The Specific Pathogenicity Pattern of the Different CRB1 Isoforms Conditions Clinical Severity in Inherited Retinal Dystrophies

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

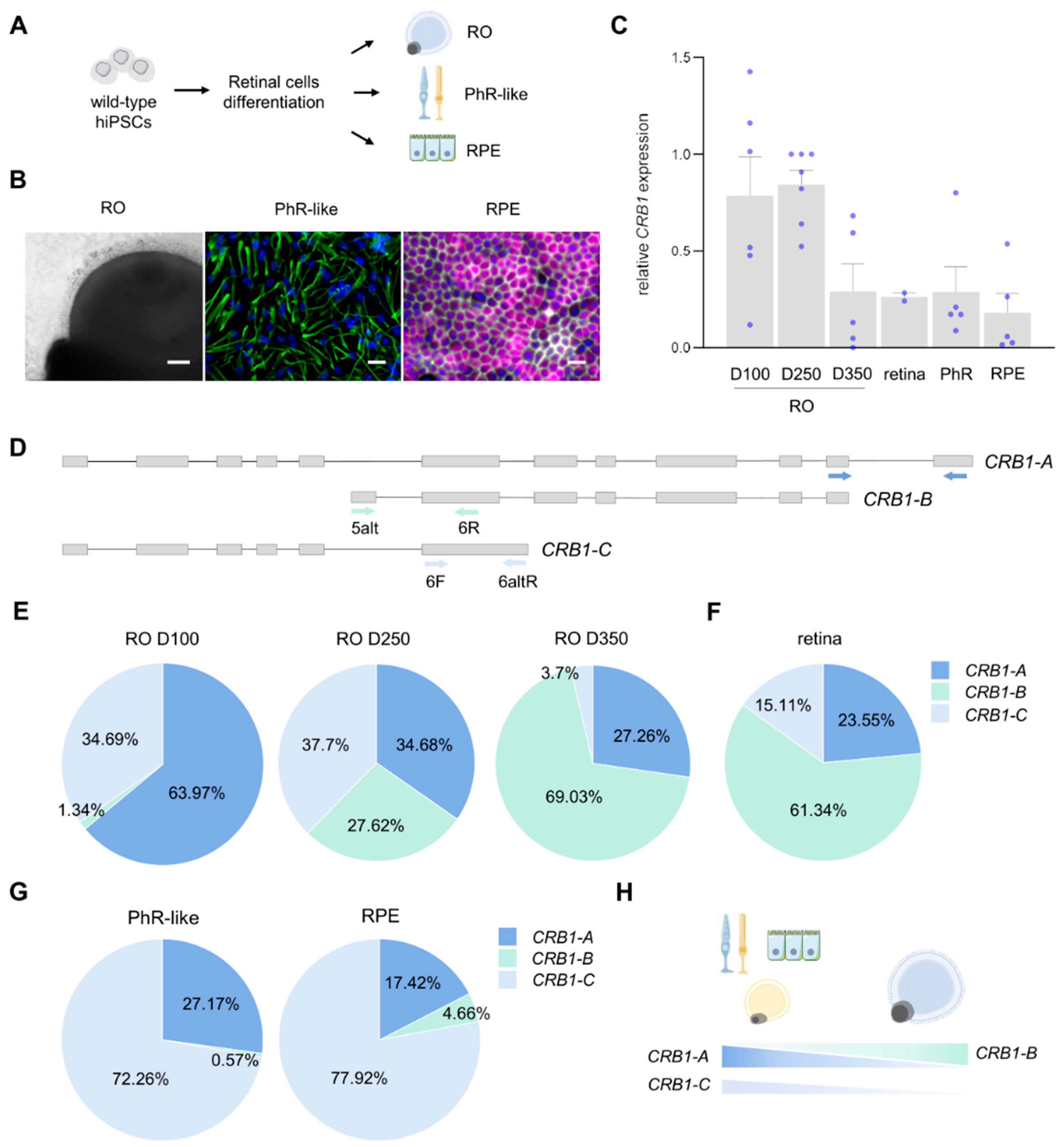

2.1. Differential Expression of CRB1 Isoforms During Retinal Development and Maturation

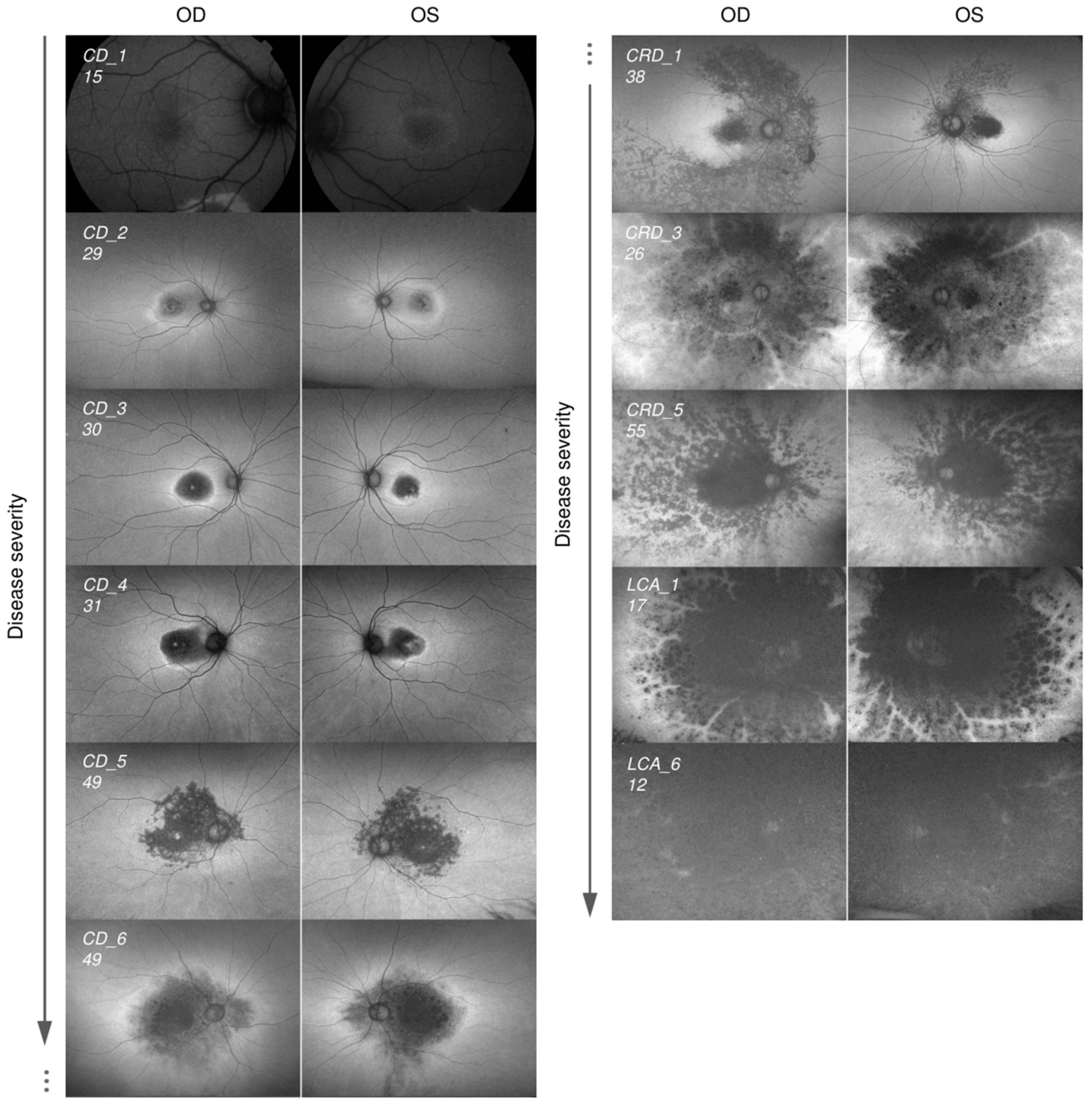

2.2. Cohort of Patients Carrying Pathogenic Variants in CRB1 Causing CD, CRD, and LCA

| ID * | ID_2 | Clinical Diagnosis | Nucleotide Change | Protein Change | Zygosis | Exon | Age of Onset | Age | BCVA OD * | BCVA OS * | Ref. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fi25/03_01 | CD_1 | CD | c.498_506delAATTGATGG | p.Ile167_Gly169del | homo | 2 | 14 | adolescence | 21 | 0.8 | 0.4 | [39] |

| Fi25/04_01 | CD_2 | CD | c.498_506delAATTGATGG | p.Ile167_Gly169del | het | 2 | 11 | late childhood | 38 | 0.3 | 0.1 | [39] |

| c.3299T>C | p.Ile1100Thr | het | 9 | [40] | ||||||||

| Fi25/05_01 | CD_3 | CD | c.498_506delAATTGATGG | p.Ile167_Gly169del | homo | 2 | 22 | adult | 32 | 0.4 | 0.16 | [39] |

| Fi25/06_01 | CD_4 | CD | c.498_506delAATTGATGG | p.Ile167_Gly169del | het | 2 | 13 | adolescence | 35 | 0.3 | 0.4 | [39] |

| c.3299T>G | p.Ile1100Arg | het | 9 | [41] | ||||||||

| Fi25/07_01 | CD_5 | extensive CD/inverse RP | c.498_506delAATTGATGG | p.Ile167_Gly169del | het | 2 | 43 | adult | 51 | 0.05 | 0.025 | [39] |

| c.1084C>T | p.Gln362Ter | het | 5 | [42] | ||||||||

| Fi25/08_01 | CD_6 | extensive CD/inverse RP | c.498_506delAATTGATGG | p.Ile167_Gly169del | het | 2 | 14 | adolescence | 61 | 0.04 | 0.04 | [39] |

| c.3055_3059dup | p.Met1020IlefsTer4 | het | 9 | [43] | ||||||||

| Fi25/09_01 | CRD_1 | CRD | c.498_506delAATTGATGG | p.Ile167_Gly169del | het | 2 | 10 | late childhood | 48 | 0.1 | 0.1 | [39] |

| c.2843G>A | (Splice) p.Cys948Tyr | het | 9 | [44] | ||||||||

| Fi15/29_01 | CRD_2 | PPRPE | c.498_506delAATTGATGG | p.Ile167_Gly169del | het | 2 | 0 | infancy | 47 | LP | HM | [39] |

| c.2843G>A | (Splice) p.Cys948Tyr | het | 9 | [44] | ||||||||

| Fi25/20_01 | CRD_3 | PPRPE | c.2290C>T | p.Arg764Cys | homo | 7 | 6 | late childhood | 31 | 0.5 | 0.16 | [44] |

| Fi25/20_02 | CRD_4 | PPRPE | c.2290C>T | p.Arg764Cys | homo | 7 | ? | 36 | 0.04 | 0.04 | [44] | |

| Fi25/10_01 | CRD_5 | CRD | c.498_506delAATTGATGG | p.Ile167_Gly169del | het | 2 | 12 | late childhood | 58 | 0.05 | 0.05 | [39] |

| c.1604T>C | p.Leu535Pro | het | 6 | [45] | ||||||||

| Fi25/11_01 | CRD_6 | CRD | c.498_506delAATTGATGG | p.Ile167_Gly169del | homo | 2 | <20 | adolescence | 64 | 0.06 | 0.06 | [39] |

| c.1360G>A | p.Gly454Arg | homo | 6 | [46] | ||||||||

| Fi25/12_01 | CRD_7 | CRD | c.742T>A | p.Cys248Ser | het | 3 | 17 | adolescence | 39 | 0.05 | 0.05 | This study |

| c.4005+1G>A | - | het | 11 | [47] | ||||||||

| Fi25/13_01 | CRD_8 | CRD | c.407G>T | p.Cys136Phe | het | 2 | 7 | late childhood | 57 | LP | 0.2 | This study |

| c.2843G>A | (Splice) p.Cys948Tyr | het | 9 | [44] | ||||||||

| Fi25/14_01 | CRD_9 | CRD | c.1760G>A | p.Cys587Tyr | het | 6 | 7 | late childhood | 67 | LP | LP | [6] |

| c.2843G>A | (Splice) p.Cys948Tyr | het | 9 | [44] | ||||||||

| Fi25/15_01 | LCA_1 | LCA | c.613_619delATAGGAA | p.Ile205AspfsTer13 | het | 2 | <2 | infancy | 20 | 0.04 | 0.04 | [48] |

| c.2290C>T | p.Arg764Cys | het | 7 | [44] | ||||||||

| Fi25/15_02 | LCA_2 | LCA | c.613_619delATAGGAA | p.Ile205AspfsTer13 | het | 2 | <2 | infancy | 15 | 0.04 | 0.05 | [48] |

| c.2290C>T | p.Arg764Cys | het | 7 | [44] | ||||||||

| Fi15/13_01 | LCA_3 | LCA | c.613_619delATAGGAA | p.Ile205AspfsTer13 | het | 2 | <2 | infancy | 11 | 0.2 | 0.1 | [48] |

| c.2843G>A | (Splice) p.Cys948Tyr | het | 9 | [44] | ||||||||

| Fi25/21_01 | LCA_4 | LCA | c.2843G>A | (Splice) p.Cys948Tyr | homo | 9 | <2 | infancy | 23 | 0.05 | 0.05 | [44] |

| Fi25/16_01 | LCA_5 | LCA | c.613_619delATAGGAA | p.Ile205AspfsTer13 | homo | 2 | <2 | infancy | 46 | 0.01 | 0.04 | [48] |

| Fi25/17_01 | LCA_6 | LCA | c.3280C>T | p.Gln1094Ter | homo | 9 | <2 | infancy | 16 | 0.016 | 0.025 | This study |

| Fi25/18_01 | LCA_7 | LCA | c.209delT | p.Met70ArgfsTer17 | het | 2 | <2 | infancy | 32 | HM | HM | This study |

| c.2843G>A | (Splice) p.Cys948Tyr | het | 9 | [44] | ||||||||

| Fi25/19_01 | LCA_8 | LCA | c.2843G>A | (Splice) p.Cys948Tyr | het | 9 | <2 | infancy | 50 | - | - | [44] |

| c.3988G>T | p.Glu1330Ter | het | 11 | [45] | ||||||||

| Fi25/22_02 | LCA_9 | LCA | c.2843G>A | (Splice) p.Cys948Tyr | het | 9 | 6 months | infancy | 48 | HM | LP | [44] |

| c.3749+2_3749+3delTG | - | het | 9 | [49] | ||||||||

| Fi25/22_01 | LCA_10 | LCA | c.3749+2_3749+3delTG | - | homo | 9 | <2 | infancy | 70 | NLP | NLP | [49] |

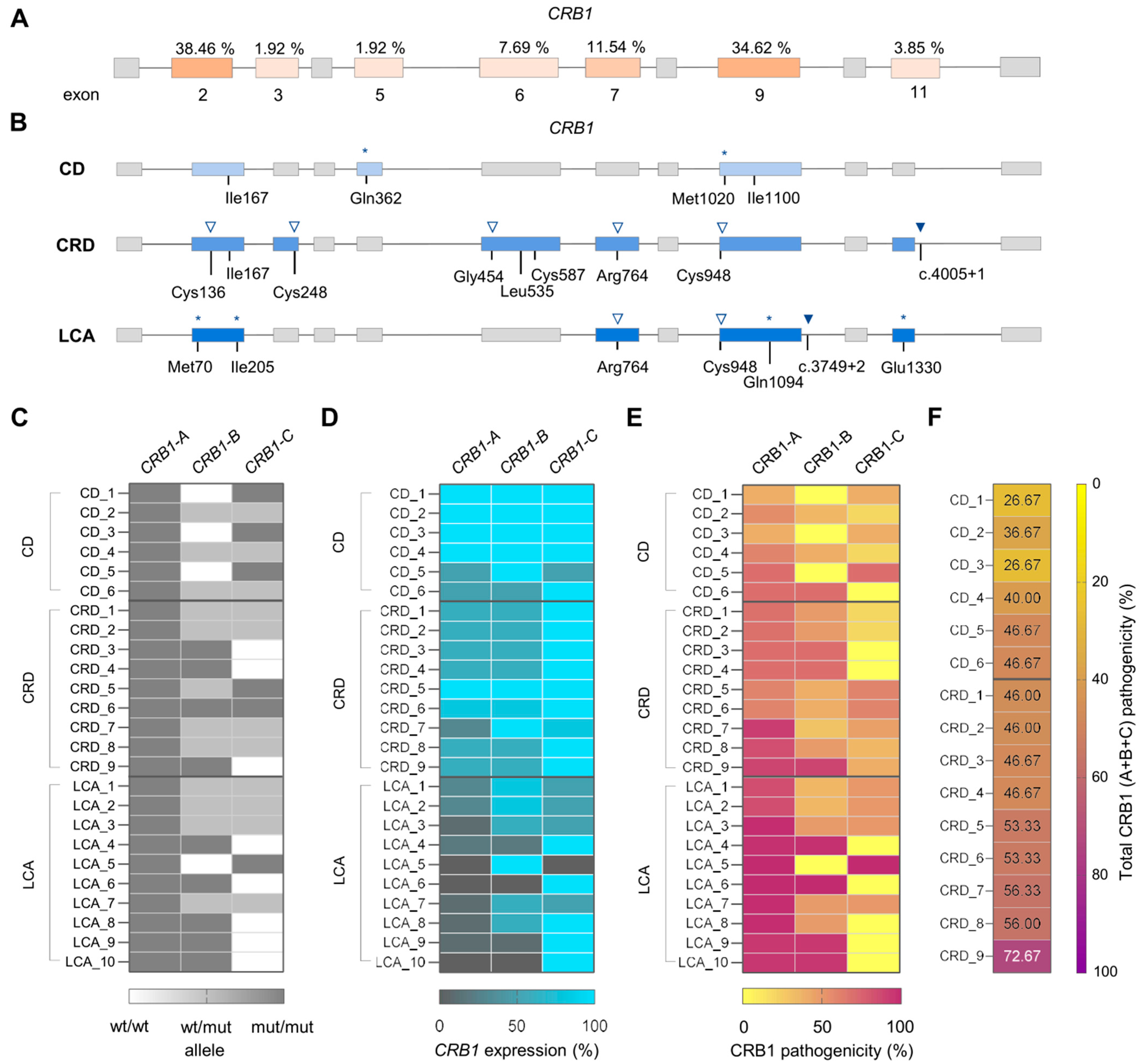

2.3. Impact of the Pathogenic Variants on CRB1 Isoforms Determines IRD Clinical Manifestation

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Patients and Clinical Evaluation

4.2. Next-Generation Sequencing and Identification of Pathogenic Variants

4.3. Estimation of CRB1 Mutations Impact on Pathogenicity

4.4. Human iPSCs Culture and Differentiation into Retinal Cell Models

4.5. PCR Amplification and Sanger Sequencing

4.6. Immunofluorescence and Image Analysis

4.7. RNA Extraction and Real-Time PCR

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ganapathi, M.; Thomas-Wilson, A.; Buchovecky, C.; Dharmadhikari, A.; Barua, S.; Lee, W.; Ruan, M.Z.C.; Soucy, M.; Ragi, S.; Tanaka, J.; et al. Clinical exome sequencing for inherited retinal degenerations at a tertiary care center. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 9358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manley, A.; Meshkat, B.I.; Jablonski, M.M.; Hollingsworth, T.J. Cellular and Molecular Mechanisms of Pathogenesis Underlying Inherited Retinal Dystrophies. Biomolecules 2023, 13, 271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vallespin, E.; Cantalapiedra, D.; Riveiro-Alvarez, R.; Wilke, R.; Aguirre-Lamban, J.; Avila-Fernandez, A.; Lopez-Martinez, M.A.; Gimenez, A.; Trujillo-Tiebas, M.J.; Ramos, C.; et al. Mutation screening of 299 Spanish families with retinal dystrophies by leber congenital amaurosis genotyping microarray. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2007, 48, 5653–5661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quinn, P.M.; Pellissier, L.P.; Wijnholds, J. The CRB1 complex: Following the trail of crumbs to a feasible gene therapy strategy. Front. Neurosci. 2017, 11, 175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alves, C.H.; Pellissier, L.P.; Wijnholds, J. The CRB1 and adherens junction complex proteins in retinal development and maintenance. Prog. Retin. Eye Res. 2014, 40, 35–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Den Hollander, A.I.; Davis, J.; Van Der Velde-Visser, S.D.; Zonneveld, M.N.; Pierrottet, C.O.; Koenekoop, R.K.; Kellner, U.; Van Den Born, L.I.; Heckenlively, J.R.; Hoyng, C.B.; et al. CRB1 mutation spectrum in inherited retinal dystrophies. Hum. Mutat. 2004, 24, 355–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Margolis, B. Apical junctional complexes and cell polarity. Kidney Int. 2007, 72, 1448–1458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehalow, A.K.; Kameya, S.; Smith, R.S.; Hawes, N.L.; Denegre, J.M.; Young, J.A.; Bechtold, L.; Haider, N.B.; Tepass, U.; Heckenlively, J.R.; et al. CRB1 is essential for external limiting membrane integrity and photoreceptor morphogenesis in the mammalian retina. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2003, 12, 2179–2189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van de Pavert, S.A.; Kantardzhieva, A.; Malysheva, A.; Meuleman, J.; Versteeg, I.; Levelt, C.; Klooster, J.; Geiger, S.; Seeliger, M.W.; Rashbass, P.; et al. Crumbs homologue 1 is required for maintenance of photoreceptor cell polarization and adhesion during light exposure. J. Cell Sci. 2004, 117, 4169–4177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobson, S.G.; Cideciyan, A.V.; Aleman, T.S.; Pianta, M.J.; Sumaroka, A.; Schwartz, S.B.; Smilko, E.E.; Milam, A.H.; Sheffield, V.C.; Stone, E.M. Crumbs homolog 1 (CRB1) mutations result in a thick human retina with abnormal lamination. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2003, 12, 1073–1078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Son, S.; Cho, M.; Lee, J. Crumbs proteins regulate layered retinal vascular development required for vision. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2019, 521, 939–946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quinn, P.M.J.; Wijnholds, J. Retinogenesis of the human fetal retina: An apical polarity perspective. Genes 2019, 10, 987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pellissier, L.P.; Lundvig, D.M.S.; Tanimoto, N.; Klooster, J.; Vos, R.M.; Richard, F.; Sothilingam, V.; Garrido, M.G.; Bivic, A.L.; Seeliger, M.W.; et al. CRB2 acts as a modifying factor of CRB1-related retinal dystrophies in mice. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2014, 23, 3759–3771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pellissier, L.P.; Quinn, P.M.; Henrique Alves, C.; Vos, R.M.; Klooster, J.; Flannery, J.G.; Alexander Heimel, J.; Wijnholds, J. Gene therapy into photoreceptors and Müller glial cells restores retinal structure and function in CRB1 retinitis pigmentosa mouse models. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2014, 24, 3104–3118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ray, T.A.; Cochran, K.; Kozlowski, C.; Wang, J.; Alexander, G.; Cady, M.A.; Spencer, W.J.; Ruzycki, P.A.; Clark, B.S.; Laeremans, A.; et al. Comprehensive identification of mRNA isoforms reveals the diversity of neural cell-surface molecules with roles in retinal development and disease. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 3328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dyer, S.C.; Austine-Orimoloye, O.; Azov, A.G.; Barba, M.; Barnes, I.; Barrera-Enriquez, V.P.; Becker, A.; Bennett, R.; Beracochea, M.; Berry, A.; et al. Ensembl 2025. Nucleic Acids Res. 2025, 53, D948–D957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mairot, K.; Smirnov, V.; Bocquet, B.; Labesse, G.; Arndt, C.; Defoort-dhellemmes, S.; Zanlonghi, X.; Hamroun, D.; Denis, D.; Picot, M.C.; et al. Crb1-related retinal dystrophies in a cohort of 50 patients: A reappraisal in the light of specific müller cell and photoreceptor crb1 isoforms. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 12642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moon, S.Y.; Zhang, D.; Chen, S.-C.; Lamey, T.M.; Thompson, J.A.; McLaren, T.L.; Chen, F.K.; McLenachan, S. Rapid Variant Pathogenicity Analysis by CRISPR Activation of CRB1 Gene Expression in Patient-Derived Fibroblasts. Cris. J. 2024, 7, 100–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, S.; Li, J.J.; Song, W.; Li, Y.; Zeng, L.; Liang, Q.; Wen, X.; Shang, H.; Liu, K.; Peng, P.; et al. CRB1-associated retinal degeneration is dependent on bacterial translocation from the gut. Cell 2024, 187, 1387–1401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Liang, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Cui, Z.; Gu, J.; Xiong, S.; Chen, J. CRB1 mutations cause structural and molecular defects in patient-derived retinal pigment epithelium cells. Exp. Eye Res. 2025, 257, 110445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Zhao, L.; Wang, C.; Sun, W.; Jia, B.; Li, D.; Fu, J. Diverse functions and pathogenetic role of Crumbs in retinopathy. Cell Commun. Signal. 2024, 22, 290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsang, S.H.; Sharma, T. Leber Congenital Amaurosis. In Atlas of Inherited Retinal Diseases; Tsang, S.H., Sharma, T., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 131–137. ISBN 978-3-319-95046-4. [Google Scholar]

- Tsang, S.H.; Sharma, T. Progressive Cone Dystrophy and Cone-Rod Dystrophy (XL, AD, and AR). In Atlas of Inherited Retinal Diseases; Tsang, S.H., Sharma, T., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 53–60. ISBN 978-3-319-95046-4. [Google Scholar]

- Daiger, S.P.; Sullivan, L.S.; Bowne, S.J. Genes and mutations causing retinitis pigmentosa. Clin. Genet 2013, 84, 132–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ray, T.A.; Cochran, K.J.; Kay, J.N. The Enigma of CRB1 and CRB1 Retinopathies. In Retinal Degenerative Diseases; Bowes Rickman, C., Grimm, C., Anderson, R.E., Ash, J.D., LaVail, M.M., Hollyfield, J.G., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 251–255. [Google Scholar]

- Stenson, P.D.; Mort, M.; Ball, E.V.; Chapman, M.; Evans, K.; Azevedo, L.; Hayden, M.; Heywood, S.; Millar, D.S.; Phillips, A.D.; et al. The Human Gene Mutation Database (HGMD(®)): Optimizing its use in a clinical diagnostic or research setting. Hum. Genet. 2020, 139, 1197–1207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Georgiou, M.; Fujinami, K.; Michaelides, M. Inherited retinal diseases: Therapeutics, clinical trials and end points—A review. Clin. Exp. Ophthalmol. 2021, 49, 270–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slavotinek, A.M. The Family of Crumbs Genes and Human Disease. Mol. Syndromol. 2016, 7, 274–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ehrenberg, M.; Pierce, E.A.; Cox, G.F.; Fulton, A.B. CRB1: One gene, many phenotypes. Semin. Ophthalmol. 2013, 28, 397–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Motta, F.L.; Salles, M.V.; Costa, K.A.; Filippelli-Silva, R.; Martin, R.P.; Sallum, J.M.F. The correlation between CRB1 variants and the clinical severity of Brazilian patients with different inherited retinal dystrophy phenotypes. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 8654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bujakowska, K.; Audo, I.; Mohand-Saïd, S.; Lancelot, M.E.; Antonio, A.; Germain, A.; Léveillard, T.; Letexier, M.; Saraiva, J.P.; Lonjou, C.; et al. CRB1 mutations in inherited retinal dystrophies. Hum. Mutat. 2012, 33, 306–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodriguez Martinez, A.C.; Mejecase, C.; Tailor, V.; Elora Higgins, B.; Henderson, R.; Moosajee, M. Novel genotype-phenotype correlations in CRB1-retinopathies: Insights from isoforms and protein domains linked to disease severity. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2025, 66, 1220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daher, A.; Banjak, M.; Noureldine, J.; Nehme, J.; El Shamieh, S. Genotype-phenotype associations in CRB1 bi-allelic patients: A novel mutation, a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Ophthalmol. 2024, 24, 167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez-Martinez, A.C.; Marmoy, O.R.; Prise, K.L.; Henderson, R.H.; Thompson, D.A.; Moosajee, M. Expanding the Clinical Spectrum of CRB1-Retinopathies: A Novel Genotype–Phenotype Correlation with Macular Dystrophy and Elevated Intraocular Pressure. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 2836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.-Y.; Gao, F.-J.; Ju, Y.-Q.; Guo, L.-Y.; Duan, C.; Chang, Q.; Zhang, T.; Xu, G.-Z.; Du, H.; Zong, Y.; et al. Clinical and mutational signatures of CRB1-associated retinopathies: A multicentre study. J. Med. Genet. 2025, 62, 6–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boon, N.; Wijnholds, J.; Pellissier, L.P. Research Models and Gene Augmentation Therapy for CRB1 Retinal Dystrophies. Front. Neurosci. 2020, 14, 860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pfaffl, M.W. A new mathematical model for relative quantification in real-time RT-PCR. Nucleic Acids Res. 2001, 29, e45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, K.N.; Robson, A.; Mahroo, O.A.R.; Arno, G.; Inglehearn, C.F.; Armengol, M.; Waseem, N.; Holder, G.E.; Carss, K.J.; Raymond, L.F.; et al. A clinical and molecular characterisation of CRB1-associated maculopathy. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 2018, 26, 687–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vallespin, E.; Cantalapiedra, D.; Garcia-Hoyos, M.; Riveiro, R.; Villaverde, C.; Trujillo-Tiebas, M.J.; Ayuso, C. Gene symbol: CRB1. Disease: Leber congenital amaurosis. Accession #Hd0510. Hum. Genet. 2006, 118, 774. [Google Scholar]

- Bernal, S.; Calaf, M.; Garcia-Hoyos, M.; Garcia-Sandoval, B.; Rosell, J.; Adan, A.; Ayuso, C.; Baiget, M. Study of the involvement of the RGR, CRPB1, and CRB1 genes in the pathogenesis of autosomal recessive retinitis pigmentosa. J. Med. Genet. 2003, 40, e89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Den Hollander, A.I.; Heckenlively, J.R.; van den Born, L.I.; De Kok, Y.J.M.; Van der Velde-Visser, S.D.; Kellner, U.; Jurklies, B.; Van Schooneveld, M.J.; Blankenagel, A.; Rohrschneider, K.; et al. Leber congenital amaurosis and retinitis pigmentosa with coats-like exudative vasculopathy are associated with mutations in the crumbs homologue 1 (CRB1) gene. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2001, 69, 198–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yzer, S.; Leroy, B.P.; De Baere, E.; De Ravel, T.J.; Zonneveld, M.N.; Voesenek, K.; Kellner, U.; Martinez Ciriano, J.P.; De Faber, J.T.H.N.; Rohrschneider, K.; et al. Microarray-based mutation detection and phenotypic characterization of patients with leber congenital amaurosis. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2006, 47, 1167–1176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Pozo-Valero, M.; Riveiro-Alvarez, R.; Martin-Merida, I.; Blanco-Kelly, F.; Swafiri, S.; Lorda-Sanchez, I.; Trujillo-Tiebas, M.J.; Carreño, E.; Jimenez-Rolando, B.; Garcia-Sandoval, B.; et al. Impact of Next Generation Sequencing in Unraveling the Genetics of 1036 Spanish Families With Inherited Macular Dystrophies. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2022, 63, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Den Hollander, A.I.; Ten Brink, J.B.; De Kok, Y.J.M.; Van Soest, S.; Van Den Born, L.I.; Van Driel, M.A.; Van De Pol, D.J.R.; Payne, A.M.; Bhattacharya, S.S.; Kellner, U.; et al. Mutations in a human homologue of Drosophila crumbs cause retinitis pigmentosa (RP12). Nat. Genet. 1999, 23, 217–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vallespin, E.; Cantalapiedra, D.; Garcia-Hoyos, M.; Riveiro, R.; Queipo, A.; Trujillo-Tiebas, M.J.; Ayuso, C. Gene symbol: CRB1. Disease: Leber congenital amaurosis. Accession #Hm0540. Hum. Genet. 2006, 118, 778. [Google Scholar]

- Walia, S.; Fishman, G.A.; Jacobson, S.G.; Aleman, T.S.; Koenekoop, R.K.; Traboulsi, E.I.; Weleber, R.G.; Pennesi, M.E.; Heon, E.; Drack, A.; et al. Visual Acuity in Patients with Leber’s Congenital Amaurosis and Early Childhood-Onset Retinitis Pigmentosa. Ophthalmology 2010, 117, 1190–1198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanein, S.; Perrault, I.; Gerber, S.; Tanguy, G.; Barbet, F.; Ducroq, D.; Calvas, P.; Dollfus, H.; Hamel, C.; Lopponen, T.; et al. Leber Congenital Amaurosis: Comprehensive Survey of the Genetic Heterogeneity, Refinement of the Clinical Definition, and Genotype-Phenotype Correlations as a Strategy for Molecular Diagnosis. Hum. Mutat. 2004, 23, 306–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lotery, A.J.; Jacobson, S.G.; Fishman, G.A.; Weleber, R.G.; Fulton, A.B.; Namperumalsamy, P.; Héon, E.; Levin, A.V.; Grover, S.; Rosenow, J.R.; et al. Mutations in the CRB1 gene cause Leber congenital amaurosis. Arch. Ophthalmol. 2001, 119, 415–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corton, M.; Tatu, S.D.; Avila-Fernandez, A.; Vallespín, E.; Tapias, I.; Cantalapiedra, D.; Blanco-Kelly, F.; Riveiro-Alvarez, R.; Bernal, S.; García-Sandoval, B.; et al. High frequency of CRB1 mutations as cause of Early-Onset Retinal Dystrophies in the Spanish population. Orphanet J. Rare Dis. 2013, 8, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, J.; Novati, G.; Pan, J.; Bycroft, C.; Žemgulyte, A.; Applebaum, T.; Pritzel, A.; Wong, L.H.; Zielinski, M.; Sargeant, T.; et al. Accurate proteome-wide missense variant effect prediction with AlphaMissense. Science 2023, 381, eadg7492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muskal, S.M.; Holbrook, S.R.; Kim, S.H. Prediction of the disulfide-bonding state of cysteine in proteins. Protein Eng. Des. Sel. 1990, 3, 667–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Sun, W.; Xiao, X.; Li, S.; Jia, X.; Wang, P.; Zhang, Q. Clinical and Genetic Analysis of 63 Families Demonstrating Early and Advanced Characteristic Fundus as the Signature of CRB1 Mutations. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 2021, 223, 160–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cañibano-Hernández, A.; Valdes-Sanchez, L.; Garcia-Delgado, A.B.; Ponte-Zúñiga, B.; Diaz-Corrales, F.J.; de la Cerda, B. Generation of the human iPSC line ESi082-A from a patient with macular dystrophy associated to mutations in the CRB1 gene. Stem Cell Res. 2021, 53, 102301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shamsnajafabadi, H.; Kaukonen, M.; Bellingrath, J.-S.; MacLaren, R.E.; Cehajic-Kapetanovic, J. In Silico CRISPR-Cas-Mediated Base Editing Strategies for Early-Onset, Severe Cone–Rod Retinal Degeneration in Three Crumbs homolog 1 Patients, including the Novel Variant c.2833G>A. Genes 2024, 15, 625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Laey, J.J. Leber’s congenital amaurosis. Bull. Soc. Belge Ophtalmol. 1991, 241, 41–50. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmad, S.; Jose da Costa Gonzales, L.; Bowler-Barnett, E.H.; Rice, D.L.; Kim, M.; Wijerathne, S.; Luciani, A.; Kandasaamy, S.; Luo, J.; Watkins, X.; et al. The UniProt website API: Facilitating programmatic access to protein knowledge. Nucleic Acids Res. 2025, 53, W547–W553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riera, M.; Patel, A.; Corcostegui, B.; Chang, S.; Sparrow, J.R.; Pomares, E.; Corneo, B. Establishment and characterization of an iPSC line (FRIMOi001-A) derived from a retinitis pigmentosa patient carrying PDE6A mutations. Stem Cell Res. 2019, 35, 101385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnea-Cramer, A.O.; Wang, W.; Lu, S.J.; Singh, M.S.; Luo, C.; Huo, H.; McClements, M.E.; Barnard, A.R.; MacLaren, R.E.; Lanza, R. Function of human pluripotent stem cell-derived photoreceptor progenitors in blind mice. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 29784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Regent, F.; Morizur, L.; Lesueur, L.; Habeler, W.; Plancheron, A.; Ben M’Barek, K.; Monville, C. Automation of human pluripotent stem cell differentiation toward retinal pigment epithelial cells for large-scale productions. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 10646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez-Cordero, A.; Kruczek, K.; Naeem, A.; Fernando, M.; Kloc, M.; Ribeiro, J.; Goh, D.; Duran, Y.; Blackford, S.J.I.; Abelleira-Hervas, L.; et al. Recapitulation of Human Retinal Development from Human Pluripotent Stem Cells Generates Transplantable Populations of Cone Photoreceptors. Stem Cell Rep. 2017, 9, 820–837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| nt Change | Protein Change | dbSNP a | MAF b | Predictors c |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| c.209delT | p.Met70ArgfsTer17 | Not referenced | Not referenced | truncating |

| c.407G>T | p.Cys136Phe | rs752559648 | Not referenced | 12D |

| c.742T>A | p.Cys248Ser | rs769980214 | A = 0.000002 (1/595,670) | 14D |

| c.3280C>T | p.Gln1094Ter | Not referenced | Not referenced | truncating |

| Missense Impact | Splice Impact | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variant a | Protein Change | Predictors b | Pathogenicity Estimation c | Predictors b | Pathogenicity Estimation d |

| * c.407G>T | p.Cys136Phe | 12D | 70% | 1G | 20% |

| * c.742T>A | p.Cys248Ser | 14D | 80% | 2G | 40% |

| c.1360G>A | p.Gly454Arg | 14D | 80% | 2G | 40% |

| c.1604T>C | p.Leu535Pro | 14D | 80% | -- | -- |

| c.1760G>A | p.Cys587Tyr | 13D | 80% | -- | -- |

| c.2290C>T | p.Arg764Cys | 6D | 50% | 2G | 40% |

| c.2843G>A | p.Cys948Tyr | 14D | 80% | 4L | 80% |

| c.3299T>C | p.Ile1100Thr | 11D | 70% | -- | -- |

| c.3299T>G | p.Ile1100Arg | 14D | 80% | -- | -- |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Siles, L.; Ruiz-Nogales, S.; Méndez-Vendrell, P.; Burés-Jelstrup, A.; Navarro, R.; Pomares, E. The Specific Pathogenicity Pattern of the Different CRB1 Isoforms Conditions Clinical Severity in Inherited Retinal Dystrophies. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 11551. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311551

Siles L, Ruiz-Nogales S, Méndez-Vendrell P, Burés-Jelstrup A, Navarro R, Pomares E. The Specific Pathogenicity Pattern of the Different CRB1 Isoforms Conditions Clinical Severity in Inherited Retinal Dystrophies. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2025; 26(23):11551. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311551

Chicago/Turabian StyleSiles, Laura, Sheila Ruiz-Nogales, Pilar Méndez-Vendrell, Anniken Burés-Jelstrup, Rafael Navarro, and Esther Pomares. 2025. "The Specific Pathogenicity Pattern of the Different CRB1 Isoforms Conditions Clinical Severity in Inherited Retinal Dystrophies" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 26, no. 23: 11551. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311551

APA StyleSiles, L., Ruiz-Nogales, S., Méndez-Vendrell, P., Burés-Jelstrup, A., Navarro, R., & Pomares, E. (2025). The Specific Pathogenicity Pattern of the Different CRB1 Isoforms Conditions Clinical Severity in Inherited Retinal Dystrophies. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 26(23), 11551. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311551