Vitamin D and Vitamin D Analogues in Hemodialysis Patients: A Review of the Literature

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Vitamin D Forms and Their Use in Hemodialysis

2.2. Pleiotropic Actions of Vitamin D

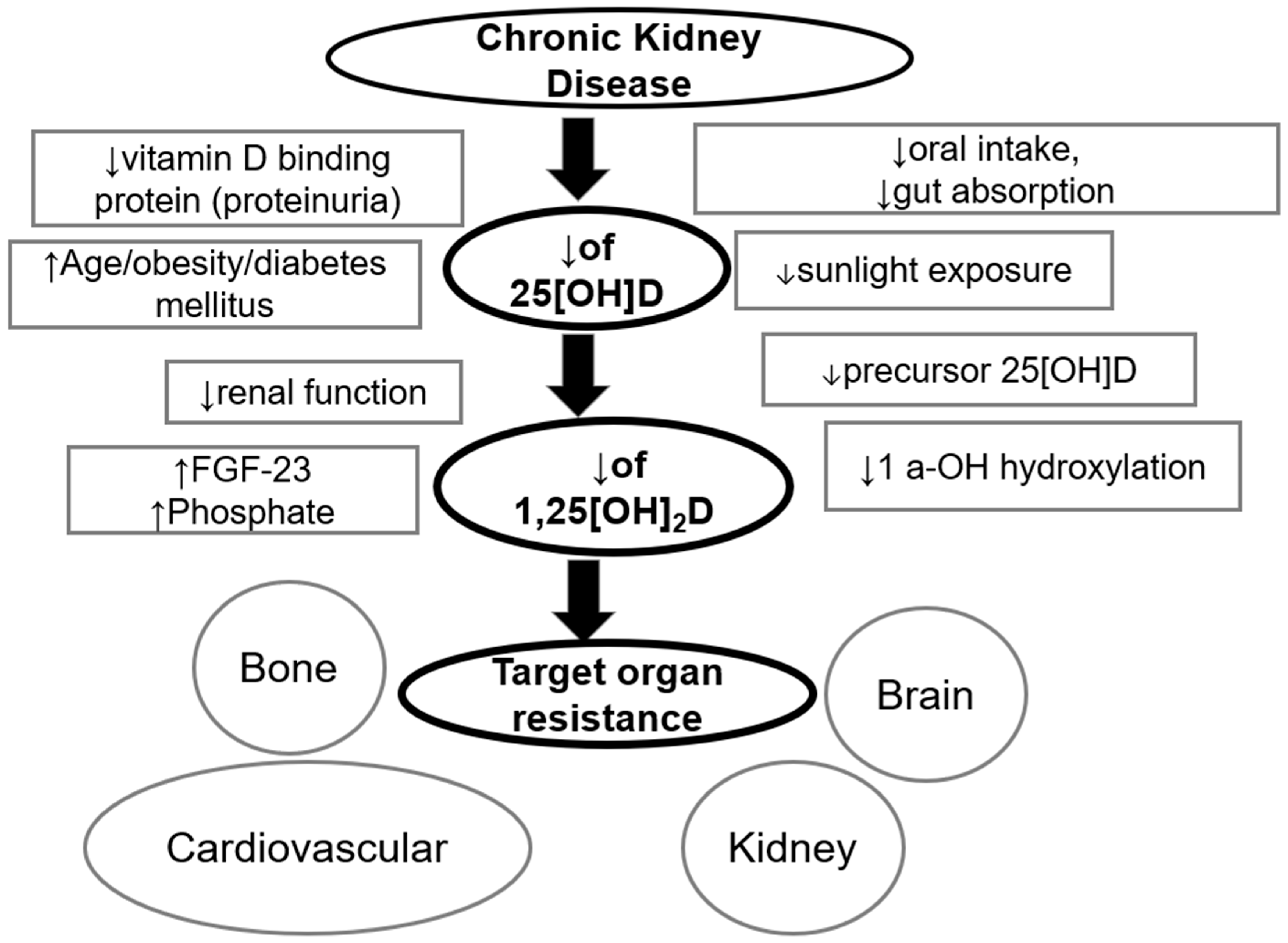

2.3. Reasons for Vitamin D Deficiency/Insufficiency in Dialysis Patients

3. Discussion

3.1. Association Between Vitamin D Deficiency and Adverse Outcomes in Dialysis Patients

3.2. Kidney Disease Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) Guidelines and Vitamin D

3.3. Native Vitamin D and Dialysis Patients

4. Materials and Methods

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Stevens, P.E.; Ahmed, S.B.; Carrero, J.J.; Foster, B.; Francis, A.; Hall, R.K.; Herrington, W.G.; Hill, G.; Inker, L.A.; Kazancıoğlu, R.; et al. KDIGO 2024 Clinical Practice Guideline for the Evaluation and Management of Chronic Kidney Disease. Kidney Int. 2024, 105, S117–S314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saponaro, F.; Saba, A.; Zucchi, R. An Update on Vitamin D Metabolism. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 6573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zappulo, F.; Cappuccilli, M.; Cingolani, A.; Scrivo, A.; Chiocchini, A.L.C.; Nunzio, M.D.; Donadei, C.; Napoli, M.; Tondolo, F.; Cianciolo, G.; et al. Vitamin D and the Kidney: Two Players, One Console. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 9135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holick, M.F. Vitamin D status: Measurement, interpretation, and clinical application. Ann. Epidemiol. 2009, 19, 73–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wheeler, W.D.C.; Winkelmayer, W.C. KDIGO 2017 Clinical Practice Guideline Update for the Diagnosis, Evaluation, Prevention, and Treatment of Chronic Kidney Disease-Mineral and Bone Disorder (CKD-MBD). Kidney Int. Suppl. 2017, 7, 1–59. [Google Scholar]

- Martin, K.J.; Gonzalez, E.A. Vitamin D analogues for the management of secondary hyperparathyroidism. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 2001, 38 (Suppl. S5), S34–S40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, G. The discovery and synthesis of the nutritional factor vitamin D. Int. J. Paleopathol. 2018, 23, 96–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, X.; Liu, W.; Yan, Y.; Liu, H.; Huang, Q.; Xiao, Y.; Gong, Z.; Du, J. Vitamin D protects against diabetic nephropathy: Evidence-based effectiveness and mechanism. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2019, 845, 91–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gupta, S.; Goyal, P.; Feinn, R.S.; Mattana, J. Role of Vitamin D and Its Analogues in Diabetic Nephropathy: A Meta-analysis. Am. J. Med. Sci. 2019, 357, 223–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.C.; Zheng, C.M.; Lu, C.L.; Lin, Y.F.; Shyu, J.F.; Wu, C.C.; Lu, K.C. Vitamin D and immune function in chronic kidney disease. Clin. Chim. Acta 2015, 450, 135–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsujimoto, Y.; Tahara, H.; Shoji, T.; Emoto, M.; Koyama, H.; Ishimura, E.; Tabata, T.; Nishizawa, Y.; Inaba, M. Active vitamin D and acute respiratory infections in dialysis patients. Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2011, 6, 1361–1367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tangwonglert, T.; Davenport, A. The effect of prescribing vitamin D analogues and serum vitamin D status on both contracting COVID-19 and clinical outcomes in kidney dialysis patients’. Nephrology 2022, 27, 815–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalinkeviciene, E.; Gradauskiene, B.; Sakalauskaite, S.; Petruliene, K.; Vaiciuniene, R.; Skarupskiene, I.; Bastyte, D.; Sauseriene, J.; Valius, L.; Bumblyte, I.A.; et al. Immune Response after Anti-SARS-CoV-2 mRNA Vaccination in Relation to Cellular Immunity, Vitamin D and Comorbidities in Hemodialysis Patients. Microorganisms 2024, 12, 861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tylicki, P.; Polewska, K.; Och, A.; Susmarska, A.; Puchalska-Reglinska, E.; Parczewska, A.; Biedunkiewicz, B.; Szabat, K.; Renke, M.; Tylicki, L.; et al. Angiotensin Converting Enzyme Inhibitors May Increase While Active Vitamin D May Decrease the Risk of Severe Pneumonia in SARS-CoV-2 Infected Patients with Chronic Kidney Disease on Maintenance Hemodialysis. Viruses 2022, 14, 451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foley, R.N.; Murray, A.M.; Li, S.; Herzog, C.A.; McBean, A.M.; Eggers, P.W.; Collins, A.J. Chronic kidney disease and the risk for cardiovascular disease, renal replacement, and death in the United States Medicare population, 1998 to 1999. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2005, 16, 489–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, D.; Jha, V. Vitamin D and Cardiovascular Complications of CKD: What’s Next? Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2019, 14, 932–934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Mheid, I.; Quyyumi, A.A. Vitamin D and Cardiovascular Disease: Controversy Unresolved. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2017, 70, 89–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bivona, G.; Gambino, C.M.; Iacolino, G.; Ciaccio, M. Vitamin D and the nervous system. Neurol. Res. 2019, 41, 827–835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garcia-Serna, A.M.; Morales, E. Neurodevelopmental effects of prenatal vitamin D in humans: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Mol. Psychiatry 2020, 25, 2468–2481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jacob, A.I.; Sallman, A.; Santiz, Z.; Hollis, B.W. Defective photoproduction of cholecalciferol in normal and uremic humans. J. Nutr. 1984, 114, 1313–1319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bentata, Y. Benefit-risk balance of native vitamin D supplementation in chronic hemodialysis: What can we learn from the major clinical trials and international guidelines? Ren. Fail. 2019, 41, 607–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takemoto, F.; Shinki, T.; Yokoyama, K.; Inokami, T.; Hara, S.; Yamada, A.; Kurokawa, K.; Uchida, S. Gene expression of vitamin D hydroxylase and megalin in the remnant kidney of nephrectomized rats. Kidney Int. 2003, 64, 414–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Echida, Y.; Mochizuki, T.; Uchida, K.; Tsuchiya, K.; Nitta, K. Risk factors for vitamin D deficiency in patients with chronic kidney disease. Intern. Med. 2012, 51, 845–850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krajisnik, T.; Bjorklund, P.; Marsell, R.; Ljunggren, O.; Akerstrom, G.; Jonsson, K.B.; Westin, G.; Larsson, T.E. Fibroblast growth factor-23 regulates parathyroid hormone and 1α-hydroxylase expression in cultured bovine parathyroid cells. J. Endocrinol. 2007, 195, 125–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perwad, F.; Azam, N.; Zhang, M.Y.; Yamashita, T.; Tenenhouse, H.S.; Portale, A.A. Dietary and serum phosphorus regulate fibroblast growth factor 23 expression and 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D metabolism in mice. Endocrinology 2005, 146, 5358–5364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Michaud, J.; Naud, J.; Ouimet, D.; Demers, C.; Petit, J.L.; Leblond, F.A.; Bonnardeaux, A.; Gascon-Barre, M.; Pichette, V. Reduced hepatic synthesis of calcidiol in uremia. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2010, 21, 1488–1497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsiaras, W.G.; Weinstock, M.A. Factors influencing vitamin D status. Acta Derm. Venereol. 2011, 91, 115–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ziouani, L.; Gruson, D.; Saidani, M.; Koceir, E.A. Vitamin D, anemia, and fibroblast growth factor 23: Ethnic disparities in Algerian chronic kidney disease patients. Nephrol. Ther. 2025, 21, 161–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hryciuk, M.; Heleniak, Z.; Malgorzewicz, S.; Kowalski, K.; Antosiewicz, J.; Koelmer, A.; Zmijewski, M.; Debska-Slizien, A. Assessment of Vitamin D Metabolism Disorders in Hemodialysis Patients. Nutrients 2025, 17, 774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) CKD-MBD Work Group. KDIGO clinical practice guideline for the diagnosis, evaluation, prevention, and treatment of Chronic Kidney Disease-Mineral and Bone Disorder (CKD-MBD). Kidney Int. Suppl. 2009, 113, S1–S130. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, Z.; Lin, J.; Qian, Q. Role of Vitamin D in Cognitive Function in Chronic Kidney Disease. Nutrients 2016, 8, 291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bataille, S.; Landrier, J.F.; Astier, J.; Giaime, P.; Sampol, J.; Sichez, H.; Ollier, J.; Gugliotta, J.; Serveaux, M.; Cohen, J.; et al. The “Dose-Effect” Relationship Between 25-Hydroxyvitamin D and Muscle Strength in Hemodialysis Patients Favors a Normal Threshold of 30 ng/mL for Plasma 25-Hydroxyvitamin D. J. Ren. Nutr. 2016, 26, 45–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.H.; Kim, J.E.; Roh, Y.H.; Choi, H.R.; Rhee, Y.; Kang, D.R.; Lim, S.K. The combination of vitamin D deficiency and mild to moderate chronic kidney disease is associated with low bone mineral density and deteriorated femoral microarchitecture: Results from the KNHANES 2008-2011. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2014, 99, 3879–3888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boudville, N.; Inderjeeth, C.; Elder, G.J.; Glendenning, P. Association between 25-hydroxyvitamin D, somatic muscle weakness and falls risk in end-stage renal failure. Clin. Endocrinol. 2010, 73, 299–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mucsi, I.; Almasi, C.; Deak, G.; Marton, A.; Ambrus, C.; Berta, K.; Lakatos, P.; Szabo, A.; Horvath, C. Serum 25(OH)-vitamin D levels and bone metabolism in patients on maintenance hemodialysis. Clin. Nephrol. 2005, 64, 288–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milinkovic, N.; Majkic-Singh, N.T.; Mirkovic, D.D.; Beletic, A.D.; Pejanovic, S.D.; Vujanic, S.T. Relation between 25(OH)-vitamin D deficiency and markers of bone formation and resorption in haemodialysis patients. Clin. Lab. 2009, 55, 333–339. [Google Scholar]

- Barreto, D.V.; Barreto, F.C.; Liabeuf, S.; Temmar, M.; Boitte, F.; Choukroun, G.; Fournier, A.; Massy, Z.A. Vitamin D affects survival independently of vascular calcification in chronic kidney disease. Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2009, 4, 1128–1135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pecovnik-Balon, B.; Jakopin, E.; Bevc, S.; Knehtl, M.; Gorenjak, M. Vitamin D as a novel nontraditional risk factor for mortality in hemodialysis patients. Ther. Apher. Dial. 2009, 13, 268–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolf, M.; Shah, A.; Gutierrez, O.; Ankers, E.; Monroy, M.; Tamez, H.; Steele, D.; Chang, Y.; Camargo, C.A., Jr.; Tonelli, M.; et al. Vitamin D levels and early mortality among incident hemodialysis patients. Kidney Int. 2007, 72, 1004–1013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drechsler, C.; Pilz, S.; Obermayer-Pietsch, B.; Verduijn, M.; Tomaschitz, A.; Krane, V.; Espe, K.; Dekker, F.; Brandenburg, V.; Marz, W.; et al. Vitamin D deficiency is associated with sudden cardiac death, combined cardiovascular events, and mortality in haemodialysis patients. Eur. Heart J. 2010, 31, 2253–2261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ravani, P.; Malberti, F.; Tripepi, G.; Pecchini, P.; Cutrupi, S.; Pizzini, P.; Mallamaci, F.; Zoccali, C. Vitamin D levels and patient outcome in chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int. 2009, 75, 88–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, A.Y.; Lam, C.W.; Sanderson, J.E.; Wang, M.; Chan, I.H.; Lui, S.F.; Sea, M.M.; Woo, J. Serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D status and cardiovascular outcomes in chronic peritoneal dialysis patients: A 3-y prospective cohort study. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2008, 87, 1631–1638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fusaro, M.; Gallieni, M.; Rebora, P.; Rizzo, M.A.; Luise, M.C.; Riva, H.; Bertoli, S.; Conte, F.; Stella, A.; Ondei, P.; et al. Atrial fibrillation and low vitamin D levels are associated with severe vascular calcifications in hemodialysis patients. J. Nephrol. 2016, 29, 419–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmadi, F.; Damghani, S.; Lessan-Pezeshki, M.; Razeghi, E.; Maziar, S.; Mahdavi-Mazdeh, M. Association of low vitamin D levels with metabolic syndrome in hemodialysis patients. Hemodial. Int. 2016, 20, 261–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, G.L.; Pi, H.C.; Hao, L.; Li, D.D.; Wu, Y.G.; Dong, J. Vitamin D Status Is an Independent Risk Factor for Global Cognitive Impairment in Peritoneal Dialysis Patients. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0143782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahdavi, S.; Rosychuk, K.; Taskapan, H.; Tam, P.Y.; Sikaneta, T. Vitamin D and Muscle Function in a Diverse Hemodialysis Cohort. Can. J. Kidney Health Dis. 2025, 12, 20543581251365363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lai, S.; Coppola, B.; Dimko, M.; Galani, A.; Innico, G.; Frassetti, N.; Mariotti, A. Vitamin D deficiency, insulin resistance, and ventricular hypertrophy in the early stages of chronic kidney disease. Ren. Fail. 2014, 36, 58–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, J.; Roem, J.; Furth, S.L.; Warady, B.A.; Atkinson, M.A.; Flynn, J.T.; CKiD Study Investigators. Vitamin D and its associations with blood pressure in the Chronic Kidney Disease in Children (CKiD) cohort. Pediatr. Nephrol. 2024, 39, 3279–3288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yeung, W.G.; Toussaint, N.D.; Lioufas, N.; Hawley, C.M.; Pascoe, E.M.; Elder, G.J.; Valks, A.; Badve, S.V. Vitamin D status and intermediate vascular and bone outcomes in chronic kidney disease: A secondary post hoc analysis of IMPROVE-CKD. Intern. Med. J. 2024, 54, 1960–1969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.Y.; Weng, H.L.; Lai, Y.C.; Hung, K.C. Severe vitamin D deficiency and risk of mild cognitive impairment in patients with chronic kidney disease: A cohort study. Medicine 2025, 104, e43235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, I.W.; Wang, W.T.; Lai, Y.C.; Chang, Y.J.; Lin, Y.T.; Hung, K.C. Association between vitamin D deficiency and major depression in patients with chronic kidney disease: A cohort study. Front. Nutr. 2025, 12, 1540633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- You, Y.; Xu, C.; Hu, Y.; Liang, M.; Sun, Q. Associations of vitamin D levels and clinical parameters with COVID-19 infection, severity and mortality in hemodialysis patients: A cohort study. Hemodial. Int. 2025, 29, 63–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakashima, A.; Yamamoto, I.; Kobayashi, A.; Kimura, K.; Yaginuma, T.; Nishio, S.; Kato, K.; Kawai, R.; Horino, T.; Ohkido, I.; et al. Active vitamin D analog and SARS-CoV-2 IgG after BNT162b2 vaccination in patients with hemodialysis. Ther. Apher. Dial. 2024, 28, 599–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- London, G.M.; Guerin, A.P.; Verbeke, F.H.; Pannier, B.; Boutouyrie, P.; Marchais, S.J.; Metivier, F. Mineral metabolism and arterial functions in end-stage renal disease: Potential role of 25-hydroxyvitamin D deficiency. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2007, 18, 613–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jorgensen, H.S.; Vervloet, M.; Cavalier, E.; Bacchetta, J.; de Borst, M.H.; Bover, J.; Cozzolino, M.; Ferreira, A.C.; Hansen, D.; Herrmann, M.; et al. The role of nutritional vitamin D in chronic kidney disease-mineral and bone disorder in children and adults with chronic kidney disease, on dialysis, and after kidney transplantation—A European consensus statement. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 2025, 40, 797–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holden, R.M.; Norman, P.A.; Day, A.G.; Silver, S.A.; Clemens, K.K.; Iliescu, E. Vitamin D Status and Treatment in ESKD: Links to Improved CKD-MBD Laboratory Parameters in a Real-World Setting. Am. J. Nephrol. 2024, 55, 638–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bishop, C.W.; Ashfaq, A.; Choe, J.; Strugnell, S.A.; Johnson, L.L.; Norris, K.C.; Sprague, S.M. Extended-Release Calcifediol Normalized 1,25-Dihydroxyvitamin D and Prevented Progression of Secondary Hyperparathyroidism in Hemodialysis Patients in a Pilot Randomized Clinical Trial. Am. J. Nephrol. 2025, 4, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saab, G.; Young, D.O.; Gincherman, Y.; Giles, K.; Norwood, K.; Coyne, D.W. Prevalence of vitamin D deficiency and the safety and effectiveness of monthly ergocalciferol in hemodialysis patients. Nephron Clin. Pract. 2007, 105, c132–c138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Massart, A.; Debelle, F.D.; Racape, J.; Gervy, C.; Husson, C.; Dhaene, M.; Wissing, K.M.; Nortier, J.L. Biochemical parameters after cholecalciferol repletion in hemodialysis: Results from the VitaDial randomized trial. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 2014, 64, 696–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delanaye, P.; Weekers, L.; Warling, X.; Moonen, M.; Smelten, N.; Medart, L.; Krzesinski, J.M.; Cavalier, E. Cholecalciferol in haemodialysis patients: A randomized, double-blind, proof-of-concept and safety study. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 2013, 28, 1779–1786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zitt, E.; Sprenger-Mahr, H.; Mundle, M.; Lhotta, K. Efficacy and safety of body weight-adapted oral cholecalciferol substitution in dialysis patients with vitamin D deficiency. BMC Nephrol. 2015, 16, 128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashfaq, A.; Choe, J.; Strugnell, S.A.; Patel, N.; Sprague, S.M.; Norris, K.C.; Lerma, E.; Petkovich, P.M.; Bishop, C.W.; Ashfaq, A. Adjunctive Active Vitamin D Decreases Kidney Function during Treatment of Secondary Hyperparathyroidism with Extended-Release Calcifediol in Non-Dialysis Chronic Kidney Disease in a Randomized Trial. Am. J. Nephrol. 2025, 56, 490–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhan, I.; Dobens, D.; Tamez, H.; Deferio, J.J.; Li, Y.C.; Warren, H.S.; Ankers, E.; Wenger, J.; Tucker, J.K.; Trottier, C.; et al. Nutritional vitamin D supplementation in dialysis: A randomized trial. Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2015, 10, 611–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armas, L.A.; Andukuri, R.; Barger-Lux, J.; Heaney, R.P.; Lund, R. 25-Hydroxyvitamin D response to cholecalciferol supplementation in hemodialysis. Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2012, 7, 1428–1434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kooienga, L.; Fried, L.; Scragg, R.; Kendrick, J.; Smits, G.; Chonchol, M. The effect of combined calcium and vitamin D3 supplementation on serum intact parathyroid hormone in moderate CKD. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 2009, 53, 408–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moorthi, R.N.; Moe, S.M. CKD-mineral and bone disorder: Core curriculum 2011. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 2011, 58, 1022–1036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marckmann, P.; Agerskov, H.; Thineshkumar, S.; Bladbjerg, E.M.; Sidelmann, J.J.; Jespersen, J.; Nybo, M.; Rasmussen, L.M.; Hansen, D.; Scholze, A. Randomized controlled trial of cholecalciferol supplementation in chronic kidney disease patients with hypovitaminosis D. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 2012, 27, 3523–3531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wasse, H.; Huang, R.; Long, Q.; Singapuri, S.; Raggi, P.; Tangpricha, V. Efficacy and safety of a short course of very-high-dose cholecalciferol in hemodialysis. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2012, 95, 522–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pilkey, N.G.; Novosel, O.; Roy, A.; Wilson, T.E.; Sharma, J.; Khan, S.; Kapuria, S.; Adams, M.A.; Holden, R.M. Does Native Vitamin D Supplementation Have Pleiotropic Effects in Patients with End-Stage Kidney Disease? A Systematic Review of Randomized Trials. Nutrients 2023, 15, 3072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miskulin, D.C.; Majchrzak, K.; Tighiouart, H.; Muther, R.S.; Kapoian, T.; Johnson, D.S.; Weiner, D.E. Ergocalciferol Supplementation in Hemodialysis Patients with Vitamin D Deficiency: A Randomized Clinical Trial. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2016, 27, 1801–1810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hewitt, N.A.; O’Connor, A.A.; O’Shaughnessy, D.V.; Elder, G.J. Effects of cholecalciferol on functional, biochemical, vascular, and quality of life outcomes in hemodialysis patients. Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2013, 8, 1143–1149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alshahawey, M.; El Borolossy, R.; El Wakeel, L.; Elsaid, T.; Sabri, N.A. The impact of cholecalciferol on markers of vascular calcification in hemodialysis patients: A randomized placebo controlled study. Nutr. Metab. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2021, 31, 626–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matias, P.J.; Jorge, C.; Ferreira, C.; Borges, M.; Aires, I.; Amaral, T.; Gil, C.; Cortez, J.; Ferreira, A. Cholecalciferol supplementation in hemodialysis patients: Effects on mineral metabolism, inflammation, and cardiac dimension parameters. Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2010, 5, 905–911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tokmak, F.; Quack, I.; Schieren, G.; Sellin, L.; Rattensperger, D.; Holland-Letz, T.; Weiner, S.M.; Rump, L.C. High-dose cholecalciferol to correct vitamin D deficiency in haemodialysis patients. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 2008, 23, 4016–4020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, Y.M.; Kao, C.L.; Hung, K.C.; Liu, T.H.; Yu, T.; Liu, M.Y.; Wu, J.Y.; Tsai, C.L. Major adverse kidney events among chronic kidney disease patients with vitamin D deficiency. Front. Nutr. 2025, 12, 1650514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, K.C.; Wang, J.; Zheng, C.M.; Tsai, K.W.; Hou, Y.C.; Lu, C.L. Vitamin D Deficiency and the Clinical Outcomes of Calcimimetic Therapy in Dialysis Patients: A Population-Based Study. Nutrients 2025, 17, 1536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, X.; Liu, Y.; Zheng, P.; Xie, X.; Li, Z.; Yang, R.; Jin, L.; Mei, Z.; Chen, P.; Zhou, L. Effects of active vitamin D analogs and calcimimetic agents on PTH and bone mineral biomarkers in hemodialysis patients with SHPT: A network meta-analysis. Eur. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2024, 80, 1555–1569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeung, W.G.; Palmer, S.C.; Strippoli, G.F.M.; Talbot, B.; Shah, N.; Hawley, C.M.; Toussaint, N.D.; Badve, S.V. Vitamin D Therapy in Adults With CKD: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 2023, 82, 543–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bover, J.; Masso, E.; Gifre, L.; Alfieri, C.; Soler-Majoral, J.; Fusaro, M.; Calabia, J.; Rodriguez-Pena, R.; Rodriguez-Chitiva, N.; Lopez-Baez, V.; et al. Vitamin D and Chronic Kidney Disease Association with Mineral and Bone Disorder: An Appraisal of Tangled Guidelines. Nutrients 2023, 15, 1576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teng, M.; Wolf, M.; Ofsthun, M.N.; Lazarus, J.M.; Hernan, M.A.; Camargo, C.A., Jr.; Thadhani, R. Activated injectable vitamin D and hemodialysis survival: A historical cohort study. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2005, 16, 1115–1125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teng, M.; Wolf, M.; Lowrie, E.; Ofsthun, N.; Lazarus, J.M.; Thadhani, R. Survival of patients undergoing hemodialysis with paricalcitol or calcitriol therapy. N. Engl. J. Med. 2003, 349, 446–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quarles, L.D.; Yohay, D.A.; Carroll, B.A.; Spritzer, C.E.; Minda, S.A.; Bartholomay, D.; Lobaugh, B.A. Prospective trial of pulse oral versus intravenous calcitriol treatment of hyperparathyroidism in ESRD. Kidney Int. 1994, 45, 1710–1721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malberti, F.; Corradi, B.; Cosci, P.; Calliada, F.; Marcelli, D.; Imbasciati, E. Long-term effects of intravenous calcitriol therapy on the control of secondary hyperparathyroidism. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 1996, 28, 704–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Ju, H.; Chen, H.; Wen, W. Comparison of Paricalcitol and Calcitriol in Dialysis Patients with Secondary Hyperparathyroidism: A Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Studies. Ther. Apher. Dial. 2019, 23, 73–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thadhani, R.I.; Rosen, S.; Ofsthun, N.J.; Usvyat, L.A.; Dalrymple, L.S.; Maddux, F.W.; Hymes, J.L. Conversion from Intravenous Vitamin D Analogs to Oral Calcitriol in Patients Receiving Maintenance Hemodialysis. Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2020, 15, 384–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmer, S.C.; McGregor, D.O.; Macaskill, P.; Craig, J.C.; Elder, G.J.; Strippoli, G.F. Meta-analysis: Vitamin D compounds in chronic kidney disease. Ann. Intern. Med. 2007, 147, 840–853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tonelli, M. Vitamin D in patients with chronic kidney disease: Nothing new under the sun. Ann. Intern. Med. 2007, 147, 880–881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singer, R.; Chacko, B.; Talaulikar, G.; Karpe, K.; Walters, G. Placebo-controlled, randomized clinical trial of high-dose cholecalciferol in renal dialysis patients: Effect on muscle strength and quality of life. Clin. Kidney J. 2019, 12, 281–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morrone, L.; Palmer, S.C.; Saglimbene, V.M.; Perna, A.; Cianciolo, G.; Russo, D.; Gesualdo, L.; Natale, P.; Santoro, A.; Mazzaferro, S.; et al. Calcifediol supplementation in adults on hemodialysis: A randomized controlled trial. J. Nephrol. 2022, 35, 517–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brimble, K.S.; Ganame, J.; Margetts, P.; Jain, A.; Perl, J.; Walsh, M.; Bosch, J.; Yusuf, S.; Beshay, S.; Su, W.; et al. Impact of Bioelectrical Impedance-Guided Fluid Management and Vitamin D Supplementation on Left Ventricular Mass in Patients Receiving Peritoneal Dialysis: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 2022, 79, 820–831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gregorio, P.C.; Bucharles, S.; Cunha, R.S.D.; Braga, T.; Almeida, A.C.; Henneberg, R.; Stinghen, A.E.M.; Barreto, F.C. In vitro anti-inflammatory effects of vitamin D supplementation may be blurred in hemodialysis patients. Clinics 2021, 76, e1821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mose, F.H.; Vase, H.; Larsen, T.; Kancir, A.S.; Kosierkiewic, R.; Jonczy, B.; Hansen, A.B.; Oczachowska-Kulik, A.E.; Thomsen, I.M.; Bech, J.N.; et al. Cardiovascular effects of cholecalciferol treatment in dialysis patients—A randomized controlled trial. BMC Nephrol. 2014, 15, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seirafian, S.; Haghdarsaheli, Y.; Mortazavi, M.; Hosseini, M.; Moeinzadeh, F. The effect of oral vitamin D on serum level of N-terminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide. Adv. Biomed. Res. 2014, 3, 261. [Google Scholar]

- Saleem, A.; Padakanti, S.S.; Hajjaj, M.; Akram, M.S.; Siddenthi, S.M.; Kumari, V.; Gandhi, F.; Sakhamuri, L.T.; Belletieri, C.; Erravelli, P.K.; et al. Effects of Vitamin D Supplementation on Cardiovascular Outcomes in Chronic Kidney Disease Patients: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Cureus 2025, 17, e87378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, S.; Yang, K.; Shang, Y.; Yu, R.; Liu, L.; Jin, J.; He, Q. Effect of regulated vitamin D increase on vascular markers in patients with chronic kidney disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Nutr. Metab. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2024, 34, 33–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamaguchi, S.; Hamano, T.; Yonemoto, S.; Fujii, N.; Isaka, Y. Low-dosage active vitamin D modifies the relationship between hypocalcemia and overhydration in patients with advanced chronic kidney disease. J. Nephrol. 2024, 37, 535–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Liu, Y.; Lian, Y.; Li, N.; Liu, H.; Li, G. Efficacy of High-Dose Supplementation with Oral Vitamin D3 on Depressive Symptoms in Dialysis Patients with Vitamin D3 Insufficiency: A Prospective, Randomized, Double-Blind Study. J. Clin. Psychopharmacol. 2016, 36, 229–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meireles, M.S.; Kamimura, M.A.; Dalboni, M.A.; Giffoni de Carvalho, J.T.; Aoike, D.T.; Cuppari, L. Effect of cholecalciferol on vitamin D-regulatory proteins in monocytes and on inflammatory markers in dialysis patients: A randomized controlled trial. Clin. Nutr. 2016, 35, 1251–1258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seibert, E.; Heine, G.H.; Ulrich, C.; Seiler, S.; Kohler, H.; Girndt, M. Influence of cholecalciferol supplementation in hemodialysis patients on monocyte subsets: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial. Nephron Clin. Pract. 2013, 123, 209–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murashima, M.; Yamamoto, R.; Kanda, E.; Kurita, N.; Noma, H.; Hamano, T.; Fukagawa, M. Associations of vitamin D receptor activators and calcimimetics with falls and effect modifications by physical activity: A prospective cohort study on the Japan Dialysis Outcomes and Practice Patterns Study. Ther. Apher. Dial. 2024, 28, 547–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komaba, H.; Zhao, J.; Karaboyas, A.; Yamamoto, S.; Dasgupta, I.; Hassan, M.; Zuo, L.; Christensson, A.; Combe, C.; Robinson, B.M.; et al. Active Vitamin D Use and Fractures in Hemodialysis Patients: Results from the International DOPPS. J. Bone Miner. Res. 2023, 38, 1577–1585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emarah, S.M.; Ahmed, M.; El Kannishy, G.M.; Abdulgalil, A.E. Effect of vitamin D supplementation on management of anemia in hemodialysis patients with vitamin D deficiency: A double-blind, randomized, controlled trial. Hemodial. Int. 2024, 28, 51–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liakopoulos, V.; Roumeliotis, S.; Gorny, X.; Dounousi, E.; Mertens, P.R. Oxidative Stress in Hemodialysis Patients: A Review of the Literature. Oxidative Med. Cell. Longev. 2017, 2017, 3081856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tamadon, M.R.; Soleimani, A.; Keneshlou, F.; Mojarrad, M.Z.; Bahmani, F.; Naseri, A.; Kashani, H.H.; Hosseini, E.S.; Asemi, Z. Clinical Trial on the Effects of Vitamin D Supplementation on Metabolic Profiles in Diabetic Hemodialysis. Horm. Metab. Res. 2018, 50, 50–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haddad Kashani, H.; Seyed Hosseini, E.; Nikzad, H.; Soleimani, A.; Soleimani, M.; Tamadon, M.R.; Keneshlou, F.; Asemi, Z. The Effects of Vitamin D Supplementation on Signaling Pathway of Inflammation and Oxidative Stress in Diabetic Hemodialysis: A Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Trial. Front. Pharmacol. 2018, 9, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roumeliotis, S.; Dounousi, E.; Salmas, M.; Eleftheriadis, T.; Liakopoulos, V. Vascular Calcification in Chronic Kidney Disease: The Role of Vitamin K- Dependent Matrix Gla Protein. Front. Med. 2020, 7, 154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Ballegooijen, A.J.; Pilz, S.; Tomaschitz, A.; Grubler, M.R.; Verheyen, N. The Synergistic Interplay between Vitamins D and K for Bone and Cardiovascular Health: A Narrative Review. Int. J. Endocrinol. 2017, 2017, 7454376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hung, A.M.; Sundell, M.B.; Plotnikova, N.E.; Bian, A.; Shintani, A.; Ellis, C.D.; Siew, E.D.; Ikizler, T.A. A pilot study of active vitamin D administration and insulin resistance in African American patients undergoing chronic hemodialysis. J. Ren. Nutr. 2013, 23, 185–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosseini, E.S.; Kashani, H.H.; Nikzad, H.; Soleimani, A.; Mirzaei, H.; Tamadon, M.R.; Asemi, Z. Diabetic Hemodialysis: Vitamin D Supplementation and its Related Signaling Pathways Involved in Insulin and Lipid Metabolism. Curr. Mol. Med. 2019, 19, 570–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raggi, P.; Chertow, G.M.; Torres, P.U.; Csiky, B.; Naso, A.; Nossuli, K.; Moustafa, M.; Goodman, W.G.; Lopez, N.; Downey, G.; et al. The ADVANCE study: A randomized study to evaluate the effects of cinacalcet plus low-dose vitamin D on vascular calcification in patients on hemodialysis. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 2011, 26, 1327–1339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Borolossy, R.; El-Farsy, M.S. The impact of vitamin K2 and native vitamin D supplementation on vascular calcification in pediatric patients on regular hemodialysis. A randomized controlled trial. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2022, 76, 848–854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hansen, D.; Rasmussen, K.; Rasmussen, L.M.; Bruunsgaard, H.; Brandi, L. The influence of vitamin D analogs on calcification modulators, N-terminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide and inflammatory markers in hemodialysis patients: A randomized crossover study. BMC Nephrol. 2014, 15, 130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mann, M.C.; Exner, D.V.; Hemmelgarn, B.R.; Hanley, D.A.; Turin, T.C.; MacRae, J.M.; Ahmed, S.B. The VITAH trial VITamin D supplementation and cardiac Autonomic tone in Hemodialysis: A blinded, randomized controlled trial. BMC Nephrol. 2014, 15, 129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nata, N.; Siricheepchaiyan, W.; Supasyndh, O.; Satirapoj, B. Efficacy of high versus conventional dose of ergocalciferol supplementation on serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D and interleukin-6 levels among hemodialysis patients with vitamin D deficiency: A multicenter, randomized, controlled study. Ther. Apher. Dial. 2022, 26, 378–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, J.Q.; Hou, Y.C.; Zheng, C.M.; Lu, C.L.; Liu, W.C.; Wu, C.C.; Huang, M.T.; Lin, Y.F.; Lu, K.C. Cholecalciferol Additively Reduces Serum Parathyroid Hormone and Increases Vitamin D and Cathelicidin Levels in Paricalcitol-Treated Secondary Hyperparathyroid Hemodialysis Patients. Nutrients 2016, 8, 708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulrich, C.; Trojanowicz, B.; Fiedler, R.; Kraus, F.B.; Stangl, G.I.; Girndt, M.; Seibert, E. Serum Testosterone Levels Are Not Modified by Vitamin D Supplementation in Dialysis Patients and Healthy Subjects. Nephron 2021, 145, 481–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Study/Ref. | Population | Treatment | Study Period | Outcome | Result |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Zitt et al. [61] |

56 HD patients with

25(OH)D < 20 ng/mL | 100 IU p.o cholecalciferol/kg body weight 1/week | 26 weeks | Difference in 25(OH)D3 Ca P PTH | Increase (p = 0.01) No difference No difference Decrease (p = 0.01) |

| Bhan et al. [63] | 105 HD patients with 25(OH)D levels ≤ 32 ng/mL |

50,000 IU po ergocalciferol

1/week or 1/month or placebo | 12 weeks | Difference in 25(OH)D3 Ca P PTH | Increase (p = 0.001) No difference No difference No difference |

| Armas et al. [64] | 42 HD patients with 25(OH)D < 16.2 ng/mL |

10,133 IU p.o

cholecalciferol 1/week | 15 weeks | Difference in 25(OH)D3 Ca P PTH | Increase (p < 0.001) No difference No difference No difference |

| Kooienga et al. [65] | 610 elderly women with predialysis CKD and 25(OH)D < 15 ng/mL | 1200 mg tricalcium phosphate and 800 IU cholecalciferol | 24 months | Difference in 25(OH)D3 Ca P PTH | Increase No difference No difference Decrease |

| Marckmann et al. [67] |

25 CKD patients

and 27 HD patients with 25(OH)D < 50 nmol/L |

40,000 IU p.o

cholecalciferol 1/week | 8 weeks | Difference in 25(OH)D3 Ca P PTH Difference in 25(OH)D3 Ca P PTH | CKD Increase (p < 0.001) No difference No difference Decrease (p < 0.001) HD Increase (p < 0.001) No difference No difference No difference |

| Wasse et al. [68] | 52 HD patients with 25(OH)D < 25.5 ng/mL | 200,000 IU p.o cholecalciferol 1/wk | 3 weeks | Difference in 25(OH)D3 Ca P PTH | Increase (p < 0.001) No difference No difference No difference |

| Miskulin et al. [70] | 276 HD patients with 25(OH)D < 22.6 ng/mL |

p.o ergocalciferol

50,000 IU 1/week for 6 months for patients with 25(OH)D ≤ 15 ng/m, 50,000 IU 1/week for the first 3 months followed by 50,000 IU 1/month for another 3 months when 25(OH)D was between 16 and 30 ng/mL | 6 months | Difference in 25(OH)D3 Ca P PTH | Increase (p < 0.001) No difference No difference No difference |

| Hewit et al. [71] |

60 HD patients with

25(OH)D ≤ 24 ng/mL |

50,000 IU p.o cholecalciferol

1/week for 8 weeks and then 1/month for 4 months | 6 months | Difference in 25(OH)D3 Ca P PTH Episodes of hypercalcemia Episodes of hyperphosphatemia | Increase (p < 0.001) No difference Decrease (p = 0.03) No difference No difference |

| Alsahawey et al. [72] | 60 HD patients | 200,000 IU per os cholecalciferol 1/month | 3 months | Difference in 25(OH)D3 Ca P PTH Adverse events | Increase (p < 0.001) No difference No difference No difference No difference |

| Matias et al. [73] | 158 HD patients |

p.o cholecaliferol

50,000 IU 1/week for patients with 25(OH)D levels < 15 ng/mL, 10,000 IU 1/week when 25(OH)D was between 16 and 30 ng/mL, 2700 IU 3/week when levels were >30 ng/mL | 12 months | Difference in 25(OH)D3 Ca P PTH | Increase (p < 0.001) Decrease (p = 0.014) Decrease (p = 0.011) Decrease (p < 0.0001) |

| Tokmak et al. [74] | 64 HD patients |

20,000 IU cholecalciferol p.o

1/week for 9 months. Followed by 20,000 IU cholecalciferol p.o 1/month for 15 months | 24 months | Difference in 25(OH)D3 Ca P PTH | Increase (p < 0.001) Increased (p < 0.01) No difference No difference |

| Study Ref. | Population | Treatment | Study Period | Outcome | Result |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Glycemic and lipid metabolism | |||||

| Hung et al. [108] | 10 HD treated with paracalcitol |

Cinacalcet

or restart paracalcitol | 8 weeks |

GDR

HOMA-IR QUICKY |

No change

No change No change |

| Hosseini et al. [109] | 55 diabetic HD |

Vit. D 50,000 IU/15 days

vs. placebo | 12 weeks |

PPAR-γ

PI3K IRS1, IRS2 GLUT-4 PKC LDLR, Lp(a) PDK1 |

↑

expression of PPAR-γ, AKT, PI3K, IRS1, and GLUT4 genes

↓ expression of PKC and LDLR genes No change in PDK1, IRS2, and Lp(a) expression |

| Tamadon et al. [104] | 60 diabetic HD | Vit. D3 50,000 IU/15 days vs. placebo | 12 weeks | Insulin concentration HOMA-IR QUICKI Lipid metabolism parameters | ↓ insulin ↓ HOMA-IR ↑ QUICKY Lipid metabolism parameters: no change |

| Anemia | |||||

| Emarah et al. [102] | 100 anemic HD patients with vitamin D deficiency | Vit. D 50,000 IU monthly vs. placebo | 6 months | Markers of anemia management | Ferritin, iron, transferrin saturation: no change ↑ Hb and ↓ EPO dosage |

| Miskulin et al. [70] | 276 HD with serum 25(OH)D < 30 ng/mL | Ergocalciferol vs. placebo | 6 months | EPO dosage | No change |

| Matias et al. [73] | 158 HD |

Cholecalciferol

−50.000 IU 1/week for patients with 25(OH)D < 15 ng/mL −10,000 IU 1/week for 16 < 25(OH)D < 30 ng/mL −2700 IU 3/week for 25(OH)D > 30 ng/mL | 12 months | EPO dosage | ↓ (p = 0.013) |

| Cardiovascular system and hard endpoints | |||||

| Raggi et al. [110] | 360 HD with SHPT and CAC scores ≥ 30 |

Cinacalcet (30–180 mg/day) + low-dose calcitriol

vs. flexible vitamin D | 52 weeks | Progression of vascular and cardiac valve calcification (% change of CAC score) | Cinacalcet group: slower progression of CAC scores and volume scoring |

| El Borolossy et al. [111] | 60 children HD |

100 µg MK-7

vs. 10 µg vit. D vs. 100 µg MK-7+ 10 µg vit. D vs. controls | 4 months | Vascular calcification regulators | The group treated with 100 µg MK-7+ 10 µg vit. D showed the most significant ↓ in dp-ucMGP, uc-OC; no change in FGF-23 |

| Hewit et al. [71] | 60 HD with 25(OH)D < 24 ng/mL |

Cholecalciferol, 50,000 IU/week for 8 weeks followed by

50,000 IU/month for 4 months | 6 months |

Pulse wave velocity

Muscle strength Functional capacity Quality of life |

No change

No change No change No change |

| Hansen et al. [112] | 57 HD |

Paricalcitol

vs. alfacalcidol | 16 weeks | Vascular calcification regulators |

NT-proBNP and osteoprotegerin

↑

in both groups Fetuin-A significantly in the alfacalcidol-treated group |

| Miskulin et al. [70] | 276 HD with serum 25(OH)D < 30 ng/mL |

Ergocalciferol

vs. placebo | 6 months | All-cause, cardiovascular-related hospitalizations | No change |

| Bhan et al. [63] | 105 HD with 25(OH)D ≤ 32 ng/mL |

Ergocalciferol, 50,000 IU/week

vs. Ergocalciferol, 50,000 IU/month vs. placebo | 12 weeks | All-cause and cause-specific hospitalizations | No change |

| Mann et al. [113] | 56 HD |

2 × 2 crossover RCT

Intensive (alfacalcidol) 0.25 mcg, thrice weekly + ergocalciferol 50.000 IU/week vs. standard (alfacalcidol) 0.25 mcg thrice weekly for 6 weeks | 6 weeks |

Cardiac autonomic tone

low frequency to high-frequency spectral ratio |

↑

low-frequency to high-frequency spectral ratio only in patients with 25[OH]D < 20 ng/mL) |

| Immune and endocrine system | |||||

| Nata et al. [114] | 70 HD with 25[OH]D level < 30 ng/mL | Ergocalciferol Conventional (50.000 IU/month for 25[OH]D between 20 and 29.9 ng/mL and 50.000 IU/week for <20 ng/mL) vs. high dose (100.000 IU/month for 25[OH]D between 20 and 29.9 ng/mL and 100.000 IU/week for <20 ng/mL) | 8 weeks | IL-6 | In patients with 25[OH]D < 20 ng/mL, high-dose treatment ↓ serum IL-6 level (−2.67 pg/mL [IQR −6.56 to −0.17], p = 0.039) |

| Gregorio et al. [91] | 32 HD |

Cholecalciferol

vs. placebo | 6 months |

Circulating IL-1β and hs-CRP levels

In vitro OS markers (monocyte viability, ROS production, and CAMP expression) |

Circulating IL-1b and hs-CRP: no change

↓ all OS markers |

| Meireles et al. [98] | 38 HD with 25(OH)D < 20 ng/mL |

Cholecalciferol group 50,000 IU/twice weekly

vs. placebo | 12 weeks | Expression of VDR, CYP27B1, CYP24A1, and IL-6 in monocytes; serum concentrations of IL-6, TNF-α, CRP |

↑

CYP27B1

↑

VDR expression

No changes in IL-6 and CYP24A1 ↓ serum concentration of IL-6 and CRP |

| Hansen et al. [112] | 57 HD |

Paricalcitol

vs. alfacalcidol | 16 weeks |

IL-6

TNF- α hs-CRP | No change |

| Tamadon et al. [104] | 60 diabetic HD |

Vit. D3 50,000 IU/15 days

vs. placebo | 12 weeks |

Hs-CRP

MDA TAC | ↓ Hs-CRP ↓ MDA ↑ TAC |

| Zheng et al. [115] | 60 HD with SHPT (PTH > 300 pg/mL) receiving 2 mcg/day of paricalcitol |

Cholecalciferol 5000 IU/week

vs. placebo | 16 weeks | hCAP-18 | ↑ |

| Miskulin et al. [70] | 276 HD with serum 25(OH)D < 30 ng/mL |

Ergocalciferol

vs. placebo | 6 months |

CRP

Infection-related hospitalizations |

No change

No change |

| Matias et al. [73] | 158 HD |

Cholecalciferol

−50.000 IU 1/week for patients with 25(OH)D < 15 ng/mL −10,000 IU 1/week for 16 < 25(OH)D < 30 ng/mL −2700 IU 3/week for 25(OH)D > 30 ng/mL | 12 months | CRP | ↓ (p = 0.004) |

| Hung et al. [108] | 10 HD treated with paracalcitol |

Cinacalcet

or restart paracalcitol | 8 weeks |

Hs-CRP

IL-6 Adiponectin and leptin |

No change

No change No change |

| Ulrich et al. [116] | 33 HD |

Cholecalciferol

vs. placebo | 12 weeks | Serum testosterone levels | No change |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kantartzi, K.; Roumeliotis, S.; Polychronidis, C.; Zafeiri, E.; Roumeliotis, A.; Leivaditis, K.; Liakopoulos, V. Vitamin D and Vitamin D Analogues in Hemodialysis Patients: A Review of the Literature. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 11550. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311550

Kantartzi K, Roumeliotis S, Polychronidis C, Zafeiri E, Roumeliotis A, Leivaditis K, Liakopoulos V. Vitamin D and Vitamin D Analogues in Hemodialysis Patients: A Review of the Literature. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2025; 26(23):11550. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311550

Chicago/Turabian StyleKantartzi, Konstantia, Stefanos Roumeliotis, Christos Polychronidis, Elena Zafeiri, Athanasios Roumeliotis, Konstantinos Leivaditis, and Vassilios Liakopoulos. 2025. "Vitamin D and Vitamin D Analogues in Hemodialysis Patients: A Review of the Literature" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 26, no. 23: 11550. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311550

APA StyleKantartzi, K., Roumeliotis, S., Polychronidis, C., Zafeiri, E., Roumeliotis, A., Leivaditis, K., & Liakopoulos, V. (2025). Vitamin D and Vitamin D Analogues in Hemodialysis Patients: A Review of the Literature. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 26(23), 11550. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311550