Prebiotic and Functional Fibers from Micro- and Macroalgae: Gut Microbiota Modulation, Health Benefits, and Food Applications

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Algal Polysaccharides

2.1. Sulfated Polysaccharides

2.1.1. Fucoidan

2.1.2. Carrageenan

2.1.3. Ulvan

2.1.4. Porphyran

2.1.5. Agar

2.2. Non-Sulfated Polysaccharides

2.2.1. β-Glucan

2.2.2. Alginate

2.3. Extracellular Polysaccharides

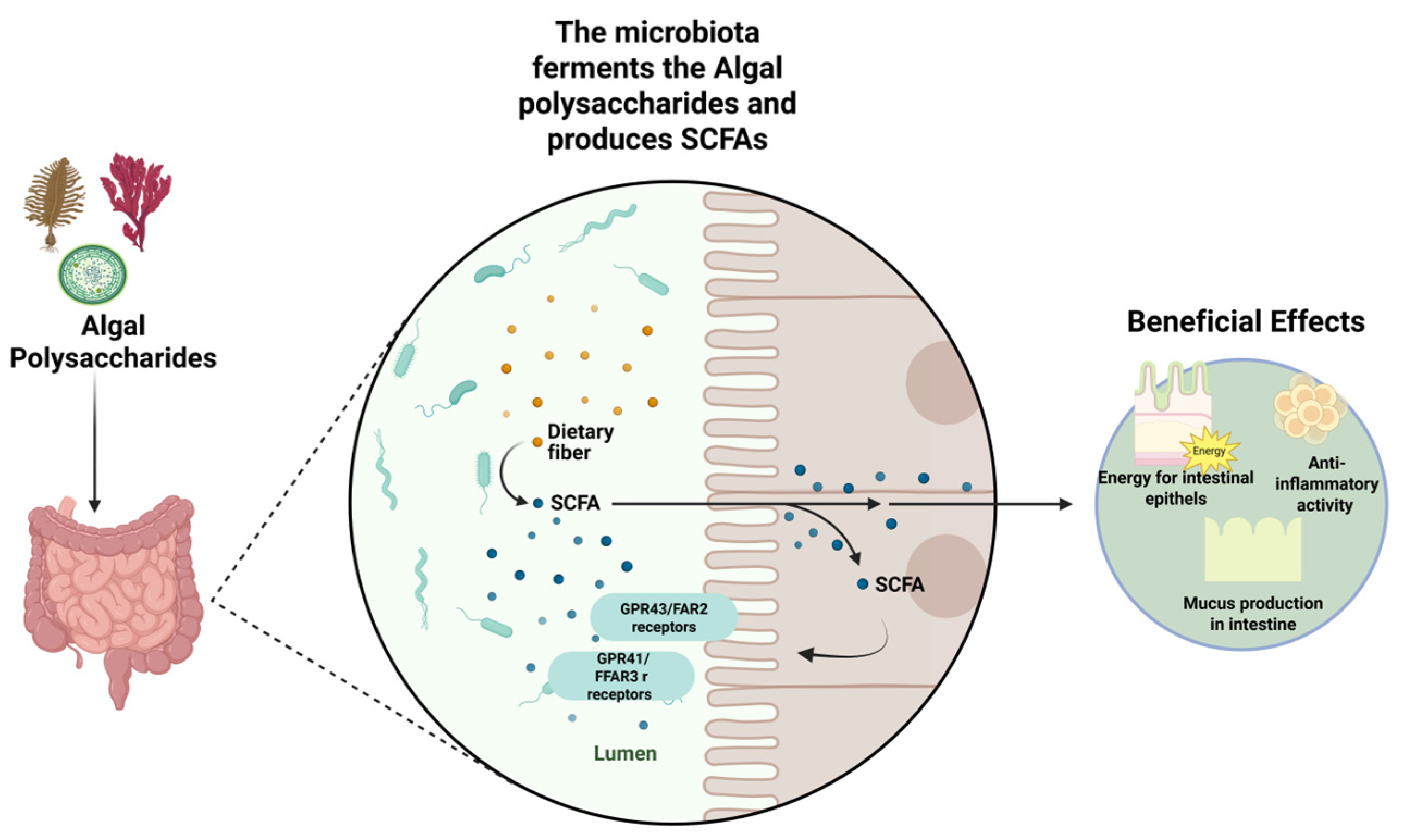

3. Fermentation by Gut Microbiota

4. Health Benefits

4.1. Anti-Inflammatory and Barrier Function Improvement Properties

4.2. Metabolic Management and Effects on Weight

4.3. Antioxidant Properties

4.4. Antimicrobial Properties

4.5. Immunomodulatory and Anticancer Properties

4.6. Anticoagulation—Antithrombotic and Antiplatelet Properties

4.7. Neuroprotective Properties

| Polysaccharides | Algae | Method | Activity | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fucoidan | Saccharina japonica | in vitro (ABTS, FRAP tests) in vivo (H22 tumor mice) | The antioxidant capacity was found to be 1.02 mg TE/g and 5.39 mg TE/g, respectively, based on the results of the ABTS and FRAP tests. A 42.93% reduction in tumor volume was observed in the H22 tumor mouse model. | [122] |

| Fucoidan | Laminaria japonica | in vivo (Rotenone-induced Parkinson’s disease in mice) | It has reduced neuroinflammation and prevented damage to dopaminergic neurons. Parkinson’s disease in mice has significantly improved ROT-induced Parkinsonism by regulating the microbiota-gut–brain axis. | [22] |

| EPS | Coelastrella sp. BGV | in vitro (human cell line) | The MTT test showed that it reduced cell viability in HeLa (cervical cancer) and MCF-7 (breast cancer) cell lines. | [121] |

| Sulfated EPS | Chlorella sp. | in vitro anti-α-d-Glucosidase activity (Human-derived enzyme) | It inhibited the α-d-glucosidase enzyme by 80.94 ± 0.01% and the IC50 value was determined to be 4.31 ± 0.20 mg/mL. | [115] |

| Alginate oligosaccharides (AOS) and β-glucans | Laminaria (AOS), Euglena gracilis (β-glucans) | in vivo (zebrafish) | AOS suppressed soy-induced intestinal inflammation, increasing goblet cell numbers, extending villus length, and regulating anti-inflammatory gene expression. β-glucan suppressed endopeptidase activity and proteolysis-related immune genes in zebrafish, exhibiting tissue damage-reducing and antioxidant effects. | [114] |

| Sulfated polysaccharides | Chaetomorpha aerea | in vitro (APTT, TT, PT, and fibrinogen level) in vivo (rats) | Inhibits factors XII, XI, IX, and VIII in the intrinsic pathway and stops the coagulation process by suppressing the activity of thrombin and factor Xa via antithrombin III and heparin cofactor II. | [126] |

| Laminarin | Laminaria digitata | in vivo (mice) | In atopic dermatitis-like skin lesions, laminarin alleviates inflammation and modulates immune responses by suppressing IgE hyperproduction, mast cell infiltration, and the release of pro-inflammatory cytokines such as IL-1β, TNF-α, MCP-1, and MIP-1α. | [41] |

| EPS | Botryococcus braunii SCS-1905 | in vitro (ABTS, hydroxyl, DPPH, superoxide anion radical scavenging assay) | It suppressed the formation of hydroxyl radicals by chelating Fe2+ ions. | [117] |

| Fucoidan | Saccharina dentigera | in vitro (soft agar assay) | It exhibited a pronounced and non-toxic anticancer activity by inhibiting colony formation in human small intestine adenocarcinoma (HuTu 80), malignant melanoma (RPMI-7951), and colorectal adenocarcinoma (HCT-116) cells. | [128] |

| Sulfated Galactan | Botryocladia occidentalis | in vitro (glial cells from mice) | HIV-1 proteins Tat and gp120 have shown neuroprotective activity. | [127] |

| Iota-Carrageenan | Red algae * | in vitro (human Calu-3 cells) | In Calu-3, it inhibited SARS-CoV-2 replication in a dose-dependent manner; particularly when administered prior to infection, it demonstrated a potent antiviral effect by blocking the viral entry phase. | [119] |

| Agar and derivatives (3,6-Anhidro-L-galactose) | Red algae * | in vitro (HCT-116 human colon cancer cells and CCD-18Co normal colon fibroblasts) | It significantly inhibited the proliferation of HCT-116 cells and induced apoptosis, but did not show any toxic effects on CCD-18Co cells. | [104] |

| Lambda-Carrageenan | Red algae * | in vitro (Human Calu-3 cells) | It has been shown to inhibit SARS-CoV-2 replication in a dose-dependent manner, particularly when administered prior to infection, demonstrating a potent antiviral effect by blocking viral entry. | [118] |

| Fucoidan | Undaria pinnatifida, Fucus vesiculosus, Macrocystis pyrifera, Ascophyllum nodosum, Laminaria japonica | in vitro (Human peripheral blood mononuclear cells, THP-1) | It has inhibited the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines such as TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-6. | [67] |

| β-1,3-glucans | Euglena gracilis | in vitro (Portunus trituberculatus hemocytes) | It has been shown to stimulate the immune system by increasing phenol oxidase, lysozyme, acid phosphatase, superoxide anion production, and superoxide dismutase activity. | [129] |

| Polysaccharides derived from Enteromorpha clathrata | Enteromorpha clathrata | in vivo (mice fed a high-fat diet) | It has been shown to alleviate obesity by improving intestinal dysbiosis. | [98] |

| Fucoidan | Saccharina japonica | in vitro (RAW 264.7 macrophage cell line) in vivo (zebrafish) | LPS-stimulated RAW 264. 7 macrophage cell line, LPS-induced RAW 264.7 macrophages, thereby inhibiting the iNOS, COX-2, MAPK, and NF-κB signaling pathways. In vivo, it demonstrated a potent anti-inflammatory effect by reducing cell death, ROS, and NO production in zebrafish embryos and improving heart and survival rate. | [21] |

| Alginate | Brown algae | in vitro digestion in vivo (rats) | It delays food digestion by forming a gel in the stomach, increases the feeling of satiety in the short term, and reduces food intake, body weight, and blood sugar spikes in the long term. | [20] |

| Fucoidan | Fucus evanescens | in vitro (Vero, MT-4 cells) in vivo (mice) | It has shown antiviral, anti-inflammatory and immunomodulatory effects against HSV-1, HSV-2, ECHO-1, and HIV-1. | [130] |

| Sulfated polysaccharides | Sargassum fulvellum | in vitro (Vero cells) in vivo (zebrafish) | These polysaccharides have been shown to exhibit activities including free radical scavenging, ROS suppression, enhancement of cell viability, prevention of apoptosis, regulation of heart rate, reduction in lipid peroxidation, and prevention of cell death. | [116] |

| Sulfated polysaccharides | Bangia fusco-purpurea | in vitro (Porcine, Saccharomyces cerevisiae Enzyme inhibition assay | They inhibited α-glucosidase in a concentration-dependent manner. | [19] |

| Fucoidan | Fucus vesiculosus | in vitro (bacterial culture) | It has shown significant antimicrobial and antibiofilm activity against dental plaque bacteria; in particular, it completely inhibited biofilm formation and planktonic cell growth of Streptococcus mutans and Streptococcus sobrinus at concentrations above 250 µg/mL. | [120] |

| Laminarin, Fucoidan | Laminaria digitata | in vivo (broiler chicks) | They have improved growth performance in broiler chicks, improved intestinal villus architecture, and modulated the immune response, but has not affected Campylobacter jejuni colonization. | [103] |

| Fucoidan | Fucus vesiculosus | in vitro (Huh-7, SNU-761, SNU-3058 cell line) in vivo (BALB/c nude mice) | It has reduced proliferation in hepatocellular carcinoma cells by suppressing ID-1 and inhibited invasion and metastasis in both in vitro and in vivo models. | [131] |

| Sulfated Polysaccharides | Ulva fasciata, Agardhiella subulata | in vitro (human blood samples) | They prevent blood clotting by prolonging prothrombin time (PT) and activated partial thromboplastin time (APTT) durations. | [125] |

| Lambda-Carrageenan | Red algae * | in vivo (mice B16-F10, 4T1, E.G7-OVA cell lines) | When administered by intratumoral injection in B16-F10 melanoma and 4T1 breast tumor models in mice, it suppressed tumor growth and increased the activation of M1 macrophages, dendritic cells, and CD4+/CD8+ T cells. | [23] |

| Fucoidan | Undaria pinnatifida | in vitro (tumor cells MCF-7, A-549, WiDr, Malme-3M, LoVo and normal cells HEK-293, HUVEC and HDFb) | It showed anti-proliferative (cytotoxic) effects in cancer cells, while exhibiting lower toxicity in normal cells. | [123] |

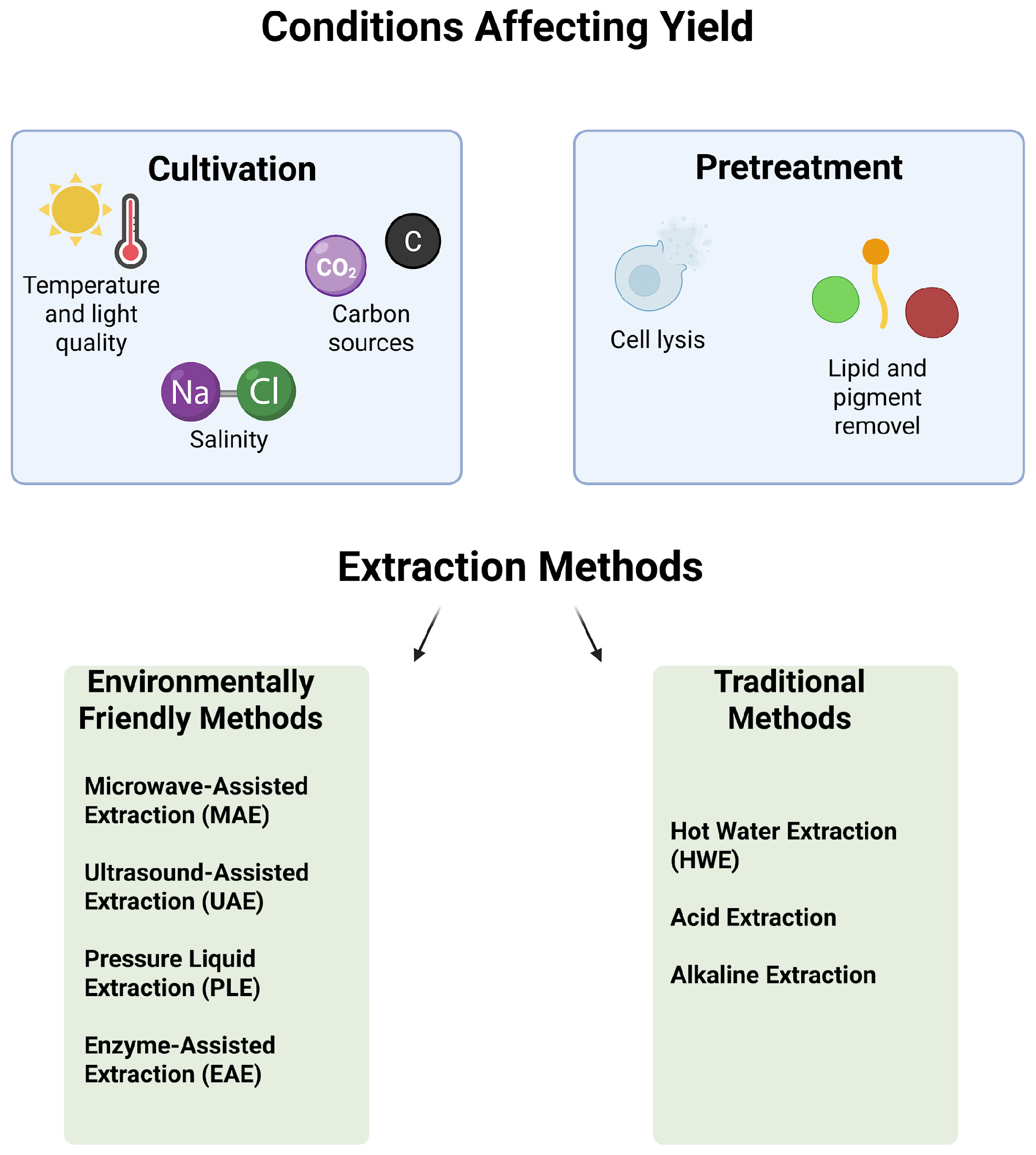

5. Extraction, Processing and Formulation

5.1. Cultivation of Algae for Polysaccharides Yield

5.2. Pretreatment Steps and Extraction Methods

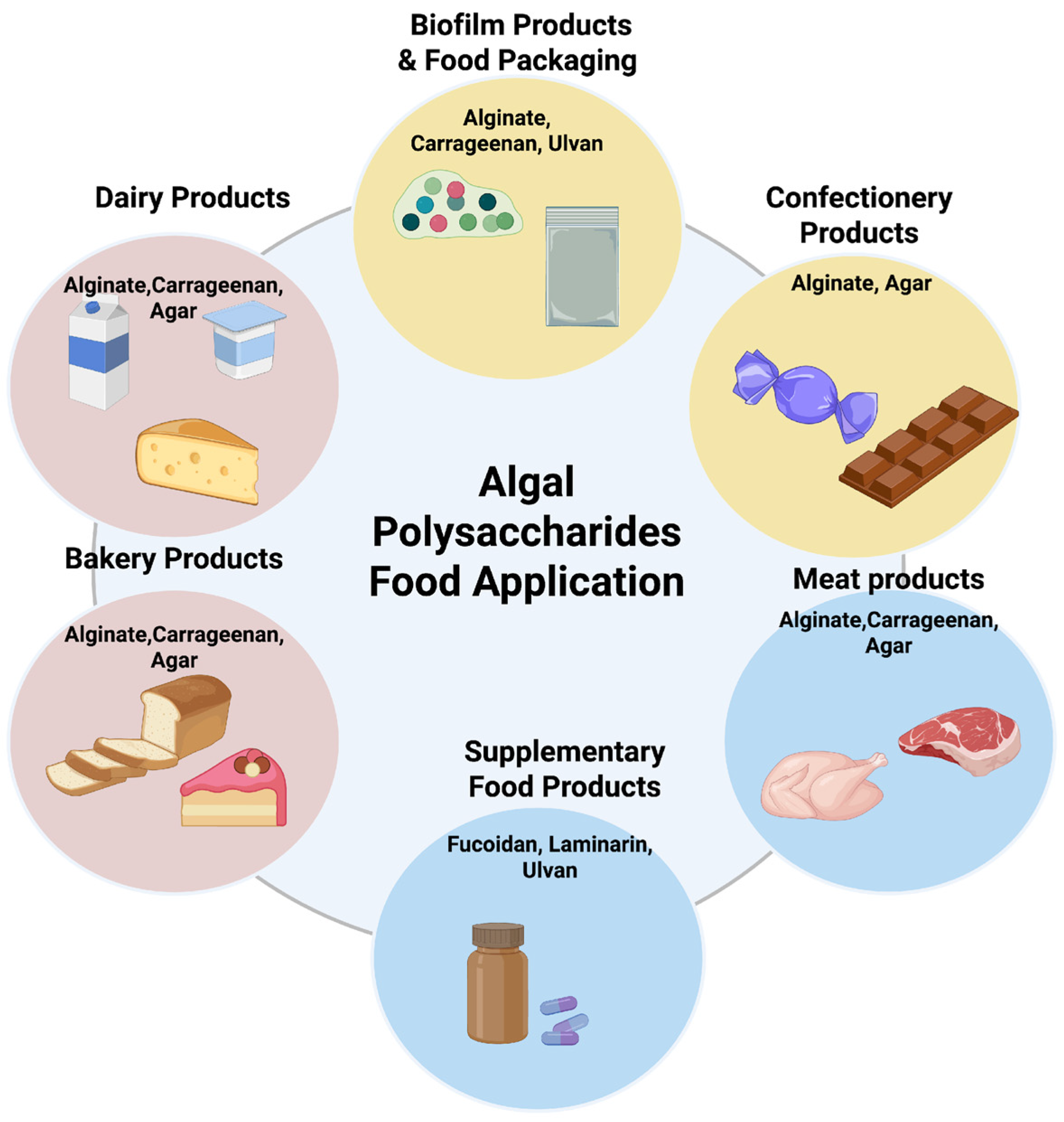

6. Application in Functional Foods and Nutraceuticals

6.1. Applications in Food Products

6.2. Regulation and Safety Consideration

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Victoria Obayomi, O.; Folakemi Olaniran, A.; Olugbemiga Owa, S. Unveiling the Role of Functional Foods with Emphasis on Prebiotics and Probiotics in Human Health: A Review. J. Funct. Foods 2024, 119, 106337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, S.; Shah, B.R.; Li, J.; Liang, H.; Zhan, F.; Geng, F.; Li, B. A Critical Review on Interplay between Dietary Fibers and Gut Microbiota. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2022, 124, 237–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slavin, J.L.; Engstrom, S.K. Carbohydrates. Adv. Nutr. 2024, 15, 100311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezende, E.S.V.; Lima, G.C.; Naves, M.M.V. Dietary Fibers as Beneficial Microbiota Modulators: A Proposal Classification by Prebiotic Categories. Nutrition 2021, 89, 11121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EFSA Panel on Dietetic Products, Nutrition, and Allergies (NDA). Scientific Opinion on Dietary Reference Values for Carbohydrates and Dietary Fibre. EFSA J. 2010, 8, 1462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holscher, H.D. Dietary Fiber and Prebiotics and the Gastrointestinal Microbiota. Gut Microbes 2017, 8, 172–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferreira, V.C.; Barroso, T.L.C.T.; Castro, L.E.N.; da Rosa, R.G.; de Siqueira Oliveira, L. An Overview of Prebiotics and Their Applications in the Food Industry. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 2023, 249, 2957–2976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raw, M.H.; Zaman, S.A.; Pa’ee, K.F.; Leong, S.S.; Sarbini, S.R. Prebiotics Metabolism by Gut-Isolated Probiotics. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2020, 57, 2786–2799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gibson, G.R.; Hutkins, R.; Sanders, M.E.; Prescott, S.L.; Reimer, R.A.; Salminen, S.J.; Scott, K.; Stanton, C.; Swanson, K.S.; Cani, P.D.; et al. Expert Consensus Document: The International Scientific Association for Probiotics and Prebiotics (ISAPP) Consensus Statement on the Definition and Scope of Prebiotics. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2017, 14, 491–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarıtaş, S.; Duman, H.; Pekdemir, B.; Rocha, J.M.; Oz, F.; Karav, S. Functional Chocolate: Exploring Advances in Production and Health Benefits. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2024, 59, 5303–5325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahiya, D.; Singh NIGAM, P. Inclusion of Dietary-Fibers in Nutrition Provides Prebiotic Substrates to Probiotics for the Synthesis of Beneficial Metabolites SCFA to Sustain Gut Health Minimizing Risk of IBS, IBD, CRC. Recent Prog. Nutr. 2023, 03, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheong, K.L.; Liu, Y.; Veeraperumal, S. Editorial: Marine Algal Bioactive Molecules for Food and Pharmaceutical Applications. Front. Mar. Sci. 2025, 12, 1598329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diaz, C.J.; Douglas, K.J.; Kang, K.; Kolarik, A.L.; Malinovski, R.; Torres-Tiji, Y.; Molino, J.V.; Badary, A.; Mayfield, S.P. Developing Algae as a Sustainable Food Source. Front. Nutr. 2023, 9, 1029841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thoré, E.S.J.; Muylaert, K.; Bertram, M.G.; Brodin, T. Microalgae. Curr. Biol. 2023, 33, R91–R95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- da Rosa, M.D.H.; Alves, C.J.; dos Santos, F.N.; de Souza, A.O.; da Rosa Zavareze, E.; Pinto, E.; Noseda, M.D.; Ramos, D.; de Pereira, C.M.P. Macroalgae and Microalgae Biomass as Feedstock for Products Applied to Bioenergy and Food Industry: A Brief Review. Energies 2023, 16, 1820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demarco, M.; Oliveira de Moraes, J.; Matos, Â.P.; Derner, R.B.; de Farias Neves, F.; Tribuzi, G. Digestibility, Bioaccessibility and Bioactivity of Compounds from Algae. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2022, 121, 114–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, W.; Zhou, J.; Xuan, R.; Chen, J.; Han, H.; Liu, J.; Niu, T.; Chen, H.; Wang, F. Dietary κ-Carrageenan Facilitates Gut Microbiota-Mediated Intestinal Inflammation. Carbohydr. Polym. 2022, 277, 118830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Zhang, Y.; Wei, L.; Yang, Y.; Wang, B.; Liu, C.; Bai, J.; Wang, C. In Vitro Fermentation Characteristics of Fucoidan and Its Regulatory Effects on Human Gut Microbiota and Metabolites. Food Chem. 2025, 465, 141998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, Z.; Yu, G.; Liang, Y.; Song, T.; Zhu, Y.; Ni, H.; Yamaguchi, K.; Oda, T. Inhibitory Effects of a Sulfated Polysaccharide Isolated from Edible Red Alga Bangia Fusco-Purpurea on α-Amylase and α-Glucosidase. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 2019, 83, 2065–2074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, L.; Goff, H.D.; Xu, F.; Liu, F.; Ma, J.; Chen, M.; Zhong, F. The Effect of Sodium Alginate on Nutrient Digestion and Metabolic Responses during Both in Vitro and in Vivo Digestion Process. Food Hydrocoll. 2020, 107, 105304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ni, L.; Wang, L.; Fu, X.; Duan, D.; Jeon, Y.J.; Xu, J.; Gao, X. In Vitro and in Vivo Anti-Inflammatory Activities of a Fucose-Rich Fucoidan Isolated from Saccharina Japonica. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2020, 156, 717–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, X.; Zhang, X.; Ma, Y.; Li, S.; Wang, Q.; Hong, J.S.; Yu, G.; Qi, B.; Wang, J.; Liu, C.; et al. Fucoidan Ameliorates Rotenone-Induced Parkinsonism in Mice by Regulating the Microbiota-Gut-Brain Axis. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 283, 137373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, M.; Shao, B.; Nie, W.; Wei, X.W.; Li, Y.L.; Wang, B.L.; He, Z.Y.; Liang, X.; Ye, T.H.; Wei, Y.Q. Antitumor and Adjuvant Activity of λ-Carrageenan by Stimulating Immune Response in Cancer Immunotherapy. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 11062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gouda, M.; Tadda, M.A.; Zhao, Y.; Farmanullah, F.; Chu, B.; Li, X.; He, Y. Microalgae Bioactive Carbohydrates as a Novel Sustainable and Eco-Friendly Source of Prebiotics: Emerging Health Functionality and Recent Technologies for Extraction and Detection. Front. Nutr. 2022, 9, 806692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shannon, E.; Conlon, M.; Hayes, M. Seaweed Components as Potential Modulators of the Gut Microbiota. Mar. Drugs 2021, 19, 358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tammina, S.K.; Priyadarshi, R.; Khan, A.; Manzoor, A.; Rahman, R.S.H.A.; Banat, F. Recent Developments in Alginate-Based Nanocomposite Coatings and Films for Biodegradable Food Packaging Applications. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2025, 295, 139480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Menaa, F.; Wijesinghe, U.; Thiripuranathar, G.; Althobaiti, N.A.; Albalawi, A.E.; Khan, B.A.; Menaa, B. Marine Algae-Derived Bioactive Compounds: A New Wave of Nanodrugs? Mar. Drugs 2021, 19, 484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patel, A.K.; Vadrale, A.P.; Singhania, R.R.; Michaud, P.; Pandey, A.; Chen, S.J.; Chen, C.W.; Dong, C.D. Algal Polysaccharides: Current Status and Future Prospects. Phytochem. Rev. 2023, 22, 1167–1196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lesco, K.C.; Williams, S.K.R.; Laurens, L.M.L. Marine Algae Polysaccharides: An Overview of Characterization Techniques for Structural and Molecular Elucidation. Mar. Drugs 2025, 23, 105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cotas, J.; Tavares, J.O.; Silva, R.; Pereira, L. Seaweed as a Safe Nutraceutical Food: How to Increase Human Welfare? Nutraceuticals 2024, 4, 323–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrasqueira, J.; Bernardino, S.; Bernardino, R.; Afonso, C. Marine-Derived Polysaccharides and Their Potential Health Benefits in Nutraceutical Applications. Mar. Drugs 2025, 23, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bligh, M.; Nguyen, N.; Buck-Wiese, H.; Vidal-Melgosa, S.; Hehemann, J.H. Structures and Functions of Algal Glycans Shape Their Capacity to Sequester Carbon in the Ocean. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 2022, 71, 102204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luis, A.S.; Baslé, A.; Byrne, D.P.; Wright, G.S.A.; London, J.A.; Jin, C.; Karlsson, N.G.; Hansson, G.C.; Eyers, P.A.; Czjzek, M.; et al. Sulfated Glycan Recognition by Carbohydrate Sulfatases of the Human Gut Microbiota. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2022, 18, 841–849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tuvikene, R. Carrageenans. In Handbook of Hydrocolloids; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2021; pp. 767–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Sun, Y.; Nie, Q.; Hu, J.; Li, Y.; Shi, Z.; Ji, H.; Zhang, H.; Zhao, M.; Chen, C.; et al. Effects of Four Food Hydrocolloids on Colitis and Their Regulatory Effect on Gut Microbiota. Carbohydr. Polym. 2024, 323, 121368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- da Silva Chagas, F.D.; Lima, G.C.; dos Santos, V.I.N.; Costa, L.E.C.; de Sousa, W.M.; Sombra, V.G.; de Araújo, D.F.; Barros, F.C.N.; Marinho-Soriano, E.; de Andrade Feitosa, J.P.; et al. Sulfated Polysaccharide from the Red Algae Gelidiella Acerosa: Anticoagulant, Antiplatelet and Antithrombotic Effects. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2020, 159, 415–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jeong, S.; Lee, S.; Lee, G.; Hyun, J.; Ryu, B. Systematic Characteristics of Fucoidan: Intriguing Features for New Pharmacological Interventions. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 11771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saravana, P.S.; Cho, Y.N.; Patil, M.P.; Cho, Y.J.; Kim, G.-D.; Park, Y.B.; Woo, H.C.; Chun, B.S. Hydrothermal Degradation of Seaweed Polysaccharide: Characterization and Biological Activities. Food Chem. 2018, 268, 179–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chadwick, M.; Carvalho, L.G.; Vanegas, C.; Dimartino, S. A Comparative Review of Alternative Fucoidan Extraction Techniques from Seaweed. Mar. Drugs 2025, 23, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Liu, L.; Sun, Z.; Ji, Y.; Wang, D.; Mei, L.; Shen, P.; Li, Z.; Tang, S.; Zhang, H.; et al. Fucoidan as a Marine-Origin Prebiotic Modulates the Growth and Antibacterial Ability of Lactobacillus rhamnosus. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2021, 180, 599–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, T.K.; Kim, D.W.; Ahn, J.H.; Lee, C.H.; Lee, J.C.; Lim, S.S.; Kang, I.J.; Hong, S.; Choi, S.Y.; Won, M.H.; et al. Protective Effects of Topical Administration of Laminarin in Oxazolone-Induced Atopic Dermatitis-like Skin Lesions. Mar. Drugs 2022, 20, 669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoang, N.N.; Nguyen, T.K.; Vo, T.H.; Nguyen, N.H.; Nguyen, D.H.; Tran, D.L. Isolation, Characterization, and Biological Activities of Fucoidan Derived from Ceratophyllum submersum L. Macromol. Res. 2022, 30, 136–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mensah, E.O.; Kanwugu, O.N.; Panda, P.K.; Adadi, P. Marine Fucoidans: Structural, Extraction, Biological Activities and Their Applications in the Food Industry. Food Hydrocoll. 2023, 142, 108784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naseri, A.; Holdt, S.L.; Jacobsen, C. Biochemical and Nutritional Composition of Industrial Red Seaweed Used in Carrageenan Production. J. Aquat. Food Prod. Technol. 2019, 28, 967–973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alba, K.; Kontogiorgos, V. Seaweed polysaccharides (Agar, Alginate carrageenan). In Encyclopedia of Food Chemistry; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2018; pp. 240–250. ISBN 9780128140260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Udo, T.; Mummaleti, G.; Mohan, A.; Singh, R.K.; Kong, F. Current and Emerging Applications of Carrageenan in the Food Industry. Food Res. Int. 2023, 173, 113369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frediansyah, A. The Antiviral Activity of Iota-, Kappa-, and Lambda-Carrageenan against COVID-19: A Critical Review. Clin. Epidemiol. Glob. Health 2021, 12, 100826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Álvarez-Viñas, M.; Souto, S.; Flórez-Fernández, N.; Torres, M.D.; Bandín, I.; Domínguez, H. Antiviral Activity of Carrageenans and Processing Implications. Mar. Drugs 2021, 19, 437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimilu, N.; Gładyś-Cieszyńska, K.; Pieszko, M.; Mańkowska-Wierzbicka, D.; Folwarski, M. Carrageenan in the Diet: Friend or Foe for Inflammatory Bowel Disease? Nutrients 2024, 16, 1780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharyya, S.; Shumard, T.; Xie, H.; Dodda, A.; Varady, K.A.; Feferman, L.; Halline, A.G.; Goldstein, J.L.; Hanauer, S.B.; Tobacman, J.K. A Randomized Trial of the Effects of the No-Carrageenan Diet on Ulcerative Colitis Disease Activity. Nutr. Healthy Aging 2017, 4, 181–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, C.; Tang, T.; Du, Y.; Jiang, L.; Yao, Z.; Ning, L.; Zhu, B. Ulvan and Ulva Oligosaccharides: A Systematic Review of Structure, Preparation, Biological Activities and Applications. Bioresour. Bioprocess 2023, 10, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kidgell, J.T.; Magnusson, M.; de Nys, R.; Glasson, C.R.K. Ulvan: A Systematic Review of Extraction, Composition and Function. Algal Res. 2019, 39, 101422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.; Ouyang, Y.; Chen, R.; Wang, M.; Ai, C.; El-Seedi, H.R.; Sarker, M.M.R.; Chen, X.; Zhao, C. Nutraceutical Potentials of Algal Ulvan for Healthy Aging. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2022, 194, 422–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pradhan, B.; Bhuyan, P.P.; Ki, J.S. Immunomodulatory, Antioxidant, Anticancer, and Pharmacokinetic Activity of Ulvan, a Seaweed-Derived Sulfated Polysaccharide: An Updated Comprehensive Review. Mar. Drugs 2023, 21, 300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lakshmi, D.S.; Sankaranarayanan, S.; Gajaria, T.K.; Li, G.; Kujawski, W.; Kujawa, J.; Navia, R. A Short Review on the Valorization of Green Seaweeds and Ulvan: Feedstock for Chemicals and Biomaterials. Biomolecules 2020, 10, 991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kikionis, S.; Ioannou, E.; Toskas, G.; Roussis, V. Electrospun Biocomposite Nanofibers of Ulvan/PCL and Ulvan/PEO. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2015, 132, 42153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isaka, S.; Cho, K.; Nakazono, S.; Abu, R.; Ueno, M.; Kim, D.; Oda, T. Antioxidant and Anti-Inflammatory Activities of Porphyran Isolated from Discolored Nori (Porphyra yezoensis). Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2015, 74, 68–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, H.M.; Veeraperumal, S.; Lv, J.H.; Wu, T.C.; Zhang, Z.P.; Zeng, Q.K.; Liu, Y.; Chen, X.Q.; Aweya, J.J.; Cheong, K.L. Physicochemical Properties and Potential Beneficial Effects of Porphyran from Porphyra Haitanensis on Intestinal Epithelial Cells. Carbohydr. Polym. 2020, 246, 116626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, S.Y.; Aweya, J.J.; Li, N.; Deng, R.Y.; Chen, W.Y.; Tang, J.; Cheong, K.L. Microbial Catabolism of Porphyra Haitanensis Polysaccharides by Human Gut Microbiota. Food Chem. 2019, 289, 177–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; He, Z.; Liang, Y.; Peng, T.; Hu, Z. Insights into Algal Polysaccharides: A Review of Their Structure, Depolymerases, and Metabolic Pathways. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2022, 70, 1749–1765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Long, H.; Gu, X.; Zhou, N.; Zhu, Z.; Wang, C.; Liu, X.; Zhao, M. Physicochemical Characterization and Bile Acid-Binding Capacity of Water-Extract Polysaccharides Fractionated by Stepwise Ethanol Precipitation from Caulerpa lentillifera. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2020, 150, 654–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Praiboon, J.; Chantorn, S.; Krangkratok, W.; Choosuwan, P.; La-ongkham, O. Evaluating the Prebiotic Properties of Agar Oligosaccharides Obtained from the Red Alga Gracilaria Fisheri via Enzymatic Hydrolysis. Plants 2023, 12, 3958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nigam, S.; Singh, R.; Bhardwaj, S.K.; Sami, R.; Nikolova, M.P.; Chavali, M.; Sinha, S. Perspective on the Therapeutic Applications of Algal Polysaccharides. J. Polym. Environ. 2022, 30, 785–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tolpeznikaite, E.; Bartkevics, V.; Ruzauskas, M.; Pilkaityte, R.; Viskelis, P.; Urbonaviciene, D.; Zavistanaviciute, P.; Zokaityte, E.; Ruibys, R.; Bartkiene, E. Characterization of Macro-and Microalgae Extracts Bioactive Compounds and Micro-and Macroelements Transition from Algae to Extract. Foods 2021, 10, 2226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, S.; Jan, K.; Sahu, J.K.; Habib, M.; Jan, S.; Bashir, K. A Comprehensive Review on Recent Trends and Utilization of Algal β-Glucan for the Development of Nutraceuticals and Functional Foods. Food Rev. Int. 2025, 41, 469–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, E.J.; Rezoagli, E.; Collins, C.; Saha, S.K.; Major, I.; Murray, P. Sustainable Production and Pharmaceutical Applications of β-Glucan from Microbial Sources. Microbiol. Res. 2023, 274, 127424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, T.; Eapen, M.S.; Ishaq, M.; Park, A.Y.; Karpiniec, S.S.; Stringer, D.N.; Sohal, S.S.; Fitton, J.H.; Guven, N.; Caruso, V.; et al. Anti-Inflammatory Activity of Fucoidan Extracts in Vitro. Mar. Drugs 2021, 19, 702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yao, M.; Guo, X.; Shao, X.; Wei, Y.; Zhang, X.; Wang, H.; Xu, F. Soluble Dietary Fiber from Prunus Persica Dregs Alleviates Gut Microbiota Dysfunction through Lead Excretion. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2023, 175, 113725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gotteland, M.; Riveros, K.; Gasaly, N.; Carcamo, C.; Magne, F.; Liabeuf, G.; Beattie, A.; Rosenfeld, S. The Pros and Cons of Using Algal Polysaccharides as Prebiotics. Front. Nutr. 2020, 7, 163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pramanik, S.; Singh, A.; Abualsoud, B.M.; Deepak, A.; Nainwal, P.; Sargsyan, A.S.; Bellucci, S. From Algae to Advancements: Laminarin in Biomedicine. RSC Adv. 2024, 14, 3209–3231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karuppusamy, S.; Rajauria, G.; Fitzpatrick, S.; Lyons, H.; McMahon, H.; Curtin, J.; Tiwari, B.K.; O’Donnell, C. Biological Properties and Health-Promoting Functions of Laminarin: A Comprehensive Review of Preclinical and Clinical Studies. Mar. Drugs 2022, 20, 772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalasariya, H.S.; Yadav, V.K.; Yadav, K.K.; Tirth, V.; Algahtani, A.; Islam, S.; Gupta, N.; Jeon, B.H. Seaweed-Based Molecules and Their Potential Biological Activities: An Eco-Sustainable Cosmetics. Molecules 2021, 26, 5313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, H.; Long, Z.; Ma, J.; Kong, L.; Lin, H.; Zhou, S.; Lin, Y.; Huang, Z.; Liu, L.; Li, Z. Growth Performance, Digestive Capacity and Intestinal Health of Juvenile Spotted Seabass (Lateolabrax maculatus) Fed Dietary Laminarin Supplement. Front. Mar. Sci. 2023, 10, 1242175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bi, D.; Yang, X.; Yao, L.; Hu, Z.; Li, H.; Xu, X.; Lu, J. Potential Food and Nutraceutical Applications of Alginate: A Review. Mar. Drugs 2022, 20, 564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abka-khajouei, R.; Tounsi, L.; Shahabi, N.; Patel, A.K.; Abdelkafi, S.; Michaud, P. Structures, Properties and Applications of Alginates. Mar. Drugs 2022, 20, 364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pournaki, S.K.; Aleman, R.S.; Hasani-Azhdari, M.; Marcia, J.; Yadav, A.; Moncada, M. Current Review: Alginate in the Food Applications. J—Multidiscip. Sci. J. 2024, 7, 281–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilcox, M.D.; Chater, P.I.; Stanforth, K.J.; Woodcock, A.D.; Dettmar, P.W.; Pearson, J.P. The Rheological Properties of an Alginate Satiety Formulation in a Physiologically Relevant Human Model Gut System. Ann. Esophagus 2022, 5, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Lu, X.; Fang, F.; Wu, K.; Wu, J.; Gao, J. Comparison of the In-Vitro Effect of Five Prebiotics with Different Structure on Gut Microbiome and Metabolome. Food Biosci. 2025, 64, 103810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puscaselu, R.G.; Lobiuc, A.; Dimian, M.; Covasa, M. Alginate: From Food Industry to Biomedical Applications and Management of Metabolic Disorders. Polymers 2020, 12, 2417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharfi, L.; Nowroozi, M.R.; Smirnova, G.; Fedotova, A.; Babarkin, D.; Mirshafiey, A. The Safety Properties of Sodium Alginate and Its Derivatives. J. Biomed. Eng. Med. Imaging 2024, 11, 16126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Hourcade, M.; del Campo, E.M.; Braga, M.R.; Salgado, A.; Casano, L.M. Disentangling the Role of Extracellular Polysaccharides in Desiccation Tolerance in Lichen-Forming Microalgae. First Evidence of Sulfated Polysaccharides and Ancient Sulfotransferase Genes. Envrion. Microbiol. 2020, 22, 3096–3111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kronusová, O.; Kaštánek, P.; Koyun, G.; Kaštánek, F.; Brányik, T. Factors Influencing the Production of Extracellular Polysaccharides by the Green Algae Dictyosphaerium Chlorelloides and Their Isolation, Purification, and Composition. Microorganisms 2022, 10, 1473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babiak, W.; Krzemińska, I. Extracellular Polymeric Substances (EPS) as Microalgal Bioproducts: A Review of Factors Affecting EPS Synthesis and Application in Flocculation Processes. Energies 2021, 14, 4007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sasaki, M.; Takagi, A.; Sasaki, D.; Nakamura, A.; Asayama, M. Characteristics and Function of an Extracellular Polysaccharide from a Green Alga Parachlorella. Carbohydr. Polym. 2021, 254, 117252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, R.; Zheng, Y. Overview of Microalgal Extracellular Polymeric Substances (EPS) and Their Applications. Biotechnol. Adv. 2016, 34, 1225–1244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyrslova, I.; Krausova, G.; Smolova, J.; Stankova, B.; Branyik, T.; Malinska, H.; Huttl, M.; Kana, A.; Doskocil, I.; Curda, L. Prebiotic and Immunomodulatory Properties of the Microalga Chlorella Vulgaris and Its Synergistic Triglyceride-Lowering Effect with Bifidobacteria. Fermentation 2021, 7, 125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Z.F.; Lee, Y.Y. The Role of the Gut Microbiota in Health, Diet, and Disease with a Focus on Obesity. Foods 2025, 14, 492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarita, B.; Samadhan, D.; Hassan, M.Z.; Kovaleva, E.G. A Comprehensive Review of Probiotics and Human Health-Current Prospective and Applications. Front. Microbiol. 2024, 15, 1487641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gasaly, N.; Hermoso, M.A.; Gotteland, M. Butyrate and the Fine-Tuning of Colonic Homeostasis: Implication for Inflammatory Bowel Diseases. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 3061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, N.J.; Yu, S.; Kim, D.H.; Yun, E.J.; Kim, K.H. Characterization of BpGH16A of Bacteroides Plebeius, a Key Enzyme Initiating the Depolymerization of Agarose in the Human Gut. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2021, 105, 617–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Shang, Q.; Li, G.; Wang, X.; Yu, G. Degradation of Marine Algae-Derived Carbohydrates by Bacteroidetes Isolated from Human Gut Microbiota. Mar. Drugs 2017, 15, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Konasani, V.R.; Jin, C.; Karlsson, N.G.; Albers, E. A Novel Ulvan Lyase Family with Broad-Spectrum Activity from the Ulvan Utilisation Loci of Formosa Agariphila KMM 3901. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 14713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mathieu, S.; Touvrey-Loiodice, M.; Poulet, L.; Drouillard, S.; Vincentelli, R.; Henrissat, B.; Skjak-Bræk, G.; Helbert, W. Ancient Acquisition of “Alginate Utilization Loci” by Human Gut Microbiota. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 8075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salyers, A.A.; Palmer, J.K.; Wilkins, T.D. Laminarinase (P8-Glucanase) Activity InBacteroides from the Human Colon. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1977, 33, 1118–1124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlatterer, K.; Peschel, A.; Kretschmer, D. Short-Chain Fatty Acid and FFAR2 Activation—A New Option for Treating Infections? Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2021, 11, 785833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Linde, C.; Barone, M.; Turroni, S.; Brigidi, P.; Keleszade, E.; Swann, J.R.; Costabile, A. An in Vitro Pilot Fermentation Study on the Impact of Chlorella pyrenoidosa on Gut Microbiome Composition and Metabolites in Healthy and Coeliac Subjects. Molecules 2021, 26, 2330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, M.; Quan, M.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, A.; Gao, P.; Shang, Q.; Yu, G. In Vitro Fermentation of Polysaccharide from Edible Alga Enteromorpha Clathrata by the Gut Microbiota of Patients with Ulcerative Colitis. Nutrients 2023, 15, 4122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, J.; Zhao, Y.; Zhou, C.; Zhao, Q.; Zhong, H.; Zhu, X.; Fu, T.; Pan, L.; Shang, Q.; Yu, G. Dietary Polysaccharide from Enteromorpha Clathrata Attenuates Obesity and Increases the Intestinal Abundance of Butyrate-Producing Bacterium, Eubacterium xylanophilum, in Mice Fed a High-Fat Diet. Polymers 2021, 13, 3286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patel, A.K.; Singhania, R.R.; Awasthi, M.K.; Varjani, S.; Bhatia, S.K.; Tsai, M.L.; Hsieh, S.L.; Chen, C.W.; Dong, C.D. Emerging Prospects of Macro- and Microalgae as Prebiotic. Microb. Cell Fact. 2021, 20, 112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Terada, A.; Hara, H.; Mitsuoka, T. Effect of Dietary Alginate on the Faecal Microbiota and Faecal Metabolic Activity in Humans. Microb. Ecol. Health Dis. 1995, 8, 259–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, S.; Chen, H.; Zhu, L.; Liu, W.; Yu, H.D.; Wang, X.; Yin, Y. Comparative Study on the in Vitro Effects of Pseudomonas Aeruginosa and Seaweed Alginates on Human Gut Microbiota. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0171576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ai, C.; Jiang, P.; Liu, Y.; Duan, M.; Sun, X.; Luo, T.; Jiang, G.; Song, S. The Specific Use of Alginate from: Laminaria Japonica by Bacteroides Species Determined Its Modulation of the Bacteroides Community. Food Funct. 2019, 10, 4304–4314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sweeney, T.; Meredith, H.; Vigors, S.; McDonnell, M.J.; Ryan, M.; Thornton, K.; O’Doherty, J.V. Extracts of Laminarin and Laminarin/Fucoidan from the Marine Macroalgal Species Laminaria Digitata Improved Growth Rate and Intestinal Structure in Young Chicks, but Does Not Influence Campylobacter Jejuni Colonisation. Anim. Feed Sci. Technol. 2017, 232, 71–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yun, E.J.; Yu, S.; Kim, Y.A.; Liu, J.J.; Kang, N.J.; Jin, Y.S.; Kim, K.H. In Vitro Prebiotic and Anti-Colon Cancer Activities of Agar-Derived Sugars from Red Seaweeds. Mar. Drugs 2021, 19, 213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malairaj, S.; Veeraperumal, S.; Yao, W.; Subramanian, M.; Tan, K.; Zhong, S.; Cheong, K.L. Porphyran from Porphyra Haitanensis Enhances Intestinal Barrier Function and Regulates Gut Microbiota Composition. Mar. Drugs 2023, 21, 265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Y.; Yu, W.; Wang, H.; Yao, L.; He, Z.; Sun, M.; Feng, T.; Yu, C.; Yue, H. Flash Extraction of Ulvan Polysaccharides from Marine Green Macroalga Ulva Linza and Evaluation of Its Antioxidant and Gut Microbiota Modulation Activities. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 262, 130174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Wu, X.; Yuan, H.; Huang, S.; Park, S. Mitigation of Memory Impairment with Fermented Fucoidan and λ-Carrageenan Supplementation through Modulating the Gut Microbiota and Their Metagenome Function in Hippocampal Amyloid-β Infused Rats. Cells 2022, 11, 2301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, G.; Harada, M.; Midorikawa, Y.; Yamamoto, M.; Nakamura, A.; Takahashi, H.; Kuda, T. Effects of Alginate and Laminaran on the Microbiota and Antioxidant Properties of Human Faecal Cultures. Food Biosci. 2022, 47, 101763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, K.; Yuan, Q.; Li, H.; Li, T.; Ma, H.; Gao, C.; Zhang, S.; Liu, Y.; Zhao, L. Chlorella pyrenoidosa Polysaccharides as a Prebiotic to Modulate Gut Microbiota: Physicochemical Properties and Fermentation Characteristics In Vitro. Foods 2022, 11, 725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seong, H.; Bae, J.H.; Seo, J.S.; Kim, S.A.; Kim, T.J.; Han, N.S. Comparative Analysis of Prebiotic Effects of Seaweed Polysaccharides Laminaran, Porphyran, and Ulvan Using in Vitro Human Fecal Fermentation. J. Funct. Foods 2019, 57, 408–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Li, G.; Shang, Q.; Chen, X.; Liu, W.; Pi, X.; Zhu, L.; Yin, Y.; Yu, G.; Wang, X. In Vitro Fermentation of Alginate and Its Derivatives by Human Gut Microbiota. Anaerobe 2016, 39, 19–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Healy, L.E.; Zhu, X.; Pojić, M.; Sullivan, C.; Tiwari, U.; Curtin, J.; Tiwari, B.K. Biomolecules from Macroalgae—Nutritional Profile and Bioactives for Novel Food Product Development. Biomolecules 2023, 13, 386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez-Santamarina, A.; Miranda, J.M.; Del Carmen Mondragon, A.; Lamas, A.; Cardelle-Cobas, A.; Franco, C.M.; Cepeda, A. Potential Use of Marine Seaweeds as Prebiotics: A Review. Molecules 2020, 25, 1004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rehman, S.; Gora, A.H.; Abdelhafiz, Y.; Dias, J.; Pierre, R.; Meynen, K.; Fernandes, J.M.O.; Sørensen, M.; Brugman, S.; Kiron, V. Potential of Algae-Derived Alginate Oligosaccharides and β-Glucan to Counter Inflammation in Adult Zebrafish Intestine. Front. Immunol. 2023, 14, 1183701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guehaz, K.; Boual, Z.; Telli, A.; Meskher, H.; Belkhalfa, H.; Pierre, G.; Michaud, P.; Adessi, A. A Sulfated Exopolysaccharide Derived from Chlorella Sp. Exhibiting in Vitro Anti-α-d-Glucosidase Activity. Arch. Microbiol. 2024, 206, 218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Oh, J.Y.; Hwang, J.; Ko, J.Y.; Jeon, Y.J.; Ryu, B. In Vitro and in Vivo Antioxidant Activities of Polysaccharides Isolated from Celluclast-Assisted Extract of an Edible Brown Seaweed, Sargassum Fulvellum. Antioxidants 2019, 8, 493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.N.; Li, T.; Li, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Wu, H.L.; Xiang, W.Z.; Li, A.F. Exopolysaccharides from the Energy Microalga Strain Botryococcus Braunii: Purification, Characterization, and Antioxidant Activity. Foods 2022, 11, 110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, Y.; Shin, H.; Lee, M.K.; Kwon, O.S.; Shin, J.S.; Kim, Y.-I.; Kim, C.W.; Lee, H.R.; Kim, M. Antiviral Activity of Lambda-Carrageenan against Influenza Viruses and Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Varese, A.; Paletta, A.; Ceballos, A.; Palacios, C.A.; Figueroa, J.M.; Dugour, A.V. Iota-Carrageenan Prevents the Replication of SARS-CoV-2 in a Human Respiratory Epithelium Cell Line in Vitro. Front. Virol. 2021, 1, 746824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jun, J.Y.; Jung, M.J.; Jeong, I.H.; Yamazaki, K.; Kawai, Y.; Kim, B.M. Antimicrobial and Antibiofilm Activities of Sulfated Polysaccharides from Marine Algae against Dental Plaque Bacteria. Mar. Drugs 2018, 16, 301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toshkova-Yotova, T.; Sulikovska, I.; Djeliova, V.; Petrova, Z.; Ognyanov, M.; Denev, P.; Toshkova, R.; Georgieva, A. Exopolysaccharides from the Green Microalga Strain Coelastrella Sp. BGV—Isolation, Characterization, and Assessment of Anticancer Potential. Curr. Issues Mol. Biol. 2024, 46, 10312–10334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yue, Q.; Liu, Y.; Li, F.; Hong, T.; Guo, S.; Cai, M.; Zhao, L.; Su, L.; Zhang, S.; Zhao, C.; et al. Antioxidant and Anticancer Properties of Fucoidan Isolated from Saccharina Japonica Brown Algae. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 8962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mak, W.; Wang, S.K.; Liu, T.; Hamid, N.; Li, Y.; Lu, J.; White, W.L. Anti-Proliferation Potential and Content of Fucoidan Extracted from Sporophyll of New Zealand Undaria pinnatifida. Front. Nutr. 2014, 1, 00009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carvalhal, F.; Cristelo, R.R.; Resende, D.I.S.P.; Pinto, M.M.M.; Sousa, E.; Correia-Da-Silva, M. Antithrombotics from the Sea: Polysaccharides and Beyond. Mar. Drugs 2019, 17, 170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faggio, C.; Pagano, M.; Dottore, A.; Genovese, G.; Morabito, M. Evaluation of Anticoagulant Activity of Two Algal Polysaccharides. Nat. Prod. Res. 2016, 30, 1934–1937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, L.; Yang, Y.; Mao, W. Anticoagulant Property of a Sulfated Polysaccharide with Unique Structural Characteristics from the Green Alga Chaetomorpha Aerea. Mar. Drugs 2023, 21, 88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pomin, V.H.; Mahdi, F.; Jin, W.; Zhang, F.; Linhardt, R.J.; Paris, J.J. Red Algal Sulfated Galactan Binds and Protects Neural Cells from Hiv-1 Gp120 and Tat. Pharmaceuticals 2021, 14, 714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Usoltseva, R.V.; Shevchenko, N.M.; Silchenko, A.S.; Anastyuk, S.D.; Zvyagintsev, N.V.; Ermakova, S.P. Determination of the Structure and in Vitro Anticancer Activity of Fucan from Saccharina Dentigera and Its Derivatives. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2022, 206, 614–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perveen, S.; Yang, L.; Zhou, S.; Feng, B.; Xie, X.; Zhou, Q.; Qian, D.; Wang, C.; Yin, F. β-1,3-Glucan from Euglena Gracilis as an Immunostimulant Mediates the Antiparasitic Effect against Mesanophrys Sp. on Hemocytes in Marine Swimming Crab (Portunus trituberculatus). Fish. Shellfish. Immunol. 2021, 114, 28–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krylova, N.V.; Ermakova, S.P.; Lavrov, V.F.; Leneva, I.A.; Kompanets, G.G.; Iunikhina, O.V.; Nosik, M.N.; Ebralidze, L.K.; Falynskova, I.N.; Silchenko, A.S.; et al. The Comparative Analysis of Antiviral Activity of Native and Modified Fucoidans from Brown Algae Fucus Evanescens in Vitro and in Vivo. Mar. Drugs 2020, 18, 224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, Y.; Cho, E.J.; Lee, J.H.; Yu, S.J.; Kim, Y.J.; Kim, C.Y.; Yoon, J.H. Fucoidan-Induced ID-1 Suppression Inhibits the in Vitro and in Vivo Invasion of Hepatocellular Carcinoma Cells. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2016, 83, 607–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vo, T.P.; Nguyen, D.Q.; Thi Ho, T.A.; Nguyen, T.M.; Huy Ha, N.M.; Vo, P.H.N. Novel Extraction of Bioactive Compounds from Algae Using Green Solvent: Principles, Applications, and Future Perspectives. J. Agric. Food Res. 2024, 18, 101535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, S.Y.; Huang, X.; Cheong, K.L. Recent Advances in Marine Algae Polysaccharides: Isolation, Structure, and Activities. Mar. Drugs 2017, 15, 388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jönsson, M.; Allahgholi, L.; Sardari, R.R.R.; Hreggviosson, G.O.; Karlsson, E.N. Extraction and Modification of Macroalgal Polysaccharides for Current and Next-Generation Applications. Molecules 2020, 25, 930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobrinčić, A.; Balbino, S.; Zorić, Z.; Pedisić, S.; Kovačević, D.B.; Garofulić, I.E.; Dragović-Uzelac, V. Advanced Technologies for the Extraction of Marine Brown Algal Polysaccharides. Mar. Drugs 2020, 18, 168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Chen, L.; Shang, N.; Wu, K.; Liao, W. Recent Advances in the Structure, Extraction, and Biological Activity of Sargassum Fusiforme Polysaccharides. Mar. Drugs 2025, 23, 98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, J.A.V.; Lucas, B.F.; Alvarenga, A.G.P.; Moreira, J.B.; de Morais, M.G. Microalgae Polysaccharides: An Overview of Production, Characterization, and Potential Applications. Polysaccharides 2021, 2, 759–772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juneja, A.; Ceballos, R.M.; Murthy, G.S. Effects of Environmental Factors and Nutrient Availability on the Biochemical Composition of Algae for Biofuels Production: A Review. Energies 2013, 6, 4607–4638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laroche, C. Exopolysaccharides from Microalgae and Cyanobacteria: Diversity of Strains, Production Strategies, and Applications. Mar. Drugs 2022, 20, 336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, X.; Nan, F.; Feng, J.; Lv, J.; Liu, Q.; Liu, X.; Xie, S. Effects of Different Environmental Factors on the Growth and Bioactive Substance Accumulation of Porphyridium Purpureum. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 2221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wongsnansilp, T.; Khamcharoen, M. The Effects of Red–Blue Light on the Growth and Astaxanthin Production of a Haematococcus pluvialis Strain Isolated from Southern Thailand. Appl. Microbiol. 2024, 4, 1745–1756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blifernez-Klassen, O.; Chaudhari, S.; Klassen, V.; Wördenweber, R.; Steffens, T.; Cholewa, D.; Niehaus, K.; Kalinowski, J.; Kruse, O. Metabolic Survey of Botryococcus Braunii: Impact of the Physiological State on Product Formation. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0198976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nazloo, E.K.; Danesh, M.; Sarrafzadeh, M.H.; Moheimani, N.R.; Ennaceri, H. Biomass and Hydrocarbon Production from Botryococcus Braunii: A Review Focusing on Cultivation Methods. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 926, 171734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chemat, F.; Vian, M.A.; Cravotto, G. Green Extraction of Natural Products: Concept and Principles. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2012, 13, 8615–8627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stirk, W.A.; Bálint, P.; Vambe, M.; Lovász, C.; Molnár, Z.; van Staden, J.; Ördög, V. Effect of Cell Disruption Methods on the Extraction of Bioactive Metabolites from Microalgal Biomass. J. Biotechnol. 2020, 307, 35–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Temnov, M.; Ustinskaya, Y.; Meronyuk, K.; Dvoretsky, D. A Study of Complex Cell Disruption Methods of Intracellular Water-Soluble Protein Extraction from Chlorella Sorokiniana. Ind. Biotechnol. 2023, 19, 145–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishnan, L.; Ravi, N.; Kumar Mondal, A.; Akter, F.; Kumar, M.; Ralph, P.; Kuzhiumparambil, U. Seaweed-Based Polysaccharides—Review of Extraction, Characterization, and Bioplastic Application. Green Chem. 2024, 26, 5790–5823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lomartire, S.; Gonçalves, A.M.M. Novel Technologies for Seaweed Polysaccharides Extraction and Their Use in Food with Therapeutically Applications—A Review. Foods 2022, 11, 2654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Li, J.; Lu, F.; Liu, F. Ultrasound-Assisted Multi-Enzyme Extraction for Highly Efficient Extraction of Polysaccharides from Ulva Lactuca. Foods 2024, 13, 891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobrinčić, A.; Pedisić, S.; Zorić, Z.; Jurin, M.; Roje, M.; Čož-Rakovac, R.; Dragović-Uzelac, V. Microwave Assisted Extraction and Pressurized Liquid Extraction of Sulfated Polysaccharides from Fucus Virsoides and Cystoseira barbata. Foods 2021, 10, 1481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdul Khalil, H.P.S.; Lai, T.K.; Tye, Y.Y.; Rizal, S.; Chong, E.W.N.; Yap, S.W.; Hamzah, A.A.; Nurul Fazita, M.R.; Paridah, M.T. A Review of Extractions of Seaweed Hydrocolloids: Properties and Applications. Express Polym. Lett. 2018, 12, 296–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cameselle, C.; Maietta, I.; Torres, M.D.; Simón-Vázquez, R.; Domínguez, H. Optimization of Ultrasound-Assisted Extraction of Bioactive Compounds and Biopolymers from Ulva Spp. Using Response Surface Methodology. J. Appl. Phycol. 2025, 37, 2031–2050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chica, L.R.; Yamashita, C.; Nunes, N.S.S.; Negreiros, A.T.; Moraes, I.C.F.; Ferreira, A.G.; Mayer, C.R.M.; Haminiuk, C.W.I.; Branco, C.C.Z.; Branco, I.G. Optimizing Alginate Extraction Using Box-Behnken Design: Improving Yield and Antioxidant Properties through Ultrasound-Assisted Citric Acid Extraction. Food Chem. Adv. 2024, 5, 100813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Sheekh, M.; Kassem, W.M.A.; Alwaleed, E.A.; Saber, H. Optimization and Characterization of Brown Seaweed Alginate for Antioxidant, Anticancer, Antimicrobial, and Antiviral Properties. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 278, 134715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savić Gajić, I.M.; Savić, I.M.; Ivanovska, A.M.; Vunduk, J.D.; Mihalj, I.S.; Svirčev, Z.B. Improvement of Alginate Extraction from Brown Seaweed (Laminaria digitata L.) and Valorization of Its Remaining Ethanolic Fraction. Mar. Drugs 2024, 22, 280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malvis Romero, A.; Picado Morales, J.J.; Klose, L.; Liese, A. Enzyme-Assisted Extraction of Ulvan from the Green Macroalgae Ulva Fenestrata. Molecules 2023, 28, 6781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yaich, H.; Garna, H.; Besbes, S.; Paquot, M.; Blecker, C.; Attia, H. Effect of Extraction Conditions on the Yield and Purity of Ulvan Extracted from Ulva Lactuca. Food Hydrocoll. 2013, 31, 375–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, X.; Zhong, W. Antihyperglycemic and Antihyperlipidemic Effects of Low-Molecular-Weight Carrageenan in Rats. Open Life Sci. 2018, 13, 379–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tukenmez Emre, U.; Sirin, S.; Nigdelioglu Dolanbay, S.; Aslim, B. Harnessing Polysaccharides for Sustainable Food Packaging. Polym. Bull. 2025, 82, 2779–2825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koh, H.S.A.; Lim, S.E.V.; Lu, J.; Zhou, W. Bioactivity Enhancement of Fucoidan through Complexing with Bread Matrix and Baking. LWT 2020, 130, 109646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Z.; Ou, Y.; Lan, X.; Tang, J.; Zheng, B. Effects of Laminarin on the Structural Properties and in Vitro Digestion of Wheat Starch and Its Application in Noodles. LWT 2023, 178, 114543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Meng, L.; Gao, C.; Cheng, W.; Yang, Y.; Shen, X.; Tang, X. Construction of Starch-Sodium Alginate Interpenetrating Polymer Network and Its Effects on Structure, Cooking Quality and in Vitro Starch Digestibility of Extruded Whole Buckwheat Noodles. Food Hydrocoll. 2023, 143, 108876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashem, M.; Begum, M.; Hasan, M.; Al Noman, M.; Islam, S.; Ali, M. Effect of Sodium Alginate on the Quality of Chicken Sausages. Meat Res. 2022, 2, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balasubramanian, B.; Sinurat, E.; Shi, B.; Yin, F.; Yu, H.; Gan, S. The Effects of Fucoidan as a Dairy Substitute on Diarrhea Rate and Intestinal Barrier Function of the Large Intestine in Weaned Lambs. Front. Vet. Sci. 2022, 9, 1007346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, R.T.; Bhuiya, S.; Anil, A.; Logheeswaran, J.; Prathiviraj, R.; Selvin, J.; Kiran, G.S. Fucoidan Prebiotic from the Seaweed Sargassum christaefolium and Its Effects on the Sensorial, Textural and Rheological Properties of Yogurt. Food Biosci. 2025, 71, 107159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saeed, M.; Khanam, R.; Hafeez, H.; Ahmad, Z.; Saleem, S.; Tariq, M.R.; Safdar, W.; Waseem, M.; Ali, U.; Azam, M.; et al. Viability of Free and Alginate-Carrageenan Gum Coated Lactobacillus acidophilus and Lacticaseibacillus casei in Functional Cottage Cheese. ACS Omega 2024, 9, 13840–13851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mihaly Cozmuta, A.; Jastrzębska, A.; Apjok, R.; Petrus, M.; Mihaly Cozmuta, L.; Peter, A.; Nicula, C. Immobilization of Baker’s Yeast in the Alginate-Based Hydrogels to Impart Sensorial Characteristics to Frozen Dough Bread. Food Biosci. 2021, 42, 101143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alboofetileh, M.; Jeddi, S.; Mohammadzadeh, B.; Noghani, F.; Kamali, S. Exploring the Impact of Enzyme-Extracted Ulvan from Ulva Rigida on Quality Characteristics and Oxidative Stability of Beef Sausage during Refrigerated Storage. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2024, 62, 2120–2131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borges, D.M.; Ribeiro, S.C.; Silva, S.P.M.; Silva, C.C.G. Dried Algae as Potential Functional Ingredient in Fresh Cheese. Food Bioeng. 2024, 3, 65–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Y.; Liang, X.; Zhang, J.; Kong, B.; Shi, P.; Cao, C.; Zhang, H.; Liu, Q.; Zhang, Y. Effects of Transglutaminase Coupled with κ-Carrageenan on the Rheological Behaviours, Gel Properties and Microstructures of Meat Batters. Food Hydrocoll. 2024, 146, 109265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Mascaraque, L.G.; Chambon, V.; Trifkovic, K.; Brodkorb, A. Alginate Microcapsules Produced by External Gelation in Milk with Application in Dairy Products. Food Struct. 2023, 37, 100339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, S.P.M.; Ribeiro, S.C.; Teixeira, J.A.; Silva, C.C.G. Application of an Alginate-Based Edible Coating with Bacteriocin-Producing Lactococcus Strains in Fresh Cheese Preservation. LWT 2022, 153, 112486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, M.M.; Pestana, J.M.; Osório, D.; Alfaia, C.M.; Martins, C.F.; Mourato, M.; Gueifão, S.; Rego, A.M.; Coelho, I.; Coelho, D.; et al. Effect of Dietary Laminaria Digitata with Carbohydrases on Broiler Production Performance and Meat Quality, Lipid Profile, and Mineral Composition. Animals 2022, 12, 1007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasan, K.; Islam, R.; Hasan, M.; Sarker, S.H.; Biswas, M.H. Effect of Alginate Edible Coatings Enriched with Black Cumin Extract for Improving Postharvest Quality Characteristics of Guava (Psidium guajava L.) Fruit. Food Bioproc. Techol. 2022, 15, 2050–2064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, M.; Theng, A.H.P.; Yang, D.; Yang, H. Influence of κ-Carrageenan on the Rheological Behaviour of a Model Cake Flour System. LWT 2021, 136, 110324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Öztürk-Kerimoğlu, B. A Promising Strategy for Designing Reduced-Fat Model Meat Emulsions by Utilization of Pea Protein-Agar Agar Gel Complex. Food Struct. 2021, 29, 100205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Contessa, C.R.; de Souza, N.B.; Gonçalo, G.B.; de Moura, C.M.; da Rosa, G.S.; Moraes, C.C. Development of Active Packaging Based on Agar-Agar Incorporated with Bacteriocin of Lactobacillus sakei. Biomolecules 2021, 11, 1869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shalaby M, S.; Amin H, H. Potential Using of Ulvan Polysaccharide from Ulva Lactuca as a Prebiotic in Synbiotic Yogurt Production. J. Probiotics Health 2019, 07, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lourenço, S.C.; Fraqueza, M.J.; Fernandes, M.H.; Moldão-Martins, M.; Alves, V.D. Application of Edible Alginate Films with Pineapple Peel Active Compounds on Beef Meat Preservation. Antioxidants 2020, 9, 667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, H.; Kim, J.; Lee, C. Continuous Anaerobic Co-Digestion of Ulva Biomass and Cheese Whey at Varying Substrate Mixing Ratios: Different Responses in Two Reactors with Different Operating Regimes. Bioresour. Technol. 2016, 221, 366–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- E.I.D. Parry (India) Limited Parry Nutraceuticals Division “Dare House”. GRAS Notice 000391: Spirulina (Anthrospira Platensis). Available online: https://hfpappexternal.fda.gov/scripts/fdcc/index.cfm?set=GrASNotices&id=391 (accessed on 12 November 2025).

- Nikken Sohonsha Corporation. GRAS Notice 000351: Dunaliella Bardawil Alga. Available online: https://hfpappexternal.fda.gov/scripts/fdcc/index.cfm?set=GrASNotices&id=351 (accessed on 12 November 2025).

- Solazyme Inc. GRAS Notice 000519: Chlorella Protothecoides Strain S106 Flour with 40-75% Protein. Available online: https://www.fda.gov/files/food/published/GRAS-Notice-000673---Algal-fat-derived-from-Prototheca-moriformis-%28S7737%29.pdf (accessed on 12 November 2025).

- Sá Monteiro, M.; Sloth, J.; Holdt, S.; Hansen, M. Analysis and Risk Assessment of Seaweed. EFSA J. 2019, 17, e170915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lähteenmäki-Uutela, A.; Rahikainen, M.; Camarena-Gómez, M.T.; Piiparinen, J.; Spilling, K.; Yang, B. European Union Legislation on Macroalgae Products. Aquac. Int. 2021, 29, 487–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novel-Food_consult-Status_Chlorella-Sp. Available online: https://food.ec.europa.eu/food-safety/novel-food/consultation-process-novel-food-status_en (accessed on 12 November 2025).

- Turck, D.; Castenmiller, J.; De Henauw, S.; Hirsch-Ernst, K.I.; Kearney, J.; Maciuk, A.; Mangelsdorf, I.; McArdle, H.J.; Naska, A.; Pelaez, C.; et al. Safety of Schizochytrium Sp. Oil as a Novel Food Pursuant to Regulation (EU) 2015/2283. EFSA J. 2020, 18, 6242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turck, D.; Cámara, M.; Bohn, T.; Castenmiller, J.; De Henauw, S.; Jos, Á.; Maciuk, A.; Mangelsdorf, I.; McNulty, B.; Naska, A.; et al. Safety of Dried Biomass Powder of Chlamydomonas Reinhardtii THN 6 as a Novel Food Pursuant to Regulation (EU) 2015/2283. EFSA J. 2025, 23, 9413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castillo, A.; Finimundy, T.C.; Heleno, S.A.; Rodrigues, P.; Fernandes, F.A.; Pereira, S.; Lores, M.; Barros, L.; Garcia-Jares, C. The Generally Recognized as Safe (GRAS) Microalgae Haematococcus pluvialis (Wet) as a Multifunctional Additive for Coloring and Improving the Organoleptic and Functional Properties of Foods. Food Funct. 2023, 14, 6023–6035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Algae as Novel Food in Europe. Available online: https://www.eaba-association.org/en (accessed on 12 November 2025).

- Novel-Food_authorisation_2014_auth-Letter_tetraselmis_chuii_en. Available online: https://food.ec.europa.eu/document/download/31622960-726d-4542-88c8-a67954196109_en?filename=novel-food_authorisation_2014_auth-letter_tetraselmis_chuii_en.pdf (accessed on 12 November 2025).

- Mara Renewables Corporation. Sound Science. 2016. Available online: https://hfpappexternal.fda.gov/scripts/fdcc/index.cfm?set=GRASNotices&id=677 (accessed on 12 November 2025).

- Available online: https://www.jetro.go.jp/ext_images/en/reports/regulations/pdf/foodext2010e.pdf (accessed on 12 November 2025).

- Peng, J.; Min, S.; Qing, P.; Yang, M. The Impacts of Urbanization and Dietary Knowledge on Seaweed Consumption in China. Foods 2021, 10, 1373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Available online: https://algaeprobanos.eu/wp-content/uploads/2025/02/D3.5-Standardisation-guidelines.pdf (accessed on 12 November 2025).

- Araujo, R.; Peteiro, C. Algae as Food and Food Supplements in Europe; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2021; ISBN 9789276405481. [CrossRef]

- Cotas, J.; Pacheco, D.; Araujo, G.S.; Valado, A.; Critchley, A.T.; Pereira, L. On the Health Benefits vs. Risks of Seaweeds and Their Constituents: The Curious Case of the Polymer Paradigm. Mar. Drugs 2021, 19, 164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mackie, A.R.; Macierzanka, A.; Aarak, K.; Rigby, N.M.; Parker, R.; Channel, G.A.; Harding, S.E.; Bajka, B.H. Sodium Alginate Decreases the Permeability of Intestinal Mucus. Food Hydrocoll. 2016, 52, 749–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horibe, S.; Tanahashi, T.; Kawauchi, S.; Mizuno, S.; Rikitake, Y. Preventative Effects of Sodium Alginate on Indomethacin-Induced Small-Intestinal Injury in Mice. Int. J. Med. Sci. 2016, 13, 653–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Food Standards Agency. Regulated Products Safety Assessment Safety Assessment on Product E 401 (Sodium alginate) Used as a Surface Treatment in Entire Fruits and Vegetables (RP290) FSA Research and Evidence. J. Food Stand. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Younes, M.; Aggett, P.; Aguilar, F.; Crebelli, R.; Filipič, M.; Frutos, M.J.; Galtier, P.; Gott, D.; Gundert-Remy, U.; Kuhnle, G.G.; et al. Re-Evaluation of Carrageenan (E 407) and Processed Eucheuma Seaweed (E 407a) as Food Additives. EFSA J. 2018, 16, 5238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Title 21-Food and Drugs Chapter I-Food and Drug Administration, Department of Health and Human Services Subchapter B-Food for Human Consumption Part 172-Food Additives Permitted for Direct Addition to Food for Human Consumption Subpart G-Gums, Chewing Gum Bases and Related Substances. Available online: https://www.ecfr.gov/current/title-21/chapter-I/subchapter-B/part-172/subpart-G/section-172.620 (accessed on 12 November 2025).

- Title 21-Food and Drugs Chapter I-Food and Drug Administration, Department of Health and Human Services Subchapter B-Food for Human Consumption Part 184-Direct Food Substances Affirmed as Generally Recognized as Safe Subpart B-Listing of Specific Substances Affirmed as GRAS. Available online: https://www.ecfr.gov/current/title-21/chapter-I/subchapter-B/part-184/subpart-B/section-184.1724 (accessed on 12 November 2025).

- Available online: https://www.chinesestandard.net/PDF/BOOK.aspx/GB1886.176-2016 (accessed on 12 November 2025).

- Japanese Agricultural Standard Organic Processed Foods. Available online: https://www.maff.go.jp/e/policies/standard/specific/attach/pdf/organic_JAS-92.pdf (accessed on 12 November 2025).

| Polysaccharides | Method | Microbiota Changes | SCFA Production Changes | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fucoidan | in vitro fermentation | Bifidobacterium, Lactobacillus, Faecalibacterium, Prevotella, Megamonas increase Escherichia-Shigella, Klebsiella, Bilophila decrease | Acetate, propionate increase Butyrate, isobutyrate, valerate, isovalerate decrease *** | [18] |

| Ulvan | in vitro fermentation | Bacteroides, Parabacteroides, Faecalibacterium increase Prevotella, Blautia, Ruminococcus decrease | SCFA levels increase especially acetate, propionate, butyrate *** | [106] |

| Agar and derivatives | in vitro fermentation | Lactobacillus plantarum, L. acidophilus, L. casei increase Escherichia coli, Bacillus cereus decrease | An indirect increase in acetate, propionate, and butyrate levels is expected *** | [62] |

| Polysaccharides from Enteromorpha clathrate * | in vitro fermetation (ulcerative colitis fecal inocula). | Bacteroides thetaiotaomicron, B. ovatus, B. uniformis, Blautia spp., Parabacteroides spp. (anti-colitic) increase Escherichia-Shigella, Enterococcus decrease | Acetate levels increase Lactate levels decrease *** | [97] |

| Laminarin | in vivo (Juvenile spotted seabass) | Lactobacillus, Klebsiella, Proteobacteria increase Bacillus decreases | SCFA levels increase ** | [73] |

| Porphyran | in vivo (healthy mice) | Akkermansia, Rikenella, Coprococcus, Lachnospira, Roseburia increase Proteus, Shigella, Anaerofustis decrease | SCFA levels increase especially acetate and butyrate *** | [105] |

| Fucoidan and Kappa-Carraheenan | in vivo (rats showing Alzheimer symptoms) | Akkermansia muciniphila increase Peptostreptococcaceae decrease | Acetate 0.74\pm 0.02 mM Butyrate 0.17\pm 0.003 mM Total SCFA 1.22\pm 0.02 mM | [107] |

| Lambda Carrageenan | In vivo (rats showing Alzheimer symptoms) | Akkermensia muciniphila increse | Total SCFA 1.20\pm 0.02 mM Butyrate 0.17\pm 0.002 mM | [107] |

| Alginate | in vitro fermentation | Bacteroides xylanisolvens, Faecalibacterium, Prevotella copri increase (potentiallly) | Acetate levels increase *** | [108] |

| Laminarin | In vitro fermentation | Erysipelatoclostridium ramosum Bacteriodes uniformis, Roseburia faecis, Roseburia inulinivorans increase (potentially) | SCFA levels increase ** | [108] |

| Chlorella pyrenoidosa polysaccharides | in vitro digestion and fermentation | Parabacteroides distasonis (become dominant), Phascolarctobacterium faecium, Faecalibacterium prausnitzii increase Escherichia-Shigella, Fusobacterium, Klebsiella decrease | Total SCFA 36.076\pm 0.272 mM Acetate 18.968\pm 0.30 mM Propionate 9.617\pm 0.30 mM | [109] |

| Agar and derivatives | in vitro fermentation | Bifidobacterium longum ssp. infantis ATCC 15697, ATCC 17930, ATCC 15702, Bifidobacterium kashiwanohense DSM 21854 increase | SCFA levels increase especially acetate and lactate | [104] |

| Laminarin | in vitro fermentation | Bifidobacteria, Bacteriodes increase | Acetate 85.7 mM Propionate 28.7 mM | [110] |

| Ulvan | in vitro fermentation | Bifidobacteria, L. Actobacillus increase | Acetate 59.9 mM Lactate concentration dropped to 11.5 mM. | [110] |

| Alginate and derivatives | in vitro fermentation | Bacteroides ovatus, Bacteroides xylanisolvens, Bacteroides thetaiotaomicron increase | Total SCFA 78.6\pm 5.9 mM Acetate 41.3\pm 5.8 mM. Also propionate and butyrate levels increase *** | [111] |

| Method | Eco-Friendly | Algae | Polysaccharides | Yield | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ultrasound-Assisted Extraction (UAE) (1300 W 60 min) | Yes | Ulva spp. | Ulvan | 9.29 ± 0.47% | [152] |

| Ultrasound-Assisted Extraction (UAE) (176 W 15 min) | Yes | Sargassum spp. | Alginate | 54.20% | [153] |

| Enzyme-Assisted Extraction (EAE) (35.3% selulase + 34.5% pectinase + 30.2% alkaline protease) | Yes | Ulva lactuca | All polysaccharide content | 30.14% (optimum enzyme mixture) | [149] |

| Hot Water Extraction (HWE) (90 °C 4 h) | Yes | Ulva lactuca | All polysaccharide content | 6.43% | [149] |

| Enzyme-Assisted Extraction (EAE) (35.3% selulase + 34.5% pectinase + 30.2% alkaline protease) + Ultrasound-Assisted Extraction (UAE) (90 min) | Yes | Ulva lactuca | All polysaccharide content | 30.14% | [149] |

| Alkaline Extraction (2.5% Na2CO3) | No | P. pavonica, S. cinereum, D. dichotoma | Alginate | 21.13–24.08% | [154] |

| Ultrasound-Assisted Extraction (UAE) (150 W approximetely 30 min) | Yes | Laminaria digitata | Alginate | ~20–25% | [155] |

| Enzyme-Assisted Extraction (EAE) (Cellulysin 300 U/g) + Ultrasound-Assisted Extraction (UAE) (70 W 40 min9 | Yes | Ulva fenestrata | Ulvan | 17.9 ± 0.3% | [156] |

| Pressure Liquid Extraction (PLE) (103 bar 2 cycle 140 °C 15 min) | Yes | F. virsoides C. barbata | All polysaccharides content | F. virsoides 10.22 ± 0.03 C. barbata 11.77 ± 0.03 | [150] |

| Microwave-Assisted Extraction (MAE) (80 °C 10 min) | Yes | F. virsoides C. barbata | All polysaccharides content | F. virsoides 13.19% C. barbata 6.43% | [150] |

| Hot Water Extraction (HWE) 90 °C 3 h) | Yes | Ulva lactuca | Ulvan | 18.61% | [157] |

| Food Products | Algae/Polysaccharides | Optimal Concentration | Activity | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yogurt | Fucoidan from Sargassum christaefolium | 0.2 g/100 mL | t has increased prebiotic and antibacterial activity. | [165] |

| Fresh cheese | Fucus spiralis and Petalonia binghamiae polysaccharides * | 0.5 g/100 g | The weight loss of the cheeses was prevented, and the cheeses had a high antioxidant content. | [169] |

| Beef sausage | Ulvan from Ulva rigida | 0.5 g/100 g | It has significantly reduced the cooking loss of sausage and increased its moisture content. Ulvan has provided antioxidant activity. | [168] |

| Meat and mince mixtures, sausage | Kappa-Carrageenan ** | 0.2 g/100 g | The addition of kappa-carrageenan has improved quality of products. | [170] |

| Functional cottage cheese | Alginate ** Carrageenan ** | 1 g/100 g alginate 1 g/100 g carrageenan | Under simulated gastrointestinal conditions, coating with alginate-carrageenan gums increased the viability of probiotics. | [166] |

| Dairy products | Alginate ** | 1.5 g/100 mL | It has achieved microencapsulation of the contents by embedding a component in a micron-sized protective matrix. | [171] |

| Buckwheat noodle | Alginate from brown algae | 1 g/100 g | It reduced cooking loss, pGI and surface stickiness of noodles | [162] |

| Wheat starch and noodle | Laminarin from Laminaria | 6 g/100 g | It has strongly inhibted the in vitro digestibility of starch. Also, it improves the cooking textural properties of noodles. It reduces cooking loss and stickiness increase water absorption and firmness. | [161] |

| Chicken sausage | Alginate ** | 4 g/100 g | It reduced the values indicating lipid oxidation and cooking loss. It also extended shelf life by providing antioxidant activity and microbial balance. | [163] |

| Fresh cheese | Alginate ** | 2 g/100 mL | Alginate-based edible coatings containing Lactococcus strains that produce bacteriocins have been effective in reducing Listeria monocytogenes cells in fresh cheese. | [172] |

| Poultry meat | Alginate, fucose and other sulfated polysaccharides from Laminaria digitata | 15% l. digitata addition to the diet | The addition of 15% L. digitata to the diet increased the nutritional value and antioxidant pigments of poultry meat. | [173] |

| Guava fruits coating | Alginate ** | 2 g/100 mL | Alginate coating has been added to black cumin extract and has delayed guava’s respiration rate, weight loss, hardness loss, color change, and carotenoid formation. In addition, the fruit has increased vitamin C, total phenolic and flavonoid content, and antioxidant, antidiabetic activity. | [174] |

| Bakery products | Kappa-Carrageenan from Eucheuma | 10 g/100 g | The addition of kappa-carrageenan to the starch-gluten system increased viscosity and provided a more stable and firm structure. | [175] |

| Meat | Pea protein with Agar ** | 1.5 g/100 g | It has been integrated into meat emulsions, replacing the physical location of fat, thereby reducing the fat and energy content of the product while increasing emulsion stability, cooking efficiency, and nutritional value. | [176] |

| Curd cheese | Agar ** | n.d. | The agar-based active film significantly reduced the microbial load by reducing thermotolerant coliforms and coagulase-positive staphylococci. | [177] |

| Bread | Fucoidan from Undaria pinnatifida | 0.4 g/100 g | Specific bread volume increase, softer texture | [160] |

| Yogurt | Ulvan ** | 1 g/100 mL and 2 g/100 mL show similar activities | Lactobacillus acidophilus (LA-5) Streptococcus thermophilus (TH-4) Bifidobacterium sp. increase The consistency, viscosity, and hardness of the yogurt increase. | [178] |

| Bovine meat | Alginate from brown alga species ** | 1 g/100 ml | Alginate coatings have been used for active food packaging applications. When used with pineapple peel, it exhibits antimicrobial and antioxidant effects. | [179] |

| Whey | Ulva biomass * | 50–75 g/100 g | Biomethane has been produced through waste management. | [180] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Deniz, N.; Sarıtaş, S.; Bechelany, M.; Karav, S. Prebiotic and Functional Fibers from Micro- and Macroalgae: Gut Microbiota Modulation, Health Benefits, and Food Applications. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 11082. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262211082

Deniz N, Sarıtaş S, Bechelany M, Karav S. Prebiotic and Functional Fibers from Micro- and Macroalgae: Gut Microbiota Modulation, Health Benefits, and Food Applications. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2025; 26(22):11082. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262211082

Chicago/Turabian StyleDeniz, Nurdeniz, Sümeyye Sarıtaş, Mikhael Bechelany, and Sercan Karav. 2025. "Prebiotic and Functional Fibers from Micro- and Macroalgae: Gut Microbiota Modulation, Health Benefits, and Food Applications" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 26, no. 22: 11082. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262211082

APA StyleDeniz, N., Sarıtaş, S., Bechelany, M., & Karav, S. (2025). Prebiotic and Functional Fibers from Micro- and Macroalgae: Gut Microbiota Modulation, Health Benefits, and Food Applications. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 26(22), 11082. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262211082