Identification of Small Molecules as Zika Virus Entry Inhibitors

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Virtual Screening for Identification of Small Molecules

2.2. Evaluation of the Anti-ZIKV Inhibitory Activity of Selected Compounds from Virtual Screening

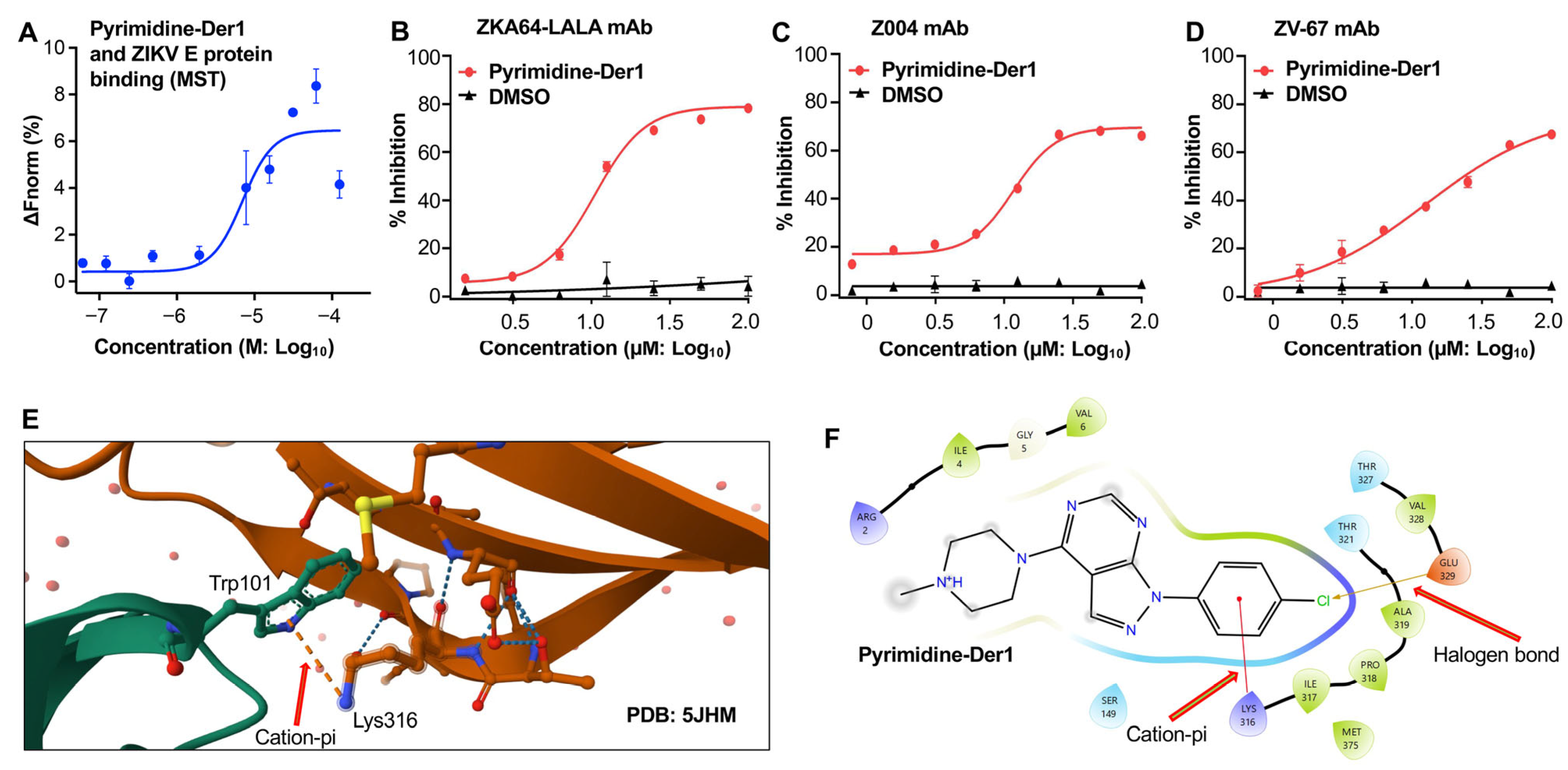

2.3. Characterization of Pyrimidine-Der1 for Binding Affinity and Blockage of Antibody Binding

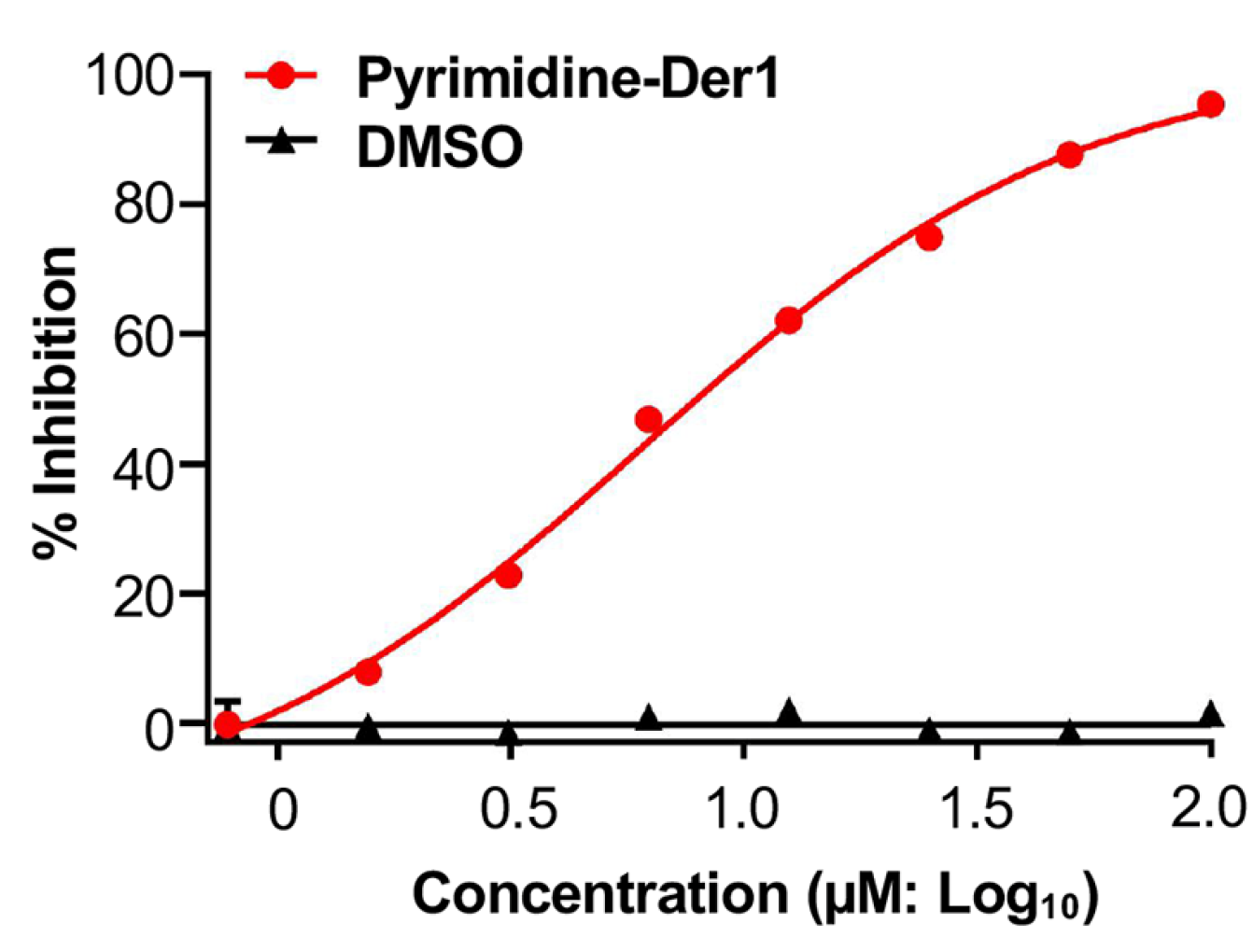

2.4. Identification of Pyrimidine-Der1 as an Effective ZIKV Entry Inhibitor

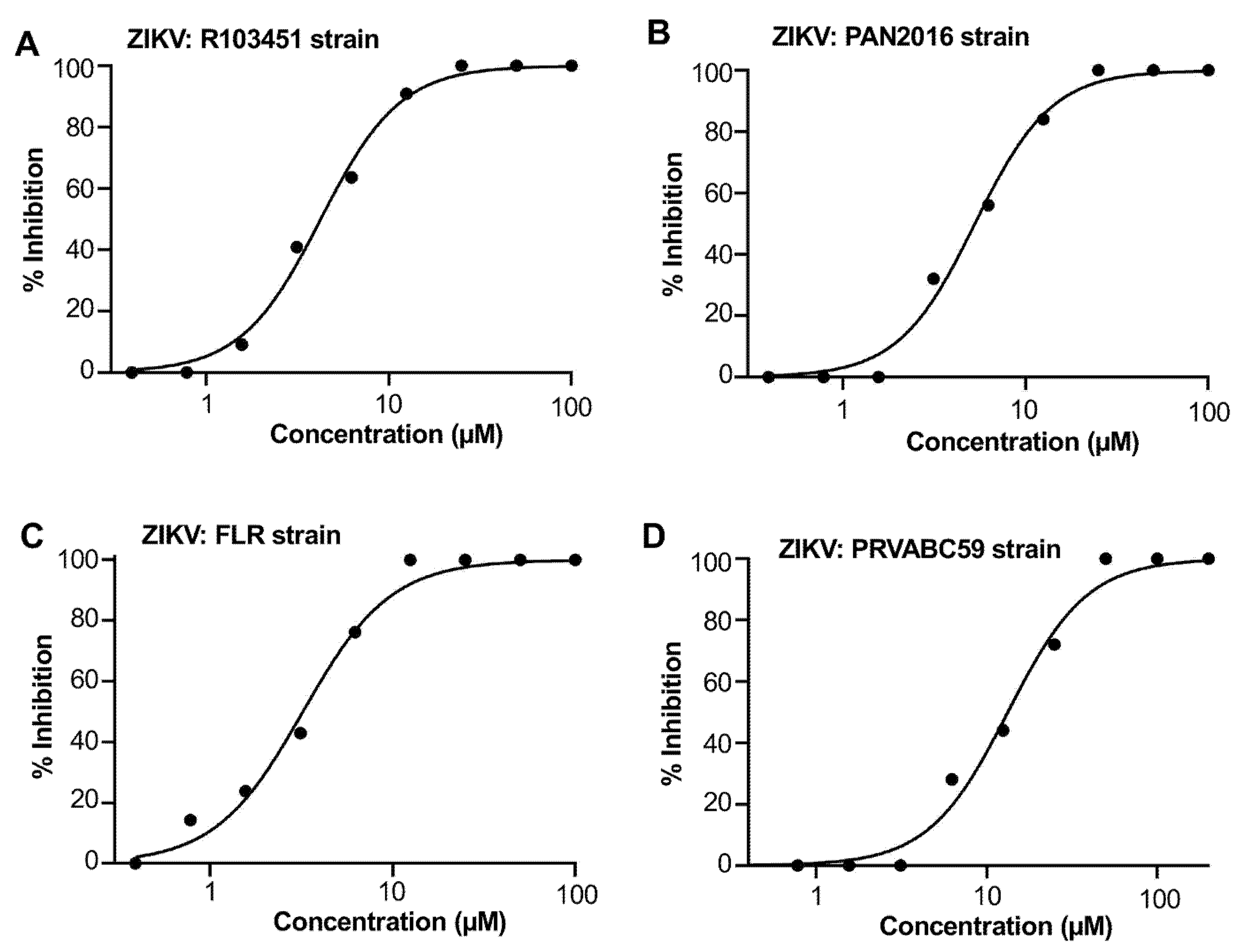

2.5. Pyrimidine-Der1 Demonstrated Broad Anti-ZIKV Inhibitory Activity

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Cells and Viruses

4.2. Virtual Screening Using GLIDE-Based Docking

4.3. Reporter ZIKV Inhibition Assay

4.4. Plaque Inhibition Assay

4.5. Determination of In Vitro Cytotoxicity

4.6. ELISA

4.7. Time of Addition Experiment

4.8. MST Measurement of Binding Affinity

4.9. Statistical Analysis

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CC50 | 50% cytotoxicity concentration |

| CZS | Congenital Zika syndrome |

| E | Envelope |

| EDI-EDIII | Envelope domains I-III |

| ELISA | Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay |

| FBS | Fetal bovine serum |

| HRP | Horseradish peroxidase |

| IC50 | 50% inhibitory concentration |

| KD | Dissociation constant |

| mAb | Monoclonal antibody |

| MEM | Eagle’s minimum essential medium |

| MST | Microscale thermophoresis |

| NS proteins | Non-structural proteins |

| PFU | Plaque-forming unit |

| SI | Selectivity index |

| ZIKV | Zika virus |

| ZIKV-R | Reporter ZIKV |

References

- Dick, G.W.A.; Kitchen, S.F.; Haddow, A.J. Zika Virus (I). Isolations and Serological Specificity. Trans. R. Soc. Trop. Med. Hyg. 1952, 46, 509–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duffy, M.R.; Chen, T.-H.; Hancock, W.T.; Powers, A.M.; Kool, J.L.; Lanciotti, R.S.; Pretrick, M.; Marfel, M.; Holzbauer, S.; Dubray, C.; et al. Zika Virus Outbreak on Yap Island, Federated States of Micronesia. N. Engl. J. Med. 2009, 360, 2536–2543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musso, D.; Nilles, E.J.; Cao-Lormeau, V.-M. Rapid Spread of Emerging Zika Virus in the Pacific Area. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2014, 20, O595–O596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Etienne, C.; dos Santos, T.; Espinal, M.A. Keynote Address (November 2016): Zika Virus Disease in the Americas: A Storm in the Making. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2017, 97, 16–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Saeed, H.; Rehman, G.; Mehmood Qadri, H.; Sohail, A.; Ul Haq, A.; Sadiq, H.Z.; Yasin, S.; Khalid Rana, M.A. Neurological Manifestations of Zika Virus Infection: An Updated Review of the Existing Literature. Cureus 2025, 17, e80960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marbán-Castro, E.; Goncé, A.; Fumadó, V.; Romero-Acevedo, L.; Bardají, A. Zika Virus Infection in Pregnant Women and Their Children: A Review. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 2021, 265, 162–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delaney, A. Population-Based Surveillance of Birth Defects Potentially Related to Zika Virus Infection—15 States and U. S. Territories, 2016. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2018, 67, 91–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marrs, C.; Olson, G.; Saade, G.; Hankins, G.; Wen, T.; Patel, J.; Weaver, S. Zika Virus and Pregnancy: A Review of the Literature and Clinical Considerations. Am. J. Perinatol. 2016, 33, 625–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zika Epidemiology Update—May 2024. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/m/item/zika-epidemiology-update-may-2024 (accessed on 16 August 2025).

- Ukoaka, B.M.; Okesanya, O.J.; Daniel, F.M.; Ahmed, M.M.; Udam, N.G.; Wagwula, P.M.; Adigun, O.A.; Udoh, R.A.; Peter, I.G.; Lawal, H. Updated WHO List of Emerging Pathogens for a Potential Future Pandemic: Implications for Public Health and Global Preparedness. Infez. Med. 2024, 32, 463–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boyer, S.; Calvez, E.; Chouin-Carneiro, T.; Diallo, D.; Failloux, A.-B. An Overview of Mosquito Vectors of Zika Virus. Microbes Infect. 2018, 20, 646–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gregory, C.J.; Oduyebo, T.; Brault, A.C.; Brooks, J.T.; Chung, K.-W.; Hills, S.; Kuehnert, M.J.; Mead, P.; Meaney-Delman, D.; Rabe, I.; et al. Modes of Transmission of Zika Virus. J. Infect. Dis. 2017, 216, S875–S883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miner, J.J.; Diamond, M.S. Zika Virus Pathogenesis and Tissue Tropism. Cell Host Microbe 2017, 21, 134–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Masmejan, S.; Musso, D.; Vouga, M.; Pomar, L.; Dashraath, P.; Stojanov, M.; Panchaud, A.; Baud, D. Zika Virus. Pathogens 2020, 9, 898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pielnaa, P.; Al-Saadawe, M.; Saro, A.; Dama, M.F.; Zhou, M.; Huang, Y.; Huang, J.; Xia, Z. Zika Virus-Spread, Epidemiology, Genome, Transmission Cycle, Clinical Manifestation, Associated Challenges, Vaccine and Antiviral Drug Development. Virology 2020, 543, 34–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valente, A.P.; Moraes, A.H. Zika Virus Proteins at an Atomic Scale: How Does Structural Biology Help Us to Understand and Develop Vaccines and Drugs against Zika Virus Infection? J. Venom. Anim. Toxins Trop. Dis. 2019, 25, e20190013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sirohi, D.; Chen, Z.; Sun, L.; Klose, T.; Pierson, T.C.; Rossmann, M.G.; Kuhn, R.J. The 3.8 Å Resolution Cryo-EM Structure of Zika Virus. Science 2016, 352, 467–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, L.; Song, J.; Lu, X.; Deng, Y.-Q.; Musyoki, A.M.; Cheng, H.; Zhang, Y.; Yuan, Y.; Song, H.; Haywood, J.; et al. Structures of the Zika Virus Envelope Protein and its Complex with a Flavivirus Broadly Protective Antibody. Cell Host Microbe 2016, 19, 696–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agrelli, A.; de Moura, R.R.; Crovella, S.; Brandão, L.A.C. ZIKA Virus Entry Mechanisms in Human Cells. Infect. Genet. Evol. 2019, 69, 22–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Côrtes, N.; Lira, A.; Prates-Syed, W.; Dinis Silva, J.; Vuitika, L.; Cabral-Miranda, W.; Durães-Carvalho, R.; Balan, A.; Cabral-Marques, O.; Cabral-Miranda, G. Integrated Control Strategies for Dengue, Zika, and Chikungunya Virus Infections. Front. Immunol. 2023, 14, 1281667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pattnaik, A.; Sahoo, B.R.; Pattnaik, A.K. Current Status of Zika Virus Vaccines: Successes and Challenges. Vaccines 2020, 8, 266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, A.; Liu, Q.; Yang, Y.; Debnath, A.K.; Du, L. Envelope Protein-Targeting Zika Virus Entry Inhibitors. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 9424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pitts, J.; Hsia, C.-Y.; Lian, W.; Wang, J.; Pfeil, M.-P.; Kwiatkowski, N.; Li, Z.; Jang, J.; Gray, N.S.; Yang, P.L. Identification of Small Molecule Inhibitors Targeting the Zika Virus Envelope Protein. Antivir. Res. 2019, 164, 147–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pathak, N.; Kuo, Y.-P.; Chang, T.-Y.; Huang, C.-T.; Hung, H.-C.; Hsu, J.T.-A.; Yu, G.-Y.; Yang, J.-M. Zika Virus NS3 Protease Pharmacophore Anchor Model and Drug Discovery. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 8929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, L.; Zhang, C. Microscale Thermophoresis (MST) to Detect the Interaction Between Purified Protein and Small Molecule. Methods Mol. Biol. Clifton NJ 2021, 2213, 187–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, A.; Zhang, X.; Dejnirattisai, W.; Dai, X.; Gong, D.; Wongwiwat, W.; Duquerroy, S.; Rouvinski, A.; Vaney, M.-C.; Guardado-Calvo, P.; et al. The Epitope Arrangement on Flavivirus Particles Contributes to Mab C10’s Extraordinary Neutralization Breadth across Zika and Dengue Viruses. Cell 2021, 184, 6052–6066.e18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stettler, K.; Beltramello, M.; Espinosa, D.A.; Graham, V.; Cassotta, A.; Bianchi, S.; Vanzetta, F.; Minola, A.; Jaconi, S.; Mele, F.; et al. Specificity, Cross-Reactivity, and Function of Antibodies Elicited by Zika Virus Infection. Science 2016, 353, 823–826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; Fernandez, E.; Dowd, K.A.; Speer, S.D.; Platt, D.J.; Gorman, M.J.; Govero, J.; Nelson, C.A.; Pierson, T.C.; Diamond, M.S.; et al. Structural Basis of Zika Virus-Specific Antibody Protection. Cell 2016, 166, 1016–1027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keeffe, J.R.; Van Rompay, K.K.A.; Olsen, P.C.; Wang, Q.; Gazumyan, A.; Azzopardi, S.A.; Schaefer-Babajew, D.; Lee, Y.E.; Stuart, J.B.; Singapuri, A.; et al. A Combination of Two Human Monoclonal Antibodies Prevents Zika Virus Escape Mutations in Non-Human Primates. Cell Rep. 2018, 25, 1385–1394.e7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Wang, S.; Hu, Q.; Gao, S.; Ma, X.; Zhang, W.; Shen, Y.; Chen, F.; Lai, L.; Pei, J. CavityPlus: A Web Server for Protein Cavity Detection with Pharmacophore Modelling, Allosteric Site Identification and Covalent Ligand Binding Ability Prediction. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018, 46, W374–W379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, Y.; Tai, W.; Wang, N.; Li, X.; Jiang, S.; Debnath, A.K.; Du, L.; Chen, S. Identification of Novel Natural Products as Effective and Broad-Spectrum Anti-Zika Virus Inhibitors. Viruses 2019, 11, 1019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pierson, T.C.; Diamond, M.S. The Continued Threat of Emerging Flaviviruses. Nat. Microbiol. 2020, 5, 796–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, J.; Shresta, S. Antigenic Cross-Reactivity between Zika and Dengue Viruses: Is it Time to Develop a Universal Vaccine? Curr. Opin. Immunol. 2019, 59, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison, S.C. Immunogenic Cross-Talk between Dengue and Zika Viruses. Nat. Immunol. 2016, 17, 1010–1012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CDC Treatment and Prevention of Zika Virus Disease. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/zika/hcp/clinical-care/index.html (accessed on 24 August 2025).

- Farghaly, T.A.; Harras, M.F.; Alsaedi, A.M.R.; Thakir, H.A.; Mahmoud, H.K.; Katowah, D.F. Antiviral Activity of Pyrimidine Containing Compounds: Patent Review. Mini Rev. Med. Chem. 2023, 23, 821–851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeelan Basha, N.; Chandana, T.L. Synthesis and Antiviral Efficacy of Pyrimidine Analogs Targeting Viral Pathways. ChemistrySelect 2023, 8, e202205009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Yogarajah, T.; Lee, R.C.H.; Kaur, P.; Inoue, M.; Tan, Y.W.; Chu, J.J.H. Drug Repurposing of Pyrimidine Analogs as Potent Antiviral Compounds against Human Enterovirus A71 Infection with Potential Clinical Applications. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 8159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallo, F.N.; Marquez, A.B.; Fidalgo, D.M.; Dana, A.; Dellarole, M.; García, C.C.; Bollini, M. Antiviral Drug Discovery: Pyrimidine Entry Inhibitors for Zika and Dengue Viruses. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2024, 272, 116465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jin, T.; Xu, W.; Chen, R.; Shen, L.; Gao, J.; Xu, L.; Chi, X.; Lin, N.; Zhou, L.; Shen, Z.; et al. Discovery of Potential WEE1 Inhibitors via Hybrid Virtual Screening. Front. Pharmacol. 2023, 14, 1298245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, H.; Hong, H.; Hwang, S.; Kim, S.J.; Seo, S.Y.; No, K.T. Identification of Novel Natural Product Inhibitors against Matrix Metalloproteinase 9 Using Quantum Mechanical Fragment Molecular Orbital-Based Virtual Screening Methods. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 4438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khetmalis, Y.M.; Chitti, S.; Umarani Wunnava, A.; Karan Kumar, B.; Murali Krishna Kumar, M.; Murugesan, S.; Chandra Sekhar, K.V.G. Design, Synthesis and Anti-Mycobacterial Evaluation of Imidazo [1,2-a]Pyridine Analogues. RSC Med. Chem. 2022, 13, 327–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dickerhoff, J.; Warnecke, K.R.; Wang, K.; Deng, N.; Yang, D. Evaluating Molecular Docking Software for Small Molecule Binding to G-Quadruplex DNA. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 10801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reddy, K.K.; Rathore, R.S.; Srujana, P.; Burri, R.R.; Reddy, C.R.; Sumakanth, M.; Reddanna, P.; Reddy, M.R. Performance Evaluation of Docking Programs—Glide, GOLD, AutoDock & SurflexDock, Using Free Energy Perturbation Reference Data: A Case Study of Fructose-1, 6-Bisphosphatase-AMP Analogs. Mini Rev. Med. Chem. 2020, 20, 1179–1187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rambabu, M.; Jayanthi, S. Screening Approaches against Claudin-4 Focusing on Therapeutics through Molecular Docking and the Analysis of Their Relative Dynamics: A Theoretical Approach. J. Recept. Signal Transduct. Res. 2020, 40, 436–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, C.; Xie, X.; Zou, J.; Muruato, A.; Fink, K.; Shi, P.-Y. Using Recombination-Dependent Lethal Mutations to Stabilize Reporter Flaviviruses for Rapid Serodiagnosis and Drug Discovery. EBioMedicine 2020, 57, 102838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Tai, W.; Wang, X.; Jiang, S.; Debnath, A.K.; Du, L.; Chen, S. A Gossypol Derivative Effectively Protects against Zika and Dengue Virus Infection without Toxicity. BMC Biol. 2022, 20, 143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Roy, A.; Cho, H.; Lyles, K.V.; Lu, W.; Luo, M.; Debnath, A.K.; Du, L. Identification of Small Molecules as Zika Virus Entry Inhibitors. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 10726. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262110726

Roy A, Cho H, Lyles KV, Lu W, Luo M, Debnath AK, Du L. Identification of Small Molecules as Zika Virus Entry Inhibitors. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2025; 26(21):10726. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262110726

Chicago/Turabian StyleRoy, Abhijeet, Hansam Cho, Kristin V. Lyles, Wen Lu, Ming Luo, Asim K. Debnath, and Lanying Du. 2025. "Identification of Small Molecules as Zika Virus Entry Inhibitors" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 26, no. 21: 10726. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262110726

APA StyleRoy, A., Cho, H., Lyles, K. V., Lu, W., Luo, M., Debnath, A. K., & Du, L. (2025). Identification of Small Molecules as Zika Virus Entry Inhibitors. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 26(21), 10726. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262110726