The Role of PI3K/AKT/mTOR Signaling in Hepatocellular Carcinoma Metabolism

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. The PI3K/AKT/mTOR Pathway in HCC

3. The Role of Metabolic Pathways in HCC

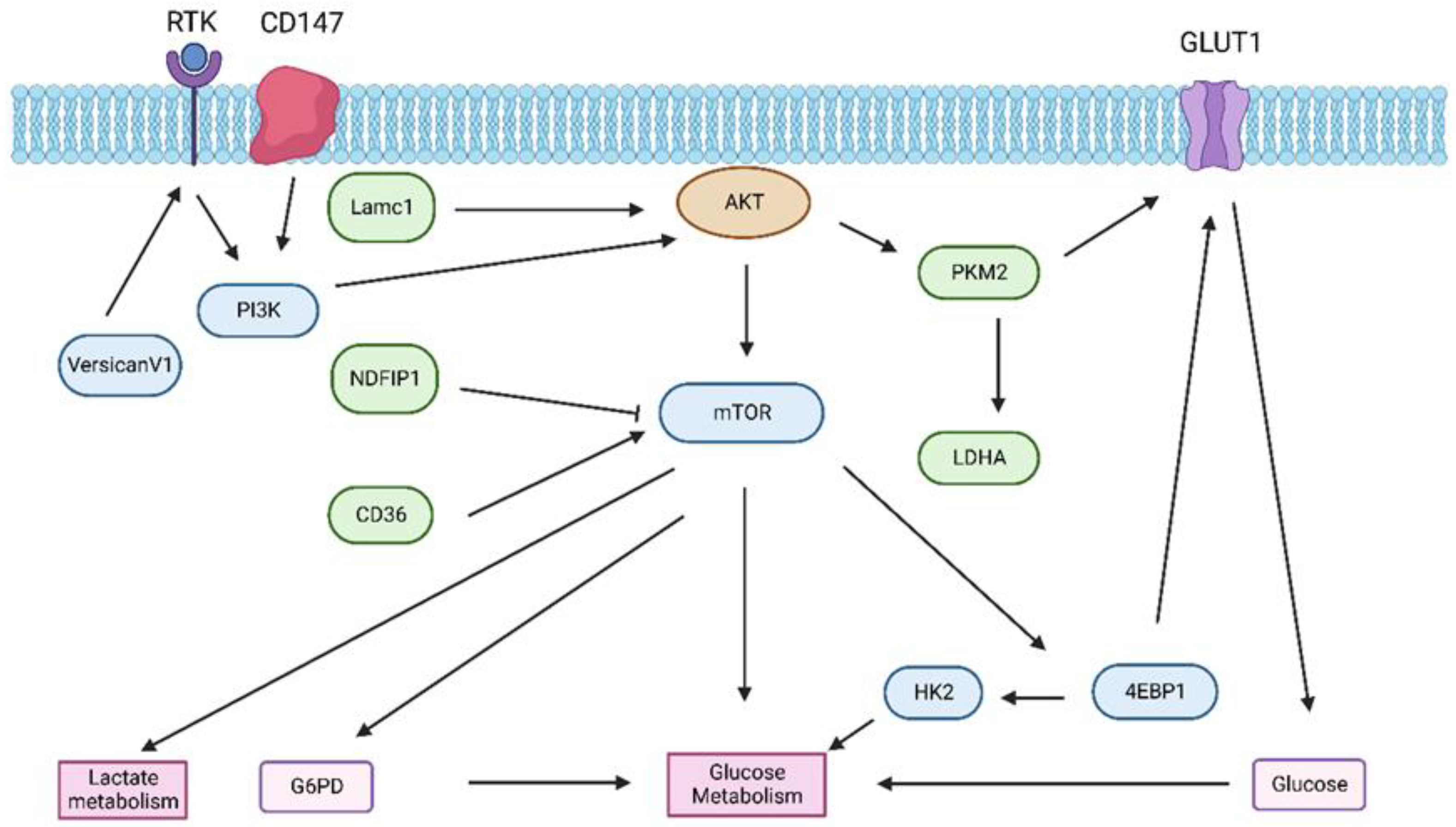

3.1. Glucose Metabolism in HCC

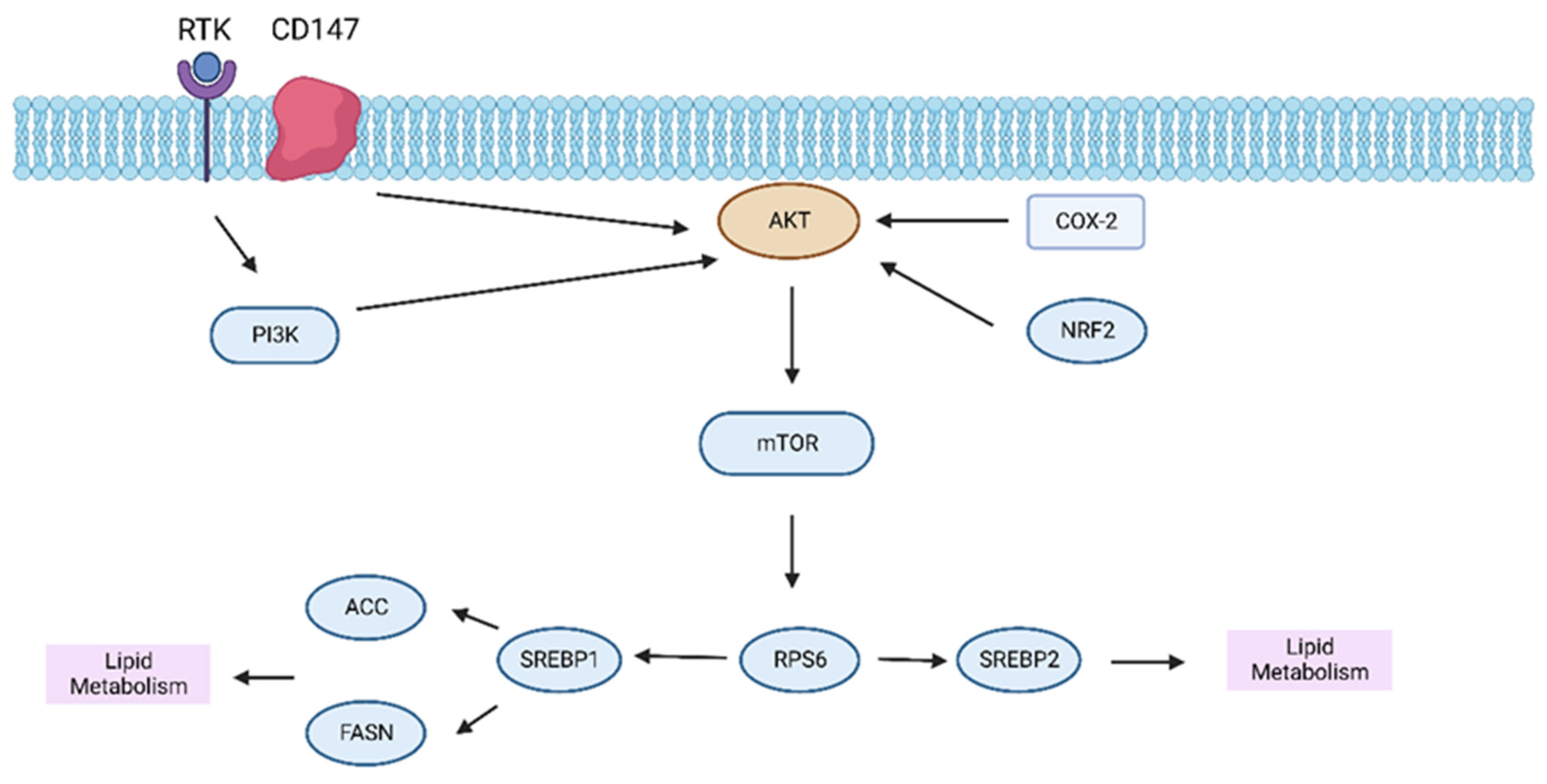

3.2. Lipid Metabolism in HCC

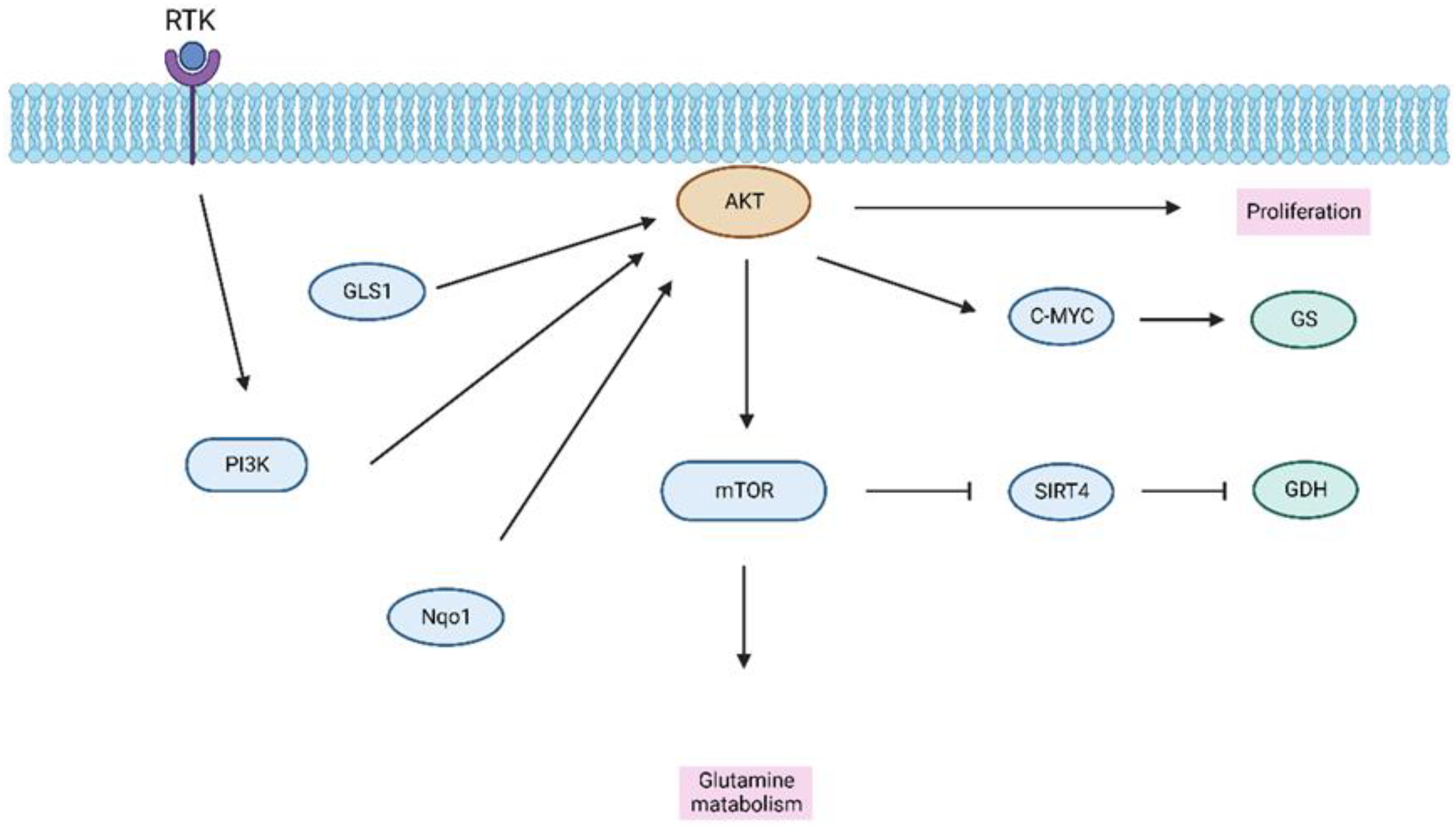

3.3. Amino Acid Metabolism in HCC

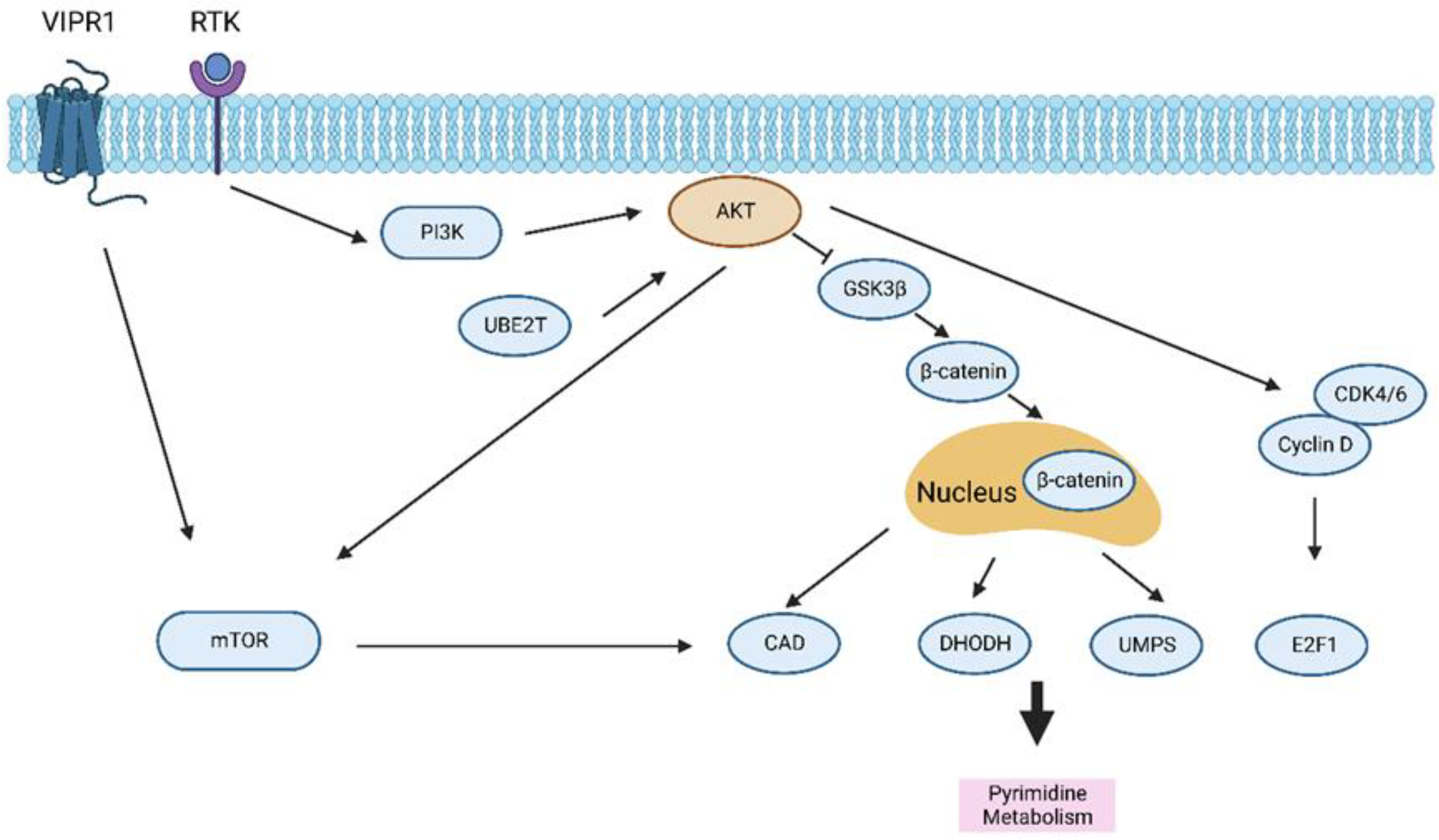

3.4. Pyrimidine Metabolism in HCC

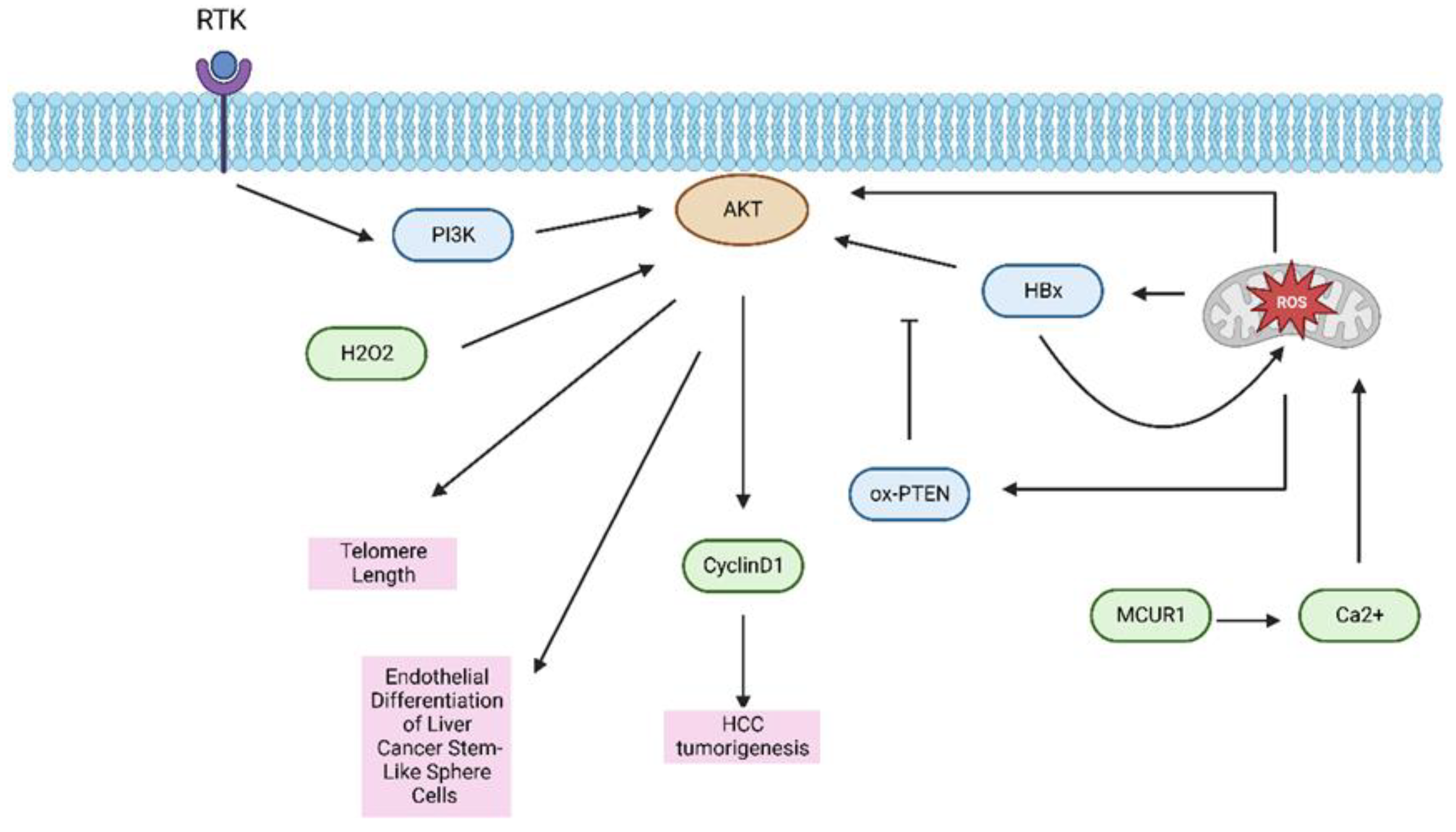

3.5. Oxidative Metabolism in HCC

4. Metabolic Reprogramming in the HCC Tumor Microenvironment

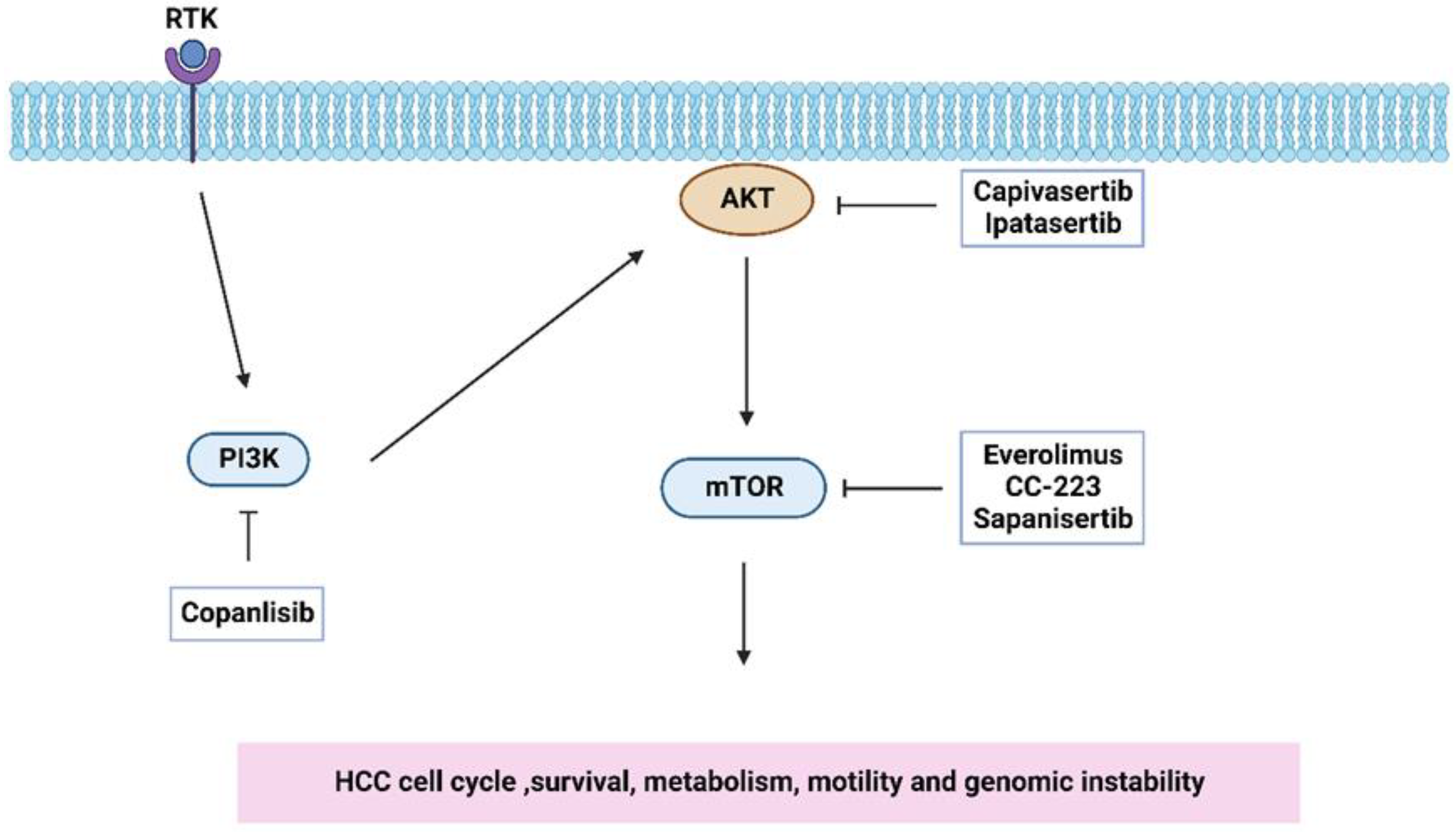

5. Targeting the PI3K/AKT/mTOR Pathway for HCC Therapy

6. Present Challenges and Future Directions

7. Summary and Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| 4EBP1 | 4E binding protein 1 |

| 6PGD | 6-phosphogluconate dehydrogenase |

| ACC | Acetyl-CoA-carboxylase |

| AMPK | AMP-activated kinase |

| ASNS | Activation of asparagine synthetase |

| CAD | Carbamoyl-phosphate synthetase 2, aspartate transcarbamoylase, dihydroorotase |

| COX-2 | Cyclooxygenase 2 |

| CSCs | Cancer stem cells |

| DHODH | Dihydroorotate dehydrogenase |

| EGFR | Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor |

| FASN | Fatty acid synthesis |

| GDH | Glutamate dehydrogenase |

| GLS1 | Glutaminase 1 |

| GLUT1 | Glucose transporter 1 |

| GS | Glutamine synthetase |

| HBx | hepatitis B x protein |

| HCC | Hepatocellular carcinoma |

| HCV | Hepatitis C virus |

| HK2 | Hexokinase 2 |

| IL-6 | Interleukin 6 |

| IRI | Ischemia–reperfusion injury |

| Lamc1 | Laminin gamma 1 |

| LT | liver transplantation |

| MCUR1 | Mitochondrial calcium uniporter regulator 1 |

| mTOR | Mammalian target of rapamycin |

| NAFLD | non-alcoholic fatty liver disease |

| NDFIP1 | Nedd4 family-interacting protein 1 |

| NDRG2 | N-Myc downstream regulated gene 2 |

| NK cell | Natural killer cell |

| Nqo1 | NAD(P)H quinone dehydrogenase 1 |

| NRF2 | Nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2 |

| OXPHOS | Oxidative phosphorylation |

| PDGFR | Platelet-derived growth factor receptors |

| PD-L1 | Programmed death ligand 1 |

| PHLDA3 | Pleckstrin Homology Like Domain Family A Member 3 |

| PI3K | Phosphatidylinositol 3-Kinase |

| PKB | Protein kinase B |

| PLC | Primary liver cancer |

| PPP | Pentose phosphate pathway |

| PTEN | Phosphatase and tensin homolog |

| ROS | Reactive oxygen species |

| S6K1 | Protein S6 kinase 1 |

| SIRT4 | Sirtuin 4 |

| SREBP1 | Sterol regulatory-element binding protein 1 |

| SREBP2 | Sterol regulatory-element binding protein 2 |

| SREBPs | Sterol regulatory-element binding proteins |

| STAT3 | Signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 |

| TCA | Tricarboxylic acid |

| TIRM21 | Tripartite motif-containing protein 21 |

| TME | Tumor microenvironment |

| Treg cell | T regulatory cell |

| UBE2T | Ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme E2T |

| UMPS | Uridine 5′-monophosphate synthase |

| VEGFA | Vascular endothelial growth factor A |

| VIPR1 | Vasoactive intestinal polypeptide type-I receptor |

References

- Choo, S.P.; Tan, W.L.; Goh, B.K.P.; Tai, W.M.; Zhu, A.X. Comparison of hepatocellular carcinoma in Eastern versus Western populations. Cancer 2016, 122, 3430–3446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y.L.; Li, L.; Jia, Y.X.; Zhang, B.Z.; Li, J.C.; Zhu, Y.H.; Li, M.Q.; He, J.Z.; Zeng, T.T.; Ban, X.J.; et al. LINC01554-Mediated Glucose Metabolism Reprogramming Suppresses Tumorigenicity in Hepatocellular Carcinoma via Downregulating PKM2 Expression and Inhibiting Akt/mTOR Signaling Pathway. Theranostics 2019, 9, 796–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forner, A.; Reig, M.; Bruix, J. Hepatocellular carcinoma. Lancet 2018, 391, 1301–1314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Faubert, B.; Solmonson, A.; DeBerardinis, R.J. Metabolic reprogramming and cancer progression. Science 2020, 368, 5473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yeh, Y.C.; Ho, H.L.; Wu, Y.C.; Pan, C.C.; Wang, Y.C.; Chou, T.Y. AKT1 internal tandem duplications and point mutations are the genetic hallmarks of sclerosing pneumocytoma. Mod. Pathol. 2020, 33, 391–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cai, J.; Sun, X.; Guo, H.; Qu, X.; Huang, H.; Yu, C.; Wu, H.; Gao, Y.; Kong, X.; Xia, Q. Non-metabolic role of UCK2 links EGFR-AKT pathway activation to metastasis enhancement in hepatocellular carcinoma. Oncogenesis 2020, 9, 103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Honigova, K.; Navratil, J.; Peltanova, B.; Polanska, H.H.; Raudenska, M.; Masarik, M. Metabolic tricks of cancer cells. Biochim. Biophys Acta Rev. Cancer 2022, 1877, 188705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stine, Z.E.; Schug, Z.T.; Salvino, J.M.; Dang, C.V. Targeting cancer metabolism in the era of precision oncology. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2022, 21, 141–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Icard, P.; Simula, L.; Wu, Z.; Berzan, D.; Sogni, P.; Dohan, A.; Dautry, R.; Coquerel, A.; Lincet, H.; Loi, M.; et al. Why may citrate sodium significantly increase the effectiveness of transarterial chemoembolization in hepatocellular carcinoma? Drug Resist. Updat. 2021, 59, 100790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, M.; Wong, T.L.; Zhao, H.; Zheng, Y.; Xie, Y.N.; Li, C.H.; Zhou, L.; Che, N.; Yun, J.P.; Man, K.; et al. Loss of tyrosine catabolic enzyme HPD promotes glutamine anaplerosis through mTOR signaling in liver cancer. Cell Rep. 2021, 36, 109617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buontempo, F.; Ersahin, T.; Missiroli, S.; Senturk, S.; Etro, D.; Ozturk, M.; Capitani, S.; Cetin-Atalay, R.; Neri, M.L. Inhibition of Akt signaling in hepatoma cells induces apoptotic cell death independent of Akt activation status. Invest. New. Drugs 2011, 29, 1303–1313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, J.; Oh, M.; Kim, S.Y.; Oh, Y.J.; Oh, B.; Oh, J.H.; Kim, W.; Jung, J.H.; Kim, H.I.; Kim, J.S.; et al. PET-Based Radiogenomics Supports mTOR Pathway Targeting for Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Clin. Cancer Res. 2022, 28, 1821–1831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, C.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, L.; Zhu, A.X.; Bernards, R.; Qin, W.; Wang, C. Evolving therapeutic landscape of advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2022, 22, 704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fruman, D.A.; Rommel, C. PI3K and cancer: Lessons, challenges and opportunities. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2014, 13, 140–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fruman, D.A.; Chiu, H.; Hopkins, B.D.; Bagrodia, S.; Cantley, L.C.; Abraham, R.T. The PI3K Pathway in Human Disease. Cell 2017, 170, 605–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ellis, H.; Ma, C.X. PI3K Inhibitors in Breast Cancer Therapy. Curr. Oncol. Rep. 2019, 21, 110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vanhaesebroeck, B.; Guillermet-Guibert, J.; Graupera, M.; Bilanges, B. The emerging mechanisms of isoform-specific PI3K signalling. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2010, 11, 329–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thorpe, L.M.; Yuzugullu, H.; Zhao, J.J. PI3K in cancer: Divergent roles of isoforms, modes of activation and therapeutic targeting. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2015, 15, 7–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Zheng, L.; Zhang, R.; Hou, P.; Wang, J.; Wu, L.; Li, J. Circ-ZEB1 promotes PIK3CA expression by silencing miR-199a-3p and affects the proliferation and apoptosis of hepatocellular carcinoma. Mol. Cancer 2022, 21, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xin, Z.; Li, J.; Zhang, H.; Zhou, Y.; Song, J.; Chen, P.; Bai, L.; Chen, H.; Zhou, J.; Chen, J.; et al. Cancer Genomic Alterations Can Be Potential Biomarkers Predicting Microvascular Invasion and Early Recurrence of Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Front Oncol. 2022, 12, 783109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, C.; Yuan, G.; Hu, Y.; Wang, D.; Shi, X.; Zhu, D.; Hu, A.; Meng, Y.; Lu, J. Repressing phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate 3-kinase catalytic subunit gamma by microRNA-142-3p restrains the progression of hepatocellular carcinoma. Bioengineered 2022, 13, 1491–1506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fang, Y.; Xue, J.L.; Shen, Q.; Chen, J.; Tian, L. MicroRNA-7 inhibits tumor growth and metastasis by targeting the phosphoinositide 3-kinase/Akt pathway in hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology 2012, 55, 1852–1862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gulluni, F.; De Santis, M.C.; Margaria, J.P.; Martini, M.; Hirsch, E. Class II PI3K Functions in Cell Biology and Disease. Trends Cell Biol. 2019, 29, 339–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chai, Z.T.; Kong, J.; Zhu, X.D.; Zhang, Y.Y.; Lu, L.; Zhou, J.M.; Wang, L.R.; Zhang, K.Z.; Zhang, Q.B.; Ao, J.Y.; et al. MicroRNA-26a inhibits angiogenesis by down-regulating VEGFA through the PIK3C2alpha/Akt/HIF-1alpha pathway in hepatocellular carcinoma. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e77957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maehama, T.; Fukasawa, M.; Date, T.; Wakita, T.; Hanada, K. A class II phosphoinositide 3-kinase plays an indispensable role in hepatitis C virus replication. Biochem. Biophys Res. Commun. 2013, 440, 150–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ronan, B.; Flamand, O.; Vescovi, L.; Dureuil, C.; Durand, L.; Fassy, F.; Bachelot, M.F.; Lamberton, A.; Mathieu, M.; Bertrand, T.; et al. A highly potent and selective Vps34 inhibitor alters vesicle trafficking and autophagy. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2014, 10, 1013–1019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, F.; Wu, X.; Qian, Y.; Jiang, X.; Wang, Y.; Gao, J. PIK3C3 regulates the expansion of liver CSCs and PIK3C3 inhibition counteracts liver cancer stem cell activity induced by PI3K inhibitor. Cell Death Dis. 2020, 11, 427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasudevan, K.M.; Barbie, D.A.; Davies, M.A.; Rabinovsky, R.; McNear, C.J.; Kim, J.J.; Hennessy, B.T.; Tseng, H.; Pochanard, P.; Kim, S.Y.; et al. AKT-independent signaling downstream of oncogenic PIK3CA mutations in human cancer. Cancer Cell 2009, 16, 21–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Q.; Yu, W.N.; Chen, X.; Peng, X.D.; Jeon, S.M.; Birnbaum, M.J.; Guzman, G.; Hay, N. Spontaneous Hepatocellular Carcinoma after the Combined Deletion of Akt Isoforms. Cancer Cell 2016, 29, 523–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.; Xu, M.; Liu, P.; Zhang, S.; Shang, R.; Qiao, Y.; Che, L.; Ribback, S.; Cigliano, A.; Evert, K.; et al. The mTORC2-Akt1 Cascade Is Crucial for c-Myc to Promote Hepatocarcinogenesis in Mice and Humans. Hepatology 2019, 70, 1600–1613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Sakon, M.; Nagano, H.; Hiraoka, N.; Yamamoto, H.; Hayashi, N.; Dono, K.; Nakamori, S.; Umeshita, K.; Ito, Y.; et al. Akt2 expression correlates with prognosis of human hepatocellular carcinoma. Oncol. Rep. 2004, 11, 25–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galicia, V.A.; He, L.; Dang, H.; Kanel, G.; Vendryes, C.; French, B.A.; Zeng, N.; Bayan, J.A.; Ding, W.; Wang, K.S.; et al. Expansion of hepatic tumor progenitor cells in Pten-null mice requires liver injury and is reversed by loss of AKT2. Gastroenterology 2010, 139, 2170–2182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hsieh, A.C.; Liu, Y.; Edlind, M.P.; Ingolia, N.T.; Janes, M.R.; Sher, A.; Shi, E.Y.; Stumpf, C.R.; Christensen, C.; Bonham, M.J.; et al. The translational landscape of mTOR signalling steers cancer initiation and metastasis. Nature 2012, 485, 55–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hara, K.; Maruki, Y.; Long, X.; Yoshino, K.; Oshiro, N.; Hidayat, S.; Tokunaga, C.; Avruch, J.; Yonezawa, K. Raptor, a binding partner of target of rapamycin (TOR), mediates TOR action. Cell 2002, 110, 177–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dancey, J. mTOR signaling and drug development in cancer. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 2010, 7, 209–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Golob-Schwarzl, N.; Krassnig, S.; Toeglhofer, A.M.; Park, Y.N.; Gogg-Kamerer, M.; Vierlinger, K.; Schroder, F.; Rhee, H.; Schicho, R.; Fickert, P.; et al. New liver cancer biomarkers: PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway members and eukaryotic translation initiation factors. Eur. J. Cancer 2017, 83, 56–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhat, M.; Sonenberg, N.; Gores, G.J. The mTOR pathway in hepatic malignancies. Hepatology 2013, 58, 810–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Umemura, A.; Park, E.J.; Taniguchi, K.; Lee, J.H.; Shalapour, S.; Valasek, M.A.; Aghajan, M.; Nakagawa, H.; Seki, E.; Hall, M.N.; et al. Liver damage, inflammation, and enhanced tumorigenesis after persistent mTORC1 inhibition. Cell Metab. 2014, 20, 133–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guri, Y.; Colombi, M.; Dazert, E.; Hindupur, S.K.; Roszik, J.; Moes, S.; Jenoe, P.; Heim, M.H.; Riezman, I.; Riezman, H.; et al. mTORC2 Promotes Tumorigenesis via Lipid Synthesis. Cancer Cell 2017, 32, 807–823 e812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, X.Y.; Yuan, X.M.; Xu, Y.Y.; Yin, M.; Yan, W.W.; Zou, S.W.; Wei, L.M.; Lu, H.J.; Wang, Y.P.; Lei, Q.Y. CARM1 Methylates GAPDH to Regulate Glucose Metabolism and Is Suppressed in Liver Cancer. Cell Rep. 2018, 24, 3207–3223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.; Che, L.; Li, L.; Pilo, M.G.; Cigliano, A.; Ribback, S.; Li, X.; Latte, G.; Mela, M.; Evert, M.; et al. Co-activation of AKT and c-Met triggers rapid hepatocellular carcinoma development via the mTORC1/FASN pathway in mice. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 20484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Guo, L. Effects of orexin A on glucose metabolism in human hepatocellular carcinoma in vitro via PI3K/Akt/mTOR-dependent and -independent mechanism. Mol. Cell Endocrinol. 2016, 420, 208–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhang, C.; Zhao, Q.; Wei, W.; Dong, Z.; Shao, L.; Li, J.; Wu, W.; Zhang, H.; Huang, H.; et al. The miR-873/NDFIP1 axis promotes hepatocellular carcinoma growth and metastasis through the AKT/mTOR-mediated Warburg effect. Am. J. Cancer Res. 2019, 9, 927–944. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ye, G.; Qin, Y.; Wang, S.; Pan, D.; Xu, S.; Wu, C.; Wang, X.; Wang, J.; Ye, H.; Shen, H. Lamc1 promotes the Warburg effect in hepatocellular carcinoma cells by regulating PKM2 expression through AKT pathway. Cancer Biol. Ther. 2019, 20, 711–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.S.; Li, L.Y.; Guan, Y.D.; Yang, J.M.; Cheng, Y. Anticancer strategies based on the metabolic profile of tumor cells: Therapeutic targeting of the Warburg effect. Acta Pharmacol. Sin. 2016, 37, 1013–1019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cui, H.; Gao, Q.; Zhang, L.; Han, F.; Wang, L. Knockdown of FOXK1 suppresses liver cancer cell viability by inhibiting glycolysis. Life Sci. 2018, 213, 66–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, G.; Shi, A.; Wang, N.; Li, M.; He, X.; Yin, C.; Tu, Q.; Shen, X.; Tao, Y.; Wang, Q.; et al. Polyphenolic Proanthocyanidin-B2 suppresses proliferation of liver cancer cells and hepatocellular carcinogenesis through directly binding and inhibiting AKT activity. Redox Biol. 2020, 37, 101701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, C.; Yang, D.; Klement, J.D.; Colson, Y.L.; Oberlies, N.H.; Pearce, C.J.; Colby, A.H.; Grinstaff, M.W.; Liu, Z.; Shi, H.; et al. H3K9me3 represses G6PD expression to suppress the pentose phosphate pathway and ROS production to promote human mesothelioma growth. Oncogene 2022, 41, 2651–2662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, X.; Duan, X.; Mao, W.; Li, X.; Li, Z.; Li, Q.; Zheng, Z.; Xu, H.; Chen, M.; Wang, P.G.; et al. O-GlcNAcylation of G6PD promotes the pentose phosphate pathway and tumor growth. Nat. Commun. 2015, 6, 8468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, R.; Elf, S.; Shan, C.; Kang, H.B.; Ji, Q.; Zhou, L.; Hitosugi, T.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, S.; Seo, J.H.; et al. 6-Phosphogluconate dehydrogenase links oxidative PPP, lipogenesis and tumour growth by inhibiting LKB1-AMPK signalling. Nat. Cell Biol. 2015, 17, 1484–1496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitsuishi, Y.; Taguchi, K.; Kawatani, Y.; Shibata, T.; Nukiwa, T.; Aburatani, H.; Yamamoto, M.; Motohashi, H. Nrf2 redirects glucose and glutamine into anabolic pathways in metabolic reprogramming. Cancer Cell 2012, 22, 66–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, H.; Wu, D.; Bao, L.; Yin, T.; Lei, D.; Yu, J.; Tong, X. 6PGD inhibition sensitizes hepatocellular carcinoma to chemotherapy via AMPK activation and metabolic reprogramming. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2019, 111, 1353–1358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, J.; Huang, Y.; Zhang, X.; Yu, Y.; Wu, S.; Jiao, J.; Tran, L.; Zhang, W.; Liu, R.; Zhang, L.; et al. TRIM21 and PHLDA3 negatively regulate the crosstalk between the PI3K/AKT pathway and PPP metabolism. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 1880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhangyuan, G.; Wang, F.; Zhang, H.; Jiang, R.; Tao, X.; Yu, D.; Jin, K.; Yu, W.; Liu, Y.; Yin, Y.; et al. VersicanV1 promotes proliferation and metastasis of hepatocellular carcinoma through the activation of EGFR-PI3K-AKT pathway. Oncogene 2020, 39, 1213–1230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, X.; Zheng, E.; Wei, L.; Zeng, H.; Qin, H.; Zhang, X.; Liao, M.; Chen, L.; Zhao, L.; Ruan, X.Z.; et al. The fatty acid receptor CD36 promotes HCC progression through activating Src/PI3K/AKT axis-dependent aerobic glycolysis. Cell Death Dis. 2021, 12, 328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lundo, K.; Trauelsen, M.; Pedersen, S.F.; Schwartz, T.W. Why Warburg Works: Lactate Controls Immune Evasion through GPR81. Cell Metab. 2020, 31, 666–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Q.; Li, J.; Xing, J.; Li, W.; Li, H.; Ke, X.; Zhang, J.; Ren, T.; Shang, Y.; Yang, H.; et al. CD147 promotes reprogramming of glucose metabolism and cell proliferation in HCC cells by inhibiting the p53-dependent signaling pathway. J. Hepatol. 2014, 61, 859–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.L.; Lucas, J.E.; Schroeder, T.; Mori, S.; Wu, J.; Nevins, J.; Dewhirst, M.; West, M.; Chi, J.T. The genomic analysis of lactic acidosis and acidosis response in human cancers. PLoS Genet 2008, 4, e1000293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alannan, M.; Fayyad-Kazan, H.; Trezeguet, V.; Merched, A. Targeting Lipid Metabolism in Liver Cancer. Biochemistry 2020, 59, 3951–3964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.S.; Lee, Y.M.; Oh, T.I.; Shin, D.H.; Kim, G.H.; Kan, S.Y.; Kang, H.; Kim, J.H.; Kim, B.M.; Yim, W.J.; et al. Emodin Sensitizes Hepatocellular Carcinoma Cells to the Anti-Cancer Effect of Sorafenib through Suppression of Cholesterol Metabolism. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 3127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Q.W.; Yu, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, X.H. VLCAD inhibits the proliferation and invasion of hepatocellular cancer cells through regulating PI3K/AKT axis. Clin. Transl. Oncol. 2022, 24, 864–874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, Y.H.; Ko, Y.C.; Ku, H.J.; Huang, C.C.; Yao, Y.C.; Liao, Y.T.; Chen, Y.T.; Huang, S.F.; Huang, L.R. Novel Paired Cell Lines for the Study of Lipid Metabolism and Cancer Stemness of Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Front Cell Dev. Biol. 2022, 10, 821224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.; Huang, Q.; Long, X.; Zhang, J.; Huang, X.; Aa, J.; Yang, H.; Chen, Z.; Xing, J. CD147 reprograms fatty acid metabolism in hepatocellular carcinoma cells through Akt/mTOR/SREBP1c and P38/PPARalpha pathways. J. Hepatol. 2015, 63, 1378–1389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, J.; Hong, W.; Yao, K.N.; Zhu, X.H.; Chen, Z.Y.; Ye, L. Ursodeoxycholic acid ameliorates hepatic lipid metabolism in LO2 cells by regulating the AKT/mTOR/SREBP-1 signaling pathway. World J. Gastroenterol. 2019, 25, 1492–1501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bort, A.; Sanchez, B.G.; Mateos-Gomez, P.A.; Diaz-Laviada, I.; Rodriguez-Henche, N. Capsaicin Targets Lipogenesis in HepG2 Cells Through AMPK Activation, AKT Inhibition and PPARs Regulation. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 1660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shimano, H.; Sato, R. SREBP-regulated lipid metabolism: Convergent physiology—Divergent pathophysiology. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 2017, 13, 710–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Calvisi, D.F.; Wang, C.; Ho, C.; Ladu, S.; Lee, S.A.; Mattu, S.; Destefanis, G.; Delogu, S.; Zimmermann, A.; Ericsson, J.; et al. Increased lipogenesis, induced by AKT-mTORC1-RPS6 signaling, promotes development of human hepatocellular carcinoma. Gastroenterology 2011, 140, 1071–1083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, F.; Sharen, G.; Yuan, F.; Peng, Y.; Chen, R.; Zhou, X.; Wei, H.; Li, B.; Jing, W.; Zhao, J. TIP30 regulates lipid metabolism in hepatocellular carcinoma by regulating SREBP1 through the Akt/mTOR signaling pathway. Oncogenesis 2017, 6, e347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Pilo, G.M.; Li, X.; Cigliano, A.; Latte, G.; Che, L.; Joseph, C.; Mela, M.; Wang, C.; Jiang, L.; et al. Inactivation of fatty acid synthase impairs hepatocarcinogenesis driven by AKT in mice and humans. J. Hepatol. 2016, 64, 333–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Che, L.; Tharp, K.M.; Park, H.M.; Pilo, M.G.; Cao, D.; Cigliano, A.; Latte, G.; Xu, Z.; Ribback, S.; et al. Differential requirement for de novo lipogenesis in cholangiocarcinoma and hepatocellular carcinoma of mice and humans. Hepatology 2016, 63, 1900–1913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, Z.; Zhang, C.; Zhou, J.; Hu, J.; Sheng, L.; Li, X.; Chen, L.; Li, X.; Deng, X.; Zheng, G. Celecoxib alleviates AKT/c-Met-triggered rapid hepatocarcinogenesis by suppressing a novel COX-2/AKT/FASN cascade. Mol. Carcinog. 2019, 58, 31–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, J.; Chen, J.; Huang, J.; Li, Z.; Gong, Y.; Zou, B.; Liu, X.; Ding, L.; Li, P.; Zhu, Z.; et al. HIF-2alpha upregulation mediated by hypoxia promotes NAFLD-HCC progression by activating lipid synthesis via the PI3K-AKT-mTOR pathway. Aging 2019, 11, 10839–10860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, F.; Antonucci, L.; Yamachika, S.; Zhang, Z.; Taniguchi, K.; Umemura, A.; Hatzivassiliou, G.; Roose-Girma, M.; Reina-Campos, M.; Duran, A.; et al. NRF2 activates growth factor genes and downstream AKT signaling to induce mouse and human hepatomegaly. J. Hepatol. 2020, 72, 1182–1195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altman, B.J.; Stine, Z.E.; Dang, C.V. From Krebs to clinic: Glutamine metabolism to cancer therapy. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2016, 16, 619–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ananieva, E. Targeting amino acid metabolism in cancer growth and anti-tumor immune response. World J. Biol. Chem. 2015, 6, 281–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tennant, D.A.; Duran, R.V.; Gottlieb, E. Targeting metabolic transformation for cancer therapy. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2010, 10, 267–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jewell, J.L.; Kim, Y.C.; Russell, R.C.; Yu, F.X.; Park, H.W.; Plouffe, S.W.; Tagliabracci, V.S.; Guan, K.L. Metabolism. Differential regulation of mTORC1 by leucine and glutamine. Science 2015, 347, 194–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, H.; Wang, S.; Zaal, E.A.; Wang, C.; Wu, H.; Bosma, A.; Jochems, F.; Isima, N.; Jin, G.; Lieftink, C.; et al. A powerful drug combination strategy targeting glutamine addiction for the treatment of human liver cancer. Elife 2020, 9, 56749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xi, J.; Sun, Y.; Zhang, M.; Fa, Z.; Wan, Y.; Min, Z.; Xu, H.; Xu, C.; Tang, J. GLS1 promotes proliferation in hepatocellular carcinoma cells via AKT/GSK3beta/CyclinD1 pathway. Exp. Cell Res. 2019, 381, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Y.; Tang, X.; Ren, Y.; Yang, Y.; Song, F.; Fu, J.; Liu, S.; Yu, M.; Chen, J.; Wang, S.; et al. An RNA-RNA crosstalk network involving HMGB1 and RICTOR facilitates hepatocellular carcinoma tumorigenesis by promoting glutamine metabolism and impedes immunotherapy by PD-L1+ exosomes activity. Signal. Transduct. Target Ther. 2021, 6, 421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, M.; Bu, X.; Li, Z.; Xu, H.; Feng, L.; Hu, J.; Wei, X.; Gao, J.; Tao, Y.; Cai, B.; et al. NDRG2 ablation reprograms metastatic cancer cells towards glutamine dependence via the induction of ASCT2. Int. J. Biol. Sci. 2020, 16, 3100–3115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feun, L.; You, M.; Wu, C.J.; Kuo, M.T.; Wangpaichitr, M.; Spector, S.; Savaraj, N. Arginine deprivation as a targeted therapy for cancer. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2008, 14, 1049–1057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saha, A.; Connelly, S.; Jiang, J.; Zhuang, S.; Amador, D.T.; Phan, T.; Pilz, R.B.; Boss, G.R. Akt phosphorylation and regulation of transketolase is a nodal point for amino acid control of purine synthesis. Mol. Cell 2014, 55, 264–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, C.; Raffaghello, L.; Brandhorst, S.; Safdie, F.M.; Bianchi, G.; Martin-Montalvo, A.; Pistoia, V.; Wei, M.; Hwang, S.; Merlino, A.; et al. Fasting cycles retard growth of tumors and sensitize a range of cancer cell types to chemotherapy. Sci. Transl. Med. 2012, 4, 124–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cox, A.G.; Hwang, K.L.; Brown, K.K.; Evason, K.; Beltz, S.; Tsomides, A.; O’Connor, K.; Galli, G.G.; Yimlamai, D.; Chhangawala, S.; et al. Yap reprograms glutamine metabolism to increase nucleotide biosynthesis and enable liver growth. Nat. Cell Biol. 2016, 18, 886–896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimri, M.; Humphries, A.; Laknaur, A.; Elattar, S.; Lee, T.J.; Sharma, A.; Kolhe, R.; Satyanarayana, A. NAD(P)H Quinone Dehydrogenase 1 Ablation Inhibits Activation of the Phosphoinositide 3-Kinase/Akt Serine/Threonine Kinase and Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinase/Extracellular Signal-Regulated Kinase Pathways and Blocks Metabolic Adaptation in Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Hepatology 2020, 71, 549–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bidkhori, G.; Benfeitas, R.; Klevstig, M.; Zhang, C.; Nielsen, J.; Uhlen, M.; Boren, J.; Mardinoglu, A. Metabolic network-based stratification of hepatocellular carcinoma reveals three distinct tumor subtypes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2018, 115, E11874–E11883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben-Sahra, I.; Howell, J.J.; Asara, J.M.; Manning, B.D. Stimulation of de novo pyrimidine synthesis by growth signaling through mTOR and S6K1. Science 2013, 339, 1323–1328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siddiqui, A.; Ceppi, P. A non-proliferative role of pyrimidine metabolism in cancer. Mol. Metab. 2020, 35, 100962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Yang, K.; Wu, Q.; Kim, L.J.Y.; Morton, A.R.; Gimple, R.C.; Prager, B.C.; Shi, Y.; Zhou, W.; Bhargava, S.; et al. Targeting pyrimidine synthesis accentuates molecular therapy response in glioblastoma stem cells. Sci. Transl. Med. 2019, 11, 4972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ridder, D.A.; Schindeldecker, M.; Weinmann, A.; Berndt, K.; Urbansky, L.; Witzel, H.R.; Heinrich, S.; Roth, W.; Straub, B.K. Key Enzymes in Pyrimidine Synthesis, CAD and CPS1, Predict Prognosis in Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Cancers 2021, 13, 744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Z.; Cao, C.; Zhang, D.; Zhang, Z.; Liu, L.; Wu, D.; Sun, J. UBE2T-mediated Akt ubiquitination and Akt/beta-catenin activation promotes hepatocellular carcinoma development by increasing pyrimidine metabolism. Cell Death Dis. 2022, 13, 154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chong, Y.C.; Toh, T.B.; Chan, Z.; Lin, Q.X.X.; Thng, D.K.H.; Hooi, L.; Ding, Z.; Shuen, T.; Toh, H.C.; Dan, Y.Y.; et al. Targeted Inhibition of Purine Metabolism Is Effective in Suppressing Hepatocellular Carcinoma Progression. Hepatol. Commun. 2020, 4, 1362–1381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fu, Y.; Liu, S.; Rodrigues, R.M.; Han, Y.; Guo, C.; Zhu, Z.; He, Y.; Mackowiak, B.; Feng, D.; Gao, B.; et al. Activation of VIPR1 suppresses hepatocellular carcinoma progression by regulating arginine and pyrimidine metabolism. Int. J. Biol. Sci. 2022, 18, 4341–4356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Cui, J.; Ma, H.; Lu, W.; Huang, J. Targeting Pyrimidine Metabolism in the Era of Precision Cancer Medicine. Front Oncol. 2021, 11, 684961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kong, N.; Zhang, H.; Feng, C.; Liu, C.; Xiao, Y.; Zhang, X.; Mei, L.; Kim, J.S.; Tao, W.; Ji, X. Arsenene-mediated multiple independently targeted reactive oxygen species burst for cancer therapy. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 4777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lim, S.O.; Gu, J.M.; Kim, M.S.; Kim, H.S.; Park, Y.N.; Park, C.K.; Cho, J.W.; Park, Y.M.; Jung, G. Epigenetic changes induced by reactive oxygen species in hepatocellular carcinoma: Methylation of the E-cadherin promoter. Gastroenterology 2008, 135, 2128–2140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nogueira, V.; Park, Y.; Chen, C.C.; Xu, P.Z.; Chen, M.L.; Tonic, I.; Unterman, T.; Hay, N. Akt determines replicative senescence and oxidative or oncogenic premature senescence and sensitizes cells to oxidative apoptosis. Cancer Cell 2008, 14, 458–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silva, A.; Girio, A.; Cebola, I.; Santos, C.I.; Antunes, F.; Barata, J.T. Intracellular reactive oxygen species are essential for PI3K/Akt/mTOR-dependent IL-7-mediated viability of T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia cells. Leukemia 2011, 25, 960–967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Z.; Gao, J.; Li, C.; Xu, X.; Hu, Y.; Huang, S. Reactive Oxygen Species Induce Endothelial Differentiation of Liver Cancer Stem-Like Sphere Cells through the Activation of Akt/IKK Signaling Pathway. Oxid. Med. Cell Longev. 2020, 2020, 1621687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orci, L.A.; Lacotte, S.; Delaune, V.; Slits, F.; Oldani, G.; Lazarevic, V.; Rossetti, C.; Rubbia-Brandt, L.; Morel, P.; Toso, C. Effects of the gut-liver axis on ischaemia-mediated hepatocellular carcinoma recurrence in the mouse liver. J. Hepatol. 2018, 68, 978–985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ng, K.T.; Yeung, O.W.; Lam, Y.F.; Liu, J.; Liu, H.; Pang, L.; Yang, X.X.; Zhu, J.; Zhang, W.; Lau, M.Y.H.; et al. Glutathione S-transferase A2 promotes hepatocellular carcinoma recurrence after liver transplantation through modulating reactive oxygen species metabolism. Cell Death Discov. 2021, 7, 188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wan, J.; Liu, T.; Mei, L.; Li, J.; Gong, K.; Yu, C.; Li, W. Synergistic antitumour activity of sorafenib in combination with tetrandrine is mediated by reactive oxygen species (ROS)/Akt signaling. Br. J. Cancer 2013, 109, 342–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, G.; He, J.; Ye, X.; Zhu, J.; Hu, X.; Shen, M.; Ma, Y.; Mao, Z.; Song, H.; Chen, F. beta-Thujaplicin induces autophagic cell death, apoptosis, and cell cycle arrest through ROS-mediated Akt and p38/ERK MAPK signaling in human hepatocellular carcinoma. Cell Death Dis. 2019, 10, 255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Gong, K.; Mao, X.; Li, W. Tetrandrine induces apoptosis by activating reactive oxygen species and repressing Akt activity in human hepatocellular carcinoma. Int. J. Cancer 2011, 129, 1519–1531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farazi, P.A.; DePinho, R.A. Hepatocellular carcinoma pathogenesis: From genes to environment. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2006, 6, 674–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, C.; Liu, M.; Ge, Y.; Qian, Y.; Fan, H. HBx increases chromatin accessibility and ETV4 expression to regulate dishevelled-2 and promote HCC progression. Cell Death Dis. 2022, 13, 116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ha, H.L.; Yu, D.Y. HBx-induced reactive oxygen species activates hepatocellular carcinogenesis via dysregulation of PTEN/Akt pathway. World J. Gastroenterol. 2010, 16, 4932–4937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ko, E.; Seo, H.W.; Jung, G. Telomere length and reactive oxygen species levels are positively associated with a high risk of mortality and recurrence in hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology 2018, 67, 1378–1391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, T.; Wang, J.; Zhang, H.; Yuan, P.; Zhu, J.; Wu, Y.; Huang, Q.; Guo, X.; Zhang, J.; Ji, L.; et al. MCUR1-Mediated Mitochondrial Calcium Signaling Facilitates Cell Survival of Hepatocellular Carcinoma via Reactive Oxygen Species-Dependent P53 Degradation. Antioxid. Redox. Signal. 2018, 28, 1120–1136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.R.; You, R.I.; Hu, C.T.; Cheng, C.C.; Rudy, R.; Wu, W.S. Hydrogen peroxide inducible clone-5 sustains NADPH oxidase-dependent reactive oxygen species-c-jun N-terminal kinase signaling in hepatocellular carcinoma. Oncogenesis 2019, 8, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Q.; Zhou, L.; Lv, D.; Zhu, X.; Tang, H. Exosome-mediated communication in the tumor microenvironment contributes to hepatocellular carcinoma development and progression. J. Hematol. Oncol. 2019, 12, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, J.; Zheng, B.; Goswami, S.; Meng, L.; Zhang, D.; Cao, C.; Li, T.; Zhu, F.; Ma, L.; Zhang, Z.; et al. PD1(Hi) CD8(+) T cells correlate with exhausted signature and poor clinical outcome in hepatocellular carcinoma. J. Immunother. Cancer 2019, 7, 331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez-Reyes, I.; Chandel, N.S. Cancer metabolism: Looking forward. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2021, 21, 669–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, C.H.; Qiu, J.; O’Sullivan, D.; Buck, M.D.; Noguchi, T.; Curtis, J.D.; Chen, Q.; Gindin, M.; Gubin, M.M.; van der Windt, G.J.; et al. Metabolic Competition in the Tumor Microenvironment Is a Driver of Cancer Progression. Cell 2015, 162, 1229–1241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vitale, I.; Manic, G.; Coussens, L.M.; Kroemer, G.; Galluzzi, L. Macrophages and Metabolism in the Tumor Microenvironment. Cell Metab. 2019, 30, 36–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colegio, O.R.; Chu, N.Q.; Szabo, A.L.; Chu, T.; Rhebergen, A.M.; Jairam, V.; Cyrus, N.; Brokowski, C.E.; Eisenbarth, S.C.; Phillips, G.M.; et al. Functional polarization of tumour-associated macrophages by tumour-derived lactic acid. Nature 2014, 513, 559–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vergadi, E.; Ieronymaki, E.; Lyroni, K.; Vaporidi, K.; Tsatsanis, C. Akt Signaling Pathway in Macrophage Activation and M1/M2 Polarization. J. Immunol. 2017, 198, 1006–1014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, H.C.; Xin-Yan, Y.; Yu, W.W.; Liang, X.Q.; Du, X.Y.; Liu, Z.C.; Long, J.P.; Zhao, G.H.; Liu, H.B. Lactic acid in macrophage polarization: The significant role in inflammation and cancer. Int. Rev. Immunol. 2022, 41, 4–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Lou, Y.; Bai, X.L.; Liang, T.B. Immunometabolism: A novel perspective of liver cancer microenvironment and its influence on tumor progression. World J. Gastroenterol. 2018, 24, 3500–3512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finlay, D.; Cantrell, D.A. Metabolism, migration and memory in cytotoxic T cells. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2011, 11, 109–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macintyre, A.N.; Finlay, D.; Preston, G.; Sinclair, L.V.; Waugh, C.M.; Tamas, P.; Feijoo, C.; Okkenhaug, K.; Cantrell, D.A. Protein kinase B controls transcriptional programs that direct cytotoxic T cell fate but is dispensable for T cell metabolism. Immunity 2011, 34, 224–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crompton, J.G.; Sukumar, M.; Roychoudhuri, R.; Clever, D.; Gros, A.; Eil, R.L.; Tran, E.; Hanada, K.; Yu, Z.; Palmer, D.C.; et al. Akt inhibition enhances expansion of potent tumor-specific lymphocytes with memory cell characteristics. Cancer Res. 2015, 75, 296–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basu, S.; Hubbard, B.; Shevach, E.M. Foxp3-mediated inhibition of Akt inhibits Glut1 (glucose transporter 1) expression in human T regulatory cells. J. Leukoc. Biol. 2015, 97, 279–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, P.; Li, Q.J.; Feng, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Markowitz, G.J.; Ning, S.; Deng, Y.; Zhao, J.; Jiang, S.; Yuan, Y.; et al. TGF-beta-miR-34a-CCL22 signaling-induced Treg cell recruitment promotes venous metastases of HBV-positive hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer Cell 2012, 22, 291–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Francisco, L.M.; Salinas, V.H.; Brown, K.E.; Vanguri, V.K.; Freeman, G.J.; Kuchroo, V.K.; Sharpe, A.H. PD-L1 regulates the development, maintenance, and function of induced regulatory T cells. J. Exp. Med. 2009, 206, 3015–3029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xia, Y.; Brown, Z.J.; Huang, H.; Tsung, A. Metabolic reprogramming of immune cells: Shaping the tumor microenvironment in hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer Med. 2021, 10, 6374–6383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chou, W.C.; Rampanelli, E.; Li, X.; Ting, J.P. Impact of intracellular innate immune receptors on immunometabolism. Cell Mol. Immunol. 2022, 19, 337–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myers, J.A.; Miller, J.S. Exploring the NK cell platform for cancer immunotherapy. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 2021, 18, 85–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loftus, R.M.; Assmann, N.; Kedia-Mehta, N.; O’Brien, K.L.; Garcia, A.; Gillespie, C.; Hukelmann, J.L.; Oefner, P.J.; Lamond, A.I.; Gardiner, C.M.; et al. Amino acid-dependent cMyc expression is essential for NK cell metabolic and functional responses in mice. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 2341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, A.K.; Nandagopal, N.; Lee, S.H. IL-15-PI3K-AKT-mTOR: A Critical Pathway in the Life Journey of Natural Killer Cells. Front Immunol. 2015, 6, 355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Cheng, Y.; Xu, Y.; Wang, Z.; Du, X.; Li, C.; Peng, J.; Gao, L.; Liang, X.; Ma, C. Increased expression of programmed cell death protein 1 on NK cells inhibits NK-cell-mediated anti-tumor function and indicates poor prognosis in digestive cancers. Oncogene 2017, 36, 6143–6153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zecca, A.; Barili, V.; Canetti, D.; Regina, V.; Olivani, A.; Carone, C.; Capizzuto, V.; Zerbato, B.; Trenti, T.; Dalla Valle, R.; et al. Energy metabolism and cell motility defect in NK-cells from patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer Immunol. Immunother 2020, 69, 1589–1603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terren, I.; Orrantia, A.; Vitalle, J.; Zenarruzabeitia, O.; Borrego, F. NK Cell Metabolism and Tumor Microenvironment. Front Immunol. 2019, 10, 2278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Speiser, D.E.; Ho, P.C.; Verdeil, G. Regulatory circuits of T cell function in cancer. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2016, 16, 599–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Facciorusso, A.; Abd El Aziz, M.A.; Sacco, R. Efficacy of Regorafenib in Hepatocellular Carcinoma Patients: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Cancers 2019, 12, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villanueva, A.; Chiang, D.Y.; Newell, P.; Peix, J.; Thung, S.; Alsinet, C.; Tovar, V.; Roayaie, S.; Minguez, B.; Sole, M.; et al. Pivotal role of mTOR signaling in hepatocellular carcinoma. Gastroenterology 2008, 135, 1972–1983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vander Heiden, M.G.; Cantley, L.C.; Thompson, C.B. Understanding the Warburg effect: The metabolic requirements of cell proliferation. Science 2009, 324, 1029–1033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, L.; Mayerle, J.; Ziesch, A.; Reiter, F.P.; Gerbes, A.L.; De Toni, E.N. The PI3K inhibitor copanlisib synergizes with sorafenib to induce cell death in hepatocellular carcinoma. Cell Death Discov. 2019, 5, 86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damodaran, S.; Zhao, F.; Deming, D.A.; Mitchell, E.P.; Wright, J.J.; Gray, R.J.; Wang, V.; McShane, L.M.; Rubinstein, L.V.; Patton, D.R.; et al. Phase II Study of Copanlisib in Patients With Tumors With PIK3CA Mutations: Results From the NCI-MATCH ECOG-ACRIN Trial (EAY131) Subprotocol Z1F. J. Clin. Oncol. 2022, 40, 1552–1561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patra, T.; Meyer, K.; Ray, R.B.; Ray, R. A combination of AZD5363 and FH5363 induces lethal autophagy in transformed hepatocytes. Cell Death Dis. 2020, 11, 540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Z.; Wulfkuhle, J.; Nowicka, M.; Gallagher, R.I.; Saura, C.; Nuciforo, P.G.; Calvo, I.; Andersen, J.; Passos-Coelho, J.L.; Gil-Gil, M.J.; et al. Functional Mapping of AKT Signaling and Biomarkers of Response from the FAIRLANE Trial of Neoadjuvant Ipatasertib plus Paclitaxel for Triple-Negative Breast Cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 2022, 28, 993–1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, X.; Huang, S.; Yang, Y.; Lu, Z.; Li, F.; Jiang, L.; Jiang, Y.; Liu, J. Sirolimus or Everolimus Improves Survival After Liver Transplantation for Hepatocellular Carcinoma: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Liver Transpl. 2022, 28, 1063–1077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Z.; Wang, J.; Liu, M.; Chen, D.; Qiu, C.; Sun, K. CC-223 blocks mTORC1/C2 activation and inhibits human hepatocellular carcinoma cells in vitro and in vivo. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0173252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Y.D.; Fang, L.; Yu, H.Q.; Zhang, J.; Lin, X.T.; Liu, X.Y.; Wu, D.; Li, G.X.; Huang, D.; Zhang, Y.J.; et al. p53 haploinsufficiency and increased mTOR signalling define a subset of aggressive hepatocellular carcinoma. J. Hepatol. 2021, 74, 96–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, Y.; Wang, Y.; Zhou, C.; Mei, W.; Zeng, C. PI3K/Akt/mTOR Pathway and Its Role in Cancer Therapeutics: Are We Making Headway? Front Oncol. 2022, 12, 819128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rationalizing combination therapies. Nat. Med. 2017, 23, 1113. [CrossRef]

- Grabinski, N.; Ewald, F.; Hofmann, B.T.; Staufer, K.; Schumacher, U.; Nashan, B.; Jucker, M. Combined targeting of AKT and mTOR synergistically inhibits proliferation of hepatocellular carcinoma cells. Mol. Cancer 2012, 11, 85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asghar, U.; Meyer, T. Are there opportunities for chemotherapy in the treatment of hepatocellular cancer? J. Hepatol. 2012, 56, 686–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Y.Q.; Gu, S.X.; Chen, Y.S.; Gao, X.D.; Ren, Y.X.; Chen, J.C.; Lu, Y.Y.; Zhang, H.; Cao, S. Virtual Screening and Optimization of Novel mTOR Inhibitors for Radiosensitization of Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Drug Des. Devel. Ther. 2020, 14, 1779–1798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrin, G.; Guerrero, M.; Amado, V.; Rodriguez-Peralvarez, M.; De la Mata, M. Activation of mTOR Signaling Pathway in Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 1266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popova, N.V.; Jucker, M. The Role of mTOR Signaling as a Therapeutic Target in Cancer. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 1743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Gene/Protein/Molecule | Role in HCC | References |

|---|---|---|

| 4EBP1 | Repression of the initiation of protein translation | [45] |

| 6PGD | Key enzyme of the PPP, promoting liver cell growth, | [50,52] |

| ACC | facilitates the fatty acid synthesis | [63] |

| AMPK | Regulates growth of HCC CSCs, regulates both immune and nonimmune cell metabolism | [27,128] |

| ASNS | Asparagine synthetase | [87] |

| CAD | Pyrimidine metabolism | [92,95] |

| COX-2 | Lipogenesis | [71] |

| DHODH | Pyrimidine metabolism | [92] |

| EGFR | Increases proliferation, invasion, and metastasis | [54] |

| FASN | facilitates fatty acid synthesis | [63] |

| GDH | Glutamate dehydrogenase | [80] |

| GLS1 | Promotes proliferation | [79] |

| GLUT1 | Glucose metabolism | [44,45] |

| GS | Glutamine synthetase | [80] |

| HBx | Regulatory protein in HCC progression, induces ROS | [107,108] |

| HK2 | Glycolysis | [46] |

| IL-6 | HCC development | [38] |

| Lamc1 | Decreases growth of HCC cells | [44] |

| MCUR1 | Regulation of HCC cell survival | [110] |

| NDFIP1 | Initiates metabolic change causing HCC formation and metastasis | [43] |

| NDRG2 | Glutaminolysis | [81] |

| Nqo1 | Glutaminolysis | [86] |

| NRF2 | Triggers transcription of growth factor genes | [73] |

| PD-L1 | Glycolysis rate of T-infiltrating cells | [127] |

| PHLDA3 | Metabolic reprogramming | [53] |

| ROS | DNA damage and the differentiation grade | [97] |

| SREBP1 | Hepatic cellular lipid metabolism | [64,65,66,67,68] |

| SREBP2 | Hepatic cellular lipid metabolism | [64,65,66,67,68] |

| SREBPs | Hepatic cellular lipid metabolism | [64,65,66,67,68] |

| STAT3 | Facilitates HCC development | [38] |

| TIRM21 | Metabolic reprogramming | [53] |

| UBE2T | Pyrimidine metabolism | [92] |

| UMPS | Pyrimidine metabolism | [92] |

| VEGFA | Angiogenesis | [24] |

| VIPR1 | Pyrimidine biosynthesis | [94] |

| Inhibitor | Target | Phase | ClinicalTrials.Gov Identifier |

|---|---|---|---|

| Copanlisib | PI3K | 2 | NCT02465060 Start date: August 2015 Completion date: December 2025 |

| Capivasertib | AKT | 2 | NCT02465060 Start date: August 2015 Completion date: December 2025 |

| Ipatasertib | AKT | 2 | NCT02465060 Start date: August 2015 Completion date: December 2025 |

| Everolimus | mTOR | 4 | NCT02081755 Start date: March 2014 Completion date: January 2023 |

| mTOR | 2 | NCT04803318 Start date: January 2021 Completion date: January 2023 | |

| CC-223 | mTOR | 2 | NCT03591965 Start date: August 2018 Completion date: December 2022 |

| Sapanisertib | mTOR | 2 | NCT02465060 Start date: August 2015 Completion date: December 2025 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Tian, L.-Y.; Smit, D.J.; Jücker, M. The Role of PI3K/AKT/mTOR Signaling in Hepatocellular Carcinoma Metabolism. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 2652. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms24032652

Tian L-Y, Smit DJ, Jücker M. The Role of PI3K/AKT/mTOR Signaling in Hepatocellular Carcinoma Metabolism. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2023; 24(3):2652. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms24032652

Chicago/Turabian StyleTian, Ling-Yu, Daniel J. Smit, and Manfred Jücker. 2023. "The Role of PI3K/AKT/mTOR Signaling in Hepatocellular Carcinoma Metabolism" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 24, no. 3: 2652. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms24032652

APA StyleTian, L.-Y., Smit, D. J., & Jücker, M. (2023). The Role of PI3K/AKT/mTOR Signaling in Hepatocellular Carcinoma Metabolism. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 24(3), 2652. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms24032652