Pregnenolone Bioproduction in Engineered Methylobacteria: Design and Elaboration

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

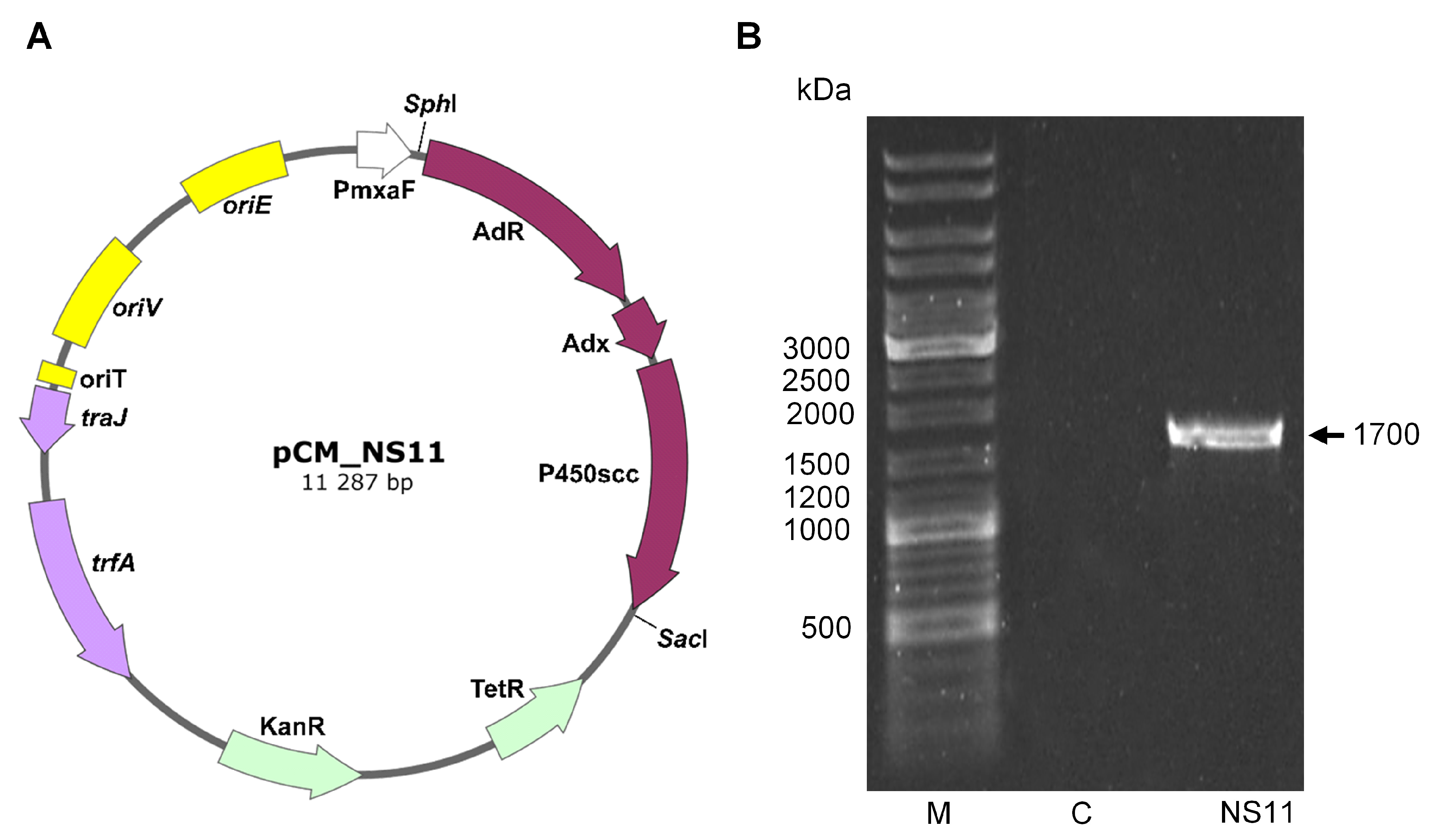

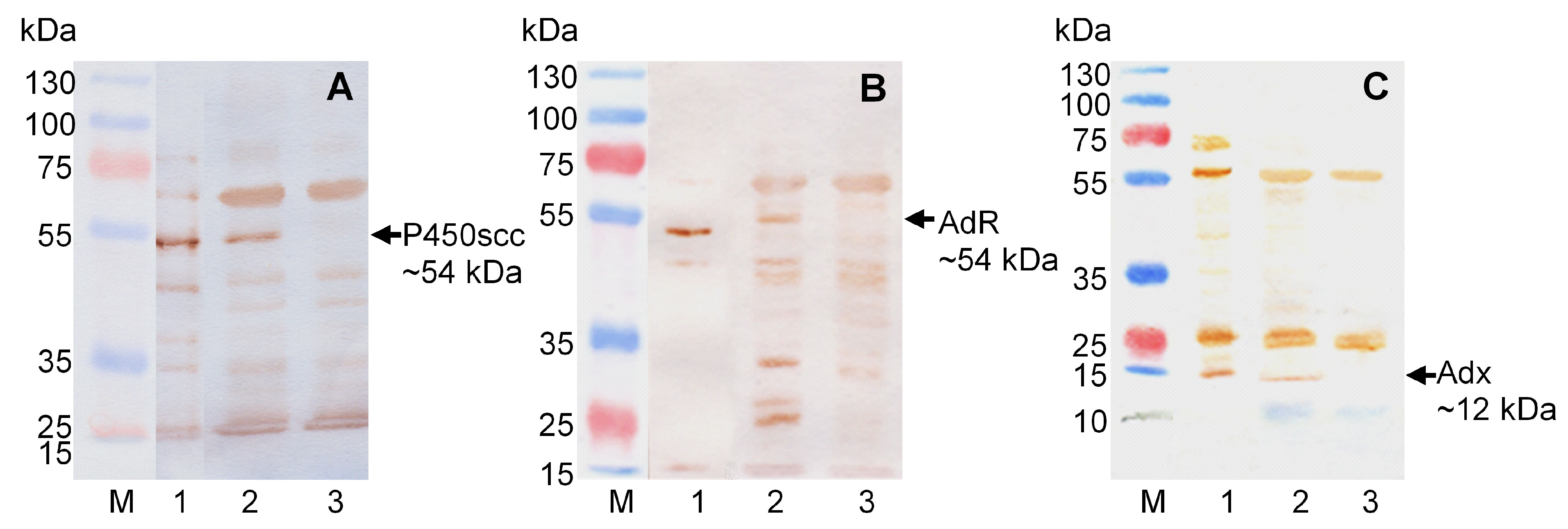

2.1. Creation of Recombinant Strains of M. Extorquens AM1 Providing Bioconversion of Cholesterol to Pregnenolone

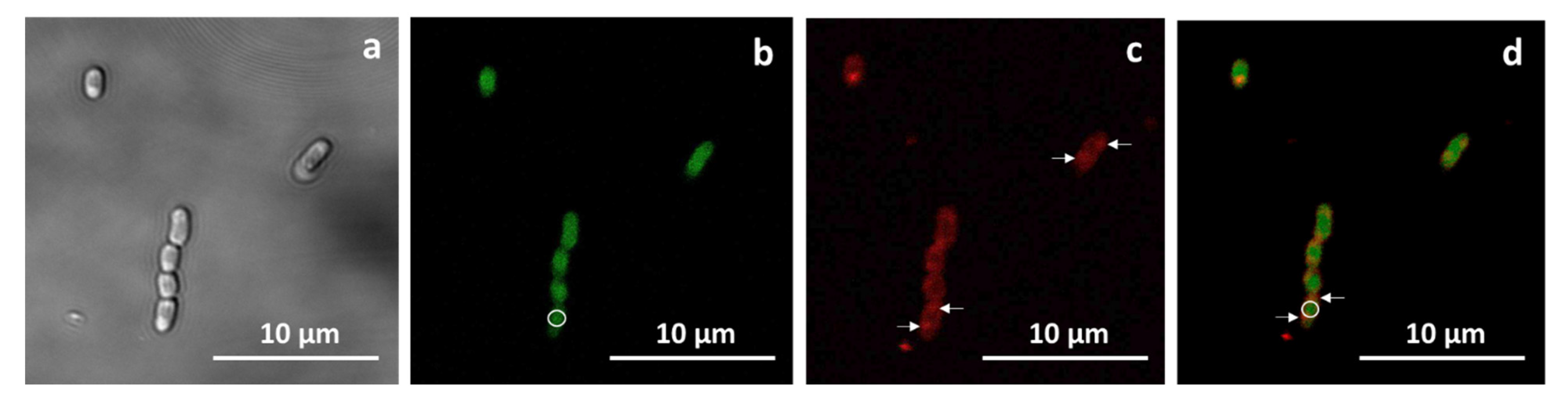

2.2. Visualization of PHB Granules and Cytochrome CYP11A1-GFP in Recombinant M. Extorquens AM1 Cells

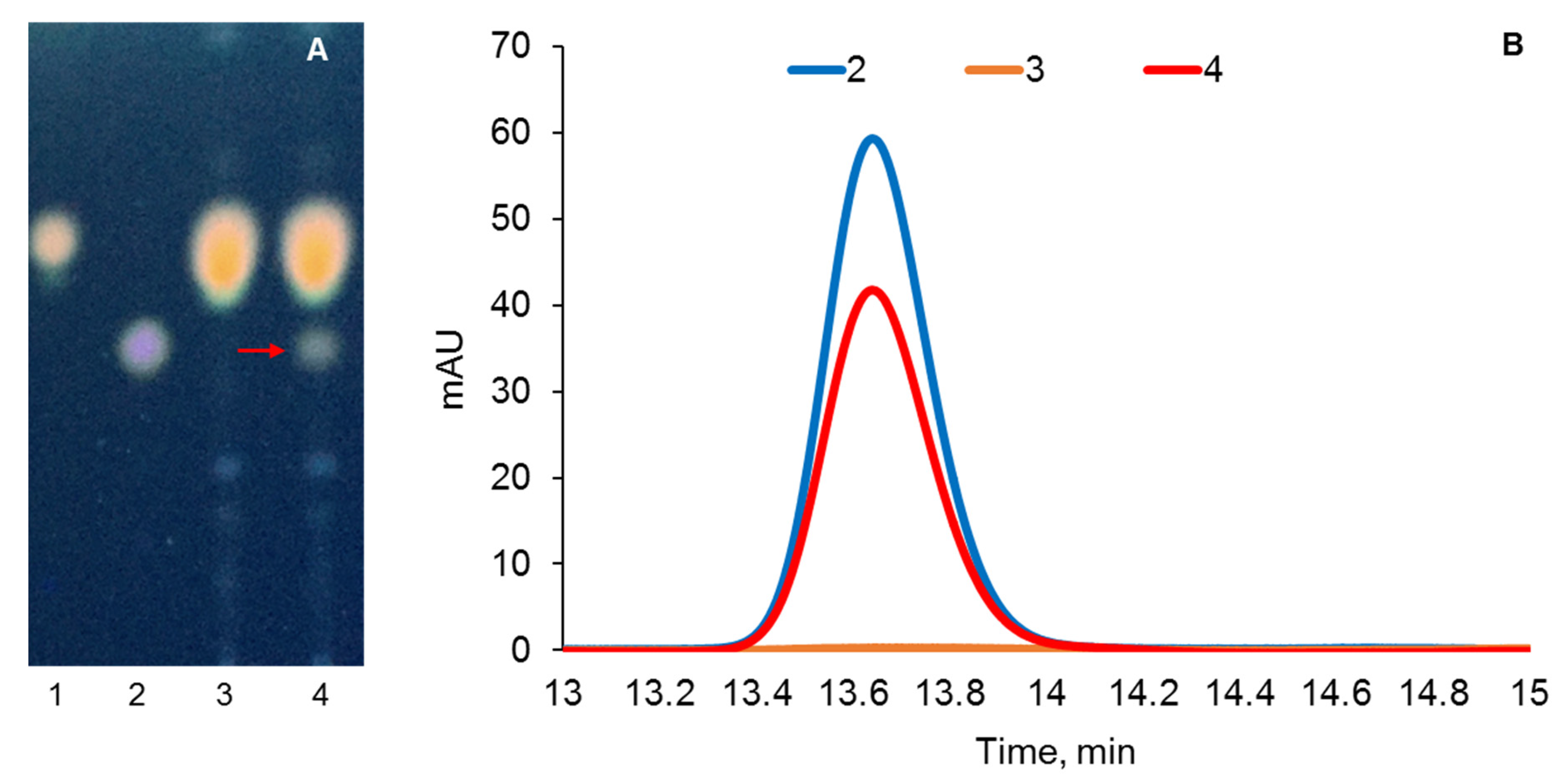

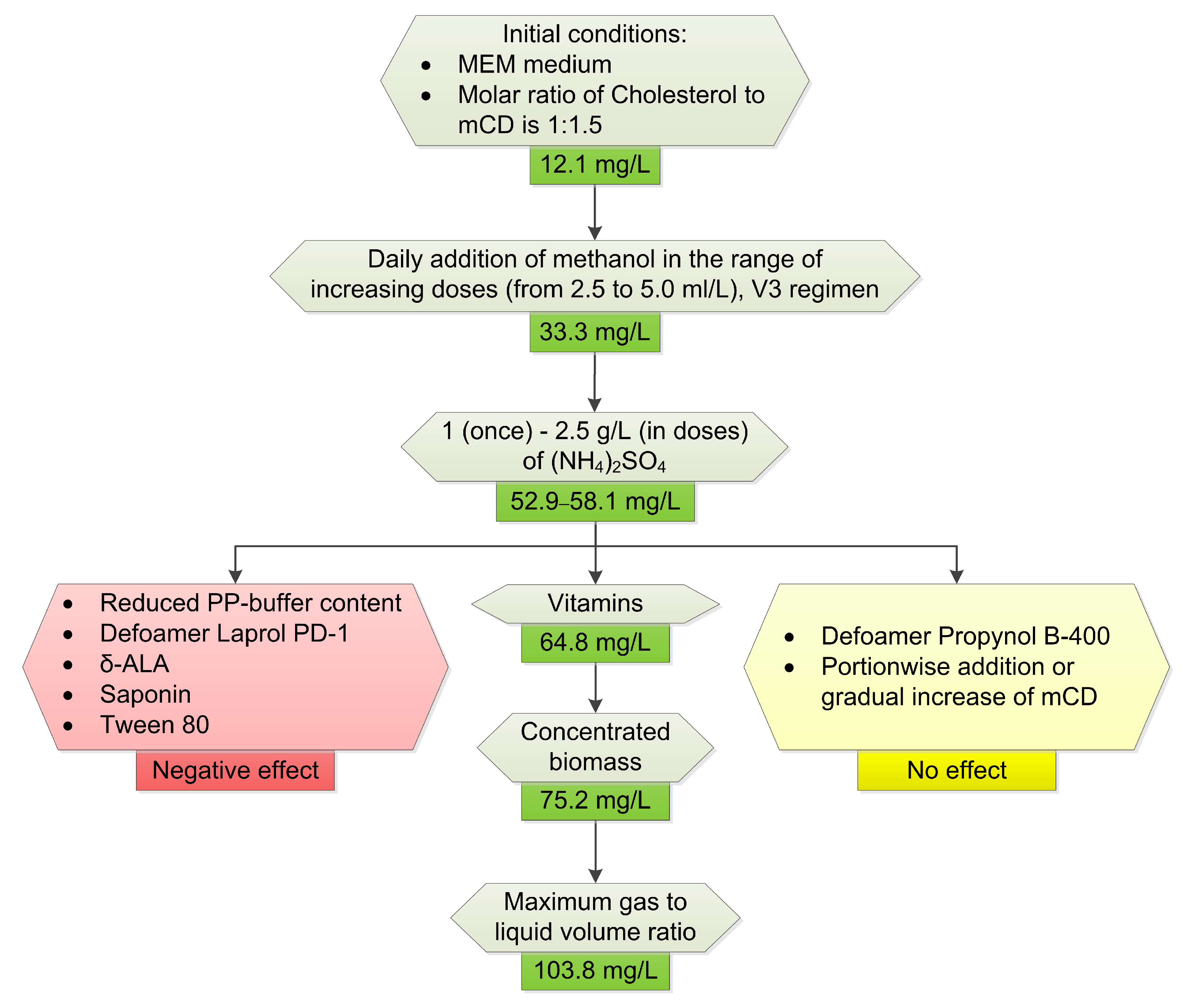

2.3. Optimization of Conditions for Cholesterol Bioconversion

2.3.1. Medium Composition

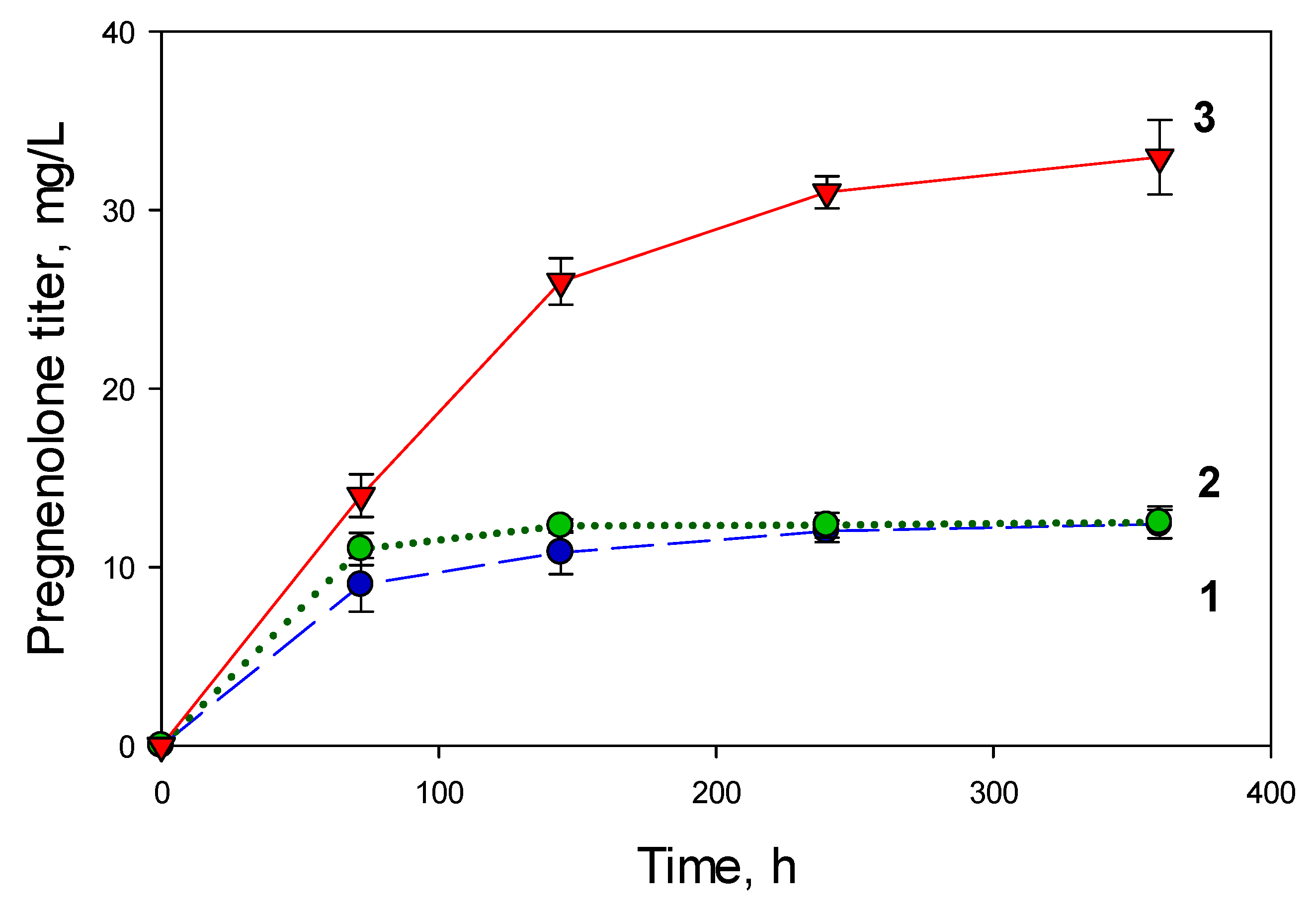

2.3.2. Regimen of Methanol Addition

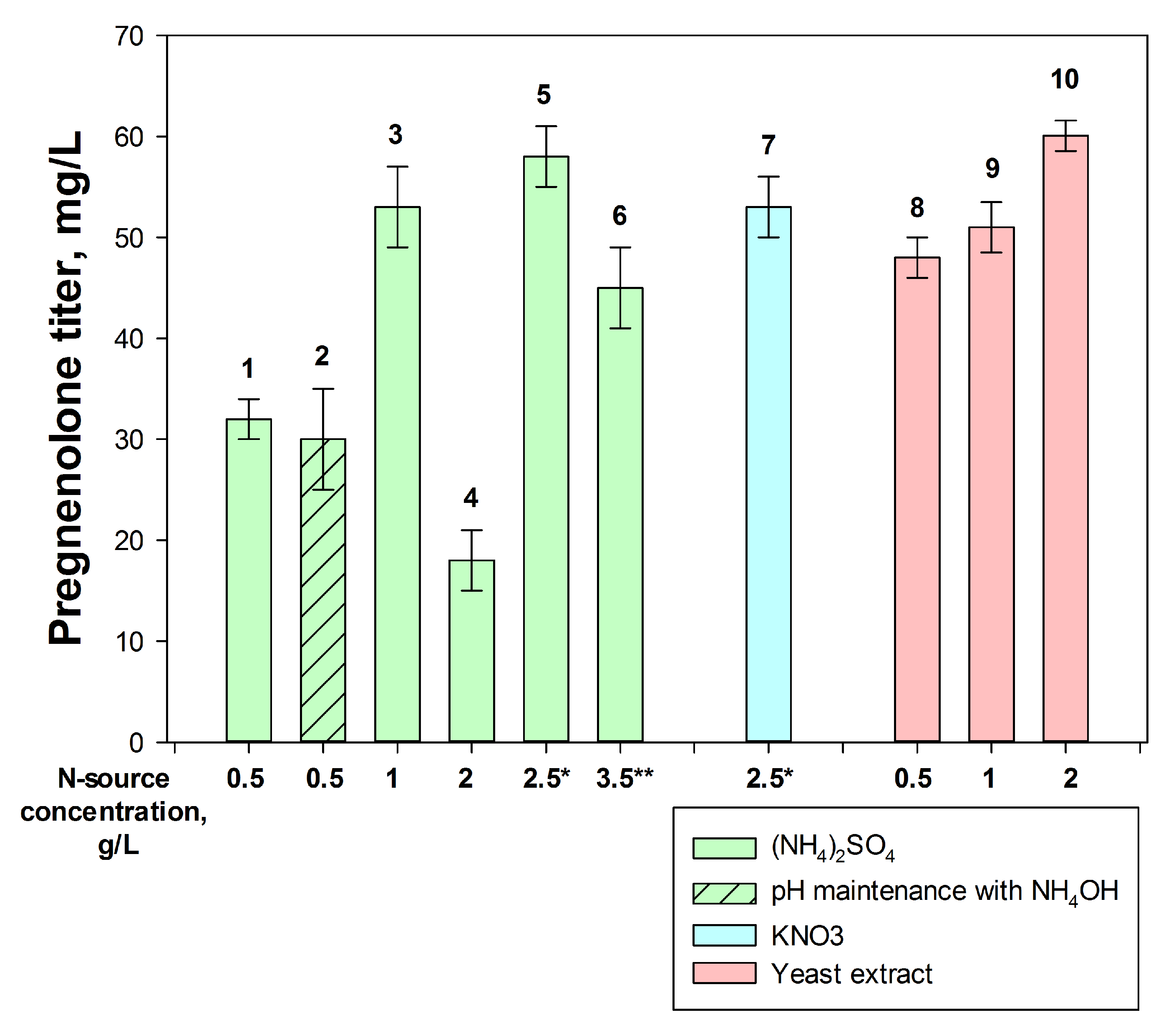

2.3.3. Nitrogen Sources

2.3.4. Influence of Other Components

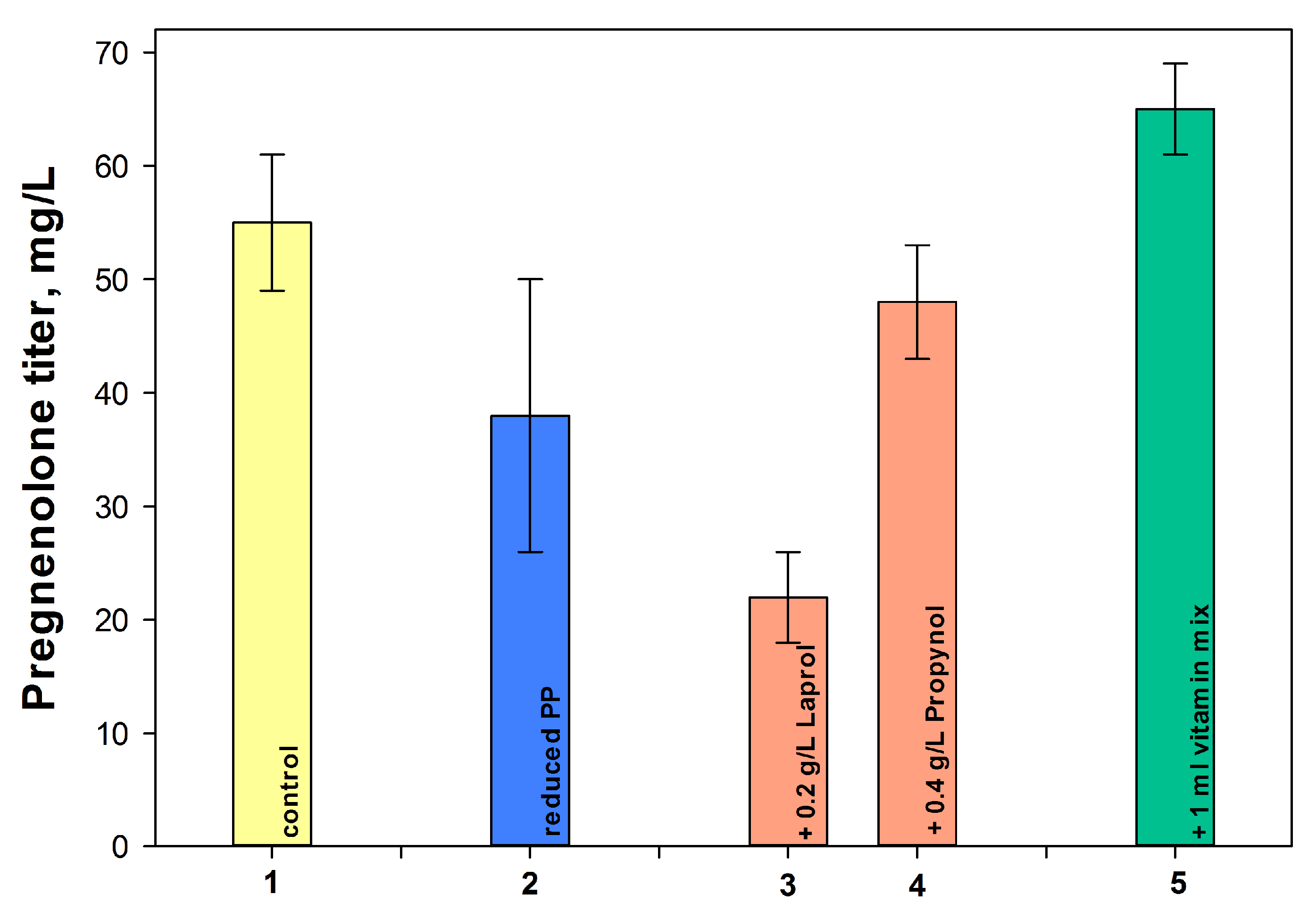

2.3.5. The Effect of Surfactants and Detergents

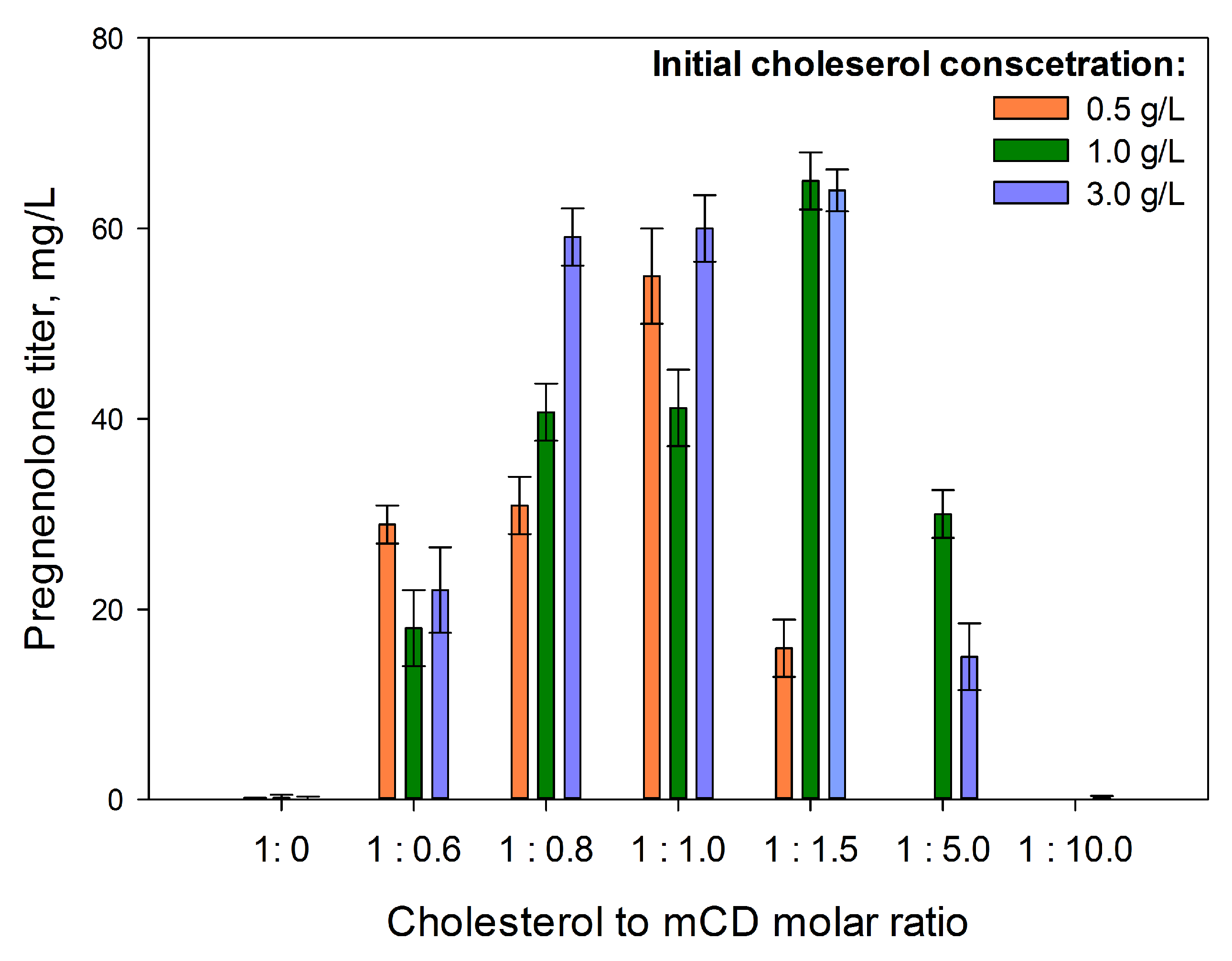

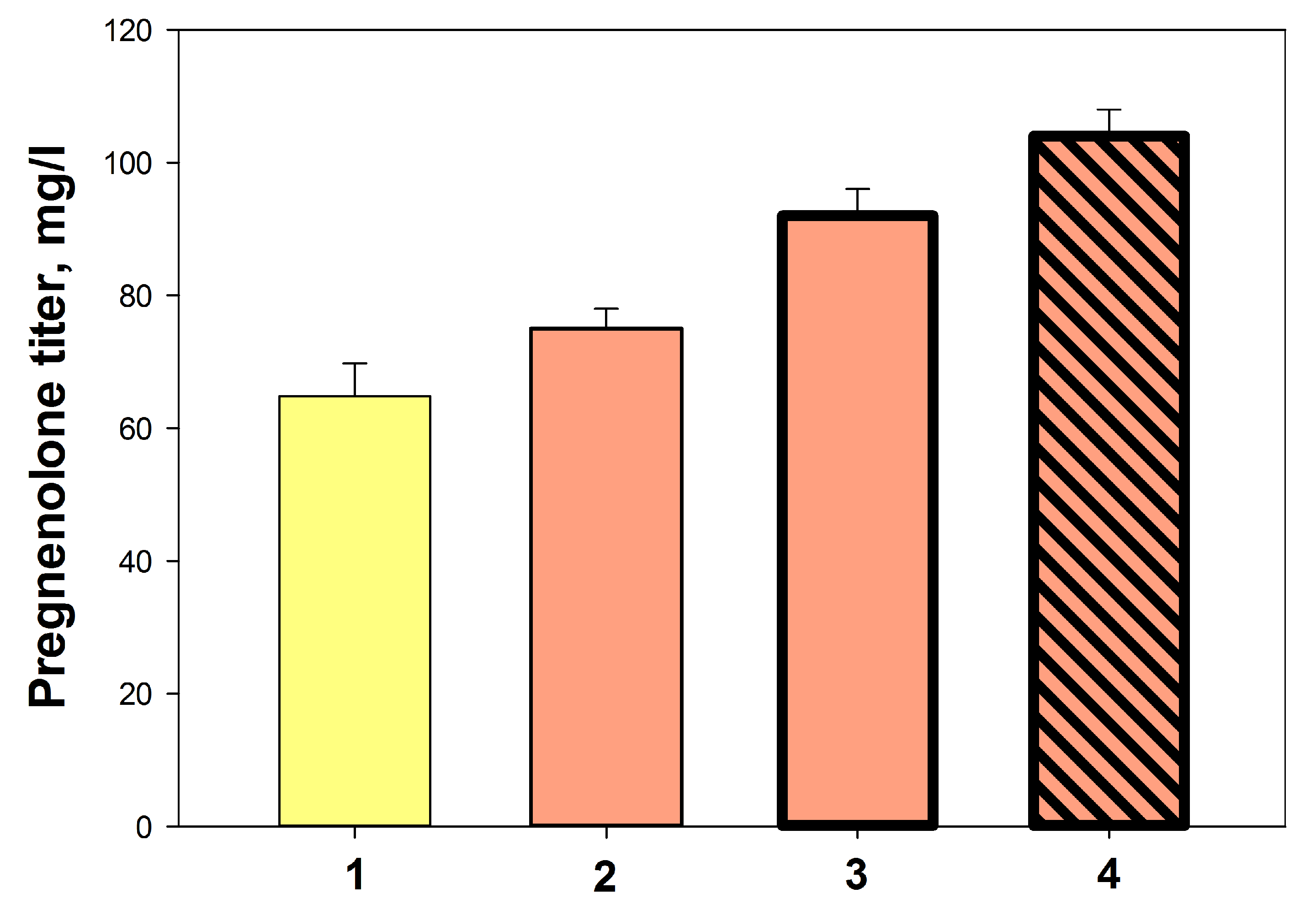

2.3.6. The Influence of Culture Density and Final Optimization

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Reagents

4.2. Strains and Media

4.3. Construction of Plasmids and Recombinant Strains

4.4. Gene Expression and Protein Analysis

4.5. M. Extorquens AM1 Cells Staining and Fluorescence Microscopy

4.6. Bioconversion of Cholesterol

4.7. Optimization of Bioconversion Conditions

4.8. Steroids Assay

4.9. Statistical Analysis

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Payne, A.H.; Hales, D.B. Overview of steroidogenic enzymes in the pathway from cholesterol to active steroid hormones. Endocr. Rev. 2004, 25, 947–970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maurice, T.; Grégoire, C.; Espallergues, J. Neuro(active) steroids actions at the neuromodulatory sigma1 (σ1) receptor: Biochemical and physiological evidences consequences in neuroprotection. Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav. 2006, 84, 581–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naylor, J.C.; Kilts, J.D.; Hulette, C.M.; Steffens, D.C.; Blazer, D.G.; Ervin, J.F.; Strauss, J.L.; Allen, T.B.; Massing, M.W.; Payne, V.M.; et al. Allopregnanolone levels are reduced in temporal cortex in patients with Alzheimer’s disease compared to cognitively intact control subjects. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2010, 1801, 951–959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Vallée, M. Neurosteroids and potential therapeutics: Focus on pregnenolone. J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2016, 160, 78–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choudhary, M.I.; Alam, M.S.; Atta-Ur-Rahman; Yousuf, S.; Wu, Y.C.; Lin, A.S.; Shaheen, F. Pregnenolone derivatives as potential anticancer agents. Steroids 2011, 76, 1554–1559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.C.; Cheung, G.; Porter, E.; Papadopoulos, V. The neurosteroid pregnenolone is synthesized by a mitochondrial P450 enzyme other than CYP11A1 in human glial cells. J. Biol. Chem. 2022, 298, 102110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dávola, M.E.; Mazaira, G.I.; Galigniana, M.D.; Alché, L.E.; Ramírez, J.A.; Barquero, A.A. Synthetic pregnenolone derivatives as antiviral agents against acyclovir-resistant isolates of Herpes Simplex Virus Type 1. Antivir. Res. 2015, 122, 55–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porta, E.O.; Carvalho, P.B.; Avery, M.A.; Tekwani, B.L.; Labadie, G.R. Click chemistry decoration of amino sterols as promising strategy to developed new leishmanicidal drugs. Steroids 2014, 79, 28–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morohashi, K.; Fujii-Kuriyama, Y.; Okada, Y.; Sogawa, K.; Hirose, T.; Inayama, S.; Omura, T. Molecular cloning and nucleotide sequence of cDNA for mRNA of mitochondrial cytochrome P-450(SCC) of bovine adrenal cortex. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1984, 81, 4647–4651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novikova, L.A.; Faletrov, Y.V.; Kovaleva, I.E.; Mauersberger, S.; Luzikov, V.N.; Shkumatov, V.M. From structure and functions of steroidogenic enzymes to new technologies of gene engineering. Biochemistry (Moscow) 2009, 74, 1482–1504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wada, A.; Mathew, P.A.; Barnes, H.J.; Sanders, D.; Estabrook, R.W.; Waterman, M.R. Expression of functional bovine cholesterol side chain cleavage cytochrome P450 (P450scc) in Escherichia coli. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 1991, 290, 376–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Makeeva, D.S.; Dovbnya, D.V.; Donova, M.V.; Novikova, L.A. Functional reconstruction of bovine P450scc steroidogenic system in Escherichia coli. Amer. J. Mol. Biol. 2013, 3, 173–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Efimova, V.S.; Isaeva, L.V.; Rubtsov, M.A.; Novikova, L.A. Analysis of In Vivo Activity of the Bovine Cholesterol Hydroxylase/Lyase System Proteins Expressed in Escherichia coli. Mol. Biotechnol. 2019, 61, 261–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duport, C.; Spagnoli, R.; Degryse, E.; Pompon, D. Self-sufficient biosynthesis of pregnenolone and progesterone in engineered yeast. Nat. Biotechnol. 1998, 16, 186–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Yao, M.; Zhang, J.; Liu, H.; Zhou, X.; Xiao, W.; Yuan, Y. Pregnenolone Overproduction in Yarrowia lipolytica by Integrative Components Pairing of the Cytochrome P450scc System. ACS Synth. Biol. 2019, 8, 2666–2678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strizhov, N.; Fokina, V.; Sukhodolskaya, G.; Dovbnya, D.; Karpov, M.; Shutov, A.; Novikova, L.; Donova, M. Progesterone biosynthesis by combined action of adrenal steroidogenic and mycobacterial enzymes in fast growing mycobacteria. New Biotechnol. 2014, 31, S67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karpov, M.; Strizhov, N.; Novikova, L.; Lobastova, T.; Khomutov, S.; Shutov, A.; Kazantsev, A.; Donova, M. Pregnenolone and progesterone production from natural sterols using recombinant strain of Mycolicibacterium smegmatis mc2 155 expressing mammalian steroidogenesis system. Microb. Cell Fact. 2024, 23, 105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerber, A.; Kleser, M.; Biedendieck, R.; Bernhardt, R.; Hannemann, F. Functionalized PHB granules provide the basis for the efficient side-chain cleavage of cholesterol and analogs in recombinant Bacillus megaterium. Microb. Cell Fact. 2015, 14, 107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grage, K.; Jahns, A.C.; Parlane, N.; Palanisamy, R.; Rasiah, I.A.; Atwood, J.A.; Rehm, B.H.A. Bacterial polyhydroxyalkanoate granules: Biogenesis, structure, and potential use as nano-/micro-beads in biotechnological and biomedical applications. Biomacromolecules 2009, 10, 660–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, I.J.; Anthony, C. A biochemical basis for obligate methylotrophy: Properties of a mutant of Pseudomonas AM1 lacking 2-oxoglutarate dehydrogenase. J. Gen. Microbiol. 1976, 93, 259–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lidstrom, M.E. The Genetics and Molecular Biology of Methanol-Utilizing Bacteria. In Methane and Methanol Utilizers, 1st ed.; Murrell, J.C., Dalton, H., Eds.; Plenum Press: New York, NY, USA, 1992; Volume 5, pp. 183–206. [Google Scholar]

- Van Dien, S.J.; Okubo, Y.; Hough, M.T.; Korotkova, N.; Taitano, T.; Lidstrom, M.E. Reconstruction of C3 and C4 metabolism in Methylobacterium extorquens AM1 using transposon mutagenesis. Microbiology 2003, 149, 601–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Large, P.; Peel, D.; Quayle, J. Microbial growth on C1 compounds. II. Synthesis of cell constituents by methanol-and formate-grown Pseudomonas AM1, and methanol-grown Hyphomicrobium vulgare. Biochem. J. 1961, 81, 470–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chistoserdova, L.; Chen, S.W.; Lapidus, A.; Lidstrom, M.E. Methylotrophy in Methylobacterium extorquens AM1 from a genomic point of view. J. Bacteriol. 2003, 185, 2980–2987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lim, C.K.; Villada, J.C.; Chalifour, A.; Duran, M.F.; Lu, H.; Lee, P.K.H. Designing and Engineering Methylorubrum extorquens AM1 for Itaconic Acid Production. Front. Microbiol. 2019, 10, 1027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kiefer, P.; Portais, J.C.; Vorholt, J.A. Quantitative metabolome analysis using liquid chromatography-high-resolution mass spectrometry. Anal. Biochem. 2008, 382, 94–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiaofeng, G.; Lidstrom, M.E. Metabolite profiling analysis of Methylobacterium extorquens AM1 by comprehensive two-dimensional gas chromatography coupled with time-of-flight mass spectrometry. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 2008, 99, 929–940. [Google Scholar]

- Peyraud, R.; Kiefer, P.; Christen, P.; Massou, S.; Portais, J.-C.; Vorholt, J.A. Demonstration of the ethylmalonyl-CoA pathway by using 13C metabolomics. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2009, 106, 4846–4851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marx, C.J.; Lidstrom, M.E. Development of improved versatile broad-hostrange vectors for use in methylotrophs and other Gram-negative bacteria. Microbiology 2001, 147, 2065–2075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marx, C.J. Development of a broad-host-range sacB-based vector for unmarked allelic exchange. BMC Res. Notes 2008, 1, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chou, H.H.; Marx, C.J. Optimization of gene expression through divergent mutational paths. Cell Rep. 2012, 1, 133–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sonntag, F.; Buchhaupt, M.; Schrader, J. Thioesterases for ethylmalonyl-CoA pathway derived dicarboxylic acid production in Methylobacterium extorquens AM1. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2014, 98, 4533–4544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, B.; Lidstrom, M.E. Metabolic engineering of Methylobacterium extorquens AM1 for 1-butanol production. Biotechnol. Biofuels 2014, 7, 156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Orita, I.; Nishikawa, K.; Nakamura, S.; Fukui, T. Biosynthesis of polyhydroxyalkanoate copolymers from methanol by Methylobacterium extorquens AM1 and the engineered strains under cobalt-deficient conditions. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2014, 98, 3715–3725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Korotkova, N.; Lidstrom, M.E. Connection between Poly-β-Hydroxybutyrate Biosynthesis and Growth on C1 and C2 Compounds in the Methylotroph Methylobacterium extorquensAM1. J. Bacteriol. 2001, 183, 1038–1046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korotkova, N.; Chistoserdova, L.; Lidstrom, M.E. Poly-beta-hydroxybutyrate biosynthesis in the facultative methylotroph Methylobacterium extorquens AM1: Identification and mutation of gap11, gap20, and phaR. J. Bacteriol. 2002, 184, 6174–6181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kranz, R.G.; Gabbert, K.K.; Madigan, M.T. Positive selection systems for discovery of novel polyester biosynthesis genes based on fatty acid detoxification. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1997, 63, 3010–3013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshida, Y.; Iguchi, H.; Sakai, Y.; Yurimoto, H. Pantothenate auxotrophy of Methylobacterium spp. isolated from living plants. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 2019, 83, 569–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujiwara, T.; Harigae, H. Biology of Heme in Mammalian Erythroid Cells and Related Disorders. Biomed. Res. Int. 2015, 2015, 278536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, L.B.; Liu, H.H.; Zhao, M.; Liu, Y.J.; Song, L.; Xie, Z.Y.; Xu, Y.X.; Wang, F.Q.; Wei, D.Z. Enhancing the bioconversion of phytosterols to steroidal intermediates by the deficiency of kasB in the cell wall synthesis of Mycobacterium neoaurum. Microb. Cell Fact. 2020, 19, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, L.; Xu, S.; Shen, Y.; Xia, M.; Ren, X.; Wang, L.; Shang, Z.; Wang, M. The Sterol carrier hydroxypropyl-β-cyclodextrin enhances the metabolism of phytosterols by Mycobacterium neoaurum. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2020, 86, e00441-20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tekucheva, D.N.; Nikolayeva, V.M.; Karpov, M.V.; Timakova, T.A.; Shutov, A.V.; Donova, M.V. Bioproduction of testosterone from phytosterol by Mycolicibacterium neoaurum strains: “One-pot”, two modes. Bioresour. Bioprocess. 2022, 9, 116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tekucheva, D.N.; Fokina, V.V.; Nikolaeva, V.M.; Shutov, A.A.; Karpov, M.V.; Donova, M.V. Cascade biotransformation of phytosterol to testosterone by Mycolicibacterium neoaurum VKM Ac-1815D and Nocardioides simplex VKM Ac-2033D strains. Microbiology 2022, 91, 303–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khomutov, S.M.; Sidorov, I.A.; Dovbnya, D.V.; Donova, M.V. Estimation of cyclodextrin affinity to steroids. J. Pharm. Pharmacol. 2002, 54, 617–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Zhang, Y.; Shen, Y.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, Z.; Xu, S.; Luo, J.; Xia, M.; Wang, M. Economical production of androstendione and 9α-hydroxyandrostendione using untreated cane molasses by recombinant mycobacteria. Bioresour. Technol. 2019, 290, 121750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Donova, M.V.; Nikolayeva, V.M.; Dovbnya, D.V.; Gulevskaya, S.A.; Suzina, N.E. Methyl-β-cyclodextrin alters growth, activity and cell envelope features of sterol-transforming mycobacteria. Microbiology 2007, 153, 1981–1992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khomutov, S.M.; Sukhodolskaya, G.V.; Donova, M.V. The inhibitory effect of cyclodextrin on the degradation of 9α-hydroxyandrost-4-ene-3,17-dione by Mycobacterium sp. VKM Ac-1817D. Biocatal. Biotransform. 2007, 25, 386–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, R.; Ren, X.; Xia, M.; Shen, Y.; Tu, L.; Luo, J.; Zhang, Q.; Wang, Y.; Ji, P.; Wang, M. Efficient one-step biocatalic multienzyme cascade strategy for direct conversion of phytosterol to C17-hydroxylated steroids. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2021, 87, e0032121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morisaki, M.; Duque, C.; Takane, K.; Ikekawa, N.; Shikita, M. Substrate specificity of adrenocortical cytochrome P-450SCC. II. Effect of structural modification of cholesterol A/B ring on their side chain cleavage reaction. J. Steroid Biochem. 1982, 16, 101–105. [Google Scholar]

- Ivashina, T.V.; Nikolaeva, V.M.; Dovbnya, D.V.; Donova, M.V. Cholesterol oxidase ChoD is not a critical enzyme accounting for oxidation of sterols to 3-keto-4-ene steroids in fast-growing Mycobacterium sp. VKM Ac-1815D. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2012, 129, 47–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivanova, E.G.; Doronina, N.V.; Trotsenko, Y.A. Aerobic methylobacteria are capable of synthesizing auxins. Microbiology 2001, 70, 392–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertani, G. Studies on lysogenesis. I. The mode of phage liberation by lysogenic Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 1951, 62, 293–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Efimova, V.S.; Isaeva, L.V.; Labudina, A.A.; Tashlitsky, V.N.; Rubtsov, M.A.; Novikova, L.A. Polycistronic expression of the mitochondrial steroidogenic P450scc system in the HEK293T cell line. J. Cell Biochem. 2019, 120, 3124–3136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simon, R.; Priefer, U.; Puhler, A. A broad host range mobilization system for in vivo genetic engineering: Transposon mutagenesis in Gram negative bacteria. Nat. Biotechnol. 1983, 1, 784–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laemmli, U.K. Cleavage of Structural Proteins during the Assembly of the Head of Bacteriophage T4. Nature 1970, 227, 680–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sidhu, R.S.; Bollon, A.P. Analysis of alpha-factor secretion signals by fusing with acid phosphatase of yeast. Gene 1987, 54, 175–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lowry, O.H.; Rosebrough, N.J.; Farr, A.L.; Randall, R.J. Protein measurement with the Folin phenol reagent. J. Biol. Chem. 1951, 193, 265–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Strain or Plasmid | Description | Source or Reference |

|---|---|---|

| Plasmids: | ||

| pNS11 | The pMyNT vector included 3.3 kb fragment with cDNA, encoding RBS-AdR-RBS-Adx-RBS-CYP11A1 | [17] |

| pCM160 | E. coli и M. extorquens shuttle expression vector, KmR, PmxaF, ColE1-IncP | [29] |

| pCM_NS11 | pCM160 vector included 3352 bp fragment with cDNA, encoding RBS-AdR-RBS-Adx-RBS-CYP11A1 inserted by sites SacI-SphI | Current research |

| pCoxIV-CHL-GFP | Plasmid containing cDNA for GFP-fused CHL polyprotein | [53] |

| pCM160-P450-GFP | Plasmid includes cDNA for CYP11A1-GFP inserted in the frame with lacZa sequence together | Current research |

| Strains: | ||

| Escherichia coli DH5α | F– φ80lacZΔM15 Δ(lacZYA-argF)U169 recA1 endA1 hsdR17(rK−, mK+) phoA supE44 λ–thi-1 gyrA96 relA1 | Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA |

| Escherichia coli S17-1 | RP4-2(Km::Tn7,Tc::Mu-1), pro-82, LAMpir, recA1, endA1, thiE1, hsdR17, creC510 | [54] |

| Methylorubrum extorquens AM1 | Model strain used to study methylotrophy and biotechnological applications of methylobacteria | Deposited in all-Russian collection of microorganisms (IBPM) as VKM B-2064T |

| Primers: | ||

| NS11for | CACTAAGCATGCGCCACCACCCGATAAGAG * | Current research |

| NS11rev | AGAGCTCGCTATCGATAAGCTTTCA * | Current research |

| Adrf | ATGGCGAGCACTCAAGAACAAAC | Current research |

| Adxr | ATCTGGCAGCCCAACCGCGATC | Current research |

| GFPfor | GCTCCAGATATCGCATGCTGTCCACAAAGACCC * | Current research |

| GFPrev | CAGCGAGCTCAATTCATTATTTGTACAGCTCATCC * | Current research |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Tekucheva, D.; Poshekhontseva, V.; Fedorov, D.; Karpov, M.; Novikova, L.; Zamalutdinov, A.; Donova, M. Pregnenolone Bioproduction in Engineered Methylobacteria: Design and Elaboration. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 10975. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262210975

Tekucheva D, Poshekhontseva V, Fedorov D, Karpov M, Novikova L, Zamalutdinov A, Donova M. Pregnenolone Bioproduction in Engineered Methylobacteria: Design and Elaboration. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2025; 26(22):10975. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262210975

Chicago/Turabian StyleTekucheva, Daria, Veronika Poshekhontseva, Dmitry Fedorov, Mikhail Karpov, Ludmila Novikova, Alexey Zamalutdinov, and Marina Donova. 2025. "Pregnenolone Bioproduction in Engineered Methylobacteria: Design and Elaboration" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 26, no. 22: 10975. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262210975

APA StyleTekucheva, D., Poshekhontseva, V., Fedorov, D., Karpov, M., Novikova, L., Zamalutdinov, A., & Donova, M. (2025). Pregnenolone Bioproduction in Engineered Methylobacteria: Design and Elaboration. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 26(22), 10975. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262210975