Estimation of New Regulators of Iron Metabolism in Short-Term Follow-Up After Bariatric Surgery

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

3. Discussion

4. Material and Methods

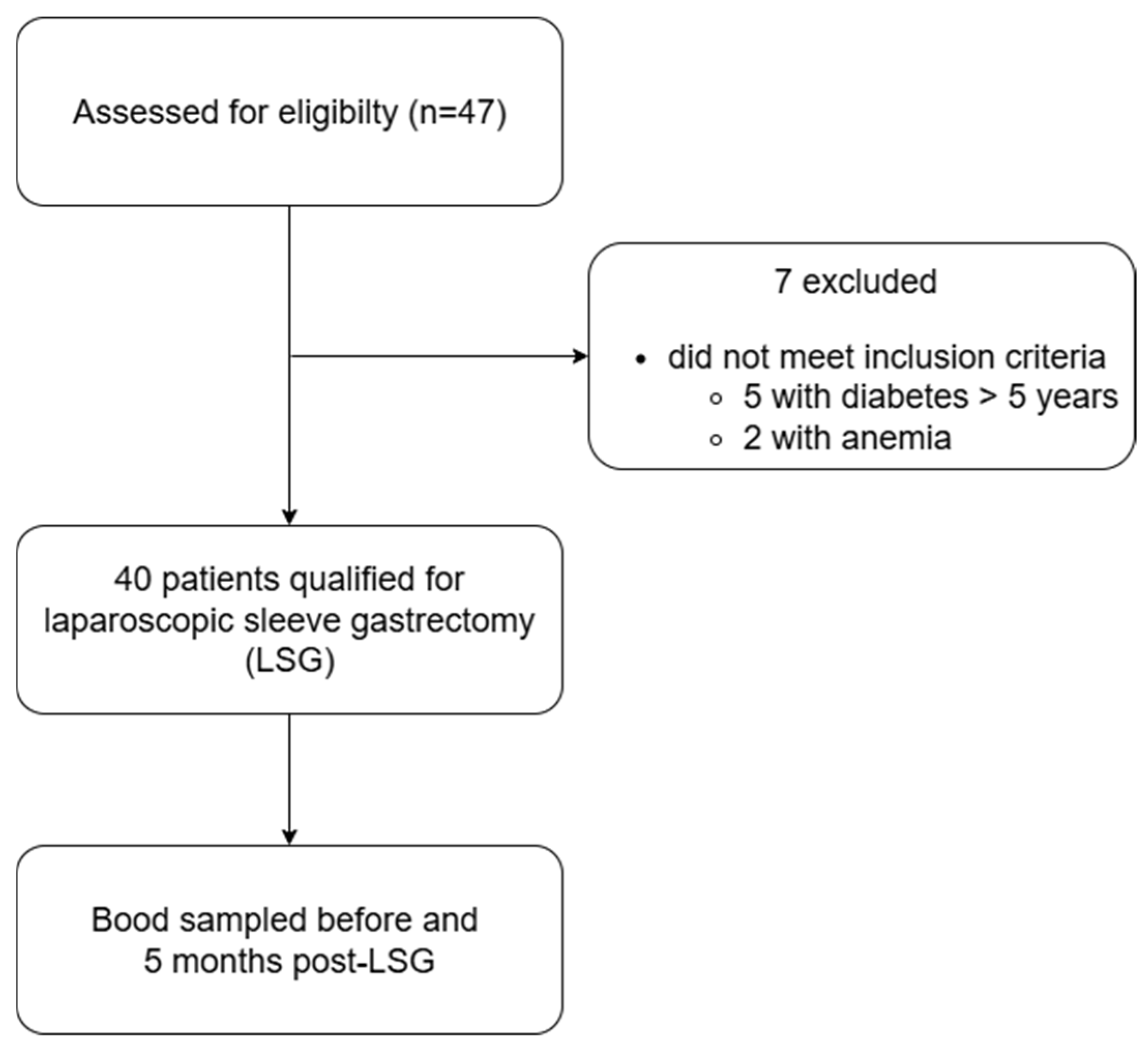

4.1. Study Population

4.2. Anthropometric and Body Composition Measurements

4.3. Laboratory Analysis

4.4. Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Berton, P.F.; Gambero, A. Hepcidin and inflammation associated with iron deficiency in childhood obesity—A systematic review. J. Pediatr. 2024, 100, 124–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kawai, T.; Autieri, M.V.; Scalia, R. Adipose tissue inflammation and metabolic dysfunction in obesity. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 2021, 320, C375–C391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ren, Y.; Zhao, H.; Yin, C.; Lan, X.; Wu, L.; Du, X.; Griffiths, H.R.; Gao, D. Adipokines, Hepatokines and Myokines: Focus on Their Role and Molecular Mechanisms in Adipose Tissue Inflammation. Front. Endocrinol. 2022, 13, 873699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Camaschella, C.; Nai, A.; Silvestri, L. Iron metabolism and iron disorders revisited in the hepcidin era. Haematologica 2020, 105, 260–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Domínguez, Á.; Visiedo-García, F.M.; Domínguez-Riscart, J.; González-Domínguez, R.; Mateos, R.M.; Lechuga-Sancho, A.M. Iron Metabolism in Obesity and Metabolic Syndrome. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 5529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bjørklund, G.; Peana, M.; Pivina, L.; Dosa, A.; Aaseth, J.; Semenova, Y.; Chirumbolo, S.; Medici, S.; Dadar, M.; Costea, D.O. Iron Deficiency in Obesity and after Bariatric Surgery. Biomolecules 2021, 11, 613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bekri, S.; Gual, P.; Anty, R.; Luciani, N.; Dahman, M.; Ramesh, B.; Iannelli, A.; Staccini-Myx, A.; Casanova, D.; Ben Amor, I.; et al. Increased adipose tissue expression of hepcidin in severe obesity is independent from diabetes and NASH. Gastroenterology 2006, 131, 788–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nemeth, E.; Ganz, T. Hepcidin-Ferroportin Interaction Controls Systemic Iron Homeostasis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 6493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nemeth, E.; Ganz, T. Hepcidin and Iron in Health and Disease. Annu. Rev. Med. 2023, 74, 261–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Britton, L.J.; Subramaniam, V.N.; Crawford, D.H. Iron and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. World J. Gastroenterol. 2016, 22, 8112–8122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Felsenreich, D.M.; Bichler, C.; Langer, F.B.; Gachabayov, M.; Prager, G. Sleeve Gastrectomy: Surgical Technique, Outcomes, and Complications. Surg. Technol. Int. 2020, 36, 63–69. [Google Scholar]

- Peterli, R.; Wölnerhanssen, B.K.; Vetter, D.; Nett, P.; Gass, M.; Borbély, Y.; Peters, T.; Schiesser, M.; Schultes, B.; Beglinger, C.; et al. Laparoscopic Sleeve Gastrectomy Versus Roux-Y-Gastric Bypass for Morbid Obesity-3-Year Outcomes of the Prospective Randomized Swiss Multicenter Bypass or Sleeve Study (SM-BOSS). Ann. Surg. 2017, 265, 466–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalinowski, P.; Paluszkiewicz, R.; Wróblewski, T.; Remiszewski, P.; Grodzicki, M.; Bartoszewicz, Z.; Krawczyk, M. Ghrelin, leptin, and glycemic control after sleeve gastrectomy versus Roux-en-Y gastric bypass-results of a randomized clinical trial. Surg. Obes. Relat. Dis. 2017, 13, 181–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salminen, P.; Grönroos, S.; Helmiö, M.; Hurme, S.; Juuti, A.; Juusela, R.; Peromaa-Haavisto, P.; Leivonen, M.; Nuutila, P.; Ovaska, J. Effect of Laparoscopic Sleeve Gastrectomy vs. Roux-en-Y Gastric Bypass on Weight Loss, Comorbidities, and Reflux at 10 Years in Adult Patients with Obesity: The SLEEVEPASS Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Surg. 2022, 157, 656–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lampropoulos, C.; Kehagias, D.; Bellou, A.; Markopoulos, G.; Papadopoulos, G.; Tsochatzis, S.; Kehagias, I. Critical Time Points for Assessing Long-Term Clinical Response After Sleeve Gastrectomy-A Retrospective Study of Patients with 13-Year Follow-Up. Obes. Surg. 2025, 35, 571–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulita, F.; Lampropoulos, C.; Kehagias, D.; Verras, G.I.; Tchabashvili, L.; Kaplanis, C.; Liolis, E.; Iliopoulos, F.; Perdikaris, I.; Kehagias, I. Long-term nutritional deficiencies following sleeve gastrectomy: A 6-year single-centre retrospective study. Prz. Menopauzalny 2021, 20, 170–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lowry, B.; Hardy, K.; Vergis, A. Iron deficiency in bariatric surgery patients: A single-centre experience over 5 years. Can. J. Surg. 2020, 63, E365–E369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kędzierska, K.; Dymkowski, M.; Niegowska, W.; Humięcka, M.; Sawicka, A.; Walczak, I.; Jędral, Z.M.; Wąsowski, M.; Bogołowska-Stieblich, A.; Binda, A.; et al. Iron Deficiency Anemia Following Bariatric Surgery: A 10-Year Prospective Observational Study. Nutrients 2025, 17, 339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gowanlock, Z.; Lezhanska, A.; Conroy, M.; Crowther, M.; Tiboni, M.; Mbuagbaw, L.; Siegal, D.M. Iron deficiency following bariatric surgery: A retrospective cohort study. Blood Adv. 2020, 4, 3639–3647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, C.; Xiao, T.; Hu, S.; Luo, H.; Lu, Q.; Fu, H.; Liang, D. Long-Term Outcomes of Iron Deficiency Before and After Bariatric Surgery: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Obes. Surg. 2023, 33, 897–910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tussing-Humphreys, L.M.; Nemeth, E.; Fantuzzi, G.; Freels, S.; Holterman, A.L.; Galvani, C.; Ayloo, S.; Vitello, J.; Braunschweig, C. Decreased serum hepcidin and improved functional iron status 6 months after restrictive bariatric surgery. Obesity 2010, 18, 2010–2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cepeda-Lopez, A.C.; Allende-Labastida, J.; Melse-Boonstra, A.; Osendarp, S.J.; Herter-Aeberli, I.; Moretti, D.; Rodriguez-Lastra, R.; Gonzalez-Salazar, F.; Villalpando, S.; Zimmermann, M.B. The effects of fat loss after bariatric surgery on inflammation, serum hepcidin, and iron absorption: A prospective 6-mo iron stable isotope study. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2016, 104, 1030–1038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marin, F.A.; Verlengia, R.; Crisp, A.H.; Sousa Novais, P.F.; Rasera-Junior, I.; De Oliveira, M.R.M. Micronutrient supplementation in gastric bypass surgery: Prospective study on inflammation and iron metabolism in premenopausal women. Nutr. Hosp. 2017, 34, 369–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wiese, M.L.; Wilke, F.; Gärtner, S.; Valentini, L.; Keßler, W.; Aghdasssi, A.A.; Lerch, M.M.; Steveling, A. Associations of age, sex, and socioeconomic status with adherence to guideline recommendations on protein intake and micronutrient supplementation in patients with sleeve gastrectomy or Roux-en-Y gastric bypass. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0282683, Correction in PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0314699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Misra, S.; Balasubramanian, S.; Isaac, U.; Srinivasan, M.; Saminathan, C.; Kumar, S.S.; Raj, P.P. Is the Current Micronutrient Supplementation Adequate in Preventing Deficiencies in Indian Patients? Short- and Mid-Term Comparison of Sleeve Gastrectomy and Roux-en-Y Gastric Bypass. Obes. Surg. 2020, 30, 3480–3488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pihan-Le Bars, F.; Bonnet, F.; Loréal, O.; Le Loupp, A.G.; Ropert, M.; Letessier, E.; Prieur, X.; Bach, K.; Deugnier, Y.; Fromenty, B.; et al. Indicators of iron status are correlated with adiponectin expression in adipose tissue of patients with morbid obesity. Diabetes Metab. 2016, 42, 105–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gajewska, J.; Ambroszkiewicz, J.; Klemarczyk, W.; Głąb-Jabłońska, E.; Weker, H.; Chełchowska, M. Ferroportin-Hepcidin Axis in Prepubertal Obese Children with Sufficient Daily Iron Intake. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 2156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aschemeyer, S.; Qiao, B.; Stefanova, D.; Valore, E.V.; Sek, A.C.; Ruwe, T.A.; Vieth, K.R.; Jung, G.; Casu, C.; Rivella, S.; et al. Structure-function analysis of ferroportin defines the binding site and an alternative mechanism of action of hepcidin. Blood 2018, 131, 899–910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luciani, N.; Brasse-Lagnel, C.; Poli, M.; Anty, R.; Lesueur, C.; Cormont, M.; Laquerriere, A.; Folope, V.; LeMarchand-Brustel, Y.; Gugenheim, J.; et al. Hemojuvelin: A new link between obesity and iron homeostasis. Obesity 2011, 19, 1545–1551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutema, B.T.; Sorrie, M.B.; Megersa, N.D.; Yesera, G.E.; Yeshitila, Y.G.; Pauwels, N.S.; De Henauw, S.; Abbeddou, S. Effects of iron supplementation on cognitive development in school-age children: Systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0287703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Wang, C.; Li, X.; Guo, J.; Dove, A.; Cui, Z.; Xu, W. Association of Anemia with Cognitive Function and Dementia Among Older Adults: The Role of Inflammation. J. Alzheimer’s Dis. 2023, 96, 125–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di Lorenzo, N.; Antoniou, S.A.; Batterham, R.L.; Busetto, L.; Godoroja, D.; Iossa, A.; Carrano, F.M.; Agresta, F.; Alarçon, I.; Azran, C.; et al. Clinical practice guidelines of the European association for endoscopic surgery (EAES) on bariatric surgery: Update 2020 endorsed by IFSO-EC, EASO and ESPCOP. Surg. Endosc. 2020, 34, 2332–2358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Szeliga, J.; Wyleżoł, M.; Major, P.; Budzyński, A.; Binda, A.; Proczko-Stepaniak, M.; Boniecka, I.; Matłok, M.; Sekuła, M.; Kaska, Ł.; et al. Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery Chapter of the Association of Polish Surgeons. Bariatric and metabolic surgery care standards. Videosurg. Other Miniinvasive Tech. 2020, 3, 391–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Variable | Preoperative | 5 Months Postoperative | Z | p-Value | r |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, y | 41 (33–45) | - | - | ||

| Male-sex, n (%) | 12 (30) | - | - | ||

| Height, m | 1.71 (1.63–1.79) | - | - | ||

| Weight, kg | 114 (103–134) | 88 (78–109) | 5.44 | <0.0001 | 0.87 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 38.8 (36.1–44.1) | 29.8 (27.6–35.7) | 5.44 | <0.0001 | 0.87 |

| MBF, kg | 46.50 (41.40–52.70) | 29.00 (25.00–37.40) | 5.44 | <0.0001 | 0.87 |

| PBF, % | 42.60 (34.80–44.70) | 33.60 (28.80–38.20) | 5.44 | <0.0001 | 0.87 |

| ECW, kg | 19.00 (17.20–24.60) | 16.35 (15.10–22.40) | 5.23 | <0.0001 | 0.85 |

| ICW, kg | 27.40 (25.40–35.90) | 23.75 (21.80–32.30) | 5.32 | <0.0001 | 0.86 |

| EW, kg | 48.30 (39.40–64.90) | 22.05 (16.30–38.30) | 5.37 | <0.0001 | 0.87 |

| Biochemical markers | |||||

| ALT, U/L | 28.50 (21.50–41.0) | 19.50 (13.00–24.00) | 4.89 | <0.0001 | 0.77 |

| AST, U/L | 24.00 (21.00–29.50) | 20.50 (19.00–26.00) | 2.85 | 0.0044 | 0.48 |

| Urea, mg/dL | 27.55 (24.30–32.80) | 24.80 (21.70–29.70) | 2.38 | 0.0174 | 0.38 |

| Creatinine, mg/dL | 0.72 (0.65–0.85) | 0.71 (0.67–0.83) | 0.17 | 0.8618 | 0.03 |

| Folic acid, ng/mL | 7.50 (5.40–10.20) | 7.85 (5.45–13.45) | 2.06 | 0.0391 | 0.33 |

| Vitamin B12, pg/mL | 363.00 (266.5–433.0) | 339.50 (291.0–401.0) | 0.58 | 0.5625 | 0.09 |

| Comorbidities | |||||

| Hypertension, n (%) | 20 (50) | - | - | ||

| Diabetes mellitus, n (%) | 6 (15) | - | - | ||

| Hypothyroidism, n (%) | 10 (25) | - | - | ||

| PCOS, n (%) | 2 (0.5) | - | - | ||

| Dyslipidemia, n (%) | 2 (0.5) | - | - | ||

| Variable | Preoperative | 5 Months Postoperative | Z | p-Value | r |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Complete blood count | |||||

| RBC, 1012/L | 4.89 (4.52–5.13) | 4.81 (4.41–5.03) | 1.36 | 0.1736 | 0.22 |

| HGB, g/dL | 14.15 (13.25–15.10) | 14.00 (13.05–15.00) | 1.11 | 0.2672 | 0.18 |

| HCT, % | 40.95 (38.90–43.70) | 41.30 (38.85–43.75) | 0.41 | 0.6794 | 0.07 |

| MCV, fL | 83.80 (82.55–86.20) | 86.35 (84.45–87.85) | 4.33 | 0.0002 | 0.69 |

| MCH, pg | 29.20 (28.25–29.75) | 29.60 (28.70–30.10) | 2.64 | 0.0084 | 0.42 |

| MCHC, g/dL | 34.30 (33.80–35.00) | 34.20 (33.75–34.60) | 3.20 | 0.0014 | 0.51 |

| RDW-SD fL | 40.15 (38.90–42.25) | 41.40 (40.20–43.85) | 3.90 | 0.0001 | 0.62 |

| Iron regulatory parameters | |||||

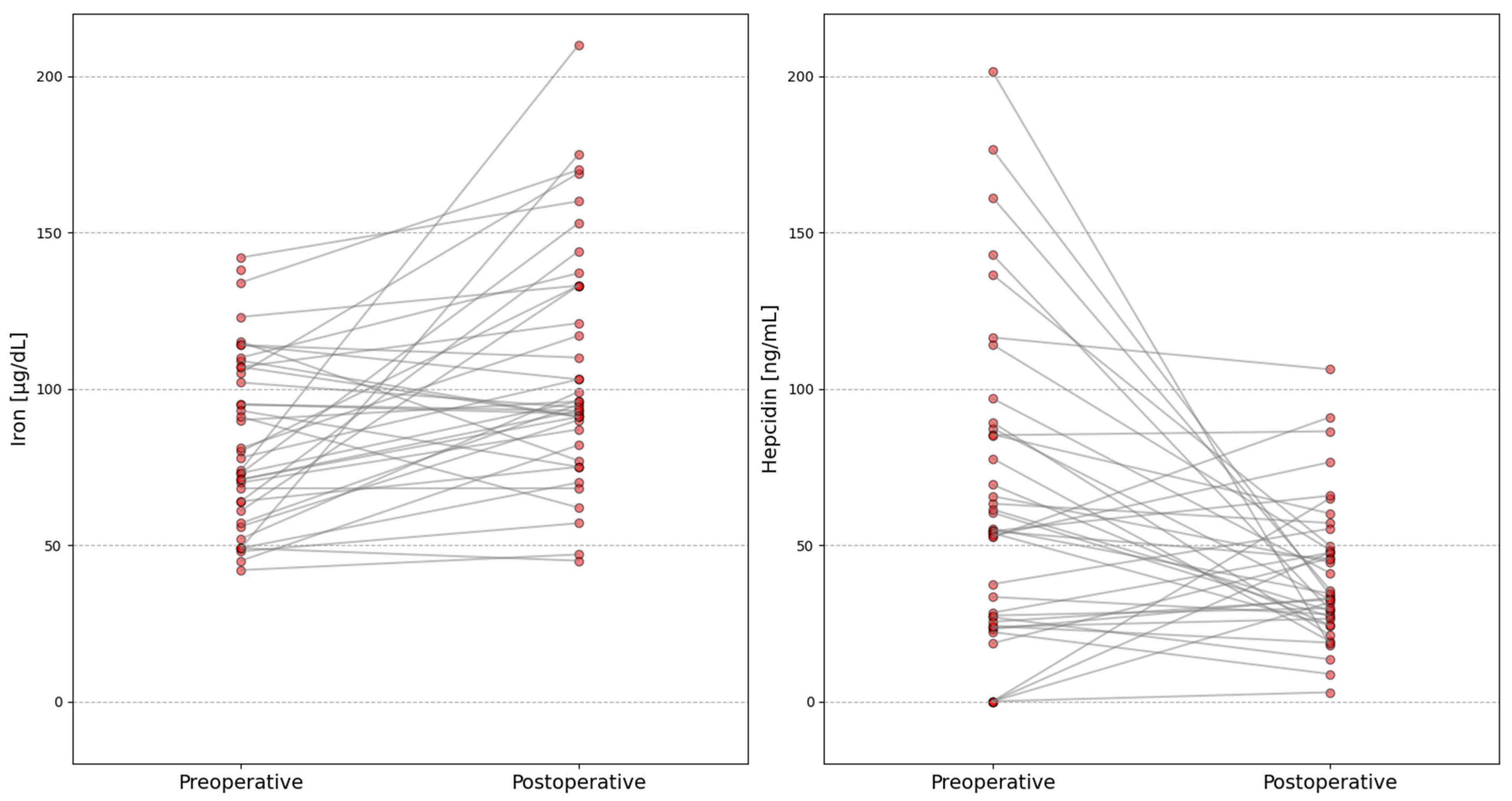

| Iron, µg/dL | 79.00 (62.50–107.00) | 95.00 (82.00–133.00) | 3.15 | 0.0016 | 0.51 |

| Erythroferron, ng/mL | 0.99 (0.60–1.72) | 1.06 (0.65–2.39) | 0.96 | 0.3385 | 0.16 |

| Hepcidin, ng/mL | 54.46 (26.18–86.36) | 33.88 (26.44–49.72) | 2.37 | 0.0177 | 0.38 |

| Soluble hemojuvelin, ng/mL | 15.10 (8.31–18.37) | 11.64 (6.57–15.01) | 0.85 | 0.3971 | 0.13 |

| Ferroportin, ng/mL | 0.01 (0.01–0.03) | 0.02 (0.02–0.03) | 0.32 | 0.7457 | 0.06 |

| Transferrin, ng/mL | 940.91 (534.18–1389.61) | 1073.14 (809.43–1539.54) | 0.83 | 0.4046 | 0.13 |

| R | p | |

|---|---|---|

| ΔMBF and ΔHepcidin | 0.36 | 0.0228 |

| ΔPBF and ΔHepcidin | 0.42 | 0.0070 |

| ΔMBF and ΔSoluble hemojuvelin | 0.31 | 0.0489 |

| ΔPBF and ΔSoluble hemojuvelin | 0.45 | 0.0032 |

| ΔPBF and ΔTransferrin | −0.37 | 0.0192 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kupczyk, W.; Boinska, J.; Słomka, A.; Kupczyk, K.; Jackowski, M.; Żekanowska, E. Estimation of New Regulators of Iron Metabolism in Short-Term Follow-Up After Bariatric Surgery. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 10543. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262110543

Kupczyk W, Boinska J, Słomka A, Kupczyk K, Jackowski M, Żekanowska E. Estimation of New Regulators of Iron Metabolism in Short-Term Follow-Up After Bariatric Surgery. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2025; 26(21):10543. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262110543

Chicago/Turabian StyleKupczyk, Wojciech, Joanna Boinska, Artur Słomka, Kinga Kupczyk, Marek Jackowski, and Ewa Żekanowska. 2025. "Estimation of New Regulators of Iron Metabolism in Short-Term Follow-Up After Bariatric Surgery" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 26, no. 21: 10543. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262110543

APA StyleKupczyk, W., Boinska, J., Słomka, A., Kupczyk, K., Jackowski, M., & Żekanowska, E. (2025). Estimation of New Regulators of Iron Metabolism in Short-Term Follow-Up After Bariatric Surgery. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 26(21), 10543. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262110543