Cellular Senescence, Inflammation, and Cancer in the Gastrointestinal Tract

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Cellular Senescence

3. Senescence in GI Mucosa and Muscle

4. Immunosenescence

5. Inflammatory Bowel Disease

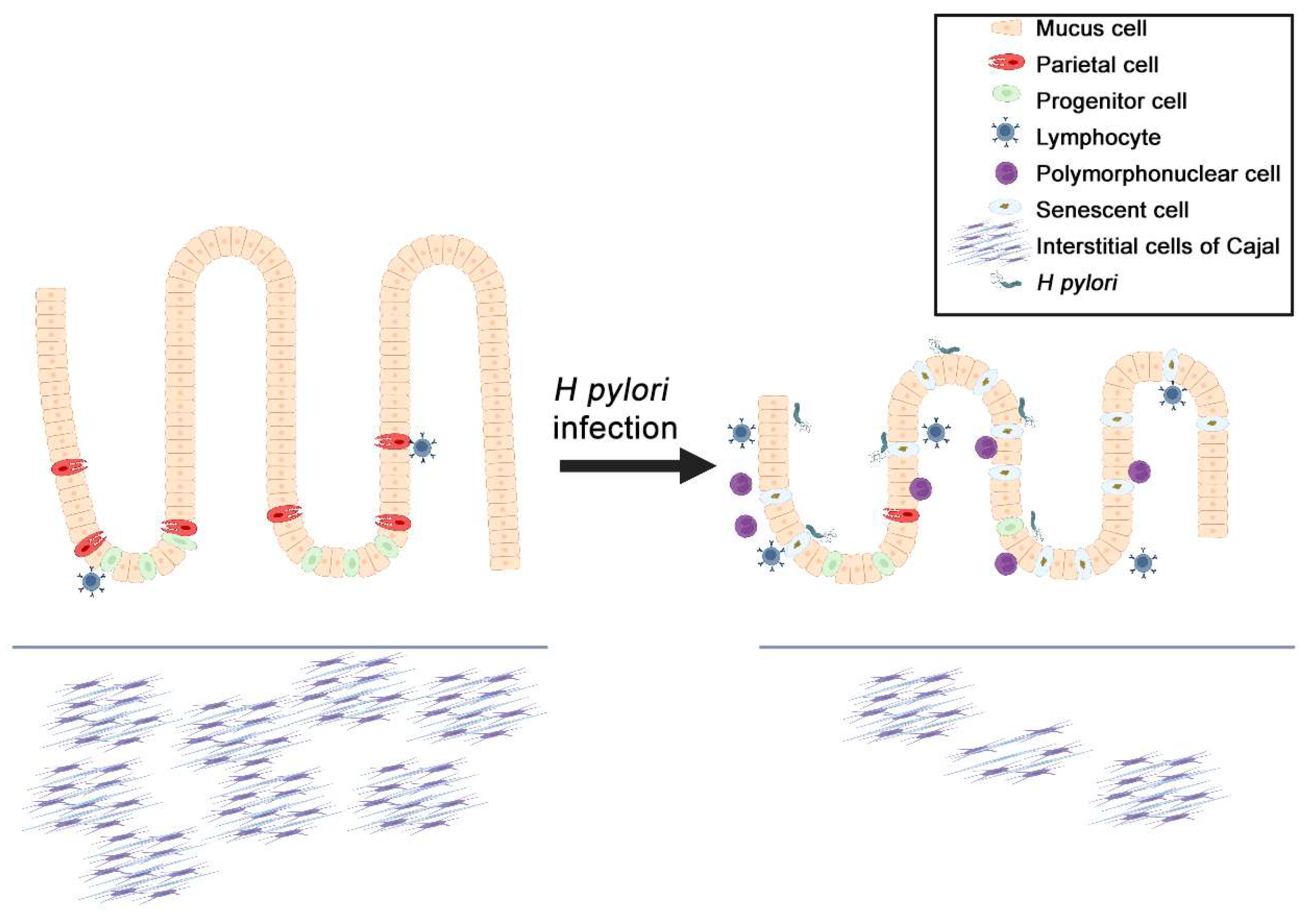

6. Esophagitis

7. Helicobacter pylori, Senescence, and Gastric Cancer

8. Cellular Senescence in GI Cancers and GIST

9. Senotherapeutics and Clinical Trials

10. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ABCs | Age-associated B cells |

| CRC | Colorectal cancer |

| GALT | Gut-associated lymphoid tissue |

| GI | Gastrointestinal tract |

| GIST | Gastrointestinal stromal tumor |

| H2S | Hydrogen sulfide |

| IBD | Inflammatory bowel disease |

| ICCs | Interstitial cells of Cajal |

| IL | Interleukin |

| SASP | Senescence-associated secretory phenotype |

| UC | Ulcerative colitis |

| Gene/Protein Expansions | |

| CXCR | C-X-C motif chemokine receptor |

| DREAM | Dimerization partner, RB-like, E2F and multi-vulval class B |

| DYRK1A | Dual specificity tyrosine-phosphorylation-regulated kinase 1A |

| ERK | Extracellular signal-regulated kinase |

| GDF15 | Growth differentiation factor 15 |

| KIT | KIT proto-oncogene, receptor tyrosine kinase |

| miR-20a-5p | MicroRNA-20a-5p |

| MYC | MYC proto-oncogene, bHLH transcription factor |

| PTEN | Phosphatase and tension homolog |

| PUMA | p53 upregulated modulator of apoptosis |

| SENP1 | SUMO specific peptidase 1 |

| TGFβ | Transforming growth factor β |

| TLR | Toll-like receptor |

| Wnt | Wingless/integrated |

References

- World Health Organization. Ageing and Health. 2022. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/ageing-and-health (accessed on 12 April 2023).

- Enzinger, P.C.; Mayer, R.J. Gastrointestinal cancer in older patients. Semin. Oncol. 2004, 31, 206–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, L.; Lankhorst, L.; Bernards, R. Exploiting senescence for the treatment of cancer. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2022, 22, 340–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, Y.; Ayers, J.L.; Carter, K.T.; Wang, T.; Maden, S.K.; Edmond, D.; Newcomb, P.P.; Li, C.; Ulrich, C.; Yu, M.; et al. Senescence-associated tissue microenvironment promotes colon cancer formation through the secretory factor GDF15. Aging Cell 2019, 18, e13013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pilott, A.; Fabrello, R.; Franceschi, M.; Scagnelli, M.; Soffiati, F.; Di Mario, F.; Fortunato, A.; Valerio, G. Helicobacter pylori infection in asymptomatic elderly subjects living at home or in a nursing home: Effects on gastric function and nutritional status. Age Ageing 1996, 25, 245–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scapa, E.; Horowitz, M.; Waron, M.; Eshchar, J. Duodenal ulcer in the elderly. J. Clin. Gastroenterol. 1989, 11, 502–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmitt, C.A.; Tchkonia, T.; Niedernhofer, L.J.; Robbins, P.D.; Kirkland, J.L.; Lee, S. COVID-19 and cellular senescence. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2023, 23, 251–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Yu, Y.; Trimpert, J.; Benthani, F.; Mairhofer, M.; Richter-Pechanska, P.; Wyler, E.; Belenki, D.; Kaltenbrunner, S.; Pammer, M.; et al. Virus-induced senescence is a driver and therapeutic target in COVID-19. Nature 2021, 599, 283–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camilleri, M.; Chedid, V.; Ford, A.C.; Haruma, K.; Horowitz, M.; Jones, K.L.; Low, P.A.; Park, S.Y.; Parkman, H.P.; Stanghellini, V. Gastroparesis. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers 2018, 4, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, V.T.T.; Taheri, N.; Chandra, A.; Hayashi, Y. Aging of enteric neuromuscular systems in gastrointestinal tract. Neurogastroenterol. Motil. 2022, 34, e14352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dodig, S.; Cepelak, I.; Pavic, I. Hallmarks of senescence and aging. Biochem. Med. 2019, 29, 030501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herranz, N.; Gil, J. Mechanisms and functions of cellular senescence. J. Clin. Investig. 2018, 128, 1238–1246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basu, A.K. DNA Damage, Mutagenesis and Cancer. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossiello, F.; Jurk, D.; Passos, J.F.; d’Adda di Fagagna, F. Telomere dysfunction in ageing and age-related diseases. Nat. Cell Biol. 2022, 24, 135–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roger, L.; Tomas, F.; Gire, V. Mechanisms and Regulation of Cellular Senescence. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 13173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kowalska, M.; Piekut, T.; Prendecki, M.; Sodel, A.; Kozubski, W.; Dorszewska, J. Mitochondrial and Nuclear DNA Oxidative Damage in Physiological and Pathological Aging. DNA Cell Biol. 2020, 39, 1410–1420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlsson, M.J.; Vollmer, A.S.; Demuth, P.; Heylmann, D.; Reich, D.; Quarz, C.; Rasenberger, B.; Nikolova, T.; Hofmann, T.G.; Christmann, M.; et al. p53 triggers mitochondrial apoptosis following DNA damage-dependent replication stress by the hepatotoxin methyleugenol. Cell Death Dis. 2022, 13, 1009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiley, C.D.; Velarde, M.C.; Lecot, P.; Liu, S.; Sarnoski, E.A.; Freund, A.; Shirakawa, K.; Lim, H.W.; Davis, S.S.; Ramanathan, A.; et al. Mitochondrial Dysfunction Induces Senescence with a Distinct Secretory Phenotype. Cell Metab. 2016, 23, 303–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, Y.Y.; Um, J.H.; Yoon, J.H.; Lee, D.Y.; Lee, Y.J.; Kim, D.H.; Park, J.I.; Yun, J. p53 regulates mitochondrial dynamics by inhibiting Drp1 translocation into mitochondria during cellular senescence. FASEB J. 2020, 34, 2451–2464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, C.Y.; Vo, M.T.; Nicholas, J.; Choi, Y.B. Autophagy-competent mitochondrial translation elongation factor TUFM inhibits caspase-8-mediated apoptosis. Cell Death Differ. 2022, 29, 451–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Janic, A.; Valente, L.J.; Wakefield, M.J.; Di Stefano, L.; Milla, L.; Wilcox, S.; Yang, H.; Tai, L.; Vandenberg, C.J.; Kueh, A.J.; et al. DNA repair processes are critical mediators of p53-dependent tumor suppression. Nat. Med. 2018, 24, 947–953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vougioukalaki, M.; Demmers, J.; Vermeij, W.P.; Baar, M.; Bruens, S.; Magaraki, A.; Kuijk, E.; Jager, M.; Merzouk, S.; Brandt, R.M.C.; et al. Different responses to DNA damage determine ageing differences between organs. Aging Cell 2022, 21, e13562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, J.P., IV; Yashinskie, J.J.; Koche, R.; Chandwani, R.; Tian, S.; Chen, C.C.; Baslan, T.; Marinkovic, Z.S.; Sanchez-Rivera, F.J.; Leach, S.D.; et al. α-Ketoglutarate links p53 to cell fate during tumour suppression. Nature 2019, 573, 595–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asadi Shahmirzadi, A.; Edgar, D.; Liao, C.Y.; Hsu, Y.M.; Lucanic, M.; Asadi Shahmirzadi, A.; Wiley, C.D.; Gan, G.; Kim, D.E.; Kasler, H.G.; et al. Alpha-Ketoglutarate, an Endogenous Metabolite, Extends Lifespan and Compresses Morbidity in Aging Mice. Cell Metab. 2020, 32, 447–456.e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez, F.O.; Sironi, M.; Vecchi, A.; Colotta, F.; Mantovani, A.; Locati, M. IL-8 induces a specific transcriptional profile in human neutrophils: Synergism with LPS for IL-1 production. Eur. J. Immunol. 2004, 34, 2286–2292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ponzetta, A.; Carriero, R.; Carnevale, S.; Barbagallo, M.; Molgora, M.; Perucchini, C.; Magrini, E.; Gianni, F.; Kunderfranco, P.; Polentarutti, N.; et al. Neutrophils Driving Unconventional T Cells Mediate Resistance against Murine Sarcomas and Selected Human Tumors. Cell 2019, 178, 346–360.e24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campisi, J. Aging, cellular senescence, and cancer. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 2013, 75, 685–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munoz-Espin, D.; Canamero, M.; Maraver, A.; Gomez-Lopez, G.; Contreras, J.; Murillo-Cuesta, S.; Rodriguez-Baeza, A.; Varela-Nieto, I.; Ruberte, J.; Collado, M.; et al. Programmed cell senescence during mammalian embryonic development. Cell 2013, 155, 1104–1118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laberge, R.M.; Awad, P.; Campisi, J.; Desprez, P.Y. Epithelial-mesenchymal transition induced by senescent fibroblasts. Cancer Microenviron. 2012, 5, 39–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhai, J.; Shen, J.; Xie, G.; Wu, J.; He, M.; Gao, L.; Zhang, Y.; Yao, X.; Shen, L. Cancer-associated fibroblasts-derived IL-8 mediates resistance to cisplatin in human gastric cancer. Cancer Lett. 2019, 454, 37–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, X.; Yan, M.; Wang, X.; Xu, Q.; Wang, X.; Zhu, X.; Shi, J.; Li, Z.; Zhang, J.; Chen, W. Cancer-associated Fibroblast-derived IL-6 Promotes Head and Neck Cancer Progression via the Osteopontin-NF-kappa B Signaling Pathway. Theranostics 2018, 8, 921–940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barajas-Gomez, B.A.; Rosas-Carrasco, O.; Morales-Rosales, S.L.; Pedraza Vazquez, G.; Gonzalez-Puertos, V.Y.; Juarez-Cedillo, T.; Garcia-Alvarez, J.A.; Lopez-Diazguerrero, N.E.; Damian-Matsumura, P.; Konigsberg, M.; et al. Relationship of inflammatory profile of elderly patients serum and senescence-associated secretory phenotype with human breast cancer cells proliferation: Role of IL6/IL8 ratio. Cytokine 2017, 91, 13–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haraoka, Y.; Akieda, Y.; Nagai, Y.; Mogi, C.; Ishitani, T. Zebrafish imaging reveals TP53 mutation switching oncogene-induced senescence from suppressor to driver in primary tumorigenesis. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 1417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hayashi, Y.; Asuzu, D.T.; Bardsley, M.R.; Gajdos, G.B.; Kvasha, S.M.; Linden, D.R.; Nagy, R.A.; Saravanaperumal, S.A.; Syed, S.A.; Toyomasu, Y.; et al. Wnt-induced, TRP53-mediated Cell Cycle Arrest of Precursors Underlies Interstitial Cell of Cajal Depletion During Aging. Cell. Mol. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2021, 11, 117–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, H.; Fergusson, M.M.; Castilho, R.M.; Liu, J.; Cao, L.; Chen, J.; Malide, D.; Rovira, I.I.; Schimel, D.; Kuo, C.J.; et al. Augmented Wnt signaling in a mammalian model of accelerated aging. Science 2007, 317, 803–806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palmer, A.; Epton, S.; Crawley, E.; Straface, M.; Gammon, L.; Edgar, M.M.; Xu, Y.; Elahi, S.; Chin-Aleong, J.; Martin, J.E.; et al. Expression of p16 Within Myenteric Neurons of the Aged Colon: A Potential Marker of Declining Function. Front. Neurosci. 2021, 15, 747067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Deursen, J.M. The role of senescent cells in ageing. Nature 2014, 509, 439–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SenNet Consortium. NIH SenNet Consortium to map senescent cells throughout the human lifespan to understand physiological health. Nat. Aging 2022, 2, 1090–1100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yousefzadeh, M.J.; Flores, R.R.; Zhu, Y.; Schmiechen, Z.C.; Brooks, R.W.; Trussoni, C.E.; Cui, Y.; Angelini, L.; Lee, K.A.; McGowan, S.J.; et al. An aged immune system drives senescence and ageing of solid organs. Nature 2021, 594, 100–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morbe, U.M.; Jorgensen, P.B.; Fenton, T.M.; von Burg, N.; Riis, L.B.; Spencer, J.; Agace, W.W. Human gut-associated lymphoid tissues (GALT); diversity, structure, and function. Mucosal Immunol. 2021, 14, 793–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koboziev, I.; Karlsson, F.; Grisham, M.B. Gut-associated lymphoid tissue, T cell trafficking, and chronic intestinal inflammation. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2010, 1207 (Suppl. 1), E86–E93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinet, K.Z.; Bloquet, S.; Bourgeois, C. Ageing combines CD4 T cell lymphopenia in secondary lymphoid organs and T cell accumulation in gut associated lymphoid tissue. Immun. Ageing 2014, 11, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senda, T.; Dogra, P.; Granot, T.; Furuhashi, K.; Snyder, M.E.; Carpenter, D.J.; Szabo, P.A.; Thapa, P.; Miron, M.; Farber, D.L. Microanatomical dissection of human intestinal T-cell immunity reveals site-specific changes in gut-associated lymphoid tissues over life. Mucosal Immunol. 2019, 12, 378–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenstein, M. Biology: A slow-motion epidemic. Nature 2016, 540, S98–S99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, Y.; Manne, S.; Treem, W.R.; Bennett, D. Prevalence of Inflammatory Bowel Disease in Pediatric and Adult Populations: Recent Estimates From Large National Databases in the United States, 2007–2016. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2020, 26, 619–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitsialis, V.; Wall, S.; Liu, P.; Ordovas-Montanes, J.; Parmet, T.; Vukovic, M.; Spencer, D.; Field, M.; McCourt, C.; Toothaker, J.; et al. Single-Cell Analyses of Colon and Blood Reveal Distinct Immune Cell Signatures of Ulcerative Colitis and Crohn’s Disease. Gastroenterology 2020, 159, 591–608.e10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uzzan, M.; Martin, J.C.; Mesin, L.; Livanos, A.E.; Castro-Dopico, T.; Huang, R.; Petralia, F.; Magri, G.; Kumar, S.; Zhao, Q.; et al. Ulcerative colitis is characterized by a plasmablast-skewed humoral response associated with disease activity. Nat. Med. 2022, 28, 766–779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cancro, M.P. Age-Associated B Cells. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 2020, 38, 315–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.W.; Zhan, X.; McAlpine, W.; Zhang, Z.; Choi, J.H.; Shi, H.; Misawa, T.; Yue, T.; Zhang, D.; Wang, Y.; et al. Enhanced susceptibility to chemically induced colitis caused by excessive endosomal TLR signaling in LRBA-deficient mice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2019, 116, 11380–11389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McAlpine, W.; Sun, L.; Wang, K.W.; Liu, A.; Jain, R.; San Miguel, M.; Wang, J.; Zhang, Z.; Hayse, B.; McAlpine, S.G.; et al. Excessive endosomal TLR signaling causes inflammatory disease in mice with defective SMCR8-WDR41-C9ORF72 complex function. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2018, 115, E11523–E11531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naradikian, M.S.; Myles, A.; Beiting, D.P.; Roberts, K.J.; Dawson, L.; Herati, R.S.; Bengsch, B.; Linderman, S.L.; Stelekati, E.; Spolski, R.; et al. Cutting Edge: IL-4, IL-21, and IFN-gamma Interact To Govern T-bet and CD11c Expression in TLR-Activated B Cells. J. Immunol. 2016, 197, 1023–1028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eiro, N.; Gonzalez, L.; Gonzalez, L.O.; Andicoechea, A.; Fernandez-Diaz, M.; Altadill, A.; Vizoso, F.J. Study of the expression of toll-like receptors in different histological types of colorectal polyps and their relationship with colorectal cancer. J. Clin. Immunol. 2012, 32, 848–854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yashiro, M. Ulcerative colitis-associated colorectal cancer. World J. Gastroenterol. 2014, 20, 16389–16397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, S.C.; Itzkowitz, S.H. Colorectal Cancer in Inflammatory Bowel Disease: Mechanisms and Management. Gastroenterology 2022, 162, 715–730.e3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giunco, S.; Petrara, M.R.; Bergamo, F.; Del Bianco, P.; Zanchetta, M.; Carmona, F.; Zagonel, V.; De Rossi, A.; Lonardi, S. Immune senescence and immune activation in elderly colorectal cancer patients. Aging 2019, 11, 3864–3875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matsumoto, M.; Kurihara, S.; Kibe, R.; Ashida, H.; Benno, Y. Longevity in mice is promoted by probiotic-induced suppression of colonic senescence dependent on upregulation of gut bacterial polyamine production. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e23652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Risques, R.A.; Lai, L.A.; Himmetoglu, C.; Ebaee, A.; Li, L.; Feng, Z.; Bronner, M.P.; Al-Lahham, B.; Kowdley, K.V.; Lindor, K.D.; et al. Ulcerative colitis-associated colorectal cancer arises in a field of short telomeres, senescence, and inflammation. Cancer Res. 2011, 71, 1669–1679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sohn, J.J.; Schetter, A.J.; Yfantis, H.G.; Ridnour, L.A.; Horikawa, I.; Khan, M.A.; Robles, A.I.; Hussain, S.P.; Goto, A.; Bowman, E.D.; et al. Macrophages, nitric oxide and microRNAs are associated with DNA damage response pathway and senescence in inflammatory bowel disease. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e44156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, K.J.; Lassmann, H. The role of nitric oxide in multiple sclerosis. Lancet Neurol. 2002, 1, 232–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watanabe, S.; Hibiya, S.; Katsukura, N.; Kitagawa, S.; Sato, A.; Okamoto, R.; Watanabe, M.; Tsuchiya, K. Importance of Telomere Shortening in the Pathogenesis of Ulcerative Colitis: A New Treatment From the Aspect of Telomeres in Intestinal Epithelial Cells. J. Crohn’s Colitis 2022, 16, 109–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubio, C.A.; Petris, G.D.E.; Puppa, G. Gut-associated Lymphoid Tissue (GALT) Carcinoma in Ulcerative Colitis. Anticancer Res. 2018, 38, 919–921. [Google Scholar]

- Martincorena, I.; Fowler, J.C.; Wabik, A.; Lawson, A.R.J.; Abascal, F.; Hall, M.W.J.; Cagan, A.; Murai, K.; Mahbubani, K.; Stratton, M.R.; et al. Somatic mutant clones colonize the human esophagus with age. Science 2018, 362, 911–917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabir, M.F.; Karami, A.L.; Cruz-Acuna, R.; Klochkova, A.; Saxena, R.; Mu, A.; Murray, M.G.; Cruz, J.; Fuller, A.D.; Clevenger, M.H.; et al. Single cell transcriptomic analysis reveals cellular diversity of murine esophageal epithelium. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 2167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souza, R.F. Reflux esophagitis and its role in the pathogenesis of Barrett’s metaplasia. J. Gastroenterol. 2017, 52, 767–776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pilotto, A.; Salles, N. Helicobacter pylori infection in geriatrics. Helicobacter 2002, 7, 56–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uemura, N.; Okamoto, S.; Yamamoto, S.; Matsumura, N.; Yamaguchi, S.; Yamakido, M.; Taniyama, K.; Sasaki, N.; Schlemper, R.J. Helicobacter pylori infection and the development of gastric cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2001, 345, 784–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walecka-Kapica, E.; Knopik-Dabrowicz, A.; Klupinska, G.; Chojnacki, J. The assessment of nitric oxide metabolites in gastric juice in Helicobacter pylori infected subjects in compliance with grade of inflammatory lesions in gastric mucosa. Pol. Merkur. Lekarski 2008, 24, 95–100. [Google Scholar]

- Neal, J.T.; Peterson, T.S.; Kent, M.L.; Guillemin, K. H. pylori virulence factor CagA increases intestinal cell proliferation by Wnt pathway activation in a transgenic zebrafish model. Dis. Model. Mech. 2013, 6, 802–810. [Google Scholar]

- Song, X.; Xin, N.; Wang, W.; Zhao, C. Wnt/beta-catenin, an oncogenic pathway targeted by H. pylori in gastric carcinogenesis. Oncotarget 2015, 6, 35579–35588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuo, W.; Yang, H.; Li, N.; Ouyang, Y.; Xu, X.; Hong, J. Helicobacter pylori infection activates Wnt/beta-catenin pathway to promote the occurrence of gastritis by upregulating ASCL1 and AQP5. Cell Death Discov. 2022, 8, 257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.; Dong, J.; Wang, S.; Yu, H.; Li, Z.; Sun, P.; Zhao, L. Helicobacter pylori causes delayed gastric emptying by decreasing interstitial cells of Cajal. Exp. Ther. Med. 2021, 22, 663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, S.; Seifert, A.M.; Zhang, J.Q.; Cavnar, M.J.; Kim, T.S.; Balachandran, V.P.; Santamaria-Barria, J.A.; Cohen, N.A.; Beckman, M.J.; Medina, B.D.; et al. Wnt/beta-catenin Signaling Contributes to Tumor Malignancy and Is Targetable in Gastrointestinal Stromal Tumor. Mol. Cancer Ther. 2017, 16, 1954–1966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kagihara, J.; Matsuda, B.; Young, K.L.; Li, X.; Lao, X.; Deshpande, G.A.; Omata, F.; Burnett, T.; Lynch, C.F.; Hernandez, B.Y.; et al. Novel association between Helicobacter pylori infection and gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GIST) in a multi-ethnic population. Gastrointest. Stromal Tumor 2020, 3, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldenring, J.R.; Mills, J.C. Cellular Plasticity, Reprogramming, and Regeneration: Metaplasia in the Stomach and Beyond. Gastroenterology 2022, 162, 415–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Cabalag, C.S.; Clemons, N.J.; DuBois, R.N. Cyclooxygenases and Prostaglandins in Tumor Immunology and Microenvironment of Gastrointestinal Cancer. Gastroenterology 2021, 161, 1813–1829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guzik, T.J.; Korbut, R.; Adamek-Guzik, T. Nitric oxide and superoxide in inflammation and immune regulation. J. Physiol. Pharmacol. 2003, 54, 469–487. [Google Scholar]

- De Salvo, C.; Pastorelli, L.; Petersen, C.P.; Butto, L.F.; Buela, K.A.; Omenetti, S.; Locovei, S.A.; Ray, S.; Friedman, H.R.; Duijser, J.; et al. Interleukin 33 Triggers Early Eosinophil-Dependent Events Leading to Metaplasia in a Chronic Model of Gastritis-Prone Mice. Gastroenterology 2021, 160, 302–316.e7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, A.R.; Goldenring, J.R. Injury, repair, inflammation and metaplasia in the stomach. J. Physiol. 2018, 596, 3861–3867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eggert, T.; Wolter, K.; Ji, J.; Ma, C.; Yevsa, T.; Klotz, S.; Medina-Echeverz, J.; Longerich, T.; Forgues, M.; Reisinger, F.; et al. Distinct Functions of Senescence-Associated Immune Responses in Liver Tumor Surveillance and Tumor Progression. Cancer Cell 2016, 30, 533–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garbers, C.; Kuck, F.; Aparicio-Siegmund, S.; Konzak, K.; Kessenbrock, M.; Sommerfeld, A.; Haussinger, D.; Lang, P.A.; Brenner, D.; Mak, T.W.; et al. Cellular senescence or EGFR signaling induces Interleukin 6 (IL-6) receptor expression controlled by mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR). Cell Cycle 2013, 12, 3421–3432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Trotman, L.C.; Shaffer, D.; Lin, H.K.; Dotan, Z.A.; Niki, M.; Koutcher, J.A.; Scher, H.I.; Ludwig, T.; Gerald, W.; et al. Crucial role of p53-dependent cellular senescence in suppression of Pten-deficient tumorigenesis. Nature 2005, 436, 725–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akahoshi, K.; Oya, M.; Koga, T.; Shiratsuchi, Y. Current clinical management of gastrointestinal stromal tumor. World J. Gastroenterol. 2018, 24, 2806–2817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujimaki, K.; Yao, G. Cell dormancy plasticity: Quiescence deepens into senescence through a dimmer switch. Physiol. Genom. 2020, 52, 558–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeCaprio, J.A.; Duensing, A. The DREAM complex in antitumor activity of imatinib mesylate in gastrointestinal stromal tumors. Curr. Opin. Oncol. 2014, 26, 415–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boichuk, S.; Parry, J.A.; Makielski, K.R.; Litovchick, L.; Baron, J.L.; Zewe, J.P.; Wozniak, A.; Mehalek, K.R.; Korzeniewski, N.; Seneviratne, D.S.; et al. The DREAM complex mediates GIST cell quiescence and is a novel therapeutic target to enhance imatinib-induced apoptosis. Cancer Res. 2013, 73, 5120–5129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.Y.; Lin, J.R.; Tsai, F.C.; Meyer, T. Dosage of Dyrk1a shifts cells within a p21-cyclin D1 signaling map to control the decision to enter the cell cycle. Mol. Cell 2013, 52, 87–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayashi, Y.; Nguyen, V.T.T. A narrative review of imatinib-resistant gastrointestinal stromal tumors. Gastrointest. Stromal Tumor 2021, 4, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.; Ni, N.; Yuan, L.; Xu, L.; Bahri, N.; Sun, B.; Wu, Y.; Ou, W.B. Proteasome Inhibition Suppresses KIT-Independent Gastrointestinal Stromal Tumors Via Targeting Hippo/YAP/Cyclin D1 Signaling. Front. Pharmacol. 2021, 12, 686874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, T.H.; Tai, M.H.; Chuah, S.K.; Chen, H.H.; Lin, J.W.; Huang, H.Y.; Chou, Y.P.; Yi, L.N.; Kuo, C.M.; Changchien, C.S. Elevated p21 expression is associated with poor prognosis of rectal stromal tumors after resection. J. Surg. Oncol. 2008, 98, 117–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, M.C.; Lin, J.W.; Lin, S.E.; Chen, H.H.; Lee, C.M.; Hu, T.H. Prognostic analysis of rectal stromal tumors by reference of National Institutes of Health risk categories and immunohistochemical studies. Dis. Colon Rectum 2008, 51, 1535–1543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chou, Y.P.; Lin, J.W.; Wang, C.C.; Chiu, Y.C.; Huang, C.C.; Chuah, S.K.; Tai, M.H.; Yi, L.N.; Lee, C.M.; Changchien, C.S.; et al. The abnormalities in the p53/p21WAF1 pathway have a significant role in the pathogenesis and progression of gastrointestinal stromal tumors. Oncol. Rep. 2008, 19, 49–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, Q.; Shi, P.; Yuan, Y.; Peng, J.; Ou, X.; Zhou, W.; Li, J.; Su, T.; Lin, L.; Cai, S.; et al. Inflammation-Associated Senescence Promotes Helicobacter pylori-Induced Atrophic Gastritis. Cell. Mol. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2021, 11, 857–880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deguchi, R.; Takagi, A.; Kawata, H.; Inoko, H.; Miwa, T. Association between CagA+ Helicobacter pylori infection and p53, bax and transforming growth factor-beta-RII gene mutations in gastric cancer patients. Int. J. Cancer 2001, 91, 481–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khare, T.; Bissonnette, M.; Khare, S. CXCL12-CXCR4/CXCR7 Axis in Colorectal Cancer: Therapeutic Target in Preclinical and Clinical Studies. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 7371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siegel, R.L.; Miller, K.D.; Fuchs, H.E.; Jemal, A. Cancer Statistics, 2021. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2021, 71, 7–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, Y.W.; Kim, Y.H.; Oh, S.Y.; Suh, K.W.; Kim, Y.S.; Lee, G.Y.; Yoon, J.E.; Park, S.S.; Lee, Y.K.; Park, Y.J.; et al. Senescent Tumor Cells Build a Cytokine Shield in Colorectal Cancer. Adv. Sci. 2021, 8, 2002497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cougnoux, A.; Dalmasso, G.; Martinez, R.; Buc, E.; Delmas, J.; Gibold, L.; Sauvanet, P.; Darcha, C.; Dechelotte, P.; Bonnet, M.; et al. Bacterial genotoxin colibactin promotes colon tumour growth by inducing a senescence-associated secretory phenotype. Gut 2014, 63, 1932–1942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Short, S.; Fielder, E.; Miwa, S.; von Zglinicki, T. Senolytics and senostatics as adjuvant tumour therapy. EBioMedicine 2019, 41, 683–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hickson, L.J.; Langhi Prata, L.G.P.; Bobart, S.A.; Evans, T.K.; Giorgadze, N.; Hashmi, S.K.; Herrmann, S.M.; Jensen, M.D.; Jia, Q.; Jordan, K.L.; et al. Senolytics decrease senescent cells in humans: Preliminary report from a clinical trial of Dasatinib plus Quercetin in individuals with diabetic kidney disease. EBioMedicine 2019, 47, 446–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Prata, L.; Gerdes, E.O.W.; Netto, J.M.E.; Pirtskhalava, T.; Giorgadze, N.; Tripathi, U.; Inman, C.L.; Johnson, K.O.; Xue, A.; et al. Orally-active, clinically-translatable senolytics restore alpha-Klotho in mice and humans. EBioMedicine 2022, 77, 103912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rouault, C.; Marcelin, G.; Adriouch, S.; Rose, C.; Genser, L.; Ambrosini, M.; Bichet, J.C.; Zhang, Y.; Marquet, F.; Aron-Wisnewsky, J.; et al. Senescence-associated beta-galactosidase in subcutaneous adipose tissue associates with altered glycaemic status and truncal fat in severe obesity. Diabetologia 2021, 64, 240–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolodkin-Gal, D.; Roitman, L.; Ovadya, Y.; Azazmeh, N.; Assouline, B.; Schlesinger, Y.; Kalifa, R.; Horwitz, S.; Khalatnik, Y.; Hochner-Ger, A.; et al. Senolytic elimination of Cox2-expressing senescent cells inhibits the growth of premalignant pancreatic lesions. Gut 2022, 71, 345–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.W.; Johmura, Y.; Suzuki, N.; Omori, S.; Migita, T.; Yamaguchi, K.; Hatakeyama, S.; Yamazaki, S.; Shimizu, E.; Imoto, S.; et al. Blocking PD-L1-PD-1 improves senescence surveillance and ageing phenotypes. Nature 2022, 611, 358–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saccon, T.D.; Nagpal, R.; Yadav, H.; Cavalcante, M.B.; Nunes, A.D.C.; Schneider, A.; Gesing, A.; Hughes, B.; Yousefzadeh, M.; Tchkonia, T.; et al. Senolytic Combination of Dasatinib and Quercetin Alleviates Intestinal Senescence and Inflammation and Modulates the Gut Microbiome in Aged Mice. J. Gerontol. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 2021, 76, 1895–1905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hine, C.; Harputlugil, E.; Zhang, Y.; Ruckenstuhl, C.; Lee, B.C.; Brace, L.; Longchamp, A.; Trevino-Villarreal, J.H.; Mejia, P.; Ozaki, C.K.; et al. Endogenous hydrogen sulfide production is essential for dietary restriction benefits. Cell 2015, 160, 132–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latorre, E.; Torregrossa, R.; Wood, M.E.; Whiteman, M.; Harries, L.W. Mitochondria-targeted hydrogen sulfide attenuates endothelial senescence by selective induction of splicing factors HNRNPD and SRSF2. Aging 2018, 10, 1666–1681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, H.; Yu, Q.; Mi, Y.; Wang, P.; Jin, S.; Xiao, L.; Guo, Q.; Wu, Y. Hydrogen Sulfide Inhibited Sympathetic Activation in D-Galactose-Induced Aging Rats by Upregulating Klotho and Inhibiting Inflammation in the Paraventricular Nucleus. Biomedicines 2023, 11, 566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zivanovic, J.; Kouroussis, E.; Kohl, J.B.; Adhikari, B.; Bursac, B.; Schott-Roux, S.; Petrovic, D.; Miljkovic, J.L.; Thomas-Lopez, D.; Jung, Y.; et al. Selective Persulfide Detection Reveals Evolutionarily Conserved Antiaging Effects of S-Sulfhydration. Cell Metab. 2019, 30, 1152–1170.e13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilkie, S.E.; Borland, G.; Carter, R.N.; Morton, N.M.; Selman, C. Hydrogen sulfide in ageing, longevity and disease. Biochem. J. 2021, 478, 3485–3504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Choi, E.L.; Taheri, N.; Chandra, A.; Hayashi, Y. Cellular Senescence, Inflammation, and Cancer in the Gastrointestinal Tract. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 9810. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms24129810

Choi EL, Taheri N, Chandra A, Hayashi Y. Cellular Senescence, Inflammation, and Cancer in the Gastrointestinal Tract. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2023; 24(12):9810. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms24129810

Chicago/Turabian StyleChoi, Egan L., Negar Taheri, Abhishek Chandra, and Yujiro Hayashi. 2023. "Cellular Senescence, Inflammation, and Cancer in the Gastrointestinal Tract" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 24, no. 12: 9810. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms24129810

APA StyleChoi, E. L., Taheri, N., Chandra, A., & Hayashi, Y. (2023). Cellular Senescence, Inflammation, and Cancer in the Gastrointestinal Tract. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 24(12), 9810. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms24129810