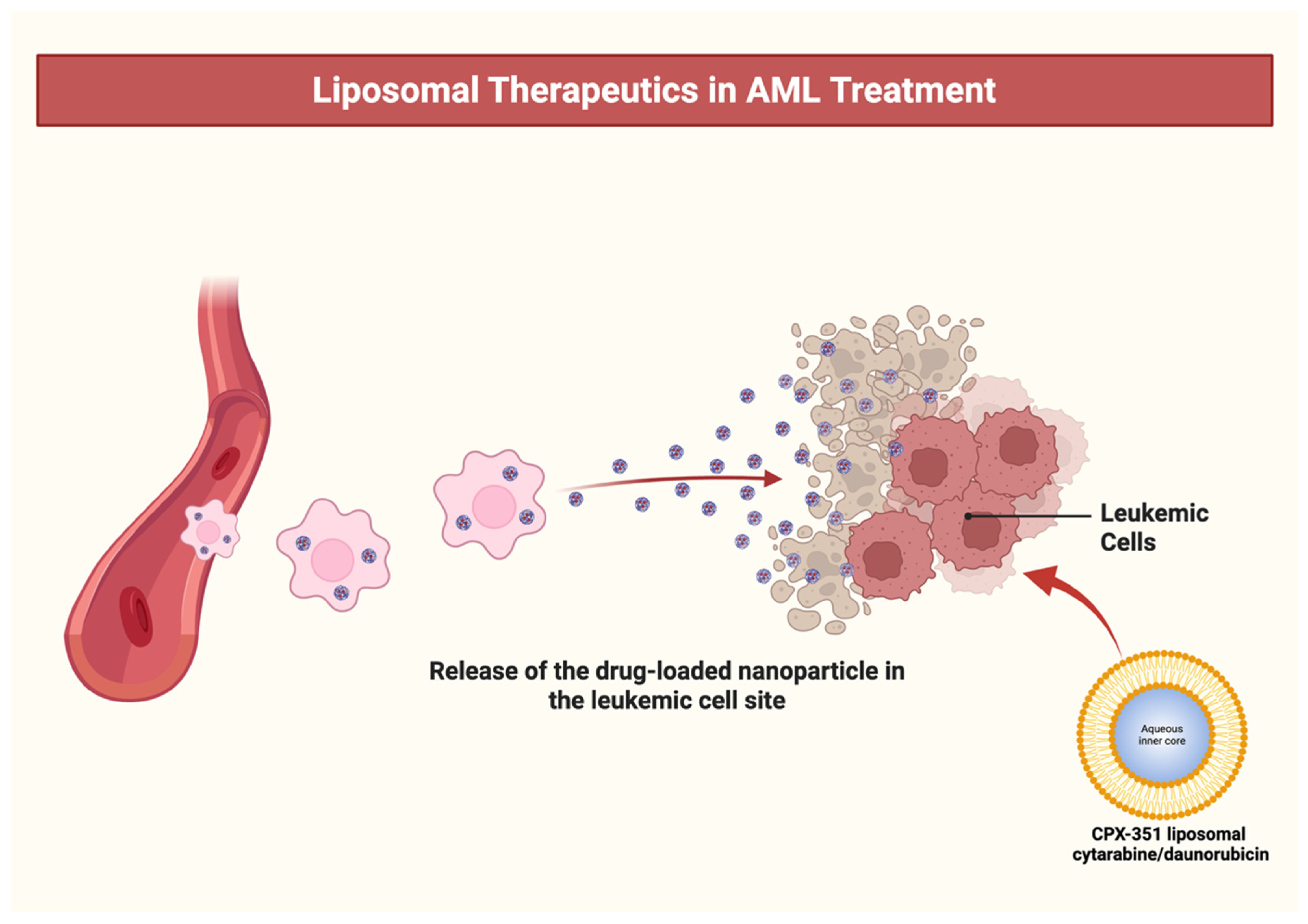

2. The Paradigm Shift from 7 + 3 to Ratiometric Nanomedicine

3. Mechanism of Action of CPX-351 in AML

4. Comparative Dosing and Administration of Cytarabine: Conventional Regimens vs. CPX-351 in AML

5. Commonly Studied Groups in CPX-351 Versus Conventional Cytarabine for AML

6. FDA-Drug Approval and the Pivotal Trial

7. CPX-351: Liposomal Innovation Driving Remission and Survival in High-Risk and Secondary AML Across Trials and Real-World Cohorts

7.1. Liposomal Mechanism and Therapeutic Rationale

7.2. Early-Phase Trials and Dose Optimization

7.3. Pivotal Phase III Trial—The Turning Point

7.4. Real-World Cohort Validation

7.5. Comparative Efficacy in Younger Adults

7.6. Post-Hoc Analyses Support CPX-351 as a Superior Induction and Consolidation Strategy in Older Adults with High-Risk AML

8. Therapeutic and Outcome-Based Comparison of CPX-351 Versus Conventional 7 + 3 Chemotherapy in AML

9. Limitations and Future Perspectives

10. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Khwaja, A.; Bjorkholm, M.; Gale, R.E.; Levine, R.L.; Jordan, C.T.; Ehninger, G.; Bloomfield, C.D.; Estey, E.; Burnett, A.; Cornelissen, J.J.; et al. Acute Myeloid Leukaemia. Nat. Rev. Dis. Prim. 2016, 2, 16010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shimony, S.; Stahl, M.; Stone, R.M. Acute Myeloid Leukemia: 2023 Update on Diagnosis, Risk-stratification, and Management. Am. J. Hematol. 2023, 98, 502–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pelcovits, A.; Niroula, R. Acute Myeloid Leukemia: A Review. Rhode Isl. Med. J. 2020, 103, 38–40. [Google Scholar]

- Naji, N.S.; Sathish, M.; Karantanos, T. Inflammation and Related Signaling Pathways in Acute Myeloid Leukemia. Cancers 2024, 16, 3974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venugopal, S.; Sekeres, M.A. Contemporary Management of Acute Myeloid Leukemia. JAMA Oncol. 2024, 10, 1417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DiNardo, C.D.; Erba, H.P.; Freeman, S.D.; Wei, A.H. Acute Myeloid Leukaemia. Lancet 2023, 401, 2073–2086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molica, M.; Perrone, S.; Mazzone, C.; Cesini, L.; Canichella, M.; de Fabritiis, P. CPX-351: An Old Scheme with a New Formulation in the Treatment of High-Risk AML. Cancers 2022, 14, 2843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, X.; Wang, F.; Yang, X.; Gong, Y.; Niu, T.; Chu, B.; Qu, Y.; Qian, Z. Advances in Drug Delivery Systems for the Treatment of Acute Myeloid Leukemia. Small 2024, 20, 2403409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, Q.; Mahato, R.I. Recent Advances in Drug Delivery and Treatment Strategies for Acute Myeloid Leukemia. Int. J. Pharm. 2025, 683, 126078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sauvage, F.; Barratt, G.; Herfindal, L.; Vergnaud-Gauduchon, J. The Use of Nanocarriers in Acute Myeloid Leukaemia Therapy: Challenges and Current Status. Curr. Pharm. Biotechnol. 2015, 17, 30–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janani, G.; Girigoswami, A.; Girigoswami, K. Advantages of Nanomedicine over the Conventional Treatment in Acute Myeloid Leukemia. J. Biomater. Sci. Polym. Ed. 2024, 35, 415–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salama, M.M.; Aborehab, N.M.; El Mahdy, N.M.; Zayed, A.; Ezzat, S.M. Nanotechnology in Leukemia: Diagnosis, Efficient-Targeted Drug Delivery, and Clinical Trials. Eur. J. Med. Res. 2023, 28, 566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DiNardo, C.D.; Pratz, K.; Pullarkat, V.; Jonas, B.A.; Arellano, M.; Becker, P.S.; Frankfurt, O.; Konopleva, M.; Wei, A.H.; Kantarjian, H.M.; et al. Venetoclax Combined with Decitabine or Azacitidine in Treatment-Naive, Elderly Patients with Acute Myeloid Leukemia. Blood 2019, 133, 7–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goulart, H.; Kantarjian, H.; Pemmaraju, N.; Daver, N.; DiNardo, C.D.; Rausch, C.R.; Ravandi, F.; Kadia, T.M. Venetoclax-Based Combination Regimens in Acute Myeloid Leukemia. Blood Cancer Discov. 2025, 6, 23–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shahid, A.M.; Vainchenker, W.; Constantinescu, S.N. JCMM Annual Review on Advances in Biotechnology for the Treatment of Haematological Malignancies: A Review of the Latest In-Patient Developments 2024–2025. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 2025, 29, e70700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DiNardo, C.D.; Wei, A.H. How I Treat Acute Myeloid Leukemia in the Era of New Drugs. Blood 2020, 135, 85–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thol, F. What to Use to Treat AML: The Role of Emerging Therapies. Hematology 2021, 2021, 16–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feldman, E.J.; Lancet, J.E.; Kolitz, J.E.; Ritchie, E.K.; Roboz, G.J.; List, A.F.; Allen, S.L.; Asatiani, E.; Mayer, L.D.; Swenson, C.; et al. First-in-Man Study of CPX-351: A Liposomal Carrier Containing Cytarabine and Daunorubicin in a Fixed 5:1 Molar Ratio for the Treatment of Relapsed and Refractory Acute Myeloid Leukemia. J. Clin. Oncol. 2011, 29, 979–985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lancet, J.E.; Cortes, J.E.; Hogge, D.E.; Tallman, M.S.; Kovacsovics, T.J.; Damon, L.E.; Komrokji, R.; Solomon, S.R.; Kolitz, J.E.; Cooper, M.; et al. Phase 2 Trial of CPX-351, a Fixed 5:1 Molar Ratio of Cytarabine/Daunorubicin, vs Cytarabine/Daunorubicin in Older Adults with Untreated AML. Blood 2014, 123, 3239–3246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cortes, J.E.; Goldberg, S.L.; Feldman, E.J.; Rizzeri, D.A.; Hogge, D.E.; Larson, M.; Pigneux, A.; Recher, C.; Schiller, G.; Warzocha, K.; et al. Phase II, Multicenter, Randomized Trial of CPX-351 (Cytarabine:Daunorubicin) Liposome Injection versus Intensive Salvage Therapy in Adults with First Relapse AML. Cancer 2015, 121, 234–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lancet, J.E.; Uy, G.L.; Newell, L.F.; Lin, T.L.; Ritchie, E.K.; Stuart, R.K.; Strickland, S.A.; Hogge, D.; Solomon, S.R.; Bixby, D.L.; et al. CPX-351 versus 7+3 Cytarabine and Daunorubicin Chemotherapy in Older Adults with Newly Diagnosed High-Risk or Secondary Acute Myeloid Leukaemia: 5-Year Results of a Randomised, Open-Label, Multicentre, Phase 3 Trial. Lancet Haematol. 2021, 8, e481–e491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krauss, A.C.; Gao, X.; Li, L.; Manning, M.L.; Patel, P.; Fu, W.; Janoria, K.G.; Gieser, G.; Bateman, D.A.; Przepiorka, D.; et al. FDA Approval Summary: (Daunorubicin and Cytarabine) Liposome for Injection for the Treatment of Adults with High-Risk Acute Myeloid Leukemia. Clin. Cancer Res. 2019, 25, 2685–2690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Issa, G.C.; Kantarjian, H.M.; Xiao, L.; Ning, J.; Alvarado, Y.; Borthakur, G.; Daver, N.; DiNardo, C.D.; Jabbour, E.; Bose, P.; et al. Phase II Trial of CPX-351 in Patients with Acute Myeloid Leukemia at High Risk for Induction Mortality. Leukemia 2020, 34, 2914–2924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolitz, J.E.; Strickland, S.A.; Cortes, J.E.; Hogge, D.; Lancet, J.E.; Goldberg, S.L.; Villa, K.F.; Ryan, R.J.; Chiarella, M.; Louie, A.C.; et al. Consolidation Outcomes in CPX-351 versus Cytarabine/Daunorubicin-Treated Older Patients with High-Risk/Secondary Acute Myeloid Leukemia. Leuk. Lymphoma 2020, 61, 631–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, T.L.; Rizzieri, D.A.; Ryan, D.H.; Schiller, G.J.; Kolitz, J.E.; Uy, G.L.; Hogge, D.E.; Solomon, S.R.; Wieduwilt, M.J.; Ryan, R.J.; et al. Older Adults with Newly Diagnosed High-Risk/Secondary AML Who Achieved Remission with CPX-351: Phase 3 Post Hoc Analyses. Blood Adv. 2021, 5, 1719–1728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Othman, J.; Wilhelm-Benartzi, C.; Dillon, R.; Knapper, S.; Freeman, S.D.; Batten, L.M.; Canham, J.; Hinson, E.L.; Wych, J.; Betteridge, S.; et al. A Randomized Comparison of CPX-351 and FLAG-Ida in Adverse Karyotype AML and High-Risk MDS: The UK NCRI AML19 Trial. Blood Adv. 2023, 7, 4539–4549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehta, P.; Campbell, V.; Maddox, J.; Floisand, Y.; Kalakonda, A.J.M.; O’Nions, J.; Coats, T.; Nagumantry, S.; Hodgson, K.; Whitmill, R.; et al. CREST-UK: Real-World Effectiveness, Safety and Outpatient Delivery of CPX-351 for First-Line Treatment of Newly Diagnosed Therapy-Related AML and AML with Myelodysplasia-Related Changes in the UK. Br. J. Haematol. 2024, 205, 1326–1336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cluzeau, T.; Guolo, F.; Chiche, E.; Minetto, P.; Rahme, R.; Bertoli, S.; Fianchi, L.; Micol, J.B.; Gottardi, M.; Peterlin, P.; et al. Long-Term Real-World Evidence of CPX-351 of High-Risk Patients with AML Identified High Rate of Negative MRD and Prolonged OS. Blood Adv. 2025, 9, 752–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hani, U.; Gowda, B.H.J.; Haider, N.; Ramesh, K.; Paul, K.; Ashique, S.; Ahmed, M.G.; Narayana, S.; Mohanto, S.; Kesharwani, P. Nanoparticle-Based Approaches for Treatment of Hematological Malignancies: A Comprehensive Review. AAPS PharmSciTech 2023, 24, 233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bishoyi, A.K.; Nouri, S.; Hussen, A.; Bayani, A.; Khaksari, M.N.; Soleimani Samarkhazan, H. Nanotechnology in Leukemia Therapy: Revolutionizing Targeted Drug Delivery and Immune Modulation. Clin. Exp. Med. 2025, 25, 166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, K.T.J.; Gilabert-Oriol, R.; Bally, M.B.; Leung, A.W.Y. Recent Treatment Advances and the Role of Nanotechnology, Combination Products, and Immunotherapy in Changing the Therapeutic Landscape of Acute Myeloid Leukemia. Pharm. Res. 2019, 36, 125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayer, L.D.; Tardi, P.; Louie, A.C. CPX-351: A Nanoscale Liposomal Co-Formulation of Daunorubicin and Cytarabine with Unique Biodistribution and Tumor Cell Uptake Properties. Int. J. Nanomed. 2019, 14, 3819–3830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morcos-Sandino, M.; Quezada-Ramírez, S.I.; Gómez-De León, A. Advances in the Treatment of Acute Myeloid Leukemia: Implications for Low- and Middle-Income Countries. Biomedicines 2025, 13, 1221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fard, N.T.; Khademi, M.; Salahi-Niri, A.; Esmaeili, S. Nanotechnology in Hematology: Enhancing Therapeutic Efficacy With Nanoparticles. Health Sci. Rep. 2025, 8, e70647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di, Y.; Wasan, E.K.; Cawthray, J.; Wasan, K.M. Scavenger Receptor Class BI (SR-BI) Mediates Uptake of CPX-351 into K562 Leukemia Cells. Drug Dev. Ind. Pharm. 2019, 45, 21–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araie, H.; Hosono, N.; Yamauchi, T. Cellular Uptake of CPX-351 by Scavenger Receptor Class B Type 1–Mediated Nonendocytic Pathway. Exp. Hematol. 2024, 140, 104651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, W.-S.; Tardi, P.G.; Dos Santos, N.; Xie, X.; Fan, M.; Liboiron, B.D.; Huang, X.; Harasym, T.O.; Bermudes, D.; Mayer, L.D. Leukemia-Selective Uptake and Cytotoxicity of CPX-351, a Synergistic Fixed-Ratio Cytarabine:Daunorubicin Formulation, in Bone Marrow Xenografts. Leuk. Res. 2010, 34, 1214–1223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anderson, E.; Mehta, P.; Heywood, J.; Rees, B.; Bone, H.; Robinson, G.; Reynolds, D.; Salisbury, V.; Mayer, L. CPX-351 Exhibits HENT-Independent Uptake and Can Be Potentiated by Fludarabine in Leukaemic Cells Lines and Primary Refractory AML. Leuk. Res. 2018, 74, 121–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pagano, L.; Danesi, R.; Benedetti, E.; Morgagni, R.; Romani, L.; Venditti, A. The Role of CPX-351 in the Acute Myeloid Leukemia Treatment Landscape: Mechanism of Action, Efficacy, and Safety. Drugs 2025, 85, 855–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tzogani, K.; Penttilä, K.; Lapveteläinen, T.; Hemmings, R.; Koenig, J.; Freire, J.; Márcia, S.; Cole, S.; Coppola, P.; Flores, B.; et al. EMA Review of Daunorubicin and Cytarabine Encapsulated in Liposomes (Vyxeos, CPX-351) for the Treatment of Adults with Newly Diagnosed, Therapy-Related Acute Myeloid Leukemia or Acute Myeloid Leukemia with Myelodysplasia-Related Changes. Oncologist 2020, 25, e1414–e1420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lancet, J.E.; Uy, G.L.; Cortes, J.E.; Newell, L.F.; Lin, T.L.; Ritchie, E.K.; Stuart, R.K.; Strickland, S.A.; Hogge, D.; Solomon, S.R.; et al. CPX-351 (Cytarabine and Daunorubicin) Liposome for Injection Versus Conventional Cytarabine Plus Daunorubicin in Older Patients With Newly Diagnosed Secondary Acute Myeloid Leukemia. J. Clin. Oncol. 2018, 36, 2684–2692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.P.; Gerhard, B.; Harasym, T.O.; Mayer, L.D.; Hogge, D.E. Liposomal Encapsulation of a Synergistic Molar Ratio of Cytarabine and Daunorubicin Enhances Selective Toxicity for Acute Myeloid Leukemia Progenitors as Compared to Analogous Normal Hematopoietic Cells. Exp. Hematol. 2011, 39, 741–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pourrajab, F.; Zare-Khormizi, M.R.; Hekmatimoghaddam, S.; Hashemi, A.S. Molecular Targeting and Rational Chemotherapy in Acute Myeloid Leukemia. J. Exp. Pharmacol. 2020, 12, 107–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konstantinidis, I.; Tsokkou, S.; Grigoriadis, S.; Chrysavgi, L.; Gavriilaki, E. Cardiotoxicity in Acute Myeloid Leukemia in Adults: A Scoping Study. Cancers 2024, 16, 2474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abstracts of the 59th Annual Scientific Meeting of the British Society for Hematology, 1-3 April 2019, Glasgow, UK. Br. J. Haematol. 2019, 185, 3–202. [CrossRef]

- Feldman, E.J.; Kolitz, J.E.; Trang, J.M.; Liboiron, B.D.; Swenson, C.E.; Chiarella, M.T.; Mayer, L.D.; Louie, A.C.; Lancet, J.E. Pharmacokinetics of CPX-351; a Nano-Scale Liposomal Fixed Molar Ratio Formulation of Cytarabine:Daunorubicin, in Patients with Advanced Leukemia. Leuk. Res. 2012, 36, 1283–1289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sasine, J.P.; Schiller, G.J. Emerging Strategies for High-Risk and Relapsed/Refractory Acute Myeloid Leukemia: Novel Agents and Approaches Currently in Clinical Trials. Blood Rev. 2015, 29, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jerez, J.; Hernandez, C.; Hill, C.N. Understanding Therapy-Related AML: Genetic Insights and Emerging Strategies for High-Risk Patients. Front. Hematol. 2025, 4, 1609642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cortes, J.E.; Lin, T.L.; Asubonteng, K.; Faderl, S.; Lancet, J.E.; Prebet, T. Efficacy and Safety of CPX-351 versus 7 + 3 Chemotherapy by European LeukemiaNet 2017 Risk Subgroups in Older Adults with Newly Diagnosed, High-Risk/Secondary AML: Post Hoc Analysis of a Randomized, Phase 3 Trial. J. Hematol. Oncol. 2022, 15, 155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montalban-Bravo, G.; Jabbour, E.; Borthakur, G.; Kadia, T.; Ravandi, F.; Chien, K.; Pemmaraju, N.; Hammond, D.; Dong, X.Q.; Huang, X.; et al. Phase 1/2 Study of CPX-351 for Patients with Int-2 or High Risk International Prognostic Scoring System Myelodysplastic Syndromes and Chronic Myelomonocytic Leukaemia after Failure to Hypomethylating Agents. Br. J. Haematol. 2024, 204, 898–909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrews, C.; Pullarkat, V.; Recher, C. CPX-351 in FLT3-Mutated Acute Myeloid Leukemia. Front. Oncol. 2023, 13, 1271722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peterlin, P.; Le Bris, Y.; Turlure, P.; Chevallier, P.; Ménard, A.; Gourin, M.-P.; Dumas, P.-Y.; Thepot, S.; Berceanu, A.; Park, S.; et al. CPX-351 in Higher Risk Myelodysplastic Syndrome and Chronic Myelomonocytic Leukaemia: A Multicentre, Single-Arm, Phase 2 Study. Lancet Haematol. 2023, 10, e521–e529, Correction in Lancet Haematol. 2023, 10, e708. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2352-3026(23)00245-4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vincelette, N.D.; Ding, H.; Huehls, A.M.; Flatten, K.S.; Kelly, R.L.; Kohorst, M.A.; Webster, J.; Hess, A.D.; Pratz, K.W.; Karnitz, L.M.; et al. Effect of CHK1 Inhibition on CPX-351 Cytotoxicity in Vitro and Ex Vivo. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 3617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blair, H.A. Daunorubicin/Cytarabine Liposome: A Review in Acute Myeloid Leukaemia. Drugs 2018, 78, 1903–1910, Correction in Drugs 2018, 78, 1911. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40265-018-1034-z. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Study | Population | Setting | Dosing | Efficacy | Survival Outcomes | Safety Profile | Notable Insights |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Feldman et al., 2011 (Phase I) [18] | 48 patients (43 AML, relapsed/refractory) | First-in-human dose escalation | Days 1, 3, 5; MTD = 101 u/m2 | 23% CR/CRp in AML; responses at ≥32 u/m2 | Median remission: 6.9 mo | DLTs: CHF, HTN crisis, prolonged cytopenias; rash in 71% | 5:1 ratio maintained ≥24 h; prolonged half-lives (Ara-C ~31 h, DNR ~22 h); active in heavily pretreated AML |

| Lancet et al., 2014 (Phase II) [19] | 126 older adults (60–75 years) with untreated AML | CPX-351 vs. 7 + 3 | CPX-351: 100 u/m2 (D1,3,5); consolidation allowed | CR/CRi: 66.7% vs. 51.2%; sAML CR/CRi: 57.6% vs. 31.6% | OS: 14.7 vs. 12.99 mo; sAML OS: 12.1 vs. 6.19 mo (HR 0.46) | Slower ANC/platelet recovery; more grade 3–4 infections but lower 60-day mortality | CPX-351 reduced 60-day mortality (4.7% vs. 14.6%); improved OS and EFS in sAML; supports phase III development |

| Cortes et al., 2015 (Phase II) [20] | 125 adults (18–65 years) with first-relapse AML | CPX-351 vs. investigator’s choice salvage | CPX-351: 100 u/m2 (D1,3,5); consolidation allowed | CR/CRi: 49.4% vs. 40.9%; CR: 37% vs. 31.8% | OS: 8.5 vs. 6.3 mo; 1-year OS: 36% vs. 27%; poor-risk OS: 6.6 vs. 4.2 mo (HR 0.55, p = 0.02) | Similar early mortality; slower ANC/platelet recovery; infection-related AEs common | CPX-351 improved OS and EFS in poor-risk patients; liposomal delivery may bypass resistance mechanisms |

| Lancet et al., 2021 (Phase III) [21] | 309 older adults (60–75 years) with newly diagnosed sAML | CPX-351 vs. 7 + 3 induction | CPX-351: 100 u/m2 (D1,3,5); consolidation 65 u/m2 (D1,3) | CR/CRi: 47.7% vs. 33.3% (7 + 3); CR: 37.3% vs. 25.6% | OS: 9.56 vs. 5.95 mo (HR 0.69, p = 0.003); EFS: 2.53 vs. 1.31 mo | Comparable AE rates; longer cytopenias with CPX-351 | OS benefit across age/subtypes; higher HCT rate (34% vs. 25%); supports CPX-351 as new standard in sAML |

| Krauss et al., 2019 (FDA Approval) [22] | 309 patients (60–75 years) with t-AML or AML-MRC | Regulatory review of Study 301 | CPX-351: 100 u/m2 (D1,3,5); consolidation 65 u/m2 (D1,3) | CR: 38% vs. 26% (7 + 3) | OS: 9.6 vs. 5.9 mo (HR 0.69, p = 0.005); OS in t-AML: HR 0.48; AML-MRC: HR 0.70 | Similar AE profile to 7 + 3; more prolonged cytopenias and bleeding risk | First FDA-approved therapy for t-AML/AML-MRC; boxed warnings for copper load, cytopenias, and formulation interchangeability |

| Issa et al., 2020 (Phase II) [23] | 56 high-risk AML patients (median age 69) | Newly diagnosed AML with high induction mortality risk | 50, 75, 100 u/m2 on days 1, 3, 5 | CR/CRi: 19% (50), 38% (75), 44% (100) | OS: 4.3 (50), 8.6 (75), 6.2 mo (100) | TEAEs: FN (34%), pneumonia (23%), sepsis (16%) | 75 u/m2 had best efficacy/safety balance; TP53 mutation = poor OS (2.6 mo); supports use in frail patients |

| Kolitz et al., 2020 (Consolidation) [24] | 81 patients with CR/CRi post-induction | CPX-351 vs. 7 + 3/5 + 2 consolidation | CPX-351: 65 u/m2 (D1,3); 5 + 2: cytarabine + daunorubicin | OS: 25.4 vs. 8.5 mo (HR 0.44); OS post-HCT: NR vs. 9.8 mo; OS without HCT: 13.7 vs. 8.4 mo | No deaths during consolidation; relapse rates lower with CPX-351 | TEAEs: FN (29%), pneumonia (8%), cellulitis (8%); slower ANC/platelet recovery | CPX-351 consolidation extended OS; outpatient delivery feasible in 51–61%; supports full-cycle CPX-351 strategy |

| Lin et al., 2021 (Post Hoc) [25] | Subgroup of 125 patients who achieved CR/CRi in Lancet trial | Exploratory analysis of remission impact | Same as Lancet (induction + consolidation) | CR/CRi: 48% (CPX-351) vs. 33% (7 + 3); CR: 37% vs. 26% | OS: 25.4 vs. 10.4 mo (HR 0.49); OS in t-AML: not reached vs. 9.15 mo (HR 0.21); OS in AML-MRC: 19.2 vs. 11.0 mo | Safety profile consistent with 7 + 3; longer cytopenias | CPX-351 led to deeper remissions and longer OS across subgroups, even without HCT; supports durable benefit in responders |

| Othman et al., 2023 (AML19 Trial) [26] | 189 younger adults (<60 years) with adverse karyotype AML or high-risk MDS | CPX-351 vs. FLAG-Ida | CPX-351: 2 induction + 2 consolidation cycles; FLAG-Ida: fludarabine, cytarabine, idarubicin | CR/CRi: 64% vs. 76%; OS: 13.3 vs. 11.4 mo (NS); RFS: 22.1 vs. 8.35 mo (HR 0.58, p = 0.03) | OS not significantly different; RFS improved with CPX-351; more SCT in CR with CPX-351 | Comparable grade ≥ 3 toxicity; longer platelet recovery with CPX-351; less death in remission | CPX-351 improved RFS and OS in patients with MDS-related gene mutations (median OS: 38.4 vs. 16.3 mo); supports genomic stratification |

| Mehta et al., 2024 (CREST-UK) [27] | 147 UK patients with newly diagnosed t-AML or AML-MRC (38% < 60 years) | Real-world, multicenter, outpatient-capable | CPX-351: 100 u/m2 (induction), 65 u/m2 (consolidation) | CR/CRi: 53%; MRD negativity in 51% of tested responders | OS: 12.8 mo overall; 25.4 mo post-HCT; 14.0 mo in CR/CRi without HCT; OS in TP53-mutated: 4.5 mo | Grade ≥ 3 TEAEs in 75%; FN (38%), pneumonia (8%), sepsis (7%); cardiac TEAEs in 12% | Outpatient delivery feasible; reduced hospitalization days; OS benefit preserved across age and risk strata; TP53 mutation = poor prognosis |

| Cluzeau et al., 2025 (RWE) [28] | 168 adults with newly diagnosed t-AML or AML-MRC | Real-world, multicenter, long-term follow-up | CPX-351: 1–2 induction cycles; consolidation ± HSCT | CR/CRi: 60%; MRD negativity in 65% of tested responders | OS: 13.3 mo overall; OS with MRD < 10−3: 20.4 mo vs. 12.9 mo (p = 0.006); OS post-HCT: NR vs. 26 mo | Acceptable safety; MRD > 10−3 independently predicted poorer OS (HR 2.6) | MRD negativity strongly associated with improved OS |

| Parameter | Conventional Cytarabine (7 + 3) | CPX-351 (Vyxeos) |

|---|---|---|

| Induction Dose | 100 mg/m2/day | 100 units/m2 (cytarabine 100 mg/m2 + daunorubicin 44 mg/m2) |

| Induction Schedule | Daily for 7 consecutive days | Days 1, 3, and 5 (90 min infusion) |

| Route of Administration | Continuous IV infusion (standard); also, IV bolus, SC, or IT in specific contexts | IV infusion over 90 min |

| Consolidation Dose | Variable; may include high-dose cytarabine (1000–3000 mg/m2 per dose) | 65 units/m2 (cytarabine 65 mg/m2 + daunorubicin 29 mg/m2) |

| Consolidation Schedule | Depends on protocol; often multiple cycles | Days 1 and 3 (90 min infusion) |

| Intrathecal Use | Occasionally used for CNS prophylaxis or treatment | Not used intrathecally |

| Formulation | Free cytarabine | Liposomal encapsulation of fixed 5:1 molar ratio of cytarabine and daunorubicin |

| Features | Conventional Chemotherapy (7 + 3) | CPX-351 (Liposomal Cytarabine/Daunorubicin) |

|---|---|---|

| Drug Formulation | Free cytarabine + daunorubicin | Liposomal cytarabine + daunorubicin (5:1) |

| Indication | All AML subtypes, especially de novo AML | High-risk/secondary AML (AML-MRC, t-AML) |

| Dosing (Induction) | Cytarabine 100 mg/m2/day × 7 days (CI) + daunorubicin 60 mg/m2/day × 3 days (IV) | 100 units/m2 IV over 90 min on days 1, 3, 5 (cycle 1); days 1, 3 (cycle 2) |

| Dosing (Consolidation) | 5 + 2 regimen or intermediate/high-dose cytarabine | 65 units/m2 IV over 90 min on days 1, 3 |

| Median OS | 5.95–6.2 months | 9.33–10.3 months |

| 5-Year OS | 8% | 18% |

| Complete Remission Rate (CR/CRi) | 33–39% | 47–49% |

| HSCT Rate (Post-Remission) | Lower | Higher |

| Early Mortality (30-day) | 10.6% | 4.9–5.9% |

| Safety Profile | Myelosuppression, infection, cardiotoxicity | Similar myelosuppression, less cardiotoxicity, fewer infections |

| Recovery of Counts | Faster | Slower |

| Special Populations | All AML, including younger adults | Older adults (60–75) with AML-MRC/t-AML |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Konstantinidis, I.; Tsokkou, S.; Keramas, A.; Gavriilaki, E.; Delis, G.; Papamitsou, T. CPX-351 and the Frontier of Nanoparticle-Based Therapeutics in Acute Myeloid Leukemia. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 11628. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311628

Konstantinidis I, Tsokkou S, Keramas A, Gavriilaki E, Delis G, Papamitsou T. CPX-351 and the Frontier of Nanoparticle-Based Therapeutics in Acute Myeloid Leukemia. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2025; 26(23):11628. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311628

Chicago/Turabian StyleKonstantinidis, Ioannis, Sophia Tsokkou, Antonios Keramas, Eleni Gavriilaki, Georgios Delis, and Theodora Papamitsou. 2025. "CPX-351 and the Frontier of Nanoparticle-Based Therapeutics in Acute Myeloid Leukemia" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 26, no. 23: 11628. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311628

APA StyleKonstantinidis, I., Tsokkou, S., Keramas, A., Gavriilaki, E., Delis, G., & Papamitsou, T. (2025). CPX-351 and the Frontier of Nanoparticle-Based Therapeutics in Acute Myeloid Leukemia. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 26(23), 11628. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311628