Emerging Roles of Post-Translational Modifications in Metabolic Homeostasis and Type 2 Diabetes

Abstract

1. Introduction

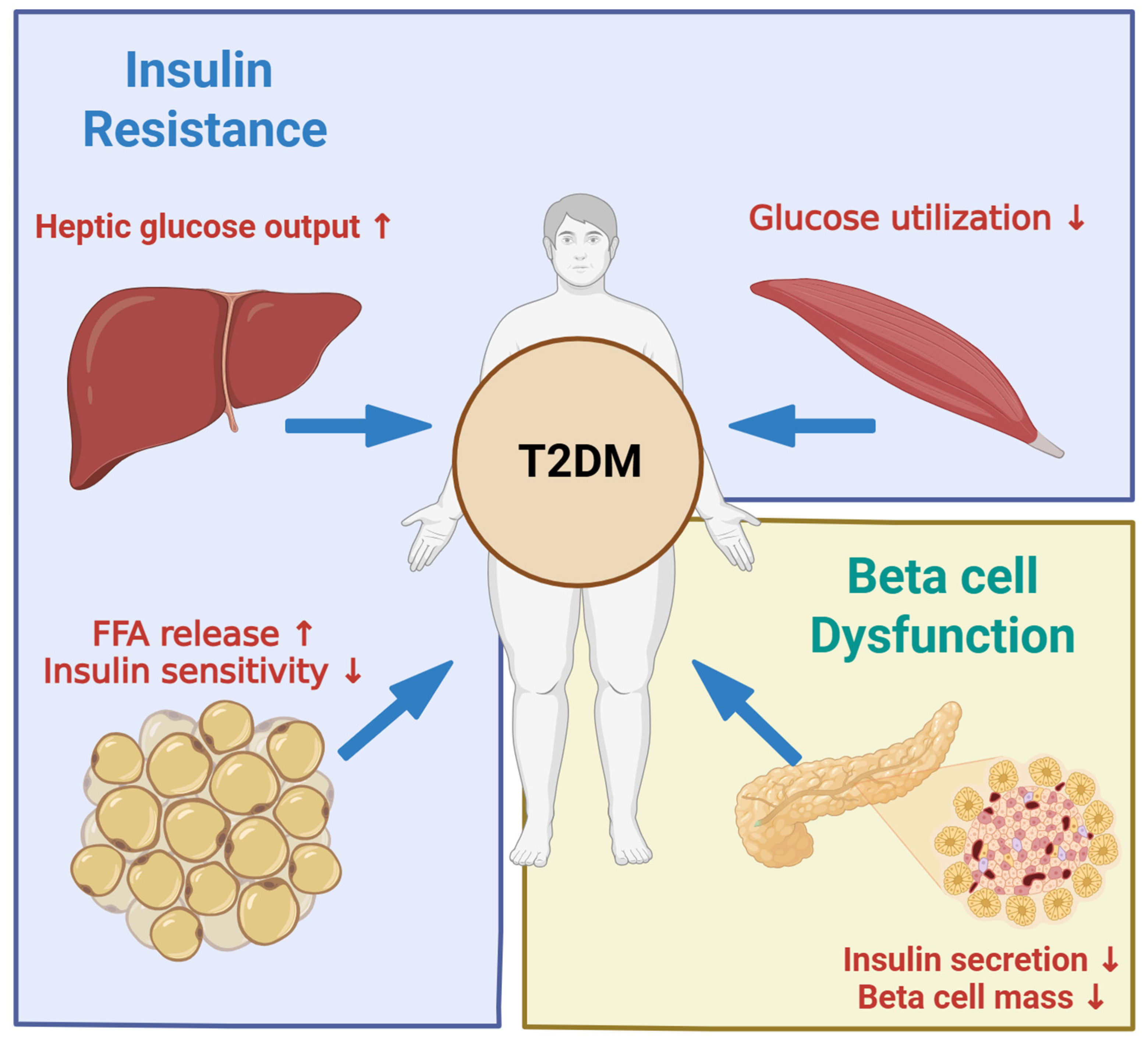

2. Pathophysiology of Type 2 Diabetes

2.1. Type 2 Diabetes

2.2. Insulin Resistance and Beta Cell Compensation

2.3. Beta Cell Failure

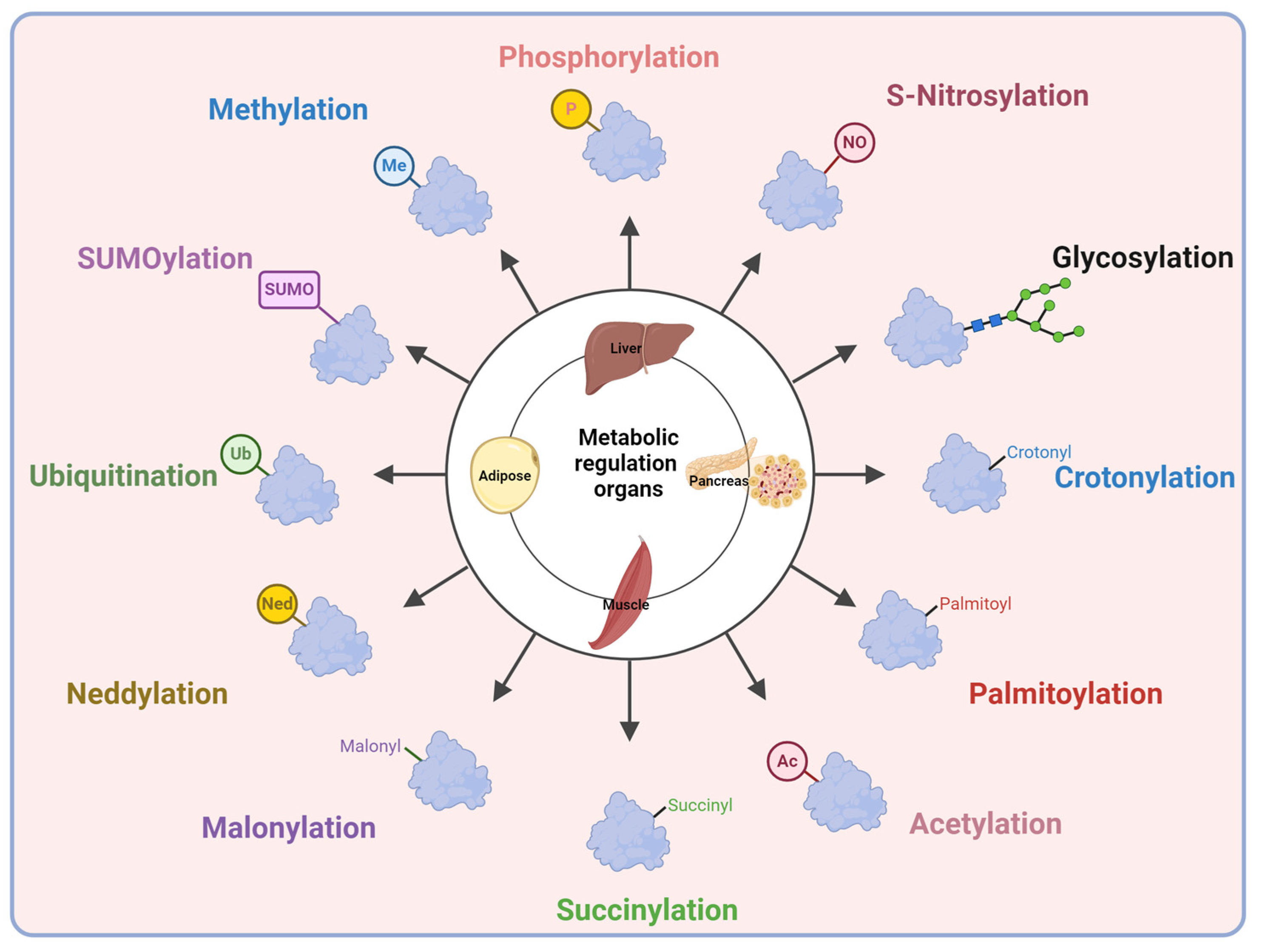

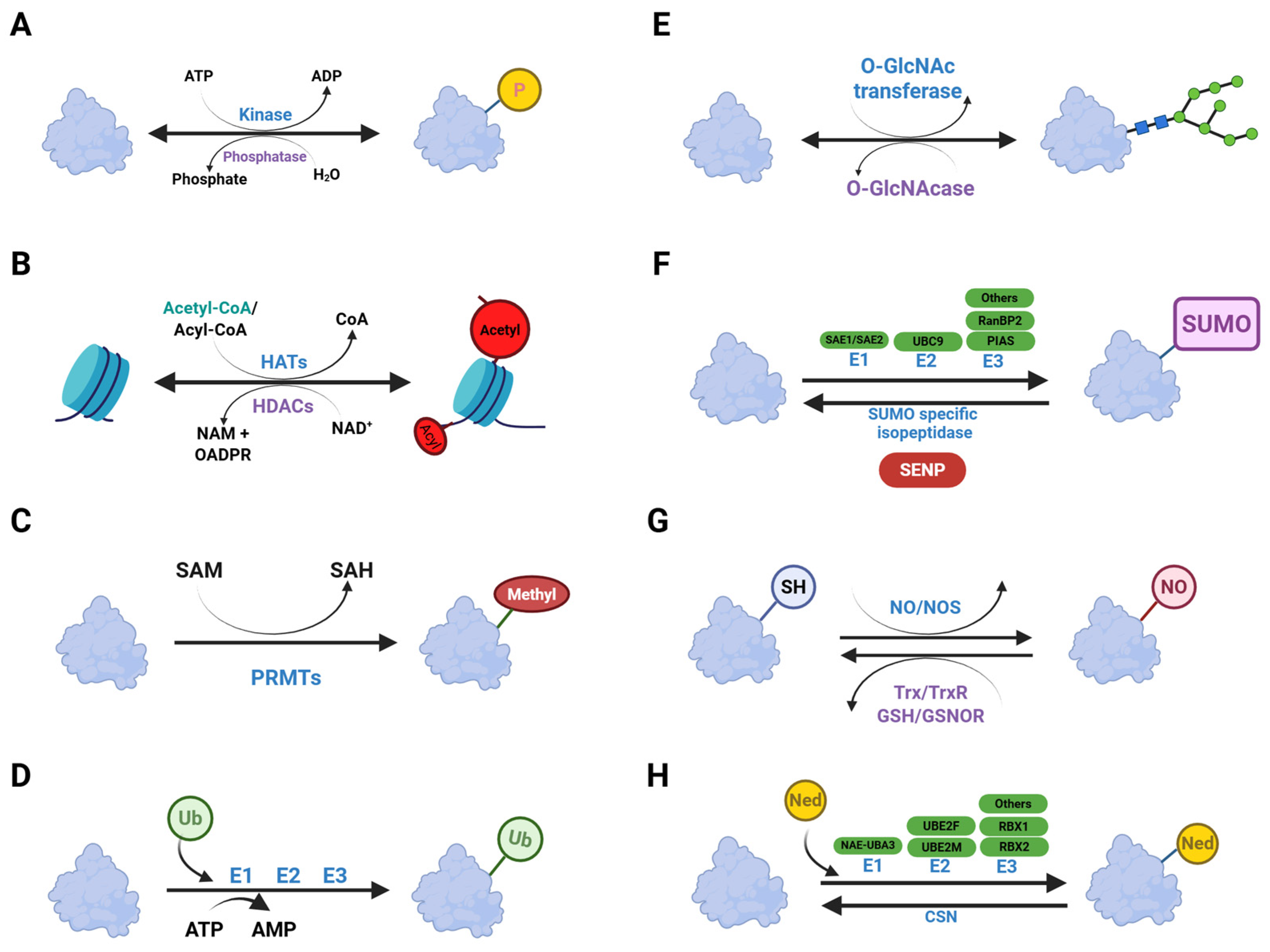

3. Post-Translational Modifications

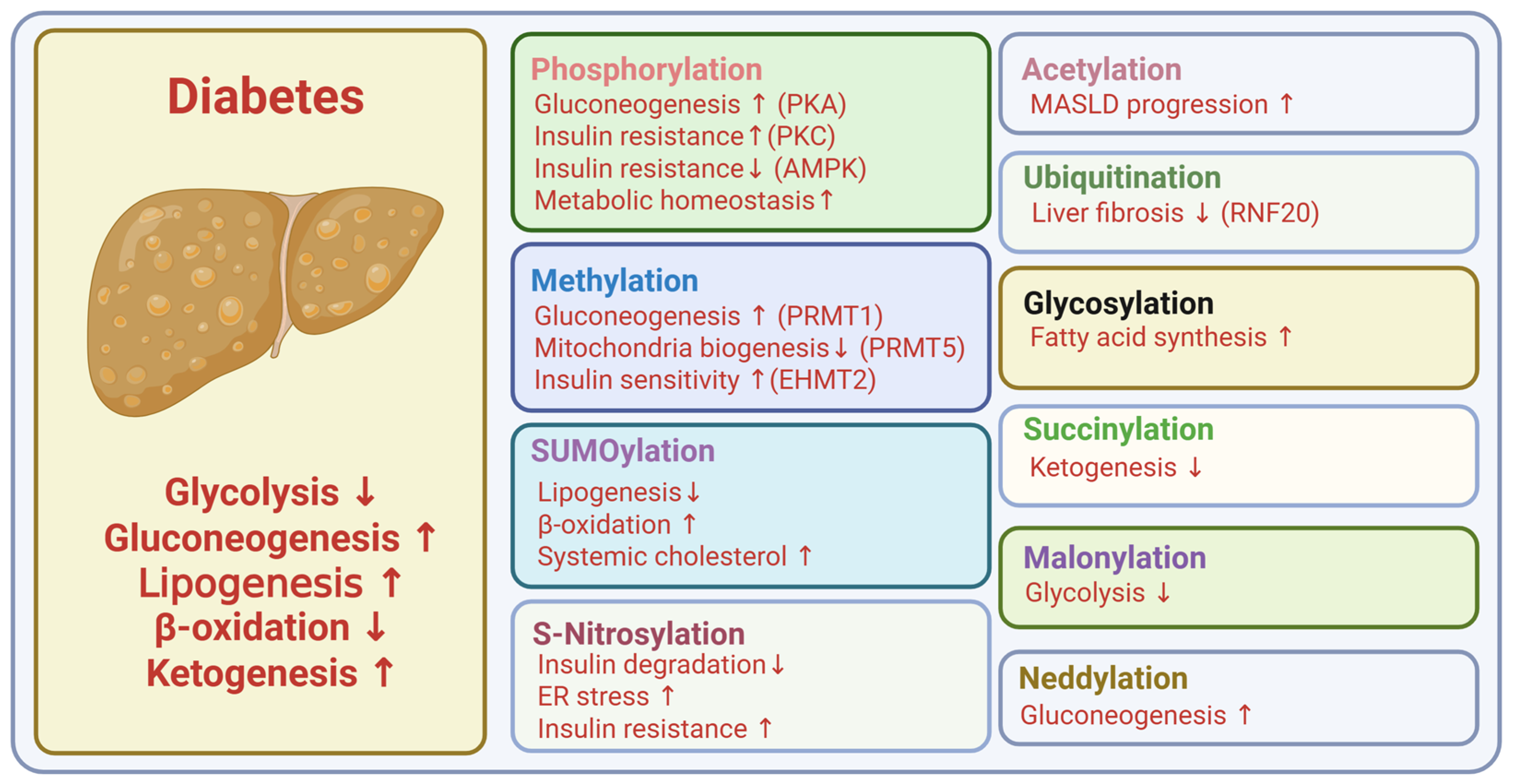

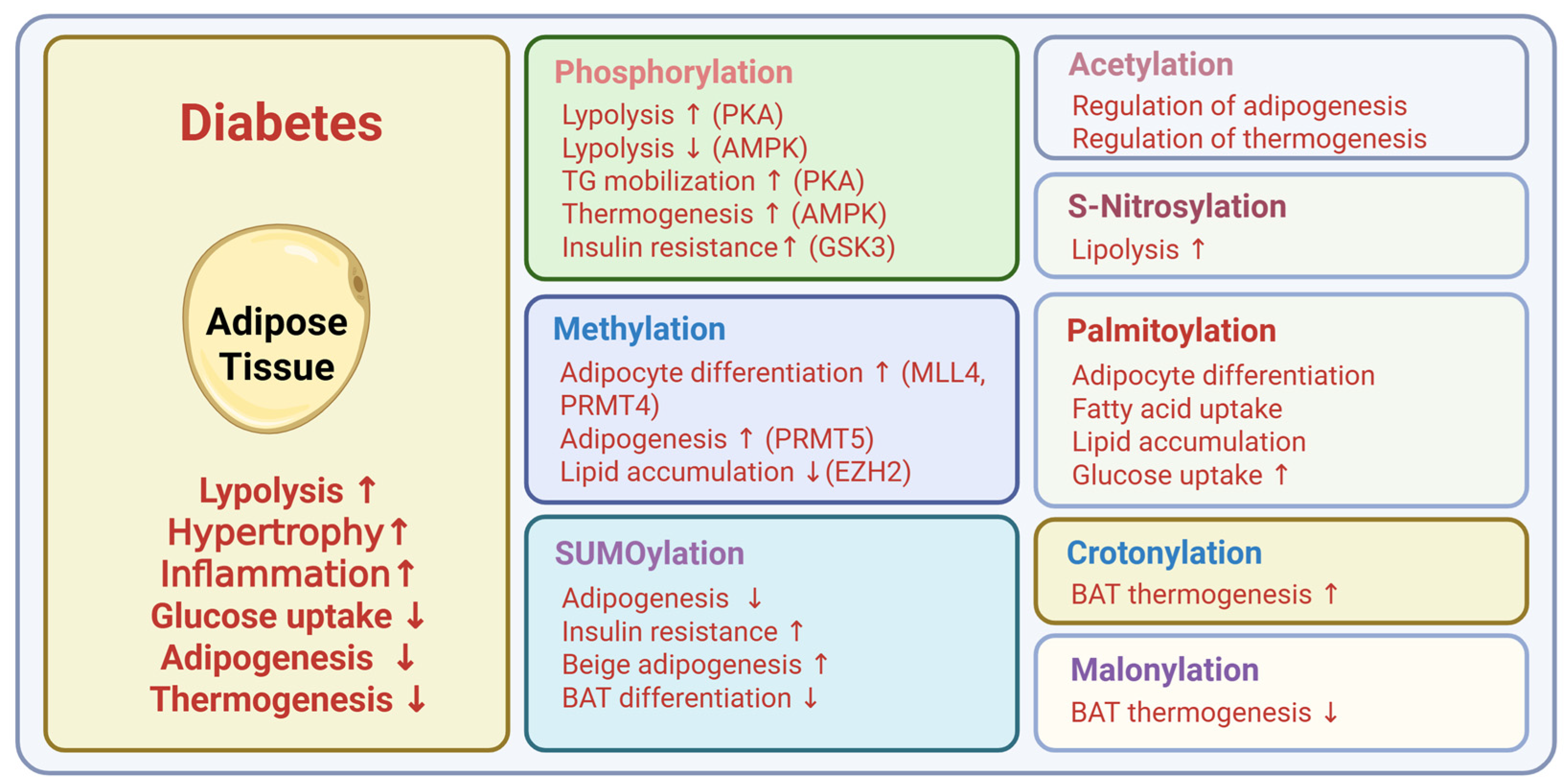

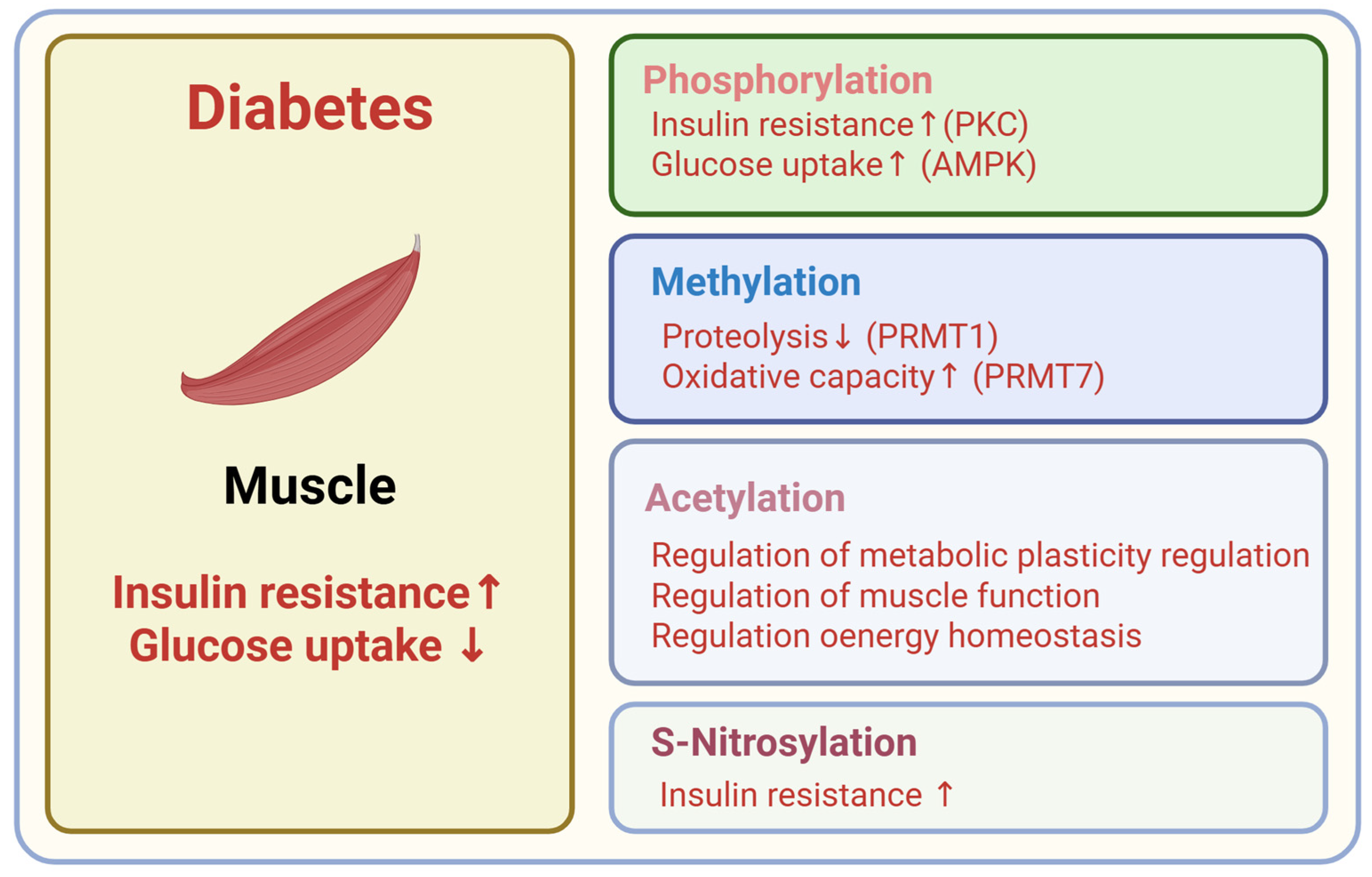

4. Post-Translational Modifications in Type 2 Diabetes

4.1. Phosphorylation

4.2. Acetylation

4.3. Methylation

4.4. Ubiquitination

4.5. Glycosylation

4.6. Acylation

4.7. SUMOylation

4.8. S-Nitrosylation

4.9. Neddylation

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AGEs | Advanced Glycation End products |

| AKT | Protein Kinase B |

| AMPK | AMP-activated Protein Kinase |

| APT1 | Acyl-protein thioesterase 1 |

| APT2 | Acyl-protein thioesterase 2 |

| CARM1 | Coactivator-associated arginine methyltransferase 1 |

| CD36 | Cluster of Differentiation 36 |

| ChREBP | Carbohydrate-Responsive Element-Binding Protein |

| CTCF | CCCTC-binding factor |

| DHHC7 | Zinc Finger DHHC-type Palmitoyltransferase 7 |

| eIF2a | Eukaryotic Translation Initiation Factor 2 alpha |

| EZH2 | Enhancer of zeste homolog 2 |

| FAS | Fatty Acid Synthase |

| FOXO | Forkhead box O |

| GK rats | Goto-Kakizaki rats |

| GLUT4 | Glucose Transporter Type 4 |

| GSIS | Glucose-Stimulated Insulin Secretion |

| GSK3 | Glycogen Synthase Kinase 3 |

| HATs | Histone Acetyl-Transferases |

| HCC | Hepatocellular Carcinoma |

| HDACs | Histone Deacetylases |

| HMGA1 | High Mobility Group A1 |

| IGF-1 | Insulin-like growth factor 1 |

| IRS-1 | Insulin Receptor Substrate 1 |

| KDM1A/B | Lysine Specific Histone Demethylase 1A/B |

| LncRNA-NEAT1 | Nuclear Paraspeckle Assembly Transcript 1 |

| MafA | v-maf musculoaponeurotic fibrosarcoma oncogene homolog A |

| MARK2 | MAP/Microtuble Affinity-Regulating Kinase 2 |

| MARK3 | MAP/Microtuble Affinity-Regulating Kinase 3 |

| MASLD | Metabolic Dysfunction-Associated Steatotic Liver Disease |

| MINDY1 | MINDY Lysine 48 deubiquitinase 1 |

| MIP-CreERT | Mouse Insulin 1 Promoter-Cre-ERT |

| MLL4 | Mixed-lineage leukemia 4 |

| mTOR | Mechanistic Target of Rapamycin |

| NR4A1 | Nuclear Receptor Subfamily 4, group A, Member 1 |

| OGT | O-GlcNAc Transferase |

| PDE3B | Phosphodiesterase 3B |

| PDX1 | Pancreatic and Duodenal Homeobox 1 |

| PERK | Protein Kinase R-like ER Kinase |

| PGC1-a | Peroxisome Proliferator-activated receptor gamma coactivator 1- alpha |

| PKA | Protein Kinase A |

| PKC | Protein Kinase C |

| PNPLA3 | Patatin-like phospholipase domain-containing 3 |

| PPARγ | Peroxisome Proliferator-Activated Receptor gamma |

| PRMTs | Protein Arginine Methyltransferases |

| PTM | Post Translation Modification |

| RIP-Cre | Rat Insulin Promoter-Cre |

| RNF20 | Ring Finger Protein 20 |

| Rpd3 | Reduced Potassium Dependency 3 |

| SCAN | Biliverdin Reductase B |

| SCD | Stearoyl-CoA Desaturase |

| SENP1 | SUMO-specific peptidase 1 |

| SETD7 | SET domain-containing lysine methyltransferase 7 |

| SIRTs | Sirtuins |

| SNAP-25 | Synaptosome-associated Protein 25 |

| SREBP1c | Sterol Regulatory Element-Binding Protein 1c |

| TGF-β | Transforming Growth Factor beta |

| TNFα | Tumor Necrosis Factor alpha |

| TSC2 | Tuberous sclerosis complex 2 |

| UCP-1 | Uncoupling Protein 1 |

| ULK1 | Unc-51 Like Autophagy Activating Kinase 1 |

| UPR | Unfolded Protein Response |

| USP2A | Ubiquitin-specific Protease 2a |

| VAMP2 | Vesicle-associated membrane protein 2 |

| VEGFA | Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor A |

| zDHHC | Zinc fingers DHHC-type |

| ZDHHC21 | Zinc Finger DHHC-type Palmitoyltransferase 21 |

References

- Campbell, J.E.; Newgard, C.B. Mechanisms controlling pancreatic islet cell function in insulin secretion. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2021, 22, 142–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.K.; Sussel, L.; Davidson, H.W. Inherent Beta Cell Dysfunction Contributes to Autoimmune Susceptibility. Biomolecules 2021, 11, 512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brereton, M.F.; Rohm, M.; Ashcroft, F.M. beta-Cell dysfunction in diabetes: A crisis of identity? Diabetes Obes. Metab. 2016, 18 (Suppl. S1), 102–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Y.H.; Wen, R.; Yang, N.; Zhang, T.N.; Liu, C.F. Roles of protein post-translational modifications in glucose and lipid metabolism: Mechanisms and perspectives. Mol. Med. 2023, 29, 93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uy, R.; Wold, F. Posttranslational covalent modification of proteins. Science 1977, 198, 890–896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.M.; Hammaren, H.M.; Savitski, M.M.; Baek, S.H. Control of protein stability by post-translational modifications. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, C.; Hamza, A.; Boyle, E.; Donu, D.; Cen, Y. Post-Translational Modifications and Diabetes. Biomolecules 2024, 14, 310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McLaughlin, R.J.; Spindler, M.P.; van Lummel, M.; Roep, B.O. Where, How, and When: Positioning Posttranslational Modification Within Type 1 Diabetes Pathogenesis. Curr. Diabetes Rep. 2016, 16, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.; Wei, M.; Zhao, Y.; Yang, Z.; Song, M.; Mi, J.; Yang, X.; Tian, G. Regulation of insulin secretion by the post-translational modifications. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2023, 11, 1217189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doll, S.; Gnad, F.; Mann, M. The Case for Proteomics and Phospho-Proteomics in Personalized Cancer Medicine. Proteom. Clin. Appl. 2019, 13, e1800113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aslam, B.; Basit, M.; Nisar, M.A.; Khurshid, M.; Rasool, M.H. Proteomics: Technologies and Their Applications. J. Chromatogr. Sci. 2017, 55, 182–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, Y.; Sandow, J.J.; Czabotar, P.E.; Murphy, J.M. The regulation of necroptosis by post-translational modifications. Cell Death Differ. 2021, 28, 861–883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patwardhan, A.; Cheng, N.; Trejo, J. Post-Translational Modifications of G Protein-Coupled Receptors Control Cellular Signaling Dynamics in Space and Time. Pharmacol. Rev. 2021, 73, 120–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; Liu, J.; Liu, C.; Liu, R.; Liu, L.; Yu, Z.; Zhuang, J.; Sun, C. Post-Translational Modifications of cGAS-STING: A Critical Switch for Immune Regulation. Cells 2022, 11, 3043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collaboration, N.C.D.R.F. Worldwide trends in diabetes prevalence and treatment from 1990 to 2022: A pooled analysis of 1108 population-representative studies with 141 million participants. Lancet 2024, 404, 2077–2093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, R. Understanding the cause of type 2 diabetes. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2024, 12, 664–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, X.; Xie, Q.; Pan, X.; Zhang, R.; Zhang, X.; Peng, G.; Zhang, Y.; Shen, S.; Tong, N. Type 2 diabetes mellitus in adults: Pathogenesis, prevention and therapy. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2024, 9, 262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galicia-Garcia, U.; Benito-Vicente, A.; Jebari, S.; Larrea-Sebal, A.; Siddiqi, H.; Uribe, K.B.; Ostolaza, H.; Martin, C. Pathophysiology of Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 6275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zakir, M.; Ahuja, N.; Surksha, M.A.; Sachdev, R.; Kalariya, Y.; Nasir, M.; Kashif, M.; Shahzeen, F.; Tayyab, A.; Khan, M.S.M.; et al. Cardiovascular Complications of Diabetes: From Microvascular to Macrovascular Pathways. Cureus 2023, 15, e45835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tomic, D.; Shaw, J.E.; Magliano, D.J. The burden and risks of emerging complications of diabetes mellitus. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 2022, 18, 525–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Forbes, J.M.; Cooper, M.E. Mechanisms of diabetic complications. Physiol. Rev. 2013, 93, 137–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.H.; Park, S.Y.; Choi, C.S. Insulin Resistance: From Mechanisms to Therapeutic Strategies. Diabetes Metab. J. 2022, 46, 15–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein, S.; Gastaldelli, A.; Yki-Jarvinen, H.; Scherer, P.E. Why does obesity cause diabetes? Cell Metab. 2022, 34, 11–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawai, T.; Autieri, M.V.; Scalia, R. Adipose tissue inflammation and metabolic dysfunction in obesity. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 2021, 320, C375–C391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apostolova, N.; Vezza, T.; Muntane, J.; Rocha, M.; Victor, V.M. Mitochondrial Dysfunction and Mitophagy in Type 2 Diabetes: Pathophysiology and Therapeutic Targets. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2023, 39, 278–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen-Cody, S.O.; Potthoff, M.J. Hepatokines and metabolism: Deciphering communication from the liver. Mol. Metab. 2021, 44, 101138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Inaishi, J.; Saisho, Y. Beta-Cell Mass in Obesity and Type 2 Diabetes, and Its Relation to Pancreas Fat: A Mini-Review. Nutrients 2020, 12, 3846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerf, M.E. Beta cell dysfunction and insulin resistance. Front. Endocrinol. 2013, 4, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golson, M.L.; Misfeldt, A.A.; Kopsombut, U.G.; Petersen, C.P.; Gannon, M. High Fat Diet Regulation of beta-Cell Proliferation and beta-Cell Mass. Open Endocrinol. J. 2010, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, W.J.; Peng, Y.C.; Yang, K.M. Cellular signaling pathways regulating beta-cell proliferation as a promising therapeutic target in the treatment of diabetes. Exp. Ther. Med. 2018, 16, 3275–3285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sachdeva, M.M.; Claiborn, K.C.; Khoo, C.; Yang, J.; Groff, D.N.; Mirmira, R.G.; Stoffers, D.A. Pdx1 (MODY4) regulates pancreatic beta cell susceptibility to ER stress. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2009, 106, 19090–19095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, D.B.; Lavine, J.A.; Suhonen, J.I.; Krautkramer, K.A.; Rabaglia, M.E.; Sperger, J.M.; Fernandez, L.A.; Yandell, B.S.; Keller, M.P.; Wang, I.M.; et al. FoxM1 is up-regulated by obesity and stimulates beta-cell proliferation. Mol. Endocrinol. 2010, 24, 1822–1834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wysham, C.; Shubrook, J. Beta-cell failure in type 2 diabetes: Mechanisms, markers, and clinical implications. Postgrad. Med. 2020, 132, 676–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halban, P.A.; Polonsky, K.S.; Bowden, D.W.; Hawkins, M.A.; Ling, C.; Mather, K.J.; Powers, A.C.; Rhodes, C.J.; Sussel, L.; Weir, G.C. beta-cell failure in type 2 diabetes: Postulated mechanisms and prospects for prevention and treatment. Diabetes Care 2014, 37, 1751–1758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.H.; Lee, J. Endoplasmic Reticulum (ER) Stress and Its Role in Pancreatic beta-Cell Dysfunction and Senescence in Type 2 Diabetes. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 4843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fonseca, S.G.; Gromada, J.; Urano, F. Endoplasmic reticulum stress and pancreatic beta-cell death. Trends Endocrinol. Metab. 2011, 22, 266–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dludla, P.V.; Mabhida, S.E.; Ziqubu, K.; Nkambule, B.B.; Mazibuko-Mbeje, S.E.; Hanser, S.; Basson, A.K.; Pheiffer, C.; Kengne, A.P. Pancreatic beta-cell dysfunction in type 2 diabetes: Implications of inflammation and oxidative stress. World J. Diabetes 2023, 14, 130–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fex, M.; Nicholas, L.M.; Vishnu, N.; Medina, A.; Sharoyko, V.V.; Nicholls, D.G.; Spegel, P.; Mulder, H. The pathogenetic role of beta-cell mitochondria in type 2 diabetes. J. Endocrinol. 2018, 236, R145–R159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talchai, C.; Xuan, S.; Lin, H.V.; Sussel, L.; Accili, D. Pancreatic beta cell dedifferentiation as a mechanism of diabetic beta cell failure. Cell 2012, 150, 1223–1234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cinti, F.; Bouchi, R.; Kim-Muller, J.Y.; Ohmura, Y.; Sandoval, P.R.; Masini, M.; Marselli, L.; Suleiman, M.; Ratner, L.E.; Marchetti, P.; et al. Evidence of beta-Cell Dedifferentiation in Human Type 2 Diabetes. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2016, 101, 1044–1054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bensellam, M.; Jonas, J.C.; Laybutt, D.R. Mechanisms of beta-cell dedifferentiation in diabetes: Recent findings and future research directions. J. Endocrinol. 2018, 236, R109–R143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strahl, B.D.; Allis, C.D. The language of covalent histone modifications. Nature 2000, 403, 41–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunter, T. The age of crosstalk: Phosphorylation, ubiquitination, and beyond. Mol. Cell 2007, 28, 730–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suskiewicz, M.J. The logic of protein post-translational modifications (PTMs): Chemistry, mechanisms and evolution of protein regulation through covalent attachments. Bioessays 2024, 46, e2300178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deribe, Y.L.; Pawson, T.; Dikic, I. Post-translational modifications in signal integration. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2010, 17, 666–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhong, Q.; Xiao, X.; Qiu, Y.; Xu, Z.; Chen, C.; Chong, B.; Zhao, X.; Hai, S.; Li, S.; An, Z.; et al. Protein posttranslational modifications in health and diseases: Functions, regulatory mechanisms, and therapeutic implications. MedComm 2023, 4, e261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Chi, X.; Wang, Y.; Setrerrahmane, S.; Xie, W.; Xu, H. Trends in insulin resistance: Insights into mechanisms and therapeutic strategy. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2022, 7, 216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Houtkooper, R.H.; Pirinen, E.; Auwerx, J. Sirtuins as regulators of metabolism and healthspan. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2012, 13, 225–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hershko, A.; Ciechanover, A. The ubiquitin system. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 1998, 67, 425–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruan, H.B.; Singh, J.P.; Li, M.D.; Wu, J.; Yang, X. Cracking the O-GlcNAc code in metabolism. Trends Endocrinol. Metab. 2013, 24, 301–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jo, S.; Esch, N.; Nguyen, A.; Wong, A.; Mohan, R.; Kim, C.; Blandino-Rosano, M.; Bernal-Mizrachi, E.; Alejandro, E.U. Loss of O-GlcNAcylation modulates mTORC1 and autophagy in beta cells, driving diabetes 2 progression. JCI Insight 2024, 9, e183033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ernst, R.; Ballweg, S.; Levental, I. Corrigendum to “Cellular mechanisms of physicochemical membrane homeostasis” [Curr Opin Cell Biol (2018) 44-51]. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 2020, 63, 212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, I.; Conrad, R.J.; Verdin, E.; Ott, M. Lysine Acetylation Goes Global: From Epigenetics to Metabolism and Therapeutics. Chem. Rev. 2018, 118, 1216–1252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gupta, R.; Sahu, M.; Srivastava, D.; Tiwari, S.; Ambasta, R.K.; Kumar, P. Post-translational modifications: Regulators of neurodegenerative proteinopathies. Ageing Res. Rev. 2021, 68, 101336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, P. The origins of protein phosphorylation. Nat. Cell Biol. 2002, 4, E127–E130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, P. The regulation of protein function by multisite phosphorylation--a 25 year update. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2000, 25, 596–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, P.; Cross, D.; Janne, P.A. Kinase drug discovery 20 years after imatinib: Progress and future directions. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2021, 20, 551–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rui, L. Energy metabolism in the liver. Compr. Physiol. 2014, 4, 177–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, H.S.; Kang, G.; Kim, J.S.; Choi, B.H.; Koo, S.H. Regulation of glucose metabolism from a liver-centric perspective. Exp. Mol. Med. 2016, 48, e218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altarejos, J.Y.; Montminy, M. CREB and the CRTC co-activators: Sensors for hormonal and metabolic signals. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2011, 12, 141–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Hu, L.; Dalen, K.; Dorward, H.; Marcinkiewicz, A.; Russell, D.; Gong, D.; Londos, C.; Yamaguchi, T.; Holm, C.; et al. Activation of hormone-sensitive lipase requires two steps, protein phosphorylation and binding to the PAT-1 domain of lipid droplet coat proteins. J. Biol. Chem. 2009, 284, 32116–32125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, W.; Daniel, K.W.; Robidoux, J.; Puigserver, P.; Medvedev, A.V.; Bai, X.; Floering, L.M.; Spiegelman, B.M.; Collins, S. p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase is the central regulator of cyclic AMP-dependent transcription of the brown fat uncoupling protein 1 gene. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2004, 24, 3057–3067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Collins, S. beta-Adrenoceptor Signaling Networks in Adipocytes for Recruiting Stored Fat and Energy Expenditure. Front. Endocrinol. 2011, 2, 102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rorsman, P.; Ashcroft, F.M. Pancreatic beta-Cell Electrical Activity and Insulin Secretion: Of Mice and Men. Physiol. Rev. 2018, 98, 117–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehta, K.D. Emerging role of protein kinase C in energy homeostasis: A brief overview. World J. Diabetes 2014, 5, 385–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samuel, V.T.; Liu, Z.X.; Wang, A.; Beddow, S.A.; Geisler, J.G.; Kahn, M.; Zhang, X.M.; Monia, B.P.; Bhanot, S.; Shulman, G.I. Inhibition of protein kinase Cepsilon prevents hepatic insulin resistance in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. J. Clin. Investig. 2007, 117, 739–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szendroedi, J.; Yoshimura, T.; Phielix, E.; Koliaki, C.; Marcucci, M.; Zhang, D.; Jelenik, T.; Muller, J.; Herder, C.; Nowotny, P.; et al. Role of diacylglycerol activation of PKCtheta in lipid-induced muscle insulin resistance in humans. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2014, 111, 9597–9602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bezy, O.; Tran, T.T.; Pihlajamaki, J.; Suzuki, R.; Emanuelli, B.; Winnay, J.; Mori, M.A.; Haas, J.; Biddinger, S.B.; Leitges, M.; et al. PKCdelta regulates hepatic insulin sensitivity and hepatosteatosis in mice and humans. J. Clin. Investig. 2011, 121, 2504–2517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Greene, M.W.; Burrington, C.M.; Lynch, D.T.; Davenport, S.K.; Johnson, A.K.; Horsman, M.J.; Chowdhry, S.; Zhang, J.; Sparks, J.D.; Tirrell, P.C. Lipid metabolism, oxidative stress and cell death are regulated by PKC delta in a dietary model of nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e85848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehta, D.; Mehta, K.D. PKCbeta: Expanding role in hepatic adaptation of cholesterol homeostasis to dietary fat/cholesterol. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 2017, 312, G266–G273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trexler, A.J.; Taraska, J.W. Regulation of insulin exocytosis by calcium-dependent protein kinase C in beta cells. Cell Calcium 2017, 67, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grahame Hardie, D. AMP-activated protein kinase: A key regulator of energy balance with many roles in human disease. J. Intern. Med. 2014, 276, 543–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gwinn, D.M.; Shackelford, D.B.; Egan, D.F.; Mihaylova, M.M.; Mery, A.; Vasquez, D.S.; Turk, B.E.; Shaw, R.J. AMPK phosphorylation of raptor mediates a metabolic checkpoint. Mol. Cell 2008, 30, 214–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, M.; Klionsky, D.J. AMPK-dependent phosphorylation of ULK1 induces autophagy. Cell Metab. 2011, 13, 119–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viollet, B.; Foretz, M.; Guigas, B.; Horman, S.; Dentin, R.; Bertrand, L.; Hue, L.; Andreelli, F. Activation of AMP-activated protein kinase in the liver: A new strategy for the management of metabolic hepatic disorders. J. Physiol. 2006, 574, 41–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinberg, G.R.; Carling, D. AMP-activated protein kinase: The current landscape for drug development. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2019, 18, 527–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Woods, A.; Williams, J.R.; Muckett, P.J.; Mayer, F.V.; Liljevald, M.; Bohlooly, Y.M.; Carling, D. Liver-Specific Activation of AMPK Prevents Steatosis on a High-Fructose Diet. Cell Rep. 2017, 18, 3043–3051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boudaba, N.; Marion, A.; Huet, C.; Pierre, R.; Viollet, B.; Foretz, M. AMPK Re-Activation Suppresses Hepatic Steatosis but its Downregulation Does Not Promote Fatty Liver Development. EBioMedicine 2018, 28, 194–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kjobsted, R.; Hingst, J.R.; Fentz, J.; Foretz, M.; Sanz, M.N.; Pehmoller, C.; Shum, M.; Marette, A.; Mounier, R.; Treebak, J.T.; et al. AMPK in skeletal muscle function and metabolism. FASEB J. 2018, 32, 1741–1777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Vaart, J.I.; Boon, M.R.; Houtkooper, R.H. The Role of AMPK Signaling in Brown Adipose Tissue Activation. Cells 2021, 10, 1122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Q.; Liang, X.; Sun, X.; Zhang, L.; Fu, X.; Rogers, C.J.; Berim, A.; Zhang, S.; Wang, S.; Wang, B.; et al. AMPK/alpha-Ketoglutarate Axis Dynamically Mediates DNA Demethylation in the Prdm16 Promoter and Brown Adipogenesis. Cell Metab. 2016, 24, 542–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daval, M.; Foufelle, F.; Ferre, P. Functions of AMP-activated protein kinase in adipose tissue. J. Physiol. 2006, 574, 55–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anthony, N.M.; Gaidhu, M.P.; Ceddia, R.B. Regulation of visceral and subcutaneous adipocyte lipolysis by acute AICAR-induced AMPK activation. Obesity 2009, 17, 1312–1317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- da Silva Xavier, G.; Leclerc, I.; Varadi, A.; Tsuboi, T.; Moule, S.K.; Rutter, G.A. Role for AMP-activated protein kinase in glucose-stimulated insulin secretion and preproinsulin gene expression. Biochem. J. 2003, 371, 761–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, A.; Eberhard, C.E.; Screaton, R.A. Role of AMPK in pancreatic beta cell function. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 2013, 366, 127–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szkudelski, T.; Szkudelska, K. The relevance of AMP-activated protein kinase in insulin-secreting beta cells: A potential target for improving beta cell function? J. Physiol. Biochem. 2019, 75, 423–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sacco, F.; Seelig, A.; Humphrey, S.J.; Krahmer, N.; Volta, F.; Reggio, A.; Marchetti, P.; Gerdes, J.; Mann, M. Phosphoproteomics Reveals the GSK3-PDX1 Axis as a Key Pathogenic Signaling Node in Diabetic Islets. Cell Metab. 2019, 29, 1422–1432.e1423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fazakerley, D.J.; van Gerwen, J.; Cooke, K.C.; Duan, X.; Needham, E.J.; Diaz-Vegas, A.; Madsen, S.; Norris, D.M.; Shun-Shion, A.S.; Krycer, J.R.; et al. Phosphoproteomics reveals rewiring of the insulin signaling network and multi-nodal defects in insulin resistance. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Needham, E.J.; Hingst, J.R.; Onslev, J.D.; Diaz-Vegas, A.; Leandersson, M.R.; Huckstep, H.; Kristensen, J.M.; Kido, K.; Richter, E.A.; Hojlund, K.; et al. Personalized phosphoproteomics of skeletal muscle insulin resistance and exercise links MINDY1 to insulin action. Cell Metab. 2024, 36, 2542–2559.e2546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boucher, M.J.; Selander, L.; Carlsson, L.; Edlund, H. Phosphorylation marks IPF1/PDX1 protein for degradation by glycogen synthase kinase 3-dependent mechanisms. J. Biol. Chem. 2006, 281, 6395–6403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghosh, R.; Colon-Negron, K.; Papa, F.R. Endoplasmic reticulum stress, degeneration of pancreatic islet beta-cells, and therapeutic modulation of the unfolded protein response in diabetes. Mol. Metab. 2019, 27S, S60–S68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yong, J.; Johnson, J.D.; Arvan, P.; Han, J.; Kaufman, R.J. Therapeutic opportunities for pancreatic beta-cell ER stress in diabetes mellitus. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 2021, 17, 455–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haws, S.A.; Leech, C.M.; Denu, J.M. Metabolism and the Epigenome: A Dynamic Relationship. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2020, 45, 731–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramms, B.; Pollow, D.P.; Zhu, H.; Nora, C.; Harrington, A.R.; Omar, I.; Gordts, P.; Wortham, M.; Sander, M. Systemic LSD1 Inhibition Prevents Aberrant Remodeling of Metabolism in Obesity. Diabetes 2022, 71, 2513–2529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wortham, M.; Liu, F.; Harrington, A.R.; Fleischman, J.Y.; Wallace, M.; Mulas, F.; Mallick, M.; Vinckier, N.K.; Cross, B.R.; Chiou, J.; et al. Nutrient regulation of the islet epigenome controls adaptive insulin secretion. J. Clin. Investig. 2023, 133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bompada, P.; Atac, D.; Luan, C.; Andersson, R.; Omella, J.D.; Laakso, E.O.; Wright, J.; Groop, L.; De Marinis, Y. Histone acetylation of glucose-induced thioredoxin-interacting protein gene expression in pancreatic islets. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 2016, 81, 82–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, F.; Li, N.; Huang, H.B.; Wang, J.B.; Yang, X.F.; Wang, H.D.; Huang, W.; Li, F.R. LSD1 inhibition yields functional insulin-producing cells from human embryonic stem cells. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2020, 11, 163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, C.K.; Wade-Vallance, A.K.; Luciani, D.S.; Brindle, P.K.; Lynn, F.C.; Gibson, W.T. The p300 and CBP Transcriptional Coactivators Are Required for beta-Cell and alpha-Cell Proliferation. Diabetes 2018, 67, 412–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.F.; Zhou, S.Y.; Wang, C.; Huang, W.; Li, N.; He, F.; Li, F.R. Inhibition of LSD1 promotes the differentiation of human induced pluripotent stem cells into insulin-producing cells. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2020, 11, 185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egan, B.; Zierath, J.R. Exercise metabolism and the molecular regulation of skeletal muscle adaptation. Cell Metab. 2013, 17, 162–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xourafa, G.; Korbmacher, M.; Roden, M. Inter-organ crosstalk during development and progression of type 2 diabetes mellitus. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 2024, 20, 27–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shvedunova, M.; Akhtar, A. Modulation of cellular processes by histone and non-histone protein acetylation. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2022, 23, 329–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hostrup, M.; Lemminger, A.K.; Stocks, B.; Gonzalez-Franquesa, A.; Larsen, J.K.; Quesada, J.P.; Thomassen, M.; Weinert, B.T.; Bangsbo, J.; Deshmukh, A.S. High-intensity interval training remodels the proteome and acetylome of human skeletal muscle. eLife 2022, 11, e69802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, J.; Li, C.; Kang, X. The epigenetic regulatory effect of histone acetylation and deacetylation on skeletal muscle metabolism-a review. Front. Physiol. 2023, 14, 1267456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tian, H.; Liu, S.; Ren, J.; Lee, J.K.W.; Wang, R.; Chen, P. Role of Histone Deacetylases in Skeletal Muscle Physiology and Systemic Energy Homeostasis: Implications for Metabolic Diseases and Therapy. Front. Physiol. 2020, 11, 949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ong, B.X.; Brunmeir, R.; Zhang, Q.; Peng, X.; Idris, M.; Liu, C.; Xu, F. Regulation of Thermogenic Adipocyte Differentiation and Adaptive Thermogenesis Through Histone Acetylation. Front. Endocrinol. 2020, 11, 95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, X.; Zhang, Q.; Liao, C.; Han, W.; Xu, F. Epigenomic Control of Thermogenic Adipocyte Differentiation and Function. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 1793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bricambert, J.; Miranda, J.; Benhamed, F.; Girard, J.; Postic, C.; Dentin, R. Salt-inducible kinase 2 links transcriptional coactivator p300 phosphorylation to the prevention of ChREBP-dependent hepatic steatosis in mice. J. Clin. Investig. 2010, 120, 4316–4331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, H.; Xie, X.; Song, X.; Huang, M.; Su, T.; Chang, X.; Liang, B.; Huang, D. Orphan nuclear receptor NR4A1 suppresses hyperhomocysteinemia-induced hepatic steatosis in vitro and in vivo. FEBS Lett. 2019, 593, 1061–1071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, M.J.; Long, M.; Dai, R.J. Acetylation of H3K27 activated lncRNA NEAT1 and promoted hepatic lipid accumulation in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease via regulating miR-212-5p/GRIA3. Mol. Cell. Biochem. 2022, 477, 191–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Deng, X.; Chen, Y.; Xu, W.; Xu, F.; Liang, H. SIRT1 mediates nutritional regulation of SREBP-1c-driven hepatic PNPLA3 transcription via modulation of H3k9 acetylation. Genes Environ. 2022, 44, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, H.; Hu, M.; Liang, X.; Ajmo, J.M.; Li, X.; Bataller, R.; Odena, G.; Stevens, S.M., Jr.; You, M. Deletion of SIRT1 from hepatocytes in mice disrupts lipin-1 signaling and aggravates alcoholic fatty liver. Gastroenterology 2014, 146, 801–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, X.; Huang, M.; Kim, H.G.; Zhang, Y.; Chowdhury, K.; Cai, W.; Saxena, R.; Schwabe, R.F.; Liangpunsakul, S.; Dong, X.C. SIRT6 Protects Against Liver Fibrosis by Deacetylation and Suppression of SMAD3 in Hepatic Stellate Cells. Cell. Mol. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2020, 10, 341–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Min, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Ji, Y.; Liu, S.; Guan, C.; Wei, L.; Yu, H.; Zhang, Z. Post-translational modifications in the pathophysiological process of metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease. Cell Biosci. 2025, 15, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, S.; Jena, G. Valproic Acid Improves Glucose Homeostasis by Increasing Beta-Cell Proliferation, Function, and Reducing its Apoptosis through HDAC Inhibition in Juvenile Diabetic Rat. J. Biochem. Mol. Toxicol. 2016, 30, 438–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chou, D.H.; Holson, E.B.; Wagner, F.F.; Tang, A.J.; Maglathlin, R.L.; Lewis, T.A.; Schreiber, S.L.; Wagner, B.K. Inhibition of histone deacetylase 3 protects beta cells from cytokine-induced apoptosis. Chem. Biol. 2012, 19, 669–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Larsen, L.; Tonnesen, M.; Ronn, S.G.; Storling, J.; Jorgensen, S.; Mascagni, P.; Dinarello, C.A.; Billestrup, N.; Mandrup-Poulsen, T. Inhibition of histone deacetylases prevents cytokine-induced toxicity in beta cells. Diabetologia 2007, 50, 779–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindelov Vestergaard, A.; Heiner Bang-Berthelsen, C.; Floyel, T.; Lucien Stahl, J.; Christen, L.; Taheri Sotudeh, F.; de Hemmer Horskjaer, P.; Stensgaard Frederiksen, K.; Greek Kofod, F.; Bruun, C.; et al. MicroRNAs and histone deacetylase inhibition-mediated protection against inflammatory beta-cell damage. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0203713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Remsberg, J.R.; Ediger, B.N.; Ho, W.Y.; Damle, M.; Li, Z.; Teng, C.; Lanzillotta, C.; Stoffers, D.A.; Lazar, M.A. Deletion of histone deacetylase 3 in adult beta cells improves glucose tolerance via increased insulin secretion. Mol. Metab. 2017, 6, 30–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, W.B.; Gao, L.; Wang, J.; Wang, Y.G.; Dong, Z.; Zhao, J.; Mi, Q.S.; Zhou, L. Conditional ablation of HDAC3 in islet beta cells results in glucose intolerance and enhanced susceptibility to STZ-induced diabetes. Oncotarget 2016, 7, 57485–57497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, M. Chemical and Biochemical Perspectives of Protein Lysine Methylation. Chem. Rev. 2018, 118, 6656–6705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murn, J.; Shi, Y. The winding path of protein methylation research: Milestones and new frontiers. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2017, 18, 517–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bedford, M.T.; Clarke, S.G. Protein arginine methylation in mammals: Who, what, and why. Mol. Cell 2009, 33, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, D.; Oh, K.J.; Han, H.S.; Yoon, Y.S.; Jung, C.Y.; Kim, S.T.; Koo, S.H. Protein arginine methyltransferase 1 regulates hepatic glucose production in a FoxO1-dependent manner. Hepatology 2012, 56, 1546–1556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamagata, K.; Daitoku, H.; Takahashi, Y.; Namiki, K.; Hisatake, K.; Kako, K.; Mukai, H.; Kasuya, Y.; Fukamizu, A. Arginine methylation of FOXO transcription factors inhibits their phosphorylation by Akt. Mol. Cell 2008, 32, 221–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, L.; Liu, J.; Zhang, X.O.; Sibley, K.; Najjar, S.M.; Lee, M.M.; Wu, Q. Inhibition of protein arginine methyltransferase 5 enhances hepatic mitochondrial biogenesis. J. Biol. Chem. 2018, 293, 10884–10894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, W.; Huang, J.; Chen, H.; Zhang, Y.; Zhu, X.; Li, J.; Zhang, W.; Yuan, Y.; Wang, Y.; Zheng, L.; et al. Histone methyltransferase G9a modulates hepatic insulin signaling via regulating HMGA1. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Mol. Basis Dis. 2018, 1864, 338–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.E.; Wang, C.; Xu, S.; Cho, Y.W.; Wang, L.; Feng, X.; Baldridge, A.; Sartorelli, V.; Zhuang, L.; Peng, W.; et al. H3K4 mono- and di-methyltransferase MLL4 is required for enhancer activation during cell differentiation. eLife 2013, 2, e01503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, N.; Cheng, D.; Richard, S.; Morel, M.; Iyer, V.R.; Aldaz, C.M.; Bedford, M.T. CARM1 promotes adipocyte differentiation by coactivating PPARgamma. EMBO Rep. 2008, 9, 193–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- LeBlanc, S.E.; Konda, S.; Wu, Q.; Hu, Y.J.; Oslowski, C.M.; Sif, S.; Imbalzano, A.N. Protein arginine methyltransferase 5 (Prmt5) promotes gene expression of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma2 (PPARgamma2) and its target genes during adipogenesis. Mol. Endocrinol. 2012, 26, 583–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, Z.; Yue, F.; Chen, X.; Narayanan, N.; Qiu, J.; Syed, S.A.; Imbalzano, A.N.; Deng, M.; Yu, P.; Hu, C.; et al. Protein Arginine Methyltransferase PRMT5 Regulates Fatty Acid Metabolism and Lipid Droplet Biogenesis in White Adipose Tissues. Adv. Sci. 2020, 7, 2002602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yiew, N.K.H.; Greenway, C.; Zarzour, A.; Ahmadieh, S.; Goo, B.; Kim, D.; Benson, T.W.; Ogbi, M.; Tang, Y.L.; Chen, W.; et al. Enhancer of zeste homolog 2 (EZH2) regulates adipocyte lipid metabolism independent of adipogenic differentiation: Role of apolipoprotein E. J. Biol. Chem. 2019, 294, 8577–8591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, S.; Jeong, H.J.; Kim, H.; Choi, D.; Cho, S.C.; Seong, J.K.; Koo, S.H.; Kang, J.S. Skeletal muscle-specific Prmt1 deletion causes muscle atrophy via deregulation of the PRMT6-FOXO3 axis. Autophagy 2019, 15, 1069–1081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, H.J.; Lee, H.J.; Vuong, T.A.; Choi, K.S.; Choi, D.; Koo, S.H.; Cho, S.C.; Cho, H.; Kang, J.S. Prmt7 Deficiency Causes Reduced Skeletal Muscle Oxidative Metabolism and Age-Related Obesity. Diabetes 2016, 65, 1868–1882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, H.; Gu, X.; Su, I.H.; Bottino, R.; Contreras, J.L.; Tarakhovsky, A.; Kim, S.K. Polycomb protein Ezh2 regulates pancreatic beta-cell Ink4a/Arf expression and regeneration in diabetes mellitus. Genes Dev. 2009, 23, 975–985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deering, T.G.; Ogihara, T.; Trace, A.P.; Maier, B.; Mirmira, R.G. Methyltransferase Set7/9 maintains transcription and euchromatin structure at islet-enriched genes. Diabetes 2009, 58, 185–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maganti, A.V.; Maier, B.; Tersey, S.A.; Sampley, M.L.; Mosley, A.L.; Ozcan, S.; Pachaiyappan, B.; Woster, P.M.; Hunter, C.S.; Stein, R.; et al. Transcriptional activity of the islet beta cell factor Pdx1 is augmented by lysine methylation catalyzed by the methyltransferase Set7/9. J. Biol. Chem. 2015, 290, 9812–9822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Yoon, B.H.; Oh, C.M.; Lee, J.; Lee, K.; Song, H.; Kim, E.; Yi, K.; Kim, M.Y.; Kim, H.; et al. PRMT1 Is Required for the Maintenance of Mature beta-Cell Identity. Diabetes 2020, 69, 355–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swatek, K.N.; Komander, D. Ubiquitin modifications. Cell Res. 2016, 26, 399–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rajalingam, K.; Dikic, I. SnapShot: Expanding the Ubiquitin Code. Cell 2016, 164, 1074–1074.e1071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, J.Z.; Crawford, N.; Longley, D.B. The role of Ubiquitination in Apoptosis and Necroptosis. Cell Death Differ. 2022, 29, 272–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, T.; Lei, K.; Lin, X.; Xie, Z.; Luo, S.; Zhou, Z.; Zhao, B.; Li, X. Protein ubiquitination in T cell development. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 941962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cockram, P.E.; Kist, M.; Prakash, S.; Chen, S.H.; Wertz, I.E.; Vucic, D. Ubiquitination in the regulation of inflammatory cell death and cancer. Cell Death Differ. 2021, 28, 591–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.; Ruan, J.; Chen, M.; Li, Z.; Manjengwa, G.; Schluter, D.; Song, W.; Wang, X. Deubiquitinating enzymes (DUBs): Decipher underlying basis of neurodegenerative diseases. Mol. Psychiatry 2022, 27, 259–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, S.; Dai, X.; Li, H.; Gong, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Huang, H. Overexpression of ring finger protein 20 inhibits the progression of liver fibrosis via mediation of histone H2B lysine 120 ubiquitination. Hum. Cell 2021, 34, 759–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, J.; Horikawa, Y.; Enya, M.; Takeda, J.; Imai, Y.; Imai, Y.; Handa, H.; Imai, T. L-Arginine prevents cereblon-mediated ubiquitination of glucokinase and stimulates glucose-6-phosphate production in pancreatic beta-cells. Commun. Biol. 2020, 3, 497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, T.; Zhang, S.; Xu, J.; Zhang, Y.; Sun, T.; Shao, Y.; Wang, J.; Tang, W.; Chen, F.; Han, X. HRD1, an Important Player in Pancreatic beta-Cell Failure and Therapeutic Target for Type 2 Diabetic Mice. Diabetes 2020, 69, 940–953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, G.; Liu, S.H.; Shahi, K.M.; Wang, H.; Duan, X.; Lin, X.; Feng, X.H.; Li, M.; Fisher, W.E.; Demayo, F.J.; et al. Negative regulation of pancreatic and duodenal homeobox-1 by somatostatin receptor subtype 5. Mol. Endocrinol. 2012, 26, 1225–1234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ardestani, A.; Paroni, F.; Azizi, Z.; Kaur, S.; Khobragade, V.; Yuan, T.; Frogne, T.; Tao, W.; Oberholzer, J.; Pattou, F.; et al. MST1 is a key regulator of beta cell apoptosis and dysfunction in diabetes. Nat. Med. 2014, 20, 385–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fournet, M.; Bonte, F.; Desmouliere, A. Glycation Damage: A Possible Hub for Major Pathophysiological Disorders and Aging. Aging Dis. 2018, 9, 880–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshi, H.J.; Hansen, L.; Narimatsu, Y.; Freeze, H.H.; Henrissat, B.; Bennett, E.; Wandall, H.H.; Clausen, H.; Schjoldager, K.T. Glycosyltransferase genes that cause monogenic congenital disorders of glycosylation are distinct from glycosyltransferase genes associated with complex diseases. Glycobiology 2018, 28, 284–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanley, P. What Have We Learned from Glycosyltransferase Knockouts in Mice? J. Mol. Biol. 2016, 428, 3166–3182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lowe, J.B.; Marth, J.D. A genetic approach to Mammalian glycan function. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2003, 72, 643–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeze, H.H.; Chong, J.X.; Bamshad, M.J.; Ng, B.G. Solving glycosylation disorders: Fundamental approaches reveal complicated pathways. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2014, 94, 161–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vosseller, K.; Wells, L.; Lane, M.D.; Hart, G.W. Elevated nucleocytoplasmic glycosylation by O-GlcNAc results in insulin resistance associated with defects in Akt activation in 3T3-L1 adipocytes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2002, 99, 5313–5318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whelan, S.A.; Dias, W.B.; Thiruneelakantapillai, L.; Lane, M.D.; Hart, G.W. Regulation of insulin receptor substrate 1 (IRS-1)/AKT kinase-mediated insulin signaling by O-Linked beta-N-acetylglucosamine in 3T3-L1 adipocytes. J. Biol. Chem. 2010, 285, 5204–5211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nie, H.; Yi, W. O-GlcNAcylation, a sweet link to the pathology of diseases. J. Zhejiang Univ. Sci. B 2019, 20, 437–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, X.; Ongusaha, P.P.; Miles, P.D.; Havstad, J.C.; Zhang, F.; So, W.V.; Kudlow, J.E.; Michell, R.H.; Olefsky, J.M.; Field, S.J.; et al. Phosphoinositide signalling links O-GlcNAc transferase to insulin resistance. Nature 2008, 451, 964–969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, J.; Hart, G.W. Protein O-GlcNAcylation in diabetes and diabetic complications. Expert Rev. Proteom. 2013, 10, 365–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perla, F.M.; Prelati, M.; Lavorato, M.; Visicchio, D.; Anania, C. The Role of Lipid and Lipoprotein Metabolism in Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease. Children 2017, 4, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, Z.; Mu, J.; Gao, Z.; Huang, S.; Chen, L. Biological Functions and Potential Therapeutic Significance of O-GlcNAcylation in Hepatic Cellular Stress and Liver Diseases. Cells 2024, 13, 805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldini, S.F.; Wavelet, C.; Hainault, I.; Guinez, C.; Lefebvre, T. The Nutrient-Dependent O-GlcNAc Modification Controls the Expression of Liver Fatty Acid Synthase. J. Mol. Biol. 2016, 428, 3295–3304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cha, J.Y.; Repa, J.J. The liver X receptor (LXR) and hepatic lipogenesis. The carbohydrate-response element-binding protein is a target gene of LXR. J. Biol. Chem. 2007, 282, 743–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bindesboll, C.; Fan, Q.; Norgaard, R.C.; MacPherson, L.; Ruan, H.B.; Wu, J.; Pedersen, T.A.; Steffensen, K.R.; Yang, X.; Matthews, J.; et al. Liver X receptor regulates hepatic nuclear O-GlcNAc signaling and carbohydrate responsive element-binding protein activity. J. Lipid Res. 2015, 56, 771–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anthonisen, E.H.; Berven, L.; Holm, S.; Nygard, M.; Nebb, H.I.; Gronning-Wang, L.M. Nuclear receptor liver X receptor is O-GlcNAc-modified in response to glucose. J. Biol. Chem. 2010, 285, 1607–1615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Hu, Y.J.; Fan, W.X.; Quan, X.; Xu, B.; Li, S.Z. O-GlcNAcylation: The Underestimated Emerging Regulators of Skeletal Muscle Physiology. Cells 2022, 11, 1789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Qian, K. Protein O-GlcNAcylation: Emerging mechanisms and functions. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2017, 18, 452–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.D.; Vera, N.B.; Yang, Y.; Zhang, B.; Ni, W.; Ziso-Qejvanaj, E.; Ding, S.; Zhang, K.; Yin, R.; Wang, S.; et al. Adipocyte OGT governs diet-induced hyperphagia and obesity. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 5103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, N.; Li, Y.; Liu, F.; Dong, X.; Ma, D. Adipocytes regulate monocyte development through the OGT-NEFA-CD36/FABP4 pathway in high-fat diet-induced obesity. Cell Death Dis. 2025, 16, 401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hanover, J.A.; Lai, Z.; Lee, G.; Lubas, W.A.; Sato, S.M. Elevated O-linked N-acetylglucosamine metabolism in pancreatic beta-cells. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 1999, 362, 38–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akimoto, Y.; Hart, G.W.; Wells, L.; Vosseller, K.; Yamamoto, K.; Munetomo, E.; Ohara-Imaizumi, M.; Nishiwaki, C.; Nagamatsu, S.; Hirano, H.; et al. Elevation of the post-translational modification of proteins by O-linked N-acetylglucosamine leads to deterioration of the glucose-stimulated insulin secretion in the pancreas of diabetic Goto-Kakizaki rats. Glycobiology 2007, 17, 127–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Z.; Gucek, M.; Hart, G.W. Cross-talk between GlcNAcylation and phosphorylation: Site-specific phosphorylation dynamics in response to globally elevated O-GlcNAc. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2008, 105, 13793–13798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, P.; Shimoji, S.; Hart, G.W. Site-specific interplay between O-GlcNAcylation and phosphorylation in cellular regulation. FEBS Lett. 2010, 584, 2526–2538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- F, S.M.; Abrami, L.; Linder, M.E.; Bamji, S.X.; Dickinson, B.C.; van der Goot, F.G. Mechanisms and functions of protein S-acylation. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2024, 25, 488–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, H.; Su, X.; He, B. Protein lysine acylation and cysteine succination by intermediates of energy metabolism. ACS Chem. Biol. 2012, 7, 947–960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magee, A.I.; Siddle, K. Insulin and IGF-1 receptors contain covalently bound palmitic acid. J. Cell. Biochem. 1988, 37, 347–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonelle-Gispert, C.; Molinete, M.; Halban, P.A.; Sadoul, K. Membrane localization and biological activity of SNAP-25 cysteine mutants in insulin-secreting cells. J. Cell Sci. 2000, 113 Pt 18, 3197–3205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buenaventura, T.; Bitsi, S.; Laughlin, W.E.; Burgoyne, T.; Lyu, Z.; Oqua, A.I.; Norman, H.; McGlone, E.R.; Klymchenko, A.S.; Correa, I.R., Jr.; et al. Agonist-induced membrane nanodomain clustering drives GLP-1 receptor responses in pancreatic beta cells. PLoS Biol. 2019, 17, e3000097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, G.; Adak, S.; Spyropoulos, G.; Zhang, Q.; Feng, C.; Yin, L.; Speck, S.L.; Shyr, Z.; Morikawa, S.; Kitamura, R.A.; et al. Palmitoylation couples insulin hypersecretion with beta cell failure in diabetes. Cell Metab. 2023, 35, 332–344.e337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blaustein, M.; Piegari, E.; Martinez Calejman, C.; Vila, A.; Amante, A.; Manese, M.V.; Zeida, A.; Abrami, L.; Veggetti, M.; Guertin, D.A.; et al. Akt Is S-Palmitoylated: A New Layer of Regulation for Akt. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2021, 9, 626404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, J.W.; Wang, J.; Guo, H.; Zhao, Y.Y.; Sun, H.H.; Li, Y.F.; Lai, X.Y.; Zhao, N.; Wang, X.; Xie, C.; et al. CD36 facilitates fatty acid uptake by dynamic palmitoylation-regulated endocytosis. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 4765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Hao, J.W.; Wang, X.; Guo, H.; Sun, H.H.; Lai, X.Y.; Liu, L.Y.; Zhu, M.; Wang, H.Y.; Li, Y.F.; et al. DHHC4 and DHHC5 Facilitate Fatty Acid Uptake by Palmitoylating and Targeting CD36 to the Plasma Membrane. Cell Rep. 2019, 26, 209–221.e205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, K.; Murakami, S.; Sun, Y.; Kilpatrick, C.L.; Luscher, B. DHHC7 Palmitoylates Glucose Transporter 4 (Glut4) and Regulates Glut4 Membrane Translocation. J. Biol. Chem. 2017, 292, 2979–2991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, M.; Lee, J.; Jeong, K.; Pak, Y. Caveolin-2 palmitoylation turnover facilitates insulin receptor substrate-1-directed lipid metabolism by insulin receptor tyrosine kinase. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Mol. Basis Dis. 2024, 1870, 167173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bao, X.; Wang, Y.; Li, X.; Li, X.M.; Liu, Z.; Yang, T.; Wong, C.F.; Zhang, J.; Hao, Q.; Li, X.D. Identification of ‘erasers’ for lysine crotonylated histone marks using a chemical proteomics approach. eLife 2014, 3, e02999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, G.; Li, C.; Lu, M.; Lu, K.; Li, H. Protein lysine crotonylation: Past, present, perspective. Cell Death Dis. 2021, 12, 703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tian, D.; Zeng, X.; Gong, Y.; Zheng, Y.; Zhang, J.; Wu, Z. HDAC1 inhibits beige adipocyte-mediated thermogenesis through histone crotonylation of Pgc1a/Ucp1. Cell. Signal. 2023, 111, 110875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, J.; Zhou, Y.; Su, X.; Yu, J.J.; Khan, S.; Jiang, H.; Kim, J.; Woo, J.; Kim, J.H.; Choi, B.H.; et al. Sirt5 is a NAD-dependent protein lysine demalonylase and desuccinylase. Science 2011, 334, 806–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishida, Y.; Rardin, M.J.; Carrico, C.; He, W.; Sahu, A.K.; Gut, P.; Najjar, R.; Fitch, M.; Hellerstein, M.; Gibson, B.W.; et al. SIRT5 Regulates both Cytosolic and Mitochondrial Protein Malonylation with Glycolysis as a Major Target. Mol. Cell 2015, 59, 321–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, Y.; Cai, T.; Li, T.; Xue, P.; Zhou, B.; He, X.; Wei, P.; Liu, P.; Yang, F.; Wei, T. Lysine malonylation is elevated in type 2 diabetic mouse models and enriched in metabolic associated proteins. Mol. Cell. Proteom. 2015, 14, 227–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.; Chen, Y.; Tishkoff, D.X.; Peng, C.; Tan, M.; Dai, L.; Xie, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Zwaans, B.M.; Skinner, M.E.; et al. SIRT5-mediated lysine desuccinylation impacts diverse metabolic pathways. Mol. Cell 2013, 50, 919–930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rardin, M.J.; He, W.; Nishida, Y.; Newman, J.C.; Carrico, C.; Danielson, S.R.; Guo, A.; Gut, P.; Sahu, A.K.; Li, B.; et al. SIRT5 regulates the mitochondrial lysine succinylome and metabolic networks. Cell Metab. 2013, 18, 920–933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.; Meyer, J.G.; Cai, W.; Softic, S.; Li, M.E.; Verdin, E.; Newgard, C.; Schilling, B.; Kahn, C.R. Regulation of UCP1 and Mitochondrial Metabolism in Brown Adipose Tissue by Reversible Succinylation. Mol. Cell 2019, 74, 844–857.e847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flotho, A.; Melchior, F. Sumoylation: A regulatory protein modification in health and disease. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2013, 82, 357–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, H.M.; Yeh, E.T.H. SUMO: From Bench to Bedside. Physiol. Rev. 2020, 100, 1599–1619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Celen, A.B.; Sahin, U. Sumoylation on its 25th anniversary: Mechanisms, pathology, and emerging concepts. FEBS J. 2020, 287, 3110–3140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, G.Y.; Jang, H.; Lee, J.H.; Huh, J.Y.; Choi, S.; Chung, J.; Kim, J.B. PIASy-mediated sumoylation of SREBP1c regulates hepatic lipid metabolism upon fasting signaling. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2014, 34, 926–938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zou, D.; Liao, J.; Xiao, M.; Liu, L.; Dai, D.; Xu, M. Impaired SUMOylation of FoxA1 promotes nonalcoholic fatty liver disease through down-regulation of Sirt6. Cell Death Dis. 2024, 15, 674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alfaro, A.J.; Dittner, C.; Becker, J.; Loft, A.; Mhamane, A.; Maida, A.; Georgiadi, A.; Tsokanos, F.F.; Klepac, K.; Molocea, C.E.; et al. Fasting-sensitive SUMO-switch on Prox1 controls hepatic cholesterol metabolism. EMBO Rep. 2023, 24, e55981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stein, S.; Lemos, V.; Xu, P.; Demagny, H.; Wang, X.; Ryu, D.; Jimenez, V.; Bosch, F.; Luscher, T.F.; Oosterveer, M.H.; et al. Impaired SUMOylation of nuclear receptor LRH-1 promotes nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. J. Clin. Investig. 2017, 127, 583–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, Q.; Cao, Y.; Chen, Y.; Wang, J.; Fan, Q.; Huang, X.; Wang, Y.; Wang, T.; Wang, X.; Ma, J.; et al. Senp2 regulates adipose lipid storage by de-SUMOylation of Setdb1. J. Mol. Cell Biol. 2018, 10, 258–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, H.; Wang, Y.H.; Liu, X.; Gao, J.; Yang, C.; Huang, T.; Zhang, L.; Luo, X.; Gao, Z.; Wang, T.; et al. SUMOylation of ERp44 enhances Ero1alpha ER retention contributing to the pathogenesis of obesity and insulin resistance. Metabolism 2023, 139, 155351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Q.; Zheng, Q.; Zuo, Y.; Chen, Y.; Ma, J.; Ni, P.; Cheng, J. SENP2 Suppresses Necdin Expression to Promote Brown Adipocyte Differentiation. Cell Rep. 2019, 28, 2004–2011.e2004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.S.; Chae, S.; Nan, J.; Koo, Y.D.; Lee, S.A.; Park, Y.J.; Hwang, D.; Han, W.; Lee, D.S.; Kim, Y.B.; et al. SENP2 suppresses browning of white adipose tissues by de-conjugating SUMO from C/EBPbeta. Cell Rep. 2022, 38, 110408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kishi, A.; Nakamura, T.; Nishio, Y.; Maegawa, H.; Kashiwagi, A. Sumoylation of Pdx1 is associated with its nuclear localization and insulin gene activation. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 2003, 284, E830–E840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shao, C.; Cobb, M.H. Sumoylation regulates the transcriptional activity of MafA in pancreatic beta cells. J. Biol. Chem. 2009, 284, 3117–3124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, X.; Lai, Q.; Chen, C.; Li, N.; Sun, F.; Huang, W.; Zhang, S.; Yu, Q.; Yang, P.; Xiong, F.; et al. Both conditional ablation and overexpression of E2 SUMO-conjugating enzyme (UBC9) in mouse pancreatic beta cells result in impaired beta cell function. Diabetologia 2018, 61, 881–895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hajmrle, C.; Ferdaoussi, M.; Plummer, G.; Spigelman, A.F.; Lai, K.; Manning Fox, J.E.; MacDonald, P.E. SUMOylation protects against IL-1beta-induced apoptosis in INS-1 832/13 cells and human islets. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 2014, 307, E664–E673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, X.Q.; Kolic, J.; Marchi, P.; Sipione, S.; Macdonald, P.E. SUMOylation regulates Kv2.1 and modulates pancreatic beta-cell excitability. J. Cell Sci. 2009, 122, 775–779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dai, X.Q.; Plummer, G.; Casimir, M.; Kang, Y.; Hajmrle, C.; Gaisano, H.Y.; Manning Fox, J.E.; MacDonald, P.E. SUMOylation regulates insulin exocytosis downstream of secretory granule docking in rodents and humans. Diabetes 2011, 60, 838–847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferdaoussi, M.; Fu, J.; Dai, X.; Manning Fox, J.E.; Suzuki, K.; Smith, N.; Plummer, G.; MacDonald, P.E. SUMOylation and calcium control syntaxin-1A and secretagogin sequestration by tomosyn to regulate insulin exocytosis in human ss cells. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferdaoussi, M.; Dai, X.; Jensen, M.V.; Wang, R.; Peterson, B.S.; Huang, C.; Ilkayeva, O.; Smith, N.; Miller, N.; Hajmrle, C.; et al. Isocitrate-to-SENP1 signaling amplifies insulin secretion and rescues dysfunctional beta cells. J. Clin. Investig. 2015, 125, 3847–3860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aukrust, I.; Bjorkhaug, L.; Negahdar, M.; Molnes, J.; Johansson, B.B.; Muller, Y.; Haas, W.; Gygi, S.P.; Sovik, O.; Flatmark, T.; et al. SUMOylation of pancreatic glucokinase regulates its cellular stability and activity. J. Biol. Chem. 2013, 288, 5951–5962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nan, J.; Lee, J.S.; Moon, J.H.; Lee, S.A.; Park, Y.J.; Lee, D.S.; Chung, S.S.; Park, K.S. SENP2 regulates mitochondrial function and insulin secretion in pancreatic beta cells. Exp. Mol. Med. 2022, 54, 72–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rajan, S.; Torres, J.; Thompson, M.S.; Philipson, L.H. SUMO downregulates GLP-1-stimulated cAMP generation and insulin secretion. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 2012, 302, E714–E723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Lin, H.; Smith, N.; Spigelman, A.F.; Suzuki, K.; Ferdaoussi, M.; Alghamdi, T.A.; Lewandowski, S.L.; Jin, Y.; Bautista, A.; Wang, Y.W.; et al. beta-Cell Knockout of SENP1 Reduces Responses to Incretins and Worsens Oral Glucose Tolerance in High-Fat Diet-Fed Mice. Diabetes 2021, 70, 2626–2638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Foster, M.W.; Hess, D.T.; Stamler, J.S. Protein S-nitrosylation in health and disease: A current perspective. Trends Mol. Med. 2009, 15, 391–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernando, V.; Zheng, X.; Walia, Y.; Sharma, V.; Letson, J.; Furuta, S. S-Nitrosylation: An Emerging Paradigm of Redox Signaling. Antioxidants 2019, 8, 404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cordes, C.M.; Bennett, R.G.; Siford, G.L.; Hamel, F.G. Nitric oxide inhibits insulin-degrading enzyme activity and function through S-nitrosylation. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2009, 77, 1064–1073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, H.L.; Grimmett, Z.W.; Venetos, N.M.; Stomberski, C.T.; Qian, Z.; McLaughlin, P.J.; Bansal, P.K.; Zhang, R.; Reynolds, J.D.; Premont, R.T.; et al. An enzyme that selectively S-nitrosylates proteins to regulate insulin signaling. Cell 2023, 186, 5812–5825.e5821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Calay, E.S.; Fan, J.; Arduini, A.; Kunz, R.C.; Gygi, S.P.; Yalcin, A.; Fu, S.; Hotamisligil, G.S. METABOLISM. S-Nitrosylation links obesity-associated inflammation to endoplasmic reticulum dysfunction. Science 2015, 349, 500–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, Q.; Zhang, Z.; Orwig, A.; Chen, S.; Ding, W.X.; Xu, Y.; Kunz, R.C.; Lind, N.R.L.; Stamler, J.S.; Yang, L. S-Nitrosoglutathione Reductase Dysfunction Contributes to Obesity-Associated Hepatic Insulin Resistance via Regulating Autophagy. Diabetes 2018, 67, 193–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pauli, J.R.; Ropelle, E.R.; Cintra, D.E.; Carvalho-Filho, M.A.; Moraes, J.C.; De Souza, C.T.; Velloso, L.A.; Carvalheira, J.B.; Saad, M.J. Acute physical exercise reverses S-nitrosation of the insulin receptor, insulin receptor substrate 1 and protein kinase B/Akt in diet-induced obese Wistar rats. J. Physiol. 2008, 586, 659–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yasukawa, T.; Tokunaga, E.; Ota, H.; Sugita, H.; Martyn, J.A.; Kaneki, M. S-nitrosylation-dependent inactivation of Akt/protein kinase B in insulin resistance. J. Biol. Chem. 2005, 280, 7511–7518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalho-Filho, M.A.; Ueno, M.; Carvalheira, J.B.; Velloso, L.A.; Saad, M.J. Targeted disruption of iNOS prevents LPS-induced S-nitrosation of IRbeta/IRS-1 and Akt and insulin resistance in muscle of mice. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 2006, 291, E476–E482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Su, D.; Shukla, A.K.; Chen, B.; Kim, J.S.; Nakayasu, E.; Qu, Y.; Aryal, U.; Weitz, K.; Clauss, T.R.; Monroe, M.E.; et al. Quantitative site-specific reactivity profiling of S-nitrosylation in mouse skeletal muscle using cysteinyl peptide enrichment coupled with mass spectrometry. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2013, 57, 68–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ovadia, H.; Haim, Y.; Nov, O.; Almog, O.; Kovsan, J.; Bashan, N.; Benhar, M.; Rudich, A. Increased adipocyte S-nitrosylation targets anti-lipolytic action of insulin: Relevance to adipose tissue dysfunction in obesity. J. Biol. Chem. 2011, 286, 30433–30443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, H.; Wang, A.X.; Aylor, K.; Barrett, E.J. Nitric oxide directly promotes vascular endothelial insulin transport. Diabetes 2013, 62, 4030–4042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, M.F.; Pan, K.T.; Chang, F.Y.; Khoo, K.H.; Urlaub, H.; Cheng, C.F.; Chang, G.D.; Haj, F.G.; Meng, T.C. S-nitrosylation of endogenous protein tyrosine phosphatases in endothelial insulin signaling. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2016, 99, 199–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Katashima, C.K.; Silva, V.R.R.; Lenhare, L.; Marin, R.M.; Carvalheira, J.B.C. iNOS promotes hypothalamic insulin resistance associated with deregulation of energy balance and obesity in rodents. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 9265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rizzo, M.A.; Piston, D.W. Regulation of beta cell glucokinase by S-nitrosylation and association with nitric oxide synthase. J. Cell Biol. 2003, 161, 243–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, S.Y.; Nkobena, A.; Kraft, C.A.; Markwardt, M.L.; Rizzo, M.A. Glucagon-like peptide 1 stimulates post-translational activation of glucokinase in pancreatic beta cells. J. Biol. Chem. 2011, 286, 16768–16774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiseman, D.A.; Kalwat, M.A.; Thurmond, D.C. Stimulus-induced S-nitrosylation of Syntaxin 4 impacts insulin granule exocytosis. J. Biol. Chem. 2011, 286, 16344–16354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Yu, Q.; Li, Z.; Zhao, Y.; Sun, Y. Protein neddylation and its role in health and diseases. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2024, 9, 85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, C.; Gu, L.; Matye, D.J.; Clayton, Y.D.; Hasan, M.N.; Wang, Y.; Friedman, J.E.; Li, T. Cullin neddylation inhibitor attenuates hyperglycemia by enhancing hepatic insulin signaling through insulin receptor substrate stabilization. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2022, 119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gonzalez-Rellan, M.J.; Fernandez, U.; Parracho, T.; Novoa, E.; Fondevila, M.F.; da Silva Lima, N.; Ramos, L.; Rodriguez, A.; Serrano-Macia, M.; Perez-Mejias, G.; et al. Neddylation of phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase 1 controls glucose metabolism. Cell Metab. 2023, 35, 1630–1645.e1635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, X.; Kong, X.; Wu, H.; Hao, J.; Li, S.; Gu, Z.; Zeng, X.; Shen, Y.; Wang, S.; Chen, J.; et al. UBE2M-mediated neddylation of TRIM21 regulates obesity-induced inflammation and metabolic disorders. Cell Metab. 2023, 35, 1390–1405.e1398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kim, Y.K.; Kim, H. Emerging Roles of Post-Translational Modifications in Metabolic Homeostasis and Type 2 Diabetes. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 11552. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311552

Kim YK, Kim H. Emerging Roles of Post-Translational Modifications in Metabolic Homeostasis and Type 2 Diabetes. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2025; 26(23):11552. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311552

Chicago/Turabian StyleKim, Yong Kyung, and Hyeongseok Kim. 2025. "Emerging Roles of Post-Translational Modifications in Metabolic Homeostasis and Type 2 Diabetes" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 26, no. 23: 11552. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311552

APA StyleKim, Y. K., & Kim, H. (2025). Emerging Roles of Post-Translational Modifications in Metabolic Homeostasis and Type 2 Diabetes. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 26(23), 11552. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311552