Safety and Potential Neuromodulatory Effects of Multi-Wall Carbon Nanotubes in Vertebrate and Invertebrate Animal Models In Vivo

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

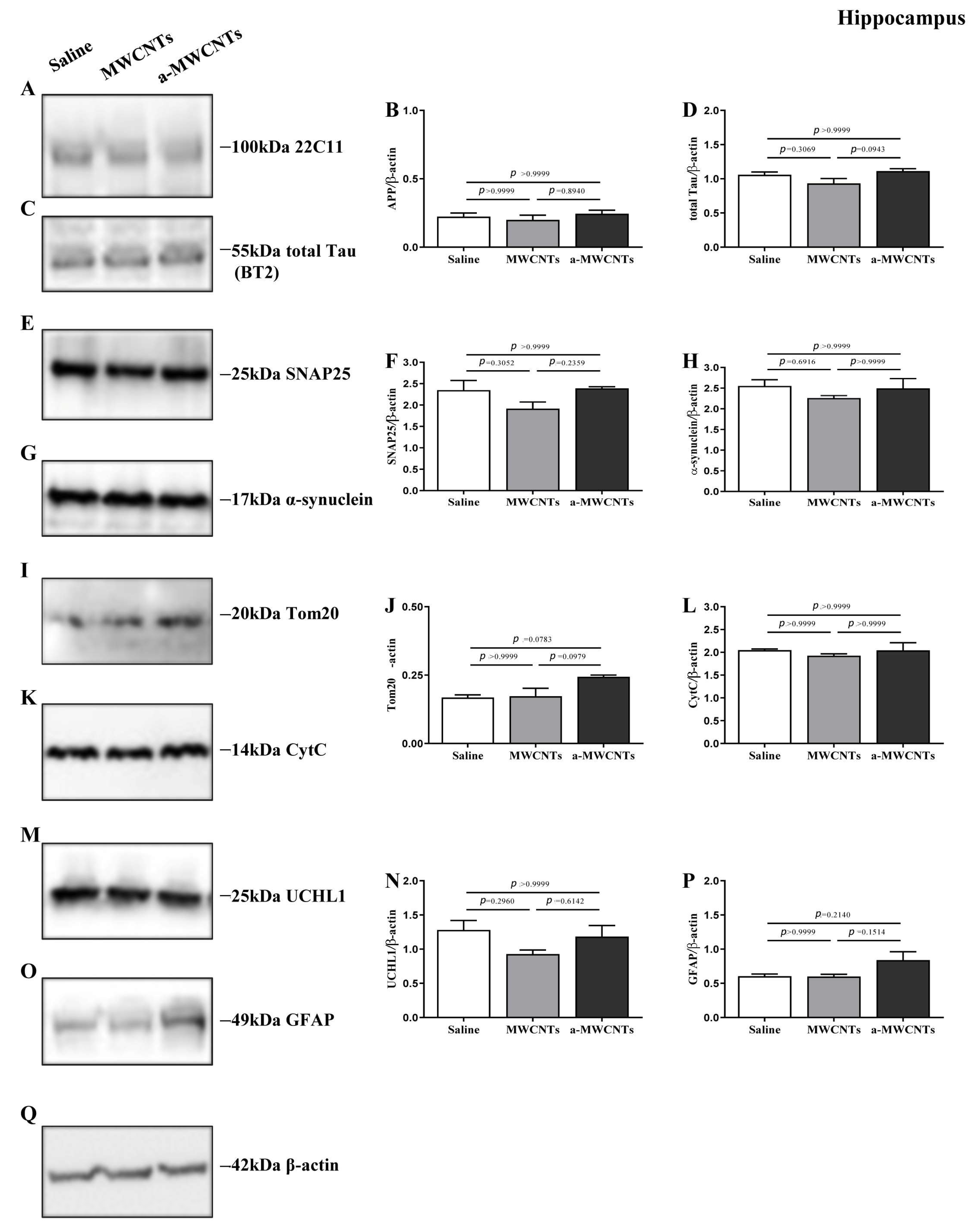

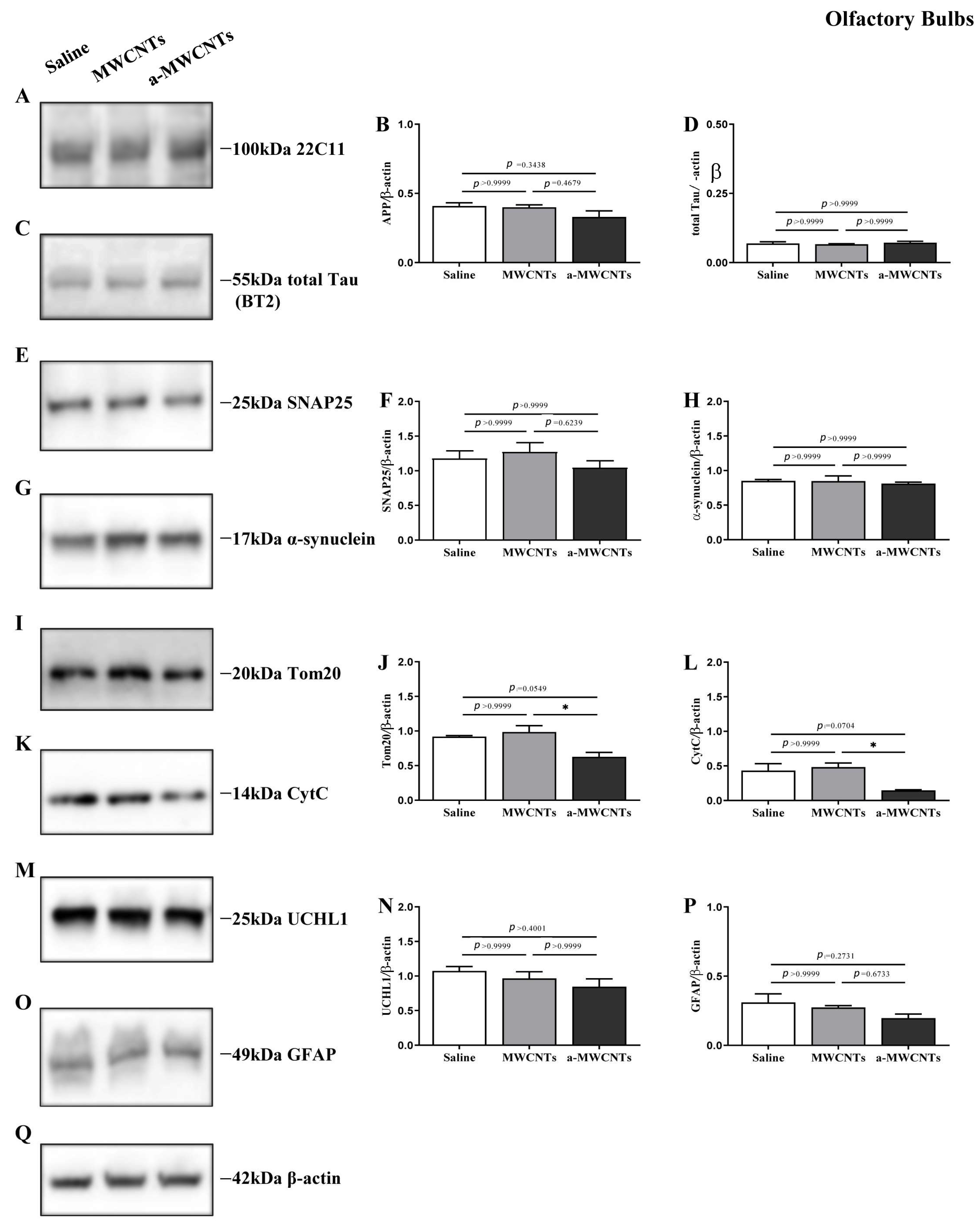

2.1. Impact of a-MWCNTs and MWCNTs on Rat Brain Physiology

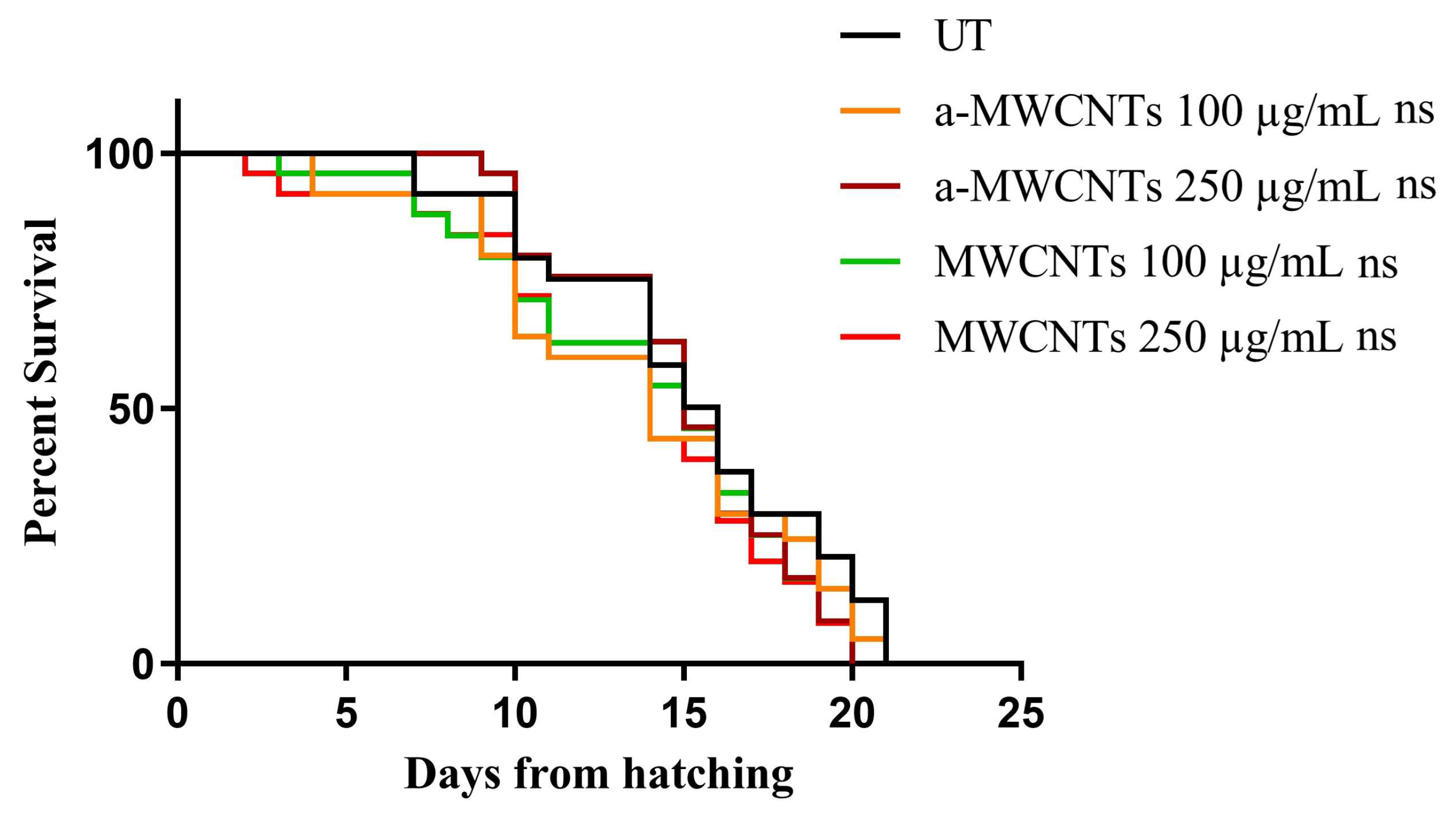

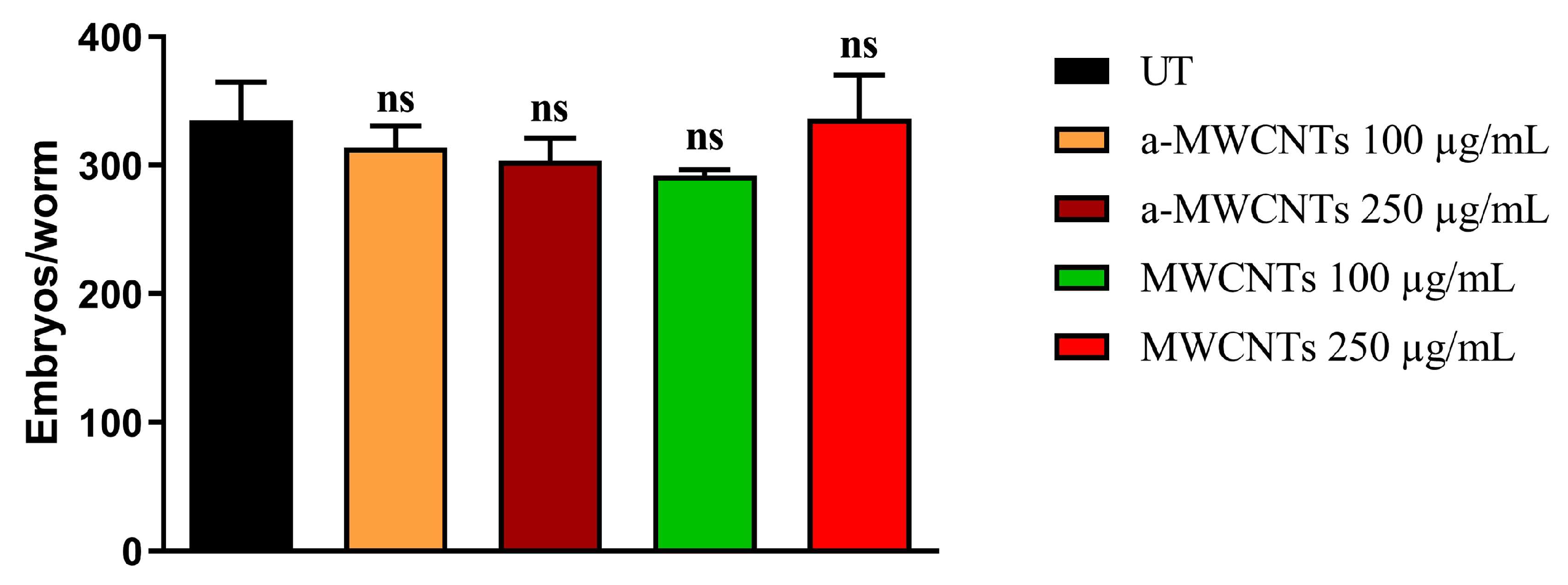

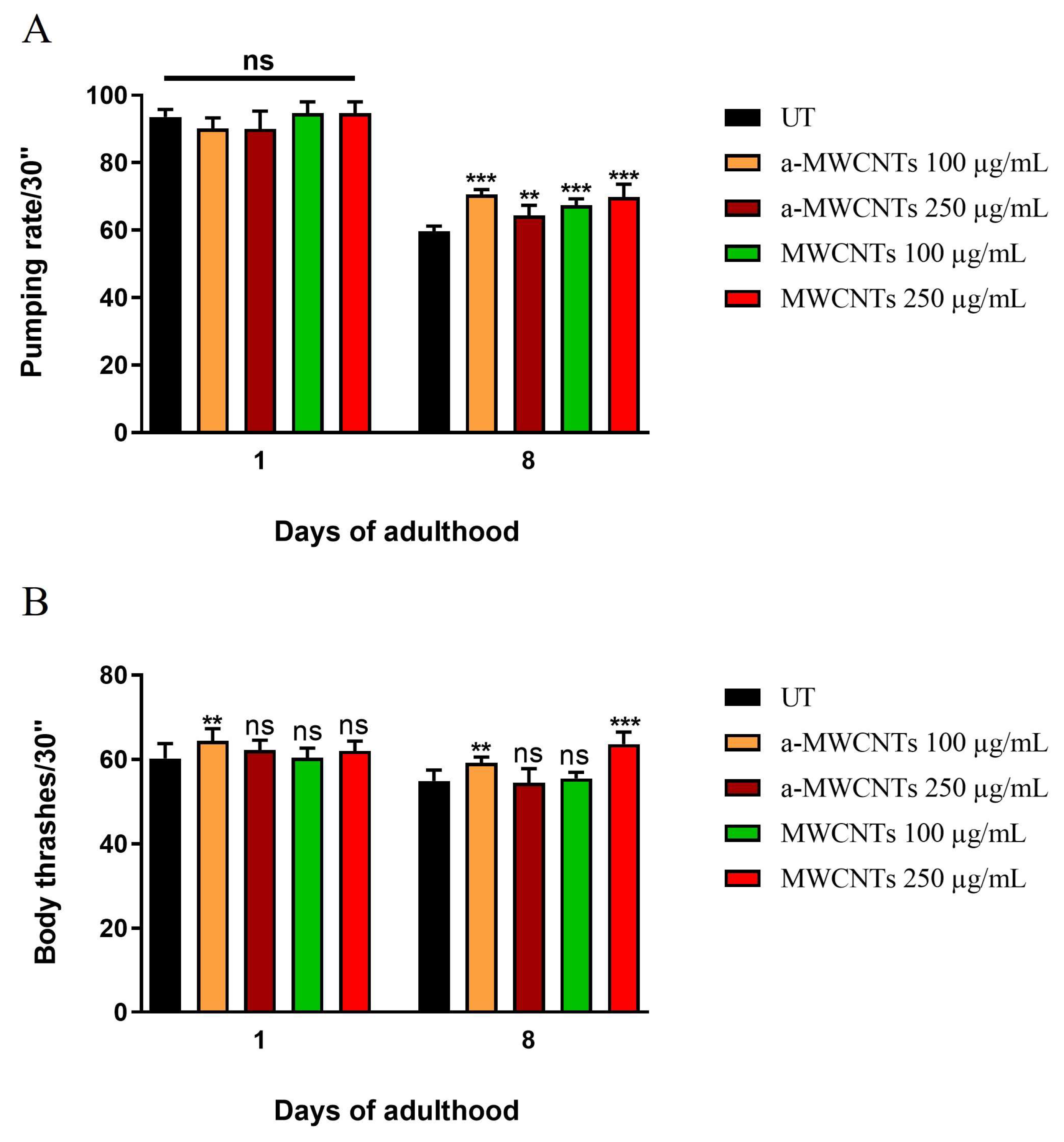

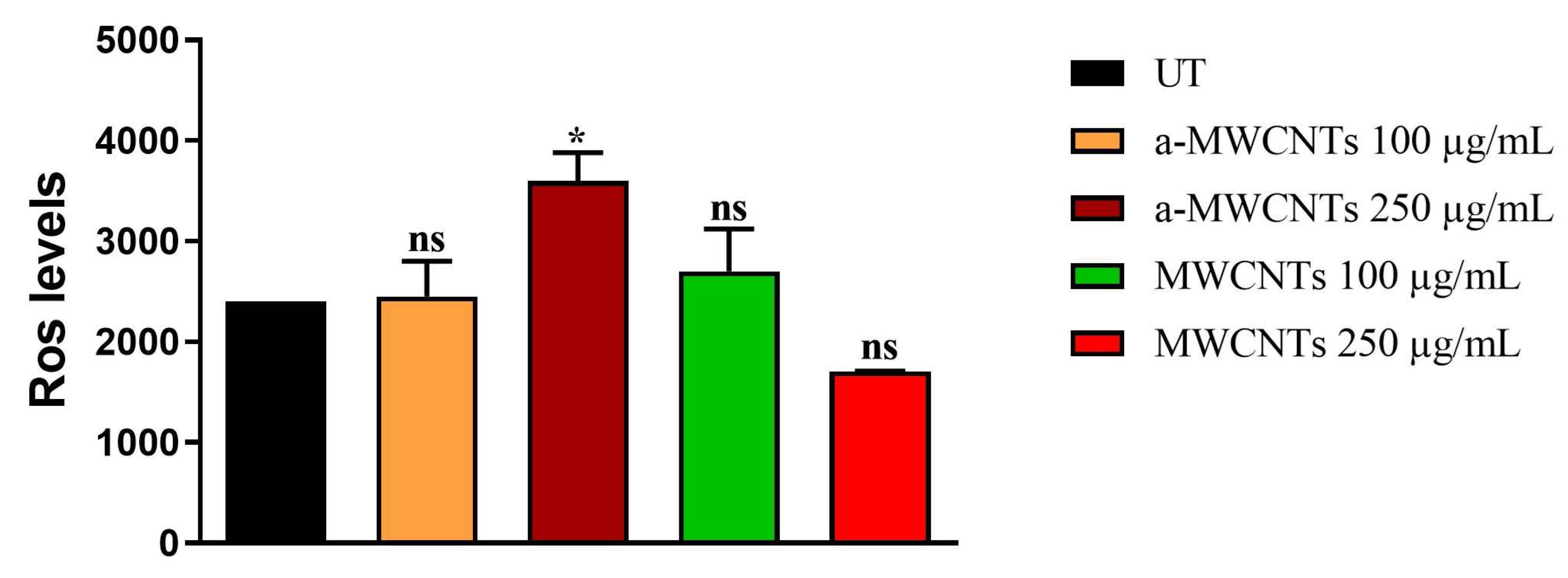

2.2. Impact of a-MWCNTs and MWCNTs on C. elegans Healthspan

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

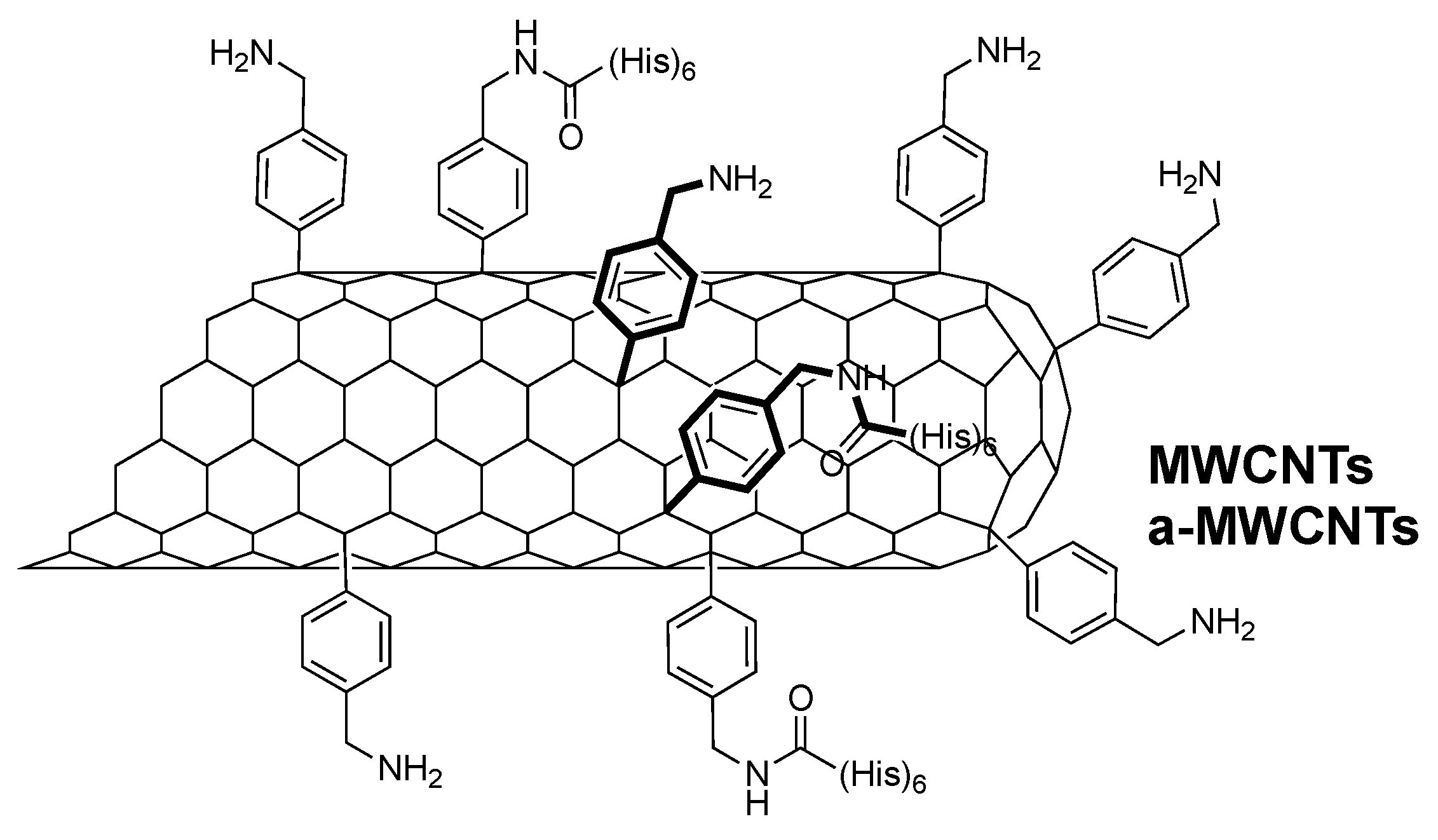

4.1. Carbon Nanotubes

4.2. Carbon Nanotube Functionalization

4.3. Electrochemical Characterization

4.4. Animals Handling and Intranasal Drug Delivery

4.5. Protein Cell Lysates Preparation

4.6. Western Blot Analysis and Semi-Quantitative Densitometry

4.7. C. elegans Lifespan and Fertility Assays

4.8. Aging Markers Analysis in C. elegans

4.9. Reactive Oxygen Species Evaluation in C. elegans

4.10. Data Management and Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Simon, J.; Flahaut, E.; Golzio, M. Overview of Carbon Nanotubes for Biomedical Applications. Materials 2019, 12, 624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sianipar, M.; Kim, S.H.; Khoiruddin, K.; Iskandar, F.; Wenten, I.G. Functionalized Carbon Nanotube (CNT) Membrane: Progress and Challenges. RSC Adv. 2017, 7, 51175–51198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rathinavel, S.; Priyadharshini, K.; Panda, D. A Review on Carbon Nanotube: An Overview of Synthesis, Properties, Functionalization, Characterization, and the Application. Mater. Sci. Eng. B 2021, 268, 115095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldrighi, M.; Trusel, M.; Tonini, R.; Giordani, S. Carbon Nanomaterials Interfacing with Neurons: An In Vivo Perspective. Front. Neurosci. 2016, 10, 250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abbasi, R.; Shineh, G.; Mobaraki, M.; Doughty, S.; Tayebi, L. Structural Parameters of Nanoparticles Affecting Their Toxicity for Biomedical Applications: A Review. J. Nanopart. Res. 2023, 25, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, S.; Tian, Y.; Ouyang, J.; Shen, Y.; Wang, X.; Luan, J. Carbon Nanomaterials for Drug Delivery and Tissue Engineering. Front. Chem. 2022, 10, 990362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henna, T.K.; Raphey, V.R.; Sankar, R.; Ameena Shirin, V.K.; Gangadharappa, H.V.; Pramod, K. Carbon Nanostructures: The Drug and the Delivery System for Brain Disorders. Int. J. Pharm. 2020, 587, 119701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, N.; Gupta, S.M.; Sharma, S.K. Carbon Nanotubes: Synthesis, Properties and Engineering Applications. Carbon Lett. 2019, 29, 419–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lohan, S.; Raza, K.; Mehta, S.K.; Bhatti, G.K.; Saini, S.; Singh, B. Anti-Alzheimer’s Potential of Berberine Using Surface Decorated Multi-Walled Carbon Nanotubes: A Preclinical Evidence. Int. J. Pharm. 2017, 530, 263–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ménard-Moyon, C.; Kostarelos, K.; Prato, M.; Bianco, A. Functionalized Carbon Nanotubes for Probing and Modulating Molecular Functions. Chem. Biol. 2010, 17, 107–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teleanu, D.M.; Chircov, C.; Grumezescu, A.M.; Volceanov, A.; Teleanu, R.I. Blood-Brain Delivery Methods Using Nanotechnology. Pharmaceutics 2018, 10, 269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, C.; Zhang, Y.; Guo, W.; Liang, X.-J. Biomimetic Carbon Nanotubes for Neurological Disease Therapeutics as Inherent Medication. Acta Pharm. Sin. B 2020, 10, 239–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cellot, G.; Cilia, E.; Cipollone, S.; Rancic, V.; Sucapane, A.; Giordani, S.; Gambazzi, L.; Markram, H.; Grandolfo, M.; Scaini, D.; et al. Carbon Nanotubes Might Improve Neuronal Performance by Favouring Electrical Shortcuts. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2009, 4, 126–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Jamal, K.T.; Gherardini, L.; Bardi, G.; Nunes, A.; Guo, C.; Bussy, C.; Herrero, M.A.; Bianco, A.; Prato, M.; Kostarelos, K.; et al. Functional Motor Recovery from Brain Ischemic Insult by Carbon Nanotube-Mediated siRNA Silencing. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2011, 108, 10952–10957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.J.; Park, J.; Yoon, O.J.; Kim, H.W.; Lee, D.Y.; Kim, D.H.; Lee, W.B.; Lee, N.-E.; Bonventre, J.V.; Kim, S.S. Amine-Modified Single-Walled Carbon Nanotubes Protect Neurons from Injury in a Rat Stroke Model. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2011, 6, 121–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, D.; Alizadeh, D.; Zhang, L.; Liu, W.; Farrukh, O.; Manuel, E.; Diamond, D.J.; Badie, B. Carbon Nanotubes Enhance CpG Uptake and Potentiate Antiglioma Immunity. Clin. Cancer Res. 2011, 17, 771–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burke, A.R.; Singh, R.N.; Carroll, D.L.; Wood, J.C.S.; D’Agostino, R.B.; Ajayan, P.M.; Torti, F.M.; Torti, S.V. The Resistance of Breast Cancer Stem Cells to Conventional Hyperthermia and Their Sensitivity to Nanoparticle-Mediated Photothermal Therapy. Biomaterials 2012, 33, 2961–2970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, R.; Torti, S.V. Carbon Nanotubes in Hyperthermia Therapy. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2013, 65, 2045–2060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eldridge, B.N.; Bernish, B.W.; Fahrenholtz, C.D.; Singh, R. Photothermal Therapy of Glioblastoma Multiforme Using Multiwalled Carbon Nanotubes Optimized for Diffusion in Extracellular Space. ACS Biomater. Sci. Eng. 2016, 2, 963–976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, T.; Fang, X.; Chen, M.-T.; Wang, W.; Ferreira, R.; Jhaveri, N.; Gundersen, M.; Zhou, C.; Pagnini, P.; Hofman, F.M.; et al. Sequential Administration of Carbon Nanotubes and Near-Infrared Radiation for the Treatment of Gliomas. Front. Oncol. 2014, 4, 180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.-H.; Chiou, S.-H.; Chou, C.-P.; Chen, Y.-C.; Huang, Y.-J.; Peng, C.-A. Photothermolysis of Glioblastoma Stem-like Cells Targeted by Carbon Nanotubes Conjugated with CD133 Monoclonal Antibody. Nanomed. Nanotechnol. Biol. Med. 2011, 7, 69–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gupta, B.; Sharma, P.K.; Malviya, R. Carbon Nanotubes for Targeted Therapy: Safety, Efficacy, Feasibility andRegulatory Aspects. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2024, 30, 81–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eldridge, B.N.; Xing, F.; Fahrenholtz, C.D.; Singh, R.N. Evaluation of Multiwalled Carbon Nanotube Cytotoxicity in Cultures of Human Brain Microvascular Endothelial Cells Grown on Plastic or Basement Membrane. Toxicol. In Vitr. 2017, 41, 223–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burke, A.R.; Singh, R.N.; Carroll, D.L.; Owen, J.D.; Kock, N.D.; D’Agostino, R.; Torti, F.M.; Torti, S.V. Determinants of the Thrombogenic Potential of Multiwalled Carbon Nanotubes. Biomaterials 2011, 32, 5970–5978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kafa, H.; Wang, J.T.-W.; Rubio, N.; Venner, K.; Anderson, G.; Pach, E.; Ballesteros, B.; Preston, J.E.; Abbott, N.J.; Al-Jamal, K.T. The Interaction of Carbon Nanotubes with an in Vitro Blood-Brain Barrier Model and Mouse Brain in Vivo. Biomaterials 2015, 53, 437–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, L.; Pint, C.L.; Arikawa, T.; Takeya, K.; Kawayama, I.; Tonouchi, M.; Hauge, R.H.; Kono, J. Broadband Terahertz Polarizers with Ideal Performance Based on Aligned Carbon Nanotube Stacks. Nano Lett. 2012, 12, 787–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.T.-W.; Rubio, N.; Kafa, H.; Venturelli, E.; Fabbro, C.; Ménard-Moyon, C.; Da Ros, T.; Sosabowski, J.K.; Lawson, A.D.; Robinson, M.K.; et al. Kinetics of Functionalised Carbon Nanotube Distribution in Mouse Brain after Systemic Injection: Spatial to Ultra-Structural Analyses. J. Control. Release 2016, 224, 22–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaillard, C.; Cellot, G.; Li, S.; Toma, F.M.; Dumortier, H.; Spalluto, G.; Cacciari, B.; Prato, M.; Ballerini, L.; Bianco, A. Carbon Nanotubes Carrying Cell-Adhesion Peptides Do Not Interfere with Neuronal Functionality. Adv. Mater. 2009, 21, 2903–2908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mattson, M.P.; Haddon, R.C.; Rao, A.M. Molecular Functionalization of Carbon Nanotubes and Use as Substrates for Neuronal Growth. J. Mol. Neurosci. 2000, 14, 175–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, N.; Zhang, X.; Song, Q.; Su, R.; Zhang, Q.; Kong, T.; Liu, L.; Jin, G.; Tang, M.; Cheng, G. The Promotion of Neurite Sprouting and Outgrowth of Mouse Hippocampal Cells in Culture by Graphene Substrates. Biomaterials 2011, 32, 9374–9382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hopper, A.P.; Dugan, J.M.; Gill, A.A.; Fox, O.J.L.; May, P.W.; Haycock, J.W.; Claeyssens, F. Amine Functionalized Nanodiamond Promotes Cellular Adhesion, Proliferation and Neurite Outgrowth. Biomed. Mater. 2014, 9, 045009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bardi, G.; Nunes, A.; Gherardini, L.; Bates, K.; Al-Jamal, K.T.; Gaillard, C.; Prato, M.; Bianco, A.; Pizzorusso, T.; Kostarelos, K. Functionalized Carbon Nanotubes in the Brain: Cellular Internalization and Neuroinflammatory Responses. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e80964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bussy, C.; Al-Jamal, K.T.; Boczkowski, J.; Lanone, S.; Prato, M.; Bianco, A.; Kostarelos, K. Microglia Determine Brain Region-Specific Neurotoxic Responses to Chemically Functionalized Carbon Nanotubes. ACS Nano 2015, 9, 7815–7830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nunes, A.; Bussy, C.; Gherardini, L.; Meneghetti, M.; Herrero, M.A.; Bianco, A.; Prato, M.; Pizzorusso, T.; Al-Jamal, K.T.; Kostarelos, K. In Vivo Degradation of Functionalized Carbon Nanotubes After Stereotactic Administration in The Brain Cortex. Nanomedicine 2012, 7, 1485–1494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nunes, A.; Al-Jamal, K.; Nakajima, T.; Hariz, M.; Kostarelos, K. Application of Carbon Nanotubes in Neurology: Clinical Perspectives and Toxicological Risks. Arch. Toxicol. 2012, 86, 1009–1020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rhaman, M.; Islam, R.; Akash, S.; Mim, M.; Alam, N.; Nepovimova, E.; Valis, M.; Kuca, K.; Sharma, R. Exploring the Role of Nanomedicines for the Therapeutic Approach of Central Nervous System Dysfunction: At a Glance. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2022, 10, 989471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elsori, D.; Rashid, G.; Khan, N.A.; Sachdeva, P.; Jindal, R.; Kayenat, F.; Sachdeva, B.; Kamal, M.A.; Babker, A.M.; Fahmy, S.A. Nanotube Breakthroughs: Unveiling the Potential of Carbon Nanotubes as a Dual Therapeutic Arsenal for Alzheimer’s Disease and Brain Tumors. Front. Oncol. 2023, 13, 1265347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-zharani, M.; Hasnain, M.S.; Al-Eissa, M.S.; Alqahtani, R.A. Novel Drug Delivery to the Brain for Neurodegenerative Disorder Treatment Using Carbon Nanotubes. J. King Saud Univ. Sci. 2024, 36, 103513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiorito, S.; Monthioux, M.; Psaila, R.; Pierimarchi, P.; Zonfrillo, M.; D’Emilia, E.; Grimaldi, S.; Lisi, A.; Béguin, F.; Almairac, R.; et al. Evidence for Electro-Chemical Interactions between Multi-Walled Carbon Nanotubes and Human Macrophages. Carbon 2009, 47, 2789–2804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiorito, S.; Russier, J.; Salemme, A.; Soligo, M.; Manni, L.; Krasnowska, E.; Bonnamy, S.; Flahaut, E.; Serafino, A.; Togna, G.I.; et al. Switching on Microglia with Electro-Conductive Multi Walled Carbon Nanotubes. Carbon 2018, 129, 572–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soligo, M.; Felsani, F.M.; Da Ros, T.; Bosi, S.; Pellizzoni, E.; Bruni, S.; Isopi, J.; Marcaccio, M.; Manni, L.; Fiorito, S. Distribution in the Brain and Possible Neuroprotective Effects of Intranasally Delivered Multi-Walled Carbon Nanotubes. Nanoscale Adv. 2021, 3, 418–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Redwine, J.M.; Evans, C.F. Markers of Central Nervous System Glia and Neurons In Vivo During Normal and Pathological Conditions. In Protective and Pathological Immune Responses in the CNS; Dietzschold, B., Richt, J.A., Eds.; Current Topics in Microbiology and Immunology; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2002; Volume 265, pp. 119–140. ISBN 978-3-642-07655-8. [Google Scholar]

- Poudel, P.; Park, S. Recent Advances in the Treatment of Alzheimer’s Disease Using Nanoparticle-Based Drug Delivery Systems. Pharmaceutics 2022, 14, 835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roghani, A.K.; Garcia, R.I.; Roghani, A.; Reddy, A.; Khemka, S.; Reddy, R.P.; Pattoor, V.; Jacob, M.; Reddy, P.H.; Sehar, U. Treating Alzheimer’s Disease Using Nanoparticle-Mediated Drug Delivery Strategies/Systems. Ageing Res. Rev. 2024, 97, 102291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilar, G.; Suhandi, C.; Wathoni, N.; Fukunaga, K.; Kawahata, I. Nanoparticle-Based Drug Delivery Systems Enhance Treatment of Cognitive Defects. Int. J. Nanomed. 2024, 19, 11357–11378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, T.; Xu, H.; Liang, X.; Tang, M. Caenorhabditis Elegans as a Complete Model Organism for Biosafety Assessments of Nanoparticles. Chemosphere 2019, 221, 708–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hüttemann, M.; Pecina, P.; Rainbolt, M.; Sanderson, T.H.; Kagan, V.E.; Samavati, L.; Doan, J.W.; Lee, I. The Multiple Functions of Cytochrome c and Their Regulation in Life and Death Decisions of the Mammalian Cell: From Respiration to Apoptosis. Mitochondrion 2011, 11, 369–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Von Ahsen, O.; Waterhouse, N.J.; Kuwana, T.; Newmeyer, D.D.; Green, D.R. The ‘Harmless’ Release of Cytochrome c. Cell Death Differ. 2000, 7, 1192–1199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serafino, A.; Togna, A.R.; Togna, G.I.; Lisi, A.; Ledda, M.; Grimaldi, S.; Russier, J.; Andreola, F.; Monthioux, M.; Béguin, F.; et al. Highly Electroconductive Multiwalled Carbon Nanotubes as Potentially Useful Tools for Modulating Calcium Balancing in Biological Environments. Nanomed. Nanotechnol. Biol. Med. 2012, 8, 299–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naletova, I.; Satriano, C.; Pietropaolo, A.; Gianì, F.; Pandini, G.; Triaca, V.; Amadoro, G.; Latina, V.; Calissano, P.; Travaglia, A.; et al. The Copper(II)-Assisted Connection between NGF and BDNF by Means of Nerve Growth Factor-Mimicking Short Peptides. Cells 2019, 8, 301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Travaglia, A.; Arena, G.; Fattorusso, R.; Isernia, C.; La Mendola, D.; Malgieri, G.; Nicoletti, V.G.; Rizzarelli, E. The Inorganic Perspective of Nerve Growth Factor: Interactions of Cu2+ and Zn2+ with the N-Terminus Fragment of Nerve Growth Factor Encompassing the Recognition Domain of the TrkA Receptor. Chem. Eur. J. 2011, 17, 3726–3738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanaji, S.; Iwahashi, J.; Kida, Y.; Sakaguchi, M.; Mihara, K. Characterization of the Signal That Directs Tom20 to the Mitochondrial Outer Membrane. J. Cell Biol. 2000, 151, 277–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clemente-Suárez, V.; Redondo-Flórez, L.; Beltrán-Velasco, A.; Ramos-Campo, D.; Belinchón-deMiguel, P.; Martinez-Guardado, I.; Dalamitros, A.; Yáñez-Sepúlveda, R.; Martín-Rodríguez, A.; Tornero-Aguilera, J. Mitochondria and Brain Disease: A Comprehensive Review of Pathological Mechanisms and Therapeutic Opportunities. Biomedicines 2023, 11, 2488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerra-Castellano, A.; Márquez, I.; Pérez-Mejías, G.; Díaz-Quintana, A.; De La Rosa, M.A.; Díaz-Moreno, I. Post-Translational Modifications of Cytochrome c in Cell Life and Disease. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 8483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kann, O.; Kovács, R. Mitochondria and Neuronal Activity. Am. J. Physiol.-Cell Physiol. 2007, 292, C641–C657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hansson Petersen, C.A.; Alikhani, N.; Behbahani, H.; Wiehager, B.; Pavlov, P.F.; Alafuzoff, I.; Leinonen, V.; Ito, A.; Winblad, B.; Glaser, E.; et al. The Amyloid β-Peptide Is Imported into Mitochondria via the TOM Import Machinery and Localized to Mitochondrial Cristae. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2008, 105, 13145–13150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fujita, K.; Obara, S.; Maru, J.; Endoh, S. Cytotoxicity Profiles of Multi-Walled Carbon Nanotubes with Different Physico-Chemical Properties. Toxicol. Mech. Methods 2020, 30, 477–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Battigelli, A.; Russier, J.; Venturelli, E.; Fabbro, C.; Petronilli, V.; Bernardi, P.; Da Ros, T.; Prato, M.; Bianco, A. Peptide-Based Carbon Nanotubes for Mitochondrial Targeting. Nanoscale 2013, 5, 9110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ficociello, G.; Salemme, A.; Uccelletti, D.; Fiorito, S.; Togna, A.R.; Vallan, L.; González-Domínguez, J.M.; Da Ros, T.; Francisci, S.; Montanari, A. Evaluation of the Efficacy of Carbon Nanotubes for Delivering Peptides into Mitochondria. RSC Adv. 2016, 6, 67232–67241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snyder, R.J.; Verhein, K.C.; Vellers, H.L.; Burkholder, A.B.; Garantziotis, S.; Kleeberger, S.R. Multi-Walled Carbon Nanotubes Upregulate Mitochondrial Gene Expression and Trigger Mitochondrial Dysfunction in Primary Human Bronchial Epithelial Cells. Nanotoxicology 2019, 13, 1344–1361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delpeux-Ouldriane, S.; Szostak, K.; Frackowiak, E.; Béguin, F. Annealing of Template Nanotubes to Well-Graphitized Multi-Walled Carbon Nanotubes. Carbon 2006, 44, 814–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahr, J.L.; Tour, J.M. Highly Functionalized Carbon Nanotubes Using in Situ Generated Diazonium Compounds. Chem. Mater. 2001, 13, 3823–3824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mobbili, G.; Crucianelli, E.; Barbon, A.; Marcaccio, M.; Pisani, M.; Dalzini, A.; Ussano, E.; Bortolus, M.; Stipa, P.; Astolfi, P. Liponitroxides: EPR Study and Their Efficacy as Antioxidants in Lipid Membranes. RSC Adv. 2015, 5, 98955–98966, Correction in RSC Adv. 2019, 9, 32721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, G.; Lu, C.; Su, F. Sorption of Divalent Metal Ions from Aqueous Solution by Carbon Nanotubes: A Review. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2007, 58, 224–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latina, V.; Giacovazzo, G.; Calissano, P.; Atlante, A.; La Regina, F.; Malerba, F.; Dell’Aquila, M.; Stigliano, E.; Balzamino, B.O.; Micera, A.; et al. Tau Cleavage Contributes to Cognitive Dysfunction in Strepto-Zotocin-Induced Sporadic Alzheimer’s Disease (sAD) Mouse Model. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 12158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mengoni, B.; Armeli, F.; Schifano, E.; Prencipe, S.A.; Pompa, L.; Sciubba, F.; Brasili, E.; Giampaoli, O.; Mura, F.; Reverberi, M.; et al. In Vitro and In Vivo Antioxidant and Immune Stimulation Activity of Wheat Product Extracts. Nutrients 2025, 17, 302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schifano, E.; Tomassini, A.; Preziosi, A.; Montes, J.; Aureli, W.; Mancini, P.; Miccheli, A.; Uccelletti, D. Leuconostoc Mesenteroides Strains Isolated from Carrots Show Probiotic Features. Microorganisms 2021, 9, 2290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Latina, V.; Soligo, M.; Da Ros, T.; Schifano, E.; Guarnieri, M.; Montanari, A.; Amadoro, G.; Fiorito, S. Safety and Potential Neuromodulatory Effects of Multi-Wall Carbon Nanotubes in Vertebrate and Invertebrate Animal Models In Vivo. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 10844. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262210844

Latina V, Soligo M, Da Ros T, Schifano E, Guarnieri M, Montanari A, Amadoro G, Fiorito S. Safety and Potential Neuromodulatory Effects of Multi-Wall Carbon Nanotubes in Vertebrate and Invertebrate Animal Models In Vivo. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2025; 26(22):10844. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262210844

Chicago/Turabian StyleLatina, Valentina, Marzia Soligo, Tatiana Da Ros, Emily Schifano, Marco Guarnieri, Arianna Montanari, Giuseppina Amadoro, and Silvana Fiorito. 2025. "Safety and Potential Neuromodulatory Effects of Multi-Wall Carbon Nanotubes in Vertebrate and Invertebrate Animal Models In Vivo" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 26, no. 22: 10844. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262210844

APA StyleLatina, V., Soligo, M., Da Ros, T., Schifano, E., Guarnieri, M., Montanari, A., Amadoro, G., & Fiorito, S. (2025). Safety and Potential Neuromodulatory Effects of Multi-Wall Carbon Nanotubes in Vertebrate and Invertebrate Animal Models In Vivo. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 26(22), 10844. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262210844