1. Introduction

The number of individuals with overweight, obesity, and type 2 diabetes has been steadily increasing over recent decades, representing one of the major challenges in modern healthcare [

1]. These conditions are closely associated with disturbances in carbohydrate and lipid metabolism and increase the risk of cardiovascular diseases, insulin resistance, and metabolic syndrome [

2]. Consequently, there is active research aimed at finding effective and safe methods for body weight and metabolic status correction, among which optimizing dietary regimens occupies a central role. However, contradictory scientific data regarding the efficacy of various eating patterns lead to ambiguity in practical dietary recommendations.

A commonly employed strategy remains the reduction in total daily caloric intake. Although this approach is proven effective for short-term weight loss, the results are rarely sustained: most individuals regain their original body weight or even gain additional weight after completing the diet [

3]. As an alternative, diets with altered macronutrient ratios but maintained total caloric intake are being studied [

4,

5,

6,

7]. Despite certain metabolic effects observed with such regimens, their application may be accompanied by adverse health consequences, particularly in individuals predisposed to metabolic disorders [

6,

7].

The issue of meal frequency remains particularly controversial. On one hand, proponents of infrequent eating (1–2 times per day) emphasize its effectiveness in reducing body weight, associating this with prolonged fasting intervals and activation of lipolytic processes [

8]. On the other hand, frequent small meals (5–6 times per day) are recommended, purportedly to stabilize glucose and insulin level, boost metabolism, and control appetite [

9]. However, empirical data on this matter are contradictory, and the mechanisms underlying the impact of feeding patterns on lipid metabolism are still insufficiently understood.

The traditional obesity model, based on the balance between energy intake and expenditure, is gradually being supplemented by alternative concepts, notably the carbohydrate–insulin model [

10]. According to this model, a high-carbohydrate diet leads to hypersecretion of insulin, which in turn promotes fat accumulation in adipocytes and inhibits its mobilization. Although this concept currently has limited empirical support and remains controversial [

11], it highlights the importance of studying insulin’s role not only as a hormone regulating glucose level but also as a key factor determining the balance between lipogenesis and lipolysis.

Adipocytes, the primary cells of adipose tissue, serve as the main site for energy storage in the form of triglycerides. Insulin plays a central role in regulating triglyceride accumulation: it stimulates the transport of glucose and fatty acids into the cell, activates triglyceride synthesis, and, importantly, suppresses lipolysis [

12,

13]. Insulin secretion, in turn, depends on the dynamics of glucose entry into the bloodstream, which is determined by the feeding pattern. Despite extensive research on plasma glucose and insulin dynamics [

14,

15,

16], as well as changes in insulin resistance under various diets and pathologies [

17], the direct effect of dynamic characteristics of the insulin response, such as amplitude, duration, and frequency of peaks, on triglyceride accumulation in adipocytes remains insufficiently studied. There is limited empirical data directly linking meal frequency to triglyceride accumulation via insulin dynamics under isocaloric conditions.

Mathematical modeling provides a powerful tool for analyzing complex metabolic systems, particularly the carbohydrate–lipid metabolism, allowing the isolation and evaluation of contributions from individual factors that are inaccessible through standard empirical studies. Previously developed models described the dynamics of glucose, insulin, and free fatty acids in plasma [

18], the effects of caloric restriction on insulin resistance [

19], or the impacts of isocaloric diets with varying macronutrient ratios [

20]. However, these models do not consider the influence of the dynamic characteristics of hormonal responses.

In this work, a mathematical model of the carbohydrate–lipid metabolism in plasma and adipocytes is presented, incorporating insulin regulation of key metabolic processes. Using this model, we investigated how meal frequency, under constant daily caloric intake, affects triglyceride accumulation in adipocytes, and proposed that the dynamic insulin profile may serve as a critical factor regulating the balance between lipolysis and fat storage.

2. Results

2.1. General Scheme of Lipid Metabolism Reactions

In this study, changes in body fat mass were assessed by estimating triglyceride accumulation in adipocytes. This evaluation method is simplified but is considered acceptable at an introductory level as it is widely accepted that adipocyte number remains constant in adults [

21]. Therefore, changes in intracellular triglyceride levels directly reflect the corresponding changes in body mass driven by alterations in adipose tissue volume.

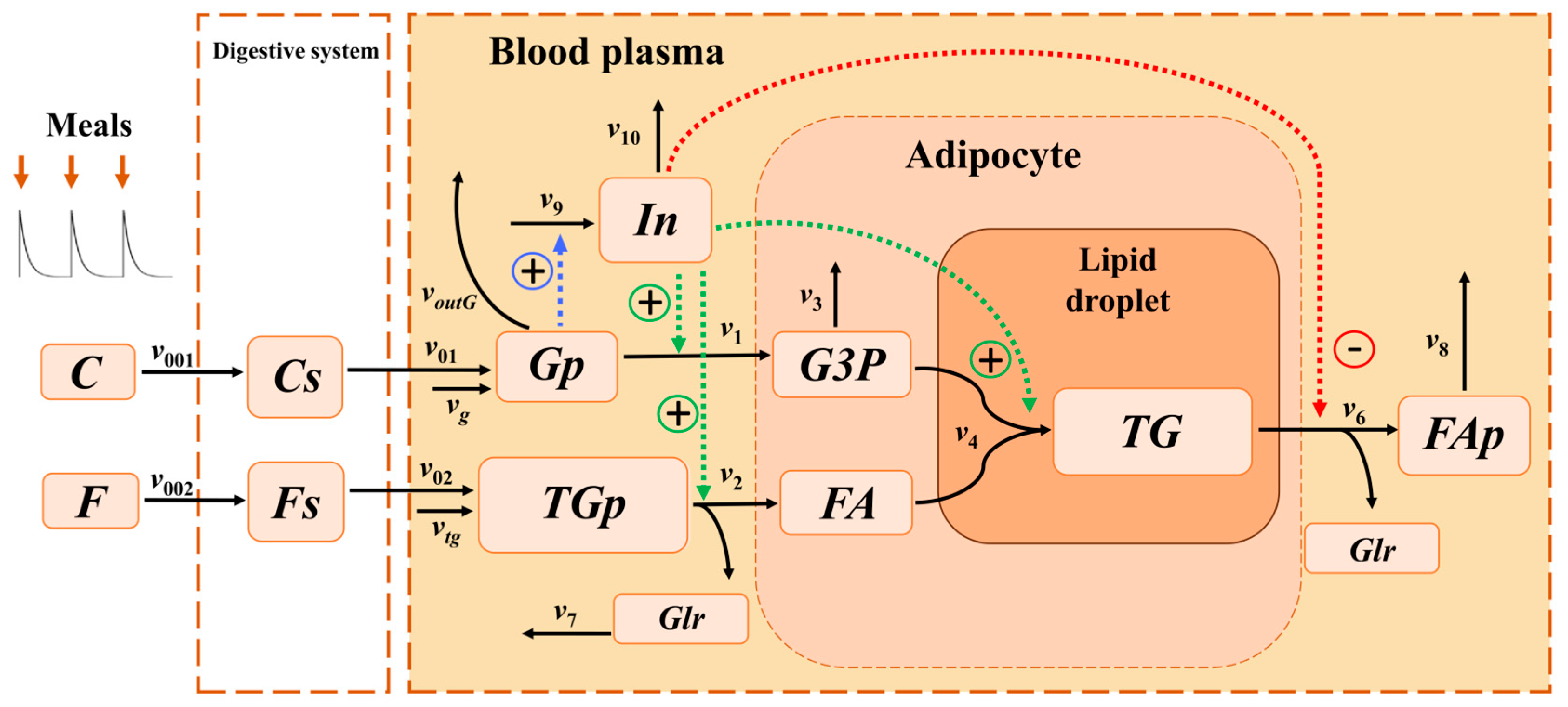

To investigate the mechanism of triglyceride accumulation at different feeding frequencies, a multi-compartment model was created, integrating processes in the digestive system, blood plasma, and adipocyte. The model included all key reactions involved in triglyceride synthesis (

Figure 1).

Based on the approaches presented in [

19,

22], protein metabolic processes were excluded from the model, as their impact on lipid and carbohydrate metabolism under physiological conditions is insignificant. The intake of food into the digestive system was modeled as a periodic input of macronutrients carbohydrates

C and fats

F (see

Section 4 for detailed description). This input determined corresponding periodic changes in all metabolites within the model. Carbohydrates

C entered the digestive system with food at a rate of

, and fats

F at a rate of

. Carbohydrates

Cs and fats

Fs in the digestive system were then transported from the digestive system into the blood plasma as glucose

Gp and triglycerides

TGp at rates of

and

, respectively.

In the blood plasma, triglycerides (TGp) underwent lipolysis, yielding one molecule of glycerol (Glr) per one molecule of TGp, which was transported to other organs and tissues at a rate of , and three molecules of fatty acids (FA), which entered the adipocyte at a rate of . In addition to the intake of triglycerides TGp from food, their influx from the liver was considered at a constant rate .

Glucose (Gp) was transported from blood plasma into adipocytes, where it underwent glycolysis to form glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate (G3P), with an effective reaction rate of . In addition to dietary glucose uptake, a constant flux of glucose from the liver was accounted for, with rate . The outflow of glucose (Gp) from plasma to other organs was modeled as . A fraction of G3P molecules was allocated to other metabolic pathways of other cellular metabolic processes at rate . The remaining G3P served as a source of the glycerol backbone and reacted with fatty acids (FA) to form triglycerides (TG) stored in the lipid droplet of the adipocyte at rate . One molecule of triglyceride was synthesized from one molecule of G3P and three molecules of FA.

Triglycerides within the adipocyte lipid droplet (TG) underwent lipolysis, yielding one molecule of glycerol (Glr) and three molecules of fatty acids (FAp) per triglyceride molecule; these fatty acids were subsequently transported back into the bloodstream. Lipolysis of TG followed by the export of fatty acids (FAp) into plasma was described by a reaction with rate . Fatty acids in plasma (FAp) were then transported to other organs and tissues at rate .

2.2. Mathematical Model of Triglyceride Accumulation in Adipocytes

All reactions, except for triglyceride lipolysis in adipocytes (), were formulated according to the law of mass action. To describe triglyceride lipolysis (), it was taken into account that the concentration of triglycerides constituting the lipid droplet within the adipocyte was substantially higher than that of other metabolites. Taking into account this assumption, we assumed that the hydrolysis of lipid droplet triglycerides proceeds under substrate-saturated conditions, i.e., the reaction rate was independent of triglyceride concentration.

The model was described by the system of differential Equation (1) of the form:

where

Xi denoted the concentration of

i-th metabolite in either blood plasma or in adipocytes,

represented the net rate of change due to transport, synthesis, or degradation (see

Table 1). To convert fluxes from concentration-based units (e.g., mmol L

−1h

−1) to absolute amounts (mmol h

−1), each reaction rate was multiplied by a compartment-specific volumetric scaling factor: linearly for unimolecular reactions and quadratically for bimolecular reactions, reflecting the dependence of reaction flux on molecular stoichiometry and compartment volume. Specifically,

scaled plasma reactions, and

scaled those occurring in adipose tissue.

2.3. Insulin Regulation of Fat Metabolism Reactions

To focus specifically on processes within adipocytes, we adopted an idealized modeling framework. We considered a scenario of minimal physical exertion, where insulin serves as the primary hormonal regulator of lipid metabolism. This allowed us to isolate the effect of insulin dynamics from confounding factors such as hormonal signals arising from physical activity. Hormones other than insulin were excluded from the model because, under the simulated conditions, insulin exerts a dominant and direct regulatory influence on both lipogenesis and lipolysis in adipose tissue.

In the model, insulin acted as an effector, which activated the transport of glucose and fatty acids into the adipocyte in reactions and , respectively, and the synthesis of lipid droplet triglycerides in reaction . It also inhibited the lipolysis of lipid droplet triglycerides in reaction . Although the glucose release from the liver is known to decrease after meal intake due to insulin-mediated suppression of glycogenolysis and gluconeogenesis, in our model this flux was represented as a constant rate . This simplification was adopted to maintain a stable baseline for plasma glucose concentration. The dependence of glucose outflow from plasma on insulin was not included in the model, as we considered the combined effective outflows to various organs. Under resting conditions, the fraction of glucose consumed by insulin-dependent tissues (such as muscle) was relatively small compared to consumption by insulin-independent tissues (e.g., brain, kidneys). Therefore, the total glucose outflow was assumed proportional to its plasma concentration and independent of insulin levels. Insulin activation of i-th reactions was modeled by a linear function , reflecting the proportional dependence of the rate on the hormone concentration. Inhibition, conversely, was described by a hyperbolic function , accounting for the saturable suppression of lipolysis with increasing insulin level. The parameters and characterize the sensitivity of the corresponding reactions to insulin.

Blood plasma insulin level is highly dependent on glucose concentration in blood plasma, while amino acids, ketone bodies, and fatty acids have a significantly smaller effect on insulin secretion [

23,

24]. In the suggested mathematical model, insulin secretion, dependent only on plasma glucose concentration, occurs at a rate of

, and its degradation occurs at a rate of

. The dependence of the rate of insulin secretion on blood glucose concentration is known to have an S-shaped curve [

25]. To describe the rate of insulin secretion

, we used a phenomenological expression that allows us to reproduce the shape of the sigmoidal dependence of the rate on the concentration of glucose

Gp in the blood plasma:

, where

characterizes the maximum rate of insulin secretion,

a is the concentration of glucose at the inflection point, and

b characterizes the range of glucose concentrations in which the rate of insulin secretion changes significantly. The expressions for the reaction rates

in Equation (1) are presented in

Table 1.

2.4. Model Parameterization

To parameterize the model, we used two sets of experimental data: one for healthy individuals and one for patients with type 2 diabetes. The experimental data included the dynamics of plasma metabolites after a single meal, as well as observations that the content of triglycerides in adipocytes did not change over a long period of time (1 month) in both healthy individuals [

26] and patients with type 2 diabetes [

16] (see Materials and Methods). The initial conditions were the concentrations of metabolites measured after an overnight fast [

16,

22] (

Table 2), assuming that by this point the concentrations of all metabolites had reached their steady-state concentrations. In cases where the concentrations were unknown for patients with type 2 diabetes (

G3P,

G3Pp,

FA,

TG), their values were set to be the same as for healthy individuals.

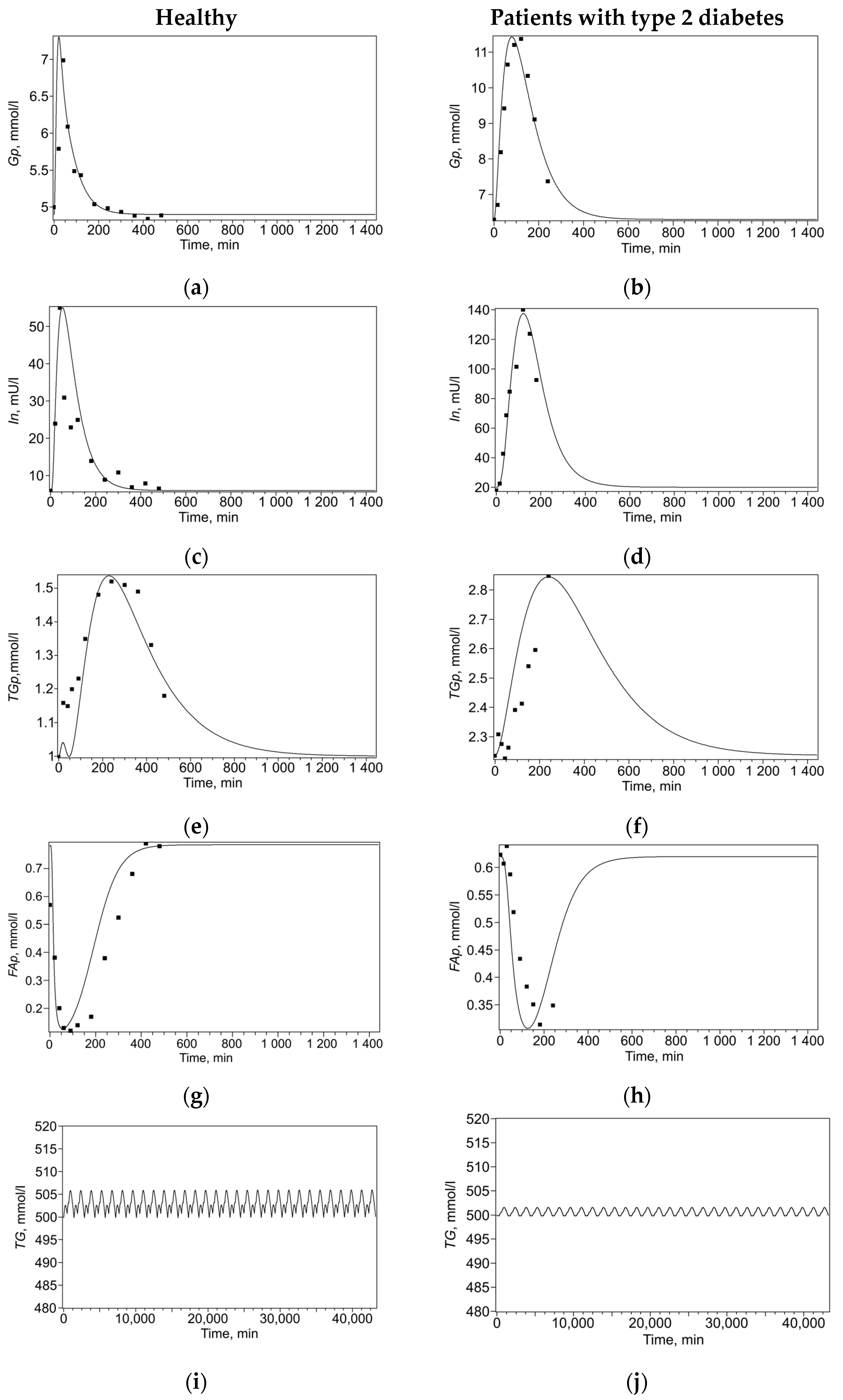

The model solutions and experimental data points are presented in

Figure 2. For each set of experimental data, a set of model parameters (

Table 3) was found that minimized the discrepancy between the model solutions and experimental data points. To reduce ambiguity in parameter identification, fitting was performed simultaneously across the entire set of experimental curves, including both changes in plasma metabolites after a single meal and maintaining a constant triglyceride level over a month, separately for healthy subjects (

Figure 2a,c,e,i) and for patients with type 2 diabetes (

Figure 2b,d,f,j). This multi-curve approach constrains parameter space, as a single parameter set must reproduce multiple distinct physiological responses, thereby reducing identifiability uncertainty.

It should be noted that the constants of activation and inhibition of insulin reactions (

,

,

,

) in patients with type 2 diabetes were significantly lower than in healthy individuals, which can be correlated with the state of insulin resistance characteristic of this disease. However, we observed that the parameter governing maximal insulin secretion (

) was higher for patients with type 2 diabetes than for healthy individuals, a finding consistent with experimental data showing higher insulin peaks in this population [

16]. This result may appear counterintuitive, as type 2 diabetes is typically associated with a blunted insulin peak amplitude [

27]. However, the patients in our dataset had concomitant obesity (mean BMI = 31) [

16], and in obese individuals, including those with early-stage type 2 diabetes, compensatory hypersecretion can lead to elevated fasting and postprandial insulin levels, overriding the typical attenuation of the insulin response [

28,

29,

30].

Thus, for each of the selected sets of parameters (for healthy individuals and patients with type 2 diabetes), the model adequately describes the dynamics of blood plasma metabolites after a single meal (

Figure 2a–h), as well as the content of triglycerides in adipocytes over the course of a month with three meals a day (

Figure 2i,j).

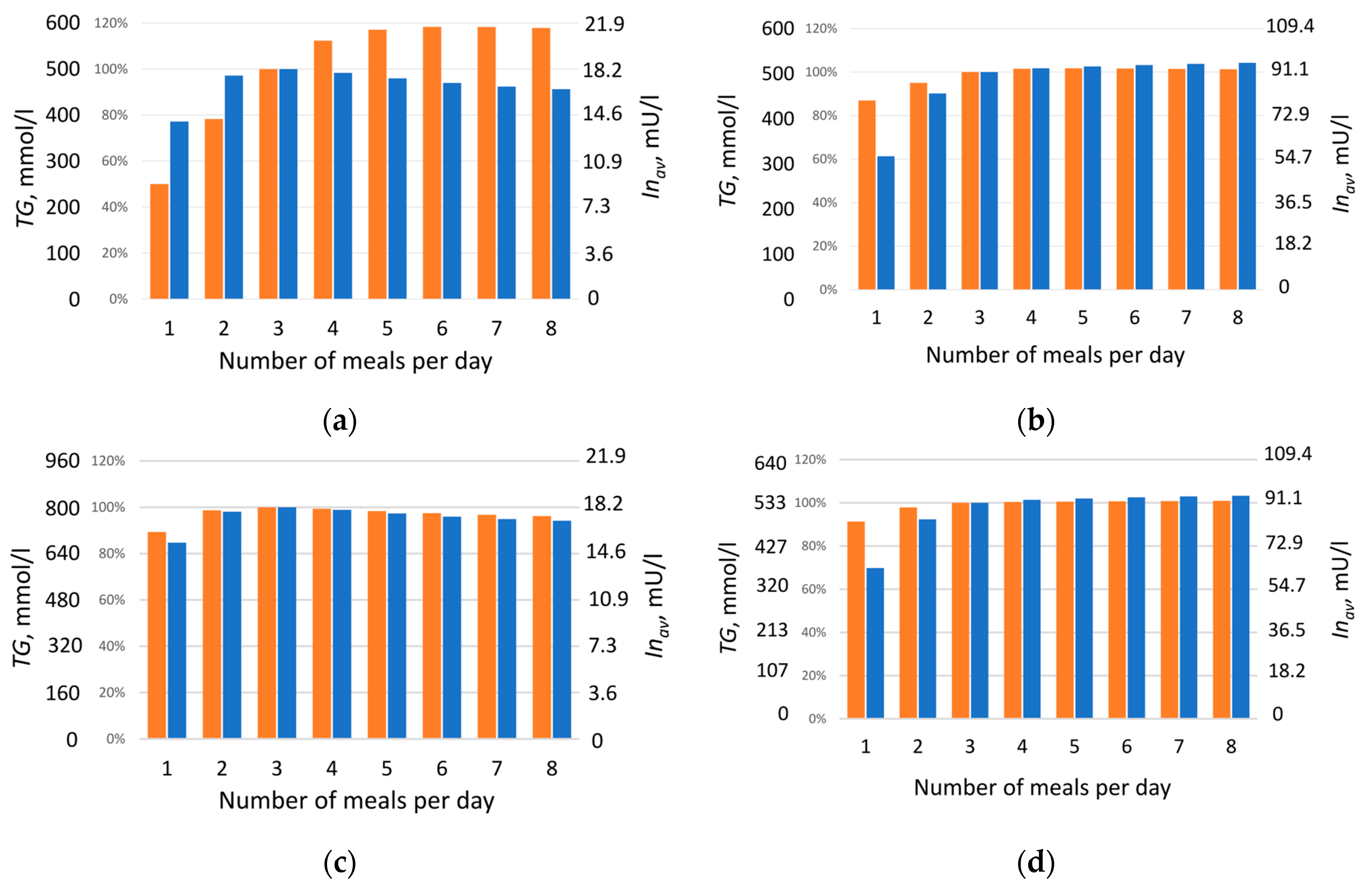

2.5. Triglyceride Accumulation Depending on the Number of Meals

At the next stage, numerical experiments were conducted based on the calibrated parameters to model triglyceride accumulation in the lipid droplet of adipocyte depending on meal frequency under isocaloric conditions. In the model, food intake was represented as periodic input of lipids (

F) and carbohydrates (

C) into the system. Feeding regimens were considered in which the number of daily meals varied from one to eight over 12 h (720 min), with a 12 h (720 min) overnight fasting period. To compare modeling results for healthy individuals and those with type 2 diabetes, a diet was designed such that daily caloric intake was identical for all meal frequencies and for both groups, comprising 879 kcal (117 mmol) of lipids and 1168 kcal (1583 mmol) of carbohydrates. The total amount of lipids (

F) and carbohydrates (

C)—2047 kcal—was divided equally among the number of daily meals. Three-meal feeding was selected as the baseline, under which triglyceride content remained unchanged over the month (see

Section 4). The effect of meal frequency on triglyceride (

TG) accumulation in adipocytes was investigated, evaluating changes in their concentration at different number of daily meals, from one to eight (

Figure 3, orange bars). The dynamics of all model metabolites for healthy individuals and patients with type 2 diabetes are presented in

Figure S1 (Supplementary Materials), using two-meal and five-meal regimens as examples.

Figure 3 and

Figure S1 show that, depending on meal frequency, triglyceride (

TG) content in adipocytes may increase, for example, under five-meal feeding (red curves in

Figure S1w–z and corresponding bars in

Figure 3a,b), or decrease under two-meal feeding (black curves in

Figure S1w–z and corresponding bars in

Figure 3a,b). This effect was weaker in patients with type 2 diabetes (

Figure 3b) than in healthy individuals (

Figure 3a).

Given that triglyceride accumulation, and consequently fat mass gain, is often associated with insulin level [

29,

31], triglyceride content was compared with the daily average insulin concentration, calculated using Formula (8) (see

Section 4), for each feeding regimen (

Figure 3, blue bars). As expected, patients with type 2 diabetes exhibited a several-fold higher daily average insulin level (3–5 times) than healthy individuals (

Figure 3), consistent with the literature reports of hyperinsulinemia in this condition [

30,

32].

With increasing meal frequency, triglyceride content in adipocytes rises, and the effect is most pronounced in healthy individuals (

Figure 3a, orange bars). In patients with type 2 diabetes, this dependence is less apparent (

Figure 3b, orange bars), which may be explained by the presence of insulin resistance, typical for this condition. The obtained result demonstrates a clear effect: at identical daily caloric intake, constant lipid-to-carbohydrate ratio, and equal sensitivity of insulin-dependent reactions, the triglyceride content synthesized over one month (and thus fat mass) varies significantly depending on meal frequency. This indicates that fat mass accumulation is determined not only by total caloric intake but also by the frequency of nutrient delivery. Unexpectedly, a nonlinear relationship was observed between average daily insulin level and triglyceride accumulation as a function of daily meal frequency (

Figure 3a). It was assumed that a reduced insulin level with more frequent meals should be accompanied by decreased triglyceride content, which generally aligns with modeling results obtained for diabetic patients (

Figure 3d). However, in healthy individuals, the outcome was opposite: starting from four meals per day, insulin level decrease with increasing meal frequency, while triglyceride content rise (

Figure 3a).

The observed lack of correlation between insulin level and triglyceride accumulation led to the hypothesis that differences in triglyceride accumulation relative to changes in daily average insulin level are determined specifically by the dynamics of the insulin response, rather than by the value of its daily average level. To test this hypothesis, an additional modeling experiment was conducted with a fixed insulin level corresponding to the daily average level under the respective feeding regimen. For this purpose, insulin dynamics was excluded from the model (1): d

In/d

t = 0, and the daily average insulin amount was set according to the values shown in

Figure 3a,b. Subsequently, at constant insulin level

, concentrations of accumulated triglycerides (

TG) were obtained for different numbers of daily meals (

Figure 3c,d) in the absence of insulin dynamics. The experiment showed that in the absence of insulin fluctuations, an almost linear relationship is established between the amount of triglycerides accumulated by adipocytes over one month and insulin level (

Figure 3c,d). This was true both for healthy individuals (

Figure 3c) and for patients with type 2 diabetes (

Figure 3d): a decrease in insulin level was accompanied by a reduction in triglyceride content, consistent with established views on insulin’s effect on lipogenesis. Therefore, our model suggests that it is the dynamics of the insulin response, not its daily average value, that accounts for the observed lack of correlation between insulin level and fat accumulation under varying meal frequencies of an isocaloric diet.

Since many reactions involved in triglyceride formation, including glucose transport into adipocytes, lipogenesis, and lipolysis, were insulin-dependent, it was important to determine the extent to which insulin affects these reactions, whether its influence was uniform or preferential toward certain reactions. To identify which lipid metabolism reactions were most sensitive to the dynamics of the insulin signal, we examined changes in metabolic fluxes upon varying the number of daily meals. The daily average reaction rates

, calculated according to Formula (7) (see

Section 4), are presented for healthy individuals in

Table 4 and for patients with type 2 diabetes in

Table 5. In addition to mean values, the tables indicate the ranges of variation for each rate, normalized to the maximum value of the corresponding rate. Since the considering system reached a steady state by the end of the day, starting from the first meal, the average values of

,

,

,

,

are equal to the average values of

,

,

,

,

respectively; therefore, only the values for the last group of reactions are given in the tables.

The data presented in

Table 4 and

Table 5 show that the greatest variation in daily average reaction rates upon varying meal frequency is observed for two key processes: triglyceride lipolysis in adipocytes

and insulin secretion

, both in healthy individuals and in patients with diabetes. It should be noted that the rates of reactions responsible for triglyceride formation change very little with alterations in feeding regimen, in contrast to the pronounced variability in lipolysis rate, despite the general regulatory role of insulin in all these processes. Triglyceride content in adipocytes is determined by the balance between their synthesis and degradation. Since the daily amount of synthesized triglycerides was virtually independent of meal frequency (average rate

remained nearly constant;

Table 4 and

Table 5), the increase in their accumulation under more frequent feeding can be explained by a reduction in lipolysis rate

, i.e., by a decrease in the amount of degraded triglycerides. Importantly, regardless of the chosen feeding regimen, mass balance was preserved in the calculation of metabolic fluxes: the amount of consumed substance matched the total amount excreted and accumulated (balance was determined based on molar carbon content). Thus, the observed dependence of triglyceride accumulation on meal frequency under identical daily caloric intake is not due to changes in synthesis rate, but rather to redistribution between accumulation and degradation processes, primarily through suppression of lipolysis. Analysis showed that the dynamic profile of insulin plays a key role in this effect. Its shape is determined by several parameters: amplitude and duration (width) of insulin peaks, their number, and the degree of overlap, which increases with higher meal frequency, since the next insulin response begins before the previous one has fully declined.

2.6. Study of the Effect of Dynamic Characteristics of the Insulin Response on Triglyceride Accumulation Using a Reduced Model

The kinetic curves of metabolites (

Figure S1, Supplementary Materials) revealed that both the amplitude and width of insulin peaks varied substantially depending on meal frequency. To investigate how exactly the characteristics of the insulin profile affect triglyceride accumulation, we constructed a reduced model based on the finding of the key role of lipolysis.

Analysis of daily average metabolic reaction rates showed that upon varying meal frequency, only two key rates, triglyceride lipolysis

and insulin secretion, changed significantly, while the rates of all other reactions remained virtually unchanged (

Table 4 and

Table 5). Based on this, the original adipocyte metabolism model was reduced to a minimal lipolysis model. In the reduced version, only two processes were included: triglyceride synthesis at a constant rate

(corresponding to

in the original model) and their lipolysis at rate

(corresponding to

in the original model), dependent on the dynamic insulin profile (

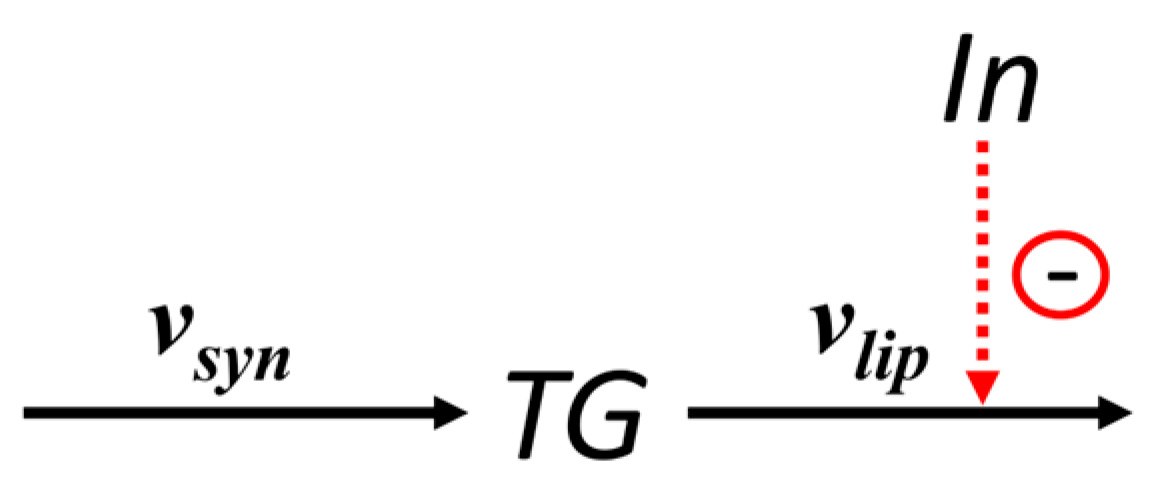

Figure 4).

This model reduction allowed focusing on the key mechanism regulating fat accumulation, suppression of lipolysis, without losing essential dynamic properties of the system. The equation describing changes in triglyceride concentration

TG in adipocytes, according to the scheme in

Figure 4, is:

The general form of the dependence of the lipolysis rate on insulin concentration was set identically to that in the original model: , where is the lipolysis rate in the absence of inhibition, and is the inhibition constant for lipolysis.

In the original model, insulin dynamics depended nonlinearly on glucose concentration; therefore, when meal frequency was altered, insulin peak parameters—their amplitude, duration, and degree of overlap—changed simultaneously and interdependently. This precluded separate assessment of the contribution of each factor to lipolysis suppression and, consequently, to triglyceride accumulation. To overcome this limitation, in the reduced lipolysis model, the insulin response to food intake was defined by an analytical function (3), independent of glucose dynamics:

This function closely reproduces the shape of the insulin response in the original model and asymmetric profile observed in experimental data—a rapid initial rise followed by a slower decay. Importantly, this function allowed independent variation in the amplitude () and peak width (via parameter ) of the insulin response, as well as setting the basal insulin level (). The peak width at — was chosen to characterize peak width; for the equation of form (3), was calculated using the Lambert W-function as . This approach enables control over individual dynamic characteristics of the insulin profile, which made it possible to study their effect on lipolysis suppression and triglyceride accumulation in adipocytes.

Instead of periodic food intake (as in the original model), the reduced model considered the corresponding sequence of insulin concentration peaks, defined by a formula of the form (3):

where

—are the onset times of the insulin response,

for

,

for

,

is the peak amplitude corresponding to the given number of insulin responses. Taking Formula (4) into account, the daily average insulin level can be calculated as

where

= 1440 min (1 day).

If there is no peak overlap, the average insulin level can be estimated as

where

—number of peaks.

The parameters of the reduced model (

,

,

) and insulin response parameters (

,

, and

) were not directly inherited from the full model, as the reduction process eliminates all non-essential reactions. Instead, they were calibrated such that the solutions of the reduced model, specifically the dynamics of insulin concentration (

Figure 5a) and the final triglyceride content after one month (

Figure 5b), closely matched those of the original model across different feeding regimens.

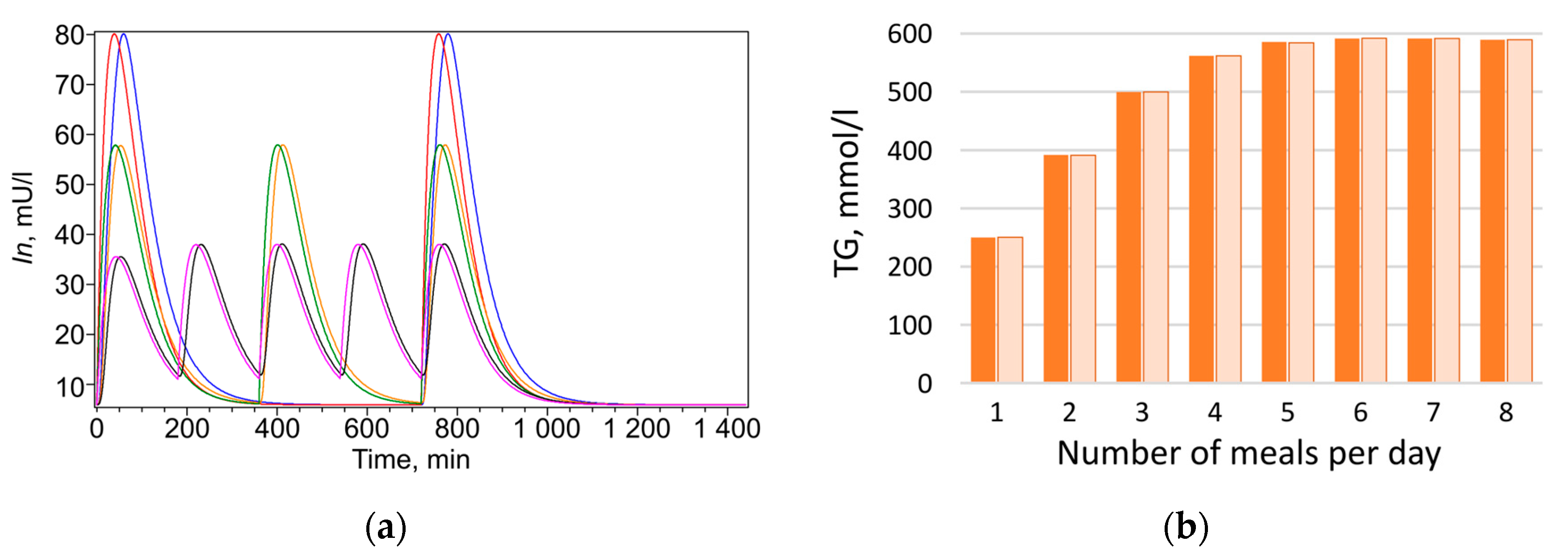

Figure 5.

Comparison of the calculation results of the original and reduced models. (

a) Insulin dynamics over 1 day with two, three, and five meals in the original model (blue, orange, and black curves, respectively) and in the reduced model (red, green, and purple curves, respectively); (

b) Adipocyte triglyceride content after 1 month in the original (orange bars) and reduced (light orange bars) models with different numbers of meals;

;

;

. The insulin response characteristics are presented in

Table 6.

Figure 5.

Comparison of the calculation results of the original and reduced models. (

a) Insulin dynamics over 1 day with two, three, and five meals in the original model (blue, orange, and black curves, respectively) and in the reduced model (red, green, and purple curves, respectively); (

b) Adipocyte triglyceride content after 1 month in the original (orange bars) and reduced (light orange bars) models with different numbers of meals;

;

;

. The insulin response characteristics are presented in

Table 6.

Table 6.

Characteristics of the insulin response in a reduced model.

Table 6.

Characteristics of the insulin response in a reduced model.

| (number of peaks) | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 |

| (peak amplitude, mU L–1) | 280.5 | 202 | 141 | 103.7 | 81 | 64.7 | 53.5 | 45.4 |

| (peak half-width, min) | 79.9 | 95.6 | 102.9 | 104.1 | 105.4 | 107.3 | 109.0 | 110.5 |

| (interval between peaks, min) | – | 720 | 360 | 240 | 180 | 144 | 120 | 103 |

Thus, solutions of the reduced model (2–6) under variations in parameters and adequately reproduce the behavior of the full model in response to changes in the insulin profile, enabling its use for analyzing the influence of individual dynamic parameters on triglyceride content in adipocytes.

To assess the individual contribution of amplitude (), width () of insulin peaks, their number (), and the intervals between them (partial peak overlap may occur with short intervals) to triglyceride accumulation in adipocytes, a series of numerical experiments was conducted using the reduced lipolysis model, analyzing triglyceride accumulation over one month.

To avoid peak overlap when varying amplitude and width under periodic insulin delivery, in subsequent numerical experiments the peak width was reduced ( min). The lipolysis rate constant () was adjusted so that, at the selected peak width, triglyceride content in adipocytes remained unchanged by the end of the month under thrice-daily insulin delivery, consistent with the behavior of the original model. For convenience of comparison, triglyceride values obtained in different numerical experiments were normalized to a chosen reference value defined as the triglyceride content at the end of the month under thrice-daily insulin delivery.

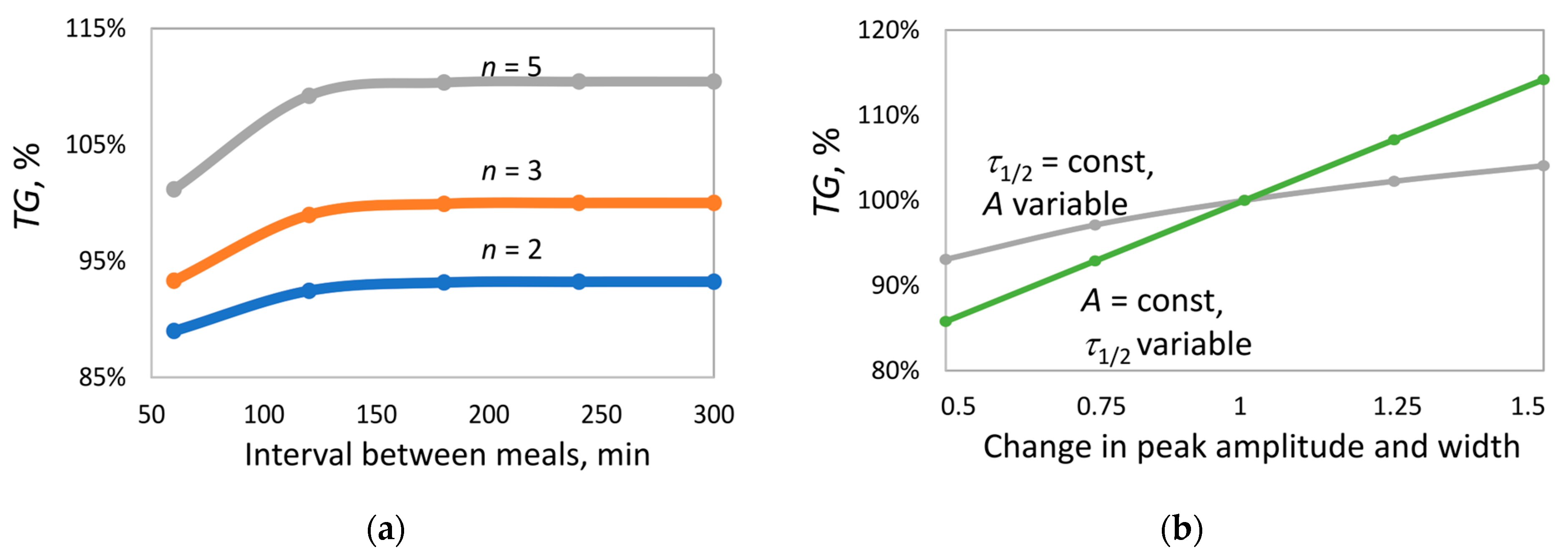

In the first series of experiments, the effect of the interval between insulin peaks (

Figure 6a) was investigated under two-, three-, and five-fold insulin delivery. The interval was varied from 60 to 300 min. At long intervals (180–300 min), when peak overlap is nearly absent, triglyceride accumulation by the end of the month increases with increasing number of peaks

. In contrast, at short intervals (60 min), strong peak overlap occurs, leading to a reduction in triglyceride content by 2%, 7%, and 10% for

= 2, 3, and 5, respectively. Nevertheless, even under maximum overlap, triglyceride accumulation at

n = 5 remains higher than at

= 2. Importantly, in all cases, with the selected parameters, the average insulin level was identical, excluding the influence of this parameter on the outcome.

In the next series of experiments, under thrice-daily insulin delivery (interval 300 min, no peak overlap;

Figure 6b), the effects of amplitude and peak width on triglyceride accumulation were compared. According to Formula (6), altering either parameter results in a proportional change in the average insulin level (

). To isolate the effect of each parameter, they were varied independently, and both were scaled by the same factor, so that

increased to the same extent in both cases.

At fixed peak width, increasing amplitude led to ~11% increase in TG content. In contrast, at fixed amplitude, increasing peak width resulted in ~30% increase in TG content. This suggests that peak width exerts a significantly stronger influence on lipid balance than amplitude, despite identical changes in average insulin level.

3. Discussion

The aim of this study was to test the hypothesis that meal frequency, at constant daily caloric intake, may influence triglyceride accumulation in adipocytes. For this purpose, a mathematical model of carbohydrate–lipid metabolism was developed, capturing the dynamics of key metabolites in blood plasma and adipocytes, while allowing variation in meal number, frequency, and macronutrient composition. The model accounts for the two-stage process of digestion: nutrient entry into the gastrointestinal tract and subsequent transport of glucose and fatty acids into blood plasma. This enabled an adequate description of glucose, insulin, and fatty acid dynamics following a single meal. Although the accuracy of describing multiple meals (compared to single meals) is somewhat reduced due to simplifications in nutrient absorption kinetics, the model is sufficient for analyzing qualitative patterns and identifying potential mechanisms by which meal regimen affects lipid metabolism. Since the primary focus was on processes within the adipocyte, the model includes key insulin-regulated reactions of triglyceride synthesis and degradation, with insulin serving as the primary hormonal regulator of lipid metabolism in adipose tissue [

12]. Other regulatory factors (leptin, glucagon, etc.) are not included in the model, representing a simplification that allows isolation of insulin’s contribution. The model is limited to blood plasma and adipocytes, justified by its focus on intracellular fat storage processes.

During model parameterization for patients with type 2 diabetes, reaction rate constants characterizing insulin’s effects were found to be smaller compared to healthy individuals, reflecting the clinical picture of insulin resistance and enabling adequate reproduction of metabolic profiles in these patients.

The key modeling result is that, at constant daily caloric intake and macronutrient ratio, meal frequency substantially affects triglyceride content in adipocytes. With infrequent feeding (1–2 meals per day), fat mass decreases, whereas with frequent feeding (5–8 meals per day), it increases. This effect is most pronounced in healthy individuals and weaker in patients with type 2 diabetes.

At first glance, fat accumulation should correlate with average insulin level, since insulin stimulates triglyceride synthesis and suppresses lipolysis. However, analysis revealed a nonlinear relationship between daily average insulin concentration and triglyceride accumulation in healthy individuals: as meal frequency increases, insulin level initially rises and then declines, while triglyceride content monotonically increases. In contrast, patients with type 2 diabetes exhibit a more direct relationship, consistent with their chronic hyperinsulinemia and high basal stimulation of lipogenesis.

This discrepancy led to the hypothesis that it is not the average insulin level but its dynamic profile, amplitude, duration, and degree of peak overlap, that plays a decisive role in regulating lipid metabolism. This was confirmed by simulations under constant (steady-state) insulin level: in this case, the relationship between insulin and triglyceride accumulation became linear, consistent with classical views of its action.

Further analysis showed that the rate of triglyceride synthesis (reaction

) remains virtually unchanged with varying meal frequency, whereas the rate of lipolysis (

) significantly decreases with more frequent feeding. Thus, our model indicates fat accumulation is driven not by enhanced lipogenesis but by suppressed lipolysis, and this reaction is most sensitive to changes in the insulin profile. This observation is consistent with the literature data. Insulin suppresses lipolysis by inhibiting key enzymes, such as adipose triglyceride lipase and hormone-sensitive lipase [

33]. Although insulin also stimulates glucose transport into adipocytes via GLUT4 [

34], experiments with GLUT4-deficient mice show that this does not lead to significant changes in fat accumulation [

35], indicating higher regulatory sensitivity of lipolysis compared to glucose transport.

To investigate the contribution of individual dynamic characteristics of the insulin response, a reduced model was developed, in which the insulin profile was defined by an analytical function. On one hand, the reduced model qualitatively yielded the same results as the full model. On the other hand, it allowed independent variation in intervals between meals, amplitude, and width of the insulin response peak.

Analysis of results obtained with the reduced model showed that both increasing the amplitude and increasing the width of the insulin peak enhance lipolysis suppression and promote triglyceride accumulation. However, increasing peak width exerts a stronger effect than an equivalent increase in amplitude. In other words, the duration of insulin action (peak width) carries greater weight in suppressing lipolysis than its peak value. The observed model effects find physiological parallels in known metabolic responses. It is known that lowering the blood insulin level correlates with a reduction in fat stores [

36]. Decreasing the peak amplitude corresponds to reduced food intake, for example, under moderate caloric restriction. Decreasing the peak width may be induced by physical activity after meals, for instance, walking, which accelerates metabolism and shortens the duration of the insulin response. According to model results, it can be expected that physical activity would produce a greater effect than caloric restriction at the same average insulin level.

Such a difference in the impact of amplitude versus peak width can be explained by the nonlinear nature of inhibition: since lipolysis suppression in the considered models follows a hyperbolic function, even a modest increase in insulin exposure duration can lead to a substantial reduction in triglyceride breakdown rate, particularly in the saturation region of the function, where the reaction becomes less sensitive to increasing concentration but highly dependent on exposure duration. The hyperbolic dependence of lipolysis on insulin concentration is consistent with known experimental data [

37,

38]. Modeling results show that it is precisely this form of inhibitory function that gives rise to complex dynamic effects that cannot be predicted based on the average hormone level.

Thus, the obtained results indicate that the meal regimen, even under isocaloric conditions, may significantly affect the lipid metabolism through the formation of a specific insulin profile. Frequent feeding, despite lower insulin peaks compared to less frequent meals, leads to more sustained suppression of lipolysis and consequently greater triglyceride accumulation, particularly when significant peak overlap is absent. This effect is most pronounced in healthy individuals and attenuated under insulin resistance.

While some experimental studies have reported that reduced meal frequency is associated with lower body weight gain or improved body composition [

39], the overall evidence remains inconsistent. Meta-analyses and reviews highlight substantial heterogeneity in study designs, participant characteristics, and dietary interventions, making it difficult to draw firm conclusions about the effect of meal frequency on fat accumulation [

8,

40]. This inconsistency likely arises from the multitude of confounding factors, including total caloric intake, macronutrient composition, physical activity, and individual metabolic variability, that influence energy balance in real-world settings. Our model, by contrast, isolates the specific role of insulin dynamics under strictly controlled isocaloric conditions. By focusing on the adipocyte and eliminating other physiological variables, we were able to demonstrate a clear mechanistic link: fewer meals lead to less triglyceride accumulation primarily because they result in shorter, less overlapping insulin peaks, thereby allowing greater lipolysis. This finding provides a potential explanation for why, in some clinical and observational studies, infrequent eating is associated with reduced fat gain—not necessarily due to total calories, but due to the temporal pattern of nutrient delivery and its downstream hormonal consequences.

It should be noted that the implications of these findings for in vivo physiology should be interpreted with great caution. The model intentionally excludes explicit representations of the dynamics of the liver and skeletal muscle metabolism; their contributions are reduced to effective fluxes that reflect overall systemic effects rather than organ-specific dynamics. This simplification was necessary to isolate the primary mechanism under study: how insulin dynamics regulate lipid accumulation in adipocytes. This is a fundamental limitation of the model. In complex biological systems, separating the contributions of individual components is inherently challenging. The dynamic, interconnected reactions occurring in the liver and muscle are not reflected in our current model. Nevertheless, the model successfully reproduces the experimental dynamics of key carbohydrate-lipid metabolites in blood plasma for both healthy individuals and patients with type 2 diabetes after a single meal (

Figure 2).

Crucially, the conclusions drawn from the model at this stage of the study apply strictly to processes occurring within the adipocyte. We identified a non-intuitive, dominant role for adipocyte lipolysis: its nonlinear suppression by insulin renders fat accumulation more sensitive to the temporal profile of insulin than to its average daily concentration. To evaluate the impact at the whole-body level, the contribution of dynamic metabolic fluxes from the liver and skeletal muscle must be incorporated. The extent of their influence on the adipocyte-specific mechanism identified here may be substantial or relatively minor; however, this remains unknown without an integrated multicomponent model. Nevertheless, by first isolating and quantifying the dominant mechanism in adipocytes (suppression of lipolysis), we have laid an important foundation for a further, more targeted approach to expand the model to include the liver and muscle compartments and identify their contribution to the dynamics of triglyceride accumulation.

The conclusions of this work emphasize the importance of a dynamic approach to analyzing hormonal regulation of metabolism and may be relevant for developing personalized dietary recommendations that consider not only the composition and caloric content of the diet but also the temporal pattern of meals.