Cross-Talk Between Neutrophils and Macrophages Post-Myocardial Infarction: From Inflammatory Drivers to Therapeutic Targets

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Role and Diversity of Neutrophils in Myocardial Infarction

3. Role and Diversity of Macrophages in Myocardial Infarction

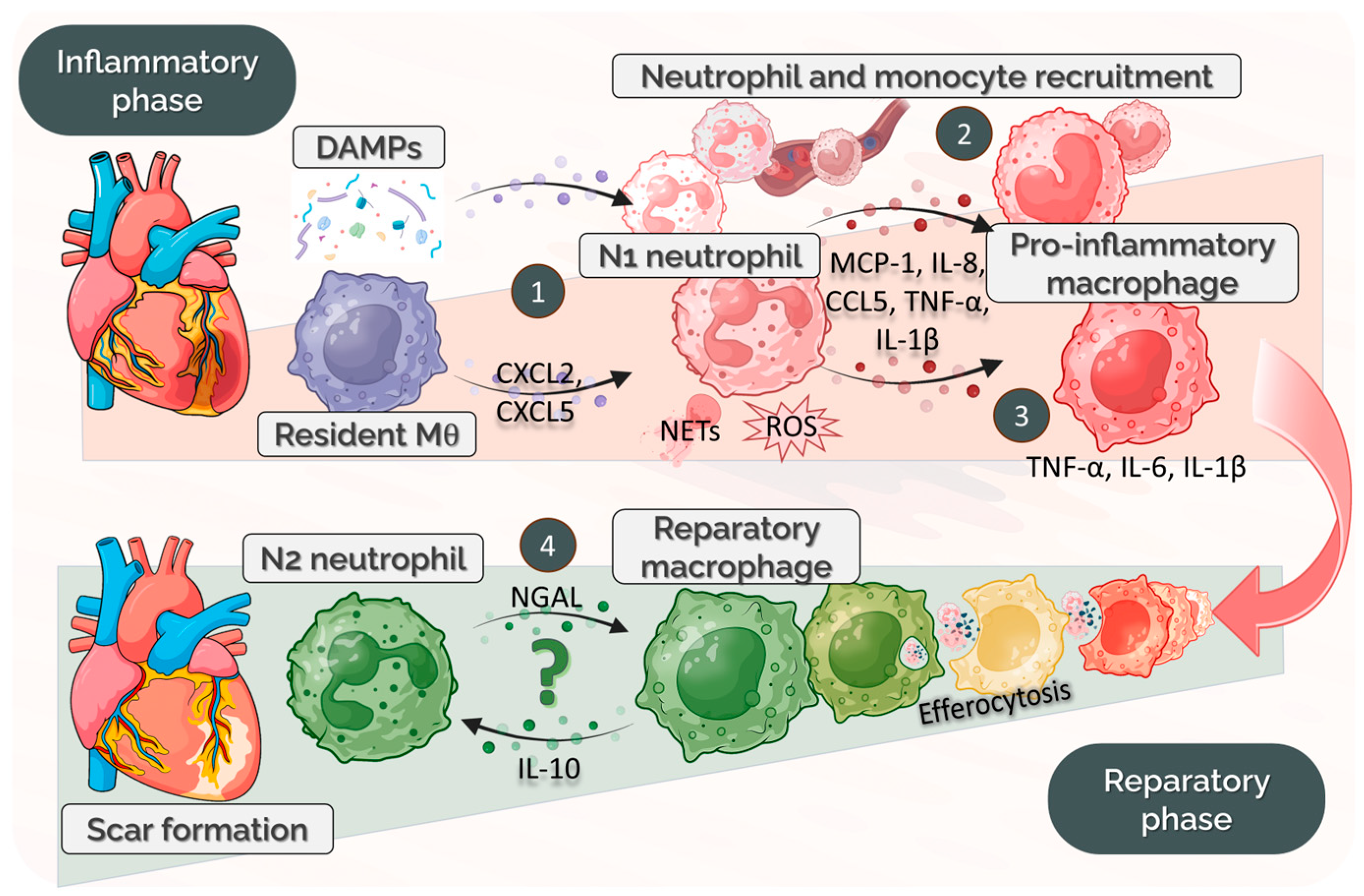

4. Neutrophil–Macrophage Crosstalk: Phenotype Modulation

4.1. Temporal Dynamics of Neutrophil–Macrophage Communication Post-MI

4.2. Transcriptomic Signatures of Neutrophil and Macrophage Subsets Post-MI

4.3. Factors Produced by Neutrophils as Modulators of Macrophage Phenotype

4.3.1. Cytokines/Chemokines

4.3.2. Granule Enzymes

4.3.3. DAMPs and TLR Signaling

4.3.4. Neutrophil Extracellular Traps

4.3.5. Extracellular Vesicles

| Molecular Mediators | Source/Target Cell | Impact on the Target Cell | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| CXCL1, CXCL8, CCL3, CCL4 | N/Mac | monocyte chemotaxis and adhesion, M1 macrophage | [50,51] |

| TNF-α, IL-6, IL-1β | N/Mon, ECs | attract pro-inflammatory Mon, induce M1-Mac, activate ECs | [52] |

| IFNγ | N/Mac | induces M1-Mac, epigenetic changes and metabolic reprogramming | [53] |

| IL-17 | N/Mac | upregulate innate immune receptors, TLR2 and TLR4 | [55] |

| IL-10 | N/Mac | ↓ macrophage activation, inhibits glycolysis and promotes oxidative phosphorylation and autophagy, suppressing the release of cytokines | [57,58] |

| MPO | N/Mon | ↑ CCR2 and monocyte migration, induces M1-Mac | [59,60,61] |

| elastase and cathepsin G | N/Mon | enhances macrophage recruitment through release of matrikines, sustains inflammatory signaling | [63] |

| MMP8 and MMP-9 | N/Mon, Mac | monocyte/macrophage infiltration; indirect macrophage M1/M2 polarization | [65] |

| HMGB1 | N/Mac | NF-kB pathway activation via TLR4 | [69] |

| S100A8/A9 | N/Mac, N | acute MI: ↑IL-1β, IL-6, IL-8, and TNF-α, and induces ROS. day 7 post-MI: M2-Mac polarization | [68,70,71] |

| NETs | N/Mac | NLRP3 inflammasome activation, cytokine and DAMP release, leukocyte recruitment, M1/M2 polarization | [74,75,76,77] |

| MMP12 | Mac/N | NETs clearance | [78] |

| EVs (AnxA1) | N/Mac | counteracts M1-Mac activation, promotes TGF-β and VEGF-A release | [81] |

4.4. Role of Macrophages as Modulators of Neutrophil Phenotypes

4.5. Metabolic Crosstalk Between Neutrophils and Macrophages

5. Pathological Consequences of Dysregulated Immune Interaction

5.1. Altered Balance of Resident Cardiac Macrophage Subsets Affects Early Neutrophil Recruitment Following MI

5.2. Impaired Inflammation Induced by Altered Neutrophil–Macrophage Cross-Talk

5.3. Age- and Sex-Driven Immune Dysregulation in Cardiovascular Injury

6. Therapeutic Implications

7. Gaps in Knowledge—Future Directions

- (i).

- Most studies focus on static images of neutrophil–macrophage interactions, often in vitro or at single time points in vivo. The exact timing and sequence of neutrophil-derived signals (cytokines, chemokines, granule proteins, NETs, and EVs) that dictate macrophage polarization in different phases of cardiac injury remain poorly defined. Moreover, both neutrophils and macrophages are highly heterogeneous, with subpopulations exhibiting distinct functional profiles. How specific neutrophil and macrophage distinct subsets influence each other post-myocardial infarction is largely unexplored.

- (ii).

- While DAMPs and EVs have been shown to activate macrophages via TLR4 or other pathways, the downstream signaling networks, cross-talk with other immune cells, and contribution to maladaptive remodeling are not fully understanded. Additionally, the cargo composition of EVs in different activation states and its functional consequences require further investigation.

- (iii).

- Despite recognition of neutrophil-derived mediators as modulators of macrophage phenotype, strategies to selectively manipulate these signals without compromising host defense are still in their infancy. Optimizing timing, delivery, and specificity of interventions targeting neutrophil–macrophage communication is a major unmet need.

- (iv).

- When considering early therapeutic interventions to modulate the neutrophil–macrophage cross-talk, the cardiac resident macrophages may represent a primary target that was not investigated until now.

8. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Salari, N.; Morddarvanjoghi, F.; Abdolmaleki, A.; Rasoulpoor, S.; Khaleghi, A.A.; Hezarkhani, L.A.; Shohaimi, S.; Mohammadi, M. The global prevalence of myocardial infarction: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Cardiovasc. Disord. 2023, 23, 206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christia, P.; Frangogiannis, N.G. Targeting inflammatory pathways in myocardial infarction. Eur. J. Clin. Investig. 2013, 43, 986–995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ojha, N.; Dhamoon, A.S. Myocardial Infarction. In StatPearls; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Bajpai, G.; Bredemeyer, A.; Li, W.; Zaitsev, K.; Koenig, A.L.; Lokshina, I.; Mohan, J.; Ivey, B.; Hsiao, H.M.; Weinheimer, C.; et al. Tissue Resident CCR2− and CCR2+ Cardiac Macrophages Differentially Orchestrate Monocyte Recruitment and Fate Specification Following Myocardial Injury. Circ. Res. 2019, 124, 263–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Hsiao, H.M.; Higashikubo, R.; Saunders, B.T.; Bharat, A.; Goldstein, D.R.; Krupnick, A.S.; Gelman, A.E.; Lavine, K.J.; Kreisel, D. Heart-resident CCR2+ macrophages promote neutrophil extravasation through TLR9/MyD88/CXCL5 signaling. JCI Insight 2016, 1, e87315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofmann, U.; Beyersdorf, N.; Weirather, J.; Podolskaya, A.; Bauersachs, J.; Ertl, G.; Kerkau, T.; Frantz, S. Activation of CD4+ T lymphocytes improves wound healing and survival after experimental myocardial infarction in mice. Circulation 2012, 125, 1652–1663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Day, R.B.; Link, D.C. Regulation of neutrophil trafficking from the bone marrow. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2012, 69, 1415–1423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eash, K.J.; Greenbaum, A.M.; Gopalan, P.K.; Link, D.C. CXCR2 and CXCR4 antagonistically regulate neutrophil trafficking from murine bone marrow. J. Clin. Investig. 2010, 120, 2423–2431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silvestre-Roig, C.; Hidalgo, A.; Soehnlein, O. Neutrophil heterogeneity: Implications for homeostasis and pathogenesis. Blood 2016, 127, 2173–2181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanhaver, C.; Aboubakar Nana, F.; Delhez, N.; Luyckx, M.; Hirsch, T.; Bayard, A.; Houbion, C.; Dauguet, N.; Brochier, A.; van der Bruggen, P.; et al. Immunosuppressive low-density neutrophils in the blood of cancer patients display a mature phenotype. Life Sci. Alliance 2024, 7, e202302332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casanova-Acebes, M.; Nicolas-Avila, J.A.; Li, J.L.; Garcia-Silva, S.; Balachander, A.; Rubio-Ponce, A.; Weiss, L.A.; Adrover, J.M.; Burrows, K.; A-González, N.; et al. Neutrophils instruct homeostatic and pathological states in naive tissues. J. Exp. Med. 2018, 215, 2778–2795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutta, P.; Courties, G.; Wei, Y.; Leuschner, F.; Gorbatov, R.; Robbins, C.S.; Iwamoto, Y.; Thompson, B.; Carlson, A.L.; Heidt, T.; et al. Myocardial infarction accelerates atherosclerosis. Nature 2012, 487, 325–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puhl, S.L.; Steffens, S. Neutrophils in Post-myocardial Infarction Inflammation: Damage vs. Resolution? Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2019, 6, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vafadarnejad, E.; Rizzo, G.; Krampert, L.; Arampatzi, P.; Arias-Loza, A.P.; Nazzal, Y.; Rizakou, A.; Knochenhauer, T.; Bandi, S.R.; Nugroho, V.A.; et al. Dynamics of Cardiac Neutrophil Diversity in Murine Myocardial Infarction. Circ. Res. 2020, 127, e232–e249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Xu, Z.; Liu, Z. Impact of Neutrophil Extracellular Traps on Thrombosis Formation: New Findings and Future Perspective. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2022, 12, 910908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mihaila, A.C.; Ciortan, L.; Tucureanu, M.M.; Simionescu, M.; Butoi, E. Anti-Inflammatory Neutrophils Reprogram Macrophages toward a Pro-Healing Phenotype with Increased Efferocytosis Capacity. Cells 2024, 13, 208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, Y.; Yabluchanskiy, A.; Iyer, R.P.; Cannon, P.L.; Flynn, E.R.; Jung, M.; Henry, J.; Cates, C.A.; Deleon-Pennell, K.Y.; Lindsey, M.L. Temporal neutrophil polarization following myocardial infarction. Cardiovasc. Res. 2016, 110, 51–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calcagno, D.M.; Zhang, C.; Toomu, A.; Huang, K.; Ninh, V.K.; Miyamoto, S.; Aguirre, A.D.; Fu, Z.; Heller Brown, J.; King, K.R. SiglecF(HI) Marks Late-Stage Neutrophils of the Infarcted Heart: A Single-Cell Transcriptomic Analysis of Neutrophil Diversification. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2021, 10, e019019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mihaila, A.C.; Ciortan, L.; Macarie, R.D.; Vadana, M.; Cecoltan, S.; Preda, M.B.; Hudita, A.; Gan, A.-M.; Jakobsson, G.; Tucureanu, M.M.; et al. Transcriptional Profiling and Functional Analysis of N1/N2 Neutrophils Reveal an Immunomodulatory Effect of S100A9-Blockade on the Pro-Inflammatory N1 Subpopulation. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 708770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mass, E.; Nimmerjahn, F.; Kierdorf, K.; Schlitzer, A. Tissue-specific macrophages: How they develop and choreograph tissue biology. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2023, 23, 563–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roszer, T. Understanding the Biology of Self-Renewing Macrophages. Cells 2018, 7, 103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, Y.; Zhu, L. At the heart of inflammation: Unravelling cardiac resident macrophage biology. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 2024, 28, e70050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bajpai, G.; Schneider, C.; Wong, N.; Bredemeyer, A.; Hulsmans, M.; Nahrendorf, M.; Epelman, S.; Kreisel, D.; Liu, Y.; Itoh, A.; et al. The human heart contains distinct macrophage subsets with divergent origins and functions. Nat. Med. 2018, 24, 1234–1245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Epelman, S.; Lavine, K.J.; Beaudin, A.E.; Sojka, D.K.; Carrero, J.A.; Calderon, B.; Brija, T.; Gautier, E.L.; Ivanov, S.; Satpathy, A.T.; et al. Embryonic and adult-derived resident cardiac macrophages are maintained through distinct mechanisms at steady state and during inflammation. Immunity 2014, 40, 91–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, R.; Zhang, H.; Tang, B.; Luo, Y.; Yang, Y.; Zhong, X.; Chen, S.; Xu, X.; Huang, S.; Liu, C. Macrophages in cardiovascular diseases: Molecular mechanisms and therapeutic targets. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2024, 9, 130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nahrendorf, M.; Swirski, F.K.; Aikawa, E.; Stangenberg, L.; Wurdinger, T.; Figueiredo, J.L.; Libby, P.; Weissleder, R.; Pittet, M.J. The healing myocardium sequentially mobilizes two monocyte subsets with divergent and complementary functions. J. Exp. Med. 2007, 204, 3037–3047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dewald, O.; Zymek, P.; Winkelmann, K.; Koerting, A.; Ren, G.; Abou-Khamis, T.; Michael, L.H.; Rollins, B.J.; Entman, M.L.; Frangogiannis, N.G. CCL2/Monocyte Chemoattractant Protein-1 regulates inflammatory responses critical to healing myocardial infarcts. Circ. Res. 2005, 96, 881–889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kratofil, R.M.; Kubes, P.; Deniset, J.F. Monocyte Conversion During Inflammation and Injury. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2017, 37, 35–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Saeed, A.; Liu, Q.; Jiang, Q.; Xu, H.; Xiao, G.G.; Rao, L.; Duo, Y. Macrophages in immunoregulation and therapeutics. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2023, 8, 207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mouton, A.J.; DeLeon-Pennell, K.Y.; Rivera Gonzalez, O.J.; Flynn, E.R.; Freeman, T.C.; Saucerman, J.J.; Garrett, M.R.; Ma, Y.; Harmancey, R.; Lindsey, M.L. Mapping macrophage polarization over the myocardial infarction time continuum. Basic Res. Cardiol. 2018, 113, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shirakawa, K.; Endo, J.; Kataoka, M.; Katsumata, Y.; Yoshida, N.; Yamamoto, T.; Isobe, S.; Moriyama, H.; Goto, S.; Kitakata, H.; et al. IL (Interleukin)-10-STAT3-Galectin-3 Axis Is Essential for Osteopontin-Producing Reparative Macrophage Polarization After Myocardial Infarction. Circulation 2018, 138, 2021–2035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Horckmans, M.; Ring, L.; Duchene, J.; Santovito, D.; Schloss, M.J.; Drechsler, M.; Weber, C.; Soehnlein, O.; Steffens, S. Neutrophils orchestrate post-myocardial infarction healing by polarizing macrophages towards a reparative phenotype. Eur. Heart J. 2017, 38, 187–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolaczkowska, E.; Kubes, P. Neutrophil recruitment and function in health and inflammation. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2013, 13, 159–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doring, Y.; Drechsler, M.; Soehnlein, O.; Weber, C. Neutrophils in atherosclerosis: From mice to man. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2015, 35, 288–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, C.; Kim, H.; Sim, W.S.; Jung, M.; Hong, J.; Moon, S.; Park, J.H.; Kim, J.J.; Kang, M.; Kwon, S.; et al. Spatiotemporal control of neutrophil fate to tune inflammation and repair for myocardial infarction therapy. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 8481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, X.; Zou, S.; Xie, Z.; Wang, Z.; Huang, N.; Cen, Z.; Hao, Y.; Zhang, C.; Chen, Z.; Zhao, F.; et al. EDIL3 deficiency ameliorates adverse cardiac remodelling by neutrophil extracellular traps (NET)-mediated macrophage polarization. Cardiovasc. Res. 2022, 118, 2179–2195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prabhu, S.D.; Frangogiannis, N.G. The Biological Basis for Cardiac Repair After Myocardial Infarction: From Inflammation to Fibrosis. Circ. Res. 2016, 119, 91–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Wei, P.; Li, B.; He, J.; Zhou, T.; Hou, Q.; Yu, Y.; Hou, J.; Yan, C.; Han, Y. Temporal dynamics of the multi-omic response reveals the modulation of macrophage subsets post-myocardial infarction. J. Transl. Med. 2025, 23, 777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, X.; Shi, Q.; Wu, P.; Zhang, X.; Kambara, H.; Su, J.; Yu, H.; Park, S.Y.; Guo, R.; Ren, Q.; et al. Single-cell transcriptome profiling reveals neutrophil heterogeneity in homeostasis and infection. Nat. Immunol. 2020, 21, 1119–1133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dick, S.A.; Wong, A.; Hamidzada, H.; Nejat, S.; Nechanitzky, R.; Vohra, S.; Mueller, B.; Zaman, R.; Kantores, C.; Aronoff, L.; et al. Three tissue resident macrophage subsets coexist across organs with conserved origins and life cycles. Sci. Immunol. 2022, 7, eabf7777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ke, D.; Cao, M.; Ni, J.; Yuan, Y.; Deng, J.; Chen, S.; Dai, X.; Zhou, H. Macrophage and fibroblast trajectory inference and crosstalk analysis during myocardial infarction using integrated single-cell transcriptomic datasets. J. Transl. Med. 2024, 22, 560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakarov, S.; Lim, H.Y.; Tan, L.; Lim, S.Y.; See, P.; Lum, J.; Zhang, X.M.; Foo, S.; Nakamizo, S.; Duan, K.; et al. Two distinct interstitial macrophage populations coexist across tissues in specific subtissular niches. Science 2019, 363, eaau0964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Litvinukova, M.; Talavera-Lopez, C.; Maatz, H.; Reichart, D.; Worth, C.L.; Lindberg, E.L.; Kanda, M.; Polanski, K.; Heinig, M.; Lee, M.; et al. Cells of the adult human heart. Nature 2020, 588, 466–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arlauckas, S.P.; Garren, S.B.; Garris, C.S.; Kohler, R.H.; Oh, J.; Pittet, M.J.; Weissleder, R. Arg1 expression defines immunosuppressive subsets of tumor-associated macrophages. Theranostics 2018, 8, 5842–5854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, M.; Jia, S.; Xu, L.; Li, X.; Lv, Y.; Zhong, Y.; Ai, S. Single-cell multiomic analysis identifies macrophage subpopulations in promoting cardiac repair. J. Clin. Investig. 2024, 134, e175297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cesaro, G.; Nagai, J.S.; Gnoato, N.; Chiodi, A.; Tussardi, G.; Kloker, V.; Musumarra, C.V.; Mosca, E.; Costa, I.G.; Di Camillo, B.; et al. Advances and challenges in cell-cell communication inference: A comprehensive review of tools, resources, and future directions. Brief. Bioinform. 2025, 26, bbaf280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, S.H.; Hwang, B.H.; Shin, S.; Park, E.H.; Park, S.H.; Kim, C.W.; Kim, E.; Choo, E.; Choi, I.J.; Swirski, F.K.; et al. Spatiotemporal dynamics of macrophage heterogeneity and a potential function of Trem2(hi) macrophages in infarcted hearts. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 4580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calcagno, D.M.; Taghdiri, N.; Ninh, V.K.; Mesfin, J.M.; Toomu, A.; Sehgal, R.; Lee, J.; Liang, Y.; Duran, J.M.; Adler, E.; et al. Single-cell and spatial transcriptomics of the infarcted heart define the dynamic onset of the border zone in response to mechanical destabilization. Nat. Cardiovasc. Res. 2022, 1, 1039–1055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tecchio, C.; Micheletti, A.; Cassatella, M.A. Neutrophil-derived cytokines: Facts beyond expression. Front. Immunol. 2014, 5, 508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, T.T.; Chen, J.W. Emerging role of chemokine CC motif ligand 4 related mechanisms in diabetes mellitus and cardiovascular disease: Friends or foes? Cardiovasc. Diabetol. 2016, 15, 117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tecchio, C.; Cassatella, M.A. Neutrophil-derived chemokines on the road to immunity. Semin. Immunol. 2016, 28, 119–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prabhu, S.D. Cytokine-induced modulation of cardiac function. Circ. Res. 2004, 95, 1140–1153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivashkiv, L.B. IFNgamma: Signalling, epigenetics and roles in immunity, metabolism, disease and cancer immunotherapy. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2018, 18, 545–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gorin, A.; Harriott, N.; Koduvayur, V.; Cheng, Q.J.; Hoffmann, A. IFNgamma-induced memory in human macrophages is not sustained by epigenetic changes but the durability of the cytokine itself. bioRxiv 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de la Paz Sanchez-Martinez, M.; Blanco-Favela, F.; Mora-Ruiz, M.D.; Chavez-Rueda, A.K.; Bernabe-Garcia, M.; Chavez-Sanchez, L. IL-17-differentiated macrophages secrete pro-inflammatory cytokines in response to oxidized low-density lipoprotein. Lipids Health Dis. 2017, 16, 196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Wu, P.; Siegel, M.I.; Egan, R.W.; Billah, M.M. Interleukin (IL)-10 inhibits nuclear factor kappa B (NF kappa B) activation in human monocytes. IL-10 and IL-4 suppress cytokine synthesis by different mechanisms. J. Biol. Chem. 1995, 270, 9558–9563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saraiva, M.; Vieira, P.; O’Garra, A. Biology and therapeutic potential of interleukin-10. J. Exp. Med. 2020, 217, e20190418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ip, W.K.E.; Hoshi, N.; Shouval, D.S.; Snapper, S.; Medzhitov, R. Anti-inflammatory effect of IL-10 mediated by metabolic reprogramming of macrophages. Science 2017, 356, 513–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicholls, S.J.; Hazen, S.L. Myeloperoxidase and cardiovascular disease. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2005, 25, 1102–1111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peters, V.B.M.; Matheis, F.; Erdmann, I.; Nemade, H.N.; Muders, D.; Toubartz, M.; Torun, M.; Mehrkens, D.; Geissen, S.; Nettersheim, F.S.; et al. Myeloperoxidase induces monocyte migration and activation after acute myocardial infarction. Front. Immunol. 2024, 15, 1360700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lefkowitz, D.L.; Mills, K.; Morgan, D.; Lefkowitz, S.S. Macrophage activation and immunomodulation by myeloperoxidase. Proc. Soc. Exp. Biol. Med. 1992, 199, 204–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Korkmaz, B.; Moreau, T.; Gauthier, F. Neutrophil elastase, proteinase 3 and cathepsin G: Physicochemical properties, activity and physiopathological functions. Biochimie 2008, 90, 227–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaggar, A.; Weathington, N. Bioactive extracellular matrix fragments in lung health and disease. J. Clin. Investig. 2016, 126, 3176–3184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Huang, Y.; Ji, Q.; Fu, S.; Gu, J.; Tai, N.; Wang, X. Interplay between Extracellular Matrix and Neutrophils in Diseases. J. Immunol. Res. 2021, 2021, 8243378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, G.; Zhang, C.; Chen, Q.; Luong, L.A.; Mustafa, A.; Ye, S.; Xiao, Q. A Novel Role of Matrix Metalloproteinase-8 in Macrophage Differentiation and Polarization. J. Biol. Chem. 2015, 290, 19158–19172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, Z.; Xie, Q.; Hu, T.; Yao, Q.; Zhao, J.; Wu, Q.; Tang, Q. S100A8/A9 in Myocardial Infarction: A Promising Biomarker and Therapeutic Target. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2020, 8, 603902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, R.; Kang, R.; Tang, D. The mechanism of HMGB1 secretion and release. Exp. Mol. Med. 2022, 54, 91–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Acter, S.; Lin, Q. S100 proteins as a key immunoregulatory mechanism for NLRP3 inflammasome. Front. Immunol. 2025, 16, 1663547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, M.; Zhou, H.; Zhou, L.; Yang, Y.; Chen, R. Research progress on macrophages in cardiovascular diseases. J. Cardiothorac. Surg. 2025, 20, 307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wahid, A.; Chen, W.; Wang, X.; Tang, X. High-mobility group box 1 serves as an inflammation driver of cardiovascular disease. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2021, 139, 111555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marinkovic, G.; Koenis, D.S.; de Camp, L.; Jablonowski, R.; Graber, N.; de Waard, V.; de Vries, C.J.; Goncalves, I.; Nilsson, J.; Jovinge, S.; et al. S100A9 Links Inflammation and Repair in Myocardial Infarction. Circ. Res. 2020, 127, 664–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silvis, M.J.M.; Kaffka Genaamd Dengler, S.E.; Odille, C.A.; Mishra, M.; van der Kaaij, N.P.; Doevendans, P.A.; Sluijter, J.P.G.; de Kleijn, D.P.V.; de Jager, S.C.A.; Bosch, L.; et al. Damage-Associated Molecular Patterns in Myocardial Infarction and Heart Transplantation: The Road to Translational Success. Front. Immunol. 2020, 11, 599511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Wei, S.; Wu, X.; Li, Y.; Han, X. Neutrophil extracellular traps in acute coronary syndrome. J. Inflamm. 2023, 20, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eghbalzadeh, K.; Georgi, L.; Louis, T.; Zhao, H.; Keser, U.; Weber, C.; Mollenhauer, M.; Conforti, A.; Wahlers, T.; Paunel-Gorgulu, A. Compromised Anti-inflammatory Action of Neutrophil Extracellular Traps in PAD4-Deficient Mice Contributes to Aggravated Acute Inflammation After Myocardial Infarction. Front. Immunol. 2019, 10, 2313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, P.; Kumar, N.; Singh, M.; Kaur, M.; Singh, G.; Narang, A.; Kanwal, A.; Sharma, K.; Singh, B.; Napoli, M.D.; et al. Neutrophil Extracellular Traps and NLRP3 Inflammasome: A Disturbing Duo in Atherosclerosis, Inflammation and Atherothrombosis. Vaccines 2023, 11, 261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Conforti, A.; Wahlers, T.; Paunel-Gorgulu, A. Neutrophil extracellular traps modulate inflammatory markers and uptake of oxidized LDL by human and murine macrophages. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0259894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tan, H.; Zhang, S.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, J.; Wang, Z.; Liao, J.; Qiu, X.; Jia, E. Neutrophil extracellular traps promote M1 macrophage polarization in gouty inflammation via targeting hexokinase-2. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2024, 224, 540–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bellac, C.L.; Dufour, A.; Krisinger, M.J.; Loonchanta, A.; Starr, A.E.; Auf dem Keller, U.; Lange, P.F.; Goebeler, V.; Kappelhoff, R.; Butler, G.S.; et al. Macrophage matrix metalloproteinase-12 dampens inflammation and neutrophil influx in arthritis. Cell Rep. 2014, 9, 618–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, P.; Wang, X.; Liu, Q.; Yang, T.; Qu, H.; Zhou, H. Extracellular vesicles mediate biological information delivery: A double-edged sword in cardiac remodeling after myocardial infarction. Front. Pharmacol. 2023, 14, 1067992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Q.; Lyon, C.J.; Fletcher, J.K.; Tang, W.; Wan, M.; Hu, T.Y. Extracellular vesicle activities regulating macrophage- and tissue-mediated injury and repair responses. Acta Pharm. Sin. B 2021, 11, 1493–1512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rhys, H.I.; Dell’Accio, F.; Pitzalis, C.; Moore, A.; Norling, L.V.; Perretti, M. Neutrophil Microvesicles from Healthy Control and Rheumatoid Arthritis Patients Prevent the Inflammatory Activation of Macrophages. EBioMedicine 2018, 29, 60–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, H.; Liu, T.; Wang, Y.; Bai, W.; Luo, Y.; Wang, J. Neutrophil-macrophage communication via extracellular vesicle transfer promotes itaconate accumulation and ameliorates cytokine storm syndrome. Cell. Mol. Immunol. 2024, 21, 689–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Paula-Silva, M.; da Rocha, G.H.O.; Broering, M.F.; Queiroz, M.L.; Sandri, S.; Loiola, R.A.; Oliani, S.M.; Vieira, A.; Perretti, M.; Farsky, S.H.P. Formyl Peptide Receptors and Annexin A1: Complementary Mechanisms to Infliximab in Murine Experimental Colitis and Crohn’s Disease. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 714138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferraro, B.; Leoni, G.; Hinkel, R.; Ormanns, S.; Paulin, N.; Ortega-Gomez, A.; Viola, J.R.; de Jong, R.; Bongiovanni, D.; Bozoglu, T.; et al. Pro-Angiogenic Macrophage Phenotype to Promote Myocardial Repair. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2019, 73, 2990–3002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnson, B.L., III; Kuethe, J.W.; Caldwell, C.C. Neutrophil derived microvesicles: Emerging role of a key mediator to the immune response. Endocr. Metab. Immune Disord. Drug Targets 2014, 14, 210–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, D.M.; Walsh, A.; Stein, L.; Petrasca, A.; Cox, D.J.; Brown, K.; Duffin, E.; Jameson, G.; Connolly, S.A.; O’Connell, F.; et al. Human Macrophages Activate Bystander Neutrophils’ Metabolism and Effector Functions When Challenged with Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 2898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Neill, L.A.; Kishton, R.J.; Rathmell, J. A guide to immunometabolism for immunologists. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2016, 16, 553–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Six, E.; Lagresle-Peyrou, C.; Susini, S.; De Chappedelaine, C.; Sigrist, N.; Sadek, H.; Chouteau, M.; Cagnard, N.; Fontenay, M.; Hermine, O.; et al. AK2 deficiency compromises the mitochondrial energy metabolism required for differentiation of human neutrophil and lymphoid lineages. Cell Death Dis. 2015, 6, e1856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodriguez-Espinosa, O.; Rojas-Espinosa, O.; Moreno-Altamirano, M.M.; Lopez-Villegas, E.O.; Sanchez-Garcia, F.J. Metabolic requirements for neutrophil extracellular traps formation. Immunology 2015, 145, 213–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richer, B.C.; Salei, N.; Laskay, T.; Seeger, K. Changes in Neutrophil Metabolism upon Activation and Aging. Inflammation 2018, 41, 710–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Azevedo, E.P.; Rochael, N.C.; Guimaraes-Costa, A.B.; de Souza-Vieira, T.S.; Ganilho, J.; Saraiva, E.M.; Palhano, F.L.; Foguel, D. A Metabolic Shift toward Pentose Phosphate Pathway Is Necessary for Amyloid Fibril- and Phorbol 12-Myristate 13-Acetate-induced Neutrophil Extracellular Trap (NET) Formation. J. Biol. Chem. 2015, 290, 22174–22183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borregaard, N.; Herlin, T. Energy metabolism of human neutrophils during phagocytosis. J. Clin. Investig. 1982, 70, 550–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nareika, A.; He, L.; Game, B.A.; Slate, E.H.; Sanders, J.J.; London, S.D.; Lopes-Virella, M.F.; Huang, Y. Sodium lactate increases LPS-stimulated MMP and cytokine expression in U937 histiocytes by enhancing AP-1 and NF-kappaB transcriptional activities. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 2005, 289, E534–E542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Tang, Z.; Huang, H.; Zhou, G.; Cui, C.; Weng, Y.; Liu, W.; Kim, S.; Lee, S.; Perez-Neut, M.; et al. Metabolic regulation of gene expression by histone lactylation. Nature 2019, 574, 575–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tannahill, G.M.; Curtis, A.M.; Adamik, J.; Palsson-McDermott, E.M.; McGettrick, A.F.; Goel, G.; Frezza, C.; Bernard, N.J.; Kelly, B.; Foley, N.H.; et al. Succinate is an inflammatory signal that induces IL-1beta through HIF-1alpha. Nature 2013, 496, 238–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mills, E.; O’Neill, L.A. Succinate: A metabolic signal in inflammation. Trends Cell Biol. 2014, 24, 313–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rath, M.; Muller, I.; Kropf, P.; Closs, E.I.; Munder, M. Metabolism via Arginase or Nitric Oxide Synthase: Two Competing Arginine Pathways in Macrophages. Front. Immunol. 2014, 5, 532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, N.; Aiyasiding, X.; Li, W.J.; Liao, H.H.; Tang, Q.Z. Neutrophil degranulation and myocardial infarction. Cell Commun. Signal 2022, 20, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, C.; Gonon, A.T.; Sjoquist, P.O.; Lundberg, J.O.; Pernow, J. Arginase inhibition mediates cardioprotection during ischaemia-reperfusion. Cardiovasc. Res. 2010, 85, 147–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gronros, J.; Kiss, A.; Palmer, M.; Jung, C.; Berkowitz, D.; Pernow, J. Arginase inhibition improves coronary microvascular function and reduces infarct size following ischaemia-reperfusion in a rat model. Acta Physiol. 2013, 208, 172–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koch, C.; Henrich, M.; Heidt, M.C. Sequential analysis of myeloperoxidase for prediction of adverse events after suspected acute coronary ischemia. Clin. Cardiol. 2014, 37, 744–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jha, A.K.; Huang, S.C.; Sergushichev, A.; Lampropoulou, V.; Ivanova, Y.; Loginicheva, E.; Chmielewski, K.; Stewart, K.M.; Ashall, J.; Everts, B.; et al. Network integration of parallel metabolic and transcriptional data reveals metabolic modules that regulate macrophage polarization. Immunity 2015, 42, 419–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van den Bossche, J.; Baardman, J.; Otto, N.A.; van der Velden, S.; Neele, A.E.; van den Berg, S.M.; Luque-Martin, R.; Chen, H.J.; Boshuizen, M.C.; Ahmed, M.; et al. Mitochondrial Dysfunction Prevents Repolarization of Inflammatory Macrophages. Cell Rep. 2016, 17, 684–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marechal, P.; Tridetti, J.; Nguyen, M.L.; Wera, O.; Jiang, Z.; Gustin, M.; Donneau, A.F.; Oury, C.; Lancellotti, P. Neutrophil Phenotypes in Coronary Artery Disease. J. Clin. Med. 2020, 9, 1602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, W.H.; Grieshaber, C.K.; Miller, W.C.; Wilson, S.M.; Hoffman, H.A. Polyamine synthesis in bone marrow granulocytes: Effect of cell maturity and early changes following an inflammatory stimulus. Blood 1978, 51, 1021–1029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardbower, D.M.; Asim, M.; Luis, P.B.; Singh, K.; Barry, D.P.; Yang, C.; Steeves, M.A.; Cleveland, J.L.; Schneider, C.; Piazuelo, M.B.; et al. Ornithine decarboxylase regulates M1 macrophage activation and mucosal inflammation via histone modifications. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2017, 114, E751–E760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yurdagul, A., Jr.; Subramanian, M.; Wang, X.; Crown, S.B.; Ilkayeva, O.R.; Darville, L.; Kolluru, G.K.; Rymond, C.C.; Gerlach, B.D.; Zheng, Z.; et al. Macrophage Metabolism of Apoptotic Cell-Derived Arginine Promotes Continual Efferocytosis and Resolution of Injury. Cell Metab. 2020, 31, 518–533.e10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, R.; Li, X.; Ma, H.; Yang, Q.; Shang, Q.; Song, L.; Zheng, Z.; Zhang, S.; Pan, Y.; Huang, P.; et al. Spermidine endows macrophages anti-inflammatory properties by inducing mitochondrial superoxide-dependent AMPK activation, Hif-1alpha upregulation and autophagy. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2020, 161, 339–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Molawi, K.; Wolf, Y.; Kandalla, P.K.; Favret, J.; Hagemeyer, N.; Frenzel, K.; Pinto, A.R.; Klapproth, K.; Henri, S.; Malissen, B.; et al. Progressive replacement of embryo-derived cardiac macrophages with age. J. Exp. Med. 2014, 211, 2151–2158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antipenko, S.; Mayfield, N.; Jinno, M.; Gunzer, M.; Ismahil, M.A.; Hamid, T.; Prabhu, S.D.; Rokosh, G. Neutrophils are indispensable for adverse cardiac remodeling in heart failure. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 2024, 189, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dong, H.; Zhang, Y.; Huang, Y.; Deng, H. Pathophysiology of RAGE in inflammatory diseases. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 931473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kohno, T.; Anzai, T.; Naito, K.; Miyasho, T.; Okamoto, M.; Yokota, H.; Yamada, S.; Maekawa, Y.; Takahashi, T.; Yoshikawa, T.; et al. Role of high-mobility group box 1 protein in post-infarction healing process and left ventricular remodelling. Cardiovasc. Res. 2009, 81, 565–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selejan, S.R.; Hewera, L.; Hohl, M.; Kazakov, A.; Ewen, S.; Kindermann, I.; Bohm, M.; Link, A. Suppressed MMP-9 Activity in Myocardial Infarction-Related Cardiogenic Shock Implies Diminished Rage Degradation. Shock 2017, 48, 18–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.J.; Zhao, Q.; Qu, H.J.; Li, X.M.; Chen, Q.J.; Liu, F.; Chen, B.D.; Yang, Y.N. Usefulness of plasma matrix metalloproteinase-9 levels in prediction of in-hospital mortality in patients who received emergent percutaneous coronary artery intervention following myocardial infarction. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 105809–105818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iyer, R.P.; Patterson, N.L.; Zouein, F.A.; Ma, Y.; Dive, V.; de Castro Bras, L.E.; Lindsey, M.L. Early matrix metalloproteinase-12 inhibition worsens post-myocardial infarction cardiac dysfunction by delaying inflammation resolution. Int. J. Cardiol. 2015, 185, 198–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Foglio, E.; Pellegrini, L.; Russo, M.A.; Limana, F. HMGB1-Mediated Activation of the Inflammatory-Reparative Response Following Myocardial Infarction. Cells 2022, 11, 216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Blokland, I.V.; Groot, H.E.; Hendriks, T.; Assa, S.; van der Harst, P. Sex differences in leukocyte profile in ST-elevation myocardial infarction patients. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 6851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, E.B.; Mendoza, L.D.; Sandifer, J.D.; Morato, J.G.; Aitken, N.M.; O’Quinn, K.R.; Raman, I.; Zhu, C.; Spitz, R.W.; Hall, J.E.; et al. Sex differences in the chronic autoimmune response to myocardial infarction. Clin. Sci. 2025, 139, 627–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tumminello, G.; D’Errico, A.; Maruccio, A.; Gentile, D.; Barbieri, L.; Carugo, S. Age-Related Mortality in STEMI Patients: Insight from One Year of HUB Centre Experience during the Pandemic. J. Cardiovasc. Dev. Dis. 2022, 9, 432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Del Turco, S.; Basta, G.; De Caterina, A.R.; Sbrana, S.; Paradossi, U.; Taddei, A.; Trianni, G.; Ravani, M.; Palmieri, C.; Berti, S.; et al. Different inflammatory profile in young and elderly STEMI patients undergoing primary percutaneous coronary intervention (PPCI): Its influence on no-reflow and mortality. Int. J. Cardiol. 2019, 290, 34–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovacs, E.J.; Palmer, J.L.; Fortin, C.F.; Fulop, T., Jr.; Goldstein, D.R.; Linton, P.J. Aging and innate immunity in the mouse: Impact of intrinsic and extrinsic factors. Trends Immunol. 2009, 30, 319–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fulop, T.; Larbi, A.; Douziech, N.; Fortin, C.; Guerard, K.P.; Lesur, O.; Khalil, A.; Dupuis, G. Signal transduction and functional changes in neutrophils with aging. Aging Cell 2004, 3, 217–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdullah, G.A.; Akpan, A.; Phelan, M.M.; Wright, H.L. The complex role of neutrophils in healthy aging, inflammaging, and frailty. J. Leukoc. Biol. 2025, 117, qiaf117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrero, C.; Marques, L.; Lloberas, J.; Celada, A. IFN-gamma-dependent transcription of MHC class II IA is impaired in macrophages from aged mice. J. Clin. Investig. 2001, 107, 485–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swift, M.E.; Burns, A.L.; Gray, K.L.; DiPietro, L.A. Age-related alterations in the inflammatory response to dermal injury. J. Investig. Dermatol. 2001, 117, 1027–1035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tobin, S.W.; Alibhai, F.J.; Weisel, R.D.; Li, R.K. Considering Cause and Effect of Immune Cell Aging on Cardiac Repair after Myocardial Infarction. Cells 2020, 9, 1894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, K.A.; Flores, R.R.; Jang, I.H.; Saathoff, A.; Robbins, P.D. Immune Senescence, Immunosenescence and Aging. Front. Aging 2022, 3, 900028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weng, N.P. Aging of the immune system: How much can the adaptive immune system adapt? Immunity 2006, 24, 495–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buonacera, A.; Stancanelli, B.; Colaci, M.; Malatino, L. Neutrophil to Lymphocyte Ratio: An Emerging Marker of the Relationships between the Immune System and Diseases. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 3636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lagunas-Rangel, F.A. Neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio in aging: Trends and clinical implications. Exp. Gerontol. 2025, 211, 112908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corriere, T.; Di Marca, S.; Cataudella, E.; Pulvirenti, A.; Alaimo, S.; Stancanelli, B.; Malatino, L. Neutrophil-to-Lymphocyte Ratio is a strong predictor of atherosclerotic carotid plaques in older adults. Nutr. Metab. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2018, 28, 23–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, T.M.; Cheng, B.; Ke, L.; Guan, S.M.; Qi, B.L.; Li, W.Z.; Yang, B. Prognostic Value of Neutrophil to Lymphocyte Ratio for In-hospital Mortality in Elderly Patients with Acute Myocardial Infarction. Curr. Med. Sci. 2018, 38, 354–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xin, J.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, C.; Wang, Q. Predictive value of novel inflammatory markers combined with GRACE score for in-hospital outcome in patients with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction: A retrospective observational study. BMJ Open 2025, 15, e096621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Richardson, H.; Ho, V.; Pasquet, R.; Singh, R.J.; Goetz, M.P.; Tu, D.; Goss, P.E.; Ingle, J.N.; Investigators, M.A.P. Baseline estrogen levels in postmenopausal women participating in the MAP.3 breast cancer chemoprevention trial. Menopause 2020, 27, 693–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitacre, C.C. Sex differences in autoimmune disease. Nat. Immunol. 2001, 2, 777–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein, S.L.; Flanagan, K.L. Sex differences in immune responses. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2016, 16, 626–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stolfo, D.; Uijl, A.; Vedin, O.; Stromberg, A.; Faxen, U.L.; Rosano, G.M.C.; Sinagra, G.; Dahlstrom, U.; Savarese, G. Sex-Based Differences in Heart Failure Across the Ejection Fraction Spectrum: Phenotyping, and Prognostic and Therapeutic Implications. JACC Heart Fail. 2019, 7, 505–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeLeon-Pennell, K.Y.; Mouton, A.J.; Ero, O.K.; Ma, Y.; Padmanabhan Iyer, R.; Flynn, E.R.; Espinoza, I.; Musani, S.K.; Vasan, R.S.; Hall, M.E.; et al. LXR/RXR signaling and neutrophil phenotype following myocardial infarction classify sex differences in remodeling. Basic Res. Cardiol. 2018, 113, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Svedlund Eriksson, E.; Lantero Rodriguez, M.; Halvorsen, B.; Johansson, I.; Martensson, A.K.F.; Wilhelmson, A.S.; Huse, C.; Ueland, T.; Aukrust, P.; Broch, K.; et al. Testosterone exacerbates neutrophilia and cardiac injury in myocardial infarction via actions in bone marrow. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 1142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DeLeon-Pennell, K.Y.; Lindsey, M.L. Somewhere over the sex differences rainbow of myocardial infarction remodeling: Hormones, chromosomes, inflammasome, oh my. Expert Rev. Proteom. 2019, 16, 933–940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross, R. Atherosclerosis--an inflammatory disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 1999, 340, 115–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ridker, P.M.; Cushman, M.; Stampfer, M.J.; Tracy, R.P.; Hennekens, C.H. Inflammation, aspirin, and the risk of cardiovascular disease in apparently healthy men. N. Engl. J. Med. 1997, 336, 973–979, Correction in N. Engl. J. Med. 1997, 337, 356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, M. CANTOS: A breakthrough that proves the inflammatory hypothesis of atherosclerosis. Glob. Cardiol. Sci. Pract. 2018, 2018, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ridker, P.M.; Everett, B.M.; Thuren, T.; MacFadyen, J.G.; Chang, W.H.; Ballantyne, C.; Fonseca, F.; Nicolau, J.; Koenig, W.; Anker, S.D.; et al. Antiinflammatory Therapy with Canakinumab for Atherosclerotic Disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 2017, 377, 1119–1131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bossart, S.; Seyed Jafari, S.M.; Heidemeyer, K.; Yan, K.; Feldmeyer, L.; Borradori, L.; Yawalkar, N. Canakinumab leads to rapid reduction of neutrophilic inflammation and long-lasting response in Schnitzler syndrome. Front. Med. 2023, 10, 1050230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Katkenov, N.; Mukhatayev, Z.; Kozhakhmetov, S.; Sailybayeva, A.; Bekbossynova, M.; Kushugulova, A. Systematic Review on the Role of IL-6 and IL-1beta in Cardiovascular Diseases. J. Cardiovasc. Dev. Dis. 2024, 11, 206. [Google Scholar]

- Libby, P. Targeting Inflammatory Pathways in Cardiovascular Disease: The Inflammasome, Interleukin-1, Interleukin-6 and Beyond. Cells 2021, 10, 951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Libby, P.; Everett, B.M. Novel Antiatherosclerotic Therapies. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2019, 39, 538–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbate, A.; Trankle, C.R.; Buckley, L.F.; Lipinski, M.J.; Appleton, D.; Kadariya, D.; Canada, J.M.; Carbone, S.; Roberts, C.S.; Abouzaki, N.; et al. Interleukin-1 Blockade Inhibits the Acute Inflammatory Response in Patients with ST-Segment-Elevation Myocardial Infarction. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2020, 9, e014941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Lu, J.; Yin, Y.; Xie, J.; Xu, B. Anti-inflammatory mechanisms and research progress of colchicine in atherosclerotic therapy. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 2021, 25, 8087–8094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paschke, S.; Weidner, A.F.; Paust, T.; Marti, O.; Beil, M.; Ben-Chetrit, E. Technical advance: Inhibition of neutrophil chemotaxis by colchicine is modulated through viscoelastic properties of subcellular compartments. J. Leukoc. Biol. 2013, 94, 1091–1096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cronstein, B.N.; Molad, Y.; Reibman, J.; Balakhane, E.; Levin, R.I.; Weissmann, G. Colchicine alters the quantitative and qualitative display of selectins on endothelial cells and neutrophils. J. Clin. Investig. 1995, 96, 994–1002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez, G.J.; Celermajer, D.S.; Patel, S. The NLRP3 inflammasome and the emerging role of colchicine to inhibit atherosclerosis-associated inflammation. Atherosclerosis 2018, 269, 262–271, Correction in Atherosclerosis 2018, 273, 157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, H.; Khan, D.; Hussain, S.M.; Gerdes, N.; Hagenbeck, C.; Rana, M.; Cornelius, J.F.; Muhammad, S. Colchicine prevents oxidative stress-induced endothelial cell senescence via blocking NF-kappaB and MAPKs: Implications in vascular diseases. J. Inflamm. 2023, 20, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klingenberg, R.; Nitschmann, S. [Colchicine treatment after myocardial infarction: Colchicine Cardiovascular Outcomes Trial (COLCOT)]. Internist 2020, 61, 766–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samuel, M.; Tardif, J.C.; Khairy, P.; Roubille, F.; Waters, D.D.; Gregoire, J.C.; Pinto, F.J.; Maggioni, A.P.; Diaz, R.; Berry, C.; et al. Cost-effectiveness of low-dose colchicine after myocardial infarction in the Colchicine Cardiovascular Outcomes Trial (COLCOT). Eur. Heart J. Qual. Care Clin. Outcomes 2021, 7, 486–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hennessy, T.; Soh, L.; Bowman, M.; Kurup, R.; Schultz, C.; Patel, S.; Hillis, G.S. The Low Dose Colchicine after Myocardial Infarction (LoDoCo-MI) study: A pilot randomized placebo controlled trial of colchicine following acute myocardial infarction. Am. Heart J. 2019, 215, 62–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vrints, C.; Andreotti, F.; Koskinas, K.C.; Rossello, X.; Adamo, M.; Ainslie, J.; Banning, A.P.; Budaj, A.; Buechel, R.R.; Chiariello, G.A.; et al. 2024 ESC Guidelines for the management of chronic coronary syndromes. Eur. Heart J. 2024, 45, 3415–3537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broch, K.; Anstensrud, A.K.; Woxholt, S.; Sharma, K.; Tollefsen, I.M.; Bendz, B.; Aakhus, S.; Ueland, T.; Amundsen, B.H.; Damas, J.K.; et al. Randomized Trial of Interleukin-6 Receptor Inhibition in Patients with Acute ST-Segment Elevation Myocardial Infarction. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2021, 77, 1845–1855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ridker, P.M.; Devalaraja, M.; Baeres, F.M.M.; Engelmann, M.D.M.; Hovingh, G.K.; Ivkovic, M.; Lo, L.; Kling, D.; Pergola, P.; Raj, D.; et al. IL-6 inhibition with ziltivekimab in patients at high atherosclerotic risk (RESCUE): A double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled, phase 2 trial. Lancet 2021, 397, 2060–2069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wada, Y.; Jensen, C.; Meyer, A.S.P.; Zonoozi, A.A.M.; Honda, H. Efficacy and safety of interleukin-6 inhibition with ziltivekimab in patients at high risk of atherosclerotic events in Japan (RESCUE-2): A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 2 trial. J. Cardiol. 2023, 82, 279–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feng, Y.; Ye, D.; Wang, Z.; Pan, H.; Lu, X.; Wang, M.; Xu, Y.; Yu, J.; Zhang, J.; Zhao, M.; et al. The Role of Interleukin-6 Family Members in Cardiovascular Diseases. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2022, 9, 818890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ridker, P.M. From RESCUE to ZEUS: Will interleukin-6 inhibition with ziltivekimab prove effective for cardiovascular event reduction? Cardiovasc. Res. 2021, 117, e138–e140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ARTEMIS. A Research Study to Look at How Ziltivekimab Works Compared to Placebo in People with a Heart Attack. 2025. Available online: https://www.novonordisk-trials.com/trials-conditions/all-trials-v2/EX6018-4979.html (accessed on 14 September 2025).

- Petrie, M.B.B.; Buchholtz, K.; Ducharme, A.; Hvelplund, A.; Ping, C.L.S.; Mendieta, G.; Hardt-Lindberg, S.Ø.; Voors, A.A.; Ridker, P.M. HERMES: Effects of Ziltivekimab Versus Placebo On Morbidity and Mortality in Patients with Heart Failure with Mildly Reduced or Preserved Ejection Fraction and Systemic Inflammation. J. Card. Fail. 2024, 30, 126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coll, R.C.; Robertson, A.A.; Chae, J.J.; Higgins, S.C.; Munoz-Planillo, R.; Inserra, M.C.; Vetter, I.; Dungan, L.S.; Monks, B.G.; Stutz, A.; et al. A small-molecule inhibitor of the NLRP3 inflammasome for the treatment of inflammatory diseases. Nat. Med. 2015, 21, 248–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, R.; Shi, H.; Chang, S.; Gao, Y.; Li, X.; Lv, C.; Yang, H.; Xiang, H.; Yang, J.; Xu, L.; et al. The selective NLRP3-inflammasome inhibitor MCC950 reduces myocardial fibrosis and improves cardiac remodeling in a mouse model of myocardial infarction. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2019, 74, 105575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Guan, Y.; Liang, B.; Ding, P.; Hou, X.; Wei, W.; Ma, Y. Therapeutic potential of MCC950, a specific inhibitor of NLRP3 inflammasome. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2022, 928, 175091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Toldo, S.; Mauro, A.G.; Cutter, Z.; Van Tassell, B.W.; Mezzaroma, E.; Del Buono, M.G.; Prestamburgo, A.; Potere, N.; Abbate, A. The NLRP3 Inflammasome Inhibitor, OLT1177 (Dapansutrile), Reduces Infarct Size and Preserves Contractile Function After Ischemia Reperfusion Injury in the Mouse. J. Cardiovasc. Pharmacol. 2019, 73, 215–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gatlik, E.; Mehes, B.; Voltz, E.; Sommer, U.; Tritto, E.; Lestini, G.; Liu, X.; Pal, P.; Velinova, M.; Denney, W.S.; et al. First-in-human safety, tolerability, and pharmacokinetic results of DFV890, an oral low-molecular-weight NLRP3 inhibitor. Clin. Transl. Sci. 2024, 17, e13789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, D.M.; Byth, K.F.; Bertheloot, D.; Braams, S.; Bradley, S.; Dean, D.; Dekker, C.; El-Kattan, A.F.; Franchi, L.; Glick, G.D.; et al. Discovery of DFV890, a Potent Sulfonimidamide-Containing NLRP3 Inflammasome Inhibitor. J. Med. Chem. 2025, 68, 5529–5550, Correction in J. Med. Chem. 2025, 68, 7841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Inzucchi, S.E.; Kosiborod, M.; Fitchett, D.; Wanner, C.; Hehnke, U.; Kaspers, S.; George, J.T.; Zinman, B. Improvement in Cardiovascular Outcomes with Empagliflozin Is Independent of Glycemic Control. Circulation 2018, 138, 1904–1907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McMurray, J.J.V.; Solomon, S.D.; Inzucchi, S.E.; Kober, L.; Kosiborod, M.N.; Martinez, F.A.; Ponikowski, P.; Sabatine, M.S.; Anand, I.S.; Belohlavek, J.; et al. Dapagliflozin in Patients with Heart Failure and Reduced Ejection Fraction. N. Engl. J. Med. 2019, 381, 1995–2008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zinman, B.; Wanner, C.; Lachin, J.M.; Fitchett, D.; Bluhmki, E.; Hantel, S.; Mattheus, M.; Devins, T.; Johansen, O.E.; Woerle, H.J.; et al. Empagliflozin, Cardiovascular Outcomes, and Mortality in Type 2 Diabetes. N. Engl. J. Med. 2015, 373, 2117–2128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kounatidis, D.; Vallianou, N.; Evangelopoulos, A.; Vlahodimitris, I.; Grivakou, E.; Kotsi, E.; Dimitriou, K.; Skourtis, A.; Mourouzis, I. SGLT-2 Inhibitors and the Inflammasome: What’s Next in the 21st Century? Nutrients 2023, 15, 2294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopaschuk, G.D.; Verma, S. Mechanisms of Cardiovascular Benefits of Sodium Glucose Co-Transporter 2 (SGLT2) Inhibitors: A State-of-the-Art Review. JACC Basic Transl. Sci. 2020, 5, 632–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uthman, L.; Homayr, A.; Juni, R.P.; Spin, E.L.; Kerindongo, R.; Boomsma, M.; Hollmann, M.W.; Preckel, B.; Koolwijk, P.; van Hinsbergh, V.W.M.; et al. Empagliflozin and Dapagliflozin Reduce ROS Generation and Restore NO Bioavailability in Tumor Necrosis Factor alpha-Stimulated Human Coronary Arterial Endothelial Cells. Cell Physiol. Biochem. 2019, 53, 865–886. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.L.; Wang, T.Y.; Chen, Z.; Wang, H.W.; Yin, Y.; Wang, L.; Wang, Y.; Xu, B.; Xu, W. HMGB1-Promoted Neutrophil Extracellular Traps Contribute to Cardiac Diastolic Dysfunction in Mice. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2022, 11, e023800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, J.; Xu, H.; Wu, F.; Tu, Q.; Dong, X.; Xie, H.; Cao, Z. Empagliflozin inhibits macrophage inflammation through AMPK signaling pathway and plays an anti-atherosclerosis role. Int. J. Cardiol. 2022, 367, 56–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rykova, E.Y.; Klimontov, V.V.; Shmakova, E.; Korbut, A.I.; Merkulova, T.I.; Kzhyshkowska, J. Anti-Inflammatory Effects of SGLT2 Inhibitors: Focus on Macrophages. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 1670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, L.; Zhou, X.; Ji, W.J.; Lu, R.Y.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, Y.D.; Ma, Y.Q.; Zhao, J.H.; Li, Y.M. Neutrophil extracellular traps in ischemia-reperfusion injury-induced myocardial no-reflow: Therapeutic potential of DNase-based reperfusion strategy. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2015, 308, H500–H509. [Google Scholar]

- Potere, N.; Bonaventura, A.; Abbate, A. Novel Therapeutics and Upcoming Clinical Trials Targeting Inflammation in Cardiovascular Diseases. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2024, 44, 2371–2395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, X.L. DNase, ADAMTS13, and iPAD4: Good for the heart. Blood 2014, 123, 10–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jarrahi, A.; Khodadadi, H.; Moore, N.S.; Lu, Y.; Awad, M.E.; Salles, E.L.; Vaibhav, K.; Baban, B.; Dhandapani, K.M. Recombinant human DNase-I improves acute respiratory distress syndrome via neutrophil extracellular trap degradation. J. Thromb. Haemost. 2023, 21, 2473–2484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Z.; Gong, S.; Li, Y.; Yan, K.; Bao, Y.; Ning, K. Neutrophil Extracellular Traps in Atherosclerosis: Research Progress. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 2336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di, G.; Vazquez-Reyes, S.; Diaz, B.; Pena-Martinez, C.; Garcia-Culebras, A.; Cuartero, M.I.; Moraga, A.; Pradillo, J.M.; Esposito, E.; Lo, E.H.; et al. Daytime DNase-I Administration Protects Mice from Ischemic Stroke Without Inducing Bleeding or tPA-Induced Hemorrhagic Transformation, Even with Aspirin Pretreatment. Stroke 2025, 56, 527–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, M.; Yang, W.; Schmull, S.; Gu, J.; Xue, S. Inhibition of peptidyl arginine deiminase-4 protects against myocardial infarction induced cardiac dysfunction. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2020, 78, 106055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Knight, J.S.; Luo, W.; O’Dell, A.A.; Yalavarthi, S.; Zhao, W.; Subramanian, V.; Guo, C.; Grenn, R.C.; Thompson, P.R.; Eitzman, D.T.; et al. Peptidylarginine deiminase inhibition reduces vascular damage and modulates innate immune responses in murine models of atherosclerosis. Circ. Res. 2014, 114, 947–956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weipert, K.; Nef, H.; Voss, S.; Hoffmann, J.; Reischauer, S.; Rolf, A.; Troidl, K.; Wietelmann, A.; Hamm, C.W.; Sossalla, S.T.; et al. Antagonizing CCR2 with Propagermanium Leads to Altered Distribution of Macrophage Subsets and Favorable Tissue Remodeling After Myocardial Infarction in Mice. Cardiovasc. Ther. 2025, 2025, 8856808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaikita, K.; Hayasaki, T.; Okuma, T.; Kuziel, W.A.; Ogawa, H.; Takeya, M. Targeted deletion of CC chemokine receptor 2 attenuates left ventricular remodeling after experimental myocardial infarction. Am. J. Pathol. 2004, 165, 439–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, B.; Kasikara, C.; Doran, A.C.; Ramakrishnan, R.; Birge, R.B.; Tabas, I. MerTK signaling in macrophages promotes the synthesis of inflammation resolution mediators by suppressing CaMKII activity. Sci. Signal. 2018, 11, eaar3721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ciortan, L.; Macarie, R.D.; Barbu, E.; Naie, M.L.; Mihaila, A.C.; Serbanescu, M.; Butoi, E. Cross-Talk Between Neutrophils and Macrophages Post-Myocardial Infarction: From Inflammatory Drivers to Therapeutic Targets. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 10575. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262110575

Ciortan L, Macarie RD, Barbu E, Naie ML, Mihaila AC, Serbanescu M, Butoi E. Cross-Talk Between Neutrophils and Macrophages Post-Myocardial Infarction: From Inflammatory Drivers to Therapeutic Targets. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2025; 26(21):10575. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262110575

Chicago/Turabian StyleCiortan, Letitia, Razvan Daniel Macarie, Elena Barbu, Miruna Larisa Naie, Andreea Cristina Mihaila, Mihaela Serbanescu, and Elena Butoi. 2025. "Cross-Talk Between Neutrophils and Macrophages Post-Myocardial Infarction: From Inflammatory Drivers to Therapeutic Targets" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 26, no. 21: 10575. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262110575

APA StyleCiortan, L., Macarie, R. D., Barbu, E., Naie, M. L., Mihaila, A. C., Serbanescu, M., & Butoi, E. (2025). Cross-Talk Between Neutrophils and Macrophages Post-Myocardial Infarction: From Inflammatory Drivers to Therapeutic Targets. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 26(21), 10575. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262110575