Abstract

Sepsis is a life-threatening condition caused by the body’s overwhelming response to an infection, such as pneumonia or urinary tract infection. It occurs when the immune system releases cytokines into the bloodstream, triggering widespread inflammation. If not treated, it can lead to organ failure and death. Unfortunately, sepsis has a high mortality rate, with studies reporting rates ranging from 20% to over 50%, depending on the severity and promptness of treatment. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), the annual death toll in the world is about 11 million. One of the main toxins responsible for inflammation induction are lipopolysaccharides (LPS, endotoxin) from Gram-negative bacteria, which rank among the most potent immunostimulants found in nature. Antibiotics are consistently prescribed as a part of anti-sepsis-therapy. However, antibiotic therapy (i) is increasingly ineffective due to resistance development and (ii) most antibiotics are unable to bind and neutralize LPS, a prerequisite to inhibit the interaction of endotoxin with its cellular receptor complex, namely Toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4)/MD-2, responsible for the intracellular cascade leading to pro-inflammatory cytokine secretion. The pandemic virus SARS-CoV-2 has infected hundreds of millions of humans worldwide since its emergence in 2019. The COVID-19 (Coronavirus disease-19) caused by this virus is associated with high lethality, particularly for elderly and immunocompromised people. As of August 2023, nearly 7 million deaths were reported worldwide due to this disease. According to some reported studies, upregulation of TLR4 and the subsequent inflammatory signaling detected in COVID-19 patients “mimics bacterial sepsis”. Furthermore, the immune response to SARS-CoV-2 was described by others as “mirror image of sepsis”. Similarly, the cytokine profile in sera from severe COVID-19 patients was very similar to those suffering from the acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) and sepsis. Finally, the severe COVID-19 infection is frequently accompanied by bacterial co-infections, as well as by the presence of significant LPS concentrations. In the present review, we will analyze similarities and differences between COVID-19 and sepsis at the pathophysiological, epidemiological, and molecular levels.

1. Risk Factors and Complications of COVID-19

The Coronavirus disease of 2019 (COVID-19) due to the coronavirus SARS-CoV-2, is a pandemic with a high rate of mortality [1,2]. The first cases were reported at the end of 2019 in Wuhan, China, and were diagnosed with severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) leading to a potentially life-threatening disease. The symptoms of this pathological condition are fever, shortness of breath, cough, and sudden onset of anosmia (“smell blindness”), ageusia (loss of the sense of taste), or dysgeusia (disorder of the sense of taste). In most cases, approximately 80%, COVID-19 is mild or moderate, but it can evolve into severe or critical clinical presentations with a significant risk of mortality in about 14% and 5% of the cases, respectively [3].

The causative agent of COVID-19, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-2 (SARS-CoV-2), is an enveloped positive single-stranded RNA virus, with a genome 8.4–12 kDa in size. The 5′ terminal part of this genome, which is rich in open reading frames, encodes proteins essential for virus replication. On the other hand, the 3′ terminal includes five structural proteins, spike protein (S), responsible for the pathogenesis in the human species; the membrane protein (M); nucleocapsid protein (N); envelope protein (E); and hemagglutinin-esterase protein (HE) [4].

Numerous studies have analyzed which comorbidities are more commonly associated with COVID-19 severity [5,6,7,8,9]. Interestingly, all these meta-analyses consistently showed that patients suffering from diabetes, hypertension, cancer, and cardiovascular diseases were at higher risk of developing severe COVID-19. Association between other comorbidities and disease burden was also strong, although their relative contribution to disease severity varied among the distinct meta-analyses (Table 1).

Table 1.

Comorbidities of COVID-19 associated with disease severity. Data from non-redundant studies analyzed in references [5,6,7,8,9].

However, to date, the decisive pathophysiologic processes that are responsible for COVID-19 patient morbidity and mortality remain unclear. Chen et al. reported that acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), respiratory failure, multiple organ dysfunction syndrome (MODS) and septic shock were complications strongly associated with critical cases of coronavirus disease [5]. This meta-analysis was particularly relevant as it examined data from 187 studies describing 77,013 patients [5]. Other studies reached the same conclusions [10,11,12]. Importantly, severe cases of non-COVID-19 sepsis caused by respiratory pathogens lead to complications similar to those described by these authors, thereby suggesting that COVID-19 mortality may be the result of sepsis. To address this hypothesis, Ahlström et al. compared the impact of comorbidities on mortality in patients with COVID-19 and sepsis [8]. These authors reported that mortality was significantly reduced in the COVID-19 patients compared with those with sepsis, whereas the use of invasive mechanical ventilation was more common in COVID-19 than in sepsis patients. However, the key conclusion of this study is that almost all the investigated comorbidities were shared between COVID-19 and sepsis patients. Consistent with this finding, sepsis scores have been consistently shown to predict COVID-19 outcomes including death, ICU (intensive care unit) transfer, and respiratory failure [13,14]. For example, 78% of severely ill COVID-19 patients met the Sepsis 3.0 criteria for sepsis/septic shock with ARDS being the most common organ dysfunction at 88% [15].

3. Bacterial Coinfections and the Relationship between LPS and SARS-CoV-2

Bacterial coinfections with SARS-CoV-2 seem to be as prevalent as they once were with influenza virus from serotype H1N1, the etiological agent that caused the 1918 influenza pandemic, and they are believed to have played a significant role in the lethality of both diseases [53].

Bacterial coinfections or secondary bacterial infections are indeed critical risk factors for the severity and mortality rates of COVID-19 [54]. In addition, there is evidence supporting that most of the deaths during the 1918 influenza pandemic were due to the bacterial coinfections rather than the flu virus. In accordance with this hypothesis, serotype H1N1 influenza virus continues to have widespread prevalence worldwide without the devastating consequences of the 1918 pandemic. Nevertheless, there are many important differences between COVID-19 and the 1918 influenza pandemic. For instance, whereas the latter mainly affected young and fully immune-competent people, morbi-mortality due to COVID-19 was strongly associated with aging [55], comorbidities (see above), and immune deficiencies [56].

On the other hand, the cell mediators induced in the case of Gram-negative (lipopolysaccharide, LPS) [57], Gram-positive (lipoproteins or peptides) [58], and SARS-CoV-2 infections (see above, [57,59]) are remarkably similar. In this regard, it is worth noting that the most potent pathogen associated molecular patterns (PAMPs) from Gram-negative bacteria and SARS-CoV-2 induce inflammation through the same cell receptor, namely Toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4)/myeloid differentiation factor 2 (MD-2). Importantly, TLR4 is responsible for the intracellular cascade leading to pro-inflammatory cytokine secretion and its canonical agonist is LPS (endotoxin). Bacterial endotoxin ranks among the most potent immunostimulants found in nature and is the main triggering factor of Gram-negative sepsis, which affects millions of people worldwide [60].

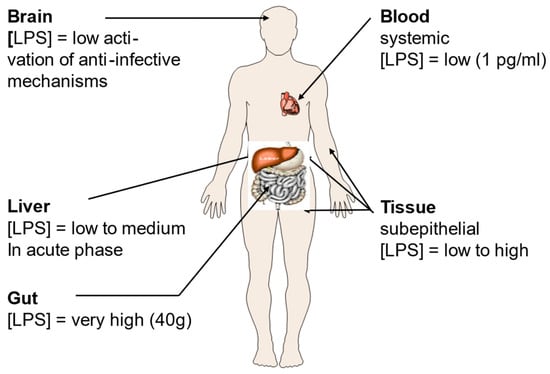

In addition to well-known or presumed disorders triggered by bacteria such as colitis and Crohn’s disease, a variety of additional pathologies are due to the interaction of LPS with the immune system [61]. Such interactions can be the consequence of infections with Gram-negative bacteria, and/or be due to contact with commensal bacteria (Figure 1). The main concentration of this molecule is found in the gut that can contain up to 1.0 to 1.5 kg of bacteria [62]. However, there might also be significant concentrations in subepithelial tissues and in the liver [63].

Figure 1.

Lipopolysaccharide (LPS) concentrations in the human body. LPS is the main constituent of the outer leaflet of the outer membrane of Gram-negative bacteria, and it may induce inflammation even in the nanomolar range [64]. Its presence in the body is tightly associated with locations where bacteria are particularly abundant such as the gut, and the subepithelial tissue. Figure kindly provided by Robert Munford, Oxon, WA, USA.

Since mucosal barrier alterations may play a role in the development of several diseases, including COVID-19, Teixeira et al. (2021) examined the connection between bacterial translocation and systemic inflammation markers at the beginning of hospitalization (T1), and during the last 72 h (T2) in surviving and non-surviving COVID-19 patients. Blood samples were collected from 66 SARS-CoV-2 RT-PCR-positive patients and 9 non-COVID-19 pneumonia controls and the levels of systemic cytokines and chemokines, LPS concentrations, and soluble CD14 (sCD14) were analyzed by incubating the human THP-1 monocytic cell line with plasma from survivors and non-survivors. Their phenotype, activation status, TLR4, and chemokine receptors were analyzed by flow cytometry and confirmed that severe COVID-19 patients have increased LPS levels and systemic inflammation that result in monocyte activation [65].

Several animal models were developed to study COVID-19 infection and potential therapies. Since mouse ACE2 does not effectively bind the viral S protein, transgenic mouse models expressing human ACE2 were used [66]. These mice were susceptible to SARS-CoV-2 infection, but they differed in disease severity. More recently, new animal models have been created to faithfully replicate various aspects of COVID-19 in humans, with a specific focus on pulmonary vascular disease and ARDS [67]. For instance, a mouse inflammation model based on the coadministration of aerosolized SARS-CoV-2 S protein together with LPS to the lungs has been developed [68]. Using nuclear factor-kappa B (NF-κB) luciferase reporter and C57BL/6 mice followed by combinations of bioimaging, cytokine, chemokine, FACS, and histochemistry analyses, the model showed severe pulmonary inflammation and a cytokine profile similar to that observed in COVID-19. This animal model revealed a previously unknown high-affinity interaction between the SARS-CoV-2 S protein and LPS from E. coli and P. aeruginosa, leading to a hyperinflammation in vitro as well as in vivo [68]. Very importantly, the molecular mechanism underlying this effect was dependent on specific and distinct interactions between the S protein and LPS, enabling LPS’s transfer to CD14 and subsequent downstream NF-κB activation. The resulting synergism between the S protein and LPS has clinical relevance, providing new insights into comorbidities that may increase the risk for ARDS during COVID-19. In addition, microscale thermophoresis assays have yielded a KD of 47 nM for the interaction between LPS and SARS-CoV-2 S protein, slightly higher than the interaction between LPS and CD14 (45 nM). Computational modeling and all-atom molecular dynamics simulations further substantiated the experimental results, identifying a main LPS-binding site in SARS-CoV-2 S protein. S protein, when combined with low levels of LPS, boosted (NF-kB) activation in monocytic THP-1 cells and cytokine responses in human blood and peripheral blood mononuclear cells, respectively [63].

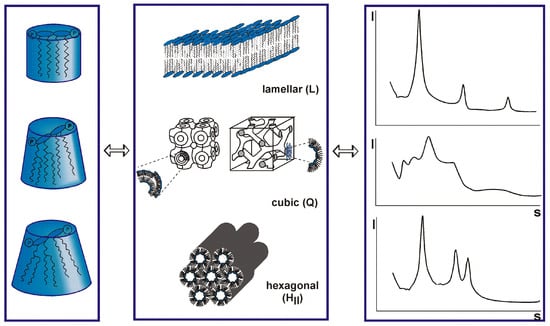

The data of the interaction of the S protein with LPS should be discussed in light of immune stimulation induced by LPS. There are various scenarios possible, and one hypothesis is that LPS is transferred to CD14 which then induces cell activation via the interaction of LPS with the complex of TLR4 and MD-2 [69]. A role of the LPS-binding protein LBP is also envisioned, although cell activation may also take place in the absence of LBP [70]. In any case, today it is assumed that for cell stimulation, the aggregate structure of LPS is decisive [71]. It has been shown that LPS monomers are biologically inactive [72]. LPS molecules naturally form aggregates that can lead to high activity when they are in a non-lamellar geometry, and display no activity in a lamellar form [73]. The different possible aggregate structures for LPS depend on the chemical structures of the monomers (Figure 2). In standard LPS, the lipid A part, the endotoxin principle, has a hexa-acylated diglucosamine backbone which is highly active. Other LPS that are under-acylated, for example with a tetra- or a penta-acylated lipid A, lack bioactivity [74,75,76]. In an analogy to this behavior, biologically active LPS converts, when it is inactivated by the addition of, for example, antimicrobial peptides such as compound Pep19-2.5 or polymyxin B, into a (multi)lamellar and thus, inactive aggregate [77,78].

Figure 2.

Varying conformations of lipopolysaccharide (LPS) monomer (left column) aggregates in different structures (middle panel). These different structures produce distinct small-angle X-ray patterns (right panel) and result from different degrees of acylation of the lipid A molecule (left panel). The acylation varies between tetra, (inactive, but antagonistic), penta (mostly inactive), hexa (normal form, highly active), and even hepta (similarly active as hexa). Unpublished results by K. Brandenburg et al. according to the theory of Israelachvili [73,74].

From the foregoing, it is apparent that the binding of the S protein to LPS changes the conformation of the latter in a way that increases its stimulation potency. Therefore, an analysis of the S protein:LPS complex would give more insight for an understanding of the changes in bioactivity. Recently, biophysical investigations with the S protein have been performed [63,79]. Where a dynamic light scattering (DLS) assay showed that an incubation of SARS-CoV-2 S protein with either 100, 250, or 500 μg/mL of LPS yielded a significant reduction of the hydrodynamic radii of the LPS particles in solution, transmission electron microscopy (TEM) showed larger aggregates in the samples with 250 or 500 μg/mL of LPS. This was further confirmed by incubating a fixed concentration of LPS with either 5 nM of SARS-CoV-2 S protein that caused the disaggregation of LPS, or higher levels that induced its aggregation. These findings indicate that the interaction of S protein with LPS complexes is concentration-dependent, leading first to disaggregation and then again to an increase with corresponding differences in biological activity. For a biophysical understanding of these processes, analyses based on the methodology of the publications quoted in the legends of Figure 2 (e.g., small-angle X-ray scattering) would be necessary.

According to the various papers cited above, it seems that LPS has a fundamental role in the expression of infectivity. In each case an enhancing action of LPS can be found. Interestingly, higher amounts of LPS and soluble CD14, a transport protein of LPS, was found in COVID-19 patients. Therefore, the question arises whether the infection caused by the SARS-Cov2 virus influences the metabolism of LPS in a way that leads to the observed detrimental effects of the infection.

The authors of [43,68,80] studied the coinfection of SARS-Cov2 with viruses, bacteria, and fungi, and discussed the reasons of the co-infection, their diagnosis, and their medical importance.

4. Influence of SARS-CoV-2 on the Coagulation System

Coagulopathy, with an incidence as high as 50% in patients with severe COVID-19, is frequent during both conventional sepsis and COVID-19. Coagulopathy in COVID-19 can be triggered by an increase in the vasoconstrictor angiotensin II, a decrease in the vasodilator angiotensin, and the sepsis-induced release of cytokines [81]. However, the effects of COVID-19 on the coagulation system are far from the typical disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC) seen during bacterial sepsis [82]. While bacterial coagulopathy is associated with coagulation factor X, COVID-19-associated coagulopathy is characterized by elevated circulating fibrinogen, high levels of D-dimer, thrombocytopenia, and mildly affected clotting times [83]. In addition, pulmonary microvascular thrombosis has been reported and may play a role in progressive lung failure [84].

Unlike during conventional sepsis, anticoagulation seems to play a key role in the treatment of COVID-19. However, there is a lack of practice guidelines tailored to these patients. A scoring system for COVID-19-coagulopathy and stratification of patients for the purpose of anticoagulation therapy based on risk categories has been proposed [33]. In patients with shock, it was observed that antithrombin (AT) alone, but not the combined action of heparin and AT showed therapeutically favorable effects. Their proposed scoring system and therapeutic guidelines are likely to undergo revisions in the future as new data become available in this evolving field.

5. Long COVID-19 Syndrome

A notable similarity exists between bacterial sepsis and COVID-19 phenotypes: they both can cause long-term sequelae. In both patient groups, being discharged from the hospital does not equal a complete recovery, and it is instead often followed by prolonged, and debilitating consequences. While in bacterial sepsis, the post-discharge complications are referred to as post-sepsis syndrome or persistent inflammation, immunosuppression, and catabolism syndrome (PICS), in SARS-CoV-2 infected patients, these manifestations are known as “long COVID” [85,86]. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), “Long COVID” is defined as the continuation or development of new symptoms 3 months after the initial SARS-CoV-2 infection, with these symptoms lasting for at least 2 months with no other explanation. Although risk factors for long COVID include old age, female sex, and moderate or severe COVID-19, long COVID can develop regardless of disease severity [87].

The most common persistent symptoms for both long COVID and post-sepsis syndrome, include fatigue, muscle pain, poor sleep, and cardiac or cognitive disturbances (e.g., arrhythmias, short-term memory loss). Remarkably, a troubling difference exists between the two conditions. Unlike in post-sepsis syndrome, long-COVID is frequently diagnosed in mildly SARS-CoV-2-infected patients (i.e., those with no hospital stay). The presence of the “long-phenotype” in both illnesses strongly indicates a severe and prolonged deregulation of organ homeostasis and the immune–inflammatory system (with clear immunosuppression features). In the context of the slowly subsiding severe COVID-19 manifestations, one should re-focus on the long-term sequalae to evaluate a potential risk of increase in chronic debilitation.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, K.B., G.M.-d.-T., G.W., P.G., R.F.-E. and C.N.; methodology, S.F., K.M. and R.F.-E.; software, K.B., G.W. and C.N.; validation, C.N., S.F. and K.M.; formal analysis, S.F., C.N. and G.W.; data curation, K.B., G.M.-d.-T. and P.G.; writing—original draft preparation, K.B., G.M.-d.-T., G.W. and P.G.; writing—review and editing, P.G., S.F., K.M. and R.F.-E.; visualization, K.B.; supervision, P.G.; project administration, P.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

C.N. Phospholipid Research Center, grant number CNE-2022-104/1-1.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data on X-ray scattering of bacterial toxins and on the biological activities of the antimicrobial peptide Aspidasept (Pep19-2.5) can be obtained from “Brandenburg Antiinfectiva GmbH” (K.B. and K.M.).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

| ACE2 | Angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 |

| ARDS | Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome |

| AT | Antithrombin |

| C-C Chemokine Receptor 2 | CCR2 |

| C-C Chemokine Receptor 5 | CCR5 |

| C-C Chemokine Receptor 7 | CCR7 |

| C-C Chemokine Ligand 2 | CCL2/MCP-1 |

| C-C Chemokine Ligand 4 | CCL4/MIP-1β |

| C-C Chemokine Ligand 5 | CCL5/RANTES |

| CD69 | Cluster of Differentiation 69 |

| COVID-19 | Coronavirus Disease of 2019 |

| DIC | Disseminated Intravascular Coagulation |

| E | Envelope protein |

| EMA | European Medicines Agency |

| FDA | Food and Drug Administration |

| FDA EUA | FDA Emergency Use Authorization |

| FITC | Fluorescein Isothiocyanate |

| HE | Hemagglutinin-esterase protein |

| IL-1 | Interleukin-1 |

| IL-10 | Interleukin-10 |

| IL-6 | Interleukin-6 |

| IRF | Interferon Regulatory Factor |

| KD | Dissociation constant |

| LBP | LPS-binding protein |

| LPS | Lipopolysaccharide |

| M | Membrane protein |

| MD-2 | Myeloid differentiation factor 2 |

| MODS | Multiple Organ Dysfunction Syndrome |

| N | Nucleocapsid protein |

| NIH | US National Institutes of Health |

| NF-κB | Nuclear Factor Kappa-B |

| PD-1 | Programmed Death-1 |

| S | Spike protein |

| SARS | Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome |

| SARS-CoV-2 | Coronavirus 2 cause of SARS |

| TGF-β1 | Transforming Growth Factor Beta 1 |

| TLR4 | Toll-like receptor 4 |

| TNF-α | Tumor Necrosis Factor Alpha |

References

- Hu, B.; Guo, H.; Zhou, P.; Shi, Z.-L. Characteristics of SARS-CoV-2 and COVID-19. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2021, 19, 141–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ochani, R.K.; Asad, A.; Yasmin, F.; Shaikh, S.; Khalid, H.; Batra, S.; Sohail, M.R.; Mahmood, S.F.; Ochani, R.; Arshad, M.H.; et al. COVID-19 Pandemic: From Origins to Outcomes. A Comprehensive Review of Viral Pathogenesis, Clinical Manifestations, Diagnostic Evaluation, and Management. Infez. Med. 2021, 29, 20–36. [Google Scholar]

- Gallo, C.G.; Fiorino, S.; Posabella, G.; Antonacci, D.; Tropeano, A.; Pausini, E.; Pausini, C.; Guarniero, T.; Hong, W.; Giampieri, E.; et al. COVID-19, What Could Sepsis, Severe Acute Pancreatitis, Gender Differences, and Aging Teach Us? Cytokine 2021, 148, 155628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torge, D.; Bernardi, S.; Arcangeli, M.; Bianchi, S. Histopathological Features of SARS-CoV-2 in Extrapulmonary Organ Infection: A Systematic Review of Literature. Pathogens 2022, 11, 867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Z.; Peng, Y.; Wu, X.; Pang, B.; Yang, F.; Zheng, W.; Liu, C.; Zhang, J. Comorbidities and Complications of COVID-19 Associated with Disease Severity, Progression, and Mortality in China with Centralized Isolation and Hospitalization: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Front. Public Health 2022, 10, 923485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, R.; Rai, A.K.; Phukan, M.M.; Hussain, A.; Borah, D.; Gogoi, B.; Chakraborty, P.; Buragohain, A.K. Accumulating Impact of Smoking and Co-Morbidities on Severity and Mortality of COVID-19 Infection: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Curr. Genom. 2021, 22, 339–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Honardoost, M.; Janani, L.; Aghili, R.; Emami, Z.; Khamseh, M.E. The Association between Presence of Comorbidities and COVID-19 Severity: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Cerebrovasc. Dis. 2021, 50, 132–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahlström, B.; Frithiof, R.; Larsson, I.-M.; Strandberg, G.; Lipcsey, M.; Hultström, M. A Comparison of Impact of Comorbidities and Demographics on 60-Day Mortality in ICU Patients with COVID-19, Sepsis and Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 15703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, S.; Zhao, Y.; Wang, F.; Chen, Y.; Kaminga, A.C.; Xu, H. Comorbidities’ Potential Impacts on Severe and Non-Severe Patients with COVID-19. Medicine 2021, 100, e24971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drake, T.M.; Riad, A.M.; Fairfield, C.J.; Egan, C.; Knight, S.R.; Pius, R.; Hardwick, H.E.; Norman, L.; Shaw, C.A.; McLean, K.A.; et al. Characterisation of In-Hospital Complications Associated with COVID-19 Using the ISARIC WHO Clinical Characterisation Protocol UK: A Prospective, Multicentre Cohort Study. Lancet 2021, 398, 223–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nalbandian, A.; Sehgal, K.; Gupta, A.; Madhavan, M.V.; McGroder, C.; Stevens, J.S.; Cook, J.R.; Nordvig, A.S.; Shalev, D.; Sehrawat, T.S.; et al. Post-Acute COVID-19 Syndrome. Nat. Med. 2021, 27, 601–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Terpos, E.; Ntanasis-Stathopoulos, I.; Elalamy, I.; Kastritis, E.; Sergentanis, T.N.; Politou, M.; Psaltopoulou, T.; Gerotziafas, G.; Dimopoulos, M.A. Hematological Findings and Complications of COVID-19. Am. J. Hematol. 2020, 95, 834–847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kostakis, I.; Smith, G.B.; Prytherch, D.; Meredith, P.; Price, C.; Chauhan, A. The Performance of the National Early Warning Score and National Early Warning Score 2 in Hospitalised Patients Infected by the Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2). Resuscitation 2021, 159, 150–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lalueza, A.; Lora-Tamayo, J.; Maestro-de la Calle, G.; Folgueira, D.; Arrieta, E.; de Miguel-Campo, B.; Díaz-Simón, R.; Lora, D.; de la Calle, C.; Mancheño-Losa, M.; et al. A Predictive Score at Admission for Respiratory Failure among Hospitalized Patients with Confirmed 2019 Coronavirus Disease: A Simple Tool for a Complex Problem. Intern. Emerg. Med. 2022, 17, 515–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herminghaus, A.; Osuchowski, M.F. How Sepsis Parallels and Differs from COVID-19. eBioMedicine 2022, 86, 104355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stasi, A.; Franzin, R.; Fiorentino, M.; Squiccimarro, E.; Castellano, G.; Gesualdo, L. Multifaced Roles of HDL in Sepsis and SARS-CoV-2 Infection: Renal Implications. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 5980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coudereau, R.; Waeckel, L.; Cour, M.; Rimmele, T.; Pescarmona, R.; Fabri, A.; Jallades, L.; Yonis, H.; Gossez, M.; Lukaszewicz, A.; et al. Emergence of Immunosuppressive LOX-1+ PMN-MDSC in Septic Shock and Severe COVID-19 Patients with Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome. J. Leukoc. Biol. 2022, 111, 489–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stasi, A.; Castellano, G.; Ranieri, E.; Infante, B.; Stallone, G.; Gesualdo, L.; Netti, G.S. SARS-CoV-2 and Viral Sepsis: Immune Dysfunction and Implications in Kidney Failure. J. Clin. Med. 2020, 9, 4057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, X.; Wang, C.; Liu, X.; Gao, W.; Bai, X.; Li, Z. Lessons Learned Comparing Immune System Alterations of Bacterial Sepsis and SARS-CoV-2 Sepsis. Front. Immunol. 2020, 11, 598404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Górski, A.; Borysowski, J.; Międzybrodzki, R. Sepsis, Phages, and COVID-19. Pathogens 2020, 9, 844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Limmer, A.; Engler, A.; Kattner, S.; Gregorius, J.; Pattberg, K.T.; Schulz, R.; Schwab, J.; Roth, J.; Vogl, T.; Krawczyk, A.; et al. Patients with SARS-CoV-2-Induced Viral Sepsis Simultaneously Show Immune Activation, Impaired Immune Function and a Procoagulatory Disease State. Vaccines 2023, 11, 435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Remy, K.E.; Mazer, M.; Striker, D.A.; Ellebedy, A.H.; Walton, A.H.; Unsinger, J.; Blood, T.M.; Mudd, P.A.; Yi, D.J.; Mannion, D.A.; et al. Severe Immunosuppression and Not a Cytokine Storm Characterizes COVID-19 Infections. JCI Insight 2020, 5, e140329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Plocque, A.; Mitri, C.; Lefèvre, C.; Tabary, O.; Touqui, L.; Philippart, F. Should We Interfere with the Interleukin-6 Receptor During COVID-19: What Do We Know So Far? Drugs 2023, 83, 1–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chousterman, B.G.; Swirski, F.K.; Weber, G.F. Cytokine Storm and Sepsis Disease Pathogenesis. In Seminars in Immunopathology; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Tang, H.; Qin, S.; Li, Z.; Gao, W.; Tang, M.; Dong, X. Early Immune System Alterations in Patients with Septic Shock. Front. Immunol. 2023, 14, 1126874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giamarellos-Bourboulis, E.J. Failure of Treatments Based on the Cytokine Storm Theory of Sepsis: Time for a Novel Approach. Immunotherapy 2013, 5, 207–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fortier, M.-E.; Kent, S.; Ashdown, H.; Poole, S.; Boksa, P.; Luheshi, G.N. The Viral Mimic, Polyinosinic:Polycytidylic Acid, Induces Fever in Rats via an Interleukin-1-Dependent Mechanism. Am. J. Physiol. Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 2004, 287, R759–R766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gu, T.; Zhao, S.; Jin, G.; Song, M.; Zhi, Y.; Zhao, R.; Ma, F.; Zheng, Y.; Wang, K.; Liu, H.; et al. Cytokine Signature Induced by SARS-CoV-2 Spike Protein in a Mouse Model. Front. Immunol. 2021, 11, 621441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allaouchiche, B. Immunotherapies for COVID-19: Restoring the Immunity Could Be the Priority. Anaesth. Crit. Care Pain. Med. 2020, 39, 385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perlin, D.S.; Neil, G.A.; Anderson, C.; Zafir-Lavie, I.; Raines, S.; Ware, C.F.; Wilkins, H.J. Randomized, Double-Blind, Controlled Trial of Human Anti-LIGHT Monoclonal Antibody in COVID-19 Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome. J. Clin. Investig. 2022, 132, e153173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Hu, K.; Li, Y.; Lu, C.; Ling, K.; Cai, C.; Wang, W.; Ye, D. Targeting TNF-α for COVID-19: Recent Advanced and Controversies. Front. Public. Health 2022, 10, 833967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Institutes of Health COVID-19 Treatment Guidelines Panel. In Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) Treatment Guidelines; National Institutes of Health: Stapleton, NY, USA, 2019.

- Remy, K.E.; Brakenridge, S.C.; Francois, B.; Daix, T.; Deutschman, C.S.; Monneret, G.; Jeannet, R.; Laterre, P.-F.; Hotchkiss, R.S.; Moldawer, L.L. Immunotherapies for COVID-19: Lessons Learned from Sepsis. Lancet Respir. Med. 2020, 8, 946–949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Islam, H.; Chamberlain, T.C.; Mui, A.L.; Little, J.P. Elevated Interleukin-10 Levels in COVID-19: Potentiation of Pro-Inflammatory Responses or Impaired Anti-Inflammatory Action? Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 677008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dalinghaus, M.; Gratama, J.W.C.; Koers, J.H.; Gerding, A.M.; Zijlstra, W.G.; Kuipers, J.R.G. Left Ventricular Oxygen and Substrate Uptake in Chronically Hypoxemic Lambs. Pediatr. Res. 1993, 34, 471–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Davitt, E.; Davitt, C.; Mazer, M.B.; Areti, S.S.; Hotchkiss, R.S.; Remy, K.E. COVID-19 Disease and Immune Dysregulation. Best. Pract. Res. Clin. Haematol. 2022, 35, 101401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Riva, G.; Nasillo, V.; Tagliafico, E.; Trenti, T.; Comoli, P.; Luppi, M. COVID-19: More than a Cytokine Storm. Crit. Care 2020, 24, 549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayor, S. Intensive Immunosuppression Reduces Deaths in Covid-19-Associated Cytokine Storm Syndrome, Study Finds. BMJ 2020, 370, m2935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, H.-Y.; Zhang, M.; Yang, C.-X.; Zhang, N.; Wang, X.-C.; Yang, X.-P.; Dong, X.-Q.; Zheng, Y.-T. Elevated Exhaustion Levels and Reduced Functional Diversity of T Cells in Peripheral Blood May Predict Severe Progression in COVID-19 Patients. Cell Mol. Immunol. 2020, 17, 541–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daix, T.; Mathonnet, A.; Brakenridge, S.; Dequin, P.-F.; Mira, J.-P.; Berbille, F.; Morre, M.; Jeannet, R.; Blood, T.; Unsinger, J.; et al. Intravenously Administered Interleukin-7 to Reverse Lymphopenia in Patients with Septic Shock: A Double-Blind, Randomized, Placebo-Controlled Trial. Ann. Intensive Care 2023, 13, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Francois, B.; Jeannet, R.; Daix, T.; Walton, A.H.; Shotwell, M.S.; Unsinger, J.; Monneret, G.; Rimmelé, T.; Blood, T.; Morre, M.; et al. Interleukin-7 Restores Lymphocytes in Septic Shock: The IRIS-7 Randomized Clinical Trial. JCI Insight 2018, 3, e98960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cucinotta, D.; Vanelli, M. WHO Declares COVID-19 a Pandemic. Acta Biomed. 2020, 91, 157–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, C.-C.; Wang, C.-Y.; Hsueh, P.-R. Co-Infections among Patients with COVID-19: The Need for Combination Therapy with Non-Anti-SARS-CoV-2 Agents? J. Microbiol. Immunol. Infect. 2020, 53, 505–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elnagdy, S.; AlKhazindar, M. The Potential of Antimicrobial Peptides as an Antiviral Therapy against COVID-19. ACS Pharmacol. Transl. Sci. 2020, 3, 780–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Meng, X.; Zhang, F.; Xiang, Y.; Wang, J. The in Vitro Antiviral Activity of Lactoferrin against Common Human Coronaviruses and SARS-CoV-2 Is Mediated by Targeting the Heparan Sulfate Co-Receptor. Emerg. Microbes Infect. 2021, 10, 317–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brandenburg, K.; Jürgens, G.; Müller, M.; Fukuoka, S.; Koch, M.H.J. Biophysical Characterization of Lipopolysaccharide and Lipid A Inactivation by Lactoferrin. Biol. Chem. 2001, 382, 1215–1225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sohn, K.M.; Lee, S.-G.; Kim, H.J.; Cheon, S.; Jeong, H.; Lee, J.; Kim, I.S.; Silwal, P.; Kim, Y.J.; Paik, S.; et al. COVID-19 Patients Upregulate Toll-like Receptor 4-Mediated Inflammatory Signaling That Mimics Bacterial Sepsis. J. Korean Med. Sci. 2020, 35, e343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bárcena-Varela, S.; Martínez-de-Tejada, G.; Martin, L.; Schuerholz, T.; Gil-Royo, A.G.; Fukuoka, S.; Goldmann, T.; Droemann, D.; Correa, W.; Gutsmann, T.; et al. Coupling Killing to Neutralization: Combined Therapy with Ceftriaxone/Pep19-2.5 Counteracts Sepsis in Rabbits. Exp. Mol. Med. 2017, 49, e345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brandenburg, K.; Andrä, J.; Garidel, P.; Gutsmann, T. Peptide-Based Treatment of Sepsis. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2011, 90, 799–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brandenburg, K.; Schromm, A.B.; Weindl, G.; Heinbockel, L.; Correa, W.; Mauss, K.; Martinez De Tejada, G.; Garidel, P. An Update on Endotoxin Neutralization Strategies in Gram-Negative Bacterial Infections. Expert. Rev. Anti-Infect. Ther. 2021, 19, 495–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gutsmann, T.; Razquin-Olazarán, I.; Kowalski, I.; Kaconis, Y.; Howe, J.; Bartels, R.; Hornef, M.; Schürholz, T.; Rössle, M.; Sanchez-Gómez, S.; et al. New Antiseptic Peptides to Protect against Endotoxin-Mediated Shock. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2010, 54, 3817–3824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaconis, Y.; Kowalski, I.; Howe, J.; Brauser, A.; Richter, W.; Razquin-Olazarán, I.; Iñigo-Pestaña, M.; Garidel, P.; Rössle, M.; Martinez de Tejada, G.; et al. Biophysical Mechanisms of Endotoxin Neutralization by Cationic Amphiphilic Peptides. Biophys. J. 2011, 100, 2652–2661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westblade, L.F.; Simon, M.S.; Satlin, M.J. Bacterial Coinfections in Coronavirus Disease 2019. Trends Microbiol. 2021, 29, 930–941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirzaei, R.; Goodarzi, P.; Asadi, M.; Soltani, A.; Aljanabi, H.; Abraham, A.; Jeda, A.S.; Dashtbin, S.; Jalalifar, S.; Mohammadzadeh, R.; et al. Bacterial Co-infections with SARS-CoV-2. IUBMB Life 2020, 72, 2097–2111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Conti, G.; Amadori, F.; Bordanzi, A.; Majorana, A.; Bardellini, E. The Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Pediatric Dentistry: Insights from an Italian Cross-Sectional Survey. Dent. J. 2023, 11, 154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, C.; Wang, Y.; Li, X.; Ren, L.; Zhao, J.; Hu, Y.; Zhang, L.; Fan, G.; Xu, J.; Gu, X.; et al. Clinical Features of Patients Infected with 2019 Novel Coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet 2020, 395, 497–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rietschel, E.T.; Brade, H.; Holst, O.; Brade, L.; Müller-Loennies, S.; Mamat, U.; Zähringer, U.; Beckmann, F.; Seydel, U.; Brandenburg, K.; et al. Bacterial Endotoxin: Chemical Constitution, Biological Recognition, Host Response, and Immunological Detoxification. Pathol. Septic Shock. 1996, 216, 39–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Tejada, G.M.; Heinbockel, L.; Ferrer-Espada, R.; Heine, H.; Alexander, C.; Bárcena-Varela, S.; Goldmann, T.; Correa, W.; Wiesmüller, K.H.; Gisch, N.; et al. Lipoproteins/Peptides Are Sepsis-Inducing Toxins from Bacteria That Can Be Neutralized by Synthetic Anti-Endotoxin Peptides. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 14292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, J.G.; Simpson, L.J.; Ferreira, A.-M.; Rustagi, A.; Roque, J.; Asuni, A.; Ranganath, T.; Grant, P.M.; Subramanian, A.; Rosenberg-Hasson, Y.; et al. Cytokine Profile in Plasma of Severe COVID-19 Does Not Differ from ARDS and Sepsis. JCI Insight 2020, 5, e140289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lüderitz, O.; Galanos, C.; Rietschel, E.T. Endotoxins of Gram-Negative Bacteria. Pharmacol. Ther. 1981, 15, 383–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammad, S.; Al Zoubi, S.; Collotta, D.; Krieg, N.; Wissuwa, B.; Ferreira Alves, G.; Purvis, G.S.D.; Norata, G.D.; Baragetti, A.; Catapano, A.L.; et al. A Synthetic Peptide Designed to Neutralize Lipopolysaccharides Attenuates Metaflammation and Diet-Induced Metabolic Derangements in Mice. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 701275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munford, R.S. Endotoxin(s) and the Liver. Gastroenterology 1978, 75, 532–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petruk, G.; Puthia, M.; Petrlova, J.; Samsudin, F.; Strömdahl, A.-C.; Cerps, S.; Uller, L.; Kjellström, S.; Bond, P.J.; Schmidtchen, A. SARS-CoV-2 Spike Protein Binds to Bacterial Lipopolysaccharide and Boosts Proinflammatory Activity. J. Mol. Cell Biol. 2020, 12, 916–932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrä, J.; Gutsmann, T.; Garidel, P.; Brandenburg, K. Mechanisms of Endotoxin Neutralization by Synthetic Cationic Compounds. J. Endotoxin Res. 2006, 12, 261–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teixeira, P.C.; Dorneles, G.P.; Santana Filho, P.C.; da Silva, I.M.; Schipper, L.L.; Postiga, I.A.L.; Neves, C.A.M.; Rodrigues Junior, L.C.; Peres, A.; de Souto, J.T.; et al. Increased LPS Levels Coexist with Systemic Inflammation and Result in Monocyte Activation in Severe COVID-19 Patients. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2021, 100, 108125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fan, C.; Wu, Y.; Rui, X.; Yang, Y.; Ling, C.; Liu, S.; Liu, S.; Wang, Y. Animal Models for COVID-19: Advances, Gaps and Perspectives. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2022, 7, 220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hong, W.; Yang, J.; Bi, Z.; He, C.; Lei, H.; Yu, W.; Yang, Y.; Fan, C.; Lu, S.; Peng, X.; et al. A Mouse Model for SARS-CoV-2-Induced Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2021, 6, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Puthia, M.; Tanner, L.; Petruk, G.; Schmidtchen, A. Experimental Model of Pulmonary Inflammation Induced by SARS-CoV-2 Spike Protein and Endotoxin. ACS Pharmacol. Transl. Sci. 2022, 5, 141–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tobias, P.S.; Soldau, K.; Gegner, J.A.; Mintz, D.; Ulevitch, R.J. Lipopolysaccharide Binding Protein-Mediated Complexation of Lipopolysaccharide with Soluble CD14. J. Biol. Chem. 1995, 270, 10482–10488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schumann, R.R.; Latz, E. Lipopolysaccharide-Binding Protein. Chem. Immunol. 2000, 74, 42–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richter, W.; Vogel, V.; Howe, J.; Steiniger, F.; Brauser, A.; Koch, M.H.; Roessle, M.; Gutsmann, T.; Garidel, P.; Mäntele, W.; et al. Morphology, Size Distribution, and Aggregate Structure of Lipopolysaccharide and Lipid A Dispersions from Enterobacterial Origin. Innate Immun. 2011, 17, 427–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mueller, M.; Lindner, B.; Kusumoto, S.; Fukase, K.; Schromm, A.B.; Seydel, U. Aggregates Are the Biologically Active Units of Endotoxin. J. Biol. Chem. 2004, 279, 26307–26313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schromm, A.B.; Brandenburg, K.; Loppnow, H.; Moran, A.P.; Koch, M.H.J.; Rietschel, E.T.; Seydel, U. Biological Activities of Lipopolysaccharides Are Determined by the Shape of Their Lipid A Portion. Eur. J. Biochem. 2000, 267, 2008–2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Israelachvili, J.N. Chapter 19: Thermodynamic Principles of Self-Assembly. In Intermolecular & Surface Forces; Academic Press Ltd.: London, UK, 1991; Volume 2, pp. 341–365. ISBN 978-0-12-375182-9. [Google Scholar]

- Andra, J.; Garidel, P.; Majerle, A.; Jerala, R.; Ridge, R.; Paus, E.; Novitsky, T.; Koch, M.H.J.; Brandenburg, K. Biophysical Characterization of the Interaction of Limulus Polyphemus Endotoxin Neutralizing Protein with Lipopolysaccharide. Eur. J. Biochem. 2004, 271, 2037–2046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brandenburg, K. Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy Characterization of the Lamellar and Nonlamellar Structures of Free Lipid A and Re Lipopolysaccharides from Salmonella Minnesota and Escherichia Coli. Biophys. J. 1993, 64, 1215–1231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howe, J.; Andrä, J.; Conde, R.; Iriarte, M.; Garidel, P.; Koch, M.H.J.; Gutsmann, T.; Moriyón, I.; Brandenburg, K. Thermodynamic Analysis of the Lipopolysaccharide-Dependent Resistance of Gram-Negative Bacteria against Polymyxin B. Biophys. J. 2007, 92, 2796–2805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garidel, P.; Brandenburg, K. Current Understanding of Polymyxin B Applications in Bacteraemia/ Sepsis Therapy Prevention: Clinical, Pharmaceutical, Structural and Mechanistic Aspects. Anti-Infect. Agents Med. Chem. 2009, 8, 367–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Petrlova, J.; Samsudin, F.; Bond, P.J.; Schmidtchen, A. SARS-CoV-2 Spike Protein Aggregation Is Triggered by Bacterial Lipopolysaccharide. FEBS Lett. 2022, 596, 2566–2575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, X.; Liao, B.; Cheng, L.; Peng, X.; Xu, X.; Li, Y.; Hu, T.; Li, J.; Zhou, X.; Ren, B. The Microbial Coinfection in COVID-19. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2020, 104, 7777–7785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miesbach, W.; Makris, M. COVID-19: Coagulopathy, Risk of Thrombosis, and the Rationale for Anticoagulation. Clin. Appl. Thromb. Hemost. 2020, 26, 1076029620938149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadid, T.; Kafri, Z.; Al-Katib, A. Coagulation and Anticoagulation in COVID-19. Blood Rev. 2021, 47, 100761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- José, R.J.; Williams, A.; Manuel, A.; Brown, J.S.; Chambers, R.C. Targeting Coagulation Activation in Severe COVID-19 Pneumonia: Lessons from Bacterial Pneumonia and Sepsis. Eur. Respir. Rev. 2020, 29, 200240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ackermann, M.; Verleden, S.E.; Kuehnel, M.; Haverich, A.; Welte, T.; Laenger, F.; Vanstapel, A.; Werlein, C.; Stark, H.; Tzankov, A.; et al. Pulmonary Vascular Endothelialitis, Thrombosis, and Angiogenesis in Covid-19. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 383, 120–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Natarajan, A.; Shetty, A.; Delanerolle, G.; Zeng, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Raymont, V.; Rathod, S.; Halabi, S.; Elliot, K.; Shi, J.Q.; et al. A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Long COVID Symptoms. Syst. Rev. 2023, 12, 88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Szabo, S.; Zayachkivska, O.; Hussain, A.; Muller, V. What Is Really ‘Long COVID’? Inflammopharmacology 2023, 31, 551–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.; Bae, S.; Chang, H.-H.; Kim, S.-W. Long COVID Prevalence and Impact on Quality of Life 2 Years after Acute COVID-19. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 11207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).