AT-TSVM: Improving Transmembrane Protein Inter-Helical Residue Contact Prediction Using Active Transfer Transductive Support Vector Machines

Abstract

1. Introduction

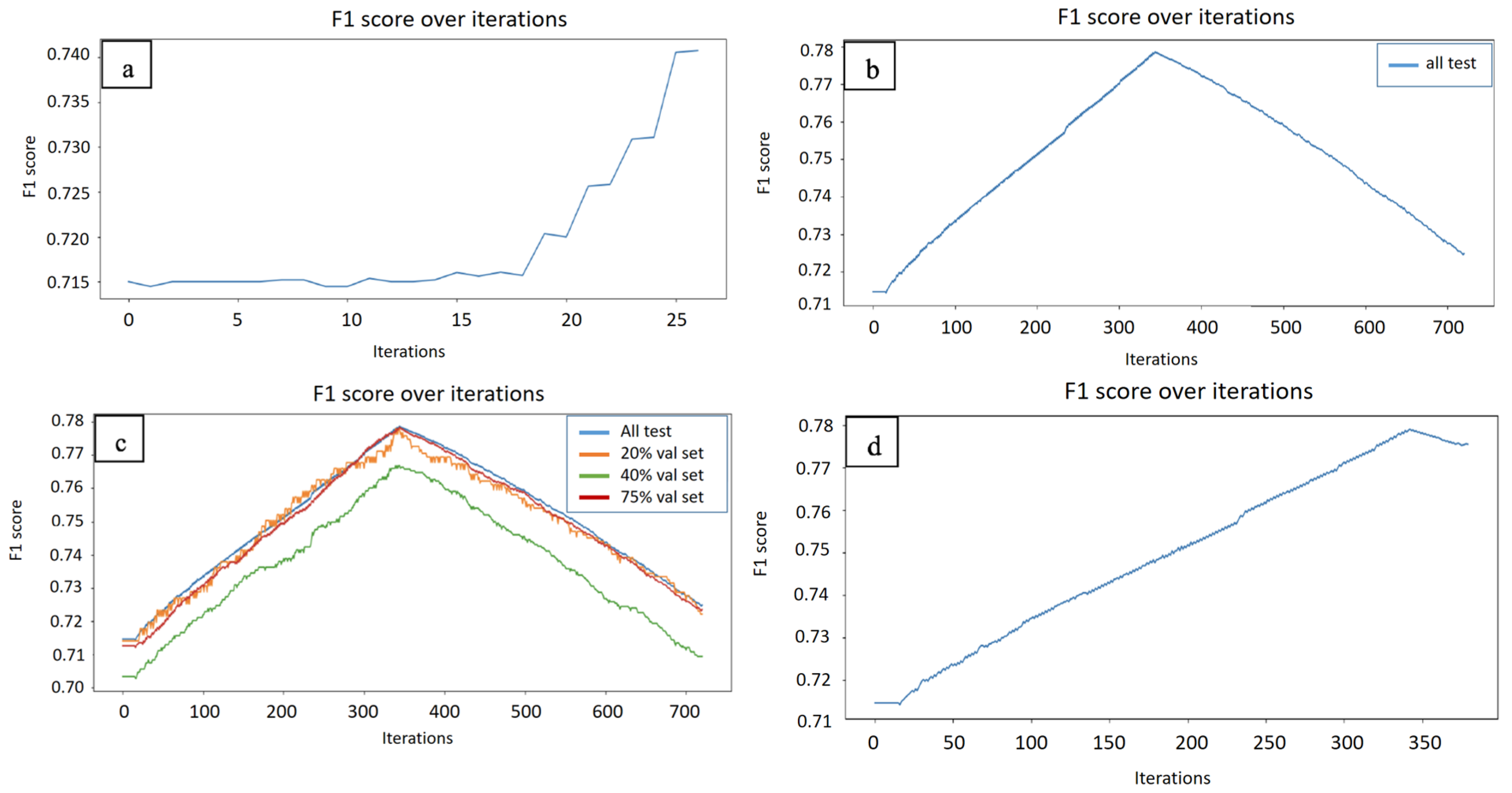

2. Results and Discussion

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Dataset

3.1.1. Sequence Features

3.1.2. Atomic Features

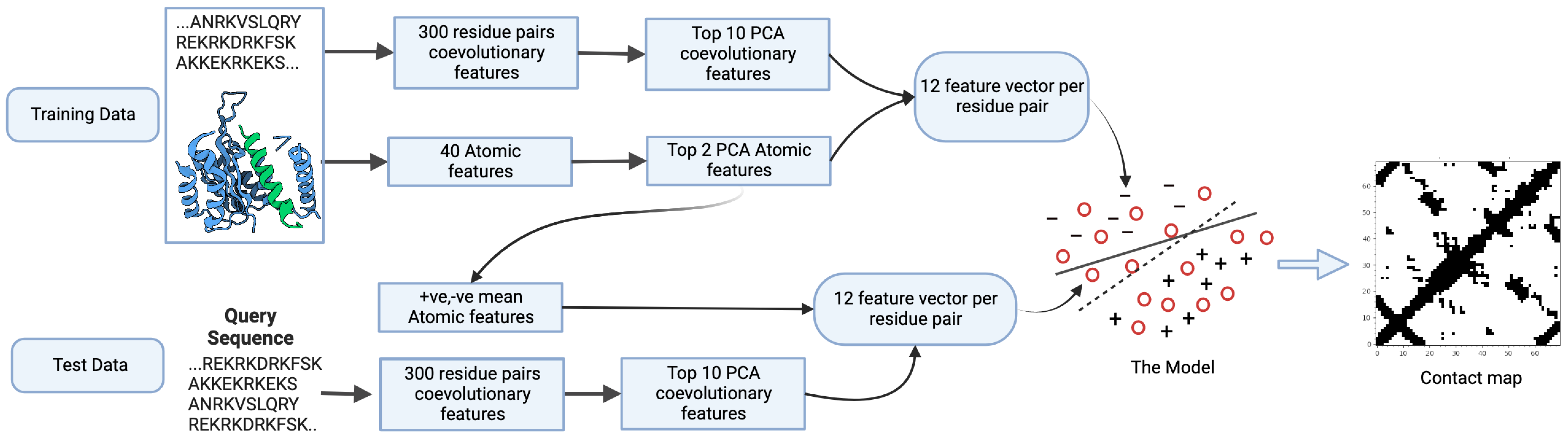

3.1.3. Feature Fusion

3.2. Method

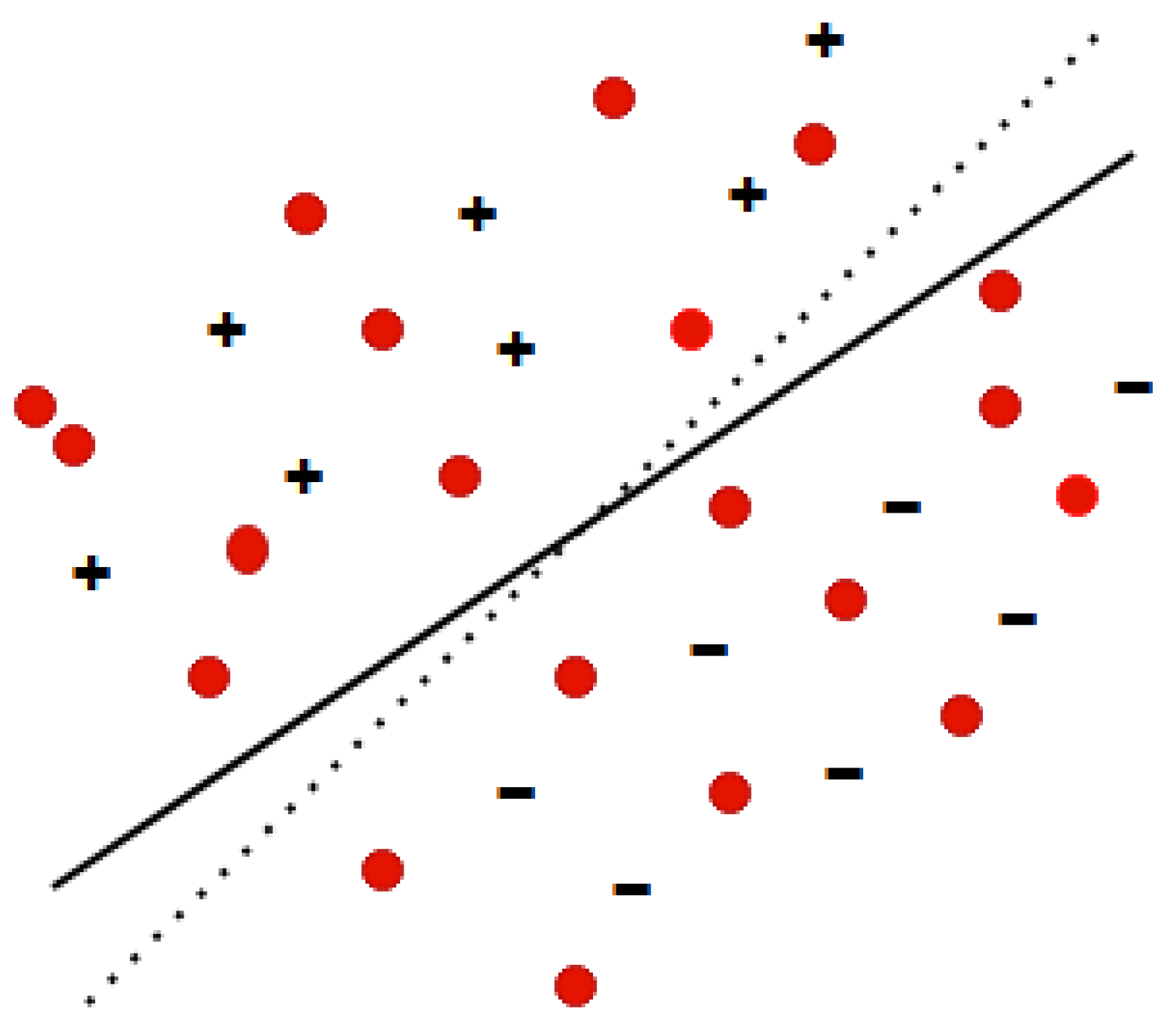

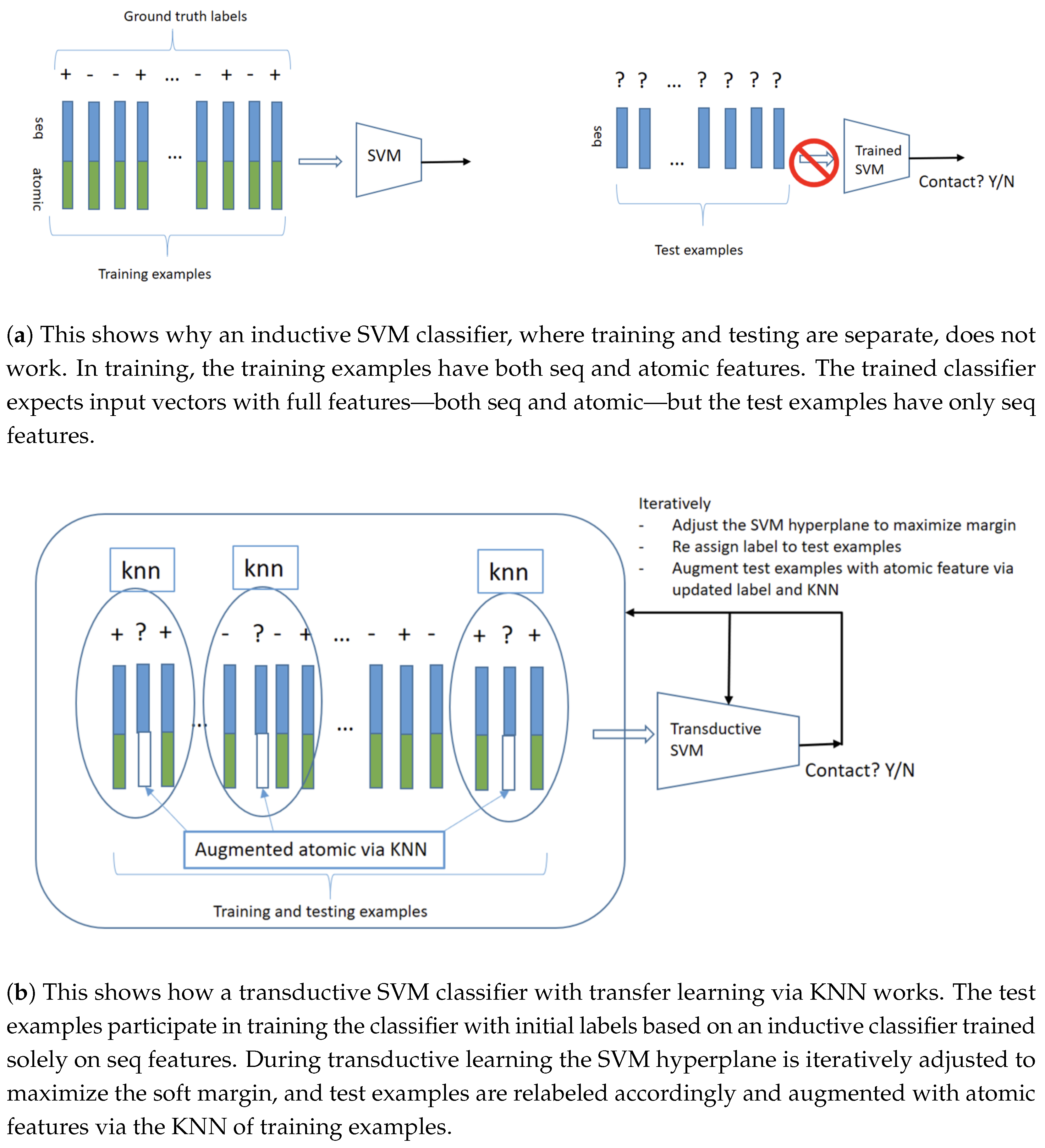

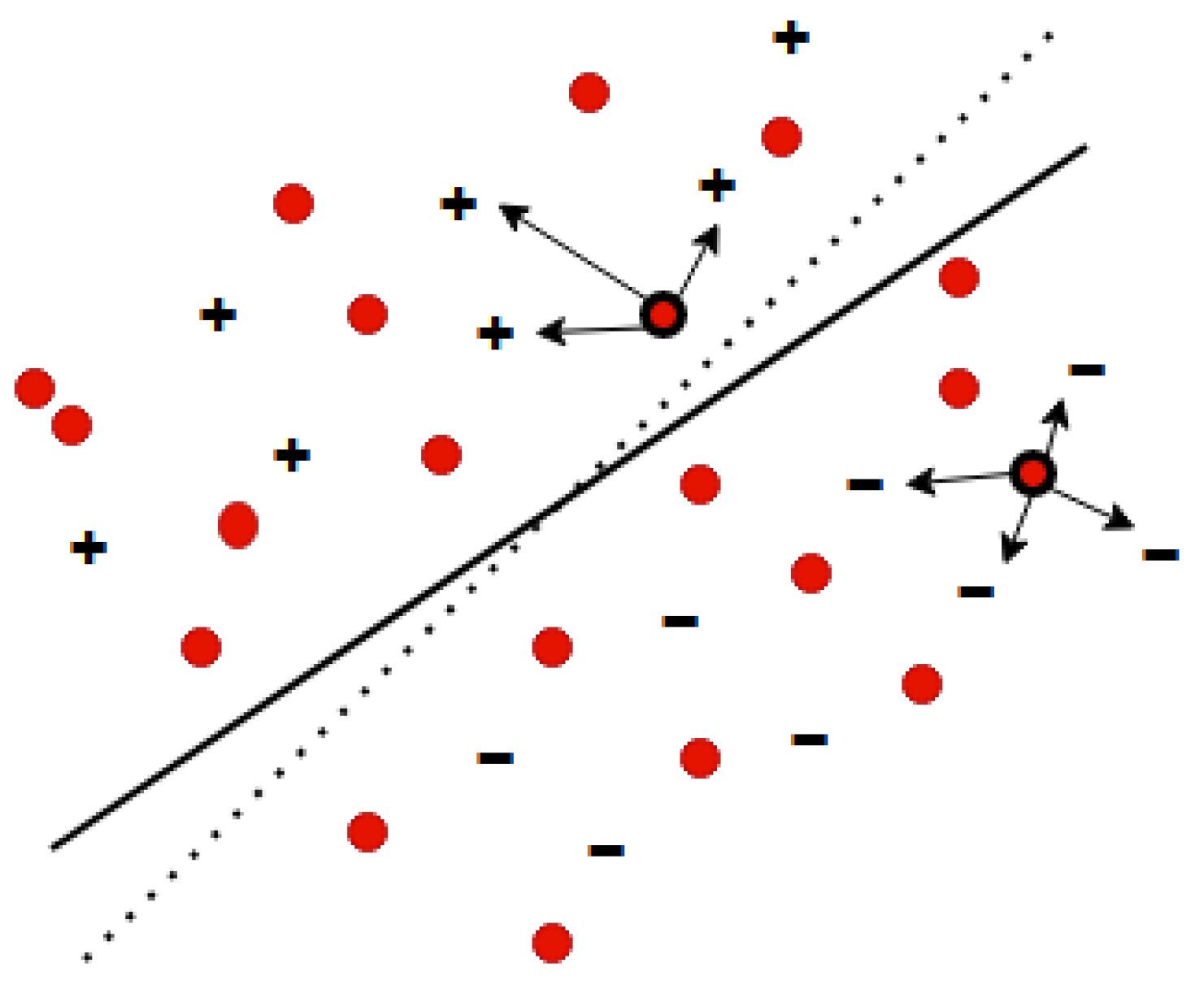

3.2.1. Transductive Support Vector Machines

3.2.2. Transfer Learning

| Algorithm 1 TSVM Algorithm |

|

| Algorithm 2 Transfer Learning Algorithm |

|

| Algorithm 3 Delayed active learning |

|

3.2.3. Active Learning

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Engel, A.; Gaub, H.E. Structure and mechanics of membrane proteins. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2008, 77, 127–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alberts, B. Molecular Biology of the Cell; Garland Science: New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Xia, Y.; Fischer, A.W.; Teixeira, P.; Weiner, B.; Meiler, J. Integrated structural biology for α-helical membrane protein structure determination. Structure 2018, 26, 657–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Téletchéa, S.; Esque, J.; Urbain, A.; Etchebest, C.; de Brevern, A.G. Evaluation of Transmembrane Protein Structural Models Using HPMScore. BioMedInformatics 2023, 3, 306–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yıldırım, M.A.; Goh, K.I.; Cusick, M.E.; Barabási, A.L.; Vidal, M. Drug—target network. Nat. Biotechnol. 2007, 25, 1119–1126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Torrisi, M.; Pollastri, G.; Le, Q. Deep learning methods in protein structure prediction. Comput. Struct. Biotechnol. J. 2020, 18, 1301–1310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vassura, M.; Margara, L.; Di Lena, P.; Medri, F.; Fariselli, P.; Casadio, R. Reconstruction of 3D structures from protein contact maps. IEEE/ACM Trans. Comput. Biol. Bioinform. 2008, 5, 357–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seemayer, S.; Gruber, M.; Söding, J. CCMpred—fast and precise prediction of protein residue–residue contacts from correlated mutations. Bioinformatics 2014, 30, 3128–3130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jones, D.T.; Buchan, D.W.; Cozzetto, D.; Pontil, M. PSICOV: Precise structural contact prediction using sparse inverse covariance estimation on large multiple sequence alignments. Bioinformatics 2012, 28, 184–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marks, D.S.; Colwell, L.J.; Sheridan, R.; Hopf, T.A.; Pagnani, A.; Zecchina, R.; Sander, C. Protein 3D structure computed from evolutionary sequence variation. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e28766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Lee, J.Y.; Liao, L. Improving Inter-Helix Contact Prediction With Local 2D Topological Information. IEEE/ACM Trans. Comput. Biol. Bioinform. 2023, 20, 3001–3012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, J.; Baldi, P. Improved residue contact prediction using support vector machines and a large feature set. BMC Bioinform. 2007, 8, 113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, J.; Frishman, D. DeepHelicon: Accurate prediction of inter-helical residue contacts in transmembrane proteins by residual neural networks. J. Struct. Biol. 2020, 212, 107574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fiser, A. Template-based protein structure modeling. Comput. Biol. 2010, 673, 73–94. [Google Scholar]

- Sawhney, A.; Li, J.; Liao, L. Inter-helical Residue Contact Prediction in α-Helical Transmembrane Proteins Using Structural Features. In Proceedings of the International Work-Conference on Bioinformatics and Biomedical Engineering, Gran Canaria, Spain, 12–14 July 2023; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2023; pp. 357–371. [Google Scholar]

- Almalki, B.; Sawhney, A.; Liao, L. Transmembrane Protein Inter-Helical Residue Contacts Prediction Using Transductive Support Vector Machines. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Bioinformatics and Computational Biology (BICOB-2023), Online, 20–22 March 2023; Volume 92, pp. 35–46. [Google Scholar]

- Kamisetty, H.; Ovchinnikov, S.; Baker, D. Assessing the utility of coevolution-based residue–residue contact predictions in a sequence- and structure-rich era. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2013, 110, 15674–15679, Erratum in Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2013, 110, 18734.. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jones, D.T.; Singh, T.; Kosciolek, T.; Tetchner, S. MetaPSICOV: Combining coevolution methods for accurate prediction of contacts and long range hydrogen bonding in proteins. Bioinformatics 2015, 31, 999–1006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kandathil, S.M.; Greener, J.G.; Jones, D.T. Prediction of interresidue contacts with DeepMetaPSICOV in CASP13. Proteins Struct. Funct. Bioinform. 2019, 87, 1092–1099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hönigschmid, P.; Frishman, D. Accurate prediction of helix interactions and residue contacts in membrane proteins. J. Struct. Biol. 2016, 194, 112–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ekeberg, M.; Lövkvist, C.; Lan, Y.; Weigt, M.; Aurell, E. Improved contact prediction in proteins: Using pseudolikelihoods to infer Potts models. Physical Review E 2013, 87, 012707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldassi, C.; Zamparo, M.; Feinauer, C.; Procaccini, A.; Zecchina, R.; Weigt, M.; Pagnani, A. Fast and accurate multivariate Gaussian modeling of protein families: Predicting residue contacts and protein-interaction partners. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e92721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, Y.; Gieseke, F.; Oehmcke, S.; Wu, Y.; Barnard, K. Attentional feature fusion. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Winter Conference on Applications of Computer Vision, Virtual, 5–9 January 2021; pp. 3560–3569. [Google Scholar]

- Alex, G.; Katy, A.; Vladimir, V. Learning by transduction. arXiv 2013, arXiv:1301.7375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joachims, T. Transductive inference for text classification using support vector machines. ICML 1999, 99, 200–209. [Google Scholar]

- Weiss, K.; Khoshgoftaar, T.M.; Wang, D. A survey of transfer learning. J. Big Data 2016, 3, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Settles, B. Active Learning Literature Survey. 2009. Available online: http://digital.library.wisc.edu/1793/60660 (accessed on 9 November 2025).

- Wang, X.; Wen, J.; Alam, S.; Jiang, Z.; Wu, Y. Semi-supervised learning combining transductive support vector machine with active learning. Neurocomputing 2016, 173, 1288–1298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jumper, J.; Evans, R.; Pritzel, A.; Green, T.; Figurnov, M.; Ronneberger, O.; Tunyasuvunakool, K.; Bates, R.; Žídek, A.; Potapenko, A.; et al. Highly accurate protein structure prediction with AlphaFold. Nature 2021, 596, 583–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abramson, J.; Adler, J.; Dunger, J.; Evans, R.; Green, T.; Pritzel, A.; Ronneberger, O.; Willmore, L.; Ballard, A.J.; Bambrick, J.; et al. Accurate structure prediction of biomolecular interactions with AlphaFold 3. Nature 2024, 630, 493–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Trains Set | Test Set | SVM Average Scores on Seq Features | TSVM Average Scores on Sequence Features | AT-TSVM Average F1 Scores (Using Validation Set) | AT-TSVM Average F1 Score (Using Active Learning) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1000(400c,600n) | 5000 | precision: 0.812 ± 0.0089 Recall: 0.6478 ± 0.0251 F1: 0.7202 ± 0.0135 ROC: 0.7738 ± 0.0090 | precision: 0.7649 ± 0.0074 Recall: 0.7155 ± 0.010 F1: 0.7393 ± 0.0082 ROC: 0.7844 ± 0.0065 | precision: 0.8253 ± 0.010 Recall: 0.7132 ± 0.014 F1: 0.7650 ± 0.0063 ROC: 0.8061 ± 0.0047 | precision: 0.8265 ± 0.0113 Recall: 0.7136 ± 0.0145 F1: 0.7661 ± 0.0071 ROC: 0.8068 ± 0.0053 |

| 2000(800c,1200n) | 5000 | precision: 0.8213 ± 0.0151 Recall: 0.6364 ± 0.0132 F1: 0.7179 ± 0.0072 ROC: 0.7717 ±0.0051 | precision: 0.7867 ± 0.0204 Recall: 0.6823 ± 0.0128 F1: 0.7333 ± 0.0056 ROC: 0.7802 ± 0.0045 | precision: 0.8354 ± 0.0158 Recall: 0.7051 ± 0.0119 F1: 0.7696 ± 0.0073 ROC: 0.8076 ± 0.0056 | precision: 0.8341 ± 0.0180 Recall: 0.7077 ± 0.0127 F1: 0.76617 ± 0.0055 ROC: 0.8088 ± 0.0068 |

| 1500(600c,900n) | 5000 | precision: 0.8221 ± 0.015 Recall: 0.6376 ± 0.0302 F1: 0.7206 ± 0.0163 ROC: 0.7739 ± 0.0105 | precision: 0.7744 ± 0.0078 Recall: 0.707 ± 0.0147 F1: 0.7406 ± 0.0080 ROC: 0.7852 ± 0.0061 | precision: 0.8296 ± 0.0188 Recall: 0.7245 ± 0.0083 F1: 0.7720 ± 0.0076 ROC: 0.8102 ± 0.0070 | precision: 0.8330 ± 0.0189 Recall: 0.7207 ± 0.0142 F1: 0.7702 ± 0.0090 ROC: 0.8110 ± 0.0073 |

| 2500(1000c,1500n) | 10,000 | precision: 0.8153 ± 0.0090 Recall: 0.6436 ± 0.0164 F1: 0.7218 ± 0.0067 ROC: 0.7740 ± 0.0060 | precision: 0.7840 ± 0.0150 Recall: 0.6951 ± 0.0133 F1: 0.7351 ± 0.0023 ROC: 0.7822 ± 0.0048 | precision: 0.8232 ± 0.0090 Recall: 0.7142 ± 0.0128 F1: 0.7670 ± 0.0049 ROC: 0.8067 ± 0.0053 | precision: 0.8236 ± 0.0088 Recall: 0.7141 ± 0.0136 F1: 0.7668 ± 0.0050 ROC: 0.8076 ± 0.0045 |

| 3000(1200c,1800n) | 10,000 | precision: 0.7912 ± 0.0642 Recall: 0.6880 ± 0.0876 F1: 0.7201 ± 0.0019 ROC: 0.7727 ± 0.0068 | precision: 0.7392 ± 0.0423 Recall: 0.7529 ± 0.0495 F1: 0.7397 ± 0.0040 ROC: 0.7841 ± 0.0048 | precision: 0.8002 ± 0.0523 Recall: 0.7756 ± 0.0614 F1: 0.7731 ± 0.0040 ROC: 0.8112 ± 0.006 | precision: 0.8002 ± 0.0524 Recall: 0.74484 ± 0.0435 F1: 0.7732 ± 0.0043 ROC: 0.8112 ± 0.0065 |

| 4000(1600c,1400n) | 10,000 | precision: 0.7818 ± 0.0055 Recall: 0.6941 ± 0.0080 F1: 0.7360 ± 0.0035 ROC: 0.7830 ± 0.0026 | precision: 0.7344 ± 0.0030 Recall: 0.7557 ± 0.0060 F1: 0.7454 ± 0.0030 ROC: 0.7865 ± 0.0024 | precision: 0.8012 ± 0.0092 Recall: 0.7686 ± 0.0138 F1: 0.7845 ± 0.0064 ROC: 0.8207 ± 0.0052 | precision: 0.7988 ± 0.0066 Recall: 0.7666 ± 0.0142 F1: 0.7842 ± 0.0064 ROC: 0.8205 ± 0.0051 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Almalki, B.; Sawhney, A.; Liao, L. AT-TSVM: Improving Transmembrane Protein Inter-Helical Residue Contact Prediction Using Active Transfer Transductive Support Vector Machines. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 10972. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262210972

Almalki B, Sawhney A, Liao L. AT-TSVM: Improving Transmembrane Protein Inter-Helical Residue Contact Prediction Using Active Transfer Transductive Support Vector Machines. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2025; 26(22):10972. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262210972

Chicago/Turabian StyleAlmalki, Bander, Aman Sawhney, and Li Liao. 2025. "AT-TSVM: Improving Transmembrane Protein Inter-Helical Residue Contact Prediction Using Active Transfer Transductive Support Vector Machines" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 26, no. 22: 10972. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262210972

APA StyleAlmalki, B., Sawhney, A., & Liao, L. (2025). AT-TSVM: Improving Transmembrane Protein Inter-Helical Residue Contact Prediction Using Active Transfer Transductive Support Vector Machines. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 26(22), 10972. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262210972